Abstract

Allelopathy means that one plant produces chemical substances to affect the growth and development of other plants. Usually, allelochemicals can stimulate or inhibit the germination and growth of plants, which have been considered as potential strategy for drug development of environmentally friendly biological herbicides. Obviously, the discovery of plant materials with extensive sources, low cost and markedly allelopathic effect will have far-reaching ecological impacts as the biological herbicide. At present, a large number of researches have already reported that certain plant-derived allelochemicals can inhibit weed growth. In this study, the allelopathic effect of Artemisia argyi was investigated via a series of laboratory experiments and field trial. Firstly, water-soluble extracts exhibited the strongest allelopathic inhibitory effects on various plants under incubator conditions, after the different extracts authenticated by UPLC-Q-TOF-MS. Then, the allelopathic effect of the A. argyi was systematacially evaluated on the seed germination and growth of Brassica pekinensis, Lactuca sativa, Oryza sativa, Portulaca oleracea, Oxalis corniculata and Setaria viridis in pot experiments, it suggested that the A. argyi could inhibit both dicotyledons and monocotyledons not only by seed germination but also by seedling growth. Furthermore, field trial showed that the A. argyi significantly inhibited the growth of weeds in Chrysanthemum morifolium field with no adverse effect on the growth of C. morifolium. At last, RNA-Seq analysis and key gene detection analysis indicated that A.argyi inhibited the germination and growth of weed via multi-targets and multi-paths while the inhibiting of chlorophyll synthesis of target plants was one of the key mechanisms. In summary, the A. argyi was confirmed as a potential raw material for the development of preventive herbicides against various weeds in this research. Importantly, this discovery maybe provide scientific evidence for the research and development of environmentally friendly herbicides in the future.

Subject terms: Ecology, Plant sciences

Introduction

The application of chemical pesticides has made substantial contributions to global agricultural development and saved countless people from hunger. However, in recent years, the overuse of chemical pesticides has resulted in excessive pesticide residues in agricultural products, causing serious environmental problems and posing a huge threat to human health1. Therefore, the concepts of “ecological farming” and “organic products” were proposed to reduce the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides and to develop new, safe, effective and pollution-free substitutes. Thus, quite a few green pesticides and herbicides have been applied to meet the societal needs.

Allelopathy, also called the interaction effect, means that chemical substances produced by certain plants then affect the growing development of other plants2. Allelochemicals can stimulate or inhibit the germination or/and growth of plants, and increase the resistance of crops to biotic and abiotic stress. Proverbially, plant-derived allelochemicals do not exert residual or toxic effects. Therefore, they are considered as the perfect substitutes for synthetic herbicides3. As early as the late nineteenth century, researchers occasionally found that weeds were not grew near the walnut trees. Based on this interesting phenomenon, scientists revealed that the walnut tree secretes walnut quinone to inhibit the growth of surrounding weeds. In the 1980s, sorghum quinones released from sorghum roots were also reported to effectively restrain the germination and growth of Abutilon theophrasti, Amaranthus retroflexus, Echinochloa crusgalli, Digitaria sanguinalis and Setaria viridis. Obviously, studies of plant-derived herbicides based on allelopathy were gradually reported.

To date, numerous commercial herbicides have been successfully discovered from plants or plant extracts worldwide. In 1996, Cook isolated a compound called strigol from cotton root secretions which effectively promoted the germination of Striga asiatica seeds, the strigol treatment induced the “suicidal germination” of Striga asiatica, Orobanche coerulescens and other parasitic weeds in the absence of hosts4. Moreover, the trigoxazonane secreted by Trigonella foenum-graecum root system can effectively inhibit the seeds germination of Orobanche crenata (a malignant weed in the field of leguminous crops)5. In addition, a Medicago sativa extract also showed a certain concentration-dependent inhibiting effect on the germination and growth of Elymus nutans seeds6. In brief, plant-derived allelochemicals have high research value and broad application prospects. Therefore, more plant materials with a wide range of sources, low cost and markedly allelopathic effects are urgently explored to be bioherbicide.

Artemisia argyi, a perennial herbaceous plant widely known in Asia, is a renowned traditional medicinal material used in China as the treatment of pain, bleeding and eczema7. A. argyi is rich in secondary metabolites, including many chemical constituents which are beneficial to human health, such as volatile oils, flavonoids, tannins, polysaccharides and phenolic acid. From ancient times, A. argyi is mainly used to produce moxa stick for moxibustion to prevent and treat multifarious disease in China, Japan and Korea. Moxa are obtained by crushing, sifting, mashing and sieving A. argyi leaves. Typically, 5 to 30 kg of A. argyi leaves can produce only 1 kg of moxa. The remaining wastes comprise the mesophyll tissue, petiole, vein and other fine debris of A. argyi leaves are commonly called as A. argyi leaf powder8. According to preliminary statistics, about 11,160,000 kg of A. argyi powder were produced every year in China, needing to be dealt with urgently. However, A. argyi leaf powder has not yet been widely consumed in industry. Meanwhile, the storage of A. argyi powder occupies a large amount of factory space and the disposal of A. argyi powder is costly to the industry. Thus, comprehensive utilization of A. argyi powder is urgently to be expanded for the industry of A. argyi to conduct waste disposal.

In a previous study, we plan to exploit the A. argyi leaf powder as fertilizer in a Chrysanthemum morifolium field. Coincidently, we found that A. argyi powder could significantly inhibit the germination of weeds and reduce the varieties and biomass of weeds in experimental field. In further investigation in local area, we are also told that the waste water of A argyi essentia oil industry resulted in the inhibition of germination of plant seeds when the effluent was discharged into the farmland directly. Therefore, we speculated that certain allelochemicals present in A. argyi might inhibit weed growth. In the present study, different solvents, including distilled deionized water, 50% ethanol and pure ethanol, were used to extract allelochemicals in A. argyi and the ingredients were authenticated by UPLC-Q-TOF-MS. Meanwhile, the results showed that the water-soluble extracts exhibit the strongest allelopathic inhibitory effect on the germination of Brassica pekinensis, Lactuca sativa and Oryza sativa seeds. Pot experiments suggested that both dicotyledons and monocotyledons could be inhibited by seed germination and growth. Furthermore, field experiments also confirmed that A. argyi exhibited a significant inhibitory effect on the germination and growth of weed seeds. At last, transcriptomics analysis indicated that A.argyi inhibited the germination and growth of weed via multi-targets and multi-paths while the inhibiting of the chlorophyll synthesis of target plants was confirmed as one of the key mechanisms. In summary, this study not only reveals the inhibitory effect of A. argyi on weeds but also may provide the scientific evidence for the development of an environmentally friendly herbicide.

