1. Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is primarily a febrile respiratory illness first documented in December 2019 in Wuhan, China that was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020 [1]. At the time of this writing COVID 19 infections have impacted 191 counties, and the death toll stands at 1,488,513 [2]. COVID-19 infection is known to cause coagulopathy and an inflammatory state [3], but there are few case reports involving COVID-19 related spontaneous bleeding outside of disseminated intravascular coagulation [3]. To date there has only been a single case report of pituitary apoplexy in the setting of COVID-19; this was in a pregnant woman, which is a known risk factor for apoplexy [4,5]. Here, we present a case of pituitary apoplexy in the setting of COVID-19 infection with no such risk factors. (See Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3.)

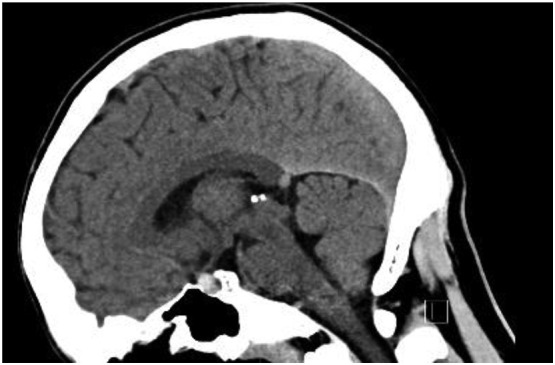

Fig. 1.

Non-Contrast CT Head showing small hyperdense blood collection in the sella turcica, measuring 7 mm × 8 mm × 8 mm, with mild upward deflection on the pituitary infundibulum.

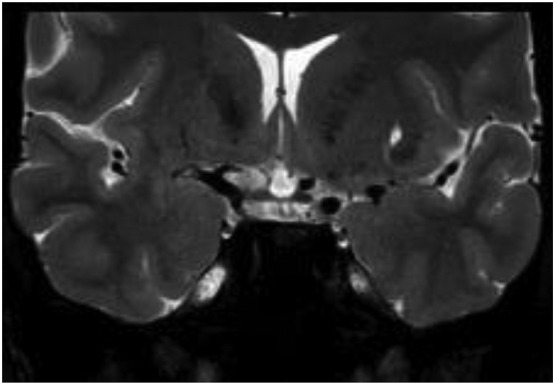

Fig. 2.

Coronal T1 MRI revealing hyperintense 7.5mm pituitary mass with suprasellar extension and mild compression of the optic chiasm.

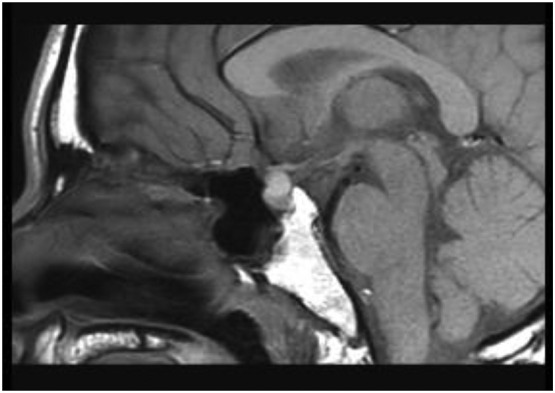

Fig. 3.

Saggital T1 MRI revealing hyperintense 7.5mm pituitary mass with suprasellar extension and mild compression of the optic chiasm.

1.1. Case

A 35-year-old previously healthy male presented to the ED for three days of sharp, retro-orbital headache and neck stiffness. The patient developed upper respiratory tract infection symptoms four days prior to arrival, including fevers, dysgeusia, anosmia, increased sputum production. Vitals were as follows: blood pressure 142/89, heart rate 117, respiratory rate 20, oxygen saturation 95%, and temperature of 101.4 °F. Physical exam revealed a well-developed, diaphoretic male with a normal visual and neurologic examination. CT of the head was obtained and revealed a small hyper-dense blood collection within the Sella measuring 7 mm × 8 mm × 8 mm, not exhibiting mass effect on the optic chiasm, and without evidence of other subarachnoid hemorrhage. The patient was covered empirically with antibiotics for central infection and community acquired pneumonia, given the lobular consolidation noted on chest x-ray. He was confirmed positive for COVID-19 by nasopharyngeal PCR swab. Laboratory evaluation demonstrated normal cell line counts with elevated inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP) and liver function tests (ALT 293, AST 141, LDH 318). Neurosurgery was consulted and the patient was admitted to the ICU. On Hospital Day 1 patient received another head CT which revealed slight worsening of the bleed; MRI later confirmed hemorrhagic pituitary microadenoma consistent with pituitary apoplexy. Additionally, during hospitalization the patient developed pancytopenia, which has been previously exhibited in COVID-19 infection [3]. Hormone testing was unrevealing, the remainder of his hospitalization was unremarkable, and the patient was discharged with endocrinology follow up in place.

