Abstract

The correct development of a diploid sporophyte body and a haploid gametophyte relies on a strict coordination between cell divisions in space and time. During plant reproduction, these divisions have to be temporally and spatially coordinated with cell differentiation processes, to ensure a successful fertilization. Armadillo BTB Arabidopsis protein 1 (ABAP1) is a plant exclusive protein that has been previously reported to control proliferative cell divisions during leaf growth in Arabidopsis. Here, we show that ABAP1 binds to different transcription factors that regulate male and female gametophyte differentiation, repressing their target genes expression. During male gametogenesis, the ABAP1-TCP16 complex represses CDT1b transcription, and consequently regulates microspore first asymmetric mitosis. In the female gametogenesis, the ABAP1-ADAP complex represses EDA24-like transcription, regulating polar nuclei fusion to form the central cell. Therefore, besides its function during vegetative development, this work shows that ABAP1 is also involved in differentiation processes during plant reproduction, by having a dual role in regulating both the first asymmetric cell division of male gametophyte and the cell differentiation (or cell fusion) of female gametophyte.

Keywords: male gametophyte differentiation, female gametophyte differentiation, ABAP1, DNA replication, TCP, ADAP

Introduction

The life cycle of higher plants alternates between the growth of a diploid sporophytic body and a haploid gametophytic form. The correct development of both generations relies on a strict coordination between cell division and cell differentiation in space and time (Harashima and Schnittger, 2010). The plant body grows mainly as a result of the increase in cell numbers through proliferative and symmetric cell divisions, producing cells of the same size and fate (De Smet and Beeckman, 2011; Rasmussen et al., 2011). In parallel, the formative and asymmetric divisions generate daughter cells of distinct sizes and identities, having an important role in the differentiation of cell types (Kajala et al., 2014).

A proper temporal and spatial coordination between cell division and differentiation during development of both gametophytes is essential for a successful plant reproduction. After meiosis, asymmetric mitotic cell divisions participate in the differentiation of male gametophyte, by forming a large vegetative cell (VC) and a small generative cell (GC) that subsequently divides symmetrically, forming the two sperm cells (Borg and Twell, 2010; Twell, 2011). During female gametogenesis, cell polarity is a key event for the differentiation of the female gametophyte in the mature embryo sac, which is finally composed of seven cells: three antipodal cells at the chalaza; two synergids and the egg cell at the micropyla; and a central cell (Drews and Koltunow, 2011; Schmid et al., 2015). Although the cellular dynamics of male and female gametogenesis are well described, the underlying molecular and biochemical mechanisms temporally coordinating both processes remain to be elucidated.

G1/S transition is a key point of coordination between cell division and cell differentiation homeostasis (Sablowski and Carnier Dornelas, 2014). RETINOBLASTOMA-RELATED 1 (RBR1) is a key regulator of G1/S transition in Arabidopsis, having a critical role in integrating cell proliferation and differentiation during Arabidopsis sporophyte development (Berckmans and De Veylder, 2009; Harashima and Sugimoto, 2016). During leaf development, RBR1-E2F complex acts as a repressor of cell division in proliferating cells, inhibits the transition into endocycle entry, and prevents ectopic division and recurrent differentiation of guard cells (Park et al., 2005) by repressing the expression of a pre-replication complex (pre-RC) member – CDC6 - and other S-phase genes (Desvoyes et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis roots, RBR1 functions through associations with other proteins, by promoting cell differentiation in the root meristem and regulating asymmetric cell division in Arabidopsis root stem cell niche (Cruz-Ramírez et al., 2012; Weimer et al., 2012). Besides mediating female germline specification by repressing WUSCHEL (WUS) in megaspore mother cell, RBR1 is also involved in the control of both male and female gametophyte development, as rbr1-1 mutants showed supernumerary nuclei in the embryo sac and in pollen grains (Ebel et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2017).

Armadillo BTB Arabidopsis Protein 1 (ABAP1) is another central player at G1/S transition in Arabidopsis through its dual role in the regulation of DNA replication and transcription. During Arabidopsis vegetative development, ABAP1 acts by balancing rates of proliferative cell divisions during leaf growth, through negatively regulating DNA replication and transcription, in a mechanism that controls the DNA replication factor CDT1a/b availability and consequently, the assembly of pre-RC (Masuda et al., 2008). In this work, we assessed ABAP1’s role during plant reproduction. We showed that ABAP1 is expressed in both male and female gametophytes and that ABAP1 imbalance impairs both male and female gametogenesis. The fundamental molecular and biochemical mechanisms of action of ABAP1 were determined in the gametophytic development context. Protein pull down, Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays revealed that ABAP1 binds to the transcription factors TCP16 (a class I TCP) and ARIA-interacting Double AP2-domain (ADAP, a member of AINTEGUMENTA family), repressing their target genes expression in the male and female gametogenesis, respectively. The ABAP1-TCP16 complex binds to the CDT1b promoter to repress its transcription and consequently regulate microspore first asymmetric cell division in the male gametophyte. Besides, the ABAP1-ADAP complex binds to the Embryo sac Development Arrest 24-like (EDA24-like) promoter, repressing its transcription and regulating polar nuclei fusion to form the central cell in the female gametophyte. Therefore, ABAP1 is involved in the regulation of both formative cell division in male gametophyte and cell differentiation (or cell fusion) in female gametophyte, two processes that are essential for a successful plant reproduction in Arabidopsis.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Columbia-0 (Col-0), Landsberg erecta (Ler), cdt1bKD (SALK_001276), and eda24-likeKD (SALK_121133) were obtained from Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC). ABAP1OE, abap1ET and ABAP1Pro:GUS lines were previously described (Masuda et al., 2008). Homozygous SALK lines were confirmed by PCR genotyping (primers are available in Supplementary Information).

Seeds were surface sterilized (70% ethanol for 2 min, 5% bleach for 10 min, dH2O washed for five times), plated in Murashige and Skoog agar plates [4.43 g L–1, 0.8% agar (w/v), 1% sucrose (w/v), 0.5 g L–1 MES] and kept at 4°C for 2 days prior to transfer to a growth room at 23°C with a 16 h light/8 h dark cycle. After 7 days, in vitro plants were transferred to a mixture of soil:vermiculite (2:1) and grown under the same conditions as described above.

Constructs

The full-length coding regions of ABAP1, TCP24, CDT1a, CDT1b, TCP16 and ADAP were PCR amplified with the specific primers as described in Supplementary Information and cloned into entry vectors pDONR201 or pDONR221. The entry clones were then recombined with destination vectors (pDEST15 and pDEST17 for protein expression in Escherichia coli; pDESTDBD and pDESTAD, for yeast two hybrid experiments). Vectors for ABAP1 and TCP24 overexpression in plants are described elsewhere (Masuda et al., 2008). All constructs were made using Gateway Technology (Invitrogen) except for in situ hybridization, where 1709 bp of CDT1a and 1461 CDT1b CDS fragments were cloned into pGEMT Easy Vector (Promega).

Microscopic Analysis

Plant material was harvested at the indicated developmental stages and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). Fixed material was processed for historesin or paraplast infiltration and then sectioned; or cleared for DIC microscopy observation. Details of microscopy analyses are available in the Supplementary Information.

Promoter GUS Experiments and in situ Hybridization

Flowers of 6-weeks-old homozygous ABAP1Pro:GUS plants grown in the soil were used for histochemical localization of GUS activity. GUS stained material was observed under light or DIC microscope (Axiophot, Zeiss). For more details, see Supplementary Information.

For in situ hybridization, open flowers and flower buds of 6-week-old plants were fixed and hybridized essentially as described previously (de Almeida Engler et al., 2001). Gene-specific sense and antisense probes of CDT1a and CDT1b genes were labeled using PCR DIG Probe Synthesis Kit (Roche). Probes were detected using an anti-digoxigenin antibody to which alkaline phosphatase had been conjugated (Roche Diagnostics). Images were analyzed in a stereomicroscope.

Quantitative Real Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and semi quantitative real time PCR were performed as described previously with minor modifications (Masuda et al., 2004). Total RNA was extracted from frozen materials (Logemann et al., 1987), treated with RNAse-free AmbionTM DNAse I and first strand cDNA was synthesized using “High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit” according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For qPCR, cDNA was amplified using SYBR-Green® PCR Master kit (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystem) on the GeneAmp 9600 thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) under standard conditions. Relative expression was calculated using 2−ΔΔCT method with UBQ14 as constitutive gene. qPCR values are means from three technical replicates and at least two biological replicates. Primer sequences for all genes used in qPCR are listed in Supplementary Information.

Microarray Experiment

Microarrays were based on the Arabidopsis Genome Oligo Set version 1.0 (Operon), manufactured as previously described (Wellmer et al., 2004) and were kindly donated by Dr. Elliot Meyerowitz (Caltech, United States). Plant material, RNA extraction, antisense RNA labeling, raw data processing and data analyses are described in Supplementary Information. Microarray data was deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (no. GEO: GSE164480, GSM5011985).

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay

Yeast two hybrid assay was carried out essentially as described by Masuda et al. (2008). Pairs of interacting proteins were cloned in both AD and DBD vectors and assayed for yeast two hybrid to reduce false positive results. For details, see Supplementary Information.

In vitro Protein Interaction Assay (GST-Pull Down)

ABAP1-GST, AtTPC24-GST, TCP16-HIS and ADAP-HIS were expressed in E. coli strain BL21 as described previously (Chekanova et al., 2000), with modification in the lysis buffer [25 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 mM leupeptin, and 75 mM aprotinin]. GST-pull down analyses were carried following a protocol described elsewhere (Tarun and Sachs, 1996). For details, see Supplementary Information.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed essentially as described previously (Masuda et al., 2008). Details on experimental procedure and sequences probes are available in Supplementary Information.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP), PCR Amplification and qRT-PCR Experiment

Flower buds of wild-type (Col-0) and ABAP1OE were collected, fixed in 1% formaldehyde under vacuum for 15 min followed by 5 min incubation in 100 mM glycine to stop the crosslinking, frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80°C. Chromatin isolation and immunoprecipitation was carried out as described before (Gendrel et al., 2005) with minor modifications (an extra 5 min wash was added at each washing step). Anti-ABAP1 polyclonal antibody described elsewhere (Masuda et al., 2008) was used in the IP step. ABAP1-IP gDNA, input gDNA and mock-IP gDNA were used in PCR amplification using primers specific to promoter and coding regions of EDA24-like, CDT1a and CDT1b. Whole cell extract, immunoprecipitated WT and immunoprecipitated ABAP1OE materials were used in qRT-PCR. For ChIP-qPCR, ChIP DNA was analyzed by qPCR using the indicated primer pairs (sequences are available in Supplementary Information). Relative enrichment for each fragment was calculated first by normalizing the amount of the amplified DNA fragment with the Actin 2 fragment, and then the ratio of ABAP1OE/wild-type was calculated using the following equation: 2(CtABAP1OE Actin 2–CtABAP1OE ChIP fragment)/2(CtWT Actin 2–CtWT ChIP fragment). Each PCR was repeated three times, the mean value of technical replicates was recorded for each biological replicate and error bars represent the SD from three independent experiments.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found at the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative database with the following accession numbers: ABAP1 (At5g13060), Actin 2 (At3g18780), UBQ14 (AT4G02890), CDT1a (At2g31270), CDT1b (At3g54710), TCP16 (AT3G45150), EDA24-like (At1g23350), and ADAP/WRI3 (At1g16060).

