Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between lead (Pb) speciation determined using Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy in <10 μm particulate matter (PM10) from mining/smelting impacted Australian soils (PP, BHK5, BHK6, BHK10 and BHK11) and inhalation exposure using two simulated lung fluids [Hatch’s solution, pH 7.4 and artificial lysosomal fluid (ALF), pH 4.5]. Additionally, elemental composition of Pb rich regions in PP PM10 and the post-bioaccessibility assay residuals were assessed using a combination of Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) to provide insights into how extraction using simulated lung fluids may influence Pb speciation in vitro. Correlation between Pb speciation (weighted %) and bioaccessibility (%) was assessed using Pearson r (α = 0.1 and 0.05). Lead concentration in PM10 samples ranged from 782 mg/kg (BHK6) to 7796 mg/kg (PP). Results of EXAFS analysis revealed that PP PM10 was dominated by Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide, while the four BHK PM10 samples showed variability in the weighted % of Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide and organic matter bound Pb, Pb phosphate, anglesite and galena. When bioaccessibility was assessed using different in vitro inhalation assays, results varied between samples and between assays, Pb bioaccessibility in Hatch’s solution ranged from 24.4 to 48.4%, while in ALF, values were significantly higher (72.9–96.3%; p < 0.05). When using Hatch’s solution, bioaccessibility outcomes positively correlated to anglesite (r:0.6246, p:0.0361) and negatively correlated to Pb phosphate (r: −0.9610, p:0.0041), organic bound Pb (r: −0.7079, p: 0.0578), Pb phosphate + galena + plumbojarosite (r: −0.9350, p: 0.0099). No correlation was observed between Pb bioaccessibility (%) using Hatch’s solution and weighted % of Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide and between bioaccessibility (%) using ALF and any Pb species. SEM and EDX analysis revealed that a layer of O–Pb–Ca–P–Si–Al–Fe formed during the in vitro extraction using Hatch’s solution.

Keywords: Pb, Simulated lung fluid, ALF, Dust, PM10, EXAFS

1. Introduction

Adverse health outcomes due to the inhalation of toxic metals in dust or particulate matter is gaining global attention (Gosselin and Zagury, 2020; Talbi et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2018). Lead exposure is felt more acutely in communities near industrial activities, e.g. lead (Pb) mining/smelting (Maynard et al., 2003; Simon et al., 2007), Pb battery recycling (Arif et al., 2018), electronic waste recycling (Fujimori et al., 2018), steel manufacturing (Dusseldorp et al., 1995). The impact of Pb on childhood cognitive and neurological development is well documented and may occur at low Pb concentrations (ATSDR, 2007; Lanphear et al., 2005). Although ingestion is considered the major Pb exposure pathway for children, inhalation exposure assessment may be pertinent when Pb is emitted into the atmosphere during industrial activities or Pb contaminated dust is aerosolized due to resuspension.

Studies assessing Pb bioavailability (absorption into the systemic circulation) following instillation of Pb acetate and Pb contaminated dust suggest that Pb may readily cross the air blood barrier from the lung (Fent et al., 2008; Kastury et al., 2019b; Kastury et al., 2019c; Wallenborn et al., 2007). Unlike the ingestion pathway, Pb absorption via inhalation is complex and limited research has reported Pb bioavailability and in vitro bioaccessibility (dissolution in simulated biological solution) from mining/smelting impacted dust. Lead bioaccessibility from particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter of <10 μm (PM10) is assessed using simulated lung fluid with a pH of 7.4, e.g. Hatch’s solution (Kastury et al., 2018a; Sysalová et al., 2014), Gamble’s solution (Gosselin and Zagury, 2020; Wragg and Klinck, 2007), or simulated epithelial lung fluid (Boisa et al., 2014). Within the particles that deposit in the lung, those with a diameter ~1–2.5 μm are thought to stimulate engulfment by alveolar macrophages (d’Angelo et al., 2014) with Pb dissolution occurring inside the cell’s acidic lysosome (Patel et al., 2015). Therefore, metal bioaccessibility in particulate matter with <2.5 μm in diameter (PM2.5) is assessed with a simulated lung fluid of pH 4.5, e.g. artificial lysosomal fluid (ALF) or phagolysosomal fluid (PSF) (Kastury et al., 2018b; Witt et al., 2014). Previous studies has demonstrated that using Hatch’s solution (pH 7.4) and ALF (pH 4.5) as the simulated lung fluids, and 24 h as the duration of the assay may result in the most conservative inhalation bioaccessibility assessment in PM10 and PM2.5 respectively (Kastury et al., 2018a, 2018b).

Lead speciation is closely tied to bioavailability/bioaccessibility outcomes (Scheckel et al., 2013). X-ray based spectroscopic techniques [e.g. Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) and X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES)] are considered ideal Pb speciation methods as they do not require sample pretreatment that may influence speciation (Scheckel and Ryan, 2004; Sjöstedt et al., 2018). The majority of studies assessing Pb speciation (EXAFS or XANES) has utilized the <2 mm soil particle fraction, with smaller cohorts of studies reported speciation in the incidentally ingestible < 250 μm soil particle fraction (Kastury et al., 2019b; Fujimori et al., 2018; Juhasz et al., 2014), <80 μm house dust fraction (Rasmussen et al., 2011), PM10 (Kastury et al., 2018a, 2019c) and PM2.5 (Kastury et al., 2018a). A substantial body of information exists regarding Pb bioaccessibility/bioavailability via the ingestion pathway, for example, high oral bioaccessibility/bioavailability is linked with anglesite (PbSO4), cerrusite (PbCO3), Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide and organic matter bound Pb (Hayes et al., 2012; Meza-Figueroa et al., 2009; Rasmussen et al., 2011; Ostergren et al., 1999). However, limited research has reported Pb speciation in PM10 from mining/smelting regions and linked their role in inhalation exposure via bioaccessibility/bioavailability assays. Because different Pb species may be enriched in the <10 μm particle size fraction compared to the <250 μm soil particle size fraction (Kastury et al., 2019b), the correlation between Pb speciation in PM10 and inhalation bioaccessibility represent an important knowledge gap that is pertinent to exposure assessment.

