Abstract

Psychologists working within forensic mental health (FMH) services face challenges around supporting clients’ informed consent when engaging in psychological assessment and treatment. Given that there is little research in this area, this qualitative study interviewed ten forensic inpatients from a low secure FMH service, to determine the impact of any perceived coercion to engage with psychologists. Interviews were transcribed and subject to Thematic Analysis. Three over-arching themes emerged from the analysis: ‘Awareness of Coercive Power’, ‘Experiencing and Responding to Coercion’ and ‘Psychological Treatment is Helpful, But…’. Participants perceived coercion to engage with psychologists. Perceived coercion led to psychological distress, wanting to resist, and superficial engagement. Despite this, therapeutic alliance was established with the psychologist but the quality of the therapeutic alliance was compromised. The findings have implications for psychologists working in FMH services. Suggestions for reducing perceived coercion and future directions for research are discussed.

Keywords: coercion, forensic mental health, informed consent, power, psychological assessment, psychological treatment, therapeutic alliance

Introduction

Low secure forensic mental health (FMH) services provide assessment, treatment and secure accommodation for mentally disordered offenders (MDOs), alleviating distress or disability, minimising risk and equipping MDOs with the necessary coping and interpersonal skills for effective community reintegration (Mann, Matias, & Allen, 2014). However, there is a conflict between providing a therapeutic setting, supporting recovery-focused care and treatment approaches, and minimising coercive practices, against managing risk in order to maintain the security and protection of MDOs, staff and the general public (Green, Batson, & Gudjonsson, 2011; Mann et al., 2014; Miles, 2016). Evidence-based psychological interventions, delivered individually or within group settings, have become core to the practice of risk management and reduction in FMH (Blackburn, 2004), and psychologists working in these settings possess a ‘dual role’, balancing the provision of traditional psychological services simultaneously with the role of expert risk assessment and management (Baker & Moore, 2006).

Forensic inpatients typically exhibit little desire to engage in psychology or to change risk-related behaviours (Baker & Moore, 2006) despite an expectation from key stakeholders that they will demonstrate a reduction in risk through participation in psychology, in order to regain their freedom (Edworthy, Sampson, & Völlm, 2016; Mann et al., 2014). Often, their attendance is leveraged with external reinforcements, such as early discharge and leave entitlement or simply motivated by an awareness that non-compliance will result in negative consequences, leading to coerced ‘voluntary’ participation (Day, Tucker, & Howells, 2004; Ross, Polaschek, & Ward, 2008).

Coercion is a widely practised phenomenon across mental health systems, and the frequency of its use is steadily increasing (Mayoral & Torres, 2005; Sashidharan & Saraceno, 2017). Investigation into the impact of coercion remains sparse, which may be related to challenges in definition (Campbell & Davidson, 2009). Some have defined coercion as the use of authority that can override the choices of another (O’Brien & Golding, 2003). Others propose that coercion exists on a continuum composed at one end of informal pressure (e.g. friendly persuasion or interpersonal pressure), up to the control of resources (i.e. leverage or threats of negative sanctions) and use of restraint or force at the formal end (Diamond, 1996).

To date, the most robust considerations have acknowledged coercion as an internal subjective state aroused when a perceived threat, whether intended or misconstrued, motivates a choice of action or non-action (Newton-Howes, 2010; Szmukler & Appelbaum, 2008). The term perceived coercion has been used throughout the empirical literature to demarcate a ‘grey area’ that exists between objective events that compel a specific action and an internal subjective feeling that may, or may not, consequently arise (Eriksson & Westrin, 1995). Common to all conceptualisations is that perceived coercion involves a degree of autonomy infringement, removes power from another (Foucault & Faubio, 2001 as cited in Norvoll & Pedersen, 2016) and prevents one from providing objective informed consent (Newton-Howes, 2010).

The UK Mental Health Act (1983, 2007) currently permits the use of coercive practices through the deprivation of liberty, freedom of movement and enforced treatments (Hem, Pedersen, Norvoll, & Molewijk, 2015). Advocates argue that coercive interventions provide the necessary treatment to regain mental stability (Appelbaum, 1985; Geller, 1991), while coerced psychological interventions can minimise risk, recidivism and further victimisation (Day et al., 2004). Critiques would argue that coercion is associated with untoward consequences such as distrust, avoidance or withdrawal from treatment (Cascardi & Poythress, 1997) and damage to any therapeutic alliance (Kisely, Campbell, & Preston, 2005).

Research has shown that forensic inpatients report greater feelings of powerlessness, oppression and perceived coercion than those in other mental health settings (Kallert, 2008; Livingston & Rossiter, 2011; Livingston, Rossiter, & Verdun-Jones, 2011; Mezey, Kavuma, Turton, Demetriou, & Wright, 2010). Despite these findings, few studies have addressed the issue of coercion in FMH services (Hui, Middleton, & Völlm, 2013; McKenna, Simpson, & Coverdale, 2003). Instead, the literature has mainly explored coercion in relation to psychiatric interventions (e.g. involuntary hospitalisation, restraint, seclusion and enforced medication) and Community Treatment Orders (CTOs).

CTOs authorise compulsory treatment in the community under the Mental Health Act (MHA, 2007) and are intended to prevent relapse and risk of harm to self or others. Failure to comply with treatment conditions results in enforced recall to hospital (Department of Health, DoH, 2008). Churchill, Owen, and Singh (2007) note that those with criminal or violent histories are often subject to CTOs. Despite being intended as a less restrictive approach than hospitalisation, some argue that CTOs merely extend the experience of coercion (Trueman, 2003). In a study exploring participants’ experiences, CTOs are described as a restriction on their liberty, intrusive and a power exercised over them, and their non-compliance is viewed by their care providers as a sign of illness (Canvin, Rugkåsa, Sinclair, & Burns, 2014). Feelings of being coerced, not being listened to or fully informed of CTO procedures, and decisions being of control are highlighted as shared experiences elsewhere (Corring, O’Reilly, & Sommerdyk, 2017). Another study reported that it was the threat of recall/loss of freedom that motivated participants’ engagement with treatment (Stroud, Banks, & Doughty, 2015). Moreover, warnings about the consequences of non-compliance have been shown to enhance perception of coercion (Swartz, Wagner, Swanson, Hiday, & Burns, 2002) whilst use of leverages reportedly mitigates or enhances perceived coercion (Pridham et al., 2016). That said, some participants discussed how the CTOs provided a ‘safety net’, with close supervision and high levels of support keeping them well with community treatment being preferred over hospitalisation (Pridham et al., 2016; Stroud et al., 2015).

Findings have noted that forensic inpatients subject to coerced psychiatric interventions appear to habituate to the high levels of coercion within the FMH system and report a sense of powerlessness, and that threats and the use of force are associated with decreased compliance, higher levels of perceived coercion and subsequent feelings of anger (McKenna et al., 2003; Skelly, 1994). However, coerced psychiatric interventions differ from coerced psychological interventions in that the latter cannot physically force an individual to attend or actively engage (Day et al., 2004).

Psychologically informed rehabilitative programmes in custodial settings have become an acceptable course of action (Day et al., 2004) and have been consistently evidenced to reduce risk and recidivism (Nunes, Cortoni, & Serin, 2010; Wilson, Bouffard, & MacKenzie, 2005). That said, coercing offenders to engage in psychological interventions results in reduced efficacy and poorer treatment outcomes (Parhar, Wormith, Derkzen, & Beauregard, 2008). Offenders who perceive coercion have also been noted to have more resistant or hostile attitudes (Shearer & Ogan, 2002) and lower levels of motivation on entering treatment (Marshall & Hser, 2002), although this has been noted to decline over the course of treatment (Hogan, Barton-Bellessa, & Lambert, 2015) demonstrating that positive therapeutic alliances can be established (Kennealy, Skeem, Manchak, & Eno Louden, 2012).

