Abstract

Background

Early administration of antibiotics and wound coverage have been shown to decrease the deep infection risk in all patients with Type 3 open tibia fractures. However, it is unknown whether early antibiotic administration decreases infection risk in patients with Types 1, 2, and 3A open tibia fractures treated with primary wound closure.

Questions/purposes

(1) Does decreased time to administration of the first dose of antibiotics decrease the deep infection risk in all open tibia fractures with primary wound closure? (2) What patient demographic factors are associated with an increased deep infection risk in Types 1, 2, and 3A open tibia fractures with primary wound closure?

Methods

We identified 361 open tibia fractures over a 5-year period at a Level I regional trauma center that receives direct admissions and transfers from other hospitals which produces large variation in the timing of antibiotic administration. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 years, had associated plafond or plateau fractures, associated with compartment syndrome, had a delay of more than 24 hours from injury to the operating room, underwent repeat débridement procedures, had incomplete data, and were treated with negative-pressure dressings or other adjunct wound management strategies that would preclude primary closure. Primary closure was at the descretion of the treating surgeon. We included patients with a minimum follow-up of 6 weeks with assessment at 6 months and 12 months. One hundred forty-three patients with were included in the analysis. Our primary endpoint was deep infection as defined by the CDC criteria. We obtained chronological data, including the time to the first dose of antibiotics and time to surgical débridement from ambulance run sheets, transferring hospital records, and the electronic medical record to answer our first question. We considered demographics, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, mechanism of injury, smoking status, presence of diabetes, and Injury Severity Score in our analysis of other factors. These were compared using one-way ANOVA, chi-square, or Fisher’s exact tests. Binary regression was used to to ascertain whether any factors were associated with postoperative infection. Receiver operator characteristic curves were used to identify threshold values.

Results

Increased time to first administration of antibiotics was associated with an increased infection risk in patients who were treated with primary wound closure; the greatest inflection point on that analysis occurred at 150 minutes, when the increased infection risk was greatest (20% [8 of 41] versus 4% [3 of 86]; odds ratio 5.6 [95% CI 1.4 to 22.2]; p = 0.01). After controlling for potential confounding variables like age, diabetes and smoking status, none of the variables we evaluated were associated with an increased risk of deep infection in Type 1, 2, and 3A open tibia fractures in patients treated with primary wound closure.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that in open tibia fractures, which receive timely antibiotic administration, primary wound closure is associated with a decreased infection risk. We recognize that more definitive studies need to be performed to confirm these findings and confirm feasibility of early antibiotic administration, especially in the pre-hospital context.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Tibia fractures are one of the most common long bone fractures, and approximately 25% of them are open [6]. The sequelae of open fractures can be debilitating for patients and a challenge for orthopaedic surgeons. Negative outcomes such as infection remain common [4, 8, 10, 26].

Contemporary guidelines for open-fracture management focus on timely, adequate surgical débridement, administration of antibiotics, and early fracture stabilization [11, 20]. Despite the high infection rate, wound closure is recommended as early as possible [11, 20]. Primary wound closure in open tibias has been shown to be associated with a decreased infection risk and less need for secondary procedures [3, 13, 14, 21, 23, 28]. Administration of prophylactic antibiotics is paramount in preventing infection, with current recommendations stating antibiotics should be started “as soon as possible” [12, 21, 28].

Although guidelines suggest prophylactic antibiotics should be administered, little evidence exists guiding the surgeon on appropriate antibiotic timing. Early work suggested antibiotics within 3 hours of injury decreased infection risk (4.7% versus 7.4%) in open fractures [21]. Other studies were unable to find an association between antibiotic timing and infection [1, 9, 16, 24]. More recently, a retrospective review of 137 open tibia fractures demonstrated a decreased infection risk with antibiotic administration earlier than 66 minutes in open tibia fractures [15]. However, this study included Type 3B and 3C tibia injuries with variable and delayed soft-tissue coverage, which introduced confounding factors that made the results difficult to interpret and not applicable to less severe injuries. It is unknown whether early antibiotic administration is associated with decreased infection risk in a more homogenous group of less severe open injuries treated with immediate wound closure.

Therefore, we asked: (1) Does decreased time to administration of the first dose of antibiotics decrease the deep infection risk in all open tibia fractures with primary wound closure? (2) What patient demographic factors are associated with an increased deep infection risk in Types 1, 2, and 3A open tibia fractures with primary wound closure?

