Abstract

Objective:

Alcohol use is understudied among transgender persons—persons whose sex differs from their gender identity. We compare patterns of alcohol use between Veterans Health Administration (VA) transgender and nontransgender outpatients.

Method:

National VA electronic health record data were used to identify all patients’ last documented Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption (AUDIT-C) screen (October 1, 2009–July 31, 2017). Transgender patients were identified using diagnostic codes. Logistic regression models estimated four past-year primary outcomes: (a) alcohol use (AUDIT-C > 0); (b) unhealthy alcohol use (AUDIT-C ≥ 5); (c) high-risk alcohol use (AUDIT-C ≥ 8); and (d) heavy episodic drinking (HED; ≥6 drinks on ≥1 occasion). Two secondary diagnostic-based outcomes, alcohol use disorder (AUD) and alcohol-specific conditions, were also examined.

Results:

Among 8,872,793 patients, 8,619 (0.10%) were transgender. For transgender patients, unadjusted prevalence estimates were as follows: 52.8% for any alcohol use, 6.6% unhealthy alcohol use, 2.8% high-risk use, 10.4% HED, 8.6% AUD, and 1.3% alcohol-specific conditions. After adjustment for demographic characteristics, transgender patients had lower odds of patient-reported alcohol use but higher odds of alcohol-related diagnoses compared with nontransgender patients. Differences in alcohol-related diagnoses were attenuated after adjustment for comorbid conditions and utilization.

Conclusions:

This is the largest study of patterns of alcohol use among transgender persons and among the first to directly compare patterns to nontransgender persons. Findings suggest nuanced associations with patterns of alcohol use and provide a base for further disparities research to explore alcohol use within the diverse transgender community. Research with self-reported measures of gender identity and sex-at-birth and structured assessment of alcohol use and disorders is needed.

Nearly 1.4 million u.s. adults are transgender (Gates, 2011), an umbrella term encompassing individuals with gender identities that differ from social norms of masculinity or femininity attributed to sex assigned at birth. Transgender persons experience substantial stigma and discrimination and are disproportionately exposed to stressors (Blosnich et al., 2017b), including childhood and adulthood victimization and violence (Stotzer, 2009), housing instability (Grant et al., 2010), and financial insecurity (Conron et al., 2012; Grant et al., 2010). These social determinants are fundamental causes of poor health (Link & Phelan, 1995) and contribute to disparities in health outcomes for transgender populations, including increased rates of HIV and hepatitis C, depression, and suicide mortality (Blosnich et al., 2013, 2014, 2016; Grant et al., 2010). Despite heightened exposure to fundamental causes of poor health and substantial morbidity and mortality, transgender populations remain understudied, particularly with regard to substance use (Institute of Medicine, 2011).

Alcohol use is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States (White et al., 2020). Unhealthy alcohol use (Saitz, 2005)—particularly heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders—increases risk of acute and chronic conditions (GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators, 2018; Rehm & Imtiaz, 2016). Minority populations often experience disparities in patterns of alcohol use (Mulia et al., 2009), but research regarding alcohol use among transgender persons is limited (Gilbert et al., 2018) because of a lack of or unstandardized inclusion of gender identity information in most data sources. Prior studies of alcohol use among transgender persons have largely been conducted in small conveniencebased or regional samples or samples limited to patients with specific health conditions (e.g., HIV) or specific age groups (Benotsch et al., 2016; Blosnich et al., 2016, 2017a, 2017b; Brown & Jones, 2016; Coulter et al., 2015; Garofalo et al., 2006; Horvath et al., 2014; Keuroghlian et al., 2015; Melendez et al., 2006; Reisner et al., 2014; Santos et al., 2014; Testa et al., 2012). These studies have had mixed findings and have generally only investigated a single pattern of alcohol use; most have not included a direct nontransgender comparison group.

National data with indicators of both transgender identification and alcohol use could provide more definitive information about patterns of alcohol use among transgender persons. As the largest integrated health care system in the United States with national electronic health record (EHR) data and a large and growing number of transgender individuals (Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2020; Gates & Herman, 2014; Kauth et al., 2014), the Veterans Health Administration (VA) offers a unique natural laboratory to study patterns of alcohol use in a large, unrecruited sample of transgender patients. VA’s nationwide implementation of routine outpatient screening with the validated Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption (AUDIT-C) questionnaire (Bradley et al., 2006) enables exploration of multiple patterns of alcohol use. Therefore, in a large population of outpatients receiving VA care, we describe patterns of alcohol use among transgender patients and compare patterns to nontransgender patients.

Method

Data source and study sample

EHR and administrative data were extracted from the Corporate Data Warehouse—a relational data warehouse that mirrors VA’s national EHR and links with administrative and clinical data (Souden, 2017). Data were extracted for all patients with one or more documented AUDIT-C screens and an outpatient visit from October 1, 2009, through July 31, 2017. Patients’ most recent documented AUDIT-C screens were included in analyses to reflect the most current sociocultural landscape for transgender persons. The study, including waivers of written consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization, was approved by institutional review boards at the University of Washington, VA Puget Sound, and the University of Pittsburgh.

Measures

Primary independent variable.

Transgender patients were identified using International Classification of Disease, 9th and 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM, respectively) codes (Supplemental Table A), using methods developed and validated at the VA (Blosnich et al., 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017b; Brown & Jones, 2016), and subsequently applied to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Data (Proctor et al., 2016). Patients with documentation of one or more of these codes from start of the Corporate Data Warehouse (January 1, 1999) to study end (July 31, 2017) were considered transgender. Although these methods do not directly assess gender identity, they have high concordance with structured chart review methods for assessing patient transgender status (Blosnich et al., 2018).

Alcohol use outcomes.

Four primary outcomes were measured using data collected from routine clinically administered alcohol screening at the VA with the AUDIT-C, a validated three-item screen for unhealthy alcohol use that assesses the quantity and frequency of past-year average alcohol consumption and frequency of past-year heavy episodic drinking, resulting in scores ranging from 0 (nondrinking) to 12 (very high-risk drinking with high likelihood of adverse outcomes) (Rubinsky et al., 2013). For this study, primary study outcomes included any alcohol use (AUDIT-C > 0), unhealthy alcohol use (AUDIT-C ≥ 5), high-risk alcohol use (AUDIT-C ≥ 8), and any heavy episodic drinking (response greater than “never” to AUDIT-C Question #3, “How often did you have 6 or more drinks on one occasion?”).

