Abstract

Background

The impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on well-being has the potential for serious negative consequences on work, home life, and patient care. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Resilience Task Force collaboration set out to investigate well-being in oncology over time since COVID-19.

Methods

Two online anonymous surveys were conducted (survey I: April/May 2020; survey II: July/August 2020). Statistical analyses were performed to examine group differences, associations, and predictors of key outcomes: (i) well-being/distress [expanded Well-being Index (eWBI; 9 items)]; (ii) burnout (1 item from eWBI); (iii) job performance since COVID-19 (JP-CV; 2 items).

Results

Responses from survey I (1520 participants from 101 countries) indicate that COVID-19 is impacting oncology professionals; in particular, 25% of participants indicated being at risk of distress (poor well-being, eWBI ≥ 4), 38% reported feeling burnout, and 66% reported not being able to perform their job compared with the pre-COVID-19 period. Higher JP-CV was associated with better well-being and not feeling burnout (P < 0.01). Differences were seen in well-being and JP-CV between countries (P < 0.001) and were related to country COVID-19 crude mortality rate (P < 0.05). Consistent predictors of well-being, burnout, and JP-CV were psychological resilience and changes to work hours. In survey II, among 272 participants who completed both surveys, while JP-CV improved (38% versus 54%, P < 0.001), eWBI scores ≥4 and burnout rates were significantly higher compared with survey I (22% versus 31%, P = 0.01; and 35% versus 49%, P = 0.001, respectively), suggesting well-being and burnout have worsened over a 3-month period during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

In the first and largest global survey series, COVID-19 is impacting well-being and job performance of oncology professionals. JP-CV has improved but risk of distress and burnout has increased over time. Urgent measures to address well-being and improve resilience are essential.

Key words: well-being, burnout, job performance, oncology professionals, resilience, COVID-19

Highlights

-

•

This is the first global report of well-being in oncology professionals since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

-

•

In this survey of 1520 oncology professionals, 67% reported a change in professional duties since COVID-19.

-

•

About 25% had risk of distress (poor well-being), 38% felt burnout, and 66% were not able to perform their job compared with the pre-COVID-19 period.

-

•

Well-being and job performance since COVID-19 (JP-CV) were correlated with COVID-19 crude mortality rate in the country of practice.

-

•

The main predictors of well-being, burnout, and JP-CV were resilience and changes to work hours.

-

•

JP-CV has improved but risk of distress and burnout has increased over time.

Introduction

The well-being of oncology health care professionals is fundamental in ensuring that the best care is provided for cancer patients.1 The component of physician well-being most comprehensively studied is burnout.1 The prevalence of burnout in oncologists is already known to be significant,1,2 and with the current unprecedented impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on health care systems globally, the well-being of oncologists is likely to be affected. However, the true long-term nature and extent of this are unknown.

In the early phase of COVID-19, oncology physicians in the United States and Singapore reported high levels of anxiety.3,4 In fact, the distress caused by COVID-19 is also experienced by physicians and surgeons across various specialties globally.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Increased burnout has been reported in frontline health care professionals surveyed globally through social media.11 In the study from Wuhan, China, oncology physicians and nurses dispatched to work as frontline health care workers in a dedicated COVID-19 ward paradoxically had lower rates of burnout compared with colleagues who continued to work in their usual surroundings.12 The authors hypothesised that direct involvement in combating COVID-19 may have provided frontline health care workers with a greater sense of control and hence reduced burnout.12 These findings highlight the complexity and diversity of the impact of COVID-19 on well-being across different global regions and specialties.

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) established the ESMO Resilience Taskforce in December 2019 with a mandate to support well-being of oncology professionals after a high prevalence of burnout in young (≤40 years old) oncologists was previously identified.2 Occupational factors integral to cancer care placing oncology professionals at risk of burnout include delivering bad news, discussing and supervising complex treatment decisions with risk of toxicities and often without substantial prolongation of survival, pressures to keep at the forefront of scientific advances, and deliver research at a time where resources are challenged.2 Substance abuse,11 depression, suicide,13,14 medical errors,12 professional misconduct,15 and leaving oncology and early retirement14,16 have all been linked with burnout or poor well-being. These potential consequences could have a serious negative impact on patient care.2

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the ESMO Resilience Task Force launched a series of global surveys to evaluate the impact of challenges posed by COVID-19 on daily practice, well-being, current levels of support, and coping strategies of oncologists and other oncology professionals globally in order to develop support strategies. The longitudinal nature of these surveys is designed to identify relevant issues as the pandemic evolves as well as the longer-term impact on oncology professionals across countries.

Here, we report the findings of our first survey (survey I) in this global series launched in April/May 2020, and also the initial results of a subgroup of participants who completed survey II conducted in July/August 2020.

