Abstract

Female adolescents are particularly at risk of body image concerns. These individuals tend to make greater use of Social Networks and this could lead adolescents into behaviors that increase the risk of online sexual victimization (OSV). This cross-sectional study seeks to investigate the relation between body image concerns and OSV in a sample of female adolescents (n = 229) and the mediating role of three types of risky online behaviors in this link. Body image concerns predict OSV both directly and indirectly. Two of the three risky online behaviors proved to be mediators of the indirect link, namely: indiscriminate expansion of online network of contacts; and willingness to have relationships with strangers met online. Surprisingly, the third behavior, Sexting and Exhibitionism, was not shown to be a mediating factor between body image concerns and OSV. From our results emerges that adolescent girls with a negative body perception have a higher risk of OSV, and the relation between the two variables can be mediated by some risky online behaviors. It is likely that female adolescents use SNs more and adopt risky online behaviors in order to receive gratification and reassurance about their negative body image.

Keywords: Female adolescents, Body image, Online sexual victimization (OSV), Sexting, Risky online behaviors

Introduction

In the last few decades, there has been a massive increase in the use of social networks (SNs), especially among adolescents. It is estimated that in Europe, approximately 82% of teenagers have a profile on one of the SNs, with over half using them every day (Livingstone et al. 2011).

Social Networks and Online Sexual Victimization (OSV)

Although the traditional social media are still widely used by teenagers, a recent Italian study shows that the young are increasingly keen on Highly Visual Social Media (HVSM) (Marengo et al. 2018a; Marengo et al. 2019). SNs enable users to create a profile on the online platform to post and/or Exchange photos and information, chat with people already known in the real world or make contact with strangers on the web. More specifically, HVSM allow greatly reduced space for text in posts, favoring a clear prevalence of images.

While they can offer the young opportunities for social interaction, the potential risks must also be kept in mind, one of which is online sexual victimization (OSV). OSV includes a range of behaviors that are unwanted by the young person and/or performed by an adult, such as exposure to sexual material, aggressive sexual solicitation involving offline contact, and requests to engage in sexual activity or sexual talk or to provide sexual personal information (Wolak et al. 2006).

Few studies have assessed the overall prevalence of OSV among adolescents. A Spanish study (Montiel et al. 2016) found that 39.5% of teenagers have undergone OSV and 31% have experienced forms of online victimization both sexual and non-sexual simultaneously. Other studies focus only on some forms of OSV. For instance, 2.6% of German teenagers report negative online sexual solicitation with peers and 22% report online sexual interaction with an adult, of which 10% were perceived as negative (Sklenarova et al. 2018).

Females tend to be more at risk of OSV (De Santisteban and Gámez-Guadix 2017; Montiel et al. 2016; Sklenarova et al. 2018; Zetterström Dahlqvist and Gillander Gådin 2018). For example, in a sample of Swedish teenagers, Zetterström Dahlqvist and Gillander Gådin (2018) found that 35% of teenage girls have received unwanted sexual solicitation online, and one of the most common forms is the request to meet outside the virtual setting.

Social Networks and Online Sexual Victimization: Risky Online Behaviors

The development of new technologies unavoidably presents the challenge of educating teenagers in the use of social networks. Risky online behaviors can increase the danger of OSV, especially for teenage girls OSV (De Santisteban and Gámez-Guadix 2017; Zetterström Dahlqvist and Gillander Gådin 2018). In fact, while it is true that boys tend to engage more frequently in at-risk behavior online, it is also true that for teenage girl’s online communication results in unwanted behavior con more often than for boys (Morelli et al. 2016). More generally, the increased use of SNs tends to be associated with an increased risk of online victimization, and although the literature does not always agree, several pieces of evidence suggest that females tend to report greater problems with internet use (Garaigordobil et al., 2019). In addition, different kinds of online victimization tend to increase with age, probably due to more autonomous access to internet-equipped devices and their increased use (Machinbarrena et al., 2019).

Among the risk factors related to OSV, the literature underlines sexting, which is the exchange of sexually suggestive and provocative contents via media-based technology (such as smartphones, email, SNs, etc.) (Chalfen 2009). According to a study by Eurispes and Telefono Azzurro (2012), 12% of Italian teenagers have sent nude photos to others, and 26% say they have received them. The percentage of adolescents involved in sexting seems to have grown in the last few years. One recent study (Morelli et al. 2016) reports that 82% of teenagers say they have participated in sexting, with 78% saying they have been sexted and 63% having sent sexual texts at least once. In Italy, Morelli et al. (2016) found that male and non-heterosexual adolescents are most frequently involved in sexting. However, as the authors (Morelli et al. 2016) point out, the literature is inconsistent in terms of differences in gender and sexual orientation as predictors of sexting. Age does correlate to sexting, however, with older teenagers engaging in it most (Badenes-Ribera et al. 2019; Madigan et al. 2018). Like Levine (2013), we can regard sexting as standard behavior, linked to the expression and discovery of sexuality among today’s adolescents. However, sexting may constitute a danger for the young, exposing them to forms of online victimization.

