Abstract

HIV prevalence among cisgender female sex workers (FSW) and/or women who use drugs (WWUD) is substantially higher compared to similarly aged women. Consistent with PRISMA guidelines, we conducted the first systematic review on the pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) continuum among FSW and/or WWUD, searching PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Sociological Abstracts. Eligibility criteria included: reporting a PrEP related result among FSW and/or WWUD aged 18+; peer-reviewed; published in English between 2012–2018. Our search identified 1,365 studies; 26 met eligibility requirements, across the following groups: FSW (n=14), WWUD (n=9) and FSW-WWUD (n=3). Studies report on at least one PrEP outcome: awareness (n=12), acceptability (n=16), uptake (n=4), and adherence (n=8). Specific barriers span individual and structural levels and include challenges to daily adherence, cost, and stigma. Combining health services and long-acting PrEP formulas may facilitate better PrEP uptake and adherence. The limited number of studies indicates a need for more research.

Keywords: Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), female sex workers (FSW), Women who use drugs (WWUD), Sytematic review, Global, PrEP care continuum

Resumen

La prevalencia del VIH es sustancialmente mayor entre trabajadoras sexuales cisgénero (FSW) y/o mujeres que usan drogas (WWUD) en comparación con mujeres de edad similar. Siguiendo PRISMA, realizamos la primera revisión sistemática sobre el continuo de la Profilaxis Preexposición (PrEP) entre estos grupos. Los criterios de elegibilidad fueron: informar un resultado de PrEP entre FSWs y/o WWUDs con mayores de edad; que haya pasado por revisión de pares; y publicados en inglés entre el 2012 y el 2018. Identificamos 1,365 estudios; 26 cumplieron los criterios: FSW (n=14), WWUD (n=9) y FSW-WWUD (n=3). Los estudios nos informaron sobre: conocimiento (n=12), aceptabilidad (n=16), uso, (n=4) y adherencia (n=8). Las barreras incluyen la adherencia, el costo, y el estigma. La combinación de los servicios de salud y de PrEP de acción-prolongada pueden facilitar mejor uso y adherencia a la PrEP. El número limitado de estudios indica la necesidad de más investigación.

Introduction

HIV prevalence among cisgender women who engage in transactional sex, [female sex workers (FSW)] and/or women who use drugs (WWUD) is substantially higher compared to similarly aged women throughout the world. In low and middle-income countries (LMICs) FSW’ HIV prevalence was estimated at 11.8% (95% CI 11.6 – 12.0)[1]. The HIV prevalence among WWUD may range from 0% to 65% [2]. As a user-controlled method, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) provides an empowering means of preventing HIV in vulnerable populations. However, adherence is crucial for successful risk reduction[3]. In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that PrEP be offered as an additional prevention choice for people at substantial risk of HIV,[4] yet little is known about PrEP utilization in these high risk and often overlapping populations.

Concurrency between sex work and drug use is high. WWUD often exchange sex to support drug habits[5]. Estimates of women who inject drugs (WWID) engaged in sex work range between 15–66% in the USA, 20–50% in Eastern Europe, 10–25% in Central Asia, and 21–57% in China[6]. While no global HIV prevalence estimates exist for FSW who are also WWUD (FSW-WWUD), sex work is associated with significantly higher HIV prevalence among WWUD[7] and active drug use is associated with higher HIV prevalence among FSW[6, 8]. Infectious diseases are occupational hazards for FSW, due to criminalization of sex work, unprotected sex, and multiple, high-risk sex partners[9–11]. WWID are more likely to engage in high risk injection practices with sex partners, or have a sex partner who injects drugs[5]. Behavioral risks are positioned in a broader socio-structural vulnerability context that drives substance use, victimization, and poor health outcomes, which synergistically and independently elevate women’s HIV risk[12–15]. Criminalization of sex work and egregious police behaviors,[16] imprisonment, poverty, housing instability, condom confiscation as sex work evidence, stigma, and discrimination all impede access to health care and HIV preventive services among FSW and WWUD[17, 18].

Following the 2012 Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) approval[19], multiple clinical trials have found that PrEP reduced HIV acquisition up to 70% in high adherence cases, whereas PrEP had no effect in low adherence cases[3, 20–23]. The only two PrEP trials among cisgender women were stopped early due to suboptimal adherence[22, 23]. Factors that increase HIV risk may also pose PrEP barriers. Studies of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) uptake and adherence in these populations have found interpersonal and structural barriers, such as HIV stigma, intimate partner violence, housing insecurity, and criminalization[24, 25]. In other HIV high-risk populations, such as MSM, social factors (e.g. anticipated stigma) and structural factors (e.g. healthcare provider attitudes, quality assurance, data protection, and cost) were determinants of potential PrEP uptake[26]. Questions remain concerning the unique barriers and facilitators for optimizing PrEP adherence among women who sell sex and/or use drugs.

Wide-scale PrEP implementation is recent, therefore little is known about acceptability and uptake[27]. The 2015 WHO PrEP recommendations[4] and recent scale-up of PrEP globally[28] point to an urgent need to understand PrEP use among high-risk and overlooked populations. A ‘PrEP care continuum’ has been previously proposed [29] and updated [30] for use in program evaluation. Our modified PrEP continuum includes: 1) awareness; 2) acceptability; 3) uptake; and 4) adherence. This systematic review aims to assess the state of peer-reviewed literature on PrEP awareness, acceptability, uptake and adherence among cisgender women who sell sex and/or use drugs.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We conducted a systematic review identifying peer-reviewed literature on the PrEP continuum among cisgender women who sell sex and/or use drugs, published in English from 2012–2018, following PRISMA guidelines[31]. A review protocol guided the process[32, 33]. With input from the research team, an information specialist from Welch Medical Library developed and conducted the search using PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Sociological Abstracts. Search strategies utilized a combination of controlled vocabulary and keywords defining the PrEP concepts and population. The PubMed search strategy is provided in Supplement Appendix A. Databases were first searched on 1 December 2017 and updated on 21 December 2018.

Included studies reported at least one quantitative or qualitative PrEP continuum outcome (awareness, acceptability, uptake, adherence) among cisgender women who sell sex and/or use drug aged 18 years or older and were published in a peer-reviewed journal, in English and after 2012, the year the FDA approved PrEP[19]. Excluded studies only focused on chemical efficacy of PrEP (i.e., pharmacological), did not involve oral agents, lacked primary data, or were review articles or case studies.

Data Analysis

Reviewers used Covidence (https://www.covidence.org) to screen articles. Two reviewers (BJ, KM) independently screened the titles and abstracts, meeting regularly with the lead author (JG) to resolve conflicts. A similar process was followed during full text review (reviewers: BJ, RR).

Two reviewers (BJ, RR) independently conducted data extraction. A standardized extraction spreadsheet was used for data management including: study country; study design; sample characteristics; PrEP continuum findings; and study limitations. Our data manager (DP) merged the spreadsheets and highlighted discrepancies. The team met to resolve conflicts. In no instances were authors contacted for additional information.

Systematic narrative synthesis was used to summarize and present key study findings and characteristics[34]. Findings are organized under the four key themes of our PrEP continuum [29, 30]: (1) Awareness; (2) Acceptability; (3) Uptake; and (4) Adherence. Tables 1 and 2 show a summary of key extracted results. Descriptive and multivariate data was abstracted when available and corresponding unadjusted data was not reported. Data is presented with the amount of specificity offered by the individual studies, and therefore number of decimal places may differ throughout the paper.