Results

The chemical components analysis of different extracts of A. argyi

In our preliminary study, we accidentally found that A. argyi powder significantly inhibited the germination and reduced the varieties and biomass of weeds in the field, when it was applied as a fertilizer originally. Therefore, we speculated that certain allelochemicals present in A. argyi might inhibit the growth of weeds. To investigated the possible allelochemicals in A. argyi, three solvents (water, 50% ethanol and pure ethanol) were used to extract the metabolites in A. argyi leaves. The three type of extracts were analysed by UPLC-Q-TOF-MS and the components were confirmed by comparison with synthetic standards and MS data in literatures9–11. As shown in Table 1 and supplement Fig. 1, we have identified a total of 29 components in A. argyi. Six main compound mass signals were identified in the water extract: caffeic acid, schaftoside, 4-caffeoylquinic acid, 5-caffeoylquinic acid, 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid and 3-caffeoylquinic acid. The main compounds of the 50% ethanol extract were 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 3-caffeoylquinic acid, schaftoside, rutin, kaempferol 3-rutinoside, 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 3-caffeoy,1-p-coumaroylquinic acid, 1,3,4-tri-caffeoylquinic acid and eupatilin. The metabolites with higher contents in the pure ethanol extract were eupatilin, jaceosidin and casticin. Among these compounds, caffeic acid is very unique in water extract. Higher contents of schaftoside, 4-caffeoylquinic acid and 3-caffeoylquinic acid were observed in water extract and 50% ethanol extract, but very low concentrations were detected in the pure ethanol extract. 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid, jaceosidin, eupatilin and casticin were present at higher concentrations in the 50% ethanol extract and pure ethanol extract, but were detected at very low concentrations or were absent in the water-soluble extract. In a word, we have preliminarily identified the chemical components of different extracts.

Table 1.

The chemical composition of different solvent extracts of A. argyi.

| Compd | Rt/min | Molecular Formula | Exptl.[M − H]− | MS/MS fragmentation | Identification | Water-soluble extract | 50% ethanol extract | Pure ethanol extract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.26 | C16H18O9 | 353.0842 | 191.0515, 179.0294, 173.0415, 161.0181, 135.0404 | 5-Caffeoylquinic acid* | + | + | – |

| 2 | 4.40 | C16H18O9 | 353.0839 | 191.0511, 179.0305, 173.0391, 161.0198, 135.0403 | 3-Caffeoylquinic acid* | + | + + | – |

| 3 | 4.64 | C16H18O9 | 353.0845 | 191.0513, 179.0302, 173.0407, 161.0191, 135.0400 | 4-Caffeoylquinic acid* | + | + | – |

| 4 | 4.87 | C9H8O4 | 179.0304 | 135.0402, 134.0323, 89.0333 | Caffeic acid* | + + + | – | – |

| 5 | 4.99 | C12H18O7S | 305.0665 | 225.1123, 96.9574 | Hydroxyjasmonic acid-O-sulphate | + | + | – |

| 6 | 5.37 | C18H28O9 | 387.1636 | 207.0992 | Hydroxyjasmonic acid hexose | + | + | – |

| 7 | 5.75 | C27H30O15 | 593.1507 | 533.1297, 503.1192, 473.1214, 383.0719, 353.0681, 117.0279 | Apigenin-6,8-di-C-glucoside | + | + | – |

| 8 | 6.07 | C17H20O9 | 367.1016 | 193.0591, 191.0462, 173.0442 | 5-Feruoyl quinic acid | + | + | + |

| 9 | 6.52 | C26H28O14 | 563.1412 | 473.1059, 443.0958, 383.0724, 353.0629 | Schaftoside* | + + | + + | – |

| 10 | 6.66 | C15H18O5 | 277.1041 | 259.0922, 233.1140, 215.1024 | Artemargyinolide C | + | + | – |

| 11 | 6.97 | C26H28O14 | 563.1412 | 473.1059, 433.0950, 383.0627, 353.0685 | Isoschaftoside* | – | – | – |

| 12 | 7.39 | C27H30O16 | 609.1473 | 301.0245, 300.0179 | Rutin | – | + + | + |

| 13 | 7.52 | C27H30O15 | 593.1508 | 285.0309, 284.0468, 133.0291 | Kaempferol 3-rutinoside | + | + + | – |

| 14 | 7.65 | C21H20O12 | 463.0862 | 301.0215, 300.0212, 271.0225, 255.0222 | Quercetin − 3-O-glucoside | – | + | – |

| 15 | 8.23 | C25H24O12 | 515.1187 | 353.0829, 335.0738, 191.0505, 179.0306, 173.0407, 161.0189, 135.0399 | 3,4-Dicaffeoylquinic acid* | – | + + | + |

| 16 | 8.45 | C25H24O12 | 515.1193 | 353.0845, 335.0781, 191.0516, 179.0315, 173.0442, 161.0166 | 1,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid | + | + | + |

| 17 | 8.57 | C25H24O12 | 515.1188 | 353.0844, 335.0748, 191.0512, 179.0299, 173.0408, 161.0189, 135.0394 | 3,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid* | + | + + | + |

| 18 | 9.18 | C21H18O11 | 445.0754 | 270.0433, 269.0479 | Apigenin-O-glycuronide | + | + | - |

| 19 | 9.52 | C25H24O12 | 515.1179 | 353.0842, 335.0720, 191.0512, 179.0302, 173.0408, 161.0196, 135.0394 | 4,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid* | + | + + + | + |

| 20 | 10.27 | C25H24O11 | 499.1234 | 353.0838, 337.0976,319.0792,191.0520 | 3-Caffeoy,1-p-coumaroylquinic acid | – | + + | – |

| 21 | 11.28 | C15H12O6 | 287.0518 | 151.0020, 135.0375 | Dihydrokaempferol | – | + | + |

| 22 | 11.88 | C15H10O6 | 285.0367 | 175.O373, 151.0083, 133.0291,107.0193 | Luteolin | – | + | – |

| 23 | 12.61 | C34H30O15 | 677.1521 | 515.1199, 497.1191, 353.0866, 335.0796, 191.0554, 179.0348, 173.0350, 161.0194 | 1,3,4-Tri-caffeoylquinic acid | – | + + | – |

| 24 | 14.07 | C15H10O5 | 269.0419 | 151.0050, 117.0307 | Apigenin* | + | + | + |

| 25 | 14.46 | C16H12O6 | 299.0526 | 285.0350, 284.0288, 256.0336, 227.0304, 212.0421, 186.0281, 136.9832 | Hispidulin | – | + | + |

| 26 | 15.11 | C17H14O7 | 329.0632 | 314.0396, 299.0154, 145.0239 | Jaceosidin* | – | + | + + |

| 27 | 17.36 | C17H14O6 | 313.0676 | 298.0424, 283.0257 | Dihydroxy-dimethoxy flavone | – | + | + |

| 28 | 17.88 | C18H16O7 | 343.0848 | 328.0480, 313.0371, 298.0146, 132.0202 | Eupatilin* | + | + + | + + + |

| 29 | 18.73 | C19H18O8 | 373.0907 | 358.0674, 343.0438, 328.0193, 315.0466, 285.0003, 257.0053, 229.0100, 201.0140, 173.0180, 145.0226, 117.0275 | Casticin* | – | + | + |

“ + + + , + + , + ” means that the relative content is from high to low, “–”means very low content; Compd. was the compound number; Rt represtented retention time; Exptl. [M-H]- was experimental m/z of molecular ions in the negative ionisation mode; *Compound was positively identified by comparing the retention time, high-resolution molecular ions and fragment ions with the authentic standards. The mass spectrometry data such as total ion chromatograms, molecular ion peaks and secondary fragment ions were collected by Masslynx 4.1 software and processed with ProGenesis QI V2.0 (Waters Corp., Milford, USA).

