The structure of acetoacetyl-CoA reductase from Rickettsia felis, the causative agent of flea-borne spotted fever, is reported. Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase is a key enzyme in both the glyoxylate/dicarboxylate and butanoate metabolic pathways.

Keywords: SSGCID, structural genomics, Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, oxidoreductase, Rickettsia, acetoacetyl-CoA reductase, PhaB

Abstract

Rickettsia felis, a Gram-negative bacterium that causes spotted fever, is of increasing interest as an emerging human pathogen. R. felis and several other Rickettsia strains are classed as National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases priority pathogens. In recent years, R. felis has been shown to be adaptable to a wide range of hosts, and many fevers of unknown origin are now being attributed to this infectious agent. Here, the structure of acetoacetyl-CoA reductase from R. felis is reported at a resolution of 2.0 Å. While R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase shares less than 50% sequence identity with its closest homologs, it adopts a fold common to other short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family members, such as the fatty-acid synthesis II enzyme FabG from the prominent pathogens Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus anthracis. Continued characterization of the Rickettsia proteome may prove to be an effective means of finding new avenues of treatment through comparative structural studies.

1. Introduction

Rickettsia felis, an obligate intracellular bacterium that has emerged as a human pathogen in the last two decades, is the causative agent of flea-borne spotted fever (Abdad et al., 2011 ▸; Angelakis et al., 2016 ▸; Blanton & Walker, 2017 ▸; Legendre & Macaluso, 2017 ▸; Pérez-Osorio et al., 2008 ▸). Recent research has classed R. felis into a third transitional group of Rickettsia that is distinguishable from the typhus and spotted fever groups, sharing genetic characteristics of both (Angelakis et al., 2016 ▸; Ogata et al., 2005 ▸). R. felis has been shown to have a wider range of hosts than most Rickettsiae, having been found in several species of fleas, ticks and mites (Angelakis et al., 2016 ▸; Brown & Macaluso, 2016 ▸; Legendre & Macaluso, 2017 ▸). Additionally, Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes, which are the primary malarial vector in sub-Saharan Africa, have been shown to support R. felis infection (Abdad et al., 2011 ▸; Angelakis et al., 2016 ▸; Dieme et al., 2015 ▸; Socolovschi et al., 2012 ▸). This host adaptability, combined with geographical expansion in recent years and the capacity for further expansion with climate change, makes R. felis of particular interest as a mounting global health risk.

The Gram-negative R. felis has a genome of nearly 1.6 million base pairs spread across a 1.49 million base-pair circular chromosome and a conjugative plasmid, which is found in two forms (Ogata et al., 2005 ▸). Only one other Rickettsia strain has been isolated with a conjugative plasmid (Angelakis et al., 2016 ▸). Among a total of 1512 recognized R. felis ORFs, the phbB gene encodes acetoacetyl-CoA reductase, a key protein in several biosynthetic pathways including glyoxylate/dicarboxylate metabolism and butanoate metabolism (EC 1.1.1.36). Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase catalyzes the following general chemical reaction (KEGG reaction R01779):

In both glyoxylate/dicarboxylate metabolism (KEGG pathway ec00630) and butanoate metabolism (KEGG pathway ec00650), acetoacetyl-CoA reductase catalyzes the production of (3R)-3-hydroxybutanoyl-CoA (KEGG reaction R01977) (Kanehisa, 2019 ▸; Kanehisa et al., 2012 ▸, 2016 ▸). In glyoxylate/dicarboxylate metabolism, this metabolite is next converted to crotonyl-CoA, which is an intermediate in lysine and tryptophan metabolism as well as in fatty-acid synthesis. In butanoate metabolism, (3R)-3-hydroxybutanoyl-CoA can be converted into the polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) polybetahydroxybutrate (PHB). The PHAs are natural polyesters (Chen, 2010 ▸; Sagong et al., 2018 ▸; Verlinden et al., 2007 ▸). The synthesis of PHAs occurs in many bacteria under physiological stress, serving as an energy- and redox-storage material and allowing the organism to survive harsher environmental conditions (Chen, 2010 ▸; Lam et al., 2019 ▸; Sagong et al., 2018 ▸). PHAs are of interest industrially as a biodegradable, biologically sourced substitute to traditional petroleum-based plastics (Chen, 2010 ▸; Sagong et al., 2018 ▸; Verlinden et al., 2007 ▸). Many of the metabolites produced downstream of acetoacetyl-CoA ultimately feed into the principal energy pathways of the cell, including the citrate cycle and gluconeogenesis.