According to the investigation carried out by Morelli et al. (2016), about 2% of Italian adolescents have engaged in sexting with strangers, 3% have been forced to engage in sexting by a partner, and 2% have been forced to engage in sexting by a friend. A recent meta-analysis reported the following prevalent sexting behaviors: sending sexts (14.8%), receiving sexts (27.4%), forwarding a sext without consent (12%), and having a sext forwarded without consent (8.4%) (Madigan et al. 2018). Especially for teenage girls, material exchanged during sexting could be used for malicious purposes, for instance, by an ex-partner for revenge, by third parties who spread the image to other contacts, or to extort further images or sexual favors from a minor (Wolak et al. 2018).

Another risk factor for OSV may be young people’s willingness to communicate and/or meet strangers encountered online (De Santisteban and Gámez-Guadix 2017; Wurtele and Miller-Perrin 2014; Ybarra et al. 2007). Among European minors (9–16 years), 30% have had contact at least once with people they have not previously met face-to-face (so-called “online strangers”), and 9% have met these people offline, exposing themselves to possible risks (Livingstone et al. 2011).

In online activity, it is unlikely that a minor will never encounter a stranger since, as in the real world, strangers frequent the same environment (in this case, the Internet or SNs). Although an online meeting with a stranger does not always equate to abuse, this situation could represent a risk of negative experiences. A recent cross-cultural qualitative study found a variety of experiences and reactions among minors, both positive and negative, in interacting with online strangers (Cernikova et al. 2018). The authors also underline the fact that the minor plays an active role in deciding the beginning and end of interactions with strangers (Cernikova et al. 2018). Minors on SNs sometimes examine the friend or contact requests coming from the net on the basis of gender, age, and shared interests or intentions. In other cases, however, contacts are chosen indiscriminately and friend requests are accepted automatically. This may be due to various reasons, including the desire to appear more popular (Cernikova et al. 2018). This may lead to an indiscriminate extension of a network of contacts, thereby increasing the risk of online victimization (Mitchell et al. 2008; Wurtele and Miller-Perrin 2014). Adding strangers to social lists and relating to strangers through the Internet increases the risk of online sexual victimization (OSV) (De Santisteban and Gámez-Guadix 2017).

Prentky et al. (2010) found that adolescents who met adults online and then met them offline were more likely to report risky online behaviors, such as having someone talk to them about sex when they did not want to, visiting sexual web sites, and receiving sexual pictures. These risky behaviors increase the danger of online victimization, including OSV (De Santisteban and Gámez-Guadix 2017). Teens are the preferred target of online predators, especially older predators, probably due to the teens’ greater ability to engage in discussions about relationships and sexuality (Beebe et al. 2004). In line with the social compensation hypothesis (Valkenburg and Peter 2009), adolescents who have difficulty in social interaction, and who consequently present aspects of social anxiety, a sense of isolation, and depressive feelings, may find compensation for their social interaction and relationship needs in the virtual environment. These psychological difficulties are more likely to be found in teenagers who have a negative perception of their body, particularly female teenagers (Dakanalis et al. 2013; Settanni et al. 2018; Fabris et al. 2018). In this way, the online environment can become the place to seek and get reassurances about your physical appearance and goodness, for example, by posting your own photos in an attempt to get more “likes,” and thereby receiving greater appreciation and feeling more popular. However, if these online behaviors can satisfy the need to receive reassurances about their appearance, it is also true that they risk further exposing children to online predators, increasing the risk of victimization and, in particular, sexual lysing.

Body Image Concerns, SNs Use and Online Sexual Victimization

Body image is a central aspect of teenagers’ self-concept (Tiggemann and Slater 2013). Adolescent girls, in particular, tend to report greater body dissatisfaction than males (Tiggemann and Slater 2013). Research has long shown a link between the use of SNs and the measures of body dissatisfaction. In fact, using SNs seems to be correlated to body image concerns, and photo-based activity is particularly salient (Holland and Tiggemann 2016; Meier and Gray 2014). Teenage girls who use SNs more frequently tend to present more body image concerns than girls who use them less (Tiggemann and Slater 2013). The SNs, especially HVSN such as Instagram, allow them to post photos of themselves and obtain “Likes”. These, and other signs of approval, constitute a marker of peer status and popularity, as well as a sign of complying with models considered physically attractive. Qualitative research suggest that teenage girls see the number of likes received as indicative of their beauty and self-worth, and also adopt strategies to get more likes (Chua & Chang, 2016). It is therefore possible that the SN acts as a social reinforcement for teenagers and can in particular promote risky online behaviors and increase the risk of online victimization, especially of a sexual kind. However, this aspect is not examined in depth in the current literature. Exposure to SNs may increase the risk of attracting the attention of potential online sexual attackers, and risky online behavior will increase contact with such attackers.

Some research studies have found a correlation between body image concerns and some risky online behaviors. Some studies (Bianchi et al. 2017) underline that sexting can be used as a strategy to obtain body image reinforcement, which becomes particularly important for teenagers with a need for peer acceptance and popularity, typical of this age group. However, if sexting and the posting of personal images enable them to receive positive feedback that overcomes the perception of a body image felt to be unsatisfactory or defective, it may happen that in order to increase the positive feedback, teenagers will indiscriminately extend their network of contacts to include strangers and may thus be more inclined to interact with online strangers. Some evidence to support this has been presented by Kim and Chock (2015). The authors found a correlation between body image concerns and online social grooming behaviors, associated in turn with the tendency to have an increased number of contacts with whom to interact on SNs, thus leading to the indiscriminate extension of the network of contacts. On the basis of our hypotheses, it would appear that, along with sexting, a willingness to interact with online strangers and the indiscriminate enlargement of the list of contacts could play a mediating role in the connection between body image concerns and OSV in Italian teenage girls.