Comparison of the allelopathic effects of different extracts of A. argyi

To explore the allelopathic effects of three different extracts of A. argyi, seed germination and seedling growth of B. pekinensis, L. sativa and O. sativa were investigated after treatment of A. argyi powder extracts. The results showed that the allelopathic inhibition increased in a concentration dependent manner. When seeds were incubated with extracts in a range of concentrations, the water-soluble extract of A. argyi powder exerted an extremely significant inhibitory effect on the germination index of all the three plants (Fig. 1a,b). While the 50% ethanol extract also showed striking allelopathic inhibitory effects on the germination index of B. pekinensis and L. sativa, but moderately inhibitory effects on O. sativa (Fig. 1c,d). Similarly, the pure ethanol extract only showed powerful inhibitory effects on the germination index of B. pekinensis and L. sativa, but no effects on O. sativa (Fig. 1e,f). Additionally, the water-soluble extract of A. argyi powder displayed extremely inhibition of the biomass of the three plants (Fig. 2a), while the 50% ethanol extract also exerted extremely significant allelopathic inhibitory effects on the biomass of B. pekinensis and L. sativa but inhibited O. sativa moderately (Fig. 2b). However, the pure ethanol extract exerted inhibitory effects on the biomass of these three plants only in high concentrations (Fig. 2c). Based on these results, the allelopathic intensity of the three different extracts of A. argyi was in the order of water-soluble extract > 50% ethanol extract > pure ethanol extract.

Figure 1.

The different solvent exracts of A. argyi: (a,b) the water-soluble extract, (c,d) the 50% ethanol extract,and (e,f) the pure ethanol extract exert allelopathic effects on germination index of different plants. (n = 3,*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Allelopathic effects of the water-soluble extract (a), the 50% ethanol extract (b),and the pure ethanol extract(c) from A. argyi with different concentrations on biomass of three plants were compared. (n = 3,*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

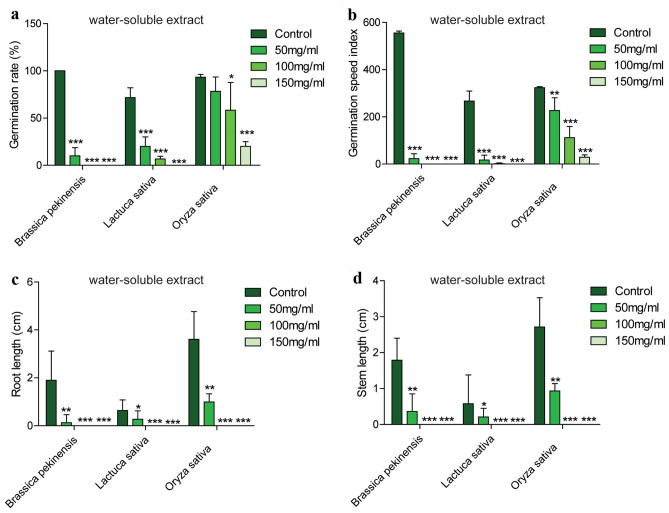

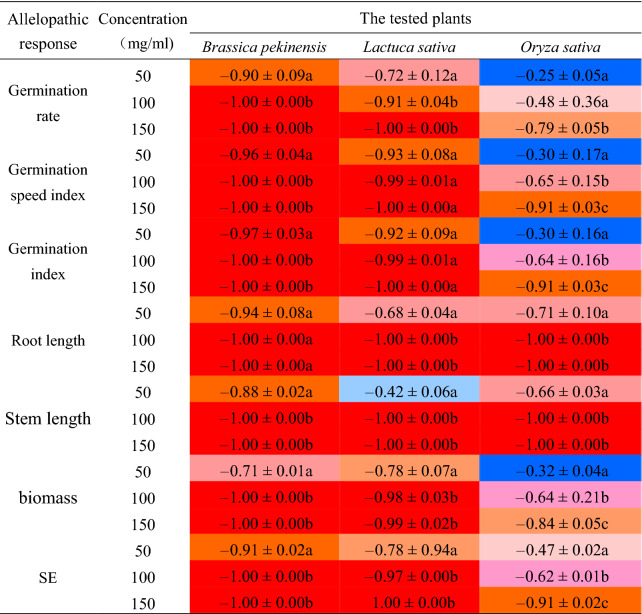

The water-soluble extract of A. argyi inhibited the germination and growth of different plants

From the above results, water-soluble extract of A. argyi powder exhibited the strongest allelopathic effects on plant growth. To evaluate systematacially, the germination rate, germination rate index, germination index, root length, stem length and biomass were selected as the allelopathic response indexes as previously reported12,13. As shown in Fig. 3 and Table 2, the germination rate, germination speed index, germination index, root length, stem length and biomass of B. pekinensis could be significantly inhibited by a low concentration extract (50 mg/ml), and the order of inhibition efficiency was: germination index > germination speed index > root length > germination rate > stem length > biomass. When the treatment concentration up to 100 mg/ml, all the allelopathic indexes were -1.00 which indicated that no seeds could germinate under this treatment concentration. For L. sativa, the order of inhibition efficiency was germination speed index > germination index > biomass > germination rate > root length > stem length. All allelopathy response indexes reached -1.00 when plants were treated with 150 mg/ml extract. For O. sativa, the six physiological indexes also could be inhibited by a low concentration of extract (50 mg/ml), but the changes were not as obvious as the changes in B. pekinensis and L. sativa. The intensity of inhibition on the six indexes was root length > stem length > biomass > germination index > germination speed index > germination rate. When O. sativa seeds treated with 100 mg/ml of extract, the allelopathic response index of root length and stem length were -1.00. The germination rate, germination speed index, germination index and biomass were -0.79, -0.91, -0.91 and -0.84, respectively, under the treatment with 150 mg/ml of extract. In brief, according to the comprehensive allelopathy index of the 6 indicators , the order in which they were sensitive to water-soluble extract of A. argyi were B. pekinensis (Cruciferae) > L. sativa (Compositae) > O. sativa (Gramineae).

Figure 3.

The water-soluble extract of A. argyi inhibits the germination and growth of Brassica pekinensis, Lactuca sativa and Oryza sativa. Specific performance is in a series of indicators: (a) the germination rate, (b) the germination speed index, (c) the root length, (d) the stem length. (n = 3,*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Allelopathic response indexes of the water-cooled extract of A. argyi on different tested plants.

(The color is near to deep red, it means that the Allelopathic response indexes is closer to - 1; the color is near to deep blue, it means that the Allelopathic response indexes is closer to 0. Different letters in the same column showed significant differences, with a significant level of 5%).

