Abstract

The proteomics of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples has advanced significantly during the last two decades, but there are many protocols and few studies comparing them directly. There is no consensus on the most effective protocol for shotgun proteomic analysis. We compared the in-solution digestion with RapiGest and Filter Aided Sample Preparation (FASP) of FFPE prostate tissues stored 7 years and mirroring fresh frozen samples, using two label-free data-independent LC-MS/MS acquisitions. RapiGest identified more proteins than FASP, with almost identical numbers of proteins from fresh and FFPE tissues and 69% overlap, good preservation of high-MW proteins, no bias regarding isoelectric point, and greater technical reproducibility. On the other hand, FASP yielded 20% fewer protein identifications in FFPE than in fresh tissue, with 64–69% overlap, depletion of proteins >70kDa, lower efficiency in acidic and neutral range, and lower technical reproducibility. Both protocols showed highly similar subcellular compartments distribution, highly similar percentages of extracted unique peptides from FFPE and fresh tissues and high positive correlation between the absolute quantitation values of fresh and FFPE proteins. In conclusion, RapiGest extraction of FFPE tissues delivers a proteome that closely resembles the fresh frozen proteome and should be preferred over FASP in biomarker and quantification studies.

Keywords: FFPE, protein extraction, RapiGest, FASP, LC-MS/MS, label-free data-independent acquisition

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Novel biomarkers as well as targets for novel treatments have been identified in biological material from patients with various diseases, using high-throughput proteomics technologies [1, 2]. Discovery of biomarkers is an essential part of biomedical research as biomarkers can facilitate disease detection and diagnosis, understanding the mechanisms of development and progression and can provide clues for new, more efficient treatments. Critical to these studies is the availability of patient biological material, especially tissue, as it is the site of disease initiation and progression and provides direct link to pathophysiology and understanding of disease-associated mechanisms. Freshly frozen tissue is considered the first choice for proteomic work, as proteins are snap frozen in usually short period after tissue removal and preserved in their natural state. However, the preparation and storage of such tissue is difficult and expensive. Furthermore, unless tissue is frozen routinely, which is usually not the case, prospective collection of sufficient numbers of frozen samples imposes an unacceptable delay. Procuring large tissue cohorts for retrospective studies represents the down side of this material. Another opportunity for conducting biomarker investigations exists within a vast archive of samples in hospitals worldwide that have been preserved by formalin fixation and paraffin embedding (FFPE). FFPE tissues can be stored for decades or more at room temperature while retaining cellular morphology, removing much of the cost and difficulty of sample storage. More importantly, FFPE samples from surgery or autopsies are stored routinely (and in most cases, indefinitely). Thus, vast numbers of specimens stored in hospitals worldwide hold valuable information about disease progression, patient’s response to therapies, disease outcome and survival and therefore are crucial for retrospective studies [3–6].

Due to the formalin induced crosslinking between amino acids that results in disruption of protein structure and formations of chimera-like proteins [7, 8], for a long time, FFPE tissues were considered not suitable for proteomics. However, with the invention of the so called heat-induced antigen retrieval (HIAR) technique [9] for overcoming the cross-linked nature of FFPE tissues, various research groups started testing the possibility of using FFPE tissues in proteomics studies, by top-down and bottom-up approaches.

Within the top down approaches, studies on FFPE tissues using Western blot, immunoassays, ELISA, antibody microarrays and protein arrays, reported in general successful use of this material [10]. On the other hand, studies using electrophoretic fractionations of extracted proteins by 1-D PAGE and 2-D PAGE/DIGE reported controversial findings. When compared to frozen lysate patterns, some groups reported comparable but not identical FFPE protein patterns [11–14], while others yielded completely different patterns [15–17], pointing out that for these proteomics techniques, an efficient method for complete overcoming of the cross links and modifications in FFPE tissues is yet to be discovered.

Shotgun proteomics has been successfully applied in the analysis of FFPE samples in a great number of studies, in general with good overlapping of identifications compared to fresh tissues [10]. This continues to be improved in recent years due to advances in extraction/digestion procedures and increases in sensitivity and resolution of the LC-MS/MS instrumentation [18–20]. Several procedures for removal of strong detergents from protein extraction buffers such as vacuum filtration [21], dialysis [22], precipitation [23], Filter-Aided Sample Preparation (FASP) method [19, 20, 24, 25] prior to subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis or using an acid-labile surfactant such as RapiGest [26, 27] that permits direct MS analysis without further sample processing, have been successfully demonstrated. Different protocols have been tested, using several types of mass spectrometers with label-based or label-free quantification [10]. These results have been verified by a number of validation studies using western blotting and immunohistochemistry, thereby confirming the robustness of the technique for FFPE tissue analysis (for details please see [10]). In addition, several studies [19, 28–30] using shotgun proteomics of FFPE samples were able to identify and quantify posttranslational modifications (PTMs) which further increase the possibilities that FFPE tissues have to offer.

In spite of the growing number of shotgun proteomics studies analyzing FFPE tissues, there is currently no consensus on the optimal protocol for shotgun proteomic analysis. Only a few studies critically compare the performance of different protocols [24, 31, 32]. This study aimed to compare critically the performance of two sample preparation methods for shotgun proteomic analysis of FFPE tissue: (1) the RapiGest protocol, which is an in-solution digestion method broadly used [33–35] and reported to be superior to other tested methods for FFPE extraction [26, 27] and the modified FASP method [36], as an improved version of the original FASP method [37] which also has been reported to deliver superior results on FFPE tissues [19, 20, 24, 25]. Prostate tissue was chosen as a model in consideration of its high proteome complexity and availability of samples with long archival periods in freezer or formalin. Data were comparatively evaluated in terms of protein and peptide identifications in fresh frozen and FFPE samples, analysis of the fresh and FFPE tissues representative proteome (molecular weight distribution, distribution according to protein’s pI, cellular component analysis of proteins and quantitation accuracy), analysis of the effects of fixation and subsequent tissue processing and technical reproducibility.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

1. Tissue samples

The samples used in this study were surgical tissues from 3 patients with benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) obtained by Trans Urethral Resection of the Prostate gland (TURP). Informed consent for the use of these tissues for research purposes in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki was obtained from the patients. The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts (09–1221/1). Tissue samples were split into two portions at the Histopathology Laboratory of the Clinical Hospital Acibadem Sistina, Skopje. One portion was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. The other portion was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h, dehydrated with a graded series of ethanol, and embedded in paraffin. FFPE tissues were stored at room temperature. Both fresh/frozen and FFPE samples were used for analysis 7 years later.

2. Protein extraction from fresh frozen tissue samples

The frozen tissues (10–15 mg per sample) were pulverized in liquid nitrogen. The resultant tissue powder was weighed and resuspended in 1:20 ratio (w/v) of Lysis buffer (4% SDS, 5mM MgCl2×6H2O, 10 mM CHAPS, 100 mM NH4HCO3, 0.5 M DTT). The samples were thoroughly mixed, allowed to dissolve by sonication in an ice bath for 30 min. If samples were too viscous, they were put through a 21G needle a few times. The protein concentration in all samples was measured using the Bradford method [38] in duplicate against a standard curve of bovine serum albumin (BSA) and stored at −80°C until use.

3. Protein extraction from FFPE tissue blocks

Proteins from FFPE tissues were isolated using 3 serial 10 μm thick sections with an area of approximately 80 mm2 for each of the isolations. Tissues were deparaffinized in three changes of with xylenes for 5 min followed by rehydration with a graded series of ethanol (95%, 70% and 50%) and water for 5 min. After air drying for 30 min at room temperature, the tissues were weighed and resuspended in 1:20 ratio (w/v) of Lysis buffer (4% SDS, 5mM MgCl2×6H2O, 10 mM CHAPS, 100 mM NH4HCO3, 0.5 M DTT). The samples were vortexed, sonicated in an ice bath for 30 min, and incubated at 95°C for 30 min. The samples were then cooled on ice for 5 minutes, vortexed and incubated at 80 °C for 2 h with mixing at 1000 rpm. After cooling on ice for 5 min and sonication for 15 min, the protein content was quantified by Bradford method and stored at −80°C until use.

4. Sample pools

Pools of extracted proteins from 3 fresh frozen and 3 corresponding FFPE samples were made respectively, each in 3 technical replicates per protocol, resulting in total of 12 pool samples (RapiGest_fresh_pool 1–3, RapiGest_FFPE_pool 1–3, FASP_fresh_pool 1–3 and FASP_FFPE_pool 1–3). For each pool, 10 μg protein from each individual sample was used, giving total of 30 μg protein per pool. After tryptic digestion, equal amount of each of the 3 technical replicates were combined into a pool representative named S POOL (Supplementary document 1, Figure S1).

5. RapiGest protocol

The RapiGest [35] protocol by Oswald et al., [33] was used with some modifications. Briefly, a portion of each individual sample in Lysis buffer containing 100 μg of protein was adjusted to 100 μl with Lysis buffer (4% SDS, 5mM MgCl2×6H2O, 10 mM CHAPS, 100 mM NH4HCO3, 0.5 M DTT) and 150 μl of methanol and 38 μl of chloroform were added. After vortexing vigorously for about 1 min and centrifuging at 5,000 × g for 5 min for phase separation, the protein forms a white disc at the interface between the methanol/water layer and the chloroform layer. After aspirating most of the upper layer of methanol/water, 112 μl of methanol was added, mixed and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min to pellet the protein. Proteins were dissolved in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate containing 0.1% RapiGestTM detergent (Waters Corp.) in ratio 2.5:1 (w/v). DTT was added (0.12 μmol/50 μg protein) and the solution was sonicated and boiled for 5 minutes. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay. Pools from fresh and FFPE samples were made as described in Section 4. The volume of each pool containing total of 30 μg protein was adjusted to 35 μl with 0.1% RapiGest in 50 mM NH4HCO3 and heated at 80°C for 15 minutes. Sample pools were reduced in 5 mM DTT for 30 minutes at 60°C, followed by alkylation in 15 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) in the dark for 30 minutes at room temperature. Trypsin (TRYPSEQM-RO ROCHE) was added at a 1:100 trypsin:protein ratio by mass and incubated overnight at 37 C. Following the digestion, to hydrolyze the RapiGest, 5% TFA was added to final concentration of 0.5% and samples were incubated at 37°C for 90 minutes. After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm, at 6°C for 30 minutes, supernatants were transferred into the Waters Total Recovery vial, diluted with water to 0.4 μg/μl protein and equal volume of 50 fmol/μl of a digest of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) in 5% ACN, 0.1% formic acid (FA) was added as an internal standard protein. The final concentration of protein in the pooled samples was 200 ng/μl and the final concentration of ADH was 25 fmol/μl.

