Abstract

Nitrogen mustard (NM) and sulfur mustard are cytotoxic alkylating agents that cause severe and progressive damage to the respiratory tract. Evidence indicates that macrophages play a key role in the acute inflammatory phase and the later resolution/profibrotic phase of the pathogenic response. These diverse roles are mediated by inflammatory macrophages broadly classified as M1 proinflammatory and M2 anti-inflammatory that sequentially accumulate in the lung in response to injury. The goal of the present study was to identify signaling mechanisms contributing to macrophage activation in response to mustards. To accomplish this, we used RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to analyze the gene expression profiles of lung macrophages isolated 1 day and 28 days after intratracheal exposure of rats to NM (0.125 mg/kg) or PBS control. We identified 641 and 792 differentially expressed genes 1 day and 28 days post NM exposure, respectively. These genes are primarily involved in processes related to cell movement and are regulated by cytokines, including TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β. Some of the most significantly enriched canonical pathways included STAT3 and NF-κB signaling. These cytokines and pathways may represent potential targets for therapeutic intervention to mitigate mustard-induced lung toxicity.

Keywords: sulfur mustard, vesicants, macrophages, RNA-seq, pulmonary fibrosis

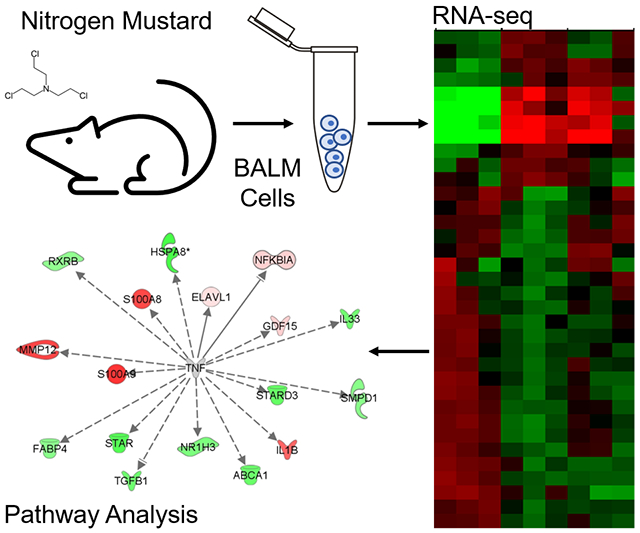

Graphical abstract

Nitrogen mustard (NM) and sulfur mustard are cytotoxic alkylating agents that cause severe and progressive damage to the respiratory tract. Evidence indicates that inflammatory macrophages play a key role in the pathogenic response. The goal of this study was to identify signaling mechanisms contributing to macrophage activation in response to mustards by using RNA sequencing to analyze the gene expression profiles of lung macrophages isolated after intratracheal exposure of rats to NM.

Introduction

Mustard vesicants including sulfur mustard (SM) and its analog nitrogen mustard (NM) are bifunctional alkylating agents and cytotoxic vesicants that were originally developed as chemical warfare agents. Upon inhalation, they cause acute damage to the respiratory tract including inflammation, alveolar–epithelial barrier dysfunction, and edema, which can progress over time to emphysema, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and/or fibrosis.1-4 The response to injury involves a sequential accumulation of neutrophils and inflammatory macrophages in the lung. While neutrophils are suspected to contribute solely to the acute response, inflammatory macrophages are present throughout the pathogenic response, contributing to both the acute inflammatory phase and the later resolution/profibrotic phase.5,6 These diverse roles are mediated by subpopulations of macrophages broadly classified as proinflammatory M1 macrophages and anti-inflammatory/wound repair M2 macrophages. Activation of macrophages toward M1 and M2 phenotypes is regulated by mediators they encounter in the tissue microenvironment. Thus, whereas proinflammatory mediators like IFN-γ, TNF-α, and TLR-4 agonists promote early M1 macrophage activation, anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13 induce M2 activation.7,8

Cytokines and inflammatory mediators modify the epigenetic landscape of macrophages, which induces gene expression profiles that regulate macrophage phenotype and activation.9 In this context, changes in gene expression profiles in macrophages after exposure to toxicants can indicate the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which toxicants adversely affect organismal health. The goal of the present study was to identify signaling mechanisms contributing to macrophage polarization and activation in response to mustards. For these studies, we used NM as a model. We previously demonstrated that NM and SM induce a similar histopathologic response in rodents, including thickened alveolar septa, perivascular edema, inflammatory cell infiltration, and disruption of the alveolar–epithelial barrier that is observed 1–3 days post exposure and progresses to necrosis by 28 days.10-15 Herein, we used RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to analyze gene expression profiles in lung macrophages isolated 1 day and 28 days after exposure of rats to NM. We hypothesized that distinct subpopulations of macrophages exhibiting unique gene expression patterns would dominate at each time point as they reflect different phases of the inflammatory response and may be derived from different origins.

