Abstract

Animal behaviours that are superficially similar can express different intents in different contexts, but how this flexibility is achieved at the level of neural circuits is not understood. For example, males of many species can exhibit mounting behaviour towards same- or opposite-sex conspecifics1, but it is unclear whether the intent and neural encoding of these behaviours are similar or different. Here we show that female- and male-directed mounting in male laboratory mice are distinguishable by the presence or absence of ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs)2–4, respectively. These and additional behavioural data suggest that most male-directed mounting is aggressive, although in rare cases it can be sexual. We investigated whether USV+ and USV− mounting use the same or distinct hypothalamic neural substrates. Micro-endoscopic imaging of neurons positive for oestrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) in either the medial preoptic area (MPOA) or the ventromedial hypothalamus, ventrolateral subdivision (VMHvl) revealed distinct patterns of neuronal activity during USV+ and USV− mounting, and the type of mounting could be decoded from population activity in either region. Intersectional optogenetic stimulation of MPOA neurons that express ESR1 and vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) (MPOAESR1∩VGAT neurons) robustly promoted USV+ mounting, and converted male-directed attack to mounting with USVs. By contrast, stimulation of VMHvl neurons that express ESR1 (VMHvlESR1 neurons) promoted USV− mounting, and inhibited the USVs evoked by female urine. Terminal stimulation experiments suggest that these complementary inhibitory effects are mediated by reciprocal projections between the MPOA and VMHvl. Together, these data identify a hypothalamic subpopulation that is genetically enriched for neurons that causally induce a male reproductive behavioural state, and indicate that reproductive and aggressive states are represented by distinct population codes distributed between MPOAESR1 and VMHvlESR1 neurons, respectively. Thus, similar behaviours that express different internal states are encoded by distinct hypothalamic neuronal populations.

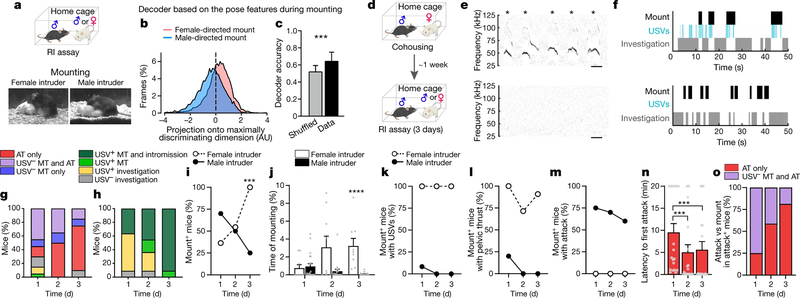

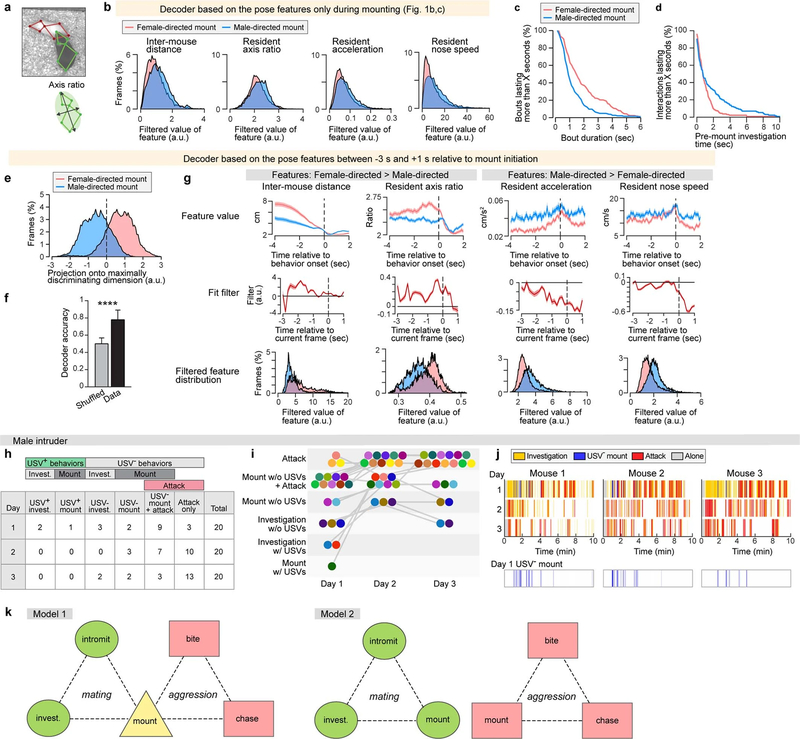

To investigate whether female- and male-directed mounting in mice could be behaviourally discriminated, we first attempted to train a machine-learning-based classifier5 to distinguish mounting in these two contexts (Fig. 1a, Methods). The performance of classifiers trained using pose features from mounting bouts alone was only slightly better than chance (63%) (Fig. 1b, c, Extended Data Fig. 1a, b). However, when trained using features extracted between −3 s and 1 s relative to mount initiation (at t = 0), classifier performance was improved to 78% (Extended Data Fig. 1e–g). This suggested that features from associated actions—more than from mounting itself—distinguish same-sex- and opposite-sex-directed mounting.

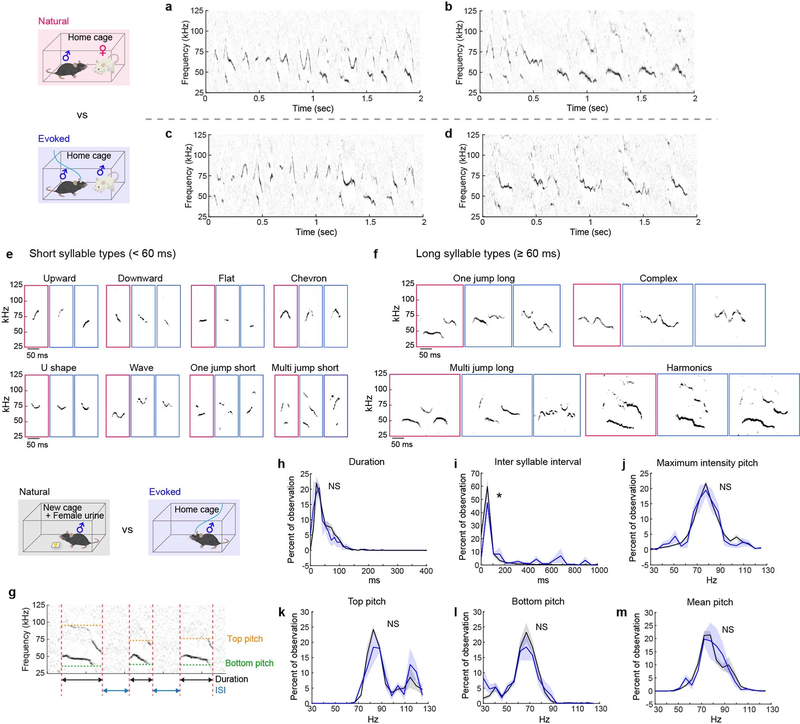

Fig. 1 |. Female- and male-directed mounting are distinct male social behaviours.

a, Experimental design (top) and representative video stills for female- and male-directed mounting (bottom). RI, resident–intruder. b, c, Decoding the sex of the intruder from female- versus male-directed mounting. AU, arbitrary units. b, Projection of mouse pose features from mounting bouts onto the maximally discriminating dimension of the decoder. c, Decoder accuracy compared with shuffled data. Fifty-four behaviour sessions, Mann–Whitney U test, ***P = 0.0004. d, Schematic illustrating resident–intruder assay. Male intruder tests, n = 20; female intruder tests, n = 11. e, Representative spectrograms during female-directed (top) and male-directed (bottom) mounting. Scale, 100 ms. Asterisks indicate USV syllables. f, Representative raster plots indicating mount, USV and investigation episodes during interaction with female (top) or male (bottom) intruder. g, h, Distribution of social behaviours by a male mouse that was initially naive to male, across three consecutive days with a male (g) or female (h) intruder. See Extended Data Fig. 1h–j for details. AT, attack; MT, mount. i, j, Fraction of mice exhibiting mounting (i) and time spent mounting (j) on each test day. i, Fisher’s test, ***P = 0.0002; j, Kruskal–Wallis test, ****P < 0.0001. k–m, Fraction of mice exhibiting mounting with USVs (k), pelvic thrust (l) or attack (m) on each test day. n, o, Quantification of behaviours towards male intruders on each test day. n, Latency to first attack (Methods). n = 20, Friedman test, ***P = 0.0003, 0.0002. o, Fraction of mice exhibiting USV− mount plus attack versus attack only. Data are mean ± s.e.m. All statistical tests are two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons when necessary (Supplementary Table 2).

We therefore investigated which associated behaviours best discriminate the mounting of female versus male mice by male mice. Audio recordings revealed that female-directed mounts were invariably accompanied by USVs2–4 (Fig. 1e, f, h, k, Supplementary Video 1), whereas most male-directed mounts were not (Fig. 1e–g, k, Supplementary Video 2; the rare exceptions are discussed below). In addition, female-directed mounts were followed usually by pelvic thrusting and intromission (Fig. 1h, l), whereas male-directed mounting was followed typically by attack (Fig. 1g, m). Finally, male-directed USV− mounting was more frequent during initial social encounters when mice were socially inexperienced (day 1 in Fig. 1g, i, j, Extended Data Fig. 1h–j), and diminished as mice gained aggressive experience6,7 (days 2 and 3 in Fig. 1n, o). These data suggest that most cases of naturally occurring female- and male-directed mounting in this mouse strain reflect underlying sexual and aggressive motivational states, respectively.