Results

Deregulation of ABAP1 Expression Affects Plant Reproduction

To assess if ABAP1 has a role during plant reproduction processes, plants with increased or reduced expression levels of ABAP1 were characterized. The studies were performed with Arabidopsis plants expressing 5- to 17-fold and 2- to 5-fold higher levels of ABAP1 mRNA and protein, respectively (ABAP1OE) and a heterozygous enhancer trap line (abap1ET) showing a two and five fold reduction in ABAP1 mRNA and protein levels, respectively (Masuda et al., 2008).

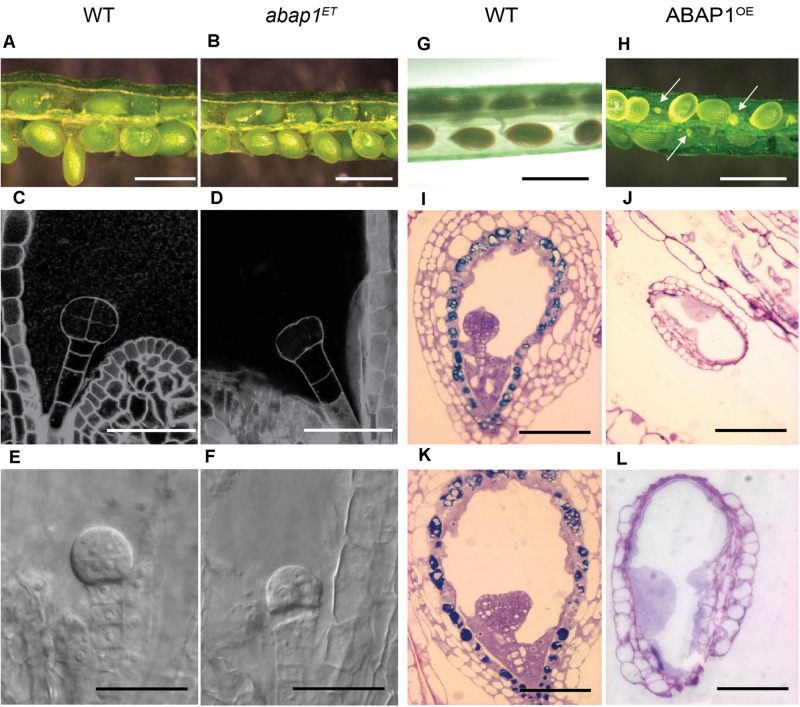

Homozygous plants could not be rescued in either the abap1ET or in the ABAP1OE lines, suggesting that extreme up or down-regulation of ABAP1 can cause a lethal phenotype. Microscopic analyses of seed development showed that embryogenesis was arrested at pre-globular stage in 32% of the abap1ET seeds (compare Figures 1C,E with 1D,F). Nevertheless, at later stage (mature green), seeds formed seed coat, and no difference in size and color was observed among the seeds in a complete silique (Figure 1B) when compared to the wild-type silique (Figure 1A). Germination frequency was quantified and 32% of abap1ET seeds did not germinate, in correspondence with the frequency of arrested embryos observed earlier after fertilization.

FIGURE 1.

Embryo development in plants with altered levels of ABAP1. Images of siliques at the same developmental stages, comparing embryo and seed development in wild-type (WT) and mutant plants. Left panels (A–F) shows comparison between WT and abap1ET plants. (A,B) Open siliques of WT and abap1ET plants showing normal seed size. (C–F) Initial events in embryo development from WT and abap1ET seeds. Dark field illumination microscopy of WT seeds with embryo at 8 cell stage (C), and abap1ET seeds with the embryo at the initial zygotic divisions (D). Nomarski microscopy of embryos from WT plants at globular cell stage (E) and from abap1ET plants with defects after the initial zygotic divisions (F). Right panels (G–L) shows comparisons between WT and ABAP1OE plants. (G) Open WT siliques with normal developing seeds; and (H) open ABAP1OE siliques with small and shriveled seeds (arrows). (I,K) Micrographs of sections of WT seeds with embryos at globular (I) and transition to early heart stages (K). (J,L) Micrographs of sections of ABAP1OE seeds that did not develop and/or arrested before fertilization (J). (L) is a higher magnification of (J). Scale bars: 1 mm in (A,B,G,H); 20 μm in (C–F); 100 μm in (I–K); and 50 μm in (L). For abap1ET and WT Landsberg erecta background plants, a total of 300 seeds in 15 siliques were analyzed for each genotype. For ABAP1OE a total of 708 seeds were analyzed in 36 siliques, and for Col-0 WT plants 432 seeds were analyzed in 18 siliques.

ABAP1OE plants, however, produced siliques shorter than those in wild- type plants and exhibited an average of 53–62% undeveloped, very small and white colored seeds compared to wild-type plant seeds (Figures 1G,H). The ABAP1OE mutant phenotype was different from the abortion seed phenotype observed in orc2 (Collinge et al., 2004), ttn4 (Tzafrir et al., 2002), and raspberry (Yadegari et al., 1994) mutants. Microscopic analyses of ABAP1OE siliques indicated that embryogenesis was not seen in the undeveloped seeds, suggesting that either gametogenesis, fertilization or zygote activation was impaired (Figures 1I–L). Abnormal structures within the embryo sac, that could suggest formation of endosperm, were observed in ABAP1OE seeds.

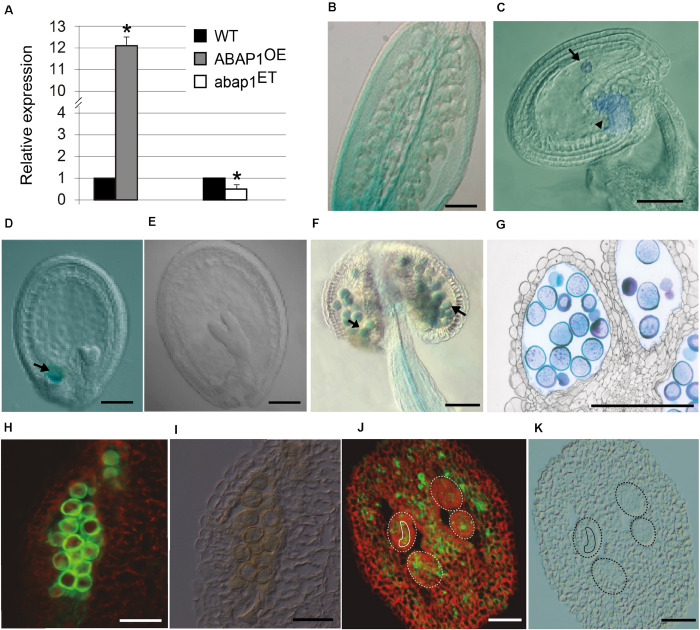

Previous studies on ABAP1 gene expression have shown high GUS activity in developing flower buds, with strong expression in the ovary and petals (Masuda et al., 2008). qRT-PCR was used to confirm that ABAP1 mRNA levels were altered in mutant flower buds, showing a 12-fold increase in ABAP1OE and a two-fold reduction in abap1ET lines (Figure 2A). To determine the spatial localization of ABAP1 expression in Arabidopsis gametogenesis, ABAP1Pro:GUS plants were analyzed. GUS activity was detected overall the ovary (Figure 2B). A time-lapse investigation of GUS activity indicated that ABAP1 expression remained in the chalaza and in the embryo very early after fertilization (Figure 2C), decreased at mid-heart stage (Figure 2D) and disappeared only during the torpedo stage of embryo development (Figure 2E).

FIGURE 2.

ABAP1 expression in flowers. (A) Relative mRNA levels of ABAP1 were determined by qRT-PCR in wild-type, ABAP1OE and abap1ET flowers. Data were normalized with UBQ14 as reference gene and were compared with wild-type. Data shown represent mean values obtained from independent amplification reactions (n = 3) and biological replicates (n = 2). Each biological replicate was performed with a pool of 15 inflorescences. Bars indicate mean ± standard error of biological replicates. A statistical analysis was performed by t-test (p-value < 0.05). Asterisks (*) indicate significant changes. (B–G) Nomarski microscopy of cleared tissues. (B) promABAP1:GUS activity in the ovary prior to fertilization. (C) promABAP1:GUS activity early after fertilization. Arrow and arrowhead point to embryo and chalaza expression, respectively. (D) Decrease in GUS activity in embryos of 72 h (heart stage). The expression in the chalazal chamber, however, remains (arrow). (E) In torpedo stage, GUS activity is not seen neither in the embryo or chalaza. (F) promABAP1:GUS activity in anthers. Arrow points to GUS activity in pollen. (G) Cross section of anthers with promABAP1:GUS activity in pollen. (H,J) Localization of ABAP1 protein by epifluorescence of reproductive tissues using anti-ABAP1 antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 and (I,K) corresponding DIC microscopy. (H,I) ABAP1 protein localization in a pollen sac cross section. (J,K) ABAP1 protein localization in cross section of ovary and ovules. Dashed lines indicate the perimeter of ovules and the full line is around the embryo sac. The scale bars correspond to 100 μm in (B), 20 μm in (C–G), and to 10 μm in (H–K).

During male gametogenesis, GUS assays indicated that ABAP1 is expressed in pollen and is regulated according to its developmental stage, since it appears only after microsporogenesis. Thus, ABAP1 is present during pollen differentiation, around stage 10–11 of anther development (Figures 2F,G), when the first mitotic asymmetric cell division occurs (Sanders et al., 1999).

