Abstract

Aim

This study aims to conduct a review of the existing literature about incubation period for COVID-19, which can provide insights to the transmission dynamics of the disease.

Methods

A systematic review followed by meta-analysis was performed for the studies providing estimates for the incubation period of COVID-19. The heterogeneity and bias in the included studies were tested by various statistical measures, including I2 statistic, Cochran’s Q test, Begg’s test and Egger’s test.

Results

Fifteen studies with 16 estimates of the incubation period were selected after implementing the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The pooled estimate of the incubation period is 5.74 (5.18, 6.30) from the random effects model. The heterogeneity in the selected studies was found to be 95.2% from the I2 statistic. There is no potential bias in the included studies for meta-analysis.

Conclusion

This review provides sufficient evidence for the incubation period of COVID-19 through various studies, which can be helpful in planning preventive and control measures for the disease. The pooled estimate from the meta-analysis is a valid and reliable estimate of the incubation period for COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Incubation period, Systematic review, Meta-analysis, Infectious disease, Epidemiology

Introduction

At the end of the year 2019, the first case of COVID 19 was detected in the Wuhan City of China (WHO 2020b). The spread of the virus has been so rapid that despite many control measures, it has affected many nations worldwide. The world is facing an unprecedented threat from COVID-19 and is fighting hard to reduce the loss due to it. The WHO declared it a public health emergency of international concern and later a pandemic on 11 March 2020 (WHO 2020c, 2020d). It has shaken the spirits of even developed nations that are still facing massive trouble in curbing the spread of the disease. As of December 20 2020, globally, there were more than 75 million cases and 1.6 million deaths in 222 countries due to COVID-19, with most of the countries in the transmission stage suggesting a larger outbreak (WHO 2020a).

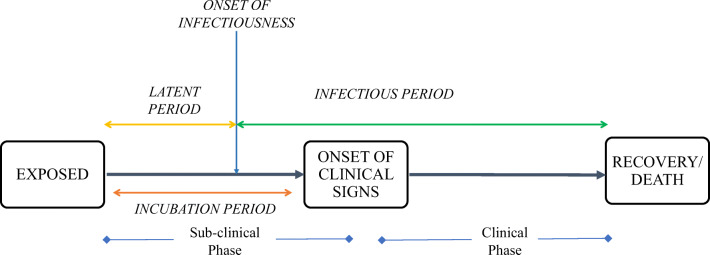

The incubation period is a critical epidemiological measure to curtail the spread of infectious diseases. It is the time period between the infection of pathogen/exposure of the virus and the onset of clinical symptoms (Brookmeyer 1998). The main clinical symptoms of COVID-19 are characterized as fever, cough, myalgia or fatigue, expectoration, and dyspnea (Li et al. 2020a, b). The symptoms may differ among the infected individuals with the severity of the disease (CDC 2020). Figure 1 describes the progression of COVID-19 in a host or infected person from the exposure of the virus to the recovery or death. There are basically two phases of infection in the host, i.e., the subclinical phase and the clinical phase. The infected person can spread the infection to others, once the latent period is over, with the onset of infectiousness. The latent period can be shorter or longer than the incubation period. Literature suggests that in case of mild and asymptomatic transmission of COVID-19, the latent period (time from exposure to onset of infectiousness) is more likely to be shorter than the incubation period (Pollán et al. 2020; He et al. 2020; Hu et al. 2020). The SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viruses are zoonotic and belong to the same subfamily ‘Coronavirinae’ (Yan et al. 2020). The incubation period of SARS [mean: 5 days, range 2–14 days] (Varia et al. 2003) and MERS [mean: 5–7 days, range 2–14 days] (Virlogeux et al. 2016) are also found to be quite similar, but there are not very precise estimates available for SARS-Cov-2.

Fig. 1.