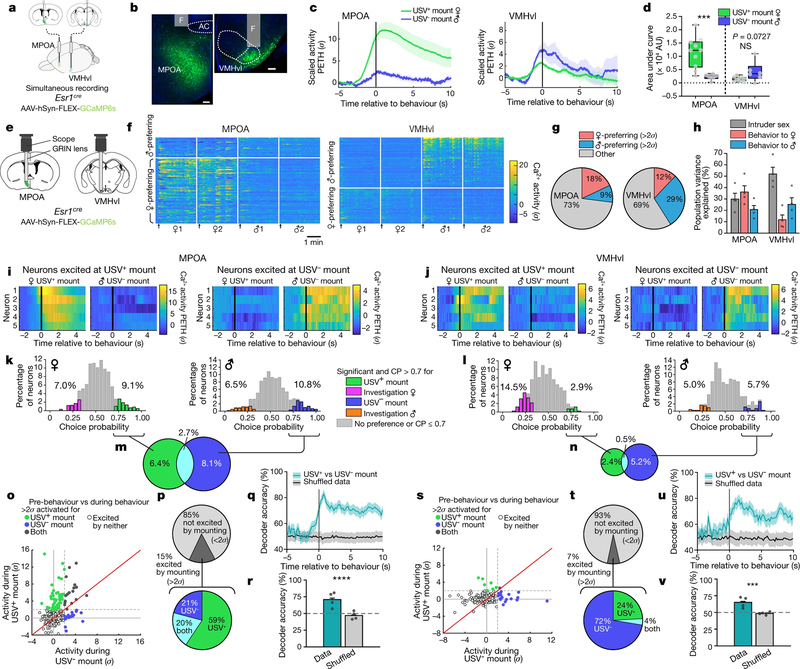

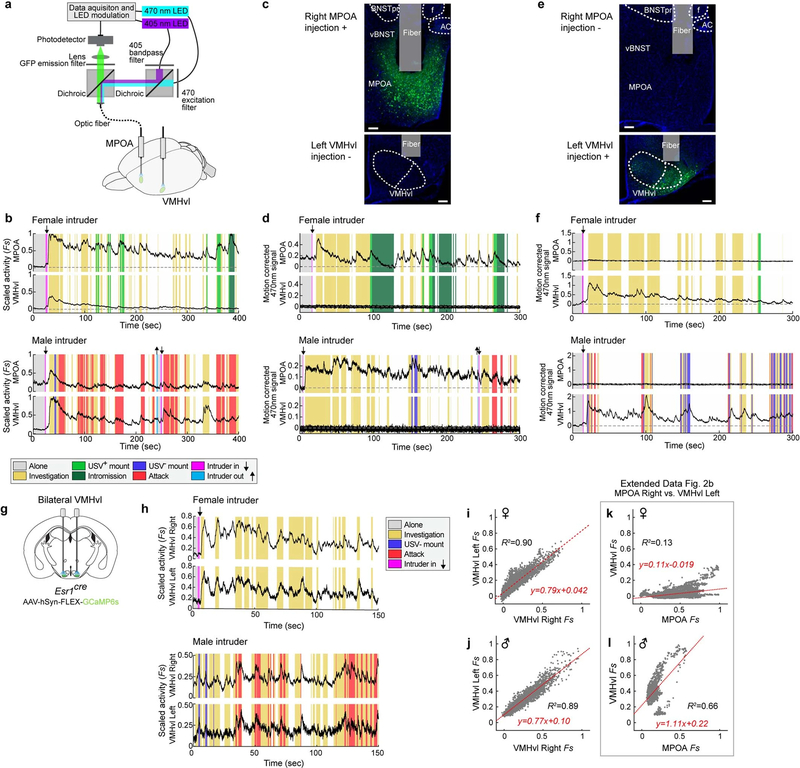

We investigated next how the hypothalamus encodes these two forms of mounting. In principle, female- and male-directed mounting could reflect the presence of behaviour-specific neurons that are either common or distinct (Extended Data Fig. 1k); alternatively, the two forms of mounting could reflect a more general encoding of aggressive and sexual internal states. ESR1+ neurons in both the MPOA and VMHvl have previously been implicated in male mounting8–12. To directly compare activity in these two populations during female- and male-directed mounting in the same mice, we performed simultaneous bulk calcium measurements in MPOAESR1 and VMHvlESR1 neurons using fibre photometry13 (Fig. 2a, b, Extended Data Fig. 2, Methods). The activity in the former area was relatively higher during USV+ mounting, whereas activity in the latter area trended higher during USV− mounting (Fig. 2c, d). We observed a similar relationship during other phases of female- versus male-directed social behaviour (Extended Data Fig. 3).

Fig. 2 |. Distinct neural representations of USV+ and USV− mounting in MPOAESR1 and VMHvlESR1 neurons.

a, Schematic illustrating dual-site fibre photometry. b, Representative GCaMP6s expression and optic fibre tract. Scale bars, 100 μm. n = 10. AC, anterior commissure; F, optic fibre tract. See Extended Data Fig. 2c, e for examples from control experiments. c, d, Averaged calcium signals in MPOAESR1 and in VMHvlESR1 aligned to mount onset (Methods). PETH, peri-event time histograms. d, Integrated activity during mounting. ***P = 0.001. USV+ mount, n = 10; USV− mount, n = 6. e, Schematic of micro-endoscopic calcium imaging. GRIN, gradient index. f, Representative calcium activity raster during social encounters, sorted by intruder sex preference and response magnitude. Arrows, intruder introduction. g, Fraction of female- and male-preferring MPOAESR1 and VMHvlESR1 neurons. h, Main sources of variance in population activity (Methods). n = 4 for each region. i, j, Neural activity of example mount-activated neurons, shown as PETHs (normalized to 2.5 to 1.5 s before mount onset). Each pair of rasters is from the same neuron. k, l, Choice probabilities (CP) for female- or male-directed investigation versus USV+ or USV− mounting (coloured bars indicate significance, Methods). m, n, Proportion of cells showing significance (Methods) and choice probability >0.7 for USV+ mounting, USV− mounting or both. o, p, s, t, Average activity per neuron (σ, relative to pre-mount activity) during USV+ versus USV− mounting. o, s, Scatter plots. p, t, Proportion of cells excited (>2σ) during mounting. q, r, u, v, Accuracy of time-evolving (q, u) or frame-wise (r, v) decoders predicting USV+ from USV− mounting, trained on neural activity. n = 4, ****P < 0.0001. d, r, v, Mann–Whitney U test. Data are mean ± s.e.m., except in box plots (d), in which centre lines indicate medians, box edges represent the interquartile range and whiskers denote minimal and maximal values. All statistical tests are two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons when necessary (Supplementary Table 2).

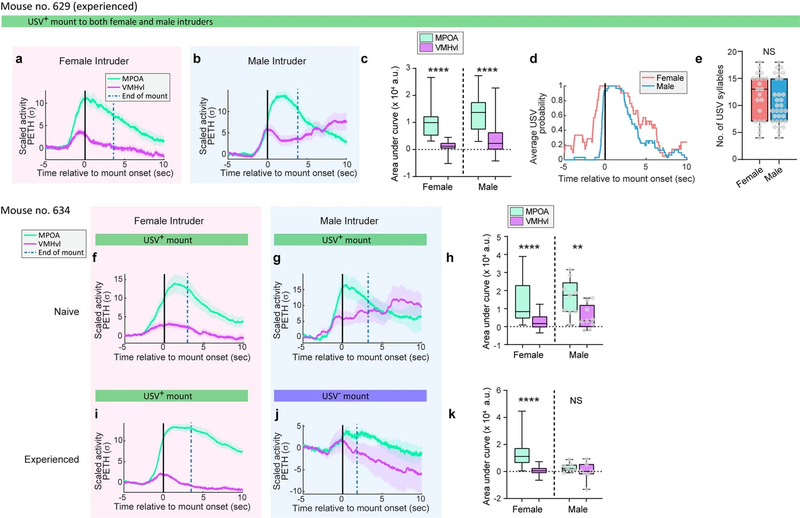

Notably, in two out of ten individual male mice (no. 629 and no. 634), activity during male-directed mounting resembled that typically observed during female-directed mounting—that is, activity was relatively higher in MPOAESR1 than in VMHvlESR1 neurons (Extended Data Fig. 4b, c, g, h). Furthermore, in both cases male-directed mounting was accompanied by USVs (Extended Data Fig. 4d, e). These rare examples may reflect mistaken sex identification14 and/or male-directed affiliative (that is, bisexual) behaviour (Supplementary Note 2), and indicate that neural responses in these nuclei are not simply sensory representations of intruder sex.

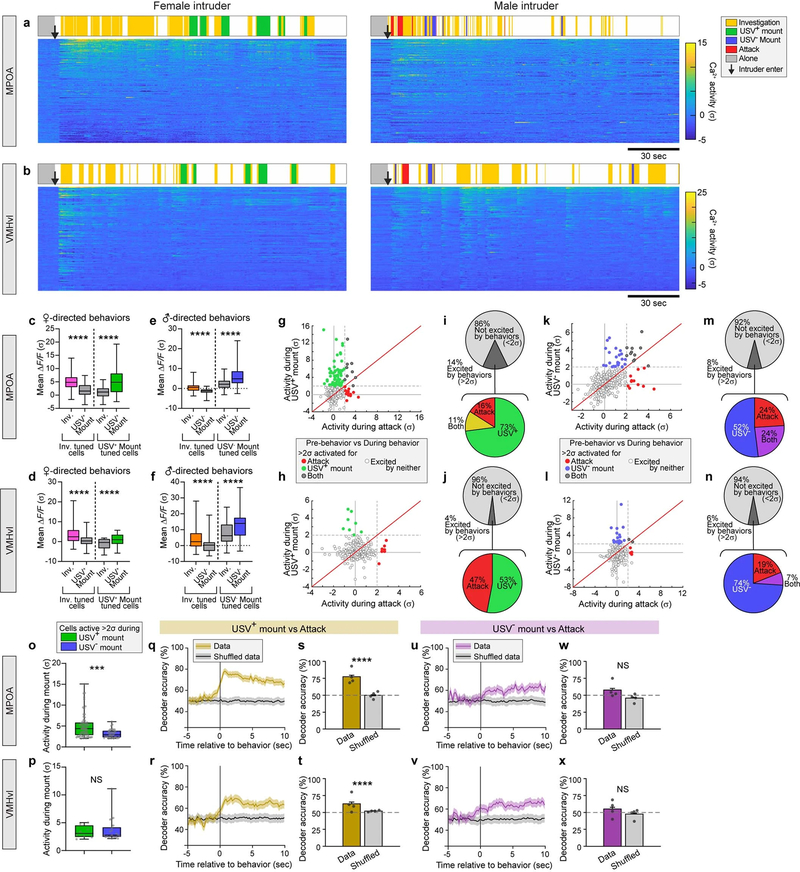

The quantitative differences in bulk ESR1+ neuronal activity in each nucleus during sexual (USV+) versus aggressive (USV−) mounting (Fig. 2d) could reflect differences in the activity of the same neurons or the activation of different subsets of ESR1+ neurons6,15,16. To distinguish these alternatives, we performed single-cell-resolution calcium imaging of ESR1+ neurons using head-mounted micro-endoscopes17, in either the MPOA or VMHvl6, in freely behaving mice (Fig. 2e, Methods). To our knowledge, the single-cell-resolution imaging of MPOA activity during social behaviours has not previously been reported.

In the MPOA (as in the VMHvl6), we observed that distinct populations of ESR1+ neurons responded during female- and male-directed social interactions (Fig. 2f, Extended Data Fig. 5a–h). However female-preferring neurons outnumbered male-preferring neurons by twofold in the MPOA (18% versus 9%) (Fig. 2g left)—the reverse of the ratio in the VMHvl (12% versus 29%) (Fig. 2g right). In both structures, much of the variance in population activity was explained by intruder sex (30–52%) (grey bars in Fig. 2h), although in the MPOA a higher fraction of the variance was explained by behaviour (57%,) (pink and blue bars in Fig. 2h) than was the case in the VMHvl (about 37%) (Methods).