Body Image and Online Victimization

Various studies show a link between Online Victimization and body image concerns, especially in females (Frisén et al. 2014; Mishna et al. 2010; Ramos-Salazar 2017). Females tend to receive more photos and messages with sexual content, to look at the nude photos spread on the SNs without authorization, and to be called names online (Mishna et al. 2010). However, the majority of the studies examined the connection between Online Victimization and Body Image Concerns in the context of cyber-bullying. Moreover, body image has been seen as a target of online victimization or as the negative backlash of victimization on individuals’ mental health (Marengo et al. 2018b). At the same time, for teenage girls the online environment can act as reinforcement of their body image and can push them to adopt risky online behaviors like those discussed above. This could increase the risk of victimization, especially online sexual victimization (OSV). In this way, females with more body image concerns can be more prone to posting or exchanging photos, expanding their social networks to recruit a greater audience, and more liking, probably in order to get reassurances about their body image; as a result, they can more easily find themselves in intimate and face-to-face relationships with strangers met online. Therefore, with these conditions, female teenagers could be more exposed to and intercepted by potential sexual attackers in the online world.

Aims of the Study

Body image concerns are typical especially among female adolescents (Tiggemann and Slater 2013). Their influence on female teen psychosocial adjustment has been widely recognized by scholars in the last few decades (Ramos-Salazar 2017). Since little is known about the relationship between body image concerns, risky online behaviors, and OSV, the goals of the present study are (i) to examine the extent to which body image concerns predict OSV and (ii) to test whether the connection between body image concerns and OSV is mediated by risky online behaviors, namely, sexting and online exhibitionism, indiscriminate expansion of SNs, and intimate and face-to-face relationships with strangers met online. On the basis of the literature reviewed above, we hypothesize that body image concerns predict a higher risk of OSV. The positive effect of body image concerns on OSV is expected to be mediated by the specific risky online behaviors mentioned above. We anticipate that concerns about body image are positively associated with sexual victimization through a higher propensity to expand the social network, to establish intimate relationships with strangers met online, and to be involved in sexting or other forms of online exhibitionism.

Method

Participants

The initial sample consisted of Italian adolescents (N = 236) who took part in a larger study on social media use. From the initial sample of students who were invited to participate in the study, 97% (N = 229) agreed to take part and filled in all of the measures of interest. Participants were from grades 7 to 13, with a mean age of 15.0 years (SD = 1.40).

Procedure

Data were collected from seven schools (two middle schools and five high schools) located in the northwest of Italy. Participants were asked to fill in a paper questionnaire in pencil. Participation in the study required informed consent from both parents and students. Ethical approval to conduct research was obtained from the University of Turin IRB (protocol no. 256071).

Measures

The study used a Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ; Cooper et al. 1987), a self-report measure of body shape preoccupations. It is composed of 34 items, each of which is scored from 1 to 6 (1 = “Never,” 6 = “Always”). The overall score is the total across all the items (theoretical scores range from 34 to 204). In our sample, reliability was excellent (α = .96).

To evaluate OSV, sexting and online exhibitionism, intimate and face-to-face relationships with strangers met online, and indiscriminate expansion of online network of contacts, we selected several of the scales from the Juvenile Online Victimization Questionnaire (JOV-Q; Montiel and Carbonell 2012; Montiel et al. 2016), a self-report questionnaire already used and validated in international studies. Participants specified how often they had experienced each specific situation described in each item while using the Internet in the previous year according to a four-point Likert scale (never, occasionally, often, always). The scale of OSV consisted of 19 items (in our sample α = .84). Items on this scale included “Someone has pressured me repeatedly to talk online about sex,” “Someone has dared me to pose for sexy pictures in front of the webcam,” “Someone has sent me, without me requesting them, images or videos of people showing their private parts.”

The sexting and online exhibitionism scale consisted of four items (such as “exchange of sexual messages or images” and “creating, sharing, and forwarding sexually suggestive nude or nearly nude images”). In our sample, reliability was .69. Intimate and face-to-face relationships with strangers met online was measured on a scale composed of five items (α = .73). Examples of the items on this scale were “gave personal information to a stranger met online,” “met with an adult known online,” and “entertained an intimate relationship with someone met online.” The indiscriminate expansion of an online network of contacts was measured by seven items (α = .77). In this scale, there were items such as “looked for new friends online,” “looked for someone new online to flirt with,” and “accepted friendships from people I have never met personally.”

Strategy of Analysis

Preliminary analyses were performed to investigate the distribution of each study variable and to examine whether there were statistically significant associations between demographic variables (i.e., sex and age) and our study variables (i.e., OSV, body shape concerns, sexting and online exhibitionism, indiscriminate expansion of online SNs, and intimate and face-to-face relationships with strangers). Next, a multiple mediation model was tested to determine whether the relationship between body shape concerns and OSV was mediated by sexting and exhibitionism, indiscriminate enlargement of online SNs, and intimate and face-to-face relationships with strangers. Age and time spent on social media were set as covariates. Several studies point out that age could influence body image concerns and the risk of victimization online, with older teens being at greater risk of such concerns (Clay et al. 2005) and online sexual (Machinbarrena et al., 2019). In addition, the literature seems to suggest that time spent on social media is related to an increase in body image concerns (McLean et al. 2013) and an increased risk of online victimization (Machinbarrena et al., 2019) (The hypothesized direction of our model is based on past theoretical and empirical work, but we recognize the limitations of a cross-sectional mediation model in terms of inferring directionality).