Progression of COVID-19 in a host/infected person

The incubation period has a crucial role in surveillance, monitoring, and modelling of infectious disease. The transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 is very high, hence in the lack of any reliable vaccines, measures such as active monitoring, quarantine, isolation etc. become the only really effective measures for curtailing the spread of virus. Knowledge about the incubation period helps in forming policy for quarantine and other interventions (Lessler et al. 2009). In addition, it helps in active monitoring of people having higher exposure and also in determining the length of active monitoring, which saves resources. The incubation period is an aid for defining the time period for which contact tracing is to be done. Robust estimation of the incubation period will also lead to the potential source of infection (Ahrens and Pigeot 2014). Knowledge about the incubation period, along with serial interval and other measures, will be helpful in checking the further spread of the infection, as reports have suggested that we might have to live with COVID 19, following the norms of social distancing, travel restrictions, and quarantine unless any vaccine is developed (Nussbaumer-Streit et al. 2020).

With the passage of time, new studies are coming up, and inclusion of them in the analysis will improve the estimates of the incubation period. There are various estimates of incubation period calculated through different statistical models. In that case, this review can help in understanding the different aspects of incubation period for COVID-19, including the method of estimation and meta-analysis, which will yield a statistically pooled estimate of the incubation period for COVID-19. The objective of the study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the existing literature about the incubation period of COVID-19.

Methodology

This review followed the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (Stroup et al. 2000). The outcome defined in the study was the time in days from the exposure or infection to the onset of clinical symptoms in the infected individuals. Firstly, an initial search was carried out for the studies, which were then screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria. The required data were extracted from the selected studies for the statistical synthesis of results. The detailed selection of studies in this present review and the required data extraction from the selected studies is described in this section.

Search strategies

The literature related to the incubation period of COVID-19 was searched through several research databases, including Scopus, PubMed, Science Direct, and Google Scholar. The literature search for the incubation period was performed using the combination of keywords such as “COVID-19 and Incubation period”, “Coronavirus and Incubation period,” and “2019-nCoV and Incubation period”. A manual search was also performed through the reference list of articles selected to avoid any possible omission of eligible study. The search incorporated all the studies related to the incubation period of COVID-19 irrespective of their study area and time period for data collection.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

After initial search and screening, inclusion and exclusion criteria were set for the selection of the final studies. Inclusion criteria for selecting the studies were: a) the study must be published in the English language, b) the incubation period must be calculated on the clinical data of developing symptoms, and c) the Incubation period should be one of the primary outcomes of the study. Exclusion criteria for the studies were decided as: a) duplicate studies, b) the incubation period being taken as an input from another study.

Data extraction from the selected studies

After selecting the studies by accomplishing inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extraction was carried out from the included studies. The name of the first author, area of study, time period for data collection, methodology adopted to estimate incubation period, estimate for the incubation period, and its 95% confidence interval were extracted from the selected studies. Ninety-five percent confidence interval was estimated for the studies reporting mean with standard deviation by using the following formula, which is generally used to calculate the 95% confidence interval for any parameter:

where µ = mean incubation period, s = standard deviation, and n = sample size of the study. Some studies reported only median with inter-quartile range or range. Mean and the standard deviation was calculated for such studies by using an appropriate approximation for the consistency in synthesizing the results for meta-analysis (Hozo et al. 2005; Wan et al. 2014).

Statistical analysis

All the meta-analyses were performed using Stata 14.1 software. The pooled effect size was calculated using fixed effect and random effects models. The heterogeneity between the studies was examined by Cochran’s Q statistic, and was quantified by Higgins & Thompson’s I2 statistic and Tau-squared (τ2). For Cochran’s Q statistics, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and an I2 > 75% was considerable heterogeneity. The bias introduced in the meta-analysis by small-study effects was tested by Egger’s and Begg’s tests at 5% level of significance. The forest plot for the meta-analysis was plotted by using the random-effects model. A funnel plot at 95% confidence interval was also plotted to testify the publication bias in the meta-analysis.