Table 1:

PrEP Awareness and Acceptability Findings among Women who Sell Sex and/or Use Drugs

| Author, Year | Study Design; Location | Sample Characteristics | PrEP Awa reness | PrEP Acceptability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bazzi et al (2017) [45] | In-depth interviews with content analysis; Kisumu, Kenya | FSW-WWID (within the last month, with a subset (5/9) who report sex work in the past month) | Two (of nine) women had heard of any biomedical HIV prevention methods (oral PrEP, n = 1; microbicide gels, n = 1). | All women were interested in trying at least one method, primarily to protect themselves from partners who were believed to have multiple sexual partners. Most women were interested in microbicide gels (n = 7) followed by intravaginal rings (n = 6) and oral PrEP (n = 5). |

| Eakle et al. (2018)[27] | Focus group discussions; Johannesburg and Pretoria, South Africa | FSW-WWUD (brothels, streets and other informal areas; the majority reporting injection drug use) | Prior to a detailed description of PrEP within the FGDs, awareness was low. | Overall, there was strong acceptability of PrEP among participants and positive anticipation for the imminent delivery of PrEP in the local sex worker clinics.

|

| Escudero et al (2015) [51] | Cross-sectional survey; Canada | IDU (active) | 36.5% of those willing to use PrEP were female; 42.2% of females were willing to use PrEP Females were more likely to be willing to use PrEP compared to males (OR 1.52 (95% CI 1.05 to 2.22) p=0.028). |

|

| Garfinkel et al (2017) [48] | Cross-sectional survey; Baltimore, MD, USA | Women of reproductive age. 8% of whom identified as ever trading sex | Women who had ever traded sex were almost five times more likely to consider taking PrEP (83% vs. 58%, aOR 4.94 (95% CI 2.00 to 12.22) p<0.001) then women who had not ever traded sex. | |

| Gnatienko et al (2018) [36] | Prospective observational cohort; St. Petersburg, Russia | PWID living with HIV | Female awareness of PrEP to prevent HIV transmission through sex (24%, n=5) and through injection drugs (4%, n=3) was low and similar to awareness among males. | |

| Jackson et al (2013) [42] | Cross-sectional survey; Nanchang, Uizhou, Nanning, Urumqi, Karamay, Yu Zhong, and Jui Long Po districts of Chongqing, China | FSW (Commercial sex venue based i.e. street, hotel, hair salon, sauna, massage, bar, dance hall, tea house) | The study included 101 women (25.6%) who were unwilling and 294 women (74.4%) who were willing to use HIV PrEP. Willingness to use PrEP groups did not differ on any demographic characteristic or measure of sexual experiences (all p’s > 0.11). Willing participants scored lower than unwilling participants on (1) PrEP stigma beliefs and higher on (2) thwarted belongingness, (3) trust in physicians, and (4) self-efficacy in using PrEP. |

|

| Mack et al (2014) [44] | Focus group discussions with inductive thematic analysis; Nairobi and Nakuru, Kenya | FSW | FSW in Kenya expressed great interest in PrEP products. However, the majority appeared to assume initially that PrEP would provide 100% protection against HIV, and many were disappointed to learn that they would still need to use condoms to prevent HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). FSW’ interest in PrEP was not only related to preventing HIV transmission, but also to helping them earn more money because they would feel safer accepting more clients or would feel more comfortable having sex without using condoms. The majority of FSW’ concerns regarding PrEP were related to its degree of effectiveness and to their preference for a PrEP product that could prevent both HIV and other STIs. They feared that some FSW (and other users) would forgo condoms if PrEP became available, thus increasing the likelihood of transmitting HIV and STIs. A few FSW expressed concern about side effects, either generally or in relation to particular formulations. Most of these participants emphasized the need to help each woman identify the formulation appropriate for her. |

|

| Ortblad et al (2018) [43] | Randomized controlled trial; Kampala, Uganda and Livingstone, Kapiri Mposhi, and Chirudu, Zambia | FSW | PrEP acceptability was high among participants in both studies. Almost all participants in Zambia (91%) and the majority of participants (66%) in Uganda reported being “very interested” in daily oral PrEP. | |

| Peitzmeier et al (2017) [41] | Cross-sectional survey; Baltimore, MD, USA | FSW-WWUD | 33% of the respondents had heard of PrEP. | 65% of the respondents were somewhat or very interested in taking PrEP when it was described. There was greater interest in a microbicidal vaginal ring, with three in four women (76%) somewhat or very interested. Of the 52 women who answered both questions, 12% were interested in PrEP but not a microbicidal ring, while 19% were interested in the ring but not PrEP, and 56% indicated interest in both methods. Women who had recently experienced physical or sexual violence from clients were more likely to be interested in PrEP (86% vs. 53%, p = 0.01) and microbicidal rings (91% vs. 65%, p = 0.03;) than women who had not recently experienced violence. Having a primary female partner and younger age were marginally significant. |

| Peng et al (2012) [38] | Cross-sectional survey; Chongqing, Guangxi, Xinjiang, and Sichuan Provinces, China | FSW | This study shows that 22 (1.4%) female sex workers had previously taken medication preventive against HIV (*Note it is unclear if the authors are including PEP with PrEP in this result.) 16.5% of participants reported having heard of PrEP from various sources, i.e., doctors (27%), researchers (26%), online media (16%), television (15%), friends (14%), and newspapers (9%). |

When PrEP was presumed to be safe and effective, 69% of participants expressed positive responses to “willingness to use PrEP” (95% CI 66.7 to 71.3). When it was also assumed that PrEP drugs will be provided for free, willingness to use PrEP increased to 72.6% (95% CI 70.3 to 74.7). When it was assumed that the PrEP would be freely provided and “a few people” had already been using it, the willingness rose to 77% (95% CI 74.9 to 79.1). When “a few people” was changed to “a lot more people”, the willingness further increased to 80.6% (95% CI 78.6 to 82.5). Participants were concerned about the safety (81.6%), efficacy (81.0%), cost (51.2%), convenience (19.2%), and accessibility (16.6%) of PrEP drugs. Regarding costs, 20.6% of the study participants expressed reluctance to purchase PrEP drugs with their own money; among those who were willing to purchase them, 18.2% were inclined to pay less than 100 RMB per month, 17.9% wanted to pay 100–200 RMB; and 17.3% wanted to pay 200–400 RMB. Even when they were told that PrEP drugs need to be taken daily, 46% of the participants said they “definitely” would take them, 21% said they would “probably” do so, and nearly 20% said they would “probably not” or “definitely not” persist with treatment. When comparing two hypothetical PrEP drugs, 74% of the participants preferred to use drugs that were more expensive but with longer medication intervals, while only 14% chose to use the cheaper option but with a much higher use frequency. Multivariate predictors to future use of PrEP/Willingnessto use PrEP, the following six significant predictors were selected:

|

| Pines et al (2018) [53] | Cross-sectional survey; Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico | FSW | Participants in Ciudad Juarez indicated a strong preference for oral pills (mean PWU =10.10, standard deviation [SD] =19.82) and a moderate preference for vaginal gels (mean PWU =2.14, SD =18.66), whereas participants in Tijuana indicated roughly equal preferences for oral pills (mean PWU =3.65, SD =21.39) and vaginal gels (mean PWU =3.81, SD =16.32). Product 1 (vaginal gel, on-demand use, 10 pesos per use, 80% effective, mild side effects, accessible at healthcare clinics) received the highest mean rating in Tijuana (77.56; SD=27.79) and Ciudad Juarez(76.91; SD =29.58). In Tijuana, formulation had the greatest influence on product ratings (mean IV =31.75, SD =15.92) followed by frequency of use (mean IV =20.40, SD =11.62), effectiveness (mean IV =17.24, SD =15.14), and cost per use (mean IV =12.22, SD =10.49). In Ciudad Juarez, formulation (mean IV =31.67, SD =15.29) and frequency of use (mean IV =18.28, SD =9.79) also had the greatest influence on product ratings; however, the impact of effectiveness (mean IV =16.60, SD =14.85) and cost per use (mean IV =16.71, SD =13.11) on product ratings were approximately equal. Access point (Tijuana: mean IV =9.75, SD =7.60; Ciudad Juarez: mean IV =8.71, SD =6.00) and side effects (Tijuana: mean IV =8.64, SD =7.25; Ciudad Juarez: mean IV =8.03, SD =6.43) had the least influence on product ratings in both cities. Participants in both cities indicated strong preferences for products that are 80% effective (vs. 40%), moderate preferences for products that cost 10 pesos per use (vs. 200) and can be used monthly (vs. daily or on-demand), and slight preferences for products that can be accessed at healthcare clinics (vs. NGOs), but no obvious preferences (mean PWUs < 0.50) regarding side effects Among participants whose part-worth utilities (PWUs) indicated a preference for one product formulation (N =268), 38%, 28%, 18%, and 17% preferred pills, gels, rings, and liquids, respectively. Compared to preferring pills, preferring gels was associated with reporting pain during vaginal sex (aOR 3.51 (95% CI = 1.13 to 10.84) p-value not reported) and vaginal lubrication practices (aOR 2.08 (95% CI 1.07 to 4.04) p-value not reported). Participants in both Ciudad Juarez (mean PWU=−10.97, SD =22.73) and Tijuana (mean PWU= −6.80, SD =21.75) indicated a strong aversion to vaginal rings. |

