Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 infection is controlled by the opening of the spike protein receptor binding domain (RBD), which transitions from a glycan-shielded (down) to an exposed (up) state in order to bind the human ACE2 receptor and infect cells. While snapshots of the up and down states have been obtained by cryoEM and cryoET, details of the RBD opening transition evade experimental characterization. Here, over 200 μs of weighted ensemble (WE) simulations of the fully glycosylated spike ectodomain allow us to characterize more than 300 continuous, kinetically unbiased RBD opening pathways. Together with biolayer interferometry experiments, we reveal a gating role for the N-glycan at position N343, which facilitates RBD opening. Residues D405, R408, and D427 also participate. The atomic-level characterization of the glycosylated spike activation mechanism provided herein achieves a new high-water mark for ensemble pathway simulations and offers a foundation for understanding the fundamental mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 viral entry and infection.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is an enveloped RNA virus and the causative agent of COVID-19, a disease that has caused significant morbidity and mortality worldwide.1,2 The main infection machinery of the virus is the spike (S) protein, which sits on the outside of the virus, is the first point of contact that the virion makes with the host cell, and is a major viral antigen.3 A significant number of cryoEM structures of the spike protein have been recently reported, collectively informing on structural states of the spike protein. The vast majority of resolved structures fall into either ‘down’ or ‘up’ states, as defined by the position of the receptor binding domain (RBD), which modulates interaction with the ACE2 receptor for cell entry.4,5,6

The RBDs must transition from a down to an up state for the receptor binding motif to be accessible for ACE2 binding (Figure 1), and therefore the activation mechanism is essential for cell entry. Mothes et al.7 used single-molecule fluorescence (Förster) resonance energy transfer (smFRET) imaging to characterize spike dynamics in real-time. Their work showed that the spike dynamically visits four distinct conformational states, the population of which are modulated by the presence of the human ACE2 receptor and antibodies. However smFRET, as well as conventional structural biology techniques, are unable to inform on the atomic-level mechanisms underpinning such dynamical transitions. Recently, all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the spike protein with experimentally accurate glycosylation together with corroborating experiments indicated the extensive shielding by spike glycans, as well as a mechanical role for glycans at positions N165 and N234 in supporting the RBD in the open conformation.8 Conventional MD simulations as performed in Casalino et al.8 also revealed microsecond-timescale dynamics to better characterize the spike dynamics but were limited to sampling configurations that were similar in energy to the cryoEM structures. Several enhanced sampling MD simulations have been performed to study this pathway, however, these simulations lacked glycosylation for the spike protein9 or involve the addition of an external force10 or require a massive amount of sampling (millisecond timescale).11

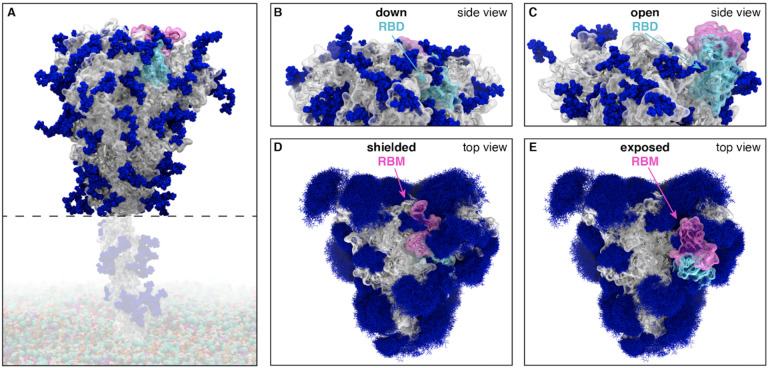

Figure 1.

(A) The SARS-CoV-2 spike head (gray) with glycans (dark blue) as simulated, with the stalk domain and membrane (not simulated here, but shown in transparent for completeness). RBD shown in cyan, receptor binding motif (RBM) in pink. Side view of the down (shielded, B) and open (exposed, C) RBD. Top view of the closed (shielded, D) and open (exposed, E) RBM. Composite image of glycans (dark blue lines) shows many overlapping snapshots of the glycans over the microsecond simulations.

