Abstract

Background

Final-year nursing students in Spain augmented the health care workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Purpose

To understand the lived experience of nursing students who joined the health care workforce during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak (March–May 2020).

Method

Qualitative content analysis of the reflective journals of 40 nursing students in Spain.

Findings

The analysis identified four main themes: 1) Willingness to help; 2) Safety and protective measures: Impact and challenges; 3) Overwhelming experience: Becoming aware of the magnitude of the epidemic; and 4) Learning and growth.

Discussion

The wish to help, the sense of moral duty, and the opportunity to learn buffered the impact of the students' lived experience. Despite the challenges they faced, they saw their experiences as a source of personal and professional growth, and they felt reaffirmed in their choice of career. Promoting opportunities for reflection and implementing adequate support and training strategies is crucial for building a nursing workforce that is capable of responding to future health crises.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Nursing students, Nursing curricula, Reflective journals, Professional growth

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is the most serious global health crisis this century, with over 105.6 million confirmed cases and 2.3 million deaths worldwide, according to data for February 08, 2021 published by the World Health Organization (2021). Health systems responded to the crisis by transforming hospitals into COVID-19 units and implementing measures to control the spread of the virus. One of the first measures to be introduced in countries such as Canada (Dewart et al., 2020), Spain (Collado-Boira et al., 2020; Monforte-Royo & Fuster, 2020), the UK (D. Jackson et al., 2020; Swift et al., 2020), and the USA (Intinarelli et al., 2020), was the suspension of clinical placements for nursing students. Paradoxically, some countries, such as Spain and the UK, also established a voluntary initiative allowing final-year nursing students to join the nursing workforce, which was stretched to its limits by the rapid spread of the virus. This study explores the experiences of final-year nursing students in Spain who volunteered and worked alongside frontline staff during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (March–May 2020).

Literature review

Voluntary initiatives of this kind have been described in Hong Kong (Heung, Wong et al., 2005; Thompson, 2003) and Singapore (Docking, 2003) in the context of the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and in Saudi Arabia during the outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2014 (Elrggal et al., 2018). Although some authors have questioned the advisability of using nursing students in this way and have highlighted the risks it entails (Dewart et al., 2020; Hayter & Jackson, 2020), research suggests that students themselves tend to express a strong willingness to work during a health crisis (Downes, 2015; Edwards et al., 2019; Elrggal et al., 2018; Heung et al., 2005) and have a positive attitude towards doing so (Chilton et al., 2016; Etokidem et al., 2018; Natan et al., 2015). The situation is complicated, however, when nursing students or the persons they live with are in an at-risk group, as they may feel pressured not to volunteer and guilty as a result of this decision (Swift et al., 2020).

Research conducted in the context of previous epidemics suggests that health professionals can be affected in a variety of ways. Studies have found that working during a health crisis led to anxiety, an increased incidence of depression, fear, sleep disturbances, post-traumatic stress, and psychosomatic symptoms, among other problems (Chung et al., 2005; Honey & Wang, 2013; Khalid et al., 2016), with nurses being the most affected (Lai et al., 2020). The co-existence of positive and negative feelings has also been described. For example, Kim (2018) explored nurses' experiences of caring for patients during the MERS outbreak in South Korea and found that in addition to stress, fear, fatigue, and feeling alone, they also reported feeling useful and that they had grown professionally. In the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic, a qualitative study by Sun et al. (2020) found that alongside negative feelings, nurses also perceived a degree of wellbeing, psychological growth, feelings of gratitude for the support received, and a stronger sense of professional identity.

Few studies, however, have examined the impact on nursing students of caring for patients during a pandemic. Wong et al. (2004) investigated the psychological responses of healthcare students to the 2003 SARS outbreak and found that perceived stress was higher among nursing than medical students. In the context of the same epidemic, a qualitative study conducted in Hong Kong reported that nurses saw the experience of caring for patients as an opportunity to affirm their professional identity and for personal growth (Heung et al., 2005). In the USA, Edwards et al. (2019) analyzed the reflective journals of eight nursing students whose clinical placement coincided with the admission of an Ebola patient to the hospital. The students described a range of emotions, both positive and negative, in response to this experience. A recent study conducted in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic used an open-ended online questionnaire to explore the opinions and feelings of final-year medical and nursing students who had joined the health care workforce. The students' main concern was the risk of infection, but the large majority of them felt a duty to volunteer (Collado-Boira et al., 2020). Although the three qualitative studies conducted to date provide important information, they each focus on specific aspects rather than nursing students' experiences as a whole.

Spain has been one of the European countries most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and as soon as the magnitude of the crisis became apparent the government established a voluntary initiative allowing final-year nursing students to join the health care workforce as auxiliary staff in remunerated positions. Those who did so entered a situation of organizational chaos, and they had to forego the usual study-to-work transition (Clark & Springer, 2012). None of these nursing students had received training in relation to pandemics, and they would never have been exposed to such high rates of patient mortality.

The aim of this study was to describe the lived experience of nursing students who joined the health care workforce during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak (March–May 2020) in Spain. To this end, we carried out a qualitative content analysis of the reflective journals they kept during this time.

Method

Design

This was a qualitative study in which we gathered data from final-year nursing students who completed a reflective journal during the 7–9 weeks they worked alongside frontline staff during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Context

When Spain first entered lockdown in March 2020, all clinical placements for student nurses were suspended indefinitely. However, due to the severity of the crisis and the pressures on the health system, the Spanish government also established a voluntary initiative allowing final-year nursing students to join the workforce as remunerated auxiliary staff. Those who did so worked alongside frontline health professionals, performing tasks consistent with their level of training under the supervision of a registered nurse. This situation also meant that Spanish universities had to adapt course requirements so that final-year nursing students could complete their training and graduate on schedule (in June). Theory classes did not pose a problem as they could be offered online. With regard to clinical placements, a number of options were proposed, one of which was to recognize the hours students worked as auxiliary staff as counting towards what would have been their final practicum, provided that clinical supervision was offered and that students kept a reflective journal throughout this time. In this way, final-year students were able to complete their training while simultaneously augmenting the nursing workforce during the health crisis. Those final-year students who did not volunteer to join the nursing workforce were assigned other learning activities and were also required to keep a reflective journal.

