Abstract

Protein kinases (PKs) are allosteric enzymes that play an essential role in signal transduction by regulating a variety of key cellular processes. Most PKs suffer conformational rearrangements upon phosphorylation that strongly enhance the catalytic activity. Generally, it involves the movement of the phosphorylated loop toward the active site and the rotation of the whole C-terminal lobe. However, not all kinases undergo such a large configurational change: The MAPK extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases ERK1 and ERK2 achieve a 50 000 fold increase in kinase activity with only a small motion of the C-terminal region. In the present work, we used a combination of molecular simulation tools to characterize the conformational landscape of ERK2 in the active (phosphorylated) and inactive (unphosphorylated) states in solution in agreement with NMR experiments. We show that the chemical reaction barrier is strongly dependent on ATP conformation and that the “active” low-barrier configuration is subtly regulated by phosphorylation, which stabilizes a key salt bridge between the conserved Lys52 and Glu69 belonging to helix-C and promotes binding of a second Mg ion. Our study highlights that the on−off switch embedded in the kinase fold can be regulated by small, medium, and large conformational changes.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Protein kinases (PKs) are allosteric enzymes that play an essential role in signal transduction, regulating many biological processes. PKs have evolved to be dynamic molecular switches that can be controlled by dimerization, membrane recruitment, and phosphorylation. A large set of serine/threonine and tyrosine PKs are phosphorylated in their activation segment-loop leading to a conformational change that strongly enhances their catalytic activity, and therefore research efforts have focused on understanding how kinase activity is dynamically regulated by this configurational transition. In many PKs, a large conformational change is observed upon activation, involving the opening of the A-loop, the relative alignment of N-lobe and C-lobe, and the rotation of the αC-helix. The “closure/rotation” allows important residues necessary for catalysis to accommodate in the active site.1

Extracellular activated protein kinases ERK/MAPKs (ERK1 and ERK2) are the most extensively studied members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) subfamily of PKs and aberrant activation of their signaling pathway is a frequent event in many human malignancies.2,3 Because the ERK signaling pathway is an attractive target for cancer chemotherapy, interest in its components has exploded in the past few years.4,5 MAPKs are characterized by their requirement of dual phosphorylation at conserved threonine (Thr) and tyrosine (Tyr) residues for activation6,7 and their specific activity toward Ser/Thr residues of the substrate proteins/peptides, which are always followed by a proline residue.8 Structural and biochemical studies have extensively characterized the activation process and the catalytic activity of MAPKs; and there is compelling evidence that MAPKs facilitate substrate recognition through docking interactions outside the active site, where ATP binding and phosphate transfer occur.9

Conformational changes accompanying the activation of ERK2, albeit small, have been documented by X-ray structures of the inactive, unphosphorylated (0P-ERK2)10 and active, dual-phosphorylated (2P-ERK2) forms.6 Phosphorylation rearranges the activation loop, leading to new ion-pair interactions between phospho-Thr and phospho-Tyr residues with the basic residues in the N- and C-terminal lobes of the kinase core structure. Other structural changes upon activation include the folding of a 310 helix at loop L16 which exposes a hydrophobic zipper that forms the domain interface in the dimer,11 and a small domain rotation (5° over the C-lobe)6 (Figure 1A,B) 1. Recent studies show the importance of the loop L16 for the stabilization of αC-helix and also provide a structural framework for allosteric coupling between peptide binding at the D-domain docking groove and catalytic control via αC-helix positioning and interlobe motion in ERK2.12,13 More recently, Carr−Purcell−Meiboom−Gill (CPMG) relaxation dispersion experiments, an NMR-based method to monitor protein dynamics on slow time scales (100−2000 s), suggested that ERK2 displays a dynamic equilibrium between two conformational states. 0P-ERK2 presents mainly an inactive conformation constrained from domain motions, and phosphorylation is proposed to shift the equilibrium to favor the active conformer.14 However, since 0P-ERK2 and 2P-ERK2 structures are very similar, the structural differences responsible for the increase in activity and CPMG reported conformational changes, are far from clear.

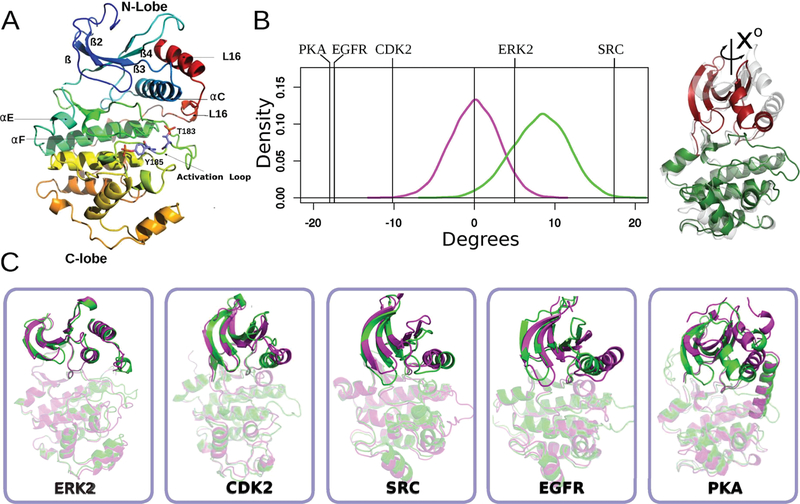

Figure 1.

Activation promotes conformational changes in helix-C and the N-terminal lobe. (A) Cartoon representation of the structure of active ERK2. Color changes from blue (N-terminal) to red (C-terminal). Secondary structures elements are labeled accordingly. (B) Kernel density estimation of the N-lobe to C-lobe rotational angle of the ERK2 taken from 1 μs long MD simulations (inactive shown in magenta, active in green). Vertical lines correspond to the change in the angle observed for the crystallographic structures of different kinases, the sign represents the direction of rotation of the active conformer respect to the inactive form. (C) Inactive (magenta) and active (green) conformations of five different kinases are shown (after C-lobe alignment) in order to illustrate the structural changes of the C-helix and N-terminal lobes.

The structural determinants that control ERK2 and the chemical step if other kinases are also still poorly understood. In most PKs in the active state, an invariant active site lysine (Lys52 in ERK2) residue plays a critical role in stabilizing the transition-state, by coordination to the α and β phosphoryl group oxygen atoms of ATP.15,16 Substitution of this residue to arginine or alanine in ERK2 results in a dramatic reduction in the turnover rate, with little effect on ground state ATP binding.7,17 Similarly, in inactive 0P-ERK2, Lys52 does not make contact with ATP (PDB ID 4GT3), explaining its reduced phosphotransfer kinetics, despite little difference in ATP affinity.18,19 Dual phosphorylation is presumed to optimize the alignment of Lys52, activating the protein, as supported by a set of inhibitors that despite allowing the DFG motif to adopt an active conformation disrupt the key salt bridge between the catalytic Lys52 and a conserved glutamic acid20 (Glu69 in ERK2).