Results

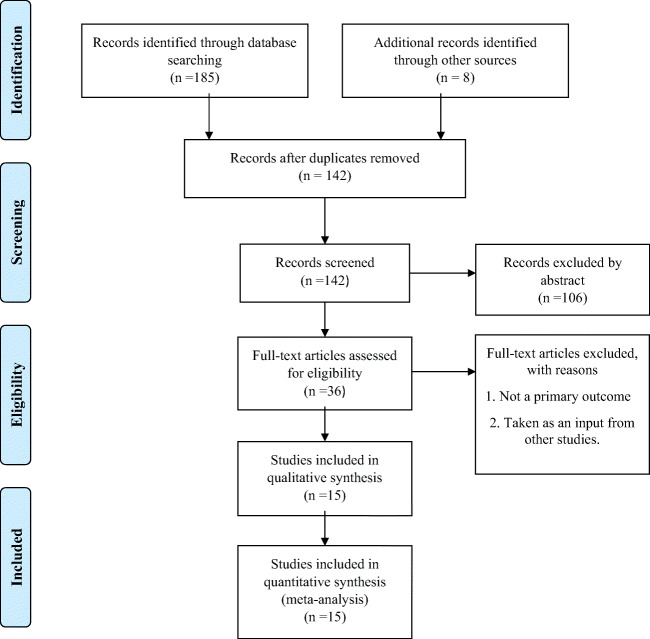

A total of 185 studies were found through the initial search on the databases. Fifteen studies with 16 estimates of the incubation period were selected after implementing inclusion and exclusion criteria as mentioned earlier. The incubation period for COVID-19 is still being explored worldwide; therefore, we included the published literature in peer-reviewed journals and available preprint on the same. Figure 2 demonstrates the flow chart for selecting the final studies, which were selected for qualitative and quantitative synthesis.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart for the selection of studies in systematic review and meta-analysis

Review of the included studies in meta-analysis

Table 1 describes the data extracted from the included studies for the meta-analysis of the incubation period of COVID-19. Since the outbreak of COVID-19 emerged from China, almost all studies for the incubation period have been taken from China and its different provinces; one study was from South Korea, and another one from Saudi Arabia. The longest incubation period in the included studies was 8.98 days (7.98, 9.90) (Xiao et al. 2020), whereas the lowest incubation period was 3.90 days (1.12, 6.68) (Ki 2020). The sample size for estimating the incubation period varies considerably from seven (Ki 2020) to 2555 (Xiao et al. 2020). Most of the studies used some parametric distribution to estimate the mean of the incubation period, including Weibull and lognormal distribution. Some studies used the basic distribution of time periods to estimate the mean of the incubation period. A study used Monte Carlo simulation to obtain the distribution of incubation period (Men et al. 2020), while another study used maximum likelihood estimation to obtain the same (Leung 2020). The time period for collecting data for the estimation of the incubation period in the included studies was from the start of the pandemic to 31 March, 2020.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies in the meta-analysis of incubation period for COVID-19

| Study | Area of study | Time period for data | Methodology | Sample size | Incubation period | LL* | UL* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lauer et al. 2020 | Outside China | 4 Jan–24 Feb | Pooled analysis | 181 | 5.10 | 4.50 | 5.80 |

| Li et al. 2020a, b | China | Up to 22 Jan | Fitting a log normal distribution | 10 | 5.20 | 4.10 | 7.00 |

| Backer et al. 2020 | Wuhan, China | 20 Jan–28 Jan | Fitting a Weibull distribution | 88 | 6.40 | 5.60 | 7.70 |

| Guan et al. 2020 | China | Up to 31 Jan | Interval between the potential date of transmission and symptom onset | 291 | 4.33 | 3.91 | 4.33 |

| Leung 2020 | Hubei, China | 20 Jan–7 Feb | Maximum likelihood estimation | 54 | 6.90 | 5.81 | 7.99 |

| Linton et al. 2020 | Chinai including Wuhan | Up to 31 jan | Doubly interval-censored likelihood function | 158 | 5.60 | 5.00 | 6.30 |

