Abstract

Objective:

Efficiently addressing patient priorities and concerns remains a challenge in oncology. Systematic operationalization of patient-centered care (PCC) can support improved assessment and practice of PCC in this unique care setting. This review aimed to synthesize the qualitative empirical literature exploring the National Academy of Medicine (NAM)’s PCC constructs of values, needs, and preferences among patients’ during their cancer treatment experiences.

Methods:

A systematic review of qualitative studies published between 2002 and 2018 addressing adult patient values, needs, and preferences during cancer treatment was conducted. Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and SCOPUS databases were searched on September 10, 2018. Methodological rigor was assessed using a modified version of the Evaluation Tool for Qualitative Studies. Included study findings were analyzed using line-by-line coding; and the emergent themes were compared to the National Academy of Medicine (NAM)’s PCC dimensions.

Results:

Twenty-nine primary studies were included in the synthesis. Descriptive themes for values (autonomy, being involved, family, hope, normality, and sincerity), needs (care coordination, information, privacy, support of physical well-being, emotional support (family/friends, peer, provider), and self-support), and preferences (care coordination, decision-making, information delivery, source of social support, and treatment) were identified. “Cancer care context” emerged as an important domain in which these constructs are operationalized. This thematic framework outlines PCC attributes that oncology care stakeholders can evaluate to improve patient experiences.

Conclusions:

These findings build on previous PCC research and may contribute to the systematic assessment of patient priorities and the improvement of oncology care quality from the patient perspective.

Keywords: cancer, patient-centered care, patient-centered outcomes research, qualitative research, quality of healthcare, systematic review, value-based purchasing

1 |. BACKGROUND

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM), formerly known as the Institute of Medicine, defines care quality as “the degree to which health care services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”1(p4) A long list of “desired health outcomes” has been developed to assess and support improvements in care quality. However, considering who defines outcomes and how stakeholders’ perspectives can affect healthcare quality improvement efforts is critical. The NAM recognizes patient-centered care (PCC) as a critical component of care quality, emphasizing the importance of incorporating patient perspectives in defining quality.2 Several PCC models or frameworks have been developed,2–14 of these, the NAM model is probably the most widely referenced in the literature. The NAM PCC model has six dimensions: (1) respect for patients’ values, preferences, and expressed needs; (2) coordination and integration of care; (3) information, communication, and education; (4) physical comfort; (5) emotional support and alleviation of fear and anxiety; and (6) involvement of family and friends.2 While sub-components of PCC have been identified both broadly2–5,7,9–15 and for oncology,16,17 consistent and comprehensive PCC measurement and practice is still a concern. Improved assessment and implementation of PCC is increasingly important in cancer care due to the growing size and diversity of patient populations, high costs, and the growing number of care models and treatment options.18

Findings from the 2016 Cancer Care Patient Access and Engagement Report suggest that there is a system-level breakdown in addressing patient concerns in the inherently complex oncology setting.19 The report found that high proportions of cancer patients did not receive adequate information regarding: (1) care costs (>50%); (2) the rationale for, benefits, and potential side effects of treatment (approximately 33%); and (3) the availability of clinical trials (87%).19 Further, more than 50% of respondents were not screened for distress,14 as required by the Commission on Cancer and American College of Surgeons.20 Another study among breast cancer patients (n = 395) found high patient-provider discordance regarding what occurred during consultations (eg, whether the patient was comforted), and the importance of certain consultation factors (eg, being told about the potential risks or side effects of additional treatment).21 Despite the discrepancies observed in this study, high patient satisfaction scores were reported (mean = 91/100, range:13–100) using the Patient Services Received Scale and global satisfaction. These findings suggest that data from satisfaction measures can be misleading about the content and quality of patient-provider interactions, especially among seriously ill patients.21 Advances are needed in the way patients’ priorities are assessed and incorporated into cancer care.

To advance PCC in practice, it is important that PCC measures have high content validity that accurately reflect PCC and support its implementation in clinical practice. However, there have been issues in PCC measurement that stem from multiple definitions and models that are often applied partially or inconsistently in measures.5,10,13,14,22,23 Some of the current issues in PCC measurement in oncology include: (1) a lack of standardized PCC measures applicable to a broad range of cancers;24,25 (2) inconsistent assessment across all aspects of care experience (eg, access, advanced care planning, and management of comorbidities); and (3) a lack of readily available data to support timely and effective adjustments to care.7,24,26 Improved PCC operationalization in oncology can address issues with standardization across cancer sites, the cancer care continuum, and among diverse patient groups. Furthermore, standardized assessments of PCC-related information could facilitate more efficient information-sharing leading to more timely and meaningful responses to patient concerns.

1.1 |. Closing the conceptual gaps in PCC in cancer care

Given the existing limitations of PCC measurement and operationalization, a review of the qualitative literature has the potential to refine existing conceptual frameworks. The NAM PCC model provides a well-referenced framework to structure a review and synthesis of the current PCC qualitative literature. The first dimension of the NAM PCC model (respect for patients’ values, preferences, and expressed needs) differs from the other five dimensions because it calls for the consideration of patient-specific attributes, namely values, needs, and preferences. The other five dimensions represent specific ways that providers can respond to previously identified patient values, needs and preferences as recommended by the first dimension. For instance, the second NAM PCC dimension, coordination of care, reflects how providers can address patients’ need for more streamlined or integrated services. The sixth NAM PCC dimension, involvement of family and friends, is indicative of a patient preference or need to include family and friends in healthcare experiences. We anticipated that new or more refined PCC domains relevant to cancer may be identified by exploring themes associated with cancer patient values, needs, and preferences in the literature.

