INTRODUCTION

The U.S. response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has entailed challenges related to testing, case management, and community-level mitigation.1 Community spread of the infection continues, and U.S. COVID-19 mortality leads in the world, exceeding 500,000 deaths as of late winter 2021. Sustained prevention and control efforts are urgently needed.

The war on cancer declared in 19712 led to significant investment in new technologies, medicines, and structural resources that have significantly reduced cancer mortality and dramatically increased the number of cancer survivors.3 Although cancer is primarily a chronic condition and COVID-19 is an acute infectious disease, both benefit from multilevel public health strategies directed at the patient, provider, community, healthcare system, and policy formation level. Both cancer and COVID-19 also share a common set of barriers to care related to social determinants of health. Lessons learned from decades of cancer prevention and control can illuminate proven strategies relevant to the current COVID-19 crisis, especially as it moves into the long-term management phase. The impact of these strategies has further been amplified through the rapid integration of research evidence into practice using implementation science approaches that could similarly improve the COVID-19 response.4

HOW CAN THE HISTORICAL RESPONSE IN THE U.S. TO CANCER INFORM THE CURRENT COVID-19 CRISIS?

Both COVID-19 and cancer prevention and control must address primary prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship while also addressing racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities. Racial/ethnic disparities in cancer survival, for example, are largely attributable to poverty, delayed screening, differences in provider care recommendations, and lack of access to the latest treatments.5 Similarly, emerging evidence indicates that people of color are more likely to die from COVID-19 for many reasons that are preventable.6 As the evidence for effective strategies to treat and manage COVID-19 accumulates, the potential to increase disparities also increases because access to these advances is unlikely to be equally distributed across all groups. In addition, established underlying risk factors such as poor diet, sedentariness, lack of insurance, and other factors related to healthcare access,5 along with stress and poor sleep,7 would be expected to work synergistically to amplify outcome disparities in both cancer and COVID-19.

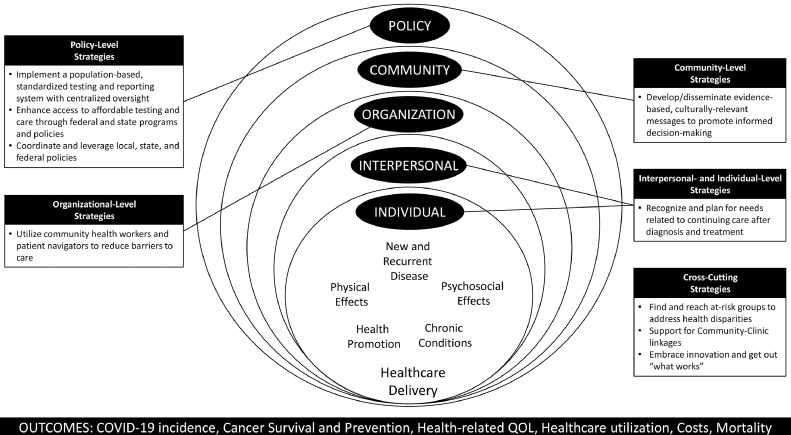

Thomson and colleagues utilized the Quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework8 to describe the potential strategies for addressing the challenge of cancer survivorship care delivery and cancer-related disparities in the COVID-19 era. In this paper, the focus is on the outer rings of the framework (Figure 1), which mirror the multilevel socioecologic model of public health9 to illustrate additional opportunities for effective actions.

Figure 1.

Public health focus on interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy efforts to advance the Cancer Survivorship Quality Care Framework under COVID-19.

QOL, quality of life.

Specific recommendations described in this paper are based on more than a decade of collaborative efforts within the Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network (CPCRN). The CPCRN is a national research and practice network of academic, public health, and community partners who work together to reduce the burden of cancer, especially among those affected disproportionately. The CPCRN is funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with support from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as part of their efforts to effectively translate research into practice. It is the longest-standing and largest thematic research network of the Prevention Research Centers Program, CDC's flagship program for preventing and controlling chronic diseases. The goal of these collective recommendations is to inform national response strategies and reduce the burden of COVID-19 and related disparities.

