Abstract

Tobacco consumption is one of the major public health problems in the world. Annually, 27 100 premature deaths are attributed to tobacco-related diseases in Nepal. Despite enacting different policies and strategies, the prevalence of tobacco consumption is still high. This study aims to synthesize prevalence, factors associated with its consumption and the policy initiatives for prevention and control in Nepal. This review includes peer-reviewed studies retrieved from two databases (PubMed and EMBASE) and published from 2000 to 2018, and policy initiatives on tobacco prevention and regulations in Nepal. A total of 32 studies and 5 policy documents were reviewed. Findings suggest that tobacco consumption was higher among men, illiterates, older people, people living in rural and mountainous areas and those who initiated smoking as adolescents. Peer pressure and parental/family smoking were major contributing factors for tobacco initiation. Policy analysis showed that low excise tax, weak monitoring mechanisms, poor compliance to bans on the advertisement and promotion of tobacco, smoke-free zones and insufficient programs on tobacco cessation were the major factors behind weak implementation of tobacco-control policies. Hence, targeted and high-risk group tobacco-cessation interventions, increasing taxation and strict policy implementation are crucial for effective tobacco prevention and control in Nepal.

Keywords: challenges, Nepal, policy, prevalence, smoking

Introduction

Globally almost one-third of the adult population (933 million) smoke daily,1 which is a major risk factor for multiple non-communicable diseases (NCDs) including cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.2–4 Tobacco consumption results in cancers in major vital organs2 and cumulatively causes 63% of all deaths worldwide.5 It is also the second leading cause of death and disability, accounting for 11.5% (6.4 million) of global deaths1 and 6% (148.6 million) of disability-adjusted life years.6 Almost 80% of these deaths occur in low- to middle-income countries where health services are limited.7

Annually, an estimated 27 100 deaths (14.9% of all deaths) are attributed to tobacco-related diseases in Nepal.8 The top three causes of death, ischemic heart disease, chronic respiratory disease and cardiovascular diseases (CVD), are associated with tobacco consumption.8 It is a major risk factor for lung cancer and CVD-related deaths.8 Treatment of tobacco-related diseases has put a burden on health services and increased the out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure in healthcare.9

National surveys like the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS)10,11 and WHO Step-Wise Surveillance (WHO STEP) surveys12,13 are used to estimate the national prevalence of tobacco consumption. One-fifth of people (21.6%) were tobacco users in Nepal in 2015.14 Males,4,15,16 older people,7,15,17,18 the undereducated,4,7,15,16,18 socioeconomically poor4,16,17 and those living in rural4,16,18 and mountainous15,18 regions were more likely to smoke. Peer pressure19–21 and family environment20,22,23 affected early initiation.

More than 100 industries24 in Nepal produce different forms of tobacco products like cigarettes, bidi (rolled tobacco), hookah (nargileh), sulfa and chillum or kankad.25 Furthermore, smokeless tobacco (SLT) products like surti (dry tobacco leaves), khaini (lime-mixed tobacco), gutkha (areca nut) and paan (beetle quid) with tobacco ingredients are also produced in Nepal.25 Approximately US$90 million (4.3% of total tax) was collected as an excise in 2017, which is a lucrative contribution to national revenue.26

Policies regarding the prevention and control of tobacco consumption in Nepal only began in the 1990s. Taxation on international brands in 1992 and the banning of advertisements on audiovisual media in 1998 were two major interventions.25 Later, in 2003, the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC)—the first global strategy on tobacco control―was initiated. This guided governments to formulate, implement and review comprehensive multi-sectoral national tobacco control plans and strategies. After its ratification and endorsement, Nepal endorsed legislative measures in 2010.27 After a decade of legal implementation, national representative surveys7 have reported a high and unfaltering decline in consumption prevalence. This indicates ineffective implementation of the laws with possible policy loopholes.7

Nepal has adopted the federal system after the constitution of 2015. The constitution provides authority to formulate, plan, implement and monitor the laws, policies and strategies related to health including tobacco prevention and control to all three tiers of government: federal, provincial (7) and local (753).28 Furthermore, Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) have been emphasized in the prevention and control of NCDs29 and tobacco prevention and control is one of the major strategies involved in it. Hence, the role of local governments will be crucial for the effective implementation of tobacco control policies.

Navigating the burden of tobacco consumption and its legal and policy measures are crucial to identify the status and implementation challenges associated with tobacco prevention and control. Therefore, this review aims to map the burden of tobacco consumption and explores the existing policy gaps associated with its prevention and control in Nepal.

Methods

This review was conducted in two phases. First was a narrative synthesis of evidence from peer-reviewed studies focusing on prevalence and factors associated with tobacco consumption, while the review of tobacco prevention and control policies with associated implementation challenges was performed in the second phase. For narrative synthesis, two databases (PubMed and EMBASE) were used to retrieve peer-reviewed studies. Both the authors assessed full-text articles and discussed them before selection for the review process.