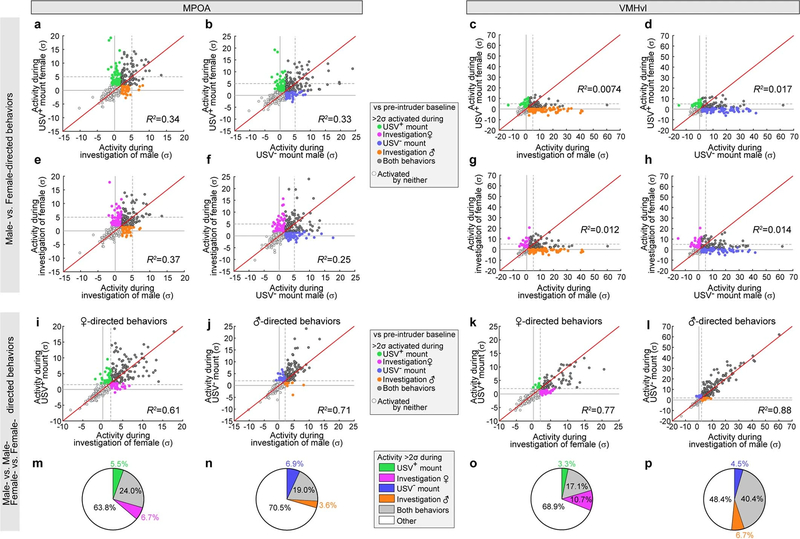

To further investigate the relationship between neural activity and behaviour, we performed a frame-by-frame annotation of behaviour in synchronously acquired video recordings5 (Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). Both the MPOA and VMHvl contained distinct populations of neurons that were activated at the onset of USV+ and USV− mounting, respectively (Fig. 2i, j). However, overall the relative activity of each cell during mounting and investigation was highly correlated—for intruders of a given sex—in both the MPOA (R2 = 0.61–0.71) (Extended Data Fig. 5i, j) and VMHvl (R2 = 0.77–0.88) (Extended Data Fig. 5k, l), and was poorly correlated across different sexes (Extended Data Fig. 5a–h). A small proportion of neurons was preferentially activated (more than 2σ) during mounting but not sniffing (green or blue points and sectors in Extended Data Fig. 5i–l and 5m–p, respectively). This suggests that the activity observed during USV+ or USV− mounting is not simply a reflection of the sex of the intruder (which would also contribute to neuronal activation during sniffing), but that at least some neurons are selectively activated during USV+ or USV− mounting behaviour. However, cells that responded during both behaviours were more numerous and more strongly activated than those that responding during one behaviour only (grey points in Extended Data Fig. 5i–l, grey sectors in Extended Data Fig. 5m–p).

To further investigate the specificity of the behavioural responses, we computed the choice probability of each neuron for mounting (USV+ or USV−) versus investigation (sniffing)6. The choice probability of a neuron indicates how accurately the activity of the neuron can predict whether mounting or investigation is occurring, during each annotated frame in which the neuron is active18. In both the VMHvl and MPOA, 3–11% of ESR1+ neurons exhibited a choice probability of more than 0.7 for sexual (USV+) or aggressive (USV−) mounting, respectively (relative to investigation), that was substantially higher (over 2σ) compared to shuffled behavioural annotations (Fig. 2k, l, Methods). This confirms that both nuclei contain some cells that are tuned for mounting, independently of the sex of the intruder. However, these cells appeared to lie at the extremes of a continuum of relative ‘tuning’ for mounting versus investigation. Nevertheless, in both the MPOA and VMHvl, there was minimal overlap between USV+-mount-tuned and USV−-mount-tuned cells identified by choice probability analysis (Fig. 2m, n). Similarly, in both nuclei the ESR1+ subpopulations that were preferentially activated (more than 2σ) during the two types of mounting were largely distinct (coloured points in Fig. 2o, p, s, t). Accordingly, linear decoders—a type of binary classifier based on a support vector machine learning algorithm—could be trained to distinguish these two types of mounting on the basis of the pattern of neuronal activity in both nuclei, with 70–80% accuracy (Fig. 2q, r, u, v, Methods). Nevertheless, decoder performance may reflect the encoding of the sex of the intruder as well as of mount type, because the two are highly correlated.

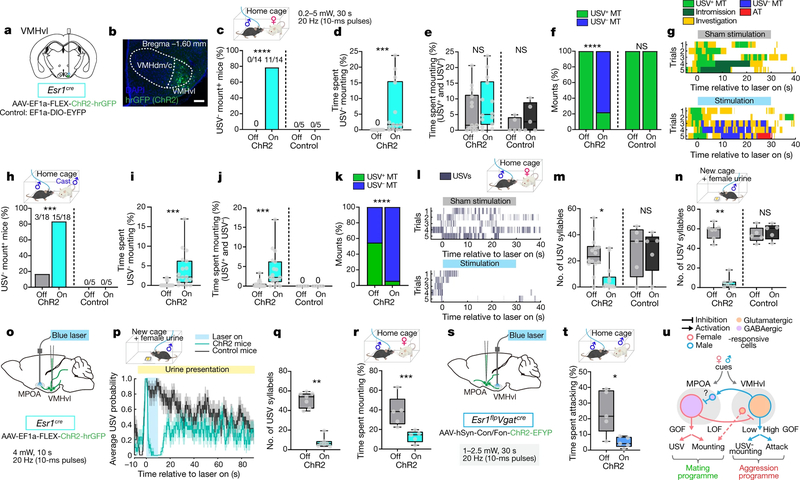

We next investigated the respective causal roles of the MPOA and VMHvl in sexual and aggressive mounting. Although male mounting is promoted by electrical stimulation of the MPOA19,20, we observed only weak and inefficient promotion of mounting by activating MPOAESR1 neurons (purple bars in Fig. 3c, d), confirming a previous study8. Because MPOAESR1 neurons comprise a mixture of approximately 80% GABAergic and approximately 20% glutamatergic neurons8,21 and because mating-induced Fos expression is stronger in preoptic inhibitory than in excitatory neurons15, we reasoned that intersectionally targeting ESR1+ GABAergic neurons might enrich for MPOA neurons that promote male sexual behaviour.

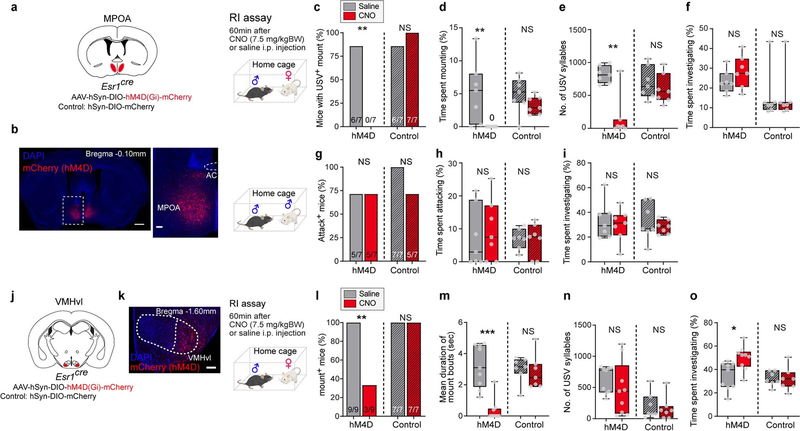

Fig. 3 |. MPOAESR1∩VGAT neurons control male sexual behaviour.

a, Strategy to express ChR2 in MPOAESR1∩VGAT or MPOAESR1 neurons using sexually and socially experienced Esr1flp Vgatcre (blue bars) or Esr1flp (purple bars) mice. Con/Fon, Cre-ON/FLP-ON; fDIO, FLP-ON. b, ChR2 expression in MPOA in Esr1flp Vgatcre mice with boxed region magnified (right). Scale bars, 500 μm (left), 100 μm (right). n = 7. c, d, Optogenetically triggered mounting towards male intruders. c, Fraction of mice mounting. NS, not significant; ***P = 0.0006. d, Fraction of photostimulation trials with mounting. ****P < 0.0001. MPOAESR1∩VGAT, n = 7; MPOAESR1, n = 8. Off, sham photostimulation; On, during photostimulation (Extended Data Fig. 7). e–g, ChR2-triggered USVs with male intruder. e, USV raster plots. f, Fraction of trials with USVs. g, Number of USV syllables per trial. n = 7. f, **P = 0.0012; g, **P = 0.0025. h, Per cent of mount bouts that were USV+ during photostimulation. Numbers indicate total mounts (USV+ and USV−) observed. i–k, Photostimulation of MPOAESR1∩VGAT neurons initiated during attack towards male intruder. i, Behaviour raster plots. j, Fraction of total time spent attacking. k, Fraction of attacks converted to USV+ mounts. n = 6. j, **P = 0.0027; k, **P = 0.0014. l–o, Solitary male mice. l, Fraction of USV+ trials in solitary male mice during photostimulation. n = 7. **P = 0.0045. m, Strategy to optogenetically inhibit29 MPOAESR1 neurons in male Esr1cre mice. n, o, Female-urine-evoked USVs during MPOAESR1 photoinhibition (pale blue bar). n, Probability of USVs. GtACR2 mice, mice injected with GtACR2-coding AAV; control mice, mice injected with mCherry-coding AAV. o, Number of USV syllables. Orange, GtACR2, n = 7; grey, control, n = 8, ***P = 0.0008. Qualitatively similar results were obtained with iC++ inhibition of MPOAESR1∩VGAT neurons. c, Fisher’s test; d, f, g, j–l, o, Kruskal–Wallis test. Data are mean ± s.e.m. except for box plots (see Fig. 2 legend for box plot definitions). All statistical tests are two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons when necessary (Supplementary Table 2).

Indeed, intersectional optogenetic activation22 of MPOAESR1∩VGAT neurons using Esr1flp Vgatcre (Vgat is also known as Slc32a1) mice (Fig. 3a, b) robustly and efficiently promoted investigation and mounting of a male intruder, at stimulation intensities over an order of magnitude lower (0.5–1.5 mW) than those previously reported using Esr1cre mice8 (blue in Fig. 3c, d, Extended Data Fig. 7a–c, Supplementary Video 3). Importantly, stimulation of MPOAESR1∩VGAT neurons evoked USV+ mounting towards both male and female intruders (Fig. 3e–h, Extended Data Fig. 7a–c, j–m), as well as towards some inanimate objects (Supplementary Video 4). Optogenetic stimulation also elicited USVs in solitary male mice23 (Fig. 3l, Extended Data Fig. 7i), which confirms that vocalizations were not secondary to mounting or emitted by intruders. Optogenetically evoked USVs exhibited similar syllable patterns and acoustic features to those emitted naturally by male mice exposed to female mice2–4,23,24 or to female urine25 (Extended Data Fig. 8). Notably, activation of MPOAESR1∩VGAT neurons also rapidly interrupted ongoing attack, and converted it to male-directed USV+ mounting (Fig. 3i–k, Extended Data Fig. 7f, g, Supplementary Video 5). Furthermore, activation of MPOAESR1∩VGAT neurons in female mice evoked male-typical USV+ mounting behaviour towards male mice8 and inanimate objects (Supplementary Video 6). Thus, activation of MPOAESR1∩VGAT neurons triggered a programme of male-typical mounting behaviour in both male and female mice, independent of target identity. The silencing of MPOAESR1 neurons8 attenuated USVs evoked by female urine in solitary male mice25 (Fig. 3m–o), which indicates that these neurons are necessary for such vocalizations—as well as for mounting, as previously reported8 and confirmed here (Extended Data Fig. 9a–e).

