Abstract

We performed a retrospective analysis of DLBCL with breast involvement to compare the prognosis of primary breast lymphoma (PBL) to secondary breast lymphoma (SBL; especially in limited stage cases). We retrospectively reviewed records of 25 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients with breast involvement who received chemotherapy between January 2000 and August 2012. We compared clinical features and prognosis among patients with PBL (n = 11), limited stage SBL (LSBL; n = 6), and advanced stage SBL (ASBL, n = 8). The PBL group had significantly lesser patients with breast tumours (BTs) > 5 cm than the SBL group (P = 0.02). After a median follow-up of 71.3 months, we observed significantly better 5-year overall survival (OS) in the PBL group (90.0%) than in the LSBL (33.3%, P = 0.01) group, but not for progression-free survival (PFS). Patients with BT > 5 cm had worse OS (P = 0.01) and PFS (P = 0.04) than those with BT ≤ 5 cm. PBL had a better prognosis than SBL among limited stage DLBCL.

Keywords: Primary breast lymphoma, Secondary breast lymphoma, Breast tumor, Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Introduction

Breast lymphoma is a rare subgroup, which accounts for 2.2% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and 0.5% of breast malignancies [1, 2]. Patients frequently have central nervous system (CNS) involvement at the time of relapse [3], which leads to a poor prognosis [4]. While the definition of primary breast lymphoma (PBL) depends on the pathology report, the criteria by Wiseman and Liao [5] define it as a ‘limited stage breast lymphoma with/without ipsilateral axially node lesion’. Since then, there have been numerous reports that of patients diagnosed with PBL. Ryan et al. [6] have conducted a retrospective survey of 204 PBL patients who had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) pathology. The results showed that these patients had relatively good prognosis with a median overall survival (OS) of 8 years and progression-free survival (PFS) of 5.5 years. Other researchers also reported a favorable prognosis for patients with PBL [7]. On the other hand, Lin et al. [8] defined breast lymphomas that do not fulfil the criteria for PBL as having ‘secondary involvement of the breast by systemic lymphoma’ or secondary breast lymphoma (SBL). Lin et al. compared the prognosis of 23 PBL patients and 19 SBL patients. The results showed a significantly better 5-year event-free survival (EFS) of 50.2% for PBL patients than 25.2% for SBL patients (P = 0.00036). PBL patients had an OS of 83.3% compared to 25.2% for SBL patients (P = 0.0001). However, the SBL patients in their report included patients with advanced stage disease. The difference between PBL and limited stage SBL has yet to be elucidated. Here, we performed a retrospective analysis of DLBCL with breast involvement to compare the prognosis of PBL to SBL (especially in limited stage cases).

Materials and Methods

We included DLBCL patients who had pathological diagnoses of breast lesions and presented to nine Japanese affiliate institutions of the Yokohama Cooperative Study Group for Hematology (YACHT) between January 2000 and August 2012. Patients’ background [age, sex, clinical stage, International Prognostic Index (IPI) score, tumor size] and survival data were collected from the patients’ medical records and retrospectively analysed. Pathologists from each institution provided the pathological diagnosis of DLBCL. Clinical stage was determined by computed tomography and/or positron-emission tomography and bone marrow biopsy based on the Ann Arbor (AA) staging system. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kanagawa Cancer Center.

We defined PBL as ‘limited stage (AA stage I and II) breast DLBCL with or without ipsilateral axially node lesion’ and SBL as ‘other breast DLBCL’. The SBL patients were subdivided into limited stage (LSBL) and advanced stage (ASBL; AA stage III and IV). Patients with bilateral breast lesions were defined as PBL and clinical stage II.

Statistical Analysis

The Mann–Whitney U test was used for statistical comparison of patients’ backgrounds. OS was defined as the period from the start of treatment to death by any reason. PFS was defined as the period from start of treatment to progression or any death. We drew a survival curve by the Kaplan–Meier method and performed univariate analysis by the log-rank test. P values < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. We used EZR on R commander (ver. 1.41, 2019) [9] for statistical analyses.