Finally, from a chemical mechanism viewpoint, there are several recent theoretical studies on kinases mainly based on hybrid quantum-mechanics/molecular-mechanics (QM/MM) methods.21–24 Earlier studies of CDK2, for example, suggested that an Asp residue serves as the general base to activate the Ser nucleophile. The corresponding transition state features a dissociative metaphosphate-like structure, stabilized by the Mg ion and several hydrogen bonds.21 Specifically concerning MAPKs, previous studies from our group using an energy minimization scheme, showed for ERK2 a moderate barrier (17 kcal/mol) for the active state, and the key role played by Lys52 to strongly stabilize the transition state.17

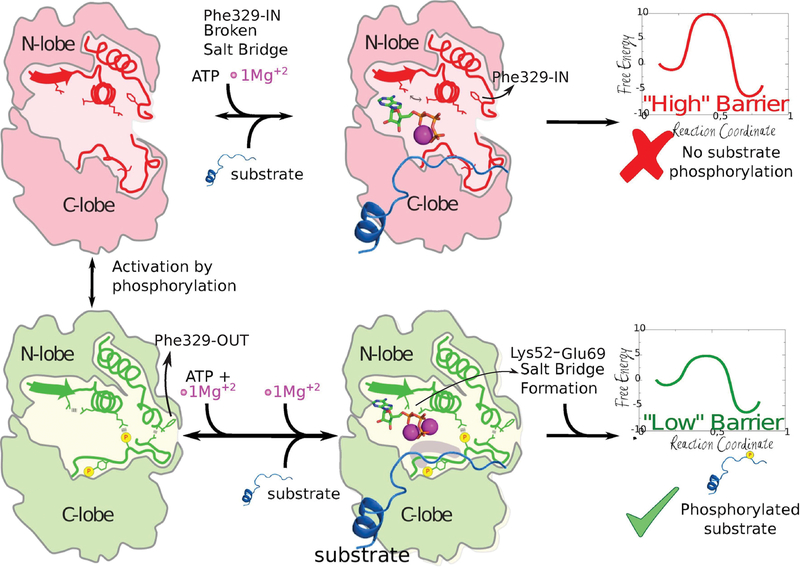

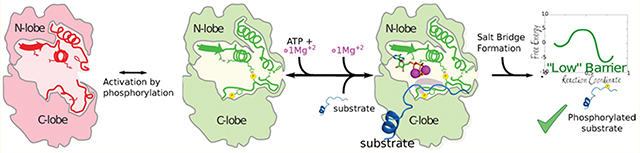

A summary of the previous studies on ERK2 leads to the following conclusions: (i) the structures of ERK2 in the crystal active and inactive states are very similar in terms of catalytic pocket, (ii) ATP binding affinity is not significantly affected, (iii) solution NMR and H/D experiments suggest the presence of two conformations in 0P-ERK2 that shift to one configuration upon phosphorylation. None of these provides a definite answer to how at the molecular level dual phosphorylation results in ERK2 activation, and the role played by protein conformational dynamics in catalysis. In the present work, we have used multiscale molecular simulation tools, such as quantum mechanics (QM) and molecular mechanics (MM) simulations, to unravel the coupling between conformational dynamics and catalysis in ERK2. Our results provide evidence that the chemical reaction barrier is strongly dependent on ATP conformation. In turn, the active low-barrier configuration is subtly regulated by phosphorylation which allows the activation loop to reorganize a key salt bridge between the conserved Lys52 and Glu69 in helix-C and promotes the proper binding of the second Mg ion, resulting in a suitable conformation for catalysis. This mechanism, which seems to be conserved in many Ser/Thr protein kinases, explains why despite a lack of significant overall differences between the active and inactive ERK2 structures there is a 50 000 fold increase in catalytic activity upon phosphorylation.

METHODS

ERK2 Starting Structures.

The starting structures of nonphosphorylated and dual-phosphorylated ERK2 were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (entries 1ERK,25 2ERK6 respectively). The catalytically competent complex was built as in our previous QM/MM study of ERK2 reaction mechanism.17 Briefly, we added to the dual-phosphorylated ERK2 structure the ATP and two Mg ions using as a template the structure of p38γ (PDB 1CM8).26 This structure corresponds to a highly similar MAPK which was crystallized phosphorylated, bound to ATP, and has two octahedrally coordinated Mg binding sites. In other words, we incorporated the ATP and two Mg ions to the 2P-ERK2 structure respecting the coordination found in the crystal structure of p38γ (1CM8). We analyzed the Mg ions coordination for other protein kinases but we did not find significant differences (Table S1). Subsequently, we added the phosphoacceptor substrate as described in our previous work, with the OH group of Thr pointing toward the γ-phosphate of ATP and the conserved proline in a pocket comprised by the phospho-Thr in the P+1 site.17 Last, the ATP-bound conformation for the unphosphorylated form of ERK2, was built taking into account the ATP and the Mg ion disposition from the inactive ERK2 structures 4S32 and 4GT3 (in addition to 1CM8).

A summary of the models used in this work is shown in Table 1. In all the ATP-bound structures the Mg binding Site I (MSI) is built by bidentate coordination to Asp165, ATP-Pβ, and two water molecules, the Mg binding site II (MSII) by Asn152, Asp165 ATP-Pα, and one water molecule (Figure S1). The modeled structures are provided as Supporting Information.

Table 1.

ERK2 Models

| name | ATP/2Mg | Phos-Tyr and Phos-Thr | substrate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0P-ERK2 | - | - | - |

| 0P-ERK2-ATP | √ | - | - |

| 2P-ERK2 | - | √ | - |

| 2P-ERK2-ATP | √ | √ | - |

| 2P-ERK2-ATP-substrate | √ | √ | √ |

Classical Simulation Parameters.

All classical simulations were performed with the AMBER16 package of programs.27 The starting structures were solvated with an isometric truncated octahedron of TIP3P28 water molecules extending a minimum of 12 Å beyond protein edge. Hydrogen atoms were added with the tleap module of the Amber Program package.27 Standard protonation states were assigned to titrable residues (D and E are negatively charged, K and R positively charged) for all protocols. Histidine protonation was assigned to favoring formation of hydrogen bonds in the crystal structure. All standard residues were represented using the AMBER14SB force field.29 Parameters for phospho-Tyr and phospho-Thr were taken from Craft et al.30 and the ATP parameters from Meagher et al.31 In all simulations the particle-mesh Ewald method32 was used with a nonbonded cutoff of 12 Å for computing electrostatic interactions, and the Langevin thermostat, Berendsen barostat to maintain the desired temperature and pressure, respectively.33,34 All hydrogen bonds were kept rigid by using the SHAKE algorithm, and the hydrogen mass repartitioning scheme was employed. The scheme scales all hydrogen masses by a factor of 3, allowing the use of a 4 fs time step for integrating Newton’s equations.35,36 Each system was first gently heated to 300 K for 200 ps at constant volume and using a soft harmonic restraint to all C-alpha carbons (1 kcal/mol Å2). Subsequently, 1 ns constant temperature and pressure MD simulations were performed to equilibrate the system density without any additional restraints. Production simulations consisted of 1 μs long molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for the apo (0P-ERK2 and 2P-ERK2) and holo (0P-ERK2-ATP and 2P-ERK2-ATP) states.

Domain Orientation.