Examining patient values, needs, and preferences may capture other factors important to cancer patients that may not correspond to the other five NAM dimensions, and support more streamlined PCC operationalization and organization of PCC dimensions. To date, no known review of the empirical qualitative literature on PCC-related dimensions for oncology has been conducted. This review aimed to: (1) systematically review and synthesize the qualitative empirical literature exploring expressed needs, values, and preferences among adult patients during their cancer treatment experiences, and (2) identify components of PCC particularly important in oncology to support its systematic evaluation and implementation in practice.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Study design

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRI-SMA statement27 and thematic synthesis methodology outlined by Thomas and Harden was utilized to examine the identified PCC constructs among cancer patients.28 A critical realist approach informed the thematic synthesis that required researchers to acknowledge that patients’ descriptions of their cancer treatment in the primary studies may have been influenced by their beliefs, environment, and experiences.29 The interpretation and reporting of these descriptions may have also been affected by the beliefs, environment, and experiences of the authors of the current and the original studies.29,30

This review was registered with PROSPERO (Registration no. CRD42017074718) and adheres to the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) guidelines.30 It was submitted for ethical review and declared exempt by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

2.2 |. Search strategy

Databases searched included Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and SCOPUS. A health sciences librarian experienced in systematic reviews assisted with the search strategy development, search process, and documentation. The final search strategy included subject headings and keywords that reflected the following topic areas: cancer, PCC (including patient experience, preferences, views, satisfaction, expectations, and needs), and qualitative analysis (see Appendix A). EndNote 831 was used to manage citations.

2.3 |. Eligibility criteria

Primary studies were included if they: (1) conducted original qualitative research; (2) reported descriptions of adult patients’ (≥18 years old) needs, values, or preferences for cancer treatment; and (3) were published in English between 2002 and the search date (September 10, 2018). The 2002 start date was chosen to capture studies published after the 2001 NAM report. Studies were excluded if they: (1) focused solely on the symptom experience or on a single aspect of the treatment experience (eg, treatment-decision-making); (2) integrated findings for a mixed study population (eg, patients and caregivers) so that we were unable to distinguish between the two populations; or (3) involved the evaluation of a pre-existing instrument, measure, or intervention.

2.4 |. Study review and selection

Three research team members (KM, SR, ET) with behavioral science training independently screened the titles and abstracts of 200 randomly selected studies (κ < 0.80) to address any possible inconsistencies that might arise from a single researcher screening all the titles and abstracts. The team used Excel workbooks designed for systematic reviews and were blinded to author and journal names.32 Discrepancies were resolved via discussion and consensus. One reviewer screened the remaining titles and abstracts using the established inclusion criteria, and two reviewers conducted full-text reviews of studies to determine final eligibility.

2.5 |. Data extraction and quality appraisal

Study characteristics (eg, year, design, country, and so on), themes and results sections were extracted from each paper using a coding form (Appendix B). One researcher evaluated the studies for scientific and methodological rigor and quality using a modified form of the Evaluation Tool for Qualitative Studies (ETQS), (Appendix C).33,34 The composite score and the percentage of ETQS criteria were calculated for each study.

2.6 |. Data analysis

The three main constructs of the NAM’s first PCC dimension, values, needs, and preferences, were used as a priori structural codes and guided deductive analysis of the primary studies’ findings.2,28,35 Construct definitions were based on widely accepted definitions (Table 1). Three of the authors analyzed the data from the included studies’ results sections using line-by-line coding.28 Fourteen of the studies’ results sections were independently coded by two researchers to establish a consensus on the emergent themes. After a consensus was reached, one researcher coded the remaining results sections. Only themes that were supported by patient quotations in multiple primary studies were included. The final coding scheme was reviewed by the remaining authors. The identified themes for values, needs, and preferences were compared to each other and the NAM PCC model2 to see if the NAM PCC model could be further refined for operationalization. We outlined how the themes for values, needs, preferences might influence each other in clinical practice and attempted to reconcile their intersections and simplify the PCC conceptual structure.

TABLE 1.

Conceptual definitions for the three core constructs of PCC

| Construct | Definition |

|---|---|

| Patient needs | Conditions considered necessary for human well-being which may be influenced by individual values and perceptions.36 Needs may be categorized as follows: (1) normative need–determined by expert or professional (2) felt need–determined by perception of individual; may be equated to a want (3) expressed need - felt need that is communicated (4) comparative need–obtained by observation or study of individual or group to determine gaps in the provision of a service or between current and desired states.36,37 |

| Patient values | Beliefs that represent an individual’s interests (individualistic, collectivist, or both) and are motivated by human needs (eg, enjoyment, security, self-direction, and so on) this may be evaluated on a scale of importance (eg, from very important to unimportant) as a guiding principle in someone’s life.38 |

| Patient preferences | Assessments that reflect the relative importance of dimensions of health care (eg, treatment options, clinical behavior of providers, and care outcomes) and are determined by cognitive processes, values, experiences, and reflection; they may be expressed as actions or statements.39 |

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Study selection, characteristics and quality assessment