POLICY-LEVEL STRATEGIES

Guide Public Health Planning With Population-Based Data From a COVID-19 Registry System With Centralized and Transparent Oversight

Cancer control has benefited from the use of accurate and reliable testing methods recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and others, along with mandated reporting of a standardized set of data elements to cancer registries at the state level, which are coordinated and financially supported by CDC's National Program of Cancer Registries and the NCI's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. The resulting standardization and centralization of cancer registry data were key to the identification of disparities in mortality resulting from late-stage diagnosis, leading to targeted funding and support for breast, cervical, and colon cancer early detection programs to reach vulnerable populations.10 These registries could serve as models for rapidly evolving COVID-19 surveillance systems such as the NIH COVID-19 Cohort Collaborative (ncats.nih.gov/n3c). Continuing support for the expansion of this COVID-19 registry could be instrumental in moving toward a population-based case ascertainment system and standardized data collection protocols for important factors such as race/ethnicity not yet present with COVID-19 surveillance.11

Coordinate and Leverage Local, State, and Federal Actions and Policies

Policies and laws regarding face coverings, gatherings, and the operation of businesses during the COVID-19 era have been communicated by a complex and confusing web of various state and local officials, creating a haphazard and lackluster response in many communities. Similarly, in the absence of federal regulations, states historically implemented an array of tobacco control strategies with varying results. States that made larger investments with integrated approaches in health communication campaigns and comprehensive tobacco-free policies have seen larger declines in cigarette sales as well as greater reductions in the prevalence of smoking among both adults and youth.12 Similar coordination in responses and resources is needed to ensure that COVID-19 policies do not perpetuate or exploit existing disparities across communities.

Enhance Access to Timely, Affordable COVID-19 Testing and Treatment Through Federal and State Programs and Policies

CDC's Colorectal Cancer Control Program and the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program support programs to increase preventive screenings. Offering low- and no-cost screenings, reduced time and distance to service locations, expanded clinic hours to meet client needs, and modifying administrative procedures such as scheduling and referrals are evidence-based strategies deployed in these cancer control programs to reach and sustain services for the most vulnerable.13 Continued expansion of efforts to improve the accessibility of COVID-19 testing combined with the implementation of these approaches will require additional resources to replicate in the pandemic response.

Estimates indicate that between 10 and 26 million Americans have lost health insurance since the COVID-19 economic crisis began.14 The importance of healthcare coverage was illustrated in a 2019 study of the impact of the Affordable Care Act, which found larger increases in breast and colon cancer screenings in states that expanded Medicaid coverage than in those that did not.15 Recent data indicate that hospitalization rates are 3–4 times higher among Latinx, Black, and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals, likely further increasing the impact of state-level policies regarding Medicaid expansion in the disparate burden of COVID-19.16 Given the high reported costs of COVID-19 management in many settings,17 attention must also be given to the financial burden of COVID-19 with a focus on the under/uninsured, the elderly on fixed incomes, and low-income populations most likely to be harmed financially.

COMMUNITY-LEVEL STRATEGIES

Develop and Disseminate Evidence-Based, Culturally Relevant Messages to Promote Informed Decision Making

Given the furious pace of scientific discoveries regarding the risks associated with the novel coronavirus, the importance of disseminating clear, compelling, and timely messaging is critical to individual informed decision making. Ensuring cultural relevance and plain language and engaging target audiences in message development and testing have been widely applied to cancer prevention and control with great success and can inform COVID-19 interventions.18

Health literacy and language translation are other important considerations in developing targeted communication materials. To ensure plain language, it is recommended that materials designed are within a sixth-grade reading level.19 Given the disproportionate burden of poor COVID-19 outcomes among people of color, especially those in low-income neighborhoods with limited access to testing and healthcare services, it is critical that any health-related messaging is meaningful to the groups that need these services the most, including the diverse subgroups within Black, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, immigrant, and Spanish-speaking communities.