Following recommendations by Preacher and Hayes (2008), the mediation analyses we performed permitted us to estimate both a) the total indirect effect, which is the aggregate mediating effect of all the mediators included in the model, and b) the specific indirect effects—that is, the mediating effect of each specific mediator. The significance of the indirect effects was tested via a bootstrap analysis, given its advantage of greater statistical power without assuming multivariate normality in the sampling distribution (Mallinckrodt et al. 2006; Preacher and Hayes 2008; Williams and MacKinnon 2008). Parameter estimates and the confidence intervals of the total and specific indirect effects were obtained based on 5000 random samples. Effects were considered statistically significant if the 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval (CI) calculated did not include zero.

Results

Correlations and descriptive statistics for the study variables as computed on the overall sample are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix and descriptive statistics for study variables

| Variable | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | .01 | .20** | .14* | .11 | .06 | .13 |

| 2. Time spent on social media (hours) | .14* | .26** | .08 | .27** | .21** | |

| 3. Body image concerns (BSQ Total score)) | .24** | .03 | .15* | .23** | ||

| 4. JOV-Q Online sexual victimization scale | .32** | .35** | .38** | |||

| 5. JOV-Q Sexting and online exhibitionism scale | .07 | .17** | ||||

| 6. JOV-Q Indiscriminate enlargement of social network scale | .53** | |||||

| 7. JOV-Q Intimate and face-to-face relationships with strangers scale | ||||||

| Means (SD) | 5.48 (2.40) | 78.01 (38.96) | 1.07 (0.16) | 1.04 (0.17) | 1.49 (0.46) | 1.10 (0.19) |

BSQ: Body Shape Questionnaire; JOV-Q Juvenile Online Victimization Questionnaire

*p < .05., **p < .01., ***p < .001

Effects of Body Image Concerns on OSV

In order to test the effect of body image concerns on OSV, a regression model was tested using the BSQ total score as an independent variable and OSV score as a dependent variable, controlling for the effect of age and time spent on social media. The model was found to be statistically significant: R2 = .12, F(3,225) = 10.25, p < .001. The BSQ score exerted a significant positive effect on OSV:b = 0.008, β = 0.21, p = .003, 95% CI [0.0003, 0.0013].

Effects of Body Image Concerns on Risky Online Behavior

The effects of body image concerns on online behaviors that were expected to increase the risk of being sexually victimized online were studied by testing three different regression models, using the BSQ total score as predictor and, respectively, sexting and online exhibitionism, indiscriminate expansion of social network, and intimate and face-to-face relationships with strangers as dependent variables. We found that the BSQ total score exerted a statistically significant positive effect on indiscriminate enlargement of social network (b = 0.002, β = 0.15, p = .03, 95% CI [0.0002, 0.0033]) and on intimate and face-to-face relationships with strangers (b = 0.001, β = 0.23, p < .001, 95% CI [0.0005, 0.0017]). No significant effect of BSQ score on sexting and online exhibitionism emerged (b = 0.0001, β = 0.01, p = .67, 95% CI [−0.0005, 0.0007]).

Mediating Effects of Self-Exposure to Online Risks, Sexting, and Online Exhibitionism in the Relationship between Body Image Concerns and OSV

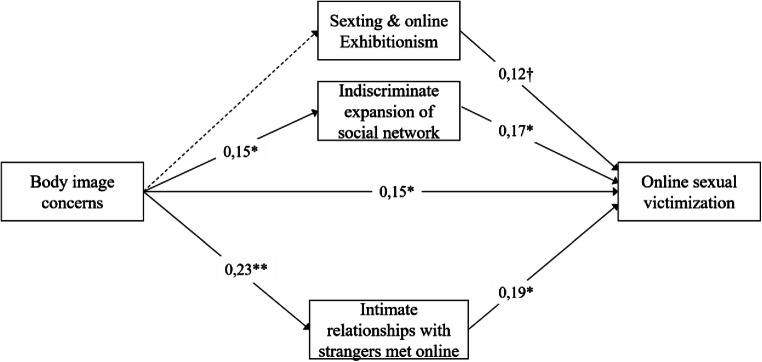

Table 2 and Fig. 1 report the results of the mediation model conducted to test the presence of any indirect effect of BSQ total score on OSV. As shown in the table, the effect of the BSQ total score on OSV was partially mediated by indiscriminate enlargement of social network and intimate face-to-face relationships with strangers. In fact, we found that the BSQ total score had a significant positive impact on both mediators, which in turn were found to exert a statistically significant positive effect on sexual online victimization. Even the sexting and online exhibitionism score had a marginally significant impact on online sexual victimization, but this variable was not influenced by the BSQ score. Figure 1 describes the tested model. Dotted lines represent non-significant links.

Table 2.