Targeting microbial enzymes from basic biosynthetic pathways remains a promising approach in the development of new antibiotics. Recent studies have shown success, such as the identification of amycomicin, a novel, potent inhibitor of the fatty-acid synthesis II (FAS-II) enzyme FabH (Pishchany et al., 2018 ▸). Other inhibitors of FAS-II enzymes such as FabI and FabG have also shown promise (Lu & Tonge, 2008 ▸; Waller et al., 2003 ▸; Wang & Ma, 2013 ▸; Zhang et al., 2006 ▸). However, there are many challenges to surmount before drugs are clinically approved; thus, increased characterization of metabolic enzymes is necessary to inform further drug development.

Although the structural coverage of Rickettsia proteomes has grown in the last decade, only four of the >100 000 entries in the Protein Data Bank (Berman et al., 2000 ▸) are from R. felis. As part of the structural genomic studies at the Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, here we present the expression, purification, crystallization and structural analysis of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase at 2.0 Å resolution.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protein purification and expression

Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase from R. felis was cloned, purified and crystallized by the Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease (SSGCID; Myler et al., 2009 ▸; Stacy et al., 2011 ▸) following a previously described established protocol (Bryan et al., 2011 ▸; Choi et al., 2011 ▸). The 241-residue sequence (UniProt ID Q4UN54; GenBank ID AAY61004.1) was cloned into the pBG1861 vector via LIC cloning (Alexandrov et al., 2004 ▸; Aslanidis & de Jong, 1990 ▸), producing a construct with a noncleavable N-terminal 6×His tag. Transformed Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells were grown in 2 l auto-induction medium at 20°C for 72 h in a LEX Bioreactor (Harbinger, Markham, Ontario, Canada). The cell pellet was flash-frozen for storage, thawed and resuspended in 200 ml lysis buffer [20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 30 mM imidazole, 0.5% CHAPS, 10 mM MgCl2, 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1.3 mg ml−1 protease-inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), 0.05 mg ml−1 lysozyme]. The suspension was sonicated and then incubated with 20 µl Benzonase nuclease (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, New Jersey, USA) for 40 min prior to clarification by centrifugation at 10 000 rev min−1 for 60 min in a F14S Rotor (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The clarified solution was filtered with a 0.45 µm filter prior to affinity chromatography. The sample was run over a HisTrap FF 5 ml column (GE Biosciences, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA) equilibrated with binding buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 30 mM imidazole, 1 mM DTT) and the bound protein was eluted using the same buffer with 500 mM imidazole. The peak fractions were pooled, concentrated and further purified on a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 column (GE Biosciences) in SEC buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM TCEP). After peak analysis with SDS–PAGE, the pure fractions were pooled, concentrated to a final concentration of 69.7 mg ml−1 and frozen using liquid nitrogen. The purified protein and/or the clone can be obtained at https://apps.sbri.org/SSGCIDTargetStatus/Target/RifeA.00170.a.

Purified protein acquired from the SSGCID was run on 12% SDS–PAGE using Precision Plus Unstained Protein Standards, and a standard curve was generated using previously described methods (https://www.bio-rad.com/webroot/web/pdf/lsr/literature/Bulletin_3133.pdf; Merril, 2000 ▸). Size-exclusion chromatography with a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg column (GE Lifesciences) was used to verify the oligomerization state and the column was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s protocols with the Gel Filtration Calibration HMW Kit (https://www.cytivalifesciences.com/en/us/shop/chromatography/prepacked-columns/size-exclusion/gel-filtration-calibration-kits-lmw-hmw-p-05801; Irvine, 2000 ▸). Macromolecule-production information is summarized in Table 1 ▸.

Table 1. Macromolecule-production information.

| Source organism | R. felis (strain ATCC VR-1525/URRWXCal2) |

| DNA source | GenBank ID AAY61004.1 |

| Cloning vector | pBG1861 |

| Expression vector | pBG1861 |

| Expression host | E. coli BL21(DE3) |

| Complete amino-acid sequence of the construct produced | MAHHHHHHMSEIAIVTGGTRGIGKATALELKNKGLTVVANFFSNYDAAKEMEEKYGIKTKCWNVADFEECRQAVKEIEEEFKKPVSILVNNAGITKDKMLHRMSHQDWNDVINVNLNSCFNMSSSVMEQMRNQDYGRIVNISSINAQAGQVGQTNYSAAKAGIIGFTKALARETASKNITVNCIAPGYIATEMVGAVPEDVLAKIINSIPKKRLGQPEEIARAVAFLVDENAGFITGETISINGGHNMI |

2.2. Crystallization

Purified R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase at 23 mg ml−1 was crystallized using a previously described standardized SSGCID approach (Subramanian et al., 2011 ▸). Single crystals were obtained by vapor diffusion in sitting drops at 290 K from Microlytic MCSG1 screen condition G1: 10%(w/v) PEG 8000, 8%(v/v) ethylene glycol, 100 mM HEPES–NaOH pH 7.5. The crystal was cryoprotected in a mixture of reservoir solution and 20%(v/v) ethylene glycol and vitrified in liquid nitrogen. Crystallization information is summarized in Table 2 ▸.