Results

Among 1264 DLBCL patients during the study period, 25 patients had pathological confirmation of their biopsied breast lesions. Table 1 lists the patients’ (n = 25) baseline characteristics. There were 11 (45%) PBL patients, 6 (24%) LSBL, and 8 (32%) ASBL. The patients’ median age was 60 years (range: 41–87 years) and there was no significant difference in background among the subgroups. The ASBL group included one male patient. We observed significantly fewer patients with large masses over 5 cm in the PBL group (1/11; 9%) than in the LSBL (3/6; 50%) and ASBL (5/8; 63%) groups, as an indicator of poor prognosis. The ASBL group had 5 (68%) high or high-intermediate IPI patients. The other groups did not have any high or high-intermediate IPI patients. The PBL group had 5 stage I (breast lesion only) and 6 stage II (positive for ipsilateral axially node lesion) patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and treatment of breast lymphoma patients

| Characteristics or therapeutic factors | Total number of patients n = 25 | Limited | Advanced | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBL n = 11 | LSBL n = 6 | ASBL n = 8 | |||

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median (range) | 59 (41–85) | 59 (41–85) | 60 (42–85) | 59 (53–82) | |

| At most 60 | 14 | 7 | 3 | 4 | NS |

| Over 60 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 24 | 11 | 6 | 7 | NS |

| Male | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Tumor size | |||||

| At most 5 cm | 16 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0.03 |

| Over 5 cm | 9 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |

| LDH | |||||

| Normal | 11 | 6 | 4 | 1 | NS |

| Elevated | 14 | 5 | 2 | 7 | |

| ECOG performance status | |||||

| 0–1 | 22 | 10 | 5 | 7 | NS |

| 2–4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ann Arbor clinical stage | |||||

| 1 | 5 | 5 | – | – | – |

| 2 | 12 | 6 | 6 | – | |

| 3 | 4 | – | – | 4 | |

| 4 | 4 | – | – | 4 | |

| IPI score | |||||

| Low, low-intermediate | 20 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 0.001 |

| High, high-intermediate | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Initial treatment | |||||

| CHOP × 3 − 4 + IFRT | 2 | 0 | 0 | – | |

| CHOP × 6 − 8 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||

| R-CHOP × 3 − 4 + IFRT | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| R-CHOP × 6 − 8 (+ IFRT) | 6 (1) | 4 (0) | 8 | ||

| Response rate | 82% | 100% | 88% | ||

| CNS prophylaxis (IT) | 3 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Outcome | |||||

| Relapse/progression | 5 (45%) | 3 (50%) | 3 (38%) | ||

| CNS progression | 3 (27%) | 1 (17%) | 0 | ||

| Death | 2 (18%) | 4 (66%) | 3 (38%) | ||

PBL primary breast lymphoma, LSBL limited secondary breast lymphoma, ASBL advanced secondary breast lymphoma, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, IPI International Prognostic Index, IFRT involved field radiation therapy, CNS central nervous system

Table 1 lists the initial treatment, response, and outcome for the study patients. All patients received the chemotherapy regimen of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) or CHOP-like therapy with or without rituximab. Three PBL patients received irradiation after the chemotherapy. There were 6 (75%) patients with advanced stage disease who received intrathecal methotrexate (MTX) administration for CNS prophylaxis. Only 1 patient in the PBL group and 3 patients in the LSBL groups received intrathecal MTX for CNS prophylaxis.

The median observation period was 71.3 months (range: 46.3–140.8 months) for surviving patients. Of these, 11 (44%) experienced relapse and had a 5-year PFS of 52.0% (31.2–69.2) and OS of 68.0% (46.1–82.5) as seen in Fig. 1 a, b.

Fig. 1.