Methods

Survey design

The ESMO Resilience Task Force, in collaboration with ESMO Young Oncologists Committee, ESMO Women for Oncology Committee, ESMO Leaders Generation Programme Alumni members, and the OncoAlert Network, designed a series of online global surveys launched at different timepoints during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. The project was approved by the ESMO Executive Board. The surveys, hosted on the Qualtrics platform, were available on the ESMO website, ESMO membership emails, and were promoted through social media. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Participants who consented to longitudinal evaluation of their responses at different timepoints were assigned a trackable unique identifier code. Survey I was available online from 16 April to 3 May 2020, and survey II was launched 3 months following survey I (16 July to 5 August).

Survey measures

Sociodemographic, background variables, and three key outcomes of interest [well-being, burnout, and job performance since COVID-19 (JP-CV)] were collected in the surveys (Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058). In addition, psychological resilience, coping strategies, COVID-19-related job changes, perceptions of value and support, working environment, and changes to lifestyle were measured (including Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058).

Resilience to changes at work was measured using a single-item bipolar measure using a 9-point scale (low to high resilience) C Hardy (unpublished data). Well-being was measured using the validated expanded well-being Index (eWBI) screening tool consisting of nine items.15,16,17 Score of ≥4 has been shown to be associated with distress, fatigue, burnout, and low quality of life in clinician populations.15 A single item from eWBI,16 ‘Have you felt burned out from your work?’ (‘yes’ or ‘no’), was used in this report as a surrogate question and preliminary screen of the current level of burnout among participants. JP-CV was measured by the mean score of two 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree; scores 1 to 5) questions: ‘Compared to pre-COVID-19 outbreak, I am still able to do my job to the same standard’ and ‘I currently feel able to deliver the same standard of care to my patients as before the COVID-19 outbreak’. JP-CV score of ≥3.5 was considered favourable JP-CV.

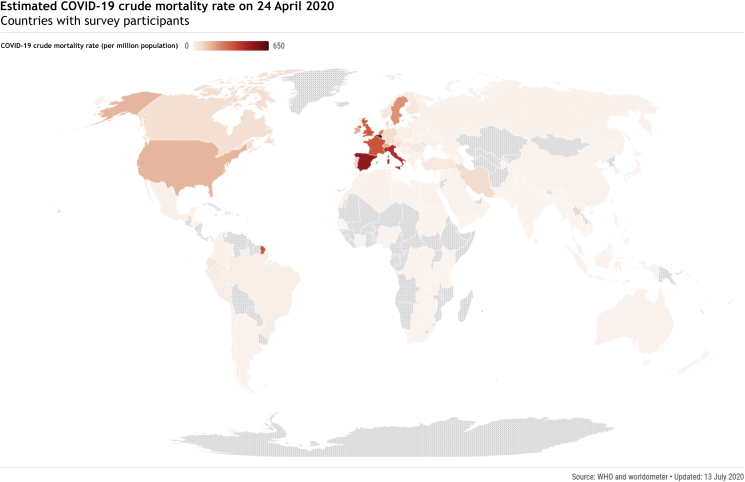

Estimated crude mortality rate was calculated as a marker of the relative severity of COVID-19 outbreak in each country. This was calculated based on total number of COVID-19-related deaths per million population in each respective country using publicly available data provided by the World Health Organisation (WHO)18 and worldometer19 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Estimated crude mortality rate18, 19 due to COVID-19 in countries where participants are working in (n = 1520 from 101 countries) during the survey period (16 April to 3 May 2020).

COVID-19, coronavirus disease.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were presented as median (interquartile range) or mean ± standard deviation, and proportions were expressed as a percentage. Chi-square analysis was used to compare categorical variables and paired or unpaired t-test were used to analyse continuous variables. P values were two tailed. Bivariate correlations were used to examine association between crude mortality rate and outcome measures. Linear regression analyses were used to assess predictors of well-being and JP-CV, and binary logistic regression analyses were used to identify factors associated with burnout. Hierarchical regression analyses were used to control for mortality rate where appropriate. Otherwise univariate regression was conducted followed by multiple regression to identify predictive factors on the outcomes of interest. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0/26.0 (IBM, New York, NY, USA) and data represented using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics of participants

A total of 1520 participants from 101 countries, of which 1020 (67%) were from Europe, completed survey I in April/May 2020 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058). Overall, there were 777 (51%) female participants, 833 (55%) participants over the age of 40 years, and a majority (n = 1070, 70%) were of white ethnicity. A total of 245 participants (16%) disclosed an increased personal risk due to underlying comorbidities or condition (Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058). The most common primary place of work was general hospital (n = 723, 48%) followed by cancer centre exclusively treating cancer patients (n = 619, 41%). Almost all participants were clinicians, with medical oncologists most represented (n = 1059, 70%). Trainees contributed to 22% (n = 333) of responses, with majority having been in training for ≥2 years (n = 262, 79%). More than half of nontrainees (n = 688/1187, 58%) had >10 years of oncology experience. Majority of participants (n = 1365, 90%) were ESMO members.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (n = 1520)

