Abstract

Particulate matter (PM2.5) has a severe impact on human health. The concentration of PM2.5, related to air-quality changes, may be associated with perceptible effects on people's health. In this study, computer intelligence was used to assess the negative effects of PM2.5. The input data, used for the evaluation, were grid definitions (shape-file), PM2.5, air-quality data, incidence/prevalence rates, a population dataset, and the (Krewski) health-impact function. This paper presents a local (Pakistan) health-impact assessment of PM2.5 in order to estimate the long-term effects on mortality. A rollback-to-a-standard scenario was based on the PM2.5 concentration of 15 μg m−3. Health benefits for a population of about 73 million people were calculated. The results showed that the estimated avoidable mortality, linked to ischemic heart disease and lung cancer, was 2,773 for every 100,000 people, which accounts for 2,024,290 preventable deaths of the total population. The total cost, related to the above mortality, was estimated to be US $ 1,000 million. Therefore, a policy for a PM2.5-standard up to 15 μg m−3 is suggested.

Keywords: BenMAP-CE, Ischemic heart disease, PM2.5

BenMAP-CE, Ischemic Heart Disease, PM2.5.

1. Introduction

Particulate matter (PM) has a negative impact on the biosphere, depending on its size, chemical composition, and source (Kelly and Fussell, 2012). More specifically, PM2.5, which has an aerodynamic diameter of ≤2.5 μm, is the main focus of attention among environmental specialists. PM2.5 contains carbon compounds, sulfates, nitrates, ammonium, heavy metals, H+, and condensed metal vapors (McMurry et al., 2004). Sulfur and nitrogen oxides (SOx, NOx), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and NH3 are the main precursors of secondary PM (Hidy and Pennell, 2010; McMurry et al., 2004). Anthropogenic and naturally occurring PM2.5 contains both organic and inorganic components. Sulfates and nitrates constitute the inorganic PM, while VOCs coming from vehicle exhausts, industrial emissions, and biogenic sources account for the organic carbon fraction of PM (Jacob and Winner, 2009; McMurry et al., 2004; Stone et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2008). The emission of ammonia (NH3) in open air intensifies the particulate content in the ambient environment (Aneja et al., 2009).

Solar radiation and other environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity, contribute to the increase in the number of pollutants in fresh air (Aneja et al., 2001; Hidy and Pennell, 2010; Jacob and Winner, 2009). During the cold seasons of the year, ammonium nitrate PM easily precipitates in an environment with high ammonia and water content (Pitchford et al., 2009), but this is rarely observed in warm days (Aw and Kleeman, 2003; Jacob and Winner, 2009). On the contrary, PM of sulfate increases with increasing temperature (Kleeman, 2008; Liu et al., 2009). The PM2.5 content in the environment is increased owing to sources, such as car exhausts (Liu et al., 2009; Incecik, 1996).

Increasing urbanization, high living-standards, and industrial plants built without planning, increase air pollution. For instance, in Pakistan, emissions from vehicles, industry, and power plants are the main sources of PM2.5 (Pakistan Economic Survey, 2012). The development and operation of two-stroke and diesel engines has also increased environmental pollution (Asian Development Bank, 2006a; World Bank, 2006). Diesel and furnace oil contain 0.5–1% and 1–3.5% sulphur, respectively. The endless use of fossil fuels increases the concentration of sulphur dioxide - a precursor of PM2.5 - in the air, in the local environment (Asian Development Bank, 2006a). During the winter season, in most urban areas, 90% of sooty aerosols are released in the atmosphere, resulting in 15% more PM2.5 concentration in the air (Husain et al., 2007; Viidanoja et al., 2002). It has also been reported that winter fog increases the level of environmental pollution in some regions of Pakistan (Biswas et al., 2008; Hameed et al., 2000). Coal-fired power plants are also a major source of PM (J.W October 18, 2015).

