Abstract

Background:

Several glucagon-like peptide agonists (GLP-1RA) and sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) have demonstrated cardiovascular benefit in type 2 diabetes in large randomized controlled trials in patients with established cardiovascular disease or multiple risk factors. However, few trial participants were on both agents and it remains unknown whether the addition of SGLT2i to GLP-1RA therapy has further cardiovascular benefits.

Methods:

Patients adding either SGLT2i or sulfonylureas to baseline GLP-1RA were identified within 3 US claims datasets (2013–2018) and were 1:1 propensity score matched (PSM) adjusting for >95 baseline covariates. The primary outcomes were 1) composite cardiovascular endpoint (CCE; comprised of myocardial infarction, stroke, and all-cause mortality) and 2) heart failure hospitalization. Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated in each dataset and pooled via fixed-effects meta-analysis.

Results:

Among 12,584 propensity-score matched pairs (mean [SD] age 58.3 [10.9] year; male (48.2%)) across the 3 datasets, there were 107 CCE events [incidence rate per 1,000 person-years (IR) = 9.9; 95% CI: 8.1, 11.9] among SGLT2i initiators compared to 129 events [IR = 13.0; 95% CI: 10.9, 15.3] among sulfonylurea initiators corresponding to an adjusted pooled HR of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.59, 0.98); this decrease in CCE was driven by numerical decreases in the risk of MI (HR 0.71, 95% CI: 0.51, 1.003) and all-cause mortality (HR 0.68, 95% CI: 0.40, 1.14) but not stroke (HR 1.05, 95% CI: 0.62, 1.79). For the outcome of heart failure hospitalization, there were 141 events [IR = 13.0; 95% CI: 11.0, 15.2] among SGLT2i initiators versus 206 [IR = 20.8; 95% CI: 18.1, 23.8] events among sulfonylurea initiators corresponding to an adjusted pooled HR of 0.65 (95% CI: 0.50, 0.82).

Conclusions :

Risk of residual confounding cannot be fully excluded. Individual therapeutic agents within each class may have different magnitudes of effect. In this large real-world cohort of diabetic patients already on GLP-1RA, addition of SGLT2i – compared to addition of sulfonylurea – conferred greater cardiovascular benefit. The magnitude of the cardiovascular risk reduction was comparable to the benefit seen in cardiovascular outcome trials of SGLT2i versus placebo where baseline GLP-1RA use was minimal.

Keywords: Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, cardiovascular outcomes, major adverse cardiovascular events, heart failure, stroke, myocardial infarction, cardiovascular death

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and heart failure (HF) are the primary contributors to mortality and morbidity among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM); therefore, reducing these events is the cornerstone of disease management.1 Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) are a newer class of medications that lower serum glucose by inhibiting its reabsorption in the proximal convoluted tubule.2 In several large randomized cardiovascular outcome trials, SGLT2i have demonstrated their efficacy in reducing HF hospitalizations3–5 and, for empagliflozin and canagliflozin, the composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke.3, 5 Of note, reductions in cardiovascular events occurred early following randomization, often within the first six months of SGLT2i therapy initiation, prior to anticipated times when change would occur in the underlying coronary atherosclerotic burden.

There is growing interest in use of SGLT2i in conjunction with other therapies with established cardiovascular benefits – most notably, glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1RA), where several within class agents (liraglutide, dulaglutide and semaglutide) have demonstrated benefit on the composite of cardiovascular death, MI and stroke.6–8 The putative mechanisms by which SGLT2i and GLP-1RA exert their cardiovascular benefit appear to be complementary in nature based on the orthogonal molecular mechanisms of action and the different time courses over which improved cardiovascular outcomes are manifest in the trials. However, the combined use of these two drug-classes in cardiovascular outcome trials was rare. The prevalence of baseline SGLT2i in GLP-1RA related cardiovascular trials ranged from no-use (several trials finished patient recruitment before SGLT2i became available) to 5.3%; likewise, prevalence of GLP-1RA use in SGLT2i related cardiovascular trials ranged from 2.5% to 4.4%.3–5

To assess whether the addition of SGLT2i to GLP-1RA reduced cardiovascular events compared to GLP-1RA alone, we utilized three US-based insurance claims datasets to identify a cohort of diabetic patients adding SGLT2i to their baseline GLP-1RA therapy compared to patients adding sulfonylureas. Sulfonylureas were used as the comparator group because they are not associated with a cardiovascular benefit, can be used in conjunction with GLP-1RA (unlike dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors) and are more widely prescribed in clinical practice compared to other glucose lowering therapies such as thiazolidinediones or alpha-glucosidase inhibitors. We hypothesized that given their orthogonal pharmacodynamic effects on cardiovascular risk, adding SGLT2i to existing GLP-1RA therapy would result in greater reductions in cardiovascular events compared to the addition of agents without established cardiovascular benefits.

METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article [and its online supplementary files].

Data Sources

Data were collected from three US-based insurance claims databases. Two were commercial claims databases generalizable to approximately 50% of the US population enrolled in an employer-based insurance program: Optum Clinformatics Data Mart Database (April 2013 – June 2018) and IBM MarketScan (April 2013 – December 2017). Further, the Medicare components of Optum provide data for patients enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, and MarketScan for patients enrolled in supplemental Medicare plans. The third data source was Medicare fee-for-service data (Parts A/B/D April 2013 – December 2016) comprised of all patients over 65 years with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. For each study participant, the data source included information on patient demographics, medical- and pharmacy- enrollment status, inpatient and outpatient medical service utilization, and outpatient pharmacy dispensing information.

