Abstract

We present a case series comprising three patients with concomitant septic arthritis of the knee and osteomyelitis of the femur. Early advanced imaging rendered the accurate diagnosis of the condition and the appropriate surgical approach and technique used to treat the infection. Repeated extensive surgical debridement, irrigation and insertion of antibiotic-impregnated cement rod into the femur were required, in addition to long term antibiotics. The infection in all three cases was eradicated successfully. Following a period of physical rehabilitation, they had fairly preserved independent ambulatory function. We advocate a high index of suspicion of this condition with subsequent early advanced imaging for a timely diagnosis. In addition, we described our challenges in the fabrication process of the antibiotic-impregnated cement rod.

Keywords: Septic arthritis, Knee, Femur, Osteomyelitis, Antibiotic-impregnated cement rod, Infection

Highlights

-

•

Concomitant knee septic arthritis and femoral osteomyelitis is rare.

-

•

A high index of suspicion is required for diagnosis of this condition.

-

•

Advanced imaging with MRI helps identify this condition in a timely manner.

-

•

Surgical debridement is necessary for complete eradication of infection.

-

•

The antibiotic-impregnated cement rod is effective in treating femoral osteomyelitis.

Introduction

Concomitant septic arthritis of the knee and femoral osteomyelitis in the adult is extremely rare and thus, very few are reported in literature [[1], [2], [3]]. It is more commonly seen amongst the paediatric population [4,5]. Treating this condition can be challenging especially if the surgeon is incognizant of the presence of one or the other in a patient with concomitant infection. As such, it is essential to have a high index of suspicion as well as a low threshold for advanced imaging to diagnose this condition early.

Here we describe three cases of similar presentation and surgical management of this condition. All three cases required multiple debridement and the use of an antibiotic-impregnated cement rod, with successful outcomes.

Case 1

A 69-year-old lady presented with a one-week history of left knee pain and swelling. The knee swelling had extended to the calf, in the presence of erythema, warmth and tenderness. The knee range of motion was severely limited to 30° of flexion and the patient had a temperature of 38 °C. Plain radiographs revealed a large suprapatellar effusion with no signs of cortical bony erosions (Fig. 1a). Blood investigations revealed a C-reactive protein (CRP) of 334 mg/L and a white cell count (WCC) of 18.4 × 109/L.

Fig. 1.

a Lateral view of the plain radiograph of the left knee showing a large suprapatellar effusion with no signs of bony erosion. T2-weighted MR image of the left knee revealing rim-enhancing collections (b,arrow) in the posterior knee.

Approximately 60 mL of turbid fluid containing pus was aspirated from the knee joint. Fluid culture grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). The patient underwent urgent left knee arthrotomy and debridement. Florid synovitis of the knee and pus tracking to the posterior aspect of the knee were noted. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to ascertain the extent of posterior knee involvement and the presence of osteomyelitis. The MRI showed several rim-enhancing collections in the lateral, medial and posterior aspect of the knee (Fig. 1b). The patient underwent a relook debridement and washout via a combined anterior and posterior approach to the knee (Fig. 2). However, her inflammatory markers remained elevated. A repeat MRI two weeks after the initial scan showed an interval increase in size of deep collections as well as enhanced intramedullary signals in the distal femur, indicating osteomyelitis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative findings revealing pus and necrotic tissue in the posterior knee.

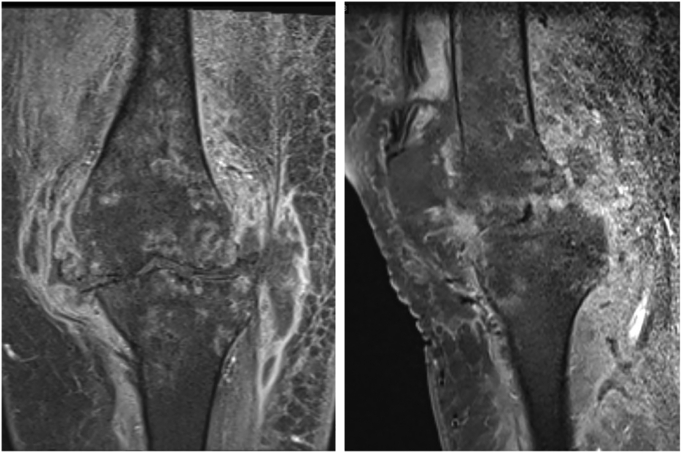

Fig. 3.

Repeat MRI showing interval worsening of the abscesses with enhancement of intramedullary signals in the femur indicating osteomyelitis.