Table 2. Crystallization.

| Method | Vapor diffusion, sitting drop |

| Temperature (K) | 290 |

| Protein concentration (mg ml−1) | 23 |

| Buffer composition of protein solution | 20 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM TCEP |

| Composition of reservoir solution | 10% PEG 8000, 8% ethylene glycol, 100 mM HEPES–NaOH pH 7.5 |

| Protein:precipitant ratio | 1:1 |

| Volume of reservoir (µl) | 80 |

2.3. Data collection and processing

A 2.0 Å resolution data set was collected on beamline BL7-1 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at 100 K using a wavelength of 1.12709 Å. Diffraction data were processed with XDS/XSCALE (Kabsch, 2010 ▸), and the diffraction images are available from the Integrated Resource for Reproducibility in Macromolecular Crystallography (http://proteindiffraction.org/; Grabowski et al., 2016 ▸) at https://doi.org/10.18430/M34KMS. Data-collection details are summarized in Table 3 ▸.

Table 3. Data collection and processing.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Diffraction source | SSRL beamline BL7-1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.12709 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Detector | ADSC Quantum 315r CCD |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 225.0 |

| Space group | P21212 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 77.11, 99.70, 73.37 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–2.000 (2.050–2.000) |

| No. of unique reflections | 38871 (2820) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (100.0) |

| Multiplicity | 4.82 (4.87) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 25.78 (3.37) |

| R merge | 0.042 (0.5230) |

| R meas | 0.048 (0.586) |

| CC1/2 (%) | 100 (86.1) |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 38.1 |

2.4. Structure solution and refinement

Molecular replacement using the CCP4 program Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007 ▸) with PDB entry 3ezl (Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, unpublished work) as the search model was used to solve the structure. The structure was modeled in Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸) and refinement of the structure was completed in REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▸). The final refinement statistics are provided in Table 4 ▸. PyMOL was used to generate all structure figures (http://www.pymol.org).

Table 4. Structure refinement.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–2.00 (2.05–2.00) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 |

| σ Cutoff | F > 0.0σ(F) |

| No. of reflections, working set | 38831 (2676) |

| No. of reflections, test set | 1949 (140) |

| Final R cryst | 0.173 (0.236) |

| Final R free | 0.210 (0.288) |

| No. of non-H atoms | |

| Protein | 3478 |

| Water | 266 |

| Total | 3744 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.015 |

| Angles (°) | 1.296 |

| Average B factors (Å2) | |

| Overall | 39.98 |

| Protein | 39.80 |

| Water | 42.28 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored regions (%) | 98 |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 2 |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Oligomeric state of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase

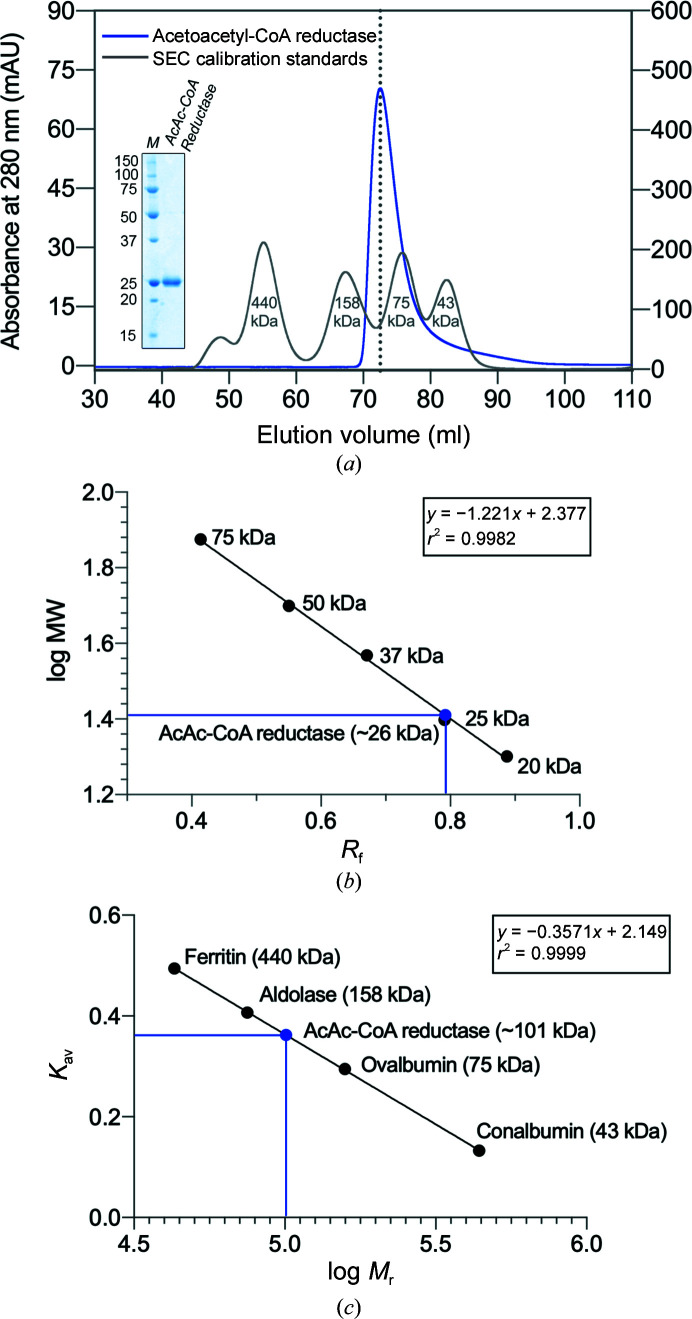

R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase migrates as a single band with a molecular weight near 25 kDa on a 12% SDS–PAGE (Fig. 1 ▸ a, inset). With an observed R f (relative migration distance) of 0.792, the molecular weight of the protein was estimated to be 25.7 kDa using a standard curve generated from the protein ladder (Fig. 1 ▸ b). ProtParam (Gasteiger et al., 2005 ▸) calculated the molecular weight of acetoacetyl-CoA reductase with the 6×His tag uncleaved to be 27.2 kDa, which is within ∼5% agreement of the gel-electrophoresis estimate.

Figure 1.

SDS–PAGE and SEC analyses of purified recombinant R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase. (a) Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase eluted as a single peak (blue line) from a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 pg SEC column. The SEC column was calibrated separately (gray line), and the molecular weights of calibration protein standards from a kit are indicated. The elution volume of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase falls between those of ovalbumin (75 kDa) and aldolase (158 kDa), suggesting a higher oligomeric state. SEC-purified acetoacetyl-CoA reductase was resolved on 12% SDS–PAGE visualized with Coomassie Blue (inset); the monomer runs as a single band (AcAc-CoA reductase) near the 25 kDa protein standard marker (lane M, labeled in kDa). A standard curve for SDS–PAGE (b) and a SEC calibration curve (c) were generated using the known protein standards. In (b), plotting the molecular weights (MW) of the protein standards versus their observed R f (relative migration; black circles), the MW of the protein monomer was estimated to be 26 kDa (blue circle). In (c), the calibration curve was obtained by plotting K av (the partition coefficient calculated using individual elution volumes) versus log relative molecular weight (M r) of the protein standards. The M r of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase was determined to be approximately 101 kDa (blue circle), indicating a tetrameric form, which is common in the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family.

The oligomeric state of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase was probed using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC; HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg). The column was calibrated using the Gel Filtration Calibration HMW Kit (Cytivia; Fig. 1 ▸ a, gray line) and the resulting calibration curve was used to calculate the relative molecular weight (M r) of the protein (Fig. 1 ▸ c). Acetoacetyl-CoA resolved as a single peak (Fig. 1 ▸ a, blue line) with an elution volume of 72.52 ml, corresponding to a partition coefficient (K av) of 0.362. The M r of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase was determined to be ∼101 kDa (Fig. 1 ▸ c, blue circle), indicating that it is likely to form a tetramer. Many other short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family members have been observed to form tetramers.

