ABSTRACT

The hexanucleotide G4C2 repeat expansion in the first intron of the C9ORF72 gene accounts for the majority of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) cases. Numerous studies have indicated the toxicity of dipeptide repeats (DPRs), which are produced via repeat-associated non-AUG (RAN) translation from the repeat expansion, and accumulate in the brain of C9FTD/ALS patients. Mouse models expressing the human C9ORF72 repeat and/or DPRs show variable pathological, functional and behavioral characteristics of FTD and ALS. Here, we report a new Tet-on inducible mouse model that expresses 36× pure G4C2 repeats with 100-bp upstream and downstream human flanking regions. Brain-specific expression causes the formation of sporadic sense DPRs aggregates upon 6 months of dox induction, but no apparent neurodegeneration. Expression in the rest of the body evokes abundant sense DPRs in multiple organs, leading to weight loss, neuromuscular junction disruption, myopathy and a locomotor phenotype within the time frame of 4 weeks. We did not observe any RNA foci or pTDP-43 pathology. Accumulation of DPRs and the myopathy phenotype could be prevented when 36× G4C2 repeat expression was stopped after 1 week. After 2 weeks of expression, the phenotype could not be reversed, even though DPR levels were reduced. In conclusion, expression of 36× pure G4C2 repeats including 100-bp human flanking regions is sufficient for RAN translation of sense DPRs, and evokes a functional locomotor phenotype. Our inducible mouse model suggests that early diagnosis and treatment are important for C9FTD/ALS patients.

This article has an associated First Person interview with the first author of the paper.

KEY WORDS: C9ORF72, ALS, FTD, Mouse, Inducible, DPRs

Summary: Only 36 C9ORF72 repeats are sufficient for RAN translation in a new mouse model for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Reducing toxic dipeptides can prevent but not reverse the phenotype.

INTRODUCTION

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a neurological disease characterized by neuronal loss in the frontal and temporal lobes, leading to behavioral and personality changes, and language deficits (Hernandez et al., 2018; Woollacott and Rohrer, 2016). The prevalence of FTD is ∼15-20 cases per 100,000 people, and the age of onset is usually between 45 to 65 years (Woollacott and Rohrer, 2016). FTD is part of a disease spectrum that also comprises amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Couratier et al., 2017; Strong et al., 2017). ALS is a rapid progressive motor neuron disorder that affects the upper motor neurons in the motor cortex and the lower motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord (Grad et al., 2017; Oskarsson et al., 2018). ALS patients develop muscle weakness, spasticity, atrophy and eventually paralysis (Grad et al., 2017; Oskarsson et al., 2018). The prevalence of ALS is ∼5 in 100,000 people, and the age of onset is between 50 and 60 years of age (Grad et al., 2017; Oskarsson et al., 2018). The hexanucleotide G4C2 repeat expansion in the C9ORF72 gene accounts for almost 90% of the families presenting with both FTD and ALS symptoms (referred to as C9FTD/ALS; DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Renton et al., 2011). Patients can be mosaic for repeat size and often have longer repeats in brain tissue than in DNA isolated from blood samples (Fournier et al., 2019; Nordin et al., 2015; van Blitterswijk et al., 2013). So far, repeat sizes of 24-4400 have been reported (Iacoangeli et al., 2019; Van Mossevelde et al., 2017). Associations between repeat size and clinical diagnosis have not resulted in a clear picture (Fournier et al., 2019; Gijselinck et al., 2016; van Blitterswijk et al., 2013). Thus, the exact repeat size that triggers disease onset is not known.

Three mechanisms for the C9ORF72 repeat expansion have been proposed to cause C9FTD/ALS (Balendra and Isaacs, 2018). First, hypermethylation of the repeat and surrounding CpG islands can lead to reduced levels of the normal C9ORF72 protein (Belzil et al., 2013; Waite et al., 2014). C9orf72 knockout mice have shown its essential function in immunity, but do not present with FTD or ALS symptoms (Balendra and Isaacs, 2018). However, haploinsufficiency can still modify the effects of gain-of-function mechanisms via the normal cellular function of the C9ORF72 protein in autophagy and lysosomal biogenesis (Sellier et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2018). Second, repeat-containing RNA from both sense and antisense directions can form secondary structures (Kovanda et al., 2015; Su et al., 2014) and RNA foci (Gendron et al., 2013; Mizielinska et al., 2013). Repeat-containing RNA or RNA foci can sequester RNA-binding proteins and prevent their normal functioning in the cell (Haeusler et al., 2016). Third, the G4C2 repeat can also be translated into dipeptide repeats (DPRs) via repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation (Ash et al., 2013; Gendron et al., 2013; Mori et al., 2013). RAN translation occurs in all reading frames of sense and antisense transcripts and results in the formation of poly-glycine-alanine (GA), poly-glycine-proline (GP), poly-glycine-arginine (GR), poly-proline-alanine (PA) and poly-proline-arginine (PR). DPRs have been found throughout the brains of C9FTD/ALS patients (Mackenzie et al., 2015) and poly-GR has particularly been associated with neurodegeneration (Gittings et al., 2020; Saberi et al., 2018; Sakae et al., 2018). Multiple cell and animal models have indicated the detrimental effect of the expression of both arginine-containing DPRs, poly-GR and poly-PR, and the slightly less toxic poly-GA (Balendra and Isaacs, 2018; Boeynaems et al., 2016; Jovicic et al., 2015; Kanekura et al., 2016; Kwon et al., 2014; Mizielinska et al., 2014; Swaminathan et al., 2018; Tao et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2014; Yamakawa et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2015). So far, 11 loss-of-function and ten gain-of-function C9ORF72 mouse models have been published (reviewed by Balendra and Isaacs, 2018; Batra and Lee, 2017), as well as five DPR-only mouse models investigating the role of poly-GA (Schludi et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016), poly-GR (Zhang et al., 2018) and poly-PR (Hao et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). All mouse models support a gain-of-function hypothesis in C9FTD/ALS, although not all BAC mice show neurodegeneration or a motor phenotype associated with ALS (reviewed by Balendra and Isaacs, 2018; Batra and Lee, 2017). The effect of DPRs has been studied extensively (reviewed by Balendra and Isaacs, 2018), but possible reversibility and the exact number of repeats needed for RAN translation in vivo have yet to be determined (Cleary et al., 2018; Green et al., 2016).