Using mining/smelting impacted PM10, this study investigated the influence of Pb speciation on Pb bioaccessibility using two in vitro inhalation assays (Hatch’s solution and ALF). Results were used to investigate the correlation between Pb speciation and bioaccessibility outcomes, as well as how simulated lung fluid composition influences inhalation bioaccessibility.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection, processing and characterization

Lead contaminated surface soil (0–5 cm) was collected from Port Pirie, South Australia and Broken Hill, New South Wales; environments that have been impacted from mining/smelting activities. The Port Pirie sample was collected from approximately 0.75 km away from the Pb–Zn smelter (designated PP, Fig. S1a). This site was chosen because previous studies indicated that Pb concentrations in the <10 μm particle size fraction is elevated and may pose risk via inhalation (Kastury et al., 2018a). Samples from Broken Hill were collected from four locations along King Street (designated BHK5, BHK6, BHK10 and BHK 11), 0.1–1.5 km away from the Line of Lode (Fig. S1b). The rationale for choosing four sites in Broken Hill was discussed in Kastury et al. (2019a). Briefly, samples were selected to provide a broad range of Pb concentrations (490–3012 mg Pb/kg) in the <2 mm soil particle fraction as described in Kastury et al. (2019a). Lead concentrations in these soils were 3–10 times higher than the Health based Investigation Level a (HILa) of 300 mg Pb/kg, set by the National Environment Protection (Assessment of Site Contamination) Measure (NEPM, 2013). After drying at 40 °C, soils were initially hand-sieved to <53 μm, followed by further sieving using an Endecotts Octagon digital shaker to recover the inhalable dust fraction (<10 μm in diameter: PM10). Particle size distribution was investigated by suspending 5 mg of dust in 50 mL 0.1 M NaCl solution overnight (n = 3) (to disperse particles and prevent agglomeration), followed by analysis using AccuSizer 780 (NICOMP).

Pseudo-total elemental concentration in PM10 was determined by predigesting PM10 (0.1 g, n = 3) in aqua-regia (5 mL), followed by digestion using a MARS 6 microwave (CEM) (USEPA, 2007). The undissolved solid was removed by syringe filtering (0.45 μm, cellulose acetate), while elemental concentrations were determined using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) according to USEPA method 6020 A (EPA, 1998).

Lead speciation in PM10 was determined by EXAFS spectroscopy at the Advanced Photon Source of the Argonne National Laboratory (MRCAT beamlines 10-ID), USA according to (Kropf et al., 2010; Segre et al., 2000). Details of the EXAFS analysis methodology is provided in the Supporting Information (SI).

2.2. In vitro bioaccessibility assay

Lead inhalation bioaccessibility (n = 3) was assessed using two different simulated lung fluids: Hatch’s solution according to Kastury et al. (2018a) and Artificial Lysosomal Fluid (ALF) assay according to Kastury et al. (2018b). The compositions of Hatch’s solution was detailed in Berlinger et al. (2008), while the formulation of ALF can be found in Stopford et al. (2003). Lead in vitro bioaccessibility (%) was calculated according to Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where:

In vitro Pb = Pb concentration (mg/kg) in solution following extraction using an in vitro bioaccessibility assay.

Pseudo-total Pb = Pb concentration (mg/kg) in PM10 used in the in vitro bioaccessibility assay.

2.3. Correlation between Pb speciation and bioaccessibility

The contribution of different Pb species to inhalation bioaccessibility outcomes was explored by correlation analysis. As methodologies for the assessment of Pb bioaccessibility and speciation undertaken in this study were identical to those reported in Kastury et al., (2018a), 2018b and 2019b, data collected from all studies were combined to assess Pb bioaccessibility-speciation correlation. Normality checks were performed on Pb bioaccessibility values derived using Hatch’s solution (n = 9) and ALF (n = 9) using Shapiro-Wilk and D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test. Results indicated that data was distributed normally (p > 0.05). Therefore, correlation analysis between Pb bioaccessibility (Hatch’s solution, ALF) and Pb species weighted % [(Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide, organic matter bound Pb, Pb phosphate [pyromorphite + Pb3(PO4)2], galena (PbS), plumbojarosite [PbFe3+6(SO4)4(OH)12] and anglesite (PbSO4)] was conducted using Pearson r (α = 0.10 and 0.05). Due to low sample numbers containing galena and plumbojarosite, correlation between these two species and bioaccessibility could not be determined separately. Therefore, the weighted % of Pb phosphates, galena and plumbojarosite were combined and their correlation to Pb bioaccessibility was analyzed using Pearson r (α = 0.10 and 0.05) because these three Pb species are known for their low oral bioavailability (Scheckel et al., 2013).

2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX)

Because of its highest Pb concentration, PP PM10 was selected for further analysis to reveal changes in elemental composition in a Pb rich region of the particle when extracted in Hatch’s solution and ALF. Post-bioaccessibility residuals were washed with 50 mL MilliQ water, centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min, then dried at 37 °C overnight and replicate residuals combined. PP PM10 and post-bioaccessibility residuals were mounted on SEM stubs (6 mm, Agar Scientific) using double sided tape. After applying a carbon coating of approximately 90 nm (to increase electrical conductivity), particles were viewed under high vacuum conditions using a 20 kV electron beam (Zeiss Merlin). Lead containing dust particles were located using backscattered electrons (working distance of ~10 mm), followed by further analysis of elemental composition using secondary electrons via EDX (working distance of ~6.5 mm). Images of PM10 particles were captured using backscattered electrons to highlight regions with high Pb concentrations.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Particle size distribution in PM10

Table 1 shows that the majority of the particles (95%) were <10 μm in diameter, which ensured that samples have the potential to deposit in the respiratory system when inhaled. Although the remaining 5% in PP, BHK5, BHK10 and BHK11 were between 12.4 and 18.1 μm, the use of these samples to assess inhalation bioaccessibility was deemed appropriate as particles up to 30.1 μm in diameter were observed in NIST 1648a (urban particulate matter). The 5 PM10 samples displayed similar number weighted mean (1.08–1.87 μm) and median (0.68–0.80 μm) particle size values.