The patient underwent another debridement with retrograde reaming of the distal femur. Reaming of the proximal tibia was performed through a cortical window made. Following the drainage of pus and thorough irrigation, vancomycin-containing bone fillers were used to fill the void of the femur and proximal tibia. Over the next few days, the patient's inflammatory markers remained high. The patient underwent a further knee debridement, reaming and irrigation of the femoral medullary canal. This time, an antibiotic-impregnated cement rod was inserted into the femur. The cement rod preparation was performed as described by Paley and Herzenberg [6]. A 2.5 mm guide rod was inserted into a 40Fr chest tube packed with 40 g of gentamicin-containing cement mixed with 4 g of vancomycin. The patient's condition had marked improvement in keeping with the decrease in the inflammatory markers.

The antibiotic cement rod was removed six weeks from time of insertion. At six months follow-up, the patient's knee range of motion was 0° to 90° and was ambulating independently with a walking stick.

Case 2

A 62-year-old gentleman complained of worsening pain and swelling in the right thigh for three days. The patient was febrile and the right knee had a painful range of motion. The inflammatory markers were also raised, revealing a CRP and WCC of 225 mg/L and 12.2 × 109/L respectively. Plain radiographs showed cortical expansion of the distal femoral shaft (Fig. 4). MRI was performed which showed an extensive multiloculated abscess of the medial thigh. An abnormal heterogenous marrow signal was seen within the distal femur, as well as a large knee effusion with the enhancement of synovial tissue signals (Fig. 5). These findings raised the suspicion of concomitant osteomyelitis of the femur and septic arthritis of the knee.

Fig. 4.

Plain radiographs showing cortical expansion of the distal femur.

Fig. 5.

T2-weighted image showing a multiloculated medial thigh abscess with increased signals (arrow) in the distal femur.

The patient underwent wound debridement of the right thigh and arthrotomy washout of the right knee. A large abscess was found involving the vastus medialis which extended to the adductor muscles posteriorly. The cortices of the distal femur remained intact, however. The knee joint fluid was turbid, and both joint fluid and tissue cultures grew MSSA.

The patient's fever recurred 7 days later with only marginal improvement in the inflammatory markers and hence, was taken back to the operating theatre for a relook arthrotomy, reaming and irrigation of the femur, and retrograde insertion of antibiotic-impregnated cement rod. The method of synthesis of the rod described in Case 1 was used. The patient's condition improved and was eventually discharged when the infection was deemed to be successfully treated.

The cement rod was removed at two months post-insertion. The patient returned to walking, initially with the support of a walking stick, subsequently pain-free and unaided at the five-month mark. There has not been any recurrence of infection after one and a half years of follow-up.

Case 3

A 65-year-old gentleman presented with recurrence of right lower limb infection eight months after having undergone two surgical debridement for a distal thigh abscess and distal femur osteomyelitis. The patient re-presented with a one-week history of right thigh pain and swelling. Prior to this presentation, the patient was symptom-free and was able to ambulate independently. The patient had a fever of 38.2 °C and on examination, a fluctuant tender lump was palpable over the right lateral thigh. There was tenderness on ranging the right knee. Blood investigations showed CRP and WCC of 78.5 mg/L and 11.0 × 109/L respectively. Plain radiographs revealed periosteal thickening of the distal femur, an indication of possible osteomyelitis (Fig. 6a). MRI confirmed an intramedullary collection within the distal femur, as well as showing an effusion in the knee (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

a Plain radiographs showing periosteal thickening of the distal femur (arrow). MRI showing enhanced intramedullary signals in the distal femur (b, arrowhead).

The patient underwent surgical debridement of the right thigh and insertion of an antibiotic-impregnated cement rod into the femoral medullary canal as well as antibiotic cement beads in the distal femur. There were large amounts of necrotic tissue with purulent material within the medullary cavity of the femur and within the knee joint. In the femur, this was seen extending from the condyles to the midshaft. Corticotomy of the distal femur and femoral reaming was performed in preparation for the cement rod and beads placement. The fabrication of the antibiotic cement rod was performed via the same method as in the previous cases. The patient was prescribed long-term intravenous antibiotics directed against Brucella spp., the organism identified from intra-operative cultures.

The cement rod was removed three months post-insertion. The patient returned to walking with the aid of a walking frame at two months follow up. At four months, the patient was ambulating with a walking stick for support. There has not been further recurrence of infection after one year of follow up.