The study was approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Institutional Board Review Board and the appropriate data use agreements were in place for all databases.

Study population and exposure definition

Within each database, we identified a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes initiating an SGLT2i (canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, or empagliflozin; exposure group) or a second-generation sulfonylurea (glipizide, glyburide, glimepiride; active comparator group; hereby referred to as “sulfonylureas”) without evidence of prior use of either of the two classes in the 6-month period prior to the date of cohort entry (defined as date of SGLT2i or sulfonylurea initiation). Patients were required to have previously filled a prescription for a GLP-1RA therapy (exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, albiglutide, dulaglutide or semaglutide) with the days supply sufficient to overlap the cohort entry date when the initial SGLT2i or sulfonylurea prescription was filled. Patients younger than 18 (or 65 in Medicare fee-for-service), or those with evidence of gestational or type I diabetes, cancer, end-stage renal disease, or human immunodeficiency virus, nursing home admission, or hospice care were excluded from analysis (see Figure I in the supplement for study design).

Baseline Covariates

We assessed more than 95 baseline covariates that were measured in the 6-month period prior to and including the day of cohort entry. These covariates included demographics and calendar time (e.g. age, sex and calendar year of cohort entry), complications of diabetes (e.g. diabetic-neuropathy, nephropathy, retinopathy), oral and injectable antidiabetic therapy (e.g. metformin, insulin, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors), cardiovascular conditions (e.g. myocardial infarction, stroke, HF), cardiovascular medications (e.g. dispensing of beta-blockers, loop diuretics, statins), non-cardiovascular comorbid conditions (e.g. diagnosis of chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, psychiatric conditions), non-cardiovascular medications (e.g. dispensing of anticonvulsants, antidepressants), and measures of burden of comorbidities and healthcare utilization (e.g. combined comorbid index,9 number of hospitalizations, number of medications). Hemoglobin A1c (available for subset of patients in MarketScan and Optum data but not in Medicare; not included in the propensity score) was utilized to assess the presence of adequate therapeutic equipoise between the SGLT2 and sulfonylurea arms prior to propensity score matching and to assess potential residual confounding after propensity score matching. There was no other missing data in our study.

Follow up and study endpoints

Separately for each study outcome, patients began contributing to follow-up time on the day after cohort entry up until the first occurrence of one of the following: end of pharmacy or healthcare eligibility, medication discontinuation defined as 60-day gap in therapy of either SGLT2i (among SGLT2i initiators), sulfonylureas (among sulfonylurea initiators) or GLP-1RA (among both groups), medication switching or augmentation (patients in SGLT2i arm initiating sulfonylureas and vice versa), end of study data (December 2016 for Medicare, December 2017 for MarketScan and June 2018 for Optum) or the occurrence of that outcome.

The two primary outcomes of interest were 1) a composite cardiovascular endpoint comprised of MI hospitalization, stroke hospitalization, or all-cause mortality, and 2) HF hospitalizations (see Table I in the supplement for outcome definitions). Analysis of each of the two primary outcomes was conducted independently of the other. In prior validation studies, the positive predictive value of these outcomes was greater than 80%.10–12 Information on mortality was available in Medicare fee-for-service through the vital status file, whereas it was limited to in-hospital deaths in MarketScan. For Optum, mortality data were informed from four sources: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Social Security Administration Master Death Files, in-hospital deaths, and death as a reason for insurance discontinuation.

Primary analyses

To mitigate the risk of confounding, new initiators of SGLT2i were matched to those initiating sulfonylureas on their estimated propensity score which utilized multivariable logistic regression to model the probability of adding a SGLT2i versus adding a sulfonylurea. Variables were included in the model without selection. A greedy-matching approach was used with a maximum caliper width of 0.01 on the propensity score.13 We assessed the performance of propensity scores in confounding control by examining the distribution of the baseline covariates prior and after propensity-score matching by exposure group, utilizing a threshold of 10% in the standardized difference as a metric for a meaningful imbalance.14 Thereafter, using a primary as-treated analysis, where patients were censored on treatment discontinuation or switching, we estimated the rates of the primary composite endpoints among patients exposed to both SGLT2i and GLP-1RA and among patients exposed to both sulfonylureas and GLP-1RA, by calculating the number of outcome events and incidence rates (IR). Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and included exposure status as the independent variable; for non-fatal endpoints, we accounted for the competing risk of death by estimating cause-specific hazard functions.15 Analyses were performed separately in each data source and pooled via inverse-variance fixed effects meta-analysis,16 as random effects pooling performs poorly when applied in the setting of few databases.17 Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to visualize the cumulative incidence of the outcome over time and log-rank tests were used to compare the survival distribution in the two groups. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Sensitivity, subgroup and secondary analysis

Frist, to assess the robustness of the primary findings, we conducted sensitivity analysis pertaining to exposure-related censoring criteria, where instead of censoring patients at the time of treatment switching or discontinuation, we instead carried the index exposure forward to mimic an intention to treat approach. Second, we estimated the average treatment effects using the stabilized inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) based on the propensity score in lieu of the propensity score matching approach.18 Third, we examined the heterogeneity of treatment effect within the subgroups of patients with and without established cardiovascular disease, defined as history of MI, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, HF, coronary atherosclerosis and other forms of chronic ischemic heart disease (including unstable angina), transient ischemic attacks, and peripheral vascular disease. Finally, we restricted our analysis to a subgroup of patients treated with an SGLT2i with proven benefit on MACE (i.e. empagliflozin and canagliflozin) compared to the only sulfonylurea tested for cardiovascular safety in a trial setting (i.e. glimepiride). Within all subgroups, the propensity score was re-estimated, and patients were re-matched on their newly estimated propensity score using the same caliper width as in the primary analysis.