Table 1.

Particle size distribution of PM10.

| Sample name | PP | BHK5 | BHK6 | BHK10 | BHK11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SEM (μm) | 1.31 ± 0.04 | 1.56 ± 0.05 | 1.08 ± 0.01 | 1.87 ± 0.07 | 1.45 ± 0.05 | |

| Average median (μm) | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.80 | 0.75 | |

| Cumulative size distribution (μm) | 25% | <0.60 | <0.60 | <0.60 | <0.62 | <0.60 |

| 50% | <0.75 | <0.76 | <0.71 | <0.83 | <0.75 | |

| 75% | <1.15 | <1.29 | <0.98 | <1.51 | <1.15 | |

| 95% | <4.69 | <6.85 | <2.52 | <8.79 | <5.81 | |

| 99% | <12.4 | <17.7 | <9.47 | <18.1 | <15.3 |

3.2. Concentration and speciation of Pb in PM10

Table 2 shows that Pb concentration in these samples was the highest in PP (7796 ± 49.3 mg/kg), followed by BHK5 (6027 ± 163 mg/kg), BHK10 (2080 ± 28.5 mg/kg), BHK11 (1817 ± 8.5 mg/kg) and BHK6 (782 ± 117 mg/kg). Previous study using PP PM10 collected from a similar area showed a Pb concentration of 6968 mg/kg (Kastury et al., 2018a). Due to the proximity of Port Pirie sample collection sites between this study and the study of Kastury et al. (2018a), similarity in the mean Pb concentration between these two samples were expected. However, variability in Pb concentration was observed in PM10 collected from Broken Hill, which could not be attributed to the proximity from the line of lode. For example, despite being closer to the line of lode, BHK10 and BHK11 showed lower Pb concentrations in the PM10 compared to BHK5, which may be attributed to the presence of cracker dust capping applied in the vicinity of BHK11 sampling point during remediation efforts to improve dust suppression in Broken Hill (personal communication).

Table 2.

Physicochemical characterization of samples collected from Port Pirie and Broken Hill. pH and total organic carbon content was measured in the <2 mm soil particle fraction, while the pseudo-total elemental concentrations were assessed in the <10 μm dust fraction. Shading indicates data reported in Kastury et al. (2019a), included for comparison.

| PP | BHK5 | BHK6 | BHK10 | BHK11 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil pH | 7.8 ± 0.01 | 6.4 ± 0.10 | 6.9 ± 0.01 | 7.2 ± 0.10 | 7.9 ± 0.10 | |

| Soil organic carbon (%) | 0.21 ± 0.09 | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.12 | 1.87 ± 0.05 | |

| Trace element concentration in PM10 (mg/kg) | Lead (Pb) | 7796 ± 49.3 | 6027 ± 163 | 782 ± 117 | 2080 ± 28.5 | 1817 ± 8.5 |

| Arsenic (As) | 196 ± 2.01 | 54.0 ± 0.01 | 14.0 ± 2.00 | 22.5 ± 0.50 | 26.0 ± 1.00 | |

| Cadmium (Cd) | 36.0 ± 0.20 | 26.4 ± 0.90 | 2.75 ± 0.50 | 3.00 ± 0.10 | 6.40 ± 0.01 | |

| Manganese (Mn) | 1718 ± 8.08 | 3231 ± 140 | 821 ± 153 | 1352 ± 36 | 1273 ± 65.0 | |

| Zinc (Zn) | 12,868 ± 65.4 | 5613 ± 113 | 934 ± 126 | 2478 ± 41.5 | 1633 ± 25.5 | |

| Major element concentration in PM10 (mg/kg) | Aluminium (Al) | 3818 ± 503 | 25,629 ± 155 | 21,580 ± 3662 | 22,768 ± 4.00 | 23,047 ± 695 |

| Calcium (Ca) | 27,900 ± 219 | 24,024 ± 401 | 10,440 ± 1290 | 18,937 ± 457 | 97,272 ± 882 | |

| Iron (Fe) | 47,318 ± 105 | 43,976 ± 1517 | 39,189 ± 6592 | 45,667 ± 531 | 37,145 ± 453 | |

| Potassium (K) | 8779 ± 99.1 | 10791 ± 182 | 9912 ± 1511 | 11968 ± 38 | 9302 ± 309 | |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 14322 ± 5.10 | 7279 ± 150 | 7128 ± 914 | 10079 ± 251 | 6571 ± 31.0 | |

| Phosphorus (P) | 884 ± 7.30 | 1252 ± 28.5 | 5012 ± 67.5 | 960 ± 14.0 | 725 ± 2.50 |

Lead speciation results using EXAFS analysis are given in Table 3. The majority of Pb in PP PM10 was adsorbed onto clay/oxide (81%), while the remainder was distributed between organic matter bound Pb (11%) and Pb-phosphate (9%) species. Lead speciation in the four BHK PM10 samples varied markedly. The predominant Pb phase in BHK5 PM10 was Pb phosphate (45%), while organic matter bound Pb and anglesite comprised the remainder (34% and 21% respectively). Organic matter bound Pb (51%) dominated BHK6, with the other phases consisting of Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide (21%) and Pb phosphate (28%). Speciation of Pb in BHK10 consisted of two phases only: organic matter bound Pb (65%) and galena (35%), while BHK11 contained 45% Pb absorbed to clay/oxide, 39% Pb phosphate and 16% anglesite.

Table 3.

