Abstract

Background

Systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) has been reported to be an effective blood-based biomarker for predicting prognosis in various kinds of cancer patients. However, the prognostic role of SIRI in advanced lung adenocarcinoma patient remains unclear.

Methods

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the prognostic role of SIRI in EGFR-mutant advanced lung adenocarcinoma patients treated with first-generation EGFR-TKIs. A total of 245 patients who received gefitinib, erlotinib, or icotinib at the Second Xiangya Hospital were retrospectively evaluated. SIRI was defined as neutrophil count×monocyte/lymphocyte count. The optimal cut-off value was determined according to receiver operation characteristic curve analysis. Characteristics of patients were compared via chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Survivals were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the Log rank test. Multivariate analysis was estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

It is showed that high SIRI was associated with male patient, smoker, worse ECOG PS, 19-DEL mutation. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that ECOG PS, brain metastasis, SIRI were significantly correlated with progression-free survival (PFS), and gender, ECOG PS, brain metastasis, NLR and SIRI were significantly correlated with overall survival (OS). Multivariate analysis showed that SIRI and ECOG PS independently predict PFS and OS.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that SIRI is an effective and convenient marker for predicting prognosis in advanced EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma patients treated with first-generation TKI.

Keywords: lung adenocarcinoma, EGFR-TKI, SIRI, prognosis

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of mortality both in China and worldwide, among which non-small cell lung cancer consists of more than 80% of the patients.1 In China, more than half of the patients are diagnosed at advanced stage, and the prognosis is poor. Based on serials of clinical trials, epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) have been established as the optimal choice of advanced NSCLC patients harboring EGFR active mutations.2–4 However, nearly all the patients will inevitably suffer from drug resistance which cause treatment failure. Therefore, exploring biomarkers to predict patients’ prognosis and facilitate patient stratification is urgently needed in clinical practice.

Tumor promotion inflammation is a hall mark of cancer.5 Local and systemic inflammation significantly effects tumor progression and its response to therapy. There is increasing evidence showing that inflammation indexes could be used to predict the prognosis of cancer patients. The immune and inflammatory cells, including neutrophile, monocyte, lymphocyte, and platelet, which can be detected in circulation blood may contribute to cancer invasion and metastasis.6 And anti-inflammation intervention is a promising strategy to further improve the effectiveness of anti-tumor treatment.7 Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) are widely studied markers which are proven to be effective in predicting patients’ survival in various kinds of cancer patients.8–11 The systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) is defined as neutrophil count×monocyte/lymphocyte count, which can better reflect the host immune and inflammation balance. It has been reported that SIRI could predict survival in various kinds of cancers, including pancreatic cancer,12 gallbladder cancer,13 oral squamous cell carcinoma,14 and cervical cancer.15 The report on the prognostic role of SIRI in lung cancer is rare. Liu et al reported that higher preoperative SIRI could predict poorer survival in surgically resected NSCLC.16 However, the prognostic role of SIRI in advanced stage NSCLC patients remain to be elucidated.

In the present study, a cohort of 245 EGFR-mutant advanced lung adenocarcinoma patients were retrospectively analyzed to evaluate the clinical significance and prognostic value of NLR, PLR, and SIRI in NSCLC patients receiving first-generation EGFR-TKIs treatment.

Patients and Methods

Patient Selection

We retrospectively enrolled 245 lung adenocarcinoma patient who received first-generation EGFR-TKI as first-line treatment from January 2017 to June 2019 at the Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China. All the clinical data were obtained from electronic medical record system. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) pathologically diagnosed lung adenocarcinoma; (2) harboring EGFR active mutation; (3) suffering relapsed or metastasized disease (stage IV according to AJCC/UICC staging system; (4) using first-generation EGFR-TKI (gefitinib, erlotinib, or icotinib) as the first-line treatment; (5) with complete record of blood test results within 1 week prior to the initiation of EGFR-TKI treatment and follow-up data. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of other malignant tumors and chronic inflammatory diseases (for example: inflammatory bowel disease); (2) steroid therapy within 2 weeks before the initiation of EGFR-TKI treatment; (3) with recent clinical evidence of acute infection or inflammation; (4) Antiangiogenic drugs (avastin) and/or chemotherapy drugs were used accompanied with EGFR-TKI during the first-line treatment. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University. Written consent was waivered due to the retrospective natural of the study, and patient data confidentiality rules are in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Collection and Follow-Up

