Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a significant national and global public health concern, with COVID-19 pandemic increasing IPV and associated health issues. Immigrant women may be disproportionately vulnerable to IPV-related health risks during the pandemic. Using qualitative in-depth interviews, we explored the perspectives of service providers (n = 17) and immigrant survivors of IPV(n = 45) on the impact of COVID-19 on immigrant women, existing services for survivors and strategies needed needed to enhance women’s health and safety. Participants reported issues such as increased IPV and suggested strategies (e.g. strengthening virtual platforms). The findings could be informative for providers in national and international settings.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious national and global public health concern, that has the potential to be exacerbated in scope and impact by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. COVID-19 has led to the potential of enhanced risk for increased IPV due to factors such as forced co-existence with the abuser, and financial stress. Further, in some world regions, emerging evidence suggests that the COVID-19 outbreak has also curtailed access (Fraser, 2020) as well as help-seeking by survivors (Kaukinen, 2020). Immigrant women, a group disproportionately affected by IPV and IPV-related homicides (Sabri et al., 2018), may be at even further risk for IPV and its consequences. Immigrant women already face numerous barriers to help-seeking for IPV, including social isolation, lack of support, stigma of IPV (Amanor-Boadu et al., 2012; Sabri et al., 2018), uncertain or undocumented immigration status and threats of deportation as a means of control by the abuser, and limited or lack of knowledge about resources, and language barriers (Sabri et al., 2018; Sabri et al., 2018). These barriers can be exacerbated during COVID-19 with the stay-at-home orders and co-habitation with the abuser. Given how little is known at present about how the pandemic may be impacting survivors from diverse groups, we conducted an exploratory qualitative study to better understand immigrant survivors’ and service providers’ perspectives on a) the impact of COVID-19 on survivor’s health and safety, b) services survivors received for their health and safety, and c) suggestions for how providers could mitigate the risk for increased IPV during the high-risk pandemic environment. The findings will be informative to national as well as international audience as to the impact of COVID-19 on survivors from immigrant communities.

Background

The global prevalence of IPV remains a public health issue with potential for surging on account of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) indicates that 1 in 3 women suffer from IPV internationally, with 42% of these cases leading to physical injury, and 38% of reported murders being linked to IPV (John et al., 2020; WHO, 2013). Immigrant women have long been more susceptible to IPV as a result of immigration related factors (e.g. language barriers), which cumulatively perpetuate cycles of abuse. Within the United States (US), prevalence of IPV in the community-based samples of immigrant women range from 17% to 70.5% (Goncalves & Matos, 2016). Times of crises such as outbreaks and natural disasters elevate acts of violence against women (Kabonesa & Kindi, 2020; Roesch et al., 2020; Schumacher et al., 2010; Weitzman & Behrman, 2016). Drastic alterations to normalcy commonly associated with pandemics can exacerbate occurrences of IPV (John et al., 2020; van Gelder et al., 2020). Existing literature has attributed these events to stress and instability of employment, poverty, and social and functional isolation (Roesch et al., 2020; van Gelder et al., 2020). A shift in prioritizing essential services has led to the interruption or elimination of critical IPV resources. Further, necessary quarantine measures have increased both the extent of time with, and exposure to, abusive partners (United Nations, 2020).

The United Nations has recognized this growing crisis as a shadow pandemic, as women who are, or have in the past been, survivors of IPV are now at greater risk of experiencing violence (Milford & Anderson, 2020; Mlambo-Ngcuka, 2020). The recently imposed “shelter-in-place” orders and business closures—although conducive to eliminating spread of the virus—permit greater restraints on survivors of IPV and increased possession of power among abusers, and subsequently augment rates of abuse and violence (van Gelder et al., 2020). Lack of access to IPV resources and psychosocial support services as a result of global implementation of social distancing measures have contributed to amplification of IPV. Therefore, disparate gendered outcomes of IPV and IPV-related health consequences are rising in prevalence as a result of the novel COVID-19 pandemic (Kabonesa & Kindi, 2020; United Nations, 2020).

The formulation of possible support frameworks during the pandemic are essential to providing an adequate response to survivors of IPV, particularly those from marginalized groups. What is not yet known is the substantive impact of the pandemic specifically on immigrant survivors of IPV, who are an underserved and marginalized group. This study attempts to fill this gap in the literature, as well as address conceivable strategies providers can implement to protect immigrant women. The findings can be useful for improving prevention and risk mitigation strategies for IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic and similar crises situations.

Materials and methods

In this qualitative study, 45 in-depth interviews and 17 key-informant interviews were conducted with participants from diverse world regions (e.g. Africa, Asia and Latin America). For in-depth interviews, eligible survivors were English-speaking foreign-born immigrant women residing in the US, over 18 years of age, with experiences of IPV within the past year. For key informant interviews, providers were those who had two or more years of experience serving immigrant survivors of IPV. Using purposive and snowball sampling methods, survivors were recruited from multiple regions of the US: Massachusetts, New Jersey, Texas, Illinois, Maryland, Virginia and Washington DC. Recruitment strategies included posting flyers at organizations serving abused immigrant women as well as verbal invitation to participate via assistance from staff at partner organizations. Interested and willing survivors either directly approached the research team or gave permission to be contacted by the research team. Data collection concluded as we approached saturation of information, i.e. novel findings on key themes related to our study aims were no longer emerging.