2. Discussion

Pituitary apoplexy is a rare neurological and endocrine emergency defined by hemorrhage or infarction of the pituitary gland. Risk factors for apoplexy include pregnancy, post-partum state, trauma, hypertension, and coagulopathy [6,7]. Presentation usually occurs in the 5th to 6th decade of life [6,7]. None of the former was present in our patient. Presentation can vary widely, with symptoms ranging from nausea, vomiting, and headache to more alarming findings of decreased visual acuity, visual field defects, altered level of consciousness, and meningeal signs [6,8]. Such symptoms are relatively non-specific, and the differential broadens to include sub-arachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis, temporal arteritis, encephalopathy, and intracranial hemorrhage [6].

Emergency management of apoplexy is centered around resuscitation. In patients that are hypotensive consider early corticosteroids in order to maintain hemodynamic stability [[8], [9], [10]] as secondary adrenal insufficiency may occur in two-thirds of patients with pituitary tumor apoplexy [8,10,11]. Currently, there is controversy surrounding the optimal course for these patients. Pituitary function should be assessed with hormone assays for future management [6,10]. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, coagulopathy and electrolyte imbalances should be addressed; any evidence of altered level of consciousness or changes to visual field or acuity should prompt immediate surgical evaluation [6,10].

Typical COVID-19 infections are associated with lung injury as well as proinflammatory and thrombotic states such as pulmonary embolus [3]. To date, there are few reports of spontaneous bleeding or neurological manifestations in the setting of COVID-19, although myelitis and acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy have been reported [12,13]. While apoplexy has been linked to increases in ICP caused by coughing and sneezing [14], there is emerging literature on bleeding diathesis due to COVID-19. This case demonstrates that, even in the setting of a known or presumed diagnosis, clinical awareness and identification of potential complications may help avoid anchoring bias and expedite appropriate care.

3. Conclusion

This case demonstrates an uncommon, though potentially lethal, presentation of COVID-19. While headache is not an uncommon presentation in acute viral infections, this case presents a new concern that may warrant neuraxial imaging of patients suspected of having COVID-19 infections in the setting of headache. COVID-19 infections raise concern for CNS involvement and this case demonstrates potentially missed alternative diagnoses that require specialized care. Further research into the prevalence of CNS hemorrhage and COVID-19 infection will further inform this discussion. When encountering a patient suspected of COVID-19 and an atypical headache in the emergency department, the provider should consider advanced imaging for potential intracranial hemorrhage.

Sources of support

None.

Prior presentations

None

Declaration of Competing Interest

The views expressed in this case report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States Government. We are military service members. This work was prepared as part of our official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a United States Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the United States Government as part of that person's official duties.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Announcement New ICD 10 Code for Coronavirus 2 20 2020. 2020. [Accessed 2 Dec 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 2.COVID 19 Map. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center; 2020 coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. [Accessed 2 Dec 2020].

- 3.Chan Noel C., Weitz Jeffrey I. COVID-19 coagulopathy, thrombosis, and bleeding. Blood. 2020;136(4):381–383. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murad-Kejbou S., Eggenberger E. Pituitary apoplexy: evaluation, management, and prognosis. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov;20(6):456–461. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283319061. 19809320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan J.L., Gregory K.D., Smithson S.S., Naqvi M., Mamelak A.N. Pituitary apoplexy associated with acute COVID-19 infection and pregnancy. Pituitary. 2020;23(6):716–720. doi: 10.1007/s11102-020-01080-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranabir S., Baruah M.P. Pituitary apoplexy. Ind. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;15(Suppl 3(Suppl3)) doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.84862. S188-S196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed M., Rifai A., Al-Jurf M., Akhtar M., Woodhouse N. Classical pituitary apoplexy presentation and a follow-up of 13 patients. Horm. Res. 1989;31(3):125–132. doi: 10.1159/000181101. 2744725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briet C., Salenave S., Bonneville J.F., Laws E.R., Chanson P. Pituitary apoplexy. Endocr. Rev. 2015 Dec;36(6):622–645. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1042. 26414232 Epub 2015 Sep 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veldhuis J.D., Hammond J.M. Endocrine function after spontaneous infarction of the human pituitary: report, review, and reappraisal. Endocr. Rev. 1980 Winter;1(1):100–107. doi: 10.1210/edrv-1-1-100. 6785084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barkhoudarian G., Kelly D.F. Pituitary apoplexy. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2019 Oct;30(4):457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2019.06.001. 31471052 Epub 2019 Aug 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oelkers W. Adrenal insufficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996 Oct 17;335(16):1206–1212. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610173351607. 8815944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long A., Grimaldo F. Spontaneous hemopneumothorax in a patient with COVID-19: A case report [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 30] Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.07.065. S0735–6757(20)30660–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jasti M., Nalleballe K., Dandu V., Onteddu S. A review of pathophysiology and neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19. J. Neurol. 2020 Jun;3:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09950-w. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32494854; PMCID: PMC7268182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bi Wenya Linda, Dunn Ian F., Laws Edward R., Jr. Pituitary apoplexy. Endocrine. 2015;48:69–75. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0359-y. 26 July 2014. Accessed 4 February 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]