Summary

Background

Platelets are increasingly recognized as immune cells. As such, they are commonly seen to induce and perpetuate inflammation, however, anti-inflammatory activities are increasingly attributed to them. Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory condition. Similar to other inflammatory conditions, the resolution of atherosclerosis requires a shift in macrophages to an M2 phenotype, enhancing their efferocytosis and cholesterol efflux capabilities.

Objectives

To assess the effect of platelets on macrophage phenotype.

Methods

In several in vitro models employing murine (RAW264.7 and bone marrow derived macrophages) and human (THP-1 and monocyte-derived macrophages) cells, we exposed macrophages to media in which non-agonized human platelets were cultured for 60 minutes (platelet conditioned media; PCM) and assessed the impact on macrophage phenotype and function.

Results

Across models, we demonstrated that PCM from healthy humans induced a pro-resolving phenotype in macrophages. This was independent of Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 6 (STAT6), the prototypical pathway for M2 macrophage polarization. Stimulation of the EP4 receptor on macrophages by PGE2 present in PCM, is at least partially responsible for altered gene expression and associated function of the macrophages – specifically reduced peroxynitrite production, increased efferocytosis and cholesterol efflux capacity, and increased production of pro-resolving lipid mediators (i.e., 15R-LXA4).

Conclusions

PCM induces an anti-inflammatory, pro-resolving phenotype in macrophages. Our findings suggest that therapies targeting hemostatic properties of platelets, while not influencing pro-resolving, immune-related activities, could be beneficial for the treatment of atherothrombotic disease.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Inflammation, Macrophages, Platelets, Prostaglandin E2

1. Introduction

Beyond their crucial role in hemostasis, platelets are garnering increasing recognition as immune cells. Within this context, platelets have most frequently been seen as inducers of inflammation [1]. However, there are increasing reports that document critical effects of platelets in curtailing inflammation both in vitro and in vivo [2–4].

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by inflammatory macrophages recruited to plaques rich in inflammatory oxidized lipid in the arterial intima [5]. A multitude of factors, including lipoprotein lipase activity [6], act to retain the oxidized lipids within the vessel wall and expand plaques. Further, metabolism of arginine by macrophage nitric oxide synthase induced in inflammation can result in peroxynitrite production, which may mediate oxidation of low density lipoprotein [7], further exacerbating atherosclerosis [8]. As atherosclerosis progresses, inadequate efferocytosis of apoptotic cells by plaque macrophages leads to necrosis and a “vulnerable plaque,” prone to rupture and precipitating the feared atherothrombotic complications of myocardial infarction or stroke [9]. We have previously shown that platelets interact with macrophages preferentially within atherosclerotic plaques [10, 11], suggestive of the potential for these cells to influence plaque macrophage phenotype.

The resolution, or regression, of atherosclerosis is a far less well understood phenomenon than its progression. However, it is known to require a number of processes, including the removal (efflux) of cholesterol from established plaques in a process mediated by apolipoproteinA1 (apoA1)-containing particles [12], as well as a phenotypic switch of plaque macrophages to a pro-resolving phenotype [13, 14]. In this context, enhanced efferocytosis may achieve further atherosclerosis resolution and reduce plaque vulnerability to rupture.

In this report, we show that platelet conditioned media (PCM), through EP4 activation by PGE2, is responsible for a number of anti-inflammatory phenotypic changes in macrophages in vitro that are associated with in vivo atherosclerosis regression. As we discuss, these findings are also potentially relevant to thrombosis, and suggest targeting hemostatic properties of platelets, while not influencing their pro-resolving immune-related activities, could be beneficial for the treatment of atherothrombotic disease broadly.

2. Methods

2.1. Platelet conditioned media preparation

Healthy volunteers underwent phlebotomy with 19 gauge needles without the use of tourniquets into sodium citrate-containing tubes (BD Vaccutainer, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Washed platelets were isolated as previously described [10, 15]. In short, blood collected in tubes containing sodium citrate was centrifuged (200g × 10min) to obtain platelet-rich plasma (PRP). PRP was centrifuged (1000g × 10min) and the platelet pellet resuspended in Tyrode’s buffer (139mM NaCl, 3mM KCl, 17mM NaHCO3, 12mM glucose, 3mM CaCl2, 1mM MgCl2). Platelets were then counted on a XN-V Hematology Analyzer (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan), centrifuged again at 1000g × 10min, and the Tyrode’s buffer supernatant was removed. Washed platelets were then resuspended in RPMI 1640 at a concentration of 1×106 platelets/μL. Platelets were kept at 37°C for 60 minutes and then centrifuged at 2500g × 5 min. The supernatant was removed and passed through a 220nm filter. The filtered supernatant (platelet conditioned media – PCM) was then employed in experiments as described below. Approximately 50–60% of platelets used in making PCM exhibited surface P-selectin at the completion of the protocol.

2.2. Cell culture

RAW 264.7 and J774A.1 murine macrophages, THP-1 human monocytes and Jurkat cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained in RPMI 1640 + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) + 1U/mL penicillin and 1μg/mL streptomycin at passage <20.

Bone marrow was isolated from the tibias and femurs of 8–12 week old C57BL/6J and STAT6−/− mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Following erythrocyte lysis with red blood cell lysis buffer (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), cells were plated in DMEM (1g/L glucose) containing 10% FBS and 10ng/mL recombinant murine macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF, Peprotech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ). Media was replenished every two days. Experiments were performed on day 7.

THP-1 cells were differentiated to macrophages with exposure to 5ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) for 48 hours. The cells were then washed and rested in RPMI 1640 + 10% FBS + 1U/mL penicillin and 1μg/mL streptomycin with media replenishment every two days. Experiments were performed on day 7.

Blood from healthy human donors was collected with EDTA as an anticoagulant. Buffy coats were isolated using SepMate® PBMC Isolation tubes (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver CANADA) and Ficoll® Paque (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Negative selection for monocytes was performed using Human Monocyte Isolation kits (Miltenyi Biotec, Gergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to manufacturer instructions. Monocytes were placed on multi-well cell culture dishes in monocyte attachment medium for two hours. Monocyte attachment medium was then aspirated, cells washed thrice with monocyte attachment medium and then cultured in macrophage differential medium + 50ng/mL recombinant human M-CSF (Peprotech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ) with media replenishment every two days. Experiments were performed on day 7.

Cells were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination during the course of experimentation.

2.3. Co-incubation experiments

Sixteen hours prior to gene expression experiments in RAW264.7 cells, cells were serum starved by culturing in media containing 0.2% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Macrophages were then exposed to experimental conditions (with exceptions noted below) for six hours. In treatments of macrophages with PCM, the concentration of PCM used corresponded to a platelet:macrophage of approximately 250:1 (1.5×108 platelets/mL) as initial dose response experiments (Supplemental Figure 1) demonstrated that this ratio was adequate to demonstrate a robust and reproducible gene expression response, while also limiting the amount of PCM required in the assays. This ratio also falls within the normal range for the ratio of platelets and monocytes in human circulation. IL-4 (Peprotech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ) was used at a concentration of 100pg/mL. Other cell types (bone marrow-derived macrophages – BMDMs, differentiated THP-1 cells and human monocyte-derived macrophages) were not serum starved prior to PCM exposure.

For prostaglandin E (PGE) receptor antagonist experiments, RAW264.7 cells were exposed to 25μM GW627368X (EP4 antagonist; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), 25μM AH6809 (EP2 antagonist; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), or equivalent volume of DMSO control for 60 minutes prior to experimental treatments. For PGE2 blocking antibody experiments, media containing 5ug/mL PGE2 monoclonal antibody (Cat #10009814; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) or control IgG (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) was incubated ± PCM at 37°C for 60 minutes. This media containing PCM and antibody was then employed in assays as described below.

2.4. Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from macrophages using TRIzol (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and Direct-zol MiniPrep (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) according to manufacturer instructions. Reverse transcription was performed with the Verso cDNA kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Fast SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mix was then used according to manufacturer’s instructions to quantify expression of several transcripts of interest in cDNA on a QuantStudio 7 Flex (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) quantitative PCR machine. Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Tables 1a and 1b.

2.5. SiRNA transfection

Cells were transfected with SiGenome siRNA pools (control scrambled siRNAs, mouse Ptger4; Dharmacon, Walthan, MA) using DharmaFECT 4 Transfection Reagent in Optim-MEM media (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for 60 hours according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The efficiency of the knockdown was assessed by RT-qPCR.

2.6. Peroxynitrite assay

RAW264.7 cells were treated ± PCM/IL4/blocking antibodies for 8 hours. Media was aspirated and cells washed with PBS. Cells were then treated with 1ug/mL lipopolysaccharide + 50ng/mL interferon gamma for 14 hours. Media was replaced with phenol red-free media containing peroxynitrite probe for one hour. Cells were washed and live cell confocal imaging with a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) 880 confocal microscope was performed at 474nm and 574nm. The amount of peroxynitrite produced was quantified as described (Chen et al., under review).

2.7. Efferocytosis and flow-cytometry

RAW264.7 cells and human monocyte-derived macrophages were treated ± PCM for 16 hours. Media was aspirated and cells washed with PBS. Jurkat cells were irradiated with UV light for 15 minutes followed by incubation under normal culture conditions for 3 hours. During the third hour of incubation, cells were labeled with CypHer5E NHS ester (GE Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA). Cells were washed twice with PBS, suspended in RPMI + containing 0.2% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and applied to macrophages at 5:1 Jurkat:macrophage for 40 minutes. Media was aspirated and cells were washed with ice-cold PBS. Macrophages were labeled with FITC anti-CD11b antibody (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) for 45 minutes, washed and analyzed with a LSRII HTS (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ) flow cytometer. Macrophages were first selected with CD11b, from which the CypHer5 positive events (efferocytotic events) were selected. Data analysis was performed using Flow Jo version 10.4.2.

2.8. Cholesterol efflux assay

J774A.1 cells were incubated with 1μCi/mL 3H-labeled cholesterol and 50μg/mL acetylated LDL (Alfa Aesar, Tewksbury, MA) for 24 hours. Cells were washed and then exposed to serum-free RPMI ± PCM (± PGE2 antibody) overnight. Cells were washed with PBS and then exposed to 50μg/mL apoA1 (Alfa Aesar, Tewksbury, MA) for 4 hours. Liquid scintillation counting was then used to quantify the percentage of radiolabeled cholesterol present in the apoA-1-containing fraction.

2.9. Lipid mediator identification and quantification by LC-MS/MS

PCM prepared in phenol red-free media was added to 100% methanol (1:2) and stored at −80°C. Similarly, phenol red-free media from RAW264.7 cells exposed to PCM +/− PGE2 antibody for 6 hours was added to 100% methanol and stored at −80°C. These samples were then subjected to solid-phase extraction followed by targeted LC-MS/MS analysis as previously described in detail [16]. Extraction recovery was aided by deuterium-labeled internal standards for each chromatographic region including d4-PGE2 and d5-LXA4 (Cayman Chemical), and lipid mediators were identified and quantified using multiple reaction monitoring transitions and full MS/MS spectra as compared with authentic external standards (Supplemental Figure 3). For visualization, a heatmap of all identified lipid mediators was constructed using Metaboanalyst (www.Metaboanalyst.ca). For this, a missing value imputation was first performed followed by a generalized log transformation and autoscaling. Finally, Ward clustering algorithm and Euclidean distance measures was applied to data. The resulting heatmap illustrates the relative change in abundance of individual mediators across each experimental condition.

2.10. Statistical analyses

All results constitute data derived from at least three independent experiments. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyzes were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was pre-specified as p<0.05. Analyses included 1-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc two-tailed Student’s t-tests, unpaired two-tailed t-tests, and Pearson’s product moment correlations.