|

| Reza-Paul et al (2016) [47] | Mixed Methods: 1) Cross-sectional survey and 2) thematic and content analysis of in-depth interviews and focus group discussions; Karnataka, India | FSW(Through broker/pimp, public places, dhaba (roadside restaurant), lodge, hotel, motel, bar) | Following a PrEP awareness campaign, participants demonstrated a good knowledge and understanding of PrEP. | Almost all participants surveyed (95%, n = 406) expressed an interest in taking PrEP and among those, 89% stated that they would be willing to take PrEP every day PrEP was described (by participants) as a prevention strategy that could potentially ease the stress and fear associated with instances where condom use was not possible, providing peace of mind to women with the knowledge that they are protected from contracting HIV. Participants expressed that PrEP will allow them to maintain their health, thus protecting their earning potential and ability to support themselves, as well as their dependents. Many of the women interviewed had families for whom they were financially responsible. Participants viewed their earning potential as directly impacted by their health and they viewed taking PrEP as good for business. PrEP and Condoms

|

| Restar et al (2017) [46] | In-depth interviews with thematic analysis; Mombasa, Kenya | FSW (working in bars and nightclubs) | None of the 21 FSW in the study had previously heard of or utilized PrEP. | 19 of the 21 FSW in the study expressed willingness to utilize PrEP. Perceiving themselves to be at risk of HIV infection due to their exposure from having many sexual partners, most participants believed that PrEP would afford them added protection and be useful in situations in which they used condoms inconsistently or were unable to use them. Some sex workers also thought of PrEP as an expression of self-love and self-care. These participants conveyed the idea that choosing to take PrEP was tantamount to making a choice to live, and that PrEP would constitute a form of active engagement in their HIV-prevention efforts. A minority of participants voiced concerns about potential negative side effects of PrEP, and some of these participants said that these side effects would deter them from using PrEP. While none of the participants mentioned a particular side effect and how exactly they had come to know about possible side effects, others stated that they would consider using PrEP intermittently but not daily, on the assumption that daily use was certain to cause side effects. Others expressed their willingness to use PrEP despite any negative side effects. |

| Roth et al. (2018) [52] | Cross-sectional; Camden, New Jersey, USA | PWID (injecting illicit drugs within the past 6 months) | Women were more likely than men to express willingness (88.9% vs. 71.0%; p < 0.02). Despite these high levels of willingness, female participants reported that they would feel anxious (50.0%) or embarrassed (40.7%) about taking PrEP, and would not want their sexual partner(s) to know they were taking PrEP (46.2%). These feelings/attitudes did not vary significantly by sex. Women were more likely than men to report willingness to tolerate adverse effects (80.5% vs. 60.0%; p < 0.03) and quarterly HIV testing (95.9% vs. 82.5%; P < 0.03) |

|

| Roth et al. (2018) [37] | Cross-sectional; Pennsylvania, USA | PWID (mobile SEP participants) | Participants who reported being aware of PrEP compared to those unaware of PrEP were more likely to be women (35.5% vs. 23.9%, p = 0.03). | |

| Shrestha et al (2017) [50] | Cross-sectional survey; New Haven, CT, USA | High-risk drug users on methadone treatment | 66.9% of females were willing to initiate PrEP There was no association between willingness to initiate PrEP and gender (OR 1.35 (95% CI 0.90, 2.05) p=0.152) |

|

| Stein et al (2014) [49] | Cross-sectional survey; Fall River, MA, USA | IDU (Opiates) | 50.5% of women were willing to take PrEP. There was no association between willingness to take PrEP and gender. (X2 0.63, p = 0.63) Willingness to take PrEP was not associated significantly with gender (X2=0.72; p = 0.40) |

|

| Walters et al (2017) [35] | Cross-sectional survey; New York City, NY, USA | PWID (Cocaine and heroin- a subset of whom are women) | 12% of female IDU in the NYC Sample were aware of PrEP/PEP. When controlling for race, household income, education, age, HIV status, non-injection drug use, and exposure to HIV prevention professionals, female IDU in the NYC sample had 52% decreased odds (aOR 0.48 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.96) p<0.05 [full p-value not reported]) of PrEP/ PEP awareness compared to MSM. 8% of female IDU in the Long Island, NY sample were aware of PrEP/PEP When controlling for race, household income, education, age, HIV status, non-injection drug use, and exposure to HIV prevention professionals, female IDU in the Long Island, NY sample had 74% decreased odds (aOR 0.26 (95% CI 0.07 to 0.90)) of PrEP/PEP awareness compared to MSM |

|

| Walters et al (2017)[40] | Cross-sectional survey; New York City, NY, USA | FSW-WWID (with subset of those who engage in transactional sex) | Of the 118 WWID included in this analysis, 37 (31%) had heard of PrEP and only one WWID reported taking PrEP. WWID who reported transactional sex were over three times more likely to report awareness of PrEP compared to WWID who did not report transactional sex (aOR 3.32 (95% CI 1.22 to 9.00) p<0.05). Additional significant findings were that WWID who had a conversation about HIV prevention at a syringe exchange program were over seven and a half times more likely to be aware of PrEP (aOR 7.61 (95% Cl 2.65 to 21.84)). The study did not find race, education, household income, age, binge drinking, or sexual identity to be significantly associated at the p < 0.05 level with awareness of PrEP. Healthcare variables, including variables indicating conversations about HIV prevention at other settings (such as at a doctor’s office, health center, clinic, or hospital) were tested in the multivariable model, and there were no correlations. |

|

| Wanyenze, et al (2017) [54] | Focus group discussions; Uganda-districts of Kampala, Mukono, Rakai, Busia, Iganga, Mbale, Soroti, Lira, Gulu, Mbarara, Hoima, Bushenyi | FSW | Sex workers across various groups noted the limited information about pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis. | |

| Ye et al (2014) [39] | Cross-sectional survey; Nanning, Liuzhou, and Beihai in Guangxi Province, China | FSW (Those who work in male dominated venues (hotels, nightclubs massage parlours) and street based places (barber shops and streetwalkers) | Of all participants, 15.1% had heard of PrEP. | 85.9% participants reported that they were willing to use PrEP in the future if it was proven to be safe and effective. Of those unwilling to accept PrEP (n=57), the majority (89.5%) were concerned about the side effects of PrEP, 50.9% thought they were not at risk of HIV through commercial sex. Other reasons included the belief that PrEP was not necessary or not effective (36.8%), concern about objections from family (31.6%) and discrimination by others (17.5%) In a multivariable logistic regression model, the analysis showed that eight variables were associated with PrEP acceptability. An increased acceptability was associated with

|

Table 2:

PrEP Uptake/Adherence Findings among Women who Sell Sex and/or Use Drugs

| Author, Year | Study Design; Location | Sample characteristics | PrEP Uptake | PrEP Adherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cowan et al (2018) [57] | Cluster randomized trial; Zimbabwe | FSW | 38% (n=500) of the 1302 HIV-negative women who were offered PrEP and screened for eligibility opted to start PrEP in the intervention sites. | |

| Eakle et al (2017) [55] | Prospective observational cohort study; South Africa | FSW (brothel, hotel, street, and bar based) | Among those returning to clinic after HIV testing and clinical screening, 93% were confirmed eligible for PrEP. From those eligible, 98% initiated PrEP. | Of those enrolled, 22% on PrEP (n=49) were seen at 12 months. High rates of loss to follow-up were observed: 71% (n=156) in the PrEP group Self reported adherence to PrEP varied over time between 70% and 85%, whereas over 90% of participants reported taking pills daily while on early ART. Four women withdrew (due to side effects or moving to another location); eight women reported mild headaches, nausea, drowsiness, dizziness and diarrhea. It is possible that some women moved to other sites without the study’s knowledge, as other sites started offering PrEP and early ART. |

| Eakle, et al (2018) [27] | Focus group discussions; Johannesburg and Pretoria, South Africa | FSW (brothels, streets and other informal areas) | The risk of potential non-adherence, and thus diminished PrEP effectiveness, was commonly expressed. Many participants felt that some women may not be sufficiently motivated to take a pill every day, especially when they were not feeling unwell. Additional worries around adherence included substance use (alcohol and illicit drugs) and the potential for forgetting to take a daily pill.. There was also discussion about how lessons learned in ART adherence among HIV-positive women could help improve adherence among those taking PrEP, such as aligning pill taking with television shows, using phone alarms, and coming up with strategies to keep pills on hand such as in secret bra compartments. The discussion of substance use raised questions about whether PrEP could be taken when someone knew they would be drinking or using other substances during the course of the day. Explaining that using alcohol or other drugs would not diminish the preventive effects of PrEP was met with approval. The need for social support, often initially voiced by women with ART experiences, was identified universally as a valued component of pill-taking and a way to help ensure commitment. |

|

| Mack et al (2014) [44] | Focus group discussions with inductive thematic analysis; Nairobi and Nakuru, Kenya | FSW | The majority of FSW clearly preferred an injectable over other formulations. They liked that one dose would last for a prolonged period of time and would require little user intervention, unlike a pill that they must remember to take every day. In addition, injections were perceived as relatively private, making it less likely that others would know a woman was using the product. A few women described alcohol use as potentially interfering with their ability to take a daily pill but not posing a problem with injections. Most FSW were concerned that they might forget or that it would be burdensome to take a pill consistently. Several women were concerned about side effects associated with an oral product or interactions between pills and alcohol. A few women were worried that people would see them taking pills, whereas others liked the idea of taking a pill because it was daily, something they controlled and similar to contraceptive pills. Nearly all FSW reported using some form of vaginal lubricant in the past; however, there was little interest in PrEP gel. Most FSW said they would prefer to apply a gel before sex rather than afterwards; however, they saw problems with applying the gel at any point. Although the gel might help with lubrication before sex, some FSW noted that there would not always be time to apply it before sex and those FSW who are drunk or high might forget to use it. Those who cited specific limitations with post-coital use most often noted that women were tired after sex and unlikely to remember to use it. They also mentioned clients might be against using the gel. |

|

| Martin et al (2017) [58] | Observational cohort study; Bangkok, Thailand | WWID (Heroin, meth, midazolam) | 58% of females chose to take tenofovir Bivariable analysis, comparing male to female uptake of PrEP, found no significant difference by gender (OR 1.2 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.5) p=0.16). |

14% of females were adherent at greater than 90 days (self reported diary entries). In the multivariable analysis, tenofovir adherence on more than 90% of the days in follow-up was more likely in male versus female participants, (males aOR 1.9 (95% CI 1.0 to 3.6) p=0.04) |

| Martin et al (2015)[59] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, endpoint driven study; Bangkok, Thailand | WWID (Meth, heroin, midazolam, methadone) | 47.7% of women had poor adherence (<95%) (self reported diary entries). Controlling for age, women were more adherent (median 95.6%, IQR 81.1–98.9%) than men (median 93.8%, IQR 78.8–98.7%, p = 0.04). In multivariable analysis, men were more likely to report less than 95% adherence than women (p = 0.01). |

|

| Mboup, et al (2018) [56] | Prospective observational cohort; Cotonou, Benin | FSW | Among women eligible for PrEP, 88.3% (256/290) began PrEP. | Overall PrEP retention at the end of the study was 47.3% (121/256) (Self reported data). 61.2% (109/178) of withdrawals from the study were due to participants moving away from the study site. Among PrEP participants, perfect adherence decreased over time (p <0.0001). It was 78.4% (156/ 199) at day 14 and 43.3% (65/150) at the final visit (p <0.0001). FSW <25 years old were less likely to report perfect adherence compared to those >25 years old (prevalence ratio [PR] 0.76 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.93) p=0.006) |

| Peitzmeier et al (2017)[41] | Cross-sectional survey; Baltimore, MD, USA | FSW-WWUD | Four out of five respondents (79%) said it would be somewhat or very easy for them to take a daily pill, 78% said they would take PrEP even if they had to wear condoms for full protection from HIV. | |

| Reza-Paul et al (2016) [47] | Mixed Methods: 1) Cross-sectional survey and 2) thematic and content analysis of in-depth interviews and focus group discussions; Karnataka, India | FSW (Through broker/pimp, public places, dhaba (roadside restaurant), lodge, hotel, motel, and bar) | Challenges in taking PrEP every day among surveyed FSW (N = 424):

The need for long-term adherence was of concern. Participants pointed to challenges with medication compliance as an example of the difficulties that people have in finishing their course of treatment, once symptoms subside. These difficulties with long-term compliance are also to be expected when medication is prescribed for prevention purposes, such as is the case with PrEP. PrEP availability should be individualized based on each participant’s preferences. Some women prefer to take a month’s supply, as they are not able to regularly come to the office, either because they live far away or because frequent visits may cause suspicion at home. Other women prefer to come daily or weekly, due to concerns that someone may find their tablets in the house and question them. Nearly half of participants (47%) surveyed wished to collect PrEP weekly, while about one-quarter preferred either daily or monthly pick-up. Surveyed participants interested in taking PrEP preferred to collect it from peer educators/community leaders (69%), the Ashodaya Clinic/Drop-1 n Centre (13%), delivered to their home (9%), or collected from a friend (8%). Confidentiality, privacy, and trust were the most important factors in choosing this person. |

Language Use

Language for women and drug use varied throughout included studies. Overwhelmingly, when discussing sex work, authors utilized sexed language (e.g., female sex workers) whereas when talking about drug users, gendered language was more common (e.g., women who use drugs). The authors’ language is used when discussing their studies and therefore we switch between sex and gender language. For drug use, some authors specified injection practices (e.g. women injection drug users) while others did not (e.g., women who use drugs); some defined the individual by the behavior (e.g., injection drug user) others described an individual with a behavior (e.g., woman who injects drugs). We specify injection drug use when relevant, and use person-centered language to align with current best practices, with the exception of FSW, the more common term in the field, acknowledging that it does not follow this person-centered trend.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

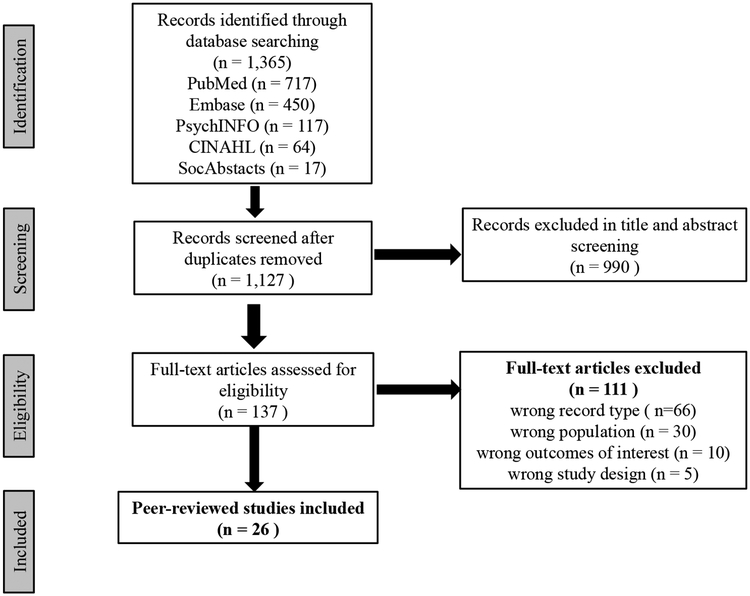

The online publication database search identified 1,365 articles; 1,127 after removing duplicates. A review of titles and abstracts revealed that 990 were irrelevant, leaving 137 articles for full-text assessment. Of these, 111 records were excluded because of the following: wrong record type (n=66), wrong population (n=30), wrong outcomes of interest (n=10), and wrong study design (n=5). In total, 26 articles were included in this review. Figure 1 presents a PRISMA flow diagram for article selection.

