Abstract

An exploited vulnerability in a single software component of healthcare technology can affect patient care. The risk of including third-party software components in healthcare technologies can be managed, in part, by leveraging a software bill of materials (SBOM). Analogous to an ingredients list on food packaging, an SBOM is a list of all included software components. SBOMs provide a transparency mechanism for securing software product supply chains by enabling faster identification and remediation of vulnerabilities, towards the goal of reducing the feasibility of attacks. SBOMs have the potential to benefit all supply chain stakeholders of medical technologies without significantly increasing software production costs. Increasing transparency unlocks and enables trustworthy, resilient, and safer healthcare technologies for all.

Subject terms: Technology, Industry

Cybersecurity is a national security issue. Healthcare public health was identified by the Presidential Policy Directive 21 (PPD-21) as one of sixteen critical infrastructure sectors1 and has a significantly large environment open to unauthorized attacks, also referred to as an “attack surface”. The 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act2 incentivized the connection of and conversion from isolated, disparate, often paper-based systems to electronic medical records to improve public health outcomes. Other connected healthcare technologies, such as bedside monitors for cardiac implants, have already improved patient outcomes3.

Connectivity of medical devices and systems increases patient benefits. Yet, connectivity also broadens the exposure of vulnerabilities across systems within the healthcare supply chain that, if exploited, can compromise healthcare delivery, thereby increasing patient risk (see Fig. 1)4. For example, the WannaCry ransomware attack impacted healthcare delivery in over a third of the United Kingdom’s National Health System (NHS) trusts5,6. In another example, the NotPetya cyberattack rendered unnamed products unavailable by disrupting manufacturing, research, and sales operations of Merck7. Other industries were also disrupted, including Maersk’s global shipping operations8,9.

Fig. 1. The impact of vulnerabilities.

A single vulnerability in a single third-party component has the potential to impact individual or classes of devices across innumerable healthcare organizations. Reprinted from NTIA Use Cases and State of Practice Working Group4.

This connectivity, with its benefits and risks, has been facilitated by software. In general, the reuse of software components, such as third-party software components, has been an effective way of reducing costs and the time and resources required during the software development cycle10. A 2017 audit and analysis of over 1100 commercial, cross-sector codebases found that 96% of software products11 included third-party software components such as commercial off-the-shelf components, modules, and libraries from both open-source and commercial third-party suppliers12. Reliance on third-party components to deliver needed functionality carries with it the potential for increased risk. For example, a single vulnerability in a third-party component upstream can potentially have profound downstream impacts on patient health, privacy, and safety.

Vulnerabilities in common third-party components can—and have—greatly impacted delivery of patient care. For instance, the WannaCry attack in May 2017 infected 200,000 computers in hospital systems across 150 countries13. These exploits leveraged a vulnerability in several versions of Microsoft Windows for which a patch had been issued in March 201714, 2 months prior to the attack. In the absence of a published software bill of materials (SBOM), builders such as medical device manufacturers and operators such as healthcare delivery organizations (HDOs) likely would have had to manually inventory systems to detect the vulnerable software versions. These resource-intensive processes can contribute to delays in patch validation, patch installation, and consequently, inoculation of systems. In another instance, vulnerabilities in JBoss—an open source technology library—led to critical outages at several HDOs despite the availability of updates for as long as 10 years in some cases15. Medical devices themselves can have thousands of vulnerabilities from third-party software components16–18, including approximately 1% of UK NHS devices impacted by WannaCry5. While SBOMs are not a panacea for cybersecurity, they can be effective (i.e., timely) for cybersecurity risk management. In each of these cases, had a preidentified list of third-party software components been accessible to customers such as HDOs, risk mitigation measures may have been pre-positioned and resources could have been efficiently targeted toward only affected, high-risk systems, thereby enabling more rapid incident response and potentially reducing disruption to healthcare delivery on a global scale.

A history of the software bill of materials

W. Edwards Deming, often credited with inspiring Japan’s post-war economic boom and the rise of manufacturing paradigms such as Toyota’s Supply Chain Management19,20, used the concept of a bill of materials (BOM) to track the parts used to create a product. The idea was that if defects are found in a specific part, manufacturers can use the BOM to easily locate affected products21. Tracking the provenance of parts across the supply chain also allows manufacturers to improve the quality of suppliers they select.