There is only very limited research into exploring the perception of coercion and its impact on psychological interventions and the therapeutic alliance in FMH services. For example, Schafer and Peternelj-Taylor (2003) found that some inpatients in a Canadian FMH service felt coerced into psychological treatment, despite engagement being voluntary and having full knowledge of their right to withdraw. Many of those who felt coerced expressed entering treatment solely for recognition, although motivation to engage improved over time. The facilitators’ position in the system in enforcing security and policy, as well as their power in controlling future possibilities, impacted on compliance and the quality of the therapeutic alliance. Similarly, Mason and Adler (2012) found inpatients in a United Kingdom high secure FMH service felt unable to make autonomous decisions about participating in a psychological therapy group due to their perceived lack of power and control, resulting in a sense of perceived coercion and learned helplessness, which led to superficial engagement only in order to progress towards discharge.

Finally, Ellis (2013) examined therapeutic alliance in a United Kingdom medium secure FMH service, noting that barriers to establishing this included being ‘forced’ to meet with the psychologist, a lack of choice, adverse consequences associated with non-compliance, persistent harassment following their refusal and the perceived power of the psychologist and their accountability to the legal system. A fear of disclosing information to the psychologist was also reported, due to potential legal consequences that might arise, preventing open and honest disclosures. Nevertheless, therapeutic alliance could be established despite these barriers, which was associated with therapeutic gains. Consequently, the limited literature suggests that coercion is intrinsic to FMH services, and the increasing force of ‘psychological power’ in forensic settings has resulted in growing levels of distrust (Crewe, 2009; Maruna, 2011) and may even have impacted upon psychologists building trusting relationships with clients (Roberts, Geppert, & Bailey, 2002; Ross et al., 2008).

Overall, the literature reporting on perceived coercion has favoured the use of a quantitative methodology (Newton-Howes & Stanley, 2012; Norvoll & Pedersen, 2016), namely through the use of self-report measures with restricted response sets. This has resulted in few qualitative details concerning patients’ experiences of coercion (Prebble, Thom, & Hudson, 2015), and the research to date has explored only medium/high secure FMH services or prisons. Consequently, this study will utilise qualitative methods to explore forensic inpatients’ experiences of perceived coercion to engage with psychological assessment and treatment, in a low secure FMH service. Specifically, the following areas are explored: (a) Is coercion used to promote participation with psychological assessment and treatment?; (b) how do forensic inpatients understand, experience and respond to perceived coercion to engage with psychological assessment and treatment?; and (c) does perceived coercion impact on the therapeutic alliance with psychologists and the potential for treatment gains?

Method

Design

This study utilised a cross-sectional design with an in-depth interview, an approach frequently employed in qualitative research (Bryman, 2015). This allows an inductive and exploratory approach, drawing meaning from the experiences and viewpoints of participants to generate new ideas and concepts, as opposed to testing or confirming existing theory (Creswell & Clark, 2007).

Measures

The development of the interview schedule was informed by the MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES), a self-report questionnaire designed with the purpose of measuring perceived coercion during the hospital admission process (MacArthur Research Network on Mental Health & Law, 2001). The AES was adapted to develop an interview schedule that made specific reference to participants’ experiences of coercion in relation to psychological assessment and treatment, and is available from the authors on request.

The semi-structured interview schedule designed for the present study was exploratory, using open-ended questions to prompt participants to reflect on their thoughts, feelings and experiences of coercion concerning psychological assessment and treatment. Participant responses dictated any follow-up questions, allowing the researcher to acquire information of interest without explicitly controlling the direction or content of interviews (Morse & Field, 1995), and explore novel topics that emerged from participants’ narratives. However, the initial standardised question set allowed comparison of participants’ responses across the data set (Minichiello, Madison, Hays, Courtney, & St. John, 1999) and focused on participants’ experiences of undertaking psychological assessment or treatment as well as (a) approaches employed by staff to promote engagement; (b) factors influencing engagement, (c) thoughts and feelings around their engagement; (d) ability to exercise autonmony and control during sessions and (e) the quality of the therapuetic alliance with the psychologist. The interview schedule questions were informed by these areas of focus and piloted with a subset of the sample (n = 2) to assess suitability and relevance of the question set. Following pilot participant comments, revisions to improve clarity of questions and remove repetition occurred. Pilot data provided a rich account of participants’ experiences, answered the research question sufficiently, and were therefore included in the main analysis.

Participants

Participants (n = 10) were recruited from a low secure FMH service based in the south-east of England. A purposive sampling technique was employed, allowing the selection of information-rich participants who were likely to have experienced the phenomena of interest (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000). Purposive sampling is widely used in qualitative research (Palinkas et al., 2015), where aims are centred on exploring individual experience, rather than necessarily generalising findings to a wider population (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

The inclusion criteria specified that all potential participants had declined, had completed or were undertaking psychological assessment or treatment whilst within the FMH service. Those who had declined during their admission may have felt coerced, therefore their accounts were also of value to the present study. All potential participants were deemed by the responsible clinician to be mentally stable, to be of low risk to the external researcher and to have capacity to provide informed consent. Ten of the 20 inpatients (50%) in the unit met study criteria. All participants were male, were aged between 25 and 36 years and had a primary diagnosis of psychosis. All were detained under forensic sections of the Mental Health Act (1983, 2007). The demographic characteristics of the sample as outlined in Table 1 are arguably representative of inpatient forensic populations (Pereira, Dawson, & Sarsam, 2006).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

| Participant characteristic | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Total number of participants | 10 |

| Age in years | |

| 20–29 | 5 |

| 30–40 | 5 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Black | 2 |

| White | 7 |

| Mixed | 1 |

| Primary diagnosis | |

| Schizophrenia | 10 |

| Secondary diagnosis | |

| Personality disorder | 2 |

| Alcohol/substance misuse | 6 |

| Learning disability/autism/ADHD | 2 |

| Index offence | |

| Sexual violence | 1 |

| Other violent crimes | 5 |

| Possession of offensive weapon (firearms) | 1 |

| Theft/burglary | 2 |

| Arson | 1 |

| Legal status | |

| Section 47 (notional 37) | 2 |

| Section 37/41 | 7 |

| Section 48/49 | 1 |

| Length of detention under MHA in months | |

| <6 | 3 |

| 6–12 | 2 |

| 13–19 | 2 |

| 20–30 | 1 |

| >30 | 2 |

Note: ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; MHA = Mental Health Act.

Procedure

To avoid potential participants feeling coerced into participating in this study, the researcher was external to the service and had no involvement in participants’ care or treatment. All inpatients were invited to take part during a community meeting and received an invitation letter outlining the nature of the study and inclusion criteria. Following this, the researcher approached all potential participants over the following week and invited them to attend an individual information session, wherein a more detailed information sheet was discussed. Participants were informed that the study intended to explore their experiences of psychological assessment or treatment, as opposed to their experiences of perceived coercion to engage, as it was considered necessary to withhold this information to reduce bias during interview. Participation was explicitly highlighted as voluntary and confidential (within the limits of risk disclosure) and would have no effect on their multidisciplinary care, legal rights, leave status or privileges, nor would it provide any reward. Following this session, a time period of seven days elapsed (to minimise any perceived coercion to participate) before the researcher met again with those interested in participating and conducted the formal written consent process. A further period of seven days from this meeting to undertaking the interview gave participants another opportunity to withdraw and thereby reduced coercion to take part in the study.

All interviews were conducted over a period of four weeks in May 2017 and took place in a private room located on the unit. Interviews lasted 30–70 min and were recorded using an encrypted Dictaphone. Individual debriefing sessions took place on completion of study. Participants were informed that the purpose of the study was to explore their experience of coercion to engage in psychological assessment and treatment. The opportunity to raise concerns and withdraw was given during debriefing and anonymously by completing a feedback slip attached to their debrief letter. Information about complaints procedures and accessing emotional support was also given.

