Abstract

To remain in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, U.S. health care providers are required to register for a National Provider Identifier (NPI). When applying for an NPI, providers must select the Healthcare Provider Taxonomy Code(s) that most closely describes the services they offer. Three distinct taxonomies describe the services offered by behavior analysts. Two of these codes, the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) and the Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) taxonomies, specify that the health care provider must hold either a certification from the Behavior Analyst Certification Board or a state-issued credential to practice behavior analysis. The purpose of this study was to investigate the concordance between health care providers who utilize these behavior-analytic NPI taxonomy classifications and health care providers who meet the credential qualifications specified in the code descriptions. Results indicated that there are potentially more than 20,000 U.S. health care providers who do not hold the behavior analyst credentials specified in the taxonomy descriptions linked to their accounts. The implications of providers being mistakenly classified as credentialed behavior analysts and credentialed assistant behavior analysts in federal data and how the field should respond are discussed.

Keywords: Applied behavior analysis, Health insurance, HIPAA, NPI, Taxonomy

Over the last two decades, the demand for highly qualified behavior analysts in the United States has increased substantially. Behavior analysts have become valued health professionals recognized for their work addressing a range of health issues, from treating substance use disorders, to improving the lives of people with developmental disorders. Based on the current trajectory, it is likely that the contribution of the field of applied behavior analysis (ABA) to health care services will only increase. Appropriately, the rules, regulations, and guidelines that influence the scope and quality of practice are constantly developing. Among these developments are the Healthcare Provider Taxonomy Codes established by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that directly relate to the practice of ABA.

To improve the U.S. health care system, the 104th Congress passed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA, 2004; Institute of Medicine, 2009). One reform introduced by HIPAA was the mandate that all individual health care providers and organizations register for a National Provider Identifier (NPI; HIPAA Administrative Simplification, 2004). CMS began issuing NPIs to HIPAA-covered entities in 2006 (Bindman, 2013). This unique 10-digit number is used to simplify the identification of health care providers, as well as patient eligibility and claims transactions common in health care practices (Oatway, 2006).

NPIs are granted to individual health care providers (Type 1) or to health care provider organizations (Type 2).1 To obtain an NPI, individuals can apply for themselves or on behalf of others via the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES) website (https://nppes.cms.hhs.gov). When applying for an NPI, applicants must provide contact, educational, and specialization information (Table 1). CMS (2019a, 2019b) compiles this information and updates the publicly available file monthly.

Table 1.

National Provider Identifier (NPI) Application Fields

|

1. Provider Profile a. Provider Name Information i. Name (Prefix, First*, Middle, Last*, Suffix) ii. Credentials iii. Other Name (if applicable) iv. Type of Other Name (if applicable) b. Other Identifying Information i. Date of Birth* + ii. TIN Type (e.g., SSN)* + iii. Tax Identification Number (TIN)* + iv. Birth Location (state/country)* + v. Gender* vi. Is the Provider a Sole Proprietor?* vii. Ethnicity (optional) + viii. Race (optional) + ix. Primary Language Spoken + x. Secondary Language(s) + 2. Address a. Business Mailing Address (correspondence address) b. Practice Location (only one required) 3. Other Identifiers a. Issuer (e.g., Medicaid, other) b. Identification Number c. State Issued d. Endpoint 4. Taxonomy a. Choose Taxonomy Filter b. Choose Taxonomy* c. Classification Name/Specialization* d. License Number e. State Issued 5. Contact Information a. Contact Type b. Name (Prefix, First*, Middle, Last*, Suffix) c. Credential(s) d. Title/Position e. Telephone Number* f. Contact Person E-mail* |

*Required fields

+ Fields that are not publicly available

During the NPI application process, health care providers must select from a list of administrative codes that comprise the Healthcare Provider Taxonomy Code Set. This code set is made available through the Washington Publishing Company (2019) and is maintained by the National Uniform Claim Committee (NUCC, 2019a). NUCC updates the code set biannually on April 1 and October 1 (Medicare Learning Network, 2019). As of April 1, 2019, the code set included more than 800 unique identifiers and 241 classifications (Table 2). The exact taxonomy code(s) selected during the NPI application process is designed to reflect the type (Level I), classification (Level II), and/or area of specialization (Level III) of the health care provider or organization (Washington Publishing Company, 2019). When selecting taxonomy code(s), applicants are given the opportunity to filter through the code set using a search box and must make their selection based on the code, classification, and specialization options presented (Fig. 1). Applicants are allowed to select up to 15 different taxonomies but must choose a primary taxonomy that best represents their practice. Notably, there are neither descriptions of the different taxonomies nor a verification procedure to attest to the accuracy of selections during the application process.2 As a result, applicants make their determinations based on the taxonomy classification names and alphanumeric codes shown without verification of the accuracy of their selections. After receiving an NPI, providers are required to update their information through NPPES within 30 days of any changes. Currently, there is no verification process in place to identify obsolete information in NPPES, and there is no explicit penalty for providers who fail to meet this requirement (Bindman, 2013).

Table 2.

List of All Classifications in the Healthcare Provider Taxonomy Code Set as of January 1, 2019 (National Uniform Claim Committee, 2019b)

| 1. Acupuncturist | |

| 2. Adult Companion | |

| 3. Advanced Practice Dental Therapist | |

| 4. Advanced Practice Midwife | |

| 5. Air Carrier | |

| 6. Allergy & Immunology | |

| 7. Alzheimer Center (Dementia Center) | |

| 8. Ambulance | |

| 9. Anaplastologist | |

| 10. Anesthesiologist Assistant | |

| 11. Anesthesiology | |

| 12. Art Therapist | |

| 13. Assistant Behavior Analyst | |

| 14. Assistant, Podiatric | |

| 15. Assisted Living Facility | |

| 16. Audiologist | |

| 17. Audiologist-Hearing Aid Fitter | |

| 18. Behavior Analyst | |

| 19. Behavior Technician | |

| 20. Blood Bank | |

| 21. Bus | |

| 22. Case Management | |

| 23. Case Manager/Care Coordinator | |

| 24. Chiropractor | |

| 25. Chore Provider | |

| 26. Christian Science Facility | |

| 27. Christian Science Sanitorium | |

| 28. Chronic Disease Hospital | |

| 29. Clinic/Center | |

| 30. Clinical Ethicist | |

| 31. Clinical Exercise Physiologist | |

| 32. Clinical Medical Laboratory | |

| 33. Clinical Neuropsychologist | |

| 34. Clinical Nurse Specialist | |

| 35. Clinical Pharmacology | |

| 36. Colon & Rectal Surgery | |

| 37. Community Based Residential Treatment Facility, Mental Illness | |

| 38. Community Based Residential Treatment Facility, Mental Retardation and/or Developmental Disabilities | |