Patient clinicopathological characteristics including gender, age, smoking history, brain metastasis status, ECOG score, EGFR mutation status, and full blood counts within 1 week of the initiation of EGFR-TKI treatment were obtained from the electronic medical record system of the Second Xiangya Hospital. The SIRI, NLR, and PLR were calculated as follows: SIRI = neutrophil count×monocyte/lymphocyte count, NLR = neutrophil counts/lymphocyte counts, PLR = platelet counts/lymphocyte counts. The patient was followed up by outpatient examination or telephone interview at about every 2 months. The last follow-up date was April 30, 2020. The overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval between the date of first day of EGFR-TKI administration and the date of death for any reason or to the last date of follow-up. The progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the interval between the date of first day of EGFR-TKI administration and the date of disease progression based on response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) 1.1, or death.

Statistical Analysis

The relationship between SIRI, NLR, and PLR and clinicopathological factors were analyzed using the chi-square test. The optimal cut-off value for SIRI, NLR, and PLR was determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves analysis using the highest Youden index, defined as sensitivity+specificity-1, to predict PFS. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier method. The differences between the survival curves were compared by Log rank test. The multivariate Cox hazard regression analysis was performed on the factors that were shown to be significant on univariate analysis. All tests were 2-sided and P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. The SPSS software 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used.

Results

Patient Characteristics

In the present study, we enrolled 245 patients, and the baseline clinicopathological characteristics were shown in Table 1. There were 107 (43.7%) male patients and 138 (56.3%) female patients. The median age was 60 years (range: 28–88 years). Sixty-nine patients (28.2%) had a smoking history. The majority of patients had an ECOG score of 0 to 1 (204, 83.3%). In all the patients, 101 (41.2%) patients had the exon 21 L858R mutation, 134 (54.7%) the exon 19 deletion mutation, and 10 (4.1%) other rare mutations. There are 26 (10.6%) patients who had brain metastasis, and 10 patients received whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) concurrent with TKI. The median follow-up period was 18.3 months (range 2.2–37.8 months). At the final follow-up, 119 (48.6%) patients had died and 153 (62.4%) patients suffered from disease progression.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological Characteristics of 245 Patients

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median | 60 |

| Range | 28–88 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 107(43.7) |

| Female | 138(56.3) |

| Smoking status | |

| Non-smoker | 176(71.8) |

| Current or ex-smoker | 69(28.2) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0 | 38(15.5) |

| 1 | 166(67.8) |

| 2 | 41(16.7) |

| Brain metastasis | |

| Yes | 26(10.6) |

| No | 219(89.4) |

| EGFR mutation | |

| L858R | 101(41.2) |

| 19-DEL | 134(54.7) |

| Other | 10(4.1) |

| NLR | |

| High | 82(33.5) |

| Low | 163(66.5) |

| PLR | |

| High | 52(21.2) |

| Low | 193(78.8) |

| SIRI | |

| High | 90(36.7) |

| Low | 155(63.3) |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; SIRI, systemic immune response index; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet to lymphocyte ratio.

Relationship Between SIRI, NLR, PLR, and Clinicopathological Characteristics

The optimal cut-off value for SIRI, NLR and PLR were calculated using receiver operation characteristic curve analysis for PFS, and the optimal cut-off value were 0.71, 3.36, and 167.01 respectively, with an area under the curve of 0.577, 0.516, and 0.513 (Figure S1). As shown in Table 2, high SIRI was associated with male patient, smoker, worse ECOG PS, 19-DEL mutation. High NLR was associated with male patient, worse ECOG PS, and 19-DEL mutation. High PLR was associated with worse ECOG PS.

Table 2.

The Association of SIRI, NLR, and PLR with Clinicopathologic Characteristics in 245 Patients with Advanced Lung Adenocarcinoma

| Characteristics | SIRI <0.71 | SIRI ≥0.71 | P | NLR <3.36 | NLR ≥3.36 | P | PLR <167.01 | PLR ≥167.01 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||||

| <65 | 41(16.7%) | 136(55.5%) | 0.606 | 102(41.6%) | 75(30.6%) | 0.251 | 87(35.5%) | 90(36.7%) | 0.669 |

| ≥65 | 13(5.3%) | 55(22.4%) | 33(13.5%) | 35(14.3%) | 36(14.7%) | 32(13.1%) | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 42(17.1%) | 96(39.2%) | <0.001 | 85(34.7%) | 53(21.6%) | 0.028 | 68(27.8%) | 70(28.6%) | 0.797 |

| Male | 12(4.9%) | 95(38.8%) | 50(20.4%) | 57(23.3%) | 55(22.4%) | 52(21.2%) | |||