Discussion

Septic arthritis of the knee and femoral osteomyelitis occurring concurrently in a patient is uncommon in the adult. Although the pathogenesis of this condition remains unclear, few mechanisms have been postulated. These mechanisms include the spread of infection via a haematogenous pathway between femoral metaphyseal and epiphyseal vessels [7], via a contiguous manner, or by direct inoculation [8]. In the present first two cases, the underlying mechanism is more likely to be from haematogenous spread, in view of the fact that there was no sign of periarticular bony defects in the distal femur on initial MRI to suggest direct communication between the knee joint and femur, as was seen in a case reported by Jeong et al. [1].

This concomitant infection must be identified in order to guide appropriate management. Diagnosing osteomyelitis on plain radiographs may be challenging especially if the signs on initial radiographs are too subtle to be recognized, or if there was absolutely no infection of bone to begin with but subsequently develops as septic arthritis progresses. Failure in recognizing concomitant infection can prevent clearance of infection despite repeated surgical debridement [9]. It is established that MRI is excellent in demonstrating the anatomic details of bone in high quality. It can detect signal changes in bone marrow as can be seen in osteomyelitis [10]. However, distinguishing infective marrow oedema from reactive oedema can be difficult. Karchevsky et al. found that in patients with septic arthritis, abnormal marrow signals with diffuse patterns seen on T1-weighted images had the highest association with concurrent osteomyelitis [11]. A radiological study by Monslave et al. of a paediatric population with septic arthritis and concomitant osteomyelitis suggested to come up with musculoskeletal imaging guidelines that would incorporate both conditions [12]. Albeit a study in the paediatric group, it seems pragmatic to translate this concept to the adult population as no guideline exists at present.

The treatment of chronic osteomyelitis with local antibiotic therapy began with the introduction of antibiotic-loaded polymethymethacrylate (PMMA) in 1970. Its use was established and validated by studies between the 1980s and 1990s [13]. In 1979, one author studied the use of gentamicin-impregnated beads in treating osteomyelitis in more than 100 patients and achieved a cure rate of 91.4% [14]. In an animal study, Evan and Nelson demonstrated a 100% infection control rate using gentamicin-loaded beads in combination with debridement and IV antibiotics [15]. A case series with 100 patients and 5 year follow up reported a 92% infection control rate with the use of gentamicin loaded PMMA beads [16].

Antibiotic cement beads have shown to be effective in treating osteomyelitis. However, in the context of intramedullary infection, they do not add to the structural integrity of the weakened and infected bone [17]. In addition, removing the beads can be difficult as it gets incorporated into fibrous tissue or callus bone [18]. This increases the theoretical risk of secondary infection as the beads act as foreign body and once antibiotic concentrations fall below the minimum inhibitory concentration. The alternative use of antibiotic-impregnated collagen fleece is biodegradable, and hence does not require removal. It is known to carry a higher concentration of antibiotics as well. However, similar to antibiotic beads, it does not satisfactorily fill the intramedullary dead space [19]. The advent of antibiotic cement rods enables the treatment of intramedullary osteomyelitis while providing structural stability to bone. It is effective as well as inexpensive in the treatment of intramedullary osteomyelitis [6].

Various methods in intraoperative fabrication of antibiotic rods have been described which include manual rolling of cement [20], the use of commercially available mould, and the use of a chest tube as a mould [6]. The latter was first described by Paley and Herzenberg, which was adopted in our cases. It involves inserting a 2.5 mm guide wire into a 40Fr chest tube filled with antibiotic cement mixture. Following the cooling down of cement, the plastic would be peeled off the chest tube, producing a cylindrically shaped antibiotic rod. It was in this last step that we encountered the difficulty of removing the chest tube from the cement rod. Kim et al. conducted a comparative study of fabrication techniques and hypothesized that the difficulty in the peeling of the chest tube arises due to the melting of the chest tube from exothermic reaction. They recommended the precautionary measure of mineral oil coating of the inner side of the chest tube prior to cement filling. In the same study, they found the peeling time to be 7.5 min when mineral oil was used, which was 22.5 min quicker than if mineral oil was not used. In addition, the cooling of the chest tube in saline prior to the peeling process would make this step relatively easier. The peeling can be more efficient and safer using the twin Kocher peel technique. This involves two Kocher forceps being placed perpendicular at one end of the chest tube and then rotating away from the tube [17]. Mauffrey et al. described a 2 cm longitudinal incision at one end of the hollow chest tube at the initial step to facilitate the peeling of the chest tube later on [21]. These steps should be considered for a smoother cement rod fabrication process.

Limitations

This case series had a relatively short follow up period that ranges between six months to a year and a half. All cases were treated with the same method i.e. the antibiotic cement rod and fortunately produced favourable outcomes. However, we did not study the efficacy of this method to other methods of treatment. Besides having a small number of cases here, one other limitation would be selection bias that comes with a retrospective study design.