After obtaining oral consent, the interviews were conducted over the phone or Zoom video conference, depending upon the preference of the participant. The in-depth interview guide for survivors focused on the effect that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on their relationship, accessibility of IPV services, and identification of other pertinent needs or safety concerns during the pandemic. Interviews with providers included questions pertaining to the impact of COVID-19 on their ability to provide customary services to survivors of IPV, cogent strategies being used to deliver adequate care during the pandemic, and their perspectives on how services could be improved during the pandemic. The sessions were digitally recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim using an external transcription service. Providers were compensated $40 and survivors were compensated $35 for their participation. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the home institution of the study investigators.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using a systematic inductive, thematic analysis approach, drawing upon principles of grounded theory to transform documented raw data into coded, topical concepts (Chandra & Shang, 2019; Holton & Walsh, 2017). A thematic analysis was chosen to draw theoretical backing for structural and sociocultural frameworks impelling IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic based on participants’ socially constructed experiences (Braun et al., 2019). The analysis focused on an understanding of causes and risks associated with an altered context for the occurrence of IPV and receipt of services for IPV by immigrant women during the pandemic, with a focus on perceived needs and possible support strategies. Thorough review of participant interview transcripts was the initial step in the qualitative data analysis process (Braun et al., 2019). Two members of the research team subsequently completed independent coding of the transcripts. Specifically, primary thematic root codes and child codes were formulated based on the reported individual experiences of immigrant women and were then grouped according to broader conceptual patterns that emerged (Braun et al., 2019).