Weak optogenetic stimulation of VMHvlESR1 neurons is known to promote mounting, whereas strong stimulation promotes attack12. However, it was not clear whether such mounting is sexual (USV+) or aggressive (USV−). Audio recordings indicated that weak VMHvlESR1 activation promoted USV− mounting towards both female and castrated male intruders, as well as attack (Fig. 4a–k, Extended Data Fig. 10b–d, f–i). These results suggest that mounting evoked by the activation of VMHvlESR1 neurons represents a low-intensity form of aggression. Nevertheless, the silencing of VMHvlESR1 neurons strongly suppressed spontaneous female-directed (sexual) mounting (Extended Data Fig. 9j–m), confirming and extending previous reports of weak inhibitory effects9–11. These differential effects of gain- versus loss-of-function manipulations of VMHvlESR1 neurons on USV+ versus USV− mounting probably reflect influences on distinct female- and male-responsive subpopulations6,16,26 (Extended Data Fig. 10q, Supplementary Note 3).

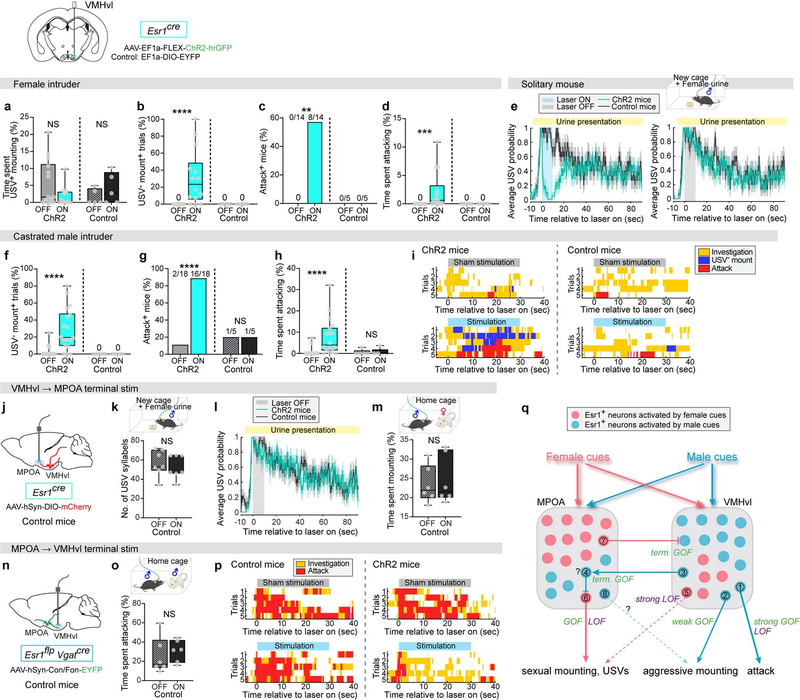

Fig. 4 |. VMHvlESR1 neurons promote aggressive mounting and inhibit USV production.

a, Strategy to optogenetically activate VMHvlESR1 neurons in naive male mice. b, ChR2 expression in VMHvl. Scale bar, 100 μm. n = 18. VMHdm/c, dorsomedial and central parts of the VMH. c–g, Behaviours towards female intruders during photostimulation. ChR2 mice, mice injected with ChR2-coding AAV; control mice, mice injected with EYFP-coding AAV. ChR2, n = 14; control, n = 5. c, Fraction of mice displaying USV− mounting. ****P < 0.0001. d, Per cent time spent USV− mounting. ***P = 0.001. e, Per cent time spent in all mounting. f, Fraction of USV+ and USV− mounts. ****P < 0.0001. g, Behaviour raster plots. h–k, Behaviours towards castrated male intruders. ChR2, n = 18; control, n = 6. h, Fraction of mice displaying USV− mounting. i, Per cent time spent USV− mounting. ***P = 0.0003. j, Per cent time spent in all mounting. ***P = 0.0002. k, Fraction of USV+ and USV− mounts. ****P < 0.0001. l, m, Spontaneous USVs towards female intruder during VMHvlESR1 photostimulation. l, USV raster plots. m, Number of USV syllables. ChR2, n = 14; control, n = 5. *P = 0.01. n, Female-urine-evoked USVs in solitary male mouse during photostimulation. ChR2, n = 14; control, n = 7. **P = 0.002. o, Strategy to optogenetically activate ESR1VMHvl→MPOA axon terminals. p–r, Female-urine-evoked USVs and mounting during terminal stimulation. p, Probability of USVs. q, Number of USV syllables. ChR2, n = 7; control, n = 7, **P = 0.0065. r, Per cent time spent mounting during photostimulation, triggered after mount onset. ChR2, n = 5, ***P = 0.0006. s, Strategy to optogenetically activate ESR1∩VGATMPOA→VMHvl axon terminals. t, Per cent time spent attacking during photostimulation, triggered after attack onset. ChR2, n = 5, *P = 0.034. u, Summary of perturbation effects. GOF, gain-of-function effect; LOF, loss-of-function effect only; low and high denote relative stimulation intensities in optogenetic gain-of-function experiments12. Function of minor cell populations (small circles) is hypothetical. More details are provided in Extended Data Fig. 10q, Supplementary Note 3. c, f, h, k, Fisher’s test. d, i, Wilcoxon test. e, j, m, n, q, r, t, Kruskal–Wallis test. Data are mean ± s.e.m., except for box plots (see Fig. 2 legend for definitions). All statistical tests are two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons when necessary (Supplementary Table 2).

Importantly, VMHvlESR1 stimulation did not simply fail to evoke USVs, but instead strongly inhibited the USVs elicited by female intruders or urine (Fig. 4l–n). We therefore asked where it is that this inhibitory effect is exerted. VMHvlESR1 neurons project strongly to the MPOA27. Optogenetic stimulation of VMHvlESR1 terminals in the MPOA strongly inhibited female-urine-evoked USVs25 (Fig. 4o–q), as well as female-directed mounting (Fig. 4r). As VMHvlESR1 neurons are largely excitatory16,26, this inhibitory effect may occur indirectly via local interneurons in the MPOA (Fig. 4u, Extended Data Fig. 10q, Supplementary Note 3). However, we cannot exclude the activation of collateral targets27 via back-propagation of spikes. Conversely, optogenetic stimulation of MPOAESR1∩VGAT terminals in VMHvl strongly inhibited aggression (Fig. 4 s, t). Thus, activation of MPOA-projecting VMHvlESR1 (ESR1VMHvl→MPOA) and VMHvl-projecting MPOAESR1∩VGAT (ESR1∩VGATMPOA→VMHvl) neurons suppressed female-directed mounting and male-directed aggression, respectively, implying a reciprocal inhibitory circuit motif as previously suggested28 (Fig. 4u).

We have investigated how same- and opposite-sex-directed male mounting is controlled in the hypothalamus. We find that these two forms of mounting are distinct behaviours that are controlled by different hypothalamic cell populations. Imaging experiments in each nucleus revealed relatively rare populations of USV+- or USV−-mount-selective cells; most MPOAESR1 and VMHvlESR1 neurons exhibited mixed selectivity for multiple social behaviours towards an intruder of a given sex. These data suggest that these two major populations principally control reproductive and aggressive states, respectively, which explains the causally dominant behavioural effects of optogenetic stimulation. Nevertheless, the MPOA—as with the VMHvl6,16,26—also contains a minor subpopulation of neurons (about 9%) (Fig. 2g) that is selectively activated during the opposing state. In the case of the VMHvl, it seems likely that the female-preferring cells are required for mating behaviour9,10 (Extended Data Figs. 9l, m, 10q, Supplementary Note 3). In the case of the MPOA, the male-preferring ESR1+ subpopulation could either indirectly promote aggression or suppress mounting during fighting. Whatever the case, our data suggest that aggressive and reproductive (sexual) states are represented by heterogeneous cell populations distributed across multiple hypothalamic nuclei. More generally, they show that a superficially similar motor action can be controlled by distinct neural subpopulations that encode opposing motivational states, at the level of the hypothalamus.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2995-0.

Methods

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The order of male or female intruder experiments were performed in the random order in imaging experiments, but were not randomized in functional manipulation experiments. Investigators were blind to experimental or control groups during functional manipulation experiments and outcome assessment.

Mice

All experimental procedures involving the use of live mice or their tissues were carried out in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by the Institute Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and the Institute Biosafety Committee (IBC) at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). All C57BL/6N mice used in this study, including wild-type and transgenic mice, were bred at Caltech. BALB/c male and female mice were used as intruder mice and bred at Caltech or purchased from Charles River Laboratories (CRL). BALB/c ovariectomized female mice and castrated male mice were purchased from CRL. Experimental mice were used at the age of 2–4 months. Intruder mice were used at the age of 2–6 months and were maintained with three to five cage mates to reduce their aggression. Esr1cre knock-in mice12 (Jackson Laboratory stock no. 017911), Esr1flp knock-in mice (described in ‘Generation of Esr1flp knock-in mice’) and Slc32a1 (Vgat)cre knock-in mice30 (Jackson Laboratory stock no. 028862) were backcrossed into the C57BL/6N background (>N10) and bred at Caltech. Heterozygous Esr1cre, Esr1flp or double heterozygotes Esr1flp Vgatcre mice were used for cell-specific targeting experiments, and were genotyped by PCR analysis using genomic DNA from tail or ear tissue. All mice were housed in ventilated micro-isolator cages in a temperature-controlled environment (median temperature 23 °C, humidity 60%), under a reversed 11-h dark–13-h light cycle, with ad libitum access to food and water. Mouse cages were changed weekly.

Generation of Esr1flp knock-in mice

Esr1flp knock-in mice were generated at the Caltech Genetically Engineered Mouse Services core facility, following standard procedures. The targeting vector was designed in the same way as Esr1cre 12. Instead of Cre recombinase, an F2A sequence and a Flp recombinase31 coding sequence were inserted at the 3′ end of the Esr1 coding sequence, by in-frame homologous recombination. Following electroporation of the targeting construct into 129S6/SvEvTac-derived TC-1 embryonic stem cells, correctly targeted cells were identified by PCR genotyping using the following primer sets: 5′ arm primers (6.7 kb), 5′-cccatggccactagacactt-3′ and 5′-acgtctccgcatgtcagaag-3′; 3′ arm primers (4 kb), 5′-taagggatatttgcctggccc −3′ and 5′-ctcgacgaccaatgacctct −3′. Positive embryonic stem cells were injected into recipient C57BL/6N blastocysts to generate chimeric males that were then bred with C57BL/6N female mice. Mouse genotype was determined by PCR using genomic DNA templates isolated from tail or ear tissue with the following primer sets: wild-type allele (0.6 kb) 5′-tggccactcatactagaaagccactg-3′ and 5′-ggaggaaatgaaaatacgtggacacaagtccc-3′; targeted allele (1 kb) 5′-ttgtgcccctctatgacctgctc −3′ and 5′- gggtccacgttcttgatgtcgct −3′.

