Abstract

Background:

Mainstream Islam prohibits alcohol and other drugs, yet substance use is prevalent in Muslim-American communities. Previous studies have not examined how imams, leaders of mosques, address substance use in their communities. This study aimed to explore imams’ perspectives and approaches toward Muslim Americans with substance use disorders (SUD).

Methods:

Qualitative study of imams in New York City recruited by convenience sampling. We conducted one-on-one semi-structured interviews to address how imams perceive and address substance use. Using an inductive thematic analysis approach, we created an initial coding scheme which was refined iteratively, identified prominent themes, and created an explanatory model to depict relationships between themes.

Results:

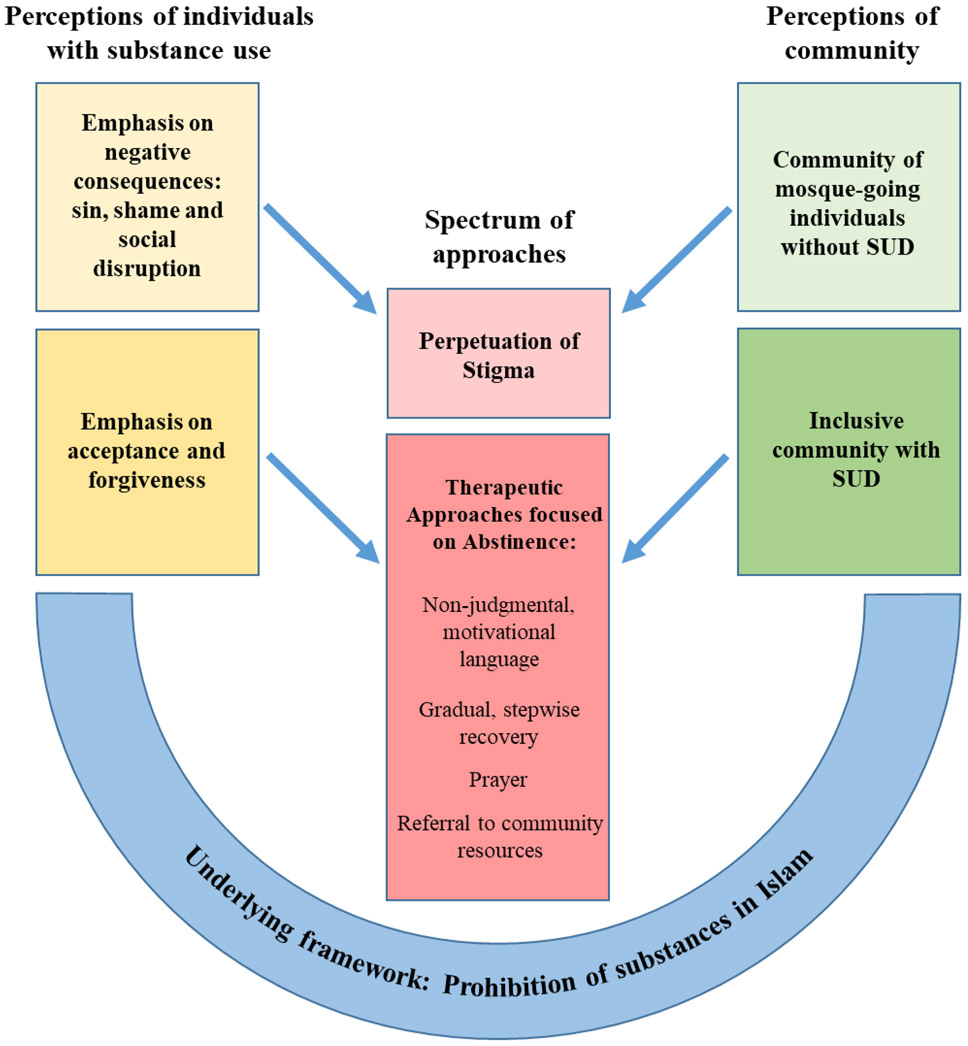

All imams described substance use within a shared underlying framework of religious prohibition of alcohol and other drugs. Their perceptions of individuals with SUD diverged between a focus on sin, shame, and social disruption vs. a focus on acceptance and forgiveness. Furthermore, imams diverged between conceptualizing their communities as comprising mosque-going individuals without SUD vs. broader communities that include individuals with SUD. While imams acknowledged how some imams’ judgmental language toward SUD may perpetuate stigma, they also identified therapeutic approaches toward SUD: non-judgmental engagement, encouragement of recovery, prayer, and referral to resources.

Conclusions:

This study is among the first to illustrate the range of perceptions and approaches to substance use among Muslim American imams. These perceptions have potentially divergent impacts— shaming or assisting individuals with SUD. An understanding of these complexities can inform provision of culturally competent care to Muslim-American patients with SUD.

