Abstract

Neurological complications of COVID-19 have been described. We present the case of a 27-year-old woman who developed COVID-19 in April 2020. She continued to present anosmia and ageusia eight months later. Six months after contracting COVID-19, she developed dysesthesia, hypoesthesia and hyperreflexia. Her magnetic resonance imaging showed demyelinating lesions, of which two were enhanced by gadolinium. She was positive for oligoclonal bands in her spinal fluid. This patient developed multiple sclerosis with a temporal relationship to COVID-19. We believe that SARS-CoV-2 led to her autoimmune disease through a virus-induced neuroimmunopathological condition.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Anosmia

1. Introduction

In December 2019, the first case of a new human coronavirus infection (SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19) was reported in Wuhan, China. One year later, it has now caused an unprecedented pandemic with more than 73 million confirmed cases including 1.6 million deaths (WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), 2020). COVID-19 infection mainly affects the respiratory system but it has also shown manifestations and complications in multiple organs (Montalvan et al., 2020; Palao et al., 2020; Mao et al., 2020).

Numerous studies have presented evidence of neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19, including headache, anosmia and hypogeusia. Serious manifestations have been observed, like acute cerebrovascular diseases, impaired consciousness and skeletal muscle injury (Montalvan et al., 2020; Palao et al., 2020). However, the information available on demyelinating diseases triggered by COVID-19 remains limited. Only one case of optic neuritis, diagnosed after SARS-CoV-2 infection had been detected, has been reported (Mao et al., 2020). Although that case fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis, no gadolinium-enhancing lesions were observed. Therefore, the authors of that case presumed that the pathogenic process had started before the viral infection, and that the virus might have acted as a precipitating factor. Given the uncertainty of the current evidence, it is important to investigate the possibility of this association.

2. Case report

The present report was approved by the Ethics Committee at Universidade Metropolitana de Santos and a written consent statement was signed by the patient.

We report the case of a 27-year-old Caucasian woman who developed COVID-19 in April 2020. Her main symptoms were high temperature, dry cough, anosmia and hypogeusia. Other family members also developed COVID-19 at that time and recovered soon, but the patient reported here continued to present anosmia and ageusia eight months later. Her olfactory bulbs evolved with atrophy, as seen in recent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1 ). No neurological examination was performed at this time.

Fig. 1.

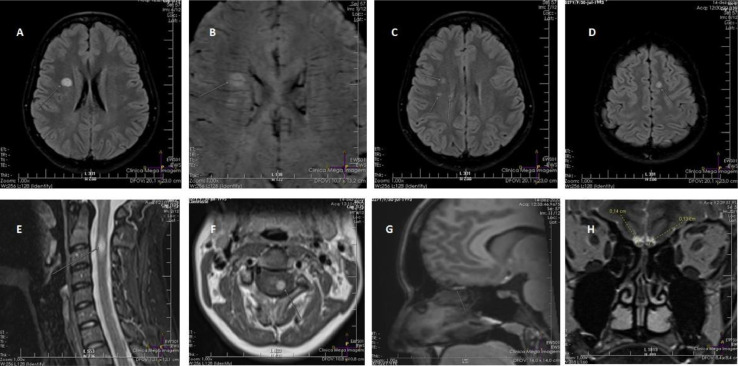

Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient two months after onset of multiple sclerosis symptoms.

A- Hyperintense lesion in the right corona radiata, in axial T2-FLAIR.

B- Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) showing a periventricular longitudinal central vein in a demyelinating lesion in the right corona radiata. The central vein sign is a marker for multiple sclerosis (9).

C- Demyelinating lesions perpendicular to the right lateral ventricle, in axial T2-FLAIR.

D- Juxtacortical lesion identified in the left superior frontal gyrus, in axial T2-FLAIR.

E- Short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) imaging in sagittal T1, showing a hyperintense lesion at C2-C3 level.

F- Axial T1 of the cervical spinal cord, showing a gadolinium-enhancing lesion in the lateral funiculus at C2-C3 level.

G- Sagittal T1 with fat saturation, showing hyperintensity in the right olfactory bulb.

H- Coronal T1, showing thinning of the olfactory bulbs.

Six months after contracting COVID-19, the patient developed a feeling that her left arm was different, like “being cold from inside”. This symptom progressed and came to affect both left limbs and the left side of the thoracic region. She was initially diagnosed as presenting “anxiety”, but the symptoms continued and, two months later, she came for a neurological consultation.

Her examination confirmed the presence of anosmia, hypoesthesia in the left limbs and left side of the thorax, and global deep tendon hyperreflexia with bilateral Babinski sign. Her magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed two gadolinium-enhancing lesions (frontal lobe and cervical spinal cord) and three other periventricular encephalic lesions. There were clear signs of a central vein inside the demyelinating lesions. Fig. 1 shows the demyelinating lesions in MRI and the persistent lesions in both olfactory bulbs. The patient's spinal fluid was positive for oligoclonal bands and had negative PCR for SARS-Co/v2. This case fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS) (Thompson et al., 2018).

-

A

Hyperintense lesion in the right corona radiata, in axial T2-FLAIR.

-

B

Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) showing a periventricular longitudinal central vein in a demyelinating lesion in the right corona radiata. The central vein sign is a marker for multiple sclerosis (9).

-

C

Demyelinating lesions perpendicular to the right lateral ventricle, in axial T2-FLAIR.

-

D

Juxtacortical lesion identified in the left superior frontal gyrus, in axial T2-FLAIR.

-

E

Short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) imaging in sagittal T1, showing a hyperintense lesion at C2-C3 level.

-

F

Axial T1 of the cervical spinal cord, showing a gadolinium-enhancing lesion in the lateral funiculus at C2-C3 level.

-

G

Sagittal T1 with fat saturation, showing hyperintensity in the right olfactory bulb.

-

H

Coronal T1, showing thinning of the olfactory bulbs.

3. Discussion

While an association between COVID-19 and MS does not necessarily signify causation, the temporal relationship between these two events and the potential SARS-CoV-2 neurotropism suggest that our patient had a virus-induced neuroimmunopathological condition.

Focal demyelination is unlikely to have been the result of direct infection by the virus in this case. Presence of SARS-CoV-2 could have led to activation of T-lymphocytes, which would be responsible for the demyelination and activation of the microglia and inflammatory mediators (Savarin and Bergmann, 2017). In addition, the persistent anosmia was associated with abnormal enhancement on MRI. A similar event had previously been reported by Aragão et al (Aragão et al., 2020).

Although the authors are fully aware of the possible coincidence in this anecdotal case, MS may be an extra possible neurological complication of COVID-19. Over time and with further observations this question may be answered.

Funding

None

Declaration of Competing Interest

None

References

- Aragão M., Leal M.C., Cartaxo Filho O.Q., Fonseca T.M., Valença M.M. Anosmia in COVID-19 associated with injury to the olfactory bulbs evident on MRI. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2020;41(9):1703–1706. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L., Jin H., Wang M., et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683–690. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvan V., Lee J., Bueso T., et al. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 and other coronavirus infections: a systematic review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020;194 doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palao M., Fernández-Díaz E., Gracia-Gil J., et al. Multiple sclerosis following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020;45 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarin C., Bergmann C.C. Viral-induced suppression of self-reactive T cells: lessons from neurotropic coronavirus-induced demyelination. J. Neuroimmunol. 2017;308:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A.J., Banwell B.L., Barkhof F., et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162–173. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed on 19 December 2020. 2.