Although scores of 4 or higher for men and 3 or higher for women maximize sensitivity and specificity for unhealthy alcohol use in validation studies (Bradley et al., 2003; Bush et al., 1998), the cut-point for unhealthy use was selected because VA has electronic clinical decision support and a performance measure that incentivizes follow-up care for patients with AUDIT-C scores of 5 or higher (Lapham et al., 2012) and because, although we know that a lower cut-point is appropriate in women, there is ambiguity regarding how to measure current sex among transgender patients using administrative data (Burgess et al., 2019). The cut-point for high-risk use was selected because the risk of adverse outcomes increases at this level (Rubinsky et al., 2013), and VA clinical guidelines recommend offering specialty treatment to patients with scores of 8 or higher (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2015b). In addition, although AUDIT-C Question #3 defines heavy episodic drinking differently than the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (≥5 drinks for men, ≥4 drinks for women; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, n.d.), we selected use of AUDIT-C Question #3 as our measure of heavy episodic drinking because it has been validated as a single-item screen in veterans (Bradley et al., 1998, 2003). Two secondary outcomes—any alcohol use disorders and any alcohol-specific conditions—were measured using diagnoses documented in the year before the AUDIT-C (see Supplemental Table A for specific ICD codes).

Covariates.

Fiscal year of AUDIT-C screening was extracted to capture changes in screening practices over time. Demographic covariates were measured at the time of AUDIT-C screening. Age in years at the time of AUDIT-C was categorized into four groups (18–29, 30–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years) consistent with prior categorizations from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (Grant et al., 2015). Race/ethnicity was categorized as Black (non-Hispanic), White (non-Hispanic), Hispanic (any race), other race (non-Hispanic), multiple race (non-Hispanic), and unknown. Financial and other hardship was approximated based on VA copay requirements (VA copay required, no copay required due to disability, no copay required due to means/other, and not assigned); those having no copay required are considered the most disadvantaged. Marital status was defined as divorced/separated, married, never married/single, widowed, or unknown/missing. A measure of EHR-documented gender was also obtained using a data field labeled “gender” in VA’s EHR and defined as “sex of the patient,” which is generally documented by administrators. ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes (Supplemental Table A) documented on the day of or within a year before the AUDIT-C screen were used to measure whether patients had diagnoses included in the validated Charlson co-morbidity index (Charlson et al., 1987, 1994; D’Hoore et al., 1996), hepatitis C, HIV or AIDS, defined consistent with the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (Fultz et al., 2006), and non-alcohol substance use disorders (tobacco, stimulant, opioid, cannabis, hallucinogen, and sedative abuse or dependence, excluding those in remission). Outpatient healthcare utilization was measured as count of outpatient visits (0, 1–3, 4–7, ≥8) in the year before AUDIT-C screen.

Mental health stratification measure.

We measured any mental health diagnoses based on diagnostic codes (Supplemental Table A) documented on the day of or within a year before the AUDIT-C screen for depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), other anxiety disorders, other mood disorders, and serious mental illness (bipolar disorder, psychosis, and/or schizophrenia).

Analyses

Guided by a Generations of Health Disparities framework (Kilbourne et al., 2006), analyses focused on detecting differences (i.e., first-generation disparities research) by comparing a socially distinct vulnerable population (transgender patients) to a less vulnerable comparison population (nontransgender patients). Descriptive analyses summarized patient demographic and clinical characteristics, and all primary and secondary alcohol use outcomes in the full sample and separately for transgender and nontransgender patients. Chi-square tests compared characteristics and outcomes across groups.

Logistic regression models with transgender indicator as the predictor of interest tested the hypothesis (HA1) that patterns of alcohol use differ across groups. Although fundamental cause (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013) and minority stress (Hendricks & Testa, 2012) theories would suggest increased risk for unhealthy alcohol use among transgender relative to nontransgender patients, our hypothesis did not specify directionality based on mixed findings in prior research. Models estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of all outcomes for transgender patients relative to the comparison population. Models also estimated the average prevalence of each outcome for transgender and nontransgender persons using recycled predictions. Standard errors were calculated using the robust sandwich estimator and clustered on the facility in which AUDIT-C screening was conducted.

For each outcome, three covariate-adjusted models were fit with covariates added incrementally. The first was adjusted only for the year of the AUDIT-C screen to account for changing patterns in screening over time. The second was additionally adjusted for demographic characteristics, and the third was further adjusted for comorbid conditions and outpatient healthcare utilization. Because of expected large differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between groups (Brown & Jones, 2016) that may confound but also explain associations of interest, each model was considered to provide a unique contribution. Because patterns of alcohol use are directly influenced by mental health conditions (Sullivan et al., 2011) that are highly prevalent among transgender persons (Blosnich et al., 2016; Brown & Jones, 2016; Grant et al., 2010), mental health diagnoses were considered an a priori effect modifier. Thus, the three incrementally adjusted models were repeated, stratified by any mental health condition. The Holm-Bonferroni sequential correction for multiple tests was applied separately for primary and secondary outcomes to p values for all statistical tests (Holm, 1979). Analyses were conducted using Stata Version 15 statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

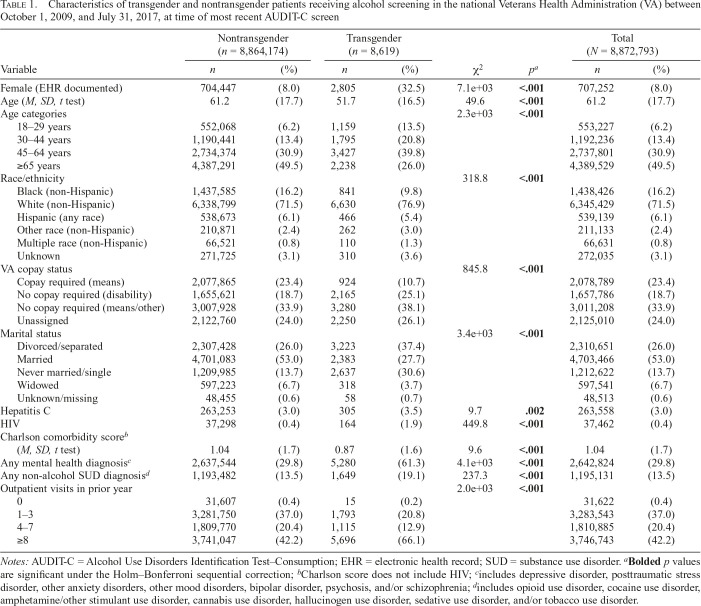

Among 8,872,793 patients who completed an AUDIT-C screen during the study period, 8,619 (0.10%) were transgender. Characteristics of the full population, overall and across groups, are presented in Table 1. Consistent with VA’s patient

Table 1.

