Abstract

The paper investigates the aviation sector, as a case in point for a Smart environment and as an example for Industry 5.0 and Society 5.0 purposes. In the smart complex environments, a systemic vision of the elements, which act and are acted within a given territory, should be the basis of a hypothesis of joint growth. Indeed, the synergies activated by the system can be seen as the product of the application of a particular knowledge-based open innovation strategy, as an orientation capable of transforming theoretical assumptions into concrete operational innovation paths. Through the evidence emerged from an important case study and the application of an MCDA methodology, we have tried to identify which are the optimal solutions for the implementation of the new human-centric logics of I5.0, analyzing them on the basis of the actual benefits for the ecosystem, going beyond the self-referential aptitude of the firm to instill technological changes and managerial visions. Knowledge circulation, dialogue between sub-systems, and the ability to adapt technology and entrepreneurial strategies to the environment in which it operates (with the users as first stakeholders) seem to be necessary practices in knowledge-based innovation, prioritization, and decision-making processes, for smart, sustainable, and inclusive solutions.

Keywords: Smart environments, Knowledge circulation, Innovation ecosystems, Industry 5.0, Society 5.0, Techno-centric and human-centric innovations

Introduction

In scientific literature and business contexts, the “SMART” appellation is used as an acronym in order to evoke the characteristics of well-defined goals. The meaning of the letters that make this acronym is as follows: Specific (targeting a specific area for improvement); Measurable (quantifying or at least suggest an indicator of progress); Achievable (stating what results can realistically be achieved); Relevant (consistent with primary strategies and objectives); and Time-constrained (specifying when the results can be achieved) (Frey & Osterloh, 2002; Dezi et al., 2018). Some scholars and managers have extended the acronym to “SMARTER,” by adding Ethical (goals must sit comfortably within a moral compass) and Recorded (written goals are visible and have a greater chance of success. The recording is necessary for the planning, monitoring, and reviewing of progress) or Evaluated and Reviewed (these are both functions that foresee a constant control and a possible adjustment of the strategies in course of work) (Yemm, 2013). Since innovation is perceived as a vital factor for economic and social development of organizations, regions, and countries, it represents a mean for economic growth, productivity increase, knowledge creation, new occupations, and wealth proliferation. Innovation is also a means by which organizations seek to renew their management skills in particularly complex environments. Today’s economy is characterized by knowledge-intensive activities that contribute to an accelerated pace of technical and scientific advance, as well as rapid obsolescence; thus, the ability to manage complexity and uncertainty is not achieved through their negation. In this sense, innovation and knowledge in smart environments should be the result of a sharing process that involves all the actors of an ecosystem, interpreting complexity as an opportunity and not as a threat. This type of “openness” fits well with the new logics of I5.0, according to which human-centered solutions should be guaranteed for systemic and sustainable development. But if on the one hand we see the formation of industrial and institutional agreements which mostly refer to a “horizontal” openness, where B2B collaboration and knowledge sharing are often crucial for the survival of organizations, on the other hand, how much is the advance actually extended across all the dimensions of an entire ecosystem? How much are decision-making policies the result of common needs for the ecosystem? How do the prioritization processes of firms change if they actually consider the opinion of the beneficiary actors?

To investigate these dynamics of smart governance, knowledge, and decision-making in complex organizations, we have chosen to observe the “smart” realities of airport environments. The airport industry is characterized by the usage of a large amount of technology and prototypical solutions, so innovation is a necessary component for upgrading a sector in continuous fervor such as this. Indeed, with the advance of digital transformation, airport environments are at the forefront for the adoption of new technologies regarding Internet of things (IoT), Internet of Services (IoS), overall digitization, data analysis (handling, storing and sharing information through knowledge management practices), and cyber-physical systems (CPSs) for organizing, managing, and improving performance. Over the years, as the aviation industry has matured and grown, a balanced ecosystem has been built through constant growth, change, efforts, and advancements. This ecosystem is particularly suitable for our analysis because all the actors belonging to it are clearly detectable, considering a macro vision (connected countries and their commercial and passengers routes), a meso vision (regional and local dimension), and a micro vision (workers and passengers “living” the airport). Moreover, it emerged that the sector in question is an important business which, in some respects, can drive innovation policies in a systemic perspective. That is why smart environments, such as smart airports (SAs), need to pursue continuous innovation that helps them satisfy the complex ecosystem in which they are inserted.

Technology linked to a highly engineered field such as the airport industry has provided a number of evident inputs to implement its products and services. Nevertheless, the current globalized context, highly developed and mature, requires further efforts in this direction. Airports, in fact, are the real physical touch points between different nations and distant geographical areas, thus, if on the one hand the aforementioned digital transformation guarantees a continuous interaction, free from time and space, on the other hand, it is necessary that airports—as physical hubs of a global network—provide the best solutions for an exchange-centered connected world (of both human relations and knowledge). Thus, our aim is to analyze a SA as an environment resulting from a multiple process of innovation, divisible into endogenous technology-push innovations and exogenous demand-pull innovations (Sherer, 1982; Burgelman, 2002; Carayannis. et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2019). We focus in particular on the virtuous dynamics that can be activated by using both a user-driven innovation idea and a systemic perspective, aimed to set the development priorities of the organizations in an I5.0 context. We suppose that this could be a way to enable the decision makers to incorporate external knowledge and resources within their organizations’ boundaries, by investing on a number of improvements actually requested by the ecosystem. In order to do this, we propose a conceptual model and an operational toolkit able to systematize and standardize the prioritization procedures of complex organizations. We also believe that our studies may contribute to the discussion about management of innovation and decision-making policies within knowledge management, both in the specific observed sector and in other complex environments.

Therefore, the paper is organized as follows: the second section gives an overview of scientific literature dealing with open innovation and innovation systems in complex and smart environments, focusing attention on the participatory dynamics in which the firm is inserted and from which it must rethink its decision-making policies and knowledge exploration and exploitation practices. The third section illustrates data arising from the “Leonardo da Vinci—Rome Fiumicino Airport” case study, explaining the methodology used and informing about possible innovation paths for data analysis in decision-making processes. The fourth section discusses results, considering policy implications both for scholars and practitioners. Finally, the last section summarizes the main findings, with a look on research limitations and potentials for future research.

Literature Review

From Self-referential Paths to Exploration and Exploitation of Innovation Ecosystems

In general terms, innovation can be divided into two macro categories: “evolutionary” and “revolutionary.” Evolutionary innovations transform an existing product or service, making it cheaper, more efficient, faster, more exciting, more profitable, or more valuable. Revolutionary innovations (breakthrough), on the other hand, provide a sort of breakdown, re-organization, and partial restructuring of the hardware and software elements of a system, which are reconsidered and recombined to overcome obsolete standards that need a replacement (Schumpeter, 1928, 1934). Other scholars (e.g., Orcik et al., 2013) have framed these two ways of innovating as “incremental” innovation and “radical” innovation, keeping the meaning, in fact, unchanged. Smart environments use both of the aforementioned innovative logics, in order to create a synergic mix that triggers virtuous dynamics of value creation, by identifying the best combination of technology and sustainable development, from an economic, social, and environmental point of view (Etzkowitz, 1998; Carayannis et al., 2003; Carayannis & Gonzalez, 2003; Cooke et al., 2004; Etzkowitz & Klofsten, 2005; Carayannis & Campbell, 2005; Ferraris et al., 2017). Recognizing the need for a systemic vision is the first step towards an optimal knowledge management, so it is necessary to leave behind the obsolete management approaches that were based on a more or less clear division of objectives, compared with those shared by the community and reachable with the community.

An overall development trend is that the dominant innovation policy model, based on a linear concept and a focus on science-push and supply-driven high-tech policy, is enhanced and complemented by a new broader approach than before. Among the most authoritative scientific contributions, some authors have named this new emergent approach: broad-based innovation policy, open innovation, and innovation ecosystems. The broad-based approach means that also non-technological innovations, such as service innovations and creative sectors, are becoming more attractive for the innovation policy targets. Broad-based innovation policy must be extended to incorporate wider societal benefits and to support service innovation in the public service production (Panati & Golinelli, 1988; Edquist et al., 2009; Viljamaa et al., 2009; Santoro et al., 2018).