Materials and methods

Animals and treatments

Male Wistar rats (225–250 g) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, Indiana) and maintained in an AALAC-approved animal care facility. Animals were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane and then intratracheally administered PBS or NM (0.125 mg/kg, mechlorethamine hydrochloride, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri) as previously described.10,16

Alveolar macrophage collection

Animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) 1 day and 28 days after administration of PBS or NM. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) was collected by slowly instilling and withdrawing 10 mL ice-cold PBS into the lung through a tracheal cannula. BAL was centrifuged (300 × g, 8 min, 4 °C) and cell pellets collected. The lung was removed from the chest cavity and an additional 10 mL of ice-cold PBS was slowly instilled and withdrawn through the cannula while gently massaging the tissue; this procedure was repeated 4 times. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (300 × g, 8 min, 4 °C) and combined with the cells collected from the first BAL. This sample is referred to as “BAL + massage” and contains a greater percentage of macrophages than cells collected by BAL alone. Differential staining showed that these cells were >96% macrophages.

Total RNA extraction and RNA-seq

Total RNA was extracted from lung macrophages using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California). RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California). cDNA libraries were prepared using an Illumnina TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation kit following the manufacturer’s guidelines (Illumina, San Diego, California). RNA-seq was performed using an Illumnina NextSeq 550 system.

Bioinformatics analysis

FASTQ files with paired-end reads were mapped to the Rn4 rat reference genome using TopHat. A table containing gene-level counts was generated by running the R Subread-featureCounts pipeline on all the resulting bam files. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (1.26.0).17,18 Genes were considered significantly different from PBS control if their Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted false discovery rate (adjusted P value) was less than 0.05 and log2(fold change) > ∣1∣ at either time point. Volcano plots were generated from counts data using EnhancedVolcano package (1.4.0) in R version 3.6.3.19 A core analysis of differentially expressed genes [(adjusted P value) < 0.05 and log2(fold change) > ∣1∣] was performed using Ingenuity Pathway analysis version 49932394 (QIAGEN Inc. https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuitypathway-analysis).20 RNA-seq data were deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE125619 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE125619).21