The serious consequences for human health on account of PM are well known (Eionet core data flows 2019), and the various effects of PM2.5 have been studied thoroughly by environmental experts and epidemiologists (Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, 2015b). An epidemiological study, conducted by several researchers in various regions and environments for different age groups, has demonstrated that there is a close association between PM2.5 and Minor Restricted Activity Days (MRADs), Respiratory Related Restricted Activity Days (RRADs), hospital admissions, outdoor patient appointments for respiratory and cardiac complaints, and for chronic bronchitis and asthma (Abbey et al., 1995; ARDEN POPE III et al., 1991; Dockery et al., 1996; Glad et al., 2012; Katsouyanni et al., 2009; Koenig and Mar 2009; Mar et al., 2010; Mar et al., 2004; Mortimer et al., 2002; Norris et al., 1999; Ostro et al., 200; Ostro, 1987; Ostro and Rothschild, 1989; Peel et al., 2005; Peters et al., 2001; Sarnat et al., 2013; Schildcrout et al., 2006; Schwartz and Neas, 2000; Sheppard et al., 1999; Slaughter et al., 2005; Wilson et al., 2005; Zanobetti et al., 2009). It is worthy of note that recently, during the pandemic period of COVID-19, the researchers had the unique opportunity to present the strong correlation between the concentration of PM (which was dramatically reduced during the period of the enforcement of tough restriction measures) and the above health problems (Setti et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020).

Experts have estimated the annual cost of environmental degradation in Pakistan to be over US$ 370 million (Pakistan Economic Survey, 2013–14). The World Bank (WB) has reported US$ 482 million and US$ 2,625 million, or 6% of GDP, as the annual costs of air quality and environmental degradation in Pakistan, respectively. Most importantly, the WB has estimated a total of 28,000 deaths and 40 million lung-related diseases caused by air pollution (World Bank, 2006). Other environmentalists have estimated the negative effect on public health due to PM at around US$ 467 million, claiming that PM has caused about 22,000 premature deaths to adults and 700 deaths among teenagers (Dise et al., 2011; McMurry et al., 2004; Pope III et al., 2002; Pope III et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2013).

Accordingly, air pollution, attributed to PM2.5, has caused alarm among environmentalists. The increasing concentration of PM2.5 in the environment is a common problem of serious concern for all people, and hence, it must be given top priority (Anjum et al., 2020). In many places around the world, such as in South Asia, including Pakistan, PM2.5 concentration in the environment has exceeded the standardized limit of the World Health Organization (WHO) Air Quality Index (AQI). With a land area of 79,695 km2 and a total population of 199.7 million, Pakistan lies on an important geographical location in South Asia (Pakistan Economic Survey, 2017). The National Environmental Quality Standards Authority (NEQS) announced the daily and annual 24-hour mean values of PM2.5 concentrations as 40 and 25 μg m−3, respectively, which were revised as 35 and 15 μg m−3, respectively (Pak-EPA, 2010).

In the urban areas of Pakistan, there are large sources that provide precursors for PM of different sizes (PM10, PM2.5), which suppress the potential to meet the PM standard in these areas. In addition to all these obstacles, local health-impact assessments face serious methodological challenges, such as expensive IT resources and lack of technical expertise (Hubbell et al., 2009). In this paper, computational intelligence and portable and affordable technologies, such as the “Temtop 1000” sensor, have been employed in order to correlate the PM concentration with adverse effects on human health, such as mortality owing to ischemic heart disease (IHD) and lung cancer, or due to a number of other causes (all-cause mortality).

2. Methodology

2.1. Temtop Airing-1000

The PM2.5 concentration levels were measured by using a lightweight, portable, and cost-effective “Temtop Airing 1000” particle detector, with a measurement range of 0–999 μg m−3, and a resolution of 0.1 μg m−3. The instrument detects PM2.5 and displays its time-series concentration. The concentration of PM2.5 was determined at 312 different places of known coordinates.

2.2. BenMAP-CE

The Environmental Mapping and Analysis Program (BenMAP-CE) is an open computational resource, which calculates the air-quality changes for a specific type of pollutant. In the present study, PM2.5 was the pollutant. The aim was to correlate its known adverse effects on health with ambient variables. The negative effects on health are then monetized using PM2.5 concentration-response functions.