3.2. Structural overview

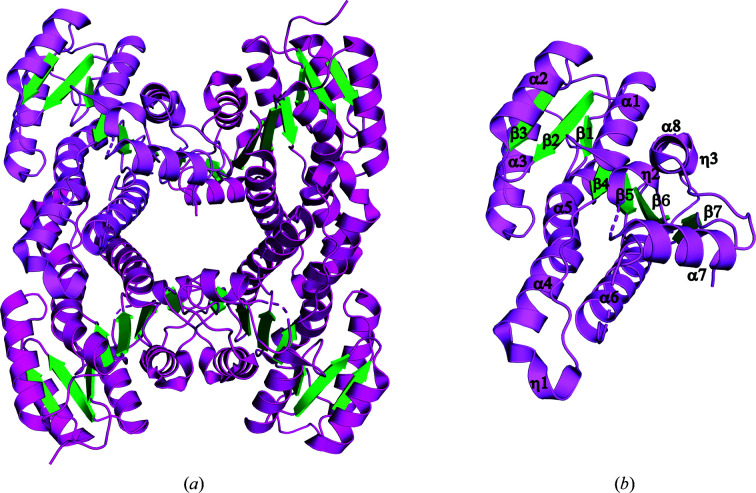

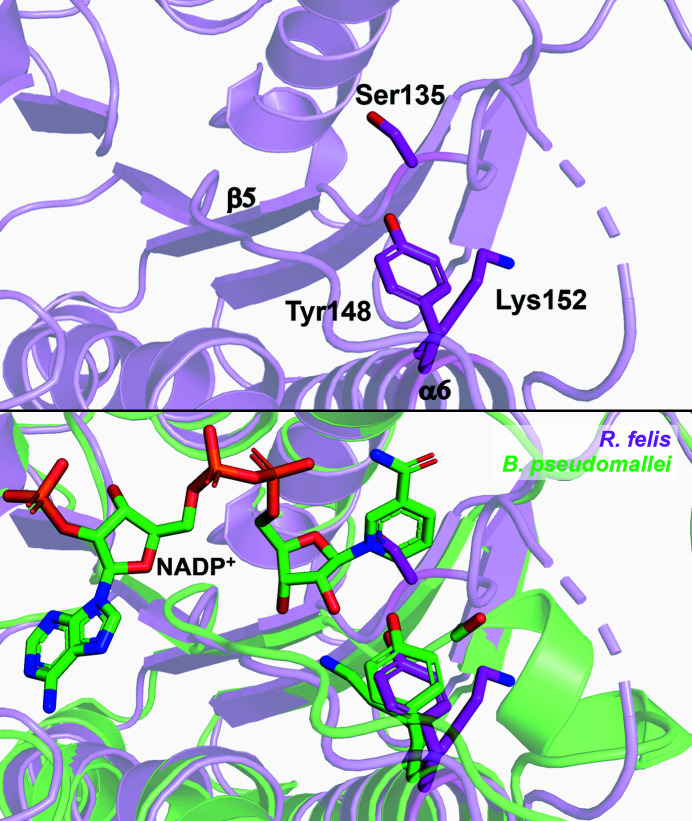

R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase has an overall similar structure to other bacterial SDR family members, including the recently solved structure of R. prowazekii 3-ketoacyl-(ACP) reductase (FabG; Subramanian et al., 2011 ▸; Fig. 2 ▸). The acetoacetyl-CoA reductase monomer adopts a Rossmann fold with a twisted seven-stranded parallel β-sheet flanked by eight α-helices. Two βαβαβ motifs comprise the core, with a short C-terminal β-strand completing the sheet. Additionally, there are three 310-helices preceding α4, α7 and β7. The conserved Ser–Tyr–Lys active-site triad, identified as residues Ser135, Tyr148 and Lys152, is located in helix α6 and the loop region connecting it to β5. Two monomers are present in the asymmetric unit; however, PISA (Krissinel & Henrick, 2007 ▸) analysis suggests a tetrameric assembly with a total buried surface area of 10 699 Å2, supporting the SEC results. The monomers have an r.m.s.d. of 0.073 Å over 227 residues, with differences localized in two loops (residues 136–144 and 185–195) where some residues could not be resolved due to flexibility. The acetoacetyl-CoA reductase tetrameter was generated by crystallographic symmetry (Fig. 2 ▸).

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase. (a) Ribbon diagram of the R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase tetramer. Helices are colored in magenta and strands in green, with a representative monomer highlighted in violet. Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase crystallized with two molecules per asymmetric unit, and a tetramer was generated by crystallographic symmetry. (b) Representative monomer of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase with secondary-structure elements labeled. The active-site residues (Ser135, Tyr148 and Lys152) are grouped in helix α6 and the connecting loop to β5.