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| No | 47(19.2%) | 129(52.7%) | 0.006 | 98(40.0%) | 78(31.8%) | 0.777 | 83(33.9%) | 93(38.0%) | 0.156 |

| Yes | 7(2.9%) | 62(25.3%) | 37(15.1%) | 32(13.1%) | 40(16.3%) | 29(11.8%) | |||

| ECOG PS | |||||||||

| 0–1 | 50(20.4%) | 154(62.9%) | 0.039 | 121(49.4%) | 83(33.9%) | 0.004 | 111(45.3%) | 93(38.0%) | 0.004 |

| 2 | 4(1.6%) | 37(15.1%) | 14(5.7%) | 27(11.0%) | 12(4.9%) | 29(11.8%) | |||

| Brain metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 47(19.2%) | 172(70.2%) | 0.616 | 122(49.8%) | 97(39.6%) | 0.678 | 110(44.9%) | 109(44.5%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 7(2.9%) | 19(7.8%) | 13(5.3%) | 13(5.3%) | 13(5.3%) | 13(5.3%) | |||

| EGFR mutation | |||||||||

| 19-DEL | 27(11.0%) | 107(43.7%) | 0.001 | 70(28.6%) | 64(26.1%) | 0.014 | 63(25.7%) | 71(29.0%) | 0.125 |

| L858R | 20(8.2%) | 81(33.1%) | 55(22.4%) | 46(18.8%) | 52(21.2%) | 49(20.0%) | |||

| Other | 7(2.9%) | 3(1.2%) | 10(4.1%) | 0(0%) | 8(3.3%) | 2(0.8%) |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; SIRI, systemic immune response index; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet to lymphocyte ratio.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis for PFS and OS

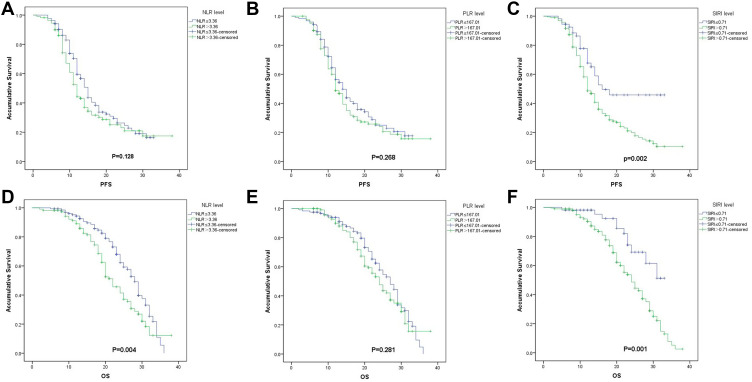

On univariate cox regression analyses, ECOG PS, brain metastasis, and SIRI were associated with PFS (P=0.007, 0.043, 0.002, respectively). And ECOG PS, gender, brain metastasis, NLR and SIRI were associated with OS (P<0.001, 0.010, 0.038, 0.004, and 0.001, respectively). (Table 3, and Figure 1). All other clinicopathological characteristics were not statistically significant. In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, as shown in Table 4, ECOG PS (HR 2.562; 95% CI 1.667–3.940; P<0.001), and SIRI (HR 2.384; 95% CI 1.275–4.459; P<0.007) were independent prognostic factors for PFS. And ECOG PS (HR 2.431; 95% CI 1.571–3.761; P<0.001), and SIRI (HR 1.721; 95% CI 1.024–3.898; P=0.042) were also independent prognostic factors for OS.

Table 3.