Domain closure/rotation was calculated by aligning the C-terminal lobe and then computing the interlobe rotation (N- to C-lobe rotation). For this purpose, a homemade script using pymol was used (https://pymolwiki.org/index.php/Angle_between_domains). The PDB IDs used to calculate the interdomain rotation of Figure 1 were the following: PKA (4DFY,37 1J3H38), CDK2 (4KD1,39 3QHW40), EGFR (2GS6, 2GS741), Src (2SRC,42 3DQW43) and ERK2 (1ERK,25 2ERK6). The figures were generated using the PyMol molecular graphics software (v.1.7.2.1; Schrödinger LLC). The sign represents the direction of rotation. Negative numbers imply a clockwise rotation of the active form (into the direction of the ATP pocket, with the C-lobe below and the N-lobe above) while positive numbers imply a counterclockwise rotation.

Essential Mode (EM) Analysis.

To analyze the overlap between each protein state dynamics (0P-ERK2, 2P-ERK2, 0P-ERK2-ATP, and 2P-ERK2-ATP) the structural transition between them, we computed the “transition EM” corresponding to the first EM derived from the covariance matrix obtained from a combined trajectory, which is simply built by joining the two independent simulations. This “transition EM” represents a collective coordinate that describes the conformational transition and can be used to analyze the configurational space, along this coordinate, explored by any simulation by simply projecting the corresponding trajectory on the corresponding EM, according to eq 1

| (1) |

where V is the transition EM vector and r(t) is the protein conformation at time t. Projections are measured in angstroms, and the value corresponds to the overall deviation from the mean structure along the projected transition mode. After projecting the selected MD simulation along the selected mode, the normalized histograms were computed. For more details about EM analysis see the references.44

Umbrella Sampling (US).

US was used to determine the strength of the conserved salt bridge between Lys52 and Glu69, and to estimate the free energy change associated with Phe-IN and Phe-OUT states of the L16 loop, using as conformational coordinate the distances between and Glu69:Cδ and between the alpha carbons of the Ile72 and the Phe329, respectively. Windows were evenly spaced with a 0.5 Å separation distance and simulated for 2 ns each using a force constant of 30 kcal/mol/Å2. It should be noted that the initial conformations of the 0P-ERK2-ATP and 2P-ERK2-ATP for the umbrella sampling protocol, were built with a properly established salt bridge. The potential of mean force was calculated as implemented in WHAM.45 Histogram overlap and convergence of the US simulations are respectively shown in Figure S2 and Figure S3. Statistical uncertainty was determined using 50 bootstrap samples and was in all cases below 0.013 kcal/mol (Figure S4).

Thermodynamic Integration (TI).

To analyze the effect of dual-phosphorylation in the Mg ion affinity at the MSI site we computed the binding affinity in both the 0P-ERK2-ATP and 2P-ERK2-ATP states using the thermodynamic cycle depicted in Figure S5. The relative free energies were calculated using AMBER1627 with the AMBER 14SB force field29 using the TI implementation in pmemd.46 The starting structures for the TI calculation were taken from snapshots corresponding to an equilibrated MD trajectory, and the free energy perturbation calculations were performed by alchemically modifying the complex for the “disappearing” of the Mg ion at the MSI site (MgI ion). This was achieved by scaling the electrostatic interactions and van der Waals interactions simultaneously and using soft-core potentials.47 We varied the coupling parameter in 0.1 steps from 0 to 1 explicitly with a total simulation time per λ window of 1.5 ns. To get converged dv/dλ values, we kept the last nanosecond of the trajectory per window. ΔΔG of Mg binding was estimated as ΔG0P − ΔG2P (Table 2). Each ΔG value was estimated by averaging the binding energy of 3 replicates, reaching a total of 33 windows per state and a total simulation time of 50 ns. Statistical analysis and estimation of the binding free energy for each replica were made with the python script of MBAR.48 The performed TI calculations are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of TI Calculations

| name | initial structure (λ = 0) | final structure (λ = 1) |

|---|---|---|

| ΔG0P | 0P-ERK2-ATP with MgI ion and MgII ion | 0P-ERK2-ATP with MgII ion |

| ΔG2P | 2P-ERK2-ATP with MgI ion and MgII ion | 2P-ERK2-ATP with MgII ion |

Determination of the Reaction Free Energy Profile Using QM/MM and Multiple Steered Molecular Dynamics (MSMD) Strategy.

To determine the free energy profile (FEP) of the phospho-transfer reaction catalyzed by ERK2, we used MSMD combined with a QM/MM scheme. The FEP was calculated for the 2P-ERK2-ATP-substrate system described in the ERK2 Starting Structures subsection and two additional systems: 2P-ERK2 K52A-ATP-substrate and 0P-ERK2-ATP-(MSII)-substrate. The former was built by mutating the conserved Lys52 to alanine in the 2P-ERK2-ATP-substrate system and the latter by removing the Mg ion (MSI site) from a 0P-ERK2-ATP structure (derived from the MDs) and adding the tripeptide substrate as previously described.

QM/MM Methods.

The system was divided into a classical part (MM) and a small quantum part (QM). The QM subsystem consisted of the triphosphate part of ATP, the Mg cation(s), the closest water molecules completing the hydration shell of the ions, and the side chain of the catalytic pocket residues comprised by Asp147, Asn152, Asp165 with the standard protonation state. We also include the side chain of the Thr of the target peptide reaching a total of 34 atoms for the 2P-ERK2-ATP-substrate system (60 if all hydrogen atoms are included); the self-consistent charge density functional tight binding (SCC-DFTB)49 level of theory was used, offering a balanced trade-off between accuracy and computational cost (implemented in AMBER 16 package27). The rest of the ERK2 protein (classical subsystem), together with the surrounding water molecules, were treated classically with the AMBER14SB force field and the above-mentioned parameters for modified amino acids. All simulations were performed with periodic boundary conditions, a time step of 1 fs, an electrostatic cutoff of 15 Å, and a total production time length of 100 ps. The interface between the QM and MM portions was treated accordingly with the link atom method as implemented in the sander module.49

MSMD Strategy.

The MSMD method50–53 was successfully used previously by our group50–52,54 and comprises the use of a set of nonequilibrium pulling trajectories to obtain the associated free energy profile (ΔG). Briefly, in each trajectory, the system is conducted through a reaction coordinate (RC) by applying a time-dependent potential. H(r,λ) is the Hamiltonian of a system that is subject to an external time-dependent potential (λ = λ(t)). ΔG(λ) and W(λ) are the change in free energy and the external work performed on the system as it evolves from λ = λ0 to λt, respectively. The external work is performed by the guiding or steering force. Here r depicts a configuration of the whole system, while λ is the chosen reaction coordinate. Then, ΔG(λ) and W(λ) are related to each other by the following equation, known as Jarzynski’s relationship55 (eq 2).

| (2) |

The brackets in eq 2 represent an average taken over an ensemble of molecular dynamics trajectories provided the initial ensemble is equilibrated. Thus, in practice, in order to obtain ΔG(λ), multiple trajectories are performed in which the system is steered from reactants to products along λ, using an external force (which usually takes a harmonic potential form) and the work(λ) performed is measured along the trajectory. Once several trajectories and the corresponding work(λ) profiles have been determined, the free energy profile G(λ) is obtained using eq 2. To perform each trajectory, equilibrated snapshots were randomly taken from classical Molecular Dynamics simulations with a separation between frames of no less than 5 ns, beginning after the first 50 ns of the corresponding classical MD simulations. We use a Born−Oppenheimer molecular dynamics simulation to equilibrate the system for 25 ps. Then, we selected a combination of four distances as the reaction coordinate, as described in eq 3:

| (3) |

This reaction coordinate allows a joint description of the phosphate transfer, characterized by the breaking of the O3β−Pγ bond in the ATP, and formation of the Pγ−Oγ bond between the gamma phosphate and the OH of the substrate. As well as the proton transfer of the attacking nucleophile to the Asp 147 acid acting as the acceptor base, and characterized by the breaking of the Oγ−Hγ bond, and formation of the Asp147:O2δ−Hγ bond. In our particular system, the starting points of the RC were −4.0, −4.0, and −6.0 Å for the 2P-ERK2-ATP-substrate, 2P-ERK2 K52A-ATP-substrate, and 0P-ERK2-ATP-substrate, respectively.

