Abstract

Background

Concerning levels of burnout have been reported among orthopaedic surgeons and residents. Defined as emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, physician burnout is associated with decreased productivity, increased medical errors, and increased risk of suicidal ideation. At the center of burnout research, person-centered approaches focusing on individual characteristics and coping strategies have largely been ineffective in solving this critical issue. They have failed to capture and address important institutional and organizational factors contributing to physician burnout. Similarly, little is known about the relationship between burnout and the working environments in which orthopaedic physicians practice, and on how orthopaedic surgeons at different career stages experience and perceive factors relevant to burnout.

Questions/purposes

(1) How does burnout differ among orthopaedic attending surgeons, fellows, and residents? (2) What specific areas of work life are problematic at each of these career stages? (3) What specific areas of work life correlate most strongly with burnout at each of these career stages?

Methods

Two hundred orthopaedic surgeons (residents, fellows, and attending physicians) at a single institution were invited to complete an electronic survey. Seventy-four percent (148 of 200) of them responded; specifically, 43 of 46 residents evenly distributed among training years, 18 of 36 fellows, and 87 of 118 attending physicians. Eighty-three percent (123 of 148) were men and 17% (25 of 148) were women. Two validated questionnaires were used. The Maslach Burnout Inventory was used to assess burnout, measuring emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. The Areas of Worklife Survey was used to measure congruency between participants and their work environment in six domains: workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values. Participants were invited to openly share their experiences and suggest ways to improve burnout and specific work life domains. The main outcome measures were Maslach Burnout Inventory subdomains of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and Areas of Worklife Survey subdomains of workload, control, reward, community, fairness and values. We compared outcome measures of burnout and work life between groups. Simple linear regression models were used to report correlations between subscales. Stratified analyses were used to identify which group demonstrated higher correlations. All open comments were analyzed and coded to fully understand which areas of work life were problematic and how they were perceived in our population.

Results

Nine percent (7 of 80) of attending surgeons, 6% (1 of 16) of fellows, and 34% (14 of 41) of residents reported high levels of depersonalization on the Maslach Burnout Inventory (p < 0.001). Mean depersonalization scores were higher (worse) in residents followed by attending surgeons, then fellows (10 ± 6, 5 ± 5, 4 ± 4 respectively; p < 0.001). Sixteen percent (13 of 80) of attending surgeons, 31% (5 of 16) of fellows, and 34% (14 of 41) of residents reported high levels of emotional exhaustion (p = 0.07). Mean emotional exhaustion scores were highest (worse) in residents followed by attending surgeons then fellows (21 ± 12, 17 ± 10, 16 ± 14 respectively; p = 0.11). Workload was the most problematic work life area across all stages of orthopaedic career. Scores in the Areas of Worklife Survey were the lowest (worse) in the workload domain for all subgroups: residents (2.6 ± 0.4), fellows (3.0 ± 0.6), and attending surgeons (2.8 ± 0.7); p = 0.08. Five problematic work life categories were found through open comment analysis: workload, resources, interactions, environment, and self-care. Workload was similarly the most concerning to participants. Specific workload issues identified included administrative load (limited job control, excessive tasks and expectations), technology (electronic medical platform, email overload), workflow (operating room time, patient load distribution), and conflicts between personal, clinical, and academic roles. Overall, worsening emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were most strongly associated with increasing workload (r = - 0.50; p < 0.001; and r = - 0.32; p < 0.001, respectively) and decreasing job control (r = - 0.50; p < 0.001, and r = - 0.41; p < 0.001, respectively). Specifically, in residents, worsening emotional exhaustion and depersonalization most strongly correlated with increasing workload (r = - 0.65; p < 0.001; and r = - 0.53; p < 0.001, respectively) and decreasing job control (r = - 0.49; p = 0.001; and r = - 0.51; p = 0.001, respectively). In attending surgeons, worsening emotional exhaustion was most strongly correlated with increasing workload (r = - 0.50; p < 0.001), and decreasing job control (r = - 0.44; p < 0.001). Among attending surgeons, worsening depersonalization was only correlated with increasing workload (r = - 0.23; p = 0.04). Among orthopaedic fellows, worsening emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were most strongly correlated with decreasing sense of fairness (r = - 0.76; p = 0.001; and r = - 0.87; p < 0.001, respectively), and poorer sense of community (r = - 0.72; p = 0.002; and r = - 0.65; p = 0.01, respectively).

Conclusions

We found higher levels of burnout among orthopaedic residents compared to attending surgeons and fellows. We detected strong distinct correlations between emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and areas of work life across stages of orthopaedic career. Burnout was most strongly associated with workload and job control in orthopaedic residents and attending surgeons and with fairness and community in orthopaedic fellows.

Clinical Relevance

Institutions wishing to better understand burnout may use this approach to identify specific work life drivers of burnout, and determine possible interventions targeted to orthopaedic surgeons at each stage of career. Based on our institutional experience, leadership should investigate strategies to decrease workload by increasing administrative support and improving workflow; improve sense of autonomy by consulting physicians in decision-making; and seek to improve the sense of control in residents and sense of community in fellows.