Survival in the breast lymphoma patients’ cohort (n = 25). a OS. b PFS. OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival

CNS progression was noted in 3 (27%) PBL patients and 1 (17%) LSBL patients. None of the ASBL patients had CNS progression. Table 2 lists the detailed information of patients with CNS-relapse. CNS progression occurred in relatively young patients (median: 53 years), with low risk IPI disease, and without CNS prophylaxis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with CNS progression

| Age (years)/gender | Primary site | Type of breast lymphoma | Tumor size (cm) | IPI | Primary treatment | CNS prophylaxis | Primary response | PFS [months] | Relapsed site | Salvage therapy | ASCT | Survival from relapse [months] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 53F | Rt. breast | PBL | 4.5 | L | CHOP3 + IFRT | None | CR | 25.5 | CNS | WBI, HD-MTX | Yes | 115.3+ |

| #2 | 49F |

Lt. breast, Lt. axial LN, Mediastinal LN |

LSBL | 10.0 | L | R-CHOP4 | None | CR | 29.3 | CNS | WBI | Yes | 14.3 |

| #3 | 53F | Lt. breast | PBL | 3.0 | L | R-CHOP5 | None | PD | 3.5 | CNS | WBI, HD-MTX+Ara-C | No | 70.6 |

| #4 | 41F | Bil. Breast, Lt. axial LN | PBL | 3.0 | L | CHOP4 + IFRT | None | CR | 16.1 | CNS, BM, PB | HD MTX | No | 13.8 |

IPI International Prognostic Index, PFS progression-free survival, ASCT autologous stem cell transplantation, Rt. right, Lt. left, Bil. bilateral, PBL primary breast lymphoma, LSBL limited secondary breast lymphoma, L low risk, CR complete remission, LN lymph node, PD progressive disease, CNS central nervous system, BM bone marrow, PB peripheral blood, WBI whole brain irradiation, HD-MTX high dose methotrexate, NA not applicable, ML malignant lymphoma, Ara-C cytarabine

While all relapsed patients with LSBL and ASBL died from lymphoma, only 2 out of 5 (20%) PBL patients died from lymphoma. Interestingly, 2 out of 3 (66%) PBL patients with CNS relapse have survived over 5 years since relapse.

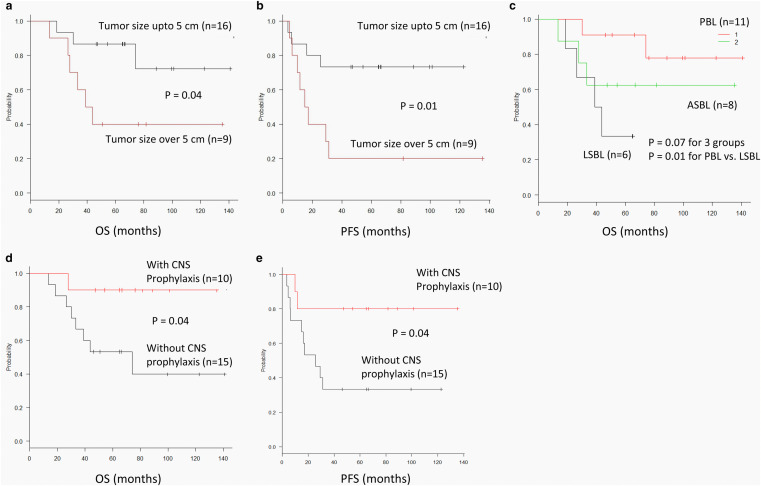

Table 3 shows the univariate analysis of the baseline factors for survival. Tumor size over 5 cm was significantly prognostic for OS (P = 0.04) and PFS (P = 0.01, Fig. 2a, b). In terms of type of lymphoma, there was only a trend in difference in OS among the 3 subtypes (P = 0.07, Fig. 2c). However, among limited stage cases, PBL patients showed significantly better OS than LSBL patients (P = 0.01, Fig. 2c), but not for PFS. Although the difference in occurrence of CNS relapse was not significant between patients with or without CNS prophylaxis, a favorable prognostic impact was seen for both OS and PFS (P = 0.04 for both; Fig. 2d, e).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of survival

| Patient no. | 5-year PFS % | Log rank P-value | 5-year OS % | Log rank P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 25 | 52.0 (31.2–69.2) | 68.0 (46.1–82.5) | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| Up to 60 | 14 | 42.9 (17.7–66.0) | NS | 64.3 (34.3–83.3) | NS | ||