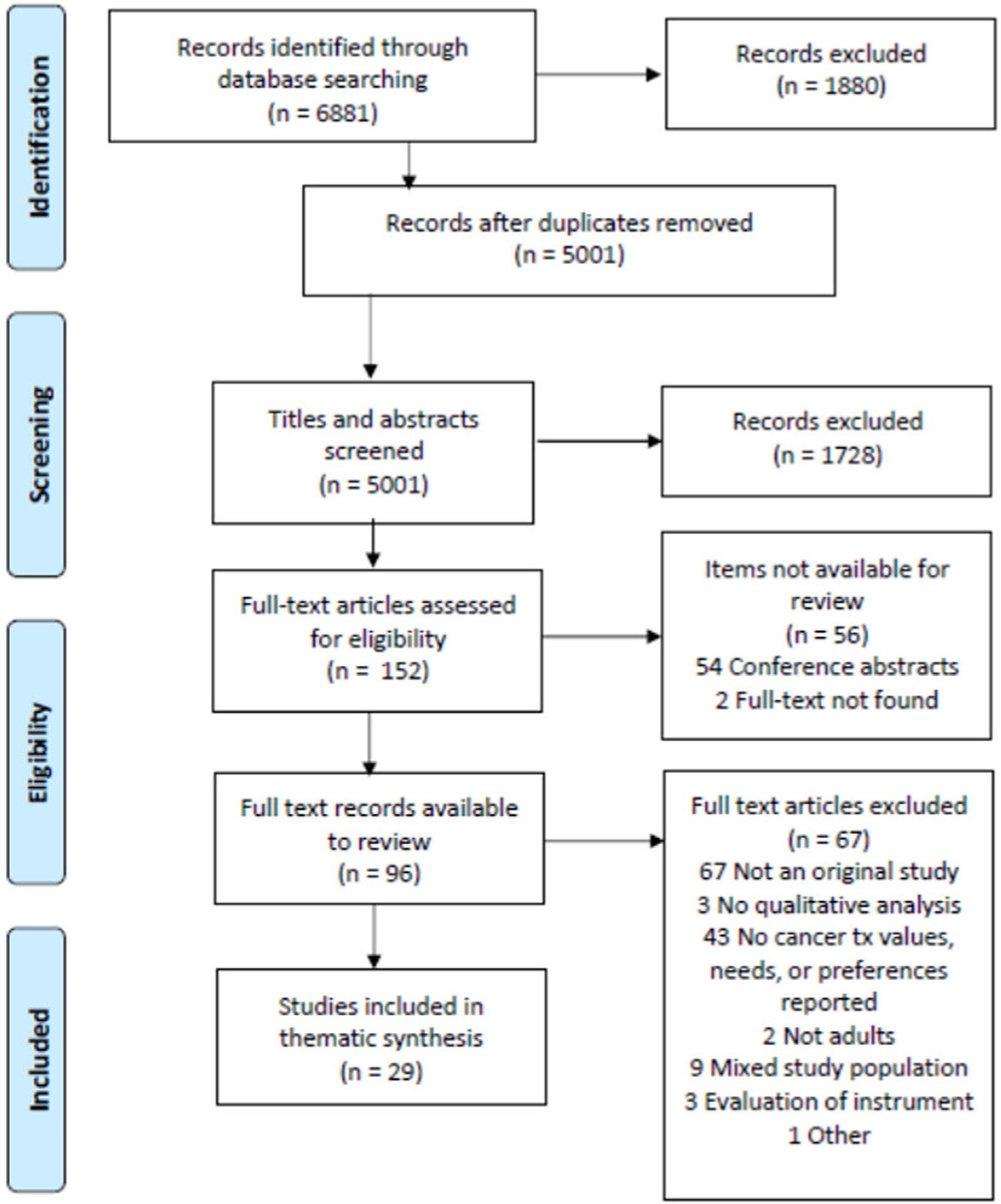

A total of 6881 unique records were identified. Twenty-nine met inclusion criteria after screening and full-text review (Figure 1). Principal reasons for exclusion were not describing patient perspectives of the cancer treatment experience and not being a qualitative study. Descriptive statistics for primary study characteristics are provided in Table 2. A full summary of the primary studies’ characteristics and their ETQS scores may be found in Appendix D. The quality assessment indicated that most studies were conducted with adequate scientific rigor for qualitative analysis (mean = 31.8 (83.7%), range: 23 (61%)–38 (100%). Of the 29 studies, 22 scored 30 or more points on the modified ETQS scale. Studies with lower scores tended not to report potential researcher biases or how they were addressed.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of study inclusion and exclusion for thematic synthesis of cancer PCC literature, 2002–2018

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics of the cancer sites of participants and geographic location and time period of the primary studies (n = 29), cancer PCC thematic synthesis, 2002–2018

| Study characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Cancer site | |

| Brain | 1 (3.4) |

| Breast | 7 (24.1) |

| Genitourinary | 6 (20.7) |

| Gastrointestinal | 3 (10.3) |

| Head and neck | 2 (6.9) |

| Skin | 1 (3.4) |

| Multiple cancer sites | 9 (31.0) |

| Study location | |

| Africa | 1 (3.4) |

| Nigeria | 1 (3.4) |

| Asia | 2 (6.9) |

| India | 1 (3.4) |

| China | 1 (3.4) |

| Australia | 1 (3.4) |

| Europe | 16 (55.2) |

| Belgium | 1 (3.4) |

| France | 1 (3.4) |

| Ireland | 1 (3.4) |

| Italy | 1 (3.4) |

| Netherlands | 4 (13.8) |

| Sweden | 1 (3.4) |

| United Kingdom | 7 (24.1) |

| North America | 9 (31.0) |

| Canada | 4 (13.8) |

| USA | 5 (17.2) |

| Time period | |

| 2002–2005 | 3 (10.3) |

| 2006–2009 | 5 (17.2) |

| 2010–2013 | 7 (24.1) |

| 2014–2018 | 14 (48.3) |

3.2 |. Synthesis of results

In this thematic synthesis, the structural code, cancer care context, emerged in addition to the a priori structural codes: values, needs, and preferences. Table 3 depicts a high-level overview of all the structural codes, themes, and sub-themes identified in the synthesis. Selected quotations are included in the narrative below to illustrate selected subthemes, and a full listing of example quotations for all themes and subthemes are provided in Appendix E.

TABLE 3.