Introduction

Burnout is a multidimensional construct defined by overwhelming emotional exhaustion (wearing out and loss of energy), depersonalization (cynicism and detachment), and reduced sense of personal accomplishment (sense of professional inefficacy) [17, 20, 28]. It is associated with diminished professional effort and productivity; increased medical errors, poor patient outcomes, and hostility towards patients; and increased risk of depression, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse [3, 15, 31]. Burnout is labeled an epidemic in the United Sates and is extensively researched and broadly documented among medical students, residents, and attending physicians [4, 9, 15, 19, 36]. Studies described burnout in 40% of 7905 surgeons [29] and 69% of 566 surgical residents [15]. Orthopaedic surgeons, specifically, have reported the highest levels of burnout among all surgical specialties [30]. Academically, high levels of burnout were found both in orthopaedic faculty (28%) and residents (56%) [27]. Given the magnitude of this issue, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education stipulates that learning and working environments in residency education must emphasize their commitment to the well-being of students, residents, faculty, and all members of the healthcare team [1].

Most burnout studies have focused on finding individual-centered causes and solutions (for example, mindfulness or resilience) rather than organizational ones [20, 31, 36]. Studies suggest that organizational factors may play a more important role in burnout than individual circumstances do [20, 31, 32]. Focusing on coping strategies alone may limit interventions to addressing symptoms rather than causes of poor work environments [4]. Thus, while important, individual-centered approaches may not address institutional factors contributing to physician burnout and are less likely to result in meaningful, sustainable progress [31]. “The Person Within the Context” is an expansion of theoretical frameworks of burnout inspired by the person-job fit model [20]. It incorporates both individual and situational factors, postulating that burnout arises from chronic mismatches between people and their workplace in some or all of six work life domains: workload (the amount of work to do in a given time), control (opportunity to make decisions at work), reward (financial or social recognition for one’s contributions), community (quality of social interactions at work), fairness (of decisions at work), and values (shared between an organization and its members) [20]. Scarcely studied in the evidence, we used this framework to analyze the relationship between burnout and work life in orthopaedic surgery. Furthermore, we explored the spectrum of experiences among residents, fellows and attending surgeons, a comparison seldomly conducted in research studies.

Specifically, we asked: (1) How does burnout differ among orthopaedic attending surgeons, fellows, and residents? (2) What specific areas of work life are problematic at each of these career stages? (3) What specific areas of work life correlate most strongly with burnout at each of these career stages?

Materials and Methods

Participants

We performed a single-centered cross-sectional mixed-methods (quantitative and qualitative) study of burnout and work life domains in orthopaedic surgery residents, fellows, and attending physicians.

The study was performed at the Hospital for Special Surgery, an orthopaedic subspecialty hospital located in New York City, NY, USA. Although physician burnout is a nationwide problem, work environments and organizational practices vary among institutions. Given that several large studies have already identified the problem of burnout in orthopaedic surgery, the purpose of this study was distinct. We aimed to better elucidate the specific work-environment factors contributing to burnout and how they might be addressed. As such, a single-center study in an institution with nearly 200 orthopaedic surgeons, while limited in its generalizability, provided an ideal environment for this approach.

We used both quantitative and qualitative research methods in this study. Although the prevailing paradigm for orthopaedics research is quantitative [5], we believe qualitative methodologies played a crucial role in this study. Like quantitative research, qualitative studies aim to answer specific questions and build upon or reject hypotheses or theories [18]. But unlike quantitative research, they handle nonnumerical information and their interpretation, which are both completely intertwined with human senses and subjectivity [18]. Therefore, qualitative research overcomes the limits of quantitative work by revealing deeper meaning, contexts, complex relationships, and thinking patterns, which ultimately affect decision-making processes [5]. We believe that listening to surgeons’ lived experiences using these underutilized qualitative methods was optimal to fully understand and evaluate the relationship between physician burnout and work life. We used valid, reliable, generalizable, and systematic quantitative and qualitative methods to address burnout and answer our research questions, an approach we trust can be replicated and implemented at other orthopaedic institutions and residency programs.

In line with the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) [13], after review and approval of this study by our institutional review board, surveys were emailed to all eligible participants. A cover letter requesting participation and explaining the purpose, methods, and privacy measures of the questionnaires was included. Residents and fellows who were identified through our academic training office were asked to participate. Surgeons affiliated with our hospital were identified through our medical staff services office. Resigning physicians, those with privileges at our hospital but who were in private practice, and anyone who was more than 6 continuous months away from patient care were excluded. All remaining physicians were invited to participate. This closed survey was administered through a secure research administration portal (REDCap), only accessible to the lead researcher. Links were unique to each participant, and automatically disabled after survey completion. No individual data were collected, anonymity was guaranteed, participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained. The survey was open for 9 weeks. Non-responders received up to three reminder messages.

Queried demographic information included self-reported age, race/ethnicity, gender, marital status, year of training (residents) or number of years of practice (attending physicians), weekly work hours, and participation in clinical research.