The interviews were transcribed verbatim. Each audio recording was checked against the respective transcript for accuracy and then destroyed. Identifiable information was removed from all transcripts, and participants were assigned a pseudonym to preserve anonymity. Data were stored in a password-protected file within the FMH service.

Analysis

All transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis, a method used to identify, analyse and report repeated patterns of meaning across a data set without having to be bound to specific theoretical or epistemological positions (Braun & Clarke, 2006). As such, thematic analysis was deemed an appropriate method for this exploratory study as the analysis was intended to be data not theory driven, and the narrative accounts alone were presumed to reflect meaning, experience and the individual’s reality (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Widdicombe & Wooffitt, 1995).

Emergent themes within the data set guided the analysis, minimising the extent to which the preconceptions or theoretical interests of the researcher influenced this process. Themes were identified using the six-stage procedure for thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). Adding to the familiarisation process, which began during the transcription phase, the first stage of the analysis involved repeated reading of the transcripts, during which initial interpretations and ideas for coding were noted. The second stage of analysis entailed further development of these initial codes, and a coding sheet was devised for each interview alongside the respective extracts. The third stage involved identifying relationships between the codes by searching for patterns based on the explicit meaning of participants’ narratives and combining them to produce main themes and sub-themes. The themes were then refined in Stage 4 to ensure that the relevant codes conveyed a similar and coherent pattern allowing for meaningful interpretation, but were distinct and portrayed an accurate reflection of the data set. Stage 5 involved reporting an interpretive analysis detailing the narrative told within individual themes. Consideration was given to how each theme related to the overall story apparent within the data set. The themes were named to depict the essence of their content. Finally, Stage 6 selected data extracts, illustrating key aspects of each theme, to be reported alongside the researcher’s interpretive analysis.

Ethics

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from London (UK) Camberwell – St Giles Research Ethics Committee on 13th April 2017: Reference number 17/LO/0424. The committee expressed concerns of the effects of the study – namely its potential to heighten awareness or feeling of being coerced, which could have an impact on their wellbeing, future care or treatment. In response, a comprehensive debriefing strategy outlined above was designed to address foreseeable issues. Permission for the study to be conducted at the low secure FMH service was granted by the local NHS Research and Development Department/Health Research Authority on the 27 April 2017.

Results

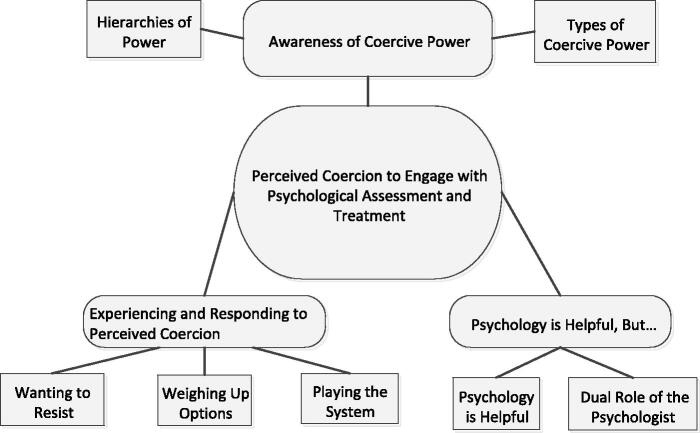

Three overarching themes were identified: ‘awareness of coercive power’, ‘experiencing and responding to perceived coercion’ and ‘psychology is helpful, but . . . ’. The overarching themes and sub-themes are summarised in Figure 1 and are discussed alongside an interpretive narrative and illustrative excerpts provided from the raw data.

Figure 1.

Thematic map of overarching themes and sub-themes.

Awareness of coercive power

This theme depicts participants’ perceptions of the low secure FMH service as one inherently governed by coercive power. It is composed of two subthemes ‘hierarchies of power’ and ‘types of coercive power’.

Participants were acutely aware of the ‘hierarchies of power’ held by key stakeholders and their ability to determine whether they progressed through, or out of, the system. Central to the agenda of stakeholders was treatment adherence, and psychological assessment and treatment were considered by participants to be prioritised within this agenda. With the capacity to uphold hospital detention and leave entitlement, the United Kingdom Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and mental health review tribunals (MHRTs) were ranked the most powerful stakeholders, who viewed engagement with psychological interventions as necessary for improved mental health and risk reduction. Consequently, participants felt that their engagement in psychological assessment and treatment would influence their ability to progress through the system:

. . . one of the things that people look at is how much you are engaging. And erm, if you’re not engaging then it has a negative effect on you being able to progress. . . . So, in a way that’s a bit of pressure in itself because you have to show that you’re engaging. . . . And you know, when they are considering to apply to the MoJ for your leave and stuff like that, they take into consideration what progress you’ve actually made. If you’re not doing enough, it could affect your leave. (Tyrone, P19/L358-377)

This account makes clear the pressure experienced to demonstrate conformity with the systems expectations, in order to acquire associated benefits such as leave. This was a consensually held perception among participants, many of whom feared that non-engagement would ‘look bad’ or be perceived as lack of insight due to mental illness. Therefore, it appeared that their engagement in psychology was a means of influencing how they were perceived by those with the decision-making power to direct leave or discharge from hospital:

. . . when the doctor sees that you haven’t been to psychology, it means I can’t be arsed to improve. So that’s why it will look bad of me . . . it will make me look like I can’t be bothered to do anything. It’s like I want to just stay here and not get better . . . they’ll tell MoJ I’m not complying with help here, then it will look bad on me and it will stop me going home. . . . (Ayden, P9-10/L169-179)

. . . the team would think that I haven’t got insight into my illness. And if I haven’t got insight into my illness there is more chance of relapsing. And if there is more chance of me relapsing then there’s probably less chance of me being discharged. So, I kinda felt that I had something to prove to them as well . . . they are the people that make the decisions and write the reports and stuff. (Tyrone, P17/L321-329)

One participant discussed how a need to ‘show’ or ‘prove’ to stakeholders that they were psychologically well enough for leave or discharge was confirmed by their solicitor who held expert knowledge of how the FMH system operated, and whose advice was regarded factual. This reinforced the notion that their engagement in psychological assessment and treatment was a key determining factor for acquiring leave or discharge. Consequently, an ability to make an autonomous decision regarding participation in psychological work was limited if they wished to progress through the system, resulting in a sense of powerlessness and perceived coercion to engage:

. . . the solicitor says they like you to do groups. It’s what I have to do for shadow leave, then unescorted leave, then release. So, if you don’t do the groups, you ain’t going to get progressed through it. (Max, P16-17/L305-311)

In particular, participants made reference to the power of the psychiatrist within the system, leaving them with no alternative but to submit to their requests:

. . . because we are living under the doctor’s orders, you have to obey by their rules. (Jay, P12/L213-216)

The psychiatrists’ judgements were seen to carry significant weight by those in power to direct leave or discharge, such as the MHRT or MoJ. Participants felt that their engagement with psychological assessment and treatment would be perceived favourably by the psychiatrist, and, in turn, this could impact on the information fed back to those with the power to direct leave or discharge:

. . . the psychiatrist . . . he’s the main guy at the moment. Even going to Tribunals, nine times out of ten they go with what the doctor says, unless you’ve got a decent enough case. (Collin, P8/L114-148)

For several participants the psychologist was also seen as having power within and being part of the coercive system, including their influence on the psychiatrist:

Psychologists and psychiatrists both have clout but normallywhat the psychiatrist says is usually advised by the psychologist as well. But mainly the psychiatrist has the clout to get someone out here fast. . . . (Carlton, P28/515-523)

