Abstract

Although post–kidney transplant (KT) wound complications are associated with elevated body mass index (BMI), BMI is not an accurate surrogate of obesity. On the other hand, subcutaneous depth (SQD) measurement is a direct marker of truncal obesity. We examined outcomes of differing intraoperative SQD measurements in 113 KT-only recipients over 20 months. Recipients’ median age was 51 years; median BMI, 28 kg/m2; and mean SQD, 2.9 cm. Patients were stratified into groups of SQD ≤2.5 cm, >2.5–5 cm, and >5 cm. An SQD of >2.5 to 5 cm correlated with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 (obesity) and an SQD >5 cm correlated with a BMI >35 kg/m2 (severe obesity). Degree of SQD was not associated with more frequent technical complications such as fascial dehiscence, lymphocele formation, renal artery thrombosis/stenosis, urine leak, or ureteral stenosis. However, an SQD >2.5 cm was a risk factor for requiring a wound vacuum-assisted closure device. There was no difference in graft or patient survival among the three SQD groups. Obesity, as measured directly by SQD, was not associated with increased technical complications or poor outcomes after KT. As expected, there was a higher incidence of wound complications in the higher SQD groups requiring intervention.

Keywords: abdominal fat, kidney transplantation, nephrology, obesity, postoperative complication, wound vacuum-assisted closure

Surgical complications after kidney transplantation (KT) such as renal vein thrombosis and urine leak are well documented despite their low incidence.1,2 Wound complications, especially surgical site infections (SSI), pose a much smaller risk of graft loss but comprise the majority of post-KT surgical complications. Additionally, these complications consume valuable resources including prolonged antibiotic therapy, wound care materials, and operating room expenses. A well-documented risk factor for wound complications in KT patients is immunosuppression exposure, including induction and maintenance therapy.3–9 Obesity, as evaluated by body mass index (BMI), has also been associated with increased wound complications in KT.10–15 However, BMI has not been shown to be an accurate surrogate of body fat composition or body habitus and may be overestimated in men, the elderly, and those within an intermediate BMI range.16 Additionally, BMI has been shown to be inferior in predicting SSI compared with morphometric subcutaneous fat measurements in the general surgical population.17,18 To our knowledge, there has not been an investigation using direct measurement of subcutaneous fat to forecast postoperative complications in KT. In this study, we sought to determine the effect of incisional subcutaneous depth (SQD) on KT outcomes.

METHODS

With institutional review board approval, we prospectively collected data on kidney-only transplant patients, with both deceased and living donors, over a 20-month period at our transplant center. Measurements were not recorded in three patients, and thus they were excluded from the study.

In accordance with operating room protocol, excess hair on the abdomen was clipped, and an alcohol-based cleanser was used. Preoperative Surgical Care Improvement Project antibiotics (cefazolin or clindamycin in β-lactam allergic patients) were administered within 1 hour of surgical incision. Per our protocol on select recipients, induction therapy with a single dose of alemtuzumab (Campath) or the first of three doses of antithymocyte globulin rabbit (Thymoglobulin, 1.5 mg/kg) was administered at the time of surgery or within the first 24 hours after transplant. Our immunosuppression protocol is tacrolimus based, along with mycophenolic acid and rapidly weaning doses of intravenous methylprednisolone followed by conversion to oral prednisone.

All patients received a Gibson incision in either the right or left lower quadrant. Muscle-sparing techniques were utilized for retroperitoneal exposure of the iliac vessels and bladder. SQD was measured intraoperatively at the midpoint of the lateral aspect of the incision, from the fascia to the skin, and was rounded to the closest 0.5 cm (Figure 1). At completion of the transplant, the skin was reapproximated with staples, which were routinely removed 2 to 3 weeks postoperatively. Delayed graft function was defined as the requirement for dialysis within 7 days after transplant.

Figure 1.

Subcutaneous depth measurements from the fascia to skin level in a kidney transplant recipient, measured as 6.5 cm.

Patients were followed for complications for 90 days posttransplant. The criteria for placement of negative pressure vacuum wound-assisted closure (wVAC) therapy included (1) the presence of a wound infection, (2) excessive and/or prolonged serous wound drainage, and (3) delayed wound healing characterized by skin nonunion or significant subcutaneous tissue exposure before or after skin staple removal. Patients with wVACs were followed in our transplant clinic and/or at our established hospital wound care center. The number of negative pressure wound therapy days was recorded from the time of placement to the time of discontinuation. KCI V.A.C.® therapy was utilized in all patients requiring negative pressure wound therapy.