Results

Transcriptional profiling

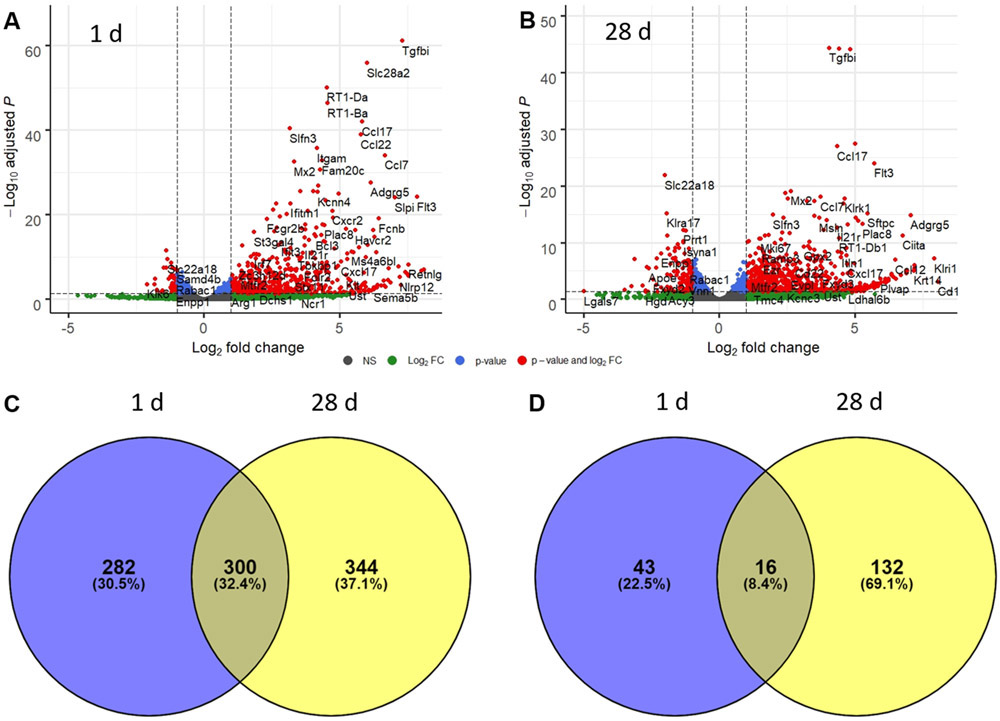

The goal of our RNA-seq analysis was to identify differentially expressed genes and significantly enriched upstream regulators and canonical pathways that may represent critical mediators of NM-induced lung toxicity. This analysis identified 641 and 792 differentially expressed genes [log2(fold change) > ∣1∣ and adjusted P value < 0.05] in lung macrophages collected 1 day and 28 days after exposure to NM, respectively (Supplementary File 1, online only). Of these, 582 were upregulated at 1 day while 644 were upregulated 28 days post exposure (Fig. 1C). Fewer downregulated genes were identified; thus, 59 genes were downregulated at 1 day and 148 genes were downregulated at 28 days (Fig. 1D). Of the upregulated genes, 300 were shared, while 282 were specifically upregulated 1 day post exposure and 344 at 28 days.

Figure 1.

Time-related alterations in alveolar macrophage gene expression following exposure of rats to nitrogen mustard (NM). Lung macrophages were collected by BAL plus massage 1 day (A) and 28 days (B) after exposure of rats to NM or PBS control. RNA was isolated and analyzed by RNA-seq (n = 3). Volcano plots depict each identified gene plotted against the −log10(adjusted P value) and log2(fold change) relative to PBS control. Grey dots, not significant; green dots, genes with adjusted P value > 0.05 and log2(fold change) > ∣1∣; blue dots, genes with adjusted P value < 0.05 and log2(fold change) < ∣1∣; red dots, genes with log2(fold change) > ∣1∣ and adjusted P value < 0.05. (C) Venn diagram depicting the distribution of significantly upregulated genes (log2(fold change) > 1 and false discovery rate (adjusted P value) < 0.05) in macrophages 1 day and 28 days post NM. (D) Venn diagram depicting the distribution of significantly downregulated genes (log2(fold change) < −1 and false discovery rate (adjusted P value) < 0.05) in macrophages 1 day and 28 days post NM.

Highly induced genes specifically upregulated at 1 day post exposure included Immune-responsive gene 1 (Irg1; also known as Acod1), C-C motif chemokine 2 (Ccl2), resistin-like alpha (Retnla), interleukin 1 beta (Il1b), and nitric oxide synthase 2 (Nos2) (Fig. 1). Ly6-C antigen (Ly6c), C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (Ccr2), and transforming growth factor, beta-induced (Tgfbi) were highly induced at both time points (Fig. 1A and B). Genes that were highly induced specifically at 28 days post exposure included collagen type IV alpha 1 chain (Col4a1) and matrix metalloproteinase 28 (Mmp28) (Fig. 1B).