3. Results

3.1. Platelet conditioned media exposure alters macrophage gene expression

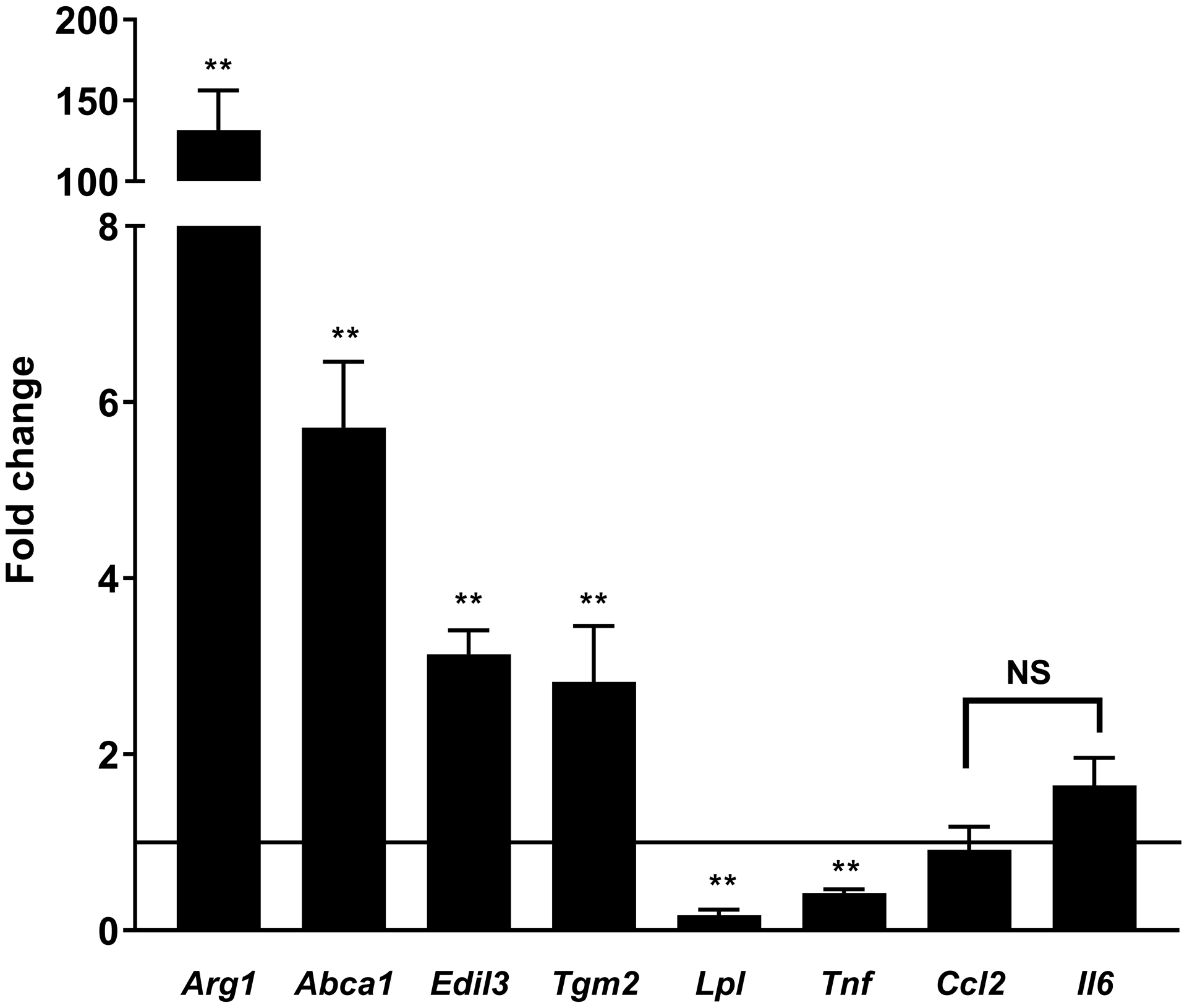

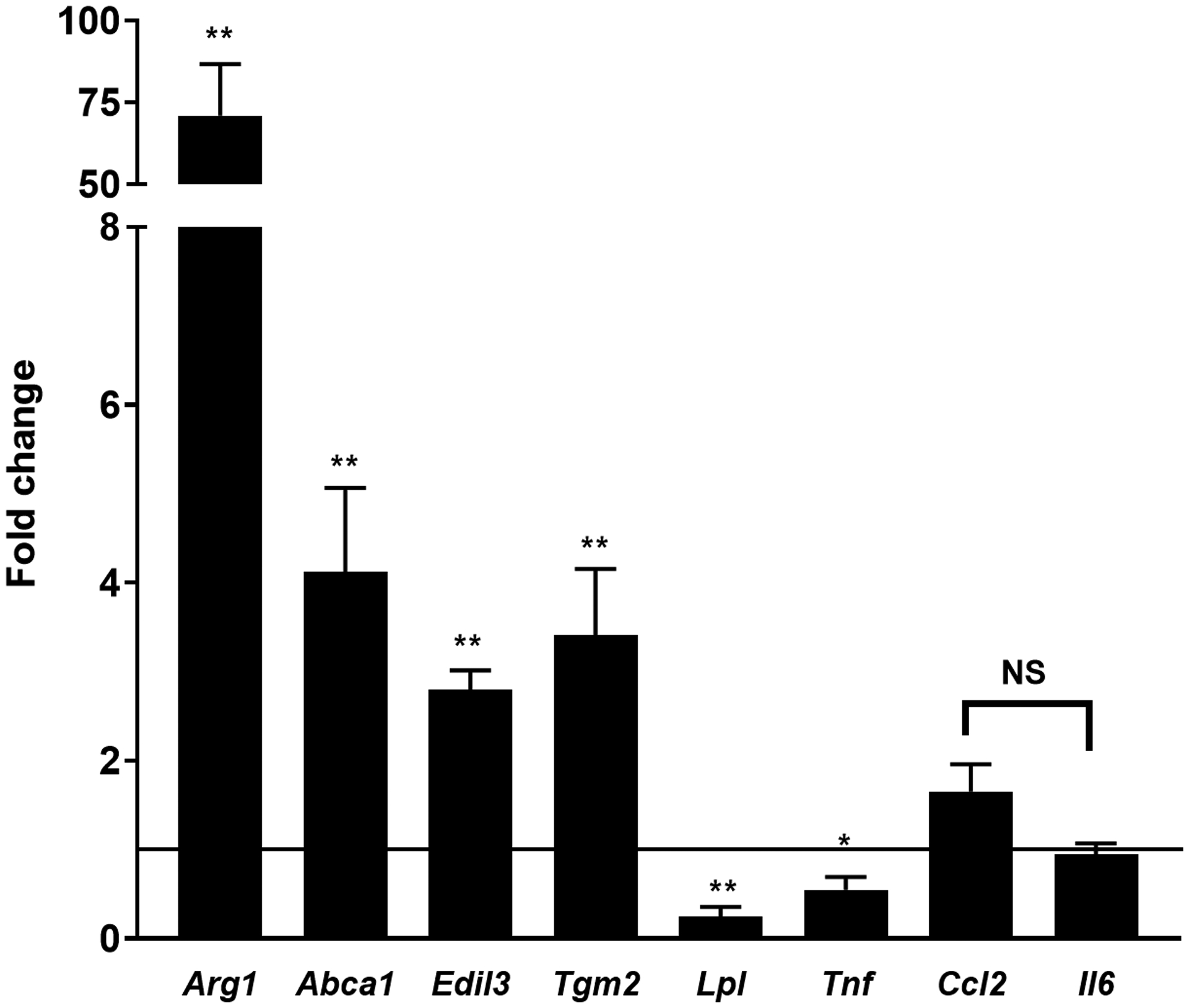

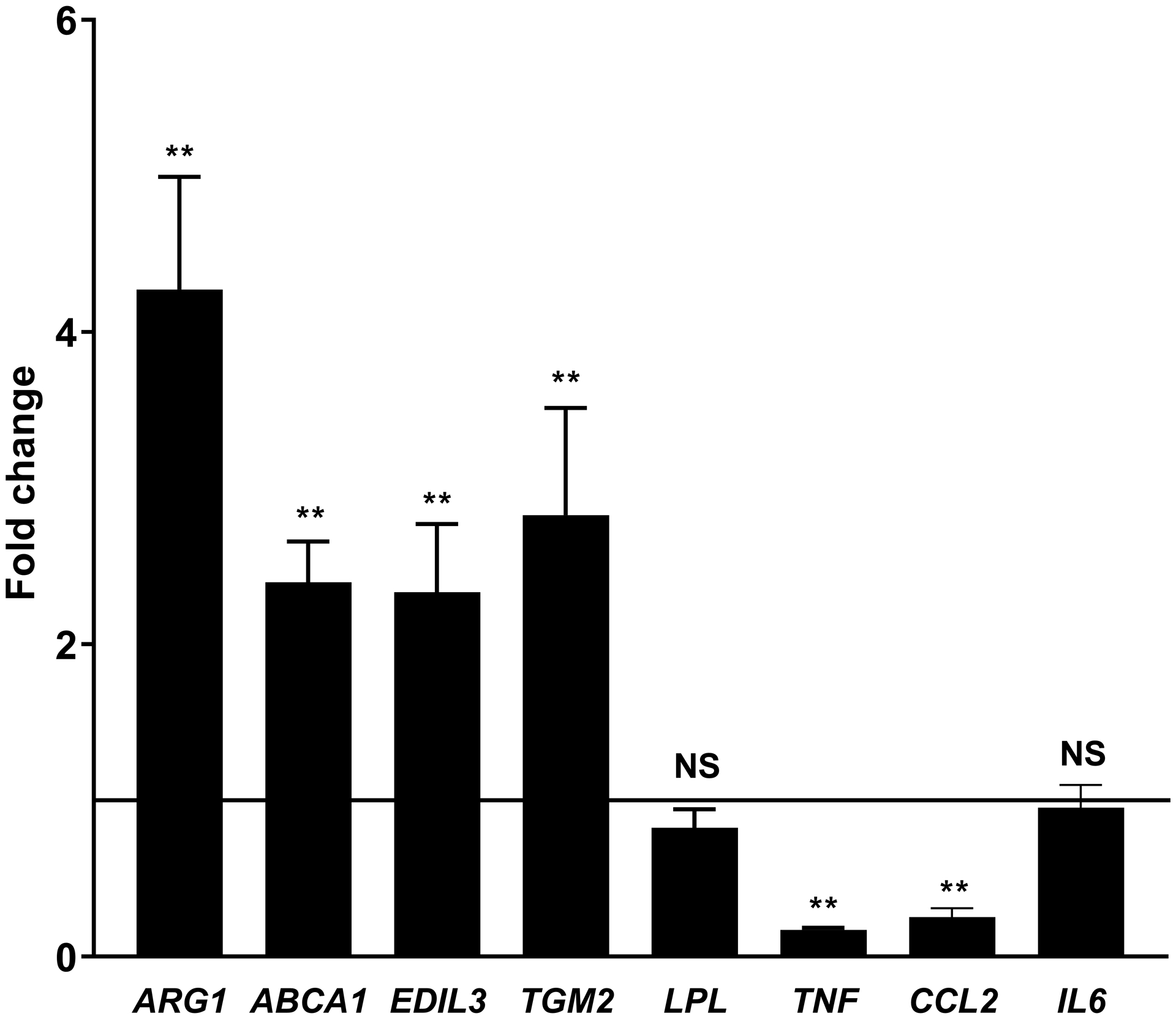

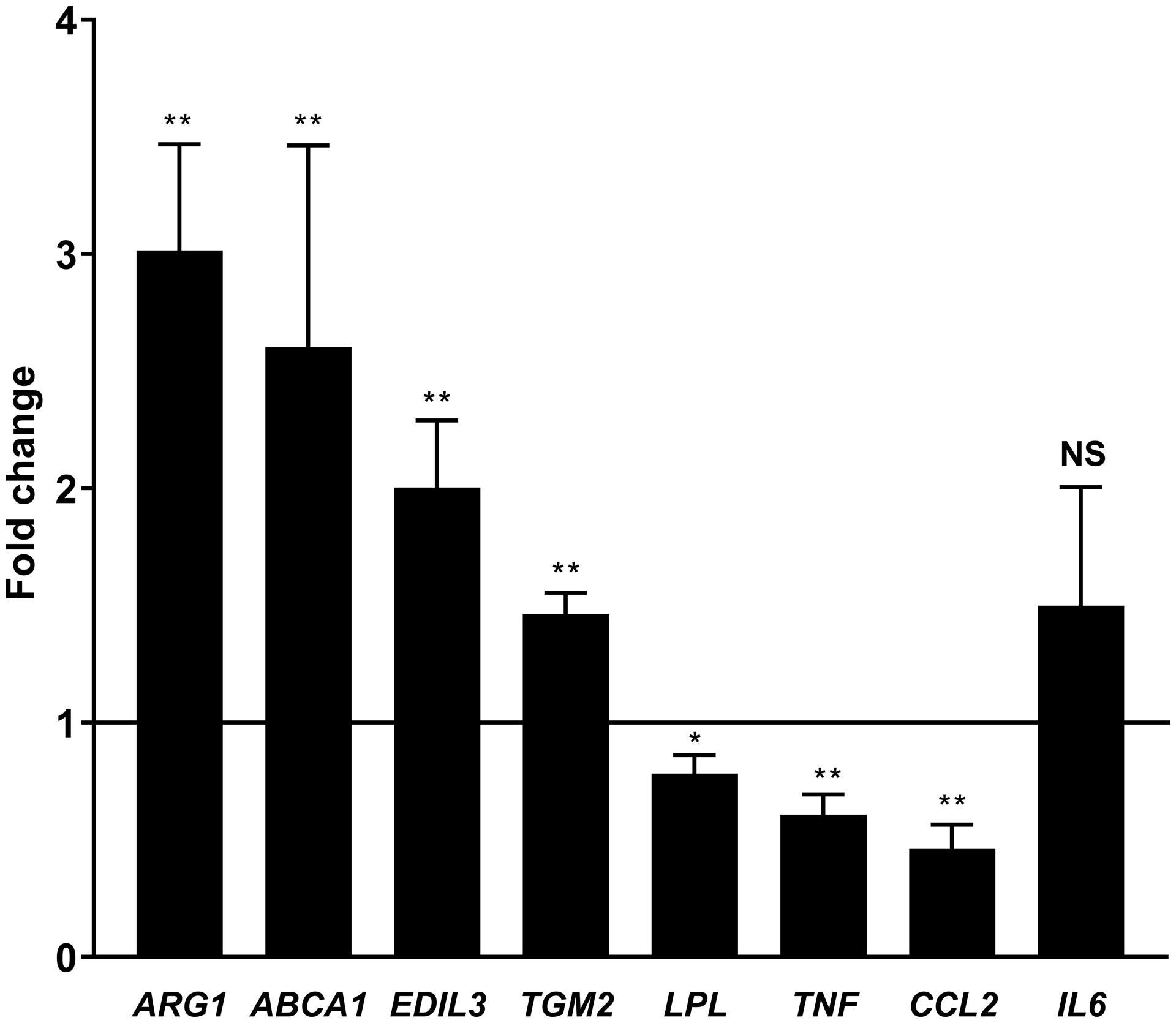

Platelets [2, 4] and the products of platelet activation [2, 17] suppress TNFα and stimulate Arg1 expression in macrophages. We replicated these findings in our system exposing mouse (RAW267.4 and BMDMs), and human macrophages (differentiated THP-1 cells and monocyte-derived macrophages) to PCM. In the absence of a polarizing stimulus, we found expression of Tnf and Arg1 to be altered similarly to previous reports (Figures 1A–D). Additionally, Tgm2, Abca1, and Edil3 expression were upregulated and Lpl downregulated, without significant changes in Il6 expression (Figures 1A–D). Ccl2 (Mcp1) was unchanged in murine-origin cells, whereas it was downregulated in human cells (Figures 1C and 1D).