6. FASP protocol

Pools from fresh and FFPE samples containing 30 μg protein were adjusted to 30 μl final volume with lysis buffer. The modified FASP protocol by Potriquet et al., [36] was used with several modifications. As Lysis buffer contained 0.5 M DTT, sample pools were heated at 95°C for 5 minutes and left at room temperature for 25 min. Proteins were alkylated in 40 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) in the dark for 30 minutes at room temperature. Eight volumes of Urea buffer (8M Urea, 10% isopropanol in 100 mM NH4HCO3) was then added to the sample pools. Pierce™ Protein Concentrators PES, 30K MWCO, 0.5 mL (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was pre-wet with 60% isopropanol prior to addition of the samples in Urea buffer. Sample pools were then transferred to the columns, centrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 min and the flow through was discarded. Detergent removal by buffer exchange was performed in two successive washes with eight volumes of Urea buffer with centrifugation at 15,000 g for 30 min. Urea was then removed by two washes with Wash buffer 1 (10% isopropanol in 50 mM NH4HCO3), followed by two washes with Wash buffer 2 (50 mM NH4HCO3) with centrifugation at 15000 g for 30 min between each wash. Trypsin (TRYPSEQM-RO ROCHE) was added at a 1:50 trypsin:protein ratio by mass and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Peptides were recovered using an initial spin of 15000 g for 10 min followed by two washes with 50 μL of 50 mM NH4HCO3. The collected peptides were acidified with 1.0% FA to final concentration of 0.1% and transferred into the Waters Total Recovery vial. A digest of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) in 5% ACN, 0.1% formic acid (FA) with concentration of 375 fmol/μl was added as an internal standard protein to final concentration of 25 fmol/μl. The final protein concentration was 200 ng/μl.

7. Nano- LC-MS/MS using label free data-independent MSE and UDMSE acquisition

A label-free LC-MS/MS protein profiling was performed using an ultra-performance liquid chromatography system ACQUITY UPLC® M-Class (Waters Corporation) coupled with SYNAPT G2-Si High Definition Mass Spectrometer (Waters Corporation) equipped with a T-Wave-IMS device. Data were obtained using two label-free data-independent acquisition modes: classical MSE [34] and ion-mobility separation (IMS) enhanced MSE named ultradefinition MSE (UDMSE) [39]. These methods provide absolute abundance estimation of proteins in complex mixtures if a known quantity of predigested internal standard protein is spiked into the mixture after it has been digested [40].

For each sample pool, one test run in MSE mode and initial data processing with ProteinLynx Global Server (PLGS, version 3.0.3, Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) was done for quality assurance testing and determination of the exact protein concentration. Optimal loading for MSE and UDMSE runs was determined by testing S POOL sample from RapiGest protocol on fresh frozen tissue, starting from 100–300 ng per run and processing in ProteinLynx Global SERVER ((PLGS, version 3.0.3, Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA)). For protocol and tissue type comparisons, S pool samples were run with optimal column load of 250 ng in triplicate in MSE and UDMSE respectively. For accessing technical reproducibility of the two tested protocols, individual pools (RapiGest_fresh_pool 1–3, RapiGest_FFPE_pool 1–3, FASP_fresh_pool 1–3 and FASP_FFPE_pool 1–3) were run with optimal column load of 250 ng in UDMSE only, in one technical replicate.

Peptides were trapped on a ACQUITY UPLC M-Class Trap column Symmetry C18, 5μm particles, 180 μm×20mm, (Waters Corporation), for 3 min at 8 μL/min in 0.1% solvent B (0.1% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile)/99.9% solvent A (0.1% (v/v) formic acid, aqueous). The injection was followed by a needle wash with 1% acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. Peptide separation was done on ACQUITY UPLC M-Class reverse phase C18 column HSS T3, 1.8 μm, 75μm×250mm (Waters Corporation) at a flow rate of 300 nl/min using 90 min multistep concave gradient for nanoLC separation [41]. Briefly, column was equilibrated for 5 min at 1% B and then solvent B was increased in a 90-min gradient between 5 and 40%, post-gradient cycled to 95% B for 7 min, followed by 8 min post-run equilibration at 1% B. The analytical column temperature was set to 55 °C.

Lock mass compound Glu-1-Fibrinopeptide B (EGVNDNEEGFFSAR) was delivered by the auxiliary pump of the LC system at 500 nl/min to the reference sprayer of the NanoLockSpray source of the mass spectrometer. The concentrations of Glu-1-Fibrinopeptide B in the reference solution (50% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) was 100 fmol/μL. Lock mass spectrum of doubly charged Glu-1-Fibrinopeptide B (m/z 785.8426) was produced every 45 s.

For all MS measurements, spectra were recorded in resolution positive ion mode with a typical resolving power of at least 25,000 FWHM (full width at half maximum) and sensitivity of > 7000 TDC equivalent counts/sec for the double charged Glu-1-Fibrinopeptide B ion (m/z 785.8426) infused directly at concentration of 100 fmol/μl. The time-of-flight analyzer of the mass spectrometer was calibrated with a Glu-1-Fibrinopeptide B in the m/z range 50 – 2000. Source settings included capillary voltage of 3.2 kV, extraction cone at 4V, sampling cone at 35 V, and source temperature of 80 °C. The cone gas N2 flow was 30 L/h. Analyzer settings included quadrupole profile set at auto with mass 1 as 1.25 Ma (dwell time 25% and ramp time 75%) and mass 2 as 0.17 Mb. The Step Wave settings in TOF acquisition mode were the following: wave velocity of 20 m/s and wave height 15 V for the StepWave 1 and StepWave 2 and wave velocity of 300 m/s and wave height 5 V for the Source Ion Guide. The Step Wave settings in TOF mobility acquisition mode were the following: wave velocity of 300 m/s and wave height 15 V, 15 V and 1 V for the StepWave 1 and StepWave 2 and Source Ion Guide, respectively. For IMS, wave height of 40 V was set. Traveling wave velocity was ramped from 900 m/s to 450 m/s over the full IMS cycle. Wave velocities in the trap and transfer cell were set to 311 m/s and 175 m/s, respectively and wave heights to 4 V. Spectra were collected over the mass range 50–2000 m/z with scan time of 0.5 s. For the MSE acquisition, collision energy was held at 4 V for low energy scan and ramped from 17 to 45 V for the high energy scan. For the UDMSE acquisition, collision energy was held at 0 V for low energy scan while for the high energy cycles, a look-up table file was put into the MS method to optimize precursor fragmentation in the transfer cell according to the procedure of Distiler at al., [39]. The following collision energy (CE) settings were applied throughout the whole study in the elevated energy scan: (i) ion-mobility bins 0–20: CE of 2 eV, (ii) ion-mobility bins 21–120: CE ramp from 10.6 eV to 50.4 eV, (iii) ion-mobility bins 121–200: CE ramp from 51 eV to 60 eV.

8. LC-MS/MS data analysis

Data processing, protein identification and quantification was done using ProteinLynx Global Server (PLGS) version 3.0.3 (Waters Corporation). The data were post-acquisition lock mass corrected using the doubly charged monoisotopic ion of [Glu1]-Fibrinopeptide B. Data was searched against the UniProtKB/ Swiss-Prot database containing 20 370 proteins (June 2020), to which yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (UniProt P00330) sequence was added. Optimized low energy (LE) and high energy (HE) threshold settings for PLGS data processing were determined by PLGS Threshold Inspector (Version 2.3 Build 2, Carper Soft) as 600 counts and 150 counts for LE and HE threshold, respectively. Precursor and fragment ion mass tolerances were automatically determined by PLGS during database searching. Typical range of RMS error for precursor and product ions for were ±5 and ±10 ppm, respectively. Search settings included up to one missed cleavage, carbamidomethyl cysteine (monoisotopic mass change, +57.02 Da) as a fixed modification and oxidized methionine (+ 15.99 Da), hydroxylation of asparagine, aspartic acid, proline or lysine (+ 15.99 Da), methylation of lysine (+ 14.02 Da), and formylation of lysine, N-term (+ 27.99 Da) as variable modifications. A minimum of two fragment ion matches was required per peptide identification and five fragment ion matches per protein identification, with at least one peptide matches per protein identification. The protein false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 1% threshold for database search in PLGS. The inputs used for quantification measurement were: internal standard protein, P00330; protein concentration: 25 fmol/μl.

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [42] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD021074 and DOI: 10.6019/PXD021074.

9. Proteomics data analysis

Reproducibility in the number of protein and peptide identifications was summarized as mean, standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV). The correlation between absolute abundance values of the common identified proteins (expressed as a mean fmols on column from 3 technical replicates) in fresh frozen and FFPE tissue extracts was estimated by Pearson correlation coefficient and data were illustrated with a scatter plot. Protein and peptide identifications in fresh frozen and FFPE samples, as well as reproducibility of quantitation, were summarized in box plot graphs, with median (−), 25th and 75th percentiles and mean (+) values shown. Independent samples Student t-test was used for testing differences between the means of two populations, with two tailed hypothesis test at the 0.05 level of significance applied. Graphical representation of the number of identified proteins was done using Venn Diagram Plotter (http://omics.pnl.gov/software/VennDiagramPlotter.php). Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the identified proteins was performed using the UniProtKB database and DICE GOnet tool for GO terms filtering and graphical representation of the results [43]. Unique peptides were filtered using neXtProt peptide uniqueness checker [44].

RESULTS

1. Selection of protein extraction protocol

The first step in the comparison of the fresh frozen and archival FFPE tissue samples was the selection of an efficient protein extraction protocol. The frozen tissues were pulverized with liquid nitrogen, while for the FFPE tissues, after deparaffinization and rehydration, we applied the heat-induced antigen retrieval (HIAR) technique as a leading method so far for reversing the cross-linked nature of FFPE tissues. The same lysis buffer and protein solubilisation were applied for both fresh/frozen and FFPE tissues at the start of the two tested protocols, followed by HIAR for FFPE tissues. The buffer for the HIAR technique was chosen based on detailed review of previous studies that have performed bottom-up mass spectrometry on FFPE tissues (extensively reviewed in Gustafsson et al. [10]). Most of these studies used SDS as solubilization agent in range from 2–4% and DTT as a reducing agent in range from 20–200 mM. In addition to these, we included CHAPS as a non-denaturing, zwitterionic detergent, useful for breaking protein-protein interactions.

