Abstract

Rhabdomyolysis is a severe form of myopathy and a relatively common condition affecting the pediatric population. Early and aggressive intravenous volume expansion remains the mainstay of rhabdomyolysis treatment in both children and adults to minimize potential serious complications, including heme-induced acute kidney injury and metabolic abnormalities. We describe a 15-year-old boy with a previous hospital admission for rhabdomyolysis who presented with tea-colored urine, muscle cramps, and weakness with significant elevation of creatinine kinase (CK) following a viral illness. Due to minimal response to aggressive intravenous fluid therapy, intravenous methylprednisolone was administered, leading to a dramatic decrease in the CK level and improvement in his clinical symptoms. Genetic analysis revealed a mutation in the BIN1 gene diagnostic of congenital centronuclear myopathy.

Keywords: Centronuclear myopathy, pediatric, rhabdomyolysis, steroid treatment

Rhabdomyolysis is a common cause of hospital admission in the pediatric population. Patients with rhabdomyolysis are treated with volume expansion and close monitoring of electrolytes and renal function. Most patients with rhabdomyolysis respond well to this treatment, but some do not. For this subset of patients, there is no proven second-line therapy for fluid-resistant rhabdomyolysis.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 15-year-old boy presented to the emergency department with a 1-day history of dark urine and diffuse musculoskeletal pain. He completed a 5-day course of oseltamivir for a clinically suspected influenza illness the day prior to presentation. Three years earlier he was diagnosed with rhabdomyolysis from presumed viral myositis, in which his creatinine kinase (CK) level peaked at 582,859 IU/L and he required 8 days of treatment with fluid administration and sodium bicarbonate. There were no reported developmental delays or family history of myopathy.

During the current hospitalization, vital signs were normal for age except for tachycardia. Physical examination was significant for upper- and lower-extremity muscle tenderness without edema. On laboratory evaluation, CK was elevated at 330,000 IU/L (normal range, 0–225). Abnormalities on metabolic panel included an aspartate transaminase of 2762 IU/L (normal range, 10–45), alanine aminotransferase of 450 IU/L (normal range, 0–68), and albumin of 3.3 g/dL (normal range, 3.6–5.1). A chemistry panel showed normal levels of sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, phosphorous, calcium, bilirubin, and gamma-glutamyl transferase. The complete blood count was normal, and the urine drug screen was negative.

His rhabdomyolysis was managed by volume expansion with 40 mEq sodium bicarbonate in 0.45% saline at 500 mL/h. Fluids were titrated to maintain a goal urine output of 250 mL/h and eventually transitioned to 0.9% saline. Creatinine and blood urea nitrogen remained within normal limits. On hospital day 6, his CK level was persistently elevated at 112,000 IU/L. A single dose of 500 mg intravenous methylprednisolone was administered. The following day, his CK decreased to 55,727 IU/L. On day 10, the CK level remained at 17,700 IU/L, and he continued to complain of myalgias; thus, a second dose of 500 mg methylprednisolone was administered. The next day, the CK level decreased to 9524 IU/L and he was able to ambulate without significant pain. With the history of recurrent rhabdomyolysis, an inherited cause was suspected, and genetic evaluation revealed a mutation in the BIN1 gene, a cause of congenital centronuclear myopathy.

DISCUSSION

Rhabdomyolysis can be life threatening due to skeletal muscle breakdown, leading to laboratory abnormalities and kidney injury. When skeletal muscle is broken down, myoglobin is released and can form casts in the kidneys. Intravenous fluids are the predominant treatment to minimize this risk. There are no specific standards regarding the fluid type or rate, though a goal urine output of 200 to 300 mL/h has been recommended.1–3 In addition, the use of sodium bicarbonate remains controversial.1,4 Steroids inhibit vasodilation and the increased vascular permeability that occurs following an insult and decreases leukocyte emigration into inflamed sites.5 Limited data are available regarding the efficacy of steroids in rhabdomyolysis treatment; however, there are case reports documenting the use of steroids in adult patients.6–9