Sample

Participants were final-year nursing students who, between March and May 2020 and in response to the COVID-19 crisis, worked in an auxiliary role alongside frontline staff.

Inclusion criteria

Volunteered to join the nursing workforce during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak (March–May 2020), and signing informed consent for the analysis of their reflective journals once their final grade had been awarded. No exclusion criteria were established.

Procedure and data collection

All students who, in March 2020, had their final clinical placement suspended due to the COVID-19 crisis were assigned an academic mentor from among faculty of the nurse education program at our university, and they also had a weekly online tutorial (in groups of 6–8) in which they reflected on their experiences during the COVID-19 outbreak. Students could also access emotional support from staff and/or peers through an online community set up within the university. This was the case for all final-year students, regardless of whether they volunteered to join the nursing workforce or were assigned other learning activities in lieu of the practicum. The role of the academic mentor was two-fold: To support students through this final stage of their training, which was now taking place under exceptional circumstances, and to assess the development of their professional competences, thus enabling a final grade to be awarded. With the aim of promoting reflection and critical thinking, all our final-year students were also required to keep a reflective journal during this time. Reflective journals allow nursing students to record their experiences and learning during clinical placements (Mirlashari et al., 2017). They have been used as a tool for promoting learning and critical thinking, and also as source material in the analysis of the meanings that students ascribe to their experience (Brown Tyo & McCurry, 2019; Kuo et al., 2011; Ruiz-López et al., 2015). In addition, they have been considered a useful self-care technique for both students and health professionals during crises (Craft, 2005), and this in particular provided the rationale for their use here. The reflective journals were recorded electronically as they formed part of the material that our students had to submit (through an online platform) for assessment. Students were not given any direction about how to complete their journal because we wanted them to record whatever aspects of their lived experience they considered to be important.

After first obtaining approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, academic mentors informed students about the study, invited them to participate, and sought consent to analyze their reflective journals for research purposes once their final grade had been awarded and made public. In this way, we ensured that participation was voluntary and that students did not feel coerced into accepting. The material that is discussed in this paper comes solely from the reflective journals of students who had volunteered to join the nursing workforce and who gave informed consent for analysis of their journals. All these journals were coded for anonymity and only the principal investigator had access to the students' identity.

Analysis

The anonymized journals were first analyzed using an inductive method. Six researchers, split into two groups, read and re-read the text of five journals to gain a broad overview of the content and to identify key concepts as units of analysis. The two groups then met to discuss their results and to agree on the coding system that would be used to identify themes and sub-themes in the material. The proposed analytical framework was then agreed with all members of the research team in an attempt to minimize possible bias. The team as a whole then participated in analyzing the remaining journals using this framework. Throughout this process the researchers remained open to the possibility that new categories might emerge from the material. After analyzing and classifying 624 units of analysis, the research team met to discuss the results obtained. On a more interpretative level of analysis, and taking into account all the themes, sub-themes, codes, and selected quotations, one of the researchers then re-examined the data in order to develop an explanatory model of students' experiences. This model was also discussed and agreed by the whole of the research team.

Rigor and trustworthiness of the analysis

Rigor and trustworthiness were established according to the criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Regarding credibility, the researchers who analyzed the journals first worked independently and then discussed their interpretations in a series of joint meetings so as to enable triangulation of data. We also achieved data saturation, continuing until all 40 journals had been analyzed so as to ensure that no new themes emerged. In order to ensure the transferability and dependability of our findings we clearly describe the participants and the context in which data were collected. Confirmability is supported by the use of numerous verbatim quotations and the description of the procedure followed.

Ethical issues

Permission to conduct the study was granted by the Executive Board of the Department of Nursing and it was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (INF-2020-04).

Findings

A total of 50 nursing students who were undertaking their final clinical placement volunteered to join the health care workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic (58.8% of students enrolled in the final clinical practicum). Forty of these students (80%) consented to their reflective journals being used for this study. They ranged in age from 21 to 46 years (mean 24.65, SD 5.44), and 87.5% were female (n = 35). The students were assigned to 25 different healthcare settings across the region of Catalonia (north-east Spain).

Analysis of the reflective journals revealed four main themes that described students' experiences while working during the COVID-19 outbreak. Table 1 provides an overview of the four themes, together with their corresponding sub-themes, categories, and illustrative quotations. Additional quotations from the students' journals are available as supplementary material.

Table 1.

Overview showing the main themes, sub-themes, and categories, along with illustrative quotations, that describe the experiences of final-year nursing students who joined the health care workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Main themes | Sub-themes | Categories | Quotations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness to help | Factors that influenced the decision to join the health care workforce during the pandemic | Wanting to help | S9: “When I saw how things were unfolding, I decided I wanted to do my bit and help out in a hospital.” |

| Moral duty to help | S7: “…and with all that was going on, I decided to start contacting different hospitals to offer my help, I just couldn't sit there at home seeing what was happening.” | ||

| Moral dilemma about helping/not helping | S23: “So there's the dilemma: either I sign up and put myself and my family at risk, or I don't sign up because of those risks, but then I'm not doing my bit and helping to manage the crisis.” | ||

| Implications of working in the health system during the crisis | Ensuring the safety of family members | S3: “It's not easy, isolating yourself in an apartment and living alone for the first time. It's hard to live apart from those you love the most so as to avoid the risk of taking the virus home and infecting your loved ones. It's difficult to start living physically alone when you know that you have to face a new and unfamiliar situation.” | |

| Emotional impact of separation from family | S14: “Not being able to hug my parents after a hard day, and having to keep to my own room all the time was one of the hardest things for me, because I'm a really family person who's used to being close to people.” | ||

| Safety and protective measures: Impact and challenges | Impact of a shortage of PPE and health resources | Shortage of material and inadequate resources | S15: “We had no gowns or visors or goggles. Just an FFP2 that had to last two weeks and a surgical mask.” |