| Number, n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| ≤40 | 687 (45) |

| >40 | 833 (55) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 777 (51) |

| Male | 742 (49) |

| Non-binary | 1 (0.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 1070 (70) |

| Asian | 277 (18) |

| Arab | 52 (3) |

| Mixed | 45 (3) |

| Black | 20 (1) |

| Other | 35 (2) |

| Prefer not to say | 21 (1) |

| Region of work | |

| Europea | 1020 (67) |

| Southwestern Europe | 271 (18) |

| Central Europe | 248 (16) |

| Northern Europe and British Isles | 247 (16) |

| Western Europe | 109 (7) |

| Southeastern Europe | 103 (7) |

| Eastern Europe | 42 (3) |

| Asia | 261 (17) |

| North America | 79 (5) |

| South America | 69 (5) |

| Africa | 57 (4) |

| Oceania | 33 (2) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.1) |

| Primary place of work | |

| General hospital | 723 (48) |

| Cancer centre | 619 (41) |

| Private outpatient clinic | 65 (4) |

| Pharmaceutical/technology company | 36 (2) |

| Health care organisation | 18 (1) |

| Other | 59 (4) |

| Specialtyb | |

| Medical oncology | 1059 (70) |

| Clinical oncology | 271 (18) |

| Haemato-oncology | 123 (8) |

| Radiation oncology | 88 (6) |

| Palliative care | 86 (6) |

| Laboratory-based researcher/scientist | 53 (4) |

| Surgical oncology | 43 (3) |

| Nursing | 18 (1) |

| Other | 120 (8) |

| Trainee | |

| Yes | 333 (22) |

| No | 1187 (78) |

| Duration of training completed (years), n = 333 | |

| <2 | 71 (21) |

| 2-5 | 185 (56) |

| >5 | 77 (23) |

| Post-training oncology experience (years), n = 1187 | |

| <5 | 249 (21) |

| 5-10 | 240 (20) |

| >10 | 688 (58) |

| Not applicable | 10 (1) |

| ESMO member | |

| Yes | 1365 (90) |

| No | 155 (10) |

Southwestern Europe: Italy, Portugal, Spain; Central Europe: Austria, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Switzerland; Northern Europe and the British Isles: Denmark, Finland, Norway, Republic of Ireland, Sweden, United Kingdom; Western Europe: Belgium, France, Luxembourg, The Netherlands; Southeastern Europe: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Israel, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey; and Eastern Europe: Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Russian Federation, Ukraine.

Some participants have selected two or more specialties within their job role, and proportion of representation is summarised as such.

Changes in professional duties and job performance since COVID-19

More than two-thirds (n = 1024, 67%) of participants reported a change in their professional duties since the COVID-19 outbreak (Table 2). Almost half of respondents (n = 744, 49%) were performing remote consultations, and a third (n = 499, 33%) reported more hours working from home. Of note, 14% (n = 206) were involved in COVID-19 inpatient work and 16% (n = 237) in COVID-19-related research. There were a significant number of participants who reported reduced clinical trial activity (n = 573, 38%) and other research activity in general (n = 443, 29%). Few (n = 87, 6%) were fully redeployed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2.

Change in professional duties since the COVID-19 outbreak (n = 1520)

| Number, n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Change in professional duties | |