In this study, we characterized the spike RBD opening pathway for the fully glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, in order to gain a detailed understanding of the activation mechanism. We used the weighted ensemble (WE) path sampling strategy12,13 (Figure S1) to enable the simulation of atomistic pathways for the spike opening process. As a path sampling strategy, WE focuses computing power on the functional transitions between stable states rather than the stable states themselves.14 This is achieved by running multiple trajectories in parallel and periodically replicating trajectories that have transitioned from previously visited to newly visited regions of configurational space15, thus minimizing the time spent waiting in the initial stable state for “lucky” transitions over the free energy barrier. Given that these transitions are much faster than the waiting times,16,17 the WE strategy can be orders of magnitude more efficient than conventional MD simulations in generating pathways for rare events such as protein folding and protein binding.18,19 This efficiency is even higher for slower processes, increasing exponentially with the effective free energy barrier.20 Not only are dynamics carried out without any biasing force or modifications to the free energy landscape, but suitable assignment of statistical weights to trajectories provides an unbiased characterization of the system’s time-dependent ensemble properties.13 The WE strategy therefore generates continuous pathways with unbiased dynamics, yielding the most direct, atomistic views for analyzing the mechanism of functional transitions, including elucidation of transient states that are too fleeting to be captured by laboratory experiments. Furthermore, while the strategy requires a progress coordinate toward the target state, the definition of this target state need not be fixed in advance when applied under equilibrium conditions,21 enabling us to refine the definition of the target open state of the spike protein based on the probability distribution of protein conformations sampled by the simulation.

Our work characterizes a series of transition pathways of the spike opening and identifies key residues, including a glycan at position N343, that participate in the opening mechanism. Our simulation findings are corroborated by biolayer interferometry experiments, which demonstrate a reduction in the ability of the spike to interact with ACE2 after mutation of these key residues.