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

After institutional review board approval, we retrospectively reviewed all patients with open tibial shaft fractures resulting from moderate to high-energy mechanisms who were treated with primary wound closure at the University of Kentucky Chandler Medical Center, a Level 1 regional trauma center, from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2015. Our center has a large catchment area, which includes direct admissions from remote areas as well as transfers from peripheral institutions. This creates variability of timing of antibiotic administration from the time of injury that allowed us to investigate antibiotic timing.

Participants

Over the period, we identified 361 open tibia fractures. Two orthopaedic trauma surgeons (DAZ, CBH) identified 267 open tibial shaft fractures radiographically classified as AO/OTA 42A-C injuries [19] for record review. Discrepancies were moderated by a more senior fellowship-trained orthopaedic trauma surgeon (PEM). We excluded patients if they were younger than 18 years, underwent repeat débridements, had compartment syndrome treated with fasciotomy, or had a fracture that met the criteria for Gustilo-Anderson Type 3B or 3C (n = 89). After reviewing the patients’ records, we further excluded patients with adjunct wound management strategies including delayed coverage, negative-pressure dressings, or local eluting antibiotics (n = 24); those with a delay to débridement of more than 24 hours (n = 1); and those with incomplete follow-up, defined as less than 6 weeks from débridement (n = 10).

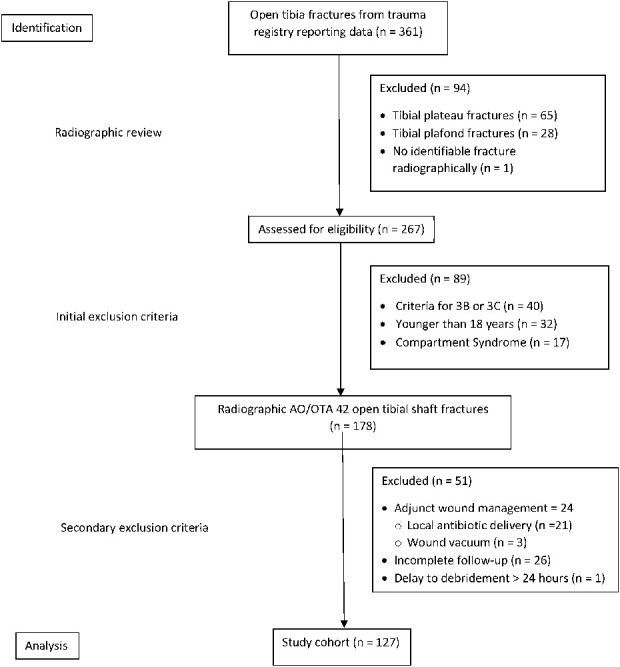

The final cohort included 142 patients (108 men; 35 women; 80% inclusion proportion) with 143 fractures (Fig 1).

Fig. 1.

STROBE patient flow diagram outlining the inclusion/exclusion of patients for this analysis.

Most patients (88% [125 of 142]) were treated with dèbridement and fixation at the index procedure. In all, 12% (17 of 142) of patients underwent staged external fixation and returned at a later date for definitive fixation. Most patients received intramedullary fixation as their definitive fixation (88% [126 of 143]), followed by plates and screws (11% [16 of 143]), and external fixation (0.7% [1 of 143]).

Description of Experiment, Treatment, or Surgery

All patients were treated using our institutional protocol. Our institutional standardized antibiotic prophylaxis regimen follows the East Practice Management Guidelines [12], which suggest antibiotic treatment as soon as possible with first-generation cephalosporin or clindamycin for patients with Types 1 and 2 fractures who have an allergy to penicillin. The addition of aminoglycosides is reserved for additional gram-negative coverage in patients with Type 3 or more severe injuries at the discretion of the treating surgeon. Penicillin is added if a patient has an organic contaminant. Patients were treated with either nail or plate constructs for definitive fixation. Patients in extremis were temporized with external fixation after débridement and primary wound closure until definitive treatment.

At our institution, the timing of antibiotic administration is determined upon identification of open fractures, which occurs as soon as reasonably possible after admission. However, due to the nature of our facility (regional trauma center), we often receive patients that are from remote areas or transfers from other institutions. Thus there is variety in timing of antibiotic delivery secondary to factors outside of our institution.

