Abstract

Approximately 34% of all Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage (MA) plan in 2019. Quantitative evidence suggests that MA beneficiaries have low rates of switching plans, but that beneficiaries who are hospitalized or use postacute nursing home care are disproportionately more likely to exit their plan. This research sought to explore how MA enrollees choose plans and the factors involved in their decision to keep their current plan or switch plans. We conducted 25 semistructured interviews focusing on expectations and experiences preenrollment and postenrollment among MA beneficiaries. Overall, the beneficiaries interviewed reported being highly satisfied with their plans. After selecting a plan, there was little incentive to revisit their choice since they viewed their plan as “good enough.” Confusion, health status, cost and benefits also contributed to many seniors keeping or switching their plans. These seniors were reluctant to switch plans unless they experienced a major health event.

Keywords: Medicare Advantage, Medicare open enrollment, insurance switching, insurance stickiness, insurance plan choice, Medicare plan compare, Medicare star ratings

Introduction

Over 22 million Medicare beneficiaries, representing 34% of all beneficiaries, were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage (MA) plan in 2019 (Jacobson et al., 2019). With the recent efforts by the federal government to encourage expansion of benefit structures, plan designs and plan availability, enrollment in MA is expected to increase (The White House, 2019). Racial/ethnic minority populations with low incomes are more likely to enter MA, often because MA plans provide more generous or additional benefits (e.g., gym membership, eyeglasses) than traditional Medicare without an increased premium beyond that of Part B (Weinick et al., 2014). Since 2003, MA has incorporated several changes, including locking enrollees to their choice of plan for a year (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016a). Most MA beneficiaries without concurrent Medicaid enrollment can only make changes to their coverage yearly during the open enrollment period (October through December). Every beneficiary has an opportunity to assess their current plan and compare it to other options available to them. Beneficiaries can then select a plan that best aligns with their preferences for lower costs, coverage of services, access to providers, and improved quality (Berki & Ashcraft, 1980). If beneficiaries have changes to their financial status or health needs or MA plans alter their benefits, networks, premiums or cost-sharing, these changes should cause some beneficiaries to switch MA plans. Yet quantitative research has shown strong evidence of status quo bias with about 80% of people remaining in the same plan (Jacobson et al., 2015).

Conceptual Framework

Traditional economic models of insurance choice suggest that consumers are expected to consider personal characteristics (health risks, finances, future health problems, etc.) and plan features (quality, out-of-pocket costs, premiums, benefits, network, etc.) when selecting a plan (Rice, 2013). Subsequent changes in the factors that influenced the original choice will cause some consumers to switch plans.