For all MSMD simulations, a pulling speed of 0.07 Å/ps was used. Faster speeds were tested but resulted in too much variation in the W(λ) profiles, thus leading to convergence problems of the potential of mean force (PMF). The number of MSMD runs used to determine each PMF varied in the 10−30 range as described in the results section, showing a good convergence for a small number of curves (Figure S6). The convergence of PMF and the standard deviation of each point of the profile was determined with a leave-one-out cross-validation methodology.

RESULTS

ERK2 Undergoes a Small Conformational Rearrangement upon Phosphorylation.

We begin our analysis looking in detail at ERK2 structural changes upon phosphorylation (Figure1A) and its comparison with four well-studied protein kinases (CDK2, PKA, EGFR, and SRC) (Figure1B,C). Although in ERK2 the activation loop significantly rearranges when phosphorylated, there is not a significant reorientation of the N and C-terminal lobes, in contrast to what is observed for other PKs. Usually, in other kinases this change involves a rotation of the αC-helix, with the concomitant movement of the beta sheets and the glycine-rich loop of the N-terminal lobe, a movement that can be characterized by the angle between the αC-helix and αF-helix or the interlobe rotation (see Methods) (Figure 1A,B and Figure S7). PKA has the largest rotation angle, 18°, if the unphosphorylated enzyme (PDB ID 4DFY) is compared with the active apoenzyme (PDB ID 1J3H) or an even larger angle of 26° when compared with the active holoenzyme (PDB ID 1ATP).37 The rotation is similar in EGFR upon activation; SRC has a similar angle, but the rotation is in the opposite direction, while in CDK2 the angle is around 10°. However, surprisingly ERK2 crystallographic structures show a rotation of only 5° as described by Barr13 (Figure 1B,C). Consistently, the N-terminal lobe RMSD between active and inactive structures determined after fitting the C-terminal lobe is 2 Å in PKA but less than 0.7 Å in ERK2 (Figure 1C). Another characteristic that has been used to describe kinase activation is the configuration of the so-called R (regulatory) and C (catalytic) spine residue interactions (Figure S8)56–58 which are disrupted in the inactive state and formed in the active state. However, in ERK2 we observed no significant differences in the configuration between the inactive and phosphorylated protein for these residues. Thus the spine is formed in both states. These results are consistent with the fact that the structure-based classification of PKs in the active or inactive states has failed to correctly assign ERK2 structures59 and suggests these changes could be necessary but are not sufficient to control enzymatic activity.

Previous studies14 also proposed that ERK2 may undergo a conformational change in solution that is different from that observed in the crystal structures. Therefore, and to analyze the role of ERK2 conformational dynamics with the activation process, we performed long (1 μs per replica) classical MD simulations of both 0P-ERK2 and 2P-ERK2. Results show that both states oscillate around the observed crystal (initial) structure and no major changes are observed. Consistently, a significant overlap of the rotational angle histogram was observed between the active and inactive states either with or without ATP bound (0P-ERK, 2P-ERK, 0P-ERK-ATP, and 2P-ERK-ATP), indicating that the conformational change is subtle and that both states are mutually visited (Figure 1B and Figure S7). The small change observed for the conformational angle, (of ca. 5 degrees between 0P and 2P-ERK2 X-ray structures) is also in sharp contrast to what is observed in other PKs where the change is significantly larger (>10 degrees). Similar results are obtained when ERK2 dynamics are analyzed using Essential Modes (Figure S9), since the projection of both trajectories on the inactive-to-active transition mode (see Methods), shows significant overlap, underscoring the fact that both conformations of the kinase domain are mutually visited. These results together with the similarity in the X-ray structures,6,10 suggest that inactive and active ERK2 domain conformations are not only similar but are mutually visited during long protein dynamics in solution. Even though 1 μs molecular dynamics are not able to sample larger configurational changes that occur on the milliseconds to seconds scale, we hypothesize that the small conformational change observed in ERK2, compared to the other PKs, has a significant barrier responsible for ERK2 phosphorylation-dependent activation. This could explain that previous NMR studies showed two conformations in solution.14

Conformational Change in the L16 Loop.

A previous study by Xiao and collaborators14 monitored aliphatic side chains of Ile, Val, and Leu residues using NMR spectroscopy and showed that while 0P-ERK2 exhibits a unique conformation, 2P-ERK2 dynamics was fitted to a two-state model with a 20% population of state-1—presumably inactive 0P-ERK2-like—and 80% of state-2 which would be the biologically active state.14

Ile72, located in a central position of the αC helix, showed a significant change in chemical shift and also had a relationship between delta-omega (CPMG chemical shift) and kex that reflected a slow exchange on the NMR chemical shift time scale (kex ≪ delta-omega), which resulted in two distinct peaks, corresponding to each population. In the inactive structure, the Phe329 (located in the L16 loop) interacts with Ile72 δ-carbon and will thus be referred to the Phe-IN state. On the contrary, in the 2P-ERK2 X-ray structure, Ile72 side chain is exposed to the solvent since the L16 loop Phe329 ring is extended outward. We called that conformation the Phe-OUT state (Figure 2A). We hypothesized that the observed NMR change and the calculated populations could be due to the small conformational change observed in the L16 loop, due to the flipping of Phe329 from the Phe-IN to the Phe-OUT state.

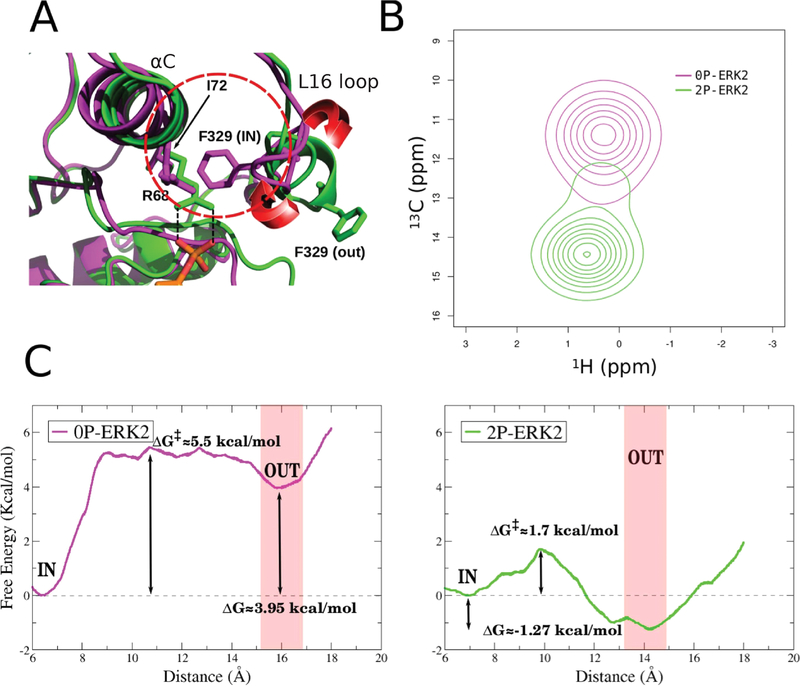

Figure 2.

