Search terms for recovery applications yielded 102 apps promoting alcohol and illicit substance use. These apps leveraged effective software design, marketing and social networking.

Keywords: Smartphone applications, Alcohol, Illicit substance use, Harmful

Abstract

Few studies have conducted analysis of commercially available smartphone applications designed to promote alcohol and illicit substance use. The aim of this review is to determine harmful themes of content in applications promoting alcohol and illicit substance use found using recovery app search terms. A systematic search, via Apple iTunes and Google Play stores, was conducted of applications targeting abstinence or reduced substance use in online app stores (n = 1,074 apps) in March 2018. We conducted a secondary analysis of apps encouraging alcohol and illicit substance use in July 2018. Our initial search yielded 904 apps pertaining to alcohol and illicit substance use. Four reviewers conducted a content analysis of 102 apps meeting inclusion criteria and assessed app design, delivery features, text, and multimedia content pertaining to substance use. The initial coding scheme was refined using a data-driven, iterative method grouping in thematic categories. The number of apps coded to a specific substance include: alcohol (n = 74), methamphetamine (n =13), cocaine (n = 15), heroin (n = 12), and marijuana (n = 15), with nine apps overlapping more than one substance. Key themes identified among apps included: (i) tangibility (alcohol home delivery services); (ii) social networks (builtin social media platforms promoting substance use); (iii) software design (gamification or simulation of substance use); and (iv) aesthetics (sexual or violent imagery). Despite claims of restricting apps promoting substance use, further efforts are needed by online app stores to reduce the availability of harmful content.

Implications.

Practice: The increased popularity of digital media (i.e., social media, online forums, and smartphone applications) has helped encourage the commercial promotion of alcohol and illicit substances with limited government oversight.

Policy: Currently, there is limited regulation of smartphone application content promoting alcohol and illicit substance.

Research: Future research should be done to assess the detrimental impact of harmful apps on alcohol and illicit substance use.

INTRODUCTION

Reducing the burden of substance use disorders (SUDs) remains a critical public health goal in the United States [1]. Exposure to media promoting alcohol and other substance use contributes to risky behaviors and has a negative effect among those with smartphone devices [2]. In 2018, nearly half of all smartphone and tablet users had downloaded mHealth applications [3] and it is important to limit exposure to harmful media content (e.g., billboards, television ads) to effectively reduce alcohol use and smoking [4,5]. However, the popularity of digital media, including social media, online forums, and smartphone applications, has facilitated the commercial promotion of alcohol and tobacco products with limited government oversight [6,7].

Approximately three-quarters of Americans now own smartphones (77%) and smartphones are nearly ubiquitous among 18- to 29-year-olds (92%) [8]. Smartphones offer advanced hardware and software features that are uniquely positioned to enhance health outcomes for populations with SUDs [9–11]. A November 2017 report estimated the availability of more than 318,000 mobile health related (mHealth) apps [10]. Guidelines outlined by Apple and Google Play have attempted to reduce the availability of apps that promote alcohol, tobacco, or illicit substance related content [12,13]. Quality and patient safety concerns with emerging mHealth apps have also led to recent FDA regulations and expert guidelines directing users and health systems to evidence-based apps [14].

In March 2018, we conducted a systematic search of free smartphone applications that encourage recovery from illicit substance use or alcohol. Only two smartphone applications, FlexDek MAT and STOP OD NYC, particularly focused on the use of opioids using evidence-based content (e.g., opioid use disorders [OUD] pharmacotherapies) [15]. However, we found many apps that were deceptive or harmful.

Despite efforts to expand the availability of evidence-based apps to reduce SUDs, studies suggest the growth of apps encouraging cigarette [16], cannabis [17], and alcohol use [18,19]. BinDhim et al. [20] searched for “cannabis, weed, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, and ecstasy” and identified 238 apps in February 2012 and 410 apps in May 2012 that met inclusion criteria. Apps facilitated contact with other users, utilized role-playing as drug dealers, users, or farmers, and simulated drug preparation and use [21]. Among 384 alcohol-related apps identified by Weaver and colleagues in 2012, most were for entertainment purposes (e.g., drinking games [n = 67], drink-making recipes (n = 60), and bar or liquor store locators [n = 17]) [18]. Ramo and colleagues evaluated 59 cannabis-related apps in 2014 and categorized content areas to cannabis strain classification (33.9%), cannabis information (20.3%), and games (20.3%); only one app was designed to reduce cannabis use [17]. With 200 new apps entering the marketplace daily, there is limited information regarding the number and quality of emerging smartphone apps exacerbating alcohol and illicit substance use [10].

The purpose of this study was to perform a secondary analysis of all the harmful apps incidentally found during this March 2018 systematic review of recovery-focused smartphone applications. The aims of this study were to characterize harmful apps encouraging substance use and conduct content analysis (e.g., games promoting use, networking with actively using peers, locating or procuring substances, simulated use).