Here, we describe a new mouse model that expresses human C9ORF72 36× pure G4C2 repeats with 100-bp upstream and downstream human flanking regions under the expression of an inducible Tet-on promoter. This system allows for temporal and spatial expression of the repeat expansion. Expression of 36× pure G4C2 repeats was sufficient to produce sense DPRs and a locomotor phenotype upon 4 weeks of induction of expression. In order to study possible reversibility, expression was stopped after 1 or 2 weeks, followed by a washout period of 2-3 weeks to prevent further build-up and subsequent reduction of the amount of DPRs.

RESULTS

Generation and expression pattern of the human 36× G4C2 repeat mouse model

We generated our mouse model from DNA isolated from the blood of a C9FTD patient and amplified the repeat in three consecutive PCR rounds using primers that flanked the C9ORF72 repeat expansion (for primer sequences see Materials and Methods). The PCR product was cloned into a TOPO vector and subsequently into a Tet-on vector with a GFP reporter gene (Hukema et al., 2014) (Fig. 1A). Sequencing of this construct revealed a repeat size of 36× pure G4C2 repeats with 118-bp upstream and 115-bp downstream human flanking regions (Fig. S1). The transgene (containing the TRE promoter, 36× G4C2 repeats and the GFP gene) was injected into pronuclei of C57BL/6J mice. Founder mice were screened for the presence and size of the transgene and transmission to their offspring (n=3 lines containing the repeat, 1 line with expression). Genotyping for transgene presence was performed with primers located upstream of the repeat. Repeat size estimation was established using the Asuragen C9ORF72 repeat kit that is also used in routine human diagnostics. Repeat size remained stable between generations and between multiple organs of the same mouse (Fig. 1B). Transgenic mice were born at Mendelian frequencies and showed normal viability.

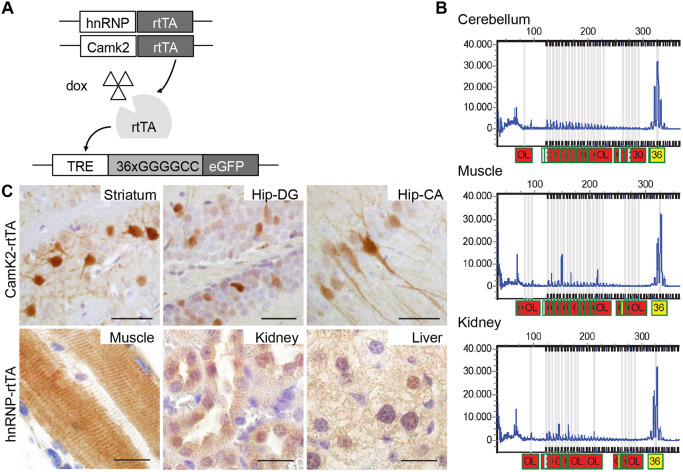

Fig. 1.

Generation and expression of the 36× G4C2 repeat mouse model. (A) Schematic of the Tet-on system. Mice either have a Camk2-alpha-rtTA or hnRNP-rtTA transgene that expresses rtTA in a brain-specific manner or in the whole body. Upon binding of dox, rtTA can bind the TRE response element and start transcription of the C9ORF72 G4C2 repeat expansion and GFP gene, which has its own start site. During the whole study, ST littermates were used as a control and received the same dox treatment. (B) DNA isolated from different tissues from the same mouse (17129-5 ladder mouse on dox for 4 weeks), and analyzed with an Asuragen C9ORF72 PCR kit, showed a repeat length of 36 in all tissues. This was repeated in at least three independent mice. OL, out of limit. (C) Upper panel: GFP expression was detected in striatum and hippocampus cornu ammonis and hippocampus dentate gyrus in DT Camk2-alpha-rtTA/TRE-36G4C2-GFP mice after dox administration. Lower panel: GFP expression in EDL muscle, kidney and liver of DT hnRNP-rtTA/TRE-36×G4C2-GFP mice. GFP staining was performed on all mice in this study. ST, 4 weeks dox, n=15; DT, 4 weeks dox, n=16. Scale bars: 20 µm.

Heterozygous transgenic mice containing the TRE-36×G4C2-GFP construct were bred with two different heterozygous rtTA driver lines. We chose the CamK2α (Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II linked reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator) rtTA driver because of its validated expression in the hippocampus and cortex, brain areas that exhibit pathology in C9FTD/ALS patients (Odeh et al., 2011). To study expression in the rest of the body, we used an hnRNP (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein 2B1) rtTA driver. The resulting litters consisted of four different genotypes referred to in the rest of the paper as double transgenic (containing both the TRE-36×G4C2-GFP construct and one of the rtTA constructs) or single transgenic littermates (containing only the TRE or only an rtTA-driver construct). Wild-type littermates were not used in this study. Mice were administered doxycycline (dox) in their drinking water at 6 weeks of age to turn on transgene expression, which revealed specific expression of GFP in the double transgenic (DT) mice only and no transgene expression in single transgenic (ST) mice (Fig. S2). Using the hnRNP-rtTA driver, we observed expression in almost all tissues, including extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle, liver, kidney (Fig. 1C) heart and lung (Fig. S2), but not in brain and spinal cord after a maximum of 4 weeks of dox treatment (Fig. S2). Using the Camk2-alpha-rtTA driver, we observed GFP expression only in striatum and hippocampus dentate gyrus and cornu ammonis, as expected (Fig. 1C). GFP expression was detectable after 1 week of dox administration and remained detectable over 6 months (data not shown).

Human 36× G4C2 repeat mice show DPR expression but no RNA foci

To further characterize the expression of the transgene in our mouse model, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to test for the presence of sense and antisense RNA foci. Unfortunately, we were unable to detect RNA foci in multiple organs at 1-24 weeks of age in any of the driver lines (Fig. S3), despite the fact that our protocol was optimized to detect RNA foci in post-mortem human C9FTD/ALS frontal cortex paraffin tissue used as a positive control (Fig. S3). Sense-transcribed DPRs (poly-GA, -GP and -GR) were present in all GFP+ tissues of DT hnRNP-rtTA mice (Fig. 2). We did not observe antisense DPRs in mice (Fig. 2C-F), although we could detect them in C9FTD/ALS patient frontal cortex sections that were used as a positive control (Fig. 2A,B). To validate that no antisense transcripts were produced in our mouse model, we performed RT-PCR (Fig. S4). Again, antisense transcripts were only observed in RNA isolated from frozen frontal cortex of a human C9FTD patient (Fig. S4).