2. Determination of the optimal column load

Successful, in-depth analysis of the proteome of clinical samples depends on many factors, among which are the acquisition mode, sensitivity and the speed of the mass spectrometer. It is well documented that MSE methods are very prone to column overloading which leads to overall loss of chromatographic resolution and lower numbers of identified peptides and proteins [39]. To investigate the question of the required sample quantity on our platform, we first analyzed different amounts of peptides ranging from 100–300 ng on-column loading amounts for two types of label-free data independent acquisition: MSE and UDMSE. Data processing with PLGS showed that 250 ng protein on column using 90 min gradient gave the highest number of identifications for both acquisition modes (Supplementary document 1, Figure S2). Loading amounts over 250 ng led to peak broadening and hence loss of peak capacity resulting in lower numbers of identified peptides and proteins.

3. Comparative evaluation of protein extraction efficiency in fresh frozen and FFPE samples

Initial experiments using pool representatives for each protocol and tissue type (S POOL) were carried out comparing extraction and digestion efficiencies. Four pool representatives (RapiGest_S pool_fresh, RapiGest_S pool_FFPE, FASP_S pool_fresh and FASP_S pool_FFPE) were run in triplicate under optimal column load of 250 ng protein on column, data were processed in PLGS 3.0.3 and searched against the UniprotKB/Swissprot human database (Supplementary data 1).

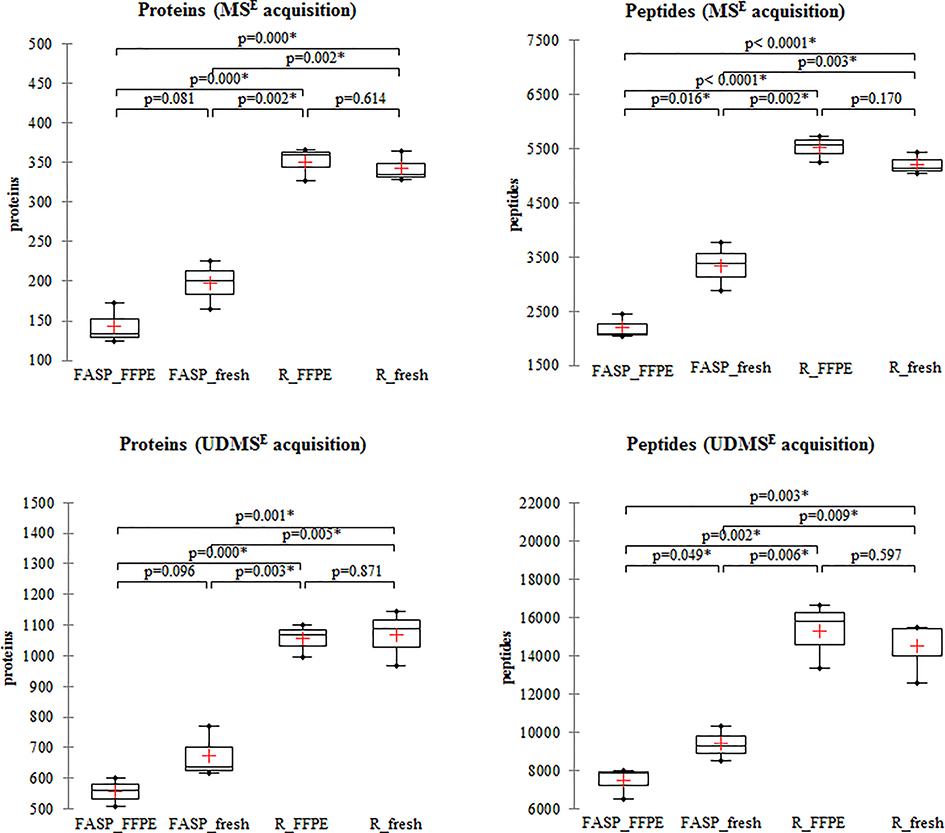

The number of protein identifications from fresh and FFPE tissues with RapiGest protocol did not differ significantly, with mean of 342 and 351 in MSE and 1067 and 1056 in UDMSE acquisition for fresh and FFPE, respectively (Figure 1). On the other hand, efficiency of FASP was lower for FFPE, yielding approximately 20% fewer protein and peptide identifications compared with fresh. Comparison of the digestion efficiencies of both protocols showed that RapiGest produced significantly higher number of protein identifications than FASP. RapiGest extracted 1.6 – 1.7 times greater number of proteins from fresh (t-test, p=0.002–0.005)) and 1.9–2.4 times greater number of proteins from FFPE (t-test, p<0.0001), detected with both acquisition modes.

Figure 1. Protein and peptide identifications from fresh frozen and FFPE samples by RapiGest and FASP protocol.

Representative S POOL samples from fresh frozen and FFPE tissues obtained with RapiGest and FASP protocols respectively were run in triplicate in MSE and UDMSE acquisition modes. The number of proteins and peptides obtained by processing with PLGS are plotted for each acquisition mode and technical replicate. In the box plot graphs, median (−), 25th and 75th percentiles and mean (+) are shown. Asterisk (*) indicate significant statistical difference (t-test, p <0.05). (Note that scales differ for MSE and UDMSE acquisition modes.)

Comparison of the common proteins among technical replicates of SPOOL samples revealed protein overlap of 70–88% (Supplementary document 1, Figure S3). Technical reproducibility of acquisitions was high, with coefficient of variation (CV) from 5–18% for proteins and 4–13% for peptides, respectively (Supplementary document 1, Table S1).

Representative proteomes for each tissue type were selected based on proteins replicating in at least two out of three injections, and these were used for the comparative analysis (Supplementary data 2). Using MSE acquisition, RapiGest extraction delivered 324 proteins from fresh frozen and 326 proteins from FFPE, while FASP extraction almost half less: 184 proteins from fresh frozen and 137 proteins from FFPE. The same trend was observed in UDMSE mode, but with significantly higher number of proteins in the representative proteomes: RapiGest extraction delivered 1015 proteins from fresh frozen and 1029 proteins from FFPE, while FASP extraction significantly less: 642 proteins from fresh frozen and 556 proteins from FFPE. On average, quantifiable proteins (proteins with absolute abundance value >0) in representative proteomes for each tissue type and protocol were about 80%.

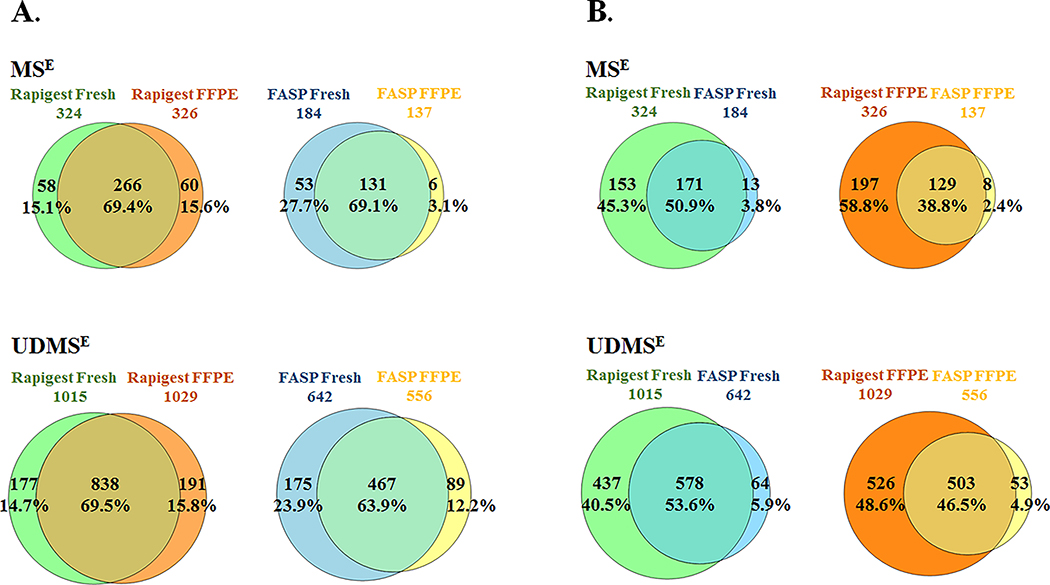

Comparison of the reference proteomes of fresh and FFPE tissues showed that with RapiGest protocol, common proteins were 266 (69.4%) and 838 (69.5%) in MSE and UDMSE acquisition modes respectively (Figure 2.A). RapiGest protocol yielded approximately the same number of proteins from both fresh and FFPE tissues and therefore the percentage of the unique proteins in fresh and FFPE tissues were practically the same (MSE: 15.1% fresh vs 15.6% FFPE; UDMSE: 14.7% fresh vs 15.8% FFPE). With FASP protocol, the percentage of common proteins between fresh and FFPE tissues was in the same range as with RapiGest (131 (69.1%) and 467 (63.9%) in MSE and UDMSE acquisition modes, respectively) but unique proteins in fresh tissue were 2 and 9 times more numerous than in FFPE, in UDMSE and MSE, respectively. The same was observed when analyzing only quantifiable proteins (Supplementary document 1, Figure S4). Direct comparison of RapiGest and FASP efficiency over fresh tissues showed 171 (50.9%) and 578 (53.6%) common proteins in MSE and UDMSE, respectively (Figure 2.B). Common proteins between protocols in FFPE tissues were slightly less (38.8% in MSE and 46.5% in UDMSE). RapiGest extraction yielded 12–24 times more unique proteins compared with FASP in MSE mode and 7–10 times greater in UDMSE mode, for fresh and FFPE tissues, respectively.

Figure 2. Comparison of the identified common and unique proteins between tissue types and protocols for sample preparation.