Search strategy

Search terms using a combination of medical subject headings, namely, `epidemiology' OR `prevalence' OR `incidence' AND `tobacco' OR `smoking' OR `smokeless tobacco' AND `Nepal', were used to identify relevant studies. Moreover, additional relevant studies were identified by checking the reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

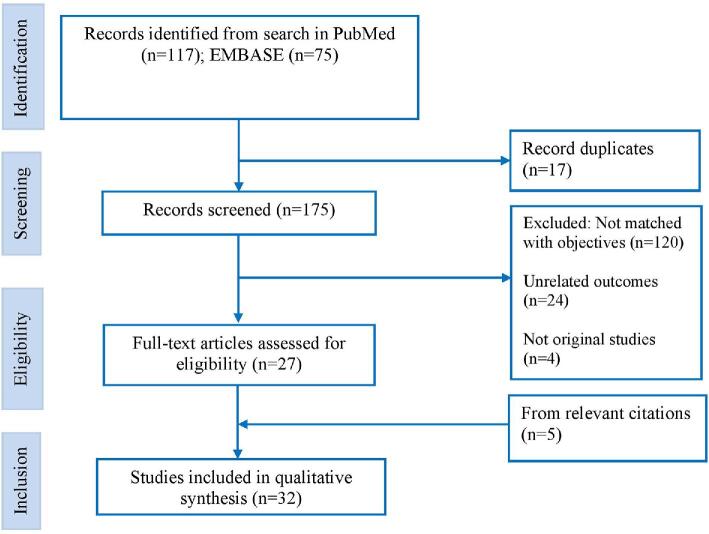

Studies published from 2000 to 2018, written in English and conducted in Nepal met the inclusion criteria. Full-text quantitative studies that reported prevalence and/or determinants of any form of tobacco consumption were included. Studies with tobacco-related diseases like CVD, cancer and chronic respiratory diseases were excluded from the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of selection of studies.

Data extraction and analysis

A table was generated that reported the first author, objective, study design, sample size and study location, the prevalence of tobacco consumption (in any form), its determinants, age of initiation (AOI) and other associated factors to extract the summary of narrative synthesis (Supplementary Table 1). Also, the existing tobacco prevention and control policies and strategies of Nepal were reviewed against current implementation challenges (Table 1).

Table 1.

Existing tobacco regulation and control policies and their implementation challenges

| MPOWER strategies | Tobacco products (prevention and control) laws | Tobacco control plan and strategies | Implementation challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monitor tobacco use and prevention policies | •Provision of inspectors and their role in policy compliance57,58•Establishing a monitoring committee at central level to formulate and implement policies57,58•Delineating the roles and responsibilities of inspectors and the committee57,58•Using health tax fund in research and investigation of tobacco-related diseases58 | •Developing toolkits for planning, monitoring and evaluation of and training for desk officers60,61•Developing tobacco control manual in line with tobacco control law60,61•Conducting BCC at national and subnational level60,61•Advocacy with concerned stakeholders•Regulation by establishing standard testing facilities61•Conducting compliance studies61•Review and amendment of legislation including violation penalty61 | •Weak implementation of planning, monitoring and evaluation framework•Weak inspection resulting poor policy compliance•No distinct appointment criteria for inspectors (any government officers can be appointed, who has several roles beside tobacco control)•Weak stakeholder coordination mechanism•Inadequate role of the committee and their ineffective implementation•Inadequate BCC interventions at national and subnational level•Limited research conducted•Low priority of research and prevention activities from the health tax fund |

| Protect people from tobacco smoke | •Delineation of public places57,58•Designated area for tobacco consumption and its criteria57,58•Noticeboard targeting public, pregnant and children aged <18 y57,58 | •Protecting from second-hand smoke•Expanding non-smoking areas60,61•Notifying smoke-free locations60,61•Awareness activities60,61•Conducting BCC campaigns60,61•Compliance monitoring by police61 | •Poor compliance of designated roles for effective implementation•Limited smoking designated zones (only in standard hotels and some airports)•Weak regulating authorities to ensure effective implementation |

| Offer help to quit tobacco use | •Organize training and capacity building programs for concerned stakeholders57•Encourage people to quit smoking57 | •Development of national cessation guidelines and manuals60,61•Establishment of tobacco cessation centers and community cessation clinics60,61•Establishment of quit-lines and telephone helplines60,61•Integration of tobacco cessation in health and education program60,61 | •Very few health personnel have been trained on cessation•Limited numbers of counselling clinics and their low priority in tobacco cessation activities•Very few quit-line services•Integrating basic health care services with tobacco prevention and control |

| Warn about the dangers of tobacco | •The package and wrapper require the facts about the contains of tobacco products58•Warning message, symbols and graphics are to be changed regularly57,58•PHWs must contain at least 90% of total outer portion59 | •Assessment of PHWs compliance•Frequent development of PHWs and its regular monitoring60•Coordinate with line ministries for effective legal enforcement60,61•Production and dissemination of BCC materials | •Handmade products have not been covered with PHWs•Covering the health warning intentionally by tobacco industries through VAT stickers7•Tobacco industries suiting writs and demanding judicial stay orders to procrastinate implementation•Poor coordination among concerned stakeholders |

| Enforce bans on TAPS | •Restriction to advertisements or promotion57,58•Vendors obligation to put notice board to restrict purchase/sales by pregnant and minors57,58•Restriction to include free or binding product sales57,58•Prohibition on single unit or retail sales57 and minimum 20 sticks cigarettes packet58•No government subsidies for tobacco industries | •Mobilization of local bodies, administration, civil societies and NGOs for banning TAPS60,61•Monitoring through coordination with other line ministries60,61•Conduct compliance survey and routine inspection of industries60,61•Development of monitoring guidelines to prohibit sales60,61•Ban smoking and tobacco use in public places60,61•Control illicit trade of tobacco products60,61•Registering and monitoring the tobacco shops60•Develop crop substitution strategy through replacement of tobacco crops60 | •TAPS through sports by tobacco industries56•Ambiguity among the concerned authorities in their respective roles and responsibilities•No licensing provision to sell tobacco products•No proof is required while purchasing tobacco items to verify age or pregnancy status•Fragile implementing institutions with poor compliance•Inadequate legal provisions for registering tobacco shops•Tobacco industries violating the packaging provision by mini-packing (10 sticks in a pack)•Governmental announcement to lure the investors to revive Janakpur Cigarette Factory |

| Raise taxes on tobacco products | •At least 25% of excise tax has to be deposited in health fund58•Health fund to be used, tobacco-related research, treatment and health awareness activities58 | •Increase resource allocation through health tax fund 60,61•Establish health tax fund for controlling consumption60,61•Assess tax structure and increase excise and tax on tobacco products regularly60,61 | •Low excise tax without annual increment•Objection by tobacco industries/pressure groups after increasing taxation•Major portion of health tax fund is used in treatment subsidies rather that prevention, control and research activities |

Abbreviations: BCC, behavioral change communication; NGOs, Non-governmental Organizations; TAPS, tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship; VAT, value-added tax.