Preoperative data collected included patient gender, age, BMI, presence of diabetes, hypertension, panel reactive antibody, pretransplant dialysis, and history of prior transplantation. Intraoperative data collected included donor type (cadaveric vs living donor), donation after cardiac death donors, kidney donor profile index, SQD, and cold and warm ischemia time. Posttransplant complications analyzed included delayed graft function, wound infection, dehiscence, lymphocele formation, renal artery thrombosis/stenosis, urine leak, ureteral stenosis, and need for wVAC. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables. A chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Patient survival and graft failure rates were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves, and log-rank test was used to perform group comparison between patients in all three SQD groups. For all statistical testing, significance was defined as a P value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed in R (version 3.5.2).

RESULTS

From April 2016 to December 2017, we performed 116 isolated KT at our center. Our case series included 113 transplants (93 cadaveric, 20 living donor) in 47 female and 66 male recipients. The median age of the recipients was 51 years, with a median BMI of 28.0 kg/m2 (range 17.0 – 38.2). The mean SQD of our recipients was 2.9 cm (range 0.5–7 cm). Patients were analyzed according to SQD where groups were ≤2.5 cm (n = 54), >2.5 to 5 cm (n = 49), and >5 cm (n = 10). Table 1 outlines preoperative and perioperative characteristics, complications, and immediate postoperative outcomes for the three groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative factors in patients with a subcutaneous depth ≤2.5, >2.5 to 5, and >5 cm

| Factor | Subcutaneous depth (cm) |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤2.5 (N = 54) | >2.5 to 5 (N = 49) | >5 (N = 10) | ||

| Age (years) | 48.5 | 52.0 | 54.0 | 0.219 |

| Men | 36 (67%) | 27 (55%) | 3 (30%) | 0.685 |

| Diabetes | 13 (24%) | 21 (43%) | 4 (40%) | 0.110 |

| Hypertension | 48 (89%) | 41 (84%) | 8 (80%) | 0.612 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 24.2 | 30.0 | 35.6 | <0.001 |

| Cadaveric donor | 42 (78%) | 41 (84%) | 10 (100%) | 0.227 |

| DCD donor | 7 (13%) | 8 (16%) | 2 (20%) | 0.733 |

| KDPI (%) | 33% | 33% | 43% | 0.731 |

| Cold ischemia time (min) | 881 | 1050 | 1082 | 0.296 |

| Warm ischemia time (min) | 29.5 | 31.0 | 34.0 | 0.386 |

| Length of stay (days)b | 3.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 0.043 |

| Lymphocele | 0 (0%) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.210 |

| Renal artery stenosis/thrombosis | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 |

| Ureteral stricture | 2 (4%) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.792 |

| Ureteral leak | 1 (2%) | 4 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.287 |

| Fascial dehiscence | 3 (6%) | 7 (14%) | 1 (10%) | 0263 |

| Wound infection | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 |

| Wound vac placementb | 6 (11%) | 18 (37%) | 4 (40%) | 0.004 |

| Delayed graft function | 4 (7%) | 4 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 |

| 30-day readmission | 23 (43%) | 16 (33%) | 3 (30%) | 0.525 |

Group 1 vs Group 2 (P = 0.003) and Group 1 vs Group 3 (P = 0.042) were the significant comparison groups.

Group 1 vs Group 2 (P = 0.041) was the only significant comparison group.

DCD, donation after cardiac death; KDPI, kidney donor profile index. Data presented as n (%) or median.

Overall, there was a 42% complication rate, including cases of wound infection (3), lymphocele formation (3), fascial dehiscence (11), renal artery stenosis or thrombosis (3), ureteral stricture (5), urine leak (5), and requirement for wVAC therapy (28). Complications were more common in older patients (P = 0.003) and in recipients with a higher BMI (29.2 vs 26.6 kg/m2, P = 0.033) (Table 2). There was a trend for more complications in patients with a greater SQD (P = 0.057). Pretransplant dialysis, time on dialysis prior to KT, induction therapy, and a previous transplant were not risk factors for complications, nor was donor type. Patients who had a complication had a higher likelihood of 30-day readmission (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of perioperative factors in kidney transplant patients with a postoperative technical complication*

| Factor | No complications (N = 66) | Complications (N = 47) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48.0 | 55.0 | 0.003 |

| Sex (male) | 37 (56%) | 29 (62%) | 0.685 |

| Diabetes | 18 (27%) | 20 (43%) | 0.136 |

| Hypertension | 56 (85%) | 41 (87%) | 0.932 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 | 29.2 | 0.033 |