Keywords: Muslim, imams, alcohol use, substance use, substance use disorder

1. Introduction

Islam is the second largest religion in the world. Since early Islamic civilizations, the consumption of alcohol and other substances has been broadly prohibited, both scripturally and socially (Ali-Northcott, 2013; M. Ali, 2014). Much of the research to date on substance use among Muslim populations focuses on the prevalence of substance use in Muslim-majority countries (Benjamin, 2018; Çelen, 2015; French, Purwono, & Rodkin, 2014; Manickam, Abdul Mutalip, Abdul Hamid, Kamaruddin, & Sabtu, 2014; Matthee, 2014; Mauseth, Skalisky, Clark, & Kaffer, 2016; Yaqub, 2013). While substance use disorder (SUD) may be stigmatized in Muslim-majority countries, research characterizing their provision of SUD treatment is emerging (Bassiony, 2013; Batool et al., 2017; Ghazal, 2019; Ibrahim, Hussain, Alnasser, Almohandes, & Sarhandi, 2018; Khalil et al., 2008; Maehira et al., 2013; Mutlu et al., 2016; Sarasvita, Tonkin, Utomo, & Ali, 2012; Stengel et al., 2018).

Within the United States, Islam is the fastest growing religion, with over three million Muslim Americans (Ghani et al., 2015; Pew Research Center, 2016). Despite religious prohibitions on substance use, and stigma-related challenges to collecting data about SUD (Arfken & Ahmed, 2016), studies have shown that substance use is also prevalent among Muslims living in Muslim-minority countries (Attarabeen et al., 2019; Jamil, 2017; Pannu, Zaman, Bhala, & Zaman, 2009; Williams, Ralphs, & Gray, 2017), and may increase as Muslims acculturate into cultures which are less prohibitive of substance use (Arfken & Grekin, 2015; Mir, 2014). Among Muslim-American undergraduate students, 46% report drinking alcohol and 25% report illicit drug use (Ahmed, Abu-Ras, & Arfken, 2014). In a separate national survey, 14% of Muslim Americans reported binge drinking (Gallup Muslim West Facts Project, 2009).

Christian faith-based interventions are widely utilized in the prevention and treatment of SUD in the USA. Twelve-step programs, which are rooted in the protestant Christian tradition (Mullins, 2010), are used at least some of the time by 72% of US SUD treatment centers (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018). Millati Islami, an organization that has adapted the twelve-step model for Muslims, has been conducting groups to address SUD within Muslim-American communities since 1989 (Millati Islami World Services). Though the organization has been described in a theological analysis (M. Ali, 2014), its outcomes have not been evaluated. Culturally and religiously tailored interventions may be necessary to facilitate effective care for Muslims with SUD (Ali-Northcott, 2013; Arfken, Berry, & Owens, 2009; Senreich & Olusesi, 2016; Tahboub-Schulte, Ali, & Khafaji, 2009). Muslim-American individuals with SUD may seek help in a variety of settings, including their own religious communities (Ali-Northcott, 2013). However, aside from Millati Islami, approaches to substance use and SUD within the Muslim-American community have not been described.

Mosques are centers of worship for Muslims. Imams play a central role in mosques, leading prayer and giving sermons (O. M. Ali, Milstein, & Marzuk, 2005). Imams may also encourage healthy behavior through religious teachings (Islam et al., 2017), advocate for Muslim patients in healthcare settings (Padela, Killawi, Heisler, Demonner, & Fetters, 2011), and provide formal or informal counseling to community members (Abu-Ras, Gheith, & Cournos, 2008; Bagby, Perl, & Froehle, 2001). In a survey of US imams inquiring about the counseling needs of congregants, a majority reported counseling Muslim Americans on anxiety, depression, financial burdens, and discrimination related to Islamophobia. Forty-one percent of imams reported counseling on SUD, though this was not substantively described (O. M. Ali et al., 2005). In another survey of US Muslim worshippers, a minority reported seeking help from an imam specifically because of problems related to drugs or alcohol use (Abu-Ras et al., 2008). While some research has explored how other American faith leaders address substance use within their communities, such as within African American churches (Wong, Derose, Litt, & Miles, 2018), there is scant research on how imams address substance use within Muslim-American communities.

To address these gaps in the literature, we conducted a qualitative study to characterize how imams in New York City perceive and address substance use in their communities. The objectives of this study were to 1) understand the perspectives of imams on how substance use affects their communities and 2) describe imams’ approaches toward Muslim Americans with SUD.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

For this qualitative study, we conducted semi-structured interviews and used an inductive thematic analysis approach. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

2.2. Research team

The study was designed by SM, JS and SN. All interviews were conducted by a female, Muslim physician (SM). Prior to study commencement, members of the research team had no relationship with any of the interviewees.