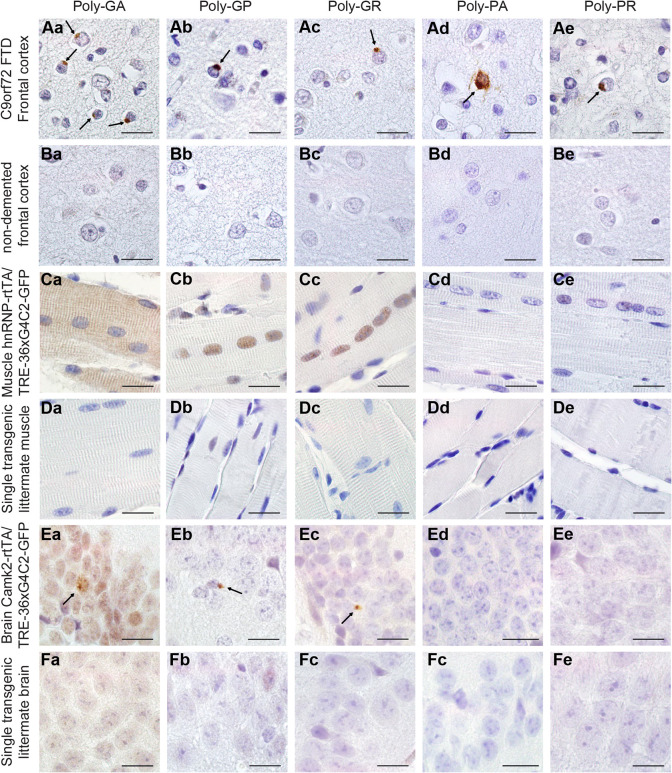

Fig. 2.

Expression of 36× G4C2 human repeats is sufficient to evoke sense DPR formation in vivo. (A,B) Human prefrontal cortex of C9FTD patients (A) or non-demented controls (B) were used as positive and negative controls for the detection of DPR pathology. Arrows indicate perinuclear aggregates of DPRs. (C) In TRE-36×G4C2-GFP/hnRNP-rtTA DT mice, poly-GA showed both diffuse cytoplasmic and nuclear localization, whereas diffuse poly-GP and poly-GR were observed in the nucleus of the EDL muscle. (D,F) ST littermates received the same dox treatment and contained only one transgene, either TRE only or rtTA only, and were all negative for DPRs. (E) TRE-36×G4C2-GFP/Camk2-alpha-rtTA DT mice showed some sparse perinuclear aggregates of sense DPRs in the hippocampus dentate gyrus (indicated by arrows). DPR staining was performed on all mice in this study. ST, 4 weeks dox, n=15; DT, 4 weeks dox, n=16. Scale bars: 20 µm.

Interestingly, sense DPRs differed in subcellular localization. Poly-GA was visible as diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic labeling in DT hnRNP-rtTA mice, whereas poly-GP and -GR were only observed in the nucleus (Fig. 2C,D; Fig. S5). In the DT Camk2-alpha-rtTA mice, we could detect some small perinuclear aggregates in the striatum and hippocampus after 24 weeks of dox administration (Fig. 2E,F). However, the numbers of aggregates were very rare (about one aggregate per sagittal brain section). Longer follow-up of these mice is not possible, as administration of dox for more than 6 months often leads to intestinal problems and an unacceptable level of discomfort for the mice. Both Camk2- and hnRNP-driven 36×G4C2 repeat mice showed no abundant pathological hallmarks of C9FTD/ALS, including p62 and phosphorylated TAR DNA-binding protein (pTDP-43) aggregates in brain and muscle (Fig. S6). Additionally, we did not observe any signs of neurodegeneration (cleaved caspase-3 staining, Fig. S6), astrogliosis or microgliosis (Fig. S7). As DPR inclusions were very rare in Camk2-alpha-rtTA mice and expression of DPRs was evident in the hnRNP-rtTA mice, we chose to focus on the DT hnRNP-rtTA mice for further assessment of the toxic effect of DPR expression in multiple organs in vivo.

The 36× G4C2 repeat mice develop a locomotor phenotype, rapid muscular dystrophy and neuromuscular junction abnormalities