Phe329 as a reporter of the conformational change. (A) Shell of Ile72 (red circle), the principal conformational change involves Phe329 rotation. The red arrows shows the direction of the 3/10 helix that regulates the Phe-IN/Phe-OUT conformation. (B) Computed HMQC peaks of 0P-ERK2 and 2P-ERK2 at 25 °C. (C) Free energy profile for folding−unfolding of the L16 loop using the distance between Ile72 (Cα) and Phe329 (Cα). Unphosphorylated ERK2 (0P-ERK2) and dual-phosphorylated ERK2 (2P-ERK2) are colored magenta and green, respectively.

To support our hypothesis that this Phe-IN to Phe-OUT change is partially responsible for the experimental observations, we first computed the Ile72 H–13C NMR shifts in both conformations using SHIFT2X.60 Our results, presented in Figure 2B, are in qualitative agreement with the experimental observations,14 showing the visible presence of two peaks. Second, we computed the free energy profile for the Phe-IN to Phe-OUT conformational transition using umbrella sampling (US) with the distance between Ile72 and Phe329 as the reaction coordinate, presented in Figure 2C. The resulting free energy difference between both conformations is remarkably consistent with the experimentally obtained populations: ΔG° = 3.10 kcal/mol for 0P-ERK2 and ΔG° = −0.80 kcal/mol for 2P-ERK2.14 The profile also shows that in 2P-ERK2 there is a relatively small barrier between both conformations (∼1.7 kcal/mol), while the inactive ERK2 moving to the Phe-OUT state has a barrier of ∼5.5 kcal/mol. These results strongly suggest that the NMR observed configurations and their populations could be explained by the small rearrangement of the L16 loop.

ERK2 Phosphorylation Stabilizes the Conserved Salt Bridge between Lys52 and Glu69.

To understand how ERK2 phosphorylation promotes its activation, we measured the free energy profile of a key salt bridge between Lys52 from strand β3 and Glu69 from αC helix in the holo (with ATP and 2Mg ions) forms of the active and inactive states (0P-ERK2-ATP and 2P-ERK-ATP) (Figure 3A). This salt bridge is highly conserved in the kinase family and is considered a hallmark of the activated state.56 In fact, it has been shown to be a great classifier of kinase conformations.59

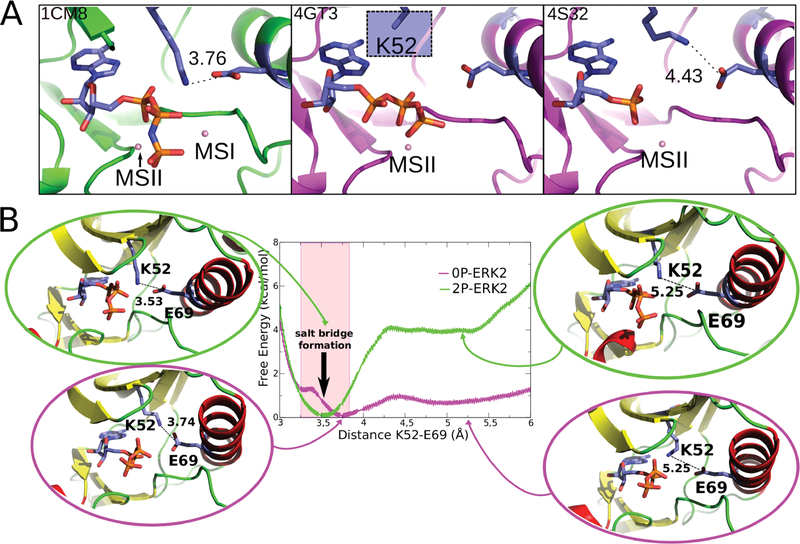

Figure 3.

Salt bridge formation between Lys52 and Glu69. (A) Representative crystallographic structures of MAPKs. 2P-P38γ (PDB ID: 1CM8; left), 0P-ERK2 (PDB ID: 4GT3, 4S32; center and right). The ligands are respectively ANP, ATP, and ANP (P-β and P-γ coordinates were not determined). The blue square (middle panel) highlights that for the Lys52 residue the side-chain is not resolved in the X-ray structure, probably due to its flexibility. (B) Free energy profile for salt-bridge formation. 0P-ERK2-ATP and 2P-ERK2-ATP are colored magenta and green, respectively. The Mg ions are not shown.

Figure 3B presents the classical free energy profile for breaking the salt bridge in both the 0P-ERK2-ATP and 2P-ERK2-ATP states. The curves were obtained by performing US simulations (see Methods) starting with the salt bridge formed at a distance of 3.5 Å and broken at 5.3 Å. The results clearly show that for inactive ERK2 (0P-ERK2-ATP) the salt bridge interaction free energy is minimal, since breaking it requires 1 kcal/mol, and there is a shallow minimum at ca. 5.2 Å. This result is indeed in agreement with the conformation observed in the inactive complexes (PDB IDs 4GT3 and 4S32). The first complex lacks the three distal atoms on the side chain as expected if a residue has increased flexibility, and in the second one the distance between Lys52 and Glu69 is 4.4 Å (Figure 3A). On the contrary, breaking this interaction in the 2P-ERK2-ATP complex requires 4 kcal/mol, and there is no other clear minimum. In other words, in the active state the salt bridge is established, while it is labile in the inactive state.

Impact of Lys52-Glu69 Salt Bridge Formation on the Phosphate Transfer Mechanism.

To evaluate the impact of the Lys52-Glu69 salt bridge on the phosphate transfer mechanism we first analyzed how it affects the Mg affinity. The effects of Mg binding (MSI) for all protein states were calculated according to the thermodynamic cycles shown in Figure S5. Interestingly, the presence of the salt bridge increases the MgI affinity in 8.6 kcal/mol, and most importantly, it retains the ATP-Pγ and the MgI in a proper “reactive” configuration. It is important to remark that this result qualitatively highlights that there is a correlation between the salt bridge formation and the affinity for the MSI Mg cation. This is in agreement with the experimental results. In the 0P-ERK2 state for the available X-ray structures (4GT3 and 4S32), the MgI is absent and the atoms involved in the interaction either are missing or too far. Supporting this hypothesis, the molecular dynamics of 0P-ERK2-ATP exhibit an incipient break of the coordination sphere of the MSI site, mainly due to the proximity of Glu69 to the Mg ion (Figure S10).