Results and Discussion

Weighted ensemble simulations of spike opening

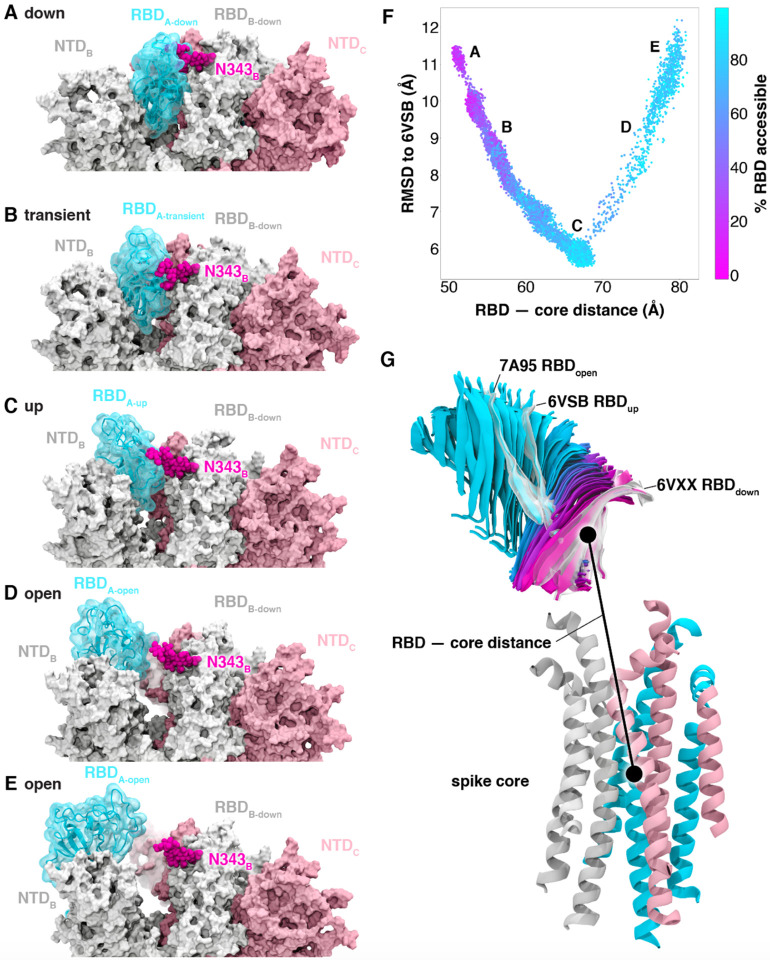

We used the WE strategy to generate continuous, atomistic pathways of the spike opening process with unbiased dynamics (Figure 2A–E, Movie S1); these pathways were hundreds of ns long, excluding the waiting times in the initial “down” state. The protein model was based on the head region (residues 16 to 1140) of the glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 spike from Casalino et al.8 (Figure 1), which in turn was built on the cryoEM structure of the three-RBD-down spike (PDB ID: 6VXX5). The entire simulation system, including explicit water and salt ions, reaches almost half a million atoms. We focused sampling along a two-dimensional progress coordinate to track RBD opening: the difference in the center of mass of the spike core to the RBD and the root mean squared deviation (RMSD) of the RBD (Figure 2F–G). On the SDSC Comet and TACC Longhorn supercomputers, 100 GPUs ran the WE simulations in parallel for over a month, generating over 200 μs of glycosylated spike trajectories and more than 200 TB of trajectory data. We simulated a total of 310 independent pathways, including 204 pathways from the RBD “down” conformation (PDB ID: 6VXX5) to the RBD “up” conformation (PDB ID: 6VSB4) and 106 pathways from the RBD “down” to RBD “open” state in which the RBD twists open beyond the cryoEM structure (PDB ID: 6VSB4). Remarkably, the open state that we sampled includes conformations that align closely with the ACE2-bound spike cryoEM structure (PDB ID: 7A956) even though this structure was not a target state of our progress coordinate (Figure 2F–G, Movie S1, Figures S2–3). This result underscores the value of using (i) equilibrium WE simulations that do not require a fixed definition of the target state and (ii) a two-dimensional progress coordinate that allows the simulations to sample unexpected conformational space along multiple degrees of freedom. The ACE2-bound spike conformation has also been sampled by the Folding@home distributed computing project,11 and RBD rotation has been detected in cryoEM experiments.6

Figure 2.

Atomically detailed pathways of spike opening. (A-E) Snapshot configurations along the opening pathway with chain A shown in cyan, chain B in gray, and chain C in pink and the glycan at position N343 is shown in magenta. (F) Scatter plot of data from the 310 continuous pathways with the RMSD of RBD to the 6VSB “up” state plotted against RBD — core distance. Data points are colored based on % RBD solvent accessible surface area compared to the RBD “down” state 6VXX. Location of snapshots shown in A-E are labeled. (G) Primary regions of spike defined for tracking progress of opening transition. The spike core is composed of three central helices per trimer, colored according to chain as in (A-E). The RBD contains a structured pair of antiparallel beta sheets and an overlay of snapshots from a continuous WE simulation are shown colored along a spectrum resembling the palette in (F). Overlayed cryoEM structures are highlighted and labeled including the initial RBD “down” state, 6VXX, the target RBD “up” state and the ACE2 bound “open” state, 7A95.

The N343 glycan gates RBD opening

In the down state, the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 spike is shielded by glycans at positions N165, N234, and N343.22 Beyond shielding, a structural role for glycans at positions N165 and N234 has been recently reported, stabilizing the RBD in the up conformation.8