Descriptive themes and sub-themes for patient values, needs, preferences, and cancer care context, cancer PCC thematic synthesis, 2002–2018

| Structural code | Theme | Subtheme(s) |

|---|---|---|

| General values | Autonomy40–42 | |

| Hope42,43 | ||

| Being involved40,44–47 | Being listened to45,47 | |

| Being involved in decision-making40,44,46 | ||

| Taking action42,43 | ||

| Family40,42,43 | ||

| Normality42,48–51 | ||

| Sincerity41,47 | ||

| Needs | Care coordination40,42,43,45,49,52–57 | Timely care access and scheduling44,49,54,55,58 |

| Advising/Answering patient questions43,45,52,55,57 | ||

| Advocacy45,55 | ||

| Follow-up after treatment53,57 | ||

| Holistic care45,56 | ||

| Information40,42,44,45,47,49–52,54–56,59–64 | Available resources and support45,51,52,62 | |

| Care stages and processes40,42 | ||

| Individual and diagnosis-specific40,42,47,56,59,64 | ||

| Knowledge of what to expect42,47,61,62,64 | ||

| Minimizing costs40,52,62 | ||

| Nutrition45,52 | ||

| Prognosis47,55 | ||

| Side effects/symptoms (physical and psychological)45,51,52,61,62 | ||

| Treatment options and rationale42,47,59,60,63,64 | ||

| Updates on condition and treatment40,56 | ||

| Privacy47,60 | ||

| Support of physical well-being43,51,65 | ||

| Social support (family/friends)40,49,59,61 | ||

| Social support (peer)45,51,55,56,59 | ||

| Social support (provider)40,41,44,45,47,49–53,55–57,59–61,63 | Checking on patient50,57,63 | |

| Friendliness40,53,60 | ||

| Relationship/repeated interactions53,55 | ||

| Respect and understanding40,44,45,51,55,63 | ||

| Talking with the patient41,51,53 | ||

| Spending time with the patient47,53,55 | ||

| Timely communication49,53,61 | ||

| Self-support41–43,47,50,51,54,55,59 | Being positive41,43,50,54,61 | |

| Being strong43,54,59 | ||

| Faith/spirituality41,54 | ||

| Ability to trust provider41,47,52,57,59 | ||

| Talking about cancer experience41,51 | ||

| Preferences | Care coordination43,44,51,53,55,59,60 | Consultation location55,59 |

| Provider51,53 | ||

| Family involvement43,60 | ||

| Decision-making40,44,46,52,59 | Involvement40,44,46 | |

| Timing52,59 | ||

| Information delivery45,51,54,59,60,62 | Sources of information54,60 | |

| Amount of information54,59,62 | ||

| Disclosure to others45,51 | ||

| Source of social support40,45,49,51,55,56,59,61 | Peer45,51,56,59 | |

| Provider40,51 | ||

| Family and friends49,55,59,61 | ||

| Treatment42,45,51,54,55,59 | Amount of treatment42,45,51 | |

| Break from or stopping treatment54,55,59 | ||

| Cancer Care Context | Psychological responses41–43,47–51,53–57,59,62,66 | Being overwhelmed41,55 |

| Fear41–43,48–50,59 | ||

| Feeling lost43,55 | ||

| Feeling isolated50,53,59 | ||

| Reflection41,47,49 | ||

| Sadness/depression51,54,57 | ||

| Shock/surprise41,43,48,50,51,55,59 | ||

| Uncertainty47,48,54,56,62,66 | ||

| Worry41,51,57,59,66 | ||

| Treatment planning and selection46,50,57,59,65 | Acknowledging and accepting the need for treatment46,50,59 | |

| “Transition from well to ill”41,42,46–51,55–57,59 | Adjusting to illness, treatment, and reduced qol41,46–51,57,59 | |

| Acknowledging and accepting the reality of morbidity/mortality41,42,46,48,49,51,54,59 | ||

| Difficulty discerning normal from abnormal56,59 | ||

| Managing multiple burdens41,50,55 | ||

| Maintaining normality42,48,51,59 | ||

| Waiting40,44,50,54,67 |

3.2.1 |. Values

Themes related to patient values included the following: (1) autonomy, (2) being involved, (3) family, (4) hope, (5) normality, and (6) sincerity. Autonomy encompassed the patients’ abilities to engage in their treatments on their terms and to participate in care discussions and support or approve care decisions. Being involved reflected patients’ appreciation for participation and inclusion in their care. There were three sub-themes for this theme: (1) being listened to, (2) being involved in decision-making, and (3) taking action. Family encompassed the patient’s concern for family members’ welfare and well-being. Hope involved supportive words and actions that demonstrated a positive outlook on a patient’s circumstances that served as motivation for some patients to continue treatments and overcome cancer. Multiple studies noted patients’ desires for normality as a key aspect of coping with their condition. For some, it was a central goal and they made efforts to maintain and protect normality for themselves and their loved ones. Finally, sincerity emerged as an important factor for patients because it helped them to confirm the trustworthiness of their providers, another critical factor in their care experience. One patient from a study conducted among hospitalized cancer patients in Italy describes this in further detail:

Sincerity is something one realizes subsequently; for, during the moment when it is verified that the things the doctor said really are what he said they would be, one understands a posteriori the sincerity of the doctor. A priori, a stronger act of trust is needed; for this it is important to have an empathetic rapport with patients.42(p8)

3.2.2 |. Needs

Themes that emerged related to needs included: (1) care coordination, (2) information, (3) privacy, (4) support of physical well-being, (5) emotional support (family/friends), (6) emotional support (peer), (7) emotional support (provider), and (8) self-support. Care coordination needs included gaining access to care, navigating the healthcare system, their treatment, and communicating with those involved with their care. There were five sub-themes for care coordination, and they involved timely care access and scheduling, providing holistic care, and advising and answering patient questions. Some of the factors that impeded their access to care were costs, care location, and the availability of medications and providers.50,53 Information was repeatedly mentioned by patients across the studies as being a very important aspect of their care. There were 10 information needs subthemes. The types of information that were identified as being pertinent included details about their specific diagnosis, prognosis, what to expect before, during, and after treatment, answers to questions, and information about supportive services and resources. One patient described some of the challenges experienced trying to obtain prognosis information:

I want to ask, like, do I need to get my affairs in order. Am I going to die? You want the doc to bring it up almost so you don’t have to. But when he don’t, then, it’s on us to ask and I don’t know how to bring it up.50(pe293)

In addition to the well-expressed needs for information, the need for privacy emerged as a theme and was characterized by a desire to be free from unauthorized or unwelcomed sharing of personal space or information to achieve wellbeing.