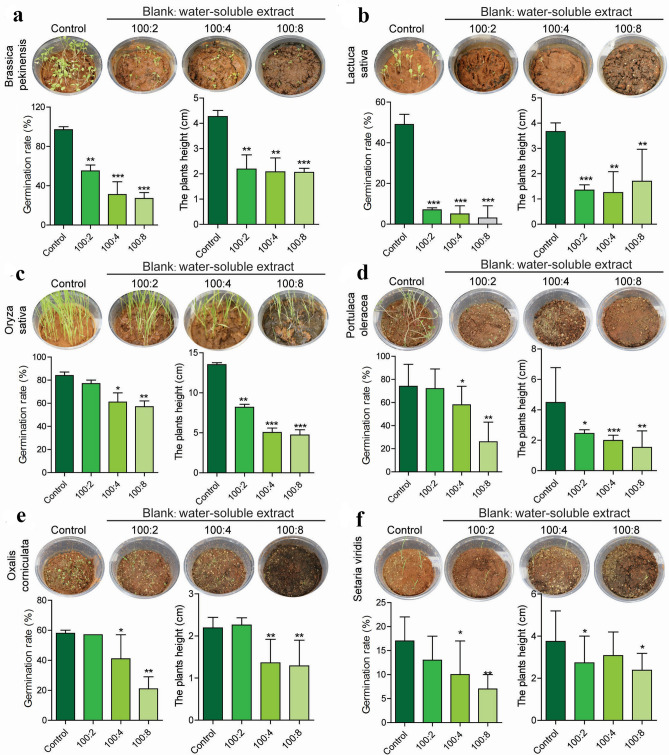

A.argyi inhibited the germination and growth of different plants in pot experiment

Further, the allelopathic effects of A. argyi were evaluated in pot experiments via soil mixed with a certain proportion of A. argyi powder. Firstly, seeds of B. pekinensis, L. sativa, O. sativa, P. oleracea , O. corniculata and S. viridis were sown into the mixed soil to observe the effects of A. argyi on seeds germination and plant growth. As shown in Fig. 4, when the proportion of soil: A. argyi powder was 100:2, the germination rate of B. pekinensis and L. sativa was significantly inhibited, and the plant height of B. pekinensis, L. sativa, O. sativa and P. oleracea was also inhibited. As the proportion of A. argyi powder gradually enhanced, the level of inhibition of the germination rate and plant height of these six tested plants was gradually increased. When the ratio reached 100:8, the germination inhibition rates of B. pekinensis, L. sativa, O. sativa, P. oleracea, O. corniculata and S. viridis were 71.82%, 93.20%, 31.75%, 65.47%, 63.60% and 60.78%, respectively. The plant height inhibition rates were 51.76%, 71.39%, 64.99%, 65.70%, 40.94%, and 36.53%, respectively, and the leaves turn yellow gradually in many plants. Therefore, the results from the laboratory were remarkable, it is urgent to verify the A.argyi powder as a weed herbicide in the field.

Figure 4.

Mean germination index and plants height plus standard deviation for the six species with different proportions of A. argyi treatment in pot experiment: Brassica pekinensis (a), Lactuca sativa (b), Oryza sativa (c), Portulaca oleracea (d), Oxalis corniculata (e), Setaria viridis (f). (n = 3,*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

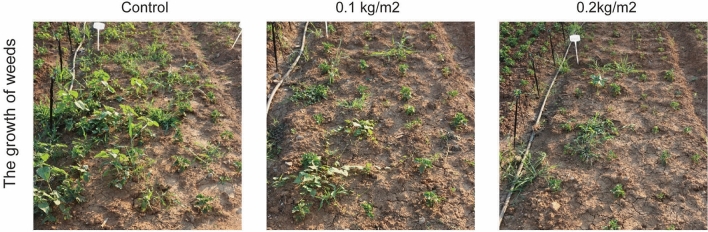

A.argyi inhibited the germination and growth of weeds in Chrysanthemum morifolium field

Then, A. argyi powder was applied into the C. morifolium field to explore the inhibition of weeds and evaluate the adverse effect on crops. After the application of A. argyi powder for one month, six species of weeds appeared in the control group, while 3 species of weeds appeared in the group treated with 0.1 kg/m2 powder, and only 1 species of weeds appeared in the group treated with 0.2 kg/m2 powder (Fig. 5). Our previous report14 showed that the inhibition rate of weeds species were 50% and 83.33%, respectively, in the low dose group and the high dose group. Furthermore, the quantity and biomass of weeds were inhibited by 46.61% and 60.98% in the 0.1 kg/m2 treatment group compared with control group14. The weed quantity and biomass were inhibited by 60.90% and 82.11%, respectively, in the 0.2 kg/m2 treatment group14. In addition, C. morifolium grew very well in the field with no growth inhibition by A. argyi powder. After C. morifolium was harvested in the autumn, there were no significant differences in the number of flowers and the weight of flowers between the experimental group and the blank control group. Therefore, A. argyi powder did not inhibit the growth of the existing crops in the field, but only exerted an obvious effect on the ungerminated weed seeds in the field. Importantly, A. argyi powder may be a potential raw material for developing safe and environmentally friendly plant-sourced herbicides.

Figure 5.

Actual growth of weeds in Chrysanthemum morifolium field with A. argyi treatment.

A.argyi inhibited the germination and growth of weed via the suppression of chlorophyll synthesis and photosynthesis

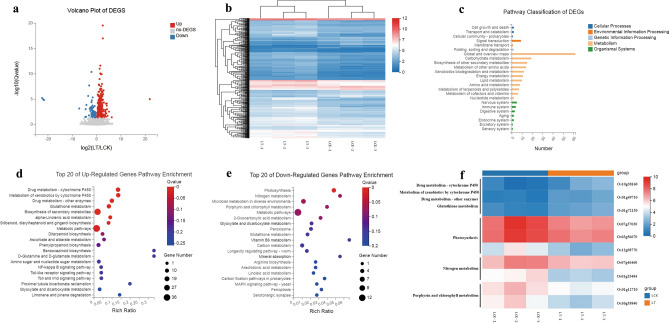

The inhibitory effect of weeds has been well documented, but the mechanism is urgently to be revealed. As reported15, transcriptomic analysis is the rapid and objective method to explore the mechanism. For the convenience of transcriptome analysis, we choosed the accepted model plant Oryza sativa as the research object, based on the BGISEQ500 platform. Each sample produced an average of 6.76G of data, with a total of 87.42% of the reads were mapped to the reference genome. Further, genome-wide gene expression profiles were compared between A.argyi- and water-treated wild-type plants. In total, 311 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with (log2|FC (ratio of treated/control)|≥ 1, p-value < 0.05) were selected for further investigation. Among them, 245 genes were up-regulated and 66 genes were down-regulated in the A.argyi-treated plants (Fig. 6a,b).

Figure 6.

RNA-Seq Analysis of the O. sativa under two treatment models. (a) The volcano plot of DEGs. Different colors represent different gene expression trends. (b) Hierarchical cluster analysis of the significantly changed DEGs. The color key represents FPKM-normalized log2-transformed counts. (c) KEGG pathway classification analysis of DEGs. (d) Top 20 KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of up-regulated DEGs. The colors are shaded according to the Q-values level, as shown in the color bars gradually from low(red) to high(blue); the size of the circle indicates the number of DEGs from small (less) to big (more); the same of next figure. (e)Top 20 KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of down-regulated DEGs. (f) The expression of key DEGs in key pathways. The color key represents FPKM-normalized log2-transformed counts.