Second, and most important, we analyzed its effect on the energetics and mechanism of the phosphate transfer step, by computing with multiscale QM/MM MD simulations the corresponding free energy profiles using a tripeptide with a Thr phosphoacceptor as substrate. Figure 4 presents the corresponding results for the reactive conformation (2P-ERK2-ATP with the Lys52-Glu69 salt bridge properly established, Figure 4A), the same structure but mutating Lys52 for Alanine, thus removing the salt bridge (Figure 4B), and the conformation reached after losing the Mg ion in the MSI site (Figure 4C) of the 0P-ERK2-ATP state. Consistent with our hypothesis, breaking the Lys52-Glu69 interaction results in a small but significant increase in the reaction barrier (from 19.2 to 23.9 kcal/mol), and loosing the MgI in the unphosphorylated form raises it even more, to 29.0 kcal/mol.

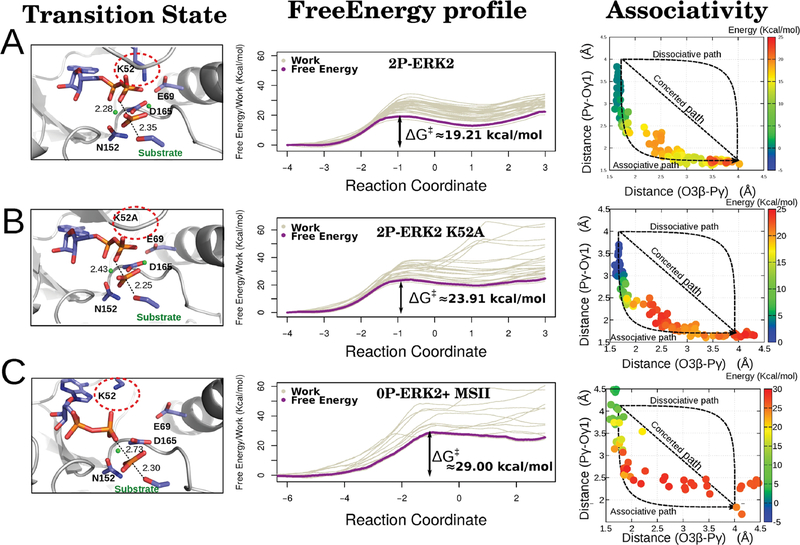

Figure 4.

Free energy profile and structural parameters of the phosphotransfer reaction in ERK2. The mechanism of the phosphorylation process was evaluated and characterized in the 2P-ERK2-ATP (A), 2P-ERK2-ATP K52A mutant (B), and 0P-ERK2-ATP (without the MgI ion) (C) states. For each setup we show the obtained transition state (left panel), the work for each run, and the global free energy (middle panel depicted in gray and purple, respectively). Finally, for each state an associativity plot, Pγ/O3β (substrate bond) vs Pγ/Oγ1 (product bond) distances, was computed (right panel), showing the corresponding free energy values in a color scale. The Mg ions are shown as green dots.

Concerning the reaction mechanism, as evidenced in the projection of the reaction coordinate onto the 2D RC plots (Figure 4, right panels), in all cases the reaction displays mostly an associative character. The phosphoacceptor must first come from its equilibrium distance to about 2.5 Å before the O3β-Pγ bond of the ATP starts to break. Interestingly, in the transition state (TS) region the reaction becomes dissociative-like, with the O3β-Pγ distance increasing from ca. 1.8 to 2.5 Å reaching the TS structure with a trigonal planar transferring phosphate, a geometry that has also been observed in crystal structures of other S/T kinases with transition state analogues.40,61

Comparatively, as the MSI site becomes disorganized when the salt bridge is broken, and finally lost, the active site becomes looser, a fact that is evidenced in the increasing dispersion of the individual work profiles, which contribute to an increase in the free energy barrier. Also interestingly, in the TS region, the reaction becomes more dissociative-like. In fact, in the absence of Mg2+ the substrate−Pγ bond is more often than not correctly established.

We propose that the Mg ions have a preponderant role in the reaction catalyzed by ERK2, stabilizing the transition state. Also, we have previously shown that a key step in the reaction is the proton transfer from the substrate Thr to the side chain of Asp147, which belongs to a highly conserved motif in the S/T kinases (HRD motif).17 In agreement, a similar behavior for the 2P-ERK2-ATP state is observed (Figure S11, panel A). While the active state presents a concurrent proton transfer step, in the inactive state, the transfer occurs later (Figure S11, panel C). We can also point out that in the inactive ERK2, the coordination sphere of the MSII site changes while the phosphotransfer reaction occurs (Figure S11 E,F).

DISCUSSION

Because of the enormous relevance of PKs, the underlying structural reasons that characterize their phosphorylation-dependent activation has been a significant area of research during the last decades. Analysis of hundreds of different active−inactive pairs of PKs structures yields several common features that presently describe, and define, how a PK is structurally activated. Phosphorylation in the activation segment loops usually triggers a reorganization of the more flexible C-terminal lobe, which rotates and closes with respect to the N-terminal lobe, thereby correctly “shaping” the ATP binding active site for catalysis. This closure is accompanied by the formation of both hydrophobic spines, the so-called Regulatory (R) and Catalytic (C) spines, which respectively define the active state and catalytic competent active site.

This conformational change is observed in several PKs, such as PKA, CDK2, or Src. Indeed recent works in JNK3 and p38 (both representatives members of the MAPKs superfamily) show the importance of the elucidation of the activation mechanism to drug design. Although the works describe and even identify possible intermediaries of the activation process, they do not show a direct relationship between the conformational change and the phosphorylation process.62,63 Also, we must consider that the hydrophobic spines in ERK2 are present in the inactive state, and thus other explanations are needed, highlighting the plasticity of the kinase domain.

In this work, we used multiscale free energy based molecular simulations of ERK2 to determine the key structural and dynamical features that explain how ERK2 phosphorylation is coupled to an over 50 000 times increase in its catalytic power. Consistent with the structural data, our results show both that inactive ERK2 and phosphorylated ERK2 display similar conformations, except for that of the L16 loop, and both states are mutually visited during equilibrium state molecular dynamics. Moreover, no significant rotation of helix-C or change in the size of the ATP binding pocket is observed. The R and C spines remain in a similar state and most residues, including those involved in catalysis, seem to be in a similar configuration. Taking all this into account we conclude that other, possibly smaller, but significant changes must regulate ERK2 kinase activation.

The best possible candidate can relate to previous NMR studies which showed the presence of two conformations (here referred to as Phe-IN and Phe-OUT), that shift their population upon phosphorylation. We were able to characterize this change at the atomic level, described mainly by the rotation of the L16 loop with the concomitant solvent exposure of Phe329 in the Phe-OUT state, which shifts the NMR signal of Ile72, as shown by Xiao et. al,14 and is the preferred state in phosphorylated ERK2. Remarkably, even though both the unphosphorylated and phosphorylated configurations are similar, the latest state significantly enhances the strength of the key Lys52-Glu69 (ERK2 numbering) salt bridge. This interaction correlates with a stabilization of the Mg2+ binding site I15 and retains ATP in a reactive conformation, therefore controlling the kinetic barrier of the phosphate transfer step (as summarized in Figure 5). In agreement with our results, recent work in PKA shows a change in the dihedral angle population between both states, for the same salt bridge.64 The fact that the nonphosphorylated ERK2 structure (PDB ID 4GT3) lacks the cation in the MSI site also supports our observation. Also interesting, the structure of CDK2 transition-state-like complex (PDB ID 3QHR), suggest that phosphate transfer occurs through an associative mechanism, as also displayed by our results for the Phe-OUT state (2P-ERK2), a characteristic that is partially lost in the Phe-IN state (0P-ERK).