Pb speciation (weighted %) in PM10.

| PP | BHK5 | BHK6 | BHK10 | BHK11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide | 81 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 45 |

| Organic matter bound Pb | 11 | 34 | 51 | 65 | 0 |

| Pb phosphate [pyromorphite and Pb3(PO4)2] | 9 | 45 | 28 | 0 | 39 |

| Anglesite (PbSO4) | 0 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| Galena (PbS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 0 |

| R-factor | 0.00180 | 0.02295 | 0.09253 | 0.02300 | 0.03524 |

The weighted % of Pb observed in this study was compared to the parent <250 μm soil particle fraction in order to elucidate how Pb speciation may change between particle size fractions. Lead speciation in PP PM10 was similar to values reported previously for the <250 μm soil particle size fraction collected from the same vicinity (e.g. 55% Pb adsorbed to clay/oxide and 45% organic matter bound Pb reported in Juhasz et al., 2014). However, the distributions of Pb speciation in BHK PM10 differed considerably compared to values previously reported for the corresponding parent <250 μm soil particle size fraction (Kastury et al., 2019a). For example, the parent BHK5, BHK6, BHK10 and BHK11 < 250 μm soil particle size fraction contained approximately 23–26% plumbojarosite (Kastury et al., 2019a), which was absent in PM10. Additionally, between 45 and 58% of Pb in the parent BHK <250 μm size fraction was Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide, with no anglesite identified (Kastury et al., 2019a), while BHK PM10 samples in this study consisted of organic bound Pb (28–45%), anglesite (16–21%) and galena (38%). This indicates that different Pb phases may be enriched in different particle size fractions of Broken Hill soil, influencing bioavailability/bioaccessibility and exposure via incidental ingestion and inhalation routes.

3.3. Link between inhalation bioaccessibility and total Pb concentration

Lead inhalation bioaccessibility (%) using Hatch’s solution (Fig. 1A) was the highest in PP (48.4 ± 2.0%), followed by BHK6, BHK11 and BHK10 (37.5 ± 0.9%, 34.6 ± 0.9% and 32.7 ± 0.3% respectively), while the lowest Pb bioaccessibility was observed in BHK5 (24.5 ± 0.5%). Due to elevated Pb concentration (7796 ± 49.3 mg/kg) and bioaccessibility (48.4 ± 2.0%), PP PM10 showed the greatest potential for Pb dissolution in the lung lining fluid within 24 h following inhalation (3513 mg/kg, Fig. 1A). In contrast, despite having a similarly elevated Pb concentration (6027 ± 163 mg/kg), lower Pb bioaccessibility in Hatch’s solution was observed for BHK5 compared to PP (1446 ± 28.8 mg/kg). Similar Pb concentration and bioaccessibility using Hatch’s solution were observed for BHK10 and BHK 11 (Pb dissolution of 680 ± 5.6 and 629 ± 16.3 mg/kg respectively), while BHK6 exhibited both low Pb concentration and low potential for Pb dissolution using Hatch’s solution (782 ± 117 mg/kg and 292 ± 7.0 mg/kg respectively).

Fig. 1.

Concentrations of total (mg/kg) and bioaccessible Pb (%) in mining/smelting impacted PM10 following extraction using Hatch’s solution (A) and ALF (B) for 24 h.

In contrast to Pb bioaccessibility outcomes using Hatch’s solution, higher bioaccessibility values were observed across all PM10 samples when ALF was used (PP: 96.3 ± 1.9%, BHK5: 78.7 ± 2.0%, BHK6: 80.4 ± 1.4%, BHK10: 73.0 ± 3.1% and BHK11: 80.9 ± 1.5%). PP and BHK10 exhibited the highest and lowest potential for Pb dissolution simulating the acidic environment inside the lysosome of alveolar macrophage within 24 h (6938 ± 133 mg/kg and 629 ± 11.0 mg/kg respectively). Despite showing similar percentage Pb bioaccessibility values in ALF, potential Pb exposure resulting from phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages was ~3 fold higher in BHK5 (4745 ± 119 mg/kg) compared to BHK10 and BHK11 (1517 ± 65.2 mg/kg and 1471 ± 27.8 mg/kg respectively) due to elevated total Pb concentrations.

Higher Pb and other trace element bioaccessibility in ALF compared to simulated lung epithelial lining fluids (e.g. Gamble’s/Hatch’s solution) has been widely reported and can be attributed to the acidic pH (4.5) in ALF (Gosselin and Zagury, 2020; Hernández-Pellón et al., 2018; Kastury et al., 2018a; Kastury et al., 2018b) compared to the near-neutral pH in Gamble’s/Hatch’s solution. However, the mass of particles that may undergo phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages [i.e. particles between 1 and 2 μm in sizes (d’Angelo et al., 2014)] is smaller than that the total mass of particles entering the respiratory system and depositing in the lung lining fluid. For example, the concentration of PM10 and PM2.5 in Broken Hill, collected over 1 h on the 19th of February 2020, was 3 μg/m3 and 1 μg/m3 respectively (Government, 2019). Therefore, despite having a higher bioaccessibility, a direct comparison between simulated lung fluids with a pH of 7.4 and 4.5 may not be appropriate and an adjustment with local PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations may be necessary before using Pb bioaccessibility outcomes in further exposure assessment processes to assess inhalation risk.