To elucidate the potential biological functions of the DEGs, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases were used for pathway classification and enrichment analysis. The results showed that a maximum number of genes were classified in the metabolism category, followed by organismal systems, environmental information processing, cellular processes and genetic information processing (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, KEGG pathways of up- and down-regulated DEGs were investigated separately. For up-regulated DEGs, most genes were enriched in "Metabolic pathways" and “Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites”. In detail, "Drug metabolism—cytochrome P450"(11 unigenes), "Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450" (10 unigenes), "Drug metabolism—other enzymes" (10 unigenes), and "Glutathione metabolism" (10 unigenes) , were the most significant enriched pathways(Fig. 6d). For down-regulated DEGs, Photosynthesis, Nitrogen metabolism and Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism pathways were the most significant enriched pathways (Fig. 6e). Specifically, 4 unigenes involved in Photosynthesis, 2 unigenes involved Nitrogen metabolism and 2 unigenes involved in Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism were down regulated upon A.argyi treatment (Fig. 6f). In summary, these results suggest that A.argyi inhibited the germination and growth of weed via multi-targets and multi-pathways, especially, inhibiting the photosynthesis and chlorophyll synthesis pathways.

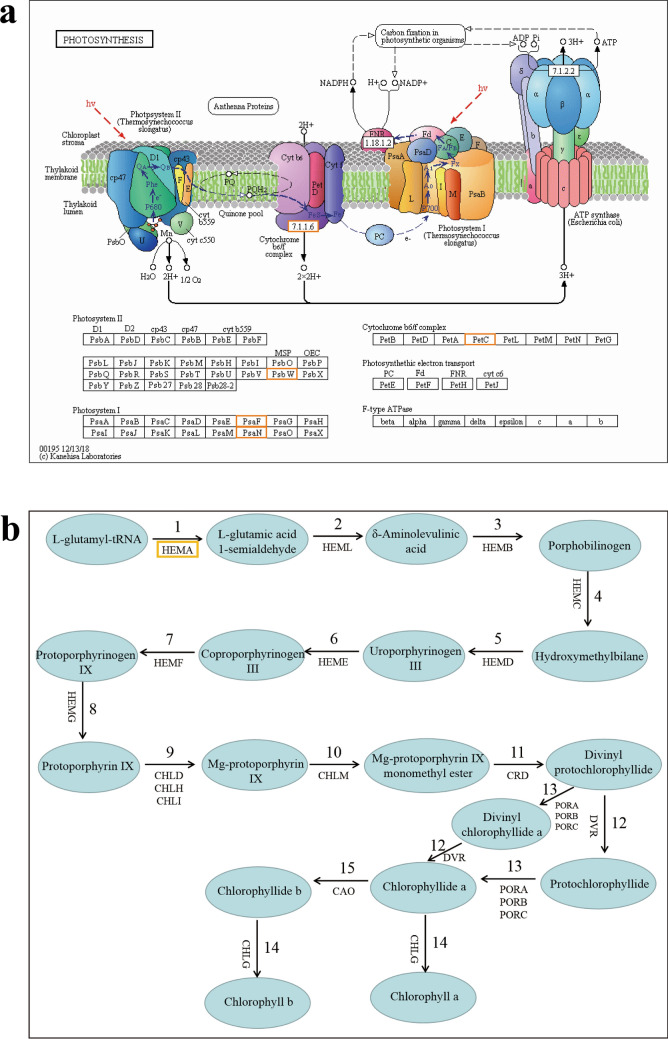

Photosynthesis is one of the most important physiological activities of plants. Our transcriptome analysis showed that photosynthesis might be the targets that inhibited by A.argyi treatment. Meanwhile, we also observed that A.argyi treatment caused the leaves of weeds turned yellow gradually in the pot experiment. The down-regulated genes of photosynthesis were involved in “photosystem II”, “photosystem I” and “cytochrome b6/f complex” (Fig. 7a)16. And the DEGs of porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism were mainly involved in the preceding part of chlorophyll synthesis pathway (Fig. 7b)17. Therefore, we speculated that suppression of chlorophyll synthesis and photosynthesis was one of the key mechanism of A.argyi to inhibit weeds.

Figure 7.

The down-regulated DEGs of “ photosynthesis” pathway (a) and “chlorophyll biosynthesis” pathway (b).

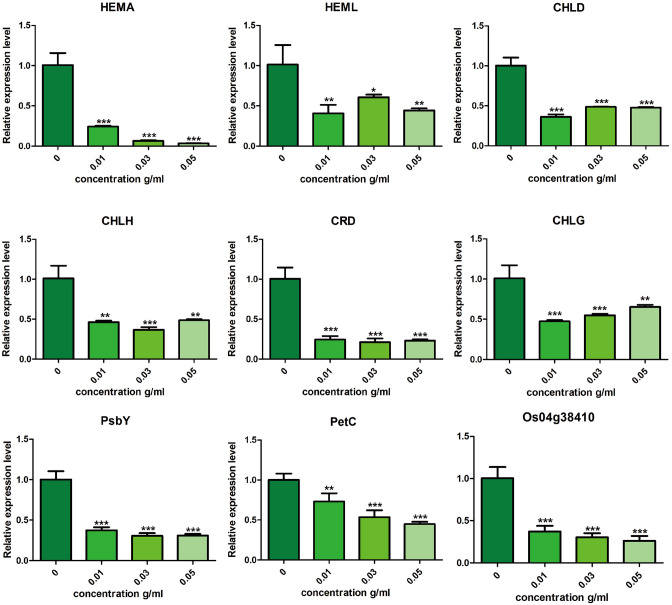

The key genes involved in photosynthesis pathways were verified by RT-qPCR, and the results were in consistent with our transcriptome analysis. As shown in Fig. 8, nine genes (HEMA “encoding glutamyl-tRNA reductase”, HEML “encoding glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase”, CHLD “encoding Mg chelatase D subunit”, CHLH “encoding Mg chelatase H subunit”, CRD “encoding Mg-protoporphyrinogen IX monomethylester cyclase”, CHLG “encoding chlorophyll synthase”, PsbY “encoding a polyprotein of photosystem II”, PetC “encoding the polypeptide binding the Rieske FeS center”, Os04g38410 “encoding subunits of the LHCII complex”) of photosynthesis were significantly suppressed by A.argyi treatment in a concentration dependent manner. Our transcriptome data and RT-qPCR verification showed that the suppression of chlorophyll synthesis and photosynthesis was one of the key mechanism of A.argyi ’s inhibitory effect on weeds.

Figure 8.

Expression of photosynthetic genes in O. sativa treated with different concentrations water-souble extact of A.argyi.