2.3. Setting and participants

We recruited imams from two sections of New York City, the Bronx and upper Manhattan. Almost 10% of New York City residents are Muslim, representing all racial groups and migrant and non-migrant backgrounds (Muslims for American Progress, 2018). We selected these regions because they have both relatively high populations of Muslim Americans, and a high prevalence of SUD. We focused on imams because of their accessibility and leadership role in the Muslim community. Individuals were eligible to participate if they self-identified as an imam, were fluent in English, and were at least 18 years of age.

2.4. Recruitment

We recruited imams using convenience sampling and snowball sampling. From June 2015 to June 2016, we searched publicly available contact information for all mosques in the selected geographical area and contacted them by phone. All phone numbers without an initial response were contacted at least twice. Given the modest response with this approach, we also introduced the study to two Muslim Americans active in the New York City Muslim community, one an imam in a Manhattan mosque and one a board member of a Manhattan mosque. They were not included as participants in the study but provided contact information for three imams who became research participants for the study. Interviewed imams provided contact information for other imams who were then recruited in a snowball sampling approach.

2.5. Data collection

The interviewer (SM) contacted imams initially by phone and described the project. In this initial conversation, she disclosed her occupation, place of employment, and religious affiliation (Muslim). If the imam was interested in participating, an in-person interview was scheduled at the participant’s mosque. Written informed consent was obtained and a brief questionnaire was verbally administered to ascertain demographic characteristics. A semi-structured interview using an interview guide was conducted and audio recorded. Interviews were professionally transcribed and de-identified. Transcripts were reviewed by the interviewer for errors and to verify de-identification of all personal information.

Because little is known about US imams’ perspectives, an open-ended interview guide was developed. The interview guide was broadly informed by Ali’s exploration of theoretical models of addiction in Islam, including addiction as crime, addiction as spiritual disease and a description of the Millati Islami 12-step approach to SUD recovery (Ali, 2014). Interview guide questions asked imams to describe how they perceived and addressed substance use in their communities. Example questions included: “Think about the last person who came and talked to you about substance use. What was the conversation like?”, “What does Islam say about drugs?,” “What suggestions or help do you offer?,” and “What goals do you emphasize?” To more deeply explore differences in how imams view substance use in individuals vs. communities, after three interviews, the guide was refined to ask imams explicitly how they define their communities and how appropriate it is for mosques to address substance use and substance use disorder in their communities. We use the term substance use disorder throughout this manuscript with the recognition that imams are not making clinical diagnoses, but rather are addressing problems related to substance use.

2.6. Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using an inductive thematic analysis approach (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). Using Dedoose software (version 4.12), an initial coding scheme was created based on open coding of the first three interviews (SM, SN, and JS) to identify topic areas and conceptual themes that arose. The coding scheme was refined iteratively with review of additional interviews by SM, CS, JS and SN, using constant comparison methods to consolidate similar concepts or distinguish dissimilar ones. Two coders (SM and CS) independently coded all transcripts, and all disagreements in coding were reconciled through consensus. Prominent themes were identified, and an explanatory model was created to depict relationships between themes. The explanatory model was refined by reviewing themes and codes iteratively.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

We contacted 46 phone numbers of imams, available either through publically listed contact information for mosques or snowball sampling. Of those, 22 were not reachable and did not have a voicemail option, 12 were left voicemails and did not reply, and two declined to participate. Five participants were recruited via phone call recruitment, and five were recruited via snowball sampling. Ten interviews were completed.

Of the ten participants, all were male, all identified as Sunni, and nine were born outside of the USA. Seven had completed an undergraduate degree and nine had received specialized training in Islamic studies either in the US or abroad. Six of the imams worked in mosques in the Bronx and four worked in mosques in Manhattan. Mosques served communities from different ethnic and racial backgrounds, including congregations that were predominantly African (four), African American (one), South Asian (one), European (one) and mixed congregations (three). All mosques provided a range of services to the community, including Sunday School, Qur’an classes, and formal and informal counseling to individuals. None of the mosques were formally affiliated with a SUD treatment program.

3.2.1. Major themes

We developed an explanatory model to present the major themes that describe how imams perceived and addressed substance use in their communities and to illustrate the relationship between themes (Figure). All imams described a shared underlying framework that substance use is prohibited in Islam. Imams expressed divergent perceptions of individuals with substance use. Specifically, while some imams emphasized negative spiritual, psychological and social consequences for individuals who use substances, other imams embraced a positive outlook toward these individuals, focusing on acceptance and forgiveness. Imams also expressed divergent perceptions of substance use inside their community; some conceptualized their community as limited to mosque-going individuals without SUD while other imams emphasized their obligations to a broader, more inclusive community, which includes individuals with SUD. Imams’ perceptions about individuals with SUD and concepts about community influenced how they address SUD. Some described other imams using judgmental language that can distance individuals with SUD and perpetuate stigma. In contrast, imams also identified therapeutic approaches to help those with SUD, including non-judgmental and motivational language, encouragement of recovery, prayer, and referral to community resources.