Demographics

Seventy-four percent (148 of 200) of eligible respondents completed the survey. Specifically, 93% (43 of 46) of residents, 50% (18 of 36) of fellows, and 74% (87 of 118) of attending surgeons responded. Eighty-three percent (123 of 148) were men, and 17% (25 of 148) were women (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of orthopaedic surgery residents, fellows, and attending surgeons

| Characteristics | Resident (n = 43) | Fellow (n = 18) | Attending (n = 87) | Total (n = 148) | p value |

| Gender | |||||

| Women, % (n) | 26 (11) | 22 (4) | 11 (10) | 17 (25) | 0.11 |

| Age, % (n) | |||||

| 25-34 | 100 (43) | 89 (16) | 4 (4) | 43 (63) | < 0.001 |

| 35-49 | 0 (0) | 11 (2) | 38 (33) | 23 (35) | |

| 50-64 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 43 (37) | 25 (37) | |

| ≥ 65 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 15 (13) | 9 (13) | |

| Race/ethnicity, % (n) | |||||

| Asian | 16 (7) | 22 (4) | 14 (12) | 16 (23) | 0.66 |

| Black or African American | 2 (1) | 11 (2) | 3 (3) | 4 (6) | 0.26 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (4) | 6 (1) | 3 (3) | 5 (8) | 0.38 |

| White | 81 (35) | 61 (11) | 83 (72) | 80 (118) | 0.11 |

| Other | 2 (1) | 11 (2) | 3 (3) | 4 (6) | 0.26 |

| Marital status, % (n) | |||||

| Divorced | 2 (1) | 6 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (4) | < 0.001 |

| Married | 49 (21) | 50 (9) | 94 (81) | 75 (111) | |

| Never married/in a relationship | 28 (12) | 11 (2) | 1 (1) | 10 (15) | |

| Never married/single | 21 (9) | 33 (6) | 2 (2) | 12 (17) | |

| Years in practice, % (n) | |||||

| ≤ 4 | 11 (10) | ||||

| 5-14 | 26 (22) | ||||

| 15-24 | 34 (29) | ||||

| ≥ 25 | 29 (25) | ||||

| Weekly work hours, % (n) | |||||

| ≤ 45 | 7 (3) | 0 (0) | 7 (6) | 6 (9) | 0.26 |

| 46 - 64 | 23 (10) | 61 (11) | 50 (43) | 44 (64) | |

| 65 - 84 | 58 (25) | 39 (7) | 40 (34) | 45 (66) | |

| ≥ 85 | 12 (5) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 6 (8) | |

| Involved in clinical research | |||||

| No, % (n) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 3 (5) | 0.55 |

All demographic data, including race/ethnicity were determined by participant self-report. Participants were able to report one or more race/ethnicity category.

Survey Instruments

We used two validated questionnaires. The 22-item Maslach Burnout Inventory, which is considered the gold standard for burnout evaluation in medical studies [34, 35] was used to measure emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment (see Appendix; Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A409) [21]. It included prompts such as “I feel burned out from my work” and “I’ve become more callous toward people since I took this job”. Items were scored on a 7-point frequency scale, with answers ranging from “never” (0) to “always” (6). Scores were calculated for each dimension as delineated by the Maslach Burnout Inventory manual [21]. Higher scores on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization indicated higher degrees of burnout. “High-severity” was defined by total score ≥ 27 of 54 on emotional exhaustion, and ≥ 13 of 30 on depersonalization [24]. Consistent with the methods of prior studies, the statistical analysis prioritized the more-reliable burnout measures: emotional exhaustion and depersonalization [11, 20, 31].

The 28-item Areas of Worklife Survey was used to measure congruency between participants and their work environment (job-person fit) in six domains: workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values (see Appendix; Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A409) [16]. Each scale included positively worded items such as “I have control over how I do my work” (control) and negatively worded items such as “I do not have time to do the work that must be done” (workload). The degree of agreement with these statements was indicated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Scoring was reversed for negatively phrased questions, and scores calculated for each domain as delineated by the Areas of Worklife Survey manual [16]. For each domain, lower scores (< 3 of 5) indicated unfavorable work settings, that is, incongruence between participants and their workplace (job-person mismatch). Higher scores (> 3 out 5) indicated favorable work settings, namely, more congruence between participants and their workplace (job-person fit).

To understand the most problematic areas of work life, participants were asked to elaborate on their burnout experience, and suggest improvements for each Areas of Worklife Survey domain. Fifty-seven participants (nine residents, four fellows, and 44 attending physicians) answered the open-ended questions. All open comments were analyzed using a grounded-theory approach [5] and a two-part coding process. After initially reading the comments, we manually and deductively coded each comment to identify and label key elements into items, themes, and categories. Next, comments were coded again, inductively, based on previously found codes and themes from the Maslach Burnout Inventory and Areas of Worklife Survey. All codes were finally regrouped into main categories, themes, and sub-themes for meaningful data organization.