| Linton et al. 2020 | China( excluding Wuhan | Up to 31 Jan | Doubly interval-censored likelihood function | 52 | 5.00 | 4.20 | 6.00 |

| Liu et al. 2020 | China | Up to 23 Jan | Basic distribution of time intervals | 839 | 4.80 | 4.62 | 4.98 |

| Men et al. 2020 | China | 29 Dec–5 Feb | Monte Carlo simulation | 59 | 5.84 | 5.09 | 6.59 |

| Qin et al. 2020 | China | Up to Feb 15 | Fitting a Weibull distribution | 1211 | 8.62 | 8.02 | 9.28 |

| Sanche et al. 2020 | China outside Hubei | Jan 15–Jan 30 | Basic distribution of time intervals | 140 | 4.20 | 3.50 | 5.10 |

| Xia et al. 2020 | China outside Wuhan and Hubei Province | Up to Feb 16 | Fitting a Weibull distribution | 106 | 4.90 | 4.40 | 5.40 |

| Xiao et al. 2020 | China | Up to 16 Feb | Fitting a Weibull distribution | 2555 | 8.98 | 7.98 | 9.90 |

| Yang et al. 2020 | Hubei, China | 20 Jan–29 Feb | Fitting a Weibull distribution | 181 | 5.40 | 4.80 | 6.00 |

| Alsofayan et al. 2020 | Saudi Arabia | 1 Mar–31 Mar | Basic distribution of time intervals | 309 | 6.00 | 5.72 | 6.28 |

| Ki 2020 | South Korea | Jan 15–Feb 8 | Basic distribution of time intervals | 7 | 3.90 | 1.12 | 6.68 |

*LL — lower limit, UL — upper limit for 95% confidence interval

Summary statistics for meta-analysis

Table 2 represents the summary statistics for the meta-analysis of the incubation period for COVID-19. The pooled estimate for the incubation period from the meta-analysis was 5.74 days (5.18, 6.30) from the random effects model and 5.12 days (5.01, 5.22) from the fixed effects model. The heterogeneity between the studies was found to be 95.5% by Thompson’s & Higgins I2 statistic, which shows considerable heterogeneity. The pooled estimate from the random effects model is more appropriate due to presence of considerable heterogeneity in the included studies in the meta-analysis (Borenstein et al. 2007). Cochran’s Q statistic was statistically significant at 5% level of significance, also suggesting the evidence for heterogeneity in the included studies for meta-analysis. The value of Tau squared (τ2) was found to be 1.12. The Egger’s and Begg’s tests revealed that there is no potential bias introduced in the meta-analysis of included studies due to small study effects (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary statistics for meta-analysis