We also examined several secondary outcomes including the individual components of the composite cardiovascular endpoint (MI, stroke, all-cause mortality) and the composite of the two primary outcomes. We also assessed the association with a control outcome with an expected null finding (i.e. administration of the flu vaccination during follow up).

Role of the Funding Source and Patient Involvement

This study was funded by the internal funds of Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. The authors had complete control over design, analysis, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

RESULTS

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we identified a cohort of 32,221 patients who added SGLT2i and 26,894 who added sulfonylureas to existing GLP-1RA therapy. Table 1 shows select pooled baseline characteristics of the cohort prior to and after propensity score matching across the three databases (see Tables II – IV in the supplement for information on all baseline characteristics prior to and after propensity score matching by database; Table V in the supplement lists the clinical characteristics of unmatched patients). Prior to matching, patients in the SGLT2i and sulfonylurea group differed with respect to some baseline characteristics (defined as standardized difference exceeding 10%). Patients in the SGLT2i arm were younger, more obese, and more likely to use insulin and to have diabetes-related complications. Less than 20% of patients in either group had evidence of existing cardiovascular disease. After 1:1 propensity score matching on >95 covariates, there were 25,168 patients, 12,584 in each group; the baseline characteristics were well balanced with no standardized difference exceeding 10%. Hemoglobin A1c values were similar between the two groups even prior to propensity score matching implying good therapeutic equipoise between the SGLT2 and sulfonylureas and remained well-balanced after propensity score matching. The mean [SD] age of the matched cohort was 58.3 [10.0] years and 48.2% were male. Canagliflozin (61.6%), liraglutide (60.3%), and glimepiride (54.9%) were the most commonly used agents within their respective classes (Table VI in the supplement).

Table 1:

Select pooled baseline characteristics prior to and after propensity score matching*

| Prior to matching | After matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2 (n=32,221) | SU (n=26,894) | SMD | SGLT2 (n=12,584) | SU (n=12,584) | SMD | |

| 56.3 (10.6) | 59.1 (10.9) | 26.0 | 58.3 (10.9) | 58.4 (11.1) | 0.9 | |

| Male, n (%) | 16,326 (50.7) | 13,198 (49.1) | 3.2 | 6,079 (48.3) | 6,039 (48.0) | 0.6 |

| Diabetic severity, n (%) | ||||||

| Diabetic neuropathy | 4,754 (14.8) | 3,085 (11.5) | 9.7 | 1,747 (13.9) | 1,686 (13.4) | 1.4 |

| Diabetic retinopathy | 2,285 (7.1) | 1,577 (5.9) | 5.0 | 867 (6.9) | 843 (6.7) | 0.8 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 2,153 (6.7) | 1,786 (6.6) | 0.2 | 938 (7.5) | 926 (7.4) | 0.4 |

| Insulin | 13,515 (41.9) | 5,472 (20.3) | 48.0 | 3,233 (25.7) | 3,148 (25.0) | 1.6 |

| Metformin | 23,679 (73.5) | 18,199 (67.7) | 12.8 | 8,872 (70.5) | 8,850 (70.3) | 0.4 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mean (SD)† | 8.4 (1.7) | 8.4 (1.7) | 0.3 | 8.4 (1.8) | 8.4 (1.7) | 0.4 |

| Cardiovascular characteristics, n (%) | ||||||

| Cardiovascular Disease | 6,014 (18.7) | 5,268 (19.6) | 2.3 | 2,577 (20.5) | 2,579 (20.5) | 0.0 |

| Stroke | 277 (0.9) | 261 (1.0) | 1.2 | 139 (1.1) | 139 (1.1) | 0.0 |

| Recent Myocardial Infarction | 168 (0.5) | 127 (0.5) | 0.7 | 63 (0.5) | 63 (0.5) | 0.0 |

| Heart Failure | 890 (2.8) | 918 (3.4) | 3.8 | 406 (3.2) | 430 (3.4) | 1.1 |

| Other ischemic heart disease | 3,624 (11.2) | 3,166 (11.8) | 1.6 | 1,499 (11.9) | 1,546 (12.3) | 1.1 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 178 (0.6) | 163 (0.6) | 0.7 | 84 (0.7) | 72 (0.6) | 1.2 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 999 (3.1) | 853 (3.2) | 0.4 | 435 (3.5) | 434 (3.4) | 0.0 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 991 (3.1) | 1,049 (3.9) | 4.5 | 480 (3.8) | 488 (3.9) | 0.3 |

| ACE inhibitors | 13,484 (41.8) | 11,176 (41.6) | 0.6 | 5,267 (41.9) | 5,313 (42.2) | 0.7 |

| Beta blockers | 9,662 (30.0) | 8,258 (30.7) | 1.6 | 4,001 (31.8) | 3,969 (31.5) | 0.5 |

| Loop diuretics | 2,802 (8.7) | 2,803 (10.4) | 5.9 | 1,295 (10.3) | 1,302 (10.3) | 0.2 |

| Antiplatelet | 2,331 (7.2) | 2,004 (7.5) | 0.8 | 925 (7.4) | 945 (7.5) | 0.6 |

| Anticoagulant | 1,220 (3.8) | 1,188 (4.4) | 3.2 | 569 (4.5) | 581 (4.6) | 0.5 |