Discussion

Water-soluble metabolites might be the allelochemicals of A. argyi

This study aimed to investigate whether the A. argyi can inhibit the germination and growth of other weeds. The Fig. 1 showed that the water-soluble extract exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect on seed germination and seedling growth of B. pekinensis, L. sativa and O. sativa, compared to the 50% ethanol and pure ethanol extract. As reported18,19, different extract of the same medicinal materials often obtains diverse components then results in different effects. As shown in Figs. 1 and 2, it suggested that the allelopathy of A. argyi might be mediated mainly by water-soluble compounds, indicating the possibility of practical application. According to abundant studies20–22, allelopathic substances are secondary metabolites of plants, most of which are synthesized via the shikimic acidand isoprene metabolic pathways. At present, known allelopathic substances mainly include phenols, quinones, coumarins, flavonoids, terpenes, sugars, glycosides, alkaloids and non-protein amino acids23. A. argyi, a perennial herbaceous plant is rich in secondary metabolites including volatile oils, flavonoids, polysaccharides, tannins, terpenes and trace elements24. Therefore, different solvent extracts of A. argyi were analyzed by UPLC-Q-TOF-MS as shown in Table 1 and supplement Fig. 1. As a typical phenolic acid, caffeic acid is several times more abundant than other allelopathic substances in the water extract. Published research showed that phenolic acids such as salicylic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, cinnamic acid, vanilic acid and ferulic acid exhibited strong inhibitory effect on weeds25. Importantly, caffeic acid has also been reported to inhibit the development of Phaseolus aureus roots26. Therefore, caffeic acid may be one of the important components of A. argyi’s allelopathy.

A. argyi revealed diverse inhibitory effects on different weeds

However, the water-soluble extract of A. argyi revealed diverse inhibitory effects on different weeds. The water extract significantly inhibited the B. pekinensis and L.sativa in the incubator experiment, whereas its effect on O. sativa was relatively weak (Table 2). Similarly, the order of susceptibility of each plant was L. sativa (Compositae) > P. oleracea (Portulaca oleracea) > B. pekinensis (Cruciferae) > O. corniculata (Oxalis) > S. viridis (Gramineae) > O. sativa (Gramineae) in pot experiments (Fig. 4). In field experiments, only one species of weed, Eleusine indica (Gramineae) could grow in the field treated with a high concentration of A. argyi powder (Fig. 5). Thus all these results indicated that different weeds have diverse sensitivities to allelopathic inhibition by A. argyi powder. Currently, commercial herbicides are usually divided into monocotyledon herbicides and dicotyledon herbicides. For example, Jinduer and Yanshu exhibited better inhibition effect on monocotyledon weeds than dicotyledon weeds27. 2, 4 -D butylate and starane particularly aim at dicotyledon weeds28. Based on our results, A. argyi could inhibit both dicotyledons and monocotyledons not only by seed germination but also by seedling growth. Therefore, A. argyi could be used as a raw material to develop herbicides to effectively control weed growth.

Transcriptome revealed the possible allelopathic mechanisms

According to the current research, allelopathy can affect plant growth and development through multi-pathways, such as hormone levels29, the synthesis of polysaccharides (such as cellulose) in the cell wall30, photosynthesis31, respiration32, nucleic acid metabolism and protein synthesis33. For instance, the allelopathy of 1,4- and 1,8-cineole severely inhibited the various stages of mitosis, resulting in the cork-screw shaped morphological distortion, and inhibited the growth of roots and branches of two weedy plant species30. In addition, protocatechuic acid, the allelochemical in the aqueous extract solution of Cerbera manghas L., could inhibit the reduction of quinone electrons and destroy the electron transfer in PSII , thus negatively affecting the photosynthesis of Scrippsiella trochoidea31. It provides an economic and eco-friendly method for the green control of harmful algal blooms.

In this study, we found that the pathways related to photosynthesis, nitrogen metabolism, porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism are significantly inhibited after A. argyi treatment. These pathways are vital for plant growth and development. A series of key genes related to chlorophyll synthesis pathways including HEMA, HEML, CHLD, CHLH, CRD and CHLG were significantly reduced after treatment with A.argyi extract. In the Photosynthesis pathway, A. argyi extract could significantly down-regulate the expression of PsbY gene. The PsbY is a gene that has a novel manganese-binding, low-molecular-mass protein associated with PSII, this change might reduce the activity of PSII and the rate of electron transfer in O.sativa, resulting in a decrease in chlorophyll content. PetC is a key gene of cytochrome bf complex. Its main function is to participate in the cytochrome’s biological process in photosynthesis34. The PetC gene’s expression level was down-regulated under A.argyi extract treated compared with the control . Light harvesting complex II (LHCII) structure plays a crucial role in photosynthesis, the expression levels of Os04g38410 genes decreased means that normal photosynthesis is hindered (Fig. 8). The down-regulation of the genes in these pathway obstructs the basic processes of life activities such as carbon metabolism and nitrogen metabolism in plants. And we also observed that A.argyi treatment could decrease the content of chlorophyll and the biomass of the plants (Fig. 4), which is in consistence with our transcriptional analysis. In summary, the inhibition of A. argyi’s allelopathy on weeds might be owing to the suppression of the synthesis of chlorophyll and photosynthesis pathways.

A.argyi’s allelopathy provides a valuable way of herbicide development

Analysis of raw materials with enhanced allelopathy inhibitory effects are valuable for the development of plant-derived herbicides. The allelopathy level of A. argyi is several times higher than allelopathic materials reported to date35,36, showing good herbicidal activity. Meanwhile, with the advantage of not producing adverse effects on field crops, A.argyi is worthy to be developed as a botanical herbicide, and suggesting it as the replacement for some chemical herbicides. The analysis of chemical composition and exploration of allelopathic mechanism about A. argyi have provided a more adequate and perfect theoretical basis for the ecological control of various weeds. However, pesticide preparation techniques and wider field application assessments are still needed to bring this herbicides into the reality. Importantly, we will create an ecological planting environment to make greater contribution to human health.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The A. argyi was from Hubei Qichun. Then, the residue of the A. argyi leaf accounts for 90% percent of the total weight and is called as A. argyi leaf powder, after the production of moxa stick. The experimental seeds were Brassica pekinensis, Lactuca sativa, Oryza sativa, Portulaca oleracea, Oxalis corniculata and Setaria viridis.

Chemical composition analysis of A. argyi

The chemical constituents of A. argyi were analyzed using UPLC-Q-TOF-MS method. 0.5 g of A. argyi leaves was mixed with 20 ml of ultra-pure water, 50% ethanol or pure ethanol independently and incubated overnight. After thorough oscillation, samples were subjected to ultrasonication for 1 h and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatants were filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane and collected into a new tube. UPLC-Q-TOF-MS analysis was performed using an Waters Acquity I-Class ultra-performance liquid chromatography combined with a Xevo G2-S quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer. Waters Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm) was used. The specific chromatographic and mass spectrometric conditions were presented according to the method reported by Luo, D.D. et al11.

Preparation of extracts of A. argyi

125 g of A. argyi leaf powder were soaked in 500 ml of water, 50% ethanol and pure ethanol, respectively, then treated with ultrasonic wave for 30 min every 12 h. 48 h later, the extracts were filtered with a double layer filter bag to obtain the crude extracts. The three types of crude extracts were centrifuged and the supernatant was collected. Then the ethanol extracts were treated with water bath to remove the ethanol and redissolved with ultra-pure water to a final concentration 0.25 g/ml. Finally, the three type extracts were diluted into 50 mg/ml, 100 mg/ml and 150 mg/ml with distilled deionized water, and stored in brown bottle, at 4 °C until use.