Functional enrichment analysis

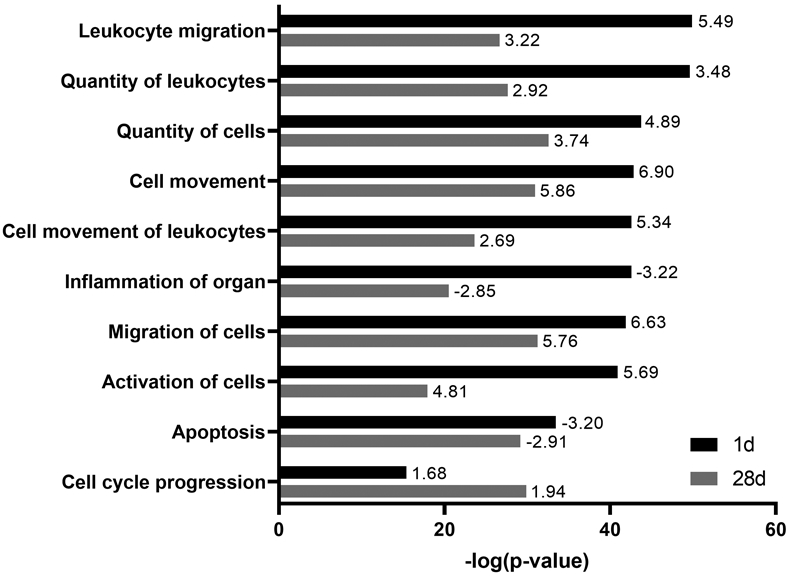

The lists of differentially expressed genes were uploaded to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software to identify statistical enrichment of diseases and functions, upstream regulators, and canonical pathways among the differentially expressed genes. A core analysis revealed that diseases and functions involved in cell movement were significantly enriched 1 day and 28 days post NM exposure, including Leukocyte migration, Cell movement, and Migration of cells. Of note, these processes were predicted to be activated, as indicated by positive activation Z-scores (Fig. 2). Conversely, significantly enriched diseases and functions including Inflammation of organ and Apoptosis were predicted to be inhibited at both time points (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Significantly enriched diseases and functions in lung macrophages after nitrogen mustard (NM) exposure. Differentially expressed genes (fold change > ∣2∣ and false discovery rate (adjusted P value) < 0.05) in macrophages 1 day and 28 days after exposure of rats to NM relative to PBS control were analyzed for enriched diseases and functions using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. A combined list of six of the most significant diseases and functions (largest −log(p-value)) at each time point is shown. Bars represent enrichment (−log(P value)) of diseases and functions 1 day (black) and 28 days (gray) after NM exposure. Numbers at tips of bars indicate activation Z-scores of each disease and function. A positive Z-score indicates activation whereas a negative Z-score indicates inhibition.

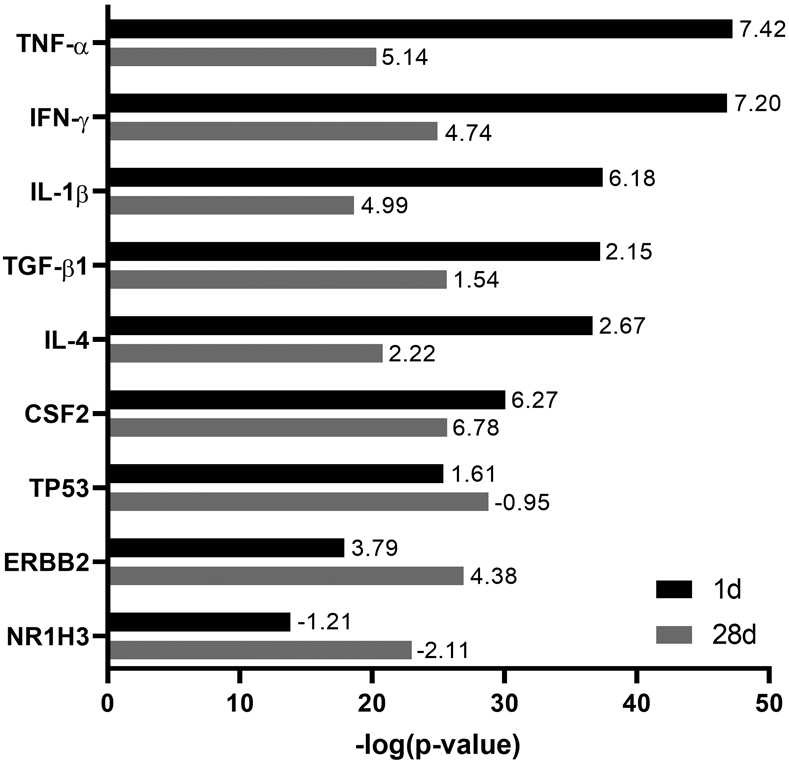

The core analysis also identified significant enrichment of upstream regulators, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interferon gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), and transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) among the differentially expressed genes at both time points (Fig. 3). These upstream regulators were more significantly enriched and exhibited higher activation Z-scores 1 day post NM exposure relative to 28 days post exposure. Upstream regulators including Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2) and Liver X Receptor Alpha (NR1H3) were more significantly enriched 28 days post exposure. Findings with NR1H3 were unexpected as it was predicted to be inhibited based on its activation Z-score (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Significantly enriched upstream regulators in lung macrophages after nitrogen mustard (NM) exposure. Differentially expressed genes (fold change > ∣2∣ and false discovery rate (adjusted P value) < 0.05) in macrophages 1 day and 28 days after exposure of rats to NM relative to PBS control were analyzed for enriched upstream regulators using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. A combined list of the six most significant upstream regulators (largest −log(P value)) at each time point is shown. Bars represent enrichment (−log(P value)) of upstream regulators 1 day (black) and 28 days (gray) after NM exposure. Numbers at tips of bars indicate activation Z-scores of each upstream regulator. A positive Z-score indicates activation whereas a negative Z-score indicates inhibition.