METHODOLOGY

Choosing search terms

Strategies used to identify free apps included: (i) keywords described in prior studies evaluating alcohol and illicit substance-related smartphone apps (i.e., “alcohol, benzodiazepine, cannabis, cocaine, crack/cocaine, methamphetamine [17,18]”; and (ii) app search terms described by individuals diagnosed with opioid, alcohol, cocaine, benzodiazepine, and/or crack/cocaine use disorders in recent qualitative surveys (e.g., “sober, sobriety, recovery, drugs, dope, withdrawal [21].” Terms that could refer to something other than the intended substance (e.g., Jelly Babies, Coke, Snowflake, White, Blue) were excluded due to the limited relevance of the apps that emerged from the search.

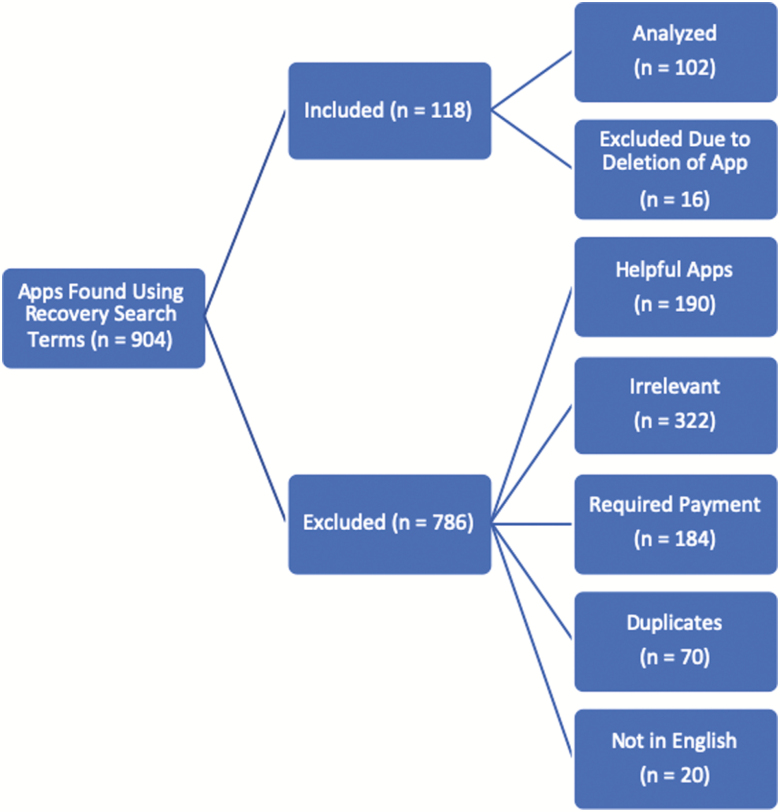

Search terms were entered in Apple iTunes and the Google Play websites in March 2018. We conducted a secondary analysis of apps that encouraged alcohol and illicit substance use in July 2018. Our initial search yielded 904 apps that pertained to alcohol and illicit substance use [15]. Our secondary analysis of these apps identified 118 apps that were related to harmful substance use. We excluded apps that were related to reducing substance use (n = 190), appeared to be irrelevant (n = 322), required payment for use (n = 184), were duplicates (n = 70), and not in English (n = 20). Apps were considered irrelevant if upon initial analysis they appeared to have no content related to either alcohol use or substance use. We also excluded all apps that were deleted from app stores between the time of the first paper and this project (n = 16). At the time of analysis we discovered 30 Google play apps and 72 iTunes apps (Table 1).

Table 1.

Consort chart

Defining harmful content

Our definition of harmful content included any app that explicitly provided information about brands of substances, where to buy or procure substances, images of alcohol brands or legalized brands of cannabis, games related to growing or selling illicit substances, and apps that might encourage use behavior by providing trigger cues. All apps listed in the search results that were not duplicates of prior searches were evaluated for inclusion in the study. We did not evaluate any apps twice, even if they appeared due to multiple search terms. The number of apps that met inclusion criteria and underwent further analysis were comparable to prior studies of alcohol [18] and cannabis-related apps [17].

Coding scheme

The study team developed a coding scheme based on prior studies that assessed for key design features of harmful smartphone apps related to SUDs [16,18,22]. Key design features included: (i) Peer use (apps that facilitated contact with other active users and/or promoted behavior change). This was defined as apps designed to increase alcohol and substance use via peer networks to encourage drinking/substance use); (ii) Self-administration (instructions on methods of using drugs to maximize its euphoric effects); (iii) Games (themed around accessing and/or using the drug); (iv) Informational (pictures, videos, and videos intended to inform potential users about substance varieties); (v) Access (solely to procure the substance, including drug dealers, bars, open air drug markets, delivery services); (vi) Use locations (e.g., bars, parties); (vii) Laws pertaining to select substances (including in any U.S. state or another geographic region); (viii) Harm reduction, treatment, recovery content (e.g., nonevidence-based recovery advice or apps inappropriately labeled as safety applications); (ix) Virtual simulation (e.g., self-administering a substance); and (x) Personal information (collection of any identifiable information at sign-up, GPS data, links to social media, personal preferences).

Content analysis

All apps that met inclusion criteria were downloaded onto an Apple or Android smartphone and reviewed independently by the study team (S. Ghassemlou, B. Tofighi, C. Marini). To ensure the methodological rigor of the study and understanding of review criteria among the study team, weekly meetings were convened to discuss app findings, assess the quality of the reviews, and address potential discrepancies. In addition, the senior author (B. Tofighi) reviewed 20% of the apps that met inclusion criteria to ensure consistency with the descriptive analysis guidelines.