| Distress caused by the shortage of resources | S22: “We were furious, most of us disheartened. They weren't protecting us in any way, and most of us had vulnerable family members at home.” | ||

| Risk of infection | S6: “It was when I was putting on the PPE for the nightly round that I realized that the slightest mistake could mean that we'd get infected.” | ||

| Response of society and health professionals | S37. “I remember that we started to be creative, and like everybody, we looked for ways of protecting ourselves. We ended up making protective gowns out of garbage bags.” | ||

| Ethical dilemmas due to the lack of resources | S7: “The cruelty of this virus was hard to take, all those people who weren't given the chance to live because of a lack of respirators and ICU beds.” | ||

| Experiences and learning in the use of PPE and application of safety measures | Correct use of PPE | S9: “They took me through how to put on the PPE properly, as I didn't know much about the correct procedures for ensuring that both my patients and I myself were protected.” | |

| Variability in the use of PPE | S9: “The first nurse I worked with would change her PPE to avoid possible infections, but the second one who taught me, she didn't always change it so as not to waste material.” | ||

| Providing more personalized care: Barriers and facilitators | S10: “The human side of our profession, it was affected by having so little time to interact with patients, and by the PPE, which means your face is almost entirely covered.” | ||

| Constant organizational changes | Changing protocols | S19: “Every time a new study appeared, the protocols and guidelines changed.” | |

| Workload | S7: “Health professionals worked more shifts so as to deal with the growing number of patients.” | ||

| Overwhelming experience: Becoming aware of the magnitude of the epidemic | Lack of awareness in the early stages of the pandemic | Initial skepticism | S13: “The uncertainty that surrounded COVID-19 at first, due to not understanding the mechanism of transmission, how to treat it, what caused it, and even whether you might be infected or infect others [...] that faded after a couple of months.” |

| Lack of experience with pandemics | S29: “I came to realize that we weren't prepared for a disease of this magnitude, despite having one of the best health systems in the world.” | ||

| Overwhelming situation | Impact of the number of deaths | S8: “The situation was desperate during the first few weeks, you'd have four patients dying on every shift and none showing signs of clinical improvements. It was so sad, but you also had the satisfaction of having helped and having grown as a person.” | |

| Initial experience as an auxiliary health worker | S10: “The fact that I was a student didn't go down well with my colleagues. It's not what the nurses on the unit were expecting.” | ||

| Feeling afraid and unsafe at first, due to inexperience | S9: “Afraid of making a mistake when caring for a patient or of getting it wrong in the eyes of colleagues. When you're a student you still have the luxury of being able to make a mistake and of saying so, although it can also be scary.” | ||

| Array of emotions | S7: “I'd never felt so many different feelings at the same time: fear, anger, impotence, sorrow, nervousness, worry, a sense of injustice… so many emotions” | ||

| A semblance of normality returns | Health services return to normal, and adapting to the new normal | S14: “Once things started getting back to normal we closed the temporary ICU and got the operating rooms up and running again for surgery. In this new normal, we still apply all the safety measures to protect both patients and staff and to ensure the quality of care.” | |

| Learning and growth | Change of role from student to professional | Adapting to the new role | S26: “It was a while before it sank in that I was no longer on placement, that I didn't have to have somebody else's approval, although neither was anybody there to bail me out.” |

| Learning opportunities | New knowledge, skills, and competences | S16: “[...] it's really helped me to gain confidence, to take decisions, to grasp new concepts, to interact and communicate effectively with patients.” | |

| Learning the importance of teamwork | S32:“[...] that they trust you, that you feel part of a team, an essential part of it, that they want to know your opinion and, what's more, that you enjoy what you do, you can't ask for anything else in a job.” | ||

| Need for support | Support from the health team, united and together | S33: “They work as one, everybody pulling together and helping each other. Teams that are like a small family [...] Even in the ICU, the support from colleagues is unconditional […] I can't tell you how grateful I am to all my colleagues.” | |

| Support and presence of mentors and classmates | S3: “I would like to thank all the mentors for offering us all the help we needed, both academically and personally, especially these last few months. They gave us strength and offered encouragement on those days when it was tough to face another day of caring for COVID patients.” | ||

| Support from family | S21: “What comforted me when I was most down was being able to come home and find my family in good health.” | ||

| Personal and professional growth | Vicarious growth | S7: “I have to say that it's been the best learning experience I've ever had. I've grown both personally and professionally, I have a deeper knowledge of myself, I've known how to adapt to this difficult situation full of adversities.” | |

| Professional identity | Reaffirming the choice of profession | S14: “I'm really proud of having chosen nursing as a profession, now more than ever, because helping others is gratifying, and personally it makes me feel better about myself [...] I'm more certain with each day that passes that I couldn't have chosen a better profession to dedicate my life to.” | |

| Value and growth of the profession. Visibility of the profession on a societal level. |

S23: “I think that despite all we've been through, this crisis has served to shine a light on our profession and on the really hard work that health professionals do.” | ||

| Change in the hierarchy of values | Change in priorities/values: valuing what really matters | S14: “I would like to think that we will come out of this both stronger and more together, and I hope that we come to recognize the importance of what really matters: health.” |

Willingness to help

The first theme to emerge was the willingness to help and it was common to all the students who joined the health care workforce during the crisis. This theme comprised two sub-themes:

Factors that influenced the decision to join the health care workforce during the pandemic

Most of the students said that their decision to join the health care workforce was driven by the desire to help and by the moral duty to do so.

S1: “[…] when the hospitals became overwhelmed, all I could think of was that I wanted to help. I didn't know if I was up to the task, but I wanted to help, I wanted to be there.”

Nevertheless, they also experienced strong mixed feelings, since the wish to help was accompanied by doubts about their preparedness and the awareness that they risked exposing themselves and their family members to infection. The latter left them with a moral dilemma as to whether their family's safety was more important than their own desire to help out.

S2: “Sure, I wasn't trained to deal with a situation like this, but at the time I felt a moral duty to help and that seemed more important than all the risks.”