Figure 1. Platelet conditioned media (PCM) exposure alters macrophage gene expression.

RAW264.7 cells (A), C57BL/6 murine bone-marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) (B), differentiated THP-1 cells (C), and human monocyte-derived macrophages (D) were cultured with the addition of PCM for six hours and mRNA expression of multiple genes of interest was quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 5 – 8 independent experiments). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare treated and untreated conditions. NS = not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

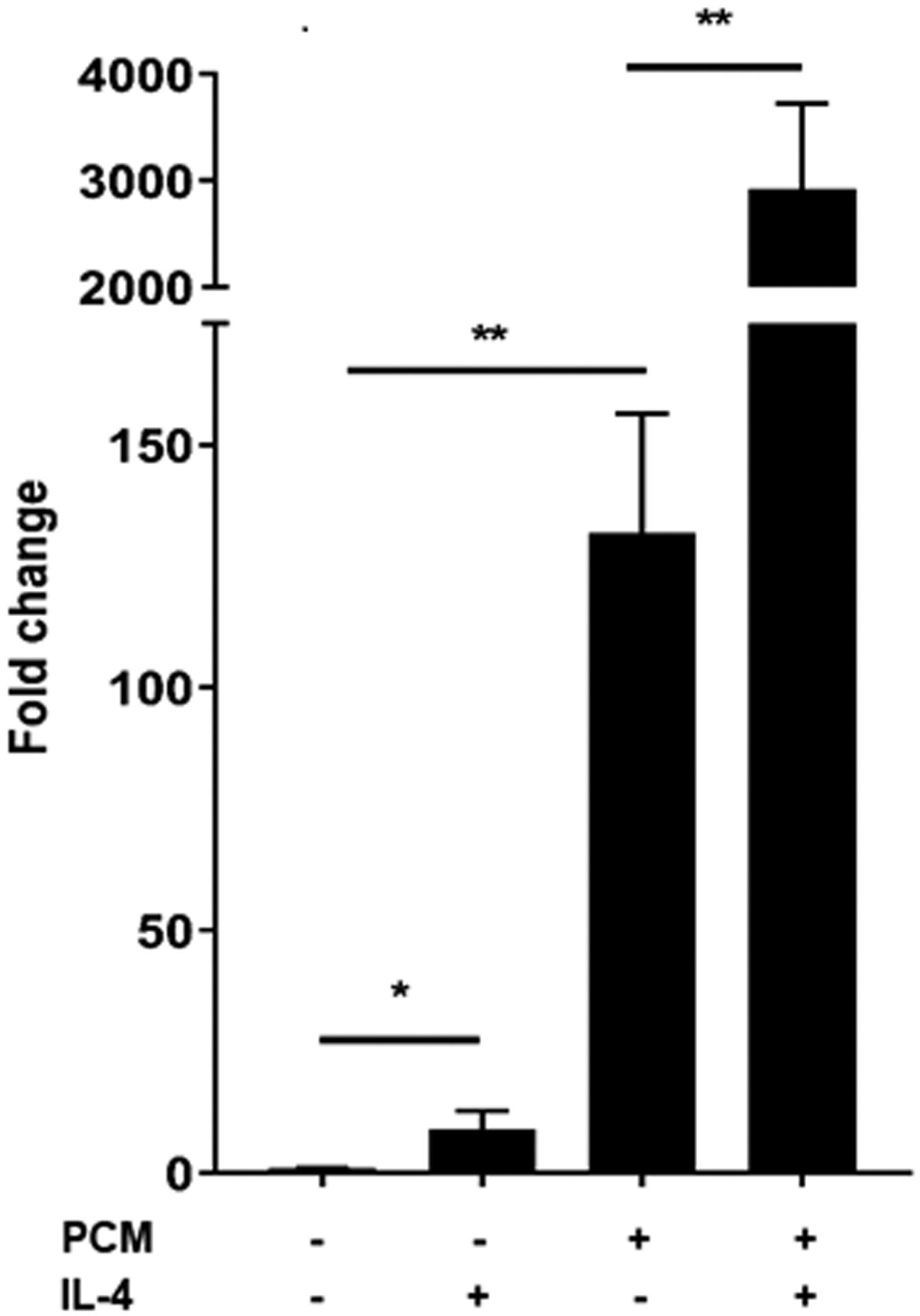

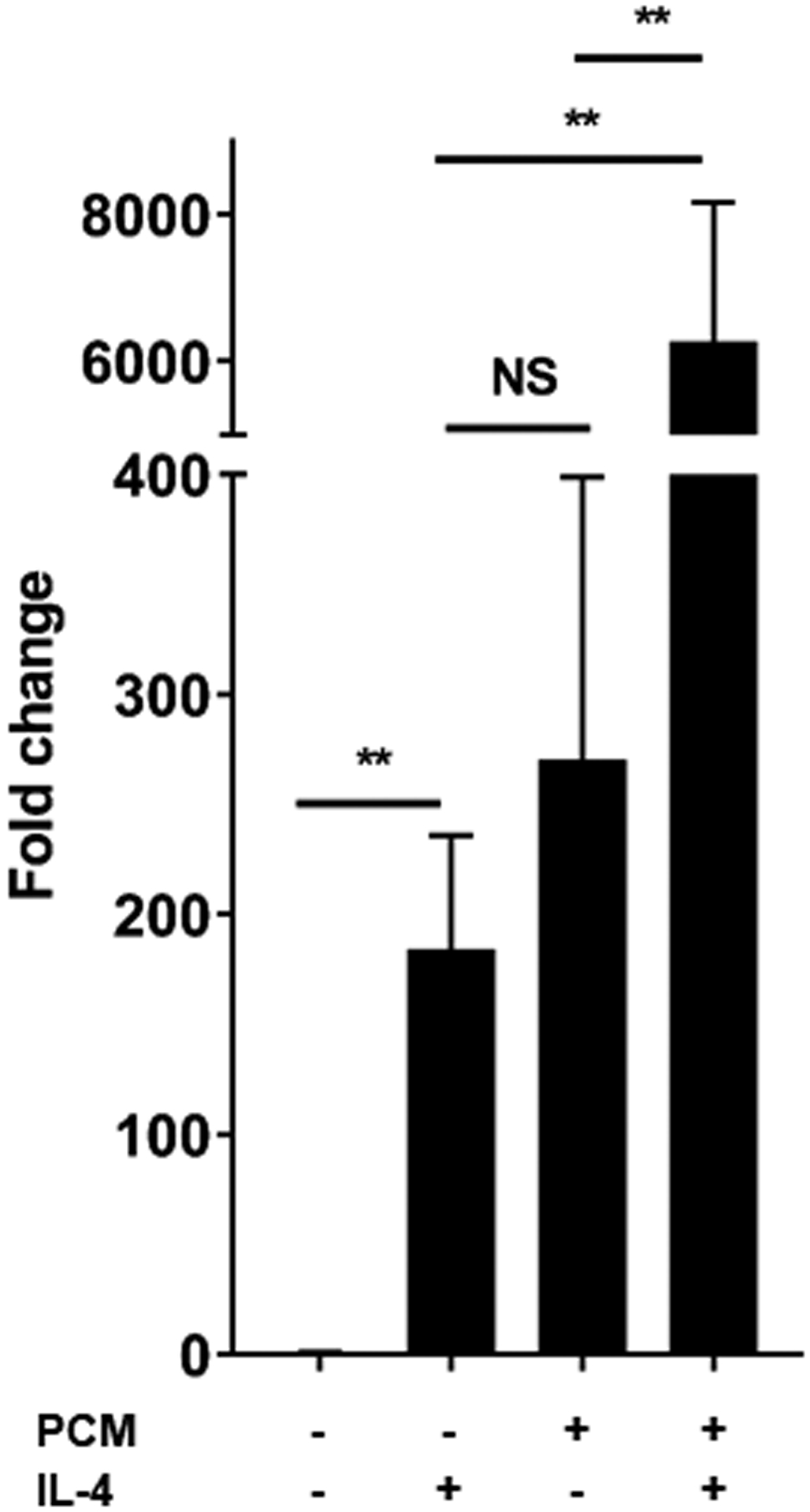

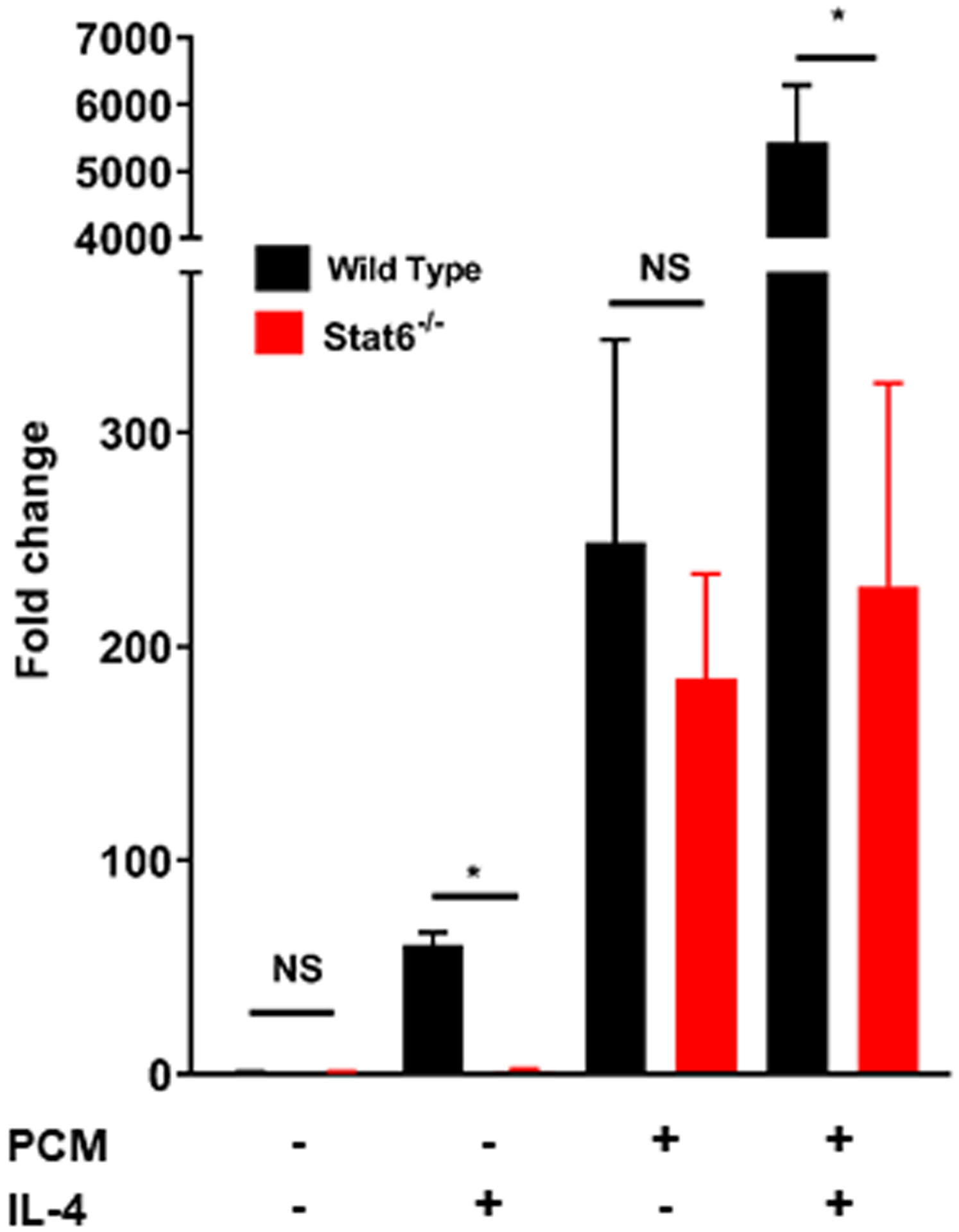

Arg1 and Tgm2 are two markers of an M2 macrophage phenotype [18]. IL4, the prototypical stimulus for M2 polarization, acts through STAT6 [19]. We found that treatment with PCM and IL4 had a more than additive impact on expression of Arg1, but not Tgm2 or other genes that we found modulated by PCM (Figures 2A–B, Supplemental Figure 2). The increase in Arg1 on exposure to PCM was no different in BMDMs from WT or STAT6−/− mice, indicating that the modulation of Arg1 by PCM is not mediated through STAT6 (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Platelet conditioned media (PCM) exposure further enhances Arg1 expression induced by IL-4 in a STAT6-independent manner.