ABAP1 expression in wild-type was also confirmed by immunolocalization in pollen (Figures 2H,I) and ovary, including the ovules and embryo sac (Figures 2J,K) by using anti-ABAP1 antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488. During male gametogenesis, immunolocalization experiments suggest that ABAP1 is initially present at low levels in the tetrads. As gametogenesis proceeds, higher levels of ABAP1 are observed in the vacuolate stage of microspore, before the first mitotic division. Then, its levels decrease at subsequent stages of gametogenesis (Supplementary Figure 1). Immunolocalization of ABAP1 protein was also analyzed in ABAP1OE plants (Supplementary Figure 2) confirming that plants overexpressing ABAP1 under the control of the 35S promoter have a higher fluorescence signal in the reproductive organs, including the male and female gametophytes (Supplementary Figures 2C–H), when compared to the wild-type plant (Supplementary Figures 2A–F). Immunofluorescence controls without anti-ABAP1 antibody or using pre-immune serum did not show fluorescent signal (Supplementary Figures 2I–P).

Altogether, the data showed that ABAP1 has a very specific spatial and temporal expression during the gametophytic phase and that its deregulation affects plant reproduction. Down regulation of ABAP1 disturbed initial mitotic cell divisions in the embryo formation after fertilization, possibly due to its essential role in DNA replication and mitotic cell division. On the other hand, plants with higher levels of ABAP1 lacked developing embryos in the shriveled seeds, suggesting that either fertilization or zygote activation is defective in ABAP1OE. Because ABAP1 is a transcriptional repressor, higher levels of ABAP1 could potentially enhance the repression of important genes for these processes or in the gametogenesis, representing a novel role other than the one in proliferative cell division.

Plants With Ectopic Expression of ABAP1 Have Defects in Pollen Development

To establish the basis for the reduced fertility of ABAP1OE plants, we analyzed whether higher levels of ABAP1 interfered in the different processes of flower development. Defects were found exclusively in male and female gametophytes development.

Optical microscopic analyses were performed at different stages of the male gametophyte development of ABAP1OE and of the wild-type plants (Supplementary Figure 3). The first phenotypic differences were noticed after meiosis, at stage 11 of flower development, when the cytoplasm of some pollen grains from ABAP1OE flowers retracted (Supplementary Figure 3D). At this stage, the first asymmetric mitotic division (Pollen Mitosis I, PMI) is supposed to happen. At stage 12, when the bilocular anther is formed and the pollen grains are mature, 45% of pollen grains were malformed and shriveled in the anthers of the ABAP1OE flowers (Supplementary Figure 3E).

To determine in which stage of male gametogenesis ABAP1OE was affected, nuclei of microspores at different developmental stages of gametogenesis were visualized by DAPI staining. The anthers were collected at stages 10, 11, and 12 of flower development (Smyth et al., 1990), which correspond to male gametophytes with one, two, and three nuclei in wild-type plants, respectively (Figure 3A, upper line and Figure 3B). Male gametophyte of plants with higher levels of ABAP1 presented only one diffuse nucleus, suggesting that they were arrested before Pollen Mitosis I (PMI), the asymmetric cell division that forms the vegetative and generative cells (Figure 3A, middle line). This phenotype resembles the one observed in cdt1bKD mutants (Figure 3A, bottom line), a pre-RC component and target of ABAP1 regulation mediated by TCP24 (Masuda et al., 2008). Pollen germination assays showed that normal shaped pollen grains from wild-type flowers germinated normally (Figure 3A, upper line), while shriveled pollen from ABAP1OE anthers could not germinate (Figure 3A, middle line). These results suggest that ABAP1 may regulate male gametophyte development at PMI.

FIGURE 3.

Defective pollen maturation in ABAP1OE plants. (A) Pollen grains stained with DAPI in different developmental stages, in WT plants (upper line), ABAP1OE plants (middle line) and cdt1bKD (bottom line). (B) Schematic representation of the series of events taking place after meiosis, during the maturation of the male gametophyte in Arabidopsis. PMI and PMII are the two mitotic divisions necessary for the male gametophyte development. Red arrows indicate marker genes of pollen developmental stages. Blue arrows indicate the stages when CDT1b might be required for mitotic cell division. (C) Relative mRNA levels of ABAP1, CDT1a, CDT1b, TCP16, Myb33, and HAP2 were determined by qRT-PCR in wild-type and ABAP1OE anthers at stage 12 of development (according to Sanders et al., 1999). Data were normalized with UBI14 as reference gene and were compared with wild-type. Each biological replicate was performed with a pool of 50 anthers. Bars indicate mean ± standard error of biological replicates. A statistical analysis was performed by t-test (p-value < 0.05). Asterisks (∗) indicate significant changes. (D) CDT1b mRNA levels in wild-type and ABAP1OE anthers using whole mount in situ hybridization with anti-sense probes. Hybridization signals are seen as purple dots under bright field optics. The scale bars represent 20 μm in (A) and 0.2 mm in (D).

ABAP1 Interacts With TCP16 and Regulates CDT1b Levels in the Male Gametophyte

In leaves, ABAP1 negatively regulates mitotic cell divisions by repressing CDT1a and CDT1b expression, in an association with the transcription factor TCP24 (Masuda et al., 2008). To determine the molecular mechanisms behind ABAP1’s effects on the first mitotic division of pollen development, a mechanism similar to the one regulating mitotic proliferative cell divisions was tested.

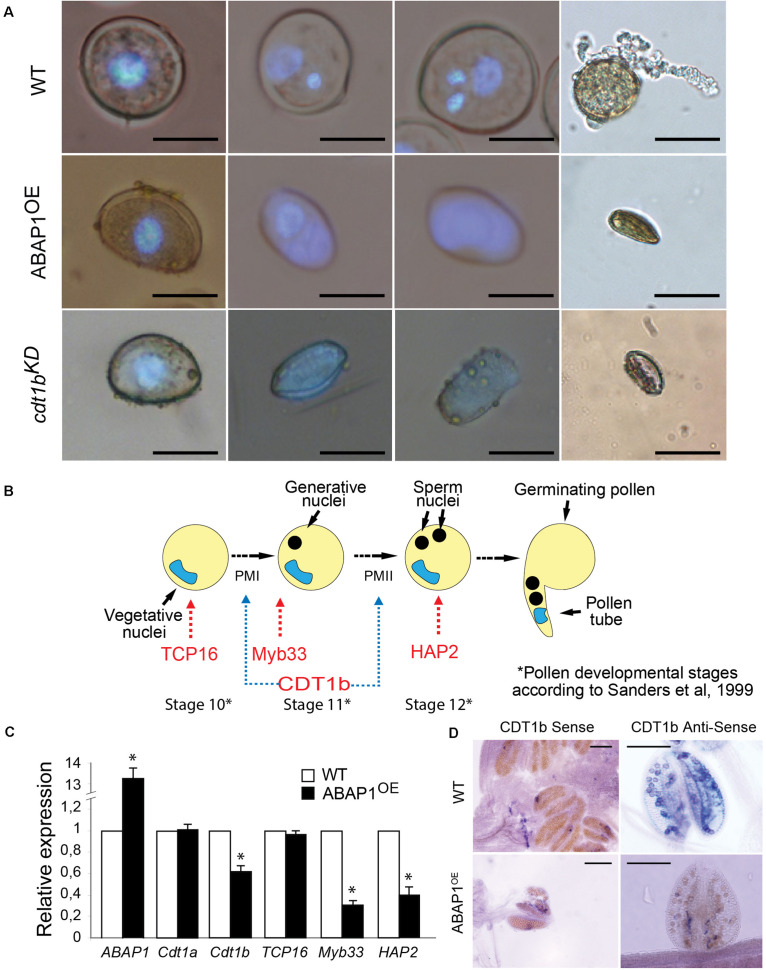

The TCP24 transcription factor is not significantly expressed during male gametogenesis, as determined in public microarray datasets; therefore, another TCP partner was searched. TCP16 acts regulating early pollen development, since reduced levels of TCP16 prevented PMI to occur, in a similar phenotype as the one observed in ABAP1OE pollen (Takeda et al., 2006). TCP16 is highly expressed at the polarized microspore stage (Takeda et al., 2006) similar to what was observed to ABAP1 by immunolocalization experiments (Supplementary Figures 1C,D). Therefore, the association of TCP16 with ABAP1 was tested in yeast two-hybrid experiments that showed strong interaction between the two proteins (Figure 4A). The formation of ABAP1-TCP16 complex was further confirmed in vitro, in a GST-pull down assay with ABAP1-GST and TCP16-HIS in which TCP16 bound to ABAP1 (Figure 4B, lane 1) but not to GST alone (Figure 4B, lane 2). The ABAP1 interaction with TCP16 in Arabidopsis flowers was demonstrated in a semi in vivo HIS-pull down experiment, where HIS-fused TCP16 was added to protein extracts of Arabidopsis flowers buds, purified in a nickel column and tested for the presence of ABAP1 with anti-ABAP1 antibody (Supplementary Figure 4A, lane 4).

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of the interaction between ABAP1 and TCP16 and their role in transcription. (A) Yeast two hybrid interaction assays between ABAP1 and cloned in both AD and BD vectors. Negative controls used DAD and DBD empty vectors. The panel shows conjugated yeasts growing in SD medium lacking leucine, tryptophan, histidine and adenine, for selection of strong protein interactions. (B) GST-pull down assay between ABAP1–GST and TCP16-HIS produced in E. coli. Western blot analysis used anti-HIS antibody. Lane 1, TCP16-HIS with ABAP1-GST; lane 2, TCP16-HIS with GST alone; lanes 3 and 4, 1/10 inputs of ABAP1-GST and TCP16-HIS, respectively. (C) EMSA of ABAP1, TCP16 and the complex TCP16–ABAP1 with wild-type (WT) and mutated (mut) radiolabeled probes of CDT1b promoter regions harboring TCP recognition box. Lane 1, TCP16 binds to CDT1b WT probe; lane 2, addition of ABAP1 causes a supershift in the TCP16 binding to CDT1b WT probe; GST alone (lane 3) or ABAP1 alone (lane 4) do not bind to CDT1b WT probe; lane 5, TCP16 does not bind to CDT1b mutated probe. (D,E) Chromatin immunoprecipitation of wild-type Col (WT) and ABAP1OE flower buds with anti-ABAP1. (D) Schematic representation of the amplified regions of CDT1b. Black triangle indicates the class I TCP motif, located at position –130 to –136 bp. Red arrows and numbers indicate primers used for ChIP-qPCR assays, and short green line indicates DNA probe used for EMSA. The translational start site (ATG) is shown at position +1. (E) Chromatin immunoprecipitated with anti-ABAP1 antibody was analyzed by qPCR using gene-specific primer sets, numbered as indicated in (D). The graph shows the fold enrichment of qPCR amplified regions at the promoter (1, 2), and 3’UTR (3,4) of CDT1b. The fold enrichment of each amplified region was calculated as a ratio between IP ABAP1OE and IP WT of values normalized with values of the ACTIN 2 promoter. Error bars represent the SD of three biological replicates. Asterisk (∗) indicates significant difference from the enrichment according to Student’s t test (p-value < 0.05). IP, immunoprecipitated with anti-ABAP1 antibody.