Seeds germination assays

Seeds of B. pekinensis, L. sativa and O. sativa were sterilized with 0.2% sodium hypochlorite solution for 10 min and rinsed with distilled water for 3 times to avoid pathogen contamination. Twenty seeds from the above tested species were equidistantly placed in petri dish (diameter = 90 mm) with two layers of filter paper and then treated with 8 ml of the three extracts prepared from A. argyi at different concentrations (50 mg/ml, 100 mg/ml and 150 mg/ml) independently. Ultrapure water was used as the control, and 3 replicates of each treatment group were established. The dishes were then cultured in universal environmental test chamber at a constant temperature of 25 ± 0.5 °C, 85% humidity, and a controlled 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Two milliliters of corresponding extract were added every 48 h to maintain the humidity of the filter paper in the petri dish. The number of the germinated seeds was counted from the second day after treatment and the count lasted for one week. In addition, the root length, stem length and biomass of each treatment were also measured.

Pot experiment

For soil preparation, A. argyi powder was mixed into sand soil at the ratio of 100:0, 100:2, 100:4, and 100:8, separately. 800 g soil poured into plastic bowls with upper mouth diameter of 14.5 cm, lower mouth diameter of 10.5 cm and height of 9 cm. Then equal amount of water was added into each treatment group to soak the soil and seeds were sown 2 days later. Fifty seeds of B. pekinensis, L. sativa, O. sativa, P. oleracea, O. corniculata and S. viridis were sown independently in each bowl with three biological repeats. The germination rates and plant heights of B. pekinensis, L. sativa and O. sativa were measured at 9 days post treatment, and same data were recorded in P. oleracea, O. corniculata, and S. viridis at 13 days post treatment.

Field trial

The medicinal botanical garden of Hubei University of Chinese Medicine was selected as the experimental site to observe the effect of A. argyi on weeds growth. The experimental land in which Chrysanthemum morifolium seedlings were transplanted after spring tillage was divided into an average of 12 plots. Each plot was 5 m2, with shallow trenches separating each plots. A. argyi powder was evenly applied to the plots at the concentrations of 0 kg/m2, 0.1 kg/m2 and 0.2 kg/m2 with four biological repeats. One month later, the effects of A. argyi powder on weed varieties, quantity and biomass in each treatment groups were investigated. In addition, the growth and yield of C. morifolium were also determined.

RNA isolation and RNA-seq

O.sativa was selected as the test plant, and the seeds were placed in filter paper roll in Hoagland nutrient solution containing 0.0 g/ml (LCK), 0.03 g/ml (LT) of A. argyi powder water-cooled extract, respectively, and sampled for use 7 days later with three independent biological repeats. Total RNA was extracted from samples by using CTAB-PBIOZOL methods according to the manual instructions37. RNA libraries were generated and sequenced on BGISEQ500 platform in Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) in Shenzhen.

Sequencing analysis and differential expression analysis

The sequencing data was filtered with SOAPnuke (v1.5.2)38 by (1) Removing reads containing sequencing adapter; (2) Removing reads whose low-quality base ratio (base quality less than or equal to 5) is more than 20%; (3) Removing reads whose unknown base ('N' base) ratio is more than 5%, afterwards clean reads were obtained and stored in FASTQ format. The clean reads were mapped to the reference genome using HISAT2 (v2.0.4)39. Bowtie2 (v2.2.5)40 was applied to align the clean reads to the reference coding gene set, then expression level of gene was calculated by RSEM (v1.2.12)41. The heatmap was drawn by pheatmap (v1.0.8) according to the gene expression in different samples. Essentially, differential expression analysis was performed using the DESeq2(v1.4.5)42. To take insight to the change of phenotype, KEGG (https://www.kegg.jp/) enrichment analysis of annotated different expressed gene was performed by Phyper (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypergeometric_distribution) based on Hypergeometric test.

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

O.sativa was selected as the test plant, and the seeds were placed in afilter paper roll in Hoagland nutrient solution containing 0.0 g/ml(CK), 0.01 g/ml(L), 0.03 g/ml(M), 0.05 g/ml(H) of A. argyi powder extract, respectively. After 21 days of culture, the expression patterns of 9 genes associated with photosynthesis related to O.sativa were analyzed using RT-qPCR (gene-specific primers are provided in supplement Table 1). Total RNA was isolated from the leaves using TRIzol (Tiangen Bio Co.,Ltd., Beijing, China), and converted to cDNA using MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega Corporation, USA). RT-qPCR was conducted using RealUniversal Color PreMix(SYBR Green) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The actin gene (5′-TGCTATGTACGTCGCCATCCAG-3′ and 5′-AATGAGTAACCACGCTCCGTCA -3′) was used as an internal standard. The PCR program quoted Zhang, Q. et al15 and modified it as follows: 15 min of pre-incubation at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C and 35 s at 60 °C and steps for melting curve generation (5 s at 95 °C, 60 s at 65 °C, and finally at 97 °C). The relative gene expression of each target gene was determined using the 2−ΔΔt method.

Statistical analysis

Mass spectrometry data were recorded and analyzed using Masslynx 4.1 software. Mass spectrometry data were obtained using Progenesis QI V2.0 (Waters Corp., Milford, USA) for processing.

The germination rate (GR), germination speed index (GSI) and germination index (GI) were used to determine the germination according to the methods previously43. GR = (number of germinated seeds/total number of tested seeds) × 100%. GSI = (7X1 + 6X2 + 5X3 + 4X4 + 3X5 + 2X6 + X7) (where X is the total number of germinated seeds after X days). GI = Σ (Gt/Dt), where Gt represents the germination numbers on day t and Dt represents the corresponding germination days.

The allelopathy response index (RI) was calculated to quantify the type and intensity of allelopathy as the method described previously44 using the following formulas: when T ≥ C, RI = 1-C/T; when T < C, RI = T/C-1 (T < C). C is the control value and T is the treatment value, RI > 0 represents a stimulatory effect, RI < 0 represents an inhibitory effect, and the absolute value is consistent with the allelopathy intensity. Synthetic allelopathy (SE) was evaluated by calculating the arithmetic mean value of RI for 6 parameters, including the germination rate, germination speed index, germination index, root length, stem length and biomass.

The experimental data recorded from the study were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 and SPSS24.0 software. T-test and One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used to analyze the significant difference between different treatment groups.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Liping Kang of China Academy of Chinese Medical Science for his guidance on UPLC-MS.

Author contributions

D.L. and H.D. designed and conducted the experiments. B.H. and L.G. coordinated the project and directed work on the allelopathic effect of A. argyi Powder. L.C. completed the chemical analysis of A. argyi powder. J.L. and Z.P. determined the allelopathic strength of A. argyi powder and verified its potential to develop herbicides. J.L. and Q.C. analyzed the data. J.L. wrote the manuscript with contributions from Y.M. and H.D.. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2017YFC1700704) and Special Fund for the Construction of Modern Agricultural Industrial Technology System (CARS-21).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jinxin Li and Le Chen.

Contributor Information

Dahui Liu, Email: liudahui@hbtcm.edu.cn.

Hongzhi Du, Email: dhz3163@hbtcm.edu.cn.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-83752-6.