On the whole, participant accounts suggested that they were subject to paternalistic approaches to care and treatment, and that different ‘types of coercive power’ or practices were employed to ensure their engagement with psychological assessment and treatment (i.e. using one’s position of authority, leverage and verbal threats, as well as persuasion or the withdrawal of emotional support following non-compliance). Participants discussed being ‘told’ of a requirement to engage with psychology by their treating psychiatrist, with little consideration given to their preferences or capacity to exercise choice over their participation, as such an inability to have their voices heard evoked feelings of distress:

[I felt] frustrated and angry . . . because I didn’t want to do something that I have been told to do. (Wayne, P12/L 205-208)

A sense of perceived coercion was made explicit at times; specifically the prospect of leave or discharge was used as leverage to promote initial engagement in psychology rather than the possibility of any therapeutic gains:

. . . I couldn’t wait to get my psychology over and done with, because my doctor told me that unless I complete my psychology then I’m not going to be discharged. (Berty, P8/L145-149)

. . . on one occasion, I errr, I didn’t go on my psychology and it was looked upon in a negative way by my doctors and in my ward round. And they said that I shouldn’t do that again [if I did] . . . they said that I will be getting my leave reduced or they’d take it off me…(Berty, P11-12/L212-221)

The latter excerpt demonstrates that not only was leave entitlement used as leverage to promote engagement with psychology, for this participant, disengagement was also accompanied by threats to the loss of privileges. This reinforced their understanding of engagement as a mere opportunity to acquire leave.

Other participants highlighted the use of implicit coercive practices to promote engagement with psychological assessment and treatment. These ‘subtle’ pressures were more commonly employed by other members of the multi-disciplinary team (MDT):

So, there is a little bit of pressure from the MDT to engage in things like psychology…Yeah in a subtle way because they wouldn’t necessary say to you because you don’t do psychology you won’t get out of this place. But you know, I think they will sugar-coat it in such a way that you know that if you do psychology you would be able to be discharged eventually. (Tyrone, P19-20/L374-388)

This account highlights that even in the absence of leverage, implicit coercive practices incited similar levels of perceived coercion to engage, and this was a prevalent theme among participants’ narratives. Typically, implicit forms of coercion included gentle persuasion whereby the potential benefits of engaging were emphasised by specific disciplines:

…Staff say you have to do the course. Well not have to, but just in theory…The nurses, they say it will help you, which is wrong. I don’t think we should do it. (Max, P2/L30-34)

One participant explained how non-engagement led to interpersonal conflict, specifically nursing staff’s disapproval and withdrawal of support. Subsequently, this led to feelings of distress and perceived coercion to attended sessions with the psychologist as his only means of accessing the support he required:

…if I don’t go and then I feel agitated they’re like ‘I told you, you need to go to psychology to speak about things’…It makes me feel that I have to go…I want to talk to them, not a psychologist…It gets me frustrated…It’s like staff don’t want to help me…If they wanted to help they wouldn’t chuck me in front of psychologists, know what I mean? (Ayden, P10-11/L182-198)

A few participants pointed out that psychologists were not exempt from applying subtle pressures, reportedly persuading participants by highlighting the benefits of their engagement:

They [psychologist] said that I don’t have to do it if I don’t want, but it’s better for your care to go. (Howard, P5/L88-84)

Experiencing and r esponding to perceived c oercion

This theme captures participants’ subjective experiences and responses to perceived coercion to engage in psychological assessment and treatment. It consists of three subthemes: ‘wanting to resist’, ‘weighing up options’ and ‘playing the system’.

All forms of coercive practice whether explicit or implicit were associated with a sense of perceived coercion for participants. Consequently, an initial desire to resist engagement was expressed. Participants viewed psychological assessment and treatment as something they did not want or need, and which would be of no benefit. This initial feeling of ‘wanting to resist’ coincided with negative emotions such as depression, annoyance, frustration and feeling pressurised, indicating an element of distress associated with perceived coercion to engage:

It makes me feel depressed. I don’t need it and I don’t want to do something that I don’t want to do. (Howard, P5/L89-90)

Some participants reported a sense of helplessness and an inability to voice concerns due to the fear of being reprimanded;

[I felt]…frustrated, I was just feeling pressurised into things which I thought I didn’t need.…Erm, I didn’t speak to anyone about feeling pressurised or anything like that. I just kept it to myself…because I thought it might make it worse for me…by saying I don’t wanna do this or that, it might come against me.…(Wayne, P10-11/L180-185)

Others discussed how the length of time it took to commence, complete or repeat psychological assessment and treatment allegedly completed elsewhere amplified feelings of wanting to resist. It appeared this process of waiting (often due to resource issues) was considered unjust as it prolonged hospital admissions and prolonged participants’ experience of coercion:

Yeah, it was also how long it is for these programmes to start. It was quite awkward for me. I wanted to be out of here quicker, when they’re taking things so slowly. I was here probably about six months before I started, before I was given any good psychology work. (Wayne, P4/L58-60)

I’ve done everything in prison. I come here after my prison sentence had finished and I have to do it all again which is wrong…for me to get released. Just to say I’ve changed. I ain’t going to change how I am because I have done everything. It’s not going to make no difference. (Max, P11/196-205)

Participants recognised their inability to exercise autonomous decisions when ‘weighing up options’ about resisting or accepting psychology due to a fear that resisting would be associated with adverse consequences such as attaining leave and the likelihood of discharge:

I just won’t get shadow leave if I refuse, I should imagine. But I know if I don’t do the course I ain’t going to get it. I have to do it. (Max, P16/L299-301)

…It’s like blackmail in a way. It feels like you got to do something you don’t want to do to progress, to get out. Because if you don’t do it, you’re here even longer. (Robert, P7/L117-212)

Other participants anticipated that resistance would prolong the coercive experience of being in the FMH system, as the pressure to engage would continue until they eventually complied with what the system deemed was in their best interest:

I would have to do the course at a later date. Yeah, they would just make me do it further down the line…what I have seen from the people I’m around, the doctors, psychiatrists, feel that all of us need these programmes. (Carlton, P16/L291-295)

Some participants drew attention to engagement in psychological assessment and treatment being presented as choice in the context of being informed of their right to accept, decline or withdraw. Yet for these participants non-compliance was not a feasible option. Rather, their right to withdraw or decline was considered an illusion, because exercising this right was associated with adverse consequences:

I have the right to stop, but if I stop doing it it’s going to look bad on me.…If I say to the doctor that I don’t want to go to psychology anymore, he’s going to say, it’s going to stop you from being discharged and going home.…I have a choice, but I don’t have a choice, because I want to go home. (Ayden, P6-7/L113/119)

During the process of weighing up their options, it appeared participants were limited to two options, to resist or to accept psychology, both of which were equally undesirable. Decisions to engage were solely about acquiring rewards such as leave or discharge from hospital; in turn, participants appeared to give in to the system.

Several participants discussed acquiring knowledge of the FMH system through anecdotal accounts of their peers. Not only did negative experiences of peers who did not comply with psychology reinforce the coercive nature of the system, peer accounts also appeared to have a significant influence over the decision to engage and begin ‘playing the system’:

There’s people that’s been here years because they haven’t really wanted to do the courses. Riley has been here 5 years because he hasn’t done courses, he’s still here. So, you are pressured into doing it and having to stick to it. (Max, P12/L223-227)

People keep saying if you don’t do psychology it will stop you from getting out.…That’s the reason why I do it.…I’m listening to them I don’t know if it’s true or not. (Ayden, P8/L133-142)

In response to their perceived coercion, the knowledge acquired was used to regain control. Through actively avoiding the mistakes of their peers, these participants felt able to navigate their own journey through the system in turn, accelerating their own progress:

…Some patients have been here three years…they’ve only just finished the course that I was doing earlier on than them.…By doing it when it was first prescribed, the psychology…I won’t have to waste time afterwards. Whereas, they fell into that trap.…So that is the mistake that I didn’t make. (Carlton, P7-8/L132-148)

This process of regaining control led many participants to ‘play the system’. It was felt any level of engagement with psychology, even superficial, was helpful, and little motivation to make positive changes was evident across their accounts:

You have to attend groups, take part in activities with OT and do all that stuff, you know.…If you play the hospital game, the system, you get through it a lot quicker…and doing psychology is a part of it.…(Collin, P17-18/L311-319)

…I know I’ve got to do it, to tick the boxes to get out. (Robert, P11/L192)

Psychology…it’s a means to an end.…Because it helps me get discharged. (Howard, P13/L231-234)

Psychology ishelpful, but…

The final theme centres on participants’ experiences of completing psychological assessment and treatment. It reports the impact of perceived coercion on engagement with psychological work and considers the extent to which therapeutic alliance can be established. This overarching theme comprises two themes ‘psychology is helpful’ and ‘dual role of the psychologist’.