Next, mRNA levels of CDT1a and CDT1b, two pre-RC genes whose expression levels are regulated by ABAP1-TCP24 in leaves, were investigated by qRT-PCR in mature anthers. TCP16 and two pollen developmental markers of pollen mitosis, Myb33 (Plackett et al., 2011) and HAP2 (von Besser et al., 2006), were also included in the analysis (Figures 3B,C). The results showed that in ABAP1OE anthers, the expression level of TCP16 and CDT1a were normal, while the levels of CDT1b, Myb33 and HAP2 were significantly reduced (Figure 3C). The reduction of CDT1b mRNA levels in pollen of ABAP1OE compared to levels in control plants was also confirmed by whole mount in situ hybridization assays in anthers (Figure 3D). The expression data corroborates the cellular analysis, supporting that the male gametophyte was arrested before PMI in ABAP1OE plants, as CDT1b, Myb33, and HAP2 were down regulated, and that TCP16 might participate in this control since its expression level is normal.

Remarkably, a consensus sequence for class I TCPs interaction (TGGGNCC) (Viola et al., 2011) is found in the promoter region of CDT1b (TGGGCCC position −130 to −136 bp), but not in CDT1a that harbors only a non-canonical TCP interaction sequence (TGGGCAC position −1,335 to −1,342 bp) (Figure 4D and Supplementary Figure 5). To address the possible cooperation of ABAP1 and TCP16 in the control of CDT1b gene transcription, the association between both proteins with CDT1b promoter was characterized. The ability of the ABAP1–TCP16 heterodimer to recognize the promoter regions of CDT1b was confirmed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) performed with probes containing the class I TCP consensus motif of CDT1b (Supplementary Information). TCP16 alone and TCP16–ABAP1 were associated with the wild-type probes (Figure 4C, lanes 1 and 2) but TCP16 alone did not associate with the mutated probe (Figure 4C, lane 5). Neither ABAP1 alone, nor GST associated with the wild-type probe (Figure 4C, lanes 3 and 4). The ABAP1-TCP16 binding to CDT1b, but not to CDT1a promoter, was confirmed in vivo in chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments of chromatin extracts of Arabidopsis flower buds, using anti-ABAP1 antibody (Supplementary Figure 5). The results revealed that ABAP1 was associated with regions of CDT1b promoter containing the class I TCP consensus motif (Supplementary Figure 5B), but not with CDT1a promoter (Supplementary Figure 5A). This interaction was detected in wild-type plants (Supplementary Figure 5B2, lane 3). Higher levels of association were consistently detected in ABAP1OE flower buds when compared to wild-type. The immunoprecipitated material was further amplified by qPCR with four different primer pairs specifically designed to hybridize along the CDT1b promoter and 3′UTR regions (Figure 4D). Amplification of IP DNA was significantly higher in the qPCR reactions using the pair of primers that hybridize closer to the class I TCP consensus motif. Amplification dropped as the distance to the TCP motif increased (Figure 4E).

Altogether, the data suggests that up-regulation of ABAP1 levels affects the progression of the first asymmetric cell division during male gametophyte development by associating with TCP16 and repressing CDT1b expression in pollen. This mechanism of action was further supported by analyses of pollen development in a CDT1b T-DNA insertion line (hereafter referred to as cdt1bKD). cdt1bKD showed a reduction of around 55% of CDT1b expression in anthers when compared to wild-type plants (Supplementary Figure 4B) and presented a similar phenotype as the one observed for ABAP1OE plants, with several shriveled pollen that were unable to germinate and could not undergo the first mitotic asymmetric division (Figure 3A, bottom line).

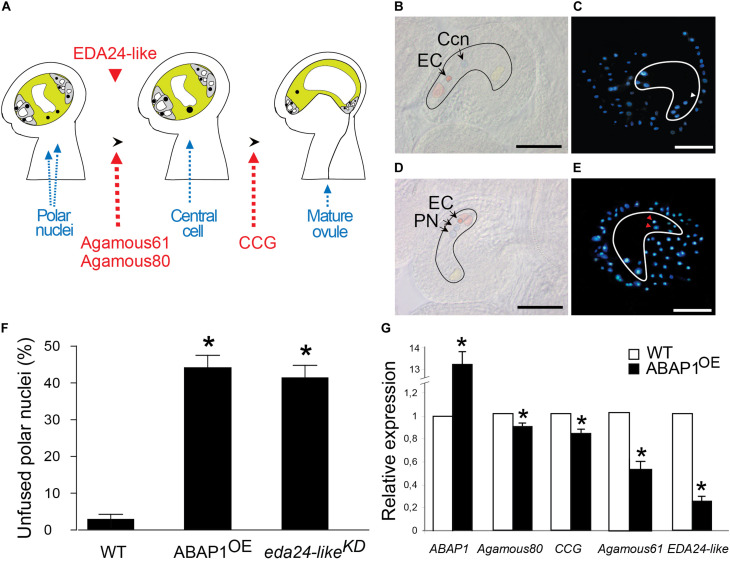

Plants With Ectopic Expression of ABAP1 Show Defects in Embryo Sac Development

To test whether defects on female gametophyte development could also be contributing to the reduced fertility of ABAP1OE plants, embryo sac differentiation was analyzed. Flower buds of ABAP1OE plants were emasculated and the embryo sac structure was analyzed at stage 13 of flower development (Smyth et al., 1990). At this stage, seven nuclei were visible in wild-type mature embryo sac corresponding to two synergids and the egg cell in the micropyla, the three antipodal cells in the chalaza and the 2n fused nuclei of the central cell in the median portion of the embryo sac (Figures 5A–E). Surprisingly, ovules from ABAP1OE flowers had eight instead of seven nuclei in the embryo sac due to unfused polar nuclei (Figures 5D,E). The polar nuclei were still present in 44% of ABAP1OE ovules in FG6 (seven celled) and FG7 (four celled) stages (Christensen et al., 1997), when the diploid central cell should have been formed (Figure 5F).

FIGURE 5.

Defective female gametophyte development in ABAP1OE. (A) Schematic representation of the events taking place during maturation of the female gametophyte. The final embryo sac is a polarized structure with two main distinct regions: the micropyla and the chalaza. Red arrows indicate gene markers of embryo sac developmental stages. Red arrowhead represents the timing of EDA24-like expression. (B–E) Micrographs of wild-type and ABAP1OE ovules. Embryo sacs and embryo sac cells were artificially outlined for better visualization. DIC microscopy (B) and DAPI staining (C) of wild-type ovules indicate the central cell nucleus (Ccn and white arrowhead) formed by fusion of the two polar nuclei. DIC microscopy (D) and DAPI staining (E) of ABAP1OE ovules show two unfused polar nuclei (PN and red arrowheads). EC, egg cell; Ccn, central cell nucleus; PN, polar nuclei. Scale bars at (B–E) represent 20 μm. (F) Percentage of unfused polar nuclei quantified in emasculated flowers at stage 13 (FG6-FG7) from wild-type Col, ABAP1OE and eda24-likeKD plants. For WT, 6 ovaries were analyzed, with a minimum of 25 and a maximum of 39 ovules analyzed per ovary. For ABAP1OE, 14 ovaries were analyzed, with a minimum of 25 and a maximum of 36 ovules analyzed per ovary. For eda24-likeKD, 8 ovaries were analyzed, with a minimum of 23 and a maximum of 34 ovules analyzed per ovary. A statistical analysis was performed by t-test (p-value < 0.05). Asterisks (*) indicate significant changes. (G) Relative mRNA levels of ABAP1, Agamous 80, CCG, Agamous 61 and EDA24-like were determined by qRT-PCR in wild-type and ABAP1OE flower buds. Data were normalized with UBI14 as reference gene and were compared with wild-type. Each biological replicate was performed with a pool of 15 flower buds. Bars indicate mean ± standard error of biological replicates. A statistical analysis was performed by t-test (p-value < 0.05). Asterisks (*) indicate significant changes.

The data suggested that ABAP1 is not required to regulate the mitotic divisions of the female gametogenesis but seems to be important in events regulating nuclear fusion (Figures 5D,E). A possible role of ABAP1 in the female gamete differentiation is further supported by the presence of ABAP1 protein in the embryo sac observed by immunolocalization experiments (Figures 2J,K), as well as its up-regulation in this structure observed in ABAP1OE plants (Supplementary Figures 2E–H).

ABAP1OE Down-Regulates Expression of Several Genes in Flower Bud

To get insights on the molecular mechanisms underlying the defects of male and female gametogenesis in ABAP1OE plants, transcripts of ABAP1OE and wild-type flower buds were compared in a microarray experiment. The studies were performed with flower buds of stage 13, since polar nuclei are already fused at this developmental stage (Smyth et al., 1990).

247 genes were differentially expressed in ABAP1OE plants, of which 226 were down regulated (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 6A). This is consistent with ABAP1’s role as a transcriptional repressor (Masuda et al., 2008). To validate the microarray data, the expression of some of these genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Figure 6B) revealing that they were in good agreement with those from the microarray experiment. GO term network was done using Cytoscape and showed an enrichment of GO terms (p < 0.05) related to transport, GTPase activity and pollen development/pollen tube growth in the down regulated genes of the array (Supplementary Figure 7A). This result is expected since male gametophyte development, and therefore the downstream events such as cell morphogenesis and pollen tube growth, was impaired in ABAP1OE plants. GO term enrichment in down regulated genes related to molecular function and cellular components showed genes involved in the endomembrane system as well as genes with pectinesterase and enzyme inhibitor activities (Supplementary Figures 7B,C).