BenMAP assesses the economic impact of these effects on health, using evidence-based assessment methods that are schemes for effective economic evaluation. A Community Addition Version 1.4 of BenMAP was used and complementary data manipulation and applied mapping techniques were performed, using Global Burden of Disease (GBD) and ArcMap software (ArcGIS Desktop, 2015).

The whole process is described in the following sub-sections.

2.3. Grid definition

It is the first step that determines the geographical clusters (i.e. grid cells). Each cluster was assigned to numerical values related to air quality, population, baseline incidence rates, and health-impact functions for impact assessment. The shape-file (Pakistan) was projected over the World Geodetic System (WGS1984). The grid covered all the 312 points, where PM2.5 was monitored.

2.4. Pollutant metrics

It is the second step, which identifies the pollutants for the air-quality metrics. The present analysis is based only on PM2.5 pollutants. The air-quality metric represents the average value of the pollutants registered over the period of one day. The pollutant metrics recorded the daily average values of air quality at each measuring station.

In this study, the D24HourMean metric was used. The D24HourMean metric for a given monitor is created by selecting the average value for a 24-hour average per day. The analysis was focused on air-quality monitoring data for the year 2017. The monitoring data was not pre-installed in BenMAP-CE; it was aggregated, processed, and formatted according to the BenMAP-CE import specifications (Raffi et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2016).

2.5. Air-quality data

The air quality is an estimate for the exposure of the population to air pollution. More specifically, the air-quality surfaces are the air-quality grids that have been covered with the air pollution recorded at the monitored sites. Regular grids and air-quality surfaces were used to estimate the average exposure of people living in a "grid" of air pollution. As a measure of the individual exposure to air pollution, the average exposure of the population living in a grid was calculated. Next, the modeled surfaces were interpolated with the Voronoi Neighborhood Averaging (VNA) function to create a continuous surface over the shape-file.

2.6. Changes in air quality

The difference between the baseline air pollution (monitored pollution) and the controlled pollution level (15 μg m−3) created air-quality delta for PM2.5 metrics.

2.7. Air-pollution rollback scenarios

The rollback scenarios reduced the monitored data to a different level. The monitored data were rollbacked to a standard value of 15 μg m−3. The unattainable stations were reset to the hypothetical standard of 15 μg m−3 (Zhang et al., 2016).

All the highest values were trimmed by specifying the ordinality parameters (Kalimuthu et al., 2008). For example, the first ordinality was the highest daily average over the year and the second ordinality was the second highest average value. The first ordinality did not trim high values, but the second ordinality trimmed the individual highest value (Carvour et al., 2018).

The rollback strategies distinguish anthropogenic from non-anthropogenic concentration levels of PM2.5. The non-anthropogenic background concentration of PM2.5 was set at 5.8 μg m−3 (McCubbin and Force, 2011). The analysis reduced PM2.5 concentrations by 10 % until the standard value of 15 μg m−3 was reached for the areas that had not reached the standard.

2.8. Health-impact functions

The beta (β) parameter is an effect estimate, which was evaluated for IHD and lung cancer as 0.0215 ± 0.0020 and 0.0131 ± 0.0037, respectively. Health effects are categorized into two groups: one is mortality and the second is disease-specific endpoints, such as asthma, emergency room visits, and hospital stays (Mortimer et al., 2002; Norris et al., 1999). Krewski et al. (2009), established three health-impact functions for all-cause mortality, IHD, and lung cancer (Krewski et al., 2009).

2.9. Estimation of health impacts

Using the baseline incidence (Y0) of population (Pop) of 20.7 million, the health impact (ΔΥ) for the air-quality changes (ΔPM) (Haq et al., 2008) were estimated by Eq. (1):

| (1) |

2.10. Economic valuation

The reduction in air pollution can have an impact on health effects. Health effects have been assessed using valuation functions, such as the value of a statistical lifetime (VSL), based on mortality endpoints and the Weibull-distributed value of a VSL, derived from a set of 26 valuation functions (Mondal et al., 2011). Based on two factors, i.e. society's willingness to pay (WTP) for risk reduction, and the actual cost of illness (COI) for an effect, it was calculated the approximate cost of the health benefits that could be saved in a less polluted environment.