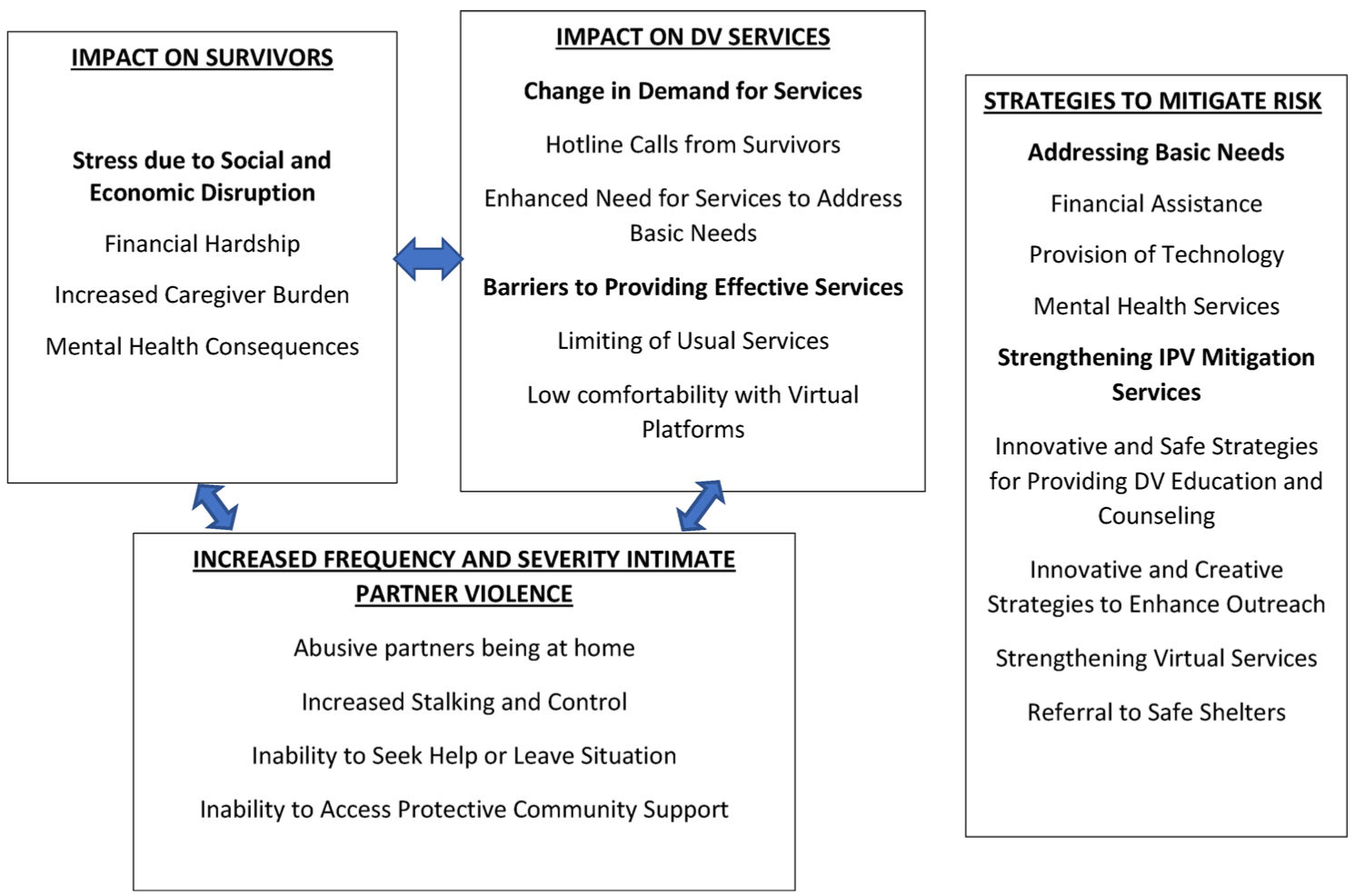

The qualitative analysis team included two individuals from public health and nursing fields: a qualitative researcher enrolled in a master’s degree program in social factors of health and a practicing nurse with a master’s degree in public health. To ensure both credible and reliable findings, the team members routinely convened throughout the analysis process to review and compare codes and general themes, and to mitigate any inconsistencies in coding patterns. To ensure objectivity and prevent research biases, the researchers frequently conducted peer debriefing sessions to review the data analysis process and circumvent subjective interpretations of participants’ responses. The team members also regularly met with the Principal investigator to discuss the analysis as well as any consistencies and inconsistencies in interpretation. Data analysis was conducted using the latest version (v. 8.3.35) of Dedoose qualitative and mixed-methods analysis software (SocioCultural Research Consultants, 2019). Frequency of individual code incidence was analyzed, and similar codes were grouped together based on emergent themes. A conceptual model was then created, categorized by three categories of themes: impact of COVID-19 on IPV survivors, impact of COVID-19 on domestic violence services, and risk mitigation of IPV incidence by service providers (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A conceptual model representing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrant survivors of intimate partner violence and domestic violence services.

Results

Impact of COVID-19 on immigrant survivors of IPV

All participants described a reciprocal and reinforcing relationship between increased life stressors and IPV due to the COVID 19 pandemic and associated response. Together, these interacted to also shape the mental health of survivors.

Stress due to social and economic disruption

Financial hardship associated with COVID-19 and COVID-19-related delays in immigration processes.

Financial hardship resulting from unemployment or lay-offs during the economic shutdown and associated downturn, as well as a fear of job loss and future financial strain, were both described as creating or amplifying conflict within families and thus increasing frequency and severity for IPV for women in abusive relationships. Most survivors and service providers mentioned the effects of unemployment on the ability to have basic needs met in the family (rent, food, childcare) and husbands losing their jobs and taking out on their wives:

“The husbands lost their jobs [during COVID-19], and they’re taking out all the heat on the woman.”

(Survivor, Age 46, Asian)

Some participants reported delayed immigration processes affected them including delays in processing of visas for persons already residing in the US and for family members outside of the US waiting to enter. Being undocumented or having a work visa due to job loss and inability to send money to family abroad was an added stress: “the focus has been on just surviving because it’s not just COVID-19 affecting people here. It’s affecting people back home. When I’m on un- unemployment, I don’t have enough money to send back home” (Service Provider, Age 40, African). A service provider shared the impact of the intersection between immigration status, access to basic needs and gender-based violence: “Our undocumented clients have to work under the table, especially during the coronavirus. When you look at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs … there’s not enough money for food or rent … or to keep phones. With abuse, the spouse controls the finances” (Service Provider, Age 24, Latina). The same service provider mentioned that undocumented immigrants are unable to avail public benefits such as unemployment and government assistance which contributes to increased financial hardship: “Some immigrants don’t have access to health insurance or public benefit because they don’t qualify. Sometimes their kids do, but if their kids use it, there are rumors about a public charge and it could impact their immigration case” (Service Provider, Age 24, Latina). Lack of medical insurance due to job loss or immigration status, delayed healthcare seeking, and increased medical bills for survivors treated for COVID-19 infection was an added stress for survivors: “I don’t have anything to be able to travel or go somewhere. I don’t have medical insurance. If something happens, then how can I recover?” (Survivor, Age 39, Asian)

Increased caregiver burden.

Most survivors and service providers mentioned increased caregiver burden due to stay-at-home orders, school closures, difficulties with childcare and barriers with virtuals schooling. Caregiver burden was described when survivors were unable to work due to additional childcare responsibilities. Because of social distancing and closures of public spaces women could no longer bring their children outside of the house: “It’s double the burden. They don’t have a job now, and also their kids are home. So, they can’t really go out with their kids” (Service Provider, Age 31, Asian). Further, there were barriers to virtual learning with their children including language barriers and limited access to the technology: “I had a client who said, “My four kids, who are in middle and high school, are doing their homework on my one cell phone, and they’re all failing” (Service Provider, Age 24, Latina).

Mental health consequences.