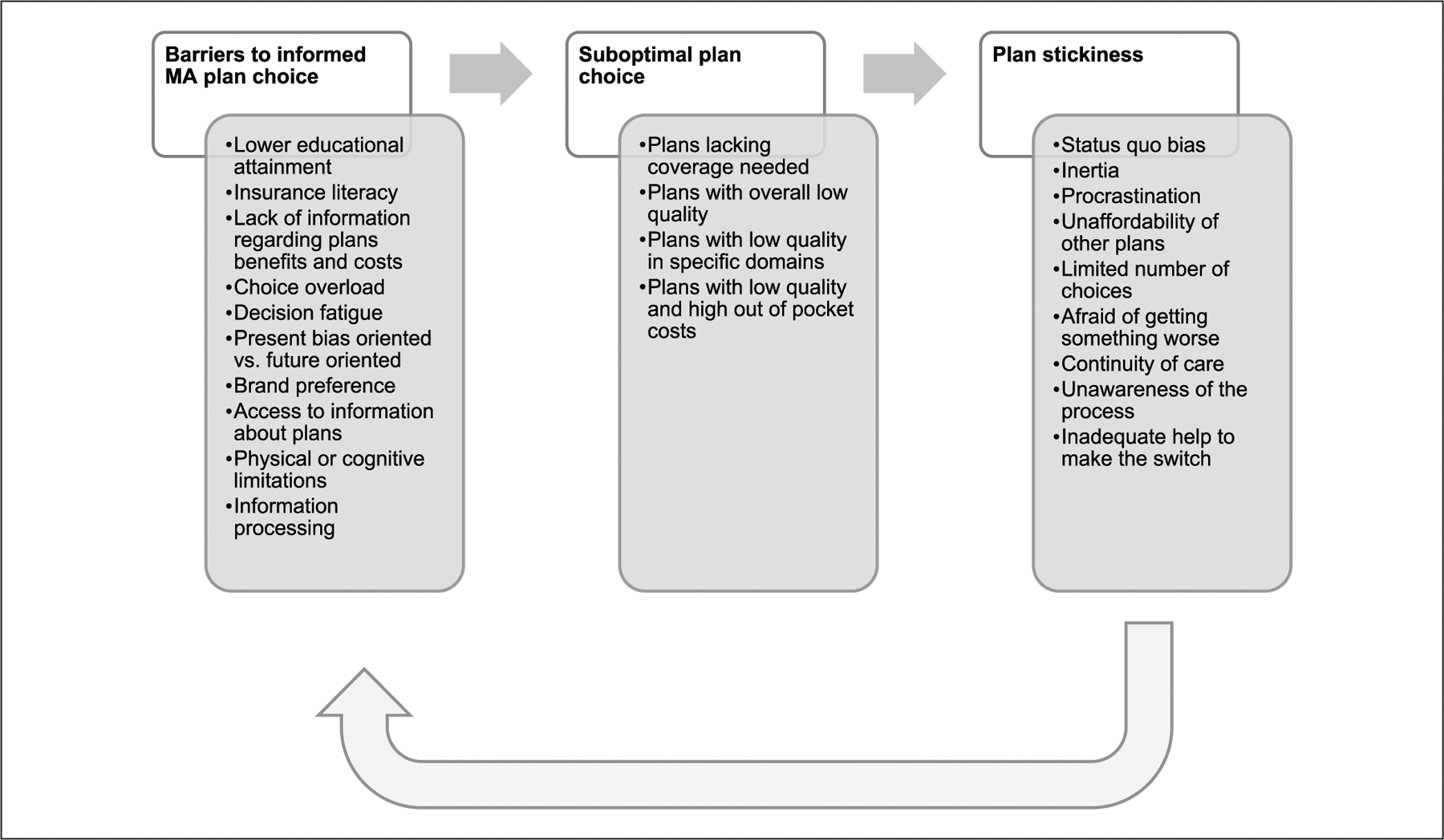

Alternative theories on consumer decision making emphasize the difficulty of switching, particularly with a large choice set (see Figure 1). As shown by the vast evidence from the Medicare Part D literature, choosing plans is a complex task (Abaluck & Gruber, 2011; Heiss et al., 2013; Hoadley et al., 2013; Marzilli Ericson, 2014; Zhou & Zhang, 2012). Seniors have little incentive to revisit their choices once they enroll into a plan that provides some adequate level of satisfaction (Stults et al., 2018). Making these decisions requires complex cognitive processes and being able to weigh trade-offs between the coverage, cost, and quality of available plans (Han & Urmie, 2018). People often consider premiums as an important aspect when choosing a plan (Abaluck & Gruber, 2011; Cline et al., 2010). But many consumers appear to have difficulty identifying the full cost of health care and total out-of-pocket costs associated with copays and other services (Layug & Carter, 2014). Considering that MA beneficiaries often have less advanced education than those in traditional Medicare (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016b), this information may be more difficult to process and lead beneficiaries to enroll in suboptimal plans and stick to these choices even when a better alternative is available (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Medicare Advantage (MA) plan choice and stickiness.

For example, Zhou and Zhang (2012) found that only 5% of Part D beneficiaries chose the cheapest plan given their medication needs. Most people spent $368 more annually than they would have spent had they selected the cheapest plan available in their region based on their medication needs. Furthermore, 22% of beneficiaries could have saved about $500 annually by switching plans, but they tend to stick with their initially chosen plan. In addition, Abaluck and Gruber (2013) found that only 20% of beneficiaries selected Part D plans that minimized their out-of-pocket costs, and their choice persisted over time (Abaluck & Gruber, 2013). For example, in 2006, Humana had the lowest premium in the market for two of their plans, resulting in two of the highest enrollment among all Part D plans (Hoadley et al., 2006). Despite Humana increasing premiums in the following years, it was able to maintain the same market share around the same time (Hoadley et al., 2012).

New Contributions

Based on the results from the quantitative literature, MA beneficiaries appear to act similarly with a preference for the default option and inertia to switch their current plan (Jacobson et al., 2015; Jacobson et al., 2016). Potential explanations have been proposed about plan stickiness among MA beneficiaries (Jacobson et al., 2015; Meyers et al., 2019; Neuman & Jacobson, 2018); however, these have been based on other insurance markets and beneficiaries from different insurance plans. Little is known about how MA enrollees make these decisions using information collected from the beneficiaries themselves, as there is only one study that has included MA beneficiaries when looking at how seniors make insurance choices (Jacobson et al., 2014). Yet no study has focused exclusively on the MA population.

Filling this gap of knowledge is important because MA provides coverage to one third of Medicare beneficiaries, and it is a preferred choice of coverage for low-income and racial/ethnic minority groups (Jacobson et al., 2019), who tend to have lower levels of educational attainment and income. Approximately 40% of MA beneficiaries have incomes of less than $20,000, and 45% of Hispanics and 29% of African Americans in the Medicare program enrolled in a MA plan in 2016 (Jacobson et al., 2015). This may be related to insurance literacy and the ability to make appropriate choices. Selecting a health insurance plan is a complex task and requires considering out-of-pocket costs, benefits and quality of plan. Consumers may understand premiums and copays as these are fixed costs, but they may have problems calculating the full extent of cost-sharing (coinsurance and deductibles; Robertson, 2019). Finally, MA beneficiaries may not be aware of plan quality or where to obtain this information.

Furthermore, choosing an MA plan is different from Part D since beneficiaries have to consider different benefit packages for a number of services. For instance, MA beneficiaries need to look at premiums, deductibles, copays/coinsurance, pharmacies and prescription drugs, provider network, benefits (e.g., preventive, acute, postacute), additional benefits (e.g., vision, dental, hearing, transportation, fitness, over-the-counter drugs, worldwide emergency, telehealth, in-home support, home safety devices & modifications, emergency response), and the overall quality of the plans or specific domains (see Medicare Plan Compare). Making an appropriate decision requires understanding this information.

In this investigation, we aimed to (a) explore how MA enrollees make their choices and (b) to describe what factors are involved in the decision to keep their current plan or switch plans. We accomplished this through qualitative interviews with MA beneficiaries.

Method

Design and Sample

We conducted 25 semistructured in-depth interviews with seniors from Rhode Island both in person and over the phone from April 2018 to March 2019. One interview included a married couple that wanted to be interviewed together. Therefore, a total of 26 participants were included in the study. Seven interviews were conducted over the phone and 18 were in-person. Participants were recruited and enrolled through purposive and snowball sampling from local senior, community, and health centers, aiming for variation in age, race/ethnicity, and education level. We sent flyers via e-mail and/or in-person to these different sites, which then posted or handed the flyers to participants. Participants were encouraged to contact the primary investigator if they were 65 years or older, were enrolled in a MA Insurance Plan, and would like to participate, or wanted to receive more information about participating. The interview guide (see the appendix Table A1, available in the online supplemental material) was developed from a literature review as well as the hypothesis of the quantitative aim. Prior to the interview, the study was explained to potential participants and informed consent was obtained. Participants received a $25 gift card to a local drug store or grocery store for their participation.

Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes and were performed by one or two members of the research team, and audio recorded with participants’ consent. Interview questions focused on the factors they weighed in their initial selection of their current plan (costs, star ratings, providers, familiarity with insurance), expectations and experiences with the current plan, and specific strategies to enhance optimal plan selection. Participants also provided basic socio-demographic information about themselves (age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, etc.). We proposed to conduct a minimum of 20 interviews. After these interviews, we did a preliminary review of the data and determined that we needed to hear more about providers and networks, changes to existing plan, and sources of information; subsequently, we conducted five more interviews. By the time we stopped (25 interviews with 26 participants), we had reached data saturation, meaning that we were not hearing anything new on any of our key themes (Curry & Nunez-Smith, 2015; Fusch & Ness, 2015).

The research protocol and project materials were approved by the Brown University institutional review board.

Analysis

All interviews were transcribed and entered into the software NVIVO. Interviews were coded line by line using a combination of a priori and emergent codes (Padgett, 2012; Weston et al., 2001). Common in the health services research literature (Gadbois et al., 2019; Shield et al., 2019), a priori codes were developed from a literature review, research proposal and the interview protocol. When the data suggested a new theme to be added, inductive thematic analysis was used to develop emergent codes. The resulting coding scheme reflected areas of interest from the interview guide as well as unanticipated findings from interviews (see the appendix Table A2, available in the online supplemental material). Initially, authors one and two read and coded three interviews independently using this framework and then compared their results. The two authors discussed and refined codes, talked about preliminary patterns in the data, and discussed differences and alternative interpretations until a consensus was reached. Author two coded the remaining transcripts, discussing new and emerging themes with author one when needed. Data analysis was aided by these discussions as well as periodic presentation of data. An audit trail was kept throughout the analysis using memos, research meeting notes and description of codes and emerging themes (Crabtree & Miller, 1999).

Results

There were 26 participants ranged in age from 65 to 90 years (mean age = 74 years), 70% were female and with diverse backgrounds: 14 were White, 8 were Hispanic, 3 were African American and 1 was Asian. Education levels ranged from less than elementary school to Master’s level; 19 participants had “lower education level,” meaning high school degree or less, and 7 had “higher education level,” meaning completion of an undergraduate or post graduate degree. Although most participants did not recently switch or were not currently considering switching to a different plan, 10 women and 3 men (the majority of them White) have switched plans before. Five major interconnected themes emerged regarding plan switching and stickiness: (a) confusion about the Medicare program and insurance terms; (b) insurance benefits (premiums, copays, costs); (c) provider networks and referrals; (d) health status; and (e) overall satisfaction with current plans.

Seniors Reported Confusion With the Medicare Program and Insurance Terms, Which Deters Them From Comparing Plans

Over half of the participants (15) reported confusion about the Medicare program and/or insurance terms—This was somewhat consistent across sex and education levels, but it was more prevalent among minorities. Overall, this source of confusion appears to not only influence initial insurance choice, but it may also prevent some seniors from switching and/or effectively comparing plans. For instance, one senior mentioned,

I get Medicare, Medicaid mixed up, for one thing. Uh, uh, you know what’s a copay and deductible. It’s just—it’s more confusing than what it has to be … I’m [in my late 70s] but when I retired I was like 65 and I’m thinking what about if somebody now, if somebody my age trying, wants to understand that process, it just doesn’t come about. That’s why you see a lot of people go to—now you got Medicaid, Medicare and then you got Medicare A, which everybody gets. Now it’s B. Now what’s covered under B? Now then you got, what is it, the uh, part that covers medicine

(male, African American, mid 70s, high education level).

When asked if they have compared other plans, one senior said “No. It only confuses me and I don’t want to be confused because I’m all set right now” (female, Asian, late 60s, high education level). Another senior explained that she found the process confusing “Because I talk to others with other plans and some, it depends upon your needs, and my needs are so simple it didn’t seem important to go through all of that because this worked fine for me” (female, White, early 80s, low education level). Later she described, “Most of us don’t really understand all there is to know about deductibles, except you have an exception here and you have exception there. There’s just too many, it’s like lawyer speak.”

Even among seniors who felt comfortable with the insurance terms, they agreed that they might be confusing for seniors. When prompted, one senior described how her discussions with peers suggest how “They feel comfortable and so it’s like, ‘let’s not rock the boat, I’m not dealing with this.’ It’s too complicated … Make people crazy” (female, White, late 60s, high education level). Even one of these seniors that compared plans mentioned,

I was goin’ back for quite some time just trying to see who cuts, who covers what, or who doesn’t cover what, what the, uh, copay is, you know, what’s … it was just so confusing. They didn’t make it easy I tried to like put down my paper, compare on a spreadsheet showing what was covered by who and what wasn’t covered—just so confusing

(male, African American, mid 70s, high education level).

Another senior added “Yeah, [it] could be [confusing]. They want you to think of it. You have to, you have to figure out the cost of this, the cost of that” (female, White, late 70s, low education level).

Finally, one senior described his peers’ experiences with having multiple choices “I realize for a lot of people having a lot of choices just makes it more complicated for them” (male, White, early 70s, high education level). Another senior stated her own confusion was due to choice overload,

You think because there’s so many plans that it’s so complicated, it’s not like there’s three plans and anybody can just look at them and go, “Okay, this is the right one for me.” There’s like 13 plans or something, it’s crazy … [one company] is like a half a dozen and [these other company] got three or four, Medicare’s got some, and some are HMOs and some are not and … Yeah, it’s very complicated

(female, White, late 60s, high education level).