FIGURE: Explanatory model for imams’ perceptions of and approaches to substance use.

NOTE: Arrows represent the relationship between themes identified among the sample; individual imams’ perceptions may not align with a single pathway.

3.2.2. Underlying framework

All imams grounded their discussions of substance use within a framework of Islam, making several references to God, the Quran (the holy book for Muslims) and Muhammad (the final Prophet of Islam). Unanimously, they agreed that alcohol is haram, the Arabic term for forbidden or prohibited. Prominently, they explained that alcohol and other drugs are prohibited because they induce intoxication or a mind-altered state. They agreed that substance use is a sin in Islam. For example, one imam said,

‘The [teaching] of the Prophet [is], “every intoxicant is an alcohol and every alcohol is haram.”’

Another said,

“Anything that interferes with your intellect is an illegal substance to Muslims … crack cocaine and K2 and certainly alcohol … Once a person becomes a slave of all these substances then your life is over.”

3.2.3. Divergent perceptions of individuals with substance use: Emphasis on negative consequences vs. acceptance and forgiveness

Some imams emphasized the negative consequences of substance use, including spiritual harms (i.e., sin), psychological harms (i.e., shame) and social harms. In contrast, other imams emphasized acceptance and forgiveness of individuals who use substances.

Regarding spiritual harms, imams discussed how when one uses substances that are haram, they are engaging in sinful acts which prevent the individual from worshipping God and maintaining a connection to God. For example, one imam said:

“[Alcohol] is going to prevent you from worshipping with the prayer. It will prevent you from remembrance of God …”

Imams also discussed how substance use is associated with shame and stigma in the community, causing individuals to hide their bad habits.

“It could be that they do whatever is not good to their bodies … Not only is it [i.e., substance use] not good for them, it is not good for the society. That is why they hide. They hide themselves. They don’t want people to know that they are smoking and they are drinking because they know that is a bad habit. It is forbidden in Islam. It is haram.”

Finally, imams associated substance use with social disruptions such as crime.

“Everybody knows [alcohol is] haram, but people still drink it and themselves, they know it’s affecting them. People drink and drive, get in an accident and kill themselves, kill other people and they go to jail and they mess up their record …”

In contrast, other imams emphasized acceptance and forgiveness of individuals who use substances and focused less on the negative consequences of substance use. They described the importance of being understanding, and they normalized sin in an effort to promote hope for recovery. They discussed how God’s forgiveness is more powerful than human beings’ sins.

“You know, [God] is a load of forgiveness. His first aim is not to punish and he also can give a lot of second chances. We do not see a sinner as a cursed person. You have to love them… As long as they are alive, they have a chance to overcome [substance use] and have a chance for God to forgive them. We make the things easy for them, to tell them that everybody commits sin…”

“We cannot cut the hope of people and say … you are weak … We have to say to them, you are strong, you are good…”

3.2.4. Divergent perceptions of community: mosque-going community without SUD vs. inclusive community with SUD

Some imams perceived their communities to be limited to mosque-going Muslims who they encountered regularly. Imams described these community members as frequently performing good deeds and rarely using substances or facing addiction. They contrasted members of their congregations with people outside the mosque suggesting that the people outside may engage in substance use.

“We don’t have many in our community who do alcohol or drugs.”

“The hard substances… me or my colleagues or imams that I’ve spoken to haven’t come across it in such a way that we could say it’s an actual problem within the community.”

“The drugs, alcohol, there are not much in Islam. They always stay outside when they do these things.”

In contrast, other imams had a much broader definition of community, which included mosque-going Muslims and non mosque-going Muslims who may have SUD. Imams identified an obligation toward serving all people who seek help, including those who use substances.

“… [substance use] is an undercover problem in the Muslim community … people know it but nobody wants to acknowledge it …”

“There are no boundaries [of the community]. Anybody who needs help at any time, in any shape or form and I can be of assistance. That is my duty … I am willing to speak to anybody…”

“And we love them [those who use substances]. We let them know that they are not out, they are in. [We] are inclusive.”

“We say no, even though you do something which is not good, we need you in our community…”

3.2.4. Perpetuation of stigma vs. therapeutic approaches focused on abstinence

Imams varied in how they addressed substance use within the community. Imams described how leaders of mosques who use judgmental or harsh language distance themselves from community members who use substances, preventing the problem from being addressed and perpetuating stigma.

“Some of them [imams] tell the people, “stop it or you will find yourself in the hell fire.” [In contrast, God] says when approaching people, treat them with respect and dignity for them to listen to you.”

“Unfortunately, [in] a lot of religious places, the judgment is too heavy and people are so prejudiced against what they don’t like -- to a point where there can never, ever be a relationship built because people would be afraid to talk to you about their shortcomings.”

Other imams advocated for open, non-judgmental communication and encouragement in a welcoming environment to support individuals dealing with problems related to substance use. All emphasized abstinence as an end goal.