3.4. Relationship between Pb speciation and inhalation bioaccessibility

Research into Pb exposure from house dust and mining/smelting impacted dust suggests that Pb speciation play a major role in Pb bioavailability/bioaccessibility (Rasmussen et al., 2011; Kastury et al., 2019b, 2019c). By comparing the pre and post inhalation bioaccessibility assay residuals, Kastury et al. (2019b) showed that the weighted % of anglesite was reduced to a greater extent in the post bioaccessibility residuals than mineral sorbed or organic matter bound Pb. In contrast, Pb phosphate species were observed in the post bioaccessibility residuals of phosphate treated dust, that were not present prior to extraction. However, it was not clear from the study by Kastury et al. (2019b) if the change in Pb speciation in the post bioaccessibility residual dust indicated a relationship between these two factors or whether an artefact was introduced by the extraction process using simulated lung fluid. Therefore, statistical analysis was undertaken to elucidate the correlation between Pb speciation and inhalation bioaccessibility in Hatch’s solution and ALF. During the correlation analysis, data from this study was combined with those reported in Kastury et al., (2018a), (2018b) (i.e. PP 2018, SH15, CMW) and Kastury et al. (2019b) (i.e. BH) to represent additional PM10 and PM2.5 samples with differing Pb concentrations and speciation, while keeping the bioaccessibility assay and speciation methodology identical to this study. Briefly, PP2018 refers to PM10 and PM2.5 collected in close proximity to the PP PM10 sampling site used in this study (PP2018 = Pb concentration in PM10: 6968 ± 498 mg/kg, Pb concentration in PM2.5: 7454 ± 485 mg/kg; speciation in both PM10 and PM2.5 = Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide: 64%, organic matter bound Pb: 28%, plumbojarosite: 8%). SH15 refers to non-ferrous slag impacted PM10 and PM2.5 collected from York Peninsula, South Australia (SH15 = Pb concentration in PM10: 6968 ± 498 mg/kg, Pb concentration in PM2.5: 7454 ± 485 mg/kg; speciation in PM10: Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide: 63%, Pb phosphate: 37%; speciation in PM2.5: Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide: 72%, Pb phosphate: 28%). CMW PM10 and PM2.5 was collected from calcinated mine waste in Victoria, Australia (CMW = Pb concentration in PM10: 1302 ± 85.2 mg/kg, Pb concentration in PM2.5: 1803 ± 10.1 mg/kg; speciation in PM10: Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide: 52%, organic matter bound Pb: 48%; speciation in PM2.5: Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide: 48%, organic matter bound Pb: 52%). Additionally, BH refers to PM10 collected from Broken Hill (Pb concentration: 62,039 ± 736 mg/kg; Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide: 20%, organic matter bound Pb: 8%, anglesite: 66%, plumbojarosite: 7%). Bioaccessibility of Pb in PP2018, SH15, CMW and BH using Hatch’s solution were 36.3%, 33.2%, 37.6% and 61.7% respectively, while values using ALF were 85.7%, 63.3%, 40.0% and 80.9 ± 1.5% (Kastury et al., 2018a, 2018b; 2019b and unpublished data).

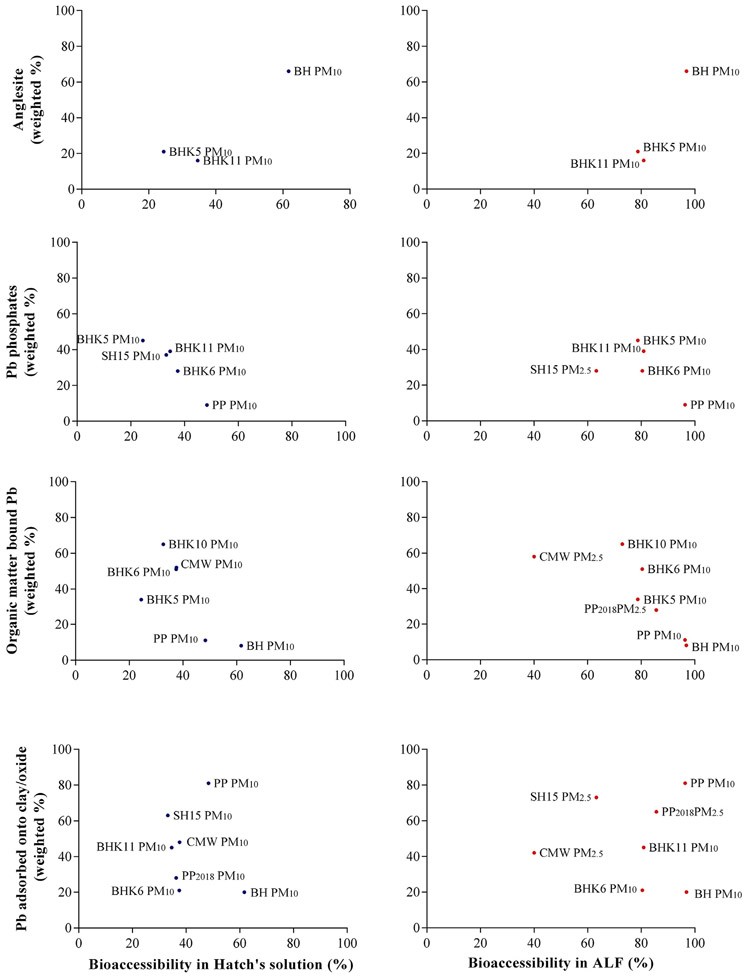

The relationship between Pb bioaccessibility (%) and Pb speciation [weighted % of Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide, organic matter bound Pb, Pb phosphate (pyromorphite + Pb3(PO4)2), anglesite] is provided in Fig. 2, where the left panel (blue dots) represents Hatch’s solution and the right panel (red dots) represents ALF. Pearson r values with 95% confidence intervals, r2 and p values are provided in Table S1. Fig. 2 highlights a significant positive correlation between anglesite weighted % and Pb bioaccessibility in Hatch’s solution (r: 0.6246, p: 0.0361), although this result should be interpreted with caution because of the limited data points from which the relationship was derived. Anglesite is a weathering product of galena and is soluble over a pH range of 2–7 (Zhang and Ryan, 1998). Therefore, a significant positive correlation using Hatch’s solution suggests a greater propensity for Pb absorption from the dissolution of Pb in the lung lining fluid following inhalation of PM10 with high anglesite content. In contrast, Pb phosphate weighted % showed a significant negative correlation to Pb bioaccessibility (%) using Hatch’ solution (r: −0.9610, p: 0.0046). Low oral bioavailability of Pb phosphate is well established (Scheckel et al., 2013) and a negative correlation with inhalation bioaccessibility suggests that PM10 containing elevated Pb phosphate may similarly result in low inhalation bioavailability. Although low oral bioavailability of galena has also been reported previously (Scheckel et al., 2013), because of the smaller number of samples that contained galena and plumbojarosite, their individual correlation to bioaccessibility using simulated lung fluids could not be determined. Therefore, combined weighted % of Pb phosphate, galena and plumbojarosite was plotted against inhalation bioaccessibility to assess if the negative correlation that was evident between Pb inhalation bioaccessibility and Pb phosphate holds when the combined weighted % of Pb phosphate + galena + plumbojarosite was considered (Fig. 3). A significant and strong negative correlation of −0.9350 (p: 0.0099) between Pb phosphate + galena + plumbojarosite and bioaccessibility using Hatch’s solution (Fig. 3, left) indicated that the presence of these three species may be linked to low inhalation exposure.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between Pb bioaccessibility (%) and Pb speciation (weighted %) of anglesite, Pb phosphate, organic matter bound Pb and Pb adsorbed onto clay/oxide in PM10 using Hatch’s solution (left) and ALF (right). Lead bioaccessibility and speciation data from Kastury et al. (2018a, 2018b; 2019b; PP2018, SH15, CMW and BH) were included in correlation analysis.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between Pb bioaccessibility (%) and speciation (weighted % of Pb phosphate + galena + plumbojarosite) in PM10 using Hatch’s solution (left) and ALF (right).