| 39. Community Health Worker | |

| 40. Community/Behavioral Health | |

| 41. Contractor | |

| 42. Counselor | |

| 43. Custodial Care Facility | |

| 44. Dance Therapist | |

| 45. Day Training, Developmentally Disabled Services | |

| 46. Day Training/Habilitation Specialist | |

| 47. Dental Assistant | |

| 48. Dental Hygienist | |

| 49. Dental Laboratory | |

| 50. Dental Laboratory Technician | |

| 51. Dental Therapist | |

| 52. Dentist | |

| 53. Denturist | |

| 54. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pharmacy | |

| 55. Dermatology | |

| 56. Developmental Therapist | |

| 57. Dietary Manager | |

| 58. Dietetic Technician, Registered | |

| 59. Dietitian, Registered | |

| 60. Doula | |

| 61. Driver | |

| 62. Durable Medical Equipment & Medical Supplies | |

| 63. Early Intervention Provider Agency | |

| 64. Electrodiagnostic Medicine | |

| 65. Emergency Medical Technician, Basic | |

| 66. Emergency Medical Technician, Intermediate | |

| 67. Emergency Medical Technician, Paramedic | |

| 68. Emergency Medicine | |

| 69. Emergency Response System Companies | |

| 70. Epilepsy Unit | |

| 71. Exclusive Provider Organization | |

| 72. Eye Bank | |

| 73. Eyewear Supplier | |

| 74. Family Medicine | |

| 75. Foster Care Agency | |

| 76. Funeral Director | |

| 77. General Acute Care Hospital | |

| 78. General Practice | |

| 79. Genetic Counselor, MS | |

| 80. Health Educator | |

| 81. Health Maintenance Organization | |

| 82. Hearing Aid Equipment | |

| 83. Hearing Instrument Specialist | |

| 84. Home Delivered Meals | |

| 85. Home Health | |

| 86. Home Health Aide | |

| 87. Home Infusion | |

| 88. Homemaker | |

| 89. Homeopath | |

| 90. Hospice Care, Community Based | |

| 91. Hospice, Inpatient | |

| 92. Hospitalist | |

| 93. In Home Supportive Care | |

| 94. Independent Medical Examiner | |

| 95. Indian Health Service/Tribal/Urban Indian Health (I/T/U) Pharmacy | |

| 96. Intermediate Care Facility, Mental Illness | |

| 97. Intermediate Care Facility, Mentally Retarded | |

| 98. Internal Medicine | |

| 99. Interpreter | |

| 100. Kinesiotherapist | |

| 101. Lactation Consultant, Non-RN | |

| 102. Legal Medicine | |

| 103. Licensed Practical Nurse | |

| 104. Licensed Psychiatric Technician | |

| 105. Licensed Vocational Nurse | |

| 106. Local Education Agency (LEA) | |

| 107. Lodging | |

| 108. Long Term Care Hospital | |

| 109. Marriage & Family Therapist | |

| 110. Massage Therapist | |

| 111. Mastectomy Fitter | |

| 112. Meals | |

| 113. Mechanotherapist | |

| 114. Medical Foods Supplier | |

| 115. Medical Genetics | |

| 116. Medical Genetics, Ph.D. Medical Genetics | |

| 117. Medicare Defined Swing Bed Unit | |

| 118. Midwife | |

| 119. Midwife, Lay | |

| 120. Military Clinical Medical Laboratory | |

| 121. Military Health Care Provider | |

| 122. Military Hospital | |

| 123. Military/U.S. Coast Guard Pharmacy | |

| 124. Military/U.S. Coast Guard Transport | |

| 125. Multi-Specialty | |

| 126. Music Therapist | |

| 127. Naprapath | |

| 128. Naturopath | |

| 129. Neurological Surgery | |

| 130. Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine & OMM | |

| 131. Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine, Sports Medicine | |

| 132. Non-emergency Medical Transport (VAN) | |

| 133. Non-Pharmacy Dispensing Site | |

| 134. Nuclear Medicine | |

| 135. Nurse Anesthetist, Certified Registered | |

| 136. Nurse Practitioner | |

| 137. Nurse’s Aide | |

| 138. Nursing Care | |

| 139. Nursing Facility/Intermediate Care Facility | |

| 140. Nursing Home Administrator | |

| 141. Nutritionist | |

| 142. Obstetrics & Gynecology | |

| 143. Occupational Therapist | |

| 144. Occupational Therapy Assistant | |

| 145. Ophthalmology | |

| 146. Optometrist | |

| 147. Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery | |

| 148. Oral Medicinist | |

| 149. Organ Procurement Organization | |

| 150. Orthopaedic Surgery | |

| 151. Orthotic Fitter | |

| 152. Orthotist | |

| 153. Otolaryngology | |

| 154. Pain Medicine | |

| 155. Pathology | |

| 156. Pediatrics | |

| 157. Pedorthist | |

| 158. Peer Specialist | |

| 159. Perfusionist | |

| 160. Personal Emergency Response Attendant | |

| 161. Pharmacist | |

| 162. Pharmacy | |

| 163. Pharmacy Technician | |

| 164. Phlebology | |

| 165. Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation | |

| 166. Physical Therapist | |

| 167. Physical Therapy Assistant | |

| 168. Physician Assistant | |

| 169. Physiological Laboratory | |

| 170. Plastic Surgery | |

| 171. Podiatrist | |

| 172. Poetry Therapist | |

| 173. Point of Service | |

| 174. Portable X-ray and/or Other Portable Diagnostic Imaging Supplier | |

| 175. Preferred Provider Organization | |

| 176. Prevention Professional | |

| 177. Preventive Medicine | |

| 178. Private Vehicle | |

| 179. Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) Provider Organization | |

| 180. Prosthetic/Orthotic Supplier | |

| 181. Prosthetist | |

| 182. Psychiatric Hospital | |

| 183. Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facility | |

| 184. Psychiatric Unit | |

| 185. Psychiatry & Neurology | |

| 186. Psychoanalyst | |

| 187. Psychologist | |

| 188. Public Health or Welfare | |

| 189. Pulmonary Function Technologist | |

| 190. Radiologic Technologist | |

| 191. Radiology | |

| 192. Radiology Practitioner Assistant | |

| 193. Recreation Therapist | |

| 194. Recreational Therapist Assistant | |

| 195. Reflexologist | |

| 196. Registered Nurse | |

| 197. Rehabilitation Counselor | |

| 198. Rehabilitation Hospital | |

| 199. Rehabilitation Practitioner | |

| 200. Rehabilitation Unit | |

| 201. Rehabilitation, Substance Use Disorder Unit | |

| 202. Religious Nonmedical Health Care Institution | |

| 203. Religious Nonmedical Nursing Personnel | |

| 204. Religious Nonmedical Practitioner | |

| 205. Residential Treatment Facility, Emotionally Disturbed Children | |

| 206. Residential Treatment Facility, Mental Retardation and/or Developmental Disabilities | |

| 207. Residential Treatment Facility, Physical Disabilities | |

| 208. Respiratory Therapist, Certified | |

| 209. Respiratory Therapist, Registered | |

| 210. Respite Care | |

| 211. Secured Medical Transport (VAN) | |

| 212. Single Specialty | |

| 213. Skilled Nursing Facility | |

| 214. Sleep Specialist, PhD | |

| 215. Social Worker | |

| 216. Special Hospital | |

| 217. Specialist | |

| 218. Specialist/Technologist | |

| 219. Specialist/Technologist Cardiovascular | |

| 220. Specialist/Technologist, Health Information | |

| 221. Specialist/Technologist, Other | |

| 222. Specialist/Technologist, Pathology | |

| 223. Speech-Language Pathologist | |

| 224. Student in an Organized Health Care Education/Training Program | |

| 225. Substance Abuse Rehabilitation Facility | |

| 226. Supports Brokerage | |

| 227. Surgery | |

| 228. Taxi | |

| 229. Technician | |

| 230. Technician, Cardiology | |

| 231. Technician, Health Information | |

| 232. Technician, Other | |

| 233. Technician, Pathology | |

| 234. Technician/Technologist | |

| 235. Thoracic Surgery (Cardiothoracic Vascular Surgery) | |

| 236. Train | |

| 237. Transplant Surgery | |

| 238. Transportation Broker | |

| 239. Urology | |

| 240. Veterinarian | |

| 241. Voluntary or Charitable |

Fig. 1.