Seniors Discussed Premiums, Copays or a Global Notion of Costs

Nearly all seniors, 24 participants, discussed how cost influenced and was one of the most important consideration in their decision to keep or switch their plans. When seniors described costs more specifically, they focused on monthly premiums (15 participants) and copays (12 participants). One participant described how cost influenced her decision making,

I did not want a plan that had a high deductible, which are always cheaper but I don’t have that kind of money. I don’t have $5,000 in the bank to pay my bills. If it’s $15, I’ll pay the $15

(female, Hispanic, early 70s, low education level).

When talking about her current plan, one senior explained,

I’m happy with it. I’ve had it now for years and I’ve had no problem with it. The only thing is the price goes up. Every year, the price goes up. But this is part of life … I adjust to that. I have no other choice. You pay it, right?

(female, White, late 70s, low education level)

For others, the small savings of switching was not worth the hassle, “I was pretty satisfied that there wasn’t anything that could substitute for what I was taking. Maybe there will be in the future, I don’t know. I mean is it worth it for $4 less?” (male, White, early 80s, high education level). Many seniors described that they were sticking to their plan because it seemed affordable to them. Yet a few seniors mentioned that they wished they could afford a better plan. As one senior said (female, White, early 80s, low education level), “There’s the real expensive plan, which I wish I could have but can’t.” When asked to elaborate, she explained that she could “Do without copays” and that “Prescriptions could be cheaper.” Later in the interview she reiterates, “I’d rather pay it every month so that when something does come up, I don’t have to worry about it.”

One senior explained he has a more expensive plan as a piece of mind “I mean it’s truly piece of mind to tell you the truth. You don’t have to worry about … You just don’t have to worry about that now” (male, White, early 80s, high education level). Another senior recognizes this line of thinking in his peers, relating it to broader themes of financial and insurance literacy, future planning, and guarding against hypotheticals that emerged from the interviews:

[Seniors] overcompensate. People are not using insurance like they should. Insurance should be for things that you can’t afford, you know catastrophic not day to day, right? … A lot of people will just get the most coverage they can, they can afford

(male, White, early 70s, high education level).

Another senior confirmed this mentality explaining,

I have a friend who’s paying $600 a month for her supplements, and so anytime something comes up she knows it’s going to be covered, “Okay, I’ll have this MRI and I’ll have this test.” She doesn’t think about anything of whether she should do it or not do it, does she need it, it’s paid for

(female, White, late 60s, high education level).

Cost was also an important reason why seniors did switch plans. Three seniors talked about the so-called “zero premium” plans. As one participant explained, “Actually, it was because of a monetary thing. What I have right now … I think one time I was paying like 165 dollars a month for mine.” She goes on to explain that a new zero premium plan became available, so she switched. Interestingly, this senior explains how the cost changed over time, “And then it [increased] to 17 or and then now it’s 23” (female, White, mid 70s, low education level). Another senior related changing personal finances to their decision to switch to a lower cost plan, also a zero premium,

Well when I retired, you know there wasn’t any money coming in like there used to be. So, I wanted, I didn’t even know about the zero plan and then uh, like, you know, my friends told me about it. So, then I decided to switch

(female, White, mid 70s, low education level).

Seniors Reported the Importance of Provider Networks and Referrals

Not surprisingly, the importance of providers emerged in various ways. This theme was present for 23 out of the 26 participants. Provider networks and referrals affected some seniors’ selection and switching of plans. In fact, some seniors described that any changes to provider network was often an impetus for switching plans. As one senior explained, “Yeah, some of my doctors weren’t on the [new plan] the following year after I joined. They weren’t on, and I had to go back to [old plan] because I’m not changing those doctors” (female, White, early 70s, low education level). Another senior mentioned that she looked at other plans but decided to stay on her plan because of choice of providers and hospitals as she stated, “Because there are only certain doctors that are in that program. And I don’t wanna leave the doctors I have … I’ve known [them] for like 100 years” (female, White, early 80s, low education level). When asked if keeping her providers was important to her, she responded “Absolutely.” Another senior described a similar issue about how her providers were not covered when she switched to a different company,

Three of my doctors weren’t on it, so I couldn’t stay with them because I wasn’t gonna start changing all my doctors. And that was three doctors, that wasn’t just one, that was three doctors. And two of them, especially my gastroenterologist, I’ve been seeing him for like almost 20 years. I liked him and I don’t want to change

(female, White, early 70s, low education level).

Similarly, another senior stated that before she switched plans, she called her provider “To make sure she took [MA plan]” (female, White, mid 60s, low education level). However, this worry was not universal among our participants, some seniors (5) were not concerned about changing provider networks.

The process for referral to specialists also surfaced. Like provider networks, changes of referral processes mattered to some seniors (11) more than others. For some, when their MA plan changed to start requiring seniors switched when their plan started requiring referrals for specialists. “That is why I changed in 2015, because of the referrals that you need. Evidently, [Insurance Company 1] is more conscious about that. [Insurance Company 2] is about the care, you can go to any specialists that you want” (male, White, early 90s, high education level). Others maintained that this was a small, minor inconvenience. Finally, for some seniors, physician opinion was reason enough to switch plans. This is highlighted by one senior’s experience, “[My doctor] said, but [other company] will not pay for those x-rays. That’s when I made the decision [to switch]… . Once I got [new company] and I went back to the orthopedic man, because I was having a little bit of a problem, he was thrilled. He said, ‘Oh, I’m so glad you did this’” (female, White, early 80s, low education level). Ensuring that the providers were happy and/or treated fairly by the insurance company proved important to the participants we interviewed. One senior explains that delays in payments for her physicians prompted her to switch, “When you go to a new doctor, they’d say, ‘Oh, you’ve got [this plan from this insurance].’ Oh, yeah, I’d have to wait longer for my payments” (female, White, early 70s, low education level).