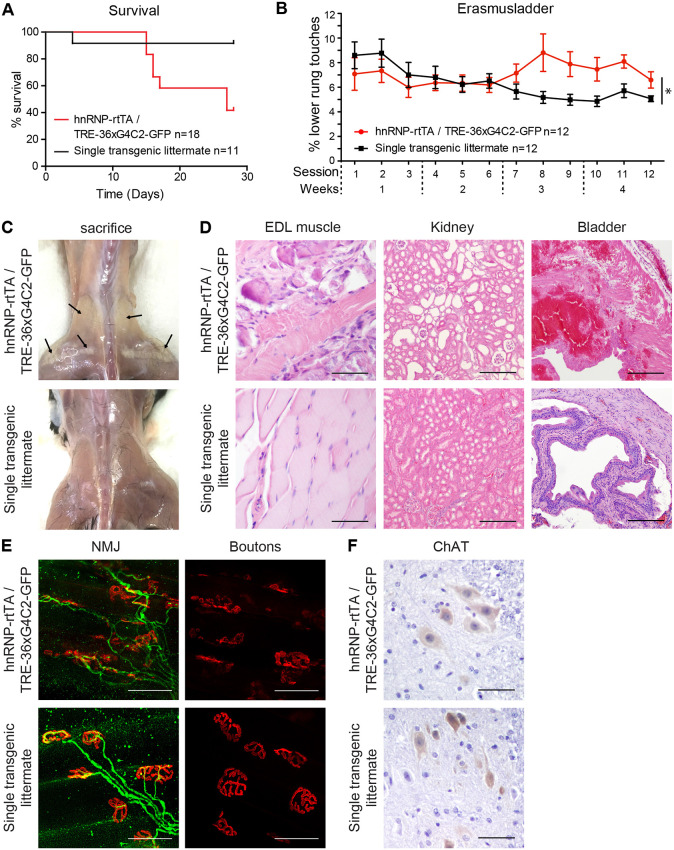

Expression of 36× G4C2 repeats using the hnRNP-rtTA driver led to profound toxicity. We started with dox treatment in 6-week-old mice to avoid DPRs affecting normal development, which would complicate behavioral and functional read-out. A large proportion (45%) of DT mice quickly declined in body weight in the first 2-3 weeks after dox administration and had to be sacrificed (Fig. 3A). Mice that quickly lost weight after 2.5 weeks showed general sickness symptoms (weight loss, bad condition of the fur, reduced activity and shivering) and an enlarged bladder. The majority of mice survived longer and did not lose weight but developed a locomotor phenotype on the Erasmus ladder (Fig. 3B; Fig. S8). This is a locomotor test based upon a horizontal ladder with alternating higher and lower rungs. Healthy C57Bl6/J mice prefer to walk on the higher rungs and avoid touching the lower rungs (Vinueza Veloz et al., 2015). DT mice began to touch the lower rungs more often after 2 weeks of dox treatment, although their performance was initially comparable to that of their ST littermates (Fig. 3B; Fig. S8; two-way ANOVA analysis: P=0.0001 for genotype and P<0.0001 for the interaction between genotype and time). DT mice sacrificed after 4 weeks of dox treatment displayed a white appearance of leg and back muscles macroscopically (Fig. 3C). At the histological level, a massive distortion of muscle fibers could be observed (Fig. 3D). Histological analysis of other tissues revealed enlarged renal tubules in the kidney and hemorrhages in the bladder of mice that quickly lost weight at 2.5 weeks (Fig. 3D). Analyses of the neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) by whole-mount immunostaining of the EDL muscle showed distortion of the muscular boutons and projecting motor neuron axons after 4 weeks of dox treatment (Fig. 3E). The number of motor neurons assessed by choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) staining of the spinal cord was not different between DT mice and ST control littermates (Fig. 3F). Together, these data indicate that expression of 36 pure G4C2 repeats in the body (but not expression in the brain) in our mouse model causes multisystem dysfunction, including urinary system problems and muscular dystrophy over the time course of 1 month.

Fig. 3.

Expression of 36× G4C2 human repeats in vivo causes a locomotor phenotype and muscular dystrophy within 4 weeks. (A) TRE-36×G4C2-GFP/hnRNP-rtTA DT mice that receive dox showed reduced survival after 1-3 weeks (n=18) compared to ST littermates [containing only one transgene (either TRE only or rtTA only)] who received the same dox treatment (n=11). (B) Mice that survive developed a locomotor phenotype on the Erasmus ladder after 7 sessions (3 sessions/week). N=12 mice per group. Note that from session 7 onwards, some mice had to be excluded due to severe pathology or incapability to cope with the behavioral assay. Session 12 includes data from N=10 ST control and N=8 DT mice. All mice received the same dox treatment. *P=0.0001 for genotype and P<0.0001 for the interaction between genotype and time (two-way ANOVA). Data are mean±s.e.m. (C) When sacrificed, DT mice exhibited back and upper leg muscles with a white appearance (indicated by arrows). (D) H&E staining of the EDL muscle, kidney and bladder of DT mice. (E) NMJ staining of the EDL muscle showed dissolving boutons (red, α-bungarotoxin) and disorganized axonal projections (green, neurofilament antibody). (F) The number of ChAT+ motor neurons in the spinal cord did not differ between DT and ST control littermates. All stainings were performed on all mice in this study. ST, 4 weeks dox, n=15; DT, 4 weeks dox, n=16. Scale bars: 50 µm (D, EDL and kidney images); 200 µm (D, bladder images); 50 µm (E); 20 µm (F).

Early withdrawal of 36× G4C2 repeat expression can prevent but not reverse the muscular dystrophy phenotype