References

- 1.Wang YX, et al. The pollution of chemical pesticides to the environment and bioremediation measures. Territory Nat. Resour. Study. 2008;4:69–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molish HD. einfluss einer pflanze auf die-andere allelopathie. Protoplasma. 1938;29:472–473. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng F, Cheng ZH. Research progress on the use of plant allelopathy in agriculture and the physiological and ecological mechanisms of allelopathy. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:1020. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humphrey AJ, Beale MH. Strigol: biogenesis and physiological activity. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:636–640. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evidente A, Fernández-Aparicio M, Andolfi A. Trigoxazonane, a monosubstituted trioxazonane from Trigonella foenum-graecum root exudate, inhibits Orobanche crenata seed germination. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:2487–2492. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bao SHN, Miao YJ, Deng SM, Xu YM. Allelopathic effects of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) in the seedling stage on seed germination and growth of Elymus nutans in different areas. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019;39:1475–1483. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S, Zhou S, Yang W, Meng D. Gastro-protective effect of edible plant Artemisia argyi in ethanol-induced rats via normalizing inflammatory responses and oxidative stress. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;214:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin R, Meng XN, Zhao BX. Investigation on the real herb of Mugwort leaf and the standard of its processing for moxibustion. Chin. Acupunct. Moxib. 2010;30:40–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han BS, et al. Comprehensive characterization and identification of antioxidants in Folium Artemisiae Argyi using high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B. 2017;1063:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren D, Ran L, Yang C, Xu M, Yi L. Integrated strategy for identifying minor components in complex samples combining mass defect, diagnostic ions and neutral loss information based on ultra-performance liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry platform: Folium Artemisiae Argyi as a case study. J. Chromatogr. 2018;1550:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo DD, et al. Comparison of chemical components between Artemisia stolonifera and Artemisia argyi using UPLC-Q-TOF-MS. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2020;45:4057–4064. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20200602.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hachani C, Abassi M, Lazhar C, Lamhamedi MS, Béjaoui Z. Allelopathic effects of leachates of Casuarina glauca Sieb. Ex Spreng. and Populus nigra L. on germination and seedling growth of Triticum durum Desf. under laboratory conditions. Agrofor. Syst. 2019;93:1973–1983. doi: 10.1007/s10457-018-0298-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li JX, Ye JW, Liu DH. Allelopathic effects of Miscanthus floridulus on seed germination and seedling growth of three crops. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020;31:2219–2226. doi: 10.13287/j.1001-9332.202007.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li JX, et al. Application of Artemisia argyi Powder in ecological planting of Chrysanthemum morifolium. Mod. Chin. Med. 2020;22:940–944. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Q, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals that barnyard grass exudates increase the allelopathic potential of allelopathic and non-allelopathic rice ( Oryza sativa ) accessions. Rice. 2019;12:30. doi: 10.1186/s12284-019-0290-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreira KN, Iverson TM, Maghlaoui K, Barber J, Iwata S. Architecture of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. Science. 2004;303:1831–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.1093087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beale SI. Green genes gleaned. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:309–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang SY, Yin BD, Wang YN, Chen SX, Qian HQ. Study on comparison of different methods on extracting total triterpenoids from sanguisorba officinalis and its antioxidant activities. Food Res. Dev. 2019;40:111–115. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang YJ, Lu SB, Gao HD. Allelopathic effect of different solvent extraction from seed of Taxus chinensis var. Mairei on cabbage seed germination and seedling growth. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2010;26:190–194. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussain MI, Reigosa MJ. Allelochemical stress inhibits growth, leaf water relations, psII photochemistry, non-photochemical fluorescence quenching, and heat energy dissipation in three c3 perennial species. J. Exp. Bot. 2011;62:4533–4545. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soltys, D., Krasuska, U., Bogatek, R. & Gniazdowska, A. Allelochemicals as Bioherbicides—Present and Perspectives. Croatia: InTech. 518–519 (2013).

- 22.Kong CH, Xu T, Hu F, Huang SS. Allelopathy under environmental stress and its induced mechanism. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2000;20:849–854. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang AH, Dao YG, Xu YH, Lei FJ, Zhang LX. Advances in studies on allelopathy of medicinal plants in China. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs. 2011;42:1885–1890. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao L, Yu D, Cui L, Du XW. Research progress on chemical composition,pharmacological effects and product development of Artemisia argyi. Drug Eval. Res. 2018;41:216–221. [Google Scholar]

- 25.He HQ, et al. Weed-suppressive effect of phenolic acids. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2004;15:2342–2346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batish DR, Singh HP, Kaur S, Kohli RK, Yadav SS. Caffeic acid affects early growth, and morphogenetic response of hypocotyl cuttings of mung bean (Phaseolus aureus) J. Plant Physiol. 2008;165:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li YY, Zhang Y, Jiang ZM, Chen T, Wu ST. Control effects of several herbicides on weeds in tobacco fields. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2016;44:165–168. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan DH, Liu W, Gan YM. A study on the effect of several selective herbicides on the dicotyledon weeds in turf. J. Sichuan Grassland. 1999;4:43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaya Y, et al. Phytotoxical effect of Lepidium draba L. extracts on the germination and growth of monocot (Zea mays L.) and dicot (Amaranthus retroflexus L.) seeds. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 2013;31:247–254. doi: 10.1177/0748233712471702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romagni JG, Allen SN, Dayan FE. Allelopathic effects of volatile cineoles on two weedy plant species. J. Chem. Ecol. 2004;26:303–313. doi: 10.1023/A:1005414216848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Q, et al. In vitro allelopathic effects of compounds from Cerbera manghas L. on three Dinophyta species responsible for harmful common red tides. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;754:142253. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li ZX, Qin SJ, Lyu DG, Nie JY, Ma HY. Effects of aqueous root extracts on seedling growth and root respiratory metabolisms of Cerasus sachalinensis. J. Fruit Sci. 2012;29:53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baziramakenga R, Leroux GD, Simard RR, Nadeau P. Allelopathic effects of phenolic acids on nucleic acid and protein levels in soybean seedlings. Can. J. Bot. 1997;75:445–450. doi: 10.1139/b97-047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cécile B, Vitry CD, Popot JL. Membrane association of cytochrome b6f subunits. The Rieskeiron-sulfur protein from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is an extrinsic protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:7597–7602. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)37329-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen SC, et al. Allelopathic effects of water extracts from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) leaves on five major farming weeds. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017;37:1931–1938. doi: 10.1016/j.chnaes.2017.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao HC, et al. Allelopathic effects of aqueous extracts of pugionium cornutum on seed germination and seedling growth of cabbage. Plant Physiol. J. 2015;51:1109–1116. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu B, et al. Transcriptome analysis and identification of genes associated with starch metabolism in Castanea henryi Seed (Fagaceae) Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:1431. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li R, Li Y, Kristiansen K, Wang J. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2013;24:713–714. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langmead B, et al. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang MX, Ling B, Kong CH, Zhao H, Pang XF. Allelopathic potential of volatile oil from Mikania micrantha. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2002;13:1300–1302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williamson GB, Richardson D. Bioassays for allelopathy: measuring treatment responses with independent controls. J. Chem. Ecol. 1988;14:181–187. doi: 10.1007/BF01022540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.