A negative correlation between inhalation bioaccessibility using Hatch’s solution and organic bound Pb was also observed as detailed in Fig. 2 (r: −0.7079), although the strength of the relationship was moderate (r2: 0.5011) and the p value (0.0578) indicated that this relationship was significant at α = 0.1. However, the negative correlation suggests that the presence of organic bound Pb species in PM10 may lower Pb dissolution in the lung. This result is in contrast with conclusions of Rasmussen et al. (2011) and Fujimori et al. (2018) who assessed Pb oral bioaccessibility using the Solubility Bioaccessibility Research Consortium (SBRC; pH 1.5) assay and physiologically based extraction test (PBET; pH 2.5). Relative gastric phase bioaccessibility (using Pb acetate bioaccessibility as the reference) of Pb citrate and Pb humate was 0.84 and 0.85 respectively (Rasmussen et al., 2011), suggesting high Pb exposure following exposure to these forms of Pb. Although Fujimori et al. (2018) did not report the value of correlation coefficient between Pb gastric bioaccessibility and % of Pb citrate, it was suggested that Pb citrate may be linked with high oral bioaccessibility. However, the negative correlation between organic bound Pb and Pb inhalation bioaccessibility using Hatch’s solution suggests that the near-neutral pH (7.4) of the lung phase assay may contribute to the low Pb bioaccessibility from PM10 containing high organic bound Pb. Another factor that may contribute to the organic-bound Pb-inhalation bioaccessibility relationship in this study compared to the results in Rasmussen et al. (2011) is the impact of matrix effects on Pb dissolution. For example, pure Pb compounds in the form of Pb citrate and Pb humate were used directly during the assessment of gastric phase bioaccessibility in Rasmussen et al. (2011), while the weighted % of organic bound Pb in PM10 was used during correlation analysis with Pb inhalation bioaccessibility. It is therefore possible that the dissolution of Pb bound to the organic component was incomplete at a pH of 7.4 when it is associated with fine particulate matter.

In contrast to Pb species discussed above, no significant correlation was found between the weighted % of Pb adsorbed to clay/oxide and inhalation bioaccessibility using Hatch’s solution (r: −0.1685, r2: 0.0284 and p: 0.3590). Similarly, no correlation was observed between any Pb species and inhalation bioaccessibility using ALF (Figs. 2 and 3 and Table S1). Previously, Rasmussen et al. (2011) observed that Pb adsorbed onto gibbsite/goethite exhibited high Pb relative bioaccessibility (0.85 and 0.89 respectively) in gastric solution. However, it is unclear from our data the influence of Pb adsorbed to clay/oxide on inhalation bioaccessibility at pH of 7.4 (Hatch’s solution) and 4.5 (ALF), warranting future research with pure compounds and/or larger sample numbers. It is also noteworthy that bias or error may be present in the correlation values reported in this study because of the limited number of samples used. Additional research is necessary to confirm the relationships observed here with larger number of samples containing a wider range of Pb species from multiple sources of Pb contamination.

3.5. Relationship between simulated lung fluid composition and inhalation bioaccessibility

To investigate the role of simulated lung fluid composition on inhalation bioaccessibility outcomes, PP PM10 [Fig. A (i)] and the residual particles after extraction using Hatch’s solution [Fig. B (i)] and ALF [Fig. C (i)] were visualized using SEM, with the quantitative composition of elements in Pb rich particle regions analyzed using EDX. Fig. 4A (ii) shows that in PP PM10, Pb rich regions were comprised of Pb (47.7%) and oxygen (O, 31.5%), while As, Silicon (Si) and Aluminum (Al) were minor elemental constituents (9.1, 6.7 and 1.7% respectively). Fig. 4A (iii) shows the elemental composition of a second particle within PP PM10, not suspected to be rich in Pb according to the backscattered electron, analyzed using EDX to provide an indication of elemental composition of the PP PM10 matrix. Fig. 4A (iii) suggests that non-Pb rich regions of PP PM10 may be composed of predominantly O (59.5%) and Si (29.7%), with Pb (5.6%), Al (1.9%), As (1.2%) and Fe (0.9%) as minor constituents.

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron microscopy of PP PM10 particles using backscatter mode (left) and analysis of elemental composition using Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (right). A: PM10 particle before bioaccessibility assay, B: PM10 particle in post bioaccessibility assay residual after extraction using Hatch’s solution for 24 h, C: PM10 particle in post bioaccessibility assay residual after extraction using ALF for 24 h.