3. Results

3.1. Air-quality profile

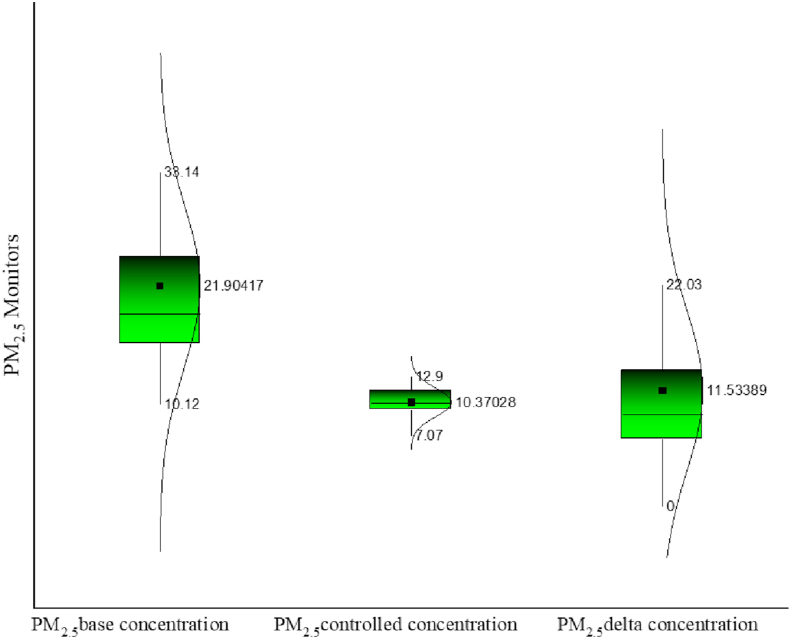

The PM concentrations (base values) recorded at the monitored sites, i.e. the quarterly-mean concentration of the base values, the controlled (≤15 μg m−3) values, and the quarterly-mean delta values, are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Air-quality profile.

3.2. Value of a statistical lifetime (VSL)

In the present study, the mortality estimates were derived from a US estimate per VSL. Since VSL estimates are sensitive to income variations, the US estimate was adjusted in order to obtain a country- and year-specific VSL estimate. Thus, the VSLPakistani,2017 was calculated with the aid of Eq. (2):

| (2) |

However, Eq. (2) can be written in the form of Eq. (3), since, over time, the income elasticity (ε) of the VSL (i.e., how sensitive VSL is to variations in the income), is the same (i.e., ε1 = ε2):

| (3) |

where VSLPakistan,2017 is given in Pakistani Rupee (PKR), and VSLUS, 1990 in the US dollar. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita (Y) is expressed as the purchasing power parity (PPP1990) index per international dollar, in PKR. The value of ε is constant, as 0.4. The consumer price index (CPI) is given for the years 2017 and 1990. According to the World Bank's database, the CPI for 1990 and 2017 is given as 17.7 and 156.9, respectively, and the value of PPP1990 is 4 (World Bank, 2006). The values of YPakistan,2017 and YUS,1990 are given as 1,222 and 36,312.4 respectively, and the VSLUS,1990 is given as $ 4,800,000.00 (U.S. EPA, 1999). Based on these values, the VSLPakistan,1990 is evaluated as US$ 318,388.00.