(A) Comparison of the fresh and FFPE tissues extracted with RapiGest and FASP protocols (B) Comparison of protocol efficiency over fresh and FFPE tissues. S POOL samples representative proteomes for each tissue type and protocol were selected based on proteins identified in at least two out of three technical replicates in MSE and UDMSE acquisition modes, respectively. For each comparison, total number of the quantified proteins per tissue type and protocol as well as common and unique proteins have been presented as number and percentage.

4. Analysis of the fresh and FFPE tissues representative proteomes

The representative proteomes of fresh and FFPE tissues were further analyzed in terms of distribution of proteins’ molecular weight, pI, cellular component analysis and correlation between absolute abundance values.

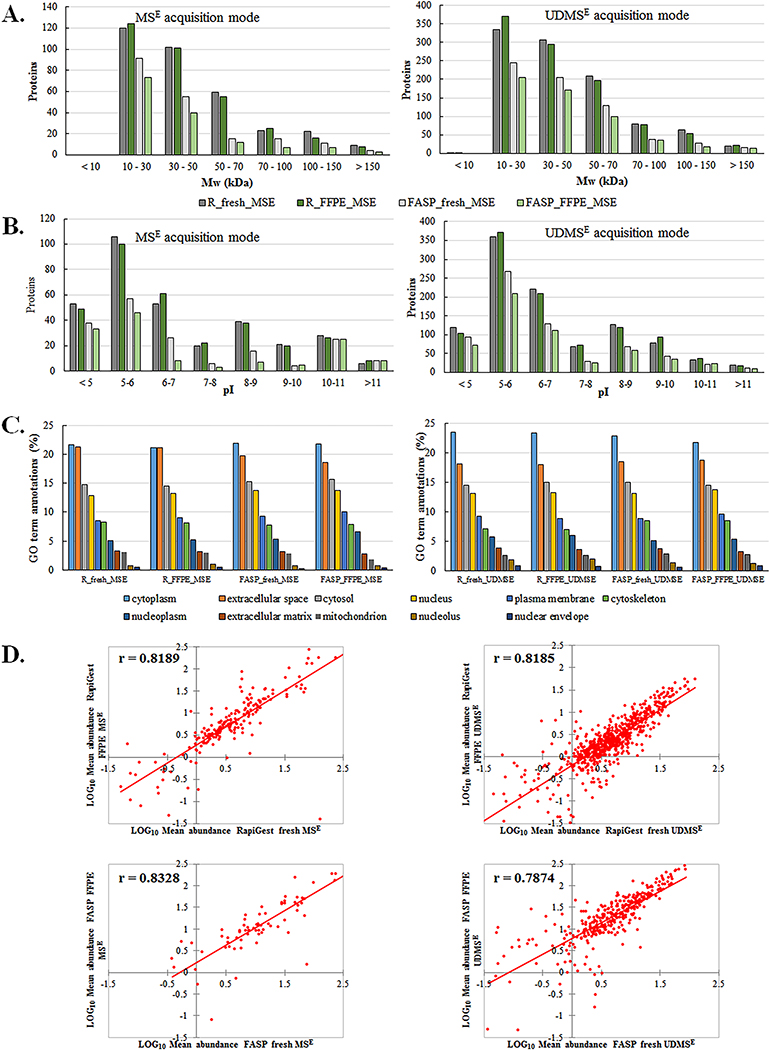

Molecular weight distribution of proteins extracted with RapiGest, showed almost no difference in Mw range up to 100 kDa and 16–27% more identifications from fresh tissue compared to FFPE in the 100–150 kDa range, with both MS acquisition modes (Figure 3.A). With FASP protocol, fresh tissue had about 20–25% more identifications than FFPE in each of the investigated Mw range up to 70 kDa, and this increased to up to 40% in the 70–100 kDa range. Protocol comparison of fresh tissue digestion efficiencies showed 20–50% more identifications with RapiGest in whole Mw range. With FFPE digestions, RapiGest produced 40–70% more identifications than FASP in each of the investigated Mw ranges.

Figure 3. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the fresh/frozen and FFPE tissue proteomes extracted with RapiGest and FASP protocol.

S POOL samples representative proteomes were selected based on proteins identified in at least two out of three technical replicates. Analysis was done based on the distribution of proteins according to: (A) molecular weight, (B) protein pI, (C) subcellular localization and (D) correlation between absolute abundance estimation values in the representative proteome from fresh frozen and FFPE samples. The mean protein abundances from the 3 technical replicates were calculated for common identified proteins between fresh/frozen and FFPE samples with two protocols and two modes of LC-MS/MS acquisition. Mean abundance values expressed as a mean fmols on column were Log10 transformed and values from fresh frozen proteins were plotted against corresponding values from FFPE samples. Pearson correlation coefficients are also reported.

RapiGest extraction showed almost identical numbers of extracted proteins in the whole pI range for fresh and FFPE samples, with differences below 10% (Figure 3.B). On the other hand, FASP protocol produced on average 20% fewer identifications in FFPE tissue in acidic (pI<6) and basic regions (pI>9) and over 50% less in pI range 6–9. At different pI ranges, there were significant differences between protocols. For fresh tissue, RapiGest gave significantly more identifications than FASP in the overall pI range (28–81% in MSE and 22–46% in UDMSE). For FFPE, the number of proteins extracted with RapiGest were more than double the number of proteins obtained with FASP in the whole pI range. But, when protocols are compared based on percentage of proteins in investigated pI ranges (Supplementary document, Figure S5), FASP shows higher percentage of acidic (pI<6) and basic proteins (pI>10), while RapiGest is superior in proteins with near neutral pI.

Cellular component analysis of the fresh and FFPE tissues representative proteome using Gene ontology (GO) annotations showed highly similar distribution of extracted proteins in cellular compartments, irrespective of tissue type and extraction protocols (Figure 3.C). The highest percentage are cytoplasmic, followed by nuclear, plasma membrane, mitochondrial and extracellular matrix proteins. Correlation between the absolute abundance values of proteins in the representative proteome of fresh frozen and FFPE samples showed highly significant (p<0.0001), high positive correlation in both extraction protocols with Pearson correlation coefficient ranging from 0.819–0.833 in MSE and 0.787–0.816 in UDMSE (Figure 3.D).

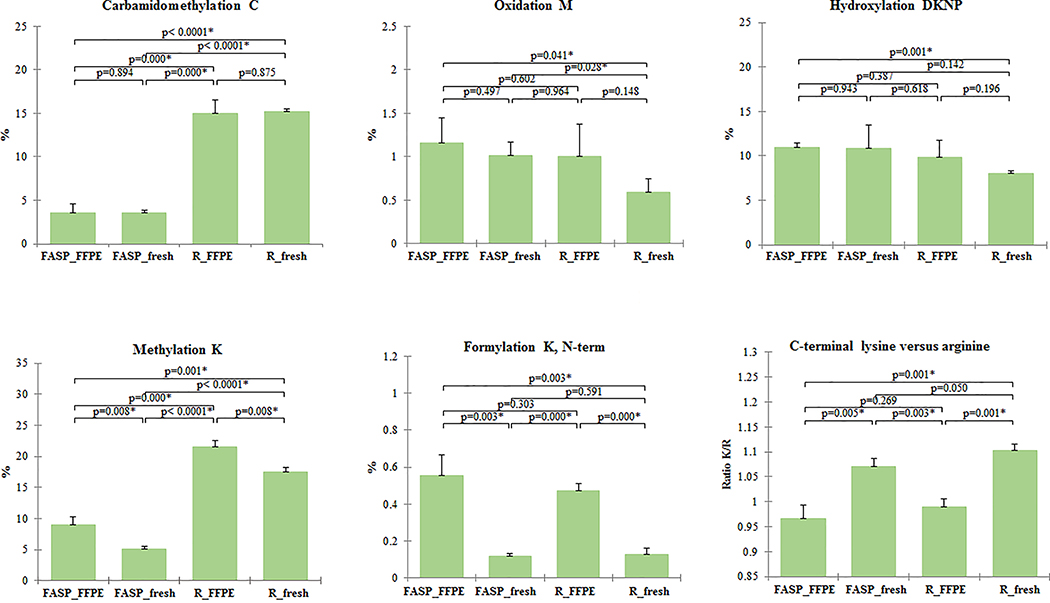

We also looked for the effect of fixation and subsequent tissue processing of FFPE tissues. Peptide lists from individually prepared pool samples in 3 technical replicates per protocol and tissue type were searched for post-translational modifications associated with sample processing (carbamidomethyl C, oxidized M) and post-translational modifications associated specifically with formalin fixation: hydroxylation of DKNP, methylation K and formylation of K, N-term [45]. We did not observe significant difference between fresh and FFPE tissues in post-translational modifications associated with sample processing, with both protocols, although higher number of methionine oxidations were observed in the FFPE tissue datasets (Figure 4). In addition, there was a borderline significance of increased oxidized M peptides in FASP fresh extraction compared to RapiGest fresh (t-test, p=0.028). With regard to posttranslational modifications associated with formalin fixation we observed significantly increased methylation (t-test, p RapiGest <0.008; p FASP<0.008) and formylation of lysine at N-term (t-test, p RapiGest <0.001; p FASP<0.003) in FFPE tissues (Figure 4). There was a small nominal increase, without statistical significance, in peptides with hydroxylated asparagine, aspartic acid, proline or lysine in FFPE samples compared with frozen.

Figure 4. Assessment of the effects of fixation and subsequent tissue processing on FFPE tissues.

Individually extracted pool samples (250 ng) from fresh frozen and FFPE tissues with RapiGest and FASP were searched for post-translational modifications (carbamidomethyl cysteine (C), oxidized methionine (M), hydroxylation of asparagine, aspartic acid, proline or lysine (DKNP), methylation of lysine (K), and formylation of lysine, N-term) and ratios of C-terminal lysine versus arginine (R) peptides. Mean and SD values for 3 technical replicates per protocol/tissue type are shown. The peptides with post-translational modifications were expressed as percentage of the total number of peptides. Asterisk (*) indicate significant statistical difference (t-test, p <0.05).