Characteristics of transgender and nontransgender patients receiving alcohol screening in the national Veterans Health Administration (VA) between October 1, 2009, and July 31, 2017, at time of most recent AUDIT-C screen

| Nontransgender (n = 8,864,174) |

Transgender (n = 8,619) |

Total (N = 8,872,793) |

||||||

| Variable | n | (%) | (%) | n | χ2 | pa | n | (%) |

| Female (EHR documented) | 704,447 | (8.0) | 2,805 | (32.5) | 7.1e+03 | <.001 | 707,252 | (8.0) |

| Age (M, SD, t test) | 61.2 | (17.7) | 51.7 | (16.5) | 49.6 | <.001 | 61.2 | (17.7) |

| Age categories | 2.3e+03 | <.001 | ||||||

| 18–29 years | 552,068 | (6.2) | 1,159 | (13.5) | 553,227 | (6.2) | ||

| 30–44 years | 1,190,441 | (13.4) | 1,795 | (20.8) | 1,192,236 | (13.4) | ||

| 45–64 years | 2,734,374 | (30.9) | 3,427 | (39.8) | 2,737,801 | (30.9) | ||

| ≥65 years | 4,387,291 | (49.5) | 2,238 | (26.0) | 4,389,529 | (49.5) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 318.8 | <.001 | ||||||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 1,437,585 | (16.2) | 841 | (9.8) | 1,438,426 | (16.2) | ||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 6,338,799 | (71.5) | 6,630 | (76.9) | 6,345,429 | (71.5) | ||

| Hispanic (any race) | 538,673 | (6.1) | 466 | (5.4) | 539,139 | (6.1) | ||

| Other race (non-Hispanic) | 210,871 | (2.4) | 262 | (3.0) | 211,133 | (2.4) | ||

| Multiple race (non-Hispanic) | 66,521 | (0.8) | 110 | (1.3) | 66,631 | (0.8) | ||

| Unknown | 271,725 | (3.1) | 310 | (3.6) | 272,035 | (3.1) | ||

| VA copay status | 845.8 | <.001 | ||||||

| Copay required (means) | 2,077,865 | (23.4) | 924 | (10.7) | 2,078,789 | (23.4) | ||

| No copay required (disability) | 1,655,621 | (18.7) | 2,165 | (25.1) | 1,657,786 | (18.7) | ||

| No copay required (means/other) | 3,007,928 | (33.9) | 3,280 | (38.1) | 3,011,208 | (33.9) | ||

| Unassigned | 2,122,760 | (24.0) | 2,250 | (26.1) | 2,125,010 | (24.0) | ||

| Marital status | 3.4e+03 | <.001 | ||||||

| Divorced/separated | 2,307,428 | (26.0) | 3,223 | (37.4) | 2,310,651 | (26.0) | ||

| Married | 4,701,083 | (53.0) | 2,383 | (27.7) | 4,703,466 | (53.0) | ||

| Never married/single | 1,209,985 | (13.7) | 2,637 | (30.6) | 1,212,622 | (13.7) | ||

| Widowed | 597,223 | (6.7) | 318 | (3.7) | 597,541 | (6.7) | ||

| Unknown/missing | 48,455 | (0.6) | 58 | (0.7) | 48,513 | (0.6) | ||

| Hepatitis C | 263,253 | (3.0) | 305 | (3.5) | 9.7 | .002 | 263,558 | (3.0) |

| HIV | 37,298 | (0.4) | 164 | (1.9) | 449.8 | <.001 | 37,462 | (0.4) |

| Charlson comorbidity scoreb (M, SD, t test) | 1.04 | (1.7) | 0.87 | (1.6) | 9.6 | <.001 | 1.04 | (1.7) |

| Any mental health diagnosisc | 2,637,544 | (29.8) | 5,280 | (61.3) | 4.1e+03 | <.001 | 2,642,824 | (29.8) |

| Any non-alcohol SUD diagnosisd | 1,193,482 | (13.5) | 1,649 | (19.1) | 237.3 | <.001 | 1,195,131 | (13.5) |

| Outpatient visits in prior year | 2.0e+03 | <.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 31,607 | (0.4) | 15 | (0.2) | 31,622 | (0.4) | ||

| 1–3 | 3,281,750 | (37.0) | 1,793 | (20.8) | 3,283,543 | (37.0) | ||

| 4–7 | 1,809,770 | (20.4) | 1,115 | (12.9) | 1,810,885 | (20.4) | ||

| ≥8 | 3,741,047 | (42.2) | 5,696 | (66.1) | 3,746,743 | (42.2) | ||

Notes: AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption; EHR = electronic health record; SUD = substance use disorder.

Bolded p values are significant under the Holm–Bonferroni sequential correction;

Charlson score does not include HIV;

includes depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, other anxiety disorders, other mood disorders, bipolar disorder, psychosis, and/or schizophrenia;

includes opioid use disorder, cocaine use disorder, amphetamine/other stimulant use disorder, cannabis use disorder, hallucinogen use disorder, sedative use disorder, and/or tobacco use disorder.

population (Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2020), the population was largely older adults (mean age = 61.2), male (92.0%), and non-Hispanic White race/ethnicity (71.5%). About half had some indication of financial hardship or disability, and 53% were married.

Relative to the nontransgender population, the transgender population was younger (mean age = 51.7), less likely to be married, and more likely to be non-Hispanic White race/ethnicity and identified as female in the EHR (Table 1). Transgender patients had higher prevalence of hepatitis C and HIV, any mental health condition and any non-alcohol substance use disorder diagnosis, and greater past-year outpatient healthcare utilization, whereas nontransgender patients had a higher mean Charlson comorbidity score.