3.3. Estimate of the avoidable premature deaths and the related cost

The concentration of PM was reduced to as low as 15 μg m−3 and the health effects were monetized. The results of the analysis, which was performed in order to estimate the avoidable premature deaths associated to the economic valuations for the year 2017, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the analysis and its results in order to estimate the avoidable premature deaths associated to the economic valuations for the year 2017 (see the text).

| All-cause deaths | Deaths due to ischemic heart disease | Deaths due to lung cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Start Age | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| End Age | 99 | 99 | 99 |

| Point Estimate | 5,125.88 | 2,670.32 | 103.17 |

| Population | 73,262,448 | 73,262,448 | 73,262,448 |

| Delta | 9.20 | 9.20 | 9.20 |

| Mean | 5,120.29 | 2,667.66 | 102.63 |

| Baseline | 98,171.68 | 14,872.28 | 908.45 |

| Percent of Baseline | 5.22 | 17.94 | 11.30 |

| Standard Deviation | 798.56 | 223.94 | 27.26 |

| Variance | 637,705.63 | 50,151.24 | 743.15 |

4. Discussion

Pollution reduction policies sort the pollution variability in various ways. Nevertheless, in general, the peak pollution levels may be more affected than the lower levels (Davidson et al., 2007). The reduction policy based on the rollback-to-a-standard method is preferred for peak concentrations. As peak concentrations change over time, the results become more sensitive to the ordinality of the standard.

The next lines discuss the results shown in Table 1. It is observed that many deaths can be avoided by reducing the exceeding levels of PM2.5 to the hypothetical alternative PM2.5 standard of 15 μg m−3. More specifically, the age group (30–99) of 73,262,448 people was assessed, including all genders. The results were tabulated for all-cause, IHD, and lung-cancer mortality. The air-quality changes for PM2.5 was recorded as 9.20 μg m−3. These changes were evaluated for the exposure of a population as 100,000. The results show that 5,125.88, 2,670.32, and 103.17 cases of mortality due to all-cause, IHD, and lung-cancer, respectively, might be prevented. The baseline mortalities for the given population and the defined endpoints, such as all-cause, IHD, and lung-cancer-mortality were obtained as 98,171.68, 14,872.28, and 908.45, respectively. The standard deviations for the aforesaid mortalities were calculated as 798.56, 223.94, and 27.26, respectively. The variance for the above mortalities was obtained as 637,705.63, 50,151.24, and 743.15, respectively.

Consequently, assuming that the avoidable mortality linked to ischemic heart disease and lung cancer has been estimated as 2,773 (= 2,670 + 103) per 100,000 people, for a population of 73 million, the estimated avoidable mortality is 2,024,290. The mortality caused by all these causes can be associated with a total cost of US $1,000 million.

Αir-quality management ultimately aims at improving human health. This study showed that BenMAP-CE is a powerful tool for calculating effects on human health quantitatively and drawing up guidelines for future policy decisions related to community health in groups at regional, state, and national level. Indeed, the results of this study provide valuable data set, which might be of a great importance for urban, regional and global communities for air-quality modeling while suggesting at the same time possible strategies to improve the air quality of the local environment.

5. Conclusions

A total population of 73 million, covering the age group of 30–99, including all genders, was considered for the evaluation. Since there were no local health-related effect functions, the Krewski health function from the "Extended Follow-up and Spatial Analysis of the American Cancer Society Study Linking Particulate Air Pollution and Mortality" was used. The economic evaluation functions assigned a monetary value to the pooled and aggregated data on health effects. The statistical mean of the estimated values of the statistical life span and its distribution estimated the variance of the final assessment. The results showed that the avoidable mortality associated with ischemic heart disease and lung cancer was estimated as 2,773 per 100,000 people. In other words, the avoidable mortality is estimated as 2,024,290 for a population of 73 million. The estimated total cost related to the above mortality was US$ 1,000 million.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

A. Hassain, S.Z. Ilyas and A. Jalil: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

S. Agathopoulos, S.M. Hussain and S. Ahmed: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Y. Baqir: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaartion of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Abbey E., Ostro E., Petersen F., Burchette J. Chronic respiratory symptoms associated with estimated long-term ambient concentrations of fine particulates less than 2.5 microns in aerodynamic diameter (PM2.5) and other air pollutants. J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 1995;5:137–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneja P., Agarwal A., Roelle A., Phillips B., Tong Q., Watkins N., Yablonsky R. Measurements and analysis of criteria pollutants in New Delhi, India. Environ. Int. 2001;27:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0160-4120(01)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneja P., Schlesinger H., Erisman W. ACS Publications; 2009. Effects of Agriculture upon the Air Quality and Climate: Research, Policy, and Regulations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjum M., Ali S., Subhani M., Anwar M., Nizami A., Ashraf U., Khokhar M. An emerged challenge of air pollution and ever-increasing particulate matter in Pakistan; A critical review. J. Hazard Mater. 2020:123943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ArcGIS Desktop . Environmental Systems Research Institute; Redlands, CA: 2015. Release 10.2. [computer program] [Google Scholar]