Statistical Analysis

Fully completed demographics, Maslach Burnout Inventory, and Areas of Worklife Survey were included in the analysis. Continuous variables are reported as means and SDs; discrete variables are reported as frequencies and percentages. One-way ANOVA was used to compare continuous variables, Maslach Burnout Inventory measures, and Areas of Worklife Survey measures among medical roles. Chi-square tests were used to analyze categorical variables. Simple linear regression models were used to analyze the primary outcome of this study and report the correlation between Maslach Burnout Inventory and Areas of Worklife Survey subdomains. Stratified analyses helped identify which medical group demonstrated higher correlations. Radar graphs were created to visualize these correlations. Multivariable linear regression modeling was used to adjust for confounders in the relationship between Maslach Burnout Inventory and Areas of Worklife Survey subdomains and identify potential contributing risk-factors. Age, gender, marital status, weekly work-hours, involvement in clinical research, and medical roles were all included in the analysis. On interpretation of correlations, negative correlations between Maslach Burnout Inventory and Areas of Worklife subscales indicate that higher degrees of burnout (higher scores on emotional exhaustion or depersonalization) correlate with poor working environments (lower scores on work life domains). Conversely, positive correlations between subscales indicate that higher degrees of burnout (higher scores on emotional exhaustion or depersonalization) correlate with better working environments (higher scores on work life domains). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were performed with SPSS, version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Burnout Prevalence among Orthopaedic Attending Surgeons, Fellows, and Residents

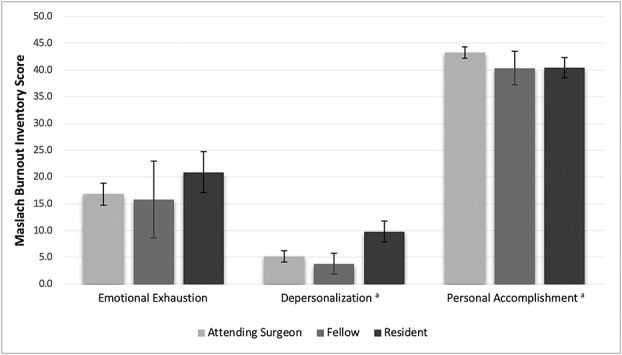

Residents reported higher levels of burnout than attending surgeons or fellows. Nine percent (7 of 80) of attending surgeons, 6% (1 of 16) of fellows, and 34% (14 of 41) of residents scored in the “high” range for depersonalization (p = 0.001). Mean scores in depersonalization were higher (worse) in residents, compared with attending surgeons, and fellows (10 ± 6, 5 ± 5, 4 ± 4 respectively; p < 0.001). Sixteen percent (13 of 80) of attending surgeons, 31% (5 of 16) of fellows, and 34% (14 of 41) of residents scored in the “high” range for emotional exhaustion (p = 0.07). With the numbers available, we found no differences in mean emotional exhaustion scores among residents, attending surgeons, and fellows (21 ± 12, 17 ± 10, 16 ± 14 respectively; p = 0.11) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

This graph shows the differences in Maslach Burnout Inventory domain scores among the medical roles. ap ≤ 0.05 indicates burnout domains with differences among medical roles.

Problematic Areas of Work Life among Orthopaedic Attending Surgeons, Fellows, and Residents

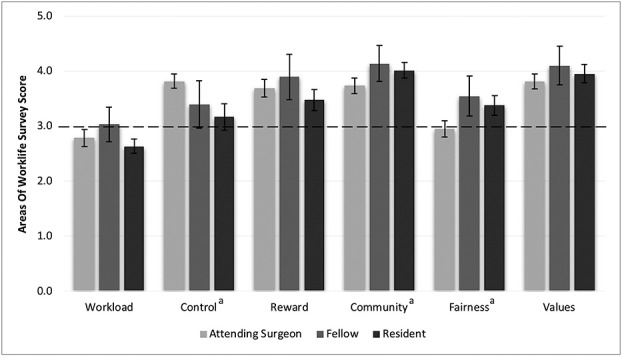

Workload was the most problematic area across all stages of orthopaedic career. For residents, scores on the Areas of Worklife Survey were lowest, suggesting unfavorable work settings, incongruence, and job-person mismatch in the workload domain (2.6 ± 0.4) followed by control (3.2 ± 0.8). Similarly, for fellows, scores were lowest in the workload domain (3.0 ± 0.6) followed by control (3.4 ± 0.8). For attendings, scores were lowest in the workload domain (2.8 ± 0.7) followed by fairness (3.0 ± 0.7). Mean scores were different between residents, fellows and attending surgeons in the control, community and fairness work life domains; but not in the workload, rewards, and values domain (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

This graph shows the differences in Areas of Worklife Survey domain scores among the medical roles. ap ≤ 0.05 indicates categories with differences among medical roles.

Qualitative analysis of open text comments identified five problematic areas of work life: workload, resources, interactions, environment, and self-care (Table 2). Workload was the most concerning area (34 participants), further confirming the results from the Areas of Worklife Survey. Various themes emerged regarding issues with workload, which were classified into administrative, technology, conflicts, and procedures. In terms of administrative workload, participants’ concerns included limited control, time management, excessive paperwork and deskwork responsibilities. Limited control over their intense workload in addition to time constrains left them feeling that important personal and work-related experiences were not prioritized. Participants also reported conflicts between their family, academic, and clinical roles, which pull them simultaneously in opposing directions. The main issues identified regarding technology included efficiency of the current electronic medical platform and email overload. Interactions, both with leadership and between colleagues, emerged as the second-most problematic area (26 participants), followed by a lack of resources (human, financial, and material) (21 participants). Few outliers (nine participants), with responses that did not fit within mainstream categories, were noted.