Although participants described feeling coerced, most reportedly provided informed consent prior to commencing any psychological work, which entailed a combination of verbal and written information about the psychological intervention, as well as potential gains. A small number of participants had no recollection of the formal consenting procedure. However, given that participants generally felt restricted in the ability to make an autonomous treatment decision, which led to feelings of perceived coercion, this challenges the validity of any consent obtained. Nonetheless, with more exposure, it appeared that participants’ attitudes towards psychology changed, many noting that to some extent ‘psychology is helpful’:

…I thought, no I don’t need this, I don’t need that. But while doing these psychology groups, it helped me to think differently about psychology…they’re only trying to help. Yeah, to help you see things in a different way. (Wayne, P7/L121-126)

Therefore, despite initially being inclined to resist, many participants began to adopt a more positive outlook towards psychology over time, acknowledging a need to work towards making changes, expressing increased self-determination and reporting that they valued their psychology sessions. Of these participants some learnt to reflect on the circumstances that had led to their hospital admission and, in turn, developed increased self-understanding and more adaptive coping mechanisms:

I didn’t want to do the one-to-one, but I done it though.…It’s the way she would dig into everything about your life, to find out why you do drugs, crime, and you find out things about yourself. It gives you an eye opener as to why you use drugs and stuff, and commit crime. (Max, P7-8/L125-134)

I know I’ve got issues which need to be addressed. Because I’ve always got out, got into the old routine again and then ended back in prison or hospital…I know it’s making me think better and deal with decisions in my life, which I need to do. (Robert, P5/L57-63)

Participants tended to place greater value on individual psychology sessions than groups, noting they felt safer. Several spoke of feeling uncomfortable and anxious in group therapy settings, wherein they felt unable to express themselves openly due to a fear of judgement or shame:

I think they’re are going to laugh at me…if I’m in a group I don’t know what to say because I get nervous…I think if I say anything they’re going to judge me.…(Ayden, P5/L84-93)

It can be quite hard sometimes in the offending group to open up because of the nature of my offences.…(Wayne, P19/L340-342)

Participants’ accounts mainly suggested that the psychologist was able to establish a therapeutic alliance, which is likely to have been achieved through an interplay of factors. Firstly, although participants felt coerced into psychology, they were still able to acknowledge the psychologists ‘helping role’, possibly due to the psychologists’ personal attributes and clinical skills. For instance, most participants described the psychologist as someone who was caring, was empathetic and had a genuine interest in supporting them to make changes:

They try and help us, not come in against us. And knowing that I have people to talk to, it helps. (Wayne, P4/L67-68)

They’re helpful, caring, they just want to see people get out of their old ways and move on with their lives. That’s why they want me to get out of my ways. (Robert, P14/L236-241)

Secondly, the psychologist created a safe space in therapy to allow participants to express themselves and discuss matters free from judgement. Some participants referred to the psychologists as the only person they could confide in:

Yeah, because she listens to me. Whatever’s up I can talk to her about it and she’ll be there to listen,…she’s understanding and she’s there to talk to me. (Max, P19/349-350)

I mean I like speaking to psychologists because they’re the only people I can really talk to, open up and you know.…(Collin, P1/L13-14)

Thirdly, although participants were subject to the coercive nature of the FMH system, some participants reported that they were given the opportunity to exercise control and autonomy in psychology sessions, working collaboratively to address their issues:

I am able to have a kind of platform to express myself. (Tyrone, P13/L247)

I was able to decide where I wanted the sessions; I was able to decide what time I wanted the session.…I had control over the topic matters I wanted to discuss. (Berty, P24/L441-448)

For these participants it appeared that an ability to exercise autonomy and control during psychological assessment and treatment facilitated the development of self-determination, such that they were now interested in embarking on change and shifted from wanting to resist against the system to engaging and working towards self-improvement:

I’ve learnt a lot about my offending behaviour and the harm it does to others, it makes me not want to go back to drugs because it’s harming others, which I didn’t ever think about before. So yeah, it’s helped, I have belief in myself to change. She [psychologist] says I will get there, remains positive all the time, saying we will get there, just keep on with it and we will get there. It’s good because they motivate you as well. (Max, P9-10/L168-174)

At the same time, several participants were aware of the ‘dual role of the psychologist’. Although psychologists were viewed as ‘helpers’, they remained part of the hierarchical power structure and an extension of the coercive system, highlighting a power imbalance in the therapeutic alliance. Psychologists working in FMH services are often responsible for risk assessment and reporting risk-related information to stakeholders in power to direct or prohibit access to leave or discharge. Consequently, these participants were ambivalent about the psychologists’ dual role as both a ‘helper’ and a ‘controller’:

I felt like they can be a mediator between you and other staff and that can go either way. It could be a good thing or a bad thing because they can say, I know that these are his strengths or his weaknesses so maybe his care should be more focused towards this direction. Whereas they could be judgmental about you, saying these are his weaknesses and I don’t think he should be able to do this, or be allowed that…they can mediate and have an impact in ward rounds. (Tyrone, P26/L504-510)

The negative impact of psychologists undertaking risk assessments was a shared concern among these participants and impacted on the quality of the therapeutic alliance. Specifically, some participants reported being unable to make full disclosures in the psychology session particularly when related to risk:

Yeah, sometimes, I haven’t wanted to talk about things that I would really like to discuss, like escaping or absconding from the unit, carrying sharp weapons, carrying a mobile phone on the ward and stuff like that. I don’t want to discuss about things like that, about how I really feel…I think they would reduce my leave because they would have known I wanted to escape. (Berty, P23/L425-437)

Other participants, however, reported being truthful with the psychologist. This seemed to have little to do with therapeutic alliance, rather it reflected their fear of the system and facing further sanctions if caught:

It makes me always give truthful answers.…Because I don’t want to slip up. (Howard, P13/L221-224)

Nevertheless, whether these participants chose to hold back from making disclosures or felt pressured into making disclosures out of fear of being found out, the psychologist’s dual role as ‘therapist’ and ‘risk assessor’ appeared to invite distrust into the therapeutic alliance, suggesting some level of superficial engagement was inevitable:

I don’t trust them…because they discriminate against me if I do anything wrong. [They]…tell the doctor that psychology is not going well and then he’ll stop my leaves and that. (Howard, p12/L201-209)

I can’t put my full confidence in the psychologist because I feel like she may not have my best interests at heart…I might feel a little bit of resentment. At the same time, I feel like I just have to get on with the psychologist to be able to progress.…(Tyrone, P5-6/L95-102)

Discussion

This study explored forensic inpatient experiences of perceived coercion to engage with psychological assessment and treatment, in a low secure FMH service. Three over-arching themes emerged from a thematic analysis of the data: ‘awareness of coercive power’, ‘experiencing and responding to perceived coercion’, and ‘psychology is helpful, but…’.