An SBOM is analogous to the list of ingredients on food packaging21. The ingredients list provides transparency about components (e.g., salt, nuts, and high-fructose corn syrup), allowing individuals with medical conditions, allergies, or preferences to make better buying decisions. Software engineers build products by assembling open-source and commercial software “components”, which are smaller pieces of software built by third parties. Similar to an ingredients list, an SBOM lists every component of software in the finished product. This ensures that anyone who chooses the product knows its relative hygiene, and anyone who uses the software knows what is inside. When a widespread vulnerability is discovered, SBOMs enable patients or organizations such as HDOs to identify impacted technology that might be in use.

The BOM concept has been applied to software supply chains for configuration management22, and working models pertaining to software updates, emergency management, and software licensing have existed since the late 1990s23–25. Recently, from a security perspective, SBOMs have been conceptually applied towards supply-chain assurance26,27, including as a potential solution for healthcare security risk28.

An example of effective application of the SBOM concept comes from the financial services industry. By 2015, a series of software supply-chain vulnerabilities had forced the industry to re-evaluate the third-party software in its infrastructure29. This sector quickly adopted SBOM concepts into their internal development and procurement processes30–33. Now, if a vendor can provide an SBOM, it serves as a litmus test for the maturity of the vendor’s organization. If vendors lack an SBOM, many financial services organizations anticipate that their products will likely cost more to evaluate, operate, and own over their lifecycles. As a result, the financial organizations might negotiate discounts to account for these increased costs32,33.

The energy sector likewise has adopted SBOM procedures to reduce vulnerabilities. In 2014, the Energy Sector Control Systems Working Group (ESCSWG) and its collaborators published standardized procurement language34. This “toolkit” aims to reduce cybersecurity risk by managing known vulnerabilities and delivering more secure systems. The software section of this document offers users specific language to include in contracts, which would require vendors to provide documentation of all components of the product, plans for their maintenance, and protocols for reducing various types of risk throughout the product’s lifecycle.

Although mounting security problems in healthcare and their root causes have clarified that SBOMs might solve several problems, implementation has been slow and there are few data available from the published peer-reviewed literature. Complicating this issue is a lack of out-of-the-box solutions and industry-wide standards, such that organizations have developed homegrown proprietary solutions to improve interoperability and security of their systems. As one example, the Mayo Clinic now requires prospective vendors of medical devices to submit a complete description of all components of their products, including software architecture, as part of its procurement process35. This is a rare instance of such information being publicly available for a healthcare entity, however.

The role of software bill of materials in proactive risk mitigation and resilience

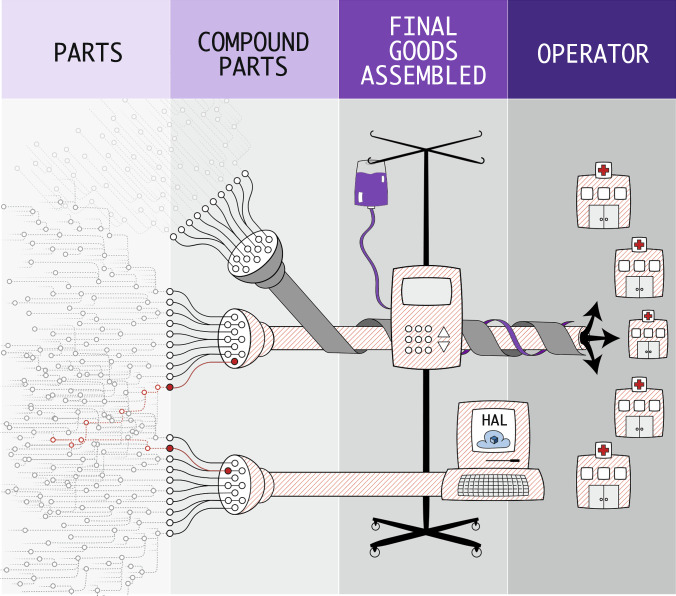

Software vulnerabilities and proof-of-concept exploits are often publicly known before they are used by adversaries. SBOMs are a tool that allows stakeholders to better manage cost and risk, both individually and across the healthcare ecosystem, by revealing the presence of vulnerable software components to various supply-chain stakeholders. These stakeholder roles include the builder (developer/manufacturer), buyer (customer), operator (hospital, doctor, and patient), and regulator of software products (see Fig. 2)4. Stakeholders can hold multiple roles; for example, a medical device manufacturer (MDM) can be both a builder and buyer of software.