To determine whether formalin fixation impacts trypsin enzymatic specificity, the numbers of peptides with arginine and lysine C-termini were tabulated. We found that in fresh tissue, the percentage of peptides identified with arginine and lysine C-termini was 45.3±0.2% and 50.0±0.3%, respectively with RapiGest and 46.0±0.3% and 49.3±0.4%, respectively with FASP. In FFPE tissues, the percentages of peptides with arginine and lysine C-termini was highly similar: 48.3±0.4% and 47.8±0.4%, respectively with RapiGest and 49.1±0.7% and 47.4±1.0%, respectively with FASP. When ratios of C-terminal lysine to arginine were compared between fresh and FFPE tissues we found significant reduction in FFPE tissues (t-test, p RapiGest <0.001; p FASP<0.005) suggesting a loss of C-terminal lysine containing peptides due to inter- and intramolecular protein crosslinking caused by formaldehyde (Figure 4).

The effect of formalin fixation and paraffin embedding were also investigated in terms of peptide extraction efficiency. Individually prepared pool samples in 3 technical replicates per protocol and tissue type were searched for the number of unique peptides. The percentage of unique peptides extracted from 3 technical replicates with RapiGest protocol was 56.9±2.3% (Mean±SD) from fresh/frozen and 54.8±3.1% (Mean±SD) from FFPE tissues, corresponding to 68.9±2.9% (Mean±SD) and 69.8±5.5% (Mean±SD) unique proteins, respectively (Table 1). The percentage of unique peptides extracted with FASP was lower than ones obtained with RapiGest (47.0±2.6% (Mean±SD) from fresh/frozen and 47.9±1.2% (Mean±SD) from FFPE) leading to lower percentage of unique proteins identified (fresh/frozen: 62.1±4.2% (Mean±SD); FFPE: 61.8±3.7% (Mean±SD)). However, no difference in the extraction of unique peptides between fresh/frozen and FFPE was observed with both protocols. On the other hand, protocol comparison showed significantly higher number of unique peptides extracted with RapiGest from both fresh/frozen (t-test, p<0.007) and FFPE tissues (t-test, p<0.022), but this did not significantly impacted the number of identified unique proteins between protocols.

Table 1.

Number of unique peptides and proteins identified from fresh frozen and FFPE tissues in 3 independently processed technical replicates with RapiGest and FASP protocols

| Sample | TR | Unique peptides | Total peptides | Unique peptides (%) | Mean | SD | CV (%) | Unique proteins | Total proteins | Unique proteins (%) | Mean | SD | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RapiGest Fresh | 1 | 5573 | 9653 | 57.7 | 56.9 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 536 | 793 | 67.6 | 68.9 | 2.9 | 4.2 |

| 2 | 6148 | 11313 | 54.3 | 575 | 858 | 67.0 | |||||||

| 3 | 6811 | 11610 | 58.7 | 687 | 951 | 72.2 | |||||||

| RapiGest FFPE | 1 | 2866 | 5589 | 51.3 | 54.8 | 3.1 | 5.6 | 411 | 648 | 63.4 | 69.8 | 5.5 | 7.9 |

| 2 | 7972 | 14143 | 56.4 | 779 | 1070 | 72.8 | |||||||

| 3 | 7736 | 13599 | 56.9 | 670 | 916 | 73.1 | |||||||

| FASP Fresh | 1 | 5420 | 10851 | 49.9 | 47.0 | 2.6 | 5.4 | 518 | 776 | 66.8 | 62.1 | 4.2 | 6.7 |

| 2 | 3752 | 8180 | 45.9 | 390 | 642 | 60.7 | |||||||

| 3 | 3841 | 8492 | 45.2 | 385 | 655 | 58.8 | |||||||

| FASP FFPE | 1 | 4611 | 9845 | 46.8 | 47.9 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 413 | 652 | 63.3 | 61.8 | 3.7 | 6.1 |

| 2 | 5016 | 10206 | 49.1 | 482 | 747 | 64.5 | |||||||

| 3 | 1702 | 3559 | 47.8 | 191 | 332 | 57.5 | |||||||

5. Technical reproducibility of the RapiGest and FASP protocols

To evaluate technical reproducibility of both digestion protocols on fresh frozen and FFPE tissues, respectively, independently prepared pool samples (3 technical replicates per protocol and tissue type) were run on SYNAPT G2-Si using UDMSE acquisition mode. Protein lists for each technical replicate are given as Supplementary data 3.

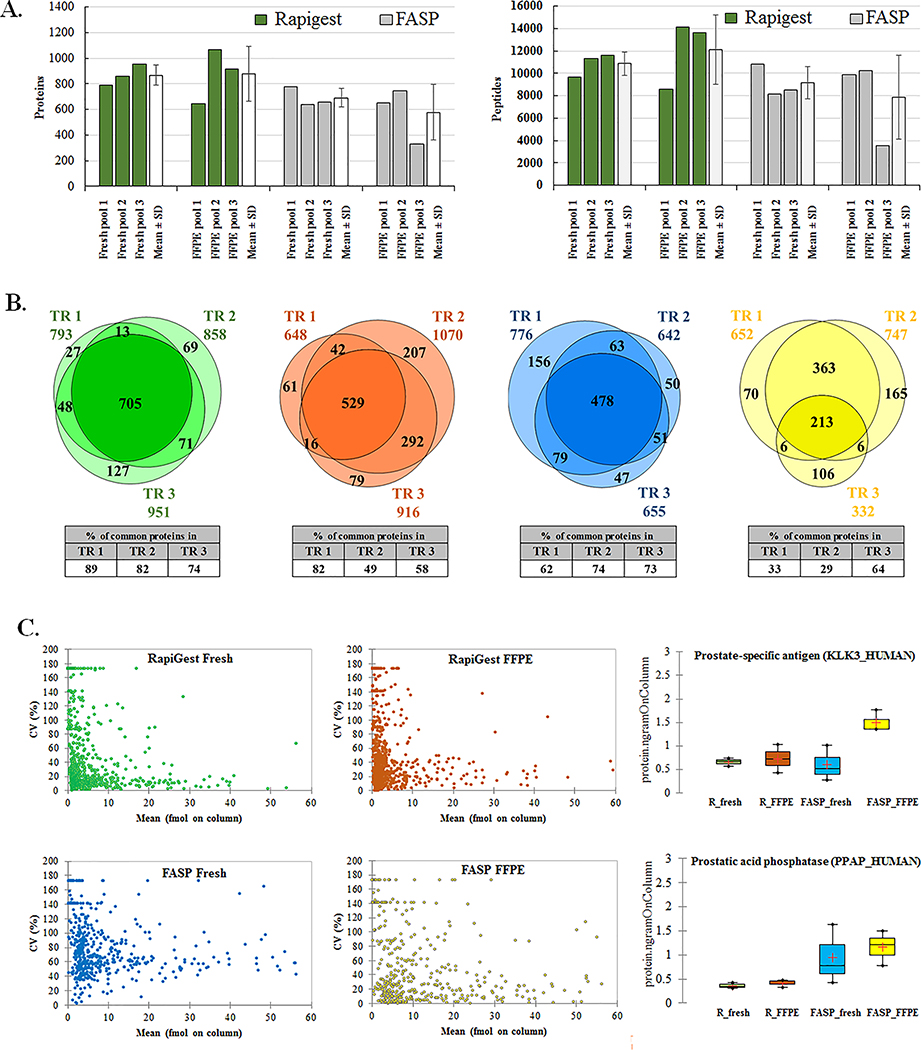

RapiGest protocol showed higher reproducibility than FASP, with average 867±79 proteins (CV=9%) and 10859±1055 peptides (CV=10%) in fresh and 878±214 proteins (CV=24%) and 12222±3061 peptides (CV=25%) in FFPE tissue (Figure 5.A and Supplementary document, Table S2). FASP protocol gave lower average numbers of proteins and peptides (fresh: 691±74 proteins/9174±1460 peptides; FFPE: 577±217 proteins/7870±3738 peptides) and higher CV, ranging from 11–38% for proteins and 16–47% for peptides, for fresh and FFPE respectively. Fresh frozen tissue extraction gave more reproducible results compared to FFPE tissues extraction with both protocols.

Figure 5. Technical reproducibility analysis of RapiGest and FASP protocols.

Pool samples prepared from fresh frozen and FFPE samples and independently extracted in triplicate were run in UDMSE acquisition mode. (A) The number of proteins and peptides are plotted for each replicate with average number of the identified proteins/peptides (Mean ± SD) and CV for each triplicate set. (B) Overlap in protein identifications among independently extracted replicates: RapiGest fresh (green), RapiGest FFPE (orange), FASP fresh (blue), FASP FFPE (yellow). (C) Accuracy of quantification among independently extracted replicates. The mean absolute abundance of the common identified proteins in independently extracted technical replicates is plotted against its corresponding CV (%) for each protocol/tissue type combination. The reproducibility of quantitation is demonstrated for two prostate specific proteins: prostate-specific antigen (KLK3_HUMAN) and prostatic acid phosphatase (PPAP_HUMAN) with absolute quantity of the protein in nanograms (ng) plotted for each technical replicate. In the box plot graphs, median (−), 25th and 75th percentiles and mean (+) are shown.

RapiGest extraction of fresh frozen tissue produced 705 proteins common for all 3 replicates or 89%, 82% and 74% of identified proteins in each technical replicate, while FFPE tissue extraction gave 529 common proteins or 82%, 49% and 58% of proteins identified in each of the 3 replicates (Figure 5.B). On the other hand, FASP showed moderate reproducibility for fresh frozen tissue extraction with 478 common proteins or 62%, 74% and 73% of proteins in separate replicates and lower reproducibility for FFPE tissue extraction with only 213 proteins common or 33%, 29% and 64% from identifications in each of the 3 replicates.