Screenshot taken on April 23, 2019, from the taxonomy selection section of the NPI application hosted on the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES) website: https://nppes.cms.hhs.gov

Behavior-Analytic NPI Code Taxonomies

Three of the taxonomy code classifications available for selection when applying for an NPI on the NPES website are directly relevant to the health care services offered by behavior analysts: Behavior Analyst3 (103K00000X), Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X), and Behavior Technician (106S00000X). These taxonomies were established, and in one case updated, following applications submitted to NUCC by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) and, later, the Association of Professional Behavior Analysts (APBA; G. Green, personal communication, April 23, 2019). The first of these taxonomy codes, Behavior Analyst (103K00000X), was established on July 1, 2008 (NUCC, 2019a). The original description for this taxonomy was written broadly and did not specify a provider’s degree or credentials (Tables 3, 4, 5, and 6). The Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) taxonomy description was revised on January 1, 2016, and currently states that providers should have at least a master’s degree and a BACB certification or state-issued credential (e.g., licensure) to practice ABA independently (Table 7). On July 1, 2016, two new behavior-analytic taxonomy codes, Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) and Behavior Technician (106S00000X), were established. The Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) taxonomy description states that providers should have a BACB certification or state-issued credential to practice ABA under the supervision of a credentialed behavior analyst. Additionally, the Behavior Technician (106S00000X) taxonomy description specifies that providers should practice under the close supervision of behavior analysts or assistant behavior analysts certified by the BACB or credentialed by a state (Table 7). Notably, the Behavior Technician (10600000X) taxonomy description does not specify that the provider hold a BACB credential, such as a Registered Behavior Technician, or state-issued credential.

Table 3.

Estimated Number and Percentage of Graduate- and Undergraduate-Level Licensees Holding a BACB Certification as of February 28, 2019

| State | Total Graduate Licensees | Verified BCBA/BCBA-D Certificants | % of Verified BCBA/BCBA-D Certificants | Total Undergraduate Licensees | Verified BCaBA Certificants | % of Verified BCaBA Certificants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaska | 53 | 53 | 100% | 3 | 3 | 100% |

| Arizona | 100 | 100 | 100% | 0 | 0 | |

| Kansas | 223 | 221 | 99% | 28 | 26 | 93% |

| Louisiana | 297 | 288 | 97% | 0 | 0 | |

| Massachusetts | 2,528 | 2,341 | 93% | 30 | 28 | 93% |

| New York | 1,602 | 1,564 | 98% | 25 | 21 | 84% |

| North Dakota | 31 | 28 | 90% | 4 | 1 | 25% |

| Ohio | 615 | 603 | 98% | 0 | 0 | |

| Oregon | 322 | 317 | 98% | 24 | 24 | 100% |

| Rhode Island | 161 | 160 | 99% | 10 | 10 | 100% |

| Texas | 1,708 | 1,697 | 99% | 138 | 138 | 100% |

| Vermont | 154 | 152 | 99% | 12 | 12 | 100% |

| Washington | 445 | 440 | 99% | 97 | 73 | 75% |

| Total | 8,239 | 7,964 | 97% | 371 | 336 | 91% |

Table 4.

Estimated Number and Percentage of Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) Health Care Providers Not Meeting NPI Taxonomy Credentialing Requirements

| State | Estimated Number of Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) Health Care Providers Not Meeting Credentialing Requirements | Estimated Percentage of Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) Health Care Providers Not Meeting Credentialing Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Alaska | 20 | 27% |

| Arkansas | 103 | 58% |

| California | 4,994 | 48% |

| Colorado | 198 | 23% |

| Florida | 4,606 | 63% |

| Hawaii | 344 | 65% |

| Illinois | 404 | 28% |

| Indiana | 75 | 11% |

| Kansas | 58 | 25% |

| Kentucky | 73 | 22% |

| Louisiana | 205 | 40% |

| Michigan | 111 | 10% |

| Mississippi | 2 | 3% |

| Nebraska | 42 | 25% |

| Nevada | 4,087 | 96% |

| New Mexico | 588 | 88% |

| New York | 560 | 22% |

| Ohio | 89 | 14% |

| Oklahoma | 1,515 | 94% |

| Oregon | 515 | 73% |

| Pennsylvania | 453 | 24% |

| Utah | 159 | 36% |

| Washington | 1,273 | 63% |

| Wyoming | 9 | 33% |

| Total | 20,483 | 38% |

Table 5.

Estimated Number and Percentage of Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) Health Care Providers Not Meeting NPI Taxonomy Credentialing Requirements

| State | Estimated Number of Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) Health Care Providers Not Meeting Credentialing Requirements | Estimated Percentage of Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) Health Care Providers Not Meeting Credentialing Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Alaska | 2 | 33% |

| California | 257 | 50% |

| Colorado | 4 | 7% |

| Louisiana | 3 | 11% |

| Maryland | 13 | 42% |

| Massachusetts | 53 | 54% |

| Nevada | 43 | 61% |

| New Mexico | 1 | 25% |

| New York | 38 | 43% |

| Oklahoma | 6 | 43% |

| Oregon | 1 | 6% |

| Washington | 5 | 8% |

| Total | 426 | -0.21% |

Table 6.

The NPI taxonomy classification, code, and description for behavior analysts between July 1, 2008, and January 1, 2016 (National Uniform Claim Committee, 2019a)

| Behavior Analyst – 103K00000X | |

| A Behavior Analyst is a practitioner who specializes in analysis of behavior problems and development of appropriate intervention and treatment plans. A Behavior Analyst may work independently or with a team of professionals. Behavior Analysts often specialize in a particular area such as autism, developmental disabilities, mental health, geriatrics, or head trauma. | |

| Source: National Uniform Claim Committee [7/1/2008: new] Additional Resources: Behavior Analysts may become Board Certified Behavioral Analysts (BCBA) through the Behavior Analysis Certification Board (BACB) www.bacb.com |

Table 7.

Current NPI taxonomy classifications, codes, and descriptions for behavior analysts (National Uniform Claim Committee, 2019b)

| Behavior Analyst – 103K00000X | |

| A behavior analyst is qualified by at least a master’s degree and Behavior Analyst Certification Board certification and/or a state-issued credential (such as a license) to practice behavior analysis independently. Behavior analysts provide the required supervision to assistant behavior analysts and behavior technicians. A behavior analyst delivers services consistent with the dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Common services may include, but are not limited to, conducting behavioral assessments, analyzing data, writing and revising behavior-analytic treatment plans, training others to implement components of treatment plans, and overseeing implementation of treatment plans. | |

| Source: Association of Professional Behavior Analysts, www.apbahome.net and Behavior Analyst Certification Board (http://www.bacb.com) [7/1/2008: new, 1/1/2016: modified definition] | |

| Assistant Behavior Analyst – 106E00000X | |

| An assistant behavior analyst is qualified by Behavior Analyst Certification Board certification and/or a state-issued license or credential in behavior analysis to practice under the supervision of an appropriately credentialed professional behavior analyst. An assistant behavior analyst delivers services consistent with the dimensions of applied behavior analysis and supervision requirements defined in state laws or regulations and/or national certification standards. Common services may include, but are not limited to, conducting behavioral assessments, analyzing data, writing behavior-analytic treatment plans, training and supervising others in implementation of components of treatment plans, and direct implementation of treatment plans. | |

| Association of Professional Behavior Analysts, www.apbahome.net and Behavior Analyst Certification Board (http://www.bacb.com) [7/1/2016: new] | |

| Behavior Technician – 106S00000X | |

| The behavior technician is a paraprofessional who practices under the close, ongoing supervision of a behavior analyst or assistant behavior analyst certified by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board and/or credentialed by a state (such as through licensure). The behavior technician is primarily responsible for the implementation of components of behavior-analytic treatment plans developed by the supervisor. That may include collecting data on treatment targets and conducting certain types of behavioral assessments (e.g., stimulus preference assessments). The behavior technician does not design treatment or assessment plans or procedures but provides services as assigned by the supervisor responsible for his or her work. | |

| Association of Professional Behavior Analysts, www.apbahome.net and Behavior Analyst Certification Board (http://www.bacb.com) [7/1/2016: new] |