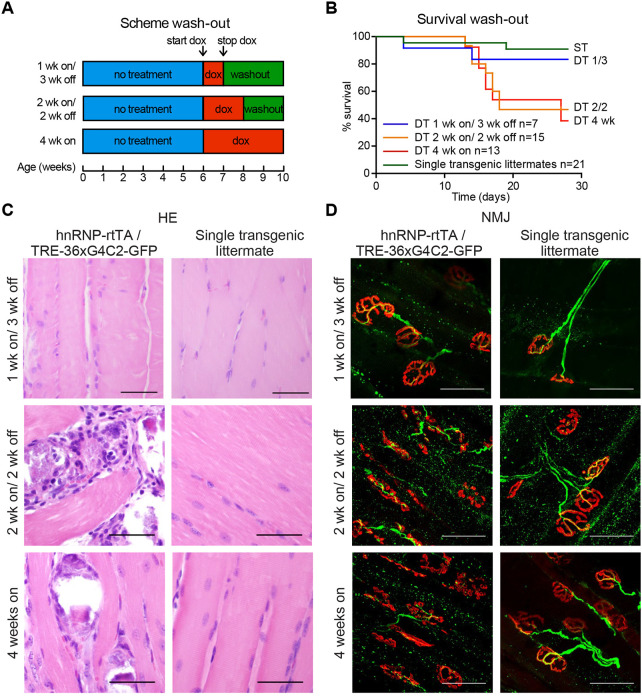

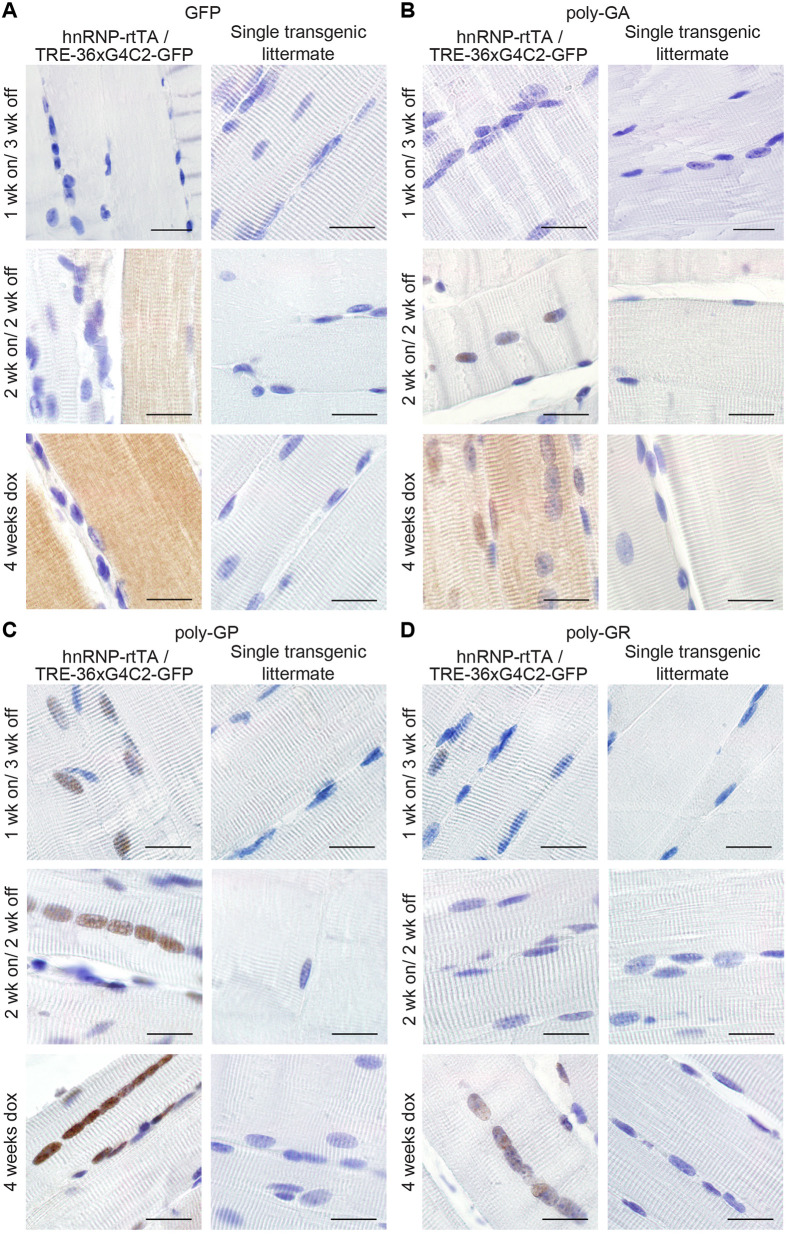

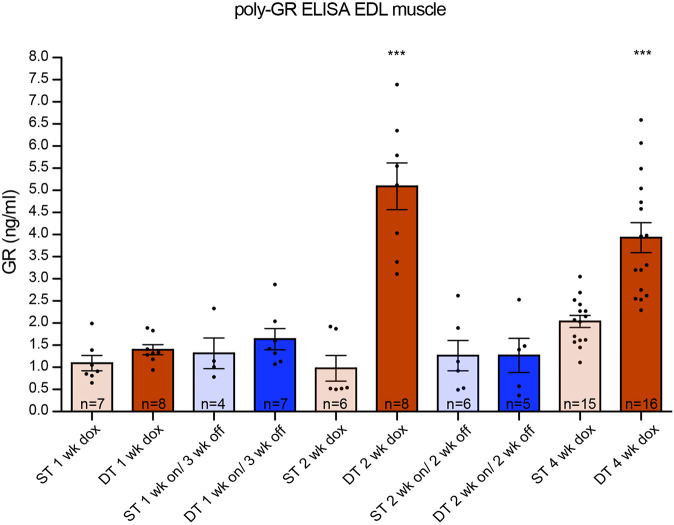

In order to investigate whether the phenotype could be reversed, we administered dox to 6-week-old DT and ST mice for 1 or 2 weeks and then changed them back to normal drinking water for 3 and 2 weeks, respectively (washout scheme shown in Fig. 4A). Mice that only received 1 week of dox followed by 3 weeks of washout showed high survival rates and normal muscle and NMJ integrity (Fig. 4). Approximately half of the DT mice that received 2 weeks of dox followed by 2 weeks of washout showed a rapid reduction in body weight after 2-3 weeks and did not survive to the end of the experiment (Fig. 4B). This washout group was indistinguishable from the 4 weeks dox DT group, with regards to survival, muscle and NMJ integrity. Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed that parts of the EDL displayed abnormal organization (Fig. 4C), and the NMJ showed disrupted boutons and axonal projections (Fig. 4D). Immunostaining for GFP, poly-GA and -GP in muscles of both washout groups showed a clear reduction in their levels but poly-GA and -GP were still detectable in nuclei of the 2 weeks on/ 2 weeks off group (Fig. 5). Only poly-GR could not be detected anymore (Fig. 5). In the kidney, GFP and all sense DPRs were cleared efficiently after dox withdrawal (Fig. S9). This indicates that DPR clearance is different for each organ or cell type. To study build-up and reduction of DPRs in a more quantitative way, we developed an ELISA for poly-GR, the DPR that shows the highest reported cellular toxicity. Poly-GR levels in EDL muscle increased significantly between the first and second week of dox administration, after which they stayed high (Fig. 6). In contrast, poly-GR levels in mice from the reversibility groups were reduced to similar levels as ST control mice (one-way ANOVA test: P=0.0001 with Bonferroni post test; Fig. 6). Together, our data show that early withdrawal of 36× pure G4C2 repeat expression can prevent the accumulation of DPRs and the concurrent phenotype. Expression of 36× pure G4C2 repeat expression for 2 weeks and subsequent withdrawal for 2 weeks is not sufficient to completely clear DPRs and reverse muscular dystrophy in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Early dox withdrawal can prevent but not reverse the muscular dystrophy and NMJ phenotype of TRE-36×G4C2-GFP/hnRNP-rtTA DT mice. (A) Schematic of different washout groups. (B) Survival curve for the washout experiment. Mice that received 1 week dox followed by 3 weeks washout (1 week on/ 3 weeks off, n=7) showed high survival. Two weeks dox followed by 2 weeks washout (2 weeks on/ 2 weeks off, n=15) showed the same reduction in survival as 4 weeks continuous dox administration (4 weeks on, n=13). ST littermates [containing only one transgene (either TRE only or rtTA only)] were distributed over the groups and received the same dox treatment (n=21). (C) H&E staining of the EDL muscle remained normal in the 1 week on/ 3 weeks off group but showed distortion in TRE-36×G4C2-GFP/hnRNP-rtTA DT mice that received 2 weeks dox followed by 2 weeks of normal drinking water. (D) NMJ of the EDL muscle showed collapsed boutons (red, α-bungarotoxin) and axonal projections (green, neurofilament antibody) in DT groups that received 2 or more weeks of dox. All stainings were performed on all mice in this study. Numbers per group were: ST, 1 week dox, n=7; DT, 1 week dox, n=8; ST, 1 week on/3 weeks off, n=4; DT, 1 week on/3 weeks off, n=7; ST, 2 weeks dox, n=6; DT, 2 weeks dox, n=8; ST, 2 weeks on/2 weeks off, n=6; DT, 2 weeks on/2 weeks off, n=5; ST, 4 weeks dox, n=15; DT, 4 weeks dox, n=16. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Fig. 5.

