In 2016, 3.8 million people received some form of substance abuse treatment (SAMHSA, 2016). Treatment costs for substance use disorders (SUD) are responsible for 10.4% of the global burden of disease (Trautmann et al., 2016), and this cost is even higher than that of other chronic diseases such as cancer or diabetes (Whiteford et al., 2013). To deal with this problem, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) recommends that following detoxification and inpatient treatment, residential programs should provide access to recovery resources to help reintegrate individuals back into mainstream society (2015). Unfortunately, many individuals who complete substance abuse treatment are released back into the community without being provided the social, psychological and environmental supports needed for long term recovery (Monk & Heim, 2014).

Recovery homes are an important and widespread post-treatment recovery-resource (Jason et al., 1997; Jason, et al., 2007). According to the National Alliance of Recovery Residences (NARR), recovery homes can be grouped into one of four levels of homes, with the first type involving homes that are peer-run; second level being monitored with at least one compensated position; third level having supervision, organizational hierarchy, and some certified staff; and the fourth level being through a service provider with clinical and administrative supervision, and credentialed staff (Jason et al., 2013; NARR, 2011). There is some evidence that these homes are effective. For example, Jason et al. (2006) recruited 150 individuals finishing substance use treatment, half were randomly assigned to live in a recovery home while the other half received usual care services. Two-year follow-up results indicated significantly lower substance use among participants in the recovery home condition compared to those in the usual care condition. It is very possible that recovery housing is an important resource for those in recovery.

Unfortunately, we do not have the most basic information such as how many recovery homes exist in the United States. There are databases within certain states and lists of recovery homes at other sites, but no comprehensive listing is available. The current study aimed to gather data from existing databases and by interviewing SUD experts in order to estimate the number of recovery homes in the United States.

Methods

Procedure

We conducted an online search across organizational databases of recovery homes in the United States, using publicly available information derived from several organizations. The first organization was Oxford House (2020), which is the largest network of democratically self-run recovery homes in the United States. Oxford Houses are chartered, and members must be abstinent, pay their fair share of expenses (i.e., rent), and comply with house rules. Secondly, we searched the records of NARR (2020), which lists recovery homes that are registered with state organizations. Most of these recovery homes have paid professional staff or personnel to help manage the settings. Third, we searched a database for recovery homes that is made available from the federal government (SAMHSA, 2020), which requires their listed houses to provide substance use treatment services to people with SUD. In addition, these facilities must have either licensure/accreditation/approval from states’ substance use agency or national accrediting body; staff in the house hold specialized credentials to provide SUD treatment; or the facility has authorization to bill third-party payers for treatment services using an alcohol or drug client diagnosis. Finally, we searched the database from Intervention America (2020), which allows any recovery home to submit their information to be listed on their site. Oxford House and NARR have the strictest verification processes, requiring new recovery homes to be formally accepted after completing, and submitting an application.

A second source of data was derived from brief phone call interviews with NARR state representatives who were asked two questions: (1) How many recovery residences are registered with NARR in your respective state; and (2) How many recovery residences do you estimate there are in your state that are not registered with NARR? A total of 21 NARR representatives from 21 states in the United States were interviewed.

Results

There were 276 recovery homes listed simultaneously on the SAMHSA and Intervention America websites. None of the recovery homes were counted twice. We did not find any overlap between the houses listed with Oxford House and NARR. In addition, when the NARR interviewees indicated that there were non-Oxford House recovery houses in their states that were not registered with NARR, we counted these residences in the total number for that state.

We found 2,355 Oxford Houses; 1,470 recovery homes in NARR; 1,125 homes in SAMHSA; and 12,993 in Intervention America. Intervention America had the largest number of recovery homes, and this was probably due to this organization having the fewest requirements for being listed. Table 1 shows the number of homes per state in the United States, and we estimate that there are currently 17,943 recovery homes. California, New York, and Florida have the largest number of recovery homes. This suggests that there are more recovery homes on the east and west coast of the United States. Montana and Vermont, which have much smaller populations, had the fewest number of recovery homes [see Table 1].

Table 1.