Table 2.

Participant open-text comment analysis

| Categories | Themes | Subthemes | Items – details |

| Workload (34 participants) | Administrative |

• Control • Time management • Paperwork/deskwork • Responsibility |

− Intense workload with limited control − Less tasks to do/take on, less documentation/meetings, time consuming − Lower responsibility − More hours/time per day − Prioritize important experiences |

|

• Self-decision, self-imposed |

− Personal choice, decision − Personality-driven |

||

| Technology/ electronic |

• Electronic medical platform • Email overload |

− Issues with platform (efficacy, efficiency, user-friendliness) − Unnecessary email overload |

|

| Conflicts |

• Work-life balance • Role-conflicts |

− Interference with home life (after-hours calls, outside work) − Family vs clinic vs academic roles |

|

| Procedure |

• Workflow • Structure |

− Pressure to do more, to say yes − Fewer patients per day; fair/equal distribution of certain patients − More operating room block time and autonomy needed − Change academic structure − Better clinic streamline process |

|

| Resources (21 participants) | Human |

• Support staff (clinical, administrative, research) • Career counseling |

− More qualified staff (nurses, assistants, scribes, help at various levels) with improved responsiveness, to delegate more − Transparency in hiring process − Sustainable practice building |

| Finance |

• Institution financial model • Incentives • Economic pressure • Finances and power |

− Unethical billing practices − Finances: inequality and power balance − Improve current financial models − More financial incentives − Maintain core values despite pressure |

|

| Material |

• Resource distribution • Operating room (OR) |

− Uneven, unfair distribution (squeaky wheels) − More operating room block time |

|

| Interactions (26 participants) | With leadership/ management |

• Issues with current leaders • Transparency • Confidentiality • Shared values • Seniority • Feedback • Consultation and decision-making |

− Voices not heard by leadership; insufficient trust between both sides; misaligned goals − Stop preferential treatment, need to foster fairness − Force to choose = negative impact − Isolation from main politics; need for open discussion, more inclusion in decision-making − Better leadership awareness of staff performance − More feedback to trainees |

| Between colleagues |

• Emotional impact • Tension, stress • Contact, rapport • Transparency • Age difference/gap |

− Complex peer relationships; need for open discussion − Negative or insufficient interactions (staff, physician assistant); need for more interactions − More private/safe/confidential physician space − Less isolation among colleagues |

|

| Environment (10 participants) | Community |

• Sense of community (lack of) • Respect |

− Intense workload interference − Group-centered (team) over self-centered − Increased and better planned social interactions − Joint efforts; shared responsibility and burden − Shared mindset and values, equal respect for all |

| Acknowledgment |

• Work recognition (various forms) |

− Share work accomplishments with other − Rewarded with additional block time or other − Merit-based |

|

| Self-care (three participants) | Physical |

• Exercise • Sleeping • Wellness |

− No activities planned |

| Non-physical |

• Emotions • Wellness |

− Tension, stress − No activities planned |

|

| Outliers (nine participants) | Workload |

• Satisfaction |

− Appropriate or manageable workload − Completed workload − Adequate support found |

| Control |

• Satisfaction |

− Has job control − No change needed in job control status |

|

| Reward |

• Satisfaction |

− Recognition for efforts |

|

| Community |

• Respect, collegiality • Fairness • Values |

− Found among colleagues − Satisfaction with work environment − Support found − Shared values with institution |

Areas of Work Life Associated with Burnout in Orthopaedic Attending Surgeons, Fellows, and Residents