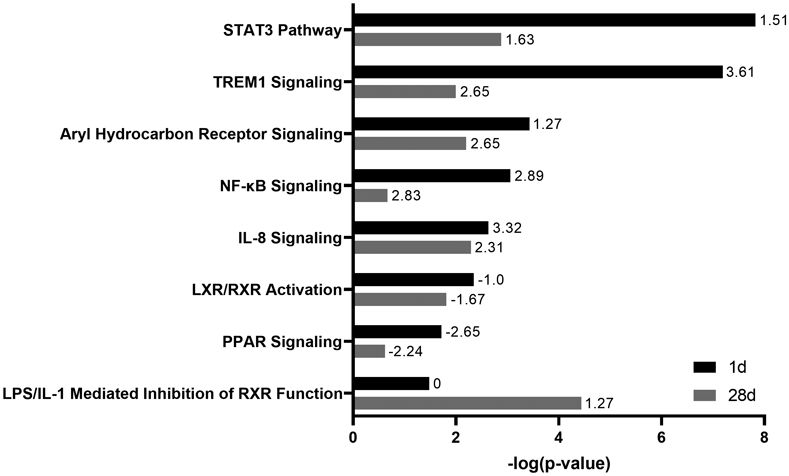

Enrichment of most canonical pathways was found to be greater at 1 day post NM exposure relative to 28 days post exposure. These included STAT3 Pathway, TREM1 Signaling, and NF-κB Signaling; these pathways were predicted to be activated based on their activation Z-scores. LPS/IL-1 Mediated Inhibition of RXR Function was one of only a few pathways more significantly enriched 28 days post NM exposure. Pathways involved in lipid metabolism were significantly enriched but predicted to be inhibited and included LXR/RXR Activation and PPAR Signaling (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Significantly enriched canonical pathways in lung macrophages after nitrogen mustard (NM) exposure. Differentially expressed genes (fold change > ∣2∣ and false discovery rate (adjusted P value) < 0.05) in macrophages 1 day and 28 days after NM exposure relative to PBS control were analyzed for enriched canonical pathways using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. A combined list of eight of the most significant canonical pathways (largest −log(P value)) at each time point is shown. Bars represent enrichment [−log(P value)] of canonical pathways 1 day (black) and 28 days (gray) after NM exposure. Numbers at tips of bars indicate activation Z-scores of each canonical pathway. A positive Z-score indicates activation whereas a negative Z-score indicates inhibition.

Discussion

RNA-seq is a robust and sensitive approach to elucidate cellular and molecular mechanisms by which toxicants adversely affect organismal health.22 In RNA-seq, effects of a toxicant on expression of thousands of genes are simultaneously analyzed to provide a snapshot of the transcriptional response to exposure. The transcriptomic data are then analyzed at the biological pathway level to interpret functional and biological outcomes of the differential gene expression; this can lead to the generation of novel hypotheses of cellular and molecular mechanisms of action of toxicants.23 Only a few studies have used transcriptomic approaches to investigate mechanisms of action of mustard agents in the lung. These include analyses of transcriptional responses of primary bronchial epithelial cells exposed to SM in vitro, of lung tissue after intravenous administration of SM to rats, and lung tissue recovered from patients 25 years after exposure to SM.24-26 While informative, these studies were limited as they were based on microarray analysis which requires a priori selection of a predefined set of genes and offers reduced sensitivity and dynamic range when compared with RNA-seq.27 In the present studies, we used RNA-seq to characterize the transcriptional response of lung macrophages to NM 1 day and 28 days following exposure; our goal was to elucidate signaling pathways involved in regulating the acute and later resolution/profibrotic phases of the inflammatory response to lung injury. We identified 641 and 792 differentially expressed genes 1 day and 28 days post exposure to NM, respectively. These genes were primarily involved in processes related to cell movement, and regulated by cytokines including TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β, among others. Some of the most significantly enriched canonical pathways included STAT3 and NF-κB Signaling. These cytokines and pathways may represent potential targets for therapeutic intervention to mitigate mustard-induced lung toxicity.