| Statins | 22,401 (69.5) | 17,392 (64.7) | 10.3 | 8,529 (67.8) | 8,506 (67.6) | 0.4 |

| Other characteristics, n (%) | ||||||

| Obesity | 8,691 (27.0) | 4,708 (17.5) | 22.9 | 2,972 (23.6) | 3,040 (24.2) | 1.3 |

| Smoking | 1,865 (5.8) | 1,266 (4.7) | 4.8 | 758 (6.0) | 755 (6.0) | 0.1 |

| Combined comorbidity score | 0.4 (1.4) | 0.4 (1.5) | 0.1 | 0.5 (1.5) | 0.5 (1.5) | 0.0 |

Abbreviations: SGLT2: Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 inhibitors; SMD: Standardized Mean Differences as percentages; SD: Standard Deviation; SU: sulfonylureas

The table presents select pooled baseline characteristics after 1:1 propensity score matching. See tables II – IV in the supplement for information on all baseline covariates prior to and after propensity score matching for each database

Available for 15% of patients in the data

Primary analysis

Prior to propensity-score matching, there were 258 events for the composite cardiovascular endpoint (incidence rate per 1,000 person-years [IR] = 9.5) among SGLT2i initiators (mean follow up: 11.3 months) compared to 374 events [IR = 14.6] among sulfonylurea initiators (10.1 months), corresponding to an unadjusted pooled HR of 0.70 (95% CI: 0.60, 0.82).

In the propensity score-matched cohort, there were 107 composite cardiovascular endpoint events [IR = 9.9] among patients who initiated a SGLT2i (10.4 months) compared to 129 events [IR = 13.0] among patients who initiated a sulfonylurea (9.4 months), corresponding to a pooled adjusted HR of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.59, 0.98). Table 2 shows the pooled number of events, incidence rates and HRs for the primary analysis prior to and after propensity-score matching across the three databases (see Table VII in the supplement for database-specific information on number of events and incidence rates).

Table 2:

Risk of composite cardiovascular endpoint and heart failure hospitalization prior to and after propensity score matching

| Prior to matching | After matching | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2 (n=32,221) | SU (n=26,894) | SGLT2 (n=12,584) | SU (n=12,584) | |

| Composite cardiovascular endpoint* | ||||

| Events (IR)† | 258 (9.5) | 374 (14.6) | 107 (9.9) | 129 (13.0) |

| Mean follow-up (in months) | 11.3 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 9.4 |

| Database specific HR (95% CI)‡ | ||||

| Optum | 0.64 (0.49, 0.84) | 0.76 (0.51, 1.13) | ||

| MarketScan | 0.77 (0.59, 1.01) | 0.71 (0.43, 1.18) | ||

| Medicare | 0.69 (0.51, 0.93) | 0.81 (0.52, 1.26) | ||

| Pooled HR (95% CI)|| | 0.70 (0.60, 0.82) | 0.76 (0.59, 0.98) | ||

| HF hospitalizations | ||||

| Events (IR)† | 324 (11.9) | 581 (22.9) | 141 (13.0) | 206 (20.8) |

| Mean follow-up (in months) | 11.3 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 9.4 |

| Database specific HR (95% CI)‡ | ||||

| Optum | 0.58 (0.45, 0.75) | 0.79 (0.56, 1.11) | ||

| MarketScan | 0.48 (0.38, 0.61) | 0.51 (0.33, 0.79) | ||

| Medicare | 0.66 (0.52, 0.84) | 0.61 (0.42, 0.87) | ||

| Pooled HR (95% CI)|| | 0.57 (0.47, 0.68) | 0.64 (0.50, 0.82) | ||

Abbreviations: CI: Confidence Interval; IR: Incidence Rates; HF: Heart Failure; HR: Hazard Ratios SGLT2: Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 inhibitors; SU: sulfonylureas

Defined as the composite of MI hospitalizations, stroke hospitalizations and all-cause mortality (see text for details).

Events and IR are pooled across the three databases. Incidence rates are per 1,000 person-years of follow-up. See table V in the supplement for database-specific number of events and rates.

Hazard Ratios were adjusted via 1:1 propensity score matching constructed using >95 variables.

Analysis was stratified within each database and fixed effects meta-analysis were utilized to pool.

Prior to matching, there were 324 HF hospitalizations [IR = 11.9] in the SGLT2i group (11.3 months) compared to 581 HF hospitalizations [IR = 22.9] in the sulfonylurea group (10.1 months; unadjusted pooled HR, 0.57, 95% CI: 0.47, 0.68). After propensity score matching, there were 141 [IR = 13.0; 10.3 months] versus 206 [IR = 20.8; 9.4 months] HF hospitalizations, corresponding to a pooled adjusted HR of 0.64 (95% CI: 0.50, 0.82).