Figure 5.

The activation of ERK2 kinase catalytic activity. Phosphorylation and reorganization of the activation loop promote kinase activation.

A relevant role for the interaction between the conserved Lys52 and Glu69 residues has been previously highlighted for other kinases. However, it has been mostly seen in the context of the above-mentioned major configurational rearrangement and not as the key factor governing activation.64–66 Phosphorylation of the activation loop stabilizes the Phe-OUT conformation and stabilizes the salt bridge necessary for proper catalysis. In agreement with our results, previous studies in Hog1 and p38α67–69 have shown that mutation of the conserved Phe residue to Leu in the L16 loop, which promotes stabilization of the Phe-OUT state, produces intrinsically active mutants and promotes dimerization. It has also been proposed that dimerization of ERK2, which has been linked to the Phe-OUT state, enhances catalytic activity and is essential for nuclear translocation.6

Taking our results in the context of previous works concerning the relationship between phosphorylation-dependent conformational changes and catalytic activity in PKs, we can argue that they employ different inactivation mechanisms, as already indicated by other authors.57,70 The assembly of the hydrophobic R and C spines with domain rotation and closure are important in several cases, but it must be considered that to increase the catalytic power, and thus kinase activity, these changes must result in either higher affinity for the substrates (ATP-phosphoacceptor) and/or lower barrier for the chemical step. Our results show that despite being small, the conformational change in ERK2 triggered by dual-phosphorylation results in the stabilization of the “biologically active” Phe-OUT state, increased binding of the MgI ion, and the formation of a key salt bridge.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Mehrnoosh Arrar for useful discussions. Computer time was provided by Centro de Computos de Alto Rendimiento (CeCAR), FCEN-UBA and TUPAC-CSC-CONICET. E.D.L., J.P.A., and L.A.D. acknowledge ANPCyT and CONICET, respectively, for postdoctoral fellowship. O.B. acknowledges ANPCyT and CONICET for doctoral fellowship. L.A.D., M.A.M., and A.G.T. are members of the CONICET. This work was supported by grants of ANPCyT (PICT 2015-2276) awarded to A.G.T.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

NOTE ADDED AFTER ASAP PUBLICATION

This article published November 27, 2019 with mistakes in Table 1. The corrected table published December 3, 2019.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00782.

0P-ERK2 and 2P-ERK2MD metrics and essential modes projection, Mg ion coordination information, C and R spine evaluation, US and MSMD validation (PDF)

Coordinates of the four ERK2 initial models (ZIP)

REFERENCES

- (1).Huse M; Kuriyan J The conformational plasticity of protein kinases. Cell 2002, 109, 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Hoshino R; Chatani Y; Yamori T; Tsuruo T; Oka H; Yoshida O; Shimada Y; Ari-i S; Wada H; Fujimoto J; Kohno M Constitutive activation of the 41-/43-kDa mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in human tumors. Oncogene 1999, 18, 813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Gioeli D; Mandell JW; Petroni GR; Frierson HF; Weber MJ Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase associated with prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 279–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Lawrence MC; Jivan A; Shao C; Duan L; Goad D; Zaganjor E; Osborne J; McGlynn K; Stippec S; Earnest S; Chen W; Cobb MH The roles of MAPKs in disease. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Uehling DE; Harris PA Recent progress on MAP kinase pathway inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 4047–4056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Canagarajah BJ; Khokhlatchev A; Cobb MH; Goldsmith EJ Activation mechanism of the MAP kinase ERK2 by dual phosphorylation. Cell 1997, 90, 859–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Robinson MJ; Harkins PC; Zhang J; Baer R; Haycock JW; Cobb MH; Goldsmith EJ Mutation of position 52 in ERK2 creates a nonproductive binding mode for adenosine 5 -triphosphate. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 5641–5646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Gonzalez FA; Raden DL; Davis RJ Identification of substrate recognition determinants for human ERK1 and ERK2 protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 22159–22163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Remenyi A; Good MC; Lim WA Docking interactions in protein kinase and phosphatase networks. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006, 16, 676–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Zhang F; Strand A; Robbins D; Cobb MH; Goldsmith EJ Atomic structure of the MAP kinase ERK2 at 2.3 Å resolution. Nature 1994, 367, 704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Cobb MH; Goldsmith EJ Dimerization in MAP-kinase signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25, 7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Nguyen T; Ruan Z; Oruganty K; Kannan N Co-conserved MAPK features couple D-domain docking groove to distal allosteric sites via the C-terminal flanking tail. PLoS One 2015, 10, No. e0119636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Barr D; Oashi T; Burkhard K; Lucius S; Samadani R; Zhang J; Shapiro P; MacKerell AD Jr; van der Vaart A Importance of domain closure for the autoactivation of ERK2. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 8038–8048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Xiao Y; Lee T; Latham MP; Warner LR; Tanimoto A; Pardi A; Ahn NG Phosphorylation releases constraints to domain motion in ERK2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 2506–2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Bao ZQ; Jacobsen DM; Young MA Briefly bound to activate: transient binding of a second catalytic magnesium activates the structure and dynamics of CDK2 kinase for catalysis. Structure 2011, 19, 675–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Madhusudan; Akamine P; Xuong N-H; Taylor SS Crystal structure of a transition state mimic of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2002, 9, 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Turjanski AG; Hummer G; Gutkind JS How mitogen-activated protein kinases recognize and phosphorylate their targets: A QM/MM study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6141–6148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sours KM; Xiao Y; Ahn NG Extracellular-regulated kinase 2 is activated by the enhancement of hinge flexibility. J. Mol. Biol. 2014, 426, 1925–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Prowse CN; Lew J Mechanism of activation of ERK2 by dual phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hari SB; Merritt EA; Maly DJ Conformation-selective ATP-competitive inhibitors control regulatory interactions and noncatalytic functions of mitogen-activated protein kinases. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 628–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Smith GK; Ke Z; Guo H; Hengge AC Insights into the phosphoryl transfer mechanism of cyclin-dependent protein kinases from ab initio QM/MM free-energy studies. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 13713–13722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).De Vivo M; Cavalli A; Carloni P; Recanatini M Computational study of the phosphoryl transfer catalyzed by a cyclin-dependent kinase. Chem. - Eur. J 2007, 13, 8437–8444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Cheng Y; Zhang Y; McCammon JA How does the cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalyze the phosphorylation reaction: an ab initio QM/MM study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 1553–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Montenegro M; Garcia-Viloca M; Lluch JM; González-Lafont À A QM/MM study of the phosphoryl transfer to the Kemptide substrate catalyzed by protein kinase A. The effect of the phosphorylation state of the protein on the mechanism. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 530–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zhang F; Strand A; Robbins D; Cobb MH; Goldsmith EJ Atomic structure of the MAP kinase ERK2 at 2.3 Å resolution. Nature 1994, 367, 704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Bellon S; Fitzgibbon MJ; Fox T; Hsiao H-M; Wilson KP The structure of phosphorylated p38γ is monomeric and reveals a conserved activation-loop conformation. Structure 1999, 7, 1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Case DA; Betz RM; Cerutti DS; Cheatham TE; Darden TA; Duke RE; Giese TJ; Gohlke H; Goetz AW; Homeyer N; Izadi S; Janowski P; Kaus J; Kovalenko A; Lee TS; LeGrand S; Li P; Lin C; Luchko T; Luo R; Madej B; Mermelstein D; Merz KM; Monard G; Nguyen H; Nguyen HT; Omelyan I; Onufriev A; Roe DR; Roitberg A; Sagui C; Simmerling CL; Botello-Smith WM; Swails J; Walker RC; Wang J; Wolf RM; Wu X; Xiao L; Kollman PA AMBER 2016; University of California, 2016.