“The first thing is, let’s talk. No judgment, let’s talk … Because once people begin to talk to you, you talk to them … you drink tea … I don’t care what you do or who you are or whatever, I don’t even want to know. Let’s just talk …”

“It’s not easy to leave it [substance use]. It’s a big fight with yourself … Sometimes you may find yourself defeated, so that’s an example of the weakness but that doesn’t mean that actually a human being will always be weak. Of course if he stands back, with the help of God, you can stop.”

Imams used religious teachings in their conversations about substance use, specifically describing a stepwise approach to recovery. Religious teachings regarding alcohol became more restrictive over a period of time in the early Islamic period. Early on, alcohol was prohibited for certain occasions like prayer but allowed in other circumstances; later on, it became prohibited in all situations. This imam makes an analogy between the gradual, stepwise prohibition of alcohol over time and the gradual stepwise recovery from using substances, with abstinence as the end goal.

“We have verses from the Quran talking about alcohol, addressing it from the beginning to the end, how the Quran treated the people stage by stage. You know, because when you are involved in something [like substance use], it’s very hard to take you out of it at one time. So the Quran [addressed people who use substances] stage by stage until the end stage, [when you] finish and [you] never, ever go back to it.”

Other imams discussed prayer as a therapeutic approach.

“Praying and being close to him. Talk to him directly… When you prostrate your forehead down, that is the place that you will be [most] close to God. You are praying and he knows what you want to ask him before you even ask him. So you try to sit and show … that you need [God] completely…”

Finally, other imams made referrals to community resources.

“… what we do is we developed a directory of service providers, whether it is … because of substance abuse [an individual] completely lost their home, lost their family, lost everything and wants to reconnect with that… we have referrals.

“If they came to us and if they were wanting to change their life from negatively to positively, what can we do? We refer them … to the hospital and then the hospital pushes them and encourages them to go to this rehabilitation [center].”

4. Discussion

This study is among the first to illuminate how imams perceive and address substance use within Muslim-American communities. Within a shared framework that assumes prohibition of substance use, imams diverged in their perspectives on individuals with SUD, whether they are part of the Muslim community, and approaches to address substance use. Taken together, these findings highlight a range of perspectives and approaches to substance use among Muslim American imams: while they could result in shaming and ostracizing individuals with SUD, they could also result in welcoming and assisting these individuals. There may be unseized opportunities to develop collaborations with imams to help support people with SUD by reducing stigma and facilitating treatment engagement.

Some imams in this study emphasized that because substance use is prohibited and considered a sin, there are negative consequences for individuals with SUD both in their spiritual life and socially within their Muslim communities. The spiritual and social impact of substance use among Muslims was similarly reported in a qualitative study of British South Asian young men and women (Bradby, 2007). In that study, participants reported that drinking alcohol could lead to rejection by God, an inability to access spiritual rewards in the afterlife and, because drinking alcohol is considered shameful, ostracism from the Muslim community. The expectation of substance use leading to both spiritual and community consequences aligns with a theory posited by a contemporary Muslim theologian (M. Ali, 2014). He describes traditional Muslim societies as “shame-based” cultures, in which fear of both God’s and community members’ knowledge of wrongdoing prevents an individual from transgressing. He argues that in Muslim cultures an individual with SUD represents a failure of the entire community. This serves as an explanation for imams, as community leaders, reiterating social narratives of the negative consequences of substance use.

Those imams with negative perceptions of individuals with SUD, who emphasized sin and shame and who perceived the community as unwelcoming to those who use substances, may perpetuate stigma against Muslims with SUD. Similar to processes described among Jewish-Americans (Loewenthal, 2014) and West African-American immigrants (Senreich & Olusesi, 2016), some imams in this study identified substance use as a problem which lies outside their community. The stigma surrounding substance use among Muslim populations has been described (Ali-Northcott, 2013; Arfken & Ahmed, 2016; Arfken & Grekin, 2015; Badr, Taha, & Dee, 2014). Moreover, the detrimental effects of stigma on the psychological well-being of individuals with SUD are well described (Kulesza, Watkins, Ober, Osilla, & Ewing, 2017). Creating an environment which perpetuates stigma may lead to missed opportunities for mosques and other Muslim faith-based organizations from acknowledging, recognizing, and addressing SUD.

