Dear Editor,

Preclinical and observational studies suggest early recognition and treatment of sepsis can reduce avoidable deaths.1 There is growing focus on identification of patients with sepsis during prehospital care. Emergency medical services (EMS) personnel provide prehospital care to tens of millions each year, and more than half of sepsis patients.2 Despite this opportunity for early recognition and treatment, EMS lack validated tools to identify or risk-stratify sepsis patients.

Existing prehospital risk scores have only moderate discrimination between patients with and without sepsis. A simulation shows, however, that addition of biomarkers could improve classification of sepsis beyond prehospital clinical data alone.3 If such prehospital tools existed, sepsis care could be advanced through i.) initiation of specific treatments before hospital arrival, ii.) guiding treatment intensity in the Emergency Department (ED), or iii.) identification of patients for transport to referral centers.

We performed a 6-month prospective cohort study of non-trauma, non-arrest prehospital patients at risk for sepsis, collecting blood samples at the time of prehospital intravenous (IV) catheter placement. We measured biomarkers of host response: IL-6, IL-10, TNF, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, troponin, and point-of-care lactate. Prehospital vital signs were used to calculate a validated clinical risk score.4 The primary outcome was community sepsis, defined as suspected infection and acute organ dysfunction using the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) greater than 2 within 48 hours of hospital admission.5 We compared the discrimination and calibration of a prehospital sepsis model that included the clinical risk score alone and after the addition of a best performing panel of prehospital biomarkers.

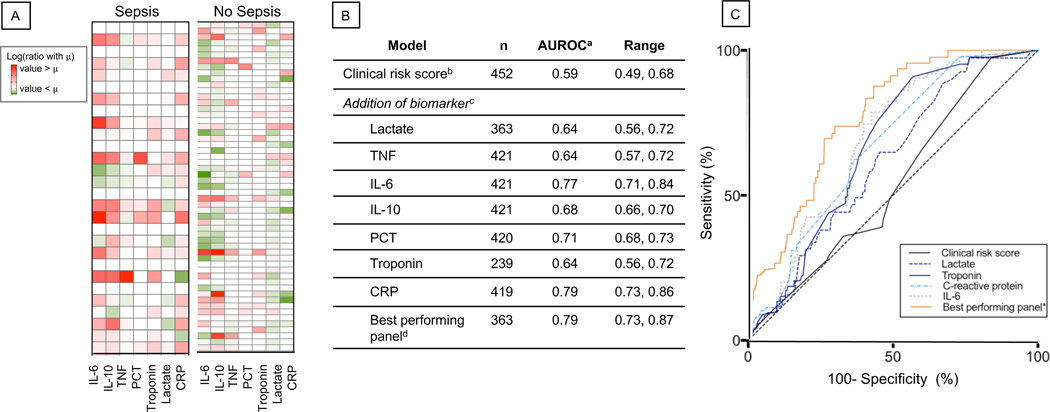

Among 452 unique prehospital patients (mean age 65, [SD, 18] years; 224 [49%] male), community sepsis was present in 57 (13%). Plasma concentrations of procalcitonin, IL-6, IL-10, C-reactive protein and troponin were higher among patients with community sepsis compared to those without sepsis (Figure 1, P < .01). A model for community sepsis using the clinical risk score alone had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.59 (95% CI, 0.51–0.71), and increased to 0.79 (95% CI, 0.69–0.87) when adding a best performing panel of IL-6, TNF, troponin and point-of-care lactate (Figure 1, P < .01). Net reclassification improved after the addition of biomarkers (continuous NRI = 0.81, 95% CI, 0.46–1.24, eFigure 4). The model was well calibrated and superior to the clinical risk score alone (Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic, P > 0.05, eFigure 6). Decision curves demonstrated that the combined model had a higher net benefit compared to screening using the clinical risk score alone, across all plausible risk thresholds.

Figure 1.

(A) Heatmap of log ratio of mean prehospital biomarker value for each group to the grand mean prehospital biomarker value for the entire cohort. Columns represent patients who met Sepsis-3 criteria within 48 hours and those who did not. Red represents a greater mean biomarker value for the entire cohort, whereas green represents a lower value. (B) Area under receiver operator characteristic curve (AUROC) value for models of sepsis comparing a baseline model of clinical risk score versus models with clinical risk score and single prehospital biomarker. Reported value is mean value calculated from AUROC derived from modeling in 10 imputed datasets; range represents minimum and maximum values across imputed datasets. Clinical risk score calculated using first vital signs measured by EMS. Best performing panel includes clinical risk score, troponin, lactate, C-reactive protein and IL-6. (C) Corresponding receiver operator characteristic curve (ROC) for each baseline model of clinical risk score versus models with clinical risk score and single prehospital biomarker of host response. Best performing panel includes clinical risk score with troponin, lactate, C-reactive protein and IL-6. Solid black line from origin represents an AUROC of 0.5, and thus, no diagnostic utility. Abbreviations: IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; PCT, procalcitonin; CRP, C-reactive protein; AUROC, area under receiver operating characteristic curve

In conclusion, we demonstrate that prehospital biomarkers of host response improve the discrimination of community sepsis on arrival compared to prehospital clinical signs alone. Models that included prehospital measurement of IL-6, troponin, point-of-care lactate and C-reactive protein were the best performing. These findings highlight the potential role of biomarkers measured prior to hospital arrival to speed the system of care for sepsis recognition.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HD, et al. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. New Engl J Med. 2017;376:2235–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seymour CW, Band RA, Cooke CR, et al. Out-of-hospital characteristics and care of patients with severe sepsis: A cohort study. J Crit Care. 2010;25:553–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seymour CW, Kahn JM, Cooke CR, et al. Prediction of critical illness during out-of-hospital emergency care. JAMA. 2010;304:747–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kievlan DR, Martin-Gill C, Kahn JM, et al. External validation of a prehospital risk score for critical illness. Crit Care. 2016;20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.