The elemental composition of a Pb rich region on a particle after extraction using Hatch’s solution for 24 h [Fig. 4B (ii)] was found to be predominantly composed of O (31.3%), Pb (23.4%), Ca (20.9%) and P (10.5%), with smaller components of Si (5.3%), Al (3.9%), Fe (2.1%) and Cl (1.0%). However, after extraction in ALF, the elemental composition was similar to the non-extracted PM10 (Pb: 53.8%, O: 20%, Cu: 7.2%, Si: 4.1% and Al: 2.4%) [Fig. 3C (ii)], although the particle exterior was visibly smoother [Fig. 4C (i)]. Wragg and Klinck (2007) reported that a porous layer (2.5 μm thick) of Pb–Si–P–Al–O formed outside a galena particle when Gamble’s solution was used to assess inhalation bioaccessibility, which may have prevented further Pb dissolution from the particle over time. The penetration depth of the elements analyzed in this study was estimated to be 3–4 μm (Goldstein et al., 2017). Therefore, it can be assumed that a layer of O–Pb–Ca–P–Si–Al–Fe (~3–4 μm thick) was formed on the outside of the PP PM10 particle during extraction with Hatch’s solution, which may have prevented further Pb dissolution from the particle. Zhang and Ryan (1998) reported that at a pH of 6–7, pyromorphite may precipitate on the outer surface of Pb particles, which was unlikely at a pH range of 4–5, presumably due to the increased acidity increasing the rate of Pb dissolution. Although few studies have investigated the change in Pb speciation in vivo, Kastury et al. (2019c) reported an increase in Pb phosphate weighted % in residual particles within mouse lungs after 8–24 h, with a corresponding reduction in Pb absorption into the systemic circulation. Therefore, the observation of O–Pb–Ca–P–Si–Al–Fe on the PM10 particle after extraction using Hatch’s solution (pH of 7.4), may be likened to a pyromorphite-type precipitation on the outer surface of a Pb rich particle. In contrast, an absence of such a layer when ALF was used to assess inhalation bioaccessibility can be attributed to the pH of 4.5 of the assay. It is not clear if the static nature of an in vitro test may augment the extent to which this layer is formed using simulated lung fluid (thereby reducing Pb bioaccessibility) compared to simultaneous absorption of dissolved Pb ions in vivo. Given the wide difference in Pb bioaccessibility outcomes when two different simulated lung fluids were used (with varying composition and pH), future research should focus on establishing an in vivo in vitro correlation in order to determine which simulated lung fluid provides the best estimate of inhalation bioavailability. When assessing Pb inhalation bioaccessibility outcomes, additional factors should be taken into account by focusing on the integration of two bioaccessibility outcomes through an understanding of how different fractions dissolve in different lung compartments and how it relates to in vivo absorption.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Farzana Kastury was supported by the VC and President’s Scholarship and the MF & MH Joyner Scholarship in Science, by the University of South Australia. This project was supported in part for Ranju Karna by an appointment to the Internship/Research Participation Program at the National Risk Management Research Laboratory, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and EPA. Although EPA contributed to this article, the research presented was not performed by or funded by EPA and was not subject to EPA’s quality system requirements. Consequently, the views, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect or represent EPA’s views or policies. MRCAT operations are supported by the Department of Energy and the MRCAT member institutions. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The authors would like to acknowledge the help of Professor John Boland during statistical analysis of the results.

Footnotes

This paper has been recommended for acceptance by Dr. Jörg Rinklebe.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114609.

References

- Arif M, Islam MT, Shekhar HU, 2018. Lead induced oxidative DNA damage in battery-recycling child workers from Bangladesh. Toxicol. Ind. Health 34, 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR, 2007. Toxicological Profile for Lead. Accessed on. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp13-c6.pdf. (Accessed 14 January 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Berlinger B, Ellingsen DG, Náray M, Záray G, Thomassen Y, 2008. A study of the bio-accessibility of welding fumes. J. Environ. Monit 10, 1448–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisa N, Elom N, Dean JR, Deary ME, Bird G, Entwistle JA, 2014. Development and application of an inhalation bioaccessibility method (IBM) for lead in the PM10 size fraction of soil. Environ. Int 70, 132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Angelo I, Conte C, La Rotonda MI, Miro A, Quaglia F, Ungaro F, 2014. Improving the efficacy of inhaled drugs in cystic fibrosis: challenges and emerging drug delivery strategies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 75, 92–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusseldorp A, Kruize H, Brunekreef B, Hofschreuder P, De Meer G, Van Oudvorst A, 1995. Associations of PM10 and airborne iron with respiratory health of adults living near a steel factory. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 152, 1932–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA, 1998. Method 6020A (SW-846): Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry. Revision 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fent GM, Evans TJ, Bannon DI, Casteel SW, 2008. Lead distribution in rats following respiratory exposure to lead-contaminated soils. Toxicol. Environ. Chem 90, 971–982. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori T, Taniguchi M, Agusa T, Shiota K, Takaoka M, Yoshida A, Terazono A, Ballesteros FC Jr., Takigami H, 2018. Effect of lead speciation on its oral bioaccessibility in surface dust and soil of electronic-wastes recycling sites. J. Hazard Mater 341, 365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JI, Newbury DE, Michael JR, Ritchie NW, Scott JHJ, Joy DC, 2017. Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Microanalysis. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin M, Zagury GJ, 2020. Metal (loid)s inhalation bioaccessibility and oxidative potential of particulate matter from chromated copper arsenate (CCA)-contaminated soils. Chemosphere 238, 124557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government, N., 2019. Rural Air Quality Network - Live Data. https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/air/monitoring-air-quality/regional-and-rural-nsw/rural-monitoring-stations/live-air-quality-data. Accessed 05/11/2019.