GFP and sense DPRs are reduced after dox withdrawal. (A) GFP staining of EDL muscle of TRE-36×G4C2-GFP/hnRNP-rtTA DT mice showed a reduction in the intensity of staining when mice received 1 or 2 weeks of dox water, followed by 2-3 weeks of normal drinking water compared to DT littermates that received 4 weeks of dox. (B) Poly-GA staining of EDL muscle showed clearance of cytoplasmic poly-GA in all washout groups but retention of nuclear poly-GA after 2 weeks of dox withdrawal. (C,D) Poly-GP staining is reduced in the nucleus of EDL muscle (C) and Poly-GR staining is cleared from nuclei of EDL muscles after dox withdrawal (D). ST littermates, consisting of either TRE only or rtTA only, received the same dox treatment and were all negative for GFP and DPRs. All stainings were performed on all mice in this study. Numbers per group were: ST, 1 week dox, n=7; DT, 1 week dox, n=8; ST, 1 week on/3 weeks off, n=4; DT, 1 week on/3 weeks off, n=7; ST, 2 weeks dox, n=6, DT, 2 weeks dox, n=8; ST, 2 weeks on/2 weeks off, n=6; DT, 2 weeks on/2 weeks off, n=5; ST, 4 weeks dox, n=15; DT, 4 weeks dox, n=16. Scale bars: 20 µm.

Fig. 6.

Expression of 36× G4C2 human repeats in vivo generates high levels of poly-GR, which are reduced to ST level after dox withdrawal. ELISA assessing poly-GR levels from mouse EDL muscle. Poly-GR was detectable in TRE-36×G4C2-GFP/hnRNP-rtTA DT mice that received 2-4 weeks of dox. DT mice that received 1-2 weeks dox followed by 2-3 weeks washout have reduced amounts of poly-GR, similar to ST levels. A one-way ANOVA (***P=0.0001) Bonferroni post test shows that the DT 2 weeks dox and DT 4 weeks dox groups were significantly different from all the other groups, but not from each other. All other ST and DT washout groups were not significantly different from each other. ST littermates [consisting of only one transgene (either TRE only or rtTA only)] received a similar dox treatment as DT animals. Numbers per group were: ST, 1 week dox, n=7; DT, 1 week dox, n=8; ST, 1 week on/3 weeks off, n=4; DT, 1 week on/3 weeks off, n=7; ST, 2 weeks dox, n=6; DT, 2 weeks dox, n=8; ST, 2 weeks on/2 weeks off, n=6; DT, 2 weeks on/2 weeks off, n=5; ST, 4 weeks dox, n=15; DT, 4 weeks dox, n=16. Data are mean±s.e.m.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that expression of 36× pure G4C2 repeats in vivo is sufficient to cause NMJ abnormalities and muscular dystrophy, leading to a specific locomotor phenotype within 4 weeks of transgene expression. Expression for 4 weeks did not evoke DPR expression in the brain, probably because 4 weeks are not long enough for build-up of DPRs and for dox to pass the blood-brain barrier (Michel et al., 1984). Expression of 36× pure G4C2 repeats for 24 weeks in the murine brain, using a Camk2-alpha-rtTA driver, was also not sufficient to result in pathology or neurodegeneration, making this mouse model inadequate for studying brain-specific DPR toxicity. We speculate that expression levels of the 36× G4C2 repeat RNA and DPRs in our Camk2-alpha-rtTA driven model are not high enough to induce neuropathology. Alternatively, the repeat length might not be long enough to evoke neurodegeneration. Other gain-of-function mouse models did show sense DPR pathology and a cognitive phenotype upon (over)expression of longer repeats (Chew et al., 2015; Herranz-Martin et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016). Mice expressing 500 repeats show a more severe phenotype compared with 29/36 repeat mice (Liu et al., 2016).

Upon expression of 36× pure G4C2 repeats in the body, our mouse model shows rapid muscular dystrophy and a locomotor phenotype. The phenotype could be caused by NMJ abnormalities or skeletal muscle dysfunction. Interestingly, DPR pathology has recently been found in skeletal muscle of C9ALS patients (Cykowski et al., 2019). DPR pathology has not been reported in human in tissues such as the kidney and bladder, even though C9ORF72 is expressed in these organs and C9KO mice show immune-mediated kidney damage (Atanasio et al., 2016; DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011). The pathology in our mouse model could be evoked by the relative rapid and strong repeat expression compared to the lower expression levels observed in C9FTD/ALS patients, but it would be interesting to investigate how widespread DPR pathology is. Many C9ORF72 mouse models lack locomotor symptoms due to unknown factors (Jiang et al., 2016; O'Rourke et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2015), and NMJ abnormalities have only been described in one BAC mouse model and one AAV-102x interrupted G4C2 mouse model (Herranz-Martin et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2016). Our mouse model shows similarities to the BAC 29/36 repeat mouse model reported by Liu et al. (2016), as both models show DPR pathology but no RNA foci. However, the phenotype in our mouse model develops faster (within 4 weeks after dox administration) than reported by Liu et al. (2016) (first symptoms started after 16 weeks of age). Differences in disease onset might be due to differences in expression levels. For example, lack of a phenotype was observed in a 37 repeat mouse with low expression levels (Liu et al., 2016), whereas our 36 repeat and the BAC 29/36 repeat mouse with higher expression levels clearly show a phenotype.

So far, the minimum repeat size to evoke RNA foci and DPR formation in vivo has remained unknown. A BAC mouse model of 110 repeats did not contain any RNA foci (Jiang et al., 2016), whereas BAC mice with longer repeat sizes did present with RNA foci (Jiang et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016; O'Rourke et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2015). On the other hand, AAV-mediated overexpression of 10 or 66 repeats did evoke RNA foci (Chew et al., 2015; Herranz-Martin et al., 2017), indicating that formation of RNA foci could also depend on expression levels. Even though we did not detect any RNA foci in our 36× repeat mouse model, we cannot exclude an effect of repeat RNA on the observed phenotype. Repeat-containing RNA molecules might still be able to sequester molecules or proteins and affect their normal function of cellular processes.