Each of the three behavior-analytic taxonomy descriptions leaves room for health care providers to qualify under these codes if they hold, or are supervised by an individual holding, a state-issued credential to practice ABA. As of February 2019, there were 29 states that regulated the practice of ABA by offering state-issued licenses (APBA, 2019). In all of these states, individuals holding a credential from the BACB (i.e., Board Certified Behavior Analyst [BCBA] or Board Certified Behavior Analyst–Doctoral [BCBA-D]) qualified for the state’s behavior-analytic license(s) at the graduate level. Furthermore, individuals certified by the BACB at the undergraduate level (i.e., Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analysts [BCaBAs]) qualified for a state-issued license in the 22 states that regulated the profession at this level.4 At the time of this writing, in 14 of the 29 states regulating the practice of ABA, providers who did not hold a BACB certification may also qualify for a state-issued license at the graduate or undergraduate level.5 Therefore, it is possible that in some states, licensees may qualify under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) or Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) NPI codes without holding a BACB certificate. However, in the states where licensure for non-BACB certificants is available, the eligibility requirements appear to be equivalent to the requirements needed to sit and possibly pass the BACB examination. For example, New York requires passage of an examination deemed “acceptable” by the licensing board and the state education department but does not explicitly state which exams might qualify. Ultimately, licensing requirements vary depending on the state and are subject to updates. Details regarding the most recent licensing requirements can be found on state licensing board websites.

The inclusion of multiple taxonomies associated with the practice of ABA demonstrates the field’s growth in the health care industry. Unfortunately, NPPES explicitly states that it does not verify the credentials or qualifications of providers to ensure they are selecting appropriate taxonomies when applying for or updating their NPI information (CMS, 2019c). In other words, there is no verification system in place to ensure that health care providers meet the credentialing requirements listed in the behavior-analytic taxonomy descriptions. Furthermore, there is no clear incentive for health care providers to update their NPI account information on the NPPES website if they do not meet the credentialing requirements specified in the 2016 update to the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) taxonomy description.

If large numbers of providers are mistakenly identified as holding behavior-analytic credentials through their NPI taxonomy selections, it could have serious and unintended implications for researchers, families seeking ABA services, and other health care or education providers referring out for ABA services. Additionally, it could have implications for the health care industry as a whole (e.g., health departments, funders, private equity investors), which may use these data to determine network adequacy of ABA services. This study sought to investigate the concordance between health care providers utilizing the Behavior Analyst and Assistant Behavior Analyst NPI taxonomy classifications and providers who meet the credential qualifications specified in the code descriptions.

Method

Data and Sample

To complete this study, data were integrated from three sources: the BCBA/BCaBA Registry (BACB, 2019a), state registries for licensed behavior analysts, and the NPI file published by CMS (2019b).

Identifying BACB certificants

The BCBA/BCaBA Registry (BACB, 2019a) includes basic demographic information for all BCBA, BCBA-D, and BCaBA certificants. This information includes the certificant’s name, location, certification type, certification status, certification number, original certification date, recertification date, and certification expiration date. On May 16, 2019, data were extracted from the registry for certificants located in all 50 U.S. states (n = 33,362)6 using the steps described in Table 8. Data were loaded into Microsoft Excel and organized by BACB credential and state using pivot tables.

Table 8.

Task analysis used to generate BACB certificant databases from the BCBA/BCaBA Registry (BACB, 2019a)

|

1. Open a new file in the TextEdit application on the Apple Mac. 2. Click on “Format” in the top menu bar and select the “Make Plain Text” option (if it is not already selected). 3. Click on “Format” in the top menu bar and select the “Wrap to Window” option (if it is not already selected). 4. Resize the TextEdit window so it takes up half of the computer screen. 5. Open a new Google Chrome browser window. 6. Resize the Google Chrome browser window so it takes up the other half of the computer screen. 7. Go to www.bacb.com. 8. Click on the “Verify a Certificant” link. 9. Click on the “Find a BCBA” or the “Find RBT” link (depending on the database being compiled). 10. Under the “State (U.S. only)” header, select “Alabama” from the drop-down menu. 11. Click the “SEARCH” button. 12. When the pop-up box appears, click on the “I AGREE TO THESE TERMS” button. 13. Once the search results appear, right-click anywhere on the screen and select the “View Page Source” option. 14. After a new tab opens, press ⌘ and A to highlight all of the text. 15. Press ⌘ and C to copy all of the text. 16. Click on the TextEdit window and press ⌘ and V to paste all of the text from the browser window into the TextEdit window. 17. Close the tab in the Google Chrome browser with all of the code. NOTE: You do not need to go through each page. Just the first page. 18. Hit the back button on the browser to return to the registry. 19. Repeat Steps 11–19 to search through all 50 states. When pasting the content in the TextEdit file, just paste it directly where you last left off. 20. Once the text file is constructed, use the find and replace function in TextEdit to eliminate the HTML code in chunks. 21. Save the text file as a comma separated value (CSV) file. 22. Open the CSV file in Microsoft Excel and resave the document as an .xlsx file. |

Identifying state licensees without a BACB certificate

Given that 14 states (at the time of this writing) potentially offered licenses to practice ABA to those without a BACB certification, it was important to determine how many licensees were without certification. A multistep process was used to develop a list of current and active licensees at the graduate and undergraduate levels who could not be verified as holding a BACB certification. The first step involved identifying states that may allow non-BACB certificants to qualify for licensure at the graduate (e.g., Licensed Behavior Analyst) and undergraduate levels (e.g., Licensed Assistant Behavior Analyst).7 Fourteen states were identified using the February 2019 licensure overview table published by APBA (2019).8 During a 2-week period in late May and early June 2019, the names of licensees at the undergraduate level and graduate level were collected from these states by accessing publicly available online databases (Alaska, Arizona, Kansas, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington), contacting state licensing boards (Louisiana and Michigan), placing paid orders (North Dakota), and filing a Freedom of Information Act request (New York). If the state licensure data included a credential issuance date after February 28, 2019, that entry was removed, as this was the latest published original certification date listed in the BCBA/BCaBA Registry at the time of this writing. If an issuance date for a licensee was not available, the entry was included to provide more conservative estimates of total licensees. A total of 8,610 licensee names were identified and cross-referenced with the names in the BCBA/BCaBA Registry (BACB, 2019a) by using a matching formula in Excel. If a licensee’s name was not found in the registry (n = 1,334), an Internet search was performed of the name in quotes along with the BCBA title (i.e., “FirstName LastName” BCBA) to identify whether any evidence existed of a name change (e.g., change in marital status or use of a nickname). The updated name was then searched for again across states in the BCBA/BCaBA Registry (BACB, 2019a). These searches showed that 97% of the graduate licensees and 91% of the undergraduate licensees also held a BACB credential in these 14 states (see Table 3). These state-licensed, but unverified BACB-certified professionals in combination with the number of BCBA-Ds, BCBAs, and BCaBAs provided a conservative estimate across states of the number of health care providers who would meet the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) and Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) NPI code descriptions. For ease of reference, providers holding a state license to practice behavior analysis at the graduate level and BCBA/BCBA-D certificants will henceforth be referred to as “credentialed behavior analysts.” Similarly, state licensees at the undergraduate level in combination with BCaBA certificants will be referred to as “credentialed assistant behavior analysts.”