There was one theme related to physical wellness, support of physical well-being, and four themes related to emotional support: (a) emotional support (family/friends), (b) emotional support (peer), (c) emotional support (provider), and (d) self-support. Support of physical well-being represented the need for assistance in protecting and maintaining the health and function of the patient’s body during treatment. The importance of care and assistance from family and friends emerged as a theme called emotional support (family/friends). Emotional support (peer) was also a theme as some patients emphasized the unique ability of other cancer patients to empathize with their condition and provide useful advice. Emotional support (provider) referred to supportive actions that assisted patients in coping with their cancer and treatments and promoted healing. There were seven sub-themes for emotional support (provider) that included but were not limited to: (1) checking on patient, (2) friendliness, and (3) relationship/repeated interactions. Finally, some patients discussed the need for self-support or the ability to self-assess and adjust to their condition and the situations they encountered as a cancer patient. Self-support had five subthemes that included but were not limited to: (a) being strong, (b) faith/spirituality, and (c) ability to trust provider. Trust emerged as a theme in several studies but in the following quotation, a breast cancer patient from a study conducted in India describes how she believes that a lack of trust and specifically, faith in providers can exacerbate suffering among some patients:

Today most of the rural based patients tend to have immense faith in the doctors… faith is beyond belief… faith is the ultimate. They say, ‘If the doctor says, I have to do this, I have to do this’…they don’t even question…He’s God…that faith cures people more than other stuff but yet if you see among the general populace especially the urban, without counseling, they’re suffering a huge lot.68(p395)

3.2.3 |. Preferences

Five themes related to patient preferences included: (1) care coordination, (2) decision-making, (3) information delivery, (4) source of social support, and (5) treatment. Care coordination centered on preferences related to the planning and organization of their care. Home visits and telephone and email communication or consultations were appreciated because they saved time and helped minimize the stress, inconvenience, and dangers of traveling while ill. Alternatively, others welcomed the opportunity to interact with others during clinic visits. Decision-making preferences varied among patients, with some viewing involvement in treatment decision-making as non-negotiable and others not wanting to participate at all. There were those who trusted the clinical judgment of their providers to make the best care decisions. Information delivery focused on preferences for how information was communicated. Many patients wanted information from their providers; however, there were variations in preferences for the quantity, timing, and source of information. Source of social support referred to preferences surrounding receiving comfort, assistance, and advocacy from a specific person, place, or thing. Some patients felt that their best source of support was other cancer patients, particularly those who shared similar characteristics whether it be diagnosis, age, or family structure. For example:

Only patients with similar experience can understand me. I have encountered difficulties… I really want to know how others deal with the difficulties.63(p129)

Patients had differing preferences regarding their cancer treatment. For example, some preferred surgery over chemotherapy, and in the case of breast cancer, some wanted a double mastectomy vs a mastectomy. Some patients wanted to try everything to fight their cancer while others preferred for as little treatment as possible, even when it came to their side-effects. Finally, some wanted breaks their treatment regimen or to cease treatment altogether, as one patient with brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer shared during an interview study:

If I thought I had to go through that pain again no I wouldn’t wish to carry on I’d wish to call it a day. It sounds silly but I’d say that’s not, that’s not human, I think that’s undignified way of suffering in pain. You know er….Na I would refuse treatment”69(p597)

3.2.4 |. Cancer care context

The cancer care context domain themes reflected different transitions or characteristics of the cancer experience that patients must traverse. They included processes that most patients experience, some patients managed these processes better than others. The cancer care context had five themes: (1) psychological response to diagnosis, (2) treatment planning and selection, (3) “transition from well to ill,” and (4) waiting. Psychological response to diagnosis captured the different mental and emotional experiences patients had during their cancer care. This theme had nine sub-themes including but not limited to: (a) being overwhelmed, (b) feeling isolated, and (c) reflection. Treatment planning and selection captured the process of determining what, if any, treatment to receive; it had one subtheme, acknowledging and accepting the need for treatment. This sub-theme described the process of accepting a cancer diagnosis and deciding whether to agree to begin a therapeutic regimen to treat cancer. “Transition from well to ill”54 encompasses the period of adapting to having cancer and receiving treatment when the symptoms of their illness or side-effects of their treatment may become more noticeable. This theme had five sub-themes including but not limited to: (a) adjusting to illness, treatment, and reduced quality of life (QOL), (b) difficulty discerning normal from abnormal, and (c) managing multiple burdens. The last theme for the cancer care context, waiting, referred to time patients spent anticipating an information, an appointment, or a procedure, which often caused distress. A prostate cancer patient describes his experience waiting:

…[a]nd ahead of the tests, I can tell you that they…[t] hey do affect me. It feels like there’s some kind of…[t] here’s a wall you have to get past, and it’s been like that all the way from the very beginning … It grows and gets higher and higher, …the closer I get to the test, the heavier it feels and…[t]here’s a certain concern or something, but at the same time you want to get it over with and get the results.62(p4)