RESULTS

Our preliminary search of online app stores (i.e., Google Play, iTunes) identified 582 apps in iTunes and 492 apps in Google Play. An initial review of app titles, descriptions, and further inspection of downloaded apps by the study team categorized 102 apps that met eligibility criteria for promoting substance use. After the initial content analysis was completed, the primary author performed a secondary analysis of the data, generating thematic categories to describe the general trends and patterns highlighted in our search.

We elicited four themes based on tangibility (i.e., enhancing access to substances), social networks (i.e., integration of Facebook, Instagram, and other social media platform or linkage with actively using peers within app forums and messaging features), software design (i.e., use of push notifications, simulating substance use, gamification of substance use), and aesthetics (i.e., sexual imagery, cartoon designs appealing to children, promotion of violence, deceptive labeling, or designs in app stores; Table 2). An explanation of each theme and relevant apps are described below.

Table 2.

Evaluated apps by category (n = 102)

| Category | Subcategory | Number of apps | Percent of apps (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tangibility | Delivery apps | 8/102 | 8 |

| Happy | 14/102 | 14 | |

| Hour/bar/party/event | |||

| Finder | |||

| Retail deals | 6/102 | 6 | |

| Social networks | Integration with existing social media platforms | 39/102 | 38 |

| Built-in peer use platform | 21/102 | 21 | |

| Software design | Gamification of substance use | 44/102 | 43 |

| Simulating substance use | 4/102 | 4 | |

| Use of push notifications | 23/102 | 23 | |

| Aesthetics | Deceptive purpose | 9/102 | 9 |

| Apps | |||

| Informational | 2/102 | 2 | |

| Sexual imagery | 3/102 | 3 | |

| Cartoon-like aesthetics | 19/102 | 19 | |

| Violent imagery | 10/102 | 10 |

Tangibility

We defined tangibility as any app that gives you the substance in your hand. This includes a delivery service, mail service, or any application which provided users with locations to purchase and/or use illicit substance or alcohol. Numerous apps (n =28) facilitated home delivery of alcohol (e.g., Banquet, Buttery, Drizly, HipBar Delivery, Minibar Delivery, Refill, Saucey, and Swill), locating happy hours and bars (e.g., Bottles Tonight, Happy Hour Finder, Happy Hour Now, Toro, and Cocktail Compass), or retail liquor stores advertising discounts (e.g., Hooch, Partiac, and Party Tutor). For instance, Refill: On Demand Delivery, is an alcohol delivery service that claims home delivery of alcohol in less than 30 min. Party Tutor targeted college students and connects users to cheap or free alcohol near college campuses (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Party Tutor.