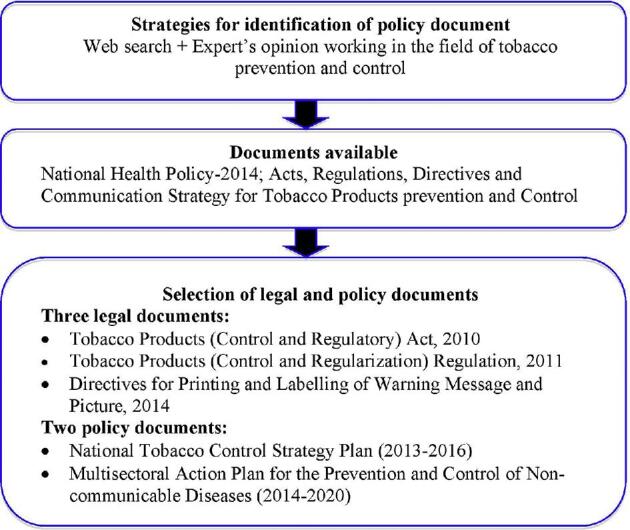

Policy documents identification

The authors identified key anti-tobacco professionals by the duration of their experience working in Nepal. Policy-related documents were identified by searching websites and through personal communication with related experts. Finally, the authors decided to review three legal and two policy documents (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of document review process.

Policy review process

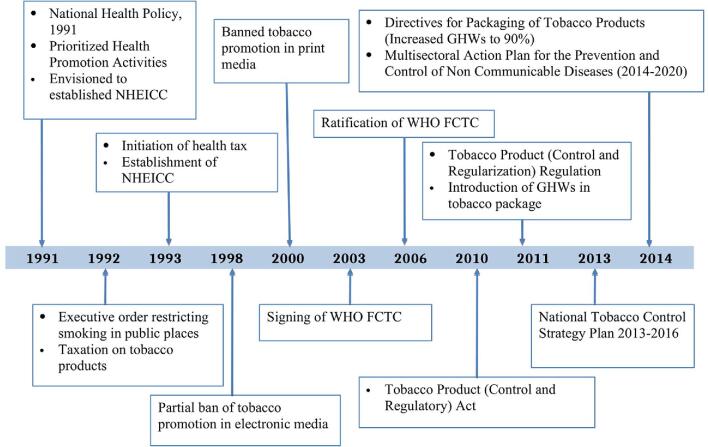

The chronological development of tobacco control policies after 1990 is presented in Figure 3. The Monitor tobacco use and prevention policies, Protect people from tobacco smoke, Offer help to quit tobacco use, Warn about the dangers of tobacco, Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship, and Raise taxes on tobacco (MPOWER) strategy30 was used for analyzing existing tobacco prevention and control policies.

Figure 3.

Major policy milestones on tobacco control and regulation from the 1990s in Nepal.

Results

This review included 32 studies consisting of 23 primary studies and 9 secondary data analyses (Supplementary Table 1). Existing laws and policies on tobacco prevention and control with the associated implementation challenges are presented in Table 1.

The DHS, Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) and STEPS survey were the sources for secondary data analysis. Four studies were multinational while five were national surveys. Most of the studies were conducted at subnational level in cities such as Kathmandu, Pokhara and Dharan among school children or university students. Only seven studies were published from 2000 to 2010. The first authors of eight studies were foreign researchers. Seven studies reported the AOI.

Prevalence and associated factors of tobacco consumption

The prevalence of male smokers aged 15–49 y declined from 32.5% to 27.2% while that of females decreased from 19.6% to 8.4% from 2006 to 2016.10,31 However, the prevalence of using any form of tobacco (smoking or SLT) in males has remained steady for a decade.7 The increment in consumption of SLT among males from 38.2% to 40.1% is attributed to the substitution of tobacco with SLT during the last decade.10,31

Gender

Twenty studies reported a high prevalence of smoking4,7,15,16,19–23,32–42 as well as consumption of SLT among males. Males were three times more likely to smoke than females.15,22,37

Age

Sixteen studies4,7,15–18,20,22,23,32,35,36,40,43–46 reported a significant association of tobacco consumption with increasing age. A recent study shows that males aged 45–49 y were fivefold more likely to use tobacco compared with males aged 15–19 y.7 Also, males aged 45–69 y were almost twofold more likely to smoke compared with males aged 15–29 y.15 Females aged 45–69 y were threefold more likely to smoke compared with females aged 15–29 y.18

Education

There is an inverse association of tobacco use with educational level.4,7,15–18,42–45,47,48 For instance, uneducated people were sixfold more likely to use tobacco and threefold more likely to chew SLT compared with those who had undergone higher education.4 Also, educated men were more than three times less likely to use any form of tobacco compared with their illiterate counterparts.17 Women with a school education were less likely to smoke compared with those without formal education.18

Marital status

The married population showed both a positive16,17,43,44 as well as a negative4,46 association with tobacco consumption. Some studies reported a higher smoking rate among divorced groups compared with married or single populations, while there were also instances where no such associations were reported.15

Socioeconomic status

Families on a low income were more likely to smoke compared with richer families.4,7,16,17,19,44 Also, prevalence was higher among students with better household assets,20 those with extravagant parents36 and those living in substandard accommodation.49