Hormone treatment

To enhance the sexual receptivity of female mice, hormone primed BALB/c female mice were used as intruders in some experiments (Figs. 1, 4r, Extended Data Fig. 9c–f, l–o). Ovariectomized female mice received subcutaneous injections of 10 μg of β-oestradiol-3-benzoate (E8515, Sigma-Aldrich) in sesame oil (S3547, Sigma-Aldrich) at 48 h, and 500 μg progesterone (P0130, Sigma-Aldrich) at 4–6 h before behavioural experiments32.

Surgery

Surgeries were performed on adult Esr1cre, Esr1flp or Esr1flpVgatcre mice aged 8–12 weeks. Virus injection and implantation were performed as previously described26. In brief, mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane (0.8–5%) and placed on a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments). Then, 100–200 nl of virus was injected into the target area using a pulled glass capillary (World Precision Instruments) and a pressure injector (Micro4 controller, World Precision Instruments), at a flow rate of 20–50 nl min−1. Typically, the injection volumes were 200 nl for MPOA and 100 nl for VMHvl. For GCaMP viruses, the injection volumes were 150 nl for fibre photometry experiments and 200 nl for micro-endoscope experiments, for both MPOA and VMHvl. Stereotaxic injection coordinates were based on the Paxinos and Franklin atlas33 (MPOA, anterior–posterior: −0.1, medial–lateral: ±0.45, dorsal–ventral: −4.75; VMHvl, anterior–posterior: −1.5, medial–lateral: ±0.75, dorsal–ventral: −5.73). For optogenetic and fibre photometry experiments, single or dual optic fibres (optogenetics: diameter 200 μm, N.A., 0.22; fibre photometry: diameter 400 μm, N.A., 0.48; Doric lenses) were subsequently placed 250–300 μm above the virus injection sites and fixed on the skull with dental cement (Parkell). Mice were allowed to recover for at least two weeks before behavioural testing. For micro-endoscope experiments, virus injection and lens implantation were performed either on the same day, or one to two weeks apart, respectively. GRIN lenses (Inscoipix, diameter 0.6 × 7.3 or 1 × 9 mm) were slowly lowered into the brain without a cannula, and fixed to the skull with dental cement (Parkell). Mice were initially checked for epifluorescence signals three to four weeks after virus injection. To perform such checks, mice were either anaesthetized with isoflurane and mounted on a stereotaxic frame, or head-fixed and placed on a running wheel while awake. A head-mounted miniaturized micro-endoscope (nVista2 or nVista3, Inscopix) was then lowered over the implanted lens until GCaMP-expressing fluorescent neurons were in focus. If fluorescent neurons were not observed, the mice were returned to their cages and checked again on a weekly basis. If GCaMP-expressing neurons were detected, the micro-endoscope was aligned and a permanent baseplate was attached to the head with dental cement, as previously described34. To habituate mice to the weight of the micro-endoscope, a weight-matched dummy micro-endoscope (Inscopix) was attached to the baseplate, and the mice were allowed to recover for at least a week before behavioural testing.

Virus

The following AAVs were used in this study, with injection titres as indicated. When the original viral titre was high, AAVs were diluted with clean PBS on the day of use. AAV2-hSyn-DIO-hm4D-mCherry (3.7 × 1012 genome copies per ml), AAVDJ-hSyn-Con/Fon-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP (2.2 × 1012), AAVDJ-hSyn-Con/Fon-EYFP (2.5 × 1012) AAV2-EF1a-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP (2 × 1012), AAV5-EF1a-DIO-EYFP (3.2 × 1012), AAVDJ-EF1a-fDIO-hCh R2(H134R)-EYFP (2 × 1012) and AAVDJ-EF1a-fDIO-EYFP (2.1 × 1012) were purchased from the UNC vector core. AAV1-hSyn-Flex-GCaMP6 s (5 × 1012 for fibre photometry and 1 × 1012 for micro-endoscope imaging) was purchased from the U. Penn Vector Core. AAV2-hSyn-DIO-mCherry (2.5 × 1012) was purchased from Addgene. AAVDJ-hSyn-SIO-stGtAC R2-FusionRed (5.4 × 1012, Addgene plasmid no. 105677), and AAV2-E F1a-Flex-hChR2-V5-F2A-hrGFP12 (1.95 × 1012) were packaged at the HHMI Janelia Research Campus virus facility.

Histology

Following completion of behavioural experiments, histological verification of virus expression and implant placement were performed on all mice. Mice lacking correct virus expression or implant placement were excluded from the analysis. In brief, mice were perfused transcardially with 0.9% saline at room temperature, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 1× PBS. Brains were extracted and post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C, followed by 24 h in 30% sucrose/PBS at 4 °C. Brains were embedded in OCT mounting medium, frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C for subsequent sectioning. Brains were sectioned in 50–75-μm thickness on a cryostat (Leica Biosystems). Sections were washed with 1× PBS and mounted on Superfrost slides, then incubated for 30 min at room temperature in DAPI/PBS (0.5 μg/ml) for counterstaining, washed again and coverslipped. Sections were imaged with epifluorescent microscope (Olympus VS120).

Behavioural tests

Sexual and social experience and housing conditions.

For the experiment in Fig. 1, 8–12-week-old C57BL/6N male mice were individually cohoused with a BALB/c female mice for a week, and female mice were removed from the cages one day before the experiments. Hormone-primed BALB/c female mice or intact BALB/c male mice were used as intruders. For all optogenetic (except VMHvl cell body optogenetic stimulation; Fig. 4a–m), fibre photometry, micro-endoscope and chemogenetic experiments, transgenic mice were first separated from siblings and cohoused with C57BL/6N or BALB/c female mice for a week, then introduced to several BALB/c male intruders for 15 min for 3 consecutive days, to give them aggression experience. After sexual and social experience, male mice were always cohoused with female mice. If female mice became pregnant during the cohousing, new female mice were provided as cage mates. For VMHvl cell body optogenetic stimulation with intruder mice (Fig. 4a–m, Extended Data Fig. 10a–d,f–i), male mice were not sexually and socially experienced to avoid the development of excessive aggressiveness12,35. Male mice were separated from siblings on the day of surgery and then maintained under single-housing conditions. Castrated male mice were used as intruders to reduce baseline aggression of resident mice. Following the completion of testing with castrated male and female intruders, resident mice were cohoused with female mice for a week and then tested with female urine (Fig. 4n, Extended Data Fig. 10e) to evoke USVs.

Behaviour and audio recording.

All behavioural experiments were performed in conventional mouse housing cages (home cage or new cage) under red lighting, using the previously described behaviour recording setup36. Both top and front views of the behaviour videos were acquired at 30 Hz using video recording software, StreamPix7 (Norpix). Audio recordings were collected at a 300-kHz sampling rate using an Avisoft-UltraSoundGate 116H kit with a condenser ultrasound microphone CM16/CMPA (Avisoft-Bioacoustics), positioned 45 cm above the arena. Initiation of audio recording was synchronized with video recording via a signal generated by StreamPix7.

Resident–intruder test.

Mouse cages were not cleaned for a minimum of three days before the behavioural test, to retain the odours of the resident mouse. Resident mice were introduced to the behaviour recording setup in their home cage, and allowed to rest for at least five minutes before starting behaviour tests. For the experiments in Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 9c–f, l–o, resident mice were allowed to interact with female intruders for 15 min. For Fig. 1, resident mice were allowed to interact with male intruders for 20 min. When an excessive amount of aggression was observed, tests were terminated at 10 min. For Extended Data Fig. 9g–i, resident mice were allowed to interact with male intruders for 10 min. Behaviour tests were performed during the subjective dark period of the mouse housing room day–night cycle (from 2–8 h after lights off).

Optogenetic stimulation and inhibition.

Before initiating behavioural experiments, the light intensity achieved at the tip of the optic fibre was estimated by connecting an equivalent optic fibre to the patch cable, and measuring the light intensity at the tip of the fibre using a power meter. Laser power was controlled by turning an analogue knob on the laser power supply. Mice were connected to a 473-nm or 455-nm laser (Shanghai Laser and Optics Century or Changchun New Industries Optoelectronics Tech) via optical patch cords (diameter 200 μm, N.A., 0.22, Doric lenses and Thorlabs) and a rotary joint (Doric lenses). Mice were allowed to habituate to the cables after connecting them for at least 5 min before starting behaviour tests. The experimenter monitored mouse behaviour via a computer monitor in a room adjacent to the behavioural arena, and triggered the laser manually when animals were engaged in the behaviours of interest. Sham stimulation (laser off) was interleaved with the light stimulation (laser on) as an internal control. For optogenetic stimulation, mice were given trains of photostimulation (10-ms pulse, 20 Hz for 10 or 30 s), with at least a three-minute interval between trains. For optogenetic inhibition, 10 s of continuous photostimulation was used. The frequency and duration of photostimulation were controlled using an Accupulse Generator (World Precision Instruments) or an Isolated Pulse Stimulator (A-M Systems).

Urine presentation with optogenetic manipulation.

For urine presentation experiments (Figs. 3m–o, 4n, p, q, Extended Data Fig. 10e, k, l), subject male mice were introduced into a new cage and allowed to explore for at least five minutes before testing. Group-housed C57BL/6N female mice were used as urine donors. Just before testing, the female mouse was lifted by the cervical region and her genital area was gently wiped with a small piece of nestlet (compressed cotton fibre nesting material), to absorb urine seeping from the ano-genital region. The urine-soaked nestlet was placed in the centre of the cage with the male mouse for two minutes, and then removed from the cage. Urine was presented to each male subject mouse approximately six times, with at least a three-minute interval between presentations. Urine from different female donors was used every time. The experimenter monitored the behaviour and vocalizations of the mice through a computer monitor, and delivered 10-s optogenetic stimulation or inhibition pulses at one to two seconds after the first USV syllable was detected. Light stimulation (laser on) and sham stimulation (laser off, same time period) trials were alternated.

Chemogenetic inhibition.

Mice were injected with hM-4Di-DREADD-mCherry or mCherry (control)-expressing AAVs in MPOA or VMHvl. Behavioural tests were performed on two consecutive days. The number of mice receiving saline or clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) (Enzo Life Sciences) was counterbalanced across the two days. CNO was dissolved in saline. CNO (7.5 mg/kg) or saline (control) was intraperitoneally injected 60 min before behavioural tests.

Dual-site fibre photometry recording.