Some participants described the ways that mental health of survivors has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The closure of community health services, lack of basic needs and being at home with their abusive partners had a negative impact on mental health. The impact was described in the form of depression, and uncertainty: “It was very hard on me. I was sleeping the whole day. I wasn’t able to search for jobs. I was very depressed … was like, “there’s just no hope.” (Survivor, Age 28, Asian). Fear of contracting COVID-19 was mentioned by multiple participants who reported having not left their homes. However, immigrant women are also less likely to seek help for mental health due to stigma around mental health issues: “The lack of communal spaces has really affected the morale and mental health of folks. And layered on to that, there’s already stigma around talking about mental health” (Service Provider, Age 40, African). Other mental health impacts were highlighted in the form of increased anxiety related to current political climate related to immigrants and increase in gun purchases for protection.

Increased frequency and severity of intimate partner violence

The COVID-19 pandemic was reported to increase frequency and severity of IPV for immigrant women in abusive relationships due to factors such as abusive partners being at home. Other risks reported were increase in gun purchase and decrease in clients seeking legal services.

Abusive partners being at home.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and associated factors such stay-at-home orders, travel restrictions, unemployment and immigration delays, abusive partners were now more at home with survivors. This placed immigrant women at risk for more frequent and severe IPV. Before we had the ability to walk away. Now, when we are confined to strictly staying at home, it just puts the abuser and the victim in a very tense emotional situation that cause them to be more abusive” (Service provider, Age 49. Latina).Survivors and service providers mentioned the increase in frequency and severity of violence for women and children due to the increased proximity to their abusers in their homes. Because of school closings, professionals were no longer able to observe children outside of their home. So, there was also increased risk for child abuse. There were also limitations on privacy which made it difficult to seek help because of fear of the abusive partners: “Everyone has 24 h in a day, but I feel like I have more than that but it’s not my time. I guess, the pandemic really, really impacted me because of him being always at home” (Survivor, Age 40, Asian).

Increased stalking and control.

Participants reported that abusive partners were increasing their stalking and monitoring behaviors. Stalking included watching women’s every move in the house and monitoring who they talk to outside of the household, as reflected in the following quote: “Survivors are telling us how stalking has just taken on a whole new meaning now because he’s in the house all the time. He watches how do I cook. He is home all the time.watching every little move.” (Service Provider, Age 50, Asian). Some participants described the ways in which control increased during the pandemic. Stay-at-home orders reduced opportunity for women to leave home to access their formal and informal systems. Control strategies included financial control, trying to get survivors pregnant, controlling when survivors can leave the house, means to managing childcare, and limited access to services. Few survivors shared with some service providers that their partner has threatened to infect them with COVID-19 as a form of controlling behavior. The threats included their abuser not wearing a mask to purposefully expose them to COVID-19 and then manipulating them, as evidenced by this quote: “If you send me to jail, I will be more able to contract the Covid –19” we heard that a lot, so people didn’t call the police”(Service provider, Age 54, Latina).

Inability to seek help or leave relationship.

Many participants repeatedly reported the barriers survivors face when attempting to seek help or leave their relationship. These barriers included fear of being undocumented, halting of divorce process, money affecting their ability to leave the relationship, and lack of privacy to seek services. Undocumented immigrants delayed reporting abuse for fear that themselves or family members will be deported back to their country of origin. Multiple survivors mentioned that they did not have the economic resources to relocate due to financial hardships the pandemic has caused. Abusive partners staying at home also affected women’s ability to make and receive IPV service-related calls, as well as physically leave their homes to seek services. For instance, a survivor shared her inability to stay with friends or family due to social distancing: “My husband asked me to leave the house. But with a crisis, people are scared to let you in their houses … I went through that with this COVID-19” (Survivor, Age 27, African).

Inability to access protective community support via community babysitting.

Providers also discussed the impact the pandemic has had on ‘community babysitting’. This was described as members of the immigrant survivor’s cultural community volunteering to babysit their children as a protective measure from their abuser. When abuse is known to be a factor in the relationship, community members volunteer to keep the abusive partner accountable during their visit with the family. This was described as a “network of unspoken support.” As the pandemic has limited social visits this practice has also been shut down. A member of community goes to a person’s home who’s being perpetrated on and sits there all day. The perpetrator is less likely to perpetrate when there’s another member of the community present … That can’t exist anymore … ” (Service provider, Age 40, African).

Impact of COVID-19 on domestic violence (DV) services

Change in demand for services

Change in hotline calls from survivors.

Most providers mentioned the changes in the amount and acuity of domestic violence hotline calls from survivors. There were mixed responses regarding the amount of calls coming in with some participants reporting an increase in calls, and others, a decrease. Both increases and decreases were attributed to an increase in IPV. Decreased calls were attributed to greater stalking and control from the part of the abuser therefore limiting women’s ability to call hotline services. Increased calls were attributed to an increase in abuse. Acuity or severity of the calls was mentioned by all participants and was said to have unanimously increased. “The calls are far more acute. People are thinking that survivors don’t have the privacy to call, and that’s why the calls are down. And then when they do call, they’re, trying to get all the information out” (Service provider, Age 50, Asian). One service provider also mentioned an increase in hotline calls from abusers themselves as they sought relationship advice.

Enhanced need for services to address basic needs.