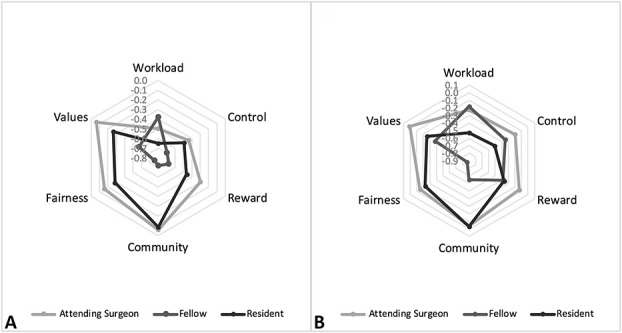

Excessive workload and limited job control were most strongly correlated with burnout in our overall population. Worsening emotional exhaustion was most strongly associated with increasing workload and decreasing job control (r = - 0.50; p < 0.001; and r = - 0.50; p < 0.001, respectively) (Table 3). Similarly, worsening depersonalization was most strongly associated with increasing workload and decreasing job control (r = - 032; p < 0.001; and r = - 0.41; p < 0.001, respectively). Correlations between burnout and areas of work life varied in strength among attendings, fellows, and residents (Fig. 3A-B). In residents, worsening emotional exhaustion most strongly correlated with increasing workload (r = - 0.65; p < 0.001), and decreasing job control (r = - 0.49; p = 0.001). In attending surgeons, worsening emotional exhaustion most strongly correlated with increasing workload (r = - 0.50; p < 0.001), and decreasing job control (r = - 0.44; p < 0.001). In fellows, however, worsening emotional exhaustion most strongly correlated with decreasing sense of fairness (r = - 0.76; p = 0.001) and poorer sense of community at work (r = - 0.72; p = 0.002), respectively. Worsening depersonalization in residents most strongly correlated with increasing workload (r = - 0.53; p < 0.001) and decreasing job control (r = - 0.51; p = 0.001). Worsening depersonalization in attending surgeons was only weakly correlated to workload (r = - 0.23; p = 0.04). Meanwhile, worsening depersonalization in fellows was only correlated to decreasing sense of fairness (r = - 0.87; p < 0.001) and poorer sense of community (r = - 0.65; p = 0.01). Our multivariable analysis revealed no correlation between depersonalization or emotional exhaustion, and self-reported age, marital status, work-hours, or involvement in clinical research. Correlations based on gender were inconclusive.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation between burnout and areas of work life in the overall orthopaedic sample population

| Workload | Control | Reward | Community | Fairness | Values | |

| Emotional exhaustion | - 0.50a | - 0.50a | - 0.42a | - 0.14 | - 0.24a | - 0.19a |

| Depersonalization | - 0.32a | - 0.41a | - 0.27a | - 0.03 | - 0.14 | - 0.09 |

p < 0.001 to 0.03.

Fig. 3 (A-B).

These radar graphs demonstrate the spread of the correlation of each Areas of Worklife Survey score with (A) emotional exhaustion, and (B) depersonalization. Points that are closer to the center demonstrate a stronger relationship between the Maslach Burnout Inventory domains (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization) and Areas of Worklife Survey domains (workload, control, reward, community, fairness, values).

Discussion

Orthopaedic trainees and practicing surgeons have reported alarming levels of burnout [27, 30], associated poor personal and professional outcomes [3, 15, 31]. Physician burnout remains a critical issue despite decades of research and efforts to understand and solve the problem. Years of studying individual characteristics and developing coping strategies have not been tremendously effective; partially addressing the issue and directing interventions to symptoms rather than causes of poor work environments [4]. In this study, we focused on the relationship between surgeons and the work-environment to identify modifiable workplace factors that may be targeted to decrease burnout and improve physician well-being. We found that residents had worse scores for the depersonalization domain of burnout and that excessive workload and limited job control were most strongly associated with physician burnout overall. Through qualitative analysis, we found workload to be the most concerning workplace factor, with specific issues regarding administration, technology, workflow, and conflicts.

Limitations

As a survey-based study of the complex topic of physician burnout, this study has several limitations that must be considered when interpreting our results. This study is restricted by its cross-sectional and single-institution design. As such, it does not capture how work-life variables change over time, and causal relationships cannot be inferred. Although our findings may not be generalizable to all orthopaedic practices, several factors common to orthopaedic surgery are likely generalizable, including perceived excessive workload, workflow inefficiencies, and challenges of balancing multiple roles and expectations of an academic practice. This single-center design allowed us to more deeply investigate how work-life factors are associated with burnout. Given our sample population, our results may be most applicable to orthopaedic residency and fellowship academic programs located in major metropolitan areas. In settings in which our findings may not be generalizable, our approach and methods may be applied to evaluate burnout together with the work environment to determine potential workplace interventions.

This study is also limited by potential non-responder bias, which could have led to decreased responses from those experiencing high or low levels of burnout. Although respondents and non-respondents may differ, this is mitigated by the 74% response rate to the quantitative portion of our survey including the Maslach Burnout Inventory and Areas of Worklife Survey. A smaller percentage (38%, 57 of 148) of survey respondents opted to share their work life and burnout perspectives through open comments; however, sample sizes in qualitative studies are usually lower than in quantitative work [5]. We believe that our qualitative report was not impaired by this smaller sample size, as it provided a second layer of analysis to the quantitative result. There were no differences identified between survey respondents who did and did not include open text comments.

Studying the association between gender, ethnicity, and burnout in orthopaedic surgery is challenging given the relatively small percentage of women and limited racial/ethnic diversity in the specialty [6, 7]. We believe our study population to be a fair representation of gender distribution in overall orthopaedic surgeon (see Table 1; Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A410) and resident (see Table 2; Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A411) populations [2, 6]. Similarly, race/ethnicity distribution in our cohort is comparable to that in orthopaedic surgeons (see Table 3; Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A412) and residents overall (see Table 4; Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A413) [6, 8]. That said, the lack of power in our study prevented drawing meaningful conclusions based on gender and race/ethnicity. We also assumed that survey questions were truthfully answered. Burnout, and mental illness in general, are stigmatized in residency and surgical professions, potentially causing inaccurate reporting for fear of repercussions including those pertaining to medical licensure [12]. Our data are, however, congruent with those of other studies [9, 26, 27], including but not limited to those in orthopaedic surgery [16, 22, 23, 33], suggesting that our methods are valid.