Figure 1:

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Characteristics of included studies

Our narrative study synthesis integrated 26 original studies including: quantitative (77%), qualitative (20%), and mixed-methods (3%) designs (Appendix: Figure 3). Acceptability was the most frequently discussed outcome (n=16), followed by awareness (n=12), adherence (n=8), and uptake (n=4; Appendix: Figure 5). The most common study location was the United States of America (U.S.) (n=8, 31%). Many locations were only represented once (Canada, Mexico, Zambia, Russia, Zimbabwe, Benin, and India; Appendix: Figure 4). Our target population encompassed women with multiple risk factors including FSW (n=13, 50%), WWUD (n=9, 35%), and overlapping FSW-WWUD (n=4 15%; Appendix: Figure 2).

PrEP Awareness

We characterized PrEP awareness as having known of PrEP prior to the study. We report on individuals taking PrEP prior to the study and PrEP information sources. Overwhelmingly, studies reported a lack of PrEP awareness across target populations and geographic regions (4–33%). WWUD studies reported the widest range (4–36.5%)[35–37]. FSW studies reported a lower range (15–17%)[38, 39] than FSW-WWUD studies (31–33%)[40, 41]. WWID who reported transactional sex were over three times more likely to report PrEP awareness compared to WWID who did not (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 3.32 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.22 to 9.00) p < 0.05[40]. Another PWID study found that women were more likely to be PrEP aware than men[37]. A few studies reported low numbers of past PrEP experience.

Only two studies provided insight on how people became aware of PrEP. In a study conducted in China, FSW learned about PrEP from doctors (27%), researchers (26%), online media (16%), television (15%), friends (14%), and newspapers (9%)[38]. In New York City (NYC), WWID who had a HIV prevention conversation at a syringe exchange program (SEP) were 7.5 times more likely to be PrEP aware (aOR 7.61 (95% CI 2.65 to 21.84) p<0.001 [40]. WWID in NYC were at decreased odds of being PrEP/PEP aware compared to MSM (52–74%)[35].

PrEP Acceptability

We characterized PrEP acceptability as interest in or willingness to take PrEP. Studies reporting acceptability data often discussed perceived PrEP advantages and disadvantages. Acceptability was the most frequently discussed outcome (n=16). PrEP acceptability was particularly high among FSW (66–95%). Among WWUD, rates were slightly lower (42.2–88.9%).

Factors associated with willingness varied across geographic locations. Three FSW studies occurred in China. One found that willing FSW had less PrEP stigma beliefs, higher trust in physicians, and PrEP self-efficacy. There was no relationship between willingness, demographics, and measures of sexual experiences[42]. Another study found that 21% of FSW expressed reluctance to purchase PrEP. When cost barriers and peer acceptability were addressed, PrEP willingness rose from 69 to 80%. When comparing two regimens, 74% of FSW preferred PrEP that was more expensive with longer medication intervals[38]. A third study found that side effects (90%) and low HIV risk perception (51%) were the primary reasons for PrEP unacceptability[39]. While income was not associated, prior use of drugs to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV knowledge were positively associated with uptake in two of the studies [38, 39].

Studies conducted with FSW and FSW-WWUD throughout Africa found that PrEP acceptability was high. Acceptability was 91% in Zambia and 66% in Uganda[43]. Strong acceptability was also found among FSW-WWUD in South Africa; PrEP motivations included choice, control, vulnerability, and managing PrEP risks and worries. Sexual violence experiences were particularly motivating. While women saw the benefits of PrEP, they wanted PrEP to be used in conjunction with condoms[27]. Among Kenyan FSW, interest in PrEP was high but women were disappointed that condoms would still be necessary to prevent STIs [44]. In a second Kenyan study, FSW were PrEP motivated to protect against risk from their partners’ concurrent relationships but were concerned about side effects and efficacy [45]. A third Kenyan study found that some FSW thought of PrEP as an expression of self-love [46]. For FSW in this study and another in India, PrEP acceptability and interest were driven by HIV protection desire, especially when condoms were less reliable or not possible [46, 47].

Among North American studies, women who had ever traded sex were almost five times more likely to consider taking PrEP (83% vs. 58%; aOR 4.94 (95% CI 2.00 to 12.2) p<0.001) than women who had not[48]. Two studies among persons who use drugs (PWUD) found no association between gender and acceptability,[49, 50] while two others found that females were more willing to use PrEP than males (OR 1.52 (95% CI 1.0 to 2.22) p=0.028)[51, 52]. Hesitations around anxiety, embarrassment, and privacy did not vary by gender[52].

Alternative forms of PrEP administration were explored in three studies. Kenyan FSW-WWUD expressed approximately equal interest in microbicide gels (n=7), intravaginal rings (n=6), and oral PrEP (n=5),[45] whereas in the US, FSW-WWUD preferred microbicidal vaginal rings (76%). FSW-WWUD who had recently experienced physical or sexual violence from clients were more likely to be interested in PrEP (86% vs. 53%, p =0.01) and microbicidal rings (91% vs. 65%; p = 0.03) than women who had not [41]. Formulation (preference for pills and gels, aversion to vaginal rings) and frequency of administration (preference for monthly) had the greatest impact on PrEP preferences among FSW in two Mexican cities[53].

Two studies assessed the influence of setting on accessing PrEP. In South Africa, offering PrEP in a supportive, non-judgmental, and flexible service environment tailored to FSW was considered paramount to successful implementation[27]. However, in Mexico, access point had the least influence on product ratings[53].

PrEP Uptake

PrEP uptake was defined as PrEP initiation during the study period, assessed in four studies. In South Africa, 98% of the PrEP eligible FSW (HIV-negative) (N=224) initiated use,[55] whereas in Benin 88.3% of FSW (N=290) initiated,[56] and in Zimbabwe only 38% of FSW (N=1302) initiated[57]. In Thailand, 58% of PWID (N=274) initiated PrEP; no significant difference in uptake by gender was found[58].

PrEP Adherence

PrEP adherence, evaluated in eight studies, was characterized as compliance as prescribed throughout a study. We report observed adherence rates and anticipated barriers and facilitators.

Four studies included self-reported adherence measures. In South Africa, FSW adherence fluctuated over time (70%−85%)[55]. Among FSW in Benin, perfect adherence declined over time; adherence at the final visit was 43.3%. Younger women were less likely to report perfect adherence compared to older women (OR 0.76 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.93) p=0.006)[56]. Among PWID in Thailand, 47.7% of women had poor adherence. Women were more adherent than men (aOR 1.4 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.7) p=0.006)[59]. In a follow up study, only 14% of females were adherent at 90 days. Contrary to the original study, adherence was more likely in male participants (aOR 1.9 (95% CI 1.0 to 3.6) p=0.04)[58].

One study, among FSW-WWUD in the U.S., reported anticipated PrEP adherence; 79% stated that it would be somewhat or very easy for them to take PrEP daily; 78% said they would take PrEP even if they had to wear condoms for full HIV protection[41].