Direct and indirect effects of body image concerns on online sexual victimization

| Body image concerns (BSQ Total score) | Parameter estimate | Bias-corrected CI (95%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstand- ardized | Boot SE | Standardized | Lower | Upper | |

| Direct effect | 0.0006 | 0.0002 | 0.1450 | 0.0001 | 0.0011 |

| Indirect effect via Indiscriminate enlargement of social network | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0253 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| Indirect effect via Intimate and face-to-face relationships with strangers | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0420 | 0.0002 | 0.0005 |

| Indirect effect via Sexting and online exhibitionism | – | 0.0001 | 0.0008 | −0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| Total effects | 0.0009 | 0.0003 | 0.2131 | 0.0003 | 0.0013 |

Fig. 1.

Significant direct paths of the final mediation model. Note: Standardized parameter estimates of the significant effects are presented. ∗p < .05; ∗∗p < .01; † p < .10.

Discussion

Adolescents in western societies use SNs every day, and online interaction is now considered a standard expression of social interaction among teenagers. Obviously, Italian adolescents also use SNs.

Female adolescents, especially those using SNs, may be more at risk of body image concerns (Tiggemann and Slater 2013). In our study, adolescents who are more dissatisfied with their bodies spend more time on SNs. According to the theoreticians of social comparison theory, this may be because the use of SNs increases teens’ exposure to models of aesthetic perfection, leading them to be more inclined to make comparisons between themselves and these models (Kim and Chock 2015). However, social media can also be used to obtain reassurance about one’s body image (Bianchi et al. 2017; Kim and Chock 2015). This behavior could make it easier for teens to become involved in risky online behaviors, such as sexting or indiscriminately enlarging their contact list, which can increase the risk of online victimization, especially OSV. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have tested a direct correlation between body image concerns and OSV, although there is some evidence to suggest a possible role of body image in online victimization (Frisén et al. 2014; Ramos-Salazar 2017).

Our study found a significant correlation between body image concerns and OSV. Female teens who have a negative perception of their body are at greater risk of undergoing sexual victimization online. These data seem to support our initial hypothesis. It is likely that female adolescents with body image concerns are more inclined to adopt online behaviors that expose them to the risk of being sexually groomed than are those who do not have such concerns. To investigate this hypothesis more thoroughly, we considered some possible mediators of the relationship between body image concerns and online sexual grooming that are generally recognized as risky online behaviors: sexting, willingness to encounter online strangers online/offline, and indiscriminate enlargement of online social network (De Santisteban and Gámez-Guadix 2017; Mitchell et al. 2008; Prentky et al. 2010; Wurtele and Miller-Perrin 2014). It is possible that in order to gain reassurances about their body image, female teens resort to risky online behaviors. The latter, however, provide gimmicks and contexts in which the risk of being victimized increases, and, thus, they increase the risk of encountering a possible online sexual attacker.

Our analyses confirmed a significant correlation between body image concerns and the risky online behaviors we investigated in the sample of female teenagers. Female adolescents with a negative body image are more at risk of becoming involved in sexting behaviors, forming intimate relationships with online strangers, and indiscriminately enlarging their contact network. Our data do not confirm all the findings highlighted by the current literature, however (Bianchi et al. 2017; Kim and Chock 2015). More specifically, previous studies identified a correlation between body image concerns and sexting (Bianchi et al. 2017), but the same association was not found in our study. However, both of the other behaviors analyzed in this study were found to be significantly linked with body image concerns: female teens who experience lower levels of body self-esteem are more prone to adopt unsafe online behavior, such as expanding their social network indiscriminately and developing intimate relationships with strangers met online. A likely reason to explain these behaviors is that female adolescents may see them as a way to obtain reassurance and positive feedback from other people, without recognizing the actual danger of such behaviors. However, more studies are needed to investigate the motivations for engaging in such activities.

The three mediating factors considered in our research are all regarded as risk factors for online victimization, and for OSV in particular. Although all three correlate with body image concerns, in our sample only two factors are significant mediators in the relationship between body image concerns and OSV: indiscriminate extension of the online social network and intimate relationships with strangers met online.

The indiscriminate expansion of contact lists also mediates the relationship between body image concerns and OSV. As some authors suggest (Mitchell et al. 2008; Wurtele and Miller-Perrin 2014), adding strangers to one’s contact list could increase the risk of victimization. It is likely that expanding their list of contacts enables the users to obtain a larger amount of positive feedback on their own body image. In some SNs, by posting more photos of oneself, the user can also attract more followers, thus boosting friend requests. At any rate, the presence of strangers increases the risk of online victimization, especially OSV. It is recognized that social networks are used to form relationships and also to promote encounters of a sexual nature in the offline context or limited to the online context.

Another factor we identified as a mediating element between body image concerns and OSV is the willingness to form relationships online/offline with online strangers. Teenagers who present a negative perception of their body tend to become more involved in relationships with online strangers, and this increases the risk of being sexually victimized online. In relationships with online strangers, teenage girls with body image issues may find elements of gratification and chances to receive reassurance about their body image. However, caution is needed in the interpretation since we did not consider the motivations and contents of the intimate relationship with strangers. Moreover, it is likely that sexual motivations and discourses have a greater incidence in OSV risk (Dufrasnes 2017; Prentky et al. 2010). This aspect therefore merits further investigation.