In contrast, other imams in this study focused on de-stigmatizing SUD by encouraging forgiveness and open communication; this approach may help to reduce stigma and facilitate treatment engagement. In a Christian context, measures of forgiveness, including forgiveness of self, forgiveness of others, and perceived forgiveness by God have been shown to predict decreased patterns of alcohol use among individuals entering SUD treatment (Webb, Robinson, Brower, & Zucker, 2006). In a qualitative study at a Canadian Muslim community services agency that provided SUD outreach and counseling, case workers reported that their work helped to reduce community stigma around SUD (Jozaghi, Asadullah, & Dahya, 2016). Similarly, in a qualitative study of Muslim faith healers in the UK, respondents described empathy for people with SUD, invoked religious teachings of Islam to assist those with SUD in their recovery, and advocated for referrals to community resources and drug counselors (Rashid et al., 2014). Health campaigns building on Islamic religious norms and disseminated through imams and mosques have potential to promote health behavior (Islam & Patel, 2018; Islam et al., 2017; Killawi, Heisler, Hamid, & Padela, 2015). One example is a pilot program in Malaysia, in which a methadone maintenance program was implemented in a mosque, and local imams delivered religious counseling services. Imams brought forward motivational verses from the Quran, taught individuals how to use their faith to maintain their sobriety and discussed the importance of religious community in overcoming addiction (Rashid et al., 2014). Taken together, these findings suggest that open attitudes among imams and faith-based organizations may facilitate treatment of SUD.

Our findings are consistent with other studies which highlight the complexities of addressing substance use within religious communities: while people with SUD may experience stigmatization within religious communities, these communities may also provide support for those who value religion and spirituality as part of their treatment for SUD. In a survey of 169 African American churches, 71% reported caring for persons with SUD often, but half reported that individuals’ shame related to SUD served as a barrier to treatment referral (Wong et al., 2018). Similarly, stigmatization within the Jewish community may prevent help-seeking, yet Jews may also feel more comfortable in seeking treatment in programs sensitive to their religious and cultural values (Loewenthal, 2014). Finally, in a study population demographically similar to congregants served by imams in our study, Muslim and Christian West African immigrants report stigmatization of SUD yet still identify spirituality as an essential resource (Senreich & Olusesi, 2016).

Our findings highlight an opportunity for primary care and SUD treatment providers. Patients report wanting to engage in conversations about spirituality and health with their providers (Best, Butow, & Olver, 2015). Our findings highlight reasons for providers caring for patients with SUD to engage in conversations about religion and spirituality. Understanding the complexity of perceptions of SUD among faith leaders in mosques and other religious settings allows clinicians to provide religiously and culturally competent care. For example, if a Muslim patient with SUD relays concerns related to stigma and marginalization from the Muslim community, the provider may attempt to address these concerns by offering psychosocial support and additional mental health services as needed. Conversely, if the patient expresses support from the Muslim community or wishes to seek assistance there, the provider might partner with a faith-based provider to optimize a treatment plan for the patient.

There are several limitations to this study. We are unable to quantify the impact of having a Muslim woman physician conducting study recruitment and interviews on enrollment and participant responses. The sample size was small, but did allow for exploratory analyses of salient themes. In our sample, imams belonged to mosques with congregants from fairly diverse backgrounds, but the ethnicities represented were not proportionately reflective of the US Muslim population, which includes large populations of Arab Americans, South Asian Americans and African Americans (Gallup Muslim West Facts Project, 2009). This sampling limitation, coupled with the modest sample size, precludes analysis of the impact of factors that may impact imam’s approaches to SUD; these include imams’ and congregants’ gender, race, ethnicity, country of origin, number of years spent in the USA, and sect within Islam (e.g., Sunni vs. Shi’a); imams’ formal chaplaincy education; and prevalence of SUD within imams’ communities. In addition, the results of the study may have been impacted by social desirability bias. The past two decades have seen the Muslim-American identity change dramatically, with the Muslim community regularly facing discrimination and stigma (Samari, 2016). Imams in this study may have wanted to reinforce how individuals in their communities are respectful, law-abiding citizens who do not engage in activities (like substance use) which may be associated with social disruption and legal problems.

Our findings highlight several opportunities for future study. First, what strategies can be used to best leverage spiritual supports to facilitate engagement, support and treatment of SUD? How can interventions be designed to minimize SUD-related stigma, within a Muslim-American context, and more broadly? How can clinicians best collaborate with spiritual leaders to facilitate access to and engagement in treatment of SUD?

5. Conclusion

This study is among the first to illustrate the range of perceptions and approaches to substance use among Muslim American imams. An understanding of the complex, divergent responses to SUD within the Muslim-American community can inform provision of culturally competent and comprehensive care to Muslim American patients with SUD.

Highlights.

Imams have divergent perceptions of and approaches to substance use disorder (SUD).

Some imams focused on negative consequences; others focused on acceptance.

Approaches to SUD ranged from stigmatization to provision of therapeutic resources.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01 DA039046 and K24 DA046309 (JS); and R01 DA042813 (SN)]; and the Department of Family and Social Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center. Dr. Starrels receives consulting fees from Venebio Group, LLC; research and travel support from the Opioid Post-Marketing Requirement Consortium (for work on an FDA-required observational study of the risks of opioids); and royalties from Wolters Kluwer Health (to author a review on UpToDate.com). Dr. Nahvi receives investigator-initiated research support from Pfizer.