The fibre photometry setup was constructed as previously described13 with minor modifications. We prepared two sets of light paths (ch1 and ch2, recorded signals were processed by a common real-time processor) to enable measurement of bulk calcium signals in two brain regions simultaneously. MPOA and VMHvl recordings were assigned to ch1 or ch2 randomly. We used 470-nm LEDs (M470F3, Thorlabs, filtered with 470–10-nm bandpass filters FB470–10, Thorlabs) for fluorophore excitation, and 405-nm LEDs for isosbestic excitation (M405FP1, Thorlabs, filtered with 410–10-nm bandpass filters FB410–10, Thorlabs). LEDs were modulated at 208 Hz (470 nm) and 333 Hz (405 nm) for ch1, and 263 Hz (470 nm) and 481 Hz (405 nm) for ch2, and controlled by a real-time processor (RZ5P, Tucker David Technologies) via an LED driver (DC4104, Thorlabs). The emission signal from the isosbestic excitation was used as a reference to control for motion artefacts and photobleaching13,37. LEDs were coupled to a 425-nm longpass dichroic mirror (Thorlabs, DMLP425R) via fibre optic patch cables (diameter 400 μm, N.A., 0.48; Doric lenses). Emitted light was collected via the patch cable, coupled to a 490-nm longpass dichroic mirror (DMLP490R, Thorlabs), filtered (FF01–542/27–25, Semrock), collimated through a focusing lens (F671SMA-405, Thorlabs) and detected by the photodetectors (Model 2151, Newport). Recordings were acquired using Synapse software (Tucker Davis Technologies). Once the patch cables were connected to the optic fibre implants on the head of the mice, the mice were placed in their home cage and allowed to habituate for at least 10 min before starting behavioural test sessions. Male or female intruders were introduced into the home cage in a random order, with a 5–10-min interval between male and female intruder sessions. Typically, a session for encountering male or female intruders lasted 10–20 min. Because MPOA and VMHvl are highly interconnected38,39, fluorescent signals from cells in one nucleus may be contaminated with afferent terminal signals derived from the other. As such interconnections are primarily ipsilateral (Extended Data Fig. 2c–f), and activity in a given nucleus is highly correlated across hemispheres (Extended Data Fig. 2g–i), we avoided this contamination by recoding signals from contralateral MPOA and VMHvl.

Micro-endoscope imaging.

Mice were temporarily head-fixed on a running wheel before imaging sessions, and the head-mounted dummy scope used for habituation was replaced with a micro-endoscope (nVista2 or nVista3, Inscopix). The mice were placed in their home cages and allowed to habituate for at least 10 min before starting behavioural test sessions. Shortly before data acquisition, the imaging parameters were configured using nVista control software (Inscopix). The field of view was cropped to the region encompassing the fluorescent neurons. Ca2+ imaging data were acquired at 15 Hz, 15–20% LED power and 2–3× gain, depending on the brightness of GCaMP expression. A TTL pulse from the sync port of the data acquisition box (DAQ, Inscopix) was used to synchronously trigger StreamPix7 for video recording, and Avisoft-UltraSoundGate for audio recording, via customized MATLAB scripts. Male or female intruders were introduced into the home cage in a random order, with a 5–10-min interval between male and female intruder sessions. Typically, a session for encountering male or female intruders lasted 10–20 min. MPOA and VMHvl imaging was performed in separate mice. Four GCaMP6s AAV-injected mice were used for MPOAESR1 (total of 583 neurons imaged) and VMHvlESR1 (total of 421 neurons imaged) for micro-endoscope imaging analysis, respectively.

Data analysis

Position tracking.

Positions and poses of both resident and intruder mice were estimated on a frame-by-frame basis from top-view video using a Python-based custom deep neural network architecture developed in collaboration with the laboratory of P. Perona at Caltech (details of this system are available from ref. 5). In brief, on each frame of video this system estimates the pose of each mouse in terms of the x–y coordinates of seven anatomically defined key points: the nose, the ears, the back of the neck, the hips and the base of the tail. The pose estimator was trained using manual annotations of anatomical key points in 13,500 frames sampled from 14 h of top-view videos of both unoperated mice and mice implanted with head-mounted cannulas or micro-endoscopes. All videos in the training set were of pairs of mice freely interacting in a standard home cage, and 1/3 of training data was taken from videos in which the resident mouse was implanted with a head-mounted micro-endoscope or fibre photometry device with attached cables. For the purposes of this study, the distance between mice was defined as the distance between the necks of the two mice, as estimated by the automated tracking software5 (‘tracker’). On held-out test data, 95% of neck key-point estimates by the tracker fell within a 0.44-cm radius of human-defined ground truth.

Behaviour annotation.

Behaviour videos (collected at 30 Hz) were first processed using a custom automated behaviour classifier system5 to generate frame-by-frame annotations of attack, mounting and investigation (sniffing) behaviour. Classifier output, videos and spectrograms of recorded audio were then loaded into a custom, MATLAB-based behaviour annotation interface5, and classifier annotations were manually corrected by trained individuals blind to the experimental design, to produce a final set of frame-by-frame annotations of attack, USV+ mounting, USV− mounting, intromission and investigation (sniffing). Only one behavioural label was permitted per frame. USV− mounting was operationally defined as bouts of mounting during which no USV syllables were detected (see ‘USV detection’), in which we define a ‘bout’ of behaviour as a period of consecutive frames that all received positive annotations for that behaviour. In cases in which a USV+ mount transitioned to a USV− mount—for example, during optogenetic manipulation (Fig. 4c–k)—mounting bouts were annotated as USV− mounts beginning 1 s after the last USV syllable. For scoring the latency to the first attack in Fig. 1n, the latency time for the mice that did not show attack within the testing period was calculated as 20 min.

Decoder analysis on behaviour features.

We trained binary decoders to distinguish female- and male-directed mounting, on the basis of features extracted from videos of interacting mice. Fifty-four videos containing female- or male-directed interactions were annotated for USV+ or USV− mounting, on the basis of the presence or absence of USVs in audio recordings during mounting bouts, as outlined in ‘Behaviour annotation’. From these, we extracted a total of 10,005 frames (>5.5 min) of female-directed USV+ mounting across 162 behaviour bouts, and 7,527 frames (>4.1 min) of male-directed USV− mounting across 185 behaviour bouts. We used a custom pose estimation system5 to track seven key points on the bodies of both mice: the nose, ears, base of the neck, hips and the base of the tail. To classify behaviours, we extracted a set of 33 features computed from these pose key points, on the basis of features used in a previously published behaviour classification tool36. These features are defined in Supplementary Table 1. Importantly, features were purposefully selected to exclude measurements related to the size, movements and absolute position of the intruder mouse. This was a critical step, as otherwise our decoders were able to distinguish female- and male-directed mounting for ‘trivial’ reasons, such as the fact that intruder males were larger on average than intruder females, and the fact that intruder males tended to spend more time in the corner rather than the centre of the cage.

For frame-wise classification (Fig. 1b, c), the 33 features in Supplementary Table 1 were computed for each frame of USV+ and USV− mounting (at 30 Hz), and used to train a binary support vector machine (SVM) decoder for mounting type, with decoder performance evaluated using ‘leave-one-out’ cross-validation over the set of 54 behaviour videos. An equal number of USV+ and USV− mounting frames were sampled from each class to generate the training set. For classification based on temporal features (Extended Data Fig. 1e–g), the 33 features in Supplementary Table 1 were computed for every 5th frame (for video framerates of 30 Hz) from three seconds before to one second after the onset of USV+ or USV− mounting (25 time samples per feature per behaviour bout). All (33 × 25 = 825) temporal features were then used to train a binary SVM decoder for mounting type, again using leave-one-out cross-validation across videos. To account for some jitter in the time-course of mount initiation, training and test frames were taken to be the annotated start of mounting, as well as all frames within a ±15-frame (500 ms) window of that start time.

USV detection.

We created a spectrogram of recorded audio using the spectrogram function in MATLAB, with a 1024-point symmetric Hann window and 50% overlap between segments. To remove broad-spectrum background sound caused by the movements of mice in the homecage, we used a previously published multitapering and flattening approach40 with time half-bandwidth product of six, to produce a cleaned spectrogram of the recorded audio. All spectrograms shown in the figures and videos are multitapered and flattened.

To detect USVs from the cleaned audio spectrograms, we used a supervised classifier (a multilayer perceptron) trained with manual annotations of USV syllables from 9 sample recordings totalling 17.3 min recording time, and including 1,663 syllables (26% of frames). As preprocessing before classification, spectrograms were cropped to the 30–125-kHz frequency range, z-scored and down-sampled by a factor of 0.5 in frequency space. To better capture temporal structure in the spectrogram, the mean and s.d. of each frequency bin was computed within a window of 8, 16 and 24 frames (approximately 14, 27 and 41 ms, respectively) around the current frame. Following USV detection, all classifier output was manually validated in a custom MATLAB-based annotation interface5, and false positives and false negatives were corrected.

There were several cases in which BALB/c male intruders emitted USVs during resident–intruder tests. Because C57BL/6N and BALB/c USVs differ in their acoustic features41 (BALB/c USVs syllables are typically in a lower frequency range, and have a simpler structure), their USVs can often be visually distinguished in the spectrograms. When BALB/c USV syllables were clearly distinguishable from C57BL/6N USV syllables, they were removed from analysis. For the USV probability plots (Figs. 3n, 4p, Extended Data Fig. 10e, l), all the stimulation trials from all the tested mice were pooled and plotted with an s.e.m. envelope. USV probability traces were smoothed using a moving average with a 1-s time bin.

Fibre photometry data analysis.

The fibre photometry recordings yielded two signals from each recording region, one at 405 nm (isosbestic Ca2+-independent signal, for motion correction) and the other at 470 nm (Ca2+-dependent signal). First, a least-squares linear fit was applied to the 405-nm signal from each region to align it to the 470-nm signal, yielding a fitted 405-nm signal. The motion-corrected 470-nm signal for each region was obtained as follows: motion-corrected 470-nm signal = (470-nm signal − fitted 405-nm signal)/fitted 405-nm signal. Next, to compare neural activity between MPOA and VMHvl, all the motion-corrected 470-nm traces obtained on a given experimental day from each region (always including both female and male intruder trials) were concatenated into a single trace. Concatenated traces from each region were then scaled from zero to one (scaled fluorescent traces, Fs), with pre-intruder activity (mean activity during 35 to 5 s before first intruder introduction, during which the mouse was in its home cage with no intruder present) set to zero and the maximum value of concatenated traces set to one. For computing peri-event time histograms (PETHs), t = 0 was set to the onset of a behaviour of interest (BOI), and the period from −5 to −3 s of the onset of the BOI was used as ‘pre-behaviour baseline’ period. We computed the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of Fs over a pre-behaviour baseline period. PETH activity is computed as PETH(t) = (Fs(t) − μ)/σ. All PETH traces for a given BOI from each mouse were averaged and a single PETH trace was obtained from each individual mouse. PETH traces presented in the figures show the average across all the recorded mice, except for Extended Data Fig. 4, which shows the average across the BOI bouts from one mouse. Only behaviour bouts that were longer than 0.5 s, and separated by >5 s from the previous BOI bout, were used for PETH analysis. For computing maximum activityPETH (Extended Data Fig. 3b, e, g, j, n, r, v), mean values during the baseline period and the maximum value attained within the interval 0–3 s from the onset of the behaviour were compared. For calculating the area under the curve, the area under the Ca2+-activity curve during the first BOI bout after t = 0 zero was calculated, and divided by the length of the first BOI bout to normalized to bout length. Because the first investigation bouts of each intruder have stronger prolonged calcium signals than all other investigation bouts in both MPOA and VMHvl, we excluded the period within 30 s from the beginning of first investigation from most of the analysis. First investigation bouts were analysed separately from other investigation bouts (Extended Data Fig. 3d, e, i, j).