| Previous transplant | 16 (24%) | 5 (11%) | 0.112 |

| Pretransplant dialysis | 61 (92%) | 44 (94%) | 1.000 |

| Length on dialysis (days) | 1905 | 1910 | 1.000 |

| Induction therapy | 41 (62%) | 37 (79%) | 0.094 |

| Deceased donor | 53 (80%) | 40 (85%) | 0.682 |

| DCD donor | 8 (12%) | 9 (19%) | 0.445 |

| Subcutaneous depth (cm) | 2.50 | 3.00 | 0.057 |

| Cold ischemia time (min) | 894 | 1055 | 0.102 |

| Warm ischemia time (min) | 30.0 | 30.0 | 0.954 |

| Delayed graft function | 4 (6%) | 4 (9%) | 0.717 |

| 30-day readmission | 13 (20%) | 29 (62%) | <0.001 |

Data presented as n (%) or median. BMI indicates body mass index, DCD, donation after cardiac death.

The rate of technical complications was not different among the three groups, but patients with an SQD >2.5 cm were more likely to require a wVAC. Overall, the mean duration of wVAC therapy for all patients was 45.5 days. As expected, patients with greater SQD depth were more likely to have a higher BMI (P < 0.001). Although implantation (warm ischemia time) took longer in patients with a greater SQD depth, the difference between groups was not statistically significant. The rate of delayed graft function also was not different across all SQD groups.

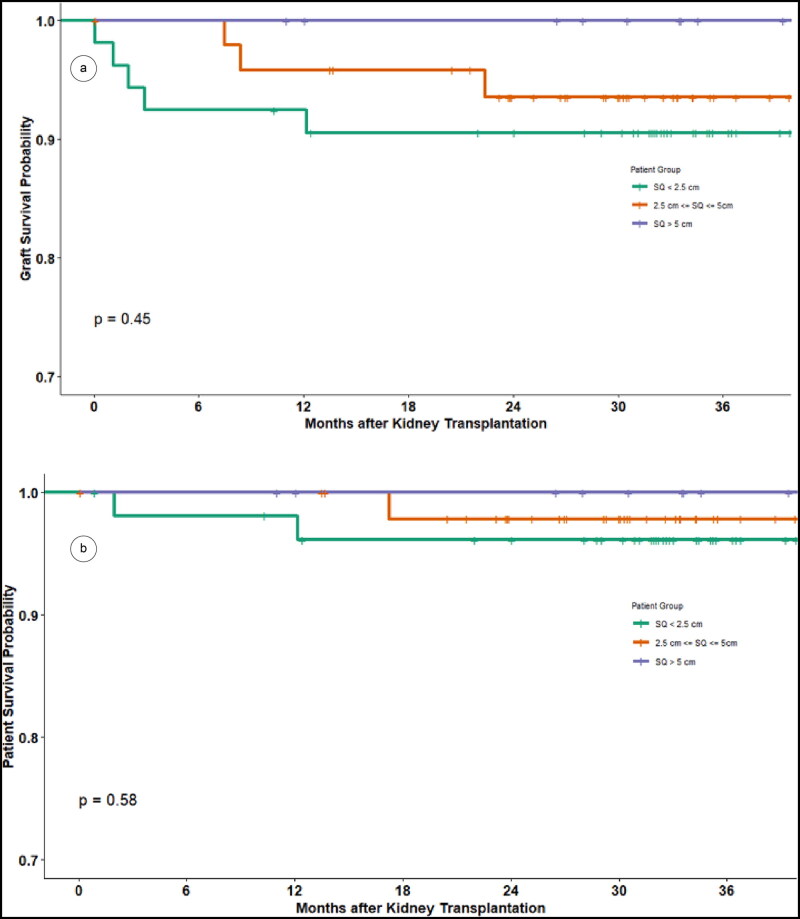

The average length of stay for all patients was 4.4 days, with the SQD ≤2.5 cm group having a significantly shorter length of stay than the SQD >2.5 to 5 cm group (P = 0.041) but not the SQD >5 cm group. Overall, 30-day readmission rates were similar for all groups (P = 0.53). With a median follow-up of 2.8 years, the 1- and 3-year graft survival rates of the entire cohort were 95% and 93%, respectively. There was no difference in patient and graft survival among the three SQD groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Kidney graft survival and (b) patient survival between groups: subcutaneous depth ≤2.5 cm, >2.5 to 5 cm, and >5 cm.