Fig. 2. The software supply chain ecosystem.

The software supply chain ecosystem consists of manufacturers of parts, compound parts, and final goods assembled, and operators. A software bill of materials provides visibility into the contents of software throughout the supply chain. Reprinted from NTIA Use Cases and State of Practice Working Group4.

For the builder

Modern software is composed of both third-party components and custom code. Components and code are updated to improve functionality and to fix software bugs, some of which are security related. An SBOM can make the task of understanding what is included in the build, and therefore what needs maintenance, a more routine process for builders and other supply-chain stakeholders. Removing unneeded components in the final product is also a best practice that reduces the “attack surface” of the application36. As already mentioned, the financial services industry uses SBOMs to increase agility, efficiency, and effectiveness in maintaining its software.

For the buyer

For buyers, an SBOM helps evaluate risk at the time of purchase of a builder’s product (e.g., when an HDO buys a medical device from an MDM). An SBOM reveals individual software component versions that can then be matched to publicly known vulnerabilities, such as those listed in the National Vulnerability Database (nvd.nist.gov). Buyers can also compare different products, evaluating their relative complexity, composition, and quality.

Equipped with this information, buyers can better account for cost and risk in their buying decisions, selecting the best market option for themselves. While the builder may be willing to accept the risk these vulnerable components present to their organization, a buyer may deem the risks—or the costs to mitigate them—unacceptable. Some buyers that require SBOMs from builders might identify components for which they cannot mitigate risks at an acceptable cost. As a result, these buyers can prevent these components, often referred to as “non-permitted technologies”, from entering their environments32.

For operators

For organizations and individuals who operate and maintain software, tracking an SBOM throughout the product’s lifecycle allows a more proactive security posture by enabling operators to address newly discovered vulnerabilities before adversaries have a chance to compromise them. Traditionally, operators uncover vulnerabilities via point-in-time assessments, penetration tests, or coordinated disclosure notifications. While these methods are necessary to identify certain classes of exposure, they are costly, prone to errors, too slow to keep pace with adversaries, and disruptive to operations, including healthcare delivery. For rapid triage, an up-to-date set of SBOMs can be safely, easily, quickly, and inexpensively mined to understand if and how an organization is impacted by a newly discovered vulnerability (see Fig. 3)4. Further, with automation, SBOMs can support continuous vigilance and prompt notification of new, known vulnerabilities that may affect an organization.

Fig. 3. Multiple vulnerability pathways.

A single vulnerability has the potential to impact operations via multiple pathways. The same vulnerable third-party component can exist in medical devices and in enterprise systems. Both must be addressed to protect the entire healthcare technology ecosystem. Reprinted from NTIA Use Cases and State of Practice Working Group4.

For regulators

For regulators, SBOMs provide a map of overall public health risk when a vulnerability is reported. Analysis of SBOMs across products, companies, and hospitals can reveal and assist in managing systemic risk that would not be apparent within the scope of a single entity. This would also allow regulators to act quickly to reduce potential harm across the healthcare public health sector in the face of newly discovered vulnerabilities. Further, governmental and industry bodies can track vulnerabilities in products that are no longer supported—or whose manufacturers have gone out of business—to continue monitoring for potential security risks.

Implementing a software bill of materials

Multiple open-source and commercial tools can help builders compile, build, and maintain SBOMs. Many development environments can optionally produce SBOMs at the time the software is compiled37. Some code-repository tools monitor component dependencies38, provide alerts for security issues in dependencies39, or even automatically replace vulnerable dependencies with less vulnerable alternatives40. Additionally, some standalone tools offer similar features to those mentioned above41,42. Another tool that buyer/operators can leverage for communicating SBOM information is the Manufacturer Disclosure Statement for Medical Device Security, which was updated in October 2019 to include a new SBOM section that “supports controls in the Roadmap for Third Party Components in the Device Life Cycle (RDMP) section”43.

While progress has been made in the operationalization of SBOMs, challenges remain. The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) multi-stakeholder process on software component transparency is developing industry-led voluntary guidance on standardized formats, use cases, and SBOM tools44. Importantly, multinational companies45, Philips Medical46, and Siemens Healthineers47 have pioneered delivery of SBOMs to their customers, putting theory into practice.