Place of residence

Tobacco consumption was higher among people living in rural compared with urban areas4,16,18,44 and those living in the hills compared with the southern plain.15,18 Also, males from the southern plain were more likely to use SLT compared with other regions.7,17

AOI and its factors

This review showed that tobacco consumption starts in the adolescent age groups. The mean AOI of tobacco consumption was 10.2 y among youths,40 18.6 y among medical students,50 15 y among rural women43 and 13.8 y among adolescents.36 The mean AOI was lower among students compared with the general population. Also, peer influences19–23,38,40,42 and parental smoking19,20,22,23,47,51 were associated with tobacco initiation. However, parental smoking did not show any such association in some other studies.40,43,52,53

Policies on prevention and control of tobacco

Before 1990: priority to increase production

The governmental priority before 1990 was to increase the production of tobacco to fulfill national demand.54 For instance, Janakpur Cigarette Factory was established in 1959. Furthermore, the Tobacco Development Board was established to increase the productivity of tobacco.54

1990–2000: prevention and control measures

Health education and promotional activities for the prevention and control of tobacco consumption were prioritized in the 1990s (Figure 3). The 1991 National Health Policy was envisioned to establish the National Health Education, Information and Communication Centre (NHEICC) under the Ministry of Health and Population. The NHEICC aimed to conduct health promotional activities, including publicizing the hazardous effects of tobacco consumption. Consequently, smoking was banned in public places in 1992.54 The annual budget in 1993 levied a health tax of 1 paisa (about 1/100 US cents) per stick, which was doubled in the next year. Three-quarters of this tax was used to establish a cancer hospital while the remaining funds were used for preventive and public awareness activities.54 Also, advertisements on both electronic (radio and television until 22:00 h)54 and print media were banned in 1998 and 2000, respectively.55

After 2000: reduction of demand and supply as guided by WHO-FCTC

Nepal signed the WHO-FCTC on 3 December 2003 and ratified it on 7 November 2006.25 This created a legal obligation to formulate and implement tobacco control plans, policy strategies and programs.27 As per the 1990 Treaty Act,56 the provisions under this convention were enforceable as Nepalese laws unless separate laws were formed. However, several suits were filed in the court after the government procrastinated in formulating separate tobacco laws as per the convention. Consequently, upon hearing the case of Parasmadi Pradhan vs The Government of Nepal, in 2007 the supreme court ordered the government to develop legislation according to the thrust of the WHO-FCTC.57 Despite this, tobacco laws were only endorsed after 4 y of ratification.

Existing laws and policies on tobacco prevention and control

Existing policies and laws for tobacco prevention and control in Nepal are: (1) the Tobacco Products (Control and Regulatory) Act 201058; (2) Tobacco Products (Control and Regularisation) Regulation 201159; (3) a directive concerning the printing and labeling of the warning message and picture on the box, packet, wrapper, carton, parcel and packaging of tobacco products (amended in 2011)60 and the National Tobacco Control Strategic Plan 2013–201661; and (4) the Multi-sectoral Action Plan for Prevention and Control of NCDs (2014–2020).62

Tobacco Products (Control and Regulatory) Act, 2010

The four items of the Act58 are price measures (demand reduction through price increment and taxation), non-price measures (protection from exposure; regulation of contents, disclosures, packaging and labeling; health education and a communication ban on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship [TAPS]), demand reduction (tobacco cessation activities) and supply reduction activities (prohibiting sales to pregnant women and minors).

Tobacco Products (Control and Regularisation) Regulation, 2011

This regulation59 delineates the Act by describing the provisions and criteria of designated tobacco-consuming areas, the message for tobacco packages, package size, procedures for changing warning messages and graphics, the obligations of vendors, responsibilities of an inspector and allocation of the health fund.

The directive for printing, labeling and packaging of tobacco products, 2011

This directive60 was framed to direct tobacco industries to print and indicate clear and visible pictorial health warnings (PHWs) message and colorful pictures are different things to demonstrate the hazardous effects of tobacco consumption. After the amendment, at least 90% of the total outer portion should be covered with the picture.

National tobacco control strategic plan, 2013–2016

The strategic plan61 was formulated to strengthen the effective implementation of prevailing legislative measures. Its aims are to conduct surveillance alongside epidemiological and economic studies into tobacco control. It also includes plans to protect people from tobacco use through interventions like tobacco-cessation activities, product packaging and labeling, banning of TAPS, increasing taxation and behavioral changes. Finally, its other aims are to reduce supply by prohibiting sales to pregnant women and minors and displaying tobacco restriction signs in public places.

Multi-sectoral action plan for prevention and control of NCDs, 2014–2020

The plan62 aims to reduce preventable morbidity and premature mortality due to NCDs. It aims to reduce the relative prevalence of current tobacco use among a population aged ≥15 y by 30% (by 2025) through strengthening enforcement and compliance to existing acts and regulations.

The legal (mandatory) and policy (guiding) interventions—that are in line with the MPOWER framework—to reduce tobacco consumption and associated implementation challenges are described in Table 1.

Discussion

This review revealed various factors behind tobacco consumption. Males were more likely to consume tobacco than females. These findings were consistent with global1 as well as South Asian studies.63 The higher prevalence of smoking among males might be due to its cultural acceptance as a masculine behavior.37 Furthermore, under-reporting among female consumers might be another factor.7 Steady prevalence among males and a declining pattern among females7 are inconsistent with the global trend, which shows a declining trend among both genders.1 This might be due to weak enforcement of tobacco laws or substitutions towards SLT. Almost one-tenth of Nepalese school children (9.4%) used tobacco, which was greater than for their Sri Lanka (9.1%) and Bangladesh (6.9%) counterparts.40 This might be due to inadequate interventions for tobacco prevention and control targeting the younger generations.