Identifying health care providers using behavior-analytic NPI taxonomies

NPI health care provider data were extracted from the NPPES downloadable file (a.k.a. “NPI file”) on April 8, 2019, using the steps described in Table 9. Due to the size of the NPI file (7.13 GB), a specialized program, CSV Explorer (2019), was used to open the original file and filter the results to include only providers who selected the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) or Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) NPI taxonomy. This list was migrated into Excel and further filtered to only include providers with NPIs granted on or before February 28, 2019. The number of health care providers by state was organized by NPI taxonomy using pivot tables in Excel.

Table 9.

Task analysis used to generate the behavior analysis NPI database from the NPPES downloadable file (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2019b)

|

1. Direct the browser to http://download.cms.gov/nppes/NPI_Files.html. 2. Open the downloaded zip file. 3. Upload the NPI data comma separated value (CSV) file (npidata_pfile_20050523-20190407.csv)a into the online program CSV Explorer (https://www.csvexplorer.com).b 4. Within the CSV Explorer program, filter the data set so it includes only entries with one or more of the following taxonomy codes: 103K00000X, 106E00000X, or 106S00000X. 5. Download the filtered data set from CSV Explorer and open it in Microsoft Excel. |

aThe exact data file name will vary depending on the date it is retrieved

bCSV Explorer is an online paid subscription program designed to allow users to interact with large data sets. As of April 1, 2019, the NPPES downloadable file consisted of almost 6 million rows of NPI data. This data set was uploaded to CSV Explorer and filtered so only rows that included the three taxonomy codes relevant to ABA were included

Data Analyses

Behavior Analyst (103K00000X)

An analysis was conducted to estimate how many Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) health care providers were credentialed across all 50 states. This involved comparing the estimated number of credentialed behavior analysts against the number of health care providers registered under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) NPI taxonomy. This estimate was based on the assumption that all credentialed behavior analysts have an NPI and were registered under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) taxonomy. Although this scenario is unlikely, it provided a conservative estimate that showed the overlap between the number of credentialed behavior analysts and the health care providers registered under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) taxonomy by state.

Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X)

A separate analysis was conducted to estimate how many Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) health care providers were credentialed in all 50 states. This involved comparing the estimated number of credentialed assistant behavior analysts against the number of health care providers registered under the Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) NPI taxonomy. This analysis was based on the assumption that all credentialed assistant behavior analysts hold an NPI and are registered under the Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) taxonomy. Once again, this scenario is unlikely, but it did provide a conservative estimate of the overlap between provider categories.

Results

Behavior Analyst (103K00000X)

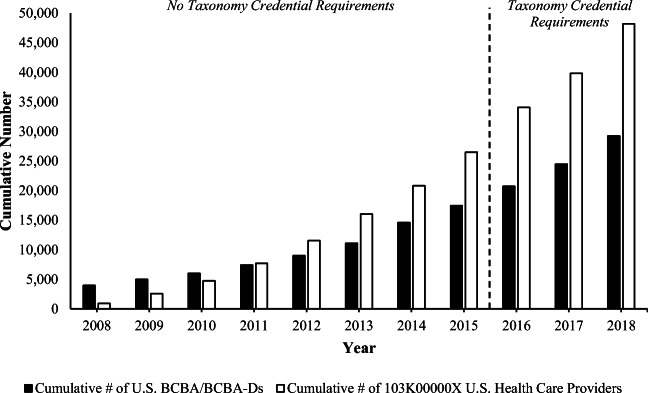

Figure 2 depicts the cumulative growth of BCBA/BCBA-Ds compared to the cumulative growth of health care providers registered under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) NPI taxonomy from 2008 to 2018.9 In 2008, there were 3,954 BCBAs/BCBA-Ds. In the same year, only 919 providers were registered in the NPI database, which represents only 23% of BCBAs/BCBA-Ds being registered providers. In 2018, the data show that there were 29,233 BCBAs/BCBA-Ds, whereas there were 48,169 registered providers in the NPI database. Thus, there are nearly 66% more Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) health care providers than BCBA/BCBA-D certificants in the BCBA/BCaBA Registry. Between 2008 and 2018, the number of BCBAs/BCBA-Ds increased steadily (639% total increase); during the same period, health care providers registering under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) taxonomy increased by 5,141%. Since the 2016 credentialing requirements, the number of health care providers registering under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) NPI taxonomy has steadily outpaced the BCBA/BCaBA Registry of BCBAs/BCBA-Ds.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative number of BCBA/BCBA-Ds and 103K00000X health care providers across states by original certification and NPI enumeration year. Taxonomy credential requirements refer to the BACB certification and/or state behavior-analytic licensure requirements added to the 103K00000X taxonomy definition on January 1, 2016

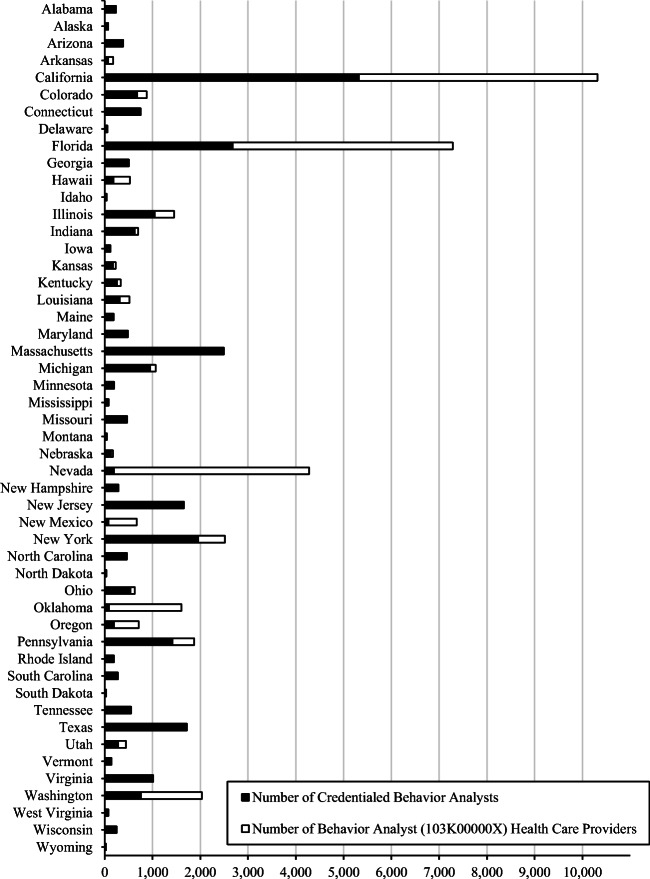

The overlap between credentialed behavior analysts and health care providers registered under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) NPI taxonomy in all 50 U.S. states is shown in Fig. 3. There are 38% more health care providers registered under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) taxonomy than BCBAs/BCBA-Ds identified in the BCBA/BCaBA Registry. In 24 states, there are more Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) health care providers than credentialed behavior analysts (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Overlap between credentialed behavior analysts and Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) health care providers across states