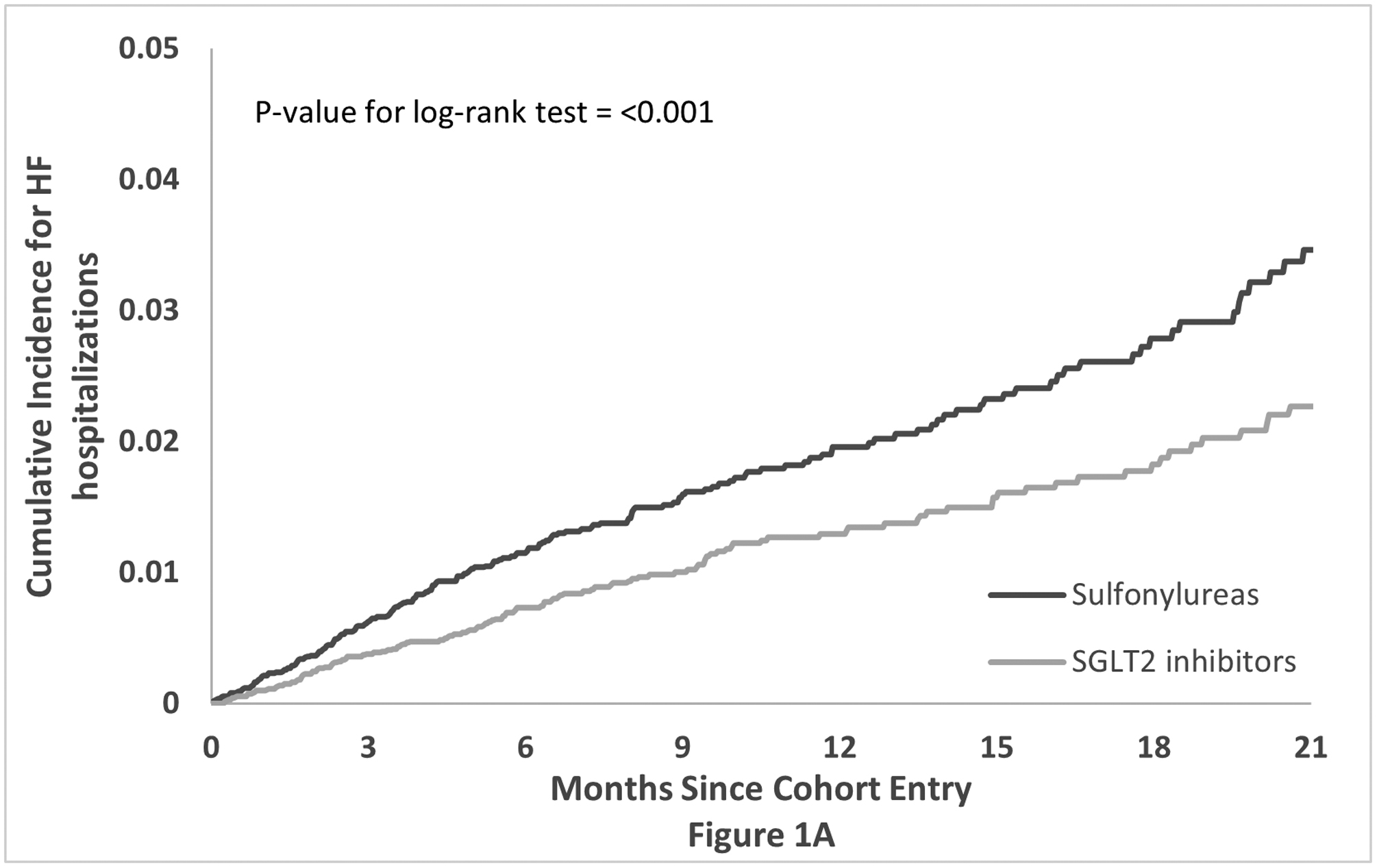

The pooled cumulative incidence of the primary composite cardiovascular and HF hospitalization outcomes in the propensity score matched cohort over time along with the corresponding p-values for the log-rank test are shown in Figure 1. The Kaplan-Meier curves for the outcome of HF hospitalization separated earlier (within the first three months; p-value for log-rank test <0.001) compared to the composite cardiovascular outcome (after the fifth month; p-value = 0.0403).

Figure 1: Propensity score matched Kaplan-Meier curves for cumulative incidence of the primary outcomes.

Propensity score matched Kaplan-Meier curves for cumulative incidence of composite cardiovascular endpoint, defined as MI or stroke hospitalizations or all-cause mortality (see text for details), (1a) and heart failure admissions (1b) for patients initiating SGLT2i or SU with existing GLP-1RA therapy.

Abbreviations: HF: Heart Failure; SGLT2: Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 inhibitors; SU: sulfonylureas

Sensitivity, subgroup and secondary analysis

Findings for the sensitivity analysis using intention-to-treat and IPTW approach were consistent with primary analysis for both primary outcomes (Table 3; see Table VII in the supplement for information on number of events and database specific estimates). There was no evidence of effect modification by CVD for either of the primary outcomes (p value for heterogeneity = 0.61 for CCE and 0.59 for HF hospitalizations). For the empagliflozin and canagliflozin versus glimepiride analysis, the point estimates were consistent with the primary analysis for both outcomes.