RAW264.7 cells (A) and bone-marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) (B) were cultured with the addition of PCM and/or IL-4 (100pg/μL) for six hours and mRNA expression of Arg1 was quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 6 independent experiments). (C) BMDMs from STAT6−/− and wild type (C57BL/6) mice were cultured with the addition of PCM and/or IL4 (100pg/μL) for six hours and mRNA expression of Arg1 was quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 3 independent experiments). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. 1-way ANOVA was used, followed by post-hoc two-tailed Student’s t-tests, to compare treatment conditions. NS = not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

3.2. Stimulation of prostaglandin E receptor 4 (EP4) is responsible for altered gene expression in platelet conditioned media-exposed macrophages

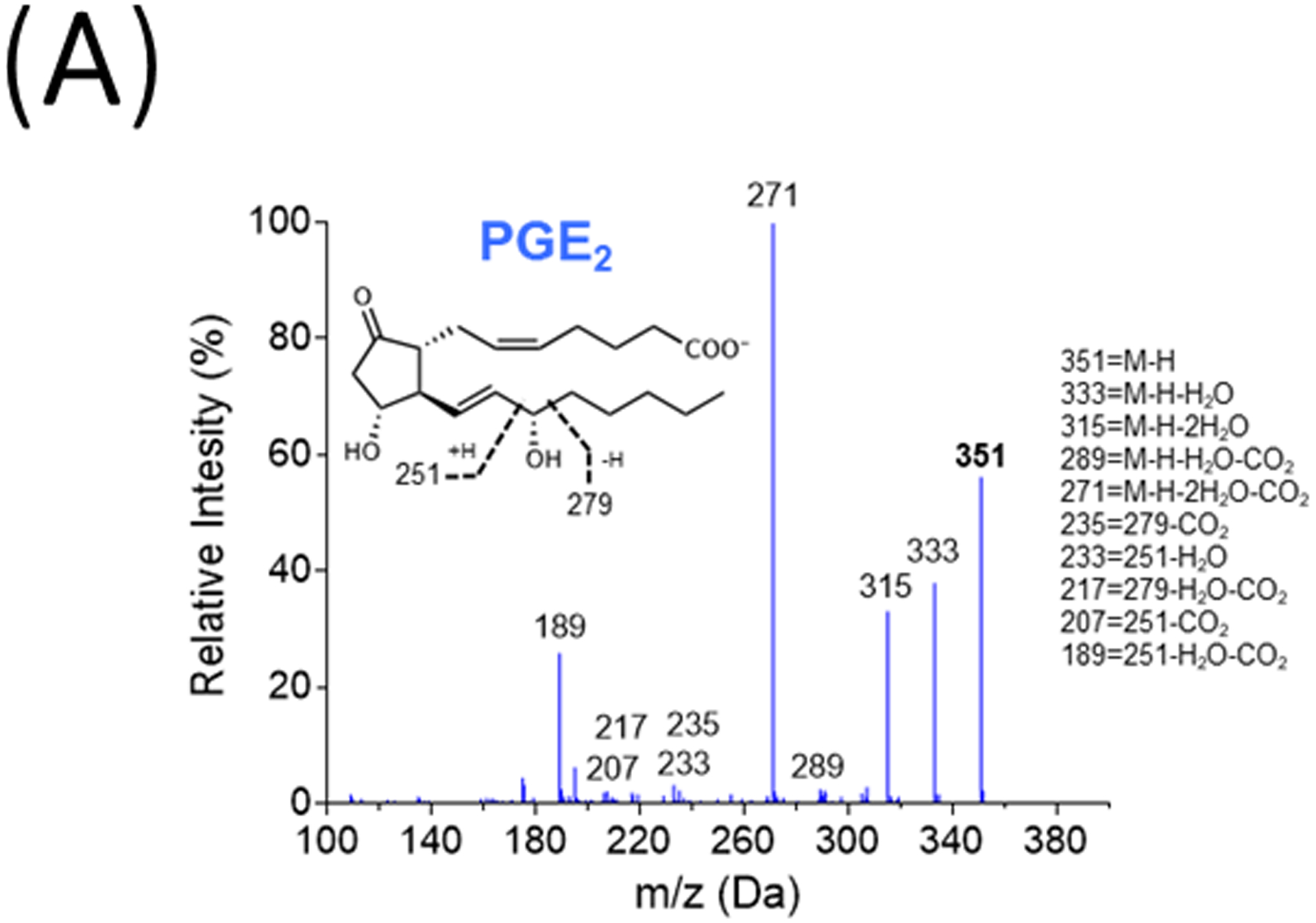

We then began to investigate how PCM mediated its effects on macrophage gene expression. Neither proteolysis, nor boiling, of PCM altered the effect of PCM on macrophage gene expression (data not shown), so we investigated non-protein species known to be released from platelets. Prior reports had implicated products of the COX1 pathway in the suppression of TNFα expression [2]. Further, recent work has increasingly implicated PGE2 as having inflammation-resolving effects [20, 21], despite its traditionally pro-inflammatory association. We thus quantified PGE2 in PCM, correlating the amount with expression of Arg1 (with and without IL4 co-treatment), Tnf, and Abca1 in RAW267.4 cells exposed to the PCM. Using targeted LC-MS/MS, we identified PGE2 (Figure 3A) and found that its concentration in PCM (~100–200pM) prepared from multiple subjects was similar to those previously reported to induce M2 macrophage polarization [22]. Further, concentrations of PGE2 in PCM significantly correlated with expression of these genes (Arg1, r=0.87; Tnf, r=−0.76; Abca1, r=0.75; p<0.01 for each comparison).

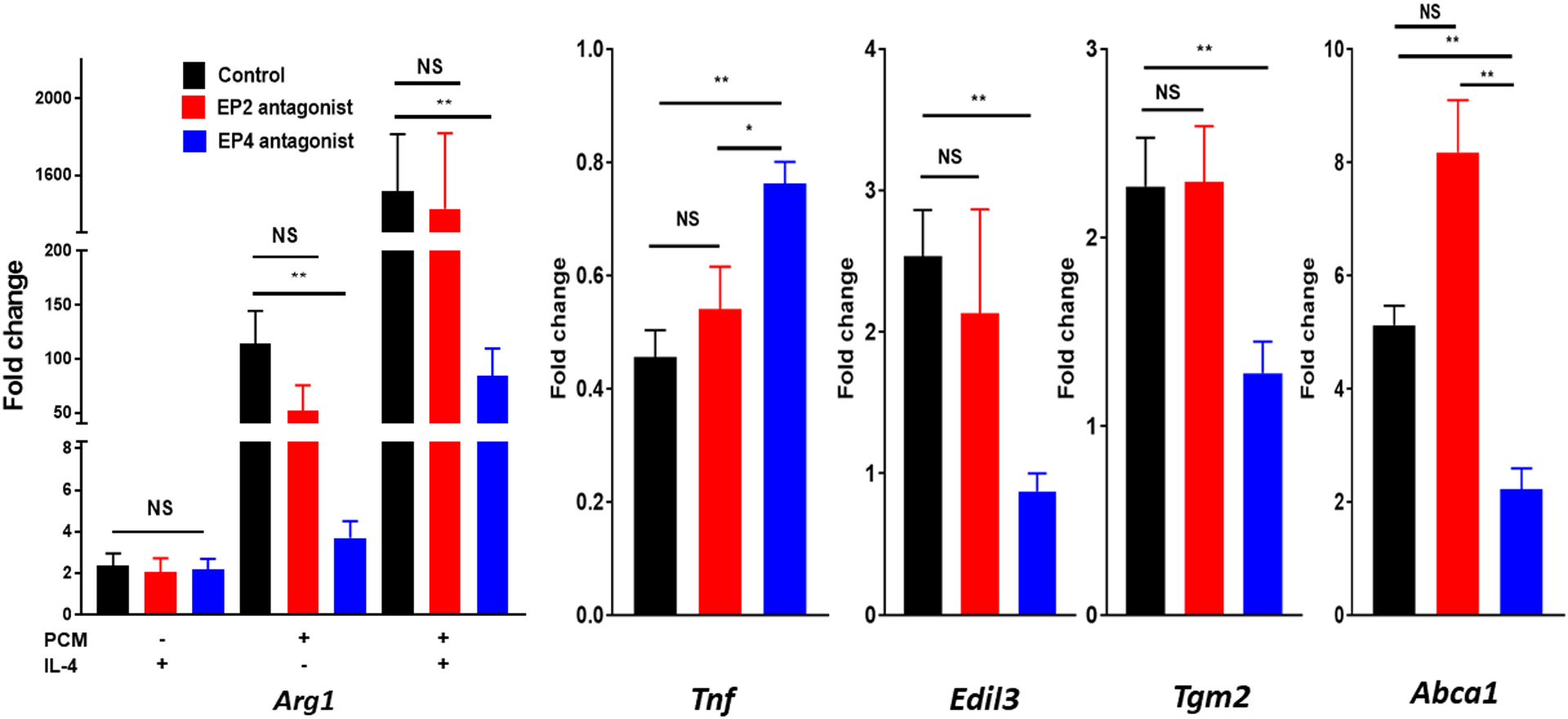

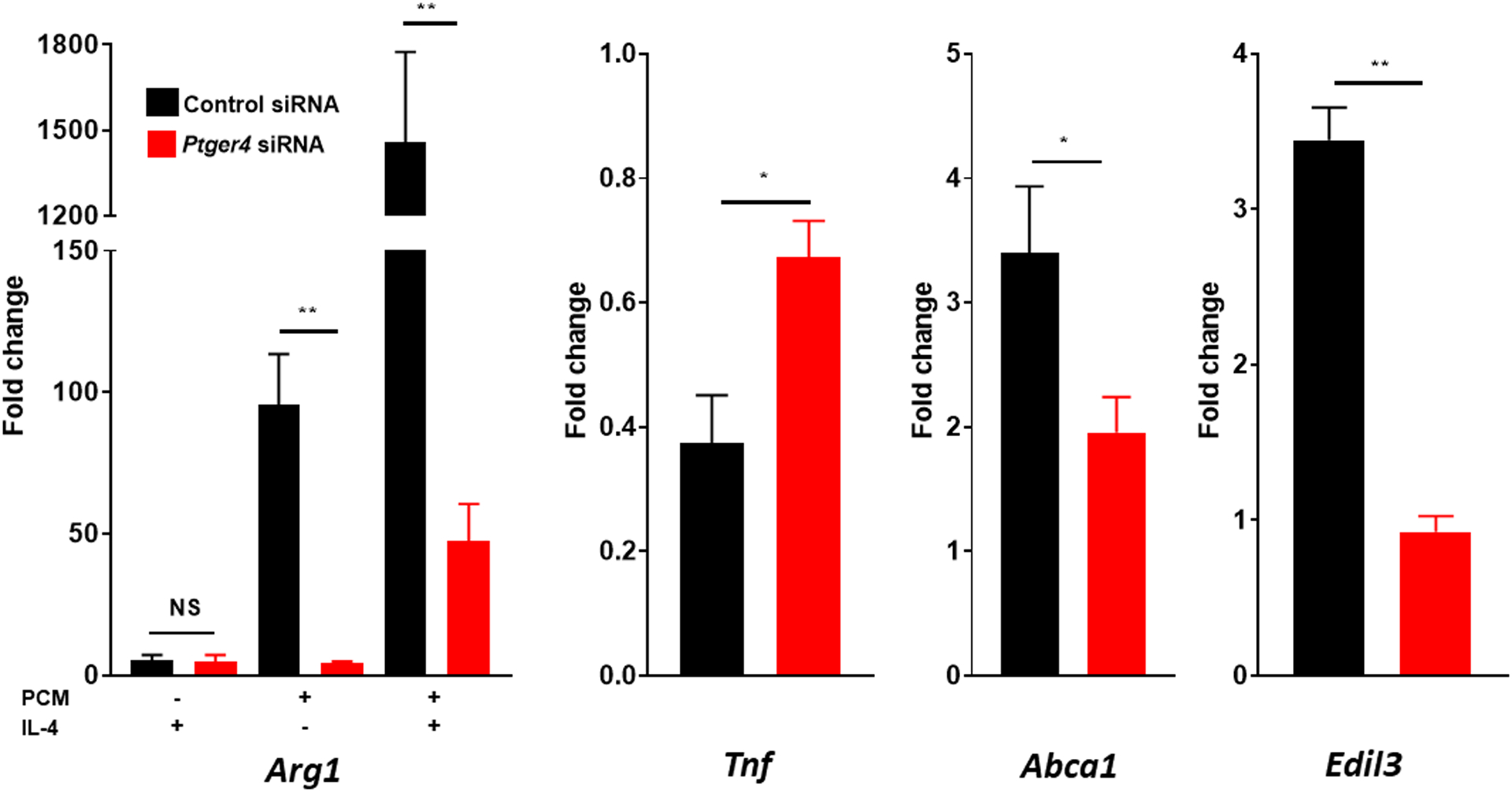

Figure 3. Platelet conditioned media (PCM)’s activities in altered macrophage gene expression are partially mediated through the EP4 receptor.