Implications of working in the health system during the crisis

Participants referred to the importance of ensuring their family's safety, which for many students meant going to live in accommodation made available by the hospital, or completely changing the kinds of contact they had with others at home.

S3: “[…] It's hard to live apart from those you love the most so as to avoid the risk of taking the virus home and infecting your loved ones […].”

The forced separation from family had an emotional impact on many students, who then had to adapt to their new living circumstances.

S4: “I left home in a way that I'd never imagined, so alone and vulnerable. I must have regretted it a hundred times, but more than that I felt really proud of myself.”

Safety and protective measures: impact and challenges

Another theme common to all the journals was personal safety and the safety of others. Here there were three sub-themes.

Impact of a shortage of personal protective equipment and health resources

The magnitude of the pandemic quickly led to a shortage of health resources, and students referred in their journals to a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), and in some cases to defective or inadequate material. This produced distress, feelings of impotence, fear, and outrage. The lack of PPE made students aware of the risk that they or others around them might become infected, and when this occurred it left them with feelings of guilt.

S5: “They told us that the hospital didn't have quality certificates for the masks. You were supposed to get a new mask each week, but because I wasn't permanent staff I went more than a month with the same one. This just made you more afraid.”

Many participants highlighted how society and health professionals were quick to respond to the shortage of PPE.

S2: “[…] there were some one-off initiatives, solidarity on the part of individuals, organizations, and companies. People making PPE and donating it.”

Most of the nursing students described ethical dilemmas arising from the fact that the lack of resources meant that not all critical patients could receive the care they needed. Not being able to intubate a patient because there were not enough mechanical ventilators to go round was one of the most challenging experiences.

S7: “I couldn't stop thinking about all those people over 70 who needed a respirator, but who didn't meet the criteria for intubation, and so they were never even given the chance to fight for their life [...]”

Experiences and learning in the use of PPE and application of safety measures

All the participants were aware that proper use of PPE was important for their own safety and that of others. At the same time, they commented how difficult it was to wear PPE for long periods of time.

S8: “Wearing PPE was hard but essential for our safety and that of others around us. But it's uncomfortable and exhausting, you can't see well because your goggles steam up, your head aches, you feel suffocated after hours with it on.”

Many students referred to their lack of knowledge about infection control and prevention and the use of PPE, and some of them also observed differences in the clinical practice of other professionals.

S9: “I didn't know much about the correct procedures for ensuring that both my patients and I myself were protected.”

The use of PPE and the isolation measures were seen as barriers to more personalized patient care. The PPE made it hard for patients to recognize health professionals, and it was difficult to communicate properly. In addition, the need to limit exposure to the virus meant that nurses could spend little time with patients, increasing the latter's sense of being alone, including at the end of life. Indeed, the fact that patients were alone and that some died in isolation was one of the experiences that most impacted the nursing students.

S11: “What most affected me was that the patient had to die alone, with nobody at his side, neither his family nor we could be there.”

However, some of the students also referred to things that were done in an attempt to bring a more human touch to care and to make patients feel less alone, for example, setting up video calls with relatives, reading letters to patients, and making greater use of non-verbal communication.

Constant organizational changes

The students highlighted how clinical protocols were constantly being updated as the number of infections increased, and changes also occurred at the wider service and organizational level.

S12: “[...] some of the protocols were changed every 2-3 days depending on the material that was available.”

Due to the magnitude of the epidemic, the health system was forced to make various structural changes such as setting up additional areas for critical care patients and turning wards from different specialties into COVID-19 units. In this context, many students worked long hours across shifts in order to provide nursing cover. Although they acknowledged feeling overloaded, they also noted the high level of teamwork and support among different professionals.

S1: “[…] the whole hospital was COVID-19. All the different wards, surgical, cardiology, orthopedics, that all went, all the usual specialties disappeared. Nobody was a trauma consultant, a surgeon or a cardiology nurse anymore, we were all the same. We were a single team, more united than ever, all working in the same way and with the same goal [...] You never knew who it was helping you put on the PPE. But it didn't matter, we all helped each other.”

Overwhelming experience: becoming aware of the magnitude of the epidemic

This theme emerged with three sub-themes. As the virus spread, nursing students and health professionals became aware of the magnitude of the epidemic they were facing, and its consequences.

Lack of awareness in the early stages of the pandemic

The nursing students all referred to how, initially, there was little understanding and considerable skepticism, both personally and in society as a whole, with regard to the seriousness of the pandemic. They attributed this to a lack of knowledge and awareness, since this was the first major epidemic in Spain since the 1918 flu pandemic.

S6: “Nobody imagined what we would end up having to go through. At the beginning I didn't think it was anything to worry about, I thought it was just like the flu.”

Overwhelming situation

The large number of fatalities had an enormous impact on the nursing students, and not being able to prevent so many deaths was regarded as a desperate situation. In fact, the students noted that several weeks into the pandemic, death had become normalized.

S14: “I think that death has become normalized, and that is hard to take, because it isn't normal nowadays for so many thousands of people to have died in our country and around the world.”

The students referred to the fact that they had joined the nursing workforce at the worst point in the health crisis, and so for many of them their first experience of a real working environment was gained in a situation of organizational chaos. Their arrival and assignment was poorly coordinated, and some of their professional colleagues were unclear about the role that the students were meant to fulfill. However, over time and through the work they did, they managed to gain the trust of qualified staff.

S15: “When I arrived there were 15 other students who were also waiting to be assigned. It was all a bit chaotic, they weren't sure what to do with us and so they asked us where we'd been on placement, to get some idea... then they let me loose, still a fledgling.”

The students described feeling scared and insecure about facing an unfamiliar working environment for the first time. More specifically, there was a fear of making a mistake with some procedure and of not being up to the job.

S16: “The first thing I felt was fear, well, not fear as such, but that I was entering a situation that merited respect, that's what I felt when I walked onto the ward, it was a hostile place, one that I wasn't familiar with, and I had to work as a nurse even though I hadn't finished my training... lots of things scared me, I felt unsure about so many things.”