| Over 60 | 11 | 63.6 (29.7–84.5) | 72.7 (37.1–90.3) | ||||

| Tumor size | |||||||

| Up to 5 cm | 16 | 73.3 (43.6–89.1) | 0.01 | 86.7 (56.4–96.5) | 0.04 | ||

| Over 5 cm | 9 | 20.0 (3.1–47.5) | 40.0 (12.3–67.0) | ||||

| LDH | |||||||

| Normal | 11 | 63.6 (29.7–84.5) | NS | 81.8 (44.7–95.1) | NS | ||

| Elevated | 14 | 42.9 (17.7–66.0) | 57.1 (28.4–78.0) | ||||

| ECOG performance status | |||||||

| 0–1 | 22 | 54.5 (32.1–72.4) | NS | 72.7 (49.1–86.7) | NS | ||

| 2–4 | 3 | 33.3 (0.9–77.4) | 33.3 (0.9–77.4) | ||||

| Ann Arbor clinical stage | |||||||

| Limited | 17 | 47.1 (23.0–68.0) | NS | 70.6 (43.1–86.6) | NS | ||

| Advanced | 8 | 62.5 (22.9–86.1) | 62.5 (22.9–86.1) | ||||

| Type of breast lymphoma | |||||||

| PBL | 11 | 54.5 (22.9–78.0) | NS | NS | 90.9 (50.8–98.7) | 0.01 | NS |

| LSBL | 6 | 33.3 (4.6–67.6) | 33.3 (4.6–67.6) | ||||

| ASBL | 8 | 62.5 (22.9–86.1) | 62.5 (22.9–86.1) | ||||

| CNS prophylaxis (IT) | |||||||

| Yes | 10 | 80.0 (40.9–94.6) | 0.04 | 90.0 (47.3–98.5) | 0.04 | ||

| No | 15 | 33.3 (12.2–56.4) | 53.3 (26.3–74.4) | ||||

PFS progression free survival, OS overall survival, NS not significant, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, IPI International Prognostic Index, PBL primary breast lymphoma, LSBL limited secondary breast lymphoma, ASBL advanced secondary breast lymphoma

Fig. 2.

Subgroup survival analysis. a OS for maximum tumor sizes of ≤ 5 cm or > 5 cm. b PFS for maximum tumor sizes of ≤ 5 cm or > 5 cm. c OS among 3 breast lymphoma subtypes. d OS with or without CNS prophylaxis. e PFS with or without CNS prophylaxis. f OS with or without CNS relapse. OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, PBL primary breast lymphoma, LSBL: Limited secondary breast lymphoma, ASBL advanced secondary breast lymphoma, CNS central nervous system

Discussion

PBL has been reported to have better prognosis among breast lymphomas and, according to Lin et al. patients with PBL appear to have a relatively better prognosis than patients with SBL [8]. However, their study cohort included several subtypes of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and the SBL cohort included advanced stage patients. The prognostic significance of PBL among limited stage breast DLBCL patients has not been determined. In the present study, we analyzed 25 DLBCL patients with breast lesions and observed that PBL patients had significantly better prognosis among limited stage patients. We followed the original definition of PBL by Wiseman and Liao [5] which has been generally used. Other definitions include advanced stage patients with an assumed primary breast lesion (e.g., breast lesion and bone marrow involvement). Limited stage patients who did not fulfil the PBL criteria (LSBL) had cervical lymph nodes and/or contralateral axially lymph nodes as additional lesions. While there were no significant differences for age, serum LDH, and IPI scores between PBL and LSBL patients, there were significantly less patients with tumor sizes over 5 cm in the PBL group (n = 1) compared to the LSBL group (n = 7, P = 0.03).

A retrospective analysis of 14 PBL-DLBCL patients by Fukuhara et al. [10] showed a negative prognostic impact of tumor size over 5 cm for both OS (P = 0.04) and PFS (P = 0.01). The difference in numbers of patients with larger tumors in both groups might have affected the survival in our cohort.