The theme of ‘awareness of coercive power’ supports the concept of coercion as a relational and contextual phenomenon (Newton-Howes, 2010; Norvoll & Pedersen, 2016). Participants’ narratives highlighted an awareness of being passive subjects in a coercive institutional environment, composed of hierarchies of power. Here, compliance with psychology was a key agenda of the system. The notion of FMH services being structured by hierarchies of power has been previously noted (Mason & Adler, 2012; Wilkinson, 2008), with forensic inpatients making reference to the UK Home Office (Wilkinson, 2008) and professionals having power over them (Burgess, 2011; Jacob & Holmes, 2011; Riordan & Humphreys, 2007). In this study this corresponds to participants’ descriptions of the United Kingdom MOJ and MHRT holding the most power over them, followed more explicitly by psychiatrists and more implicitly psychologists and other members of the team (Barnao, Ward, & Casey, 2015; Wilkinson, 2008). These key stakeholders were seen to possess the power to influence participants’ progression through the system (e.g. granting of leave or discharge) and to ensure their engagement with psychology. A perceived power imbalance has been consistently noted in general and secure psychiatric settings (Baker, 2003; Burgess, 2011; Hughes, Hayward, & Finlay, 2009; Wilkinson, 2008), which has been argued to coerce patients into treatment (Hannigan & Cutcliffe, 2002; Richardson, 2008).

In accordance with existing literature, it would seem the use of threats (Lidz et al., 1995; McKenna et al., 2003; Sørgaard, 2007) and leverage (Van Dorn et al., 2006) were in line with participants’ reports of perceived coercion. Implicit forms of coercion such as persuasion have been argued to minimise perceived coercion by involving participants in treatment decisions (Lidz et al.,1995), although this finding was not supported by the present study, wherein participants were equally aware of implicit coercive practices. Supporting previous research, this study found that participants engaged in psychology solely for recognition and associated incentives, such as early release (Mason & Adler, 2012; Rigg, 2002; Schafer & Peternelj-Taylor, 2003). Participants’ sense of powerlessness in this process has also been noted to be common in previous research on forensic inpatients (Livingston, Rossiter, & Verdun-Jones, 2011; Mezey et al., 2010; Taylor, 2016).

In this study, as in prior research, participants’ reports of the consequences of perceived coercion to engage in psychology included feelings of resentment (Shearer & Ogan, 2002), low internal motivation (Gudjonsson, Young, & Yates, 2007; Hepburn & Harvey, 2007; Klag, O’Callaghan, & Creed, 2004; Parhar et al., 2008) and psychological distress (Cooke, Baldwin, Howison, & Towl, 1990). Psychology was also viewed as unhelpful initially, and a desire to resist was expressed (Skelly, 1994; Wilkinson, 2008). Nonetheless, psychology engagement appeared inevitable, not necessarily because of a desire for recovery but because of the forensic inpatients’ continuous search for solutions to escape the coercive conditions of FMH services (Hörberg & Dahlberg, 2015).

Interestingly, a participant’s decision to engage in psychology was also influenced by internal coercion (i.e. their own beliefs and knowledge about how the system would respond to non-compliance). Specifically, a fear of potential punishment, harassment or being viewed as lacking insight (Ellis, 2013; Hörberg & Dahlberg, 2015; Norvoll & Pedersen, 2016) featured in participants’ accounts. Notably, compliance may not have been about the complete loss of power, as perceived coercion can elicit expressions of counter-power (Brehm & Brehm, 2013). Thus, participants’ eventual compliance with psychology might be understood as an attempt to regain control, in that their narratives implied they had learned from the mistakes of their peers and used this knowledge to ‘play the system’. Consequently, this led to a superficial level of engagement with psychology, in order to accelerate their progression through the system by displaying behaviour that pleases those in authority: an adaptive strategy of counter-power used by forensic inpatients (Burgess, 2011; Kennedy, 2002; Wilkinson, 2008). As Burgess (2011) asserts, playing the game is about the deliberate abandonment of self-agency and assuming a co-operating role in order to survive the FMH system, avoid untoward consequences and achieve desired outcomes.

Notably, however, with increased exposure to psychology, perceived coercion and feelings of wanting to resist declined. Consistent with previous studies, over time, participants exhibited increased self-determination and motivation to work towards change (Hogan et al., 2015; Lamberti et al., 2014; Rigg, 2002; Schafer & Peternelj-Taylor, 2003) and reported therapeutic gains, such as acknowledging a need for treatment, improved self-reflection and adaptive coping mechanisms (Ellis, 2013; Hogan et al., 2015; Mason & Adler, 2012). In accordance with self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2002), these findings suggest that participants’ engagement, which was once externally controlled, became intrinsically motivated with increased exposure to psychological work, through a process of socialisation, and, thus, they were able to benefit from sessions. It is of note that participants reported more gain, increased containment and less shame from individual psychology sessions, where resources allowed (cf. Day et al., 2004; Ellis, 2013; Mason & Adler, 2012).

Importantly, this study provides further evidence that a therapeutic alliance can be established under coercive conditions (Kennealy et al., 2012; Manchak, Skeem, & Rook, 2014; Skeem, Louden, Polaschek, & Camp, 2007), by setting up a collaborative and person-centred working partnership (Bordin, 1994). This approach appears consistent with the principles of procedural justice, which is present when individuals are fully informed about proposed treatments, have their views acknowledged, participate in decision-making processes and are treated with genuine concern and respect (Lind, Kanfer, & Earley, 1990). The application of procedural justice in clinical practice has been shown to minimise coercion, improve therapeutic alliance and increase receptivity of coerced treatment (Cascardi & Poythress, 1997; Donnelly, Lynch, Mohan, & Kennedy, 2011; McKenna et al., 2003; Olofsson & Norberg, 2001). Together, both the quality of therapeutic relationships and application of procedural justice may have a positive effect on perceptions of coerced treatment, even in the face of initial resistance (Deutsch, 2002; Maiese, 2004).

Finally, whilst some degree of therapeutic alliance was established, this study also noted participants’ ambivalence and awareness of the psychologist’s dual role, potentially limiting their disclosure. Previous research has noted that the tensions that arise from dual commitments impact negatively on a clinician’s ability to care (Gildberg, Bradley, Fristed, & Hounsgaard, 2012; Hörberg & Dahlberg, 2015; Jacob & Foth, 2013), and some authors have speculated that the psychologist’s additional role of risk assessment, and a responsibility to share risk information with authorities in power to restrict freedoms, compromises the quality of the therapeutic alliance (Crewe, 2009; Ellis, 2013; Gudjonsson et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2002; Ross et al., 2008).

Clinical implications

The findings pose significant implications for the provision of psychology assessment and treatment in FMH services and confirm that achieving ethical standards of practice and avoiding any involvement in coercive practices can be challenging for psychologists working in FMH settings (Haag, 2006). Where psychology work is leveraged with leave or discharge, psychologists may find they are indirectly involved in coercive practices, which incite perceived coercion and, as suggested by this study, result in superficial levels of engagement, which may impact on treatment efficacy. If forensic inpatients do not recognise a need for treatment, change is unlikely to be internalised, and apparent gains may not persist once they are no longer under surveillance (Lamberti et al., 2014; Wilkinson, 2008).

Psychologists play an important role in advocating against coercive practices by discouraging professionals from leveraging psychological interventions with access to leave or discharge. Delivering training about the role of coercion and its impact on inpatients’ wellbeing, treatment adherence and outcomes would also be useful. Psychologists should endeavour to minimise forensic inpatients’ perceived coercion to engage with psychological interventions, by involving them in fair treatment decision-making, which is central to promoting self-determination and autonomy (Cascardi & Poythress, 1997; McKenna et al., 2003).