Several Arabidopsis mutants with polar nuclear fusion defects were already characterized (Pagnussat et al., 2005; Portereiko et al., 2006b; Maruyama et al., 2016). One of these mutants is a pectinesterase inhibitor and was named eda24 (embryo sac development arrest 24) (Pagnussat et al., 2005). Although EDA24 gene expression was not altered in our array, its closest Arabidopsis homolog was down regulated in ABAP1OE flower buds. This gene was still uncharacterized and was named Embryo Sac Development Arrest 24-like (EDA24-like, AT1G23350). Thus, a possible participation of EDA24-like in the polar nuclei phenotype observed in ABAP1OE ovules was addressed. To evaluate the defect in embryo sac maturation of ABAP1OE plants, expression of ovule development marker genes and EDA24-like were investigated in ovaries through qRT-PCR. The mRNA levels of Agamous-like80 (AGL80), a transcription factor involved in central cell maturation (Portereiko et al., 2006a), and of the Central Cell Guidance (CCG), expressed at the final maturation step of embryo sac and that guides the pollen tube (Chen et al., 2007), were slightly but significantly reduced in ABAP1OE ovary (Figures 5A,G). A more drastic reduction in the expression level of Agamous-like61/DIANA, expressed exclusively at the central cell and early endosperm (Steffen et al., 2007; Bemer et al., 2008), and of EDA24-like were observed in ABAP1OE (Figures 5A,G), confirming the reduction of EDA24-like expression in ABAP1OE with unfused polar nuclei.

To assess the role of EDA24-like in the female gametophyte development, a SALK T-DNA insertion line with a 66% reduction in EDA24-like expression levels was analyzed and hereafter referred as eda24-likeKD (Supplementary Figure 4C). Remarkably, around 40% of the ovules in eda24-likeKD showed defects in polar nuclei fusion at FG6-FG7 stages, when the diploid central cell should have been formed (Figure 5F). This result is similar to the one observed in ABAP1OE ovules, strongly supporting that down regulation of EDA24-like might be contributing to the deficiency in embryo sac development observed in ABAP1OE plants.

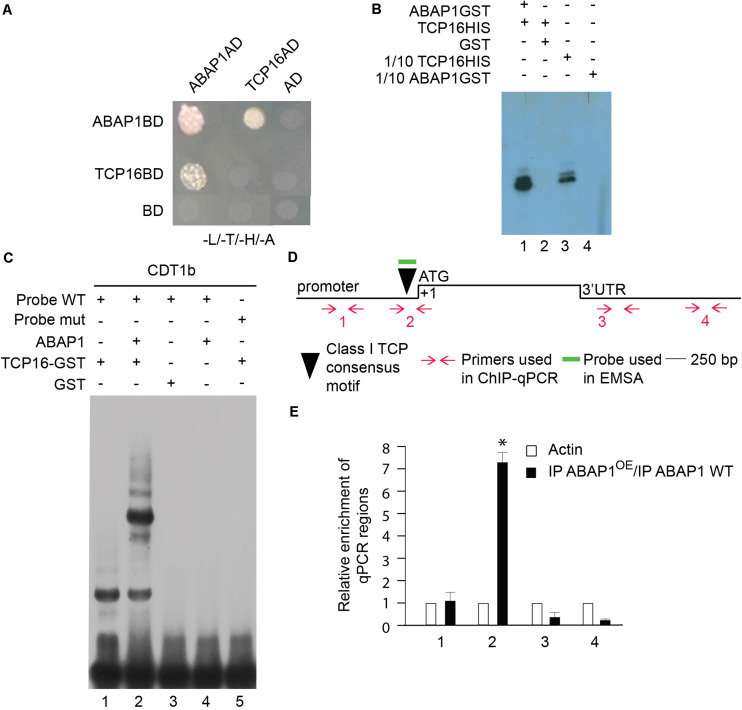

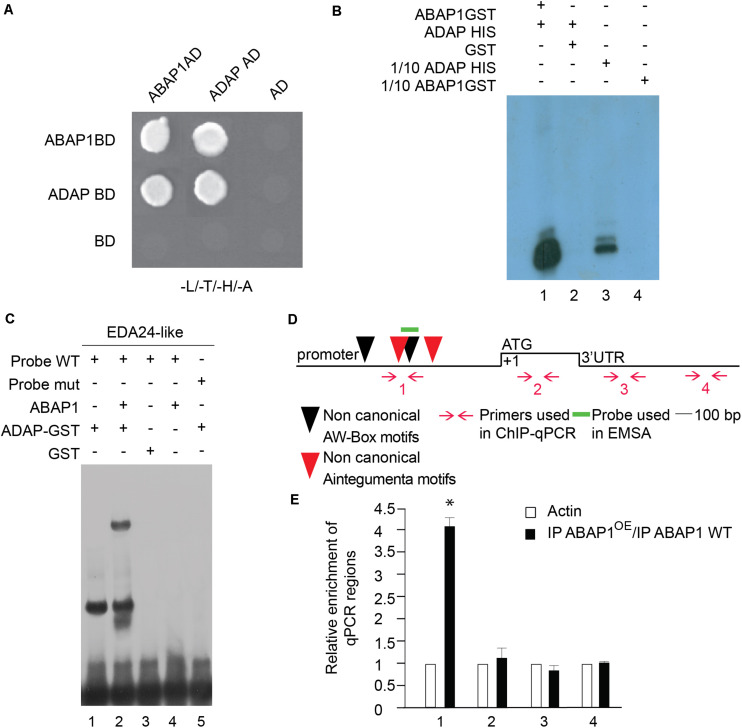

ABAP1 Interacts With ADAP and Regulates EDA24-Like Levels

ABAP1’s role as transcriptional repressor involves the association with a transcription factor (Masuda et al., 2008). To get insights into a possible partner of ABAP1 in the control of EDA24-like expression, the promoter region of EDA24-like was searched for transcription factors binding motifs. Two sequences of the non-canonical recognition sites of AINTEGUMENTA (ANT) [gCAC(A/G)N(A/T)TcCC(a/g)ANG(c/t)] (Nole-Wilson and Krizek, 2000) were found at positions −682 to −696 bp, −892 to −905 bp; and two non-canonical recognition sites of WRINKLED 1 (WRK1), the AW-box (CNTNG[(N)7]CG) (Maeo et al., 2009) were found at positions −828 to −842 and −1,151 to −1,166, suggesting a possible regulation of EDA24-like expression by APETALA2 (AP2)-type transcription factors (Figure 6D).

FIGURE 6.

Characterization of ABAP1 and ADAP interaction, and their role in transcription. (A) Yeast two hybrid interaction assays between ABAP1 and ADAP. Negative controls used AD and BD empty vectors. The panel shows conjugated yeasts growing in SD medium lacking leucine, tryptophan, histidine and adenine, for selection of strong protein interactions. (B) GST-pull down assay between ABAP1–GST and ADAP-HIS produced in E. coli. Western blot analysis used anti-HIS antibody. Lane 1, ADAP-HIS with ABAP1-GST; lane 2, ADAP-HIS with GST alone; lanes 3 and 4, 1/10 inputs of ABAP1-GST and ADAP-HIS, respectively. (C) EMSA of ABAP1, ADAP and the complex ABAP1-ADAP with wild-type (WT) and mutated (mut) radiolabeled probes of EDA24-like promoter region harboring ADAP recognition box. Lane 1, ADAP binds to EDA24-like WT probe; lane 2, addition of ABAP1 causes a supershift in the ADAP binding to EDA24-like WT probe; GST alone (lane 3) or ABAP1 alone (lane 4) do not bind to EDA24-like WT probe; lane 5, ADAP does not bind to EDA24-like mutated probe. (D,E) Chromatin immunoprecipitation of wild-type Col (WT) and ABAP1OE flower buds with anti-ABAP1 antibody. (D) Schematic representation of the amplified regions of EDA24-like gene. ANT non-canonical motifs (located at positions –682 to –696 bp and –892 to –905 bp) are represented as red arrowheads. AW-box non-canonical motifs (located at positions –828 to –842 bp and –1,151 to –1,166 bp) are represented as black arrowheads. Red arrows and numbers indicate primers used for ChIP-qPCR assays, and short green line indicates DNA probe used for EMSA. The translational start site (ATG) is shown at position +1. (E) Chromatin immunoprecipitated with anti-ABAP1 antibody was analyzed by qPCR using gene-specific primer sets, numbered as indicated in (D). The graph shows the fold enrichment of qPCR amplified regions at the promoter (1), coding region (2) and 3′UTR (3,4) of EDA24-like. The fold enrichment of each amplified region was calculated as a ratio between IP ABAP1OE and IP WT of values normalized with values of the ACTIN 2 promoter. Error bars represent the SD of three biological replicates. Asterisk (∗) indicates significant difference from the enrichment according to Student’s t-test (p-value < 0.05). IP, immunoprecipitated with anti-ABAP1 antibody.

Remarkably, an AP2-type transcription factor that interacts with ABAP1 was identified in a two-hybrid screen using ABAP1 as bait (Figure 6A). This gene was previously identified as ADAP [ARIA-interacting double AP2-domain protein/WRINKLED3 (WRI3)], involved in seedling growth, ABA responses and in the regulation of the fatty acid biosynthetic pathway (Lee et al., 2009; To et al., 2012). For simplification, this gene will be referred to as ADAP from now on in this document. Interestingly, ADAP is an interactor of ARIA, the only ABAP1 homolog in Arabidopsis, and is also expressed in synergids, egg cell and central cell, according to data publicly available from microarray experiments (Wuest et al., 2010), supporting that ADAP and ABAP1 might co-localize and interact during embryo sac differentiation. We thus investigated whether ADAP also plays a role in gametogenesis, especially regulating EDA24-like expression. The interaction between ABAP1 and ADAP was further confirmed by a GST-pull down assay with ADAP–HIS and ABAP1-GST (Figure 6B) and in a semi in vivo HIS-pull down experiment, where His-fused ADAP were added to Arabidopsis protein extract and used in nickel column purification (Supplementary Figure 4A). In the GST pull down, ADAP associated with ABAP1–GST (Figure 6B, lane 1) but not to GST alone (Figure 6B, lane 2). The ability of ADAP-ABAP1 complex to recognize EDA24-like promoter and regulate its expression was first investigated in an EMSA performed with a probe containing the AW-box of the EDA24-like promoter region (Supplementary Information). ADAP alone and ADAP–ABAP1 associated with the wild-type probes (Figure 6C, lanes 1 and 2) but ADAP alone did not associate with the mutated probe (Figure 6C, lane 5). ABAP1 alone or GST did not associate with ADAP consensus motif probe (Figure 6C, lanes 3 and 4). The association of ABAP1-ADAP complex with EDA24-like promoter was also confirmed in vivo in ChIP- PCR experiments with anti-ABAP1 antibody (Supplementary Figure 5C2 and Figure 6D), using chromatin extracts from Arabidopsis ABAP1OE and wild-type flower buds. ABAP1-ADAP interaction was detected in the EDA24-like promoter of wild-type plants (Supplementary Figure 5C2, lane 3). Next, four different primer sets were designed to amplify regions along the EDA24-like promoter, coding sequence and 3’UTR regions. Primer set number one was specifically designed to amplify a region that harbors both the AINTEGUMENTA and the AW-box motifs (Figure 6D) in the promoter region of EDA24-like gene. The results showed that ABAP1 associated with the region of the EDA24-like promoter that contains the AW-box in wild-type flower buds and that this association was enhanced in ABAP1OE (Figure 6E).