- Arden C., Dockery D., Spengler J., Raizenne M. Respiratory health and PM10 pollution: a daily time series analysis. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1991;144:668–674. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.3_Pt_1.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw J., Kleeman J. Evaluating the first-order effect of interannual temperature variability on urban air pollution. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmosphere. 2003;108 [Google Scholar]

- Biswas F., Ghauri M., Husain L. Gaseous and aerosol pollutants during fog and clear episodes in South Asian urban atmosphere. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:7775–7785. [Google Scholar]

- ADB. Cai-Asia . Asian Development Bank; Philippines: 2006. Country Synthesis Report on Urban Air Quality Management-Pakistan. [Google Scholar]

- Carvour L., Hughes E., Fann N., Haley W. Estimating the health and economic impacts of changes in local air quality. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2018;108:S151–S157. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson K., Hallberg A., Mccubbin D., Hubbell B. Analysis of PM2. 5 using the environmental benefits mapping and analysis program (BenMAP) J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part A. 2007;70:332–346. doi: 10.1080/15287390600884982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dise N., Ashmore M., Belyazid S., Bleeker A., Bobbink R., Devries W., Erisman J., Spranger T., Stevens C., Van Den Berg L. The European Nitrogen Assessment: Sources, Effects and Policy Perspectives. Cambridge University Press; 2011. Nitrogen deposition as a threat to European terrestrial biodiversity. [Google Scholar]

- Dockery W., Cunningham J., Damokosh I., Neas M., Spengler D., Koutrakis P., Ware H., Raizenne M., Speizer E. Health effects of acid aerosols on North American children: respiratory symptoms. Environ. Health Perspect. 1996;104:500. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Environmental Agency . 2019. Eionet Core Data Flows.https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/eionet-core-data-flows-2019 [Google Scholar]

- Glad A., Brink L., Talbott O., Lee C., Xu X., Saul M., Rager J. The relationship of ambient ozone and PM2. 5 levels and asthma emergency department visits possible influence of gender and ethnicity. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health. 2012;67:103–108. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2011.598888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed S., Mirza I., Ghauri B., Siddiqui Z., Javed R., Khan A., Rattigan O., Qureshi S., Husain L. On the widespread winter fog in northeastern Pakistan and India. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2000;27:1891–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Haq U., Nazli H., Meilke K. Implications of high food prices for poverty in Pakistan. Agric. Econ. 2008;39:477–484. [Google Scholar]

- Hidy M., Pennell T. Multipollutant air quality management. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2010;60:645–674. doi: 10.3155/1047-3289.60.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell B., Fann N., Levy I. Methodological considerations in developing local-scale health impact assessments: balancing national, regional, and local data. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health. 2009;2:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Husain L., Dutkiewicz A., Khan A., Ghauri M. Characterization of carbonaceous aerosols in urban air. Atmos. Environ. 2007;41:6872–6883. [Google Scholar]

- Incecik S. Investigation of atmospheric conditions in Istanbul leading to air pollution episodes. Atmos. Environ. 1996;30:2739–2749. [Google Scholar]