- Hayes SM, Webb SM, Bargar JR, O’Day PA, Maier RM, Chorover J, 2012. Geochemical weathering increases lead bioaccessibility in semi-arid mine tailings. Environ. Sci. Technol 46, 5834–5841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Pellón A, Nischkauer W, Limbeck A, Fernández-Olmo I, 2018. Metal(loid) bioaccessibility and inhalation risk assessment: a comparison between an urban and an industrial area. Environ. Res 165, 140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz AL, Gancarz D, Herde C, McClure S, Scheckel KG, Smith E, 2014. In situ formation of pyromorphite is not required for the reduction of in vivo Pb relative bioavailability in contaminated soils. Environ. Sci. Technol 48, 7002–7009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastury F, Placitu S, Boland J, Karna RR, Scheckel KG, Smith E, Juhasz AL, 2019a. Relationship between Pb relative bioavailability and bioaccessibility in phosphate amended soil: uncertainty associated with predicting Pb immobilization efficacy using in vitro assays. Environ. Int 131, 104967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastury F, Smith E, Doelsch E, Lombi E, Donnelley M, Cmielewski P, Parsons D, Scheckel KG, Paterson DJ, de Jonge MD, 2019b. In vitro, in vivo and spectroscopic assessment of lead exposure reduction via ingestion and inhalation pathways using phosphate and iron amendments. Environ. Sci. Technol 53, 10329–10341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastury F, Smith E, Lombi E, Donnelley MW, Cmielewski PL, Parsons DW, Noerpel M, Scheckel KG, Kingston AM, Myers GR, 2019c. Dynamics of lead bioavailability and speciation in indoor dust and X-ray spectroscopic investigation of the link between ingestion and inhalation pathways. Environ. Sci. Technol 53, 11486–11495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastury F, Smith E, Karna RR, Scheckel KG, Juhasz A, 2018a. An inhalation-ingestion bioaccessibility assay (IIBA) for the assessment of exposure to metal(loid)s in PM10. Sci. Total Environ 631, 92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastury F, Smith E, Karna RR, Scheckel KG, Juhasz A, 2018b. Methodological factors influencing inhalation bioaccessibility of metal(loid)s in PM2.5 using simulated lung fluid. Environ. Pollut 241, 930–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropf A, Katsoudas J, Chattopadhyay S, Shibata T, Lang E, Zyryanov V, Ravel B, McIvor K, Kemner K, Scheckel K, 2010. The New MRCAT (Sector 10) Bending Magnet Beamline at the Advanced Photon Source. AIP Conference Proceedings AIP, pp. 299–302. [Google Scholar]

- Lanphear BP, Hornung R, Khoury J, Yolton K, Baghurst P, Bellinger DC, Canfield RL, Dietrich KN, Bornschein R, Greene T, 2005. Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: an international pooled analysis. Environ. Health Perspect 113, 894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard E, Thomas R, Simon D, Phipps C, Ward C, Calder I, 2003. An evaluation of recent blood lead levels in Port Pirie, South Australia. Sci. Total Environ 303, 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meza-Figueroa D, Maier RM, de la O-Villanueva M, Gómez-Alvarez A, Moreno-Zazueta A, Rivera J, Campillo A, Grandlic CJ, Anaya R, Palafox-Reyes J, 2009. The impact of unconfined mine tailings in residential areas from a mining town in a semi-arid environment: nacozari, Sonora, Mexico. Chemosphere 77, 140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEPM, 2013. National Environment Protection (Assessment of Site Contamination) Measure. Schedule B (1) - Guideline on Investigation Levels for Soil and Groundwater. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2013C00288. Accessed 02/04/2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ostergren JD, Brown GE, Parks GA, Tingle TN, 1999. Quantitative speciation of lead in selected mine tailings from Leadville. CO. Environmental Science & Technology 33, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Patel B, Gupta N, Ahsan F, 2015. Particle engineering to enhance or lessen particle uptake by alveolar macrophages and to influence the therapeutic outcome. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 89, 163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen PE, Beauchemin S, Chénier M, Levesque C, MacLean LC, Marro L, Jones-Otazo H, Petrovic S, McDonald LT, Gardner HD, 2011. Canadian house dust study: lead bioaccessibility and speciation. Environ. Sci. Technol 45, 4959–4965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheckel KG, Diamond GL, Burgess MF, Klotzbach JM, Maddaloni M, Miller BW, Partridge CR, Serda SM, 2013. Amending soils with phosphate as means to mitigate soil lead hazard: a critical review of the state of the science. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part B 16, 337–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheckel KG, Ryan JA, 2004. Spectroscopic speciation and quantification of lead in phosphate-amended soils. J. Environ. Qual 33, 1288–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre C, Leyarovska N, Chapman L, Lavender W, Plag P, King A, Kropf A, Bunker B, Kemner K, Dutta P, 2000. The MRCAT Insertion Device Beamline at the Advanced Photon Source. AIP Conference Proceedings AIP, pp. 419–422. [Google Scholar]

- Simon DL, Maynard EJ, Thomas KD, 2007. Living in a sea of lead—changes in blood-and hand-lead of infants living near a smelter. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol 17, 248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöstedt C, Löv Å, Olivecrona Z, Boye K, Kleja D, 2018. Improved geochemical modeling of lead solubility in contaminated soils by considering colloidal fractions and solid phase EXAFS speciation. Appl. Geochem 92, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Stopford W, Turner J, Cappellini D, Brock T, 2003. Bioaccessibility testing of cobalt compounds. J. Environ. Monit 5, 675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysalová J, Száková J, Tremlová J, Kašparovská K, Kotlík B, Tlustoš P, Svoboda P, 2014. Methodological aspects of in vitro assessment of bioaccessible risk element pool in urban particulate matter. Biol. Trace Elem. Res 161, 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbi A, Kerchich Y, Kerbachi R, Boughedaoui M, 2018. Assessment of annual air pollution levels with PM1, PM2.5, PM10 and associated heavy metals in Algiers, Algeria. Environ. Pollut 232, 252–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian S, Liang T, Li K, 2019. Fine road dust contamination in a mining area presents a likely air pollution hotspot and threat to human health. Environ. Int 128, 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA, 2007. Method 3015a Microwave Assissted Acid Digestion of Aqueous Samples and Extracts.

- Wallenborn JG, McGee JK, Schladweiler MC, Ledbetter AD, Kodavanti UP, 2007. Systemic translocation of particulate matter–associated metals following a single intratracheal instillation in rats. Toxicol. Sci 98, 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt EC, Shi H, Wronkiewicz DJ, Pavlowsky RT, 2014. Phase partitioning and bioaccessibility of Pb in suspended dust from unsurfaced roads in Missouri - a potential tool for determining mitigation response. Atmos. Environ 88, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wragg J, Klinck B, 2007. The bioaccessibility of lead from Welsh mine waste using a respiratory uptake test. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part A 42, 1223–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Chai F, Zheng Z, Yang Q, Zhong X, Fomba KW, Zhou G, 2018. Size distribution and source of heavy metals in particulate matter on the lead and zinc smelting affected area. J. Environ. Sci 71, 188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Ryan JA, 1998. Formation of pyromorphite in anglesite-hydroxyapatite suspensions under varying pH conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol 32, 3318–3324. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.