We found that more genes were differentially expressed at 1 day and 28 days post NM exposure than were similarly expressed at both time points. This is likely because these time points capture different phases of the inflammatory response to NM-induced lung injury that are characterized by the accumulation of discrete cell populations, including neutrophils and inflammatory macrophages.6 Consistent with previous findings, we identified significant upregulation of Nos2, Ptgs2, Ccl2, and Il1b at 1 day post exposure to NM.6,11 Upregulation of these genes is associated with a M1 proinflammatory macrophage phenotype. Proinflammatory/cytotoxic M1 macrophages are known to be involved in the acute inflammatory responses to pulmonary toxicants, including ozone, bleomycin, and mustard vesicants.12,28,29,30 We also identified significant upregulation of Irg1, a cis-aconitate decarboxylase that increases itaconate production and is involved in metabolic reprogramming. Increases in itaconate result in activation of anti-inflammatory pathways in activated macrophages which may contribute to the shift from a M1 to M2 dominant macrophage phenotype during later phases of the inflammatory response.31,32

Although most genes were differentially regulated specifically at either 1 day or 28 days post NM, suggesting different macrophage phenotypes dominated these time points, we did identify some overlap in differentially expressed genes at both time points. This is consistent with previous results showing both pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophages are present in the lung 1–28 days post exposure to NM.5 As reported earlier, significant increases in Ccr2 expression were observed at 1 day and 28 days post NM exposure.6 Similarly, a significant increase in expression of the macrophage activation marker Ly6C was noted at these times.7,8 These findings are in accord with the fact that inflammatory macrophages persist in the lung following NM exposure.5,6 Our observation that Tgfbi is also upregulated at 1 day and 28 days post NM may be a consequence of macrophage ingestion of apoptotic cells; this has been shown to result in downregulation of MMP14 and subsequent increases in collagen deposition.33 Likewise, we found that Mmp28 was upregulated 28 days post exposure. These data are significant as MMP28 has been reported to promote M2 macrophage polarization and to augment pulmonary fibrosis.34 Consistent with this activity, we detected a significant increase in expression of Col4a1 at 28 days post exposure to NM, which correlated with increases in collagen content in histological tissue sections.16 Our findings that Tgfbi exhibited such a substantial increase following NM exposure suggests that it may be a critical mediator of toxicity and potentially a therapeutic target. However, this remains to be investigated.

The functional enrichment analysis identified diseases and functions related to cell movement as the most significantly enriched at both 1 day and 28 days post NM exposure. This is in line with our previous findings that NM-induced injury is associated with an accumulation of macrophage subpopulations in the lung 1–28 days post exposure.10,11,12,30,35 The disease and function “activation of cells” was significantly enriched at both 1 day and 28 days in accord with our previous observation of sequential M1 and M2 macrophage activation in the lung following NM exposure.6,11 As expected, “inflammation of organ” was significantly enriched at both time points; however, the activation Z-score was negative, indicating predicted downregulation. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear but could be due to adaptive responses or negative feedback leading to down-regulation of genes promoting inflammation. Significant enrichment of diseases and functions including “apoptosis” and “cell cycle progression” is consistent with previous studies investigating transcriptional responses to sulfur mustard exposure in vivo in whole lung tissue and in vitro in bronchial epithelial cells. Significant enrichment of these pathways in each study is likely driven by the prominent effect of mustards on DNA damage and p53-mediated responses.24,25 The enrichment and predicted inhibition of apoptosis in lung macrophages after NM exposure may exacerbate injury and fibrosis, as it has been shown that increased resistance to apoptosis in both recruited and resident lung macrophages is involved in chronic inflammatory diseases and pulmonary fibrosis.36,37

TNF was identified as the most significantly enriched upstream regulator 1 day post NM exposure, and it exhibited the highest activation Z-score. This is consistent with our studies showing upregulation of TNF expression at all times following NM exposure in rats, and that administration of an anti-TNF antibody mitigated NM-induced lung injury and fibrosis.5,13 Similarly, we observed significant enrichment of other pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ and IL-1β, and the anti-inflammatory and profibrotic cytokine TGF-β1 at both post NM exposure time points. This is likely due to the presence of both pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophages during the acute inflammatory and later resolution/profibrotic phases of NM-induced lung injury.5 Significant enrichment of TP53 was expected given the ability of mustards to alkylate DNA, thereby promoting a p53-mediated DNA damage response.24