| Yes | 1024 (67) |

| No | 496 (33) |

| Nature of change in professional duties | |

| Scope of clinical work | |

| More remote (video/telephone) consultations | 744 (49) |

| Increased direct patient care | 103 (7) |

| Less inpatient work | 388 (26) |

| More inpatient work | 148 (10) |

| COVID-19 inpatient work | 206 (14) |

| Cover other oncology non-COVID-19 patients | 187 (12) |

| Cover non-oncology specialties | 168 (11) |

| Working hours and shift patterns | |

| More hours working from home | 499 (33) |

| Reduced number of hours of work | 373 (25) |

| Increased number of hours of work | 254 (17) |

| More out-of-hours work in hospital | 242 (16) |

| More weekend shifts | 175 (12) |

| More overnight shifts | 122 (8) |

| Clinical trial and research | |

| Reduced clinical trial activity | 573 (38) |

| Reduced research (nonclinical trials) activity | 443 (29) |

| COVID-19-related research | 237 (16) |

| Redeployed | |

| Yes | 87 (6) |

| Partially | 275 (18) |

| No | 1158 (76) |

| Redeployment relevant to prior training, n = 362 | |

| Yes | 154 (43) |

| No | 208 (57) |

| Adequate training for redeployment, n = 208 | |

| Yes | 114 (55) |

| No | 94 (45) |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

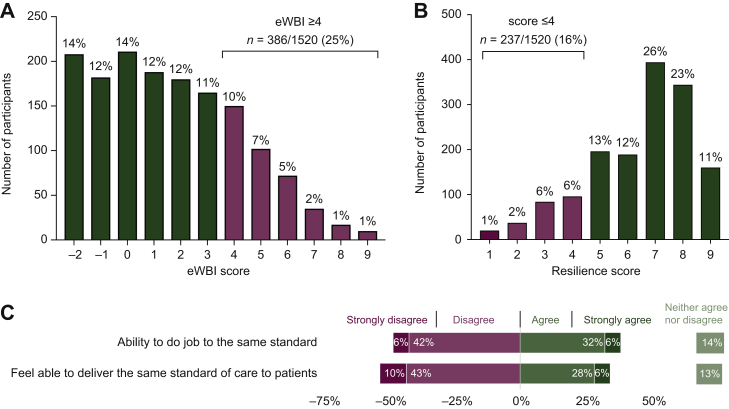

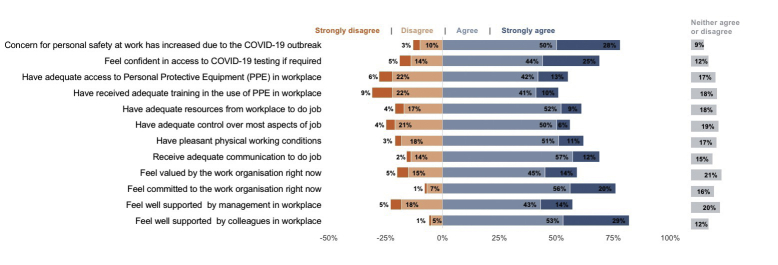

In general, 49% (n = 739) of participants reported that they were unable to do their job to the same standard compared with the pre-COVID-19 period and 53% (n = 804) did not feel able to deliver the same standard of patient care (Figure 2C). Taken altogether, 66% (n = 997) reported a mean JP-CV score of <3.5. Of note, 78% (n = 1190) reported that their concerns for personal safety at work have increased due to COVID-19 (Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058). At the time of the survey, 19% (n = 283) did not feel confident in being able to access COVID-19 testing if required, and 28% (n = 418) did not have adequate access to personal protective equipment at their workplace (Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058). Importantly, 62% (n = 945) did have pleasant physical working conditions, 56% (n = 857) had adequate control over most aspects of their job, and more than two-thirds (69%, n = 1041) received adequate communication to do their job (Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058).

Figure 2.

Key outcomes of interest reported in survey I (April/May 2020). (A) Self-reported well-being, (B) resilience, and (C) job performance since COVID-19 (JP-CV) during the COVID-19 crisis (n = 1520).

COVID-19, coronavirus disease; eWBI, expanded Well-being Index.

Well-being and burnout

On the whole, there were 386 participants (25%) with a self-reported cumulative eWBI score of ≥4 (Figure 2A). The proportion of participants at risk of distress, with eWBI score of ≥4, was significantly higher among female (29% versus 22%, P = 0.0017) and young oncology professionals (aged ≤40 years; 33% versus 19%, P < 0.001). A total of 572 participants (38%) specifically answered ‘yes’ to the burnout question, and this was also higher among female (42% versus 34%, P = 0.001) and young oncology professionals (43% versus 32%, P < 0.001).

Outcome measures were analysed to determine the associations between them using standard Pearson (r) and point biserial (rpb) correlations. Higher JP-CV score was significantly associated with better well-being [r(1519) = −0·211, P < 0.01] and not feeling burnout [rpb(1519) = −0.148, P = 0.01]. Feeling burnout was significantly associated with poorer well-being [rpb(1519) = 0.672, P = 0.01].

Well-being support and coping strategies

At the time of survey I, well-being support services were accessible to 777 (51%) participants. Of these, 447 (58%) participants used a combination of approaches; most popular were online or smartphone apps, psychological support from work, and telephone support (Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058). In addition, a variety of coping strategies were used by participants including thinking of positives (n = 740, 49%), a change in physical activity (n = 726, 48%), talking to colleagues to get information (n = 716, 47%), and using humour or laughing (n = 623, 41%; Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058).

The majority of participants felt well-supported by their friends and/or family (n = 1389, 91%) and colleagues (n = 1254, 83%; Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058). More than half felt well-supported by the management at their workplace (n = 864, 57%) and by global or national societies (n = 864, 57%; Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058). Only 39% (n = 585) reported feeling well-supported by their government. During this time, 75% (n = 1142) felt valued by the public and 60% (n = 908) felt valued by their work organisation.