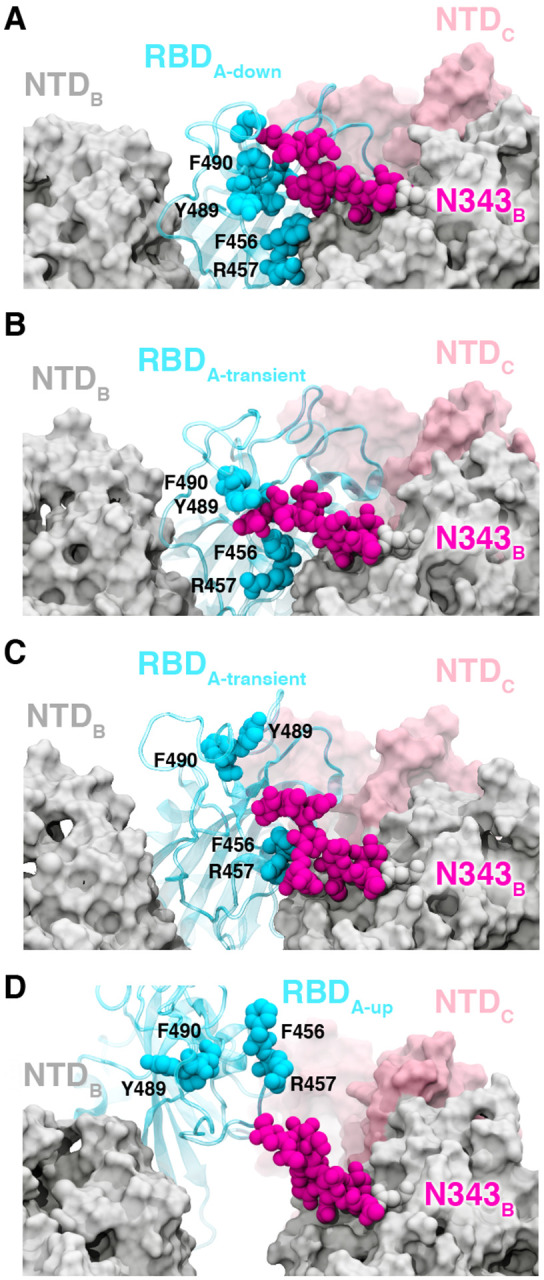

Our WE simulations reveal an even more specific, critical role of a glycan in the opening mechanism of the spike: the N343 glycan acts as a “glycan gate” pushing up the RBD by intercalating between residues F490, Y489, F456, and R457 of the ACE2 binding motif in a “hand-jive” motion (Figure 2A–E, Figure 3, Movie S2). This gating mechanism was initially visualized in several successful pathways of spike opening and then confirmed through analysis of all 310 successful pathways in which the N343 glycan was found to form contacts (within 3.5 Å) with each of the aforementioned residues in every successful pathway (Figure S4). The same mechanistic behavior of the N343 glycan was observed in two fully independent WE simulations, suggesting the result is robust despite potentially incomplete sampling that can challenge WE and other enhanced sampling simulation methods.15

Figure 3.

Glycan gating by N343. (A-D) Snapshot configurations along the opening pathway with chain A shown in cyan, chain B in gray, chain C in pink, and the glycan at position N343 is shown in magenta. (A) RBD A in the down conformation is shielded by the glycan at position N343 of the adjacent RBD B. (B-D) The N343 glycan intercalates between and underneath the residues F490, Y489, F456, F457 to push the RBD up and open (D).