Three studies examined anticipated adherence challenges and facilitators. The perceived challenge of daily adherence was raised in all studies. In South Africa, daily use was a concern related to substance use and being asymptomatic among FSW-WWUD[27]. In India, 33% of FSW expressed daily intake as a challenge to adherence[47]. In Kenya, the majority of FSW preferred injectable PrEP over other formulations, expressing the following concerns of a daily pill: forgetting to take it; being burdensome; being more intrusive than injections; and privacy concerns. Others liked the self-control of taking a daily pill, similar to contraceptive pills[44]. In all studies, women described alcohol and drug use as potentially interfering with daily adherence. In India, 22.6% of FSW indicated that alcohol could be an obstacle; many also expressed concern of interactions between PrEP and alcohol[47]. These concerns were echoed among South African FSW-WWUD[27]. Kenyan women stated alcohol would not pose a problem with PrEP injections. Concerns regarding potential side effects, privacy, and stigma were raised in two studies. The majority (61.8%) of participants in India were worried about side effects; 47% of FSW were concerned that others might see them take PrEP, and 37% that people might suspect that they have HIV[47]. Several Kenyan women were concerned about side effects; a few were worried that people would see them taking pills[44]. Additional concerns were raised in India including: partners would not allow women to take PrEP (39%); travel challenges (collect medicine, regular check-ups) (26%); and cost (10%). Many respondents (69%) cited peer educators/community leaders as their preferred source for accessing PrEP, noting confidentiality, privacy, and trust as important factors[47]. Women in South Africa stressed social support to ensure adherence, especially from women with ART experience[27].

Discussion

This systematic review was the first to assess the state of PrEP continuum literature related to FSW and/or WWUD, target populations with high HIV prevalence[1, 2] that play a role in the HIV epidemic[60]. Focusing on these overlapping and adjacent populations was insightful. Though in certain geographic contexts these groups are distinct[6], overlap between sex work and drug use is common. Women participating in these high-risk behaviors face similar structural vulnerabilities and are often overlooked populations for HIV-related research and prevention. The implications of our findings must be considered in light of these geographic and cultural distinctions. Few studies assessed PrEP uptake or adherence barriers and facilitators. Geographic variability was also limited. Though the paucity and inconclusiveness of these findings are disappointing (n=26), they match existing literature indicating that these are underserved populations[61] and point to a need for more research and intervention with these high-risk populations. However, 35% of these papers (n= 9) were published in 2018 indicating the field is currently expanding and findings from this review can guide future priorities.

This review not only indicates a concerning overall deficiency of PrEP awareness across our high-risk target populations, but also suggests the potential heterogeneity of PrEP awareness by subgroup. WWUD had the widest range of PrEP awareness (4–36%), and also the highest number of studies. While FSW-WWUD (31–33%) were more aware of PrEP compared to FSW (15–17%), they were included in the fewest number of studies.

This gradient is perhaps an effect of women with both risk factors having a higher likelihood of engaging with services for one reason or the other, thereby learning about PrEP. However, given the differences in the number of studies per population, there remains uncertainty in the true levels of awareness in each group. PrEP awareness among MSM, a frequent target for HIV interventions, was only 29.7% (95% CI = 16.9, 44.3) in LMICs,[26] and 63.3% in the U.S.,[62] indicating that higher income countries may be better able to raise awareness. Though our study also included higher income countries, awareness remained low. These results could indicate that awareness campaigns, while potentially effective for certain key populations, are not reaching the high-risk populations of FSW and/or WWUD. Awareness efforts need enhancement to address these shortcomings.

Comparable reports of acceptability across high-risk populations suggest that PrEP is a favorable method for prevention. PrEP acceptability among MSM (64.4% in LMICs[26]; 64.15% in U.S.[62]) was fairly similar to acceptability among our target populations with slightly higher acceptability reports among FSW (65–95%), and slightly lower rates among WWUD (42–89%.) The challenge to PrEP uptake may not be making the regimen more acceptable, but rather informing people that PrEP is an option.

Complementary to our findings, a review of FSW HIV prevention studies indicated high PrEP acceptability and concerns about STI risk and cost[63], leading to suggestions for intervention setting and implementation. Across studies, FSW were pleased to have PrEP as an option for prevention in scenarios where condoms were absent, but disappointed that PrEP did not prevent against other STIs or unwanted pregnancies. These findings indicate high acceptability likelihood among our target populations for forthcoming multipurpose technologies (MPT) [64], which may best serve these women’s’ needs. Further, introducing PrEP programs at women’s’ clinics or STI testing facilities may make women more comfortable initiating PrEP, as they also have access to additional reproductive healthcare. Similarly, as WWUD reported learned of PrEP at SEPs, these locations, along with treatment programs, may be ideal for PrEP intervention education and engagement[65]. Cost was another shared concern. Given the lack of resources in these populations, FSW and/or WWUDs may not prioritize PrEP over more immediate needs. Offering subsidized or free PrEP may improve acceptability and facilitate access. Understanding resource prioritization among this population would help better characterize this population’s needs and inform intervention development.

Although our review contained minimal findings concerning uptake, one study did report that uptake among PWUD did not differ by gender. This is in contrast to a review of PrEP among a general US population[66]. Many PWUD studies were excluded for not presenting gender-stratified findings. This coupled with the lack of studies on PrEP uptake makes understanding gendered differences among PWUD and/or FSW difficult, further supporting the need for more research and presentation of data by gender.

A key adherence-related finding from our study is the need to develop and research long-acting PrEP formulas that do not require daily maintenance[53, 67]. Long-acting PrEP formulations and alternative regimens were indicated as potential solutions to adherence barriers among our population, and could possibly be considered in conjunction with MPTs[68]. Further, as different dosing regimens impact efficacy and may vary in the protection offered through different risk behaviors,[69] determining the level of PrEP adherence necessary for protection against HIV acquisition via vaginal sex and injection drug use is imperative[70]. Notably, only two studies considered adherence barriers and facilitators; both were with FSW in hypothetical situations. Alcohol was a potential barrier to daily adherence, specifically fears regarding its interactions with PrEP. No other substances were highlighted as concerns. Among PWUD, many questions remain on drug-PrEP interactions and whether drug use behavior or treatment programs may influence medication adherence. Though PrEP rollout in these populations is nascent and research on real-world adherence experiences is needed, anticipated obstacles and supports can guide program planning. While treatment has been found to independently decrease HIV risk,[71, 72] delivery of these programs in conjunction with targeted HIV PrEP prevention initiatives could lead to further risk reduction [73, 74].

Many of the findings in this systematic review focused on personal and interpersonal barriers to adherence. Apart from concerns about privacy and finances, there was little about structural factors affecting adherence. Housing insecurity and criminalization of sex work and drug use have both been found to affect ART adherence[25, 75, 76], and while such factors also likely impact PrEP adherence, no studies explored these relationships.

The majority (69%; n=18) of our studies mentioned limitations regarding self-reporting and social desirability bias. Lack of generalizability (46%; n=12), small sample sizes (35%; n=9) and non-random sampling strategies (35%; n=9) were also discussed. Studies that utilized hypothetical willingness to initiate and adhere to PrEP warned that data may not represent real world behavior (31%; n=8). There were also a few paper-specific limitations involving outcome categorization. For example, one study did not differentiate between PrEP and PEP when asking participants about “antiretroviral HIV prevention medications,”[35] therefore PrEP specific findings were unavailable.

Limitations

Our systematic review has several limitations. First, the search terms developed for database-use focused on PrEP uptake and adherence. While becoming better acquainted with the literature, we found additional information along the continuum to include awareness and acceptability. Had our search strategy included these concepts explicitly, we may have found additional records. Additionally, we limited our study to peer-reviewed literature. Though the populations are clearly under-served, grassroots efforts, which may be more likely to meet their HIV prevention needs, may not be publishing in peer-reviewed journals.