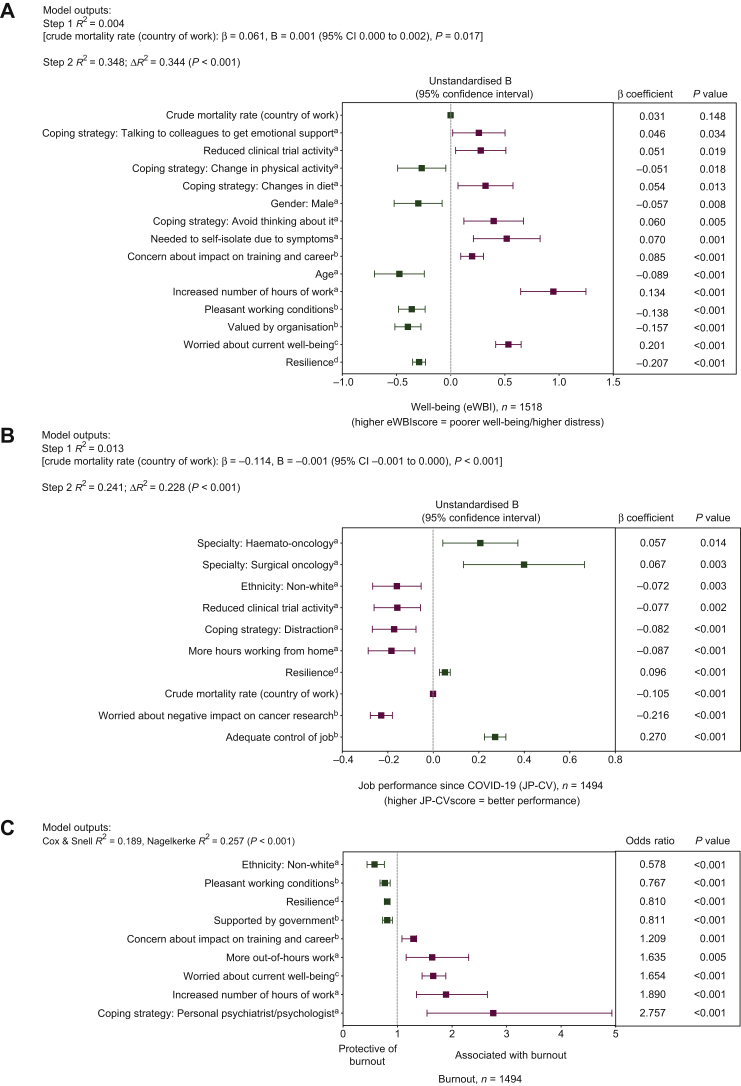

Predictors of well-being, burnout, and job performance since COVID-19

Correlational analyses were conducted on participants who stated their country of practice (n = 1519) to explore if there was an association between the estimated COVID-19 crude mortality rate and key study measures in survey I. There was a statistically significant relationship between crude mortality rate and well-being [r(1519) = 0.061, P < 0.05] and JP-CV [r(1519) = −0.115, P < 0.01]; as the crude mortality rate increases, there is poorer well-being and JP-CV. This was controlled for in the following regression analyses. Feeling burnout varied between countries but was not associated with COVID-19 crude mortality rate (P > 0.05).

Regression analyses showed that lower levels of distress was significantly (P < 0.05) associated with age above 40 years, male gender, having pleasant working conditions, feeling valued by their organisation, a change in physical activity, having higher levels of psychological resilience, no increase in working hours, no reduction in their clinical trial activity, having no concern about the impact of COVID-19 on their training and career, no experience of self-isolation due to COVID-19 symptoms, not feeling worried about personal well-being, no changes in diet, not ‘talking to colleagues for emotional support’, and choosing not to ‘avoid thinking about things’ (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Hierarchical multiple regression and multiple logistic regression analyses of predictive variables associated with (A) self-reported well-being (n = 1518), (B) job performance since COVID-19 (JP-CV) (n = 1494), and (C) burnout (n = 1494), respectively.

a Dichotomous variable (0 = no, 1 = yes; 0 = ≤ 40 years, 1 = >40 years; or 0 = white; 1 = non-white).

b Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

c Likert scale (1 = not at all; 5 = extremely).

d Bipolar scale (1 = low resilience; 9 = high resilience).

COVID-19, coronavirus disease; JP-CV, job performance since COVID-19; eWBI, expanded Well-being Index.

Higher JP-CV scores were significantly (P < 0.05) predicted by white ethnicity, by specialists in surgical oncology or haematology, having adequate job control, higher level of psychological resilience, having no reduction in their clinical trial activity, not working more hours from home, not worried COVID-19 will have a negative impact on cancer research in their institution, and not using ‘distraction’ as a coping strategy (Figure 3B).

Burnout was significantly (P < 0.05) associated with having more out-of-hours work, increased number of working hours, concern about the impact of COVID-19 on training or career, feeling worried about well-being, and access to psychiatrist or psychologist, those from white ethnicity, those who reported working in unpleasant working conditions, feel unsupported by their government, and had lower levels of psychological resilience (Figure 3C).