Univariate Analysis of Potential Factors Associated with PFS and OS

| Variables | PFS | OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | MST(m) | P | Case | MST(m) | P | |

| Age | ||||||

| <65 | 177 | 14.8(12.7–15.3) | 0.279 | 177 | 25.2(22.5–27.5) | 0.264 |

| ≥65 | 68 | 14.3(11.4–16.6) | 68 | 26.8(22.3–31.7) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 107 | 11.6(10.7–13.3) | 0.057 | 107 | 28.2(25.9–30.1) | 0.010 |

| Female | 138 | 14.4(12.8–15.2) | 138 | 24.1(20.8–27.2) | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| No | 176 | 14.2(12.3–15.7) | 0.052 | 176 | 27.4(23.7–30.3) | 0.084 |

| Yes | 69 | 11.7(10.6–13.4) | 69 | 23.8(22.7–25.3) | ||

| ECOG PS | ||||||

| 0–1 | 204 | 14.4(12.4–15.6) | 0.007 | 204 | 28.3(25.7–30.3) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 41 | 10.7(9.3–12.7) | 41 | 18.6(16.3–21.7) | ||

| Brain metastasis | ||||||

| Yes | 26 | 11.1(9.4–12.6) | 0.043 | 26 | 22.8(19.1–26.9) | 0.038 |

| No | 219 | 14.4(12.4–15.6) | 219 | 26.2(23.7–28.3) | ||

| EGFR mutation | ||||||

| L858R | 101 | 11.9(10.1–13.9) | 0.590 | 101 | 24.1(17.7–30.3) | 0.829 |

| 19-DEL | 134 | 14.4(12.0–16.0) | 134 | 25.6(23.0–27.0) | ||

| Other | 10 | 12.0(NR) | 10 | 25.2(NR) | ||

| NLR | ||||||

| <3.36 | 135 | 14.8(13.6–16.4) | 0.128 | 135 | 27.8(26.1–29.9) | 0.004 |

| ≥3.36 | 110 | 11.7(10.8–13.2) | 110 | 21.7(19.4–24.6) | ||

| PLR | ||||||

| <167.01 | 123 | 14.3(11.7–16.3) | 0.268 | 123 | 26.8(23.5–30.5) | 0.281 |

| ≥167.01 | 122 | 11.8(10.6–13.4) | 122 | 23.9(21.4–26.6) | ||

| SIRI | ||||||

| <0.71 | 54 | 16.4(NR) | 0.002 | 54 | NR | 0.001 |

| ≥0.71 | 191 | 11.6(10.7–13.3) | 191 | 23.8(21.7–26.3) | ||

Abbreviations: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; SIRI, systemic immune response index; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet to lymphocyte ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; MST, mean survival time.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for progression-free survival (PFS) according to NLR (A), PLR (B), and SIRI (C), and overall survival (OS) according to NLR (D), PLR (E) and SIRI (F) in EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma patients treated with first-generation EGFR-TKIs.

Abbreviations: NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet to lymphocyte ratio; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index.

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox Regression Analyses for PFS and OS

| Variables | PFS | OS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| ECOG PS | ||||

| 0–1 | ||||

| 2 | 2.562(1.667–3.940) | <0.001 | 2.431(1.571–3.761) | <0.001 |

| Brain metastasis | ||||

| Yes | 1.630(0.980–2.711) | 0.060 | 1.495(0.886–2.525) | 0.132 |

| No | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.206(0.825–1.761) | 0.333 | ||

| Male | ||||

| NLR | ||||

| ≥3.36 | 1.275 (0.860–1.867) | 0.212 | ||

| <3.36 | ||||

| SIRI | ||||

| ≥0.71 | 2.384(1.275–4.459) | 0.007 | 1.721 (1.024–3.898) | 0.042 |

| <0.71 | ||||

Abbreviations: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; SIRI, systemic immune response index; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Discussion

NSCLC is the most common malignancies worldwide. For patients with EGFR mutation, EGFR-TKIs have been established as the cornerstone of the treatment of advanced stage patients. Serial trials have demonstrated that patients treated with first-generation EGFR-TKIs have longer PFS and quality of life, compared with chemotherapy.17 However, the median PFS of first-line EGFR-TKIs treatment is about 8–12 months, and nearly all the patient will be suffered from drug resistance. The markers with prognostic value in predicting the survival of the patients are lacking. Therefore, it is important to find reliable tumor markers of prognosis and facilitate treatment adjusting and patient stratification. In the present study, we evaluated prognostic effect of blood-based immune-inflammation indexes, including SIRI, NLR and PLR in EGFR-mutant advanced lung adenocarcinoma treated with first-generation EGFR-TKIs. And we found that SIRI and ECOG PS are independent prognostic factors of PFS and OS in advanced lung adenocarcinoma patients.