Burnout Among Orthopaedic Attending Surgeons, Fellows, and Residents

Our results revealed that attending surgeons at our institution had lower levels of burnout than full-time orthopaedic faculty evaluated by Sargent et al. [27]. The prevalence of “high” emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in academic surgeons varies widely among studies, ranging from 23% to 56% and 13% to 38.4%, respectively, based on a systematic review by Pulcrano et al. [23]. Our incidence was lower, with 16% of attending surgeons scoring in the high range for emotional exhaustion, and 9% scoring in the high range for depersonalization. The lack of standard thresholds, with very high to very low Maslach Burnout Inventory cutoff values used in different studies, make it challenging to compare results among institutions, and can partially explain these wide burnout ranges [24]. Because we used very commonly used cutoff values [24] to define burnout, compared with normative scores reported in the Maslach Burnout Inventory [21], and compared results subscale to subscale, we feel confident and encouraged by the numbers at our institution. The uniqueness of each workplace and its association with burnout as we studied here could also explain the array of burnout percentages observed in the evidence [9, 23, 25, 26, 27] and the lower scores at our institution. The congruency seen between attending surgeons and their level of job control, sense of community and reward, and our institutional values (Fig. 2) may have contributed to their well-being and mitigated burnout. Residents have consistently reported higher burnout levels than practicing physicians do across multiple surgical and nonsurgical specialties [9, 10, 14, 23, 26, 27]. Our residents followed a similar pattern, with higher levels of depersonalization than attending surgeons. Fellows reported lower levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization than attending surgeons. We did not find any published studies evaluating burnout in this population. The shorter length of time fellows train and expect to remain in a specific workplace could be reasons for their lower burnout rates. Overall, our results align with the results of several studies showing that practicing surgeons, faculty leaders, and trainees experience different burnout rates [9, 26, 27].

Problematic Areas of Work life in Orthopaedic Attending Surgeons, Fellows, and Residents

Heavy workload, or job exceeding human limits, was the most problematic area both in our quantitative survey and qualitative analysis. Although the Areas of Worklife Survey allowed us to pinpoint which areas of work life were most concerning, the open text comments allowed us to understand how. Interventions to address heavy workload should address excessive administrative tasks and expectations, technology in terms of the electronic medical platform and hospital wide emailing, workflow and structure, as well as personal, clinical, and academic role conflicts. Specific examples include training on time management, purposeful routing of emails to avoid unnecessary overloading, decreasing the number or length of mandatory meetings, and reducing the administrative workload by increasing human resources such as physician assistants, research assistants, medical assistants, and scribes. Interestingly, through open comment analysis, we identified four additional problematic work life domains not included in the Areas of Worklife Survey (resources, interactions, environment, and self-care), representing potential areas for future studies.

Areas of Work life Associated with Burnout in Orthopaedic Attending Surgeons, Fellows, and Residents

Heavier workload was associated with worsening emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in our population. Although we found no studies evaluating the relationship between workload and burnout in orthopaedic surgery, studies have shown heavy workload to be an important “stressor” for healthcare workers in general [22], surgeons [29], and orthopaedic leaders [25]. Residents, fellows, and attending physicians reported different relationships in this domain, however. Stronger correlations were seen in residents compared with attendings, suggesting that a heavier workload had a stronger association with resident well-being than attending surgeons; which is perhaps due to their lower level of experience.

Lower job control was also associated with worsening levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in our population. Interestingly, though considered separately in the Areas of Worklife Survey, our qualitative analysis revealed how job control and workload are intimately connected (Table 2). Portoghese et al. [22] found that in hospital workers experiencing a high workload, emotional exhaustion was aggravated by low job control. Similarly, our participants expressed frustrations about being excluded from decision-making processes. Lacking the ability to make and weigh-in on decisions could explain the link between job control, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization seen in our cohort. Therefore, consulting physicians and including them in institutional decisions could potentially improve their sense of job control and mitigate burnout. Further studies should be done, however, to further understand the relationship between these parameters to derive more concrete actionable interventions in terms of job control.

A notable finding in our study was the varying nature and degrees of correlations between burnout and work-life domains seen in orthopaedic surgeons, fellows, and residents, despite sharing the same work environment. Nowhere in the evidence has burnout been compared between these three groups. Resident and attending surgeon correlations between emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and areas of work life shared a similar pattern. Meanwhile, fellows demonstrated markedly different relationships between the same domains; suggesting that interventions to address burnout must be different between groups. Therefore, although burnout interventions targeted to addressing workload and job control may be appropriate for orthopaedic residents and attending surgeons; those targeting sense of fairness and community at work may be more fitting to fellows.