ORGANIZATIONAL-LEVEL STRATEGIES

Utilize Community Health Workers and Patient Navigators to Reduce Barriers to Screening/Testing and Treatment

As efforts and funding are being redirected to build public health infrastructure in response to the COVID-19 crisis, the community health worker/patient navigator workforce is a vital link between healthcare clinics and communities to provide resource coordination and reduce the disproportionate burden of COVID-19. This workforce addresses structural barriers through scheduling and referral assistance, linking to resources for transportation and translation, delivering patient education and reminders, and assisting with issues related to insurance coverage and linkage to care.13 Many of the barriers to care addressed by community health workers/patient navigators are related to social determinants of health such as employment, poverty, housing, and transportation.20 Notably, these social factors important in determining the risk of cancer and poor cancer outcomes are also directly related to exposure to and transmission of COVID-19.

INTERPERSONAL-/INDIVIDUAL-LEVEL STRATEGIES

Recognize and Plan for the Needs Related to Continuing Care After Diagnosis and Treatment

Although the long-term impact of a COVID-19 diagnosis is unknown, early data suggest that for many patients, even for those with mild or moderate disease, relapsing symptoms and long-term effects may be common. Studies of the effects of treatment and recovery from COVID-19 will soon be underway to understand ongoing needs related to respiratory or other rehabilitative care (https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/who-we-are/nih-director/statements/nih-launches-new-initiative-study-long-covid). Survivorship care planning to ameliorate late and long-term side effects from a cancer diagnosis is recommended by CDC, the NCI, and the American Cancer Society, and similar protocols may be needed to guide primary care physicians caring for COVID-19 survivors. Advocacy groups such as the American Cancer Society and Livestrong serve as models for what is needed with patient advocacy engagement in a comprehensive long-term response.

CROSS-CUTTING IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES FROM THE CANCER PREVENTION AND CONTROL RESEARCH NETWORK

Decades of collaborative cancer prevention and control research in real-world settings can further guide research translation efforts and practical actions in response to the current pandemic.

Find and Reach At-Risk Groups to Address Disparities

Investigators from the CPCRN have partnered with safety net clinics, faith-based organizations, border and rural health organizations, regional and statewide health fairs, 2-1-1 call lines, and other community-based partners to reach at-risk groups.21 Given that many of the essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic are from racial minority and low-income groups, employers, homeless shelters, food banks, and other community partners represent an especially important route for reaching these groups.

Support Community–Clinic Linkages

There is strong evidence to support the combined action within different sectors at multiple levels, including the family, workplace, community, and healthcare system to optimize prevention and control programs. For example, CPCRN researchers across multiple funding cycles and geographic locations collaborated with CDC Colorectal Cancer Control Program and demonstrated that grantees can further increase screening rates by intervening at multiple levels.22 Other CPCRN researchers implemented an evidence-based intervention for cancer survivors delivered by peers, confirming that not all programs need to be delivered in healthcare settings to be effective.21

Scale Up and Spread Using Strategies Known to Work

Even with the existence of ample evidence, proven strategies in cancer prevention and control still require extensive effort to promote their adoption and implementation. Reducing community spread and the risk for coronavirus infection depends on disseminating coherent, evidence-based public health programs and scaling them out to local communities. Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics-Underserved Populations is an initiative of NIH to reach those disproportionately affected by COVID-19 by making testing resources readily accessible and partnering with communities. CPCRN members developed training and technical assistance activities (e.g., Putting Public Health into Action) to similarly bridge the gap between research and practice and help program developers find and use evidence combined with capacity building among practitioners that could serve as a model for Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics-Underserved Populations and other related initiatives.21 , 22 In addition, as innovations such as telehealth are adopted and disseminated during the pandemic, ongoing attentiveness is needed to ensure that disparities are not perpetuated or even amplified.

The available strategies to reduce the morbidity and mortality of COVID-19 shown in Table 1 are solidly grounded in real-world experience from cancer prevention and control efforts. With the recent availability of vaccines for COVID-19, implementing these policy, communication, and multilevel strategies from cancer prevention and control programs is of even more critical importance. For example, multilevel strategies in partnership with the healthcare system, schools, and community have had a positive impact on vaccination rates for human papillomavirus.13 These strategies include many of the same activities outlined in Table 1, such as low- or no-cost clinical preventive services, targeted messaging, reminders, and multicomponent interventions. Taken together, these examples highlight the importance and potential of translating this knowledge to public health programs that can effectively address the unprecedented challenge posed by COVID-19.