To determine the technical reproducibility of quantitation, protein identifications from individually prepared pool samples in 3 technical replicates per protocol and tissue type were searched for common proteins replicating in at least two out of three technical replicates (Supplementary data 4). The mean absolute abundance of these proteins was plotted against its corresponding coefficient of variation (Figure 5.C). The 70% of quantified proteins from RapiGest/fresh extractions had CV<40%. Proteins with higher CV were mainly ones with mean abundance less than 5 fmols on column. RapiGest/FFPE extractions showed similar distribution but with higher variation (70% of proteins had CV<60%). FASP/fresh extraction had the highest CV with 80% of proteins displaying CV from 30–120%. In addition, the precision of absolute abundance measurements is demonstrated for two prostate specific proteins: Prostate specific antigen (KLK3_HUMAN) and Prostatic acid phosphatase (PPAP_HUMAN) (Figure 5.C and Supplementary document, Table S3). RapiGest showed the highest reproducibility with fresh frozen extraction delivering the lowest CV (CV = 13–17%), followed by FFPE extraction (CV = 21–41%). FASP reproducibility was slightly lower than RapiGest, with fresh frozen extraction delivering higher CV (CV = 62–66%) than FFPE extraction (CV = 16–31%). In terms of absolute abundance estimation values between fresh/frozen and FFPE tissues, RapiGest delivered highly similar values (KLK3: fresh= 0.66±0.09 ng on column; FFPE= 0.73±0.30 ng on column; PPAP: fresh= 0.36±0.06 ng on column; FFPE= 0.42±0.09 ng on column), while with FASP extraction, higher values in FFPE tissues as well as higher range of variations were observed (KLK3: fresh= 0.60±0.37 ng on column; FFPE= 1.50±0.24 ng on column; PPAP: fresh= 0.95±0.62 ng on column; FFPE= 1.16±0.36 ng on column).

DISCUSSION

In the era of personalized medicine development, the vast archive of FFPE samples stored worldwide together with patient metadata represent a valuable resource for biomarker studies. Since the first successful demonstrations that proteomic analysis of FFPE tissues could enable retrospective biomarker investigations [21, 46], a number of protocols for protein extraction and subsequent digestion were reported, each claiming to provide superior qualitative and quantitative analysis of archival clinical samples at the protein level [7–9, 11–14, 17–20, 25–30, 32, 47–49].

The main aim of this study was to give an objective, critical assessment on the performance of the two most common procedures for digestion in shotgun proteomic analysis of FFPE tissue: in-solution digestion method using mass spectrometry compatible detergent for protein extraction and FASP method, widely used as an efficient method for high-throughput processing of protein samples.

As the majority of studies found that the best protein extraction from FFPE tissues, comparable to fresh/frozen extraction, were achieved when the samples were lysed at high temperature in the presence of SDS, we applied the same approach at the start of both tested protocols. We wanted both protocols to start with the same protein extraction efficiency in order to objectively evaluate the overall performance. We found no evidence for reduced protein extraction efficiency from FFPE samples compared with fresh tissue, and this was most likely the result of high concentrations of SDS and DTT in the lysis buffer, which appear to be necessary for good extraction yields. This finding is in agreement with previous reports using similar extraction buffers [19, 50]. Total protein yields from FFPE and frozen blocks were comparable and higher than yields from protocols using Liquid tissue [48], ammonium bicarbonate sonication [49] and RapiGest with DTT in ammonium bicarbonate buffer [27].

Comparison of the overall digestion efficiency between tested protocols showed that RapiGest was superior to FASP in two segments: significantly higher number of protein identifications for both tissue types and almost identical performance for fresh and FFPE tissues, evidenced by matching numbers of protein identifications.

We presume that RapiGest protocol superior efficiency is due to several factors. First, the presence of RapiGest as strong detergent/denaturant in the whole process of sample preparation holds proteins wholly available to reduction, alkylation and trypsin digestion. The use of RapiGest aqueous buffer in sample preparation for shotgun proteomics has been reported to increase in peptide and protein identifications compared to other buffers alone or buffers with other acid-cleavable detergents [51, 52]. This superiority has been attributed to improved protein solubility and proteolytic efficiency of trypsin. With FASP protocol on the other hand, although reduction and alkylation are done in the presence of detergent and denaturant, respectively, trypsin digestion is performed in ammonium bicarbonate buffer alone. Second, RapiGest is compatible with trypsin digestion and as acid-cleavable detergent takes off the need for detergent cleanup step and associated sample loss thereof. In contrast, FASP procedure includes several detergent and urea cleanup steps that likely introduce sample loss and lead to subsequent lower number of peptide and protein identifications. Third, the use of spin filters has been associated with variable digestion efficiencies and peptide recoveries, probably owing to binding of proteins and peptides to the spin filters [53]. Although FASP is reported to be usable for small sample amounts as little as 500 laser micro dissected cells [25, 54], several studies consider it not suitable for analysis of small tissue samples [52, 55, 56]. Considerable limitations of this protocol has been reported by Liebler & Ham [56] when protein samples <50 μg were analyzed. But, Liebler & Ham have only compared two starting protein amounts (50 μg and 150 ng) and the observed loss of 44% protein identifications was made by 333.33 fold lowering of the stating protein amount. Our starting protein amount for digestion was 30 μg and it was only 1.67 fold lower than the maximum tested amount by Liebler & Ham. In another study where direct trypsinization, FASP and in-solution digestion method were compared [24], even lower starting protein amount of 20 μg was used. Therefore, we consider that the starting protein amount used in our study has not contributed significantly towards this FASP limitation.

Numbers of peptides and proteins identified in FFPE samples with RapiGest protocol were quite comparable to fresh/frozen extraction. This observation is in line with other studies that used RapiGest in extraction buffer and reported successful protein extraction and identifications in FFPE samples comparable to matched fresh frozen samples [27, 48]. FASP, on the other hand, delivered lower number of peptide and protein identifications in FFPE samples compared with fresh/frozen. Up to our knowledge, we could compare these findings with only one published study that critically compares FASP 30k processing of FFPE and fresh/frozen samples [19]. Here, despite extensive fractionation, lower number of proteins were identified in FFPE compared to fresh/frozen samples, although to smaller extend compared to this study.

The percentage of overlap between frozen and FFPE protein identifications were quite comparable between protocols with over 69% overlap for RapiGest and 64–69% for FASP, depending on the MS acquisition mode used. This overlap is higher than published results with similar workflow and search parameters [27, 48]. There are studies [19, 49] with even greater overlap reported, greater than 90%, but this is exclusively linked to extensive fractionation, which was not used in our study.

Next, by analyzing several physicochemical features, post-translational modifications, unique peptides and correlation between absolute quantitation values of the extracted proteins from fresh/frozen and FFPE samples, we wanted to investigate to what extent the tested protocols succeeded in the reversal of protein changes induced by FFPE procedure. It is well recognized that formalin fixation causes complex network of inter- and intramolecular crosslinks where each protein forms a number of bonds proportional to the amount of its formaldehyde-reactive residues [7, 8]. Because of this, it has been reported that high-MW and basic proteins are the most difficult to extract, separate and identify within an FFPE tissue proteome [57]. To a small extent, we observed some difficulty with the RapiGest protocol and high molecular weight proteins. In the 100–150 kDa range, there were ~20% fewer proteins identified in FFPE compared with fresh tissue. This was more pronounced with the FASP protocol, especially in the range >70kDa where up to 40% fewer proteins were identified in FFPE compared to fresh tissue. The poorer performance of FASP protocol with the high-MW proteins in FFPE tissue over an in-solution digestion protocol (ISD) has been independently observed in another study [24], where ISD outperformed FASP in the range >70kDa. On the other hand, data concerning protein pI showed that RapiGest protocol extracted proteins from fresh and FFPE tissues with the same efficiency, regardless of pI. FASP protocol was less efficient in acidic and neutral ranges but with almost identical performance in basic regions (pI>10) for fresh and FFPE.

Preliminary analysis of FFPE extracts obtained with both protocols showed proteins from all subcellular compartments, including membrane proteins, with no protocol preferential towards specific cell compartments. Both protocols also demonstrated high positive correlation between the absolute abundance estimation values in the representative proteome from fresh frozen and FFPE samples. These findings are in concordance with previous studies using either FASP [19] or RapiGest [27], reporting that proteins from all subcellular compartments are present in FFPE extract and that these have comparable quantitative accuracy to proteins extracted from fresh/frozen material.

Analysis of post-translational modifications which could be linked to the chemistry of formalin fixation in our dataset revealed significant increase of methylation and formylation of lysine at N-term and slight but not significant increase in hydroxylations on mainly basic amino acids such as asparagine, aspartic acid, proline or lysine in FFPE tissues. Lysine methylation is one of the most abundant variable modifications resulting from formaldehyde crosslinking, already recognized by a number of studies [49, 58, 59]. On the other hand, formylation of lysine has been found both with no difference [45] and with significant increase in FFPE tissues [46], although compared with that study, we found a lower percentage of peptides containing formylated lysine which might result from more efficient de-crosslinking in our study. In addition, we observed slightly higher number of methionine oxidations in FFPE samples, which is consistent with other published studies [45, 46, 49, 58, 59]. But, in our dataset, the difference between fresh and FFPE samples did not reach statistical significance, in line with previous observations [46], suggesting that formalin fixation and storage do not result in an excessive degree of oxidation.

Beside arginine, lysine is a C-terminal cleavage site of trypsin. However, as primary amines of lysine side chains are mainly involved in protein-protein cross-links caused by formaldehyde, trypsin should not cleave at these modified lysine residues, leading to a lower ratio of peptides with a C-terminal lysine versus C-terminal arginine in FFPE compared to fresh tissues [46]. We found significant reduction of the ratio of C-terminal lysine versus arginine peptides in FFPE tissues confirmed with both protocols. Previous studies have come to similar conclusions [45, 46, 49], although there are studies that did not find significant underrepresentation of lysine C-terminal peptides in FFPE tissue tryptic digests [19].

However, despite the significant differences in some of the post-translational modifications linked to formalin fixation and storage of FFPE materials, as well as reduction of C-terminal lysine peptides, we did not find significant difference between the numbers of unique peptides/proteins obtained from FFPE and fresh tissues, with both protocols. This suggests that both protocols extract highly similar proteomic information from both FFPE and fresh material, despite the negative impact of FFPE processing as previously observed [46].

Technical reproducibility accessed from the 3 independently prepared extracts per protocol showed that RapiGest is more reproducible in the number of identified proteins per replicate and gave higher percentage of common proteins among the technical replicates. RapiGest FFPE tissue extraction showed preservation of 49 – 82% of proteins identified in each of the 3 replicates which is considered highly reproducible qualitative metrics at the protein level. These data are consistent with a published study that used RapiGest method for FFPE analysis [14]. On the other hand, FASP FFPE tissue extraction showed lower reproducibility with 29 – 64% of common proteins in each of the 3 replicates. Although we could not compare this aspect directly with another published study based on the same protocols in FFPE analysis, FASP protocol was demonstrated to have lower technical reproducibility than in-solution digestion protocol [24]. The technical reproducibility of quantitation was higher with RapiGest than FASP. However, when quantifying proteins over 10 fmols on column, demonstrated for two highly abundant prostate-specific proteins, comparable values between fresh and FFPE samples were observed with high levels of reproducibility for RapiGest and slightly lower for FASP. To our knowledge, this is the first study that objectively compares this very important characteristic of a protocol, especially if it is intended to be used as part of a biomarker pipeline.