A higher prevalence of smoking in rural rather than urban areas4,7,16,18,44 might be due to limited access regarding the hazardous effects of smoking.18 Likewise, a higher consumption in the mountains compared with the southern plains4,15,18 might be due to cold weather. Furthermore, increasing the trend of substituting smoking with SLT in the southern plain might be another factor behind this.7,17 Different forms of SLT, like jarda, gutka, paan masala, double mazza and paan, are readily available in the southern plain. The ubiquitous and socially acceptable nature of SLT compared with cigarettes16,17,64 might be another factor for the soaring consumption of SLT.

The inverse relationship of education and wealth with tobacco consumption was consistent with studies from Bangladesh,65 Pakistan66 and India.67 Likewise, discussing the detrimental effects of tobacco among students and mothers' groups40 reduces its consumption. This suggests health awareness interventions are effective among high-risk groups.40,66 The studies from Bangladesh68 and India69 showed higher odds of tobacco consumption among widows and divorced/separated groups. However, this review did not show such an association consistently.

The consumption of tobacco starts during adolescence.21,43,51 This initiation is influenced by peer pressure19–23,38,40,42 and family environment.19,20,22,23,47,51 A congruent association was reported from Pakistan.70

Tobacco prevention and control policies

SDG targets are to reduce the prevalence of tobacco consumption from 30.8% to 15% from 2015 to 2030.29 WHO FCTC and the MPOWER measures71 are guiding policy documents for tobacco control and prevention in Nepal. Even after a decade of robust anti-tobacco policies26 prevalence remains high,7 which indicates the frangible implementation of such policies. There are several behavioral and economic intervention challenges associated with it. Behavioral challenges are primarily warnings, monitoring and cessation programs, while taxation, marketing and the supply of tobacco products are the tobacconomics challenges.

Issues with taxation

Raising the tax on tobacco products is the most effective demand-reduction policy tool in tobacco control.2,72,73 Studies in India,74,75 Bangladesh76,77 and other Asian countries78 have shown price sensitivity among tobacco users. WHO recommends a 75% share of total tax in the retail price,79 which was just 28% in Nepal in 2014. This is one of the lowest among Asian countries.71 The affordability of tobacco products has not changed in the last decade, resulting in a nominal decline in tobacco consumption.80 Hand-made tobacco products, consumed by 14% of consumers,13 are beyond taxation. Furthermore, people have substituted SLT products76,81 after taxation increments on cigarette items. Finally, tobacco industries have increased their influence to withstand taxation policies due to their significant contribution to the national economy.

Implementation of bans on TAPS

Both the FCTC79 and Tobacco Products (Control and Regulatory) Act focus on a comprehensive ban on TAPS. This includes a restriction to advertise, promote or sponsor any tobacco product through any form of media.58 This further restricts transactions of tobacco products in public places58; however, there is weak enforcement despite the strict restrictions. Purchasing a single unit/packet is one of the drivers of cigarette smoking.82 Although the law prohibits selling a single unit of a cigarette, no penalties have been enforced.7 Instead, mini-packs (10 sticks) are available in the market these days instead of 20-stick pack.59

Interventions related to PHWs

Seventy-seven out of 181 countries have successfully implemented PHWs on tobacco products.83 Nepal has provision for one of the largest PHWs in the world84 after it increased the size from 75% to 90% in any form of packages.60 These warnings are frequently changed by the Ministry.58 Despite some good progress in the implementation of PHWs in Nepal,84 similar interventions in Vietnam85 and India86 were ineffective in reducing tobacco consumption.

Tobacco industries, through at least five petitions, opposed introducing PHWs on tobacco packages. Coverage of 75% PHWs was only possible after the judicial order rejecting those petitions. The court interpreted the laws and elucidated that the provision of 75% PHWs was neither unconstitutional87 nor against the provision of FCTC (at least 30% area coverage) as argued by tobacco industries.24 After this abortive attempt, the industries have started to violate the regulation indirectly by covering tobacco products' PHWs with value-added tax (VAT) stickers.7 Such weak legal enforcement portends the challenges of plain packaging proposed for the future.7

Promoting tobacco-cessation programs

The Act has envisioned a committee whose role—although neglected—is to provide support to quit tobacco.58 There are no toll-free quit-line/helpline numbers to telephone to discuss cessation.80 Cessation support is available in very few hospitals or clinics. Similarly, the primary healthcare system has a limited number of tobacco-cessation programs.

Passive smoking and smoking in public places

There are policies for creating a smoke-free environment in public places, including penalty provisions for any misdoing. However, there is poor compliance7 due to weak institutionalization. There is no restriction on smoking in public places like restaurants, schools/campuses or even on public transport. Multi-sectoral coordination between security, industry, finance, agriculture, health education and communication is challenging.

Monitoring of tobacco control, prevention and regulation policies

The STEPS, DHS and GYTS surveys25,80 are used to monitor prevalence at the national level. The prevalence and correlates of smoking have also been reported by other small-scaled studies. Furthermore, organizational and functional structures, which employ inspectors and committees, are not sufficiently effective in performing their designated monitoring roles.

Implications and policy recommendations

Premature deaths from NCDs constitute more than 43.7% of all deaths in Nepal.29 High OOP expenditure (55%) is associated with tobacco-related diseases.29 Expensive treatment followed by poor health insurance coverage29 has further impoverished the population. Hence, reduction of consumption is the most effective strategy with which to prevent the soaring burden of NCDs and the unaffordable cost of treatment.

Focus programs on high-risk current tobacco users

Tobacco initiation during adolescence suggests that cessation interventions should be targeted at schools. Furthermore, habitual withdrawal difficulties after getting habitual52,88 indicate the effectiveness of such interventions among the adolescent population. Increasing SLT consumption among males in recent years10,31 signifies that future interventions should be focused on SLT products.