Micro-endoscope trace extraction.

Imaging frames were spatially downsampled by a factor of two in the x and y dimensions. Frames collected over the course of a single day (always including both female and male intruder trials) were concatenated into a single stack and registered to each other to correct for motion artefacts, using the Inscopix Data Processing software. To extract single cells and their Ca2+-activity traces from the fluorescent imaging frames, we used the constrained non-negative matrix factorization for micro-endoscopic data (CNMF-E)42 algorithm. CNMF-E outputs for putative individual neurons were individually inspected manually, and those that did not appear to correspond to single neurons were discarded.

Traces were normalized to units of σ with respect to the baseline fluorescence of the neuron before the first trial of resident–intruder interactions on a given day of imaging, as previously published6. In brief, for a given neuron with extracted calcium trace F0(t), we computed the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of F0(t) over a ‘baseline’ period of 30 or more seconds during which the mouse was in its home cage with no intruder present. Normalized calcium activity was then computed as F(t) = (F0(t) − μ)/σ.

Detection of sex-preferring neurons.

In Fig. 2f, g, sex-preferring cells are defined as activated at least two s.d. from baseline by one but not the other sex during social interaction6. ‘Other’ includes neurons activated or inhibited by both or neither sexes.

Explained variance in micro-endoscope data.

To calculate the variance in population neuronal activity explained by intruder sex and by mouse behaviour (Fig. 2h), each imaging frame (sampled at 15 Hz) was manually annotated for one of the following behaviours (on the basis of analysis of synchronous video acquired at 30 Hz): attack, USV− mount, USV+ mount, intromission, face-, body- and genital-directed investigation towards male or towards female intruders, approach towards a male or female intruder, and periods of no interaction in the presence of a male or female intruder. We then sampled, for each imaged mouse, an equal number of imaging frames from each of 14 different behavioural conditions (seven male-directed and seven female-directed, selected from the behavioural annotations). The total number of frames sampled varied per imaged mouse, and was set by the behaviour with the fewest imaged frames for that mouse; frames were uniformly sampled in time from the set of frames during which a given behaviour occurred. Having thus defined the set of sampled frames, we constructed for each neuron a 1 × n vector of cell activity F(t) on all frames in the sample set. We regressed the observed activity of all neurons against the sex of the intruder (indicated by a pair of binary vectors) on each of the n frames, and computed the cross-validated error of the fit. We then computed the fraction of variance explained by taking the ratio of the coefficient of determination (R2) of the fit, divided by the coefficient of determination when F(t) was fit by 14 1 × n binary vectors representing the presence or absence of each behavioural condition (that is, the maximum explainable variance given the behaviour of the mouse). After subtracting out the signal accounted for by intruder sex, we regressed the residual activity against the identity of the behaviour expressed for each frame, giving variance explained by the female- and male-directed behaviours. The variance ‘explained by’ intruder sex is simply a correlation, and does not imply that the variance reflects an encoding of intruder sex per se: it may encode sex or some other feature that is tightly correlated with intruder sex (for example, motivation to mount or attack for female versus male intruders, respectively).

Computation of choice probability.

The choice probability of each neuron was computed as in previous work6, which follows its definition in studies of decision-making43. In brief, choice probability estimates the accuracy with which two behavioural conditions can be distinguished given the activity of a single neuron. The choice probability of a given neuron for a pair of behavioural conditions is found by constructing a histogram of the activity of that cell (F(t)) under each of a selected pair of behavioural conditions, and plotting these histograms against each other to generate a ‘receiver operating characteristic’ (ROC) curve. The area under this ROC curve is then computed by integration to generate the choice probability value for each unit with respect to each of the two behavioural conditions. This choice probability value is bounded from 0 to 1, with a choice probability of 0.5 indicating that the activity of the neuron cannot distinguish between the two conditions.

The statistical significance of choice probabilities was determined relative to chance, as in previous work6. For each neuron, we shuffled behavioural bout timings for the two compared conditions, and computed the choice probability for this shuffled data. Shuffling was repeated 100 times for each of the 2 behaviours, from which we calculated the mean and s.d. (σ) of the ‘shuffled’ choice probabilities. We considered as significant any observed choice probabilities >2σ above the shuffled mean, and imposed an additional choice probability threshold >0.7. This means that a neuron with a choice probability of, for example, 0.75 can distinguish between the two behaviours of interest with 75% accuracy, and that the probability of correctly predicting which of the two compared behaviours is occurring is significantly greater than when the activity of the neuron is randomized (shuffled) with respect to the actual behavioural annotation for each imaging frame. In Fig. 2k, l, coloured bars indicate the neurons that show a strong and statistically significant choice probability, and grey bars indicate cells for which choice probability was not significantly higher than chance or choice probability ≤ 0.7 for that neuron.

To more confidently distinguish neural representations of behaviour from representations of intruder sex, we computed the choice probability of USV+ mounting versus female-directed investigation for neurons in MPOA and VMHvl. Because the sex of the intruder during USV+ mounting and female-directed investigation is the same, we infer that neurons showing a ‘preference’ (higher F(t)) for one behaviour over the other are specifically responding to that behaviour, and not to the sex of the intruder. We then repeated this analysis for the same set of neurons on trials with a male intruder, contrasting USV− mounting versus male-directed investigation to identify neurons with a preference for USV− mounting over investigation. The Venn diagrams in Fig. 2m, n then show—for all imaged neurons—what percentage of cells had a statistically significant choice probability (relative to sniff) for USV+ mounting, USV− mounting or both behaviours.

Decoding behaviour from neural activity.

We trained linear binary SVM decoders to discriminate female-directed USV+ and male-directed USV− mounting behaviour from imaged activity of MPOA or VMHvl neurons. Manual annotations of USV+ and USV− mounting bouts were used to provide training labels of behaviour type. To decode mounting type as a function of time (‘time-evolving decoder’) (Fig. 2q, u, Extended Data Fig. 6q, r, u, v), activity F(t) for all imaged cells in a given mouse was divided into 0.4-s bins from 5 s before to 10 s after the onset of mounting. In an effort to remove information about intruder sex from neural activity, for each neuron on each bout we computed the average activity of the cell in a time window from −5 to −3 s of the initiation of mounting, and subtracted this average from F(t) of that cell in all time bins of the bout. For each time bin, we then trained an SVM decoder to discriminate USV+ from USV− mounting bouts from the activity of neurons in that bin, using leave-one-out cross-validation across bouts to evaluate decoder accuracy.

Bar graphs of decoder accuracy (Fig. 2r, v Extended Data Fig. 6s, t, w, x) were generated using a ‘frame-wise’ decoder trained to discriminate USV+ and USV− mounting from imaged activity on individual frames of a behaviour (sampled at 15 Hz). Following baseline subtraction (performed as for the time-evolving decoder), USV+ and USV− mounting bouts were divided into ‘trials’, by first merging all bouts of a given behaviour that were separated by less than five seconds (from the end of bout A to the start of bout B). Frames from single- or multi-bout trials were then used to train a linear binary SVM decoder, using leave-one-out cross-validation across intruder mice.

For both decoders, equal numbers of USV+ and USV− bouts (time-evolving decoder) or frames (frame-wise decoder) were used during decoder training, to ensure chance decoder performance of 50%. ‘Shuffled’ decoder data were generated by training the decoder on the same neural data, but with USV+ and USV− behaviour annotations randomly assigned to each behaviour bout. Decoding was repeated 20 times for each intruder and each imaged mouse, and decoder performance reported as the average accuracy across imaged mice. For significance testing, the mean accuracy of the decoder trained on shuffled data was computed across mice, and shuffling was repeated 1,000 times. Significance was determined across imaged mice using the Mann–Whitney U test between the mean accuracy of the decoders trained on real versus shuffled data.

Data display.

In all the bar graphs, data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. In all the box-and-whisker plots, centre lines indicate medians, box edges represent the interquartile range and whiskers denote minimal and maximal values.

Statistical analyses.

Data were processed and analysed using MATLAB and GraphPad PRISM 8 (GraphPad Software). The sample sizes were chosen on the basis of common practice in animal behaviour experiments. All data were analysed with two-tailed non-parametric tests. In the experiments with paired samples, we used the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test or Friedman test. In the experiments with non-paired samples, we used the Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test. All multiple comparisons were corrected with Dunn’s multiple comparisons correction. Binary data were analysed with a Fisher’s exact test. The significance threshold was held at α = 0.05, two-tailed (not significant (NS), P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). Full statistical analyses corresponding to each dataset are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

The data that support the finding of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

The custom codes used for pose tracking and behaviour annotation of the mice5 can be found at GitHub (https://neuroethology.github.io/MARS/). The other code that supports the finding of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Additional information for resident–intruder assay with female or male intruders.

a, An example of detected resident (green) and intruder (red) key points used for mouse pose estimation (top) and example diagram of the resident ‘axis ratio’ feature (bottom). b, Histograms of values of four relevant mouse pose features during bouts of female- or male-directed mounting. Pose features extracted from mount video frames only are highly overlapping for male- versus female-directed mounts. c, Distribution of mounting bout length. d, Distribution of time spent in close proximity to the intruder before initiation of mounting. e–g, Decoding intruder sex from female- versus male-directed mounting from video frames spanning 3 s before to 1 s after mount onset. e, Projection of mouse pose features from mounting bouts onto the maximally discriminating dimension of the decoder. f, Decoder accuracy compared with shuffled data. Fifty-four behaviour sessions, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, ****P < 0.0001. g, Values of four mouse pose features relative to onset of female- or male-directed mounting (top row), the temporal filter on each feature learned by the SVM decoder (middle row), and histograms of filter output for tested frames of female- versus male-directed interactions, showing separation of feature values (bottom row). a.u., arbitrary units. h, i, Details of the behaviours of different resident mice towards male intruder across three days, corresponding to Fig. 1g. h, Number of mice assigned to each behaviour category. i, Visualization of behaviour changes across three days. Different coloured circles indicate different resident mice. Overall, behaviours for each mouse changed from lower intensity categories (less aggressive) to higher intensity categories (more aggressive), with repeated social experience. j, Behaviour rasters towards male intruders across three days from three mice. Bottom row indicates extracted USV− mount bouts from day 1 to show that most USV− mounts occur in the early phase of a male–male social interaction. k, Two alternative models for encoding of male- versus female- directed mounting in the hypothalamus. In model 1, the two forms of mounting share a common hypothalamic ‘mounting control centre’; in model 2, the two forms of mounting use distinct neural substrates. Circles, squares and triangles are abstractions representing different cell populations, and do not correspond to specific nuclei or circuits. Data are mean ± s.e.m. (Supplementary Table 2).