- (28).Jorgensen WL; Chandrasekhar J; Madura JD; Impey RW; Klein ML Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Maier JA; Martinez C; Kasavajhala K; Wickstrom L; Hauser KE; Simmerling C ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3696–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Craft JW; Legge GB An AMBER/DYANA/MOLMOL phosphorylated amino acid library set and incorporation into NMR structure calculations. J. Biomol. NMR 2005, 33, 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Meagher KL; Redman LT; Carlson HA Development of polyphosphate parameters for use with the AMBER force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 1016–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Essmann U; Perera L; Berkowitz ML; Darden T; Lee H; Pedersen LG A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Berendsen HJ; Postma J. v.; van Gunsteren WF; DiNola A; Haak J Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Martyna GJ; Klein ML; Tuckerman M Nosé−Hoover chains: The canonical ensemble via continuous dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 2635–2643. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Hopkins CW; Le Grand S; Walker RC; Roitberg AE Long-time-step molecular dynamics through hydrogen mass repartitioning. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 1864–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Ryckaert J-P; Ciccotti G; Berendsen HJ Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977, 23, 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Steichen JM; Kuchinskas M; Keshwani MM; Yang J; Adams JA; Taylor SS Structural basis for the regulation of protein kinase A by activation loop phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 14672–14680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Akamine P; Madhusudan; Wu J; Xuong N-H; Eyck LFT; Taylor SS Dynamic features of cAMP-dependent protein kinase revealed by apoenzyme crystal structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 327, 159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Martin MP; Olesen SH; Georg GI; Schonbrunn E Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor dinaciclib interacts with the acetyllysine recognition site of bromodomains. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 2360–2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Bao ZQ; Jacobsen DM; Young MA Briefly bound to activate: transient binding of a second catalytic magnesium activates the structure and dynamics of CDK2 kinase for catalysis. Structure 2011, 19, 675–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Zhang X; Gureasko J; Shen K; Cole PA; Kuriyan J An allosteric mechanism for activation of the kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cell 2006, 125, 1137–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Xu W; Doshi A; Lei M; Eck MJ; Harrison SC Crystal structures of c-Src reveal features of its autoinhibitory mechanism. Mol. Cell 1999, 3, 629–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Azam M; Seeliger MA; Gray NS; Kuriyan J; Daley GQ Activation of tyrosine kinases by mutation of the gatekeeper threonine. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Rodriguez Limardo RG; Ferreiro DN; Roitberg AE; Marti MA; Turjanski AG P38γ activation triggers dynamical changes in allosteric docking sites. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 1384–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Grossfield A WHAM: the weighted histogram analysis method, version 2.0.9; University of Rochester Medical Center http://membrane.urmc.rochester.edu/wordpress/?page\_id=126.

- (46).Kaus JW; Pierce LT; Walker RC; McCammon JA Improving the efficiency of free energy calculations in the amber molecular dynamics package. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 4131–4139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Steinbrecher T; Joung I; Case DA Soft-core potentials in thermodynamic integration: Comparing one-and two-step transformations. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 3253–3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Shirts MR; Chodera JD Statistically optimal analysis of samples from multiple equilibrium states. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 129, 124105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Cui Q; Elstner M; Kaxiras E; Frauenheim T; Karplus M A QM/MM implementation of the self-consistent charge density functional tight binding (SCC-DFTB) method. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 569–585. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Crespo A; Martí MA; Estrin DA; Roitberg AE Multiple-steering QM- MM calculation of the free energy profile in chorismate mutase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 6940–6941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Defelipe LA; Lanzarotti E; Gauto D; Marti MA; Turjanski AG Protein topology determines cysteine oxidation fate: the case of sulfenyl amide formation among protein families. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, No. e1004051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Forti F; Boechi L; Estrin DA; Marti MA Comparing and combining implicit ligand sampling with multiple steered molecular dynamics to study ligand migration processes in heme proteins. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 2219–2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Xiong H; Crespo A; Marti M; Estrin D; Roitberg AE Free energy calculations with non-equilibrium methods: applications of the Jarzynski relationship. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2006, 116, 338–346. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Issoglio FM; Campolo N; Zeida A; Grune T; Radi R; Estrin DA; Bartesaghi S Exploring the catalytic mechanism of human glutamine synthetase by computer simulations. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 5907–5916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Jarzynski C Nonequilibrium equality for free energy differences. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 2690. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Taylor SS; Kornev AP Protein kinases: evolution of dynamic regulatory proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 36, 65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Meharena HS; Chang P; Keshwani MM; Oruganty K; Nene AK; Kannan N; Taylor SS; Kornev AP Deciphering the structural basis of eukaryotic protein kinase regulation. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, No. e1001680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Kornev AP; Taylor SS Defining the conserved internal architecture of a protein kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2010, 1804, 440–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).McSkimming DI; Rasheed K; Kannan N Classifying kinase conformations using a machine learning approach. BMC Bioinf. 2017, 18, 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Han B; Liu Y; Ginzinger SW; Wishart DS SHIFTX2: significantly improved protein chemical shift prediction. J. Biomol. NMR 2011, 50, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Madhusudan; Akamine P; Xuong N-H; Taylor SS Crystal structure of a transition state mimic of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2002, 9, 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Mishra P; Günther S New insights into the structural dynamics of the kinase JNK3. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Kuzmanic A; Sutto L; Saladino G; Nebreda AR; Gervasio FL; Orozco M Changes in the free-energy landscape of p38α MAP kinase through its canonical activation and binding events as studied by enhanced molecular dynamics simulations. Elife 2017, 6, No. e22175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Ahuja LG; Kornev AP; McClendon CL; Veglia G; Taylor SS Mutation of a kinase allosteric node uncouples dynamics linked to phosphotransfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, E931–E940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Bastidas AC; Deal MS; Steichen JM; Guo Y; Wu J; Taylor SS Phosphoryl transfer by protein kinase A is captured in a crystal lattice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 4788–4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Meharena HS; Fan X; Ahuja LG; Keshwani MM; McClendon CL; Chen AM; Adams JA; Taylor SS Decoding the interactions regulating the active state mechanics of eukaryotic protein kinases. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, No. e2000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Bell M; Capone R; Pashtan I; Levitzki A; Engelberg D Isolation of hyperactive mutants of the MAPK p38/Hog1 that are independent of MAPK kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 25351–25358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Diskin R; Askari N; Capone R; Engelberg D; Livnah O Active mutants of the human p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 47040–47049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Diskin R; Lebendiker M; Engelberg D; Livnah O Structures of p38α active mutants reveal conformational changes in L16 loop that induce autophosphorylation and activation. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 365, 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Roskoski R Jr, Src protein-tyrosine kinase structure, mechanism, and small molecule inhibitors. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 94, 9–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.