Inflammation is a hallmark of cancer.5 Local and systemic inflammation is an important promoter of tumorigenesis, tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, and it is also involved in the responsiveness to treatment agents.18,19 Tumor-induced inflammation can lead to peripheral hematological changes, including the changes of neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte and platelet, via the secretion of various kinds of cytokines.20 Neutrophil is an indicator of acute and chronic inflammation, and increasing evidences have shown that it can facilitate tumor cell proliferation, metastasis and evading immune surveillance by inhibiting T cell function, secreting immune suppressive factors including transforming growth factor-β, and inducing angiogenesis.21 Lymphocyte is the major mediator of host anti-tumor immunity, and leucopenia has been proven to be an adverse factor of patient prognosis.22 Monocyte, especially tumor associated macrophages (TAM), which is derived from circulating monocyte, could promote tumor progression by influencing tumor microenvironment.23 Platelet is important mediator of coagulation, and it can promote tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis by secreting growth factors and other cytokines.24 Hence, blood cell counts are easy-to-get and cost-effective indexes to present host immune inflammation statues, and there is increasing evidence showing that blood-based inflammatory markers, including NLR, PLR, and LMR,25–28 could be used as an effective marker in patients’ prognosis in various kinds of tumors.

SIRI is a novel index with a combination of neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte counts, which is firstly reported by Qi et al29 to be an effective prognosis factor in pancreatic cancer patients. Hence, SIRI has been proven to be an effective marker in predicting patients’ survival in various kinds of cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma,30 gastric adenocarcinoma,31 nasopharyngeal carcinoma,32 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma,33 breast cancer,34 and cervical cancer.15 The research on the prognostic effect of SIRI on lung cancer patient is rare. Li et al16 reported that SIRI is an independent prognostic factor in lung cancer patients after thoracoscopic surgery. However, the prognostic role of SIRI in advanced stage lung cancer patient remains unclear. In the present study, we demonstrated that SIRI is an independent prognostic factor of advanced stage EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma patients treated with EGFR-TKIs. However, in the present cohort of patients, only NLR is an independent prognostic factor of OS, while PLR was not a prognostic factor, which is not in accordance with previous studies.35,36 This may due to the different cut-off value and different patient characteristics in different researches. Besides SIRI, we found that ECOG PS was also an independent prognostic factor, and patients with worse ECOG PS are more likely to have high level of NLR, PLR and SIRI, which indicated that systemic inflammation may be a reason of deterioration of general condition and drug resistance.

Although our research, together with previous researches, demonstrated that SIRI is a promising tool for predicting prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma patients, the results of our research should be interpreted with cautious due to the obvious limitation of the research. First, the retrospective nature of the study, the same as that of most previous researches, will inevitably bring bias, such as patient selection bias and follow-up bias, to the results. Second, due to the limited sample size, no validation cohort was established, which impaired the external authenticity of the result.