The data suggests that ABAP1 associates with ADAP in flowers, and the ABAP1-ADAP complex negatively regulates EDA24-like expression, controlling the polar nuclei fusion during maturation of the female gametophyte. Similar effects on central cells’ formation were observed in ABAP1OE and eda24-likeKD plants, supporting this model of action of ABAP1 during female gametogenesis.

Discussion

During higher plants’ life cycle, the diploid sporophyte body and the haploid gametophytes establish unique strategies to modulate their development. It implies that they might have evolved particular mechanisms to connect the cell cycle progression with developmental and environmental signals. ABAP1 is a plant specific protein that has been previously implicated in the control of cell proliferation homeostasis during vegetative leaf development (Masuda et al., 2008). Here, we characterized plants with up-regulated levels of ABAP1, and studied ABAP1’s association with different transcription factors, repressing the expression of their target genes during plant reproduction. We propose novel regulatory mechanisms in which ABAP1 is involved, by fine-tuning (i) formative cell division in male gametophyte and (ii) cell differentiation (or cell fusion) in female gametophyte, two processes that are essential for a successful plant reproduction in Arabidopsis.

ABAP1 Participates in the Regulation of the Formative Cell Division During Differentiation of Male Gametophyte

During the formation of the male gametophyte in flowering plants, the haploid microspore generated after meiosis undergoes two rounds of mitotic divisions in order to form the mature male gametophyte. The first asymmetric mitotic division (Pollen Mitosis I, PMI) results in a large vegetative cell and a small generative cell which undergoes a second symmetric cell division yielding the two sperm cells (Twell, 2011).

The successful progression of pollen development requires the function of genes specifically active in the haploid gametophyte, as well as of genes involved in both gametophyte and sporophyte development (Brownfield et al., 2009). There are already a number of genes described as affecting various aspects of pollen development in Arabidopsis. Out of those mutants, some male gametophyte mutations affecting PMI and PMII have been characterized, such as sidecar pollen, duo1 (duo pollen1), duo2 (duo pollen2), gem1 (gemini pollen1), and gem2 (gemini pollen2) [reviewed in Liu and Qu (2008)].

Some cell cycle regulators of diploid sporophyte have also been shown to control male gametogenesis. The smaller generative cell formed during PMI asymmetric division is further engulfed by the large vegetative cell, a process that requires the presence of the plant retinoblastoma homolog RBR1. Pollen with multiple vegetative cells are formed in rbr1 mutants (Chen et al., 2009). The CDKA;1 activity is also of key importance for PMII. The cdka;1 mutant pollen develops a vegetative cell similar to the wild-type, but with only one generative/sperm cell-like (Nowack et al., 2006). A similar phenotype was also observed in mutants of the F-BOX-LIKE 17 (FBL17) gene, that acts together with SKP-CULLIN-F-BOX (SCF) complex mediating the degradation of KRP6 and KRP7 (Gusti et al., 2009). However, a detailed molecular genetic framework of cell-cycle control over male gametophyte development is still missing in plants.

Besides regulating the balance of proliferative mitotic divisions during vegetative growth, our data suggest a novel role of ABAP1 in formative cell division during male gametophyte development. Here we have shown that ABAP1, having TCP16 as its partner, negatively regulates CDT1b transcription, possibly affecting pre-RC assembly, consequently DNA replication and cell division. We showed that PMI was affected in cdt1bKD mutants (Figure 3A, bottom line), similarly as in ABAP1OE plants. CDT1a and CDT1b were previously shown to have partially redundant functions during male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis, however, the function of CDT1b alone was not investigated (Domenichini et al., 2012). Moreover, only CDT1a had a role in the female gametophyte development, since cdt1a mutants showed defects occurring in the mitosis during embryo sac maturation (Domenichini et al., 2012). Remarkably, we found that ABAP1 associated only with the CDT1b but not with the CDT1a promoter in Arabidopsis flower buds (Supplementary Figure 5), indicating that ABAP1 regulates female gametophyte development in a mechanism that does not involve repression of CDT1a expression, as discussed below.

The data indicates that ABAP1 acts during male gametogenesis in a similar way to those previously described in leaves, as it also involves repression of CDT1b expression. Nevertheless, in this different developmental context, the TCP partner, a member of class I TCP transcription factors, seems to be negatively regulating cell cycle progression of the male gametophyte (Li et al., 2012; Aguilar-Martínez and Sinha, 2013). Acting as a negative regulator of mitotic cell cycle progression, ABAP1 possibly integrates the timing of the male gametophyte differentiation with developmental cues.

ABAP1 Has a Role in the Female Gametogenesis Differentiation

In most angiosperm species, including Arabidopsis, after meiosis the female gametophyte undergoes three rounds of mitosis followed by cellularizations to produce a seven-celled embryo sac consisting of one egg cell, two synergids, three antipodal cells, and one diploid central cell. In Arabidopsis and other species, the polar nuclei fuse before pollination to form the secondary nucleus of the central cell. Although increasing knowledge about female gametophyte development has been revealed, little is known about polar nuclei fusion. Here, we showed that plants with high levels of ABAP1 yielded mature ovules with unfused polar nuclei due to EDA24-like repression mediated by ABAP1-ADAP binding to its promoter sequence.

ADAP is a member of the AP2/ERF family of transcription factors and belongs to basal AINTEGUMENTA (ANT) being related to WRINKLED, rather than to ANT, PLETHORA, AIL, and BABY BOOM (Horstman et al., 2014). It binds to ARIA, the only ABAP1 homolog in Arabidopsis and a ABF2-interacting partner that controls ABA response possibly by the same pathway of ABF2 (Lee et al., 2009). Interestingly, ADAP overexpressing lines had fewer and shorter siliques with fewer ovules, a phenotype similar to what was observed in ABAP1OE plants. Analogous to what was proposed for ABAP1-TCP24 interaction, in which the heterodimer downregulates TCP24 target genes (Masuda et al., 2008), our data points to a similar molecular mechanism with ABAP1-ADAP heterodimer repressing ADAP target genes, in this case EDA24-like. Downregulation of EDA24-like expression observed in both ABAP1OE plants and eda24-likeKD knockdown mutants led to the failure of the polar nuclei fusion to form the central cell from FG5 to FG7. This phenotype is similar to the one reported for eda24 mutants, in which female gametophyte is arrested at two polar nuclei phase (Pagnussat et al., 2005).

Several mutants of cell cycle genes have been described to impair female gametogenesis, such as members of APC/C (Capron et al., 2003; Kwee and Sundaresan, 2003; Pérez-Pérez et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2012, 2013), cyclin/CDK pathway (Nowack et al., 2006; Takatsuka et al., 2015) and G1/S transition genes like RBR1 and pre-replication complex genes (Holding and Springer, 2002; Ebel et al., 2004; Domenichini et al., 2012). The phenotypes observed in these mutants are usually related to cell division or polarity defects rather than to failure in polar nuclei fusion or DNA replication.

Failure in polar nuclei fusion was already described in several other mutants whose molecular function is involved in fatty acid metabolism, RNA metabolism, endomembrane system, mitochondrial metabolism and cytokinin signaling pathway (for review, see Maruyama et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017). Other mutants were also described (eda24 to eda41) but their molecular function is still uncharacterized (Pagnussat et al., 2005). EDA24 is a member of the plant invertase/pectin methylesterase inhibitor superfamily whose function in polar nuclei fusion still remains to be elucidated. Since EDA24 and EDA24-like are both invertase/pectin methylesterase inhibitors, it is possible that pectin metabolism is important during nuclei fusion.

Interestingly, none of the mutant genes defective in polar nuclei fusion described so far were involved in DNA replication control. In A. thaliana, it was suggested that the fusion of the male and female chromatin requires both nuclei to be at the same stage of the cell cycle, which occurs at G2/M phase. Since central cell chromatin seems to be at the G2/M transition, it is tempting to speculate whether the fusion of the two polar nuclei also requires the concurrence of ploidy levels, and a passage through S phase (Friedman, 1999; Faure et al., 2002; Berger et al., 2008; Ronceret et al., 2008). ABAP1 has been shown to play a role in S-phase progression in cell proliferation during leaf development (Masuda et al., 2008). Here, we also report a similar mechanism occurring in ABAP1OE plants, in which ABAP1 represses CDT1b transcription, possibly arresting the unicellular pollen at G1/S. Unfortunately, information about ploidy level of female gametophyte cells is still missing. If the polar nuclei have to be at G2/M to form the central cell, then, nuclei arrested at G1/S could partially explain the defect observed in ABAP1OE.

ABAP1 Is Involved in Mechanisms That Regulate Differentiation of Both Male and Female Gametophytes

The underlying molecular and biochemical mechanisms coordinating the complete fertilization process in flowering seed plants (angiosperms) are recently being studied and revealed. During self-fertilization in compatible conditions, an intriguing issue is how the differentiation of the two female gametes (egg and central cells) and the two male sperm cells are coordinated, since these two events must be synchronized in different plant organs to allow a timely double fertilization.

Our data revealed that ABAP1 is involved in mechanisms that regulate differentiation of both male and female gametophytes, as the up-regulation of ABAP1 levels arrested male gametogenesis at the first gametophyte cell division and prevented fusion of the two polar nuclei in the central cell. An interesting question to be addressed is whether ABAP1 could participate in mechanisms that coordinate the timing of the gametophyte differentiation. The transcriptional regulators RBR1/E2Fa play a dual role in male and female gametogenesis by controlling the cell-cycle progression in both gametophytes. RBR1/E2Fa directly regulates the F-box protein FBL17, in a negative regulatory cascade where FBL17 inhibits CDKA;1 (Desvoyes et al., 2014). Accordingly, concomitant loss of CDKA;1 and FBL17 resulted in female and male gametophytes with defects in the mitosis post-meiosis (Zhao et al., 2012).