Social networks

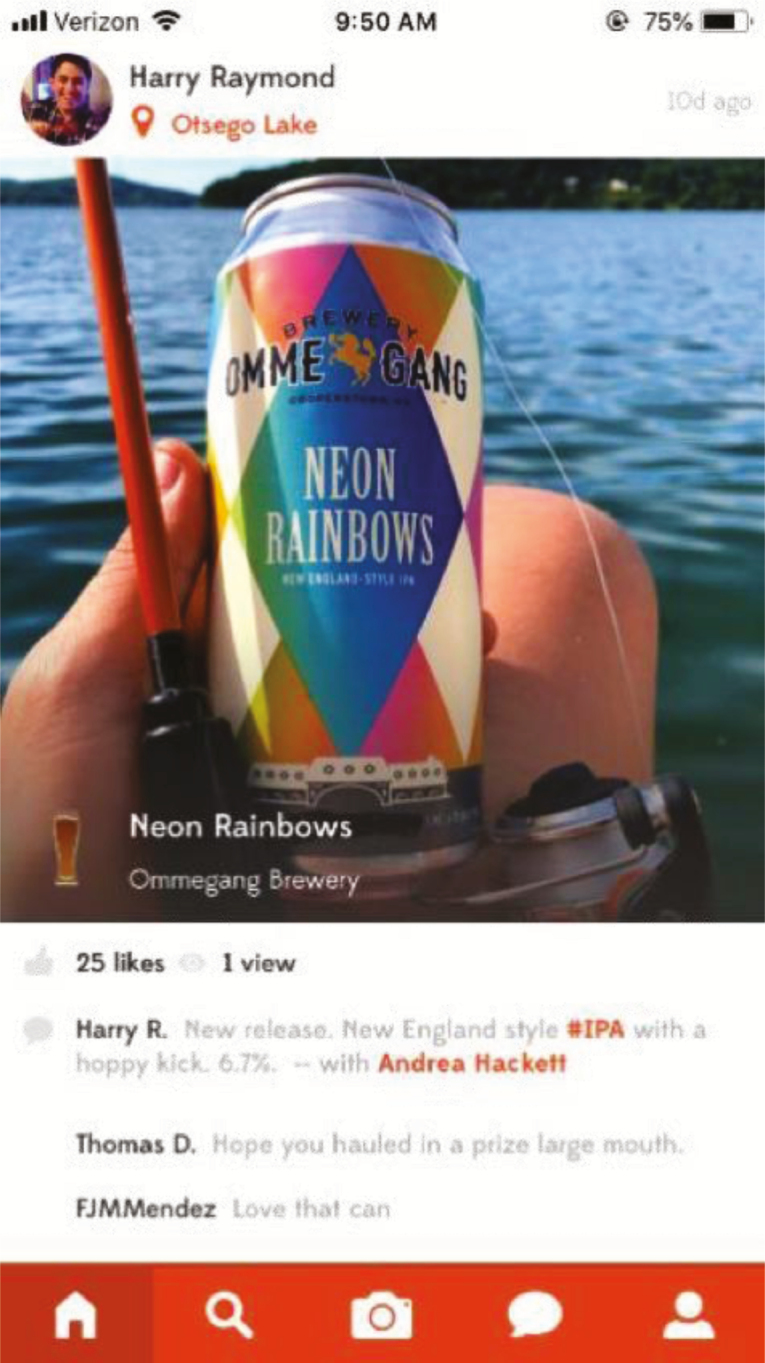

App requests for access to user’s social media accounts was common (n = 39) and included Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram (e.g., Swig, Saucey, Hooch). Apps leveraged user’s social networks by placing ads on user’s main profile page or sending invitations to the user’s network of “friends” network to download the app. Other apps such as iPuke, facilitated posting pictures during binge drinking episodes on the app via Instagram while promoting the app using a suggested hashtag. Other apps did not require the use of social media accounts but promoted peer contact to enhance user experience. For instance, Hooch, Saucey Alcohol Delivery and Swill, offered deals and incentives to users who referred the app to friend.

Apps also encouraged users to engage with peers to: (i) locate others nearby to drink with (e.g., Drunk Mode Call Blocker, Swig); (ii) share recommendations and experiences with different substances (e.g., Barreled, Distiller, Erowid Navigator Improved); (iii) upload photos while intoxicated on public walls for peer ratings (i.e., “like,” “dislike,” or “love”; e.g., Swig; Fig. 2). Our review did not find any apps facilitating peer use of cannabis and illicit substances.

Fig 2.

Swig.

In regard to recovery, several apps used deceptive descriptions of recovery resources but would bombard users with pop-up advertisements (e.g., Sobriety Clock, Stop Drinking Alcohol now), making users log into social media platforms like Facebook or grant access to social media networks along with asking for each user’s specific location [16].

Software design

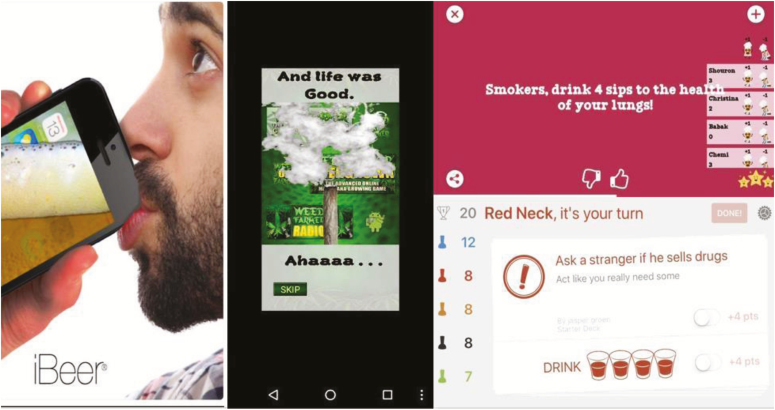

Of the 102 harmful apps evaluated, 44 of the apps gamified substance use via: (i) competitions with peers to achieve the highest quantity of drinks or blood alcohol levels (e.g., iPuke, Drinkopoly, Piccolo, drnkApp); (ii) collecting points from peers rating how unique the user’s drinking experience (e.g., Swig); and (iii) drinking games that instructed users to drink more if they failed to complete a dare or task (e.g., iPuke, Piccolo Drinking Game). Drinkopoly also gamified users to drink further if they smoked any cigarettes during their social event (Fig. 3). Only some of the apps categorized by the study team as games were correctly labeled as games in online app stores and designated for adults over the age of 21. In addition, 23 apps that met inclusion criteria sent push notifications. For instance, Hempire regularly sent notifications at 4:20 pm reminding users to “light up” [cannabis].

Fig 3.

iBeer, Weed Farm Dealer, Drinkopoly, iPuke.

Other apps simulated the self-administration of substances by drinking alcohol from a glass (e.g., iBeer and Virtual Beer), rolling a joint (e.g., Weed Farm Dealer), or simulated the desired effect of the substance (Fig. 3).