The students referred to the wide range of emotions they felt, including fear, insecurity, nervousness, and the need to cry, although the little things they achieved also made them happy.

S17: “Fear, impotence, anger, distress, a sense of being all alone... and then happy about the little successes. Today we discharged a patient, but five others have died. We went from feeling happy to being distraught in a matter of minutes. A sea of uncontrollable emotions.”

A semblance of normality returns

Once the number of COVID-19 patients, and especially those requiring intensive care, began to fall, the nurses noted how clinical services returned more or less to normal, which they experienced as reassuring, as a respite. They also reflected on the process of adapting to the new normal and having to live with the virus.

S18: “Of the four new ICUs that were created, there's only one left. Outpatient clinics have opened again and the operating rooms are up and running. This is reassuring, it's a respite, and I think all the staff feel that [...].”

Learning and growth

This theme comprised six sub-themes that reflected the students' learning experiences during the crisis.

Change in role from student to professional

Those final-year students who had joined the nursing workforce saw their role change to that of a professional nurse.

S20: “But until you find yourself on your own in a hospital without a mentor, you don't realize how much responsibility you have and the enormous role that nurses play […].”

Learning opportunities

The students said that working in the health system during the pandemic was an opportunity to learn, to acquire new competences, and to improve their clinical and communication skills and become more confident in their decision making.

S12: “I became more independent and more a part of my working environment. My critical thinking, in terms of my way of working, has improved, and I see the patient more holistically [...]. I've brushed up my knowledge and also acquired a new understanding of critical care, about ways of ventilating patients, interpreting blood gas analysis, placing a patient in a prone position, inserting a central catheter [...].”

Some of the students highlighted what they had learned by working as part of the nursing team, which they saw as fundamental to the profession and to patient care.

S21: “[…] thanks to teamwork and the organization of all staff, we were able to perform all these tasks day after day. I think this is fundamental to our profession […].”

Need for support

Most of the students mentioned the support they received from the team to which they were assigned. They felt this helped them to integrate and they highlighted the importance of interpersonal relationships and the bond that was created.

S22: “After a while we created a WhatsApp group for team members that we used to support each other and to send messages of encouragement. There was a real sense of communion, of togetherness. It didn't matter what job title or experience you had, everybody helped out in whatever way they could and did their bit to keep the group together.”

The university organized weekly tutorials to support the students' learning during this period. Our participants were grateful for this support and saw it both as facilitating their learning and helping them to cope.

S23: “And also, I think being able to share things with other students helps you to learn. You can share experiences and different points of view, and you can learn from what others have been through.”

They also mentioned the support they received from family.

S24: “My family was really worried, they called me all the time, and that gave me a lot of strength to carry on.”

Personal and professional growth

Although many students referred to how difficult the situation had been, there was also a sense of vicarious growth, insofar as the experience of others' adversity led them to feel that they had grown both personally and professionally.

S17: “During this time I've grown as a person, I've grown as a professional. I've cried, and a lot, more than I could have imagined... but I've grown, I've become strong, and more sensitive, I think I'm better now than before the pandemic. The pain has made me see how vulnerable we are. I'm aware of that pain and of the needs of others who are in pain.”

Professional identity

Their lived experience led the nursing students to reaffirm their choice of career and made them feel a sense of professional pride.

S3: “I think this pandemic has helped me discover, really discover, what this profession is about and the sense of nursing as a vocation. I've come to really love what I do, this job. I realize now, more and more, how much I LOVE this wonderful profession.”

The students also noted that the pandemic had led to greater public recognition and awareness of nursing, and some of them considered that the profession would emerge stronger from the crisis.

S25: “[...] the pandemic has made people much more aware of healthcare staff and key workers. In the media and on the streets, there's been recognition of what nurses have done during the health crisis.”

Change in the hierarchy of values

Their experiences during the pandemic produced in students a shift in priorities and in what they considered important.

S7: “When I got home I appreciated those little moments in life that I didn't appreciate before, like getting a hug from my partner or having a coffee with my best friend.”

Explanatory model

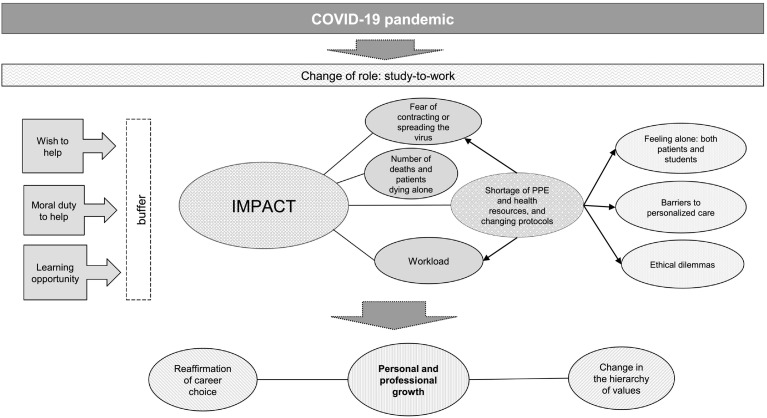

Having extracted these themes and sub-themes from the students' reflective journals we then re-analyzed the data as a whole. This enabled us to identify inter-relationships between the different themes and to propose an explanatory model (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Explanatory model of the experience of nursing students who joined the health care workforce during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Witnessing the pandemic aroused in students a strong wish to help, as well as a sense of moral duty to do so. Those who responded to the call for additional health workers and joined the nursing workforce thus underwent a rapid role change, from student to professional. Alongside the wish to help and the sense of moral duty, these students saw it as a learning opportunity, and these three factors helped to buffer the impact of their experiences on the frontline.

The impact they described was due primarily to four factors, two direct and two indirect. The two direct factors were the lack of resources, coupled with constantly changing protocols, and seeing large numbers of patients die, invariably alone. The two indirect factors were a consequence of the shortage of resources (including PPE), which generated both an excessive workload and a fear of becoming infected or of infecting family members. The lack of resources also created ethical dilemmas, and students experienced the need for PPE and isolation measures as a barrier to personalized care. In addition, it heightened the sense that both they and their patients were ultimately alone.