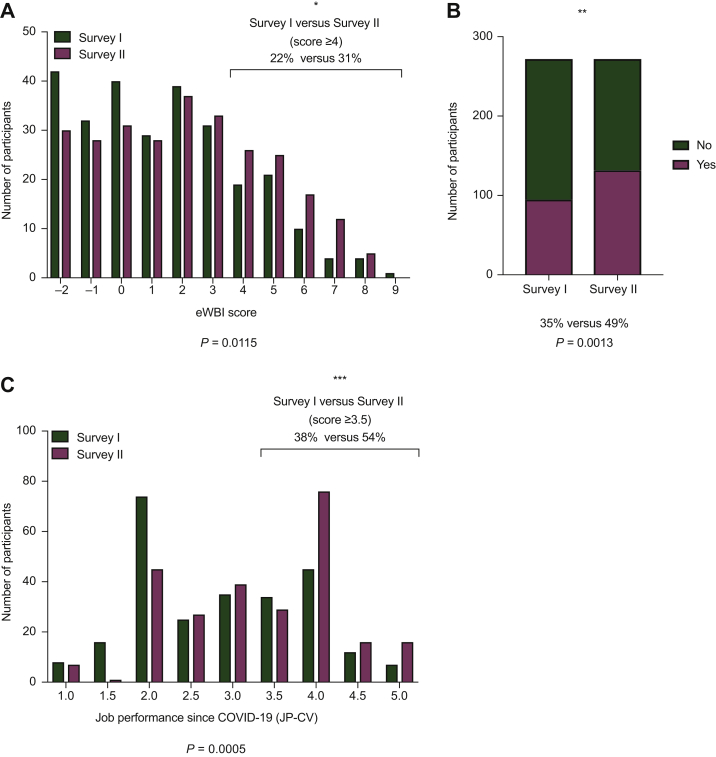

Subgroup analysis of participants who completed both surveys I and II

In survey II (July/August 2020), there were 272 participants from survey I who agreed to longitudinal follow-up of their responses to both surveys. Compared with survey I, there was a significant increase in the proportion of participants at risk of distress (eWBI score of ≥ 4) (31% versus 22%, P = 0.0115; Figure 4A) and self-reporting burnout (49% versus 35%, P = 0.0013; Figure 4B). The proportion of participants reporting favourable JP-CV score (mean score ≥ 3.5) increased from 38% to 54% (P = 0.0005; Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Paired longitudinal comparison between survey I (April/May 2020) and survey II (July/August 2020) of key measures: (A) self-reported well-being, (B) burnout, and (C) job performance since COVID-19 (JP-CV), during the COVID-19 crisis among those who completed both surveys (n = 272).

(∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001).

COVID-19, coronavirus disease; JP-CV, job performance since COVID-19; eWBI, expanded Well-being Index.

Discussion

The importance of well-being and burnout, and their impact on delivering health care, has increasingly been recognised over the years. The COVID-19 pandemic poses additional, extreme challenges on health care systems worldwide and health care professionals have to maintain patient care while facing personal risks. However, reports on the immediate and long-term effects of such a crisis on health care professionals are limited. In a survey of Italian doctors (hospital, primary care, and freelance) during the first lockdown period (March 2020), well-being (using WHO-5 Well-Being Index) was rated poor by 59%.20 The authors noted the need for follow-up surveys to monitor well-being and distress.20 The ESMO Resilience Task Force survey collaboration provides the largest and most comprehensive report on the current well-being of oncology professionals in response to the COVID-19 pandemic across the world.

Survey I revealed that oncologists working in different countries varied in terms of their perceived well-being and JP-CV, and there appeared to be worse self-reported well-being and JP-CV in countries with a higher COVID-19 crude mortality rate. A similar finding was reported among Spanish health care workers, where there were higher distress levels in areas with the highest incidence of COVID-19.21 Encapsulating the dynamic changes of COVID-19 globally for comparison is challenging particularly because of discordant methodology for cases and deaths between countries. We felt the estimated COVID-19 crude mortality rate was a measure that could represent the situation most reproducibly and accurately at the time. However, most countries have experienced regional variation of mortality rate.

In this survey series, the eWBI was selected to measure well-being. The self-reported eWBI, developed initially at Mayo Clinic,15,16,17 measures six dimensions of distress and well-being. It is a validated screening tool used to measure well-being over time in large cohorts of US clinicians and nonclinicians.15,16,17 To our knowledge, this is the first large survey to report on the utilisation of the eWBI in a global setting.