Canonical pathways including STAT3 Signaling, TREM1 Signaling, and NF-κB1 Signaling were found to be among the most significantly enriched 1 day post NM exposure, which correlates with their established role in inflammatory activation in response to lung injury.12-14,38-41 Significant enrichment and predicted downregulation of pathways involved in lipid metabolism, including LXR/RXR Activation and PPAR Signaling, were coordinate with the appearance of lipid-laden foamy macrophages in the lung in response to NM.16 These data are significant, as perturbations in lipid metabolism within macrophages has been shown to modify the inflammatory response and contribute to chronic lung diseases including fibrosis.42,43

In summary, the RNA-seq analysis described in these studies provides valuable insight into key upstream regulators and canonical pathways involved in regulating cellular movement and inflammatory activation in response to NM. One limitation of our studies is that intratracheal administration of NM may not fully recapitulate lung injury observed following inhalation of sulfur mustard in humans. However, findings that injury induced by both NM and SM is characterized by a similar histopathological progression suggests that regulators of macrophage activity would be analogous in both models.44 Future studies involving additional intermediate time points and using single-cell RNA-seq analysis would strengthen our findings as they would provide a more precise and comprehensive understanding of cellular signaling mechanisms within particular subpopulations that regulate macrophage phenotype in response to mustards throughout the time course. Overall, these studies are important in identifying potential targets for the development of therapeutics to mitigate mustard-induced pulmonary toxicity and disease pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Ronald Hart (Rutgers University) for help with the RNA-seq analysis. This work was supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (Grant/award number: U54AR055073) and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Grant/award numbers: P30ES005022, R01ES004738, R21ES029254, T32ES007148, F32ES030984).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Balali-Mood M & Hefazi M. 2005. The pharmacology, toxicology, and medical treatment of sulphur mustard poisoning. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol 19: 297–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malaviya R, Sunil VR, Venosa A, et al. 2016. Macrophages and inflammatory mediators in pulmonary injury induced by mustard vesicants. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1374: 168–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Razavi SM, Ghanei M, Salamati P, et al. 2013. Long-term effects of mustard gas on respiratory system of Iranian veterans after Iraq-Iran war: a review. Chin. J. Traumatol 16: 163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberger B, Laskin JD, Sunil VR, et al. 2011. Sulfur mustard-induced pulmonary injury: therapeutic approaches to mitigating toxicity. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther 24: 92–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunil VR, Vayas KN, Abramova EV, et al. 2020. Lung injury, oxidative stress and fibrosis in mice following exposure to nitrogen mustard. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 387: 114798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venosa A, Malaviya R, Choi H, et al. 2016. Characterization of distinct macrophage subpopulations during nitrogen mustard–induced lung injury and fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 54: 436–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray PJ 2017. Macrophage polarization. Annu. Rev. Physiol 79: 541–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, et al. 2014. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity 41: 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morales-Nebreda L, Misharin AV, Perlman H, et al. 2015. The heterogeneity of lung macrophages in the susceptibility to disease. Eur. Respir. Rev 24: 505–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunil VR, Patel KJ, Shen J, et al. 2011. Functional and inflammatory alterations in the lung following exposure of rats to nitrogen mustard. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 250: 10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venosa A, Gow JG, Hall L, et al. 2017. Regulation of nitrogen mustard-induced lung macrophage activation by valproic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor. Toxicol. Sci 157: 222–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malaviya R, Venosa A, Hall L, et al. 2012. Attenuation of acute nitrogen mustard-induced lung injury, inflammation and fibrogenesis by a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 265: 279–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malaviya R, Sunil VR, Venosa A, et al. 2015. Attenuation of nitrogen mustard-induced pulmonary injury and fibrosis by anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibody. Toxicol. Sci 148: 71–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sunil VR, Vayas KN, Cervelli JA, et al. 2014. Pentoxifylline attenuates nitrogen mustard-induced acute lung injury, oxidative stress and inflammation. Exp. Mol. Pathol 97: 89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malaviya R, Sunil V, Cervelli J, et al. 2010. Inflammatory effects of inhaled sulfur mustard in rat lung. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 248: 89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venosa A, Smith LC, Murray A, et al. 2019. Regulation of macrophage foam cell formation during nitrogen mustard (NM)-induced pulmonary fibrosis by lung lipids. Toxicol. Sci 172: 344–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Love MI, Anders S, Kim V, et al. 2015. RNA-seq workflow: gene-level exploratory analysis and differential expression. F1000Research 4: 1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Love MI, Huber W & Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15: 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Github. 