Total of Estimated Recovery Homes by State

| State | Total | State | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 115 | Montana | 40 |

| Alaska | 71 | Nebraska | 136 |

| Arizona | 246 | Nevada | 106 |

| Arkansas | 50 | New Hampshire | 50 |

| California | 2432 | New Jersey | 471 |

| Colorado | 462 | New Mexico | 102 |

| Connecticut | 228 | New York | 1073 |

| D.C. | 91 | North Carolina | 604 |

| Delaware | 114 | North Dakota | 53 |

| Florida | 1037 | Ohio | 478 |

| Georgia | 256 | Oklahoma | 281 |

| Hawaii | 179 | Oregon | 411 |

| Idaho | 67 | Pennsylvania | 544 |

| Illinois | 757 | Rhode Island | 114 |

| Indiana | 416 | South Carolina | 160 |

| Iowa | 125 | South Dakota | 62 |

| Kansas | 375 | Tennessee | 278 |

| Kentucky | 359 | Texas | 907 |

| Louisiana | 293 | Utah | 165 |

| Maine | 239 | Vermont | 45 |

| Maryland | 476 | Virginia | 268 |

| Massachusetts | 492 | Washington | 751 |

| Michigan | 626 | West Virginia | 103 |

| Minnesota | 370 | Wisconsin | 266 |

| Mississippi | 119 | Wyoming | 63 |

| Missouri | 417 | SUM TOTAL | 17,943 |

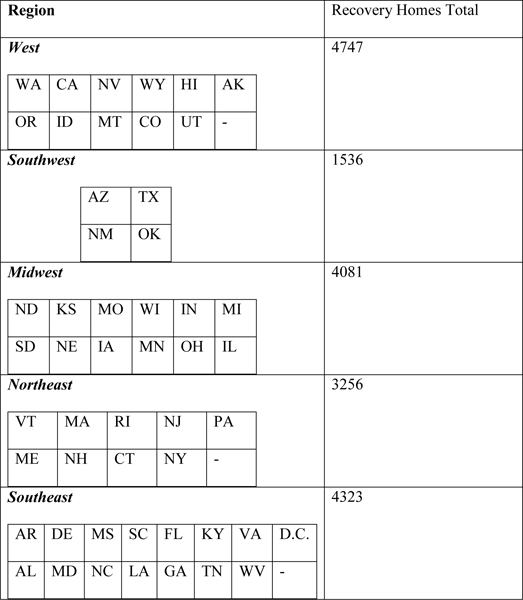

To further investigate our estimates on a regional level, we grouped the states into five regions designated by the National Geographic Society (2012) [see Table 2]. The regional West has the highest estimated total at 4,747 homes, followed by the regional Southeast at an estimated total of 4,323 homes. The regional Midwest had an estimated total of 4,081 homes and the regional Northeast had an estimated total of 3,256 homes. The regional Southwest had the fewest estimated total at 1,536 homes, but this region includes four large but not densely populated states.

Table 2.

Total of Estimated Recovery Homes by Region

|

We used the number of recovery homes to estimate the percentage of individuals with a SUD who use recovery homes in a year. According to the National Survey of Drug Use and Health, roughly 23.7 million individuals, aged 18 or older, have a SUD or Alcohol use disorder (McCance-Katz, 2019). To estimate the average length of stay in a recovery home, Jason and Ferrari (2010) reported that the average length of stay within Oxford Homes is about 10 months, whereas Polcin et al. (2010) found that the average person resided in the homes roughly 5 to 8 months. From these estimates, we estimated the average of the length of stay in a recovery home is about 7 months. Jason and Ferrari (2010) found that Oxford homes have about 6 to 10 beds per home, whereas Polcin et al. (2010) found sober living homes had about 8 to 14 beds per home. From these studies, we estimated that there might be about 9 beds per home. Over a period of one year, we estimate each bed is used by 1.7 (12/7) individuals. Each house would therefore have 15.3 (9 × 1.7) individuals residing in it per year. We multiplied this number by the number of estimated recovery homes in order to calculate 274,528 (15.3 × 17,943) individuals utilize recovery homes each year. We then estimated that about 1.2% (274,528/23,700,000) of individuals with SUD use recovery homes each year in the United States.