REFERENCES

- Abu-Ras W, Gheith A, & Cournos F (2008). The imam's role in mental health promotion: A study at 22 mosques in New York City's Muslim community. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 3(2), 155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Abu-Ras W, & Arfken CL (2014). Prevalence of risk behaviors among US Muslim college students. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 8(1). [Google Scholar]

- Ali-Northcott L (2013). Substance Abuse In Ahmed S & Amer MM (Eds.), Counseling Muslims: Handbook of Mental Health Issues and Interventions: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ali M (2014). Perspectives on Drug Addiction in Islamic History and Theology. Religions, 5(3), 912–928. doi: 10.3390/rel5030912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali OM, Milstein G, & Marzuk PM (2005). The Imam's Role in Meeting the Counseling Needs of Muslim Communities in the United States. Psychiatric Services, 56(2), 202–205. Retrieved from http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arfken CL, & Ahmed S (2016). Ten years of substance use research in Muslim populations: Where do we go from here? Definition and extent of problem globally. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 4908, 13–24. doi: 10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0010.103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arfken CL, Berry A, & Owens D (2009). Pathways for Arab Americans to substance abuse treatment in southeastern Michigan. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 4(1), 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Arfken CL, & Grekin ER (2015). Alcohol and drug use: Prevalence, predictors, and interventions In Awad MMA & G H (Eds.), Handbook of Arab American psychology (pp. 233–244): Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Attarabeen O, Alkhateeb F, Larkin K, Sambamoorthi U, Newton M, & Kelly K (2019). Tobacco Use among Adult Muslims in the United States. Substance Use and Misuse, 54(8), 1385–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr LK, Taha A, & Dee V (2014). Substance Abuse in Middle Eastern Adolescents Living in Two Different Countries: Spiritual, Cultural, Family and Personal Factors. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(4), 1060–1074. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9694-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby IA-W, Perl PM, & Froehle B (2001). The mosque in America, a national portrait: A report from the mosque study project Council on American-Islamic Relations; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Bassiony M (2013). Substance use disorders in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Substance use, 18(6), 450–466. [Google Scholar]

- Batool S, Manzoor I, Hassnain S, Bajwa A, Abbas M, Mahmood M, & Sohail H (2017). Pattern of addiction and its relapse among habitual drug abusers in Lahore, Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J, 23(3), 168–172. doi: 10.26719/2017.23.3.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin M (2018). Inside Iran The Real History and Politics of the Islamic Republic of Iran. OR Books. [Google Scholar]

- Best M, Butow P, & Olver I (2015). Do patients want doctors to talk about spirituality? A systematic literature review. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(11), 1320–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradby H (2007). Watch out for the Aunties! Young British Asians’ accounts of identity and substance use. Sociology of Health and Illness, 29(5), 656–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çelen A (2015). Influence of holy month Ramadan on alcohol consumption in Turkey. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(6), 2122–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French DC, Purwono U, & Rodkin P (2014). Indonesian Muslim Adolescents' Use of Tobacco and Alcohol: Associations With Use by Friends and Network Affiliates. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly (1982-), 60(4), 385–402. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup Muslim West Facts Project. (2009). Muslim Americans: A national portrait—an in-depth analysis of America’s most diverse religious community. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Ghani MA, Brown S-E, Khan F, Wickersham JA, Lim SH, Dhaliwal SK, … Altice FL (2015). An exploratory qualitative assessment of self-reported treatment outcomes and satisfaction among patients accessing an innovative voluntary drug treatment centre in Malaysia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26(2), 175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazal P (2019). Rising trend of substance abuse in Pakistan: a study of sociodemographic profiles of patients admitted to rehabilitation centres. Public Health, 167, 34–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim Y, Hussain SM, Alnasser S, Almohandes H, & Sarhandi I (2018). Patterns and sociodemographic characteristics of substance abuse in Al Qassim, Saudi Arabia: a retrospective study at a psychiatric rehabilitation center. Annals of Saudi Medicine, 38(5), 319–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam N, & Patel S (2018). Best practices for partnering with ethnic minority-serving religious organizations on health promotion and prevention. AMA journal of ethics, 20(7), E643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam N, Patel S, Brooks-Griffin Q, Kemp P, Raveis V, Riley L, … Cole H (2017). Understanding barriers and facilitators to breast and cervical cancer screening among Muslim women in New York City: perspectives from key informants. SM journal of community medicine, 3(1). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil HJ (2017). Mental disorders and substance use among Iraqis (Chaldean and Arab-Muslim) in Michigan, USA. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 11(1). [Google Scholar]