The open innovation paradigm can be considered as “the antithesis of the traditional vertical integration model where internal R&D activities lead to internally developed products that are then distributed by the firm. […] It is a paradigm that assumes that firms can and should use external ideas as well as internal ideas, and internal and external paths to market as they look to advance their technology” (Chesbrough et al., 2006). According to these authors, open innovation processes lead to new architectures and systems within which the creation of added value is nothing but the translation of a constant dialogue with the outside world. The open innovation paradigm considers research and development as an open system. Indeed, open innovation suggests that valuable ideas can be developed from an exogenous process. Also, with regard to knowledge management processes, the open innovation assumes that useful knowledge is widely distributed and that “even the most capable R&D organizations must identify, connect to, and leverage external knowledge sources as a core process innovation” (Chesbrough et al., 2006). This means that ideas that once sprouted only inside the firm boundaries now can be searched from the efforts of an individual inventor to partners and hi-tech start-ups, to research facilities of academic institutions, up to the end users and the wide society, for a more sustainable contribution to the advancement of knowledge. In relation to this, Cohen and Levinthal (1990) have written about the “absorptive capacity,” as a propensity to actively consider the “two faces” of R&D (which include the advancement of knowledge both from an internal and external perspective to the organization), by exploiting the knowledge that develops from the outside. The essence of taking advantage of knowledge sharing in open innovation systems should be the today’s ability to overcome closed models of innovation, so as to avoid once and for all the risk of limiting progress, as some scholar noted in the not invented here (NIH) syndrome that often accompanied the typical Chandlerian model of deep vertical integration of R&D for economies of scale and scope (Katz & Allen, 1985; Rosembloom & Spencer, 1996). In this regard, Langlois (2003) has documented the “post-Chandlerian firm,” in which innovation processes and information flows are developed in an open and participative way. According to Chesbrough et al. (2006), although later theories of absorptive capacity never specified what the balance between internal and external innovation sources ought to be, in open innovation systems, external knowledge should play an equal role to that afforded to internal knowledge.

The innovation ecosystem concept derives from the general concept of system, which was initially studied by von Bertalanffy (1968)1 in the field of natural sciences. According to this perspective, a system is composed of a set of elements and a set of relations among these elements. Thus, systems analysis is essentially the exercise of identifying and characterizing elements and their relations. Furthermore, another common description of a dynamic open system is in terms of transformation of inputs into outputs through activities performed by agents or actors interacting with an environment. In relation to specific business contexts, Von Hippel (1988) has identified four external sources of useful knowledge: (1) suppliers and customers; (2) university, government, and private laboratories; (3) competitors; and (4) other nations.

Among the authors who have dealt with innovation systems more recently, de Vasconcelos Gomes et al. (2018) argue that the innovation ecosystem concept puts (more) emphasis on value creation and collaboration. Walrave et al. (2018) define innovation ecosystem as a network of interdependent actors who combine specialized yet complementary resources and/or capabilities in seeking to (a) co-create and deliver an overarching value proposition to end users and (b) appropriate the gains received in the process. Granstrand and Holdersson (2020) also consider the naturally competitive part that occurs in ecosystems (as complex entities), stating that an innovation ecosystem is the “evolving set of actors, activities, and artifacts, and the institutions and relations, including complementary and substitute relations, which are important for the innovative performance of an actor or a population of actors.” In this definition, artifacts include products and services, tangible and intangible resources, technological and non-technological resources, and other types of system inputs and outputs that lead to innovation.

Many organizations have embraced open innovation, so as many scientific contributions have emphasized and demonstrated the importance of this perspective. But it is clear that the intensity of this openness could vary from case to case; moreover, today, there are no commonly established paths to take advantage of the added value of such (eco)systemic synergy. That makes it even more urgent to definitely overcome closed and self-referential visions.

The Need for Industry and Society 5.0 Approaches to Decision-Making

When it comes to innovation ecosystems and open perspectives, the novel paradigms of Industry 5.0 (Carayannis et al., 2021; EU Report on Industry 5.0, 2021) and Society 5.0 (Onday, 2019; Fukuyama, 2018) can be considered as the answer to the demand of a renewed human-centered/human-centric industrial paradigm, starting from the (structural, organizational, managerial, knowledge-based, philosophical, and cultural) reorganization of the production processes to then generate positive implications first within the business perspectives and secondly towards all the components belonging to the ecosystem. Several scholars (Fauquex et al., 2015; Vitali et al., 2017; Taratukhin et al., 2018; Nahavandi, 2019; Walch & Karagiannis, 2019) have emphasized the importance and role of modifying the innovation management framework with a focus on human/user centeredness. For instance, Skobelev and Borovik (2017) and Ozdemir and Hekim (2018) have discussed the role and importance of I5.0, which is more human-centered as compared with Industry 4.0 (I4.0) just because I5.0 helps to connect open innovation and technological policies with the overall corporate strategy of the firms, thus creating a suitable environment and ecosystem. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2005) first introduced the concept of “implement-ability” of innovation, which means that innovation should create value for its users and that if innovation is not creating any value or bringing any change in the lives of its users, then it cannot be regarded as true innovation. The concept of implement-ability of innovation puts the customer or user at the center of the whole innovation management process.

Other contributions in this direction derive from human-centered design (HCD) and design thinking (DT). HCD is an approach to design and innovation in which an understanding of potential users drives decision-making (Gasson, 2003; Dym et al., 2005). This understanding typically emerges through user research by the systematic study of the attitudes, behaviors, and desires of potential users. In contrast to the aforementioned approaches such as “technology-push,” in which organizations begin with the technology and then find applications for it (Martin, 1994), in HCD, user research provides a critical foundation for every subsequent step of the development processes of products or services. However, the influence of user research depends on its visibility and credibility to decision makers. Similarly, DT is an approach aimed to address innovation processes, and, given its capability to respond to the complexity of the current business scenario (Waidelich et al., 2018), the interest on this concept is growing. Substantially, DT tends to break the rules to rewrite new ones (Brenner & Uebernickel, 2016). This should mean going beyond the old orientations of those business models that foresee the development of completely in-house solutions, going beyond the short-sightedness of those business environments that do not consider openness as an added value for innovation itself (as happens in case of the NIH syndrome), and going beyond the closure of an entrepreneurial perspective that evaluates the efforts made in innovation only through profitability and feasibility criteria. Firms that decide to adhere to an Industry 5.0 perspective for the implementation of new products and services (or even new production models) need to ensure the active participation, commitment, and involvement of external actors (and their respective subsystems), which included those who will actually be the end users, so that they can contribute to design and develop solutions. Inevitably, once a solution is implemented this way, it will match better to the actual needs of the customers, since their ideas and their experiences of use may contribute to a “fine-tuning” design process, which would be human-centric from the beginning, as responsible innovation (Grunwald, 2011; Blok & Lemmens, 2015; Ceicyte & Petraite, 2018; Rivard & Lehoux, 2020).

Another relevant concept for the implementation of I5.0 inclusive solutions is that of user-driven innovation. In this regard, it is crucial to realize that users can be defined and identified in several ways: depending on the context, users can be ordinary or amateur users, professional users, consumers, employees, hobbyists, businesses, other organizations, civil society associations, or simply residents and citizens. Eason (1987), for example, already differentiated three categories of users: (1) primary users, those likely to be frequent hands-on users of the system; (2) secondary users, those who use the system through an intermediary; and (3) tertiary users, those affected by the introduction of the system or who will influence its purchase. In order to further justify the contribution of users (in a broad sense) with respect to innovation processes, we can refer to Rosted (2005), who has argued that one can talk about user-driven innovation when a company utilizes knowledge on user needs in its innovation processes, through scientific and systematic surveys and tests. In other words, from an I5.0 perspective, user involvement can range from the systematic collection and utilization of user information to the development of innovations by users themselves, as value co-creation (Eriksson & Svensson, 2009; Svensson et al., 2010). Obviously, user research will not only guide the development of products/services according to their technical characteristics, but they will also serve to satisfy wider social expectations, referable to the social and community fabric, as a systemic dimension.