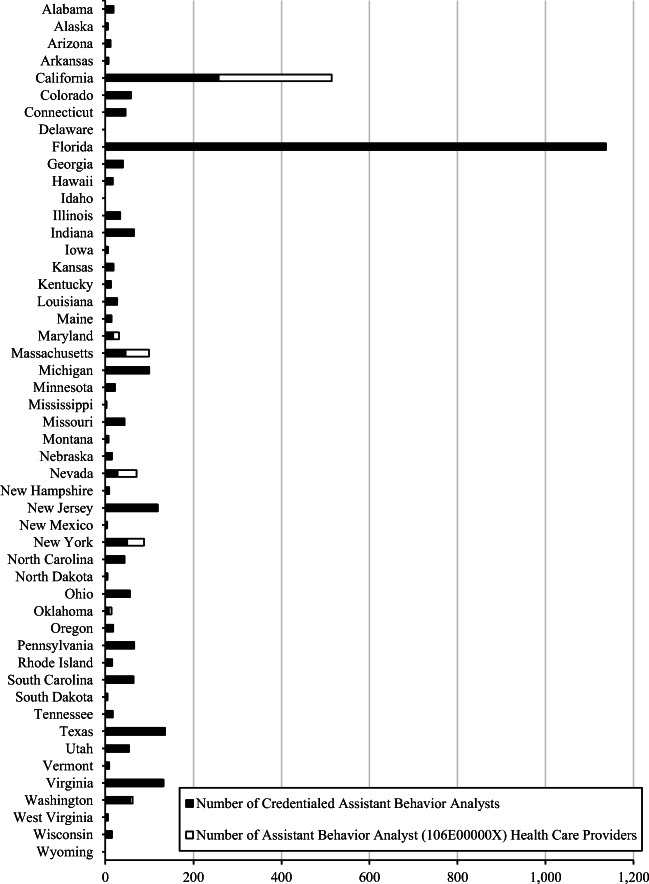

Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X)

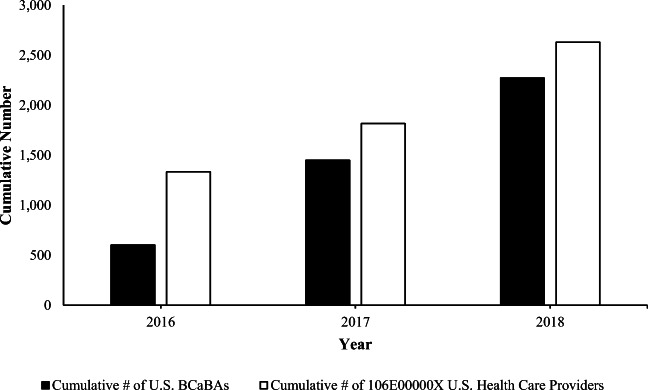

Figure 4 compares the cumulative growth of BCaBAs against the cumulative growth of health care providers registered under the Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) NPI taxonomy between 2016 and 2018. These data demonstrate that both the number of BCaBAs in the BCBA/BCaBA Registry and the number of Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) health care providers increased during this period. BCaBAs increased by 279%, whereas the number registered in the NPI database increased by 97%.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative number of BCaBAs and 106E00000X health care providers across states by original certification and NPI enumeration year

The overlap between credentialed assistant behavior analysts and health care providers registered under the Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) NPI taxonomy for all U.S. states is shown in Fig. 5. These data show that in total there are more credentialed assistant behavior analysts in the BCBA/BCaBA Registry than providers listed under the Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) NPI taxonomy. However, 12 states had more Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) health care providers than credentialed assistant behavior analysts (Table 5). Three states (Delaware, Idaho, and Wyoming) had no BCaBAs or Assistant Behavior Analysts (106E00000X) registered under the respective NPI taxonomy. Massachusetts and California had the greatest difference (54% and 50%, respectively) between providers in the NPI database and credentialed assistant behavior analysts.

Fig. 5.

The overlap between credentialed assistant behavior analysts and Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) health care providers across states

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the concordance between health care providers who utilize the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) and Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) NPI taxonomy classifications and health care providers who meet the credential qualifications specified in the code descriptions. An examination of the NPI database, the BCBA/BCaBA Registry, and state licensure data clearly demonstrates that there are significant discrepancies. Results indicate that an estimated minimum of 41% (n = 20,483) of U.S. health care providers registered under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) NPI taxonomy (n = 49,618) do not meet credentialing requirements specified in the code descriptions.

Nationally, this issue is not as pronounced for health care providers registered under the Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) NPI taxonomy. However, estimates differ by state. For example, the most conservative estimate suggests that more than 50% of health care providers registered under the Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) NPI taxonomy in California, Massachusetts, and Nevada do not meet credentialing requirements. What is clear from these data is that there are vast discrepancies based on the state in which the provider reportedly practices.

How These Results Affect Practice

There are several likely explanations for the detected discrepancies. First, when the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) NPI taxonomy was introduced in 2008, the taxonomy code description did not include credentialing requirements. Thus, it is likely that many health care providers met the original requirements but did not update their profiles on the NPPES website in 2016 when the credentialing requirements were added.10 It is also unclear whether CMS notified providers of this change and prompted providers to update their profiles accordingly. However, this explanation is not universal; since the adoption of the 2016 credentialing requirements, the number of providers registered under the taxonomy has increased at a faster rate than the number of new BCBA/BCBA-Ds (Fig. 2).

Second, when providers apply for an NPI and select their taxonomies, code descriptions are not visible, which may leave providers unaware of any credentialing requirements. Because there is no system for verifying whether providers meet credentialing requirements, these incorrect selections remain unchanged.

Third, although providers are required to update their NPPES profiles within 30 days of any changes, there is currently neither incentive for doing so nor penalty for not doing so. The most common updates are likely due to changes in professional affiliation, address, or marital status. However, changes to a taxonomy definition that result in a provider no longer meeting the credentialing requirements specified in the taxonomy should also result in profile updates.

Fourth, there appears to be a significant number of health care providers who consider themselves competent to practice ABA but have never qualified or passed the requisite BACB certification examinations. It is worthwhile to note that an unknown number of these providers may have received training in ABA outside the BACB track. For example, a health care provider may be trained in behavior analysis while enrolled within a separate but related program, such as psychology or marriage and family therapy. However, based on available data, there is no clear way to determine the extent, quality, or type of training these providers may have received. Furthermore, it is important to remember that a BACB credential is an entry-level credential in behavior analysis. Therefore, although some of these providers may have received some training in the field, they either did not receive enough to meet these widely recognized standards and pass an entry-level examination or did meet these standards but did not pass a BACB examination. Alternatively, there may be other health care providers within this same group of uncredentialed providers who do not consider their work to be behavior analytic but consider the behavior-analytic NPI taxonomies to be the closest to describing the types of services they are providing. This possibility is problematic for at least two reasons. First, it risks watering down the science and practice of behavior analysis as a distinct field with its own philosophies, theories, methodologies, and technologies. Second, there are ethical concerns around consumer protections for those claiming to be competent in ABA without having undergone formal training in the field (BACB, 2014; 2019b).

Finally, providers may deem the code they select as relatively unimportant, as it may be unclear to them how NPI taxonomy data are utilized. However, there are several reasons why accurate reporting and regular maintenance of publicly available NPI data, including taxonomies (National Uniform Claim Committee, 2019b), are important. Perhaps most important, as noted elsewhere (Bindman, 2013), a lack of accurate data could prohibit the evaluation of policies intended to improve access to services. Although CMS developed the NPI data set for administrative purposes, the utilization of NPI data for research on the workforce capacity of health care providers is becoming more frequent (Andrilla, Patterson, Barberson, Coulthard, & Larson, 2018; Miller, Petterson, Burke, Phillips, & Green, 2014; Miller, Petterson, Levey, et al., 2014b; Richman, Lombardi, & Zerden, 2018), and although improvements are needed, evidence indicates that the NPI data set is superior to other data sources in the accuracy of provider locations (e.g., Bell, Lòpez-DeFede, Wilkerson, & Mayfield-Smith, 2018). NPI data have other advantages as well. These data are provided by CMS monthly and are cost-free, instead of being restricted to certain providers (e.g., only physicians) or at cost. Additionally, it includes all health care providers with an NPI and their specialties, as well as all health care providers transmitting electronic claims or other health care information, not just providers who bill Medicare or just providers who bill Medicaid (Bindman, 2013; CMS, 2019b). Given these advantages, it is unfortunate that any research on behavior analysts that uses NPI data currently would appear to significantly overestimate the workforce capacity of credentialed behavior analysts.