In contrast to our expectations, sexting did not prove to be a mediator between body image concerns and OSV. Sexting is associated with body image concerns (Bianchi et al. 2017) and is recognized as a risk factor for OSV. It is likely that the contents exchanged via social media, such as images of oneself nude, are used by the receivers for malicious purposes, as in the case of revenge porn and sextortion (Wolak et al. 2006). However, in our sample, we did not find a significant mediating role of sexting with regard to the variables studied. This could be because our sample was composed of individuals who were younger than those in the samples of other studies were, and it is possible that because of their young age, many of them are not yet involved in sexting.

Body image concerns may be a key factor in understanding the dynamics of the risk of victimization, especially OSV. Body image concerns can have a negative impact on an individual’s wellbeing and development, and could increase the risk of negative developmental outcomes if correlated with negative experiences such as OSV. In particular, our research has suggested a possible mechanism that may explain the correlation between body image concerns and OSV in adolescent females, identifying in some online risky behaviors a possible mediation role. Based on previous literature, it is possible to assume that adolescent females who perceive their body image more negatively not only use SNs more frequently but, in particular, may adopt strategies in order to obtain reassurances about their physical appearance and acceptance by others. Such strategies can be seen as real risky behavior online, increasing the child’s exposure to a wider audience of online users and, in doing so, increasing the possible risk of encountering potential sexual offenders online.

In this way, body image evaluation could be regarded as a target for programs for the prevention of victimization, including OSV. By involving girls in a discussion of the role of body image and possible reflections on the adoption of risky online behaviors, their awareness of their own online behavior can be developed, and a safer and more controlled use of SNs can be promoted. Some studies have shown that a prevention program based on the principle of cognitive dissonance was useful in promoting a more positive body image and reducing the risk of eating disorder behaviors and body dissatisfaction (Halliwell and Diedrichs 2014).

Finally, in the psychological assessment of girls sexually victimized online, the assessment of body perception is an element that needs to be taken into consideration.

One final reflection is on the cultural issue. Our study was conducted in Italy, a Western country. In Western cultures, internet devices and SNs have become widespread and have become part of everyday life. It is possible that in these countries, compared to those where there is greater difficulty in accessing the internet or there is less availability of technologies, OSV may be more frequent. However, conclusive data on this type of comparison are lacking, although the literature still informs us that forms of online victimization may affect adolescents from other cultures (Baek and Bullock 2014; Marret and Choo 2018). In addition, in a cross-cultural approach, forms of online victimization seem to be more predominantly investigated in relation to peer violence and cyber-bullying, which is why we consider important future studies on OSV more generally in other cultures (Longobardi et al. 2018; Longobardi et al. 2017). Females were found to be more at risk than males of developing body image concerns in different cultures, and it seems that the aesthetic ideals of Western societies have infiltrated and influenced different non-Western societies (Maezono et al. 2019; Shagar et al. 2019). Body concern distress can vary depending on the culture they belong to, and different cultures may present risk factors for similar and different body concerns (Shagar et al. 2019). It is therefore plausible that the relationship between body image concerns in adolescent females and OSV can be found in other cultures; however, the literature appears to lack data on this, and it is hoped that there will be a better understanding of the phenomenon and insights into other cultural contexts in the future.

Conclusion

As far as we know, this is the first study designed to investigate the relationship between body image concerns and OSV in a sample of female adolescents. From our data, it emerges that adolescents with body image concerns are at greater risk of OSV. Furthermore, willingness to form relationships online/offline with online strangers and the indiscriminate expansion of contact networks proved to be significant mediators between body image concerns and OSV. Our data suggest that teenage girls with body image concerns are more inclined to engage in risky online behavior, which in turn can increase the risk of online victimization, especially OSV. It is likely that female teenagers who are more dissatisfied with their body image use SNs more often than do those who are not dissatisfied and that they engage in risky online behaviors in order to receive reassurance and positive feedback about their appearance. This could involve the risk of experiencing sexual victimization.

However, any interpretation requires caution, given the limits of our study. The cross-sectional nature of our research does not allow us to draw conclusions on the direct cause-and-effect relationship between the variables considered; a longitudinal approach could clarify the direction of the significant relations identified. Moreover, our sample was composed exclusively of female adolescents from one geographical area, so the generalizability of the data to the Italian adolescent population is limited. More generally, our study was conducted in a Western country, Italy, and, therefore, future studies will be able to evaluate the relationship between constructs in other cultures. In addition, since self-report questionnaires were used, aspects related to recall and social desirability must be taken into account. As well as adopting a longitudinal, qualitative approach, future research can take other variables into consideration in order to examine in more depth the motivations for sexting or interacting with strangers.

Clinical Implications

Our data can have positive repercussions by informing clinical and preventive interventions among professionals working with adolescents. In this way, body image evaluation can be regarded as a target for programs for the prevention of victimization, including OSV. By involving girls in a discussion of the role of body image and possible reflections on the adoption of risky online behaviors, their awareness of their online behavior can be developed and a safer and more controlled use of SNs can be promoted. Studies have.

indicated that a prevention program based on the principle of cognitive dissonance was useful.

in promoting a more positive body image and reducing the risk of disordered eating behaviors.

and body dissatisfaction (Halliwell and Diedrichs 2014). In addition, parents and teachers may.

be involved in training and awareness-raising on the topic under investigation. In this way, we can help adults to intercept in potentially at-risk situations and be competent contacts for.

adolescents to deal with the topic.