| Overall effect size | |

| Fixed effect model | 5.12 (5.01, 5.22) |

| Random effect model | 5.74 (5.18, 6.30) |

| Test for heterogeneity | |

| I2 Statistic | 95.2% |

| Tau squared (τ2) | 1.1168 |

| Cochran’s Q | 313.27* |

| Bias in the studies | |

| Egger’s test# | 0.072 |

| Begg’s test# | 0.367 |

* p < 0.05

# H0: there are no small study effects

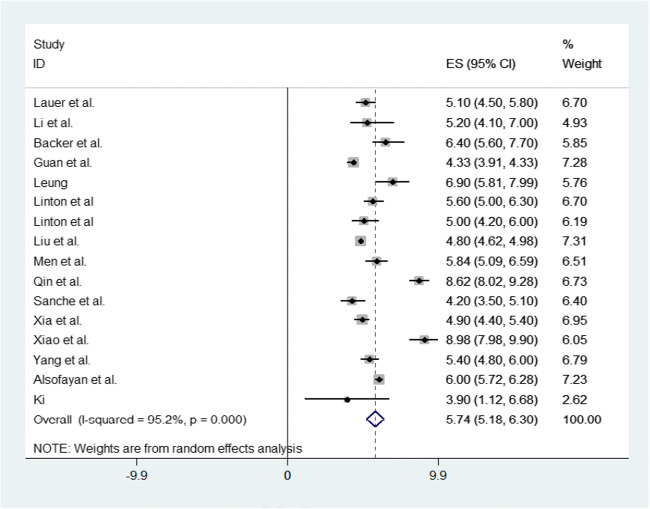

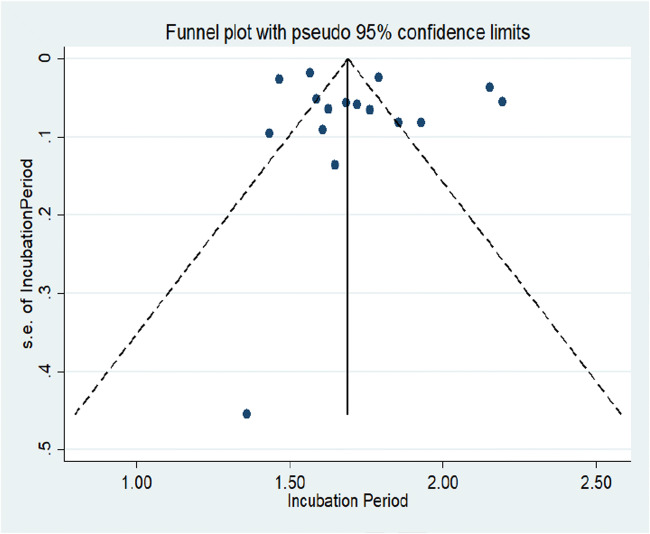

Figure 3 represents the forest plot of the incubation period for COVID-19, which provides the effect size of individual studies with a pooled estimate of the incubation period by random effects model. Figure 4 represents the funnel plot with 95% confidence interval for the meta-analysis, suggesting no potential publication bias in the included studies (Sterne and Harbord 2004). The standard error for all the included studies in the meta-analysis was very low except for a study conducted by Ki 2020 where the highest standard error was observed.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for the meta-analysis of incubation period for COVID-19

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot with a 95% confidence interval for included studies in the meta-analysis

Discussion

This systematic review provides current evidence for the incubation period of COVID-19, and the meta-analysis statistically synthesizes the comparable studies to yield a pooled estimate of the incubation period. This review included 16 estimates of the incubation period from data on 6300 patients from different regions through various methods. The pooled estimate of the incubation period [5.74 days (5.18, 6.30)] for COVID-19 is slightly higher than the incubation period of human coronavirus [3.2 days (2.8, 3.7)] and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus [4.0 days (3.6, 4.4)] (Lessler et al. 2009). The incubation period varies with the age of COVID-19 cases, where young (less than 14 years) and old (more than 64 years) age groups have higher incubation periods compared to cases in the age group 15–64 years (Yang et al. 2020). The incubation period is a key parameter in planning the preventive and control measures for any infectious disease. The maximum incubation period is particularly important in contact tracing and in deciding the period of home isolation and quarantine to curtail the growth of infection in the population (WHO 2003, 2020e).

The estimation of the incubation period for any infectious disease has various theoretical aspects that are equally important to understand in producing an unbiased estimate of the incubation period. The choice of a correct statistical distribution is essential for estimating the robust parameters for the incubation period. Most of the studies included in the meta-analysis used different parametric distributions for calculating the summary measures, which leads to reliable estimates of the incubation period. The studies included in the review represented well-characterized cases, i.e., cases where exposure window and date of symptom onset were clearly defined. The pooled estimate of the incubation period is generalizable in the population because it is the result of interaction between the host and the infection only, unlike serial interval, which is affected by the frequency of contacts in the population. The length of the incubation period can also be correlated to the severity of the disease, where more severe cases have a relatively smaller incubation period (Virlogeux et al. 2015). Information on the incubation period along with serial interval can be used to check the asymptomatic transmission of COVID-19 in the community (Fraser et al. 2004). For various medication procedures the incubation period is important, as few medicines are more effective if given just before or after the onset of symptoms (Twu et al. 2003).