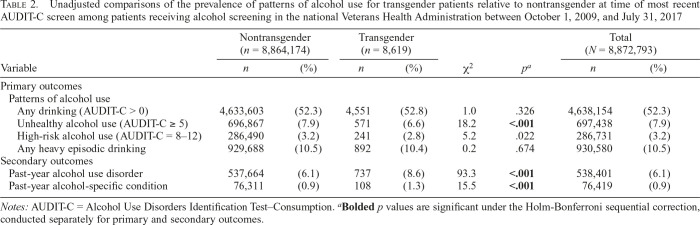

The prevalence of primary and secondary alcohol use outcomes is presented in Table 2. In descriptive group comparisons, transgender patients had significantly lower prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use than nontransgender patients, but significantly higher prevalence of diagnoses for alcohol use disorder and alcohol-specific conditions.

Table 2.

Unadjusted comparisons of the prevalence of patterns of alcohol use for transgender patients relative to nontransgender at time of most recent AUDIT-C screen among patients receiving alcohol screening in the national Veterans Health Administration between October 1, 2009, and July 31, 2017

| Nontransgender (n = 8,864,174) |

Transgender (n = 8,619) |

Total (N = 8,872,793) |

||||||

| Variable | n | (%) | n | (%) | χ2 | pa | n | (%) |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||||

| Patterns of alcohol use | ||||||||

| Any drinking (AUDIT-C > 0) | 4,633,603 | (52.3) | 4,551 | (52.8) | 1.0 | .326 | 4,638,154 | (52.3) |

| Unhealthy alcohol use (AUDIT-C ≥ 5) | 696,867 | (7.9) | 571 | (6.6) | 18.2 | <.001 | 697,438 | (7.9) |

| High-risk alcohol use (AUDIT-C = 8–12) | 286,490 | (3.2) | 241 | (2.8) | 5.2 | .022 | 286,731 | (3.2) |

| Any heavy episodic drinking | 929,688 | (10.5) | 892 | (10.4) | 0.2 | .674 | 930,580 | (10.5) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| Past-year alcohol use disorder | 537,664 | (6.1) | 737 | (8.6) | 93.3 | <.001 | 538,401 | (6.1) |

| Past-year alcohol-specific condition | 76,311 | (0.9) | 108 | (1.3) | 15.5 | <.001 | 76,419 | (0.9) |

Notes: AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption.

Bolded p values are significant under the Holm-Bonferroni sequential correction, conducted separately for primary and secondary outcomes.

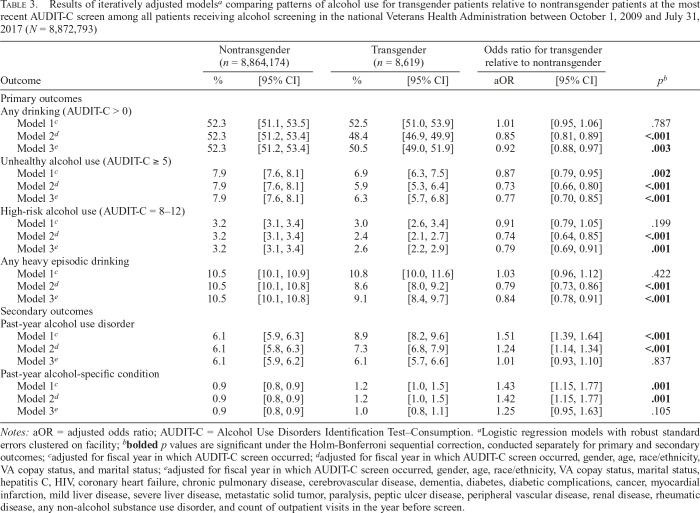

Results of logistic regression models are presented in Table 3. In models adjusted only for year of AUDIT-C screening, transgender patients did not differ from nontransgender patients in rates of any alcohol use, high-risk alcohol use, or any heavy episodic drinking, but the odds ratio of any unhealthy alcohol use was lower for transgender patients relative to nontransgender patients (OR = 0.87, 95% CI [0.79, 0.95]), and results for both secondary outcomes went in the opposite direction (OR = 1.51, 95% CI [1.39, 1.64] for alcohol use disorder and OR = 1.43, 95% CI [1.15, 1.77] for alcohol-specific conditions). Additional adjustment for demographics (Model 2) resulted in a consistent pattern across outcomes, with transgender patients less likely to meet criteria for the four primary outcomes and more likely to have secondary diagnostic outcomes. Further adjustment for comorbid conditions and outpatient healthcare utilization (Model 3) did not alter results substantially for primary outcomes but attenuated observed differences in secondary outcomes.

Table 3.

Results of iteratively adjusted modelsa comparing patterns of alcohol use for transgender patients relative to nontransgender patients at the most recent AUDIT-C screen among all patients receiving alcohol screening in the national Veterans Health Administration between October 1, 2009 and July 31, 2017 (N = 8,872,793)

| Nontransgender (n = 8,864,174) |

Transgender (n = 8,619) |

Odds ratio for transgender relative to nontransgender |

|||||

| Outcome | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | aOR | [95% CI] | pb |

| Primary outcomes | |||||||

| Any drinking (AUDIT-C > 0) | |||||||

| Model 1c | 52.3 | [51.1, 53.5] | 52.5 | [51.0, 53.9] | 1.01 | [0.95, 1.06] | .787 |

| Model 2d | 52.3 | [51.2, 53.4] | 48.4 | [46.9, 49.9] | 0.85 | [0.81, 0.89] | <.001 |

| Model 3e | 52.3 | [51.2, 53.4] | 50.5 | [49.0, 51.9] | 0.92 | [0.88, 0.97] | .003 |

| Unhealthy alcohol use (AUDIT-C ≥ 5) | |||||||

| Model 1c | 7.9 | [7.6, 8.1] | 6.9 | [6.3, 7.5] | 0.87 | [0.79, 0.95] | .002 |

| Model 2d | 7.9 | [7.6, 8.1] | 5.9 | [5.3, 6.4] | 0.73 | [0.66, 0.80] | <.001 |

| Model 3e | 7.9 | [7.6, 8.1] | 6.3 | [5.7, 6.8] | 0.77 | [0.70, 0.85] | <.001 |

| High-risk alcohol use (AUDIT-C = 8–12) | |||||||

| Model 1c | 3.2 | [3.1, 3.4] | 3.0 | [2.6, 3.4] | 0.91 | [0.79, 1.05] | .199 |

| Model 2d | 3.2 | [3.1, 3.4] | 2.4 | [2.1, 2.7] | 0.74 | [0.64, 0.85] | <.001 |

| Model 3e | 3.2 | [3.1, 3.4] | 2.6 | [2.2, 2.9] | 0.79 | [0.69, 0.91] | .001 |

| Any heavy episodic drinking | |||||||

| Model 1c | 10.5 | [10.1, 10.9] | 10.8 | [10.0, 11.6] | 1.03 | [0.96, 1.12] | .422 |