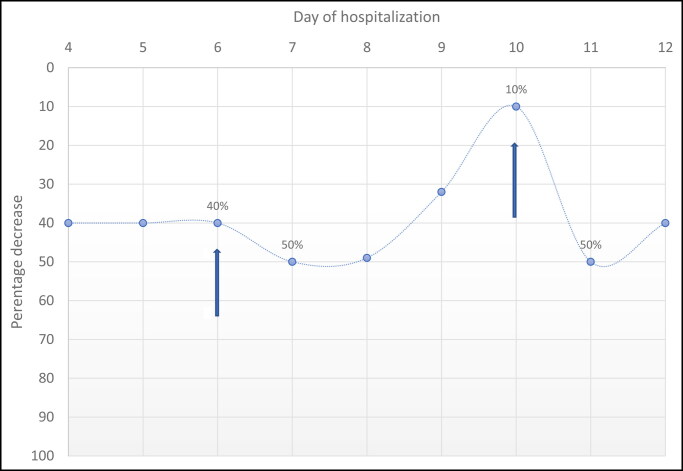

In this case, the patient’s CK level decreased by 40% in the 2 days preceding steroid administration. After corticosteroids, he had significant clinical improvement and a decrease in CK level of 50%. He was continued on aggressive hydration but required frequent treatment to manage pain and hypervolemia. The rate of CK decline slowed; hence, he received a second dose of methylprednisolone with a 50% reduction of CK (Figure 1). The timing of steroid administration with the decrease in CK level and symptom improvement suggests an effect of corticosteroids. This decline is likely due to the anti-inflammatory properties of corticosteroids, limiting ongoing muscle injury caused by a persistent inflammatory state.9

Figure 1.

Decrease in creatinine kinase values over the course of the patient’s hospitalization. The arrows represent the first and second doses of steroids.

The patient was diagnosed with centronuclear myopathy due to a mutation in the BIN1 gene. This gene produces a protein that plays a part in T-tubule development in muscle fiber membranes.10 The disease is usually progressive, and patients can eventually require assistance with ambulation.11 Based on the diagnosis and response to steroids, this patient may benefit from early steroid administration should he present with symptoms of rhabdomyolysis in the future.

In conclusion, corticosteroids may decrease length of hospital stay and benefit patients who have persistently elevated CK levels and continued symptoms despite hydration. Given these findings, further research is necessary to determine optimal dosing, understand risk factors related to steroids in this illness, and identify patients who may benefit from corticosteroid therapy.

References

- 1.Chavez LO, Leon M, Einav S, Varon J.. Beyond muscle destruction: a systematic review of rhabdomyolysis for clinical practice. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1314-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres PA, Helmstetter JA, Kaye AM, Kaye AD.. Rhabdomyolysis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):58–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerman JL, Shen MC.. Rhabdomyolysis. Chest. 2013;144(3):1058–1065. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heard H, Barker J.. Recognizing, diagnosing, and treating rhabdomyolysis. J Am Acad PAs. 2016;29(5):29–32. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000482294.31283.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perretti M, Ahluwalia A.. The microcirculation and inflammation: site of action for glucocorticoids. Microcirculation. 2000;7(3):147–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2000.tb00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirohama D, Shimizu T, Hashimura K, et al. Reversible respiratory failure due to rhabdomyolysis associated with cytomegalovirus infection. Intern Med. 2008;47(19):1743–1746. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yasumoto N, Hara M, Kitamoto Y, Nakayama M, Sato T.. Cytomegalovirus infection associated with acute pancreatitis, rhabdomyolysis and renal failure. Intern Med. 1992;31(3):426–430. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.31.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown J, Mitchell S.. A complicated case of exertional heat stroke in a military setting with persistent elevation of creatine phosphokinase. Mil Med. 1992;157(2):101–103. doi: 10.1093/milmed/157.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antoon JW, Chakraborti C.. Corticosteroids in the treatment of alcohol-induced rhabdomyolysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(10):1005–1007. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Organization for Rare Disorders. Centronuclear myopathy. 2020. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/centronuclear-myopathy/.

- 11.Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center . Centronuclear myopathy. Updated November 1, 2020. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/101/centronuclear-myopathy.