The Quintuple Helix Model for the Circulation of Knowledge Within Complex Environments

When we talk about knowledge management and decision-making processes in complex environments, we can refer to the contribution of Simon (1969), who argued that complexity occurs when a large number of parts interact in a non-simple way. Furthermore, when these parts or their intricacy are too large to be managed simply, complexity becomes a challenge for rational decision-making. With this first assumption, although a large amount of data are gathered, a decision based on a substantive rational calculation is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve (Stevens, 2014). In innovation evaluation in practice, the importance of measuring innovation is increasingly gaining the attention of managers and consultancies, since complex indicators are indispensable for organizations to generate, manage, and control knowledge flows.

Despite many attempts to identify some innovation measures (Andrew et al., 2008, 2010; Chan et al., 2008; Bange et al., 2009; Dziallas & Blind, 2019), existing analyses demonstrate that rethinking a business’s innovation measurement system is crucial (Dewangan & Godse, 2014). Moreover, even according to the practitioners, academic research does not indicate a common overall innovation measurement framework or can only provide theoretical contributions and unclear applications (Dodgson & Hinze, 2000; Adams et al., 2006; Becheikh et al., 2006; Cruz- Cázares et al., 2013). Often, another reason for the difficulty in managing knowledge for innovation is the unavailability of data and methods (Andrew et al., 2008; Birchall et al., 2011; Edison et al., 2013). Therefore, the use of indicators, as the source of information and knowledge from which one can detect priorities in the innovation system (Borrás & Edquist, 2013), can be a potential solution for decision evaluation in complex environments.

The most well-known manual of international innovation indicators was conceived by the OECD’s “Oslo Manual 2005,” which contains guidelines for gathering and using information about innovation and knowledge management activities. In this regard, a concrete example of innovation measurement is the European Innovation Scoreboard (EIS). The indicators are based on the CIS2 to compare the innovation performance of EU countries and those of the USA and Japan, focusing on national and regional comparisons (Hoelscher & Schubert, 2015).

However, although the EU has considered some external sources that allow the generation, exploration, and exploitation of knowledge, their approach lacks an adequately systemic vision. For example, there are no references to end user active participation in the circulation of knowledge, and it is assumed that innovation measurements always take place ex-post, when the decision-making processes have already been concluded. From this point of view, ex-ante should refer to the front-end of the innovation process, as the generation, screening, sharing, and evaluation of ideas and concepts for innovation (Khurana & Rosenthal, 1998; Reid & De Brentani, 2004), from which the ideas enter the formal development process to start the developing procedure and to commit resources (Eling et al., 2016; Van Oorschot et al., 2018). Thus, in an open perspective, there is the need for developing new and different metrics as well as composite indicators for assessing the performance of a firm’s innovation process, by integrating the classic metrics, strictly connected to internal R&D and product/service development (including the ex-post customer satisfaction), with those metrics that can assess the long run absorptive capacity of the organization.

Because of our need for a conceptual framing that takes into account the ex-ante and in-itinere phases, when we consider the open innovation ecosystems in a new I5.0 approach, we have chosen to take advantage from the application of the spiral-shaped innovation models. The first reference is to the Quadruple Helix model (Carayannis & Campbell, 2009; Yawson, 2009; Arnkil et al., 2010; Carayannis & Campbell, 2010; 2012; Campanella, et al., 2017). It is a model that considers (1) Industry, (2) Government, (3) University, and (4) Public (the first three were already included in the Triple Helix model) (Leydesdorff and Meyer, 2006). Its theoretical evolution led to the Quintuple Helix model (Carayannis et al., 2012; Carayannis & Rakhmatullin, 2014; 2018), which is able to consider all the actors and elements of a (eco)system that move in synergy by contextualizing the Quadruple Helix and by additionally including the helix of the (5) natural environments of society. This fifth aspect represents a further attempt to highlight the dynamics connected to the territorial characteristics in which the firms operate and a new attention to a sustainable overall progression. According to Carayannis et al. (2017), a systemic vision that takes into account these dynamics boosts the direct relationship with the territory and the co-creation of value, for a joint growth. Within the framework of the Quintuple Helix innovation model, the five propellers should be seen as drivers for knowledge production and innovation, in creating a win–win situation between the organization and its ecosystem, as well as among different subsystems. Furthermore, the development of the “natural capital” should allow a better adaptation of the business to the territorial prerogatives (as envisaged by a system-driven perspective), favoring an optimal exploitation of the strengths present in the territory and an optimal management of the risks linked to the weaknesses of it (Moulaert & Sekia, 2002; Castanho et al., 2019; Carayannis et al., 2019). This consists of adopting the aforementioned smart approach, initially at a first level of depth, which concerns the operations of each separate system (firms, public authorities, universities, consumers/users and environmental characteristics); then, at a more inclusive level, it is necessary to evaluate the feasibility in the joint areas. In fact, it is not so obvious that the winning strategies of a subsystem must be profitable, feasible, and desirable for the other dialoguing areas. The basis of this observation is the activation of the propulsive boost deriving from the synergistic action of the single elements involved, right in a systemic way.

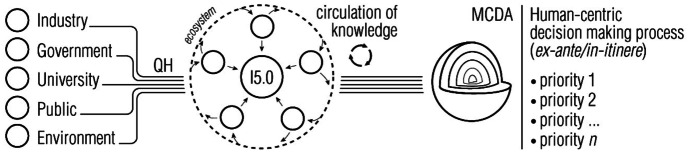

As explained in our purpose, in an attempt to identify an innovative theoretical and operational toolkit capable of effectively responding to the implementation requisites of new smart environments from an I5.0 perspective, we have advanced a new model originating from the combination of the principles of the MCDA approach with the framing of the QH innovation ecosystem. In particular, we have applied the specific rules of an open innovation deriving from a participatory and synergic ex-ante/in-itinere process to the five helices involved, taken both individually and jointly in relation to their (eco)systemic nature. The MCDA method is placed at the center of the model, as the result deriving from the interactive propulsive thrust of the five subsystems (Industry, Government, University, Civil Society, and Environment). The I5.0 approach, instead, is considered as a frame, a constant superset that regulates the interaction among the individual subsystems and promotes the participation of all the stakeholders who are involved in various capacities and who contribute to feed the circuit of knowledge creation and sharing (Fig. 1).

Industry

Fig. 1.

The Quintuple Helix model for I5.0 smart inclusive solutions

In the past, other scholars have already studied the use of alliances (Gerlach, 1992) and the construction of networks by firms (Gomes-Casseres, 1996; Powell et al., 1996; Noteboom, 1999) as another means of actively seeking out and incorporating external knowledge into the innovation processes of the firms. In fact, close and early engagement with other organizations and suppliers can allow access to knowledge not available in-house (Uyarra, 2010), and the joint added value is higher the more firms apply similarity strategies (Xu et al., 2019) and the more they share borders and systems (Brown et al., 2020).

Government

Government intervention, with respect to stimuli to innovation (through tax relief, disbursement of funds, etc.), is a particularly visible practice to encourage joint growth and largely social benefits among the actors involved in the ecosystem (Szczygielski et al., 2017; Jugend et al., 2018), both at an entrepreneurial level and in government-funded university research (Fleming et al., 2019). In addition, it is well known that public sources are also an important source of knowledge, for example, government R&D spending was identified as an important stimulus for private R&D (David et al., 2000).