However, and acknowledging the support they received from academic mentors, other team members, and families, students came to see their experiences on the frontline as a source of personal and professional growth. They felt reaffirmed in their choice of career and achieved a new sense of what was really important to them in life.

Discussion

Analysis of the reflective journals kept by final-year nursing students who joined the health care workforce during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (March–May 2020) in Spain revealed four main themes. By considering the inter-relationships between themes and sub-themes we were able to propose an explanatory model describing the impact of their lived experience and the personal and professional growth that resulted from this.

One of the themes to emerge from the reflective journals was the students' wish to help, despite the fear and risk of becoming infected or of infecting others. A number of previous studies have explored students' willingness to work in response to the threat of different pandemics (Chilton et al., 2016; Natan et al., 2015; Osuafor et al., 2019; Tzeng & Yin, 2006; O. Yonge et al., 2007), and many of them have identified the moral duty to help as the main factor driving this willingness. Consistent with our findings here, a recent qualitative study by Collado-Boira et al. (2020) that explored the perceptions of final-year medical and nursing students in relation to the COVID-19 outbreak highlighted the students' willingness and sense of moral duty to help, despite the risks that this would entail. A study conducted in Nigeria in the context of Ebola virus disease (EVD) found that 45.8% of nursing students would not be willing to work in the EVD treatment center, while 41.8% indicated an unwillingness to volunteer in an EVD vaccine trial (Etokidem et al., 2018). However, the authors noted that these percentages were well below the 70% reported in another study in Nigeria, in which 70% of health care workers indicated an unwillingness to work in care units for Ebola patients (Iliyasu et al., 2015). As a possible explanation for this difference, Etokidem et al. (2018) suggest that students, with less clinical experience, are less afraid of contracting an infectious disease from patients than are their colleagues already in practice. In a different geographical context, Santana-López et al. (2019) explored the attitudes of Spanish health workers and nursing students to the threat of an influenza pandemic. They found that the willingness to work longer hours if necessary was greater among nursing students (69.1% vs. 52.8% of health workers). In addition, only 37.2% of health workers, compared with 62.5% of nursing students, said they would be willing to work alongside untrained staff during a pandemic. It is unclear whether the greater willingness to work reported by students was related to their relative inexperience.

Our analysis also revealed the enormous impact that working during the COVID-19 outbreak had on students. In particular, the shortage of PPE and of adequate health resources heightened their fear of contracting or spreading the virus. A recent systematic review by our group that examined all studies published to date on nursing students and pandemics likewise found that a lack of PPE and the fear of becoming infected or of infecting family members were key factors influencing students' willingness to work (Goni-Fuste et al., 2021). Another aspect that affected the students in our study was seeing patients die alone. We are unaware of any studies that have examined the impact of this experience among nursing students, although Shah et al. (2020) have recently described the psychological effects it can have on health professionals.

The nursing students in our study also described experiencing an array of different emotions. This is consistent with research that has examined the impact that working during infectious disease outbreaks has on healthcare workers, which also notes the negative effects it can have on their psychological wellbeing (Brooks et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020). Interestingly, however, qualitative studies that have explored the experience of nursing students during pandemics report certain positives alongside the negative effects. For example, Heung et al. (2005) interviewed 10 nursing students about their experiences of the 2003 SARS outbreak in Hong Kong and found that it had been perceived as an opportunity to affirm their professional identity and for personal growth. In the context of the MERS outbreak in Saudi Arabia, Stirling et al. (2015) developed an education program for nursing staff and students, which included establishing a helpline for students to address their concerns. The authors concluded that students became more resilient as a result of the initiatives introduced. Edwards et al. (2019) analyzed the reflective journals completed by eight nursing students who were on clinical placement in a hospital in Texas (USA) at the time a patient with EVD was admitted. In addition to fear, the students also referred to the opportunity to learn and to the realization that nursing was a calling.

Future research

Coupled with this previous research, our findings here lead us to speculate whether students' desire to help and relative inexperience may act as protective factors against more negative effects on their mental wellbeing. Testing this hypothesis will require longitudinal studies that monitor the medium- and long-term impact on nursing students of having joined the health care workforce during the pandemic.

Throughout their time on the frontline, the nursing students were provided with online support by their academic mentors. Mentoring through tutorials and the use of reflective journaling have been shown to be effective tools for promoting learning and facilitating reflective practice (Schön, 1983), including in crisis situations (Craft, 2005), and the experience of our students supports this. Alongside the training they received, we believe that these tools helped students to develop a more resilient attitude (Stirling et al., 2015) and to grow both personally and professionally. It also, in our view, helped to buffer the impact of their challenging experiences. Taylor et al. (2020) have recently argued for the importance of teaching empathy and resilience to nursing undergraduates, highlighting how both abilities are crucial to compassionate care, the need for which is underscored during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Resilience has been defined as “the ability of an individual to adjust to adversity, maintain equilibrium, retain some sense of control over their environment, and continue to move on in a positive manner” (D. Jackson et al., 2007). In the nursing context it has been linked to more empathic care and it is suggested that it prevents distress and burnout (Taylor et al., 2020). We believe that this issue merits more detailed investigation as it might help to explain why our nursing students described a sense of personal growth as a result of working during the pandemic. It may indeed be the case that resilience is what protects nursing professionals against compassion fatigue, distress, burnout, and mental health problems. Our findings overall support Taylor et al.'s (2020) call for nursing undergraduates to be taught the skills of resilience, although as we have already stated, longitudinal studies are now needed so as to monitor the medium- and long-term impact of having worked on the frontline during the COVID-19 pandemic while still technically a student. This should include exploration of whether these nurses' professional development was affected in any way by having missed out on the usual study-to-work transition. It would also be important to examine whether students and professional nurses use different coping mechanisms to deal with the potentially negative impact of their work. Finally, it is unclear whether, as some studies suggest (Chilton et al., 2016; Choi & Kim, 2016; Wu et al., 2009; O. Yonge et al., 2010), knowledge of infection control and prevention measures can help students to cope with and be willing to provide care during crises of this kind. Overall, a better understanding of the relationship between a lack of professional experience and a willingness to work during a health crisis will help to shed light on the mechanisms which may help to protect students' psychological wellbeing under challenging circumstances.