As male gametophyte differentiates in vegetative and sperm cells and the seven-celled female gametophyte is formed, the two sperm cells have to be guided toward the two female gametes. Great advances have recently been made in the understanding of the regulation of pollen tube guidance toward the two female gametes. The synergid cells and the egg cell of the seven-celled female gametophyte communicate with each other to establish and maintain their identity (reviewed in Skinner and Sundaresan, 2018). These four cell types have also been shown to generate and secrete signaling molecules, such as multiple peptides and especially small Cys-rich proteins, that are sensed by receptor-like kinases in a mechanism involved in guiding the male gametophyte (reviewed in Higashiyama and Yang, 2017). The central cell was also implicated in playing a role in pollen tube guidance since mutants for a gene expressed in these cells, named the CCG, are defective in pollen tube attraction (Chen et al., 2007). As ABAP1OE female gametophytes did not form a one-nucleus central cell, ABAP1 might be involved in regulating this step of female gamete differentiation. Defects in pollen tube attraction and reception as well as zygote activation could also be occurring in ABAP1OE plants but were not addressed on this work.

After the sperm cell discharge, gamete fusion of the male and female chromatins (karyogamy) might require a cell cycle synchronization. In Arabidopsis, it has been suggested that the karyogamy occurs with nuclei at G2/M phase. At the end of pollen maturation, the two male sperm cells seem to reinitiate the S phase, progressing into the cell cycle until being arrested at the G2/M transition (Durbarry et al., 2005). For the female gametes, it has been proposed that the central cell arrests at the G2/M transition, whereas the egg cell arrests at the G1/S transition and has to progress into the cell cycle prior to gamete fusion, as the first zygote mitosis happens 16 h after fertilization and requires transcription of the thymidylate kinase at the G1/S transition (Faure et al., 2002; Berger et al., 2008; Ronceret et al., 2008). As discussed above, it is tempting to speculate that ABAP1, as a DNA replication repressor (Masuda et al., 2008), could be participating in a mechanism that controls the timing of the last steps of male and female gametes maturation, by regulating S phase progression, as coordination of cell cycle synchronization is necessary for karyogamy and polar nuclei fusion.

The different effects of ABAP1 de-regulation on gametophyte development are intriguing. We have shown that specific ABAP1 transcription factor partners might account, at least in part, for the different phenotypic outcomes of the male and female gametophytes. Although our data show effects of ABAP1 imbalance in the gametogenesis, we cannot rule out possible effects of ABAP1 in sporophytic tissues that might indirectly affect gametophyte development. Interestingly, down regulation of ABAP1 did not affect gametogenesis. This could result from the accumulation of maternally inherited ABAP1 protein. Otherwise, since ABAP1 is a repressor of the basic machinery that licenses DNA to replicate, it works by regulating the rate at which the cell cycle progresses into G1/S phase, being possibly a sensor of internal and external conditions. Thus, another possibility is that ABAP1 is only necessary to prevent and/or slow down gametophyte development in specific environmental conditions.

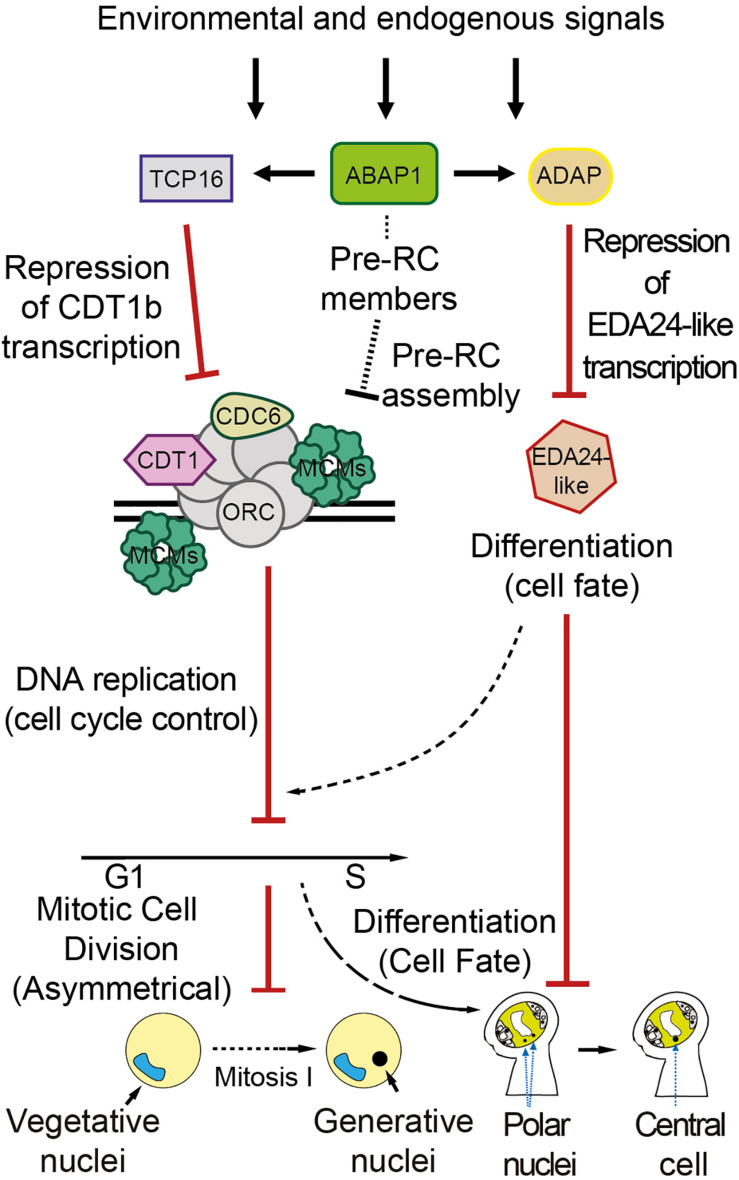

In this work, we have determined the molecular and biochemical mechanisms by which ABAP1 is involved in the regulation of male and female gametogenesis, which comprise binding to different transcription factors and controlling their gene expression targets (Figure 7). It remains to be determined whether ABAP1 might also participate in a mechanism that regulates the timing of male and female gametophytes differentiation in Arabidopsis, integrating it with environmental and internal signaling, to ensure the reliable and on-time fusion of the two pairs of gametes. The double-fertilization has countless biological and agricultural implications and mechanisms that guarantee a successful double fertilization might provide selective advantage for plants. Also, effective plant fertilization is essential for an efficient seed production, thus molecular understanding of the mechanisms involved in controlling double fertilization could provide tools to improve plant yield.

FIGURE 7.

Proposed model for ABAP1 role in the differentiation of male and female gametophytes. ABAP1, associated with transcription factors partners, might sense environmental and endogenous signals, triggering changes in gene expression patterns that will regulate male and female gametophytes differentiation. The molecular mechanism operating in the male gametophyte is similar to those previously described in leaves. In the first asymmetric cell division after meiosis, ABAP1 associates with TCP16, represses CDT1b transcription, controlling CDT1b homoeostasis. Lower levels of CDT1b might affect pre-RC functioning, limiting DNA replication. A direct association of ABAP1 with pre-RC members is still not determined. However, as described in leaves, it could also affect pre-RC assembly and DNA replication in the male gametophyte. In this way ABAP1 would regulate the timing of cell cycle progression at G1 to S. The mechanism of action in the female gametophyte involves association with another partner, ADAP, during embryo sac maturation. ABAP1-ADAP also represses gene transcription of EDA24-like that is necessary for polar nuclei fusion. Thus, ABAP1 might regulate the timing of polar nuclei fusion to form the central cell, that is crucial in pollen tube guidance. The involvement of DNA replication in the mechanism that regulates female differentiation is still not determined.

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data from this article can be found at the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative database with the following accession numbers: ABAP1 (At5g13060), Actin 2 (At3g18780), UBQ14 (AT4G02890), CDT1a (At2g31270), CDT1b (At3g54710), TCP16 (AT3G45150), EDA24-like (At1g23350), and ADAP/WRI3 (At1g16060). Microarray data was deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (nos. GEO: GSE164480 and GSM5011985).

Author Contributions

LC and HM performed the molecular and cellular studies. HB and JA-E performed immunolocalization studies. MA-F carried out the microarray experiments. HM and FB performed the in silico analyses. LC carried out the biochemical assays. LC, HM, and AH designed the work and analyzed the data. PF and KD participated in the analyses and discussion of results. LM, HM, and AH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to COFECUB and Centro Brasil-Argentina de Biotecnologia (CBAB) for technical training and to Andre Ferreira for language editing.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES/COFECUB SV.622/18), and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico. LC was supported by Ph.D. and postdoctoral fellowships from CNPq. HM and FB were supported with graduate fellowships from CAPES (Finance Code – 001). HB was supported with a postdoc CAPES/COFECUB fellowship. HM received a grant from FAPESP (2009/53195-8). AH and PF receive support from a CNPq research grant.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.642758/full#supplementary-material

ABAP1 localization during male gametogenesis in WT plants.

ABAP1 localization in pollen and ovary of WT and ABAP1OE plants.

Anther and male gametophyte development in ABAP1OE flowers.

Semi in vivo interaction between ABAP1, TCP16, and ADAP and schematic representation of the genomic T-DNA insertions and gene expression in cdt1bKD and eda24-likeKD mutant lines.

Characterization of the interaction between ABAP1-TCP16 with the promoters of CDT1a and CDT1b.

Differentially expressed genes in ABAP1OE flowers, analyzed by microarray.

Gene Ontology (GO) term network analysis of down regulated genes in ABAP1OE array based on biological processes, molecular function and cellular component.

List of genes differentially regulated in flower buds of stage 13 of ABAP1OE plants, compared to wild-type control (Col-0).

Description of detailed experimental procedures.