(A) Representative MS/MS spectra of PGE2 diagnostic ion assignments and structure. RAW264.7 cells (B) were cultured with 25μM GW627368X (EP4 antagonist), 25μM AH6809 (EP2 antagonist), or equivalent volume of DMSO control for 60 minutes, or (C) were transfected with SiGenome siRNA pools (control scrambled siRNAs, mouse Ptger4), prior to PCM ± IL4 exposure for six hours. mRNA expression of multiple genes of interest was then quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 4 independent experiments). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. 1-way ANOVA was used, followed by post-hoc two-tailed Student’s t-tests, to compare treatment conditions. NS = not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

PGE2 can activate four different G protein-coupled receptors (EP1 – EP4) which mediate separate intracellular effects. As previous work had implicated activation of EP4 in the suppression of TNFα expression [2], we employed both antagonists to EP4, as well as EP2, and found that only GW627368X, a specific EP4 antagonist, suppressed the effect of PCM on macrophage gene expression (Figure 3B). To further demonstrate that PCM mediates its effects on macrophage gene expression through PGE2’s stimulation of EP4, we also employed siRNA to the gene coding for EP4 (Ptger4) and were able to eliminate the alterations in macrophage gene expression induced by PCM (Figure 3C).

3.3. Prostaglandin E2 in platelet conditioned media induces pro-resolving functions in macrophages

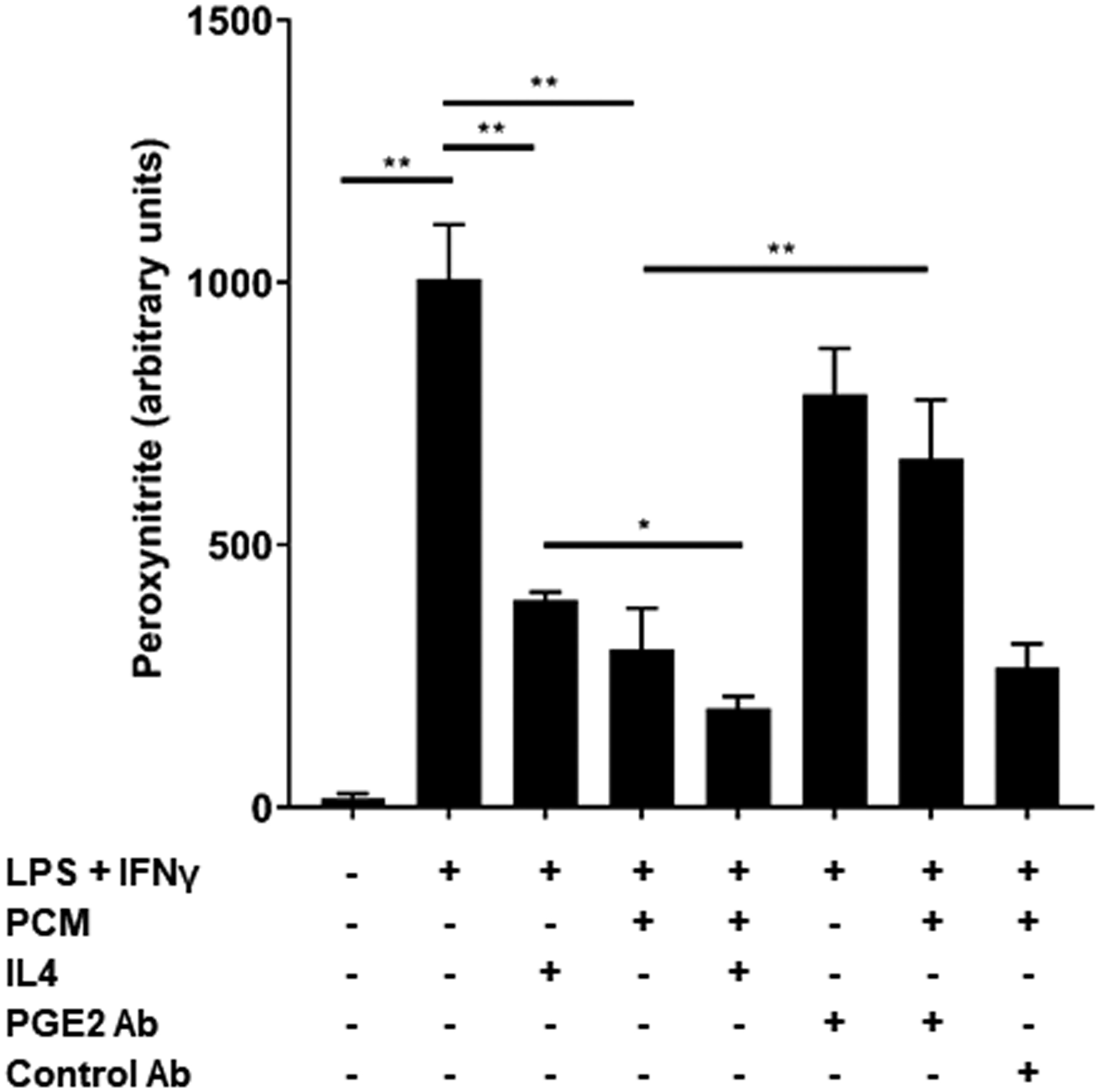

Arginase 1 (the product of Arg1) competes with nitric oxide synthase for arginine and greater concentrations of arginase 1 are associated with reduced nitric oxide formation [23]. Peroxynitrite, produced from nitric oxide and superoxide anion, is responsible for the oxidative cellular damage and vascular pathology attributed to these free radicals [24]. We exposed macrophages to a stimulus known to elicit nitric oxide production (lipopolysaccharide + interferon γ). We found a >65% reduction in peroxynitrite in RAW264.7 cells that had first been exposed to PCM, with increased effect (~75%) with IL4 co-treatment (Figure 4A). This effect was significantly impaired by the addition of an antibody to PGE2 to PCM prior to macrophage exposure.

Figure 4. Platelet conditioned media (PCM) exposure induces changes in macrophage function congruent with altered gene expression.