3.2.5 |. Relationships between identified themes for values, needs, and preferences, and current NAM PCC model

We decided to use needs as a comparator to evaluate the relationships between the themes for values, needs, and preferences. Needs had more themes and sub-themes than the other structural codes and could be used to define the use of values and preferences in practice. Needs are conditions that can be met in the clinical context and are considered critical to patients’ well-being and an individual’s values influence what conditions (needs) are most important. Thus, understanding a patient’s values can help providers better understand and address their needs with the needs being the major focus. Patient preferences reflect patients’ perceived importance of variations in care intended to promote well-being but are not critical to well-being. Therefore, respecting a patient preference such as getting care at a specific location can partially contribute to addressing a patient need such as improved care access. By focusing on the themes for needs in our comparison of the synthesis findings and the NAM model we were able to operationalize five distinct PCC dimensions (1) coordinating and integrating care, (2) communication, (3) providing emotional support, (4) respecting the patient as a person, and (5) promoting physical health/well-being that corresponded to the needs themes from the synthesis and are very similar to the NAM PCC model with a few key differences. Please see Appendix F for operational definitions, specific actions that address patient needs, and potential measurement questions for each updated PCC dimension.

4 |. DISCUSSION

We conducted a systematic review and thematic synthesis of the qualitative PCC literature and identified a set of predominant themes for values, needs, and preferences that paralleled the NAM’s PCC model among a broad range of cancer diagnoses and care settings. The similarity between our findings and the NAM PCC model suggest that there may not be significant differences in PCC dimensions across disease sites, however, there may be important differences at the sub-dimension level to consider. The emergent thematic domain, cancer care context, highlighted unique aspects of the cancer care experience that may influence the relative importance of some PCC dimensions. An updated PCC model for oncology with operational definitions and corresponding actions was generated by concentrating on the identified patient needs that emerged from the synthesis. Focusing on needs and emphasizing the importance of categorizing and addressing sub-dimensional factors may help to simplify the organization of PCC models and their diverse components to support the delivery of more comprehensive and effectual PCC. Establishing a set of common patient needs and proposing that the assessment of values and preferences be used to help meet patient needs in a manner that is appreciated at the individual level may help address persistent issues in PCC measurement and evaluation.

4.1 |. Relevance to existing measures of PCC

Current PCC measures often reflect the symptom experience and related impacts on QOL. There is strong evidence that supports the importance of evaluating and addressing the symptom experience in promoting cancer patient survival.70 PCC is conceptually distinct from these aspects of the care experience and may have unique effects on care outcomes. However, evidence of PCC’s association with such outcomes is lacking due to the challenges of measuring these more subjective aspects of care. Patient experience surveys such as the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) capture many of the themes that were identified in this synthesis.71 However, some aspects of cancer care treatment experience that were identified as being important to patients in the present study are not assessed by the CAHPS Cancer Care Survey.71

The CAHPS surveys are currently used by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to evaluate care. They are well-positioned to evaluate and promote PCC in practice as healthcare payment shifts from fee-for-service to value-based models. Making small changes to existing measures such as the CAHPS has the potential to address existing gaps in PCC measurement. One simple approach to assess each of the PCC dimensions is to ask if all the patient’s needs for each PCC dimension were met. For example, the assessment of promoting physical well-being could be enhanced by an item inquiring about providers’ discussion of any physical well-being issues and whether all their support needs were met in this area. Similar questions could be asked for communication, coordinating and integrating care, and providing emotional support. With regards to specific PCC dimensions, survey items that assess whether cancer care team members respected patients’ personal values and preferences could be added to evaluate respecting the patient as a person. Assessing whether patient values and preferences were incorporated into care could be used to determine whether the PCC dimension, coordinating and integrating care was implemented in a manner that would be appreciated at the individual level. Existing items could be modified to determine if all cancer care team members including providers and office staff were helpful, courteous, and respectful to patients to evaluate providing emotional support. Oftentimes patient experience surveys such as the CAHPS approximate whether patients’ values, needs, and preferences have been accounted for in clinical practice. In some cases, these factors may not be captured, leaving gaps that may be filled by systematically using the needs, values, and preferences concepts.

5 |. CONCLUSION

This study presents a detailed summary of cancer patients’ values, needs, and preferences that helps to further operationalize PCC in the oncology setting. Several of the NAM’s PCC dimensions were extended by the themes and sub-themes from the thematic synthesis to support further refinement of existing PCC measures, specifically in oncology. The themes from this synthesis could be periodically assessed to examine whether cancer patients’ needs (care coordination, information, privacy, support of physical well-being, emotional support—family/friends, emotional support—peer, emotional support—provider, and self-support) are being met, and whether their preferences (care coordination, decision-making, information delivery, source of social support, and treatment), and values (autonomy, being involved, family, hope, normality, and sincerity) are being considered during their care.

Future research should examine the conceptual structures of existing PCC measures in cancer care and compare them to the findings of qualitative research describing important aspects of patients’ treatment experiences to address the identified gaps in PCC measurement and implementation. Furthermore, future studies of PCC in cancer should situate the PCC concepts that are being evaluated by these measures within an existing outcome model such as the Economic, Clinical, and Humanistic (ECHO) model,72 to help clarify relationships between related PCC concepts and other cancer care outcomes.

5.1 |. Study limitations

This study may have omitted some important aspects of PCC in cancer because it was a secondary analysis of published qualitative research and we were not able to analyze the data with the same level of nuances as a primary analysis. However, the use of broad concepts such as values, needs, and preferences, does allow for the investigation and inclusion of a broad range of factors that may contribute to PCC among diverse patient populations. The robustness and transferability of the present findings may be affected by the primary studies’ use of different qualitative methodologies conducted in diverse settings. However, this diversity provided a wide range of patient views reflecting multiple countries, cancer diagnoses and treatments, ages, genders, religious beliefs, ethnicities, occupations, and educational levels, and may have contributed to our study having richer findings and greater generalizability.