- J W . Dallas Morning News; 2015. Dallas County commissioners jumping into debate over coal-fired power plants; p. 1A. October 18. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob J., Winner A. Effect of climate change on air quality. Atmos. Environ. 2009;43:51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kalimuthu K., Babu S., Venkataraman D., Bilal M., Gurunathan S. Biosynthesis of silver nanocrystals by Bacillus licheniformis. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2008;65:150–153. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsouyanni K., Samet M., Anderson R., Atkinson R., Le T., Medina S., Samoli E., Touloumi G., Burnett T., Krewski D. Health Effects Institute); 2009. Air Pollution and Health: a European and North American Approach (APHENA). Research Report; pp. 5–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly F.J., Fussell J.C. Size, source and chemical composition as determinants of toxicity attributable to ambient particulate matter. Atmos. Environ. 2012;60:504–526. [Google Scholar]

- Kleeman J. A preliminary assessment of the sensitivity of air quality in California to global change. Climatic Change. 2008;87:273–292. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig J., Mar T. American Thoracic Society; 2009. Relationships between Visits to Emergency Departments for Asthma and Ozone Exposure in Greater Seattle. B23. The Mechanisms and Health Effects of Ozone. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewski D., Jerrett M., Burnett T., Ma R., Hughes E., Shi Y., Turner C., Pope A., Iii, Thurston G., Calle E. Health Effects Institute Boston; MA: 2009. Extended Follow-Up and Spatial Analysis of the American Cancer Society Study Linking Particulate Air Pollution and Mortality. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Paciorek J., Koutrakis P. Estimating regional spatial and temporal variability of PM2. 5 concentrations using satellite data, meteorology, and land use information. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117:886. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar F., Larson V., Stier A., Claiborn C., Koenig Q. An analysis of the association between respiratory symptoms in subjects with asthma and daily air pollution in Spokane, Washington. Inhal. Toxicol. 2004;16:809–815. doi: 10.1080/08958370490506646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar F., Koenig Q., Primomo J. Associations between asthma emergency visits and particulate matter sources, including diesel emissions from stationary generators in Tacoma, Washington. Inhal. Toxicol. 2010;22:445–448. doi: 10.3109/08958370903575774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccubbin D., Force T. 2011. Health Benefits of Alternative PM2. 5 Standards. Report Prepared For: American Lung Association, Clear Air Task Force And Earthjustice. July, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mcmurry H., Shepherd F., Vickery S. Cambridge University Press; 2004. Particulate Matter Science for Policy Makers: A NARSTO Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal K., Mondal S., Samanta S., Mallick S. Synthesis of ecofriendly silver nanoparticle from plant latex used as an important taxonomic tool for phylogenetic interrelationship. Adv. Bio. Res. 2011;2:31–33. Synthesis. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer K., Neas L., Dockery D., Redline S., Tager I. The effect of air pollution on inner-city children with asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 2002;19:699–705. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00247102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris G., Youngpong N., Koenig Q., Larson V., Sheppard L., Stout W. An association between fine particles and asthma emergency department visits for children in Seattle. Environ. Health Perspect. 1999;107:489. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostro D. Air pollution and morbidity revisited: a specification test. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1987;14:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ostro D., Rothschild S. Air pollution and acute respiratory morbidity: an observational study of multiple pollutants. Environ. Res. 1989;50:238–247. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(89)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostro B., Lipsett M., Mann J., Braxton-Owens H., White M. Epidemiology; 2001. Air Pollution and Exacerbation of Asthma in African-American Children in Los Angeles; pp. 200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak-Epa . The Gazette of Pakistan; Islamabad: 2010. National Environmental Quality Standards for Ambient Air. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Pakistan, Pakistan Economic Survey . Finance Division; Islamabad: 2012. Economic Advisor's Wing. [Google Scholar]

- Pakistan Economic Survey. 2013-14. http://finance.gov.pk/survey/chapters_14/16_Environment.pdf

- Government of Pakistan, Pakistan Economic Survey . Finance Division; Islamabad: 2017. Economic Advisor's Wing. [Google Scholar]