University

Similarly, University and its research are often explicitly funded by companies (as well as by the governments) to generate external spillovers (Colyvas et al., 2002; Tseng et al., 2020). Its ability to update knowledge and provide incubators for innovation and growth has been widely studied (e.g., Jaffe, 1989; Jensen & Thursby, 2001; Belenzon & Schankerman, 2009; Kolympiris & Klein, 2017).

Public

Consulting with customers who are lead users can provide firms ideas about discovering, developing, and redefining innovation (von Hippel, 1988). This has meant a transition from policy models looking for an internal point of view to a perspective that should take systematically into account the users and their demand-pull points of view (even in accordance with the progressive push of technology and the in-house strategies). Also in this case, the need for communication and sharing is the more important the greater the number of parties involved and the greater the need for user engagement (Caldwell et al., 2009). Furthermore, as previously stated, the basis of the principles of I5.0 is the awareness that a sustainable value can only be maintained over time through a profound knowledge of social aspects inherent in the ecosystem (Stock et al., 2016; Hyysalo et al., 2017; Halbinger, 2018).

Environment

Attention to the environment and its long-term sustainability is a particularly hot topic in today’s scientific literature and research (Vanegas, 2003; Nyberg & Wright, 2013; Bekuna et al., 2019; Liu, 2019; Polasky et al., 2019; Farley & Smith, 2020). The importance of rethinking policies and models of production concerns any business and institutional organization, and it is an expression of the contagious sensitivity of the consumer society.

Research Methodology

This article tries to answer the question how to manage the knowledge deriving from different intra-systemic and inter-systemic flows. Considering the need of today’s organizations to adopt an approach that should be increasingly focused on I5.0, how to implement inclusive solutions that systematically take into account the actual degree of desirability expressed by the stakeholders involved? Again, how to insert these variables in development prioritization processes, making them more open to sharing innovation and knowledge?

To do so, we have chosen to analyze the airport public sector, as a sector made up of complex smart organizations in which many actors operate in a systemic perspective: government (local, regional, national, and international institutions), industry (various suppliers, direct partners, airline companies), university (direct and indirect value co-creation), civil society (workers and highly skilled employees, passengers and tourists, local communities, interest groups), and general environmental context (environment as a local and global resource). “The sixth continent” is how the Economist (2014) has defined the world’s airports and the perpetual transitory people who live in it, even if intermittently. According to the International Air Transport Association, in 2019, passengers were more than 4.5 billion (IATA, 2019), with the demand (4.2%) that has grown faster than capacity (3.4%). It is an amount that is larger than the population of Asia, the most populous of the five continents. IATA expected that by 2035 passengers will raise to 7.2 billion, while by 2024, China will surpass the USA as the first air market and India will surpass the UK as a third (IATA, 2017). In 2019, the global air transport has generated a revenue of $838 billion.3A glaring example of such development is given by the tremendous growth in low-cost travel, which has met the needs of an always-increasing number of travelers and (B2B) stakeholders.

Within this particular fervent sector, in order to simulate a data collection on actual experiences and expectations expressed by end users, useful for a firm to include their preferences in decision-making processes, we have monitored the travelers of Rome Fiumicino Leonardo Da Vinci international airport. This SA has reached 43 million passengers in 2018, with a 4.9% increase compared with 2017. Contributing to driving, this progress has been long-haul traffic, which is increased by 14.4%. Good results have been achieved for goods transport too, which have risen by 10.9% compared with the previous year and have surpassed 200,000 tons (AdR, 2019). Thus, the Leonardo Da Vinci airport has all the rights to be considered a SA (CENSIS, 2017), also because ACI World (Airports Council International) has announced the airport winners of the prestigious 2018 Airport Service Quality (ASQ) Awards and the ACI Europe 2018 Best Airport Award, and the top spot has gone to Rome Fiumicino Leonardo da Vinci Airport (ACI, 2018).4 In addition to this, it has been 1st in the ranking of the Top 10 World’s Most Improved Airports, according to the 2018 World Airport Awards by SkyTrax.5

Our survey has been conducted for an 11 months period,6 until the unexpected outage due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It has reached a random sample of 1732 travelers, coming from 48 different nations and all continents. The heterogeneity of the sample has guaranteed the coverage of all age groups, including different travel frequencies. Also, the variable travel reason has allowed intercepting the specific target of the business users. A multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) and a cluster analysis (CA) have been applied to better frame the respondents’ attitudes in relation to the main priorities for a comfortable experience, the prior aspects that a SA should improve, and the level of satisfaction of some macro-categories.

Furthermore, we have performed a content analysis on the airport’s official “long-term investment program” (AdR-ENAC, 2011, 2016, 2019), a detailed document drawn up by the “Aeroporti di Roma” (AdR) company and approved by “ENAC”7 for the decade 2012–2021.8 We have considered 75 planned interventions, having chosen to exclude those relating to safety and extraordinary maintenance. Each intervention has been comprised in one of the following macro-categories: (1) urban activities, (2) airside infrastructure, (3) interventions on the terminals, (4) landside infrastructure, (5) interventions for the environmental sustainability, (6) interventions on parking areas, (7) hi-tech/hi-skill smart solutions.9 Each investment has been analyzed with regard to its degrees of desirability, feasibility, and profitability.10 In addition, the impact of each intervention has been measured in relation to the QH intensity (with reference to the synergic combination of subsystems actually involved).

Finally, after assigning specific weights to the selection criteria (QH = 0.290; desirability = 0.428; feasibility = 0.218; profitability = 0.064),11 a multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) with analytical hierarchy process (AHP) has been conducted, in order to simulate an in-itinere prioritization process guided by a systemic human-centric innovation model.

Results and Discussion

The nature of the aspects investigated allowed us to group the items into 4 macro-categories: (1) outside services, (2) basic services, (3) hi-tech services, and (4) extra services.12 The first interesting aspect of the survey is related to the different priorities expressed depending on whether the current user experience or expectations on future innovation priorities are considered.

The former refer to those priorities of the travelers that recall specific items of an airport experience based on primary services, i.e., services directly related to the core activities of the airport in connection with the airline companies (industry system) and the territory (environment system). Indeed, 55.9% of interviewees appreciate Smart booking/payment/check-in services, 52.5% are interested in an effective connection between the airport and the city, and 50.9% consider a guaranteed secure environment as a prior aspect. Good airport’s hospitality and entertainment services, a fast boarding process, and the possibility to have real-time information systems are just as important for most of them. The most negligible services seem to be those additional secondary services, like car rent and parking, which are not likely to be used often.13 In other words, these users have expressed some basic expectations without considering those aspects as real innovation points. Technology, for example, has been a very marginal aspect within their initial requests.

Conversely, the respondents’ choices connected with the prior aspects that the SA should develop in the near future refer to both purely technological and infrastructural enhancements, as well as extra services. Indeed, 48.9% of the interviewees require some interventions in modernization and extension of infrastructure endowments, 44.4% demand a passenger-specific retail and hospitality services, and 37% hope for a better physical connection between the airport and the city. The interest towards a good connection between the airport and the city represents a very relevant aspect, which refers to the airport ability of activating a network improvement through an advancement of the transportation network, which is one of the first concrete connecting links between the airport infrastructure and the environment in which the airport is included. This refers to the fourth and fifth helix of the Quintuple Helix model (community and environment), that is the territory itself. According to this ambidextrous perspective (Simsek, 2009; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013; Boemelburg et al., 2019; Gomes et al., 2020), an implemented innovation inside and outside the SA, with specific reference to its infrastructure endowments, will provide a spillover effect able to stimulate a joint growth, the way it is interpreted in an ecosystem-based innovation processes.

Considering the satisfaction degree of the different items, we have observed a significant correspondence between the importance of the smart booking/payment/check-in service and its respective satisfaction level (mean value = 3.818). The same relationship counts also for the airport security (mean value = 3.729), airport’s restaurant services (mean value = 3.538), and stores and retail services (mean value = 3.498). Instead, the boarding procedure and its timing appear to be conflicting because users consider them an important service and, at the same time, the most unsatisfying item (mean value = 1.767).