2019. Blighe K, Rana S, Lewis M. Enhancedvolcano: publication-ready volcano plots with enhanced colouring and labeling. Accessed April 6, 2020 https://github.com/kevinblighe/EnhancedVolcano. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krämer A, Green J, Pollard J Jr, et al. 2014. Causal analysis approaches in ingenuity pathway analysis. Bioinformatics 30: 523–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edgar R, Domrachev M & Lash AE. 2002. Gene expression omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic. Acids Res 30: 207–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Delft J, Gaj S, Lienhard M, et al. 2012. RNA-Seq provides new insights in the transcriptome responses induced by the carcinogen benzo[a]pyrene. Toxicol. Sci 130: 427–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fry R 2015. Systems biology in toxicology and environmental health In Systems Biology in Toxicology and Environmental Health. Yosim AE & Fry R. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dillman JF, Phillips CS, Dorsch LM, et al. 2005. Genomic analysis of rodent pulmonary tissue following bis-(2-chloroethyl) sulfide exposure. Chem. Res. Toxicol 18: 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jowsey PA & Blain PG. 2014. Whole genome expression analysis in primary bronchial epithelial cells after exposure to sulphur mustard. Toxicol. Lett 230: 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Najafi A, Masoudi-Nejad A, Imani Fooladi AA, et al. 2014. Microarray gene expression analysis of the human airway in patients exposed to sulfur mustard. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res 34: 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z, Gerstein M & Snyder M. 2009. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet 10: 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fakhrzadeh L, Laskin JD & Laskin DL. 2002. Deficiency in inducible nitric oxide synthase protects mice from ozone-induced lung inflammation and tissue injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 26: 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez FO & Gordon S. 2014. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime. Rep 6: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sunil VR, Shen J, Patel-Vayas K, et al. 2012. Role of reactive nitrogen species generated via inducible nitric oxide synthase in vesicant-induced lung injury, inflammation and altered lung functioning. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 261: 22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Neill LA & Artyomov MN. 2019. Itaconate: the poster child of metabolic reprogramming in macrophage function. Nat. Rev. Immunol 19: 273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu XH, Zhang DW, Zheng XL, et al. 2019. Itaconate: an emerging determinant of inflammation in activated macrophages. Immunol. Cell Biol 97: 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nacu N, Luzina IG, Highsmith K, et al. 2008. Macrophages produce TGF-β-induced (β-ig-h3) following ingestion of apoptotic cells and regulate MMP14 levels and collagen turnover in fibroblasts. J. Immunol 180: 5036–5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gharib SA, Johnston LK, Huizar I, et al. 2014. MMP28 promotes macrophage polarization toward M2 cells and augments pulmonary fibrosis. J. Leukoc. Biol 95: 9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venosa A, Malaviya R, Gow AJ, et al. 2015. Protective role of spleen-derived macrophages in lung inflammation, injury, and fibrosis induced by nitrogen mustard. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 309: L1487–L1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larson-Casey JL, Deshane JS, Ryan AJ, et al. 2016. Macrophage Akt1 kinase-mediated mitophagy modulates apoptosis resistance and pulmonary fibrosis. Immunity 44: 582–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueno M, Maeno T, Nishimura S, et al. 2015. Alendronate inhalation ameliorates elastase-induced pulmonary emphysema in mice by induction of apoptosis of alveolar macrophages. Nat. Commun 6: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arts RJ, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, et al. 2013. TREM-1: intracellular signaling pathways and interaction with pattern recognition receptors. J. Leukoc. Biol 93: 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ornatowska M, Azim AC, Wang X, et al. 2007. Functional genomics of silencing TREM-1 on TLR4 signaling in macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 293: L1377–L1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng L, Zhou Y, Dong L, et al. 2016. TGF-β1 upregulates the expression of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 in murine lungs. Sci. Rep 6: 18946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao J, Yu H, Liu Y, et al. 2016. Protective effect of suppressing STAT3 activity in LPS-induced acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 311: L868–L880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fessler MB 2017. A new frontier in immunometabolism. Cholesterol in lung health and disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc 14: S399–S405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu X, Lee JY, Timmins JM, et al. 2008. Increased cellular free cholesterol in macrophage-specific Abca1 knock-out mice enhances pro-inflammatory response of macrophages. J. Biol. Chem 283: 22930–22941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weinberger B, Malaviya R, Sunil V, et al. 2016. Mustard vesicant-induced lung injury: Advances in therapy. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 30: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.