Another study limitation included our inability to systematically assess risk of bias. Our aim was to conduct a broad review including various study designs and complementary viewpoints on the topic. However, this limited our capacity to conduct systematic risk of bias assessment. Our systematic review offers a snapshot in time, and ongoing reviews will reveal emerging understandings on the topic.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the HIV risk faced by these populations is great, and, though currently expanding, research and practice addressing PrEP among these populations is limited. These shortcomings speak to a broader lack of focus on both of these groups, and the gendered nature of this omission. The complicated structural drivers of risk, which are lacking in the above studies, coupled with the individual-level risk factors associated with these populations, require complex evidence-based interventions. Without better research to understand these intersecting factors, there is a gap in knowledge to inform effective intervention development, though lessons can be gleaned from work with other key populations. Our findings suggest that combining health services, for example introducing PrEP at women’s’ clinics, STI testing facilities or drug treatment programs, as well as develop and research long-acting PrEP formulas and alternative regimens that do not require daily maintenance, may facilitate better uptake and adherence to medication. While PrEP will not serve all HIV prevention needs for our target populations, it is a key addition to current prevention efforts[63]. The results from this systematic review can both guide researchers in where to fill gaps related to PrEP awareness, acceptability, uptake, and adherence with women who sell sex and/or use drugs, while simultaneously informing the development of pilot interventions aimed at these issues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors of the included studies. We also thank Kenneth Morales, MPH for his assistance in the title abstract review process. This work was supported by the NIH/NIDA (R34DA045619-02), the Drug Dependence Epidemiology Training Program, NIH/NIDA (T32DA007292), the Johns Hopkins University Hopkins Population Center (R24HD042854) and the Johns Hopkins Center for AIDS Research.

List of abbreviations

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- CI

confidence interval

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FSW

female sex workers

- FSW-WWUD

female sex workers who are also women who use drugs

- IDU

injection drug users

- LMIC

lower and middle income countries

- MSM

men who have sex with men

- MPT

multipurpose technologies

- PrEP

pre-exposure prophylaxis

- PWID

people who inject drugs

- PWUD

persons who use drugs

- RCT

randomized control trial

- SEP

syringe exchange program

- STIs

sexually transmitted infections

- TDF/FTC

tenofovir and emtricitabine medication

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WWID

women who inject drugs

- WWUD

women who use or inject drugs

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Competing interests

We declare no competing interests.

Works Cited

- 1.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2012;12(7):538–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larney S, Mathers BM, Poteat T, Kamarulzaman A, Degenhardt L. Global epidemiology of HIV among women and girls who use or inject drugs: current knowledge and limitations of existing data. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2015;69(Suppl 2):S100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization WH. Policy brief: pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): WHO expands recommendation on oral pre-exposure prophylaxis of HIV infection (PrEP). 2015.

- 5.Cleland CM, Des Jarlais DC, Perlis TE, Stimson G, Poznyak V. HIV risk behaviors among female IDUs in developing and transitional countries. BMC public health. 2007;7(1):271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts A, Mathers B, Degenhardt L. Women who inject drugs: A review of their risks, experiences and needs A report prepared on behalf of the Reference Group to the United Nations on HIV and Injecting Drug Use Australia Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC), University of New South Wales; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Astemborski J, Vlahov D, Warren D, Solomon L, Nelson KE. The trading of sex for drugs or money and HIV seropositivity among female intravenous drug users. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(3):382–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baral S, Todd CS, Aumakhan B, Lloyd J, Delegchoimbol A, Sabin K. HIV among female sex workers in the Central Asian Republics, Afghanistan, and Mongolia: contexts and convergence with drug use. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2013;132:S13–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loza O, Patterson TL, Rusch M, Martínez GA, Lozada R, Staines - Orozco H, et al. Drug-related behaviors independently associated with syphilis infection among female sex workers in two Mexico–US border cities. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1448–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Staines H, Lozada R, Orozovich P, Bucardo J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of HIV infection among female sex workers in 2 Mexico—US border cities. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2008;197(5):728–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders T. A continuum of risk? The management of health, physical and emotional risks by female sex workers. Sociology of health illness. 2004;26(5):557–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abad N, Baack BN, O’Leary A, Mizuno Y, Herbst JH, Lyles CM. A systematic review of HIV and STI behavior change interventions for female sex workers in the United States. AIDS Behavior. 2015;19(9):1701–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Chen M, Mooss A. HIV risk among female sex workers in Miami: the impact of violent victimization and untreated mental illness. AIDS care. 2012;24(5):553–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buttram ME, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. Resilience and syndemic risk factors among African-American female sex workers. Psychology, health, and medicine. 2014;19(4):442–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, Tyndall MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Social science medicine. 2008;66(4):911–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Footer KH, Silberzahn BE, Tormohlen KN, Sherman SG. Policing practices as a structural determinant for HIV among sex workers: a systematic review of empirical findings. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2016;19:20883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Bassel N, Shaw SA, Dasgupta A, Strathdee SA. Drug use as a driver of HIV risks: re-emerging and emerging issues. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2014;9(2):150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Des Jarlais DC, Feelemyer JP, Modi SN, Arasteh K, Hagan H. Are females who inject drugs at higher risk for HIV infection than males who inject drugs: an international systematic review of high seroprevalence areas. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2012;124(1):95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Administration FD. Truvada for PrEP fact sheet: ensuring safe and proper use. 2012. 2015.

- 20.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(5):399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(5):423–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Der Straten A, Brown ER, Marrazzo JM, Chirenje MZ, Liu K, Gomez K, et al. Divergent adherence estimates with pharmacokinetic and behavioural measures in the MTN - 003 (VOICE) study. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2016;19(1):20642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(5):411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, Duff P, Mwangi P, Rusakova M, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. The Lancet. 2015;385(9962):55–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duff P, Goldenberg S, Deering K, Montaner J, Nguyen P, Dobrer S, et al. Barriers to viral suppression among female sex workers: role of structural and intimate partner dynamics. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2016;73(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yi S, Tuot S, Mwai GW, Ngin C, Chhim K, Pal K, et al. Awareness and willingness to use HIV pre - exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in low - and middle - income countries: a systematic review and meta - analysis. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2017;20(1):21580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eakle R, Bourne A, Mbogua J, Mutanha N, Rees H. Exploring acceptability of oral PrEP prior to implementation among female sex workers in South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2018;21(2):e25081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) [press release]. 31 OCTOBER 2016.