An important aspect of this study is that the FFPE tissues were “real” archival, diagnostic FFPE samples, instead of the experimental FFPE models used in many of the reported studies comparing FFPE with fresh/frozen material [11, 19, 47, 48]. Moreover, our material had a considerable storage period of 7 years. In agreement with few published reports that analyzed archival FFPE samples in storage for up to 10 years [49, 58], we independently validated the finding that high quality proteomic analysis is possible even after a prolonged period.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we tried to critically compare two methods for extraction and digestion of proteins from FFPE tissue samples stored in blocks for 7 years. Our results demonstrate unambiguously that the in-solution digestion method sequentially using two detergents (SDS and RapiGest) in FFPE tissue extraction gives a greater number of protein identifications, higher technical reproducibility, and a more representative proteome (more similar to that obtained from fresh frozen tissue) than does the FASP method. This comparison is not a comprehensive evaluation of all protocols for digestion of proteins from FFPE, but it is a detailed evaluation of the most common approaches for analyzing the FFPE proteome. In this context, more studies like this are needed using different proteomics platforms, before establishing the most effective protocol for shotgun proteomic analysis of FFPE tissue samples. Critical to such studies, in addition to qualitative and quantitative comparisons with fresh tissue, is the more detailed examination of a protocol’s technical reproducibility which is of great importance for large-scale biomarker discovery experiments.

Supplementary Material

• Supplementary data 1: List of identified proteins in representative pools (S POOL) from fresh and FFPE tissues with RapiGest and FASP protocol in MSE and UDMSE acquisition modes

• Supplementary data 2: List of common identified proteins in triplicate runs of representative pools (S POOL) from fresh and FFPE tissues with RapiGest and FASP protocol in MSE and UDMSE acquisition modes

• Supplementary data 3: List of identified proteins in independently extracted technical replicates from fresh and FFPE tissues with RapiGest and FASP protocol

• Supplementary data 4. List of common identified proteins in independently extracted technical replicates from fresh and FFPE tissues with Rapigest and FASP

• Supplementary document 1: Figure S1: Study design; Figure S2: Determination of the optimal on-column sample load; Figure S3: Protein overlap between replicates from fresh-frozen and FFPE samples extracted by RapiGest and FASP protocol; Figure S4: Identified common and unique quantifiable proteins between fresh and FFPE tissues; Figure S5: Protein pI distribution in fresh/frozen and FFPE tissue proteomes extracted by RapiGest and FASP protocols; Table S1: Protein and peptide identifications from fresh frozen and FFPE samples by RapiGest and FASP protocol; Table S2: Technical reproducibility analysis of RapiGest and FASP protocols; Table S3: Reproducibility of quantitation in independently extracted technical replicates with RapiGest and FASP protocols

Significance.

Here we analyzed the performance of two sample preparation methods for shotgun proteomic analysis of FFPE tissues to give a comprehensive overview of the obtained proteomes and the resemblance to its matching fresh frozen counterparts. These findings give us better understanding towards competent proteomics analysis of FFPE tissues. It is hoped that it will encourage further assessments of available protocols before establishing the most effective protocol for shotgun proteomic FFPE analysis.

Two methods for shotgun proteomic analysis of FFPE tissues compared.

Rapigest method gave highly similar number of proteins from fresh and FFPE tissues.

FASP yielded 20% less protein identifications in FFPE than in fresh tissue.

Rapigest showed greater technical reproducibility than FASP.

Both protocols showed high positive correlation between fresh and FFPE proteins.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Katerina Kubelka-Sabit and Dr Vanja Filipovski from Clinical Hospital Acibadem Sistina, Skopje, for providing the fresh and FFPE tissues used in this study. The authors are grateful to Lewis M. Brown (Columbia University, NY, USA) for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable comments. This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and the Fogarty International Center [Research Grant R01 MH098786].