Evidence shows that adolescents, males, the poor, the uneducated and people living in rural areas are at a higher risk and that adolescents and the peers/siblings of smokers are at a greater risk of starting smoking. Hence, it is of paramount importance to design targeted interventions such as peer education groups and to initiate discussions at schools, colleges and youth clubs. Furthermore, social media might be another way of reaching adolescents. Radio programs, street drama and quit-line support campaigns can reach all the targeted groups.

Increase the tax on and prices of tobacco products

The key to taxation policy lies in increasing taxation, as recommended by WHO. Local governments can impose tax at the source of production. This could also bring hand-made products into the taxation system, which has not been done previously. Furthermore, periodic evaluations of the tax level and reduction of the multi-tier tax structure to a minimal tier are essential. These measures would help to minimize price variation and possible substitution towards cheaper products.79 Finally, the provision of a 25% fund to be used for prevention and research activities should be increased.

Integration in routine health programs

Tobacco-cessation programs could be expanded by integrating them into routine primary healthcare.7 This could be accomplished through different approaches, including providing training to health workers, incorporating tobacco dependence treatment in curricula, special programs designed for the adolescent population and promoting tobacco cessation in the workplace and public places.

Expand the jurisdiction of local government

Local governments can exercise their legal authority to formulate, implement and regulate policies, laws and guidelines related to tobacco control as provided by the Local Government Operation Act.89 Considering poor policy compliance, we suggest expanding the jurisdiction of local government. This could be started by devolving the authority of the 'Inspector' and the 'Committee for Control and Regulations of Tobacco Products' granted by the Act to local governments. This would ensure revenue collection, progress monitoring, compliance and an effective ban on TAPS. Furthermore, it would overcome policy implementation challenges like the ambiguity of responsibilities and poor coordination mechanisms among concerned stakeholders.

Develop a monitoring mechanism

Strict legal implementation can bring behavioral changes. For instance, linking tobacco consumption with the paradigm of masculinity and cultural acceptance can only be minimized if existing laws are implemented effectively. This requires integrated efforts from individuals, communities, civil society and the local government. Effective policy compliance mechanisms, namely, banning consumption and sale around public places, enforcing the legal age and non-pregnancy status for purchasing, shops’ licensing, prohibiting single-unit sales/purchases, intentional flouting of the law by tobacco industries and attracting consumers through mini-packs, should be monitored effectively.

Also, almost one-eighth of tobacco users13 consume homemade products like hand-rolled cigarettes, tobacco pipes, cigars, cheroots, cigarillos and shisha. These consumers are neither affected by taxation nor by PHWs. Thus we suggest a regulatory mechanism at the local level. This mechanism can restrict production and consumption as well as ensuring the effective implementation of policies.

There are some limitations to this study. It provides a narrative summary of the evidence. Quality grading was not possible, rendering a meta-analysis unfeasible. Furthermore, the subtle definition of tobacco consumption was quite difficult. Some defined it as those who had smoked in the past 30 d15,18 while others have not imposed such a time limitation.4,7,16,17,44

Conclusion

Higher prevalence of tobacco consumption among males, the illiterate, the poor, older people and those living in a rural area illuminates the target groups that need to be targeted when designing and implementing tobacco control interventions. The influence of peer pressure and family environment in tobacco initiation indicates that tobacco prevention activities should start in schools. Nepalese tobacco-control policies are in line with WHO-FCTC and MPOWER strategies; however, there are various associated implementation challenges. Increasing the tax base and amount, effective implementation of a ban on TAPS, counseling and support for tobacco cessation are equally important along with PHWs. The federal structure and expansion of the jurisdiction of local government could be windows of opportunity to address current weak policy and regulation compliance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Manish Gautam for his assistance in proofreading this paper.

Contributor Information

Geha Nath Khanal, Save the Children, Shambhu Marg, Sinamangal, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Resham Bahadur Khatri, Center for Research and Development, Surkhet, Nepal; School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