The pooled estimate from the meta-analysis is also consistent with earlier studies (Men et al. 2020; Linton et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020). The Egger’s and Begg’s tests are the most commonly used tests for detecting the bias in studies included for meta-analysis (van Enst et al. 2014), which suggested the presence of no potential bias in the present meta-analysis. Hence this meta-analysis of the incubation period for COVID-19 provides a reliable estimate and can be useful in understanding the transmission of the disease. However, the investigation on transmission dynamics of COVID-19 is still under progress across the world, and more reliable estimates can be developed with broader geographical scope. The study of the incubation period also needs to incorporate the factors influencing the incubation period, which can provide insights in understanding the mechanism of the virus. This review suggests that a more detailed investigation of the incubation period in various exposure groups would be worthwhile.

Authors contribution

Conceptualization — Laxmi Kant Dwivedi & Balram Rai. Literature review and selection of studies — Balram Rai & Anandi Shukla. Statistical analysis — Balram Rai & Laxmi Kant Dwivedi. Writing, original draft — Anandi Shukla & Balram Rai. Writing, review & editing — Laxmi Kant Dwivedi. Supervision — Laxmi Kant Dwivedi.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

This study is based on secondary data, so no ethical approval was required.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Balram Rai, Email: balramrai009@gmail.com.

Anandi Shukla, Email: Shukla.anandi867@gmail.com.

Laxmi Kant Dwivedi, Email: laxmikdwivedi@gmail.com.

References

- Ahrens W, Pigeot I, editors. Handbook of epidemiology. New York: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alsofayan YM, Althunayyan SM, Khan AA, Hakawi AM, Assiri AM. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: a national retrospective study. J Infect Public Health. 2020;3(7):920–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backer JA, Klinkenberg D, Wallinga J. Incubation period of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections among travellers from Wuhan, China, 20–28 January 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(5):2000062. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.2000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges L, Rothstein H (2007) Meta-analysis: fixed effect vs random effects. Meta-analysis.com. Retrieved from https://www.meta-analysis.com/downloads/Meta-analysis%20fixed%20effect%20vs%20random%20effects%20072607.pdf. Accessed on 5 June 2020

- Brookmeyer R. Incubation period of infectious diseases. Encyclopedia of biostatistics, vol 3. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 2011–2016. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2020) Interim clinical guidance for management of patients with confirmed 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection. CDC, Atlanta, GA. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html. Accessed on 10 Dec 2020

- Fraser C, Riley S, Anderson RM, Ferguson NM. Factors that make an infectious disease outbreak controllable. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101(16):6146–6151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307506101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382(18):1708–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- He G, Sun W, Fang P, Huang J, Gamber M, Cai J, Wu J. The clinical feature of silent infections of novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in Wenzhou. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):1761–1763. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Song C, Xu C, Jin G, Chen Y, Xu X, Ma H, Chen W, Lin Y, Zheng Y, Wang J. Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with COVID-19 screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Science China Life Sciences. 2020;63(5):706–711. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ki M. Epidemiologic characteristics of early cases with 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) disease in Korea. Epidemiology and Health. 2020;42:e2020007. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, Jones FK, Zheng Q, Meredith HR, et al (2020) The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med 172(9): 577–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lessler J, Reich NG, Brookmeyer R, Perl TM, Nelson KE, Cummings DA. Incubation periods of acute respiratory viral infections: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(5):291–300. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70069-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung C. Estimating the distribution of the incubation period of 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infection between travelers to Hubei, China and non-travelers. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.13.20022822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LQ, Huang T, Wang YQ, Wang ZP, Liang Y, Huang TB, Zhang HY, Sun W, Wang Y. COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):577–583. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y ... Xing X (2020b) Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. New Engl J Med 382:1199–1207. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Linton NM, Kobayashi T, Yang Y, Hayashi K, Akhmetzhanov AR, Jung SM, et al (2020) Incubation period and other epidemiological characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infections with right truncation: a statistical analysis of publicly available case data. J Clin Med 9(2):538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu T, Hu J, Kang M, Lin L, Zhong H, Xiao J, et al (2020) Transmission dynamics of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3526307 or 10.2139/ssrn.3526307