| Model 2d | 10.5 | [10.1, 10.8] | 8.6 | [8.0, 9.2] | 0.79 | [0.73, 0.86] | <.001 |

| Model 3e | 10.5 | [10.1, 10.8] | 9.1 | [8.4, 9.7] | 0.84 | [0.78, 0.91] | <.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||

| Past-year alcohol use disorder | |||||||

| Model 1c | 6.1 | [5.9, 6.3] | 8.9 | [8.2, 9.6] | 1.51 | [1.39, 1.64] | <.001 |

| Model 2d | 6.1 | [5.8, 6.3] | 7.3 | [6.8, 7.9] | 1.24 | [1.14, 1.34] | <.001 |

| Model 3e | 6.1 | [5.9, 6.2] | 6.1 | [5.7, 6.6] | 1.01 | [0.93, 1.10] | .837 |

| Past-year alcohol-specific condition | |||||||

| Model 1c | 0.9 | [0.8, 0.9] | 1.2 | [1.0, 1.5] | 1.43 | [1.15, 1.77] | .001 |

| Model 2d | 0.9 | [0.8, 0.9] | 1.2 | [1.0, 1.5] | 1.42 | [1.15, 1.77] | .001 |

| Model 3e | 0.9 | [0.8, 0.9] | 1.0 | [0.8, 1.1] | 1.25 | [0.95, 1.63] | .105 |

Notes: aOR = adjusted odds ratio; AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption.

Logistic regression models with robust standard errors clustered on facility;

bolded p values are significant under the Holm-Bonferroni sequential correction, conducted separately for primary and secondary outcomes;

adjusted for fiscal year in which AUDIT-C screen occurred;

adjusted for fiscal year in which AUDIT-C screen occurred, gender, age, race/ethnicity, VA copay status, and marital status;

adjusted for fiscal year in which AUDIT-C screen occurred, gender, age, race/ethnicity, VA copay status, marital status, hepatitis C, HIV, coronary heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, diabetes, diabetic complications, cancer, myocardial infarction, mild liver disease, severe liver disease, metastatic solid tumor, paralysis, peptic ulcer disease, peripheral vascular disease, renal disease, rheumatic disease, any non-alcohol substance use disorder, and count of outpatient visits in the year before screen.

Results stratified by any mental health diagnosis (Supplemental Table B) were largely consistent with those of main analyses for primary outcomes regardless of mental health diagnoses. However, there were no longer significant differences in odds of secondary outcomes (past-year alcohol use disorder and past-year alcohol-specific conditions) across groups among those with or without mental health diagnoses.

Last, because little is known regarding the validity of the EHR-based measure of gender for transgender populations (e.g., it may or may not capture current gender identity), we conducted sensitivity analyses repeating Models 2 and 3 without adjustment for EHR-documented gender and stratified by EHR-documented gender. Unstratified models without adjustment for gender (Supplemental Table C) were similar to main findings except that no significant differences between transgender and nontransgender patients were observed in alcohol-related diagnoses in Model 2, although transgender patients had significantly lower odds of alcohol use disorder in Model 3. In models stratified by gender (Supplemental Table D), transgender patients had lower odds of primary outcomes among patients with EHR-documented male gender, whereas transgender patients had higher odds of these outcomes among patients with EHR-documented female gender. Differences in secondary diagnostic outcomes were mostly nonsignificant in adjusted models when stratified by EHR-documented gender, except that transgender patients had significantly higher odds of alcohol use disorder among patients with EHR-documented female gender.

Discussion

In this large national population of nonrecruited VA patients, large numbers of transgender and nontransgender patients had documented alcohol use and unhealthy use. Differences in primary alcohol use outcomes were generally small, with lower odds among transgender patients compared with nontransgender patients after adjustment for demographics or demographics and comorbidity and utilization, whereas secondary diagnostic measures generally went in the opposite direction.

Findings suggest that there may be higher rates of recognized alcohol use disorders and alcohol-related conditions among transgender patients relative to comparators, but significantly lower self-reported alcohol consumption. Further second-generation disparities research (Kilbourne et al., 2006) is needed to explore mechanisms underlying differences identified, as well as opposing directions of differences. Our findings regarding lower levels of primary alcohol use outcomes among transgender patients suggest the possibility that, in this population with multiple heightened vulnerabilities to adverse health behaviors, there may be resiliency to risky patterns of alcohol use. This could be through receipt of inclusive care in the VA, a system in which large structural interventions have been disseminated to improve gender affirming care for transgender patients (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2013; Kauth & Shipherd, 2016). However, because we identified possible higher rates of alcohol use disorders and alcohol-related conditions among transgender patients than comparators (dependent on adjustment), findings may reflect worse outcomes at lower levels of consumption for transgender patients. A similar pattern has been found in health disparities research such that some racial/ethnic minority groups report lower rates of alcohol use than Whites, but more severe consequences of drinking at lower levels (Chartier & Caetano, 2010). Similarly, women may experience greater consequences of alcohol use at lower levels of consumption, including self-reported alcohol use disorder symptoms (Chavez et al., 2012; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 1999; Rubinsky et al., 2013).

Although further research is needed to understand potential reasons for differences in the directions of associations identified, we suggest several possible explanations. First, abstinence from alcohol use is recommended for patients with a history of alcohol use disorders and alcohol-related medical conditions (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2007); therefore, lower prevalence of self-reported alcohol use may reflect patients’ reduced consumption based on clinical recommendations. Specifically, receiving an alcohol-related diagnosis may have triggered subsequent reduction or cessation of drinking, which may explain simultaneously lower reported drinking and higher prevalence of alcohol-related conditions among transgender patients.