In response to the enhanced basic needs of immigrant survivors because of COVID-19, participants discussed the ways in which DV services have responded or should respond. Providers mentioned often that women requested necessities because this was their current priority. All participants mentioned how these demands had changed during COVID-19 and that immigrant survivors’ disparities were worsened. “It’s impacted services in a way that– the disparities are so glaringly in your face right now that you can’t even look away” (Service provider, Age 24, Latina). Another service provider mentioned how DV organizations were addressing the need and costs of cell phones. “Domestic violence agencies are using some of the COVID relief funding to obtain older, used phones, refurbished phones, and giving that out for free. And then the agency’s paying for low-cost COVID-specific monthly plans” (Service provider, Age 50, Asian)

Barriers to providing effective services

Limiting of usual services.

One of the major ways the pandemic has affected DV services and organizations, is the limited ability to provide full range of services. Due to restrictions on gatherings and services deemed “non-essential” organizations were unable to provide for survivors in the same manner as before COVID-19. Besides barriers such as difficulties connecting with survivors due to abusers being home, limited time for phone conversation, difficulty delivering food with controlling partners, and inability to transport survivors in their cars, participants commonly reported barriers associated with closure of in-person services. “We have gone from being very supportive to prioritizing things. Before-COVID, we would be there in person for help. Now, everything is over the phone. So, it seems a little bit more transactional. Less personal” (Service Provider, Age 32, Latina).

The closure of community or mobile advocacy services due to restrictions on public gatherings was another limitation. Providers discussed the cultural implications as many immigrant groups value building relationships with other women. Most of my work is done in community spaces. With COVID-19, those spaces are no longer there. For a culture that puts the most value on community and coming together for support, it has just been devastating (Service provider, Age 40, African). The closure of offices has limited the ability of survivors to meet with advocates in person. The closure of shelters means that there is not a place for women to go if they are in an abusive situation. Without family or contacts and closed shelters there is not a physical space for immigrant women to be safe. “Survivors cannot go anywhere if they have no family. If there is a family, they’re not going to take her. Now, they are stuck with their spouse. There are no shelters. They cannot do anything” (Survivor, Age 46, Asian).

Low comfortability with virtual platforms.

Participants mentioned barriers immigrant survivors face in using virtual platforms for DV services. This included lack of resources to engage in virtual services and the comfortability of women with technology. “It is not like we can get people together on Zoom. We’re leaving a, huge percentage of women out because of lack of resources.” (Service provider, Age 40, African). Some participants mentioned the lack of access to internet, and the preference of women to engage in face-to-face interactions. In-person services were beneficial for mental health as it allowed survivors to leave their homes. “It was an excuse to get out of the house to meet my appointments … even if I’m having a bad day, or if I’m feeling depressed, it will force me to get up, look good and go out” (Survivor, Age 28, African).

Perceived strategies to mitigate the risk for increased IPV for survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic

Providing necessities

Both service providers and survivors mentioned several strategies to meet survivors’ basic needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. These included provision of technology (e.g. cell-phones and tablets) for survivors with lack of access to technology, financial assistance, and mental health services. Financial assistance was discussed by providers and survivors as an essential need. Assistance manifested in housing assistance, money for groceries, and medical assistance. Mental health services were also reported by providers in the form of therapy sessions and relaxation techniques. A service provider shared her experience with being flexible to meeting survivors where they are at and addressing their most pressing need during the pandemic: “. It’s more adjusting of what the needs for the community and for the children and for whomever they consider their family.” (Service provider, Age 54, Latina)

Strengthening IPV mitigation services

Innovative and safe strategies for providing domestic violence education and counseling.

All participants, survivors and providers, mentioned the need for developing effective strategies for DV education and counseling during the pandemic. Reported components of education and counseling were discussing safety strategies, identifying relationship red flags, and providing de-escalation techniques for partners. Safety strategies for protection within homes were to be provided as necessary for women during the pandemic since many women are at home all day with their abusers. Implementing strategies to stay safe and decreasing likelihood of conflict with the abuser were suggested for survivors with limited ability to leave. One participant stated that if there are limited services or women are unable to seek services, women should try to just endure the abuse and survive with their abuser. “If you are in the same house with an abusive partner, anything could be a trigger. If you can’t get out, then don’t get into any compromising situation. Try to stay quiet, to be as nice as you can” (Survivor, Age 27, African).

Innovative and creative strategies to enhance outreach.

Both survivors and service providers highlighted the need for innovative and creative strategies to enhance outreach during COVID-19 in response to the barriers previously mentioned. Participants shared strategies such as putting DV information in public spaces such as grocery stores, covertly providing information to survivors during basic needs provision or in bags of food during distribution and distributing surveys to understand survivor needs. A service provider mentioned having culturally specific food drop-offs including pre-cooked meals for families to prevent abuse from partners who have control over meals. Some providers particularly emphasized the need for resource provision specific to immigrant survivors. A survivor shared an example of how to reach survivors in religious places: In the mosque, somebody dropped a flyer about Muslim services for mental health and healthcare. It had a little description about what is domestic abuse, and if you are facing it you should contact this person” (Survivor, Age 31, Asian).