All patients in the present study underwent CHOP or a CHOP-based regimen with or without rituximab. In addition, a few patients received focal irradiation. While a randomized study of 98 PBL-DLBCL patients [11] in the pre-rituximab era showed the efficacy of combined chemoradiotherapy, optimal treatment and impact of irradiation for PBL has yet to be established. Some reports suggest that the majority of PBL-DLBCL include the non-GCB molecular subtype. Standard rituximab-CHOP (R-CHOP) might be insufficient for this group [12]. In our cohort, only 4 patients, including 3 PBLs, received initial treatment without rituximab. Thus, the impact of the addition of rituximab to CHOP for breast lymphoma patients was not assessed.

In this study, there was no significant difference in the proportion of CNS relapse in both subgroups (27% vs. 17%), yet it was much higher than the general DLBCL cohort. Avilés et al. [11] reported a high incidence (11.5%), and a report from a Japanese nationwide survey by Tomita et al. [3] suggested breast involvement to be one of the important risk factors of CNS relapse among DLBCL patients (multivariate HR = 10.5). The efficacy of CNS prophylaxis with additional intrathecal MTX or high dose MTX has been suggested, but not established, as a standard treatment [13, 14]. In our study, none of the patients with CNS relapse received CNS prophylaxis. Patients without prophylaxis had a significantly poor prognosis (Fig. 2), which supported the necessity for the treatment, irrespective of IPI risk. Some PBL patients in our cohort showed long-term remission and survival even after CNS relapse (Table 3), which suggested a unique biology compared with other breast DLBCL.

Our study had several limitations due to the small numbers of patients, with a retrospective setting, and lack of a central review of the pathological diagnosis with detailed information including cell of origin/gene expression profile data, which is important to understand the lymphoma biology better. However, to our knowledge, this is the first report to show the favorable prognosis of PBL even compared with limited stage SBL.

Conclusion

We have found that diagnosis of PBL-DLBCL, according to the original definition, is suggestive of a relatively favorable prognosis among breast lymphoma patients. Further prospective assessment of patients’ data and more detailed pathological analysis is warranted.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (https://www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Aviv A, Tadmor T, Polliack A. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the breast: looking at pathogenesis, clinical issues and therapeutic options. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(9):2236–2244. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheah CY, Campbell BA, Seymour JF. Primary breast lymphoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(8):900–908. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomita N, Yokoyama M, Yamamoto W, Watanabe R, Shimazu Y, Masaki Y, et al. Central nervous system event in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(2):245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talwalkar SS, Miranda RN, Valbuena JR, Routbort MJ, Martin AW, Medeiros LJ. Lymphomas involving the breast: a study of 106 cases comparing localized and disseminated neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(9):1299–1309. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318165eb50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiseman C, Liao KT. Primary lymphoma of the breast. Cancer. 1972;29(6):1705–1712. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197206)29:6<1705::AID-CNCR2820290640>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan G, Martinelli G, Kuper-Hommel M, Tsang R, Pruneri G, Yuen K, et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the breast: prognostic factors and outcomes of a study by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(2):233–241. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jia Y, Sun C, Liu Z, Wang W, Zhou X. Primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a population-based study from 1975 to 2014. Oncotarget. 2018;9(3):3956–3967. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin YC, Tsai CH, Wu JS, Huang CS, Kuo SH, Lin CW, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcome of non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the breast—a review of 42 primary and secondary cases in Taiwanese patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50(6):918–924. doi: 10.1080/10428190902777475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukuhara S, Watanabe T, Munakata W, Mori M, Maruyama D, Kim SW, et al. Bulky disease has an impact on outcomes in primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the breast: a retrospective analysis at a single institution. Eur J Haematol. 2011;87(5):434–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avilés A, Delgado S, Nambo MJ, Neri N, Murillo E, Cleto S. Primary breast lymphoma: results of a controlled clinical trial. Oncology. 2005;69(3):256–260. doi: 10.1159/000088333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niitsu N, Okamoto M, Nakamine H, Hirano M. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcome of primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2008;32(12):1837–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludmir EB, Milgrom SA, Pinnix CC, Gunther JR, Westin J, Oki Y, et al. Primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: treatment strategies and patterns of failure. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59(12):2896–2903. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2018.1460825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu S, Song Y, Sun X, Su L, Zhang W, Jia J, et al. Primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: therapeutic strategies and patterns of failure. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(12):3943–3952. doi: 10.1111/cas.13828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]