Second, these findings may relate to differences in measurement of the outcomes and the ways and settings in which outcomes were ascertained. Specifically, primary outcomes assessed patient-reported past-year alcohol consumption whereas secondary outcomes identified EHR-documented diagnoses for alcohol-related conditions. The AUDIT-C is routinely administered by clinicians during primary care and could be subject to social desirability bias, whereas EHR-documented diagnoses are entered at the provider’s discretion and may be more commonly recognized in some subgroups. It is possible that responses to AUDIT-C are more likely subject to social desirability bias among transgender than nontransgender persons, given substantial stigma experienced by transgender persons (Blosnich et al., 2017b; Grant et al., 2010; Stotzer, 2009) coupled with ubiquitous alcohol-related stigma (Chang et al., 2016; Glass et al., 2014; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013). The AUDIT-C has been validated extensively in nontransgender populations and subpopulations (e.g., Frank et al., 2008) but not among transgender individuals. Similarly, the method of measuring secondary outcomes—based on clinically documented diagnoses—may have influenced observed differences. Diagnoses for alcohol use disorder and alcohol-specific conditions may be more likely in specialty settings, which may be more often accessed by transgender persons than nontransgender persons given high prevalence of mental health conditions. Results of analyses stratified by mental health diagnosis support this, as there were no differences in alcohol-specific diagnoses across groups after stratifying individuals by mental health diagnoses, as do results of models adjusted for comorbidities and utilization in which associations were attenuated.

Third, it is possible that our method of identifying transgender patients through clinically documented diagnoses could result in selection bias, whereby transgender persons with comorbidity seek more services and may be more likely classified as being transgender than those without comorbidity who seek fewer services. This possibility is also supported by our finding that differences were attenuated after adjustment for comorbidities and utilization. Last, although we adjusted for age categories, residual confounding is possible such that age differences contribute to observed differences in outcomes between groups. It is unclear which explanation or combination thereof accounts for findings. Further research is needed to evaluate determinants of alcohol use for transgender individuals overall and relative to comparison groups.

Sensitivity analyses stratified by EHR-documented gender warrant further attention. Our findings suggest that increased risk of unhealthy alcohol use and alcohol use disorder among transgender patients relative to nontransgender patients may differ between transgender women and transgender men. Given that we cannot determine whether EHR-documented gender measures self-identified gender or birth sex for transgender patients, we cannot draw clear conclusions about this from the present study. Future research measuring self-identified gender should examine this question.

Our findings highlight large numbers of patients experiencing unhealthy alcohol use and alcohol use disorders among both transgender and nontransgender groups—and particularly concerning rates of heavy episodic drinking— underscoring the importance of offering universal evidence-based alcohol-related care. Multiple evidence-based clinical interventions help people reduce their drinking, including brief intervention offered to patients screening positive for unhealthy alcohol use and, for persons with alcohol use disorder, behavioral treatments and/or medications (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2007). Because transgender persons have heightened risk for adverse alcohol-related events (e.g., via increased exposure to violence and discrimination, which heighten risk for adverse alcohol-related outcomes, including injury and sexually transmitted infections; Stotzer, 2009), evidence-based alcohol-related care should be targeted to transgender patients with unhealthy alcohol use, in addition to being broadly available, consistent with a vulnerable populations approach (Frohlich & Potvin, 2008). However, alcohol prevention and management has been primarily studied in nontransgender populations. Further research may be needed with transgender persons to obtain guidance for effective patient-centered alcohol-related interventions.

Estimates of prevalence of alcohol use outcomes in this large, nonrecruited population of persons with clinically documented standardized alcohol screening were generally similar to estimates from general population-based samples (Blosnich et al., 2017a; Horvath et al., 2014). Findings comparing alcohol use outcomes among transgender patients to the broader population of nontransgender patients offer multiple contributions—first by building the base of first-generation disparities research on this understudied population, and second by building on prior literature (Gilbert et al., 2018) through exploring multiple patterns of alcohol use in a single study, use of an unrecruited adult sample including a very large sample of transgender patients, and comparison to the broader population of nontransgender patients. As a first-generation disparities study, it can provide a foundation for further intersectional disparities research on alcohol use across gender identity, race, age, and other important characteristics. For instance, future research could examine heterogeneity in alcohol use across transgender persons with lived experience of multiple minority statuses (e.g., further exploration of differences between transgender men and transgender women suggested by secondary analyses in the present study).

Despite these strengths, this study has several limitations. Although large administrative health systems data can equip researchers with the sample sizes necessary to conduct such intersectional research (Glass & Williams, 2018), their use may also limit measurement of key variables. For instance, although our diagnostic transgender indicator has high specificity (Blosnich et al., 2018), it relies on documented diagnoses and not self-reported gender identity. Thus, misclassification and under-identification of transgender patients are possible. Further, this measure does not directly assess gender dysphoria as defined by DSM-5—now a common diagnosis—and does not distinguish between transgender men, transgender women, and nonbinary individuals, subpopulations who may exhibit different patterns of alcohol use (Coulter et al., 2015). Similarly, the VA’s EHR documented gender variable does not discern sex at birth from current gender identity. Our primary measures of alcohol use were derived from the AUDIT-C (Bradley et al., 2007), which is extensively validated but has not been validated in transgender patients, and AUDIT-C’s administration in care settings could result in variable quality (Bradley et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2015). Future studies are needed among transgender patients to validate the AUDIT-C against gold-standard diagnostic instruments for alcohol use disorders. Last, our study may have generalizability limitations. Specifically, it reflects information from persons who are engaged in VA health care, a population that tends to be older and have higher proportions of male and White patients compared with the general population. Further, transgender VA patients, specifically, may receive more routine healthcare, and therefore be more likely to receive diagnoses, compared with transgender nonveterans or transgender veterans who do not use the VA. Transgender VA patients may also have different lived experiences that may affect alcohol use (e.g., greater likelihood of experiencing certain types of trauma than transgender nonveterans, such as military sexual trauma and anti-transgender Department of Defense policies (Brown & Jones, 2016; Elders et al., 2015; Embser-Herbert, 2020).

Nonetheless, this is the largest study to date to investigate patterns of alcohol use among transgender patients and to compare patterns to the larger population of nontransgender patients. Findings highlight large numbers of patients experiencing unhealthy alcohol use in both nontransgender and transgender groups and build on an emerging literature investigating alcohol use in this important and understudied population. This study provides a base for further first-generation disparities - community and second-generation research to identify mechanisms underlying differences identified in the present study. Because of disproportionate exposure to social stressors and adverse health outcomes with which the intersection of unhealthy alcohol use is particularly risky, findings of high numbers of transgender patients experiencing unhealthy alcohol use in the present study also suggest a need for regular intervention for unhealthy alcohol use with this population. Patient-centered research may be needed to build the evidence base for such interventions in this diverse, understudied population.