At our institution, open fractures are primarily closed unless the soft tissues are not amenable (such as those that need flap coverage) or rarely if the degree of contamination is so great that complete dèbridement cannot be accomplished at the index procedure. This is at the descretion of the treating surgeon. Postoperative antibiotics are continued for 24 hours after dèbridement.

Outcome Assessment

Our primary outcome of interest was deep surgical-site infection, defined by the pre-2016 CDC criteria for deep infection with unplanned return to the operating room regardless of culture positivity if the patient met at least one of the CDC criteria for deep infection [18]. Superficial infections were not considered in the analysis. To answer our first question, we obtained chronologic data, including the time from injury to the first dose of antibiotics and time to surgical débridement from ambulance run sheets, transferring hospital records, and the electronic medical record. In most transfer cases, patients received a dose of intravenous antibiotics from an outside hospital before being transferred to our trauma center. We obtained antibiotic timing from the transfer documentation in these cases. In patients with multiple antibiotic doses, the earliest documented time was recorded. All patients received routine postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis.

To answer our second question, we obtained the following demographic data from the medical record: American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification [7] based on institutional trauma reporting data, the mechanism of injury, smoking status, presence of diabetes, type of antibiotic received, and Injury Severity Score (ISS) [2]. The Gustilo-Anderson type was obtained from the patient’s operative report. The most common Gustil-Anderson type was type 2 (53% [62 of 127] followed by Type 3A (24% [30 of 127]) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association of comorbidities, injury severity, and fixation type with deep infections

| Variable | Category | Infection (n = 11) | No infection (n = 116) | p value |

| Age in years (mean) | 37 | 41 | 0.35 | |

| Sex, n female (%) | 27 (3) | 27 (31) | 0.99 | |

| ASA status, n (%) | 0.12 | |||

| 1 | 0 (0) | 8 (9) | ||

| 2 | 27 (3) | 59 (68) | ||

| 3 | 73 (8) | 30 (35) | ||

| 4 | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | ||

| 5 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | ||

| Smoking, n (%) | 46 (5) | 37 (43) | 0.75 | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 9 (1) | 9 (10) | 0.99 | |

| BMI in kg/m2, mean | 32 | 28 | 0.28 | |

| Injury Severity Score, mean | 16 | 12 | 0.33 | |

| Type of definitive fixation, n (%) | Nail | 64 (7) | 91 (105) | 0.03 |

| Plate/screw | 27 (3) | 8 (9) | ||

| Time to operating room in hours, mean | 10 | 10 | 0.81 | |

| Gustilo-Anderson Type, n (%) | 0.005 | |||

| 1 | 0.0 (0) | 30 (35) | ||

| 2 | 55 (6) | 48 (56) | ||

| 3 | 45 (5) | 22 (25) |

Statistical Analysis and Follow-up

We compared data using one-way ANOVA, chi-square, or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. We used binary logistic regression (forward method, Wald, p < 0.05 for inclusion) to determine whether a model could be created that would ascertain if any factors were associated with postoperative infection. Variables included in the analysis were sex, ASA grade, age, mechanism of injury, ISS, time to antibiotic administration, smoking status, presence of diabetes, BMI, Gustilo-Anderson classification type, time to the operating room, definitive fixation method, and drain placement. At each step, variables with p ≥ 0.05 were excluded. After univariate analysis, we advanced Gustilo-Anderson type and time to multivariate analysis. Receiver operator characteristic curves were then used to identify potential threshold values for continuous variables (such as, time to antibiotic administration)

Follow-up

For the purpose of analysis, we selected 6 weeks as our primary follow-up point due to high rates of loss-to-follow-up in the trauma population. Inclusion of only longer follow-up could result in a larger effect size, resulting in a skewed incidence of infection. To assess if a selection bias associated with differential follow-up between our primary outcome groups (early versus late antibiotic administration) was present, we compared rates of follow-up/primary outcome of SSI in patients with 6 weeks, 6 months and 1 year of follow-up.

Of the patients, 89% (127 of 142) had 6-weeks of follow-up, 79% (112 of 142) had at least 3 months of follow-up, 56% (80 of 142) had at least 6 months of follow-up, and 35% (50 of 142) had at least 12 months of follow-up. The mean length of follow-up was 68 weeks (95% CI 55.0 to 80.9).