Government and software bill of materials

“The health care system cannot deliver effective and safe care without deeper digital connectivity. If the health care system is connected, but insecure, this connectivity could betray patient safety, subjecting them to unnecessary risk and forcing them to pay unaffordable personal costs. Our nation must find a way to prevent our patients from being forced to choose between connectivity and security.”48

In June 2017, the US Health and Human Services (HHS) Cybersecurity Task Force made recommendations to help address cybersecurity within the healthcare public health sector, claiming that healthcare cybersecurity is in critical condition, citing a number of root causes related to software supply chain vulnerabilities48. The report outlines how SBOMs could positively impact healthcare and recommended that manufacturers and developers create SBOMs. In November 2017, the Chair and Ranking Member of the US House Committee on Energy and Commerce called on HHS to “convene a sector-wide effort to develop a plan of action for creating, deploying, and leveraging BOMs for health care technologies”49. Additional support for the adoption of SBOMs in healthcare came in a May 2018 letter from the Executive Vice President of the American Medical Association to the Energy and Commerce committee50.

In April 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) released its Medical Device Safety Action Plan51. The action plan stated that the FDA was revising their 2014 premarket cybersecurity guidance52 and exploring additional authorities that would require an SBOM to be submitted to the FDA prior to a device reaching the market. In October 2018, FDA CDRH released its draft premarket cybersecurity guidance53, which stated that leveraging an SBOM may support compliance with federal purchasing controls (21 CFR 820.50)54. Purchasing controls could be a significant legal lever for MDMs, as buyers of software, to perform due diligence on software component builders before incorporation into devices. The guidance also states that, as part of risk management, MDMs should provide a bill of materials cross referenced with the National Vulnerability Database or similar known vulnerabilities database. Due to legal compliance, tying quality system regulations for risk management to SBOM could help facilitate the management of third-party component security risk after the device is marketed, including incentivizing changes to devices for cybersecurity. Further, since 2005, FDA’s policy55 has stated that changes to devices for cybersecurity typically do not need to be submitted to the agency for clearance or approval (sometimes referred to as recertification)56–58, and that not all software changes are recalls59.

While HHS and FDA represent significant regulatory incentives for builders and buyers, other governmental efforts have been impactful. In September 2018, the NTIA launched a multi-stakeholder process for software transparency. The NTIA initiative included an SBOM proof-of-concept study for healthcare public health, which was led by MDMs and healthcare delivery organizations60. The Joint Commission and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services are designated to improve and impress the safety of health information technology for compliance, management, and organizational management. The Department of Defense Risk Management Framework also aligns the organizational and traditional baseline control-selection approaches for a more secure system that holds supply chain vendors and engineers liable for their processes, with a distinct focus on the systems security recommendations from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)61.

Internationally, the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) has published a draft set of principles and practices for medical device security that includes SBOM62, as do the Health Canada requirements for medical device security63 and EU guidance64.

The path forward

SBOMs have a role to play in further advancing the public’s trust in connected technologies. An SBOM reveals distinctions among products, allows buyers to better account for total cost and risk, and gives buyers better tools to identify, respond to, and recover from vulnerabilities and their effects.

Widespread adoption of SBOM could allow for earlier identification of software vulnerabilities, shorter time to remediation, and heightened awareness of outbreaks and their effects31. A growing number of regulators, builders, and operators are recognizing the value of SBOMs. All signs point to SBOM being more widely adopted in the coming years, particularly in industries where technology is life-critical and transparency is paramount. The rate of adoption will increase if the efforts outlined in this paper continue to move forward. Increasing transparency unlocks and enables trustworthy, resilient, and safer healthcare technologies for all.

Acknowledgements

For suggesting compelling examples and polishing the stories in the manuscript, we gratefully acknowledge Adam Conner-Simons, Suzanne Schwartz, Linda Ricci, and Aftin Ross. For supporting with formatting and copy-editing of the manuscript, we gratefully acknowledge Patricia French and Lisa Maturo.

Author contributions

S.C. drafted and substantially revised the manuscript. A.C. drafted and substantially revised the manuscript. B.W. drafted and substantially revised the manuscript. G.F. drafted and substantially revised the manuscript. J.M. drafted and substantially revised the manuscript. A.H. drafted and substantially revised the manuscript and created the figures. J.C. drafted and substantially revised the manuscript.