Finally, in the psychological assessment of girls sexually victimized online, the assessment of body perception is an element that needs to be considered. In these patients, an assessment of body dissatisfaction and related thoughts and emotions can help the clinician and patient work on a specific area for victimized girls: the perception of body image. This could translate not only into greater well-being for the individual but into a possible reduction in the risk of re-victimization as well.

Interventions based on cognitive-behavioral techniques or acceptance can be useful in promoting a positive body image, intervening in appearance investment, body evaluation, and cognitive processing (Lewis-Smith et al. 2019). At the same time, girls who have come to a clinician’s attention because of body image concerns should be asked about possible online victimization experiences and the use of SNs. It is possible that in the clinical pathway these adolescents may benefit from psycho-educational interventions related to the conscious use of SNs and the dangers associated with them. This could prevent possible forms of online victimization, particularly those of a sexual nature.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards and Informed

Consent Ethical approval to conduct research was obtained from the University of Turin IRB (protocol no. 256071).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Badenes-Ribera L, Fabris MA, Gastaldi FGM, Prino LE, Longobardi C. Parent and peer attachment as predictors of facebook addiction symptoms in different developmental stages (early adolescents and adolescents) Addictive Behaviors. 2019;95:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek J, Bullock LM. Cyberbullying: A cross-cultural perspective. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. 2014;19(2):226–238. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2013.849028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe TJ, Asche SE, Harrison PA, Quinlan KB. Heightened vulnerability and increased risk-taking among adolescent chat room users: Results from a statewide school survey. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(2):116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi D, Morelli M, Baiocco R, Chirumbolo A. Sexting as the mirror on the wall: Body-esteem attribution, media models, and objectified-body consciousness. Journal of Adolescence. 2017;61:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernikova M, Dedkova L, Smahel D. Youth interaction with online strangers: Experiences and reactions to unknown people on the internet. Information, Communication & Society. 2018;21(1):94–110. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1261169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfen, R. (2009). ‘It's only a picture’: Sexting,‘smutty’snapshots and felony charges. Visual Studies, 24(3), 258–268. doi:10.1080/14725860903309203.

- Li, P., Chang, L., Chua, T. H. H., & Loh, R. S. M. (2018). “Likes” as KPI: An examination of teenage girls’ perspective on peer feedback on Instagram and its influence on coping response. Telematics and Informatics, 35(7), 1994-2005.

- Clay D, Vignoles VL, Dittmar H. Body image and self-esteem among adolescent girls: Testing the influence of sociocultural factors. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15(4):451–477. doi: 10.1111/j.15327795.2005.00107.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper PJ, Taylor MJ, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG. The development and validation of the body shape questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1987;6(4):485–494. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198707)6:4<485::AID-EAT2260060405>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dakanalis A, Zanetti MA, Riva G, Clerici M. Psychosocial moderators of the relationship between body dissatisfaction and symptoms of eating disorders: A look at a sample of young Italian women. Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée/European Review of Applied Psychology. 2013;63(5):323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2013.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Santisteban P, Gámez-Guadix M. Prevalence and risk factors among minors for online sexual solicitations and interactions with adults. The Journal of Sex Research. 2017;2:1–12. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1386763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufrasnes AC. Online Risk Behavior and Depression in Adolescence (Master's thesis) 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eurispes & Telefono Azzurro (2012). Indagine conoscitiva sulla condizione dell’infanzia dell’adolescenza in Italia [ExplorativeinvestigationaboutItaliancondition of infancy and adolescence]. Retrieved from http://www.azzurro.it/sites/default/files/Sintesi Indagine conoscitivaInfanziaAdolescenza 2012_1.pdf.

- Fabris MA, Longobardi C, Prino LE, Settanni M. Attachment style and risk of muscle dysmorphia in a sample of male bodybuilders. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2018;19(2):273. doi: 10.1037/men0000096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisén A, Berne S, Lunde C. Cybervictimization and body esteem: Experiences of Swedish children and adolescents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2014;11(3):331–343. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2013.825604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garaigordobil, M., & Machimbarrena, J. M. (2019). Victimization and perpetration of bullying/cyberbullying: Connections with emotional and behavioral problems and childhood stress. Psychosocial Intervention, 28(2), 67-73.

- Halliwell E, Diedrichs PC. Testing a dissonance body image intervention among young girls. Health Psychology. 2014;33(2):201–204. doi: 10.1037/a0032585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland G, Tiggemann M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image. 2016;17:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Chock TM. Body image 2.0: Associations between social grooming on Facebook and body image concerns. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;48:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levine D. Sexting: A terrifying health risk … or the new normal for young adults? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52(3):257–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Smith, H., Diedrichs, P. C., & Halliwell, E. (2019). Cognitive-behavioral roots of body image therapy and prevention. Body Image. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the internet: the perspective of European children: full findings and policy implications from the EU Kids Online survey of 9–16 year olds and their parents in 25 countries. Retrieved from http://www.lse.ac.uk/media%40lse/research/EUKidsOnline/EU%20Kids%20II%20(2009-11)/EUKidsOnlineIIReports/D4FullFindings.pdf