Results

Time to Antibiotic Administration and Infection Risk

Increased time to first administration of antibiotics was associated with an increased risk of infection in patients with open tibia fractures who were treated with primary wound closure. We identified a threshold for antibiotic administration of 154 minutes, which we modified to 150 minutes to be in line with a more common time point (2.5 hours). Receiving antibiotics after this time point was associated with an increased risk of infection (3% [3 of 86] versus 20% [8 of 41], OR 5.6 [95% CI 1 to 22]; p = 0.01]. The sensitivity of the 154-minute and 150-minute thresholds were identical (73%), and using the 150-minute threshold resulted in a very small reduction in specificity (74% versus 75%) (see Table 1; Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A438). This finding was consisent at all follow-up time points assessed (see Table 2; Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A439).

Other Factors Associated with Infection

After controlling for potential confounding variables such as ASA status, smoking, diabetes and timing of fixation, none of the variables we evaluated were associated with an increased risk of deep infection in open tibia fractures treated with primary closure. Although fracture type was associated with infection risk on univariate analysis, after controlling for the timing of antibiotics, it was not associated with increased infection risk.

Discussion

Open tibia fractures are associated with an increased infection risk, which can have a large impact on patients. Prophylactic antibiotic administration is paramount in the prevention of infection. However, there is conflicting evidence on whether the timing of antibiotic administration plays a role in infection risk. In our study of open tibia shaft fractures, antibiotic administration within 2.5 hours of injury was associated with a decreased risk of deep infection (OR 5.6 [95% CI 1.4 to 22.2]). This suggests that antibiotic administration as soon as possible is a reasonable goal, especially considering that extrication and transport time via emergency medical services (EMS) has the potential to increase the time to antibiotic administration. Centers that coordinate care for a large region may benefit from a systems protocol that involves antibiotic administration by EMS in the field to minimize this time.

Limitations

Trauma can be associated with poor follow-up, and our cohort was no exception. There is an inherent transfer bias as patients are lost to follow-up over time (for example, patients with poor outcomes such as infection are likely to follow-up elsewhere). Thus, we cannot completely account for these patients in our analysis. Most fracture-related infections typically occur within 3 months to 6 months after injury, for which our study had reasonably high rate of follow-up at 3 months (79%), although this did decrease at 6 months (57%) [25]. However, in our cohort, the proportion lost to follow-up at each time point assesed (6 weeks, 3 months, 1 year) did not differ between groups (early versus late antibiotics), and the association between antibiotic timing and infection risk remained consistent. This helps mitigate the effects of this bias and strengthens our findings.

As a single-center study, our analysis is subject to a sparse data bias given the available number of patients and the event rate of infection. There were a relatively small number of infections in the current study (n = 11). This raises concern for data fragility, in that a reduction of four infections in the late antibiotic group or an increase of more than four infections in the early antibiotic group could negate the current findings. With an OR of 7.7 at 12-months and CIs ranging from 1.7 to 35, the current results would be appear to be robust in comparison if we had found an OR closer to 1 (that is, 1 to 29). A larger cohort will likely confirm these findings.

Patient factors that are typically associated with increased rate of complications (such as, diabetes, smoking status, fracture type) were not found to be associated with infection in the current study. We caution the reader about drawing any conclusions from this finding because it is likely due to a smaller number of infections in the current study and our study being underpowered to detect difference in these groups. Interestingly, Gustilo-Anderson fracture type was not associated with an increased infection risk. This may be related to the number of patients or representative of our chosen sample. In the current design, we excluded open fractures that underwent vessel repair for limb salvage and those needing soft-tissue coverage to limit variability. This may play a role in our inability to detect an increased infection risk with Gustilo-Anderson type.

Although our institution has a standardized protocol for antibiotic administration, variability in choice of antibiotics (such as, clindamycin for cephalosporin allergy) may play a role in infection risk. We would also expect variability within those patients who were transferred from outside facilities. Our study population was not large enough to assess this difference, which is likely small given the similarity of antibiotic profile in typically used antibiotics. Thus, this would be unlikely to change our findings that early antibiotic administration decreases the infection risk.

Additionally, we are limited by the retrospective nature of this design. We are reliant on several sources that are not entirely accurate or complete. However, with the advent of the electronic medical record, our main indepedant variable (the timing of antibiotic adminstration) was likely reasonably well recorded as was the need for surgery for deep infection. Other factors such as comorbidities and patient characteristics would be more likely to be inaccurate and this may reflect our inability to detect a difference in these groups.