Sense DPRs were detected as diffuse cytoplasmic or nuclear staining and did not form aggregates in our hnRNP-driven mouse model. Recent publications on poly-GR and -PR mouse models suggest that soluble poly-GR and -PR are sufficient to cause neurodegeneration and behavioral deficits (Zhang et al., 2018, 2019). For poly-GA, aggregation seems necessary for its toxicity (Zhang et al., 2016). Thus, DPRs might differ in their abilities to aggregate, which can change their molecular targets and their effects on several cellular compartments and functions. Interestingly, poly-GA can spread throughout the brain and influence the aggregation of poly-GR and -PR (Darling et al., 2019; Morón-Oset et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2015), and this has been confirmed in AAV-66 and AAV-149x mice, in which poly-GA and -GR co-aggregate in cells with poly-GA aggregates, but poly-GR remains diffuse in cells devoid of poly-GA (Chew et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2018). Poly-GA expression can even partially suppress poly-GR-induced cell loss at the wing in a Drosophila model (Yang et al., 2015). Co-overexpression of poly-GA also abolished cellular toxicity of low concentrations of poly-PR in NSC34 cells (Darling et al., 2019). Other interactions between DPRs are still unknown and need further investigation. We did not detect antisense DPRs in our mouse model, perhaps because antisense C4G2 RNA is not transcribed or antisense DPR levels might be too low to detect.

Another point of interest is the lack of apparent pTDP-43 pathology in multiple C9ORF72 mouse models. TDP-43 pathology is thought to be a late event in the pathogenesis of C9FTD/ALS (Balendra and Isaacs, 2018). Several mouse models already show behavioral phenotypes and some mild neurodegeneration before the onset of pTDP-43 neuropathology (Herranz-Martin et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2016; Schludi et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018, 2016). Changes in pTDP-43 solubility or cellular localization could already arise and contribute to cellular distress without the formation of cytoplasmic aggregates per se (Lee et al., 2019). Indeed, several reports of C9FTD/ALS cases showed affected individuals with DPR pathology but mild or absent TDP-43 pathology (Baborie et al., 2015; Gijselinck et al., 2012; Mori et al., 2013; Proudfoot et al., 2014; Vatsavayai et al., 2016). Together, our hnRNP-driven mouse model shows that expression of diffuse labeled sense DPRs is sufficient to cause cellular toxicity without the need for RNA foci and pTDP-43 pathology.

The rapid translation of current knowledge into therapeutic intervention studies requires robust in vivo drug discovery screens (Jiang and Ravits, 2019). So far, antisense oligonucleotide (AON) therapy has been tested in a BAC mouse model for C9ORF72, and successfully reduced the amount of RNA foci and DPRs (Jiang et al., 2016). However, it remains unknown whether this AON can also reduce motor symptoms associated with the C9ORF72 repeat. New therapies are under development, including small molecules targeting RAN translation (Green et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2017; Kramer et al., 2016; Simone et al., 2018; Su et al., 2014; Zamiri et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015) and antibody therapy against poly-GA (Nguyen et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2019). These therapies can be easily tested in our mouse model, as it develops a quick and robust phenotype. Our mouse model can be used as proof of principle for whole-body toxicity of DPRs. We demonstrated that 1 week of expression followed by 3 weeks of washout (expression turned off) prevented the accumulation of DPRs and the associated cellular toxicity. However, 2 weeks of expression followed by 2 weeks of washout is not sufficient to prevent mice from developing muscular dystrophy. This indicates that transgene RNA or DPRs that were already produced during the first 2 weeks of dox administration continue to exercise their toxic effects. A recent publication estimated the half-lives of most DPRs to be >200 h (Westergard et al., 2019). The half-life was longer for poly-GA puncta than for diffuse poly-GA, and increased for poly-GR when localized in the nucleus (Westergard et al., 2019). Interestingly, poly-GP remains detectable after 1 week on/3 weeks off dox, indicating that poly-GP is not turning over as quickly as the other DPRs. Still, the animals of this reversibility group are improving, suggesting a bigger impact on the toxicity of poly-GA and poly-GR, as shown previously (Balendra and Isaacs, 2018; Mizielinska et al., 2014). In general, earlier intervention might be able to halt or reverse symptoms, but the preferred time window for treatment is probably before the onset of symptoms.

Together, we provide evidence that the expression of human 36× pure G4C2 repeats is sufficient to evoke RAN translation and a locomotor phenotype in vivo. High expression of sense DPRs driven by hnRNP-rtTA caused rapid progression of muscular dystrophy and NMJ disruption. This mouse model allows for fast in vivo screening of new drugs and compounds that act on the systemic toxicity of sense DPRs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning

DNA obtained from C9FTD patient 09D-5781 was assessed for the C9ORF72 repeat expansion with an Asuragen kit used according to manufacturer's protocol, and contained at least 54 repeats. DNA was amplified in three consecutive rounds of PCR with primers flanking the C9ORF72 repeat expansion (forward primer, 5′-CCACGGAGGGATGTTCTTTA-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-GAAACCAGACCCAAACACAGA-3′) and a PCR mix containing 50% betaine. The PCR program started with 10 min at 98°C, followed by 35 cycles of 35 s at 98°C, 35 s at 58°C and 3 min at 72°C and finished with 10 min at 72°C. The PCR product was cloned into TOPO vector PCR2.1, and restriction analysis with BsiEI (New England Biolabs) for 1 h at 60°C revealed a G4C2 repeat expansion estimated to consist of ∼50 repeats. Next, the TRE-90CGG-GFP vector (Hukema et al., 2014) was restricted with SacII (New England Biolabs), and the 90xCGG repeat expansion was replaced with the 50x G4C2 repeat expansion. This vector was sequenced using a primer in the TRE sequence (5′-CGGGTCCAGTAGGCGTGTAC-3′) and revealed a repeat expansion of 36× G4C2. The final vector was cut with AatII, PvuI and NdeI (NEB), and the band containing the TRE-36× G4C2-GFP construct was isolated from a gel, dissolved in injection buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.25 mM EDTA) and used to generate transgenic mice. Experiments on human material were performed under informed consent and approved by the Medical Ethical Test Committee (METC). All investigations with human materials were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Animals