Seniors Reported That They Would Consider Switching Plans if Their Health Declined

Many seniors (19 participants) could not discuss their health plan without relating it to their health status; the two were intimately connected. This was discussed in a variety of ways across the spectrum of health status. Seniors who identified being very healthy—or “lucky” as many put it—were particularly resistant to switching plans, “Because I am very fortunate that I do not have bad health, I have excellent health, and this served my needs” (female, White, early 80s, low education level). Another senior expressed the same feelings by stating, “You know, I’ve had two hip replacements. I’ve had a hernia out. I have arthritis. I mean thank God, you know, I’m healthy … I don’t really need [more coverage]” (female, White, mid 80s, low education level).

The participants who identified as being relatively healthy did express some openness to switching plans in the future should their health status change as one senior stated, “No. No. I’m staying right here with these guys until something else happens, but nothing else is happening” (female, White, late 70s, low education level). Another echoed this sentiment,

But I’m not about to change. But if I was sickly I would consider maybe a better plan. But this plan is not bad, you know. I’m happy with it … I do many things. I’m very active … my mind is wonderful. I’m very sharp. You know? I say that to my son “How many people have Alzheimer’s or dementia when they get to be my age?”

(female, White, late 70s, low education level)

Finally, those who identified as having complex or multiple health needs often related their health status to their disinterest in switching. One participant described this process as,

I have seen some options, but I am comfortable with what I have. I know there are other options … [The insurance company] help[s] me with everything. I am very sick and they help me with my medications, doctors, therapy, and a lot of things. I suffer from anxiety, depression, and high blood pressure. I do not even know how I am able to walk

(female, Hispanic, mid 60s, low education level).

Another participant echoes this sentiment describing all her chronic conditions and discussing her MA plans as being the one she wanted and needed. She stated,

You know, I may die. I know I need lab work because I’m on coumadin and so forth and so on, you know I’m just happy with what I got … I have neuropathy in my feet because I’m diabetic. I have arthritis, arthritis bothers met. You know, sometimes it’s good. Sometimes it’s bad. You know, you just have to take your chances with it. You know

(female, White, early 80s, low education level).

Seniors Reported General Satisfaction With Current Plans

Overall, the majority of the participants (23) interviewed were extremely satisfied with their plans. Seniors did not directly discuss “quality” of plans unless they were prompted, and were generally unaware of Medicare Star Ratings for MA plans. When they were asked about Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Plan Compare tool, they just responded with a “What?” or “I went online. [But,] I didn’t go on Medicare.gov” (female, Hispanic, early 70s, low education level). When showed the list, the majority said that they had not seen that before. But when asked for their own rating, nearly every senior said they would rate their plan 4 or 5 out of 5 and expressed great satisfaction. As one senior responded, “Probably like four and a half, I would say. It’s pretty good … from what I hear other people, the way other people talk about their plans, I said maybe I don’t have it too badly” (male, African American, mid 70s, high education level); another senior mentioned “Oh, I’d give them five… . When I’ve had problems, they just responded immediately. I’ve never had to wait for anything” (male, White, late 60s, low education level). One senior said “A 5. I like everything, doctors, prescriptions. I have a lot of benefits” (female, Hispanic, early 70s, low education level). Another explains, “I don’t know, knock on wood I’ve been pretty happy” (female, White, late 70s, low education level). Seniors expressed how their satisfaction with their plans affected their disinterest with switching. “I’m the kind of person, when I get something that works, I stay with it” (male, White, late 60s, low education level). Another explains, “So I have a very simple plan, and it suits me. I’m fine with it. I’m not looking to go into a better plan because I’m okay with that” (female, White, late 70s, low education level).

The satisfaction does not just preclude seniors from making a switch, but from even comparing plans, as they felt that they were “all set.” Only eight participants (six women and two men, the majority of them White and with at least some high school level of education) mentioned that they read the material they receive from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services or different insurance companies, and/or attend the sessions offer by the local community centers and local libraries to actively compare rates and options every year during open enrollment. When asked if she ever compares plans, one beneficiary summed it up, “No, I no, I just stay with this. I don’t, I don’t compare … It’s good enough for me. I’m happy with it” (female, White, early 80s, low education level). Another participant answered similarly, “No. Why would I? … If I’m happy, why take a chance on being unhappy?” (male, White, late 60s, low education level). After they have made a choice, there was little incentive to revisit their options as this “good enough” sentiment deterred them from switching.

Discussion

These interviews with MA beneficiaries provided context regarding choices and underlying mechanisms behind those choices, specifically in terms of plan switching and stickiness among seniors based on their experiences. Seniors expressed general confusion regarding the Medicare program, and about specific components of MA. Over half of seniors struggled to understand the true health care costs—this was expressed among participants across all levels of educational attainment, with minority participants reporting more confusion. Many of the seniors interviewed in this study expressed sentiments consistent with the status quo bias phenomenon. As one said, “I ain’t changing none” (male, African American, late 60s, low education level). For many, stickiness was mostly about sticking with the status quo: “I don’t compare. I just stick with the same thing all the time. To me, it’s easier” (female, White, late 70s, low education level). Explaining how he chose the plan, one participant said “I just carried over because it was the same insurance coverage that I had before I retired” (male, African American, mid 70s, high education level). For others, the reasons for staying with their plan were more nuanced. Satisfaction, health status, costs, and providers all emerged as important themes informing seniors’ decisions to switch or stay with their plan.