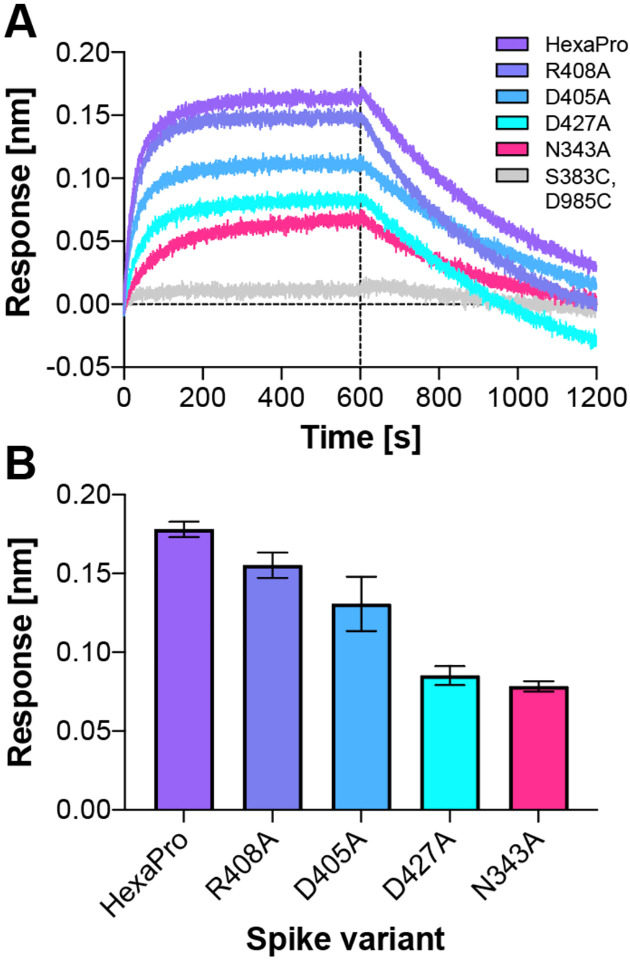

To test the role of the N343 glycan as a key gating residue, we performed biolayer interferometry (BLI) experiments. BLI experiments assess the binding level of the spike receptor binding motif (RBM, residues 438 to 508) to ACE2, acting as a proxy for the relative proportion of RBDs in the up position for each spike variant. No residues directly involved in the binding were mutated (i.e., at the RBM-ACE2 interface), to ensure controlled detection of the impact of RBD opening in response to mutations. Although previous results have shown reduced binding levels for N165A and N234A variants in the SARS-CoV-2 S-2P protein,8 the N343A variant displayed an even greater decrease in ACE2 binding, reducing spike binding level by ~56 % (Figure 4, Table S1). As a negative control, the S383C/D985C variant,23 which is expected to be locked by disulfides into the three-RBD-down conformation, showed no association with the ACE2 receptor. These results support the hypothesis that the RBD up conformation is significantly affected by glycosylation at position N343.

Figure 4.

ACE2 binding is reduced by mutation of N343 glycosylation site and key salt bridge residues. (A) Biolayer interferometry sensorgrams of HexaPro spike variants binding to ACE2. For clarity, only the traces from the first replicate are shown. (B) Graph of binding response for BLI data collected in triplicate with error bars representing the standard deviation from the mean.

Atomic details of the opening mechanism

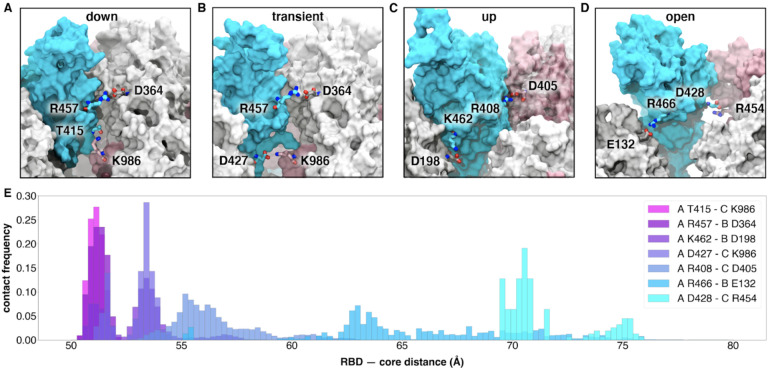

The RBD down state features a hydrogen bond between T415 of the RBD (chain A) and K986 of chain C, a salt bridge between R457 of RBDA and D364 of RBDB, and a salt bridge between K462 of RBDA and D198 of NTDC (Figure 5A–C,E Figure S5). The hydrogen bond T415A - K986C spends an average of 12% of the successful pathways to the up state before K986C makes a short lived (2% average duration to up state) salt bridge with RBDA D427. (Figure 5B,E Figure S3) Next, K986C forms salt bridges with E990C and E748C as the RBDA continues to open. These contacts are formed in all 310 successful pathways (Figure S5). Mutation of K986 to proline has been used to stabilize the pre-fusion spike,24,25 including in vaccine development,26 and these simulations provide molecular context to an additional role of this residue in RBD opening.

Figure 5.

Salt bridges and hydrogen bonds along the opening pathway. (A-D) salt bridge or hydrogen bond contacts made between RBD A, shown in blue, with RBD B, shown in gray, or RBD C shown in pink within the down, transient, up, and open conformations, respectively. (E) Histogram showing the frequency at which residues from (A-D) are within 3.5 Å of each other relative to RBD — core distance. Frequencies are normalized to 1.

Subsequently, at an average of 16% of the way through the successful pathways to the up state, the R457A - D364B salt bridge is broken, prompting the RBDA to twist upward, away from RBDB towards RBDC and forms a salt bridge between R408 of RBDA and D405 of RBDC (Figure 5C and 5E, Figure S5). This salt bridge persists for 20% of the successful trajectories to the up state, and is also present in all 310 successful pathways.