DISCUSSION

It is well established that compared with their nonobese counterparts, obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) and severely obese (BMI >35 kg/m2) KT recipients have higher rates of SSI, but similar graft survival. In a study by Marks et al, 23 morbidly obese KT recipients were compared with 224 nonobese recipients. Three-year graft and patient survival were similar between the groups, although morbidly obese patients had longer hospital stays, higher readmission rates, and a higher SSI rate when compared to nonobese recipients.19 In an analysis using the US Renal Data System, a survival advantage of being transplanted vs remaining on dialysis for obese patients was confirmed; however, the survival benefit was no longer seen in patients with a BMI ≥41 kg/m2.20 As a result of this and similar studies, many transplant centers have instituted maximum BMI limits to evaluate and/or list a candidate.

In the general surgery literature, research has shown that SQD depth is a better predictor of developing SSI than BMI.17,21,22 In these studies, measurements were assessed using indirect methods, i.e., computed tomography. However, imaging all candidates undergoing KT evaluation is not cost-effective and, more importantly, is unnecessary.

In this study, we investigated the results of various SQD ranges using direct intraoperative measurement. Patients across all SQD groups had similar demographic characteristics, and there was no difference in the quality of the donor (i.e., deceased donor, donation after cardiac death donor, and kidney donor profile index). Technical complications such as lymphoceles, fascial dehiscences, renovascular problems, and ureteral problems were not significantly different among the three groups. Surprisingly, implantation time was not statistically longer in the SQD >5 cm group. This may be explained by the fact that, in this program that trains both residents and fellows, more complex cases may have required intervention by the attending surgeon. Although there was no difference in cold ischemia time, the time was demonstrably shorter in the SQD ≤2.5 cm group. Also, while the difference was not statistically significant, there were more living donors and less donation after cardiac death donors (which were all pumped prior to implantation) allocated to the lower SQD group.

As expected, patients with a greater SQD ultimately required wVAC therapy. This modality was successful in achieving complete wound healing in all 28 patients. Reasons for poorer wound healing in recipients with a greater SQD include factors such as a larger incision, greater dead space between the fascia and skin, and potential involvement of skin creases or folds in the incision. Few studies have described the benefit of wVAC therapy in the transplant setting.23–25 A systematic review on the topic identified a total of 22 KT recipients who underwent wVAC therapy with successful outcomes.26 Further studies examining the efficacy and cost of therapy may help to assess whether this modality is beneficial in transplantation.

It may appear we are overly aggressive in placing wVAC devices, but given that our patient population was generally overweight (median BMI 28), early placement allows for better tracking of wounds in the outpatient setting and improved patient satisfaction. Thus, our attentive approach to wounds has paid off. Previously, we trialed placing prophylactic wVACs, incision line wVACs, and percutaneous drains at the time of surgery in our obese patients, but we found this to be cost-ineffective and tedious when dealing with the conundrum of when to best remove drains.

It is difficult to address the SQD value that best correlates with a BMI of 25, 30, and 35 from a single-center, low-power study. Interestingly, our SQD subgroups nearly aligned with the established BMI categories. Patients with an SQD of >5 cm generally had a BMI >35 kg/m2. Patients with an SQD ≤2.5 cm generally had a BMI <25, and those in between generally had a BMI of 30. Thus, BMI and SQD were well correlated. Confirmation of this finding may be verified in subsequent studies using computed tomography SQD measurements in patients with known BMIs.

We recognize the limitations in our study. First, we documented only 3 cases of SSI: in other words, we only had three positive culture results for which antibiotic therapy was instituted. Our practice is not to routinely culture draining wounds unless there is evidence of frank purulent discharge. As a result, we are not able to make a solid comparison against earlier studies looking at SSI in obese patients. Next, we recognize the excessive occurrence of fascial dehiscences (nearly 10%) during the study period. As a result, our fascial closure technique was adjusted, resulting in a much improved dehiscence rate. Third, our study did not address the presence of visceral fat, which also contributes to obesity and body habitus. Finally, the power of our study, particularly in the SQD >5 cm category, may have limited further significant findings.