Conclusion

Adult concomitant septic arthritis of the knee and femoral osteomyelitis is uncommon. The present cases highlight the importance of advanced imaging to diagnose this condition in a timely manner, following which extensive surgical debridement is almost always required. Antibiotic-impregnated cement rods are suitable in the local delivery of high concentration antibiotics while providing support to the bone. They have shown promising results in successfully treating this condition over the past three decades and remain an excellent choice of treatment due to simplicity, efficacy and low cost.

Role of funding source

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chee Chung Jonathan Low: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Rex Premchand Anthony Xavier: Writing – review & editing. Gek Meng Tan: Writing – review & editing. Chung Hui James Tan: Writing – review & editing. Derek Howard Park: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Jeong W.K., Park J.H., Lee S.H., Park J.W., Han S.B., Lee D.H. Septic arthritis of the knee joint secondary to adjacent chronic osteomyelitis of the femur in an adult. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2010;18:790–793. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0976-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marsh J.L., Watson P.A., Crouch C.A. Septic arthritis caused by chronic osteomyelitis. Iowa Orthop. J. 1997;17:90–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picillo U., Italian G., Marcialis M.R., Ginolfi F., Abbate G., Tufano M.A. Bilateral femoral osteomyelitis with knee arthritis due to Salmonella enteritidis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Rheumatol. 2001;20:53–56. doi: 10.1007/s100670170104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goergens E.D., McEvoy A., Watson M., Barrett I.R. Acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2005;41:59–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perlman M.H., Patzakis M.J., Kumar P.J., Holton P. The incidence of joint involvement with adjacent osteomyelitis in paediatric patients. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2000;20:40–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paley D., Herzenberg J.E. Intramedullary infections treated with antibiotic cement rods: preliminary results in nine cases. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2002;16:723–729. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner E. Blood and nerve supply of joints. Standford Med. Bull. 1953;11(4):203–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitt S.K. Osteomyelitis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2017;31(2):325–338. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zalavras C.G., Dellamaggiora R., Patzakis M.J., Zachos V., Holtom P.D. Recalcitrant septic knee arthritis due to adjacent osteomyelitis in adults. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2006;451:38–41. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000229336.44524.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang J.S.H., Gold R.H., Bassett L.W., Seeger L.L. Musculoskeletal infection of the extremities: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;166:205–209. doi: 10.1148/radiology.166.1.3336680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karchevsky M., Schweitzer M.E., Morrison W.B., Parellada J.A. MRI findings of septic arthritis and associated osteomyelitis in adults. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2004;182:119–122. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.1.1820119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monsalve J., Kan J.H., Schallert E.K., Bisset G.S., Zhang W., Rosenfeld S.B. Septic arthritis in children: frequency of coexisting unsuspected osteomyelitits and implications of imaging work-up and management. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015;204(6):1289–1295. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hake M.E., Young H., Hak D.J., Stahel P.F., Hammerberg M., Mauffrey C. Local antibiotic therapy strategies in orthopaedic trauma: practical tips and tricks and review of the literature. Injury. 2015;46:1447–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klemm K. Gentamicin-PMMA-beads in treating bone and soft tissue infections. Zentralbl. Chir. 1979;104:934–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans R.P., Nelson C.L. Gentamicin-impregnated polymethylmethacrylate beads compared with systemic antibiotic therapy in the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1993;295:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walenkamp G.H., Kleijn L.L., De Leeuw M. Osteomyelitis treated with gentamicin-PMMA beads: 100 patients followed for 1-12 years. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1998;69(5):518–522. doi: 10.3109/17453679808997790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J.W., Cuellar D.O., Hao J., Seligson D., Mauffrey C. Custom-made antibiotic cement nails: a comparative study of different fabrication techniques. Injury. 2014;45(8):1179–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klemm K. The use of antibiotic-containing bead chains in the treatment of chronic bone infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2001;7:28–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta S., Humphrey J.S., Schenkman D.I., Seaber A.V., Vail T.P. Gentamicin distribution from a collagen carrier. J. Orthop. Res. 1996;14:749–754. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100140511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shyam A.K., Sancheti P.K., Patel S.K., Rocha S., Pradhan C., Patil A. Use of antibiotic cement-impregnated intramedullary nail in treatment of infected non-union of long bones. Indian J. Orthop. 2009;43:396–402. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.55468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mauffrey C., Chaus G.W., Butler N., Young H. MR-compatible antibiotic interlocked nail fabrication for the management of long bone infections: first case report of a new technique. Patient Saf. Surg. 2014;8:14. doi: 10.1186/1754-9493-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]