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Control experiment data for dual-site fibre photometry.

a, Schematic of dual-site fibre photometry setup. Calcium signals are recorded simultaneously from contralateral MPOA and VMHvl using Esr1cre male mice. b, Representative scaled calcium signals from MPOAESR1 and VMHvlESR1 neurons after exposure to female (top) and male (bottom) intruders. Vertical shading indicates bouts of annotated social behaviour listed and colour-coded at right. Downward arrows, intruder introduction; upward arrows, intruder removal. c–f, Representative data from mice injected with GCaMP6s AAV only in MPOA (c, d), or in VMHvl (e, f) and recorded from both two areas. c, e, Representative GCaMP6s expression and optic fibre tract. Top, MPOA; bottom, VMHvl, Scale bars, 100 μm. n = 2 each. AC, anterior commissure; f, fornix; BNSTpr, principal division of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; vBNST, ventral BNST; fiber, optic fibre tract. d, f, Representative GCaMP6s traces from MPOAESR1 and VMHvlESR1 neurons with female and male intruders. Vertical shading indicates bouts of annotated social behaviour listed and colour-coded at right. Data are presented as raw motion corrected 470-nm traces. Non-injected sites (VMHvl in c, MPOA in e) had few GCaMP-positive fibres from contralateral injection sites (c, e) and did not show detectable Ca2+ signal changes (flat lines in d, f). g–j, Representative data from recording bilateral VMHvlESR1 neurons. n = 2. g, Schematic of fibre photometry recording from bilateral VMHvl. h, Ca2+ traces from female and male trials. Ca2+ traces in right and left hemispheres are highly correlated. i, j, Distribution of scaled activity in right (x axis) versus left (y axis) VMHvlESR1 neurons across entire trials with female (i) and male (j) intruders. Activity was fitted to y = ax + b (red line) using 1-kHz sampling traces and scatter plots display downsampled (30 Hz) time points. R2, coefficient of determination. k, l, Distribution of scaled activity in MPOAESR1 (x axis) versus VMHvlESR1 (y axis) neurons across entire trials with female (k) and male (l) intruders from the traces in b. MPOAESR1 and VMHvlESR1 neural activities are less correlated than bilateral VMHvlESR1 neural activities.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Dual-site fibre photometry recording during social interaction.

a–j, Average calcium signals in MPOAESR1 and in VMHvlESR1 neurons aligned to social investigation onset of female (a–e) and male (f–j) intruders. n = 10. First investigation bouts of each intruder have stronger calcium signals than all other investigation bouts and were analysed separately (d, e, i, j). a, f, PETH of scaled neural activity normalized to pre-behaviour period. b, g, Maximum PETH signal during 0 to 3 s from investigation onset (shaded grey area in a, f), compared with mean activity during pre-behaviour period (−5 to −3 s). b, ****P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0025; g, *P = 0.0105, ****P < 0.0001. c, h, Integrated activity during investigation. c, **P = 0.0039; h, *P = 0.0273. a.u., arbitrary units. d, e, i, j, Average calcium signals during first investigation of each intruder versus all other investigation bouts towards female (d, e) and male (i, j) intruders. d, i, PETH of scaled neural activity. e, j, Maximum PETH signal during 0 to 3 s from first investigation onset. e, j, **P = 0.002. k, l, Average calcium signals during social investigation in each region. k, PETH of scaled neural activity in MPOAESR1 and VMHvlESR1. n = 10. Traces were reproduced and rescaled from data in a, f for comparative purposes. l, Integrated activity during investigation. **P = 0.0098 (MPOA), 0.0059 (VMHvl). m–x, Average calcium signals during USV+ mounts towards female intruders (m–p, n = 10), USV− mounts towards male intruders (q–t, n = 6) or attack towards male intruders (u–x, n = 7). m, q, u, PETH of average scaled neural activity. n, r, v, Maximum scaled activity during 0–3 s from behaviour onset. n, ****P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0014; r, *P = 0.0358, ***P = 0.0009; v, *P = 0.0104, ***P = 0.0007. o, s, w, Representative PETH traces for each behaviour. Coloured shading marks behavioural episodes. p, t, x, Integrated activity in during behaviours. p, **P = 0.002; x, **P = 0.0469. m and q traces were reproduced and rescaled from data in Fig. 2c. y, Average calcium signals during USV+ mount, USV− mount and attack. y, PETH of scaled activity in MPOAESR1 and VMHvlESR1neurons. USV+ mount, n = 10; USV− mount, n = 6; attack, n = 7. Traces were reproduced and rescaled from data in m, q and u. z, Integrated activity during each behaviour. **P = 0.0092, 0.0097, 0.0097 (left to right). b, e, g, j, l, n, r, v, z, Kruskal–Wallis test; c, h, p, t, x, Wilcoxon test. Data are mean ± s.e.m. except for box plots (see Fig. 2 legend). All statistical tests are two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons when necessary (Supplementary Table 2).

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Neural activity patterns in rare mice that exhibit USV+ mounting towards male intruders resemble those observed during USV+ mount towards female intruders.

a–e, Calcium activity and USV data from a sexually and socially experienced mouse (no. 629) that showed USV+ mounting towards both female and male intruders. Female, 21 bouts; male, 30 bouts. a, b, PETH traces aligned at onset of USV+ mount towards female (a) or male (b) intruders. c, Integrated activity during mounting bouts. ****P < 0.0001. d, e, Quantification of USVs from mouse no. 629 towards female or male intruders. d, Distribution of USVs aligned at onset of USV+ mount. e, Number of USV syllables during 0 to 5 s from onset of USV+ mount. This mouse did not display any attack behaviour towards male mice, but preferred females to males in a triadic interaction test (Supplementary Note 2). f–k, Calcium activity data from one mouse (no. 634) which showed USV+ mounting towards males when sexually and socially naive, and later USV− mounting after it obtained sexual and social experience. f, g, PETH traces from naive mouse aligned at onset of USV+ mount. h, Integrated activity during mounting bouts from data in f, g. Female, 27 bouts; male, 9 bouts, ****P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0039. i, j, PETH traces from the same mouse after social and sexual experience, aligned at onset of USV+ mounting towards female or USV− mounting towards male intruders. k, Integrated activity during mounting bouts from traces in i, j. Female, 107 bouts; male, 7 bouts, ****P < 0.0001. c, h, k, Wilcoxon test; e, Mann–Whitney U test. Data are mean ± s.e.m. except for box plots (see Fig. 2 legend). All statistical tests are two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons when necessary (Supplementary Table 2).

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Correlation of ESR1+ neural activity during male-versus female-, male-versus male-, or female- versus female-directed behaviours in MPOA and VMHvl.

a–l, Average calcium response per neuron in MPOAESR1 (a, b, e, f, i, j) or VMHvlESR1 (c, d, g, h, k, l) populations during female-directed behaviours (USV+ mounting or investigation, y axis) versus male-directed behaviours (USV− mounting or investigation, x axis) (a–h), female-directed USV+ mounting (y axis) versus investigation (x axis) (i, k) or male-directed USV− mounting (y axis) versus investigation (x-axis) (j, k), compared to pre-intruder baseline period. Coloured points indicate cells with >2σ, compared to pre-intruder baseline period. Red lines, y = x. R2, coefficient of determination. Dashed lines, 2σ. m–p, Proportion of cells excited (>2σ) during female- (m, o) or male- (n, p) directed behaviours. The correlations of the neural activity during the behaviours directed towards the same sex (i–l) are higher than the correlations during the behaviours directed towards the different sex (a–h).

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Neuronal population representations of social behaviours in MPOA and VMHvl.

a, b, Representative calcium activity rasters of MPOAESR1 (a) and VMHvlESR1 (b) neurons during social interaction with a female (left) or male (right) intruder, sorted by mean activity level during the displayed period. Behaviours of the resident mice are indicated above the neural activity rasters. Arrows, intruder introduction. c–f, Response strength of behaviour-tuned populations, during their preferred behaviour (coloured bars) and non-preferred behaviour (grey bars). Behaviour-tuned populations are defined by choice probability for female-directed mount versus investigation (c, d, from Fig. 2k, l, left) and for male-directed mount versus investigation (e, f, from Fig. 2k, l, right). c, n = 41 (inv-tuned), 53 (mount-tuned); d, n = 61 (inv), 12 (mount); e, n = 38 (inv), 63 (mount); f, n = 21 (inv), 24 (mount), ****P < 0.0001, ***P = 0.0005. g–n, Average calcium response per neuron during female-directed USV+ mounting (y axis) versus male attack (x axis) (g–j), and male-directed USV− mounting (y axis) versus male attack (x axis) (k–n), relative to activity immediately before behaviour initiation. g, h, k, l, Scatter plots. i, j, m, n, Proportion of cells excited (>2σ) during each behaviour. o, p, Average response strength of mount responsive neurons (>2σ relative to activity immediately before mount initiation). USV+ mount-responsive neurons (green + grey dots in Fig. 2o, s), n = 68 (MPOA), 8 (VMHvl); USV− mount-responsive (blue + grey dots in Fig. 2o, s), n = 35 (MPOA), 22 (VMHvl), ***P = 0.0001. q–x, Accuracy of time-evolving (q, r, u, v) or frame-wise (s, t, w, x) decoders predicting USV+ mounting from attack (q–t) and USV− mounting from attack (u–x), trained on neural activity. n = 4, ****P < 0.0001, *P = 0.026. c–f, Wilcoxon test; o, p, s, t, w, x, Mann–Whitney U test. Data are mean ± s.e.m. except for box plots (see Fig. 2 legend). All statistical tests are two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons when necessary (Supplementary Table 2).

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Stimulation of MPOAESR1∩VGAT neurons triggers mounting and USVs towards male and female intruders.

a–i, Quantification of behaviour parameters towards male intruders (a–h) or under solitary conditions (i) with different laser intensities. a–f, h, i, ChR2 with intensity A, B, off, n = 7; C, n = 6; control, n = 7; g, ChR2 with intensity B and off, n = 6; A and C, n = 6; control, on n = 5, off n = 4. Data with intensity B (0.5–1.5 mW) are reproduced from Fig. 3 for comparative purposes. b, Left to right, *P = 0.0418, ***P = 0.0009, 0.0006. c, ***P = 0.0004, **P = 0.001. d, **P = 0.0012, 0.0031. e, **P = 0.0025, 0.0024. f, **P = 0.0027, **P = 0.0179. g, **P = 0.0014, 0.002. h, *P = 0.0102, 0.0112. i, **P = 0.0096, 0.0045. j, Representative behaviour raster plots towards male intruders from ChR2 and control mice without (top) and with (bottom) photostimulation with laser intensity B (0.5–1.5 mW). k–q, Quantification of behaviour parameters towards female intruders with laser intensity B (0.5–1.5 mW). ChR2, n = 6; control, n = 7. l, *P = 0.0127. m, **P = 0.0034. o, **P = 0.0025. p, ***P = 0.0001. b–i (ChR2), l–p, Kruskal–Wallis test; b–i (control), Wilcoxon test; k, Fisher’s test. Data are mean ± s.e.m. except for box plots (see Fig. 2 legend). All statistical tests are two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons when necessary (Supplementary Table 2).

Extended Data Fig. 8 |. Comparison between features of naturally occurring and optogenetically evoked USVs.