Discussion

This is a preliminary investigation of the existing network of recovery homes in the United States. We had limited objectives in this study to try to come up with an estimate of the number of recovery residences, which we believe to be an important source of social capital available throughout the United States for individuals who are seeking recovery residential environments. We embarked on this investigation, because existing datasets are neither comprehensive nor coordinated. As we worked on this study, it became clear to the authors that this is a need for the development of a comprehensive listing of the number or location of recovery homes, their availability, and information on the types of offered services. Such an updated and centralized database would be extremely helpful to individuals with SUDs seeking residential recovery settings.

Environmental factors, including housing, employment, and reliable sober-living settings, can affect the degree and types of support a patient receives. Community-based support groups, such as NA and AA, do offer immediate support, but they do not provide needed housing and employment for those most at risk of relapse. Recovery homes are currently the largest residential recovery-specific, community-based support option. These settings have been especially important in providing support for high-risk, low-resource individuals who frequently cycle through substance use treatment programs, often failing to maintain abstinence because of their tenuous financial and social linkages to the mainstream community. These immersive sober living environments are specifically intended to augment nonmember friend and family relationships by providing possibly hard to find companionship for those attempting the transition from new sobriety to self-sustaining recovery. Since individuals in recovery homes are all, to one degree or another, goal-driven to stay clean and abstinent, these goal-focused networks may be particularly suitable for these individuals because homogenous and insular networks of individuals can help to conserve existing resources while providing social support. Having a better idea of the location and availability of these homes would be a major help for treatment providers, families of those in recovery, as well as those with SUDs seeking an abstinent and safe environment.

Oxford House Inc. does monitor their network of homes and NARR certifies house in many states. Regrettably, many recovery homes do not have an organization supervising or overseeing their operations. The absence of regulations, licenses, or certifications provide variability in the quality of care, and inadvertently create unfortunate opportunities for exploitation of recovery home residents. For example, in the state of Florida, the opioid crisis combined with limited legislative oversight has created an economic environment for fraud (Palm Beach County Sober Homes Task Force Report, 2017). The need of oversight was especially emphasized in 2017, when a recovery home owner in Tallahassee, Florida was convicted for nearly $19 million in payments from double billing for urinalysis testing and charging patients’ insurance companies for treatments that were not received (U.S. v. Snyder & Fuller, 2017). He also charged insurance companies after clients have left the facility (U.S. v. Snyder & Fuller, 2017). Sometimes abuse goes beyond financial exploitation such as when a Colorado recovery homeowner was convicted of sexually assaulting the female residents (Osher, 2018). This recovery homeowner, who had several residences in Colorado and Southern California, was notorious for providing controlled substances to his clients; subsequently causing several of his clients to relapse and overdose (Osher, 2018). These types of abuses have even prompted some legislators to act against these recovery homeowners (Stewart et al., 2019).

Future research should investigate whether the number of recovery homes in the United States are increasing or decreasing over time, as well as reasons for why some regions that have a higher concentration of these homes. It is certainly possible that states with the highest populations like California, New York, and Florida, have the highest number of recovery homes to meet the needs of their residents. The West, Southeast and Midwest regions have the most recovery homes, and there is also a need to understand what factors (i.e. climate, drug use, policy and legislation, or population and large cities) may contribute to this concentration.

There are a few limitations in the current study. For example, this study did not investigate the types of services provided at these recovery homes. In addition, this study was not able to determine whether these types of homes are expanding or decreasing. Also, this investigation did not explore the overall effectiveness of the network of houses, or the mechanisms for producing change. Lastly, these figures are only estimates and some recovery homes may operate without being listed on the databases we used or the state experts that we interviewed might not have been aware of some recovery homes.