Footnotes

This study was funded by Grant R21 AA025973 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) to the University of Washington (Emily C. Williams/John R. Blosnich, principal investigators). Ms. Frost is supported by a predoctoral training award from the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Research and Development Service. Dr. Glass is supported by a career development award from NIAAA (K01 AA023859). This work was supported in part with resources and the use of facilities at the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, WA. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The opinions expressed in this work are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions, funders, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Benotsch E. G., Zimmerman R. S., Cathers L., Pierce J., McNulty S., Heck T., Snipes D. J. Non-medical use of prescription drugs and HIV risk behaviour in transgender women in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2016;27:776–782. doi: 10.1177/0956462415595319. 10.1177/0956462415595319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J. R., Brown G. R., Shipherd J. C., Kauth M., Piegari R. I., Bossarte R. M. Prevalence of gender identity disorder and suicide risk among transgender veterans utilizing Veterans Health Administration care. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:e27–e32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301507. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J. R., Brown G. R., Wojcio S., Jones K. T., Bossarte R. M. Mortality among veterans with transgender-related diagnoses in the Veterans Health Administration, FY2000-2009. LGBT Health. 2014;1:269–276. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0050. 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J. R., Cashy J., Gordon A. J., Shipherd J. C., Kauth M. R., Brown G. R., Fine M. J. Using clinician text notes in electronic medical record data to validate transgender-related diagnosis codes. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2018;25:905–908. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy022. 10.1093/jamia/ocy022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J. R., Lehavot K., Glass J. E., Williams E. C. Differences in alcohol use and alcohol-related health care among transgender and nontransgender adults: Findings from the 2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017a;78:861–866. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.861. 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J. R., Marsiglio M. C., Dichter M. E., Gao S., Gordon A. J., Shipherd J. C., Fine M. J. Impact of social determinants of health on medical conditions among transgender veterans. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2017b;52:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.12.019. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J. R., Marsiglio M. C., Gao S., Gordon A. J., Shipherd J. C., Kauth M., Fine M. J. Mental health of transgender veterans in US states with and without discrimination and hate crime legal protection. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106:534–540. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302981. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K. A., Bush K. R., Epler A. J., Dobie D. J., Davis T. M., Sporleder J. L. Two brief alcohol-screening tests from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163:821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K. A., Bush K. R., McDonell M. B., Malone T., Fihn S. D. & the Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project. Screening for problem drinking: Comparison of CAGE and AUDIT. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13:379–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00118.x. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K. A., DeBenedetti A. F., Volk R. J., Williams E. C., Frank D., Kivlahan D. R. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1208–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K. A., Lapham G. T., Hawkins E. J., Achtmeyer C. E., Williams E. C., Thomas R. M., Kivlahan D. R. Quality concerns with routine alcohol screening in VA clinical settings. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;26:299–306. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1509-4. 10.1007/s11606-010-1509-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K. A., Williams E. C., Achtmeyer C. E., Volpp B., Collins B. J., Kivlahan D. R. Implementation of evidence-based alcohol screening in the Veterans Health Administration. American Journal of Managed Care. 2006;12:597–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. R., Jones K. T. Mental health and medical health disparities in 5135 transgender veterans receiving healthcare in the Veterans Health Administration: A case-control study. LGBT Health. 2016;3:122–131. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0058. :10.1089/lgbt.2015.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess C., Kauth M. R., Klemt C., Shanawani H., Shipherd J. C. Evolving sex and gender in electronic health records. Federal Practitioner. 2019;36:271–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K., Kivlahan D. R., McDonell M. B., Fihn S. D., Bradley K. A. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J., Dubbin L., Shim J.2016Negotiating substance use stigma: The role of cultural health capital in provider-patient interactions Sociology of Health & Illness 3890–108.10.1111/1467-9566.12351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson M., Szatrowski T. P., Peterson J., Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1994;47:1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson M. E., Pompei P., Ales K. L., MacKenzie C. R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K., Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33:152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez L. J., Williams E. C., Lapham G., Bradley K. A. Association between alcohol screening scores and alcohol-related risks among female Veterans Affairs patients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:391–400. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.391. 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conron K. J., Scott G., Stowell G. S., Landers S. J. Transgender health in Massachusetts: Results from a household probability sample of adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:118–122. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300315. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter R. W., Blosnich J. R., Bukowski L. A., Herrick A. L., Siconolfi D. E., Stall R. D. Differences in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems between transgender- and nontransgender-identified young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;154:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.006. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hoore W., Bouckaert A., Tilquin C. Practical considerations on the use of the Charlson comorbidity index with administrative data bases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1996;49:1429–1433. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00271-5. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs. Providing health care for transgender and intersex veterans (VHA Directive 2013–003) 2013. Retrieved from https://www.birmingham.va.gov/docs/LGBT_Healthcare.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of substance use disorders. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADoDSUDCPGRevised22216.pdf.

- Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. 2020 VA Utilization Profile FY 2017. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Quickfacts/VA_Utilization_Profile_2017.pdf.

- Elders M. J., Brown G. R., Coleman E., Kolditz T. A., Steinman A. M. Medical aspects of transgender military service. Armed Forces and Society. 2015;41:199–220. 10.1177/0095327X14545625. [Google Scholar]

- Embser-Herbert M. “Welcome! Oh, wait…” Transgender military service in a time of uncertainty. Sociological Inquiry. 2020;90:405–429. 10.1111/soin.12329. [Google Scholar]

- Frank D., DeBenedetti A. F., Volk R. J., Williams E. C., Kivlahan D. R., Bradley K. A. Effectiveness of the AUDIT-C as a screening test for alcohol misuse in three race/ethnic groups. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:781–787. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0594-0. 10.1007/s11606-008-0594-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich K. L., Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: The inequality paradox: The population approach and vulnerable populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:216–221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fultz S. L., Skanderson M., Mole L. A., Gandhi N., Bryant K., Crystal S., Justice A. C. Development and verification of a “virtual” cohort using the National VA Health Information System. Medical Care. 2006;44(Supplement 2):S25–S30. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223670.00890.74. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000223670.00890.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R., Deleon J., Osmer E., Doll M., Harper G. W. Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: Exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.023. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates G. J. How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; 2011. Retrieved from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/how-many-people-lgbt. [Google Scholar]