Competing interests

Seth Carmody is the Vice President of Regulatory Strategy at MedCrypt, Founder and CEO of DRX Labs, and former Cybersecurity Program Manager at the US Food and Drug Administration. Andrea Coravos is the CEO of Elektra Labs, Inc. Audra Hatch is the Product Security Specialist at Thermo Fisher Scientific. Josh Corman is the Chief Security Officer and Senior Vice President at PTC, Inc. Ginny Fahs, Audra Hatch, Janine Medina, Beau Woods, and Josh Corman are all unpaid members of I Am The Cavalry.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cyber Security & Infrastructure Security Agency. Critical infrastructure sectors. https://www.dhs.gov/cisa/critical-infrastructure-sectors (2015).

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HITECH Act Enforcement Interim Final Rule.https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/hitech-act-enforcement-interim-final-rule/index.html (2009).

- 3.Slotwiner D, et al. HRS Expert Consensus Statement on remote interrogation and monitoring for cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:e69–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) use cases and state of practice working group. Roles and Benefits for SBOM Across the Supply Chain.https://www.ntia.gov/files/ntia/publications/ntia_sbom_use_cases_roles_benefits-nov2019.pdf (2019).

- 5.National Audit Office. Investigation: WannaCry Cyber Attack and the NHS.https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Investigation-WannaCry-cyber-attack-and-the-NHS.pdf (2017).

- 6.Woods, B. & Bochman, A. Supply Chain in the Software Era. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/supply-chain-in-the-software-era/ (2018).

- 7.Merck & Co, Inc. Merck announces second-quarter 2017 financial results. https://www.merck.com/news/merck-announces-second-quarter-2017-financial-results/ (2017).

- 8.Greenber, A. The untold story of NotPetya, the most devastating cyberattack in history. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/notpetya-cyberattack-ukraine-russia-code-crashed-the-world/ (2018).

- 9.A. P. Møller–Mærsk A/S. 2017 Annual Report. http://investor.maersk.com/static-files/250c3398-7850-4c00-8afe-4dbd874e2a85 (2018).

- 10.Arhippainen, L., for the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland. Use and Integration of Third-Party Components in Software Development. VTT Publications 489. http://www.vtt.fi/inf/pdf/publications/2003/P489.pdf (2003).

- 11.Synopsis. 2018 Open Source Security and Risk Analysis (OSSRA) Report. https://www.blackducksoftware.com/open-source-security-risk-analysis-2018 (2018).

- 12.Software Assurance Forum for Excellence in Code (SAFECode). Managing Security Risks Inherent in the Use of Third-Party Components. https://safecode.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/SAFECode_TPC_Whitepaper.pdf (2017).

- 13.Reuters. Cyber attack hits 200,000 in at least 150 countries: Europol. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cyber-attack-europol/cyber-attack-hits-200000-in-at-least-150-countries-europol-idUSKCN18A0FX (2017).

- 14.Microsoft. Microsoft Security Bulletin MS17-010–Critical. https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/security-updates/securitybulletins/2017/ms17-010 (2017).

- 15.Abdollah, T. Hackers broke into hospitals despite software flaw warnings. https://apnews.com/86401c5c2f7e43b79d7decb04a0022b4 (2016).

- 16.Cyber Security & Infrastructure Security Agency. ICS Advisory (ICSMA-18-088-01): Philips iSite/IntelliSpace PACS Vulnerabilities (Update A). https://www.us-cert.gov/ics/advisories/ICSMA-18-088-01 (2018).

- 17.Cyber Security & Infrastructure Security Agency. ICS Advisory (ICSMA-16-089-01): CareFusion Pyxis SupplyStation System Vulnerabilities. https://www.us-cert.gov/ics/advisories/ICSMA-16-089-01 (2017).

- 18.Rios, B. & Butts, J. Security Evaluation of the Implantable Cardiac Device Ecosystem Architecture and Implementation Interdependencies. https://a51.nl/sites/default/files/pdf/Pacemaker Ecosystem Evaluation.pdf (2017).