This overestimation could have serious practical implications beyond research. For example, potential clients and their caregivers searching the Internet for qualified professionals may be misled into believing their provider holds a credential in ABA. There are several websites that draw upon the data shared in the publicly available NPI file to auto-populate webpages with provider information. This information may include any credentials providers are assumed to hold based on the NPI taxonomies selected. When one conducts an Internet search using a provider’s name, or simply searching for “behavior analysts” by location, results from websites such as Amwell (https://amwell.com), Healthgrades Operating Company, Inc. (https://www.healthgrades.com), HIPAASpace (https://www.hipaaspace.com), Medlio (https://medl.io), NPIdb (https://npidb.org), NPI No (https://npino.com), NPI Profile (https://npiprofile.com), and Providence Health and Services (https://www.providence.org) are often the first to appear. These websites appear to aggregate data from the NPI file and are designed to help identify qualified providers. Based on the results of the current study, this means that for each of these websites, there are at least 20,000 webpages that are identifying providers under these taxonomies implying that they have a credential to practice ABA. For example, at the top of NPIdb’s (2020) “Behavior Analyst – 103K00000X – Las Vegas, NV” webpage, it states, “A behavior analyst is qualified by at least a master’s degree and Behavior Analyst Certification Board certification and/or a state-issued credential (such as a license) to practice behavior analysis independently.” This definition is then followed by a list of provider names that are registered under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) NPI taxonomy, regardless of whether the providers listed actually have the credential mentioned at the top of the page.

Finally, there is limited evidence that suggests some states and health insurance companies may be using NPI taxonomy information to determine network adequacy (Network Adequacy Standards, 2016). For example, the network adequacy website operated by the Arkansas Insurance Department (2015, 2020) includes several documents describing the use of NPI taxonomy data to make network adequacy determinations. Within those documents, the Behavior(al) Analyst taxonomy is listed along with other provider taxonomies under the “Access to Mental Health/Behavioral Health Providers” category. The Behavior Analyst taxonomy data also appear to be used in determining network adequacy in the state of Washington based on a report submitted to the Washington State Health Care Authority (Rojeski, Morris, Orfield, Satake, & Postman, 2017). If these data are being used to evaluate access to health care, it could impact how insurance companies are negotiating rates with in-network and out-of-network providers. Unfortunately, the processes used by states and funders to determine network adequacy vary and are often not publicly available. Therefore, although there is some evidence suggesting NPI taxonomy data are used to determine network adequacy, further confirmation and evidence are needed to demonstrate the extent of this possible issue.

Next Steps

The NPI database includes a list of names and mailing addresses for all providers using the behavior analyst taxonomies. To address this issue, perhaps the first step is a mailing campaign informing providers of the 2016 credentialing requirements under the behavior-analytic NPI taxonomies and providing them with information on how to update their accounts on the NPPES website. This strategy would not solve the issue entirely, as it is unknown how many providers do not update their NPI account information. In other words, it is possible that some of these notices would not reach the intended providers. Relatedly, in August 2019, the BACB published an article in their newsletter that explained how to monitor and update NPI information. This article was a good step toward educating providers, but its primary audience is BACB certificants who already meet the eligibility requirements to use the behavior analyst taxonomies.

As others have previously suggested (Bindman, 2013), CMS could also require providers to update their NPPES profiles regularly, as is required for other federal databases. Additionally, CMS could develop a system for validating providers’ taxonomy selections. As licensure is established across states, CMS could also update the NPPES website so that it requires health care providers to list the license number and state in which it was issued when selecting the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) and Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) taxonomies. Currently, these fields are available but not required when selecting a taxonomy (Fig. 1). There appears to be precedence to make this update because these fields become required when selecting other taxonomies. For example, health care providers are required to enter a license number and state when selecting the Psychologist – Clinical (103TC0700X) and Pediatrics (208000000X) taxonomies. However, this change would not be desirable until all U.S. states and territories establish licensure, as it could unfairly lock out qualified, BACB-credentialed providers who are not licensed. It is doubtful this suggestion would completely eliminate providers from selecting the wrong taxonomy, but it might discourage nonqualified providers from making this selection initially.

Limitations

There are several limitations to the current study. First, these analyses were based on the assumption that all credentialed behavior analysts work in settings that require a registered NPI number; however, this assumption is unlikely based on the results from the BACB’s February 2016 Job Task Analysis survey. Data from this survey indicated that a significant percentage of BCBAs reported practicing in areas outside of health care, which would not require obtaining an NPI number (BACB, n.d.). For example, 12.2% of BCBA survey respondents reported “education” as their practice area, and services provided in schools are not regulated through HIPAA. These data suggest that approximately 82% of BCBA certificants may qualify as a covered entity under HIPAA and thus have registered for an NPI number.11 Based on this assumption, rather than the estimated 20,483 health care providers who would not have met the credentialing requirements under the taxonomy description, the estimate would increase to 24,753, or 49% of all health care providers claiming the taxonomy.12

Second, although health care providers are required to update their NPI information on the NPPES website within 30 days of any changes, there are no consequences or programmed reminders to do so. As a result, the accuracy of the data included in the NPI file is questionable. Health care providers rarely work for the same employer for the entirety of their careers, and major life events such as marriage, divorce, and promotion can lead to name and address changes that are not reflected in the NPI file. For example, a name match analysis was conducted comparing the first and last names of credentialed behavior analysts against Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) health care providers across states. From this analysis, an estimated 30,683 (62%) of Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) health care providers across states lacked the credentials required in the taxonomy code. Results of a similar analysis comparing credentialed assistant behavior analysts with Assistant Behavior Analyst (106E00000X) health care providers demonstrated that 1,765 (73%) of these providers at the national level did not meet the credentialing requirements required in the taxonomy code.

Finally, the data presented excluded an analysis of the Behavior Technician (106S00000X) taxonomy code. Unfortunately, space limitations prevented the inclusion of an analysis of this taxonomy and the unique issues it presents. Currently, there are no credential requirements for health care providers choosing this taxonomy. However, based on the taxonomy definition included with this code, providers are to be supervised by a credentialed behavior analyst.

Future Research

Future research in this area should consider examining the number of health care providers falling under the Behavior Technician (106S00000X) taxonomy and comparing it against the number of credentialed behavior analysts who could possibly provide supervision. Doing so might provide some insight into whether a similar problem exists at the behavior technician level.

Additionally, future research should investigate those states that appear to have the most significant discrepancies between the number of credentialed behavior analysts and Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) health care providers. It is not yet clear whether there is a common variable or variables that would account for so many uncredentialed behavior analysts registering under the Behavior Analyst (103K00000X) taxonomy.

Finally, more information about how states, funders, and investors use NPI taxonomy data is needed. Some evidence was gathered and presented earlier, but a more thorough analysis is needed to help gauge the extent and significance of the problem. For example, a member of the BACB’s leadership team recently reported attending a meeting at a professional conference that included private equity investors. During the meeting, these investors indicated that one metric used to help determine the market value of the behavior-analytic organizations they were evaluating is NPI taxonomy data (M. Nosik, personal communication, December 9, 2019). If these types of investment decisions are being influenced by data collected from the NPI file, it could result in serious financial implications for these organizations.