Aesthetics

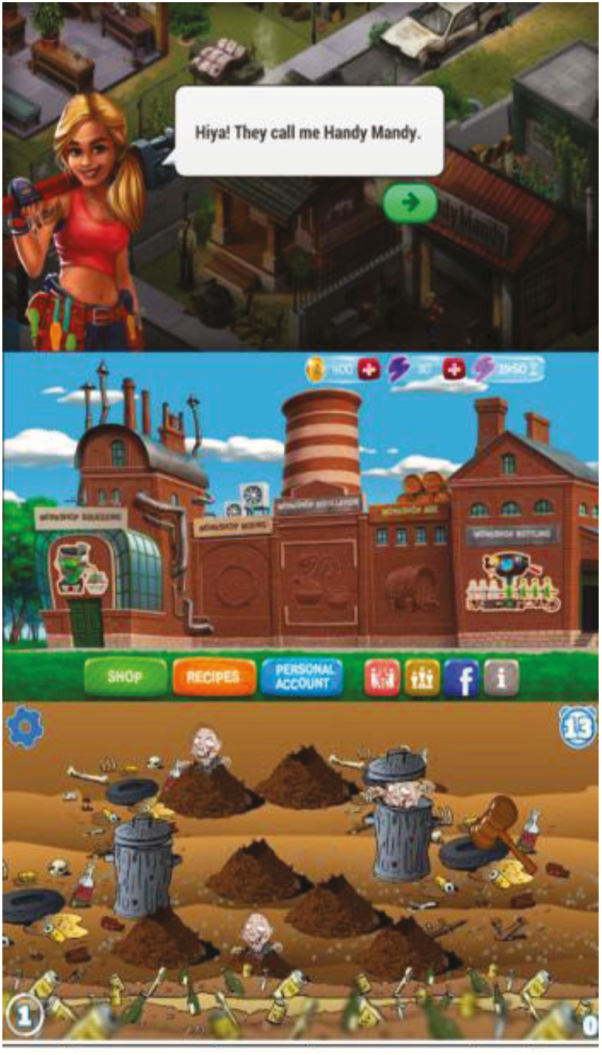

The use of cartoon aesthetics for youth and sexual imagery was also elicited in this review (n = 22). Hempire gamifies cannabis farming and sales but randomly inserts an attractive female character in revealing clothing named “Handy Mandy” (Fig. 4). Other apps used bright colors and basic shapes to create cartoon-like images (e.g., Alcohol Factory Simulator, Drunk-Fu: Wasted Masters, Drunk Wrestlers 3D-Toribash Gang, and Weed Tycoon). Alcohol Factory Simulator offers users an assembly line where squeezing, mixing, distilling, and bottling alcohol (Fig. 4). We found 10 apps included in our review that promote substance use and acts of physical violence (e.g., Drunk-Fu, Drunk Wrestlers, and Whack a Crack Head). The explicit use of violence was gamified for users by allowing the purchase of virtual weapons or assaulting other characters (e.g., Narcos: Cartel Wars, Drunk-Fu). The Whack a Crack Head app adopted the childhood game “Whack a Mole” and incentivized beating zombie-like addict cartoon characters until they were bleeding from their eyes (Fig. 4). Particularly concerning was Party Game which encouraged users to force another individual to kiss them.

Fig 4.

Hempire, Alcohol Factory Simulator, Whack a Crack Head.

Several apps were inappropriately advertised as “safety apps” claiming to offer access to taxi services or raising user awareness of safe drinking via frequent blood alcohol level assessments (n = 9) but instead promoted binge drinking (e.g., Cocktail Compass, Drunk Mode-Call Blocker). Apps that claimed to inform users of blood alcohol levels used inaccurate assessments, offered humorous content to promote further drinking, and in some instances assured users whether they could drive based on the app’s devised scoring (e.g., Party Pacer). Two apps provided pictures, videos, and text content about varieties of substances or laws restricting or permitting the use of select substances. Cocaine 3D informed users about the neuropharmacology of cocaine and how to self-administer it to induce optimal euphoric effects.

DISCUSSION

Apps promoting substance use were readily available in online app stores after using search terms pertaining to recovery and specific substances (i.e., alcohol, cocaine, heroin). Apps were available under different app categories (i.e., “Entertainment,” “Games,” “Health and Fitness”) without consistent restrictions pertaining to age. The use of sexual imagery, violence, peer networks, social media, deceptive labeling and descriptions, and app software design promoting engagement (push-notification) highlights a disturbing abundance of free and available apps promoting harmful drinking and illicit substance use.

Tangibility

Delivery apps, such as Banquet, Buttery, Drizly, HipBar Delivery, Minibar Delivery, Refill, Saucey, and Swill all offer home-delivery of alcohol. Further research is needed exploring how those with alcohol use disorders are using these smartphone applications which provide tangibility. However, apps provide easy access to individuals that may be too intoxicated or ashamed or under-aged to purchase alcohol in-person. A qualitative study of Silk Road users, an online drug marketplace that was discontinued by the FBI in 2013, via anonymous online interviews and analysis of discussion threads on the site suggested that the anonymity of transactions and home delivery of illicit substances eased access compared with obtaining drugs in-person [23].

Despite the FBI’s closure of Silk Road, subsequent websites have been relaunched as Silk Road 2.0 and Silk Road 3.0 highlighting the popularity of online drug sales [24]. Similarly, apps and online platforms may circumvent effective policies reducing alcohol intake (e.g., higher minimum drinking ages, restrictions on alcohol retailers, and operating hours) [25].In addition, Happy Hour and bar finder apps such as Bottles Tonight and Happy Hour Finder offer coupons, promotions, and linkages with other active drinkers that are useful marketing strategies to increase consumption but risk relapse and harmful drinking patterns [26].