3.3. Comparison with structurally similar proteins

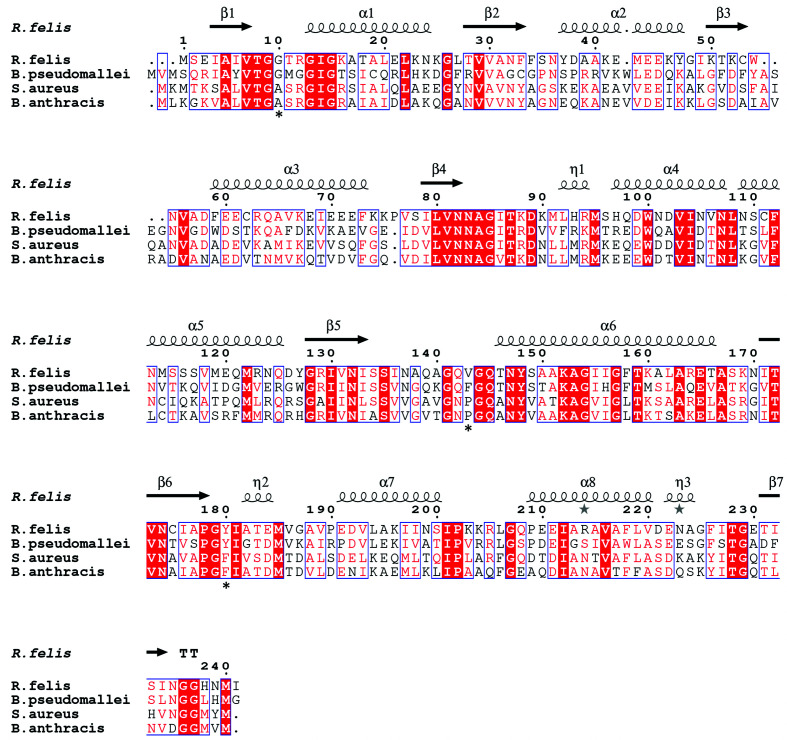

PDBeFold analysis, run with the default threshold cutoffs, was used to identify similar structures (Krissinel & Henrick, 2004 ▸). The structures most similar to R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase were other SDR family 3-ketoacyl reductases, many of which were from pathogenic Gram-negative microbes. The most similar protein to R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase was Burkholderia pseudomallei acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PDB entry 3ezl; Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, unpublished work), with 45% sequence identity and an r.m.s.d. of 1.13 Å over the Cα atoms of 229 residues. Other top matches included Staphylococcus aureus FabG (PDB entry 3osu; Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, unpublished work), with 42% sequence identity and an r.m.s.d. of 1.35 Å over 227 residues, and Bacillus anthracis FabG (PDB entry 2uvd; Zaccai et al., 2008 ▸), with 45% sequence identity and an r.m.s.d. of 1.22 Å over 224 residues (Fig. 3 ▸). Alignment of symmetry-generated tetramers demonstrates that the overall architecture is also conserved (Supplementary Fig. S1). The superposition of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase with the NADPH-bound structure of B. pseudomallei acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PDB entry 5vt6; Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, unpublished work) demonstrates the conformational rearrangements to the active-site region that are known to occur in many 3-ketoacyl reductases to accommodate catalysis, as Ser135 in the unbound state clashes with the nicotinamide ring (Fig. 4 ▸). B. pseudomallei, B. anthracis and S. aureus are the infectious agents responsible for melioidosis, anthrax and MRSA, respectively. Along with R. felis, they are all classified as National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) priority pathogens, with B. anthracis in the highest risk category (NIAID Category A).

Figure 3.

Primary-sequence alignment of acetoacetyl-CoA reductases from R. felis (PDB entry 4kms) and B. pseudomallei (PDB entry 3ezl) and of FabGs from S. aureus (PDB entry 3osu) and B. anthracis (PDB entry 2uvd). Secondary-structural elements shown include α-helices (α), 310-helices (η), β-strands (β) and β-turns (TT). Identical residues are shown in white on a red background, while conserved residues are shown in red and related residues are outlined in blue. Asterisks indicate conserved residues implicated in functional specificity. The image was generated using ESPript (Robert & Gouet, 2014 ▸).

Figure 4.

Active site of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase. The catalytic triad of R. felis (Ser135, Tyr148 and Lys152) found in helix α6 and the connecting loop to β5 is shown as sticks (magenta, top panel). Alignment of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase with NADP+-bound B. pseudomallei acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (green; catalytic triad shown as sticks) demonstrates necessary rearrangements to the active site, including movement of Ser135 and reorientation of Lys152, to accommodate substrates (lower panel).