The Overall Satisfaction Index has reported a prevalent medium level of satisfaction (MS = 71.2%), followed by 22.1% of low satisfaction (LS) and 6.7% of high satisfaction (HS). This evidence highlights the need for improving the overall performance and the necessity for ordering in priority all the services according to the expectations of the users (as viable through demand-pull innovation strategies) (Table 1).

Table 1.

User characteristics and attitudes in relation to the aspects investigated (analytical and synthetic levels)

| Gender | Actual user priorities (up to 5 alternatives) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 44.3% | Luggage traceability | 4.6% |

| Male | 55.7% | Good airport’s hospitality services | 9.7% |

| Age groups | Luggage storage | 3.4% | |

| 18–30-year-olds | 32.8% | Digital apps with interactive contents | 5.2% |

| 31–45-year-olds | 29.0% | Stores and retail services | 8.9% |

| 46–60-year-olds | 24.0% | Real-time information | 8.6% |

| Over 60-year-olds | 14.2% | Good airport’s entertainment services | 8.3% |

| Place of origin | Connection with the city events | 2.3% | |

| Europe | 59.5% | Guaranteed secure environment | 10.2% |

| Italy | 22.1% | Good airport's restaurant services | 5.4% |

| South America | 16.3% | Fast boarding | 9.0% |

| North America | 12.7% | Good parking services | 1.1% |

| Asia | 8.2% | Smart booking/payment/check-in | 11.2% |

| Oceania | 3.1% | Effective connection between the airport and the city | 10.5% |

| Africa | 0.2% | Car rent | 1.5% |

| Travel frequency | Future innovation priorities (up to 3 alternatives) | ||

| 1–3 a year | 49.8% | Information and connection with the city events | 2.3% |

| 4–6 a year | 38.9% | Beacon/location-based technologies | 7.3% |

| Over 6 times a year | 11.3% | Physical connection with the city | 12.4% |

| Travel reason | Faster boarding | 5.7% | |

| Holiday travel | 87.8% | Connection with the city business | 4.9% |

| Business travel | 12.2% | Wayfinding and real-time notifications | 5.3% |

| Satisfaction index (1–5 Likert scale) | Passenger-specific retail and hospitality | 14.8% | |

| Boarding timing | 1.767 | Virtual mapping services | 1.2% |

| Parking services | 2.021 | Pollution abatement and sustainable energy | 8.3% |

| Digital apps with interactive contents | 2.303 | Outside services (parking, malls, hotels, etc.) | 4.5% |

| Connection with the city events | 2.324 | Overall airport entertainment | 6.4% |

| Luggage storage | 2.434 | Luggage traceability | 1.1% |

| Car rent | 2.472 | Modernization/extension of infrastructure endowments | 16.3% |

| Connection between the airport and the city | 2.604 | Airport security | 5.3% |

| Airport's entertainment services | 2.774 | Virtual (personal) assistance | 6.2% |

| Airport's hospitality services | 2.778 | Actual demand aggregated | |

| Luggage traceability | 2.824 | Outside services | 13.1% |

| Real-time information | 2.850 | Basic services | 40.1% |

| Stores and retail services | 3.498 | Hi-tech services | 20.7% |

| Airport's restaurant services | 3.538 | Extra services | 26.1% |

| Airport security | 3.729 | Future innovation demand aggregated | |

| Booking/payment/check-in | 3.818 | Outside services | 26.9% |

| Basic services | 16.6% | ||

| Respondents = 1732 |

Hi-tech services Extra services |

31.9% 24.6% |

|

In order to discover the underlying links among these dimensions, we applied a MCA. It returned 3 main factors, which explain 27.45% of the overall variance. Their interpretation has been as follows:

F1: High satisfaction vs low satisfaction (14.83% of the variance)

F2: Basic demand vs premium demand (6.62% of the variance)

F3: Holistic-systemic improvement vs specific-isolated improvement (6% of the variance)

Based on these three different factors, we have conducted a CA with hierarchical mode. Its results have permitted the separate identification of 5 targets of users, from which the firm can draw knowledge and through which its prioritization strategies can be defined:

Tech enthusiasts (32.9%)

The first target group is related to those users who clearly request an improvement of the hi-tech envelopes (Papa et al., 2018). They are primarily males and belong to the youngest age group (18–30). They decline to allocate future resources for basic services, which appear to be already implemented enough (as confirmed by a medium degree of overall satisfaction and by specific expectations for the inherent items). According to this target group, that is about one-third of the entire sample, lack of efficiency and effectiveness could be at least attenuated by introducing new sophisticated tools. These tools can include, e.g., self-service facilities, automatic services, and industrial automation. In this case, demand-pull-based requests can interact, merge, or even partially coincide with a technology-push innovation vision.

-

2.

Pro users (9.1%)

The second target group mostly refers to those users who travel for work-related reasons. These travelers seem to be satisfied about all aspects of the airport environment, including boarding timing, which has presented the lowest satisfaction degree. Indeed, a high level of overall satisfaction represents the ability to be highly accustomed. They are primarily males and probably they used to positively comply with the necessary waiting time for boarding by using luggage storage services and enjoying some secondary hospitality and entertainment services. As suggested by the data, it could be more profitable to set specific premium strategies especially for groups like this one, which is composed of users who travel more than three times a year.

-

3.

Immersive UX (27.3%)

The third target group, that is the second largest group of the cluster analysis, is characterized by adult females 31–60-year-olds. They embody the immersive one user experience (UX), which is to be understood in a broad sense. The main reason for travelling is holiday, so these users seem to consider the airport experience as an integral part of the trip (as supported by the experiential marketing theories). They particularly appreciate stores and retail services, followed by a good opinion for restaurants and entertainment services. They do not encourage innovation in hi-tech nor basic services; instead, they tend to desire an additional investment in extra services (within the airport). According to this perspective, a smart airport should include within its boundaries a more massive commercial and leisure complex, which could be enjoyed also by non-passenger users.

-

4.

Outer-directed users (10.5%)

The fourth target group is related to those users who embrace the whole airport supply services as they are. They could correspond to the late majority and laggards already introduced by Rogers (1962).14 In our sample, they are primarily aged over 60 and they travel up to three times a year. Despite they appreciate most of the services provided by the airport network (both inside and outside the physical structure), they tend to prefer basic services and appear slightly hesitant to appreciate hi-tech solutions.

-

5.

Need-directed users (20.2%)

The fifth target group is characterized by strong values of low satisfaction, both for the overall satisfaction level and the single items. These users seem to be outsiders of the airport experience. They see the airport as a mere necessity, a simple mode of transportation. Therefore, their requests concern only basic needs and respective services. This is why we named them need-directed users. In this case, managers have to improve engagement strategies (also by enhancing the embrace of the territory) in order to allow the overcoming of the users’ skepticisms (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Projection of active variables and clusters on factorial axes (F1-F2; F1-F3; F2-F3)