Costs functioned as both sources of stickiness and reasons to switch. Discussions about comparing plans, switching plans, and reasons for keeping plans inevitably led to conversations related to costs and provider network. About half of the participants discussed their MA plan costs by focusing on their premiums, with a few participants highlighting that they would only enroll in lower/zero premium plans. Of note, half of MA plans nationally have no premium (Jacobson et al., 2019), which is similar in Rhode Island. Some participants went beyond discussing their premiums by describing other out-of-pocket costs such as copays to visit specialists. Seeing rising prices as an inescapable reality was not uncommon among participants. A few participants switched plans in the past, looking for a more affordable option, especially after the loss of a spouse, additional benefits and/or changes in provider networks. Once they made the switch, they have stuck with the plan for years. The idea of annually reevaluating plans based on their costs was not a priority for most seniors. In fact, only six participants mentioned that they read the material sent by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services or different insurance companies, and/or attended the sessions offered by the local community centers and local libraries to actively compare rates and options every year during open enrollment. There was a prevailing sentiment among some seniors that the more expensive plans are better. Respondents were willing or wished they could pay a higher premium for a “better plan” with more coverage in exchange to have a “peace of mind;” that—regardless of health status or current needs—more coverage is always better.

The connection between MA plan and health seemed almost inseparable, rendering it a source of stickiness itself. This showed to be true across the spectrum of self-identified health status. Some seniors resisted changing until their health status changed/declined. Often, these individuals identifying as healthy suggested an openness to switching plans should their health deteriorate. Those that were healthy felt their plan was good enough, because they did not need any additional benefits. Those who were sick were grateful to have a plan that met their health needs. Both groups expressed an unwillingness to switch plans because of their health. For these seniors with complex conditions, they had found a plan that worked for their needs and worried about the health and financial consequences of switching.

Ultimately, our results suggest these themes inform each other; why a senior sticks with one plan for many years is often due to a combination of these reinforcing factors. Satisfaction was a source of stickiness. The majority of seniors were relatively satisfied with their current plans and, for the most part, were reluctant to switch plans unless a major health event were to happen or changes in provider or benefits were needed. For these seniors, the thought of switching meant risking dissatisfaction.

Our findings are consistent with prior literature from the Part D and MA literature, and provides a unique context to quantitative studies. Research on MA has shown that most beneficiaries do not change plans regularly (Sinaiko et al., 2013). As suggested by others, initial plan choice may have long-term consequences (Basu, 2015). This appeared to be the case for most of our participants. However, if seniors were willing to compare, they may find more affordable plans, plans with benefits more suited to their health needs, or plans with preferable provider networks (Jacobson et al., 2014). In order to do this, seniors need to be able to process large amounts of information to evaluate all possible options available, which appears to be different among switchers and nonswitchers (Han & Urmie, 2018). Plan stickiness appears to be related to plan satisfaction, low premiums, and a general consensus that the perfect plan does not exist and trade-offs need to be made (Jacobson et al., 2016). Participants in our study were highly satisfied with their plan. Additionally, as found in prior research, beneficiaries with high needs are more likely to switch plans than their counterparts (Meyers, Belanger, et al., 2019). For instance, changes in premiums have been reported to be the strongest predictor of switching among both high needs and nonhigh needs patients, where a $100 increase in the following year was associated with a 35% to 40% increase in the probability of switching plans (Meyers, Belanger, et al., 2019). In the present study, some seniors mentioned that they would only consider switching plans if their health declined.

Others have noted that while high-quality star ratings appear to be an important predictor among beneficiaries enrolling in MA for the first time, it appears to be less important for those switching plans (Reid et al., 2013, 2016). In the present study, respondents were not aware of the Star Rating System and did not directly mention the concept of quality as a factor influencing their decision making. Our participants instead described different domains that are related to the composite measure (i.e., staying healthy, experience with health plan/providers and customer service) as important components of their health plan. Of note, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rates all (100%) of the available MA plans in Rhode Island as 4 or 5 stars, compared with 72% of plans nationally ranked 4 stars and above, which may affect participants’ own plan ratings. However, these plans have variations in terms of coverage, benefits (e.g., telehealth, transportation, home safety devices and modifications, fitness benefits) and cost-sharing (e.g., drug deductibles and copays). In addition, enrollment in higher star-rating plans may be related to greater marketing practices for highly rated plans among these companies. Some participants in our study mentioned that they attend sessions at different community centers seeking advice from insurance representatives leading the sessions, which may influence their enrollment choices. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with another qualitative study that found that star ratings did not play a role in enrollment choices (Jacobson et al., 2014).

Our study has some limitations. Given the qualitative nature of the present study, our results may not be generalizable and should be considered exploratory. We interviewed people from different backgrounds from Rhode Island, which has a moderate to high penetration rate (~40%) and is comparable to the national average (Jacobson et al., 2019). These participants may differ in their experiences from nonparticipants or from people in other states. However, our study findings are consistent with findings from other qualitative studies among Medicare Part D beneficiaries that participated in focus groups in different states (Jacobson et al., 2014; Stults et al., 2018). Nevertheless, our study is among the first to interview MA beneficiaries about their decision-making processes about plan choice and selection, providing direct experiences from MA enrollees. Additional research could also explore differences in decision-making process among a wider range of people from different markets and people with and without cognitive impairment, as well as exploring the role that family members and stakeholders play when beneficiaries choose a plan.