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADH

alcohol dehydrogenase

- BPH

benign prostatic hyperplasia

- CE

collision energy

- FASP

filter-aided sample preparation

- FDR

false discovery rate

- FFPE

formalin fixed and paraffin embedded

- GO

gene ontology

- HE

high energy

- HIAR

heat-induced antigen retrieval

- IAA

iodoacetamide

- IMS

ion-mobility separation

- ISD

in-solution digestion

- LE

low energy

- PLGS

ProteinLynx Global Server

- RMS

root mean square

- TURP

trans urethral resection of the prostate gland

- UDMSE

ultradefinition MSE

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belczacka I, Latosinska A, Metzger J, Marx D, Vlahou A, Mischak H,Frantzi M, Proteomics biomarkers for solid tumors: Current status and future prospects, Mass Spectrom Rev 38 (2019) 49–78, 10.1002/mas.21572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang B, Whiteaker JR, Hoofnagle AN, Baird GS, Rodland KD,Paulovich AG, Clinical potential of mass spectrometry-based proteogenomics, Nat Rev Clin Oncol 16 (2019) 256–268, 10.1038/s41571-018-0135-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blonder J,Veenstra TD, Clinical proteomic applications of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues, Clin Lab Med 29 (2009) 101–13, 10.1016/j.cll.2009.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reimel BA, Pan S, May DH, Shaffer SA, Goodlett DR, McIntosh MW, Yerian LM, Bronner MP, Chen R,Brentnall TA, Proteomics on Fixed Tissue Specimens - A Review, Curr Proteomics 6 (2009) 63–69, 10.2174/157016409787847420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Specht K, Richter T, Muller U, Walch A, Werner M,Hofler H, Quantitative gene expression analysis in microdissected archival formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tumor tissue, Am J Pathol 158 (2001) 419–29, https://doi.org/S0002-9440(10)63985-5 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Weizsacker F, Labeit S, Koch HK, Oehlert W, Gerok W,Blum HE, A simple and rapid method for the detection of RNA in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues by PCR amplification, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 174 (1991) 176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metz B, Kersten GF, Hoogerhout P, Brugghe HF, Timmermans HA, de Jong A, Meiring H, ten Hove J, Hennink WE, Crommelin DJ,Jiskoot W, Identification of formaldehyde-induced modifications in proteins: reactions with model peptides, J Biol Chem 279 (2004) 6235–43, 10.1074/jbc.M310752200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toews J, Rogalski JC, Clark TJ,Kast J, Mass spectrometric identification of formaldehyde-induced peptide modifications under in vivo protein cross-linking conditions, Anal Chim Acta 618 (2008) 168–83, 10.1016/j.aca.2008.04.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi SR, Key ME,Kalra KL, Antigen retrieval in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues: an enhancement method for immunohistochemical staining based on microwave oven heating of tissue sections, J Histochem Cytochem 39 (1991) 741–8, 10.1177/39.6.1709656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gustafsson OJ, Arentz G,Hoffmann P, Proteomic developments in the analysis of formalin-fixed tissue, Biochim Biophys Acta 1854 (2015) 559–80, 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Addis MF, Tanca A, Pagnozzi D, Crobu S, Fanciulli G, Cossu-Rocca P,Uzzau S, Generation of high-quality protein extracts from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues, Proteomics 9 (2009) 3815–23, 10.1002/pmic.200800971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker KF, Schott C, Hipp S, Metzger V, Porschewski P, Beck R, Nahrig J, Becker I,Hofler H, Quantitative protein analysis from formalin-fixed tissues: implications for translational clinical research and nanoscale molecular diagnosis, J Pathol 211 (2007) 370–8, 10.1002/path.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowler CB, Waybright TJ, Veenstra TD, O’Leary TJ,Mason JT, Pressure-assisted protein extraction: a novel method for recovering proteins from archival tissue for proteomic analysis, J Proteome Res 11 (2012) 2602–8, 10.1021/pr201005t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nirmalan NJ, Harnden P, Selby PJ,Banks RE, Development and validation of a novel protein extraction methodology for quantitation of protein expression in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues using western blotting, J Pathol 217 (2009) 497–506, 10.1002/path.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellet V, Boissiere F, Bibeau F, Desmetz C, Berthe ML, Rochaix P, Maudelonde T, Mange A,Solassol J, Proteomic analysis of RCL2 paraffin-embedded tissues, J Cell Mol Med 12 (2008) 2027–36, 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00186.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davalieva K, Kiprijanovska S,Polenakovic M, Assessment of the 2-d gel-based proteomics application of clinically archived formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissues, Protein J 33 (2014) 135–42, 10.1007/s10930-014-9545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda K, Monden T, Kanoh T, Tsujie M, Izawa H, Haba A, Ohnishi T, Sekimoto M, Tomita N, Shiozaki H,Monden M, Extraction and analysis of diagnostically useful proteins from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections, J Histochem Cytochem 46 (1998) 397–403, 10.1177/002215549804600314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craven RA, Cairns DA, Zougman A, Harnden P, Selby PJ,Banks RE, Proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded renal tissue samples by label-free MS: assessment of overall technical variability and the impact of block age, Proteomics Clin Appl 7 (2013) 273–82, 10.1002/prca.201200065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ostasiewicz P, Zielinska DF, Mann M,Wisniewski JR, Proteome, phosphoproteome, and N-glycoproteome are quantitatively preserved in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue and analyzable by high-resolution mass spectrometry, J Proteome Res 9 (2010) 3688–700, 10.1021/pr100234w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wisniewski JR, Dus K,Mann M, Proteomic workflow for analysis of archival formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded clinical samples to a depth of 10 000 proteins, Proteomics Clin Appl 7 (2013) 225–33, 10.1002/prca.201200046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer-Toy DE, Krastins B, Sarracino DA, Nadol JB Jr.,Merchant SN, Efficient method for the proteomic analysis of fixed and embedded tissues, J Proteome Res 4 (2005) 2404–11, 10.1021/pr050208p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balgley BM, Guo T, Zhao K, Fang X, Tavassoli FA,Lee CS, Evaluation of archival time on shotgun proteomics of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues, J Proteome Res 8 (2009) 917–25, 10.1021/pr800503u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao Z, Li G, Chen Y, Li M, Peng F, Li C, Li F, Yu Y, Ouyang Y,Chen Z, Quantitative proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded nasopharyngeal carcinoma using iTRAQ labeling, two-dimensional liquid chromatography, and tandem mass spectrometry, J Histochem Cytochem 58 (2010) 517–27, 10.1369/jhc.2010.955526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanca A, Abbondio M, Pisanu S, Pagnozzi D, Uzzau S,Addis MF, Critical comparison of sample preparation strategies for shotgun proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples: insights from liver tissue, Clin Proteomics 11 (2014) 28, 10.1186/1559-0275-11-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wisniewski JR, Ostasiewicz P,Mann M, High recovery FASP applied to the proteomic analysis of microdissected formalin fixed paraffin embedded cancer tissues retrieves known colon cancer markers, J Proteome Res 10 (2011) 3040–9, 10.1021/pr200019m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang SI, Thumar J, Lundgren DH, Rezaul K, Mayya V, Wu L, Eng J, Wright ME,Han DK, Direct cancer tissue proteomics: a method to identify candidate cancer biomarkers from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded archival tissues, Oncogene 26 (2007) 65–76, https://doi.org/1209755 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nirmalan NJ, Hughes C, Peng J, McKenna T, Langridge J, Cairns DA, Harnden P, Selby PJ,Banks RE, Initial development and validation of a novel extraction method for quantitative mining of the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue proteome for biomarker investigations, J Proteome Res 10 (2011) 896–906, 10.1021/pr100812d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gamez-Pozo A, Sanchez-Navarro I, Calvo E, Diaz E, Miguel-Martin M, Lopez R, Agullo T, Camafeita E, Espinosa E, Lopez JA, Nistal M,Vara JA, Protein phosphorylation analysis in archival clinical cancer samples by shotgun and targeted proteomics approaches, Mol Biosyst 7 (2011) 2368–74, 10.1039/c1mb05113j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian Y, Gurley K, Meany DL, Kemp CJ,Zhang H, N-linked glycoproteomic analysis of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues, J Proteome Res 8 (2009) 1657–62, 10.1021/pr800952h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wakabayashi M, Yoshihara H, Masuda T, Tsukahara M, Sugiyama N,Ishihama Y, Phosphoproteome analysis of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections mounted on microscope slides, J Proteome Res 13 (2014) 915–24, 10.1021/pr400960r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foll MC, Fahrner M, Oria VO, Kuhs M, Biniossek ML, Werner M, Bronsert P,Schilling O, Reproducible proteomics sample preparation for single FFPE tissue slices using acid-labile surfactant and direct trypsinization, Clin Proteomics 15 (2018) 11, 10.1186/s12014-018-9188-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy JJ, Whiteaker JR, Schoenherr RM, Yan P, Allison K, Shipley M, Lerch M, Hoofnagle AN, Baird GS,Paulovich AG, Optimized Protocol for Quantitative Multiple Reaction Monitoring-Based Proteomic Analysis of Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Tissues, J Proteome Res 15 (2016) 2717–28, 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oswald ES, Brown LM, Bulinski JC,Hung CT, Label-free protein profiling of adipose-derived human stem cells under hyperosmotic treatment, J Proteome Res 10 (2011) 3050–9, 10.1021/pr200030v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva JC, Denny R, Dorschel CA, Gorenstein M, Kass IJ, Li GZ, McKenna T, Nold MJ, Richardson K, Young P,Geromanos S, Quantitative proteomic analysis by accurate mass retention time pairs, Anal Chem 77 (2005) 2187–200, 10.1021/ac048455k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu YQ, Gilar M, Lee PJ, Bouvier ES,Gebler JC, Enzyme-friendly, mass spectrometry-compatible surfactant for in-solution enzymatic digestion of proteins, Anal Chem 75 (2003) 6023–8, 10.1021/ac0346196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potriquet J, Laohaviroj M, Bethony JM,Mulvenna J, A modified FASP protocol for high-throughput preparation of protein samples for mass spectrometry, PloS one 12 (2017) e0175967, 10.1371/journal.pone.0175967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wisniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N,Mann M, Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis, Nat Methods 6 (2009) 359–62, 10.1038/nmeth.1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradford MM, A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding, Anal Biochem 72 (1976) 248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Distler U, Kuharev J, Navarro P, Levin Y, Schild H,Tenzer S, Drift time-specific collision energies enable deep-coverage data-independent acquisition proteomics, Nat Methods 11 (2014) 167–70, 10.1038/nmeth.2767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva JC, Gorenstein MV, Li GZ, Vissers JP,Geromanos SJ, Absolute quantification of proteins by LCMSE: a virtue of parallel MS acquisition, Mol Cell Proteomics 5 (2006) 144–56, https://doi.org/M500230-MCP200 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Distler U, Kuharev J, Navarro P,Tenzer S, Label-free quantification in ion mobility-enhanced data-independent acquisition proteomics, Nat Protoc 11 (2016) 795–812, 10.1038/nprot.2016.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perez-Riverol Y, Csordas A, Bai J, Bernal-Llinares M, Hewapathirana S, Kundu DJ, Inuganti A, Griss J, Mayer G, Eisenacher M, Perez E, Uszkoreit J, Pfeuffer J, Sachsenberg T, Yilmaz S, Tiwary S, Cox J, Audain E, Walzer M, Jarnuczak AF, Ternent T, Brazma A,Vizcaino JA, The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: improving support for quantification data, Nucleic acids research 47 (2019) D442–D450, 10.1093/nar/gky1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pomaznoy M, Ha B,Peters B, GOnet: a tool for interactive Gene Ontology analysis, BMC Bioinformatics 19 (2018) 470, 10.1186/s12859-018-2533-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaeffer M, Gateau A, Teixeira D, Michel PA, Zahn-Zabal M,Lane L, The neXtProt peptide uniqueness checker: a tool for the proteomics community, Bioinformatics 33 (2017) 3471–3472, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Broeckx V, Boonen K, Pringels L, Sagaert X, Prenen H, Landuyt B, Schoofs L,Maes E, Comparison of multiple protein extraction buffers for GeLC-MS/MS proteomic analysis of liver and colon formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues, Mol Biosyst 12 (2016) 553–65, 10.1039/c5mb00670h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hood BL, Darfler MM, Guiel TG, Furusato B, Lucas DA, Ringeisen BR, Sesterhenn IA, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD,Krizman DB, Proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed prostate cancer tissue, Mol Cell Proteomics 4 (2005) 1741–53, https://doi.org/M500102-MCP200 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang X, Feng S, Tian R, Ye M,Zou H, Development of efficient protein extraction methods for shotgun proteome analysis of formalin-fixed tissues, J Proteome Res 6 (2007) 1038–47, 10.1021/pr0605318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scicchitano MS, Dalmas DA, Boyce RW, Thomas HC,Frazier KS, Protein extraction of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue enables robust proteomic profiles by mass spectrometry, J Histochem Cytochem 57 (2009) 849–60, 10.1369/jhc.2009.953497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sprung RW Jr., Brock JW, Tanksley JP, Li M, Washington MK, Slebos RJ,Liebler DC, Equivalence of protein inventories obtained from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded and frozen tissue in multidimensional liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry shotgun proteomic analysis, Mol Cell Proteomics 8 (2009) 1988–98, 10.1074/mcp.M800518-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bronsert P, Weisser J, Biniossek ML, Kuehs M, Mayer B, Drendel V, Timme S, Shahinian H, Kusters S, Wellner UF, Lassmann S, Werner M,Schilling O, Impact of routinely employed procedures for tissue processing on the proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue, Proteomics Clin Appl 8 (2014) 796–804, 10.1002/prca.201300082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen EI, Cociorva D, Norris JL,Yates JR 3rd, Optimization of mass spectrometry-compatible surfactants for shotgun proteomics, J Proteome Res 6 (2007) 2529–38, 10.1021/pr060682a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Longuespee R, Alberts D, Pottier C, Smargiasso N, Mazzucchelli G, Baiwir D, Kriegsmann M, Herfs M, Kriegsmann J, Delvenne P,De Pauw E, A laser microdissection-based workflow for FFPE tissue microproteomics: Important considerations for small sample processing, Methods 104 (2016) 154–62, 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eggler AL, Luo Y, van Breemen RB,Mesecar AD, Identification of the highly reactive cysteine 151 in the chemopreventive agent-sensor Keap1 protein is method-dependent, Chem Res Toxicol 20 (2007) 1878–84, 10.1021/tx700217c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wisniewski JR, Dus-Szachniewicz K, Ostasiewicz P, Ziolkowski P, Rakus D,Mann M, Absolute Proteome Analysis of Colorectal Mucosa, Adenoma, and Cancer Reveals Drastic Changes in Fatty Acid Metabolism and Plasma Membrane Transporters, J Proteome Res 14 (2015) 4005–18, 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drummond ES, Nayak S, Ueberheide B,Wisniewski T, Proteomic analysis of neurons microdissected from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue, Sci Rep 5 (2015) 15456, 10.1038/srep15456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liebler DC,Ham AJ, Spin filter-based sample preparation for shotgun proteomics, Nat Methods 6 (2009) 785; author reply 785–6, 10.1038/nmeth1109-785a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanca A, Pagnozzi D, Burrai GP, Polinas M, Uzzau S, Antuofermo E,Addis MF, Comparability of differential proteomics data generated from paired archival fresh-frozen and formalin-fixed samples by GeLC-MS/MS and spectral counting, J Proteomics 77 (2012) 561–76, 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coscia F, Doll S, Bech JM, Schweizer L, Mund A, Lengyel E, Lindebjerg J, Madsen GI, Moreira JM,Mann M, A streamlined mass spectrometry-based proteomics workflow for large-scale FFPE tissue analysis, J Pathol 251 (2020) 100–112, 10.1002/path.5420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Y, Muller M, Xu B, Yoshida Y, Horlacher O, Nikitin F, Garessus S, Magdeldin S, Kinoshita N, Fujinaka H, Yaoita E, Hasegawa M, Lisacek F,Yamamoto T, Unrestricted modification search reveals lysine methylation as major modification induced by tissue formalin fixation and paraffin embedding, Proteomics 15 (2015) 2568–79, 10.1002/pmic.201400454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data