Authors’ contributions

Both GNK and RBK contributed equally to this work. GNK wrote the first draft of the paper. RBK participated in the policy analysis process and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Both the authors agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Reithsma MB, Fullman N, Ng Met al. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990– 2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eriksen M, Whitney C. Risk Factors: Tobacco. In: McQueen David V, editor Global Handbook of Noncommunicable Diseases. Health Promotion. New York, Springer New York, 2013. p. 115–36. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reddy KS, Yadav A, Arora Met al. Integrating tobacco control into health and development agendas. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sreeramareddy CT, Ramakrishnareddy N, Harsha Kumar Het al. Prevalence, distribution and correlates of tobacco smoking and chewing in Nepal: a secondary data analysis of Nepal Demographic and Health Survey-2006. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2011; 6(33):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization Global Status Report on Non-Communicable Diseases 2014. World Health Organization, Gevena, Switzerland, 2014.. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Forouzanfar MH, Afshin A, Alexander LTet al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1659–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shrestha N, Mehata S, Pradhan Pet al. A nationally representative study on socio-demographic and geographic correlates, and trends in tobacco use in Nepal. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization The fatal link between tobacco and cardiovascular diseases in the WHO South-East Asia Region. Regional Office of South-East Asia, New Delhi, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mishra SR, Neupane D, Bhandari PMet al. Burgeoning burden of non-communicable diseases in Nepal: a scoping review. Global Health. 2015;11(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) Nepal, New ERA, ICF International Inc Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2006. Kathmandu, Nepal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pradhan A, Aryal RH, Regmi Get al. Nepal Family Health Survey 1996. Kathmandu, Nepal, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP), Society for Local Integrated Development Nepal (SOLID) Nepal), World Health Organization WHO STEPS Surveillance: Non-Communicable Disease Risk Factors Survey, 2008. Kathmandu, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aryal K, Neupane S, Mehata Set al. Non Communicable Diseases Risk Factors: STEPS Survey Nepal 2013. Kathmandu, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Smoking 2000–2025, Second edition Geneva, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aryal KK, Mehata S, Neupane Set al. The burden and determinants of non communicable diseases risk factors in Nepal: findings from a nationwide STEPS survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sreeramareddy CT, Pradhan P, Mir IAet al. Smoking and smokeless tobacco use in nine South and Southeast Asian countries: prevalence estimates and social determinants from Demographic and Health Surveys. Popul Health Metr. 2014;12(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khanal V, Adhikari M, Karki S. Social determinants of tobacco consumption among Nepalese men: findings from Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bista B, Mehata S, Aryal KKet al. Socio-demographic predictors of tobacco use among women of Nepal: evidence from non communicable disease risk factors STEPS survey Nepal 2013. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2015;13(29):14–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bhaskar RK, Sah MN, Gaurav Ket al. Prevalence and correlates of tobacco use among adolescents in the schools of Kalaiya, Nepal: a cross-sectional questionnaire based study. Tob Induc Dis. 2016; 14(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sreeramareddy CT, Kishore P, Paudel Jet al. Prevalence and correlates of tobacco use amongst junior collegiates in twin cities of western Nepal: a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:97 10.1186/1471-2458-8-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jha N, Subba B. Prevalence of tobacco use among college students of dharan, eastern Nepal. Nepal J Sci Technol. 2002;4:107–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Binu VS, Subba SH, Menezes RGet al. Smoking among Nepali youth- Prevalence and predictors. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(1):221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aryal UR, Bhatta DN. Smoking Susceptibility and Intention to Smoke among Secondary School Adolescents in Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2015;13(1):26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nepal Kanoon Patrika D 9120 Surya Nepal Pvt Ltd, et al. V. Government of Nepal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Government of Nepal Brief Profile on Tobacco Control in Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Awale S In a Puff of Smoke. Nepali Times; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organization WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thapa R, Bam K, Tiwari Pet al. Implementing federalism in the health system of Nepal: Opportunities and challenges. Int J Heal Policy Manag. 2019;8(4):195–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Government of Nepal Nepal Sustainable Development Goals Status and Roadmap: 2016–2030. Kathmandu, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2013: Enforcing Bans on Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship, vol. 5 World Health Organization, Gevena, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ministry of Health, New ERA, ICF Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adhikari K, Gupta N, Koshy AK. Gender differences on risk factors of Non-Communicable Diseases-A community based cross-sectional study in Central Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2014;12(27):88–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aryal UR, Lohani SP. Perceived risk of cigarette smoking among college students. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2011;9(19):176–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sreeramareddy CT, Suri S, Menezes RGet al. Self-reported tobacco smoking practices among medical students and their perceptions towards training about tobacco smoking in medical curricula: a cross-sectional, questionnaire survey in Malaysia, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2010;5(1). 10.1186/1747-597X-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sinha DN, Rizwan SA, Aryal KKet al. Trends of smokeless tobacco use among adults (aged 15–49 Years) in Bangladesh, India and Nepal. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(15):6561–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pradhan PMS, Niraula SR, Ghimire Aet al. Tobacco use and associated factors among adolescent students in Dharan, Eastern Nepal: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002123 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shakya A, Mishra SR, Giri Set al. Gender differences and clustering of modifiable risk factors of non-communicable diseases among medical students: a cross sectional study in Nepal. J Community Health. 2015;40(1):147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pokhrel BR, Thankappan KR, Mini GKet al. Tobacco use among health professionals and their role in tobacco cessation in Nepal. Prev Control. 2006;2:117–25. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Karmacharya B, Shrestha A, Al Fet al. Prevalence and correlates of tobacco use in a suburban community of Nepal: findings from the Dhulikhel Heart Study. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2017;60(4):341–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kabir MA, Goh K-L, Khan MH. A cross-country comparison of tobacco consumption among youths from selected South-Asian countries. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:379 10.1186/1471-2458-13-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aryal U, Bhatta D. Perceived benefits and health risks of cigarette smoking among young adults: insights from a cross-sectional study. Tob Induc Dis. 2015;13:22 doi: 10.1186/s12971-015-0044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sah R, Pradhan B, Subedi Let al. Epidemiological study of tobacco smoking behaviour amongst residents of the Hill Region of Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2016;55(3):215–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Khatri RB, Mishra SR, Khanal V. Tobacco use among rural Nepalese women: Cross-sectional community based study. Indian J Cancer. 2015;52(4):699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sinha DN, Suliankatchi RA, Amarchand Ret al. Prevalence and sociodemographic determinants of any tobacco use and dual use in six countries of the WHO South-East Asia Region: findings from the demographic and health surveys. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):750–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pandey S, Lin Y. Tobacco use among married women in Nepal: The role of women's empowerment. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(3):530–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Niraula SR Tobacco use among women in Dharan, Eastern Nepal. J Heal Popul Nutr. 2004;22(1):68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barakoti R, Ghimire A, Pandey ARet al. Tobacco use during pregnancy and its associated factors in a mountain district of Eastern Nepal: a cross-sectional Questionnaire survey. Front Public Heal. 2017;5:129 Doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Singh JK, Acharya D, Kadel Ret al. Factors associated with smokeless tobacco use among pregnant women in rural areas of the Southern Terai, Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2017;14(3):12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Oli N, Vaidya A, Thapa G. Behavioural risk factors of non-communicable diseases among Nepalese urban poor: a descriptive study from a slum area of Kathmandu. Epidemiol Res Int. 2013;2013:113 doi: 10.1155/2013/329156. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mishra SR, Neupane D, Shakya Aet al. Modifiable risk factors for major non-communicable diseases among medical students in Nepal. J Community Health. 2015;40:863–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ghimire A, Sharma B, Niraula SRet al. Smoking habit among male medical and dental students of B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2013;11(41):32–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pradhan PMS, Marahatta K. Cross-sectional survey on quitting attempts among adolescent smokers in Dharan, Eastern Nepal. J Addict. 2016;2016:1–5. 10.1155/2016/6859291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pradhan PMS, Kalra S. Factors associated with tobacco use among female adolescent students in Dharan municipality of Eastern Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2015;13(3):220–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Government of Nepal The National Anti-Tobacco Communication Campaign Strategy for Nepal. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mahato PK Current tobacco control policies in Nepal: Existing gaps and way forward. J Heal Allied Sci. 2012;2(1):70–3. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Government of Nepal Nepal Treaty Act, 1990. Nepal, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nepal Kanoon Patrika D 8217 Homlal Shrestha V. Interim Parliament. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Government of Nepal Tobacco Product (Control and Regulatory) Act, 2011 (Unofficial Translation). Nepal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ministry of Health and Population Tobacco Products (Control and Regularisation) Regulation, 2011. Kathmandu, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ministry of Health and Population Directive for Printing and Labeling of Warning Message and Picture on the Box, Packet, Wrapper, Carton, Parcel and Packaging of Tobacco Product–2014. Kathmandu, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Government of Nepal National Tobacco Control Strategic Plan (2013–2016). Kathmandu, Nepal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Government of Nepal Multisectoral Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non Communicable Diseases (2014–2020). Kathmandu, Nepal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Glenn BA, Surani Z, Chawla Net al. Tobacco use among South Asians: results of a community-university collaborative study. Ethn Health. 2009;14(2):131–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sinha DN, Bajracharya B, Khadka BBet al. Smokeless tobacco use in Nepal. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49(4):352–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Palipudi KM, Sinha DN, Choudhury Set al. Predictors of tobacco smoking and smokeless tobacco use among adults in Bangladesh. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49(4):387–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Masud H, Oyebode O. Inequalities in smoking prevalence: a missed opportunity for tobacco control in Pakistan. J Public Health. 2017;40(2):271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rani M, Bonu S, Jha Pet al. Tobacco use in India: prevalence and predictors of smoking and chewing in a national cross sectional household survey. Tob Control. 2003;12(e4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mia MN, Hanifi SMA, Rahman MSet al. Prevalence, pattern and sociodemographic differentials in smokeless tobacco consumption in Bangladesh: evidence from a population-based cross-sectional study in Chakaria. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e012765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Subramanian SV, Nandy S, Kelly Met al. Patterns and distribution of tobacco consumption in India: cross sectional multilevel evidence from the 1998–9 national family health survey. BMJ. 2004; 328(7443):801–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rozi S, Mahmud S, Lancaster Get al. Peer pressure and family smoking habits influence smoking uptake in teenage boys attending school: multilevel modeling of survey data. Open J Epidemiol. 2016;6:167–72. [Google Scholar]