A salt bridge between R466 of RBDA and E132 from NTDB is present in 189 out of 204 successful pathways to the up state, and all 106 pathways to the open state. This contact is most prevalent during the transition between the up and open state. Finally, the salt bridge between D428 of RBDA and R454 of RBDC is present only in all 106 pathways from the up to the open state and is the last salt bridge between the RBD and the spike in the open state before the S1 subunit begins to peel off (Figure 5D and 5E, Figure S5), at which point the last remaining contact to the RBDA is the glycan at position N165 of NTBB.

Additional BLI experiments of the key identified spike residues R408A, D405A, and D427A corroborate the pathways observed in our simulations. Each of these reduces the binding interactions of the spike with ACE2 by ~13%, ~27%, and ~52%, respectively (Figure 4, Table S1). We also note that identified residues D198, N343, D364, D405, R408, T415, D427, D428, R454, R457, R466, E748, K986 and E990 are conserved between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spikes, supporting their significance in coordinating the primary spike function of RBD opening. The emerging mutant SARS-CoV-2 strains B.1: D614G; B.1.1.7: H69-V70 deletion, Y144-Y145 deletions, N501Y, A570D, D614G, P681H, T716I, S982A, D1118H; B.1.351: L18F, D80A, D215G, R246I, K417N, E484K, N501Y, D614G, A701V; P1: L18F, T20N, P26S, D138Y, R190S, K417T, E484K, N501Y ,D614G, H655Y, T1027I and CAL.20C: L452R, D614G27 do not contain mutants in the residues we identified here to facilitate RBD opening. Analysis of neighboring residues and glycans to those mutated in the emerging strains along the opening pathway is detailed in Table S2, and distances between each residue and glycan to RBDA is summarized in Movie S3.

Conclusions

We report extensive weighted ensemble molecular dynamics simulations of the glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 spike head characterizing the transition from the down to up conformation of the RBD. Over 200 microseconds of simulation provide more than 300 independent RBD opening transition pathways. Analysis of these pathways from independent WE simulations indicates a clear gating role for the glycan at N343, which lifts and stabilizes the RBD throughout the opening transition. We also characterize an “open” state of the spike RBD, in which the N165 glycan of chain B is the last remaining contact with the RBD en route to further opening of S1. Biolayer interferometry experiments of residues identified as key in the opening transitions, including N343, D405, R408, and D427, broadly supported our computational findings. Notably, a 56% decrease in ACE2 binding of the N343A mutant, compared to a 40% decrease in N234A mutant, and 10% decrease in the N165A mutant reported previously8 evidenced the key role of N343 in gating and assisting the RBD opening process, highlighting the importance of sampling functional transitions to fully understand mechanistic detail. Our work indicates a critical gating role of the N343 glycan in spike opening and provides new insights to mechanisms of viral infection for this important pathogen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the efforts of the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) Longhorn team and for the compute time made available through a Director’s Discretionary Allocation (made possible by the National Science Foundation award OAC-1818253). We thank Dr. Zied Gaieb for helpful discussions around system construction. We thank Mahidhar Tatineni for help with computing on SDSC Comet, as well as a COVID19 HPC Consortium Award for compute time. We also thank Prof. Carlos Simmerling and his research group (SUNY Stony Brook), and Prof. Adrian Mulholland and his research group (University of Bristol) for helpful discussions related to the spike protein, as well as Prof. Daniel Zuckerman, Dr. Jeremy Copperman, Dr. Matthew Zwier, and Dr. Sinam Saglam for helpful methodological discussions.

Funding

T.S. is funded by NSF GRFP DGE-1650112. S.A. is funded by NIH grant R01-GM31749. This work was supported by NIH GM132826, NSF RAPID MCB-2032054, an award from the RCSA Research Corp., and a UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center 2020 SARS-COV-2 seed grant to R.E.A.; NIH grant R01-GM31749 to J.A.M.; NIH grant R01-AI127521 to J.S.M; and NIH (1R01GM115805-01) and NSF (CHE-1807301) to L.T.C.

Footnotes

Data accession

We endorse the community principles around open sharing of COVID19 simulation data.28 All simulation input files and data are available at the NSF MolSSI COVID19 Molecular Structure and Therapeutics Hub at https://covid19.molssi.org and the Amaro Lab website http://amarolab.ucsd.edu.