In summary, while there are important recovery opportunities for residents of this network of sober living homes, there are also risks to those residents. The estimate that only about 1.2% of individuals with SUD use these recovery resources suggest that there might be opportunities for expansion of this network of environmental supports. We believe that it is important to create a database detailing the licenses, affiliations, locations, and availability of all recovery residences. A database may help reduce abuse by detailing the available resources and protections for each respective recovery home. There is a clear need to better understand the true scope of recovery housing throughout the United States, which might ultimately allow matching of clients to houses that might best meet their needs. These types of efforts would further our understanding of best practices in recovery housing in order to increase the availability of well- managed and maintained recovery homes. It is also important to better understand why people choose not to access recovery homes, whether it involves preference for staying with family or friends, a lack of availability, awareness of, or some other reason like stigma.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the financial support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant number AA022763). We acknowledge the help of members of the Oxford House organization and the National Alliance of Recovery Residences.

References

- Intervention America (2020). Intervention America is a drug rehab directory of treatment centers. Retrieved from https://interventionamerica.org/

- Jason LA, Davis MI, Ferrari JR, & Anderson E (2007). The need for substance abuse after-care: Longitudinal analysis of Oxford House. Addictive Behaviors, 32(4), 803–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Ferrari JR, Smith B, Marsh P, Dvorchak PA, Groessl EK, Pechota ME, Curtin M, Bishop PD, Knot E, & Bowden BS (1997). An exploratory study of male recovering substance abusers living in a self-help, self-governed setting. Journal of Mental Health Administration, 24, 332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Olson BD, Ferrari JR, & Lo Sasso AT (2006). Communal housing settings enhance substance abuse recovery. American Journal of Public Health, 96(10), 1727–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, & Ferrari JR (2010). Oxford House Recovery Homes: Characteristics and Effectiveness. Psychological services, 7(2), 92–102. 10.1037/a0017932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Mericle AA, Polcin DL, & White WL (2013). The role of recovery residences in promoting long-term addiction recovery. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52, 406–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCance-Katz EF (2019). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2017. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/nsduh-ppt-09-2018.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk RL, & Heim D (2014). A real-time examination of context effects on alcohol cognitions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38(9), 2454–2459. https://doi.com/10.1111/acer.12504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Recovery Residences (2020). Retrieved from https://narronline.org/

- National Alliance for Recovery Residences (2011). Standard for Recovery Residences. Retrieved from https://narronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/NARR-Standards-20110920.pdf

- National Geographic Society. (2012). United States Regions. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.org/maps/united-states-regions/#us-regions-map-1

- Osher C (2018) Police found fraud, sex crimes in a Colorado sober-living home empire. The state doesn’t regulate the industry. Denver Post. Published March 11, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.denverpost.com/2018/03/11/colorado-sober-living-homes-opioid-crisis-christopher-bathum/ [Google Scholar]

- Oxford House (2020). Directory of Oxford Houses. Retrieved from https://www.oxfordhouse.org/userfiles/file/house-directory.php

- Palm Beach County Sober Homes Task Force Report (2017). Retrieved from http://www.sa15.state.fl.us/stateattorney/SoberHomes/_content/SHTFReport2017.pdf

- Polcin DL, Korcha R, Bond J, & Galloway G (2010). What did we learn from our study on sober living houses and where do we go from here? Journal of psychoactive drugs, 42(4), 425–433. 10.1080/02791072.2010.10400705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart MT, O’Brien M, Shields MC, & Mulvaney-Day N State Residential Treatment for Behavioral Health Conditions: Regulation and Policy Environmental Scan (2019). A report written under contract for the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Health and Human Services [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2015). Federal guidelines foropioid treatment programs. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA’s Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) 2002 – 2012 (2012). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/TEDS2012N_Web.pdf

- SAMHSA (2020). Findtreatment.gov. Retrieved from. https://findtreatment.gov/

- Trautmann S, Rehm J, & Wittchen HU (2016). The economic costs of mental disorders. EMBO Reports, 17(9), 1245–1249. 10.15252/embr.201642951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder U.S. v. & Fuller (2017). United States of America v. Eric Snyder and Christopher Fuller, 18 U.S.C. 1349 (S.D. Fla. 2017). Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, … & Burstein, R. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 382(9904), 1575–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]