Social networks

Drinking apps frequently solicited users for access to popular social media accounts, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, and exposed user’s social networks to the app and images of high-risk behaviors (e.g., Swig, Wine Ring). The near-ubiquitous penetration of social media among younger social networks has intensified exposure to marketing campaigns promoting substance use. Companies normalize substance use with positive-themed images (i.e., sociability, success) along with opportunities to connect with peers via chat rooms, bulletin boards, and links to social media marketing campaigns to share experiences with the brand [27]. Sherman et al. [28] conducted an fMRI study of adolescents viewing photos posted in a social media account resulting in greater activation of brain regions involved in alcohol-related reward processing and imitation. Recent studies have found that engagement with alcohol- and tobacco-marketing content on social media was predictive of increased alcohol consumption, problem drinking, and tobacco use among young adults [29]. Despite these concerning findings, apps available in Apple and Google Play app stores promote substance use, violate national and international restrictions and require further scrutiny and restrictions by public health organizations and online app stores [16,20].

Clearly public health organizations are lagging commercial and illicit interests expanding social media and app-based access to alcohol and illicit substances. Nonetheless, recent efforts by researchers to leverage smartphone apps and social media to reduce smoking and alcohol among young adults have demonstrated promising findings [4,27–29]. Further studies are needed to assess the clinical impact (e.g., abstinence, harm reduction, treatment utilization) of apps developed by public health organizations now available in online app stores (e.g., StopOD NYC).

Software design

Of the 102 harmful apps evaluated, 44 of the apps gamified substance use and mostly consisted of drinking games. Other apps that were not marketed as games had game-like features that utilized motivating feedback, such as cheerful sounds, animation informing users about their excessive substance use in a festive or rewarding manner, utilizing a point system, and providing extrinsic motivation via peer networks to continue their behavior [30]. Similar findings have emerged for pro-smoking smartphone applications that gamify or simulate smoking and risk enhancing initiation of cigarette smoking behavior among younger users [16]. Further studies are needed to assess the effect of simulations and games related to alcohol and illicit substances on actual use.

Aesthetics

The use of sexual and cartoon-like imagery is aligned with prior studies of alcohol advertisements that utilized “youth-appealing content” and were correlated with higher sales among youth [31]. Another study found that sexually provocative models were 65% more likely to be displayed in magazines targeted to young adults than in magazines targeted to their adult counterparts [32]. In addition, the use of celebrities and popular icons (e.g., Wiz Khalifa, Pablo Escobar) or television series (e.g., Narcos, Breaking Bad) are aligned with prior studies highlighting their influential effect on youth tobacco and alcohol-related beliefs, intentions, and behavior [33,34]. Lastly, the use of physical violence by approximately 10% of apps included in this study (e.g., Drunk-Fu, Whack a Crack Head, Gangster Paradise, Narcos: Cartel Wars) and sexual violence while intoxicated (e.g., Drinking Game—Truth or Dare) highlight effective strategies to enhance attention to products and brand recall [34].

Recommendations

Governments and online app stores must take further steps to restrict access to apps and developers that intentionally utilize deceptive practices (e.g., incorrectly categorizing harmful apps as “entertainment,” “games,” or “health” apps, or for age groups below 21 years old).

An implication for digital health policy within the United States is to promote the development of more evidence-based recovery smartphone applications for patients with substance use disorder. Currently as mentioned above, there are only two recovery apps that are evidence-based (FlexDek MAT and STOP OD NYC) and there is a need for more to provide essential tools to aid in patient recovery.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. Search terms were limited to apps that would facilitate recovery rather than harmful use. Moreover, the search was limited to free apps. The study team was unable to assess the extent users engaged with apps over time since this information is not available in online app stores or within the app program itself. Since many of these apps were newly developed and only recently made available on the online app stores, they were not rated or lacked any user comments. As a result, we excluded this data due to incompleteness. The study was conducted in March 2018 and does not include apps that have been uploaded since the initial search period.

CONCLUSION

Apps promoting alcohol and illicit substance use are leveraging effective software design, marketing, and social networking approaches to reach millions of online app store users with no access restrictions for younger age groups. Efforts by governments and online app stores are needed to restrict access to harmful apps. Studies are needed to assess the detrimental impact of harmful apps on alcohol and illicit substance use. Additional studies are urgently needed to explore user experience with these apps and their potential implications for substance use.

Acknowledgements

B. Tofighi is supported by a NIH Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (NIDA K23DA042140-01A1) and Clinical Translational Science Award (UL1 TR001445). C. Marini and S. Ghassemlou were supported by a NIDA Education Projects grant (R25DA022461-11). The publication of this article is timely given the rapid increase of smartphone use among Americans and focuses on applications that encourage substance use or alcohol consumption among both children and adults. It is recommended to increase government involvement in the restriction of apps that negatively impact health and contribute to risky behaviors. Thank you very much for your reconsideration, and please let me know if you have any questions.