In summary, SIRI may be a convenient, cost-effective, and reliable marker for predicting prognosis in advanced lung adenocarcinoma patients treated with EGFR-TKIs. And it may help treatment adjustment and patient stratification. However, well-designed prospective trial is needed to further verify the results and the underlying mechanism of systemic inflammation induced EGFR-TKI resistance and early intervention modality worth further investigation.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Chen W, Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S, He J. Annual report on status of cancer in China, 2011. Chin J Cancer Res. 2015;27(1):2–12. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2015.01.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao G, Ren S, Li A, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy is effective as first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR: a meta-analysis from six Phase III randomized controlled trials. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(5):E822–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuler M, Paz-Ares L, Sequist LV, et al. First-line afatinib for advanced EGFRm+ NSCLC: analysis of long-term responders in the LUX-Lung 3, 6, and 7 trials. Lung Cancer. 2019;133:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D, et al. Overall survival with osimertinib in untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):41–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1913662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(11):e493–503. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70263-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Sun Y, Liu X, et al. Efficiency of different treatment regimens combining anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory liposomes for metastatic breast cancer. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2020;21(7):259. doi: 10.1208/s12249-020-01792-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Berckelaer C, Van Geyt M, Linders S, et al. A high neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio are associated with a worse outcome in inflammatory breast cancer. Breast. 2020;53:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2020.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, Ding Y, Li N, et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-lymphocyte ratio, and combined neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio in stage IV advanced gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:841. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng X, Liu G, Pan Y, Li Y. Development and validation of immune inflammation-based index for predicting the clinical outcome in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(15):8326–8349. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cong R, Kong F, Ma J, Li Q, Wu Q, Ma X. Combination of preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-lymphocyte ratio and monocyte-lymphocyte ratio: a superior prognostic factor of endometrial cancer. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):464. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06953-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topkan E, Mertsoylu H, Kucuk A, et al. Low systemic inflammation response index predicts good prognosis in locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:5701949. doi: 10.1155/2020/5701949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun L, Hu W, Liu M, et al. High systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) indicates poor outcome in gallbladder cancer patients with surgical resection: a single institution experience in China. Cancer Res Treat. 2020. doi: 10.4143/crt.2020.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin J, Chen L, Chen Q, et al. Prognostic value of preoperative systemic inflammation response index in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: propensity score-based analysis. Head Neck. 2020;42(11):3263–3274. doi: 10.1002/hed.26375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chao B, Ju X, Zhang L, Xu X, Zhao Y. A novel prognostic marker systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for operable cervical cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2020;10:766. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li S, Yang Z, Du H, Zhang W, Che G, Liu L. Novel systemic inflammation response index to predict prognosis after thoracoscopic lung cancer surgery: a propensity score-matching study. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89(11):E507–E513. doi: 10.1111/ans.15480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Y, Liu J, Cai X, et al. Efficacy and safety of first line treatments for patients with advanced epidermal growth factor receptor mutated, non-small cell lung cancer: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;367:l5460. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elinav E, Nowarski R, Thaiss CA, Hu B, Jin C, Flavell RA. Inflammation-induced cancer: crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(11):759–771. doi: 10.1038/nrc3611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L, Kong X, Wang Z, Wang X, Fang Y, Wang J. Pre-treatment systemic immune-inflammation index is a useful prognostic indicator in patients with breast cancer undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(5):2993–3021. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiffmann LM, Fritsch M, Gebauer F, et al. Tumour-infiltrating neutrophils counteract anti-VEGF therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2019;120(1):69–78. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0198-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun GY, Wang SL, Song YW, et al. Radiation-induced lymphopenia predicts poorer prognosis in patients with breast cancer: a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial of postmastectomy hypofractionated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108(1):277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.02.633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cortese N, Carriero R, Laghi L, Mantovani A, Marchesi F. Prognostic significance of tumor-associated macrophages: past, present and future. Semin Immunol. 2020;48:101408. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2020.101408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zmigrodzka M, Witkowska-Pilaszewicz O, Winnicka A. Platelets extracellular vesicles as regulators of cancer progression-an updated perspective. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(15):5195. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazaki J, Katsumata K, Kasahara K, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a prognostic factor for colon cancer: a propensity score analysis. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):922. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07429-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huh G, Ryu JK, Chun JW, et al. High platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with poor prognosis in patients with unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma receiving gemcitabine plus cisplatin. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):907. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07390-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbeau I, Thezenas S, Maran-Gonzalez A, Colombo PE, Jacot W, Guiu S. Inflammatory blood markers as prognostic and predictive factors in early breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(9):2666. doi: 10.3390/cancers12092666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zager Y, Hoffman A, Dreznik Y, et al. Cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: the prognostic impact of baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte, platelet-lymphocyte and lymphocyte-monocyte ratios. Surg Oncol. 2020;35:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2020.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qi Q, Zhuang L, Shen Y, et al. A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the survival of patients with pancreatic cancer after chemotherapy. Cancer. 2016;122(14):2158–2167. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu L, Yu S, Zhuang L, et al. Systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) predicts prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(21):34954–34960. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li S, Lan X, Gao H, et al. Systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), cancer stem cells and survival of localised gastric adenocarcinoma after curative resection. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143(12):2455–2468. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2506-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Jiang W, Xi D, et al. Development and validation of nomogram based on SIRI for predicting the clinical outcome in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinomas. J Investig Med. 2019;67(3):691–698. doi: 10.1136/jim-2018-000801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geng Y, Zhu D, Wu C, et al. A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting postoperative survival of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;65:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hua X, Long ZQ, Huang X, et al. The preoperative systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) independently predicts survival in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2020;44(4):100560. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2020.100560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun S, Qu Y, Wen F, Yu H. Initial neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic markers in patients with inoperable locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Biomark Med. 2020;14(14):1341–1352. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2019-0583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandaliya H, Jones M, Oldmeadow C, Nordman II. Prognostic biomarkers in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI). Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8(6):886–894. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2019.11.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]