Conclusions

We found higher markers of burnout among residents than among attending surgeons and fellows, and we detected strong, distinct correlations between emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and work life domains across the stages of orthopaedic careers. Although we found burnout to be most strongly associated with excessive workload and limited job control in orthopaedic residents and attending surgeons, it was most strongly associated with a decreasing sense of fairness and community in orthopaedic fellows. Given these findings, institutions should develop strategies to improve physician well-being specific to each of these different populations. Hospitals should evaluate the balance between administrative tasks, expectations and support, carefully assess the effect of the electronic medical platform, and work to improve workflow efficiencies (such as streamlined email communications). Orthopaedic surgeons should be consulted and included in leadership and institution decision-making processes. Residency programs should evaluate the resident working environment with a focus on workload, job control, and reward. Future studies at other institutions may determine to what degree our findings generalize elsewhere, but we believe they will likely fit well within urban, academic practice settings. Additional qualitative study, including semi-structured interviews or focus groups, would also help to further elucidate the relationship between burnout and these specific areas of work-life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the orthopaedic surgeons, fellows and residents who participated in this study, despite their incredibly busy work lives. We also thank the Hospital of Special Surgery Surgeon-in-Chief Grant board members for recognizing the importance of this issue and funding this study.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that neither he nor she, nor any member of his or her immediate family, has funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, USA.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements, Section VI, with Background and Intent. 2017. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_Section VI_with-Background-and-Intent_2017-01.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- 2.American Association of Medical College. Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty. 2017. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2017. Accessed June 30, 2020.

- 3.Ames SE, Cowan JB, Kenter K, Emery S, Halsey D. Burnout in orthopaedic surgeons: a challenge for leaders, learners, and colleagues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017:99:e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appelbaum NP, Lee N, Amendola M, Dodson K, Kaplan B. Surgical resident burnout and job satisfaction: the role of workplace climate and perceived support. J Surg Res. 2019;234:20-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaton DE, Clark JP. Qualitative research: a review of methods with use of examples from the total knee replacement literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009:91;107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate Medical Education, 2018-2019. JAMA. 2019:322; 996–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers CC, Ihnow SB, Monroe EJ, Suleiman LI. Women in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg. 2018:100;e116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherf J. A snapshot of U.S. orthopaedic surgeons: results from the 2018 opus survey. Am Acad Orthop Surg; 2019. Available at: https://www.aaos.org/aaosnow/2019/sep/youraaos/youraaos01/#5d30ea35-563e-4748-a001-8882990e0dc0-5. Accessed June 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels AH, DePasse JM, Kamal RN. Orthopaedic surgeon burnout: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016:24;213-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durning SJ, Costanzo M, Artino AR, Dyrbye LN, Beckman TJ, Schuwirth L, Holmboe E, Roy MJ, Wittich CM, Lipner RS, van der Vleuten C. Functional neuroimaging correlates of burnout among internal medicine residents and faculty members. Front Psychiatry. 2013:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Shanafelt TD. Defining burnout as a dichotomous variable. J Gen Intern Med. 2009:24;440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Sinsky CA, Goeders LE, Satele DV, Shanafelt TD. Medical licensure questions and physician reluctance to seek care for mental health conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017:92;1486-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004:6;e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill J, Smith R. Monitoring stress levels in postgraduate medical training. Laryngoscope. 2009:119;75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lebares CC, Guvva EV, Ascher NL, O’Sullivan PS, Harris HW, Epel ES. Burnout and stress among us surgery residents: psychological distress and resilience. J Am Coll Surg. 2018:226;80-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leiter MP, Maslach C. Areas of Worklife Survey Manual and Sampler Set. 5th ed. Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden Inc.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leiter MP, Maslach C. Latent burnout profiles: a new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burn Res. 2016:3; 89-100. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015:4;324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marsh JL. Avoiding burnout in an orthopaedic trauma practice. J Orthop Trauma. 2012:26;34-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001:52;397-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 4th ed. Menlo Park, California: Mind Garden, Inc.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portoghese I, Galletta M, Coppola RC, Finco G, Campagna M. Burnout and workload among health care workers: the moderating role of job control. Saf Health Work. 2014:5;152-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pulcrano M, Evans SRT, Sosin M. Quality of life and burnout rates across surgical specialties: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2016:151;970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, Mata DA. Prevalence of burnout among physicians. JAMA. 2018:320;1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saleh KJ, Quick JC, Conaway M, Sime WE, Martin W, Hurwitz S, Einhorn TA. The prevalence and severity of burnout among academic orthopaedic departmental leaders. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007:89;896-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sargent MC, Sotile W, Sotile MO, Rubash H, Barrack RL. Stress and coping among orthopaedic surgery residents and faculty. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004: 88;2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sargent MC, Sotile W, Sotile MO, Rubash H, Barrack RL. Quality of life during orthopaedic training and academic practice. J Bone Joint Surg. 2009:91;2395-2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev Int. 2009:14;204-220. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, Collicott P, Novotny PJ, Sloan J, Freischlag JA. Burnout and career satisfaction among american surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009:250;463-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, Sloan J, West CP. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general us working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015:90;1600-1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017:92;29-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017:177;1826-1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spinelli WM, Fernstrom KM, Galos DL, Britt HR. Extending our understanding of burnout and its associated factors: providers and staff in primary care clinics. Eval Health Prof. 2016:39;282-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas NK. Resident Burnout. JAMA. 2004:292;2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Vendeloo SN, Brand PL, Verheyen CC. Burnout and quality of life among orthopaedic trainees in a modern educational programme: importance of the learning climate. Bone Joint J. 2014:96;1133-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016:388;2272-2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.