- 29.Kelley CF, Kahle E, Siegler A, Sanchez T, Del Rio C, Sullivan PS, et al. Applying a PrEP continuum of care for men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;61(10):1590–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nunn AS, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Oldenburg CE, Mayer KH, Mimiaga M, Patel R, et al. Defining the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care continuum. Aids. 2017;31(5):731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151(4):264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews. 2015;4(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Bmj. 2015;349:g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O, Peacock R. Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: a meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Social science medicine. 2005;61(2):417–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walters SM, Rivera AV, Starbuck L, Reilly KH, Boldon N, Anderson BJ, et al. Differences in Awareness of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis and Post-exposure Prophylaxis Among Groups At-Risk for HIV in New York State: New York City and Long Island, NY, 2011–2013. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2017;75 Suppl 3:S383–s91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gnatienko N, Wagman JA, Cheng DM, Bazzi AR, Raj A, Blokhina E, et al. Serodiscordant partnerships and opportunities for pre-exposure prophylaxis among partners of women and men living with HIV in St. Petersburg, Russia. PloS one. 2018;13(11):e0207402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roth A, Tran N, Piecara B, Welles S, Shinefeld J, Brady K. Factors Associated with Awareness of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Among Persons Who Inject Drugs in Philadelphia: National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 2015. AIDS Behavior. 2018:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng B, Yang X, Zhang Y, Dai J, Liang H, Zou Y, et al. Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among female sex workers: A cross-sectional study in China. HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care. 2012;4:149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ye L, Wei S, Zou Y, Yang X, Abdullah AS, Zhong X, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis interest among female sex workers in Guangxi, China. PloS one. 2014;9(1):e86200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walters SM, Reilly KH, Neaigus A, Braunstein S. Awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among women who inject drugs in NYC: the importance of networks and syringe exchange programs for HIV prevention. Harm reduction journal. 2017;14(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peitzmeier SM, Tomko C, Wingo E, Sawyer A, Sherman SG, Glass N, et al. Acceptability of microbicidal vaginal rings and oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among female sex workers in a high-prevalence US city. AIDS care. 2017;29(11):1453–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson T, Huang A, Chen H, Gao X, Zhang Y, Zhong X. Predictors of willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among female sex workers in Southwest China. AIDS care. 2013;25(5):601–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ortblad KF, Chanda MM, Musoke DK, Ngabirano T, Mwale M, Nakitende A, et al. Acceptability of HIV self-testing to support pre-exposure prophylaxis among female sex workers in Uganda and Zambia: results from two randomized controlled trials. BMC infectious diseases. 2018;18(1):503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mack N, Evens EM, Tolley EE, Brelsford K, Mackenzie C, Milford C, et al. The importance of choice in the rollout of ARV-based prevention to user groups in Kenya and South Africa: a qualitative study. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17(3 Suppl 2):19157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bazzi AR, Yotebieng KA, Agot K, Rota G, Syvertsen JL. Perspectives on biomedical HIV prevention options among women who inject drugs in Kenya. AIDS care. 2017:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Restar AJ, Tocco JU, Mantell JE, Lafort Y, Gichangi P, Masvawure TB, et al. Perspectives on HIV Pre- and Post-Exposure Prophylaxes (PrEP and PEP) Among Female and Male Sex Workers in Mombasa, Kenya: Implications for Integrating Biomedical Prevention into Sexual Health Services. AIDS education and prevention : official publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2017;29(2):141–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reza-Paul S, Lazarus L, Doshi M, Hafeez Ur Rahman S, Ramaiah M, Maiya R, et al. Prioritizing Risk in Preparation for a Demonstration Project: A Mixed Methods Feasibility Study of Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PREP) among Female Sex Workers in South India. PloS one. 2016;11(11):e0166889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garfinkel DB, Alexander KA, McDonald-Mosley R, Willie TC, Decker MR. Predictors of HIV-related risk perception and PrEP acceptability among young adult female family planning patients. AIDS care. 2017;29(6):751–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stein M, Thurmond P, Bailey G. Willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among opiate users. AIDS and behavior. 2014;18(9):1694–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shrestha R, Karki P, Altice FL, Huedo-Medina TB, Meyer JP, Madden L, et al. Correlates of willingness to initiate pre-exposure prophylaxis and anticipation of practicing safer drug- and sex-related behaviors among high-risk drug users on methadone treatment. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2017;173:107–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Escudero DJ, Kerr T, Wood E, Nguyen P, Lurie MN, Sued O, et al. Acceptability of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PREP) Among People Who Inject Drugs (PWID) in a Canadian Setting. AIDS and behavior. 2015;19(5):752–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roth AM, Aumaier BL, Felsher MA, Welles SL, Martinez-Donate AP, Chavis M, et al. An Exploration of Factors Impacting Preexposure Prophylaxis Eligibility and Access Among Syringe Exchange Users. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2018;45(4):217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pines H, Strathdee S, Hendrix C, Bristow C, Harvey-Vera A, Magis-Rodríguez C, et al. Oral and vaginal HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis product attribute preferences among female sex workers in the Mexico-US border region. International journal of STD AIDS. 2019;30(1):45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wanyenze RK, Musinguzi G, Kiguli J, Nuwaha F, Mujisha G, Musinguzi J, et al. “When they know that you are a sex worker, you will be the last person to be treated”: Perceptions and experiences of female sex workers in accessing HIV services in Uganda. BMC international health Human Rights Quarterly. 2017;17(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eakle R, Gomez GB, Naicker N, Bothma R, Mbogua J, Cabrera Escobar MA, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and early antiretroviral treatment among female sex workers in South Africa: Results from a prospective observational demonstration project. PLoS medicine. 2017;14(11):e1002444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mboup A, Béhanzin L, Guédou FA, Geraldo N, Goma - Matsétsé E, Giguère K, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy and daily pre - exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among female sex workers in Cotonou, Benin: a prospective observational demonstration study. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2018;21(11):e25208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cowan FM, Davey C, Fearon E, Mushati P, Dirawo J, Chabata S, et al. Targeted combination prevention to support female sex workers in Zimbabwe accessing and adhering to antiretrovirals for treatment and prevention of HIV (SAPPH-IRe): a cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet HIV. 2018;5(8):e417–e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Chaipung B, et al. Factors associated with the uptake of and adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in people who have injected drugs: an observational, open-label extension of the Bangkok Tenofovir Study. The lancet HIV. 2017;4(2):e59–e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. The impact of adherence to preexposure prophylaxis on the risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs. AIDS (London, England). 2015;29(7):819–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prüss-Ustün A, Wolf J, Driscoll T, Degenhardt L, Neira M, Calleja JMG. HIV due to female sex work: regional and global estimates. PloS one. 2013;8(5):e63476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.UNAIDS. UNAIDS guidance note on HIV and sex work. UNAIDS; Geneva; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li J, Berg CJ, Kramer MR, Haardörfer R, Zlotorzynska M, Sanchez TH. An Integrated Examination of County-and Individual-Level Factors in Relation to HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Awareness, Willingness to Use, and Uptake Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in the US. AIDS behavior. 2018:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bekker L-G, Johnson L, Cowan F, Overs C, Besada D, Hillier S, et al. Combination HIV prevention for female sex workers: what is the evidence? The Lancet. 2015;385(9962):72–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Friend DR, Clark JT, Kiser PF, Clark MR. Multipurpose prevention technologies: products in development. J Antiviral research. 2013;100:S39–S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pinto RM, Berringer KR, Melendez R, Mmeje O. Improving PrEP implementation through multilevel interventions: a synthesis of the literature. AIDS Behavior. 2018;22(11):3681–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bailey JL, Molino ST, Vega AD, Badowski M. A Review of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: The Female Perspective. Infectious diseases therapy. 2017;6(3):363–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Benítez-Gutiérrez L, Soriano V, Requena S, Arias A, Barreiro P, de Mendoza C. Treatment and prevention of HIV infection with long-acting antiretrovirals. Expert review of clinical pharmacology. 2018;11(5):507–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Romano JW, Van Damme L, Hillier S. The future of multipurpose prevention technology product strategies: understanding the market in parallel with product development. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics Gynaecology. 2014;121:15–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Patterson KB, Prince HA, Kraft E, Jenkins AJ, Shaheen NJ, Rooney JF, et al. Penetration of tenofovir and emtricitabine in mucosal tissues: implications for prevention of HIV-1 transmission. Science translational medicine. 2011;3(112):112re4–re4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoornenborg E, Krakower DS, Prins M, Mayer KH. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for MSM and transgender persons in early adopting countries. Aids. 2017;31(16):2179–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Karki P, Shrestha R, Huedo-Medina TB, Copenhaver M. The impact of methadone maintenance treatment on HIV risk behaviors among high-risk injection drug users: a systematic review. Evidence-based medicine public health. 2016;2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wong K-h, Lee S-s, Lim W-l, Low H-k. Adherence to methadone is associated with a lower level of HIV-related risk behaviors in drug users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24(3):233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shrestha R, Copenhaver M. Exploring the Use of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Prevention Among High-Risk People Who Use Drugs in Treatment. Frontiers in Public Health. 2018;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shrestha R, Altice F, Karki P, Copenhaver M. Developing an integrated, brief biobehavioral HIV prevention intervention for high-risk drug users in treatment: The process and outcome of formative research. Frontiers in Immunology. 2017;8(MAY). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goldenberg SM, Montaner J, Duff P, Nguyen P, Dobrer S, Guillemi S, et al. Structural barriers to antiretroviral therapy among sex workers living with HIV: findings of a longitudinal study in Vancouver, Canada. AIDS behavior. 2016;20(5):977–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cornelius T, Jones M, Merly C, Welles B, Kalichman MO, Kalichman SC. Impact of food, housing, and transportation insecurity on ART adherence: a hierarchical resources approach. AIDS care. 2017;29(4):449–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.