APPENDIX

| Name of app | Alcohol | Meth | Cocaine | Heroin | Marijuana |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8,500+ drink recipes | 1 | ||||

| Alcohol Factory Simulator | 1 | ||||

| Alcohol Test (joke) | 1 | ||||

| Alcohol Tester Prank: Drunkenness Calculator | |||||

| Prank | 1 | ||||

| Appy Hour | 1 | ||||

| Banquet-Shop Top Wine Stores by Delectable | 1 | ||||

| BarNotes—social cocktail and drink recipes | 1 | ||||

| BarPass Better Happy Hours | 1 | ||||

| Barreled: The Social World of Whiskey | 1 | ||||

| Beer Pong Drop | 1 | ||||

| Beer Pong Game | 1 | ||||

| Beer Pong HD Drinking Game | 1 | ||||

| Beer Pong Party | 1 | ||||

| Beer Pong Trick | 1 | ||||

| Beer Pong: Trickshot | 1 | ||||

| BeerPong Extreme Free | 1 | ||||

| Bottles Tonight | 1 | ||||

| Breaking Bad Quizzes | 1 | ||||

| Buttery—Alcohol Delivery | 1 | ||||

| Camper Van Meth Lab: Breaking Bad RV Truck | |||||

| Driving | 1 | ||||

| Cartel mogul | 1 | ||||

| Circle of Death Drinking Game | 1 | ||||

| Clicking Bad | 1 | ||||

| Cocaine 3D | 1 | ||||

| Cocktail Compass | 1 | ||||

| Cocktail Flow | 1 | ||||

| Distiller | 1 | ||||

| Dope Inc | 1 | ||||

| Dope Wars Classic | 1 | ||||

| Dope Wars: Weed Edition | 1 | ||||

| Drink and Tell—Drinking Game | 1 | ||||

| Drink poly-drinking games | 1 | ||||

| Drink Roulette—Drinking Game | 1 | ||||

| Drink-o-Tron: Drinking Game | 1 | ||||

| Drinkards—The Drinking Game | 1 | ||||

| Drinking Game for Crazy Adult | 1 | ||||

| Drinking game for crazy adults | 1 | ||||

| Drinking Game—Truth or Dare (Alcohol Edition) | 1 | ||||

| Drinking games Houseparty 18+ | 1 | ||||

| Drizly—Alcohol Delivery | 1 | ||||

| drnkApp—alcohol calculator | 1 | ||||

| Drug Lord 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Drunk Meter | 1 | ||||

| Drunk Mode—Call Blocker | 1 | ||||

| Drunk Potatoe: Drinking Game | 1 | ||||

| Drunk Run | 1 | ||||

| Drunk Tester Game | 1 | ||||

| Drunk-Fu: Wasted Masters | 1 | ||||

| Drunken Wresters 3D- Toribash Gang | 1 | ||||

| Erowid Navigator Improved | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Flappy Junky | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Fun Finder happy hour specials | 1 | ||||

| Gangster Paradise | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Green light FREE-blood alcohol level calculator | 1 | ||||

| Happy Hour Finder | 1 | ||||

| Happy Hour Now | 1 | ||||

| Hempire—Weed Growing Game | 1 | ||||

| Highball by Studio Neat | 1 | ||||

| HipBar Delivery | 1 | ||||

| Hooch | 1 | ||||

| I’m Drug Dealer | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| iBeer | 1 | ||||

| Impressions—a drinking game | 1 | ||||

| Interactive Cocktail Recipe | 1 | ||||

| iPuke: the drinking game | 1 | ||||

| iStoner Free | 1 | ||||

| Let’s get WASTED! Drinking Game | 1 | ||||

| M.E.T.H | 1 | ||||

| Mafia City | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Minibar Delivery | 1 | ||||

| Mixidrink | 1 | ||||

| Mixology: Drink & Cocktail Recipes | 1 | ||||

| My Cocktail Bar | 1 | ||||

| Narcos Escape | 1 | ||||

| Narcos: Cartel Wars | 1 | ||||

| NightOwl: Bars and Nightlife | 1 | ||||

| Partender—Bar Inventory | 1 | ||||

| Partiac | 1 | ||||

| Party Alcohol Calculator Free | 1 | ||||

| Party Pacer | 1 | ||||

| Party Tutor | 1 | ||||

| Piccolo Drinking Game | 1 | ||||

| Prison Break: The Great Escape | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Refill: On Demand Delivery | 1 | ||||

| Saucey Alcohol Delivery | 1 | ||||

| Swig | 1 | ||||

| Swill—Simple Fast Alcohol Delivery The Liquor | |||||

| Store in Your Pocket | 1 | ||||

| Test Drug Prank | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| The Drug Lord Version 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| The House Food and Drinks Deal | 1 | ||||

| The King’s Cup | 1 | ||||

| The Liquor Cabinet | 1 | ||||

| Toro-bar and happy hour finder | 1 | ||||

| Vinous: Wine Reviews & Ratings | 1 | ||||

| Virtual Beer | 1 | ||||

| Wateky | 1 | ||||

| Weed Farm Dealer | 1 | ||||

| Weed Tycoon | 1 | ||||

| Whack a CrackHead | 1 | ||||

| Wine Ring | 1 | ||||

| Wiz Khalifa’s Weed Farm | 1 | ||||

| World of Dope | 1 | ||||

| Total | 74 | 13 | 15 | 12 | 15 |

SEARCH TERMS (Tofighi B, 2018)

12 Step

Alcohol

Benzodiazepine

Cannabis

Cocaine

Crack Cocaine

Fentanyl

Heroin

Hydrocodone

Methamphetamine

Oxycodone

Recovery

Sober

Sobriety

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: S. Ghassemlou, C. Marini, C. Chemi, Y. S. Ranjit, and B. Tofighi declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions: B. Tofighi, C. Chemi, S. Ghassemlou, C. Marini, and Y. S. Ranjit made substantial contributions to conception, design, and writing of the article.