Referral to safe shelters.

Some participants reported that many DV shelters were closed during the pandemic. Service providers shared their perspectives on how to refer women to safe places and strategies to ensure safety during COVID-19. Some participants mentioned referring women to contracted hotels if they needed to be relocated and providing protective health measures such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and safe meeting spaces for survivors. One provider shared their experience with taking these measures: “We have to partner with some organizations, locally, and say, “We are going to contract with the hotel for overflow space. It’s not ideal. but it’s going to help for safety right now.” (Service Provider, Age 54, Latina). Some survivors discussed their fear of going to a shelter during the pandemic because of risk for infection. Some providers enforced protective health measures such as masks, social distancing, cleaning of common surfaces, and health screening questions before entry. “We have taken measures, including how many people can be in a room in our emergency shelter. We have protocols to respond if a survivor in our shelter tests positive or has symptoms. We have a place where we’re able to take them to stay for quarantine. We’re wearing gloves and masks. And we’re developing’ telework policies” (Service provider, Age 36, Latina).

Strengthening virtual services.

To reach survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic, most participants mentioned strengthening virtual platforms. It was also important to identify ways to remotely connect with survivors who face barriers in using virtual platforms. Recommendations on virtual applications and providing safe tailored safety planning remotely were brought up in nearly every interview. Reported virtual services for survivors were support groups, mental health services, and personal check-ins. One service provider shared information about which applications were being used to maintain communication: “Because we can’t meet in person, a lot of it is happening’ via phone communication, Skype, or WhatsApp, which is an app that a lot of folks use” (Service provider, age 49, Latina).

Other applications mentioned by participants included text messages, emails, and video conferencing via Thera-Link and Zoom. Tailored safety planning for virtual services included the use of code words and finding a safe time to contact survivors. Some survivors mentioned need for a 24-hour crisis line and another survivor mentioned running online batterers intervention groups which could provide occupied time for abusive partners and relief for survivors. Also discussed was teaching de-escalation techniques to partners during conflict.

Conducting safe telephone check-ins and text messages.

Telephone check-ins and text messages were the most frequently recommended to connect with survivors during COVID-19. Telephone check-ins entailed calling the participant on the phone to ensure they are safe. For instance, a survivor shared how her father checked on her when he could not reach her. “He took my phone and locked me up. After two days, he unlocked me when my father called and said “I’m trying to get in touch with her” Had he not called; I would have been still locked up” (Survivor, Age 32, Asian). Some providers mentioned incorporating a safety algorithm so that if a survivor did not answer the designated number of calls, a provider would visit the address in person. Text messages were also mentioned as a method to check-in with survivors and provide DV services. Safety strategies described with text messaging included ensuring that messages would delete shortly after sending in case that the survivor’s abuser was monitoring the phone.

Providing safe virtual and tailored safety planning.

Survivors and providers continually brought up the importance of safety considerations in providing tailored safety plans when using virtual services during the pandemic. Participants shared the risks of discovery when women use virtual services and the associated risk for increased violence. They also shared their perspectives on various methods to mitigate this risk including using code words and hand signals when survivors are engaging with providers or others and finding an appropriate time to call women. Examples of code words were given including common daily words such as a teacher, and culturally specific words to indicate the survivor’s audience that help is needed. The use of a hand signal during video conference was mentioned by several participants. Finding an appropriate time to meet with providers was offered in the form of text message and pin codes. Survivors were recommended to enter the pin code to unlock messages from service providers, indicating it was a safe time to speak. “They have to very clear with the reality of that family and find ways to connect and time when the abusive partner is not around. It changes a lot, case by case” (Service Provider, Age 54, Latina).

Discussion

The COVID-19 epidemic is found to be disproportionately impacting minorities (Grace et al., 2020) which include immigrant communities. This indicates that the existing health disparities may be exacerbated by COVID-19, including IPV-related disparities among marginalized populations. Thus, tailored interventions are needed to address these issues among marginalized populations such as immigrant women. For instance, strategies can be developed to support immigrant survivors with lack of access to technology. Immigrant IPV survivors and service providers alike suggested increased abuse- and non-abuse-related stressors because of the pandemic. Immigrant women are at high risk for negative outcomes of the pandemic because of factors related to, but not limited to, increased partner surveillance and control, indeterminate immigration status, and limited or lack of social protections. Greater instances of abusive partners sequestered at home as a result of both quarantine measures and recent unemployment, contribute to limited opportunities for survivors to seek help or leave their relationship.

Survivors’ accounts of increased episodes of stalking and authoritative exercise of control were in alignment with prior research related to partner activity and survivor limitations during catastrophic events (Campbell, 2020). Research has indicated that unforeseen crises situations can result in increased physical, sexual and psychological partner abuse, but here are only two population-based studies that show a significant increase. One was a self-report retrospective study conducted post Hurricane Katrina, which documented a near doubling of physical IPV rates for women, while psychological abuse increased significantly for both men and women (Schumacher et al., 2010). The highest quality evidence comes from an analysis of Demographic Health Survey data pre and post the 7.0 magnitude earthquake in Haiti in 2010 which showed a higher than normal prevalence of IPV in areas that were significantly devasted by the disaster (Weitzman & Behrman, 2016). There is also anecdotal evidence from, China, Australia, Italy, France, and Brazil reporting higher prevalence of IPV during the current pandemic (Campbell, 2020; van Gelder et al., 2020). The increase in IPV that was reported by participants in this study is congruent with the research and with the risk factors associated with the current pandemic.