The results of the survey have been considered as the starting point for the measurement of desirability, given that the end users represent the first stakeholders (Elliot & Radford, 2015; van Mierlo, 2019) to whom SA’s services will be offered and provided. Furthermore, if the model is applied ex-ante, the sample of users will be able to provide information not only in relation to the order of development priorities but also regarding what to develop and what not, contributing more to the optimal allocation of the organization’s resources. After establishing the weights of the single selection criteria, each considered alternative of the “long-term investment program” has been in turn measured by a pairwise comparison. The four average scores obtained by each alternative for the four observed dimensions have been normalized and aggregated through a weighted average, respecting the weights of the same four criteria (De Montis et al., 2000; Frazão et al., 2018; Watróbski et al., 2019). In this way, MCDA has returned a ranking based on an overall prioritization index (PI), with a reliable consistency index (CI ≤ 0.05).15 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prioritization Index (MCDA with QH intensity, desirability, feasibility, and profitability criteria)

| Ranking | PI | Description of the interventions |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | 0.672 | Atlantia project for academic institutions partnership (Politecnico di Torino, Politecnico di Milano, Università di Firenze, Università di Pisa, Università di Roma—Tor Vergata, Università di Roma—Sapienza, LUISS Guido Carli) |

| 2nd | 0.654 | Interconnected monitoring of digital apps |

| 3rd | 0.653 | “E-Gates.” Implementation of biometric scanner systems for arrivals and departures |

| 4th | 0.645 | Realization of guided tours in the park through touch screen monitors and projections of informative and interactive clips for educational purposes on the airport's environmental impact reduction activities |

| 5th | 0.634 | Cargo city road improvement Fiumicino-Rome highway |

| 6th | 0.632 | New partnership “Cinema in aeroporto” (University of Rome—Roma Tre, DAMS Department) |

| 7th | 0.631 |

New partnership “Flight Academy”—University of Roma—Sapienza, Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (DIMA) |

| 8th | 0.628 | Realization of IT support platforms defined at EU level by Eurocontrol |

| 9th | 0.627 | New separate waste collection system |

| 10th | 0.599 | Creation of an environmental park within the airport grounds |

| 11th | 0.598 | Construction of a medical center |

| 12th | 0.590 | Led lighting for the entire airport area |

| 13th | 0.588 | Fiumicino North hi-tech systems for the management of flows and queues |

| 14th | 0.587 | Fiumicino North new self-acceptance and security area with advanced tech-systems |

| 15th | 0.586 | Optimization of natural ventilation, use of rainwater and microclimate control |

| 16th | 0.582 | Wider sidewalks and use of herbaceous essences and compatible diffused green |

| 17th | 0.579 | “GRTS people mover” for rail transport, intra-airport light rail, Fiumicino city and Fiumicino cruise port (capacity: 6100 pax) |

| 18th | 0.578 | “GRTS people mover” for East area—Fiera di Roma—Roma Lido Metro |

| 19th | 0.569 | Modernization of interchange systems with “CFMU” Bruxelles for apron airside monitoring |

| 20th | 0.563 | Maximization of the use of eco-compatible materials and easily maintainable structures |

| 21st | 0.562 | New Energy saving interventions and alternative sources policies |

| 22nd | 0.561 | Modernization of access control system in operational areas (“RFID” technologies, biometric devices, “OMNICAST” video surveillance) |

| 23rd | 0.560 | New area set up for car sharing |

| 24th | 0.559 | Fiumicino North Terminal hi-tech routes and commercial area |

| 25th | 0.557 | Fiumicino Terminal North new waiting area for arrivals |

| 26th | 0.553 | Realization of a new flight information display system |

| 27th | 0.552 | Modernization of electronic payment systems for parking |

| 28th | 0.544 | Modernization of T3 plant networks for efficiency and energy saving |

| 29th | 0.536 | Infrastructure enhancement for fine dust reduction |

| 30th | 0.535 | Preparatory works for the infrastructural expansion |

| 31st | 0.532 | Use of colors for the perception of large and comfortable environment |

| 32nd | 0.526 | Expropriation activities for the expansion of the airport |

| 33rd | 0.525 | New integration among advertising spaces, address signs and dynamic information systems |

| 34th | 0.517 | Strengthening of first rain water disposal and purification structures |

| 35th | 0.508 |

Fiumicino North harmonization of the external and internal architectural lines (with extensive use of glass surfaces) |

| 36th | 0.507 | Drainage management of “Traiano” and “Focene” areas |

| 37th | 0.506 | T3 expansion of the arrivals and baggage reclaim area |

| 38th | 0.505 | T1 extension, boarding and adjacent aprons |

| 39th | 0.504 | Constructions of “temporary offices” for co-working activities |

| 40th | 0.502 | Realization of airside T1 hall in two commercial areas, retail, catering, services |

| 41st | 0.501 | New electrical network for runways (efficiency and energy saving) |

| 42nd | 0.499 | Fiumicino North new high capacity horizontal and vertical panoramic connections |

| 43rd | 0.491 | Development of intermodality and “network effect” systems |

| 44th | 0.481 | Installation of photovoltaic panels and wind generators for the production of electricity |

| 45th | 0.480 | New Terminal T4, boarding area “J” and new baggage handling system |

| 46th | 0.479 | Realization of boarding area “F” and T3 forepart (Dual Hub model) |

| 47th | 0.478 | New offices for airline companies, government agencies, and VIP lounges |

| 48th | 0.475 | Fiumicino North new “open” area food and beverage and mall type retail areas |

| 49th | 0.473 | Modernization of Terminal T3 (toilets, emergency exits) |

| 50th | 0.464 | Acceptance and information areas with homogeneous and modular fronts |

| 51st | 0.453 | Modernization of the commercial area of Terminal T3 |

| 52nd | 0.449 | New toilet facilities, nursery, first aid |

| 53rd | 0.445 | Discreet insertion of air conditioning and sound diffusion systems |

| 54th | 0.444 | Construction of gym and SPA |

| 55th | 0.441 | Modernization of management applications and software |

| 56th | 0.436 | Parking spaces in the east area connected to “GRTS people mover” |

| 57th | 0.434 | Realization of water intake from Tiber river for industrial uses |

| 58th | 0.427 | Graphene asphalt technology (first airport in the world) |

| 59th | 0.421 | “Business City” construction with “single tenant” offices area |

| 60th | 0.413 | Enlargement of car parks in the central area and construction of the “GRTS people mover” |

| 61st | 0.409 | Fiumicino North new “PR” parking (3130 sq m approx.) |

| 62nd | 0.407 | Increased protection for engine test area |

| 63rd | 0.400 | Upgrading of information systems for monitoring taxilane Yankee, Zulu, Victor, Whiskey, Mike, Tango |

| 64th | 0.381 | New multi-storey “F” parking in the central area |

| 65th | 0.380 | New buildings for institutions and professionals |

| 66th | 0.372 | “AZ” cargo reconversion for BHS/HBS (baggage handling system all over the airport) |

| 67th | 0.354 | Fourth runway, taxiway, perimeter, primary networks |

| 68th | 0.350 | Modernization of the new AdR main office building |

| 69th | 0.346 | Extension of aircraft parking aprons and airside logistics area |

| 70th | 0.345 | Extension of aprons in the cargo city area |

| 71st | 0.344 | Extension of aircraft parking stands in the “Pianabella” area |

| 72nd | 0.343 | Flight infrastructure works, “Seram” area (fuel distribution), new customs gate |

| 73rd | 0.342 | Extension of aprons in the “AZ” technical area and expansion of apron |

| 74th | 0.341 | Doubling of taxiway “Bravo” |

| 75th | 0.310 | Square extension in the “ex-poste” area |

By aggregating the individual investments in relation to their macro-areas of intervention, we have observed that most of the first priorities turned out are associated to the development of hi-tech and hi-skill smart solutions. It is conceivable that these results emerged because, on the one hand, these alternatives fully respond to a human-centric strategy guided by users, on the other hand, because of their high QH intensity registered (with most of the inclusive solutions simultaneously involving the industrial system, the university system, and that one of the civil society); finally, given their modest need for “hard” structural interventions, both feasibility and profitability get to be more governable, as well as tied to shorter payback periods. The second most valuable group of priorities concerns those interventions related to the environmental sustainability. This macro-area includes not only those interventions purely aimed at respecting and enhancing the environmental context (the fifth propeller) but also those one that allow the SA to implement energy saving and environmental footprint reduction policies, which can even constitute a direct or indirect economic advantage. The third group of priorities refers to urban activities. This macro-area has a high ecosystem intensity, since it involves, among others, (1) many players in the rail and road transport industries (for passenger and commercial use); (2) local, regional, and national institutions; and (3) improves urban mobility between SA and the surrounding environment. The fourth and fifth sets of priorities concern respectively interventions on the terminals and landside infrastructure works. In these cases, the weight of the structural interventions is manifested by more challenging feasibility constraints; therefore, among the possible decision-making logics, it seems plausible to concentrate more the organization's resources at a later time, while respecting anyway the priorities indicated by a human-centric participatory development process. Finally, the least priority macro-categories are those relating to the interventions on parking areas and to airside infrastructure works. But if investments in parking lots seemed not to be perceived by respondents as particularly valuable, the situation is different for the airside investments (e.g., fuel distribution areas, aprons, runways, taxiways): these issues, which could range between mere security interventions (already probably excluded in our simulation) and expansion of the SA’s fleet capacity, are liable to be excluded a priori from a participatory dynamic. In these hypothetical cases, the SA could deem it appropriate to identify, from time to time, what are those urgent improvements without which it could not guarantee the correct provision of its services. From this point of view, another compromise solution for a complex organization could be to use this model to partially integrate its prioritization and decision-making processes, trying to preserve as much as possible a human-centric vision through an adequate circulation of knowledge, inside and outside its own boundaries.