Table 3:

Risk of the primary outcomes in propensity score matched cohorts, sensitivity and subgroup analyses

| Total no. of patients | Events (IR)* | HR (95% CI)† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2 | SU | |||

| Composite cardiovascular endpoint‡ | ||||

| Primary analysis | 25,168 | 107 (9.9) | 129 (13.0) | 0.76 (0.59, 0.98) |

| ITT analysis | 25,168 | 269 (14.1) | 214 (11.1) | 0.80 (0.67, 0.96) |

| IPTW analysis | 59,115 | 215 (9.7) | 309 (13.5) | 0.73 (0.61, 0.87) |

| Subgroup: No CVD | 19,928 | 77 (9.8) | 75 (8.8) | 0.87 (0.53, 1.40) |

| Subgroup: CVD | 4,976 | 50 (25.2) | 37 (18.1) | 0.74 (0.48, 1.13) |

| Select active ingredients|| | 15,420 | 82 (13.0) | 69 (10.0) | 0.77 (0.54, 1.12) |

| Heart Failure hospitalizations | ||||

| Primary analysis | 25,168 | 358 (18.9) | 274 (14.3) | 0.64 (0.50, 0.82) |

| ITT analysis | 25,168 | 260 (13.5) | 343 (18.1) | 0.74 (0.57, 0.96) |

| IPTW analysis | 59,115 | 275 (12.4) | 491 (21.6) | 0.59 (0.51, 0.68) |

| Subgroup: No CVD | 19,928 | 72 (9.1) | 55 (6.4) | 0.64 (0.38, 1.09) |

| Subgroup: CVD | 4,976 | 130 (67.1) | 98 (48.5) | 0.76 (0.59, 0.98) |

| Select active ingredients|| | 15,420 | 135 (21.6) | 95 (13.8) | 0.66 (0.51, 0.86) |

Abbreviations: CI: Confidence Interval; IR: Incidence Rates; HF: Heart Failure; SGLT2: Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 inhibitors; SU: sulfonylureas; IPTW: Inverse probability of treatment weights

Events and IR are pooled across the three databases. Incidence rates are per 1,000 person-years of follow-up. See Table V in the supplement for database-specific number of events and rates.

Hazard Ratios were adjusted via 1:1 propensity score matching constructed using >95 variables and are for SGLT2i vs sulfonylureas (referent). See text for details. Analysis was stratified within each database and fixed effects meta-analysis were utilized to pool. See table VIII in the supplement for information on number of events and database specific estimates.

Defined as the composite of MI hospitalizations, stroke hospitalizations and all-cause mortality (see text for details).

Restricted to two SGLT2i (empagliflozin and canagliflozin) versus glimepiride. See text for details.

Based on the secondary outcome analyses (Table 4; see Table IX in the supplement for information on number of events and database specific estimates), the composite cardiovascular endpoint was primarily driven by numerical decreases in MI, pooled adjusted HR 0.71 (95% CI: 0.51, 1.003) and all-cause mortality, pooled adjusted HR 0.68 (95% CI: 0.40, 1.14) but not stroke, pooled adjusted HR 1.05 (95% CI: 0.62, 1.79). For the combined composite cardiovascular / HF hospitalization outcome, the pooled adjusted HR was 0.69 (95% CI: 0.55, 0.87). There was no association between SGLT2i and the control outcome of flu vaccinations; HR 0.97 (95% CI: 0.92, 1.01).

Table 4:

Risk of the secondary outcomes in propensity score matched cohorts.

| Events (IR)* | HR (95% CI)† | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2 | SU | ||

| Primary outcomes | 107 (9.9) | 129 (13.0) | 0.76 (0.59, 0.98) |

| Composite Cardiovascular Endpoint (CCE) | 107 (9.9) | 129 (13.0) | 0.76 (0.59, 0.98) |

| HF hospitalizations | 141 (13.0) | 206 (20.8) | 0.64 (0.50, 0.82) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| CCE plus HF hospitalizations | 216 (20.0) | 290 (29.4) | 0.69 (0.55, 0.87) |

| MI or stroke hospitalizations | 88 (8.1) | 100 (10.0) | 0.80 (0.60, 1.06) |

| MI hospitalizations | 60 (5.5) | 76 (7.6) | 0.71 (0.51, 1.00) |

| Stroke hospitalizations | 30 (2.8) | 26 (2.6) | 1.05 (0.62, 1.79) |

| All-cause mortality | 25 (2.3) | 34 (3.4) | 0.68 (0.40, 1.14) |

| Flu vaccination‡ | 3,954 (528) | 3,980 (503) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.01) |

Abbreviations: CI: Confidence Interval; IR: Incidence Rates; HF: Heart Failure; SGLT2: Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 inhibitors; SU: sulfonylureas; HF: Heart Failure; MI: Myocardial Infarction

Events and IR are pooled across the three databases. Incidence rates are per 1,000 person-years of follow-up. See table V in the supplement for database-specific number of events and rates.

Hazard Ratios were adjusted via 1:1 propensity score matching constructed using >95 variables and are for SGLT2i vs sulfonylureas (referent). See text for details. Analysis was stratified within each database and fixed effects meta-analysis were utilized to pool. See Table IX in the supplement for information on number of events and database specific estimates.

Administration of flu vaccine was a negative control outcome. See text for details.

DISCUSSION

Given their distinct mechanistic and pharmacodynamic profiles relating to cardiovascular risk, it was postulated – but untested in prior clinical trials or observational studies – that the addition of SGLT2i therapy in patients using GLP-1RA would result in a greater reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events compared to adding a different glucose-lowering agent. Using real world data generated from three US-based insurance claims datasets, this study demonstrates for the first time that the initiation of SGLT2i is associated with reductions in the risk of a composite cardiovascular endpoint outcome (comprised of MI, stroke and all-cause mortality) and HF hospitalizations, compared with the initiation of sulfonylureas in patients with existing GLP-1RA therapy.