Conclusion

It is clear that more work is required to balance the practice of ABA between the field’s credentialing bodies and the NPI registry. Ensuring that the NPI database presents accurate information of those who are credentialed, and thereby regulated, is important. The progress that the field has made in the health care domain is encouraging. It is important to safeguard clients and the profession by promoting the highest standards of quality. One way to achieve this goal is to ensure that those who advertise the provision of ABA are qualified to provide such a service.

Funding

No funding was provided for this project.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This project was submitted to the University of Louisville Human Subjects Protection Program and was deemed to not meet the “Common Rule” definition of human subjects research. As such the project did not require institutional review board review.

Informed Consent

This project did not utilize any human subjects and relied on publicly available data sets.

Footnotes

In some instances, an individual health care provider who is also incorporated may need to obtain an NPI as an individual and as an organization. Individual health care providers may only obtain a single NPI; however, organizations may be eligible for multiple NPIs (Medicare Learning Network, 2016).

NPPES provides a link to the Washington Publishing Company (WPC) website on the taxonomy section of the NPI application page (www.wpc-edi.com/reference). Applicants can use this link to navigate the WPC website to find taxonomy descriptions.

Prior to October 2019, the NPPES incorrectly listed the “Behavior Analyst” taxonomy classification as “Behavioral Analyst” in their registry and when applying for a new NPI number. The issue was brought to the attention of CMS by the first author and appears to have been corrected. Regardless, old records may still be found online with the incorrect label.

BACB certification is the primary qualification for licensure across states. However, additional minor requirements beyond licensure application fees are also sometimes involved (e.g., additional hours of ethics training, background checks, additional state examinations).

The licensing language included in some state statutes is not always clear on whether a non-BACB certificant can qualify for a license to practice ABA.

Both active (n = 32,870) and inactive (n = 492) BACB certificants were included in count totals because some state licensing laws only specify that an applicant for licensure pass a BACB examination, and do not clearly state whether or not the licensee needs to maintain his or her BACB credential. Of the total BACB certificant pool examined, only 1.5% were identified as inactive.

Behavior analysis licensure laws at the graduate and undergraduate levels use various titles depending on the state (e.g., behavior analyst, licensed behavior analyst, applied behavior analyst, assistant behavior analyst, licensed behavior analyst, certified assistant behavior analyst, registered assistant behavior analyst).

States where the law was unclear on whether or not a non-BACB provider may qualify for a credential to practice ABA were included in this analysis to provide the most conservative estimate possible.

This figure does not include annual data for non-BACB licensees. However, as 97% of graduate licensees were assumed to hold a BACB credential at the time of this analysis, the exclusion of these numbers is unlikely to have a large impact on the overall data trends shown.

The publicly available NPI file does provide a date for when an NPI account was last updated. However, this information is limited, as it does not indicate how the account was updated.

This value takes into consideration BCBAs who reportedly work in the following practice areas: autism (67.65%), developmental disabilities (8.33%), behavioral medicine (2.08%), other (2.12%), behavioral pediatrics (0.69%), brain injury rehabilitation (0.58%), child welfare (0.38%), and behavioral gerontology (0.14%).

Job task survey data were not available at the BCaBA level, so a similar analysis was not conducted.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Andrilla CHA, Patterson DG, Garberson LA, Coulthard C, Larson EH. Geographic variation in the supply of selected behavioral health providers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2018;54(6):S199–S207. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkansas Insurance Department. (2015). Rules based data drive network adequacy: Review and regulation (v.1). Retrieved from http://rhld.insurance.arkansas.gov/Downloadables/NetworkAdequacy/100_ProcessRequirementsDocumentation/100_Arkansas%20Network%20Adequacy%20Architecture.pdf

- Arkansas Insurance Department. (2020). RHLD: Network Adequacy Regulation Program. Retrieved from http://rhld.insurance.arkansas.gov/NetworkAdequacy

- Association of Professional Behavior Analysts. (2019). Overview of state laws to license or otherwise regulate practitioners of applied behavior analysis. Retrieved from https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.apbahome.net/resource/resmgr/pdf/state_regulation_of_ba_feb20.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board . Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. Littleton, CO: Author; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2019a). BCBA/BCaBA registry. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/services/o.php?page=100155

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2019b). Protect your NPI number and certification information from fraud. BACB Newsletter. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/BACB_August2019_Newsletter-.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.). BACB certificant data. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data

- Bell, N., Lòpez-DeFede, A., Wilkerson, R. C., & Mayfield-Smith, K. (2018). Precision of provider licensure data for mapping member accessibility to Medicaid managed care provider networks. BMC Health Services Research, 18(974), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bindman AB. Using the National Provider Identifier for health care workforce evaluation. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review. 2013;3(3):E1–E19. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.03.b03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2019a). Crosswalk Medicare provider/supplier to healthcare provider taxonomy [Data file]. Retrieved from https://data.cms.gov/Medicare-Enrollment/CROSSWALK-MEDICARE-PROVIDER-SUPPLIER-to-HEALTHCARE/j75i-rw8y

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2019b). NPPES data dissemination. Retrieved from http://download.cms.gov/nppes/NPI_Files.html

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2019c). Taxonomy. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/MedicareProviderSupEnroll/Taxonomy.html

- CSV Explorer [Computer software]. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.csvexplorer.com

- HIPAA Administrative Simplification: Standard Unique Health Identifier for Health Care Providers, 45 C.F.R. § 162 (2004). [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine . Beyond the HIPAA privacy rule: Enhancing privacy, improving health through research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Learning Network. (2016). NPI: What you need to know. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/NPI-What-You-Need-To-Know.pdf

- Medicare Learning Network. (2019). Healthcare provider taxonomy codes (HPTCs) April 2019 code set update. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/Downloads/MM11121.pdf

- Miller, B. F., Petterson, S., Burke, B. T., Phillips Jr., R. L., & Green, L. A. (2014). Proximity of providers: Colocating behavioral health and primary care and the prospects for an integrated workforce. American Psychologist, 69(4), 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miller BF, Petterson S, Levey SMB, Payne-Murphy JC, Moore M, Bazemore A. Primary care, behavioral health, provider colocation, and rurality. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2014;27(3):367–374. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.03.130260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Uniform Claim Committee. (2019a). Health care provider taxonomy code set CSV (Version 9.0, 1/1/09). Retrieved from http://www.nucc.org/index.php/code-sets-mainmenu-41/provider-taxonomy-mainmenu-40/csv-mainmenu-57

- National Uniform Claim Committee. (2019b). Health care provider taxonomy code set CSV (Version 19.0, 1/1/19). Retrieved from http://www.nucc.org/index.php/code-sets-mainmenu-41/provider-taxonomy-mainmenu-40/csv-mainmenu-57

- Network Adequacy Standards, 45 C.F.R. § 156.230 (2016).

- NPIdb. (2020). Behavior analyst – 103K00000X – Las Vegas, NV. Retrieved from https://npidb.org/doctors/behavioral_health/behavior-analyst_103k00000x/nv/?location=las+vegas&page=2

- Oatway DM. Get ready for National Provider Identifiers. Nursing Homes: Long Term Care Management. 2006;55(11):70–71. [Google Scholar]

- Richman EL, Lombardi BM, Zerden LDS. Where is behavioral health integration occurring? Mapping national co-location trends using National Provider Identifier data. Ann Arbor, MI: Behavioral Health Workforce Research Center, University of Michigan School of Public Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rojeski J, Morris E, Orfield C, Satake M, Postman C. Washington State Health Care Authority provider network adequacy analysis. Cambridge, MA: Mathematica Policy Research; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Washington Publishing Company. (2019). Health care provider taxonomy code set: ASC X12 External code source 682. Retrieved from http://www.wpc-edi.com/reference/codelists/healthcare/health-care-provider-taxonomy-code-set/