Conclusions

The survey we have performed has confirmed that, for some aspects and some users, a human-centric innovation path could even disregard the technological dimension (which should be the more innovative dimension par excellence) while pertaining the infrastructural one or the environmental one, or even the (eco)systemic one, as a wider perspective. Conversely, the positive impact of I5.0 innovation strategies has seemed to be not relevant for about 10% of users, i.e., those outer-directed users that did not express clearly their expectations and needs. In these cases, a technology-push strategy, or in any case a self-referential decision-making process, could still meet their approval. But this does not diminish the importance for complex organizations in smart environments to align their policies towards a human-centric perspective, given today’s relevance of a systemic vision in all business environments, especially those relating to smart solutions (Elliot & Radford, 2015; Beverungen et al., 2019).

With regard to the prioritization process, the configuration obtained by using the proposed model has greater possibilities of meeting users’ expectations; moreover, the ecosystem would benefit from greater spillover effects deriving from a synergistic boost to innovation. Furthermore, even if it is not possible to adopt the model as a unique methodology for the identification of a decision-making strategy, its usefulness will remain intact, since it will guide decision makers towards a reliable compromise solution that would still be win–win. In addition, both the ex-ante and in-itinere time dimensions are more suitable in pursuing objectives that are based on the measurement of stakeholder feedback and insights. From this perspective, the knowledge and data previously possessed, in providing some sort of “just in time” innovations, prevents the organization from having to retrace its steps to recalibrate the production processes (although ideally, it would be appropriate for slight adjustments to be made through the periodic release of new knowledge, reiterating all the phases of the model).

A research limitation concerns the partially simulated estimate and assignment of weights to the selected MCDA prioritization criteria; however, this necessary simulation is based on the assumption of reasonable judgment yardsticks (as really happens to decision makers when trying to manage uncertainty and complexity), resulting from rigorous content analysis. Anyway, by adapting the model to the specific prerogatives of certain organizations, we state that such a user-driven and QH ecosystem innovation approach can promote fine-tuning dynamics and allow a better resource allocation in innovation strategies and investments, going beyond a too self-referential dimension. In addition, taking into account the difference among large, medium, and small airports (as well as large, medium, and small-sized organizations), we can state that the less developed contexts (referring either to smart environments or entire territories) could not be sufficiently able to exploit the potential possibilities of knowledge circulation. The implementation of strategies for I5.0 often depends on a series of factors for whom sharing is necessary, such as any territorial support in growth policies. Institutions, entrepreneurs, and managers should take into consideration these differences and plan interventions reflecting the real conditions of their contexts.

On the basis of our analyses and the literature review, considering possible implications for policy, practice, and research, we think that our results can be useful for a series of contexts (both in research and in organizations) characterized by complex systemic dimensions. Institutions could intervene with their support in a more targeted way, being able to evaluate more accurately which solutions offer greater added value to the ecosystem; the organizations practitioners could base their decisions on the exploitation of the knowledge possessed and on the spill-over effects that are expected, activating virtuous dynamics able to improve the prioritization processes and the respective time-oriented strategic scheduling, while academics can start from the proposed model to introduce new open innovation theoretical advances as well as practical assessment metrics (Birchall et al., 2011; Cruz-Cázares et al., 2013; Edison et al., 2013; Hoelscher & Schubert, 2015).

In light of the above, we can state that the optimal management of smart environments like the airport one should be extended to a large number of dimensions, regarding inside, outside, and beyond the physical and visible structure (but even beyond technology, which cannot constitute the exclusive dimension of the nowadays innovation processes) focusing on a people-culture-technology dynamic and system-centric perspective (Carayannis & Alexander, 2006). This complex sharing and circulation of knowledge regards people and the surrounding environment. We are dealing with the same actors that allow the creation and the joint development of human capital, social capital, territorial capital, economic capital, legal/political capital, and natural capital, in order to constitute a quintuple helix that pushes an industry towards new (5.0) innovative routes. Precisely because the actors involved in these decision-making and development processes are multiple, the main challenges regard the ability to coordinate and make the innovation strategies converge towards a widely shared goal. Therefore, continuous dialogue must take place by means of a round table open to several participants, as many as the representatives of the various parties involved. In this way, the process of smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth will affect the entire ecosystem and will accrue benefits shared by all stakeholders, from the subjects merely closest to the business to the community (communities) itself and its environment at large.

Future research should aim to fill the gap in insights for open and ecosystem innovation models extended to wider territorial contexts (Stadler et al., 2013; Dattée et al., 2018; Tsujimoto et al., 2018; Walrave et al., 2018; Dziallas & Blind, 2019). In this case, the airport industry, with its high rate of technology and its substantial opportunities for multi-stakeholder involvement, can represent the cross-roads for a new way of doing business focused on the ability to network, to design in harmony, to share knowledge and technological assets, and to foster smart, sustainable, and inclusive solutions.

Footnotes

Press release. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB, 2020. Sun. 17 May 2020. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1975/press-release/.

The CIS is a survey created by the European Union (Eurostat) and executed by national institutions based on the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No. 995/2012 of October 26, 2012 (OECD, 2005; Eurostat, 2015). This questionnaire-based method discusses the technical features and the economic significance of a company’s innovative product (Cricelli et al., 2016).

Despite, because of Covid-19, an estimated $434 billion loss is expected in 2020, with 7.5 million canceled flights from January to July 2020 (IATA, 2020).

Only those airports with over 25 million passengers have been taken into consideration for the awards.

(Both ACI and SkyTrax are the main world institutions of quality certification for airport’s services.) Also, these institutions use a survey made in a completely independent way, through specific market researches carried on a global level on products and services that contribute to the traveller overall experience.

From August 24, 2018 to January 5, 2019 and from September 21, 2019 to February 11, 2020.

ENAC is the Italian “national body for civil aviation.” It is the Italian authority for technical regulation, certification, and surveillance in the civil aviation sector subject to control by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport. It is a non-economic public body with regulatory, organizational, administrative, patrimonial, accounting, and financial autonomies.

The document in question has been updated two times, in 2016 and 2019. It envisages the realization of works until 2021, and the planning of interventions until 2044, namely the year in which the public concession to AdR expires.

It concerns all those technological interventions and transversal initiatives aimed at implementing particularly innovative and experimental solutions (new hi-tech security protocols, special partnerships with universities, new digital 4.0 solutions, etc.).

It concerns all those technological interventions and transversal initiatives aimed at implementing particularly innovative and experimental solutions (new hi-tech security protocols, special partnerships with universities, new digital 4.0 solutions, etc.).

Specifically, the weights assigned have been deduced from the following relative comparison between pairwise:

• QH intensity is (1) very moderately not preferred to desirability (QH < 2 D), (2) very moderately preferred to feasibility (QH > 2 F), (3) little moderately preferred to profitability (QH > 4 P);

• Desirability is (1) very moderately preferred to feasibility (D > 2 F), (2) strongly preferred to profitability (D > 5 P);

• Feasibility is strongly preferred to profitability (F > 5 P).