Table 1.

Nine Essential Elements for Effective COVID-19 Control and Prevention Based on Evidence-Based Strategies and Best Practices From Cancer Control and Prevention

| Elements | Description/evidence |

|---|---|

| Support a nationally-integrated learning health system | |

| Policy-level strategy: Implement a population-based standardized COVID-19 testing and reporting system with centralized and transparent oversight. | Provide sustained funding for a centralized testing registry in CDC similar to the cancer registry program to support states in implementing and reporting testing data Disseminate rapid testing and publicly report regular and timely case counts, including outcome reporting to assist with the monitoring of the impact of various control and prevention strategies Standardize the measurement of race and ethnicity to monitor trends and disparities |

| Policy-level strategy: Coordinate and leverage local, state, and federal actions and policies. | Standardize and coordinate the recommendations for face coverings, large gatherings, and other operational protocols across local, state, and federal policies Monitor and track the outcomes of policies across all levels to coordinate and improve response |

| Strengthen the healthcare safety net | |

| Policy-level strategy: Enhance access to affordable COVID-19 testing and care through federal and state programs and policies. | Reduce structural barriers to COVID-19 screening and testing through increased clinic hours, number, and location of sites offering free or affordable services Establish federal funding mechanisms to partner with state programs to deliver consistent, evidence-based prevention, testing, and treatment opportunities Promote state-level policies that facilitate increased health insurance coverage and affordable access to testing and treatment Fund state Medicaid programs to provide testing and treatment services, especially among those newly unemployed or uninsured owing to COVID-19; prepare for vaccine implementation |

| Community-level strategy: Develop and disseminate evidence-based, culturally relevant messages to promote informed decision making. | Promote the use of consistent, evidence-based core messaging related to COVID-19 community mitigation strategies (including vaccines when available) in culturally relevant formats Create a clearinghouse of theory and evidence-based messages, materials, and interventions modeled after CDC's Community Guide and NCI Cancer Control Planet to promote evidence-based prevention and health promotion strategies relevant to COVID-19 Create immediate funding opportunities administered through CDC to states to deliver and evaluate COVID-19 prevention and health promotion campaigns and programs to build an inventory and promote the use of effective evidence-based approaches for communication Assure cultural, behavioral, language concordant, and literacy-based adaptations of messaging for optimal impact on health behaviors |

| Organizational-level strategy: Utilize community health workers and patient navigators to reduce barriers to care. | Establish federal funding mechanisms to support the use of community health workers, patient navigators, and cooperative extension workers to reach at-risk populations, educating them about preventive behaviors for COVID-19 risk and encouraging testing when appropriate Deploy expertise from within communities to address social determinants of health and reduce barriers to care within their communities |

| Interpersonal//individual-level strategy: Recognize and plan for needs related to continuing care after diagnosis and treatment. | Partner with COVID-19 survivor advocates to establish a research and funding agenda Establish funding for research to understand COVID-19 survivorship needs, provide survivor monitoring, and identify ongoing needs and concerns Incentivize providers to provide long-term, comprehensive treatment plans |

| Reduce health disparities | |

| Cross-cutting strategy: Find and reach at-risk groups to address disparities. | Work with trusted delivery channels present in communities, such as faith-based organizations, recreational districts, cooperative extension, advocacy groups, social media influencers, to deliver evidence-based, consistent education/health promotion efforts Partner with employers to implement education and interventions, testing opportunities, and extend employee COVID-19 control efforts to home and family |

| Leverage multisectoral strengths and partnerships | |

| Cross-cutting strategy: Support community‒clinic linkages. | Financially incentivize partnerships and multilevel interventions involving schools, employers, community-based organizations, primary care providers, and other healthcare system providers to deliver individual- and family-centered messaging about risk reduction Provide supplies to support COVID-19 control measures and support and fund prevention campaigns and contact tracing and testing through these outlets Offer multilevel strategies to promote COVID-19 vaccine uptake (i.e., public education) and vaccination in their communities (i.e., pharmacies, community health centers, colleges); media campaigns with provider recommendation |

| Disseminate effective cancer prevention and control strategies for rapid translation in practice | |