References

- (1).Chan J. F.-W.; Yuan S.; Kok K.-H.; To K. K.-W.; Chu H.; Yang J.; Xing F.; Liu J.; Yip C. C.-Y.; Poon R. W.-S.; Tsoi H.-W.; Lo S. K.-F.; Chan K.-H.; Poon V. K.-M.; Chan W.-M.; Ip J. D.; Cai J.-P.; Cheng V. C.-C.; Chen H.; Hui C. K.-M.; Yuen K.-Y. A Familial Cluster of Pneumonia Associated with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Indicating Person-to-Person Transmission: A Study of a Family Cluster. The Lancet 2020, 395 (10223), 514–523. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lu R.;Zhao X.; Li J.; Niu P.; Yang B.; Wu H.; Wang W.; Song H.; Huang B.; Zhu N.; Bi Y.; Ma X.; Zhan F.; Wang L.; Hu T.; Zhou H.; Hu Z.; Zhou W.; Zhao L.; Chen J.; Meng Y.; Wang J.; Lin Y.; Yuan J.; Xie Z.; Ma J.; Liu W. J.; Wang D.; Xu W.; Holmes E. C.; Gao G. F.; Wu G.; Chen W.; Shi W.; Tan W. Genomic Characterisation and Epidemiology of 2019 Novel Coronavirus: Implications for Virus Origins and Receptor Binding. Lancet 2020, 395 (10224), 565–574. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30251-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Li F. Structure, Function, and Evolution of Coronavirus Spike Proteins. Annu Rev Virol 2016, 3 (1), 237–261. 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wrapp D.; Wang N.; Corbett K. S.; Goldsmith J. A.; Hsieh C.-L.; Abiona O.; Graham B. S.; McLellan J. S. Cryo-EM Structure of the 2019-NCoV Spike in the Prefusion Conformation. Science 2020, 367 (6483), 1260–1263. 10.1126/science.abb2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Walls A. C.; Park Y.-J.; Tortorici M. A.; Wall A.; McGuire A. T.; Veesler D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181 (2), 281–292.e6. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Benton D. J.; Wrobel A. G.; Xu P.; Roustan C.; Martin S. R.; Rosenthal P. B.; Skehel J. J.; Gamblin S. J. Receptor Binding and Priming of the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 for Membrane Fusion. Nature 2020, 588 (7837), 327–330. 10.1038/s41586-020-2772-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lu M.; Uchil P. D.; Li W.; Zheng D.; Terry D. S.; Gorman J.; Shi W.; Zhang B.; Zhou T.; Ding S.; Gasser R.; Prévost J.; Beaudoin-Bussières G.; Anand S. P.; Laumaea A.; Grover J. R.; Liu L.; Ho D. D.; Mascola J. R.; Finzi A.; Kwong P. D.; Blanchard S. C.; Mothes W. Real-Time Conformational Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Spikes on Virus Particles. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28 (6), 880–891.e8. 10.1016/j.chom.2020.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Casalino L.; Gaieb Z.; Goldsmith J. A.; Hjorth C. K.; Dommer A. C.; Harbison A. M.; Fogarty C. A.; Barros E. P.; Taylor B. C.; McLellan J. S.; Fadda E.; Amaro R. E. Beyond Shielding: The Roles of Glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Gur M.; Taka E.; Yilmaz S. Z.; Kilinc C.; Aktas U.; Golcuk M. Conformational Transition of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein between Its Closed and Open States. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153 (7), 075101. 10.1063/5.0011141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Fallon L.; Belfon K.; Raguette L.; Wang Y.; Corbo C.; Stepanenko D.; Cuomo A.; Guerra J.; Budhan S.; Varghese S.; Rizzo R.; Simmerling C. Free Energy Landscapes for RBD Opening in SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein Simulations Suggest Key Interactions and a Potentially Druggable Allosteric Pocket. 2020. 10.26434/chemrxiv.13502646.v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (11).SARS-CoV-2 Simulations Go Exascale to Capture Spike Opening and Reveal Cryptic Pockets Across the Proteome | bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.27.175430v3 (accessed Jan 13, 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Huber G. A.; Kim S. Weighted-Ensemble Brownian Dynamics Simulations for Protein Association Reactions. Biophys. J. 1996, 70 (1), 97–110. 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79552-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Zhang B. W.; Jasnow D.; Zuckerman D. M. The “Weighted Ensemble” Path Sampling Method Is Statistically Exact for a Broad Class of Stochastic Processes and Binning Procedures. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132 (5), 054107. 