Time to Antibiotic Administration and Infection Risk

We found that a delay in administration of the first dose of antibiotics was associated with an increased risk of deep infection in patients with Type 1, 2, and 3A open tibia fractures who were treated with primary wound closure, and that this risk became especially severe if the delay was greater than 2.5 hours. The current study supports a recent report that antibiotic administion earlier than 66 minutes is associated with a decreased infection risk in high-energy open tibia fractures [15]. However, our study sample included open tibia fractures that did not need soft tissue coverage or vascular repair and were primarily closed. This minimizes the influence of other factors (such as the timing of flap coverage and injury severity), which may play a role in infection risk. This may explain why we found 2.5 hours as the inflection point in comparison to 66 minutes found in the prior study. Likewise, fractures which are primarily closed are likely to be less severe with regard to soft tissue trauma, and may have more tolerance of antibiotic timing. We believe that our findings complement the data of Lack et al. [15] in their series. Others have suggested that antibiotic timing does not play a role, but many of the series are reflective of a large variability of fracture types and extremity treated, which can drastically change results [1, 9, 16, 26]. In these studies, open tibia fractures were associated with a much higher infection risk when compared with upper extremity fractures, introducing variability which may explain their findings. Our series minimized these differences by assessing only Type 1, 2, 3A fractures in tibias that were primarily closed.

Our ability to detect a difference in infection risk may be related to regional variations in trauma care. More-urban centers and well-organized trauma systems may be more proficient at triaging and definitively directing patient care, including antibiotic administration. Our center includes a very large rural area, and coordination of care is not centralized. Delayed treatment is common, with patients often having delayed transport or prolonged times out in the field before emergency services are activated. This may explain why some reports, including ours, are able to demonstrate an association.

The institution of early antibiotic therapy should be easily implemented with changes in systems protocols. For patients who are being transported from remote regions or with prolonged extrication, implementation of early antibiotics is associated with challenges. Pre-hospital antibiotic administration is used in the military based on strong support from a case series [5]. In the civilian sector, this would necessitate the following: additional training of EMS personnel, making the medications available, and the assessment of the associated risks of antibiotic administration. First-generation cephalosporins would be safe for most patients; the potential allergic cross-reactivity of most first-generation cephalosporins in patients who are allergic to penicillin is less than 0.5% [17, 22]. However, for protocols which include aminoglycosides, risks for nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity, particularly in elderly people who sustain trauma, may preclude common dosing [27]. Future observational and randomized prospective designs could determine efficacy and feasibility.

Other Factors Associated with Infection

After controlling for multiple factors including diabetes, smoking and BMI, we found no demographic features that were associated with a greater deep infection risk in patients with Types 1, 2, and 3A open tibia fractures. Likewise, we did not find an association with Gustilo-Anderson type, which is commonly reported [4, 8, 11, 13]. However, this may be due to the exclusion of type 3B/3C fractures, which can have substantial variation within their care [16, 19] and substantially increase infection risk. Due to the small number of infections in this current study, we would caution against making conclusions from these findings.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that early antibiotic administration can decrease the infection risk of open tibia fractures that are closed primarily. Other factors such as fracture type do not appear to influence infection risk, but this finding may be related to our sample size. Early antibiotic administration may be accomplished by changes in hospital-based protocols or antibiotic delivery through EMS. Further prospective research can help determine the feasibility and effectiveness of these strategies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he has no commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA.