| Cross-cutting strategy: Scale up and spread dissemination and implementation strategies known to work. | Synthesize emerging real-world evidence for decision makers Identify dissemination-ready strategies Create immediate funding opportunities for academic, healthcare systems, and community-based organizations to serve as COVID-19 prevention and control training hubs Invest in infrastructure and best practices for telehealth for monitoring of COVID-19 cases, especially in those with underlying health conditions who are at high risk for complications Support efforts for expanded high-speed broadband connectivity services and cellular network expansion for remote health care capacity building Support innovation in testing, including at-home options and pooled testing to expand the reach to at-risk populations and reduce costs |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NCI, National Cancer Institute.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Cancer Prevention Control Research Network Coordinating Center staff who supported the meetings of the author group, figure design, and manuscript editing. The authors would also like to acknowledge Alexa Young for her creative support in developing Figure 1 in this paper.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the official views of CDC/HHS nor an endorsement by CDC/HHS or the U.S. Government.

This publication is a product of a Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Center supported by Cooperative Agreement Numbers U48 DP006399, U48 DP006401, U48 DP006413, U48 DP006377, and U48 DP006400 from CDC.

This publication was supported by CDC of HHS as part of a financial assistance award totaling $9,298,691 with 100% funded by CDC/HHS.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schuchat A, CDC COVID-19 Response Team Public health response to the initiation and spread of pandemic COVID-19 in the United States, February 24-April 21, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(18):551–556. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li H. Successes and struggles in the war on cancer: an interview with Vincent DeVita, MD. Yale J Biol Med. 2019;92(4):805–808. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31866797 Accessed March 24, 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers DA. Considering the intersection between implementation science and COVID-19. Implement Res Pract. May 21, 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020925994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(2):78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075–1091. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15020152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, Mayer DK, Shulman LN, Geiger AM. Developing a quality of cancer survivorship care framework: implications for clinical care, research, and policy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(11):1120–1130. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henley SJ, Thomas CC, Lewis DR. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part II: progress toward Healthy People 2020 objectives for 4 common cancers. Cancer. 2020;126(10):2250–2266. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross CP, Essien UR, Pasha S, Gross JR, Wang SY, Nunez-Smith M. Racial and ethnic disparities in population-level Covid-19 mortality. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3097–3099. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06081-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2014. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs–2014.https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices/index.htm Published Accessed November 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guide to community preventive services: about the community guide. The Community Guide. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/about/about-community-guide. Updated January 24, 2020. Accessed August 15, 2020.

- 14.Banthin J, Simpson M, Buettgens M, Blumberg LJ, Wang R. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Princeton, NJ: July 13, 2020. Changes in health insurance coverage due to the COVID-19 recession: preliminary estimates using microsimulation.https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2020/07/changes-in-health-insurance-coverage-due-to-the-covid-19-recession–preliminary-estimates-using-microsimulation.html?cid=xem_other_unpd_ini:quickstrike_dte:20200713_des:coverage%20changes;%20covid Published Accessed September 9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedewa SA, Yabroff KR, Smith RA, Goding Sauer A, Han X, Jemal A. Changes in breast and colorectal cancer screening after Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html. Updated February 18, 2020. Accessed January 26, 2021.

- 17.Substantial direct medical costs for symptomatic COVID-19 cases in the U.S. PharmacoEcon Outcomes News. 2020;852(1):31. doi: 10.1007/s40274-020-6790-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meade CD, McKinney WP, Barnas GP. Educating patients with limited literacy skills: the effectiveness of printed and videotaped materials about colon cancer. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(1):119–121. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stableford S, Mettger W. Plain language: a strategic response to the health literacy challenge. J Public Health Policy. 2007;28(1):71–93. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman HP. Patient navigation: a community based strategy to reduce cancer disparities. J Urban Health. 2006;83(2):139–141. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9030-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernández ME, Melvin CL, Leeman J. The Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network: an interactive systems approach to advancing cancer control implementation research and practice. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(11):2512–2521. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribisl KM, Fernandez ME, Friedman DB. Impact of the Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network: accelerating the translation of research into practice. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3):S233–S240. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.08.0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]