There are multiple methods of assessing burnout in the literature.1 The Maslach Burnout Inventory is the most extensively used.22 While historically considered the gold standard, it is recognised that other instruments that are brief and have the ability to screen for multiple dimensions of distress may be more practical for health care professionals to complete in busy working environments. In this survey series, we have used participant answers to the specific burnout question from the eWBI as a readout for prevalence of feeling burnout at a time point. Our intention was to establish how participants consider themselves feeling burnout which can be easily assessed over time. The rates of self-reported ‘feeling burnout’ described in this survey series are in keeping with burnout rates reported in earlier studies that used different validated methods to assess burnout in oncologists (34%-70%).2,23, 24, 25

We found consistently that, among others, working hours and participants' psychological resilience were significant factors associated with overall better well-being, level of burnout, and JP-CV. Other notable findings were that the risk of distress and burnout appeared to be significantly higher in female compared with male colleagues. Similarly, well-being and burnout rates were worse among young oncology professionals (aged ≤40 years). There were also other critical findings related to clinical practice noted. A large majority (78%) of participants were concerned for their personal safety at work. More than a quarter of participants did not have adequate access to personal protective equipment, and 19% did not feel confident in being able to access COVID-19 testing if required. Over two-thirds of oncology professionals noted a change in professional duties with more hours working from home and increased use of remote consultations being common reasons. These findings reflect the fact that COVID-19 has forced the rapid adoption and optimisation of telemedicine as an alternative mode maintaining the delivery of patient care while reducing footfall.26

Our survey series has shed light on various well-being support and coping strategies used by survey participants in response to the circumstantial changes imposed by COVID-19. However, only slightly more than half of the participants reported having access to well-being support services. This raises some concern about the equitable provision and/or awareness of support to the oncology profession. A supportive institutional programme was noted as a significant factor affecting both anxiety and depressive symptom levels during COVID-19 in a survey of researchers in the field of radiation oncology.27 In addition, the authors reported the feeling of a little or a lot of guilt being more abundant when self-perceived productivity declined.

Although the ESMO Resilience Taskforce first survey had over 1500 participants representing >100 countries globally, it has the inherent limitations by virtue of primarily being a membership survey with 90% of participants being ESMO members. It is not possible to establish the proportion of oncology professionals who participated in the survey globally. The number of participants varied across countries with the majority from Europe [highest participation from the UK (n = 174), Italy (n = 124), Spain (n = 102), Germany (n = 84), and India (n = 82)]. Most participants were doctors with 70% medical oncologists. Importantly, 22% of survey I participants were trainees which is in keeping with the current proportion of trainee doctors within the ESMO membership (23%). There were representative proportions for age (45% ≤ 40 years) and gender (51% male, 49% female). Important considerations for the survey design were balancing the time to complete the survey, complexity of questions in an international setting where English may not be the first language of participants, and key information of interest for oncology professionals and organisations. This meant that brief, concise tools assessing key outcomes of interest were selected in order to minimise the burden of completing these surveys during these unprecedented COVID-19 times.

Our findings are based on self-reported experiences of oncology health care professionals who were aware of the surveys and decided to participate. Therefore, there is a potential for bias. Nevertheless, this survey provides a snapshot of the acute reaction of oncology professionals to COVID-19 across different countries. We believe that the observations made here will be dynamic as the pandemic evolves, and further strengthened by the ongoing longitudinal analyses, which will be reported and obtained in subsequent surveys.

The key strength of this survey series is the ability to analyse important outcomes of interest over time. In this report, we presented well-being at two time points 3 months apart and observed that in this longitudinal cohort of participants, poor well-being and feeling burnout have increased. However, job performance improved and may be a reflection of the increase in knowledge, education, and experience managing cancer patients in the COVID-19 era. Although the improved self-perceived JP-CV noted is reassuring for patient care, this will be continually assessed as part of subsequent surveys, together with the long-term impact on well-being and burnout, in order to evaluate if job performance is maintained.

Supporting well-being and minimising the risk of burnout are priorities in order to ensure patient management pathways and cancer care are not additionally compromised as a result of COVID-19. The results of the ESMO Resilience Taskforce surveys will contribute to raising awareness and developing support solutions for individuals, hospital organisations, and societies. Measures such as taking action on factors associated with more favourable outcomes in this survey including tackling issues in relation to working hours, addressing concerns with regard to the impact of COVID-19 on training or career and clinical trials, and improving staff resilience to change are essential.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for taking part, national societies and organisations who helped distribute the survey. We also thank Francesca Longo, Mariya Lemosle, and Katherine Fumasoli from the ESMO Head Office for providing vital administrative support for the delivery of the survey programme.

Funding

European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO): For license to use Qualtrics (online survey platform) and Flourish (data visualisation) software, and publication of figure fee.