Gaining explicit informed consent is of the utmost importance to ethical practice and assists in mitigating against perceived coercion in forensic settings (Adshead & Brown, 2003) – specifically, allowing participants to have sufficient explanation about the purpose of an assessment or intervention, providing sufficient time to reach an informed decision concerning participation and ensuring that the right to decline, accept or withdraw is fully understood. Another challenge psychologists face in FMH services is pressure from other stakeholders to complete psychological work within a specified time period. This fails to appreciate a service user’s ability to benefit from psychological work at a given time (Miles, 2016). Instead, psychologists should also be given sufficient time to increase an individual’s readiness (Roberts, Contois, Willis, Worthington, & Knight, 2007), to increase the likelihood of voluntary engagement with future interventions. It may also reduce some of the inherent power imbalance present in the therapeutic relationship, through a more informed choice (Miles, 2016).

A key finding of the study suggests that therapeutic alliance can be established despite the coercive conditions under which forensic inpatients may enter psychology. This lends support to the argument that provision of psychological services in FMH services benefits not only inpatients but the wider public in terms of risk reduction (Long, Fulton, Fitzgerald, & Hollin, 2010; McCarthy & Duggan, 2010). Psychologists should be mindful, however, that their duality of role may compromise disclosures concerning risk, which may impact on therapeutic outcomes, and therefore it may be more helpful for separate psychologists to administer risk assessment and deliver treatment.

Lastly, findings highlight the coercive structure inherent in the FMH system, suggesting that there is a need for organisational changes that are more person centred or psychologically informed (e.g. Rose, Evans, Laker, & Wykes, 2015). As Bentall (2013) argues, ‘in the long term, the solution of the problem of coercion…is to design services that patients find helpful and actually want to use’. (para. 8)

Limitations

This is one study (n = 10), in one low secure service in the United Kingdom, consisting of an all-male sample. Therefore, the findings may not be reflective of inpatients detained in other FMH services, or of females. Anecdotally, however, when these findings have been discussed with other FMH services, it has been noted that the themes have resonance. Nevertheless, higher levels of security may have higher levels of perceived coercion and/or differing issues due to greater restrictions placed on freedoms. There is also a possible sample bias in that participants opted to take part in this study, suggesting that they are more compliant with the system and, thus, less likely to possess a strong sense of perceived coercion than those that did not participate (DiCondina, 2016; Gilburt, Rose, & Slade, 2008). There are also limitations with the use of qualitative methodology. The emergent themes are based on the presumption that participants’ narratives were a true reflection of their experiences although retrospective accounts of coercion may not be accurate. Over time, as participants improve psychologically and benefit from treatment, they may forget initial feelings of perceived coercion (Fiorillo et al., 2012; Katsakou & Priebe, 2006). It should also be noted that whilst participants largely reflected on their experiences of psychological assessment and treatment as positive following a period of engagement, they rarely discussed this experience on their own volition. This narrative is likely to have been elicited through the design of the interview schedule, which sought to draw out both positive and negative experiences.

Moreover, an interest in the research topic, prior clinical experiences and knowledge may have biased the researcher’s analysis and interpretation of the data. Lastly, power differentials between researcher and participant and the narratives elicited as a result are acknowledged (Hoffmann, 2007). Although the researcher was external to the unit and was not involved in participants’ care and treatment, they were likely to be viewed by participants as part of the system, resulting in censored responses or socially desirable responding.

Conclusions and f uture d irections

This is the first study examining coercion into psychological assessment and treatment within low secure FMH services and highlights that forensic inpatients with severe mental illness can engage in complex discussions about their experiences of coercion (e.g. Norvoll & Pedersen, 2016), providing valuable insights for enhancing clinical practice. Given the detrimental impact, experiences of coercion remain an important area to research and are receiving increased attention. To date, perceived coercion has mainly been explored in relation to psychiatric interventions. This study brings the field of investigation further with a specific focus on experiences of coercion to engage in psychological assessment and treatment and highlights that, even with the best will and therapeutic skills, psychologists working in forensic settings may be complicit in coercion.

Future research should examine different levels of security, those who refuse to engage in psychology and a female sample to determine whether the themes identified are universal. Such themes could then be used to develop a questionnaire assessing perceived coercion to engage in psychology, as well as exploring the longer term impact of coercion on treatment outcome and the reduction of risk. Finally, research that leads to a better understanding of how psychologists could adapt their practice to mitigate against such possibly detrimental experiences is warranted.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Cassandra Simms-Sawyers has declared no conflicts of interest

Helen Miles has declared no conflicts of interest

Joel Harvey has declared no conflicts of interest

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study

References

- Adshead, G., & Brown, C. (2003). Ethical issues in forensic mental health research. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, P.S. (1985). Empirical assessment of innovation in the law of civil commitment: A critique. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 13(6), 304–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.1985.tb00954.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E. (2003). Service-user views on a low secure psychiatric ward. Clinical Psychology, 25, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R., & Moore, C. (2006). Working in forensic mental health settings. In: What is clinical psychology? (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnao, M., Ward, T., & Casey, S. (2015). Looking beyond the illness: Forensic service users’ perceptions of rehabilitation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(6), 1025–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentall, R. (2013, 1 February). Too much coercion in mental health services. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/feb/01/mental-health-services-coercion.

- Blackburn, R. (2004). “What works” with mentally disordered offenders. Psychology, Crime & Law, 10(3), 297–308. doi: 10.1080/10683160410001662780 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bordin, E. (1994). Theory and research on the therapeutic working alliance: New directions. In Horvath A. & Greenberg L. (Eds.), The working alliance: Theory, research and practice (pp. 13–37). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm, S.S., & Brehm, J.W. (2013). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. (2015). Social research methods. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, S.L. (2011). Exploring the experience of community adjustment following discharge from a low secure forensic unit (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Leeds, Leeds, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J., & Davidson, G. (2009). Coercion in the community: A situated approach to the examination of ethical challenges for mental health social workers. Ethics and Social Welfare, 3(3), 249–263. doi: 10.1080/17496530903209469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canvin, K., Rugkåsa, J., Sinclair, J., & Burns, T. (2014). Patient, psychiatrist and family carer experiences of community treatment orders: Qualitative study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(12), 1873–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi, M., & Poythress, N.G. (1997). Correlates of perceived coercion during psychiatric hospital admission. International Journal of Law & Psychiatry, 20(4), 445–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, R., Owen, G.S., & Singh, S. (2007). International experiences of using community treatment orders. London, UK: Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, D.J., Baldwin, P.J., Howison, J., & Towl, G.J. (1990). Psychology in prisons. London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Corring, D., O’Reilly, R., & Sommerdyk, C. (2017). A systematic review of the views and experiences of subjects of community treatment orders. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 52, 74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W., & Clark, V.L.P. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Crewe, B. (2009). The prisoner society: Power, adaptation, and social life in an English prison. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Day, A., Tucker, K., & Howells, K. (2004). Coercing offenders into treatment. Psychology, Crime and Law, 10(3), 259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K., & Lincoln, Y. (2000). Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2008). Code of practice: Mental Health Act 1983. London, UK: Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, M. (2002). Social psychology’s contributions to the study of conflict resolution. Negotiation Journal, 18(4), 307–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1571-9979.2002.tb00263.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, R.J. (1996). Coercion and tenacious treatment in the community. In Dennis D.L. & Monathan J. (Eds.), Coercion and aggressive community treatment: A new frontier in mental health (pp. 51–72). New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- DiCondina, J. (2016). The effects of perceived coercion on group attendance, participation in groups, and leaving against medical advice in an inpatient psychiatric facility (Unpublished student dissertation). Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Philadelphia, PA. Accessed via: DigitalCommons@PCOM [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, V., Lynch, A., Mohan, D., & Kennedy, H.G. (2011). Working alliance, interpersonal trust and perceived coercion in mental health review hearings. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 5(1), 29. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edworthy, R., Sampson, S., & Völlm, B. (2016). Inpatient forensic-psychiatric care: Legal framework and service provision in three European countries. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 47, 18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, K. (2013). An exploration of the relationships between inpatients and clinical psychologists in forensic mental health services (Doctorate in Clinical Psychology Thesis). Salomons Psychology Centre, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, K.I., & Westrin, C. (1995). Coercive measures in psychiatric care. Reports and reactions of patients and other people involved. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 92(3), 225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09573.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo, A., Giacco, D., De Rosa, C., Kallert, T., Katsakou, C., Onchev, G., & Luciano, M. (2012). Patient characteristics and symptoms associated with perceived coercion during hospital treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 125(6), 460–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01809.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller, J.L. (1991). Rx: A tincture of coercion in outpatient treatment? Psychiatric Services, 42(10), 1068–1070. doi: 10.1176/ps.42.10.1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilburt, H., Rose, D., & Slade, M. (2008). The importance of relationships in mental health care: A qualitative study of service users’ experiences of psychiatric hospital admission in the UK. BMC Health Services Research, 8(1), 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gildberg, F.A., Bradley, S.K., Fristed, P., & Hounsgaard, L. (2012). Reconstructing normality: Characteristics of staff interactions with forensic mental health inpatients. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 21(2), 103–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00786.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, T., Batson, A., & Gudjonsson, G. (2011). The development and initial validation of a service-user led measure for recovery of mentally disordered offenders. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 22(2), 252–265. [Google Scholar]