Human Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: This study does not involve human participants and informed consent was therefore not required.

Welfare of Animals: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); Office of the Surgeon General (US). Vision for the future: A public health approach. In: Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moreno MA, Whitehill JM. Influence of social media on alcohol use in adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Res. 2014;36(1):91–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. research2guidance: mHealth App Developer Economics 2015: 5th annual study on mHealth app publishing based on 5,000 plus respondents Available at https://research2guidance.com/product/mhealth-developer-economics-2015/. Accessibility verified September 28, 2018.

- 4. Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2234–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lewit EM, Coate D, Grossman, M. The effects of government regulation on teenage smoking. The Journal of Law and Economic. 1981;24(3):545–569. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lobstein T, Landon J, Thornton N, Jernigan D. The commercial use of digital media to market alcohol products: a narrative review. Addiction. 2017;112(suppl 1):21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith A Record Shares of Americans Now Own Smartphones, have Home Broadband. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih MY, et al. A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):566–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. IQVIA. The Growing Value of Digital Health 2017. https://www.iqvia.com/institute/reports/the-growing-value-of-digital-health. Accessibility verified September 28, 2018.

- 11. Iacoviello BM, Steinerman JR, Klein DB, et al. Clickotine, a personalized smartphone app for smoking cessation: initial evaluation. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(4):e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Apple: App Store Review Guidelines 2018. Available at: https://developer.apple.com/app-store/review/guidelines/.

- 13. Play G: Controlled Restricted Content 2018. Available at: https://support.google.com/googlenest/answer/7084229.

- 14. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Devices and Radiological Health & Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research 2018. Washington, DC: Mobile Medical Applications: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health/mobile-medical-applications.

- 15. Tofighi B, Chemi C, Ruiz-Valcárcel J, Hein P, Hu, L. A validated assessment and critical analysis of commercial smartphone applications targeting alcohol and illicit substance use. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(4):e11831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. BinDhim NF, Freeman B, Trevena L. Pro-smoking apps for smartphones: the latest vehicle for the tobacco industry? Tob Control. 2014;23:e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramo DE, Popova L, Grana R, Zhao S, Chavez K. Cannabis mobile apps: a content analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(3):e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weaver ER, Horyniak DR, Jenkinson R, Dietze P, Lim MS. “Let’s get Wasted!” and other apps: characteristics, acceptability, and use of alcohol-related smartphone applications. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2013;1(1):e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crane D, Garnett C, Brown J, West R, Michie S. Behavior change techniques in popular alcohol reduction apps: content analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. BinDhim NF, Naicker S, Freeman B, McGeechan K, Trevena, L. Apps promoting illicit drugs—A need for tighter regulation? J Consum Health Internet. 2014;18(1):31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tofighi B, Perna M, Desai A, Grov C, Lee JD. Craigslist as a source for heroin: A report of two cases. J Subst Use. 2016;21(5):543–546. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nunez-Smith M, Wolf E, Huang HM, Chen PG, Lee L, Emanuel EJ, Gross CP. Media exposure and tobacco, illicit drugs, and alcohol use among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Subst Abuse. 2010;31(3):174–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van Hout MC, Bingham T. ‘Silk Road’, the virtual drug marketplace: A single case study of user experiences. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24(5):385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dolliver DS Evaluating drug trafficking on the Tor Network: Silk Road 2, the sequel. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(11):1113–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gruenewald PJ Regulating availability: how access to alcohol affects drinking and problems in youth and adults. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34(2):248–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Choi K The associations between exposure to tobacco coupons and predictors of smoking behaviours among US youth. Tob Control. 2016;25(2):232–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jackson KM, Janssen T, Gabrielli J. Media/marketing influences on adolescent and young adult substance abuse. Curr Addict Rep. 2018;5(2):146–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sherman LE, Payton AA, Hernandez LM, Greenfield PM, Dapretto M. The power of the like in adolescence: Effects of peer influence on neural and behavioral responses to social media. Psychol Sci. 2016;27(7):1027–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoffman EW, Pinkleton BE, Weintraub Austin E, Reyes-Velázquez W. Exploring college students’ use of general and alcohol-related social media and their associations with alcohol-related behaviors. J Am Coll Health. 2014;62(5):328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boendermaker WJ, Prins PJ, Wiers RW. Cognitive bias modification for adolescents with substance use problems–Can serious games help? J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2015;49(Pt A):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barry AE, Padon AA, Whiteman SD, et al. Alcohol advertising on social media: Examining the content of popular alcohol brands on instagram. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(14):2413–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reichert T The prevalence of sexual imagery in ads targeted to young adults. J Consum Affairs. 2003;37(1):403–412. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wakefield M, Terry-McElrath Y, Emery S, et al. Effect of televised, tobacco company-funded smoking prevention advertising on youth smoking-related beliefs, intentions, and behavior. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2154–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Snyder LB, Milici FF, Slater M, Sun H, Strizhakova Y. Effects of alcohol advertising exposure on drinking among youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(1):18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]