This study has important clinical implications. Strategies that reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events are relevant in guiding the care of patients with T2DM because major cardiovascular events occur at significantly higher rates,19 and are the primary cause of excess mortality among patients with T2DM20–22. This study shows that adding SGLT2i to GLP-1RA reduces major cardiovascular events and HF hospitalizations. The randomized trials of SGLT2i included patients with established cardiovascular disease or multiple risk factors. In contrast, this study population includes real-world patients with and without prior cardiovascular disease or additional risk factors supporting benefit across the spectrum of established cardiovascular disease. We observed non-statistically significant reductions in MI and all-cause mortality but not stroke, with point estimates similar to those seen in the randomized clinical trials.3, 5 Furthermore, the Kaplan-Meier curves for HF hospitalizations separated early, and within 6-months of therapy initiation, similar to published trials,3–5 and observational studies.23 Findings from this study support that not only do SGLT2i reduce cardiovascular events in patients using GLP-1RA therapy, but that the magnitudes of these reductions are similar to what was observed in cardiovascular trials with SGLT2i – where GLP-1RA use was minimal.24

While no prior study has examined the cardiovascular benefits of combining SGLT2i and GLP-1RA, two short-term clinical trials have demonstrated clinically relevant improvements in glycemic control with acceptable tolerability. DURATION-8 was a 28-week randomized clinical trial which showed that co-initiation of SGLT2i (dapagliflozin) and GLP-1RA (exenatide) was superior to either agents alone and to placebo in reducing hemoglobin A1c, blood-pressure and body weight.25 The AWARD-10 was a 24-week randomized trial that assessed the impact of using GLP-1RA (dulaglutide) and any SGLT2i and found superior reductions in hemoglobin A1c with the combination compared to placebo.26 Together these studies support additive glucose lowering effects, but do not elucidate their cardiovascular effects.

In routine clinical care, there may be several barriers to adding SGLT2i in patients using GLP-1RA therapy. These include high drug-costs associated with the use of two branded products (to date neither agent has a generic approved), long-term adherence to a complicated glucose-lowering regimen consisting of oral and injectable therapies, and an unwillingness among some patients to use injectable therapies; the recent approval of oral semaglutide may alleviate some, but not all, of these concerns. Additionally, GLP1-RA use may be limited by their gastrointestinal intolerance among other adverse effects, while SGLT2i may be associated with unique adverse reactions, including diabetic ketoacidosis and genital infections,5, 27–30 that require consideration in deciding whether to prescribe a SGLT2i.

This study took several steps to mitigate the potential for confounding by restricting analysis to new-users and adjusting for more than 95 pertinent variables. By pooling data from three US-based insurance claims, this investigation included over 12,000 matched pairs; patients were sourced from routine clinical care (i.e. no enrichment strategies were employed) ensuring wide generalizability of the study findings across age groups and in patients with employer sponsored health plans and patients in Medicare fee-for-service and managed care plans. Moreover, estimates were consistent across a range of sensitivity (e.g. ITT analysis) and subgroup analyses highlighting the robustness of the study findings. Finally, information on medication dispensing – rather than prescribing data – were available for all three databases, reducing the opportunity for exposure misclassification.

Study limitations are noted. First, due to the observational nature of the design, our study is susceptible to residual confounding due to lack of randomization. For instance, patients initiating sulfonylureas were different from those initiating SGLT2i and therefore we were able to match less than half of patients in the sulfonylurea arm (smaller of the two groups). Furthermore, although we measured and adjusted for several potential confounders and their proxies, information on important diabetes related variables such as duration of diabetes or cardiovascular risk factors such as body mass index or blood pressure were unavailable. However, prior studies have shown that balance in these unmeasured characteristics can be achieved with the use of claims-based proxies in administrative claims data.31 Further, the requirement of use of GLP-1RA in both groups may have further reduced imbalance among unmeasured covariates. Finally, after adjustments for previous cardiovascular events and conditions, severity of diabetes, other comorbidities (e.g. chronic kidney disease) and treatments for cardiovascular conditions and diabetes, we do not expect these factors to be substantially imbalanced between the two treatment groups. Second, treatment initiation was defined using a 180-day period so that some patients may have been exposed to the treatment prior to this time-window. Third, therapeutics were assessed by drug class and therefore individual agents may have contributed disproportionately to findings. To account for this, we conducted a subgroup analysis of patients using empagliflozin and canagliflozin versus glimepiride which produced similar findings.

In conclusion, in this large real-world cohort of propensity score matched 25,168 diabetic patients on GLP-1RA, the addition of SGLT2i conferred additional cardiovascular benefit. This study offers important clinical information by increasing understanding of the cardiovascular benefits of adding SGLT2i to existing GLP-1RA therapy and provides support for SGLT2i use in this setting. These findings have relevant implications for preventing further cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Clinical perspective.

What is new?

Given their orthogonal effects on cardiovascular health, it has been postulated that the addition of SGLT2i to baseline GLP-1RA therapy may confer additional cardiovascular benefits; however, there were few participants using both agents in randomized clinical trials.

Patients adding either SGLT2i or sulfonylureas were identified within 3 US observational datasets of patients with type 2 diabetes already on GLP-1RA,

Compared to initiation of sulfonylureas, the addition of SGLT2i conferred greater cardiovascular benefit; the magnitude of this benefit was comparable to that observed in cardiovascular outcome trials of SGLT2i versus placebo where baseline GLP-1RA use was minimal.

What are the clinical implications?

As major cardiovascular events occur at significantly higher rates in patients with type 2 diabetes, strategies that reduce the incidence of such events are relevant in guiding patient care.