Inspired by the partition created by a GVR report (2019), the four macro-categories have been created as follows:

• Basic services (all the services directly connected to the basic travel experience: items smart booking/ payment/check-in, fast boarding, guaranteed secure environment, good airport’s hospitality services, faster boarding, airport security, modernization and extension of infrastructure endowments);

• Outside services (all the extra services related to the outside networked area, in a system-based dimension: items car rent, effective connection between the airport and the city, good parking services, pollution abatement and sustainable energy, physical connection with the city, connection with the city events, connection with the city business);

• Extra services (all the supplementary comfort services within the airport: items good airport’s restaurant services, good airport’s entertainment services, stores and retail services, luggage storage, passenger specific retail and hospitality services, overall airport entertainment);

• Hi-tech services (all the services related to IoT, digital and hi-tech solutions: items connection with the city events, real-time information services, digital Apps with interactive contents, luggage traceability, beacon/location-based technologies, virtual mapping services, way-finding and real-time notifications, virtual-personal assistance).

Since 77.9% of the interviewed users did not come from Italy, even by isolating the sample of Italian passengers the result did not undergo significant deviations.

Rogers theorized an adoption curve of the innovation, which describes the distribution of innovation in time considering the users’ attitudes, behaviors, and purchasing choices. According to this typology, the consumer universe was composed of (1) innovators (2%), (2) early adopters (14%), (3) early majority (34%), (4) late majority (34%), and (5) laggards (16%).

The consistency index (CI) measures the degrees of inconsistency in the pairwise comparisons. Considering the transitive property that lies among the different comparisons, a reliable CI resulting from any human evaluation must not exceed 0.10 (10% inconsistency) (Saaty, 1980, 1988, 1990; Larichev and Olson, 2001; Siraj et al., 2015).

Highlights

• Participatory dynamics in complex smart environments can systematically include knowledge from the ecosystem.

• Stimulate spillover effects through the total overcoming of self-referential firm strategies

• An Industry 5.0, human-centric perspective is pursuable through the QH synergistic view.

• Systematically intervene in innovation decision-making processes through a new integrated model

• The process of prioritizing innovation policies in smart airports (empirical evidence)

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- ACI (2018). ASQ Awards. Recognizing the world's best airports in customer experience. (https://aci.aero/customer-experience-asq/asq-awards/).

- Adams, R., Bessant, J., & Phelps, R. (2006). Innovation management measurement: A review. International Journal of Management Review,8(1), 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- AdR, (2019). Aeroporti di Roma: in 2018 nearly 49 million passengers passed through the capital’s airports historic record helped by strong long-haul growth. https://www.adr.it/web/aeroporti-di-roma-en

- AdR-ENAC, (2011). Contratto di programma ENAC-AdR. Sistema aeroportuale romano. Strategie di sviluppo. (http://www.mit.gov.it/mit/mop_all.php?p_id=13851).

- AdR-ENAC, (2016). Stato di attuazione degli investimenti aeroportuali in Italia. Contratti di programma. Report 2016. (https://www.enac.gov.it/pubblicazioni/report-12016-stato-di-attuazione-investimenti-aeroportuali-in-italia-contratti-di-programma).

- AdR-ENAC, (2019). Aggiornamento tariffario 2020. Stato di avanzamento degli investimenti. (https://www.adr.it/documents/10157/17305857/6_ITA_Stato+di+avanzamento+degli+investimenti.pdf/9b530f9c-d008–4a73-aab0-d364fed8f0da).

- Andrew J.P., Manget J., Michael D.C., Taylor A., Zablit H. (2010). Innovation 2010: A return to prominence and the emergence of a new world order, The Boston Consulting Group, 1–29.

- Andrew, P. A., Haanaes, K., Michael, D. C., Sirkin, H. L., & Taylor, A. (2008). A BCG senior management survey - Measuring innovation 2008 - Squandered opportunities. Boston: The Boston Consulting Group. [Google Scholar]

- Arnkil, R., Järvensivu, A., Koski, P., & Piirainen, T. (2010). Exploring quadruple helix outlining user-oriented innovation models. Institute for Social Research, Work Research Centre: University of Tampere. [Google Scholar]

- Bange C., Marr B., Bange A. (2009). Performance management: Current challenges and future directions, Business Application Research Center, 1–24.

- Becheikh, N., Landry, R., & Amara, N. (2006). Lessons from innovation empirical studies in the manufacturing sector: A systematic review of the literature from 1993–2003. Technovation,26(5–6), 644–664. [Google Scholar]

- Bekuna, F. V., Alola, A. A., & Sarkodie, S. A. (2019). Toward a sustainable environment: Nexus between CO2 emissions, resource rent, renewable and nonrenewable energy in 16-EU countries. Science of the total Environment,657, 1023–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenzon, S., & Schankerman, M. (2009). University knowledge transfer: Private ownership, incentives, and local development objectives. The Journal of Law and Economics,52, 111–144. [Google Scholar]

- Beverungen, D., Müller, O., Matzner, M., Mendling, J., & vom Brocke, J. (2019). Conceptualizing Smart Service Systems. Electronic Markets,29, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Birchall, D., Chanaron, J. J., Tovstiga, G., & Hillenbrand, C. (2011). Innovation performance measurement: Current practices, issues and management challenges. International Journal of Technology Management,56(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Blok V., Lemmens P. (2015). The emerging concept of responsible innovation. Three reasons why it is questionable and calls for a radical transformation of the concept of innovation, in B. J. Koops I., Oosterlaken H., Romijn T., Swierstra J. van den Hoven (Eds.), Responsible innovation 2: Concepts, approaches, and applications (19-35).

- Boemelburg R., Jansen J.J.P., Palmié M., Gassmann O. (2019). Opening up the black box: A contingent dual-process model of ambidexterity emergence, 1. 10.5465/AMBPP.2019.203

- Borrás, S., & Edquist, C. (2013). The choice of innovation policy instruments. Technological Forecasting and Social Change,80(8), 1513–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, W., & Uebernickel, F. (Eds.). (2016). Design thinking for innovation: Research and practice. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, W. M., Dar-Brodeur, A., & Tweedle, J. (2020). Firm networks, borders, and regional economic integration. Journal of Regional Science,60(2), 374–395. [Google Scholar]

- Burgelman, R. A., Wheelwright, S. C., & Christensen, C. M. (2002). Strategic management of technology and innovation. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, N. D., Roehrich, J. K., & Davies, A. C. (2009). Procuring complex performance in construction: London Heathrow Terminal 5 and a private finance initiative hospital. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management,15(3), 178–186. [Google Scholar]

- Campanella, F., Della Peruta, M. R., Bresciani, S., & Dezi, L. (2017). Quadruple helix and firms’ performance: An empirical verification in Europe. The Journal of Technology Transfer,42(2), 267–284. 10.1007/s10961-016-9500-9. [Google Scholar]

- Carayannis, E.G. et al (2021). Known unknowns in the era of technological and viral disruptions: Implications for theory, Policy and Practice, forthcoming.

- Carayannis, E. G., & Alexander, J. (2006). Global and local knowledge glocal transatlantic public-private partnerships for research and technological development. New York: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Carayannis, E.G., Barth, T.D., Campbell D.F.J. (2012). The quintuple helix innovation model: Global warming as a challenge and driver for innovation, Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Aug. 2012, 1–12. 10.1186/2192-5372-1-2.

- Carayannis, E. G., & Campbell, D. F. J. (2009). ‘Mode 3’ and ‘Quadruple Helix’: Toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. International journal of technology management,46(3–4), 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Carayannis, E.G., Campbell, D.F.J. (2010). Triple helix, quadruple helix and quintuple helix and how do knowledge, innovation and the environment relate to each other?: A proposed framework for a trans-disciplinary analysis of sustainable development and social ecology, International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development (IJSESD), 1, 1, 41–69. 10.4018/jsesd.2010010105.