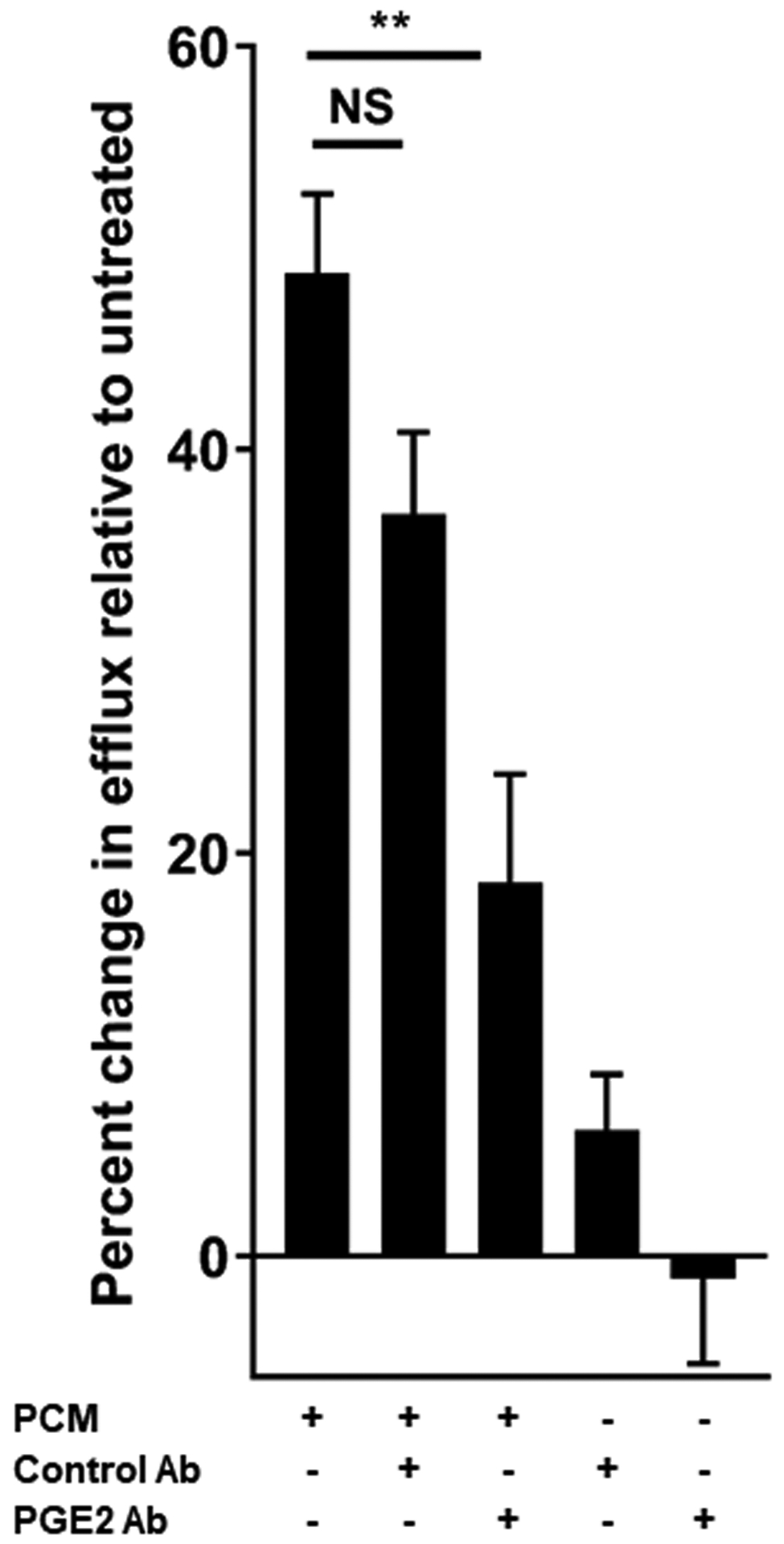

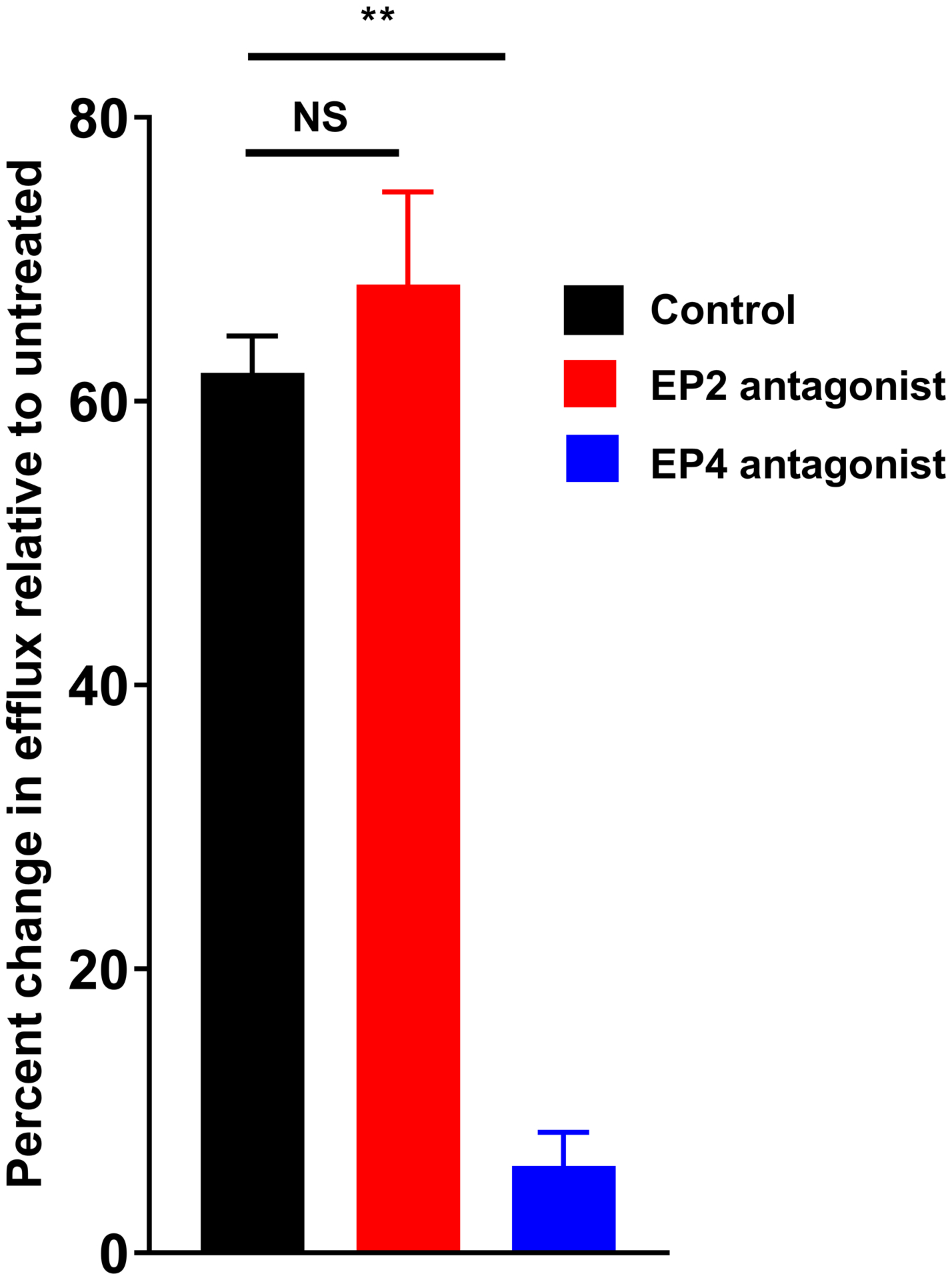

(A) RAW264.7 cells were exposed to PCM for eight hours prior to exposure to 1ug/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) + 50ng/mL interferon gamma (IFNγ) for 14 hours. Peroxynitrite probe was added and live cell confocal imaging was performed to quantify peroxynitrite (n = 5 independent experiments). (B) J774A.1 cells were incubated with 3H-labeled cholesterol and acetylated LDL for 24 hours. Cells were then exposed to PCM (± PGE2 antibody) overnight and then cultured with 50μg/mL apoA1 for 4 hours. Liquid scintillation counting quantified the percentage of 3H-labeled cholesterol present in the apoA1-containing fraction (n = 3 independent experiments). (C) These experiments were also performed with the inclusion of EP receptor antagonists, exposure beginning one hour prior to PCM exposure. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. 1-way ANOVA was used, followed by post-hoc two-tailed Student’s t-tests, to compare treatment conditions. NS = not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Efflux of cholesterol from plaques to apoA1-containing particles is also necessary for the regression of atherosclerosis [12]. Cholesterol efflux to nascent HDL occurs predominantly via ABCA1. Consistent with prior reports of PGE2 increasing ABCA1 expression in THP-1 cells [25] and cholesterol efflux from J774 cells [26], and in line with the upregulation of Abca1 we observed, we found that exposure to PCM increased cholesterol efflux from macrophages to apoA1 more than 50% relative to cells not exposed to PCM (Figures 4B and 4C). This effect was largely impaired by pre-incubation of PCM with a PGE2-blocking antibody (Figure 4B). The presence of an EP4-, but not an EP2-, antagonist also suppressed the change in cholesterol efflux (Figure 4C).

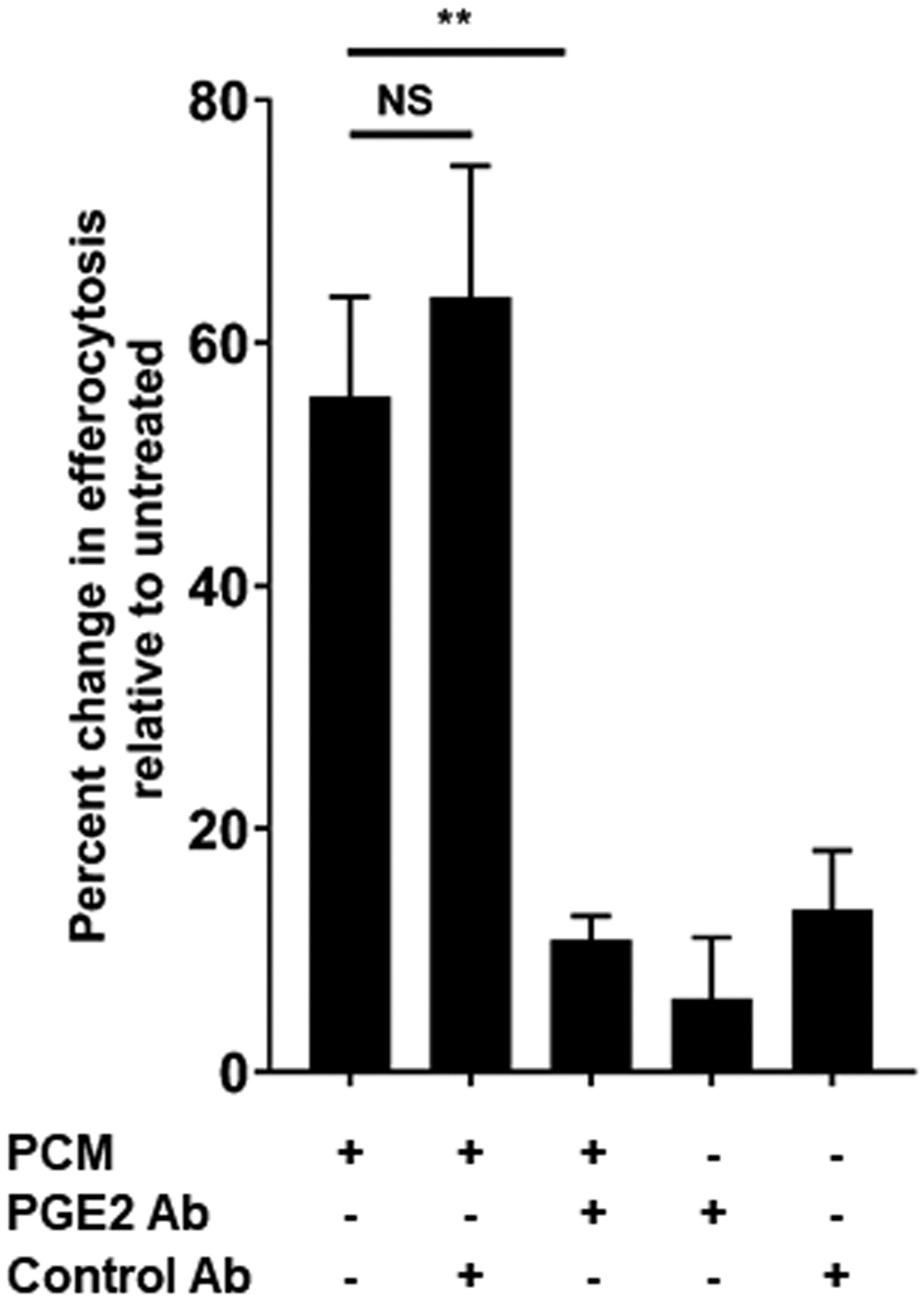

Efferocytosis is necessary for effective regression of atherosclerosis and stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques [9]. Del1 (Edil3) has been shown to play important roles in moderating inflammation in both endothelial cells and macrophages. In the latter, it acts to enhance efferocytosis [27, 28]. Transglutaminase2 (Tgm2) also regulates macrophage efferocytotic activity [29, 30]. Further, PGE2 has been shown to stimulate macrophage TGM2 expression [31] through EP4 [32], and reduced EP4 receptor expression results in suppressed Edil3 levels [33]. As we showed that PCM increased expression of Tgm2 and Edil3 through EP4, we assessed the effect of PCM exposure on the efferocytotic activity of macrophages. We observed significantly enhanced efferocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages exposed to PCM (Figures 5A and 5B, Supplemental Figure 4). This effect was eliminated by inclusion of a PGE2 antibody in PCM.

Figure 5. Platelet conditioned media (PCM) exposure stimulates efferocytosis.