Short term trials have demonstrated that the combination of SGLT2i and GLP-1RA results in clinically relevant improvements in glycemic control with acceptable tolerability. This study provides the evidentiary support for adding SGLT2i to existing GLP-1RA therapy to reduce cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes in routine clinical care

Funding:

This study was funded by the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- IR

Incidence Rates

- HF

Heart Failure

- SGLT2

Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 inhibitors

- SU

sulfonylureas

- IPTW

Inverse probability of treatment weights

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: CD is supported through New Jersey Alliance for Clinical and Translational Science (UL1TR003017). EP is supported by a career development grant (K08AG055670) from the National Institute on Aging. She is also co-investigator of investigator-initiated grants to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital from GSK and Boehringer-Ingelheim, not directly related to the topic of the submitted work. ABG completed this work through her appointment at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She is an employee of Novartis Institutes of Biomedical Research.

Supplemental Materials:

Supplementary Figure I

Supplementary Tables I – IX

REFERENCES

- 1.Association AD. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:S98–S110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vallon V The mechanisms and therapeutic potential of SGLT2 inhibitors in diabetes mellitus. Annual review of medicine. 2015;66:255–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, De Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, Law G, Desai M and Matthews DR. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377:644–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, Silverman MG, Zelniker TA, Kuder JF and Murphy SA. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380:347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE and Woerle HJ. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373:2117–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JF, Nauck MA, Nissen SE, Pocock S, Poulter NR and Ravn LS. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375:311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeFronzo RA. Combination therapy with GLP‐1 receptor agonist and SGLT2 inhibitor. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2017;19:1353–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmanan M, Pais P, Probstfield J, Riesmeyer JS, Riddle MC, Rydén L, Xavier D, Atisso CM, Dyal L, Hall S, Rao-Melacini P, Wong G, Avezum A, Basile J, Chung N, Conget I, Cushman WC, Franek E, Hancu N, Hanefeld M, Holt S, Jansky P, Keltai M, Lanas F, Leiter LA, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Cardona Munoz EG, Pirags V, Pogosova N, Raubenheimer PJ, Shaw JE, Sheu WH and Temelkova-Kurktschiev T. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Levin R and Schneeweiss S. A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2011;64:749–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiyota Y, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Cannuscio CC, Avorn J and Solomon DH. Accuracy of Medicare claims-based diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction: estimating positive predictive value on the basis of review of hospital records. American heart journal. 2004;148:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrade SE, Harrold LR, Tjia J, Cutrona SL, Saczynski JS, Dodd KS, Goldberg RJ and Gurwitz JH. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2012;21:100–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saczynski JS, Andrade SE, Harrold LR, Tjia J, Cutrona SL, Dodd KS, Goldberg RJ and Gurwitz JH. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying heart failure using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2012;21:129–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate behavioral research. 2011;46:399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Communications in statistics-simulation and computation. 2009;38:1228–1234. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin PC, Lee DS and Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133:601–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borenstein M, Hedges L and Rothstein H. Meta-analysis: Fixed effect vs. random effects. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Friede T, Röver C, Wandel S and Neuenschwander B. Meta‐analysis of few small studies in orphan diseases. Research Synthesis Methods. 2017;8:79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Austin PC and Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Statistics in medicine. 2015;34:3661–3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Group UPDS. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). The lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleinman JC, DONAHUE RP, HARRIS MI, FINUCANE FF, MADANS JH and BROCK DB. Mortality among diabetics in a national sample. American journal of epidemiology. 1988;128:389–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brun E, Nelson RG, Bennett PH, Imperatore G, Zoppini G, Verlato G and Muggeo M. Diabetes duration and cause-specific mortality in the Verona Diabetes Study. Diabetes care. 2000;23:1119–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collaboration ERF. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364:829–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patorno E, Goldfine AB, Schneeweiss S, Everett BM, Glynn RJ, Liu J and Kim SC. Cardiovascular outcomes associated with canagliflozin versus other non-gliflozin antidiabetic drugs: population based cohort study. bmj. 2018;360:k119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, Im K, Goodrich EL, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A and Furtado RH. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. The Lancet. 2019;393:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frías JP, Guja C, Hardy E, Ahmed A, Dong F, Öhman P and Jabbour SA. Exenatide once weekly plus dapagliflozin once daily versus exenatide or dapagliflozin alone in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin monotherapy (DURATION-8): a 28 week, multicentre, double-blind, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology. 2016;4:1004–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludvik B, Frías JP, Tinahones FJ, Wainstein J, Jiang H, Robertson KE, García-Pérez L-E, Woodward DB and Milicevic Z. Dulaglutide as add-on therapy to SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes (AWARD-10): a 24-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology. 2018;6:370–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dave CV, Schneeweiss S, Kim D, Fralick M, Tong A and Patorno E. Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and the risk for severe urinary tract infections: a population-based cohort study. Annals of internal medicine. 2019;171:248–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fralick M, Schneeweiss S and Patorno E. Risk of diabetic ketoacidosis after initiation of an SGLT2 inhibitor. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376:2300–2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dave CV, Schneeweiss S and Patorno E. Association of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor Treatment With Risk of Hospitalization for Fournier Gangrene Among Men. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1587–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dave CV, Schneeweiss S and Patorno E. Comparative risk of genital infections associated with sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:434–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patorno E, Gopalakrishnan C, Franklin JM, Brodovicz KG, Masso‐Gonzalez E, Bartels DB, Liu J and Schneeweiss S. Claims‐based studies of oral glucose‐lowering medications can achieve balance in critical clinical variables only observed in electronic health records. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2018;20:974–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.