- 71. World Health Organization WHO Report on Global Epidemic, 2017: Monitoring Tobacco use and Prevention Policies. Geneva, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 72. World Health Organization Tobacco and poverty: a vicious circle. Geneva, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Golden SD, Smith MH, Feighery ECet al. Beyond excise taxes: a systematic review of literature on non-tax policy approaches to raising tobacco product prices. Tob Control. 2016;25:377–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Joseph RA, Chaloupka FJ. The influence of prices on youth tobacco use in India. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(January):S24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Shang C, Chaloupka FJ, Fong GTet al. The association between state value-added taxes and tobacco use in India—Evidence from GATS and TCP India survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(11):1344–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nargis N, Hussain A, Fong G. Smokeless tobacco product price and taxation in Bangladesh: Findings from International Tobacco Control Survey. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51(Suppl S1):33–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Nargis N, Ruthbah UH, Hussain AKMGet al. The price sensitivity of cigarette consumption in Bangladesh: evidence from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Bangladesh Wave 1 (2009) and Wave 2 (2010) Surveys. Tob Control. 2014;23(Suppl 1):i39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ho L, Schafferer C, Lee Jet al. Raising cigarette excise tax to reduce consumption in low-and middle-income countries of the Asia-Pacific region: a simulation of the anticipated health and taxation revenues impacts. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1187 10.1186/s12889-018-6096-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. World Health Organization WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2015: Raising Tax on Tobacco. Geneva, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 80. World Health Organization WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2017 Country Profile: Nepal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Selvaraj S, Srivastava S, Karan A. Price elasticity of tobacco products among economic classes in India, 2011–2012. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e008180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lal P, Kumar R, Ray Set al. The single cigarette economy in India - a Back of the envelope survey to estimate its magnitude. Asia Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:5579–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. World Health Organization 2018 Global Progress Report on Implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Yadav A, Nazar GP, Rawal Tet al. Plain packaging of tobacco products: the logical next step for tobacco control policy in India. BMJ Glob Heal. 2018;3:e000873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Van Minh H, Ngan TT, Mai VQet al. Tobacco control policies in vietnam: review on MPOWER implementation progress and challenges. Asia Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sindhuri R, Dongre A. Intention to quit tobacco and perceptions about enhanced pictorial warnings on tobacco products among male college students in puducherry-mixed methods study. Online J Heal Allied Sci. 2017;16(4):4. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Yadav A, Singh A, Khadka BBet al. Smokeless tobacco control: Litigation & judicial measures from Southeast Asia. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148(1):25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Larabie LC To what extent do smokers plan quit attempts? Tob Control. 2005;14:425–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Government of Nepal Local Government Operation Act, 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.