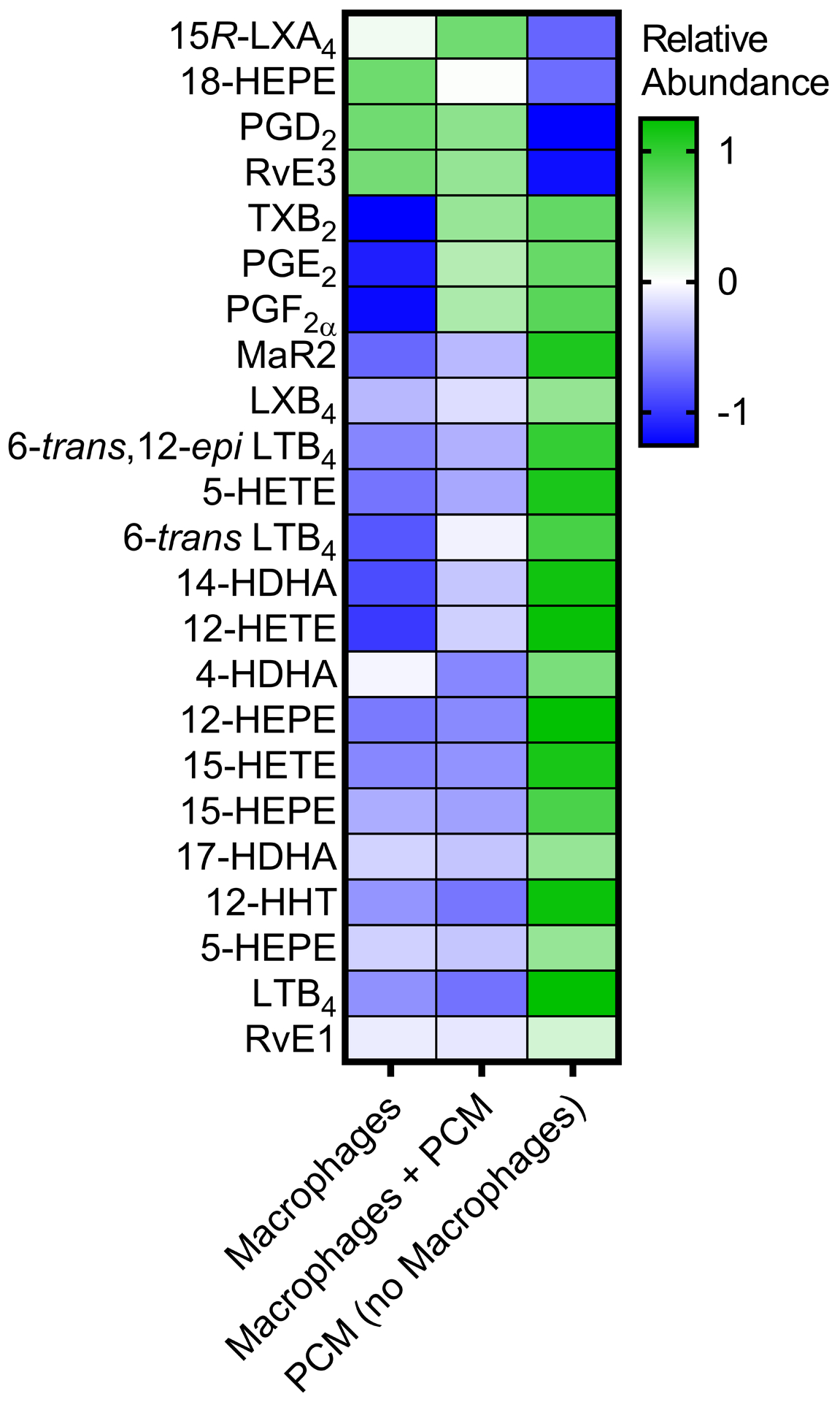

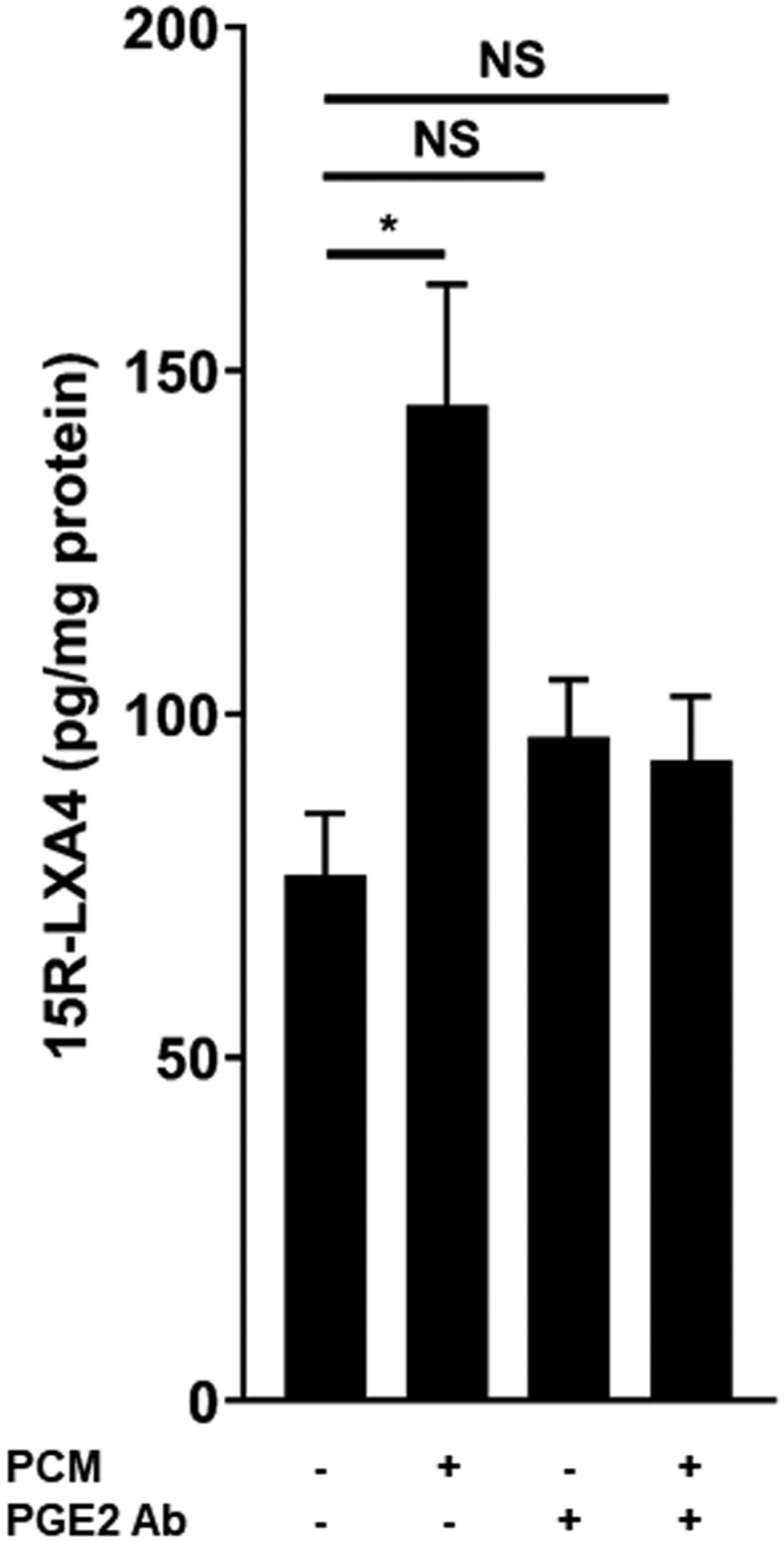

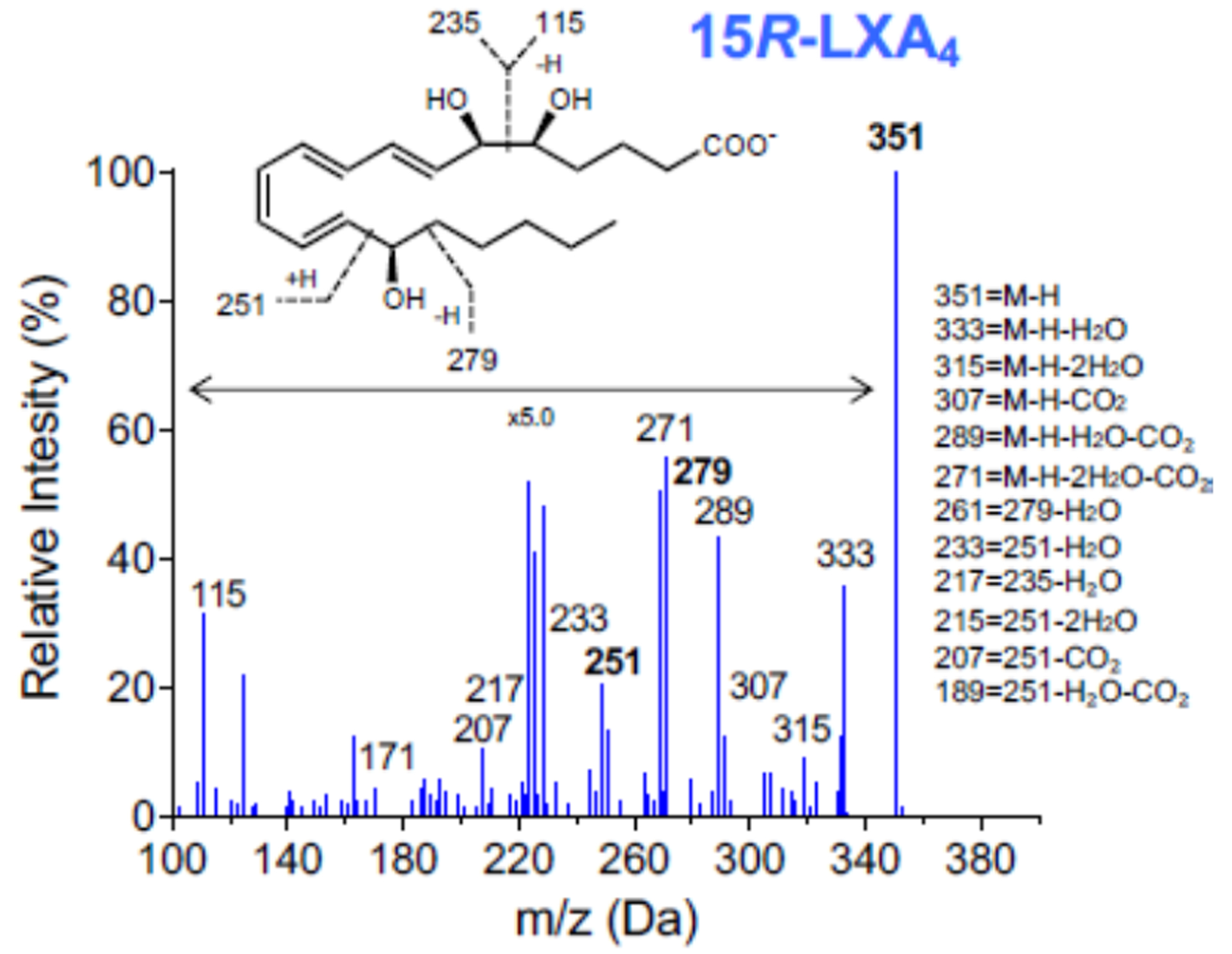

(A) RAW264.7 cells were exposed to PCM for 16 hours. Cells were washed and media containing apoptotic Jurkat cells was added to culture for 40 minutes. Flow cytometry was performed to quantify proportion of macrophages efferocytosing apoptotic cells (n = 6 independent experiments). (B) Fluorescent microscopy demonstrating efferocytosis of Jurkats by RAW264.7 cells under i. control conditions and after PCM exposure ii. with and iii. without PGE2 antibody. (C) Heatmap displaying the relative abundance of lipid mediators in media from RAW264.7 cells with or without exposure to PCM in phenol red-free media for 6 hours, and PCM alone. (D, E) RAW264.7 cells were exposed to PCM in phenol red-free media (± PGE2 antibody) for 6 hours. Media was then removed, centrifuged to remove cellular debris and 15R-LXA4 was measured by LC-MS/MS. Representative MS/MS spectra of 15R-LXA4 diagnostic ion assignments and structure are shown, with quantification shown in panel D (data from 3 independent experiments). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. 1-way ANOVA was used, followed by post-hoc two-tailed Student’s t-tests, to compare treatment conditions. NS = not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

To our knowledge, PGE2 itself has not previously been reported to induce efferocytosis. However, specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators are recognized as critical in the transition to inflammation-resolution facilitated by efferocytosis [34]. We thus questioned whether PGE2 present in the PCM could regulate production of pro-resolving lipid mediators in macrophages. We assessed a panel of lipid mediators in the media of macrophages stimulated or not with PCM and identified PGE2, PGF2α, TXB2 and several other pro-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators and their biosyntehetic pathway markers (Figure 5C). Of these, pro-resolving 15R-LXA4 was the only lipid mediator predominantly increased in macrophages exposed to PCM at a level above which it was present in the PCM alone. Further, we found that the increase in 15R-LXA4 in media from cells exposed to PCM was largely eliminated with the PGE2-blocking antibody, suggesting that PGE2 present in the PCM could stimulate macrophage production of 15R-LXA4 (Figures 5D and 5E). The production of this pro-resolving lipid mediator suggests another possible mechanism by which PCM may affect macrophage phenotype in vitro.

4. Discussion

In this report we demonstrate the capacity of products released from platelets to alter macrophage phenotype in vitro in a number of ways known to be important in atherosclerosis arrest and regression. These effects are mediated, at least in part, via PGE2 stimulation of the macrophage EP4 receptor. While PGE2 is traditionally characterized as a pro-inflammatory signaling molecule [35], our observations are in line with recent reports of platelets’ important role in restraining inflammation [2, 36, 37], as well as the increasing recognition of PGE2’s potential to induce anti-inflammatory phenotypes [20, 21, 38].

How platelets interact with macrophages in vivo, and thus the relevance of our findings, may not be immediately clear. This has been an area of focused investigation for our group. We have previously demonstrated co-localization of platelets and macrophages within both human [10] and murine [11] atherosclerotic plaques. These prior data demonstrate that platelets do interact with macrophages extensively and preferentially within plaques, even in the absence of plaque rupture [10, 11]. Additional experiments have shown that platelets do not require direct contact with macrophages to influence their function [11]. Thus, in vivo, the release of platelet PGE2 and other factors in the proximity of macrophages may be adequate to affect macrophage function and influence the course of the disease.

Some previous work supports our observations of the effects of PCM on macrophages. Earlier reports demonstrated that products released from platelets reduce macrophage TNFα production [2, 37] and increase arginase expression with associated reductions in nitric oxide synthesis [17]. In vivo, platelets have been shown to be critical in dampening overwhelming inflammation in sepsis – activity mediated through PGE2 and EP4 [2]. Further, PGE2 enhances M2 polarization of macrophages induced by IL4 [20] and independently stimulates Arg1, Tgm2 and Edil3 expression [31, 33], predominantly through EP4 [32, 39]. Additional in vitro experimentation has shown that PGE2 exposure increases cholesterol efflux [26]. In in vitro experiments, prostaglandins have been found to inhibit macrophage Lpl expression [40]. Macrophage-specific elimination of Lpl reduces atherosclerosis as well as foam cell formation and cholesterol ester content [41, 42], in the absence of differences in circulating lipoproteins. Accordingly, transgenic rabbits [43] and mice [44] expressing human lipoprotein lipase in their macrophages experience accelerated atherosclerosis. The reduced Lpl induced by PCM through EP4 may potentially translate to similar benefit in vivo.

In atherosclerosis regression, macrophage polarization to an M2 phenotype may occur absent STAT6 activation [5]. Notably, COX2 inhibition has been reported to impair macrophage polarization to an M2 phenotype [45], and stimulation of FPR2 (the receptor for 15R-LXA4) induces M2 polarization [46]. Our findings suggest that platelets may potentially contribute to this process, and further enhance any IL4-mediated M2 polarization via PGE2.

While a previous report suggested that PGE2 might impair efferocytosis [47], we found that exposure to PCM enhanced efferocytosis by macrophages. Notably, the concentrations of PGE2 used by Rossi et al. [47] were multiple orders of magnitude greater than those present in our assays. Others have demonstrated that in the setting of inflammation, the transition to resolution occurs in line with peak PGE2 concentrations in the picomolar range [48] – similar to those in PCM in our assays. Our experiments also demonstrated that PCM specifically increased 15R-LXA4 secretion by macrophages and that its production was blocked by the PGE2 antibody. Previous studies have shown that PGE2 stimulates the production of lipoxins in neutrophils to initiate the resolution phase of inflammation [38, 49]. Further, 15R-LXA4 increases efferocytosis in vivo [50]. Finally, 15R-LXA4 is known to suppress NFκB signaling [51] – a pathway implicated in platelet-stimulated Arg1 expression [17] – and also reduce peroxynitrite production in vitro [52]. Collectively, these results indicate that 15R-LXA4 may underlie some of the effects observed in our experiments.

We move beyond the independent reports of platelets and prostaglandins described above to demonstrate that exposure to PCM simultaneously induces a collection of phenotypic changes in macrophages that are consistent with a transcriptional and functional shift toward an anti-inflammatory, pro-resolving phenotype necessary for the process of atherosclerosis regression. Given our findings, in the context of recent reports from others [2, 17, 37], we suggest that a re-examination of this categorization and of the traditional paradigm of platelets as being solely pro-inflammatory is appropriate.

While the current work is focused on atherosclerosis, the pro-resolving nature of platelet-released PGE2 holds potential relevance in other processes – thrombus resolution, most obviously. Macrophages are key to the resolution of thrombosis. These cells constitute the majority of leukocytes in late thrombi and M2 polarization and adequate efferocytotic capacity of thrombus macrophages characterize successful thrombus resolution [53]. Recent data have demonstrated that PGE2 and pro-resolving lipid mediators increase over time in the setting of thrombosis and enhance phagocytic activity of monocytes [54]. Further, other work supports the importance of transcellular lipid mediator synthesis involving platelets and leukocytes in thrombus resolution in vivo [55]. Thus, it stands to reason that platelet PGE2 and downstream pro-resolving lipid mediator synthesis that it engenders may additionally facilitate thrombosis resolution.

Accordingly, our experimental observations demand further evaluation in in vivo atherothrombosis models. Extensive and elegant studies have been previously performed in attempts to clarify the influence of PGE2, and EP4 specifically, in the progression of atherosclerosis. Nonetheless, the results have been inconsistent. Some studies have found that macrophage EP4 activation inhibits inflammation [56, 57] with deletion exacerbating aortic aneurysm formation [57]. Others have found that knocking out EP4 on murine macrophages reduces [58] or has a null effect [59] on atherosclerosis. Importantly, a myeloid-specific Ptger4 knock-out model has not been employed in studies of atherosclerosis regression, nor in models of thrombosis resolution. Further, studies of atherosclerosis regression in which platelet counts or function are manipulated have also not been performed. Separate experiments, such as these, are required to address the potential translational implications of our work.