Disclosure

SB reports research grant (institution) from AstraZeneca, Tesaro, and GSK; honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, MSD, GSK, Clovis, Genmab, Immunogen, Merck Serono, Mersana, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, Roche and Tesaro outside the submitted work. KHJL is currently funded by the Wellcome-Imperial 4i Clinical Research Fellowship, and reports speaker honorarium from Janssen outside the submitted work. KP reports personal fees from Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Hoffmann La Roche, Mundi Pharma, and PharmaMar; and other fees paid to institution from Vifor Pharma, TEVA, and Sanofi outside the submitted work. CO reports research funding and honoraria from Roche; travel grant and honoraria from Medac Pharma and Ipsen Pharma; and travel grant from PharmaMar outside the submitted work. ML acted as a consultant for Roche, AstraZeneca, Lilly, and Novartis, and received honoraria from Theramex, Roche, Novartis, Takeda, Pfizer, Sandoz, and Lilly outside the submitted work. CBW reports speaker honoraria, travel support, and serving on the advisory board in Bayer, BMS, Celgene, Roche, Servier, Shire/Baxalta, RedHill, and Taiho; speaker honoraria from Ipsen; and advisory board in GSK, Sirtex, and Rafael outside the submitted work. PG reports personal fees from Roche, MSD, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, AbbVie, Novartis, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Blueprint Medicines, Takeda, Gilead, and ROVI outside the submitted work. TA reports personal fees from Pierre Fabre and CeCaVa; personal fees and travel grants from BMS; grants, personal fees, and travel grants from Novartis; and grants from NeraCare, Sanofi, and SkylineDx outside the submitted work. JBAGH reports personal fees for advisory role in Neogene Tx; grants and fees paid to institution from BMS, MSD, Novartis, BioNTech, Amgen; and fees paid to institution from Achilles Tx, GSK, Immunocore, Ipsen, Merck Serono, Molecular Partners, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics, Third Rock Ventures, and Vaximm outside the submitted work. CH reports private company Hardy People Ltd. outside the submitted work. The remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Figure S1.

Working environment during the COVID-19 crisis (n = 1520).

References

- 1.Murali K., Makker V., Lynch J., Banerjee S. From burnout to resilience: an update for oncologists. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:862–872. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_201023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banerjee S., Califano R., Corral J. Professional burnout in European young oncologists: results of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Young Oncologists Committee Burnout Survey. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(7):1590–1596. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng K.Y.Y., Zhou S., Tan S.H. Understanding the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with cancer, their caregivers, and health care workers in Singapore. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1494–1509. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomaier L., Teoh D., Jewett P. Emotional health concerns of oncology physicians in the United States: fallout during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee M.C.C., Thampi S., Chan H.P. Psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic amongst anaesthesiologists and nurses. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(4):e384–e386. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannampallil T.G., Goss C.W., Evanoff B.A. Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Civantos A.M., Bertelli A., Goncalves A. Mental health among head and neck surgeons in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41(6):102694. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahlster S., Sharma M., Lewis A.K. The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on critical care resources and providers: a global survey. Chest. 2021;159(2):619–633. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.09.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Sulais E., Mosli M., AlAmeel T. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physicians in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(5):249–255. doi: 10.4103/sjg.SJG_174_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Firew T., Sano E.D., Lee J.W. Protecting the front line: a cross-sectional survey analysis of the occupational factors contributing to healthcare workers' infection and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e042752. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgantini L.A., Naha U., Wang H. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid turnaround global survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0238217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y., Wang J., Luo C. Comparison of burnout frequency among oncology physicians and nurses working on the frontline and usual wards during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):e60–e65. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdessater M., Roupret M., Misrai V. COVID19 pandemic impacts on anxiety of French urologist in training: outcomes from a national survey. Prog Urol. 2020;30(8-9):448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osama M., Zaheer F., Saeed H. Impact of COVID-19 on surgical residency programs in Pakistan; a residents' perspective. Do programs need formal restructuring to adjust with the “new normal”? A cross-sectional survey study. Int J Surg. 2020;79:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyrbye L.N., Satele D., Shanafelt T. Ability of a 9-item well-being index to identify distress and stratify quality of life in US workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(8):810–817. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyrbye L.N., Satele D., Sloan J., Shanafelt T.D. Utility of a brief screening tool to identify physicians in distress. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):421–427. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyrbye L.N., Satele D., Sloan J., Shanafelt T.D. Ability of the physician wellbeing index to identify residents in distress. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:78–84. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00117.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO Cotronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2020. https://covid19.who.int/2020 Available at.

- 19.worldometer Countries in the World by Population. 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/population-by-country/ Available at.

- 20.De Sio S., Buomprisco G., La Torre G. The impact of COVID-19 on doctors' well-being: results of a web survey during the lockdown in Italy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(14):7869–7879. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202007_22292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romero C.S., Delgado C., Catala J. COVID-19 psychological impact in 3109 healthcare workers in Spain: The PSIMCOV group. Psychol Med. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maslach C., Jackson S. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blanchard P., Truchot D., Albiges-Sauvin L. Prevalence and causes of burnout amongst oncology residents: a comprehensive nationwide cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(15):2708–2715. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shanafelt T.D., Gradishar W.J., Kosty M. Burnout and career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(7):678–686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.8480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shanafelt T.D., Raymond M., Horn L. Oncology fellows' career plans, expectations, and well-being: do fellows know what they are getting into? J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):2991–2997. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCall B. Could telemedicine solve the cancer backlog? Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2(9):E456–E457. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhont J., Di Tella M., Dubois L. Conducting research in radiation oncology remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic: coping with isolation. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2020;24:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2020.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Working environment during the COVID-19 crisis (n = 1520).