Our work has policy implications. With the recent initiative from the federal government to expand MA plans (The White House, 2019), it is unlikely that beneficiaries’ coverage-related decisions will become simpler or easier to make, and unbiased help from advisors (e.g., State Health Insurance Assistance Programs) may be scarce. About half of the participants from this study, especially among those with lower levels of education, reported different levels of confusion about the Medicare program overall. Making health insurance choices can be highly technical and complex, specifically among people with low income and low education, which is ~40% of the MA beneficiaries (America’s Health Insurance Plans, 2015). Despite the promise of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ tool, Medicare Plan Compare, to help seniors making choices, the majority of our participants do not use this website, according to our research. In addition, for those beneficiaries who use the site, the Plan Compare tool is missing important information regarding out-of-pocket costs and value (Jaffe, 2019). Using these resources properly requires insurance literacy that the majority of these seniors were lacking. Seniors generally understood premiums, as it is relatively straightforward to determine how much they will owe if they go to the primary care doctor or the specialist, but less than half mentioned other cost-sharing. Although MA is required to provide a catastrophic cap on out-of-pocket spending, plans have flexibility in benefit design. There was little consideration about future costs among our participants, which may influence switching and disenrollment among beneficiaries with more complex care needs.

MA beneficiaries who experience health decline or adverse health events tend to disenroll from MA at higher rates (Meyers, Belanger, et al., 2019). However, these enrollees often face higher cost-sharing as only four states guaranteed issue protections for Medigap (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, New York) and may have to pay higher premiums, often resulting in reenrollment in MA (Boccuti et al., 2018; Jacobson et al., 2018; Meyers, Trivedi, et al., 2019). These low-income seniors already face issues with affording “better plans” and were often enrolled in no premium plans, which poses the question as to whether these participants, especially those with low income are putting off care due to cost. Any additional restrictions in the Medicare program may place further limits on their choices and affordability of care. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services efforts to improve health care needs among MA beneficiaries include the creation of Chronic Disease Special Needs Plans (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020). Companies have flexibility to tailor benefits to specific populations (Wynne & LaRosa, 2020). At the moment, there are a few nursing home and assisted living plans in Rhode Island, but it would be important to assess whether these programs are expanded in the future and whether there is any uptick in the future, as many of these benefits may be valuable among these populations.

To encourage beneficiaries to plan compare, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is using marketing strategies to make seniors aware of the different tools during open enrollment, such as using radio and television ads (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2019). However, additional interventions are needed to ensure that millions of beneficiaries in MA—particularly vulnerable enrollees with cognitive decline—have the tools and resources to select insurance options that best meet their informed preferences. Interventions could include modifications to the design of the site, along with interviewing seniors to determine their understanding of the site and its link to making optimal decisions. In addition, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services statistics about site traffic may be useful to implement different interventions to increase utilization of these resources among consumers. Finally, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services may need to assess the knowledge about star ratings among beneficiaries and/or family members since one of the goals of the star rating system is to provide information to consumers regarding plan quality and improve choice into high-quality plans.

Conclusions

Findings from our interviews with MA beneficiaries plan provided information regarding the decision-making process that seniors take when considering switching plans or sticking to their current plan. Among the factors influencing these choices included costs, health status, providers, and satisfaction. Choosing health insurance coverage is overwhelmingly complex, and with future program implementations, MA could become even more complex. Most beneficiaries report keeping their plan, perhaps because they are unaware of their choices or are afraid to switch to something worse. Seniors may benefit from interventions to improve plan decision making, especially during open enrollment.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers (K01AG05782201A1; R03AG054686) and by Institutional Development Award Number U54GM115677 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, which funds Advance Clinical and Translational Research (Advance-CTR).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Abaluck J, & Gruber J (2011). Choice inconsistencies among the elderly: Evidence from plan choice in the Medicare Part D program. American Economic Review, 101(4), 1180–1210. 10.1257/aer.101.4.1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abaluck J, & Gruber J (2013). Evolving choice inconsistencies in choice of prescription drug insurance (Working Paper No. 19163). National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w19163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- America’s Health Insurance Plans. (2015). Medicare Advantage Demographic Report. https://www.ahip.org/medicare-advantage-demographics-report-2015/ [Google Scholar]

- Basu R (2015). Inertia or actual switching on medication adherence and economic well-being of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D plans. Value in Health, 18(3), PA144. 10.1016/j.jval.2015.03.839 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berki SE, & Ashcraft MLF (1980). HMO enrollment: Who joins what and why: A review of the literature. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly: Health and Society, 58(4), 588–632. 10.2307/3349807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccuti C, Jacobson GA, Orgera K, & Newman T (2018). Medigap enrollment and consumer protections vary across states. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medigap-enrollment-and-consumer-protections-vary-across-states/ [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2019). CMS: Medicare Open Enrollment Period Outreach & Media Materials. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Reach-Out/Find-tools-to-help-you-help-others/Open-Enrollment-Outreach-and-Media-Materials

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2020). Special Needs Plans (SNP). https://www.medicare.gov/sign-up-change-plans/types-of-medicare-health-plans/special-needs-plans-snp

- Cline RR, Worley MM, Schondelmeyer SW, Schommer JC, Larson TA, Uden DL, & Hadsall RS (2010). PDP or MA-PD? Medicare Part D enrollment decisions in CMS Region 25. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy, 6(2), 130–142. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree BF, & Miller WL (1999). Doing qualitative research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Curry L, & Nunez-Smith M (2015). Mixed methods in health sciences research: A practical primer. Sage. 10.4135/9781483390659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fusch PI, & Ness LR (2015). Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qualitative Report, 20(9), 1408–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Gadbois EA, Gordon SH, Shield RR, Vivier PM, & Trivedi AN (2019). Quality management strategies in Medicaid managed care: Perspectives from Medicaid, plans, and providers. Medical Care Research and Review. Advance online publication. 10.1177/1077558719841157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, & Urmie J (2018). Medicare Part D beneficiaries’ plan switching decisions and information processing. Medical Care Research and Review, 75(6), 721–745. 10.1177/1077558717692883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss F, Leive A, McFadden D, & Winter J (2013). Plan selection in Medicare Part D: Evidence from administrative data. Journal of Health Economics, 32(6), 1325–1344. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoadley J, Cubanski J, Hargrave E, Summer L, & Huang J (2012). Medicare Part D: A first look at Part D plan offerings in 2013. http://kff.org/medicare/report/medicare-part-d-first-look-at-2013-plan-offerings/