- Gudjonsson, G.H., Young, S., & Yates, M. (2007). Motivating mentally disordered offenders to change: Instruments for measuring patients’ perception and motivation. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 18(1), 74–89. doi: 10.1080/14789940601063261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haag, A.M. (2006). Ethical dilemmas faced by correctional psychologists in Canada. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 33(1), 93–109. doi: 10.1177/0093854805282319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan, B., & Cutcliffe, J. (2002). Challenging contemporary mental health policy: Time to assuage the coercion? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37(5), 477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hem, M.H., Pedersen, R., Norvoll, R., & Molewijk, B. (2015). Evaluating clinical ethics support in mental healthcare: A systematic literature review. Nursing Ethics, 22(4), 452–466. doi: 10.1177/0969733014539783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn, J.R., & Harvey, A.N. (2007). The effect of the threat of legal sanction on program retention and completion: Is that why they stay in drug court? Crime & Delinquency, 53(2), 255–280. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, E.A. (2007). Open-ended interviews, power, and emotional labor. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 36(3), 318–346. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, N.L., Barton-Bellessa, S.M., & Lambert, E.G. (2015). Forced to change: Staff and inmate perceptions of involuntary treatment and its effects. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice, 11(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hörberg, U., & Dahlberg, K. (2015). Caring potentials in the shadows of power, correction, and discipline—Forensic psychiatric care in the light of the work of Michel Foucault. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 10(1), 28703. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v10.28703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, R., Hayward, M., & Finlay, W. (2009). Patients’ perceptions of the impact of involuntary inpatient care on self, relationships and recovery. Journal of Mental Health, 18(2), 152–160. doi: 10.1080/09638230802053326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hui, A., Middleton, H., & Völlm, B. (2013). Coercive measures in forensic settings: Findings from the literature. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 12(1), 53–67. doi: 10.1080/14999013.2012.740649 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, J.D., & Foth, T. (2013). Expanding our understanding of sovereign power: On the creation of zones of exception in forensic psychiatry. Nursing Philosophy, 14(3), 178–185. doi: 10.1111/nup.12017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, J.D., & Holmes, D. (2011). Working under threat: Fear and nurse–patient interactions in a forensic psychiatric setting. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 7(2), 68–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-3938.2011.01101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallert, T.W. (2008). Coercion in psychiatry. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 21(5), 485–489. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328305e49f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsakou, C., & Priebe, S. (2006). Outcomes of involuntary hospital admission–a review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 114(4), 232–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00823.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennealy, P.J., Skeem, J.L., Manchak, S.M., & Eno Louden, J. (2012). Firm, fair, and caring officer-offender relationships protect against supervision failure. Law and Human Behavior, 36(6), 496. doi: 10.1037/h0093935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, H.G. (2002). Therapeutic uses of security: Mapping forensic mental health services by stratifying risk. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 8(6), 433–443. doi: 10.1192/apt.8.6.433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kisely, S.R., Campbell, L.A., & Preston, N.J. (2005). Compulsory community and involuntary outpatient treatment for people with severe mental disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004408.pub5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klag, S., O’Callaghan, F., & Creed, P. (2004). The role and importance of motivation in the treatment of substance abuse. Therapeutic Communities: International Journal for Therapeutic and Supportive Organizations, 25(4), 291–317. [Google Scholar]

- Lamberti, J.S., Russ, A., Cerulli, C., Weisman, R.L., Jacobowitz, D., & Williams, G.C. (2014). Patient experiences of autonomy and coercion while receiving legal leverage in forensic assertive community treatment. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 22(4), 222–230. doi: 10.1097/01.HRP.0000450448.48563.c1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidz, C.W., Hoge, S.K., Gardner, W., Bennett, N.S., Monahan, J., Mulvey, E.P., & Roth, L.H. (1995). Perceived coercion in mental hospital admission: Pressures and process. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(12), 1034–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240052010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S., & Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lind, E.A., Kanfer, R., & Earley, P.C. (1990). Voice, control, and procedural justice: Instrumental and noninstrumental concerns in fairness judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 952–959. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.952 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, J.D., & Rossiter, K.R. (2011). Stigma as perceived and experienced by people with mental illness who receive compulsory community treatment. Stigma Research and Action, 1(2), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, J.D., Rossiter, K.R., & Verdun-Jones, S.N. (2011). Forensic’labelling: An empirical assessment of its effects on self-stigma for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatry Research, 188(1), 115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, C.G., Fulton, B., Fitzgerald, K., & Hollin, C.R. (2010). Group substance abuse treatment for women in secure services. Mental Health and Substance Use, 3(3), 227–237. doi: 10.1080/17523281.2010.506182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur Research Network on Mental Health and Law. (2001). The MacArthur Admission Experience Survey, Short-Form. Retrieved from http://www.macarthur.virginia.edu/shortform.html

- Maiese, M. (2004). Procedural justice: Beyond intractability. Conflict Information Consortium. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado. http://www.Beyondintractability.org/bi-essay/procedural-Justice

- Manchak, S.M., Skeem, J.L., & Rook, K.S. (2014). Care, control, or both? Characterizing major dimensions of the mandated treatment relationship. Law and Human Behavior, 38(1), 47–57. doi: 10.1037/lhb0000039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, B., Matias, E., & Allen, J. (2014). Recovery in forensic services: Facing the challenge. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 20(2), 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, G.N., & Hser, Y. (2002). Characteristics of criminal justice and noncriminal justice clients receiving treatment for substance abuse. Addictive Behaviors, 27(2), 179–192. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00176-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruna, S. (2011). Why do they hate us? Making peace between prisoners and psychology. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55(5), 671–675. doi: 10.1177/0306624X11414401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, K., & Adler, J.R. (2012). Group-work therapeutic engagement in a high secure hospital: Male service user perspectives. The British Journal of Forensic Practice, 14(2), 92–103. doi: 10.1108/14636641211223657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayoral, F., & Torres, F. (2005). Use of coercive measures in psychiatry. Actas Espanolas de Psiquiatria, 33(5), 331–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, L., & Duggan, C. (2010). Engagement in a medium secure personality disorder service: A comparative study of psychological functioning and offending outcomes. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 20(2), 112–128. doi: 10.1002/cbm.758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, B.G., Simpson, A.I., & Coverdale, J.H. (2003). Patients’ perceptions of coercion on admission to forensic psychiatric hospital: A comparison study. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 26(4), 355–372. doi: 10.1016/S0160-2527(03)00046-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey, G.C., Kavuma, M., Turton, P., Demetriou, A., & Wright, C. (2010). Perceptions, experiences and meanings of recovery in forensic psychiatric patients. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 21(5), 683–696. [Google Scholar]