5.2 |. Clinical implications

The National Quality Forum asserts that quality measures should not only have strong psychometric properties but generate important and actionable data.73 The identified patient needs often reflected gaps in system-level processes that when left unaddressed could diminish patient experiences. Values and preferences reflected possible variations in care that were more meaningful to patients and if identified and considered, could enhance their experiences. For example, values and preferences for sources of social support can be elicited during clinical encounters by providers using communication tools to inform them of how to individually address needs for emotional support (via periodic intake assessments or electronic health records). Utilizing the definitions of value, need, and preference may serve to streamline PCC assessment, and direct how collected data should be used to modify care. These findings can also advance cancer quality at the national level by informing the refinement of existing measures. Such measures could be included in the quality measures used in value-based payment models such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Patient Centered Oncology Payment Model to support advances in cancer care quality.74

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded in part by the NCI T32 Postdoctoral Training Program Grants No. 2T32CA093423 and T32CA190194. The authors wish to acknowledge Laura Russell from the Department of Scientific Publications at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for her editorial assistance and Helena Vonville for her early assistance and guidance in conducting a systematic review.

Funding information

National Cancer Institute, Grant/Award Numbers: 2T32CA093423, R25CA57712, T32CA190194

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Most data are available in article supplementary material. Any other data of interest are available upon request.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerteis M Picker/Commonwealth Program for Patient-Centered Care. Through the patient’s Eyes: Understanding and Promoting Patient-Centered Care. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centeredness: a conceptual framework and review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1087–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jayadevappa R, Chhatre S. Patient centered care - a conceptual model and review of the state of the art. Open Health Serv Pol. 2011; 4:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rathert C, Williams ES, McCaughey D, Ishqaidef G. Patient perceptions of patient-centred care: empirical test of a theoretical model. Health Expect. 2015;18(2):199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Quality Forum. Priority Setting for Healthcare Performance Measurement: Addressing Performance Measure Gaps in Person-Centered Care and Outcomes. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69 (1):4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammed K, Nolan MB, Rajjo T, et al. Creating a patient-centered health care delivery system: a systematic review of health care quality from the patient perspective. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(1): 12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Constand MK, MacDermid JC, Dal Bello-Haas V, Law M. Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kvale K, Bondevik M. What is important for patient centred care? A qualitative study about the perceptions of patients with cancer. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(4):582–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan S, Yoder LH. A concept analysis of patient-centered care. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(1):6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lusk JM, Fater K. A concept analysis of patient-centered care. Nurs Forum. 2013;48(2):89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sidani S, Fox M. Patient-centered care: clarification of its specific elements to facilitate interprofessional care. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(2): 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zill JM, Scholl I, Harter M, Dirmaier J. Which dimensions of patient-centeredness matter? - Results of a web-based expert Delphi survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0141978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouwens M, Hermens R, Hulscher M, et al. Development of indicators for patient-centred cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(1): 121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uphoff EP, Wennekes L, Punt CJ, et al. Development of generic quality indicators for patient-centered cancer care by using a RAND modified Delphi method. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(1):29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Society of Clinical Oncology. The state of cancer care in america, 2016: a report by the american society of clinical oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(4):339–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CancerCare. CancerCare Patient Access & Engagement Report. New York, NY: CancerCare; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buxton D, Lazenby M, Daugherty A, et al. Distress screening for oncology patients: practical steps for developing and implementing a comprehensive distress screening program. Oncol Issues. 2014;29: 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown RF, Hill C, Burant CJ, Siminoff LA. Satisfaction of early breast cancer patients with discussions during initial oncology consultations with a medical oncologist. Psychooncology. 2009;18(1):42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobbs JL. A dimensional analysis of patient-centered care. Nurs Res. 2009;58(1):52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013; 70(4):351–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzelepis F, Rose SK, Sanson-Fisher RW, Clinton-McHarg T, Carey ML, Paul CL. Are we missing the Institute of Medicine’s mark? A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures assessing quality of patient-centred cancer care. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(41): 1–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zucca A, Sanson-Fisher R, Waller A, Carey M. Patient-centred care: making cancer treatment centres accountable. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(7):1989–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRI-SMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339(7716):332–336. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8 (1):45–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorski PS. What is critical realism? And why should you care?. Con-temp Sociol 2013;42(5):658–670. 10.1177/0094306113499533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Endnote X7 [Computer Program]. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate Analytics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.VonVille HM. Excel Workbooks for Systematic Reviews. Houston, TX: University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health; 2015; http://libguides.sph.uth.tmc.edu/excel_SR_workbook [Google Scholar]

- 33.Long AF, Godfrey M, Randall T, Brettle A, Grant MJ. HCPRDU evaluation tool for qualitative studies. 2009; http://www.fhsc.salford.ac.uk/hcprdu/qualitative.htm.