- 19.Leitner PM. Japan’s post-war economic success: deming, quality, and contextual realities. J. Manag. Hist. 1999;5:489–505. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Womack JP, Jones DT. How to root out waste and pursue perfection. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996;74:140–172. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stern G. Preparing for the next cyber storm: are you ready? Biomed. Instrum. Technol. 2019;53:412–419. doi: 10.2345/0899-8205-53.6.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leblang, D. B. & Levine, P. H. Software Configuration Management (eds Estublier, J.) (Springer-Verlag, 1993).

- 23.Schmidt, R. & Duffy, T. Non-interfering software distribution. In Proceedings of the DASIA 97 Meeting on Data Systems in Aerospace, Seville, Spain, 26-29 May, 1997. (ed. Guyenne, T.-D.) ESA SP-409, 351–358 (European Space Agency, Paris, 1997).

- 24.Fangman, P. M., Gerhardstein, L. H. & Homer, B. J. Federal Emergency Management Information System (FEMIS): Bill of Materials (BOM) for FEMIS, version 1.4.5. No. PNL-10689-Ver. 1.4.5. (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, WA, 1998).

- 25.Nordquist P, Petersen A, Todorova A. License tracing in free, open, and proprietary software. J. Comput. Sci. Coll. 2003;19:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin, R. A. Visibility & control: addressing supply chain challenges to trustworthy software-enabled things. 2020 IEEE Systems Security Symposium (SSS), Crystal City, VA, USA, 1–4. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9174365 (2020).

- 27.Martin, R. A. Assurance for cyberphysical systems: addressing supply chain challenges to trustworthy software-enabled things. 2020 IEEE Systems Security Symposium (SSS), Crystal City, VA, USA, 1–5 https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9174201 (2020).

- 28.Sparrell, D. Cyber-safety in healthcare IOT. 2019 ITU Kaleidoscope: ICT for Health: Networks, Standards and Innovation (ITU K), Atlanta, GA, USA, 10.23919/ITUK48006.2019.8996148 (2019).

- 29.Geer D, Corman J. Almost too big to fail. Login. 2014;39:66–68. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center (FS-ISAC) Third-Party Software Security Working Group. Appropriate Software Security Control Types for Third Party Service and Product Providers. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1vm3JwEtAJqjpRPXoSgY99ijWIBcSSaSz/view (undated).

- 31.FS-ISAC Third Party Software Security Working Group. Appropriate Software Security Control Types for Third-Party Service and Product Providers. Version 2.3. https://www.fsisac.com/hubfs/Resources/FSISAC-ThirdPartySecurityControlTypes-Whitepaper_2015.pdf (2015).

- 32.NTIA. Transcript, Multistakeholder Meeting on Software Component Transparency, Part 1. https://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/july_19_ntia_-_part_1_transcript.pdf (2018).

- 33.NTIA. Multistakeholder Meeting on Software Component Transparency, Webcast Archive. Part 1. https://www.ntia.doc.gov/other-publication/2018/webcast-archive-071918-meeting-promoting-software-component-transparency (2018).

- 34.Energy Sector Control Systems Working Group (ESCSWG). Cybersecurity Procurement Language for Energy Delivery Systems. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/04/f15/CybersecProcurementLanguage-EnergyDeliverySystems_040714_fin.pdf (2014).

- 35.Mayo Clinic. Medical and research device risk assessment vendor packet instructions. https://www.mayoclinic.org/documents/medical-device-vendor-instructions/doc-20389647 (2020).

- 36.Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP). Security by design principles. https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Security_by_Design_Principles (2016).

- 37.CycloneDX.org. CycloneDX implementations. https://cyclonedx.org/#implementations (2020).

- 38.GitHub.com. Exploring the dependencies of a repository. https://help.github.com/en/github/visualizing-repository-data-with-graphs/listing-the-packages-that-a-repository-depends-on (2019).

- 39.GitHub.com. About security alerts for vulnerable dependencies. https://help.github.com/en/github/managing-security-vulnerabilities/about-security-alerts-for-vulnerable-dependencies (2019).

- 40.GitHub.com. Configuring Dependabot security updates. https://help.github.com/en/github/managing-security-vulnerabilities/configuring-automated-security-updates (2019).

- 41.OWASP. OWASP Dependency-Check. https://owasp.org/www-project-dependency-check/ (2019).

- 42.Promenade Software. Automated vulnerability alerts for embedded Linux. https://promenadesoftware.com/blog/automated-vulnerability-alerts-embedded-linux (2016).