References

- 1.Al-Arabi YB, Nader M, Hamidian-Jahromi AR, Woods DA. The effect of the timing of antibiotics and surgical treatment on infection rates in open long-bone fractures: a 9-year prospective study from a district general hospital [published correction appears in Injury. 2008;39:381 Nader, Michael [corrected to Nader, Maher]. Injury. 2007;38:900-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W, Jr, Long WB. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14:187-196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson DR, Riggins RS, Lawrence RM, Hoeprich PD, Huston AC, Harrison JA. Treatment of open fractures: a prospective study. J Trauma. 1983;23:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Kellam JF, Burgess AR, Webb LX, Swiontkowski MF, Sanders RW, Jones AL, McAndrew MP, Patterson BM, McCarthy ML, Travison TG, Castillo RC. An analysis of outcomes of reconstruction or amputation after leg-threatening injuries. N Engl J Med . 2002;347:1924-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler F, O’Connor K. Antibiotics in tactical combat casualty care 2002. Mil Med. 2003;168:911-914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Court-Brown CM, Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: A review. Injury. 2006;37:691-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle DJ, Goyal A, Bansal P, Garmon EH. American Society of Anesthesiologists Classification (ASA Class) [Updated 2020 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441940/. Accessed July 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards CC, Simmons SC, Browner BD, Weigel MC. Severe open tibial fractures. Results treating 202 injuries with external fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988:98-115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enninghorst N, McDougall D, Hunt JJ, Balogh ZJ. Open tibia fractures: timely debridement leaves injury severity as the only determinant of poor outcome. J Trauma. 2011;70:352-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giovannini F, de Palma L, Panfighi A, Marinelli M. Intramedullary nailing versus external fixation in Gustilo type III open tibial shaft fractures: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2016;11:1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halawi MJ, Morwood MP. Acute Management of Open Fractures: An Evidence-Based Review. Orthopedics. 2015;38:e1025-e1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoff WS, Bonadies JA, Cachecho R, Dorlac WC. East Practice Management Guidelines Work Group: update to practice management guidelines for prophylactic antibiotic use in open fractures. J Trauma. 2011;70:751-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hohmann E, Tetsworth K, Radziejowski MJ, Wiesniewski TF. Comparison of delayed and primary wound closure in the treatment of open tibial fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127:131-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkinson RJ, Kiss A, Johnson S, Stephen DJ, Kreder HJ. Delayed wound closure increases deep-infection rate associated with lower-grade open fractures: a propensity-matched cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:380-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lack WD, Karunakar MA, Angerame MR, Seymour RB, Sims S, Kellam JF, Bosse MJ. Type III open tibia fractures: immediate antibiotic prophylaxis minimizes infection [published correction appears in J Orthop Trauma. 2015 Jun;29:e213]. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leonidou A, Kiraly Z, Gality H, Apperley S, Vanstone S, Woods DA. The effect of the timing of antibiotics and surgical treatment on infection rates in open long-bone fractures: a 6-year prospective study after a change in policy. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2014;9:167-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macy E, Blumenthal KG. Are cephalosporins safe for use in penicillin allergy without prior allergy evaluation? J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:82-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mangram AJ. A brief overview of the 1999 CDC Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J Chemother. 2001;13 Spec No 1:35-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meinberg EG, Agel J, Roberts CS, Karam MD, Kellam JF. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium-2018. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32:S1-S170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melvin JS, Dombroski DG, Torbert JT, Kovach SJ, Esterhai JL, Mehta S. Open tibial shaft fractures: I. Evaluation and initial wound management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:10-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patzakis MJ, Wilkins J. Factors influencing infection rate in open fracture wounds. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;243:36-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pichichero ME. A review of evidence supporting the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation for prescribing cephalosporin antibiotics for penicillin-allergic patients. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1048-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scharfenberger AV, Alabassi K, Smith S, Weber D, Dulai SK, Bergman JW, Beaupre LA. Primary Wound Closure After Open Fracture: A Prospective Cohort Study Examining Nonunion and Deep Infection. J Orthop Trauma. 2017;31:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas SH, Arthur AO, Howard Z, Shear ML, Kadzielski JL, Vrahas MS. Helicopter emergency medical services crew administration of antibiotics for open fractures. Air Med J. 2013;32:74-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torbert JT, Joshi M, Moraff A, Matuszewski PE, Holmes A, Pollak AN, O’Toole RV. Current bacterial speciation and antibiotic resistance in deep infections after operative fixation of fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:7-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber D, Dulai SK, Bergman J, Buckley R, Beaupre LA. Time to initial operative treatment following open fracture does not impact development of deep infection: a prospective study of 736 subjects. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:613-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson AP, Sturridge MF, Treasure T. Aminoglycoside toxicity following antibiotic prophylaxis in cardiac surgery. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;26:713-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yokoyama K, Uchino M, Nakamura K, Ohtsuka H, Suzuki T, Boku T, Itoman M. Risk factors for deep infection in secondary intramedullary nailing after external fixation for open tibial fractures. Injury. 2006;37:554-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.