As demonstrated above, acetoacetyl-CoA reductases (EC 1.1.1.36) share many structural similarities with FabGs (EC 1.1.1.100). Notably, FabG catalyzes an analogous reaction to acetoacetyl-CoA reductase, instead acting on acetoacetyl-ACP substrates and producing (3R)-3-hydroxyacyl-(ACP), also with NADP+ as a cofactor (KEGG reaction R02767; Chan & Vogel, 2010 ▸; White et al., 2005 ▸). FabG is the third enzyme in the fatty-acid synthase II (FAS-II) pathway (KEGG pathway ec00061). Acetoacetyl-ACPs, the substrates of FabG in the FAS-II pathway, are structurally similar to acetoacetyl-CoA, as acyl-carrier proteins (ACPs) possess the same phosphopantetheine moiety as present in CoA bound to acetoacetyl (Liu et al., 2015 ▸). Previous research has shown that FabGs have a broader substrate range and can substitute for acetoacetyl-CoA reductase in reactions, although with lower activity on CoA substrates (Ren et al., 2000 ▸; Taguchi et al., 1999 ▸; Zhang et al., 2017 ▸). Consequently, the inhibitors of FabG that are being investigated (Zhang & Rock, 2004 ▸) may also be relevant to acetoacetyl-CoA reductase.

Owing to their potential use in the manufacture of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), which are biodegradable naturally occurring plastics, there is interest in bioengineering more efficient PHA pathway enzymes, including acetoacetyl-CoA reductases (Chen, 2010 ▸; Sagong et al., 2018 ▸). One study used the structural differences between FabG and acetoacetyl-CoA reductase from Synechocystis, a flexible loop in FabG to allow the binding of large ACP substrates versus a structured α-helix in acetoacetyl-CoA reductase, to create a FabG with near-wild-type acetoacetyl-CoA reductase activity (Liu et al., 2015 ▸). Four key residues that were identified by the researchers as accounting for much of the substrate specificity in acetoacetyl-CoA reductase were swapped into FabG, enabling the change in activity (Liu et al., 2015 ▸). Both the R. felis and B. pseudomallei acetoacetyl-CoA reductases have at least three of these residues conserved (Gly10, Phe/Val143 and Tyr180; marked with asterisks in Fig. 3 ▸), while the S. aureus and B. anthracis FabGs have different residues. Although members of a protein family may have the same conserved overall fold, this study demonstrates how increasing structural characterization can expose differences that may be useful for many applications, including bioengineering or improved drug development.

4. Conclusion

The structure of R. felis acetoacetyl-CoA reductase at 2.0 Å resolution aligns closely with other previously solved structures of SDR family members, several of which are from well known human pathogens. As structural coverage of SDR family 3-ketoacyl reductases from various microbes grows, the knowledge gleaned can reveal unique, exploitable features. The transmission of R. felis to humans continues to grow, necessitating new treatments, thus broadening our understanding of essential enzymatic microbial pathways and facilitating targeted drug design. It also allows us to harness the studied biosynthetic processes, such as the biological production of naturally occurring plastics. Increased structural and biochemical knowledge of Rickettsia and other microbial proteomes remains a crucial resource.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: acetoacetyl-CoA reductase from Rickettsia felis, 4kms

Supplementary Figure S1. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X21001497/nj5302sup1.pdf

Diffraction images.: https://doi.org/10.18430/M34KMS

Acknowledgments

KJM acknowledges the support of Vassar College. We thank the SSGCID cloning and protein production groups at Seattle Children’s Research Institute.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants HHSN272201700059C and HHSN272201200025C.

References

- Abdad, M. Y., Stenos, J. & Graves, S. (2011). Emerg. Health Threats J. 4, 7168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Alexandrov, A., Vignali, M., LaCount, D. J., Quartley, E., de Vries, C., De Rosa, D., Babulski, J., Mitchell, S. F., Schoenfeld, L. W., Fields, S., Hol, W. G. J., Dumont, M. E., Phizicky, E. M. & Grayhack, E. J. (2004). Mol. Cell. Proteomics, 3, 934–938. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Angelakis, E., Mediannikov, O., Parola, P. & Raoult, D. (2016). Trends Parasitol. 32, 554–564. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Aslanidis, C. & de Jong, P. J. (1990). Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 6069–6074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T. N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N. & Bourne, P. E. (2000). Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Blanton, L. S. & Walker, D. H. (2017). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 96, 53–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brown, L. D. & Macaluso, K. R. (2016). Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 3, 27–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bryan, C. M., Bhandari, J., Napuli, A. J., Leibly, D. J., Choi, R., Kelley, A., Van Voorhis, W. C., Edwards, T. E. & Stewart, L. J. (2011). Acta Cryst. F67, 1010–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chan, D. I. & Vogel, H. J. (2010). Biochem. J. 430, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.-Q. (2010). Plastics from Bacteria: Natural Functions and Applications, edited by G.-Q. Chen, pp. 17–37. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Choi, R., Kelley, A., Leibly, D., Nakazawa Hewitt, S., Napuli, A. & Van Voorhis, W. (2011). Acta Cryst. F67, 998–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dieme, C., Bechah, Y., Socolovschi, C., Audoly, G., Berenger, J. M., Faye, O., Raoult, D. & Parola, P. (2015). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 112, 8088–8093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gasteiger, E., Hoogland, C., Gattiker, A., Duvaud, S., Wilkins, M. R., Appel, R. D. & Bairoch, A. (2005). The Proteomics Protocols Handbook, edited by J. M. Walker, pp. 571–607. Totowa: Humana Press.