- Hoadley J, Hargrave E, Merrel K, Cubanski J, & Neuman T (2006). Benefit design and formularies of Medicare drug plans: A comparison of 2006 and 2007 offerings: A first look. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://suddenlysenior.com/pdf_files/plandoptions.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hoadley J, Hargrave E, Summer L, Cubanski J, & Newman T (2013). To switch or not to switch: Are Medicare beneficiaries switching drug plans to save money? http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/to-switch-or-not-to-switch-are-medicare-beneficiaries-switching-drug-plans-to-save-money/

- Jacobson G, Freed M, Damico A, & Neuman T (2019). A dozen facts about Medicare Advantage in 2019. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/a-dozen-facts-about-medicare-advantage-in-2019/ [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson GA, Neuman P, & Damico A (2015). At least half of new Medicare Advantage enrollees had switched from traditional Medicare during 2006–11. Health Affairs, 34(1), 48–55. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson GA, Newman T, & Damico A (2016). Medicare Advantage plan switching: Exception or norm? http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-plan-switching-exception-or-norm/

- Jacobson GA, Swoope C, Perry M, & Slosar MC (2014). How are seniors choosing and changing health insurance plans? http://kff.org/medicare/report/how-are-seniors-choosing-and-changing-health-insurance-plans/

- Jaffe S (2019, October 8). As Medicare enrollment nears, popular price comparison tool is missing. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/as-medicare-enrollment-nears-popular-price-comparison-tool-missing-from-website/ [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2016a). Medicare Advantage. http://kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/medicare-advantage/

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2016b). Profile of Medicare beneficiaries by race and ethnicity: A chartpack. http://kff.org/medicare/report/profile-of-medicare-beneficiaries-by-race-and-ethnicity-a-chartpack/

- Layug L, & Carter R (2014). Navigating coverage: How behavioral factors affect decisions in health care plan selection. DU Press. https://dupress.deloitte.com/dup-us-en/focus/behavioral-economics/health-care-plan-selection.html [Google Scholar]

- Marzilli Ericson KM (2014). Consumer inertia and firm pricing in the Medicare Part D prescription drug insurance exchange. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6(1), 38–64. 10.1257/pol.6.1.38 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers DJ, Belanger E, Joyce N, McHugh J, Rahman M, & Mor V (2019). Analysis of drivers of disenrollment and plan switching among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. JAMA Internal Medicine, 179(4), 524–532. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers DJ, Trivedi AN, & Mor V (2019). Limited Medigap consumer protections are associated with higher reenrollment in Medicare Advantage Plans. Health Affairs, 38(5), 782–787. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman P, & Jacobson GA (2018). Medicare Advantage checkup. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(22), 2163–2172. 10.1056/NEJMhpr1804089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett D (2012). Qualitative and mixed methods in public health. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Reid RO, Deb P, Howell BL, Conway PH, & Shrank WH (2016). The roles of cost and quality information in Medicare Advantage plan enrollment decisions: An observational study. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(2), 234–241. 10.1007/s11606-015-3467-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid RO, Deb P, Howell BL, & Shrank WH (2013). Association between Medicare Advantage plan star ratings and enrollment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 309(3), 267–274. 10.1001/jama.2012.173925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice T (2013). The behavioral economics of health and health care. Annual Review of Public Health, 34, 431–447. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson CT (2019). Exposed: Why our health insurance is incomplete and what can be done about it.

- Shield R, Winblad U, McHugh J, Gadbois E, & Tyler D (2019). Choosing the best and scrambling for the rest: Hospital–nursing home relationships and admissions to post-acute care. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 38(4), 479–498. 10.1177/0733464817752084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinaiko AD, Afendulis CC, & Frank RG (2013). Enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans in Miami-Dade County: Evidence of status quo bias? (Working Paper No. 19639). National Bureau of Economic Research. 10.3386/w19639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stults CD, Baskin AS, Bundorf MK, & Tai-Seale M (2018). Patient experiences in selecting a Medicare Part D prescription drug plan. Journal of Patient Experience, 5(2), 147–152. 10.1177/2374373517739413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The White House. (2019). Executive order on protecting and improving Medicare for our nation’s seniors. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-protecting-improving-medicare-nations-seniors/

- Weinick R, Haviland A, Hambarsoomian K, & Elliott MN (2014). Does the racial/ethnic composition of Medicare Advantage plans reflect their areas of operation? Health Services Research, 49(2), 526–545. 10.1111/1475-6773.12100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston C, Gandell T, Beauchamp J, McAlpine L, Wiseman C, & Beauchamp C (2001). Analyzing interview data: The development and evolution of a coding system. Qualitative Sociology, 24(3), 381–400. 10.1023/A:1010690908200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne B, & LaRosa J (2020, February 10). CMS releases advance notice for Medicare Advantage and Part D plans. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200210.336746/full/ [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, & Zhang Y (2012). The vast majority of Medicare Part D beneficiaries still don’t choose the cheapest plans that meet their medication needs. Health Affairs, 31(10), 2259–2265. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.