- 34.Long AF, Godfrey M. An evaluation tool to assess the quality of qualitative research studies. Int J Soc Res Method. 2004;7(2):181–196. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E. Themes and Codes. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradshaw JR. The taxonomy of social need In: Cookson R, Sainsbury R, Glendinning C, eds. Jonathan Bradshaw on Social Policy: Selected Writings 1972–2011. York, UK: York Publishing Services Ltd; 2013:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Brien M The conceptualization and measurement of need: a key to guiding policy and practice in children’s services. Child Fam Soc Work. 2010;15(4):432–440. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armstrong MJ, Mullins CD. Value assessment at the point of care: incorporating patient values throughout care delivery and a draft taxonomy of patient values. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;20(2):292–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petersen GS, Knudsen JL, Vinter MM. Cancer patients’ preferences of care within hospitals: a systematic literature review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(5):384–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akinsuli O Nigerian cancer survivors’ perceptions of care received from health care professionals. Diss Abstr Int. 2017;77:12-B(E):i–115. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barrett GM. A qualitative descriptive study of the needs of older adults recently diagnosed with cancer. Diss Abstr Int. 2017;77:10-B (E):i–97. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dorman S, Hayes J, Pease N. What do patients with brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer want from their treatment? Palliat Med. 2009;23(7):594–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sterckx W, Coolbrandt A, Clement P, et al. Living with a high-grade glioma: a qualitative study of patients’ experiences and care needs. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(4):383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Kok M, Scholte RW, Sixma HJ, et al. The patient’s perspective of the quality of breast cancer care. The development of an instrument to measure quality of care through focus groups and concept mapping with breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(8):1257–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dowling JE. Patient care: a case study of young working women with breast cancer. Diss Abstr Int. 2010;71(3-B):1604. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Owens J, Kelsey S, White A. How was it for you? Men, prostate cancer and radiotherapy. J Radiother Pract. 2003;3(4):167–174. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamburini M, Gangeri L, Brunelli C, et al. Cancer patients’ needs during hospitalisation: a quantitative and qualitative study. BMC Cancer. 2003;3:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carduff E, Kendall M, Murray SA. Living and dying with metastatic bowel cancer: serial in-depth interviews with patients. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(1):e12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fitch MI, Miller D, Sharir S, McAndrew A. Radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: a qualitative study of patient experiences and implications for practice. CONJ. 2010;20(4):177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McIlfatrick S, Sullivan K, McKenna H, Parahoo K. Patients’ experiences of having chemotherapy in a day hospital setting. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59(3):264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walsh E, Hegarty J. Men’s experiences of radical prostatectomy as treatment for prostate cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(2):125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barthakur MS, Sharma MP, Chaturvedi SK, Manjunath SK. Experiences of breast cancer survivors with oncology settings in urban India: qualitative findings. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2016;7(4):392–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hendry JA. A qualitative focus group study to explore the information, support and communication needs of women receiving adjuvant radiotherapy for primary breast cancer. J Radiother Pract. 2011;10(2): 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCahill LE, Hamel-Bissell BP. The patient lived experience for surgical treatment of colorectal liver metastases: a phenomenological study. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(1):65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patel MI, Periyakoil VS, Blayney DW, et al. Redesigning cancer care delivery: views from patients and caregivers. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13 (4):e291–e302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei C, Nengliang Y, Yan W, Qiong F, Yuan C. The patient-provider discordance in patients’ needs assessment: a qualitative study in breast cancer patients receiving oral chemotherapy. J Clin Nurs. 2017; 26(1–2):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wright FC, Crooks D, Fitch M, et al. Qualitative assessment of patient experiences related to extended pelvic resection for rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93(2):92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garg T, Connors JN, Ladd IG, Bogaczyk TL, Larson SL. Defining priorities to improve patient experience in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Bladder Cancer. 2018;4(1):121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beaver K, Williamson S, Briggs J. Exploring patient experiences of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bisschop JA, Kloosterman FR, van Leijen-Zeelenberg JE, Huismans GW, Kremer B, Kross KW. Experiences and preferences of patients visiting a head and neck oncology outpatient clinic: a qualitative study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(5):2245–2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenslade MV, Elliott B, Mandville-Anstey SA. Same-day breast cancer surgery: a qualitative study of women’s lived experiences. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(2):E92–E97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Llewellyn CD, McGurk M, Weinman J. Striking the right balance: a qualitative pilot study examining the role of information on the development of expectations in patients treated for head and neck cancer. Psychol Health Med. 2005;10(2):180–193. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nijman JL, Sixma H, van Triest B, Keus RB, Hendriks M. The quality of radiation care: the results of focus group interviews and concept mapping to explore the patient’s perspective. Radiother Oncol. 2012; 102(1):154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Egmond S, Wakkee M, Droger M, et al. Needs and preferences of patients regarding basal cell carcinoma and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma care: a qualitative focus group study. Br J Dermatol. 2018; 21:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reynolds BR, Bulsara C, Zeps N, et al. Exploring pathways towards improving patient experience of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP): assessing patient satisfaction and attitudes. BJU Int. 2018; 121(Suppl 3):33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feinberg Y, Law C, Singh S, Wright FC. Patient experiences of having a neuroendocrine tumour: a qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013; 17(5):541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schildmeijer K, Frykholm O, Kneck A, Ekstedt M. Not a straight line-patient’s experiences of prostate cancer and their journey through the healthcare system. Cancer Nurs. 2018;12:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Orri M, Sibeoni J, Bousquet G, et al. Crossing the perspectives of patients, families, and physicians on cancer treatment: a qualitative study. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):22113–22122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwartz SH, Bilsky W. Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;50(3):550–562. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Evensen CT, Yost KJ, Keller S, et al. Development and testing of the CAHPS cancer care survey. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(11):e969–e978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kozma CM, Reeder CE, Schulz RM. Economic, clinical, and humanistic outcomes: a planning model for pharmacoeconomic research. Clin Ther. 1993;15(6):1121–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Landrum MB, Nguyen C, O’Rourke E, Jung M, Amin T, Chernew M. Measurement Systems: a Framework for Next Generation Measurement of Quality in Healthcare. Washington, D.C.: National Quality Forum; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 74.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Patient-Centered Oncology Payment: A Community-Based Oncology Medical Home Model. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2019; https://practice.asco.org/sites/default/files/drupalfiles/content-files/billing-coding-reporting/documents/2019%20PCOP%20-%20FINAL_WEB_LOCKED.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.