- Peel L., Tolbert E., Klein M., Metzger B., Flanders D., Todd K., Mulholland A., Ryan B., Frumkin H. Ambient air pollution and respiratory emergency department visits. Epidemiology. 2005:164–174. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000152905.42113.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A., Dockery W., Muller E., Mittleman A. Increased particulate air pollution and the triggering of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;103:2810–2815. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitchford L., Poirot L., Schichtel A., Malm C. Characterization of the winter midwestern particulate nitrate bulge. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2009;59:1061–1069. doi: 10.3155/1047-3289.59.9.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope A., Iii, Burnett T., Thun J., Calle E., Krewski D., Ito K., Thurston D. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. Jama. 2002;287:1132–1141. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope A., III, Ezzati M., Dockery W. Fine-particulate air pollution and life expectancy in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:376–386. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0805646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffi M., Mehrwan S., Bhatti M., Akhter I., Hameed A., Yawar W., Hasan M. Investigations into the antibacterial behavior of copper nanoparticles against Escherichia coli. Ann. Microbiol. 2010;60:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnat A., Sarnat E., Flanders D., Chang H., Mulholland J., Baxter L., Isakov V., Özkaynak H. Spatiotemporally resolved air exchange rate as a modifier of acute air pollution-related morbidity in Atlanta. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2013;23:606. doi: 10.1038/jes.2013.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildcrout S., Sheppard L., Lumley T., Slaughter C., Koenig Q., Shapiro G. Ambient air pollution and asthma exacerbations in children: an eight-city analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006;164:505–517. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J., Neas M. Fine particles are more strongly associated than coarse particles with acute respiratory health effects in schoolchildren. Epidemiology. 2000:6–10. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setti L., Passarini F., De Gennaro G., Barbieri P., Perrone M.G., Borelli M., Clemente L. SARS-Cov-2RNA found on particulate matter of bergamo in northern Italy: first evidence. Environ. Res. 2020:109754. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard L., Levy D., Norris G., Larson V., Koenig Q. Epidemiology; Washington: 1999. Effects of Ambient Air Pollution on Nonelderly Asthma Hospital Admissions in Seattle; pp. 23–30. 1987-1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva A., West J., Zhang Y., Anenberg C., Lamarque F., Shindell T., Collins J., Dalsoren S., Faluvegi G., Folberth G. Global premature mortality due to anthropogenic outdoor air pollution and the contribution of past climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013;8 [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter C., Kim E., Sheppard L., Sullivan H., Larson V., Claiborn C. Association between particulate matter and emergency room visits, hospital admissions and mortality in Spokane, Washington. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2005;15:153. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone E., Schauer J., Quraishi A., Mahmood A. Chemical characterization and source apportionment of fine and coarse particulate matter in Lahore, Pakistan. Atmos. Environ. 2010;44:1062–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Texas Commission on Environmental Quality Revisions to the state of Texas air quality implementation plan for the control of ozone air Pollution,Dallas–fort worth eight-hour ozone nonattainment area. 2015. http://www.tceq.texas.gov/assets/public/implementation/air/sip/dfw/dfw_ad_sip_2015/AD/Adoption/DFWAD_13015SIP_ado_all.pdf Available at:

- United States Office of Air and Radiation November . 1999. Environmental Protection Office of Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Viidanoja J., Sillanpää M., Laakia J., Kerminen M., Hillamo R., Aarnio P., Koskentalo T. Organic and black carbon in PM2. 5 and PM10: 1 year of data from an urban site in Helsinki, Finland. Atmos. Environ. 2002;36:3183–3193. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M., Wake P., Kelly T., Salloway C. Air pollution, weather, and respiratory emergency room visits in two northern New England cities: an ecological time-series study. Environ. Res. 2005;97:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . The World Bank, South Asia Environment and Social Development Unit; Washington D.C: 2006. Pakistan Strategic Country Environmental Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Zhou X., Xu S., Huang H. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA internal medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanobetti A., Franklin M., Koutrakis P., Schwartz J. Fine particulate air pollution and its components in association with cause-specific emergency admissions. Environ. Health. 2009;8:58. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Quraishi T., Schauer J. Daily variations in sources of carbonaceous aerosol in Lahore, Pakistan during a high pollution spring episode. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2008;8:130–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Liu G., Shen W., Gurunathan S. Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, properties, applications, and therapeutic approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:1534. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.