- Grabowski, M., Langner, K. M., Cymborowski, M., Porebski, P. J., Sroka, P., Zheng, H., Cooper, D. R., Zimmerman, M. D., Elsliger, M.-A., Burley, S. K. & Minor, W. (2016). Acta Cryst. D72, 1181–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Irvine, G. B. (2000). Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 6, 5.5.1–5.5.16.

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M. (2019). Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Sato, Y., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. (2012). Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D109–D114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. (2016). Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2256–2268. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. (2007). J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lam, K. N., Alexander, M. & Turnbaugh, P. J. (2019). Cell Host Microbe, 26, 22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Legendre, K. & Macaluso, K. (2017). Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y., Feng, Y., Cao, X., Li, X. & Xue, S. (2015). FEBS Lett. 589, 3052–3057. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lu, H. & Tonge, P. J. (2008). Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2007). J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Merril, C. R. (2000). Anal. Biochem. 280, 333.

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Myler, P., Stacy, R., Stewart, L., Staker, B., Van Voorhis, W., Varani, G. & Buchko, G. (2009). Infect. Disord. Drug Targets, 9, 493–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ogata, H., Renesto, P., Audic, S., Robert, C., Blanc, G., Fournier, P.-E. E., Parinello, H., Claverie, J. M. & Raoult, D. (2005). PLoS Biol. 3, e248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Osorio, C. E., Zavala-Velázquez, J. E., Arias León, J. J. & Zavala-Castro, J. E. (2008). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, 1019–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pishchany, G., Mevers, E., Ndousse-Fetter, S., Horvath, D. J., Paludo, C. R., Silva-Junior, E. A., Koren, S., Skaar, E. P., Clardy, J. & Kolter, R. (2018). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 115, 10124–10129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q., Sierro, N., Witholt, B. & Kessler, B. (2000). J. Bacteriol. 182, 2978–2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Robert, X. & Gouet, P. (2014). Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sagong, H., Son, H. F., Choi, S. Y., Lee, S. Y. & Kim, K.-J. (2018). Trends Biochem. Sci. 43, 790–805. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Socolovschi, C., Pages, F., Ndiath, M. O., Ratmanov, P. & Raoult, D. (2012). PLoS One, 7, e48254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stacy, R., Begley, D. W., Phan, I., Staker, B. L., Van Voorhis, W. C., Varani, G., Buchko, G. W., Stewart, L. J. & Myler, P. J. (2011). Acta Cryst. F67, 979–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, S., Abendroth, J., Phan, I. Q. H., Olsen, C., Staker, B. L., Napuli, A., Van Voorhis, W. C., Stacy, R. & Myler, P. J. (2011). Acta Cryst. F67, 1118–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, K., Aoyagi, Y., Matsusaki, H., Fukui, T. & Doi, Y. (1999). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176, 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Verlinden, R. A. J., Hill, D. J., Kenward, M. A., Williams, C. D. & Radecka, I. (2007). J. Appl. Microbiol. 102, 1437–1449. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Waller, R. F., Ralph, S. A., Reed, M. B., Su, V., Douglas, J. D., Minnikin, D. E., Cowman, A. F., Besra, G. S. & McFadden, G. I. (2003). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. & Ma, S. (2013). ChemMedChem, 8, 1589–1608. [DOI] [PubMed]

- White, S. W., Zheng, J., Zhang, Y.-M. & Rock, C. O. (2005). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 791–831. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zaccai, N. R., Carter, L. G., Berrow, N. S., Sainsbury, S., Nettleship, J. E., Walter, T. S., Harlos, K., Owens, R. J., Wilson, K. S., Stuart, D. I. & Esnouf, R. M. (2008). Proteins, 70, 562–567. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H., Liu, Y., Yao, C., Cao, X., Tian, J. & Xue, S. (2017). Bioengineered, 8, 707–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-M. & Rock, C. O. (2004). J. Biol. Chem. 279, 30994–31001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-M., White, S. W. & Rock, C. O. (2006). J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17541–17544. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: acetoacetyl-CoA reductase from Rickettsia felis, 4kms

Supplementary Figure S1. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X21001497/nj5302sup1.pdf

Diffraction images.: https://doi.org/10.18430/M34KMS