This study has a number of limitations. As discussed above, all of our work is in vitro and requires further validation in in vivo models. Further, many of our assays employed murine macrophages exposed to PCM containing the products released from human platelets – although lipid mediator structures are not species-dependent. However, we obtained consistent results in those assays that were also performed in human cells. Finally, all human platelet donors in this study were healthy. Whether platelets from individuals with atherosclerosis or other inflammatory conditions would produce similar effects remains untested.

Despite these limitations, our experiments demonstrate a powerful capacity of platelet-derived PGE2 to modulate macrophage phenotype as it relates to atherosclerosis regression through EP4. Certainly, in vivo extension of this work is warranted. If borne out, our findings suggest that more specific therapies targeting hemostatic properties of platelets, while not influencing pro-resolving, immune-related activities, may be beneficial for the treatment of atherothrombosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the generous contributions of Karishma Rahman, Kelly Ruggles, Nicole Allen, and Michael Cammer in the course of preparation of this manuscript.

Grant Support

S. P.Heffron was supported by HL135398, TR001446, AHA 14CRP18850107. A.Weinstock was supported by AHA 18POST34080390. B. E. Sansbury was supported by HL136044. C. C. Rolling was supported by DFG RO 6121/1-1. M. Spite was supported by GM095467 and HL10673. J. S. Berger was supported by HL139909 and HL144993. E. A. Fisher was supported by HL131478, HL131481 and HL084312.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to the publication.

References

- 1.Herter JM, Rossaint J, Zarbock A. Platelets in inflammation and immunity. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2014;12(11):1764–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiang B, Zhang G, Guo L, Li XA, Morris AJ, Daugherty A, et al. Platelets protect from septic shock by inhibiting macrophage-dependent inflammation via the cyclooxygenase 1 signalling pathway. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zamora C, Canto E, Nieto JC, Bardina J, Diaz-Torne C, Moya P, et al. Binding of Platelets to Lymphocytes: A Potential Anti-Inflammatory Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2017;198(8):3099–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ando Y, Oku T, Tsuji T. Platelets attenuate production of cytokines and nitric oxide by macrophages in response to bacterial endotoxin. Platelets. 2016;27(4):344–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(10):709–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pentikainen MO, Oksjoki R, Oorni K, Kovanen PT. Lipoprotein lipase in the arterial wall: linking LDL to the arterial extracellular matrix and much more. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2002;22(2):211–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubbo H, Trostchansky A, Botti H, Batthyany C. Interactions of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite with low-density lipoprotein. Biological chemistry. 2002;383(3–4):547–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhlencordt PJ, Chen J, Han F, Astern J, Huang PL. Genetic deficiency of inducible nitric oxide synthase reduces atherosclerosis and lowers plasma lipid peroxides in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Circulation. 2001;103(25):3099–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojima Y, Weissman IL, Leeper NJ. The Role of Efferocytosis in Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2017;135(5):476–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dann R, Hadi T, Montenont E, Boytard L, Alebrahim D, Feinstein J, et al. Platelet-Derived MRP-14 Induces Monocyte Activation in Patients With Symptomatic Peripheral Artery Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(1):53–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrett TJ, Schlegel M, Zhou F, Gorenchtein M, Bolstorff J, Moore KJ, et al. Platelet regulation of myeloid suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 accelerates atherosclerosis. Science translational medicine. 2019;11(517). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feig JE, Hewing B, Smith JD, Hazen SL, Fisher EA. High-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis regression: evidence from preclinical and clinical studies. Circ Res. 2014;114(1):205–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peled M, Fisher EA. Dynamic Aspects of Macrophage Polarization during Atherosclerosis Progression and Regression. Frontiers in immunology. 2014;5:579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahman K, Vengrenyuk Y, Ramsey SA, Vila NR, Girgis NM, Liu J, et al. Inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes and their conversion to M2 macrophages drive atherosclerosis regression. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(8):2904–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montenont E, Echagarruga C, Allen N, Araldi E, Suarez Y, Berger JS. Platelet WDR1 suppresses platelet activity and is associated with cardiovascular disease. Blood. 2016;128(16):2033–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalli J, Colas RA, Walker ME, Serhan CN. Lipid Mediator Metabolomics Via LC-MS/MS Profiling and Analysis. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ). 2018;1730:59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ando Y, Oku T, Tsuji T. Platelet Supernatant Suppresses LPS-Induced Nitric Oxide Production from Macrophages Accompanied by Inhibition of NF-kappaB Signaling and Increased Arginase-1 Expression. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41(1):14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Dyken SJ, Locksley RM. Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated alternatively activated macrophages: roles in homeostasis and disease. Annual review of immunology. 2013;31:317–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luan B, Yoon YS, Le Lay J, Kaestner KH, Hedrick S, Montminy M. CREB pathway links PGE2 signaling with macrophage polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(51):15642–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Na YR, Jung D, Yoon BR, Lee WW, Seok SH. Endogenous prostaglandin E2 potentiates anti-inflammatory phenotype of macrophage through the CREB-C/EBP-beta cascade. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45(9):2661–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazzoni M, Mauro G, Erreni M, Romeo P, Minna E, Vizioli MG, et al. Senescent thyrocytes and thyroid tumor cells induce M2-like macrophage polarization of human monocytes via a PGE2-dependent mechanism. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR. 2019;38(1):208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rath M, Muller I, Kropf P, Closs EI, Munder M. Metabolism via Arginase or Nitric Oxide Synthase: Two Competing Arginine Pathways in Macrophages. Frontiers in immunology. 2014;5:532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(1):315–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan ES, Zhang H, Fernandez P, Edelman SD, Pillinger MH, Ragolia L, et al. Effect of cyclooxygenase inhibition on cholesterol efflux proteins and atheromatous foam cell transformation in THP-1 human macrophages: a possible mechanism for increased cardiovascular risk. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(1):R4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bortnick AE, Rothblat GH, Stoudt G, Hoppe KL, Royer LJ, McNeish J, et al. The correlation of ATP-binding cassette 1 mRNA levels with cholesterol efflux from various cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(37):28634–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kourtzelis I, Li X, Mitroulis I, Grosser D, Kajikawa T, Wang B, et al. DEL-1 promotes macrophage efferocytosis and clearance of inflammation. Nature immunology. 2019;20(1):40–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T. DEL-1-Regulated Immune Plasticity and Inflammatory Disorders. Trends in molecular medicine. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rebe C, Raveneau M, Chevriaux A, Lakomy D, Sberna AL, Costa A, et al. Induction of transglutaminase 2 by a liver X receptor/retinoic acid receptor alpha pathway increases the clearance of apoptotic cells by human macrophages. Circ Res. 2009;105(4):393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falasca L, Iadevaia V, Ciccosanti F, Melino G, Serafino A, Piacentini M. Transglutaminase type II is a key element in the regulation of the anti-inflammatory response elicited by apoptotic cell engulfment. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):7330–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi M, Zacharia J, Laidlaw TM, Balestrieri B. PLA2G5 regulates transglutaminase activity of human IL-4-activated M2 macrophages through PGE2 generation. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100(1):131–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ylostalo JH, Bartosh TJ, Coble K, Prockop DJ. Human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells cultured as spheroids are self-activated to produce prostaglandin E2 that directs stimulated macrophages into an anti-inflammatory phenotype. Stem Cells. 2012;30(10):2283–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Thayele Purayil H, Black JB, Fetto F, Lynch LD, Masannat JN, et al. Prostaglandin E2 receptor 4 mediates renal cell carcinoma intravasation and metastasis. Cancer letters. 2017;391:50–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serhan CN, Levy BD. Resolvins in inflammation: emergence of the pro-resolving superfamily of mediators. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2018;128(7):2657–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science (New York, NY). 2001;294(5548):1871–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gudbrandsdottir S, Hasselbalch HC, Nielsen CH. Activated platelets enhance IL-10 secretion and reduce TNF-alpha secretion by monocytes. J Immunol. 2013;191(8):4059–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linke B, Schreiber Y, Picard-Willems B, Slattery P, Nusing RM, Harder S, et al. Activated Platelets Induce an Anti-Inflammatory Response of Monocytes/Macrophages through Cross-Regulation of PGE2 and Cytokines. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:1463216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loynes CA, Lee JA, Robertson AL, Steel MJ, Ellett F, Feng Y, et al. PGE2 production at sites of tissue injury promotes an anti-inflammatory neutrophil phenotype and determines the outcome of inflammation resolution in vivo. Science advances. 2018;4(9):eaar8320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez PC, Hernandez CP, Quiceno D, Dubinett SM, Zabaleta J, Ochoa JB, et al. Arginase I in myeloid suppressor cells is induced by COX-2 in lung carcinoma. J Exp Med. 2005;202(7):931–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Desanctis JB, Varesio L, Radzioch D. Prostaglandins inhibit lipoprotein lipase gene expression in macrophages. Immunology. 1994;81(4):605–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi M, Yagyu H, Tazoe F, Nagashima S, Ohshiro T, Okada K, et al. Macrophage lipoprotein lipase modulates the development of atherosclerosis but not adiposity. Journal of lipid research. 2013;54(4):1124–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Babaev VR, Fazio S, Gleaves LA, Carter KJ, Semenkovich CF, Linton MF. Macrophage lipoprotein lipase promotes foam cell formation and atherosclerosis in vivo. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1999;103(12):1697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ichikawa T, Liang J, Kitajima S, Koike T, Wang X, Sun H, et al. Macrophage-derived lipoprotein lipase increases aortic atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed Tg rabbits. Atherosclerosis. 2005;179(1):87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson K, Fry GL, Chappell DA, Sigmund CD, Medh JD. Macrophage-specific expression of human lipoprotein lipase accelerates atherosclerosis in transgenic apolipoprotein e knockout mice but not in C57BL/6 mice. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2001;21(11):1809–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Na YR, Yoon YN, Son DI, Seok SH. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition blocks M2 macrophage differentiation and suppresses metastasis in murine breast cancer model. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, Cai L, Wang H, Wu P, Gu W, Chen Y, et al. Pleiotropic regulation of macrophage polarization and tumorigenesis by formyl peptide receptor-2. Oncogene. 2011;30(36):3887–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rossi AG, McCutcheon JC, Roy N, Chilvers ER, Haslett C, Dransfield I. Regulation of macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by cAMP. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 1998;160(7):3562–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bannenberg GL, Chiang N, Ariel A, Arita M, Tjonahen E, Gotlinger KH, et al. Molecular circuits of resolution: formation and actions of resolvins and protectins. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2005;174(7):4345–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levy BD, Clish CB, Schmidt B, Gronert K, Serhan CN. Lipid mediator class switching during acute inflammation: signals in resolution. Nature immunology. 2001;2(7):612–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.El Kebir D, Jozsef L, Pan W, Wang L, Petasis NA, Serhan CN, et al. 15-epi-lipoxin A4 inhibits myeloperoxidase signaling and enhances resolution of acute lung injury. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180(4):311–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sham HP, Walker KH, Abdulnour RE, Krishnamoorthy N, Douda DN, Norris PC, et al. 15-epi-Lipoxin A4, Resolvin D2, and Resolvin D3 Induce NF-kappaB Regulators in Bacterial Pneumonia. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2018;200(8):2757–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jozsef L, Zouki C, Petasis NA, Serhan CN, Filep JG. Lipoxin A4 and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-lipoxin A4 inhibit peroxynitrite formation, NF-kappa B and AP-1 activation, and IL-8 gene expression in human leukocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(20):13266–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mukhopadhyay S, Johnson TA, Duru N, Buzza MS, Pawar NR, Sarkar R, et al. Fibrinolysis and Inflammation in Venous Thrombus Resolution. Frontiers in immunology. 2019;10:1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Norris PC, Libreros S, Chiang N, Serhan CN. A cluster of immunoresolvents links coagulation to innate host defense in human blood. Science signaling. 2017;10(490). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cherpokova D, Jouvene CC, Libreros S, DeRoo EP, Chu L, de la Rosa X, et al. Resolvin D4 attenuates the severity of pathological thrombosis in mice. Blood. 2019;134(17):1458–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takayama K, Garcia-Cardena G, Sukhova GK, Comander J, Gimbrone MA Jr., Libby P. Prostaglandin E2 suppresses chemokine production in human macrophages through the EP4 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(46):44147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang EH, Shvartz E, Shimizu K, Rocha VZ, Zheng C, Fukuda D, et al. Deletion of EP4 on bone marrow-derived cells enhances inflammation and angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(2):261–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Babaev VR, Chew JD, Ding L, Davis S, Breyer MD, Breyer RM, et al. Macrophage EP4 deficiency increases apoptosis and suppresses early atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2008;8(6):492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vallerie SN, Kramer F, Barnhart S, Kanter JE, Breyer RM, Andreasson KI, et al. Myeloid Cell Prostaglandin E2 Receptor EP4 Modulates Cytokine Production but Not Atherogenesis in a Mouse Model of Type 1 Diabetes. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0158316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.