Implications for nursing education

Our findings suggest that strategies such as the use of reflective journaling and the availability of online mentoring, both of which encourage reflection on practice, can help nursing students to see their clinical placements as an opportunity for personal and professional growth, alongside whatever challenges they may encounter. Despite their limited experience, students expressed a willingness, a moral duty to help in response to a major health crisis. Accordingly, we would argue that allowing senior students to learn in complex care settings where they may be faced with high mortality and intense pressure could, provided they receive adequate support and supervision, strengthen their sense of professional identity and encourage them to see themselves as nurses even before they complete their training. Whatever the case, promoting opportunities for reflection and implementing adequate support and training strategies is crucial for building a nursing workforce that is capable of responding to future health crises.

Strengths and limitations

Although the final-year nursing students were all enrolled in the same university, they were employed across 25 different health facilities during the COVID-19 outbreak, thus ensuring variation in their experiences and, therefore, in the data obtained. Another strength of our study is that there were no guidelines or limitations on how students should complete or structure their reflective journals, and hence they were free to record whatever aspects of their lived experience they considered important. In addition, the framework for analyzing the journals was agreed upon by all members of the research team, thus helping to ensure homogeneity in the coding and interpretation. As regards limitations, the fact that our analysis is based on reflective journals rather than interviews with students means that certain aspects of their experience may have been missed or be lacking in detail. Neither have we had the opportunity to discuss our interpretation with the students and to request their feedback. Finally, the fact that all the students were enrolled in the same university means that our findings need to be corroborated through multi-center studies.

Conclusions

This study describes the experiences of final-year nursing students who joined the health care workforce during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain, prior to completing their training. These students missed out on the usual study-to-work transition and their reflective journals reveal how they were affected by the shortage of resources, the fear of contracting or spreading the virus, and by seeing patients die alone. However, the impact of these experiences was buffered by their willingness and sense of moral duty to help and by their ability to see the situation as a learning opportunity. Despite the challenges they faced, they saw their experiences as a source of personal and professional growth, and they felt reaffirmed in their choice of career. Promoting opportunities for reflection and implementing adequate support and training strategies is crucial for building a nursing workforce that is capable of responding to future health crises in our increasingly globalized world.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alan Nance for his contribution to translating and editing the manuscript.

Funding source

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (INF-2020-04).

Funding sources

No external funding.

Ethics committee approval

This work obtained the approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

| Author | Criteria 1 |

Criteria 2 |

Criteria 3 |

Criteria 4 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributed to conception or design | Contributed to acquisition, analysis, or interpretation | Drafted the manuscript | Critically revised the manuscript | Gave final approval | Agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy | |

| Martin-Delgado, L | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Goni-Fuste, B | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Alfonso-Arias, C | x | x | x | x | ||

| De Juan, MA | x | x | x | x | ||

| Wennberg, L | x | x | x | x | ||

| Rodríguez, E | x | x | x | x | ||

| Fuster, P | x | x | x | x | ||

| Monforte-Royo, C | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Martin-Ferreres ML | x | x | x | x | x | x |