Survivors of IPV need to be better integrated into current relief efforts related to the COVID-19 pandemic. This can be accomplished by targeting healthcare workers by standardizing IPV screening during healthcare visits (now primarily telemedicine visits). The healthcare staff should undergo training to effectively identify at-risk immigrant women, wherein safety plans can be discussed or referrals to local domestic violence organizations can be made. Funding efforts toward both comprehensive and culturally specific legal, medical, and housing services is another exigent matter to be addressed for survivors of IPV, especially for immigrant survivors. Similarly, law enforcement needs to be made aware of the cultural intricacies associated with immigrant groups to effectively intervene in IPV situations, as they are traditionally one of the first channels of response to calls regarding domestic violence.

The pandemic altered standard patterns of reporting abuse through structured domestic violence hotlines, with some providers noting an increase, while other providers reporting a noticeable significant decrease in calls. Both events were understood by providers to be concomitant with some form of negative consequence related to IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic. Decreased calls were attributed to greater stalking and control from the part of the abuser, limiting women’s ability to call hotlines. Increased calls were attributed to an increase in frequency and severity of abuse because of greater interaction with one’s partner. These findings were consistent with research revealing similar patterns during the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa. With enforcement of school closures and quarantines during the Ebola outbreak, women experienced more sexual violence and coercion. However, the support services necessary for these traumas were rerouted to help combat spread of the epidemic (John et al., 2020).

Response to catastrophic events prior to COVID-19 gives rise to the claim that crises of such expansive bearings are often left underserviced with regards to gender-based violence and gender inequities (John et al., 2020). These can already be seen in the context of COVID-19. Emerging data shows that since the outbreak of COVID-19, Argentina has seen a 25% increase in emergency DV-related calls, and Singapore has reported a 33% increase in calls to DV hotlines (United Nations, 2020). These findings necessitate diversified channels of interaction (i.e. text/chat/online services) directed toward those who are unable to make conventional phone calls due to either increased surveillance by, or proximity to, their abusive partner.

Nearly all of the service providers in this study highlighted pervasive barriers to delivering effective care and services to immigrant survivors of IPV such as closed community or mobile advocacy services, lack of transportation for survivors, closed court services limiting access to necessary restraining orders, and closed shelters. The cessation of services, as in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, can be deleterious to the well-being and safety of immigrant IPV survivors. Further, survivors mentioned difficulty with newer virtual platforms being used by DV organizations to safely maintain contact with them. Difficulties included fear of the abusive partner, or a complete lack of internet connection or inexperience with technology. Moreover, there were challenges with supporting immigrant survivors who were undocumented and faced additional challenges such as not having work visa and lack of medical insurance. Some survivors and providers conveyed a preference for in-person communication, stressing that in-person services were beneficial for survivors’ well-being and allowed them to leave their home. This barrier needs to be addressed given that maintaining a strong sense of community has been identified as one of the most invaluable foundations to services for IPV. Community is similarly inextricably linked to cultural groups and immigrants within these groups.

Ensuring adequate access to domestic violence and other social services is imperative during the pandemic particularly for marginalized survivors in abusive relationships. Limitations on these services will further increase incidence of IPV and perpetuate cycles of abuse. Programs geared toward community resilience and empowerment have been considered ideal in overcoming heightened risk of IPV in disaster situations, such as disease outbreaks (Norris et al., 2008). The focus is on four adaptive capacities, in the form of economic improvement, social support, communication, and community competence (Norris et al., 2008). A core IPV disaster framework is needed which is directed at mitigating both risks and barriers to receiving support for IPV survivors during crises through collaboration and community (First et al., 2017). The first facet of this framework requires attention on building strong connections with the community and organizations to increase awareness of crisis mediated IPV prevalence and establish basic services for survivors, such as shelter (First et al., 2017). This framework similarly compels safety planning strategies which can be applied to the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure physical and psychological well-being.

This study offers more information to help providers create both effective and culturally appropriate means of reaching survivors of IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ubiquitous nature of COVID-19 and its link to an increase in IPV worldwide necessitate further international research considerations. Future studies could build upon these findings by examining the effectiveness of identified strategies, such as using digital communication and safely communicating with survivors, in countries that have seen an increase in reports and/or severity of IPV. Future research could consider further investigation into the impact the pandemic has had on the ability of service providers to provide adequate care to immigrant survivors both nationally and internationally. Since results identified cultural barriers and risks to receiving care as an immigrant survivor of IPV, additional research is needed to develop and implement culturally tailored strategies to prevent or address IPV in diverse groups of survivors.