- Longobardi C, Prino LE, Fabris MA, Settanni M. School violence in two Mediterranean countries: Italy and Albania. Children and Youth Services Review. 2017;82:254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Longobardi C, Badenes-Ribera L, Fabris MA, Martinez A, McMahon SD. Prevalence of student violence against teachers: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence. 2018;9(6):596–610. doi: 10.1037/vio0000202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan, S., Ly, A., Rash, C. L., Van Ouytsel, J., & Temple, J. R. (2018). Prevalence of multiple forms of sexting behavior among youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics.10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Maezono J, Hamada S, Sillanmäki L, Kaneko H, Ogura M, Lempinen L, Sourander A. Cross-cultural, population-based study on adolescent body image and eating distress in Japan and Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2019;60(1):67–76. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallinckrodt B, Abraham W, Wei M, Russell D. Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:372–378. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marengo D, Longobardi C, Fabris MA, Settanni M. Highly-visual social media and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: The mediating role of body image concerns. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;82:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marengo D, Jungert T, Iotti NO, Settanni M, Thornberg R, Longobardi C. Conflictual student–teacher relationship, emotional and behavioral problems, prosocial behavior, and their associations with bullies, victims, and bullies/victims. Educational Psychology. 2018;38(9):1201–1217. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2018.1481199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marengo D, Settanni M, Longobardi C. The associations between sex drive, sexual self-concept, sexual orientation, and exposure to online victimization in Italian adolescents: Investigating the mediating role of verbal and visual sexting behaviors. Children and Youth Services Review. 2019;102:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marret MJ, Choo WY. Victimization after meeting with online acquaintances: A cross-sectional survey of adolescents in Malaysia. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2018;33(15):2352–2378. doi: 10.1177/0886260515625502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SA, Paxton SJ, Wertheim EH. Mediators of the relationship between media literacy and body dissatisfaction in early adolescent girls: Implications for prevention. Body Image. 2013;10(3):282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier EP, Gray J. Facebook photo activity associated with body image disturbance in adolescent girls. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2014;17(4):199–206. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishna F, Cook C, Gadalla T, Daciuk J, Solomon S. Cyber bullying behaviors among middle and high school students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(3):362–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Wolak J, Finkelhor D. Are blogs putting youth at risk for online sexual solicitation or harassment? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(2):277–294. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montiel, I., & Carbonell, E. (2012). Cuestionario de victimización juvenil mediante internet y/o teléfono móvil [Juvenile Online Victimization Questionnaire, JOV-Q] Patent number 09/2011/1982. Valencia, Spain: Registro Propiedad Intelectual Comunidad Valenciana.

- Montiel I, Carbonell E, Pereda N. Multiple online victimization of Spanish adolescents: Results from a community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2016;52:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli M, Bianchi D, Baiocco R, Pezzuti L, Chirumbolo A. Sexting, psychological distress and dating violence among adolescents and young adults. Psicothema. 2016;28(2):137–142. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2015.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K, Hayes A. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentky R, Burgess A, Dowdell EB, Fedoroff P, Malamuth N, Schuler A. A multi-prong approach to strengthening internet child safety. Final Report submitted to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. US Department of Justice: Office of Justice Programs; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Salazar, L. (2017). Cyberbullying victimization as a predictor of cyberbullying perpetration, body image dissatisfaction, healthy eating and dieting behaviors, and life satisfaction. Journal of interpersonal violence. Advance online publication.10.1177/0886260517725737. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Settanni M, Marengo D, Fabris MA, Longobardi C. The interplay between ADHD symptoms and time perspective in addictive social media use: A study on adolescent Facebook users. Children and Youth Services Review. 2018;89:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.04.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shagar PS, Donovan CL, Loxton N, Boddy J, Harris N. Is thin in everywhere?: A cross-cultural comparison of a subsection of tripartite influence model in Australia and Malaysia. Appetite. 2019;134:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklenarova H, Schulz A, Schuhmann P, Osterheider M, Neutze J. Online sexual solicitation by adults and peers–results from a population based German sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2018;76:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann M, Slater A. NetGirls: The internet, Facebook, and body image concern in adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2013;46(6):630–633. doi: 10.1002/eat.22141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Social consequences of the internet for adolescents: A decade of research. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18(1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01595.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, MacKinnon D. Resampling and distribution of the product methods for testing indirect effects in complex models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2008;15:23–51. doi: 10.1080/107055107011758166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolak, J., Mitchell, K. J., & Finkelhor, D. (2006). Online victimization of youth: Five years later. National Center for Missing & Exploited Children Bulletin - #07–06-025. Alexandria, VA. Retrieved from https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=http://scholar.google.it/&httpsredir=1&article=1053&context=ccrc

- Wolak J, Finkelhor D, Walsh W, Treitman L. Sextortion of minors: Characteristics and dynamics. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2018;62(1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtele SK, Miller-Perrin C. Preventing technology initiated sexual victimization of youth: A developmental perspective. In: Kenny MC, editor. Sex education: Attitude of adolescents, cultural differences and schools’ challenges. New York: Nova; 2014. pp. 147–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D, Wolak J. Internet prevention messages: Targeting the right online behaviors. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(2):138–145. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetterström Dahlqvist, H., & Gillander Gådin, K. (2018). Online sexual victimization in youth: Predictors and cross-sectional associations with depressive symptoms. European Journal of Public Health, 1–6. wolak. 10.1093/eurpub/cky102. [DOI] [PubMed]