References

- Brooks S., Dunn R., Amlôt R., Rubin G., Greenberg N. A systematic, thematic review of social and occupational factors associated with psychological outcomes in healthcare employees during an infectious disease outbreak. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2018;60(3):248–257. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Tyo M., McCurry M.K. An integrative review of clinical reasoning teaching strategies and outcome evaluation in nursing education. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2019;40(1):11–17. doi: 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton J.M., McNeill C., Alfred D. Survey of nursing students' self-reported knowledge of Ebola virus disease, willingness to treat, and perceptions of their duty to treat. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2016;32(6):487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. S., & Kim, J. S. (2016). Factors influencing preventive behavior against Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus among nursing students in South Korea. Nurse Education Today, 40, 168-172. doi:S0260-6917(16)00105-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chung B.P.M., Wong T.K.S., Suen E.S.B., Chung J.W.Y. SARS: Caring for patients in Hong Kong. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005;14(4):510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.M., Springer P.J. Nurse residents' first-hand accounts on transition to practice. Nursing Outlook. 2012;60(4):2. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado-Boira E.J., Ruiz-Palomino E., Salas-Media P., Folch-Ayora A., Muriach M., Baliño P. "The COVID-19 outbreak"-an empirical phenomenological study on perceptions and psychosocial considerations surrounding the immediate incorporation of final-year Spanish nursing and medical students into the health system. Nurse Education Today. 2020;92:104504. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft M. Reflective writing and nursing education. The Journal of Nursing Education. 2005;44(2):53–57. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20050201-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewart G., Corcoran L., Thirsk L., Petrovic K. Nursing education in a pandemic: Academic challenges in response to COVID-19. Nurse Education Today. 2020;92:104471. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docking P. SARS and the effect on nurse education in Singapore. Contemporary Nurse. 2003;15(1–2):5–8. doi: 10.5172/conu.15.1-2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downes E. Nursing and complex humanitarian emergencies: Ebola is more than a disease. Nursing Outlook. 2015;63(1):12–15. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C.N., Mintz-Binder R., Jones M.M. When a clinical crisis strikes: Lessons learned from the reflective writings of nursing students. Nursing Forum. 2019;54(3):345–351. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrggal M., Karami N., Rafea B., Alahmadi L., Al Shehri A., Alamoudi R.…Cheema E. Evaluation of preparedness of healthcare student volunteers against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Makkah, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Public Health (09431853) 2018;26(6):607–612. doi: 10.1007/s10389-018-0917-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etokidem A.J., Ago B.U., Mgbekem M., Etim A., Usoroh E., Isika A. Ebola virus disease: Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of nursing students of a Nigerian university. African Health Sciences. 2018;18(1):55–65. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v18i1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goni-Fuste B., Wennberg L., Martin-Delgado L., Alfonso-Arias C., Martin-Ferreres M., Monforte-Royo C. Experiences and needs of nursing students during pandemic outbreaks: A systematic overview of the literature. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2021;37:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayter M., Jackson D. Pre-registration undergraduate nurses and the COVID-19 pandemic: Students or workers? Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(17–18):3115–3116. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heung Y.Y., Wong K.Y., Kwong W.Y., To, S. S, Wong H.C. Severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak promotes a strong sense of professional identity among nursing students. Nurse Education Today. 2005;25(2):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey M., Wang W.Y. New Zealand nurses perceptions of caring for patients with influenza A (H1N1) Nursing in Critical Care. 2013;18(2):63–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2012.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliyasu G., Ogoina D., Otu A.A., Dayyab F.M., Ebenso B., Otokpa D.…Habib A.G. A multi-site knowledge attitude and practice survey of Ebola virus disease in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2015;10(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intinarelli, G., Wagner, L. M., Burgel, B., Andersen, R., & Gilliss, C. L. (2020). Nurse practitioner students as an essential workforce: The lessons of coronavirus disease 2019. Nursing Outlook, S0029-6554(20)30709–0. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jackson D., Bradbury-Jones C., Baptiste D., Gelling L., Morin K., Neville S., Smith G.D. Life in the pandemic: Some reflections on nursing in the context of COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(13–14):2041–2043. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D., Firtko A., Edenborough M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;60(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid I., Khalid T.J., Qabajah M.R., Barnard A.G., Qushmaq I.A. Healthcare workers emotions, perceived stressors and coping strategies during a MERS-CoV outbreak. Clinical Medicine & Research. 2016;14(1):7–14. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2016.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. Nurses' experiences of care for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus in South Korea. American Journal of Infection Control. 2018;46(7):781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C.L., Turton M., Cheng S.F., Lee-Hsieh J. Using clinical caring journaling: Nursing student and instructor experiences. The Journal of Nursing Research: JNR. 2011;19(2):141–149. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0b013e31821aa1a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N.…Hu S. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zeng L., Li Z., Mao Q., Liu D., Zhang L.…Chen L. Emergency trauma care during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2020;15(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s13017-020-00312-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y.S., Guba E.G. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- Mirlashari J., Warnock F., Jahanbani J. The experiences of undergraduate nursing students and self-reflective accounts of first clinical rotation in pediatric oncology. Nurse Education in Practice. 2017;25:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monforte-Royo, C., & Fuster, P. (2020). Coronials: Nurses who graduated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Will they be better nurses? Nurse Education Today, 94, 104536. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Natan M.B., Zilberstein S., Alaev D. Willingness of future nursing workforce to report for duty during an avian influenza pandemic. Research & Theory for Nursing Practice. 2015;29(4):266–275. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.29.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osuafor, G. N., Manyisa, Z. M., & Akinsola, H. A. (2019). Nursing students' perceptions and attitudes regarding Ebola patients in South Africa. Africa Journal of Nursing & Midwifery, 21(2), 1–17. doi:10.25159/2520-5293/6014.

- Ruiz-López M., Rodríguez-García M., Villanueva P.G., Márquez-Cava M., García-Mateos M., Ruiz-Ruiz B., Herrera-Sánchez E. The use of reflective journaling as a learning strategy during the clinical rotations of students from the faculty of health sciences: An action-research study. Nurse Education Today. 2015;35(10):26. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2015.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana-López, B. N., Santana-Padilla, Y. G., Martín-Santana, J. D., Santana-Cabrera, L., & Rodríguez, C. E. (2019). Beliefs and attitudes of health workers and nursing students toward an influenza pandemic in a region of Spain. [Creencias y actitudes de trabajadores sanitarios y estudiantes de enfermería de una región de España ante una pandemia de gripe] Revista Peruana De Medicina Experimental Y Salud Publica, 36(3), 481-486. doi:10.17843/rpmesp.2019.363.4371. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schön D.A. Basic Books, Inc.; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1983. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. [Google Scholar]

- Shah K., Kamrai D., Mekala H., Mann B., Desai K., Patel R.S. Focus on mental health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: Applying learnings from the past outbreaks. Cureus. 2020;12(3) doi: 10.7759/cureus.7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling B.V., Harmston J., Alsobayel H. An educational programme for nursing college staff and students during a MERS-coronavirus outbreak in Saudi Arabia. BMC Nursing. 2015;14(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s12912-015-0065-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N., Wei L., Shi S., Jiao D., Song R., Ma L.…Wang H. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. American Journal of Infection Control. 2020;48(6):592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift A., Banks L., Baleswaran A., Cooke N., Little C., McGrath L.…Williams G. COVID-19 and student nurses: A view from England. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(17–18):3111–3114. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor T., Thomas-Gregory A., Hofmeyer A. Teaching empathy and resilience to undergraduate nursing students: A call to action in the context of COVID-19. Nurse Education Today. 2020;94:104524. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D.R. SARS – Some lessons for nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2003;12(5):615–617. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng H.M., Yin C. Nurses' fears and professional obligations concerning possible human-to-human avian flu. Nursing Ethics. 2006;13(5):455–470. doi: 10.1191/0969733006nej893oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J.G., Cheung E.P., Cheung V., Cheung C., Chan M.T., Chua S.E.…Ip M.S. Psychological responses to the SARS outbreak in healthcare students in Hong Kong. Medical Teacher. 2004;26(7):657–659. doi: 10.1080/01421590400006572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2021). WHO Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Dashboard overview. Retrieved from https://covid19.who.int/.

- Wu C.J., Gardner G., Chang A.M. Nursing students' knowledge and practice of infection control precautions: An educational intervention. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65(10):2142–2149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonge O., Rosychuk R., Bailey T., Lake R., Marrie T.J. Nursing students' general knowledge and risk perception of pandemic influenza. The Canadian Nurse. 2007;103(9):23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonge O., Rosychuk R.J., Bailey T.M., Lake R., Marrie T.J. Willingness of university nursing students to volunteer during a pandemic. Public Health Nursing. 2010;27(2):174–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]