- Jozaghi E, Asadullah M, & Dahya A (2016). The role of Muslim faith-based programs in transforming the lives of people suffering with mental health and addiction problems. Journal of Substance use, 21(6), 587–593. Retrieved from 10.3109/14659891.2015.1112851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil A, Okasha T, Shawky M, Haroon A, Elhabiby M, Carise D, … Rawson RA (2008). Characterization of Substance Abuse Patients Presenting for Treatment at a University Psychiatric Hospital in Cairo, Egypt. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment, 7(4), 199–209. doi: 10.1097/adt.0b013e318158856d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killawi A, Heisler M, Hamid H, & Padela AI (2015). Using CBPR for Health Research in American Muslim Mosque Communities. 9(1), 65–74. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2015.0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesza M, Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Osilla KC, & Ewing B (2017). Internalized stigma as an independent risk factor for substance use problems among primary care patients: Rationale and preliminary support. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 180, 52–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenthal KM (2014). Addiction: alcohol and substance abuse in Judaism. Religions, 5(4), 972–984. [Google Scholar]

- Maehira Y, Chowdhury EI, Reza M, Drahozal R, Gayen TK, Masud I, … Azim T (2013). Factors associated with relapse into drug use among male and female attendees of a three-month drug detoxification–rehabilitation programme in Dhaka, Bangladesh: a prospective cohort study. Harm reduction journal, 10(1), 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manickam MA, Abdul Mutalip MH, Abdul Hamid HA, Kamaruddin RB, & Sabtu MY (2014). Prevalence, comorbidities, and cofactors associated with alcohol consumption among school-going adolescents in Malaysia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 26(5 Suppl), 91s–99s. doi: 10.1177/1010539514542194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthee R (2014). The Ambiguities of Alcohol in Iranian History: Between Excess and Abstention In Wine Culture in Iran and Beyond: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mauseth KB, Skalisky J, Clark NE, & Kaffer R (2016). Substance Use in Muslim Culture: Social and Generational Changes in Acceptance and Practice in Jordan. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(4), 1312–1325. doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0064-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB, & Tisdell EJ (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Millati Islami World Services. What is Millati Islami? Retrieved from http://www.millatiislami.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Mir S (2014). I Didn’t Want to Have That Outcast Belief about Alcohol Walking the Tightrope of Alcohol in Campus Culture In Muslim American Women on Campus (pp. 47–86): University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins JW (2010). Spirituality and the twelve steps. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, n/a-n/a. doi: 10.1002/aps.242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muslims for American Progress. (2018). An impact report of Muslim contributions to New York City. Retrieved from https://www.ispu.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/MAP-NYC-Report-Web-3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu E, Alaei A, Tracy M, Waye K, Cetin MK, & Alaei K (2016). Correlates of injection drug use among individuals admitted to public and private drug treatment facilities in Turkey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 164, 71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padela AI, Killawi A, Heisler M, Demonner S, & Fetters MD (2011). The Role of Imams in American Muslim Health: Perspectives of Muslim Community Leaders in Southeast Michigan. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(2), 359–373. Retrieved from 10.1007/s10943-010-9428-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannu G, Zaman S, Bhala N, & Zaman R (2009). Alcohol use in South Asians in the UK. In: British Medical Journal Publishing Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2016). A new estimate of the US Muslim population. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/01/06/a-new-estimate-of-the-u-s-muslim-population/ [Google Scholar]

- Rashid RA, Kamali K, Habil MH, Shaharom MH, Seghatoleslam T, & Looyeh MY (2014). A mosque-based methadone maintenance treatment strategy: Implementation and pilot results. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25(6), 1071–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samari G (2016). Islamophobia and Public Health in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 106(11), 1920–1925. Retrieved from http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarasvita R, Tonkin A, Utomo B, & Ali R (2012). Predictive factors for treatment retention in methadone programs in Indonesia. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 42(3), 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senreich E, & Olusesi OA (2016). Attitudes of West African Immigrants in the United States toward Substance Misuse: Exploring Culturally Informed Prevention and Treatment Strategies. Social work in public health, 31(3), 153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stengel CM, Mane F, Guise A, Pouye M, Sigrist M, & Rhodes T (2018). “They accept me, because I was one of them”: formative qualitative research supporting the feasibility of peer-led outreach for people who use drugs in Dakar, Senegal. Harm reduction journal, 15(1), 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). National survey of substance abuse treatment centers (N-SSTS): 2018. Retrieved from. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSSATS-2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Tahboub-Schulte S, Ali AY, & Khafaji T (2009). Treating substance dependency in the UAE: A case study. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 4(1), 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Webb JR, Robinson EA, Brower KJ, & Zucker RA (2006). Forgiveness and alcohol problems among people entering substance abuse treatment. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 25(3), 55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L, Ralphs R, & Gray P (2017). The Normalization of Cannabis Use Among Bangladeshi and Pakistani Youth: A New Frontier for the Normalization Thesis? Substance Use and Misuse, 52(4), 413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EC, Derose KP, Litt P, & Miles JNV (2018). Sources of Care for Alcohol and Other Drug Problems: The Role of the African American Church. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(4), 1200–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaqub F (2013). Pakistan's drug problem. The Lancet, 381(9884), 2153–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]