- Gates G. J., Herman J. L. Transgender military service in the United States. The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; 2014. Retrieved from https://sfcommunityhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Transgender-Military-Service-May-2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators(2018Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 The Lancet 3921015–1035.10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31310-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P. A., Pass L. E., Keuroghlian A. S., Greenfield T. K., Reisner S. L. Alcohol research with transgender populations: A systematic review and recommendations to strengthen future studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2018;186:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.01.016. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass J. E., Williams E. C. The future of research on alcohol health disparities: A health services research perspective. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2018;79:322–324. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.322. 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass J. E., Williams E. C., Bucholz K. K. Psychiatric comorbidity and perceived alcohol stigma in a nationally representative sample of individuals with DSM-5 alcohol use disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:1697–1705. doi: 10.1111/acer.12422. 10.1111/acer.12422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Goldstein R. B., Saha T. D., Chou S. P., Jung J., Zhang H., Hasin D. S. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. M., Mottet L. A., Tanis J., Herman J. L., Harrison J., Keisling M. National transgender discrimination survey report on health and health care. National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. 2010. Retrieved from https://cancer-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/National_Transgender_Discrimination_Survey_Report_on_health_and_health_care.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler M. L., Phelan J. C., Link B. G. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks M. L., Testa R. J. Research and Practice. Vol. 43. Professional Psychology; 2012. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model; pp. 460–467. 10.1037/a0029597. [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath K. J., Iantaffi A., Swinburne-Romine R., Bockting W. A comparison of mental health, substance use, and sexual risk behaviors between rural and non-rural transgender persons. Journal of Homosexuality. 2014;61:1117–1130. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2014.872502. 10.1080/00918369.2014.872502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. 2011. Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13128/the-health-of-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-people-building. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauth M. R., Shipherd J. C. Transforming a system: Improving patient-centered care for sexual and gender minority veterans. LGBT Health. 2016;3:177–179. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0047. 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauth M. R., Shipherd J. C., Lindsay J., Blosnich J. R., Brown G. R., Jones K. T. Access to care for transgender veterans in the Veterans Health Administration: 2006-2013. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(Supplement 4):S532–S534. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302086. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keuroghlian A. S., Reisner S. L., White J. M., Weiss R. D. Substance use and treatment of substance use disorders in a community sample of transgender adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;152:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.04.008. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne A. M., Switzer G., Hyman K., Crowley-Matoka M., Fine M. J. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: A conceptual framework. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:2113–2121. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham G. T., Achtmeyer C. E., Williams E. C., Hawkins E. J., Kivlahan D. R., Bradley K. A. Increased documented brief alcohol interventions with a performance measure and electronic decision support. Medical Care. 2012;50:179–187. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35743. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B. G., Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:80–94. 10.2307/2626958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez R. M., Exner T. A., Ehrhardt A. A., Dodge B., Remien R. H., Rotheram-Borus M.-J. National Institute of Mental Health Healthy Living Project Team. Health and health care among male-to-female transgender persons who are HIV positive. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1034–1037. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042010. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N., Ye Y., Greenfield T. K., Zemore S. E. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism(n.d.Drinking levels defined Retrieved from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Are women more vulnerable to alcohol’s effects? Alcohol Alert. 1999 No. 46. Retrieved from https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa46.htm.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide. 2007. updated 2005 edition). Retrieved from https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/practitioner/cliniciansguide2005/guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor K., Haffer S. C., Ewald E., Hodge C., James C. V. Identifying the transgender population in the Medicare program. Transgender Health. 2016;1:250–265. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0031. 10.1089/trgh.2016.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J., Imtiaz S. A narrative review of alcohol consumption as a risk factor for global burden of disease. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2016;11:37. doi: 10.1186/s13011-016-0081-2. 10.1186/s13011-016-0081-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S. L., White J. M., Mayer K. H., Mimiaga M. J. Sexual risk behaviors and psychosocial health concerns of female-to-male transgender men screening for STDs at an urban community health center. AIDS Care. 2014;26:857–864. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.855701. 10.1080/09540121.2013.855701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsky A. D., Dawson D. A., Williams E. C., Kivlahan D. R., Bradley K. A. AUDIT-C scores as a scaled marker of mean daily drinking, alcohol use disorder severity, and probability of alcohol dependence in a U.S. general population sample of drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:1380–1390. doi: 10.1111/acer.12092. 10.1111/acer.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352:596–607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042262. 10.1056/NEJMcp042262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos G.-M., Rapues J., Wilson E. C., Macias O., Packer T., Colfax G., Raymond H. F. Alcohol and substance use among transgender women in San Francisco: Prevalence and association with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2014;33:287–295. doi: 10.1111/dar.12116. 10.1111/dar.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souden M. Overview of VA data, information systems, national databases and research uses. 2017. Retrieved from https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/2376-notes.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Stotzer R. Violence against transgender people: A review of United States data. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:170–179. 10.1016/j.avb.2009.01.006. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan L. E., Goulet J. L., Justice A. C., Fiellin D. A. Alcohol consumption and depressive symptoms over time: A longitudinal study of patients with and without HIV infection. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;117:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.014. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa R. J., Sciacca L. M., Wang F., Hendricks M. L., Goldblum P., Bradford J., Bongar B. Research and Practice. Vol. 43. Professional Psychology; 2012. Effects of violence on transgender people; pp. 452–459. 10.1037/a0029604. [Google Scholar]

- White A. M., Castle I. P., Hingson R. W., Powell P. A. Using death certificates to explore changes in alcohol-related mortality in the United States, 1999 to 2017. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2020;44:178–187. doi: 10.1111/acer.14239. 10.1111/acer.14239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E. C., Achtmeyer C. E., Thomas R. M., Grossbard J. R., Lapham G. T., Chavez L. J., Bradley K. A. Factors underlying quality problems with alcohol screening prompted by a clinical reminder in primary care: A multi-site qualitative study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2015;30:1125–1132. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3248-z. 10.1007/s11606-015-3248-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]