- Men K, Wang X, Li Y, Zhang G, Hu J, Gao Y, Han H. Estimate the incubation period of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.24.20027474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, Chapman A, Persad E, Klerings I, ... Gartlehner G (2020) Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4(4):CD013574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pollán M, Pérez-Gómez B, Pastor-Barriuso R, Oteo J, Hernán MA, Pérez-Olmeda M, et al (2020) Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study. The Lancet 396(10250):535–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Qin J, You C, Lin Q, Hu T, Yu S, Zhou X-H. Estimation of incubation period distribution of COVID-19 using disease onset forward time: A novel cross-sectional and forward follow-up study. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.06.20032417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, Ke R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1470–1477. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JA, Harbord RM. Funnel plots in meta-analysis. Stata J. 2004;4(2):127–141. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0400400204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twu SJ, Chen TJ, Chen CJ, et al. Control measures for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:718–720. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.030283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Enst WA, Ochodo E, Scholten RJ, Hooft L, Leeflang MM. Investigation of publication bias in meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy: a meta-epidemiological study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varia M, Wilson S, Sarwal S, McGeer A, Gournis E, Galanis E. Investigation of a nosocomial outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Toronto, Canada. CMAJ. 2003;169(4):285–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virlogeux V, Fang VJ, Wu JT, Ho LM, Peiris JM, Leung GM, Cowling BJ. Incubation period duration and severity of clinical disease following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Epidemiology. 2015;26(5):666. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virlogeux V, Fang VJ, Park M, Wu JT, Cowling BJ. Comparison of incubation period distribution of human infections with MERS-CoV in South Korea and Saudi Arabia. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35839. doi: 10.1038/srep35839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2003) Update 49 — SARS case fatality ratio, incubation period. WHO, Geneva. https://www.who.int/csr/sars/archive/2003_05_07a/en/. Accessed on 4 June 2020

- World Health Organization (2020a) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): weekly epidemiological update 22 Dec, 2020. WHO, Geneva. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update---22-december-2020, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200705-covid-19-sitrep-167.pdf?sfvrsn=17e7e3df_4. Accessed on 25 Dec 2020

- World Health Organization (2020b) Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Situation report 1. WHO, Geneva. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=20a99c10_4. Accessed on 5 July 2020

- World Health Organization (2020c) COVID-19 as a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) under the IHR. WHO, Geneva. https://extranet.who.int/sph/covid-19-public-health-emergency-international-concern-pheic-under-ihr. Accessed on 5 July 2020

- World Health Organization (2020d) WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 — 11 March 2020. WHO, Geneva. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-11-march-2020. Accessed on 5 July 2020

- World Health Organization (2020e) COVID-19 Strategy Update — 14 April 2020. WHO, Geneva. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/covid-strategy-update-14april2020.pdf?sfvrsn=29da3ba0_19. Accessed on 10 July 2020

- Xia W, Liao J, Li C, Li Y, Qian X, Sun X, et al (2020) Transmission of corona virus disease 2019 during the incubation period may lead to a quarantine loophole. MedRxiv.10.1101/2020.03.06.20031955

- Xiao Z, Xie X, Guo W, Luo Z, Liao J, Wen F, Zhou Q, Han L, Zheng T. Examining the incubation period distributions of COVID-19 on Chinese patients with different travel histories. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020;14(4):323–327. doi: 10.3855/jidc.12718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Shin WI, Pang YX, Meng Y, Lai J, You C, et al (2020) The first 75 days of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak: recent advances, prevention, and treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(7):2323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yang L, Dai J, Zhao J, Wang Y, Deng P, Wang J. Estimation of incubation period and serial interval of COVID-19: Analysis of 178 cases and 131 transmission chains in Hubei province, China. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:E117. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.