In summary, SQD is a better surrogate of abdominal obesity yet correlates with BMI such that a higher BMI and deeper SQD are associated with a greater risk of wound complications. While no level of SQD negatively affected patients’ short-term outcomes, an SQD >2.5 cm is an independent risk factor for subsequent wound healing intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank our biostatisticians, Tsung-Wei Ma and Giovanna Saracino, for their invaluable contributions to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Samhan M, Sinan T, Al-Mousawi M.. Vascular complications in renal recipients. Transplant Proc. 1999;31(8):3227–3228. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(99)00703-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassiri A, Simforoosh N, Gholamrezaie HR.. Ureteral complications in 1100 consecutive renal transplants. Transplant Proc. 2000;32(3):578–579. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(00)00897-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fockens MM, Alberts VP, Bemelman FJ, van der Pant KA, Idu MM.. Wound morbidity after kidney transplant. Prog Transpl. 2015;25(1):45–48. doi: 10.7182/pit2015812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Røine E, Bjørk IT, Oyen O.. Targeting risk factors for impaired wound healing and wound complications after kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(7):2542–2546. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.05.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopau K, Syamken K, Rubenwolf P, Riedmiller H, Wanner C.. Impact of mycophenolate mofetil on wound complications and lymphoceles after kidney transplantation. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2010;33(1):52–59. doi: 10.1159/000289573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramos A, Asensio A, Muñez E, et al. Incisional surgical site infection in kidney transplantation. Urology. 2008;72(1):119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Troppmann C, Pierce JL, Gandhi MM, Gallay BJ, McVicar JP, Perez RV.. Higher surgical wound complication rates with sirolimus immunosuppression after kidney transplantation: a matched-pair pilot study. Transplantation. 2003;76(2):426–429. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000072016.13090.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean PG, Lund WJ, Larson TS, et al. Wound-healing complications after kidney transplantation: a prospective, randomized comparison of sirolimus and tacrolimus. Transplantation. 2004;77(10):1555–1561. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000123082.31092.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pourmand GR, Dehghani S, Saraji A, et al. Relationship between post-kidney transplantation antithymocyte globulin therapy and wound healing complications. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2012;3(2):79–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch RJ, Ranney DN, Shijie C, Lee DS, Samala N, Englesbe MJ.. Obesity, surgical site infection, and outcome following renal transplantation. Ann Surg. 2009;250(6):1014–1020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b4ee9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris AD, Fleming B, Bromberg JS, et al. Surgical site infection after renal transplantation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(4):417–423. doi: 10.1017/ice.2014.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humar A, Ramcharan T, Denny R, Gillingham KJ, Payne WD, Matas AJ.. Are wound complications after a kidney transplant more common with modern immunosuppression? Transplantation. 2001;72(12):1920–1923. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200112270-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo JH, Wong MS, Perez RV, Li CS, Lin TC, Troppmann C.. Renal transplant wound complications in the modern era of obesity. J Surg Res. 2012;173(2):216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wszoła M, Kwiatkowski A, Ostaszewska A, et al. Surgical site infections after kidney transplantation—where do we stand now? Transplantation. 2013;95(6):878–882. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318281b953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grosso G, Corona D, Mistretta A, et al. The role of obesity in kidney transplantation outcome. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(7):1864–1868. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, et al. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32(6):959–966. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levi B, Zhang P, Lisiecki J, et al. Use of morphometric assessment of body composition to quantify risk of surgical-site infection in patients undergoing component separation ventral hernia repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(4):559e–566e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JS, Terjimanian MN, Tishberg LM, et al. Surgical site infection and analytic morphometric assessment of body composition in patients undergoing midline laparotomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(2):236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marks WH, Florence LS, Chapman PH, Precht AF, Perkinson DT.. Morbid obesity is not a contraindication to kidney transplantation. Am J Surg. 2004;187(5):635–638. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glanton CW, Kao TC, Cruess D, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC.. Impact of renal transplantation on survival in end-stage renal disease patients with elevated body mass index. Kidney Int. 2003;63(2):647–653. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tongyoo A, Chatthamrak P, Sriussadaporn E, Limpavitayaporn P, Mingmalairak C.. Risk assessment of abdominal wall thickness measured on pre-operative computerized tomography for incisional surgical site infection after abdominal surgery. J Med Assoc Thai. 2015;98(7):677–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujii T, Tsutsumi S, Matsumoto A, et al. Thickness of subcutaneous fat as a strong risk factor for wound infections in elective colorectal surgery: impact of prediction using preoperative CT. Dig Surg. 2010;27(4):331–335. doi: 10.1159/000297521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shrestha BM, Nathan VC, Delbridge MC, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy in the management of wound infection following renal transplantation. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2007;5(1):4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heap S, Mehra S, Tavakoli A, Augustine T, Riad H, Pararajasingam R.. Negative pressure wound therapy used to heal complex urinary fistula wounds following renal transplantation into an ileal conduit. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(10):2370–2373. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Routledge T, Saeb-Parsy K, Murphy F, Ritchie AJ.. The use of vacuum-assisted closure in the treatment of post-transplant wound infections: a case series. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(9):1444 doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.12.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shrestha BM. Systematic review of the negative pressure wound therapy in kidney transplant recipients. World J Transplant. 2016;6(4):767–773. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i4.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]