10.1063/1.3306345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chong L. T.; Saglam A. S.; Zuckerman D. M. Path-Sampling Strategies for Simulating Rare Events in Biomolecular Systems. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2017, 43, 88–94. 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zuckerman D. M.; Chong L. T. Weighted Ensemble Simulation: Review of Methodology, Applications, and Software. Annu Rev Biophys 2017, 46, 43–57. 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070816-033834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Pratt L. R. A Statistical Method for Identifying Transition States in High Dimensional Problems. J. Chem. Phys. 1986, 85 (9), 5045–5048. 10.1063/1.451695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zuckerman D. M.; Woolf T. B. Transition Events in Butane Simulations: Similarities across Models. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 116 (6), 2586–2591. 10.1063/1.1433501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Adhikari U.; Mostofian B.; Copperman J.; Subramanian S. R.; Petersen A. A.; Zuckerman D. M. Computational Estimation of Microsecond to Second Atomistic Folding Times. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141 (16), 6519–6526. 10.1021/jacs.8b10735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Saglam A. S.; Chong L. T. Protein–Protein Binding Pathways and Calculations of Rate Constants Using Fully-Continuous, Explicit-Solvent Simulations. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10 (8), 2360–2372. 10.1039/C8SC04811H [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).DeGrave A. J.; Ha J.-H.; Loh S. N.; Chong L. T. Large Enhancement of Response Times of a Protein Conformational Switch by Computational Design. Nature Communications 2018, 9 (1), 1013. 10.1038/s41467-018-03228-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Suárez E.; Lettieri S.; Zwier M. C.; Stringer C. A.; Subramanian S. R.; Chong L. T.; Zuckerman D. M. Simultaneous Computation of Dynamical and Equilibrium Information Using a Weighted Ensemble of Trajectories. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014, 10 (7), 2658–2667. 10.1021/ct401065r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Watanabe Y.; Allen J. D.; Wrapp D.; McLellan J. S.; Crispin M. Site-Specific Glycan Analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike. Science 2020. 10.1126/science.abb9983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Henderson R.; Edwards R. J.; Mansouri K.; Janowska K.; Stalls V.; Gobeil S. M. C.; Kopp M.; Li D.; Parks R.; Hsu A. L.; Borgnia M. J.; Haynes B. F.; Acharya P. Controlling the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein Conformation. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2020, 27 (10), 925–933. 10.1038/s41594-020-0479-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Pallesen J.; Wang N.; Corbett K. S.; Wrapp D.; Kirchdoerfer R. N.; Turner H. L.; Cottrell C. A.; Becker M. M.; Wang L.; Shi W.; Kong W.-P.; Andres E. L.; Kettenbach A. N.; Denison M. R.; Chappell J. D.; Graham B. S.; Ward A. B.; McLellan J. S. Immunogenicity and Structures of a Rationally Designed Prefusion MERS-CoV Spike Antigen. PNAS 2017, 114 (35), E7348–E7357. 10.1073/pnas.1707304114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Hsieh C.-L.; Goldsmith J. A.; Schaub J. M.; DiVenere A. M.; Kuo H.-C.; Javanmardi K.; Le K. C.; Wrapp D.; Lee A. G.; Liu Y.; Chou C.-W.; Byrne P. O.; Hjorth C. K.; Johnson N. V.; Ludes-Meyers J.; Nguyen A. W.; Park J.; Wang N.; Amengor D.; Lavinder J. J.; Ippolito G. C.; Maynard J. A.; Finkelstein I. J.; McLellan J. S. Structure-Based Design of Prefusion-Stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spikes. Science 2020, 369 (6510), 1501–1505. 10.1126/science.abd0826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Cross Ryan. The Tiny Tweak behind COVID-19 Vaccines. Chemical & Engineering News. September 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Corum J.; Zimmer C. Coronavirus Variants and Mutations. The New York Times. February 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Amaro R. E.; Mulholland A. J. A Community Letter Regarding Sharing Biomolecular Simulation Data for COVID-19. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60 (6), 2653–2656. 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.