There are limitations to this research study which should be acknowledged. The study included only immigrant survivors from some countries of origin and providers serving survivors in specific geographical locations. The findings, therefore, may not be generalizable to organizations in other geographical locations in the US or immigrant women from other countries. Since this study is based on self-report, it is limited by participant’s willingness to share their perspectives on experiences associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the limitations, this study is an important contribution to the literature with its on impact of the pandemic on a marginalized group of survivors (i.e. immigrant women). The perspectives of both providers and survivors from diverse immigrant groups strengthen the study findings.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01MD013863) and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute on Child Health and Human Development (R00HD082350). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Amanor-Boadu Y, Messing JT, Stith SM, Anderson JR, O’Sullivan C, & Campbell JC (2012). Immigrant and nonimmigrant women: Factors that predict leaving an abusive relationship. Violence against Women, 18(5), 611–633. 10.1177/1077801212453139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N & Terry, (2019). Thematic analysis In Liamputtong P (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (1st ed., pp. 843–860). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AM (2020). An increasing risk of family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports, 2, 100089 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra Y, & Shang L (2019). Inductive Coding In Chandra Y, & Shang L (Eds.), Qualitative research using R: A systematic approach (pp. 91–106). Springer; 10.1007/978-981-13-3170-1_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- First JM, First NL, & Houston JB (2017). Intimate partner violence and disasters: A framework for empowering women experiencing violence in disaster settings. Affilia, 32(3), 390–403.1177/0886109917706338 10.1177/0886109917706338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser E (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on violence against women and girls. Ukaid from the Department of International Development. http://www.sddirect.org.uk/media/1881/vawg-helpdesk-284-covid-19-and-vawg.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves M, & Matos M (2016). Prevalence of violence against immigrant women: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Family Violence, 31, 697–710. [Google Scholar]

- Grace D, Johnson C, Reid T (2020). Racial inequality and COVID-19. https://greenlining.org/press/opinion-columns/2020/racial-inequality-and-covid-19/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIzOrMwd-n6wIVsey1Ch25iQ2rEAMYAiAAEgKeHPD_BwE [Google Scholar]

- Holton JA, & Walsh I (2017). Classic grounded theory: Applications with qualitative and quantitative data. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- John N, Casey SE, Carino G, & McGovern T (2020). Lessons never learned: Crisis and gender-based violence. Developing World Bioethics, 20(2), 65–68. 10.1111/dewb.12261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabonesa C, Kindi FI (2020). Assessing the relationship between gender-based violence and COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. https://www.kas.de/documents/280229/8800435/Assessing+the+Relationship+between+Gender-based+Violence=and=the+COVID-19+Pandemic+in+Uganda.pdf/8d5a57a0-3b96-9ab1-a476-4bcf2f71199d?version=1.0&t=1588065638600

- Kaukinen C (2020). When stay-at-home orders leave victims unsafe at home: Exploring the risk and consequences of intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 668–679. 10.1007/s12103-020-09533-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milford M, & Anderson G (2020, April 14). The shadow pandemic: How the Covid19 crisis is exacerbating gender inequality. https://unfoundation.org/blog/post/shadow-pandemic-how-covid19-crisis-exacerbating-gender-inequality/

- Mlambo-Ngcuka P (2020). Violence against women and girls: The shadow pandemic. UN Women. [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Stevens SP, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche KF, & Pfefferbaum RL (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 127–150. 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesch E, Amin A, Gupta J, & García-Moreno C (2020). Violence against women during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.).), 369, m1712 10.1136/bmj.m1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri B, Campbell JC, & Messing JT (2018). Intimate partner homicides in the United States, 2003–2013: A comparison of immigrants and non-immigrants. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1.–. 10.1177/0886260518792249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri B, Nnawulezi N, Njie-Carr V, Messing J, Ward-Lasher A, Alvarez C, & Campbell JC (2018). Multilevel risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence among African, Asian and Latina immigrant and refugee women: Perceived needs for safety planning interventions. Race and Social Problems, 10(4), 348–365. 10.1007/s12552-018-9247-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, Norris FH, Tracy M, Clements K, & Galea S (2010). Intimate partner violence and Hurricane Katrina: Predictors and associated mental health outcomes. Violence and Victims, 25(5), 588–603. 10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SocioCultural Research Consultants L (2019). Dedoose: Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data [computer software]. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2020). Policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women. United Nations; https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/policy_brief_on_covid_impact_on_women_9_apr_2020_updated.pdf [Google Scholar]

- van Gelder N, Peterman A, O’Donnell M, Potts A, Thompson K, Shah N, & Oertelt-Prigione S (2020). COVID-19: Reducing the risk of infection might increase the risk of intimate partner violence. EClinical Medicine the Lancet, 21, 1–2. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman A, & Behrman JA (2016). Disaster, Disruption to family life, and intimate partner violence: The case of the 2010 Earthquake in Haiti. Sociological Science, 3(9), 167–189. 10.15195/v3.a9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, South African Medical Research Council, & Department of Reproductive Health and Research. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization; https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/9789241564625_eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]