References

- Aguilar-Martínez J. A., Sinha N. (2013). Analysis of the role of Arabidopsis class I TCP genes AtTCP7, AtTCP8, AtTCP22, and AtTCP23 in leaf development. Front. Plant Sci. 4:406. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bemer M., Wolters-Arts M., Grossniklaus U., Angenent G. C. (2008). The MADS domain protein DIANA acts together with AGAMOUS-LIKE80 to specify the central cell in Arabidopsis ovules. Plant Cell 20 2088–2101. 10.1105/tpc.108.058958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berckmans B., De Veylder L. (2009). Transcriptional control of the cell cycle. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12 599–605. 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger F., Hamamura Y., Ingouff M., Higashiyama T. (2008). Double fertilization–caught in the act. Trends Plant Sci. 13 437–443. 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg M., Twell D. (2010). Life after meiosis: patterning the angiosperm male gametophyte. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38 577–582. 10.1042/BST0380577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownfield L., Hafidh S., Borg M., Sidorova A., Mori T., Twell D. (2009). A plant germline-specific integrator of sperm specification and cell cycle progression. PLoS Genet 5:e1000430. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capron A., Serralbo O., Fülöp K., Frugier F., Parmentier Y., Dong A., et al. (2003). The Arabidopsis anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome: molecular and genetic characterization of the APC2 subunit. Plant Cell 15 2370–2382. 10.1105/tpc.013847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekanova J. A., Shaw R. J., Wills M. A., Belostotsky D. A. (2000). Poly(A) tail-dependent exonuclease AtRrp41p from Arabidopsis thaliana rescues 5.8 S rRNA processing and mRNA decay defects of the yeast ski6 mutant and is found in an exosome-sized complex in plant and yeast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275 33158–33166. 10.1074/jbc.M005493200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-H., Li H.-J., Shi D.-Q., Yuan L., Liu J., Sreenivasan R., et al. (2007). The central cell plays a critical role in pollen tube guidance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19 3563–3577. 10.1105/tpc.107.053967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Hafidh S., Poh S. H., Twell D., Berger F. (2009). Proliferation and cell fate establishment during Arabidopsis male gametogenesis depends on the Retinoblastoma protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 7257–7262. 10.1073/pnas.0810992106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen C. A., King E. J., Jordan J. R., Drews G. N. (1997). Megagametogenesis in Arabidopsis wild type and the Gf mutant. Sex. Plant Reprod. 10 49–64. 10.1007/s004970050067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collinge M. A., Spillane C., Köhler C., Gheyselinck J., Grossniklaus U. (2004). Genetic interaction of an origin recognition complex subunit and the polycomb group gene MEDEA during seed development. Plant Cell 16 1035–1046. 10.1105/tpc.019059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Ramírez A., Díaz-Triviño S., Blilou I., Grieneisen V. A., Sozzani R., Zamioudis C., et al. (2012). A bistable circuit involving SCARECROW-RETINOBLASTOMA integrates cues to inform asymmetric stem cell division. Cell 150 1002–1015. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida Engler J., De Groodt R., Van Montagu M., Engler G. (2001). In situ hybridization to mRNA of Arabidopsis tissue sections. Methods 23 325–334. 10.1006/meth.2000.1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet I., Beeckman T. (2011). Asymmetric cell division in land plants and algae: the driving force for differentiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12 177–188. 10.1038/nrm3064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvoyes B., de Mendoza A., Ruiz-Trillo I., Gutierrez C. (2014). Novel roles of plant RETINOBLASTOMA-RELATED (RBR) protein in cell proliferation and asymmetric cell division. J. Exp. Bot. 65 2657–2666. 10.1093/jxb/ert411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvoyes B., Ramirez-Parra E., Xie Q., Chua N. H., Gutierrez C. (2006). Cell type-specific role of the retinoblastoma/E2F pathway during Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant Physiol. 140 67–80. 10.1104/pp.105.071027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenichini S., Benhamed M., Jaeger G. D., Slijke E. V. D., Blanchet S., Bourge M., et al. (2012). Evidence for a role of Arabidopsis CDT1 proteins in gametophyte development and maintenance of genome integrity. Plant Cell 24 2779–2791. 10.1105/tpc.112.100156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews G. N., Koltunow A. M. G. (2011). The fnemale gametophyte. Arab. Book 9 e0155–e0155. 10.1199/tab.0155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbarry A., Vizir I., Twell D. (2005). Male germ line development in Arabidopsis. duo pollen mutants reveal gametophytic regulators of generative cell cycle progression. Plant Physiol. 137 297–307. 10.1104/pp.104.053165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebel C., Mariconti L., Gruissem W. (2004). Plant retinoblastoma homologues control nuclear proliferation in the female gametophyte. Nature 429 776–780. 10.1038/nature02637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure J.-E., Rotman N., Fortuné P., Dumas C. (2002). Fertilization in Arabidopsis thaliana wild type: developmental stages and time course. Plant J. 30 481–488. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01305.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman W. E. (1999). Expression of the cell cycle in sperm of Arabidopsis: implications for understanding patterns of gametogenesis and fertilization in plants and other eukaryotes. Development 126 1065–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendrel A.-V., Lippman Z., Martienssen R., Colot V. (2005). Profiling histone modification patterns in plants using genomic tiling microarrays. Nat. Methods 2:213. 10.1038/nmeth0305-213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusti A., Baumberger N., Nowack M., Pusch S., Eisler H., Potuschak T., et al. (2009). The Arabidopsis thaliana F-box protein FBL17 is essential for progression through the second mitosis during pollen development. PLoS One 4:e4780. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harashima H., Schnittger A. (2010). The integration of cell division, growth and differentiation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13 66–74. 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harashima H., Sugimoto K. (2016). Integration of developmental and environmental signals into cell proliferation and differentiation through RETINOBLASTOMA-RELATED 1. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 29 95–103. 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashiyama T., Yang W. (2017). Gametophytic pollen tube guidance: attractant peptides, gametic controls, and receptors. Plant Physiol. 173 112–121. 10.1104/pp.16.01571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holding D. R., Springer P. S. (2002). The Arabidopsis gene PROLIFERA is required for proper cytokinesis during seed development. Planta 214 373–382. 10.1007/s00425-001-0686-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstman A., Willemsen V., Boutilier K., Heidstra R. (2014). AINTEGUMENTA-LIKE proteins: hubs in a plethora of networks. Trends Plant Sci. 19 146–157. 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajala K., Ramakrishna P., Fisher A., Bergmann D. C., De Smet I., Sozzani R., et al. (2014). Omics and modelling approaches for understanding regulation of asymmetric cell divisions in Arabidopsis and other angiosperm plants. Ann. Bot. 113 1083–1105. 10.1093/aob/mcu065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwee H. S., Sundaresan V. (2003). The Nomega gene required for female gametophyte development encodes the putative APC6/CDC16 component of the anaphase promoting complex in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 36 853–866. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01925.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. J., Cho D. I., Kang J. Y., Kim S. Y. (2009). An ARIA-interacting AP2 domain protein is a novel component of ABA signaling. Mol. Cells 27 409–416. 10.1007/s10059-009-0058-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Li B., Shen W. H., Huang H., Dong A. (2012). TCP transcription factors interact with AS2 in the repression of class-I KNOX genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 71 99–107. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04973.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Qu L.-J. (2008). Meiotic and mitotic cell cycle mutants involved in gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 1 564–574. 10.1093/mp/ssn033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Yuan L., Song X., Yu X., Sundaresan V. (2017). AHP2, AHP3, and AHP5 act downstream of CKI1 in Arabidopsis female gametophyte development. J. Exp. Bot. 68 3365–3373. 10.1093/jxb/erx181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logemann J., Schell J., Willmitzer L. (1987). Improved method for the isolation of RNA from plant tissues. Anal. Biochem. 163 16–20. 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90086-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeo K., Tokuda T., Ayame A., Mitsui N., Kawai T., Tsukagoshi H., et al. (2009). An AP2-type transcription factor, WRINKLED1, of Arabidopsis thaliana binds to the AW-box sequence conserved among proximal upstream regions of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis. Plant J. 60 476–487. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03967.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama D., Ohtsu M., Higashiyama T. (2016). Cell fusion and nuclear fusion in plants. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 60 127–135. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H. P., Cabral L. M., De Veylder L., Tanurdzic M., de Almeida Engler J., Geelen D., et al. (2008). ABAP1 is a novel plant Armadillo BTB protein involved in DNA replication and transcription. EMBO J. 27 2746–2756. 10.1038/emboj.2008.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H. P., Ramos G. B. A., De Almeida-Engler J., Cabral L. M., Coqueiro V. M., Macrini C. M. T., et al. (2004). Genome based identification and analysis of the pre-replicative complex of Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 574 192–202. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nole-Wilson S., Krizek B. A. (2000). DNA binding properties of the Arabidopsis floral development protein AINTEGUMENTA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 4076–4082. 10.1093/nar/28.21.4076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowack M. K., Grini P. E., Jakoby M. J., Lafos M., Koncz C., Schnittger A. (2006). A positive signal from the fertilization of the egg cell sets off endosperm proliferation in angiosperm embryogenesis. Nat. Genet. 38 63–67. 10.1038/ng1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnussat G. C., Yu H.-J., Ngo Q. A., Rajani S., Mayalagu S., Johnson C. S., et al. (2005). Genetic and molecular identification of genes required for female gametophyte development and function in Arabidopsis. Development 132 603–614. 10.1242/dev.01595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. A., Ahn J. W., Kim Y. K., Kim S. J., Kim J. K., Kim W. T., et al. (2005) Retinoblastoma protein regulates cell proliferation, differentiation, and endoreduplication in plants. Plant J. 42 153–163. 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2005.02361.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pérez J. M., Serralbo O., Vanstraelen M., González C., Criqui M. C., Genschik P., et al. (2008). Specialization of CDC27 function in the Arabidopsis thaliana anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C). Plant J. 53 78–89. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plackett A. R. G., Thomas S. G., Wilson Z. A., Hedden P. (2011). Gibberellin control of stamen development: a fertile field. Trends Plant Sci. 16 568–578. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portereiko M. F., Lloyd A., Steffen J. G., Punwani J. A., Otsuga D., Drews G. N. (2006a). AGL80 Is required for central cell and endosperm development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18 1862–1872. 10.1105/tpc.106.040824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portereiko M. F., Sandaklie-Nikolova L., Lloyd A., Dever C. A., Otsuga D., Drews G. N. (2006b). NUCLEAR FUSION DEFECTIVE1 encodes the Arabidopsis RPL21M protein and is required for karyogamy during female gametophyte development and fertilization. Plant Physiol. 141 957–965. 10.1104/pp.106.079319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen C. G., Humphries J. A., Smith L. G. (2011). Determination of symmetric and asymmetric division planes in plant cells. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62 387–409. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronceret A., Gadea−Vacas J., Guilleminot J., Lincker F., Delorme V., Lahmy S., et al. (2008). The first zygotic division in Arabidopsis requires de novo transcription of thymidylate kinase. Plant J. 53 776–789. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03372.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sablowski R., Carnier Dornelas M. (2014). Interplay between cell growth and cell cycle in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 65 2703–2714. 10.1093/jxb/ert354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders P. M., Bui A. Q., Weterings K., McIntire K. N., Hsu Y.-C., Lee P. Y., et al. (1999). Anther developmental defects in Arabidopsis thaliana male-sterile mutants. Sex. Plant Reprod. 11 297–322. 10.1007/s004970050158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]