- 43.National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA). American National Standard: Manufacturer Disclosure Statement for Medical Device Security. ANSI/NEMA HN 1-2019. https://www.nema.org/Standards/view/Manufacturer-Disclosure-Statement-for-Medical-Device-Security (2019).

- 44.NTIA. NTIA software component transparency. https://www.ntia.doc.gov/SoftwareTransparency (2020).

- 45.Stockhausen, H. B. & Rose, M. W. Continuous security patch delivery and risk management for medical devices. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Software Architecture Companion (ICSA-C), Salvador, Brazil. 10.1109/ICSA-C50368.2020.00043 (2020).

- 46.Koninklijke Philips N. V. Position Paper: Committed to Proactively Addressing Our Customers’ Security and Privacy Concerns. https://images.philips.com/is/content/PhilipsConsumer/Campaigns/HC20140401_DG/Documents/Philips_Cybersecurity_Position_Paper_20180306.pdf (2018).

- 47.Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc. Cybersecurity: Protecting healthcare institutions against cyberthreats. https://www.siemens-healthineers.com/en-us/support-documentation/cybersecurity (2020).

- 48.Health Care Industry Cybersecurity Task Force. Report on Improving Cybersecurity in the Health Care Industry. https://www.phe.gov/preparedness/planning/cybertf/documents/report2017.pdf (2017).

- 49.Walden, G. & Pallone, F. Jr. Letter from the House Committee on Energy and Commerce to Acting Secretary, US Department of Health and Human Services. https://republicans-energycommerce.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/20171116HHS.pdf (2017).

- 50.Madara, J. L. Letter from the American Medical Association to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce on cybersecurity and the use of legacy technologies in health care. https://searchlf.ama-assn.org/undefined/documentDownload?uri=/unstructured/binary/letter/LETTERS/2018-5-24-Letter-to-Walden-Pallone-re-Draft-Cybersecurity-Response-to-EC-RFI.pdf (2018).

- 51.US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Medical Device Safety Action Plan: Protecting Patients, Promoting Public Health. https://www.fda.gov/media/112497/download (2019).

- 52.FDA. Content of Premarket Submissions for Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. https://www.fda.gov/media/86174/download (2014).

- 53.FDA. Content of Premarket Submissions for Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. https://www.fda.gov/media/119933/download (2018).

- 54.US Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, CFR 820.50. Purchasing controls. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfCFR/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=820.50 (2019).

- 55.FDA. Cybersecurity for Networked Medical Devices Containing Off the-Shelf (OTS) Software. https://www.fda.gov/media/72154/download (2005).

- 56.FDA. Postmarket Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. https://www.fda.gov/media/95862/download (2016).

- 57.FDA. FDA Fact Sheet: The FDA’s Role in Medical Device Cybersecurity. https://www.fda.gov/media/123052/download (2017).

- 58.FDA. Deciding When to Submit a 510 (k) for a Software Change to an Existing Device: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. https://www.fda.gov/media/99785/download (2017).

- 59.FDA. Distinguishing Medical Device Recalls from Medical Device Enhancements: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. https://www.fda.gov/media/89909/download (2014).

- 60.NTIA. Software Component Transparency: Healthcare Proof of Concept Report. https://www.ntia.gov/files/ntia/publications/ntia_sbom_healthcare_poc_report_2019_1001.pdf (2019).

- 61.Ross, R., McEvilley, M., & Oren, J. C. Systems Security Engineering: Considerations for a Multidisciplinary Approach in the Engineering of Trustworthy Secure Systems, vol. 1. NIST Special Publication 800-160, 10.6028/NIST.SP.800-160v1 (2018).

- 62.International Medical Device Regulators Forum, Medical Device Cybersecurity Working Group. Principles and Practices for Medical Device Cybersecurity. http://imdrf.org/docs/imdrf/final/technical/imdrf-tech-200318-pp-mdc-n60.pdf (2020).

- 63.Health Canada. Guidance Document: Pre‐market Requirements for Medical Device Cybersecurity. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/drugs-health-products/medical-devices/application-information/guidance-documents/cybersecurity-guidance.pdf (2019).

- 64.Medical Device Coordination Group. MDCG 2019-16 Guidance on Cyber Security for Medical Devices. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/md_sector/docs/md_cybersecurity_en.pdf (2019).