Pronuclei from oocytes of C57BL/6JRj wild-type mice were injected to create a new transgenic line harboring the TRE-36×G4C2-GFP construct. Genotyping was performed using primers located in the 5′ region of the repeat expansion (forward, 5′-GGTACCCGGGTCGAGGTAGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTACAGGCTGCGGTTGTTTCC-3′). Founder mice, F1 and F2, were screened in an animal welfare assessment by the local animal caretakers and scored as normal for litter size and health characteristics. All mice were housed in groups of two to four and were allowed to have free access to standard laboratory food and water. They were kept in a 12-h light/dark cycle. TRE-36×G4C2-GFP mice were crossed with hnRNP-rtTA (Katsantoni et al., 2007) or Camk2-alpha-rtTA (kind gift of Rob Berman, The University of California, Davis, USA) on a C57BL/6JRj wild-type background. Offspring should include 25% of DT mice (harboring both the TRE and one of the rtTA constructs), 50% of ST littermates (harboring either the TRE or the rtTA construct) and 25% of wild-type littermates (having no transgene). At 6 weeks of age, mice of both sexes were exposed to dox (Sigma-Aldrich) (4 grams/l) combined with sucrose (50 grams/l) dissolved in drinking water. Both ST and DT mice received dox water. To monitor their health and wellbeing, mice were weighed every weekday while on dox water (data not shown). TRE-36×G4C2-GFP/hnRNP-rtTA mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation after a maximum of 4 weeks of dox administration. The TRE-36×G4C2-GFP/Camk2-alpha-rtTA mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation after a maximum of 24 weeks of dox administration. As required by Dutch legislation, all experiments were approved in advance by the institutional Animal Welfare Committee (Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands).

Erasmus ladder

The Erasmus ladder (Noldus, Wageningen, The Netherlands) is a fully automated test for detecting motor performance in mice (Vinueza Veloz et al., 2012). It consists of a horizontal ladder between two shelters, which are equipped with a bright white LED spotlight and pressurized air outlets. These are used as cues for the departure from the shelter box to the other shelter box. The ladder has 2×37 rungs for the left and right side. All rungs have pressure sensors, which are continuously monitoring and registering the walking pattern of the mouse. The rungs are placed in an alternating high/low pattern. Wild-type C57Bl6 mice prefer to walk on the higher rungs, avoiding touching the lower rungs (Vinueza Veloz et al., 2015). The mouse was placed in the starting box and after a period varying from 9 to 11 s, the LED light turned on and the mouse was supposed to leave the box. If the mouse left the box before the light turned on a strong air flow drove the mouse back into the box, and the waiting period restarted. If the mouse did not leave the box within 3 s after the light turned on, a strong air flow drove the mouse out of the box. When the mouse arrived in the other box, the lights and air flow turned off and the waiting period from 9 to 11 s started and the cycle repeated again, making mice run back and forth on the ladder. Mice were trained on the Erasmus ladder at the age of 5 weeks, every day for 5 days. The mice were trained to walk the ladder for 42 runs each day. At the age of 6 weeks, the mice received dox/sucrose water and were tested on Monday, Wednesday and Friday on the Erasmus ladder. The average percentage of lower rung touches was calculated over 42 runs per session.

NMJ staining

EDL muscles were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde overnight. The muscles were washed in PBS and permeabilized in 2.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 30 min and incubated in 1 µg/ml α-bungarotoxin-TRITC (Invitrogen) in 1 M NaCl for 30 min. Subsequently, muscles were incubated for 1 h in a blocking solution [4% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.5% Triton X-100]. After blocking, the muscles were incubated with a polyclonal chicken anti-neurofilament antibody (2BScientific) 1:500 in blocking solution overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation for 4 h with anti-chicken Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Finally, the muscles were mounted on slides with 1.8% low-melting point agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and images were taken using a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope. The first author was blinded during image acquisition.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

Brain and EDL muscle tissues of mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Tissues were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin, and cut into 6 µm sections using a rotary microtome. Post-mortem human C9FTD/ALS frontal cortex paraffin tissue was used as a positive control for RNA foci detection. Sections were deparaffinized using xylene, and rehydrated in a standard alcohol series. Antigen retrieval was established in 0.01 M sodium citrate with pH 6 using microwave treatment of 1×9 min followed by 2×3 min at 800W. Subsequently, the slides were dehydrated in an alcohol series and briefly dried in air. Next, pre-hybridization was performed in hybridization solution (dextran sulphate 10% w/v, formamide 50%, 2× SSC) for 1 h at 65°C. After pre-hybridization, hexanucleotide sense oligo (5′-Cy5-4xGGGGCC-3′) and hexanucleotide antisense oligo (5′-Cy5-4xCCCCGG-3′) probes (IDT) were diluted to 40 nM in hybridization solution and heated to 95°C for 5 min. The slides were hybridized with probe mix overnight at 65°C. After hybridization, the slides were washed once with 2× SSC/0.1% Tween 20 and three times with 0.1× SSC at 65°C. Subsequently, slides were stained with Hoechst (Invitrogen), washed with PBS and stained with Sudan Black (Sigma-Aldrich). Finally, slides were dehydrated and mounted using Pro-Long Gold mounting solution (Invitrogen), and images were taken using a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope. C9FTD/ALS and non-demented control human brain sections were provided by the Dutch Brain Bank.

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, and dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Sections (6 µm) were cut using a rotary microtome. Sections were deparaffinized using xylene and rehydrated in an alcohol series. Antigen retrieval was established in 0.01 M sodium citrate with pH 6 using microwave treatment of 1×9 min followed by 2×3 min at 800W. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2 and 1.25% sodium azide. Immunostaining was performed overnight at 4°C in PSB block buffer (1× PBS/0.5% protifar/0.15% glycine) and with the primary antibodies (see Table S1 for all antibodies used in this study). The next day, sections were washed with PBS block buffer, and antigen-antibody complexes were visualized by incubation with DAB substrate (Dako) after incubation with Brightvision poly-horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linker (Immunologic) or anti-mouse/rabbit HRP (Dako). Slides were counterstained with Mayer's haematoxylin and mounted with Entellan (Merck Millipore). The slides were imaged using an Olympus BX40 microscope.

Protein isolation

Before lysing, EDL muscle samples were thawed on ice and supplied with RIPA buffer containing 0.05% protease inhibitors (Roche) and 0.3% 1 M DTT (Invitrogen). Samples were mechanically lysed, followed by 30 min incubation on ice. After 30 min incubation, mechanical lysing was repeated and samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 17 g at 4°C, followed by 3×1 min sonication. After sonication, samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 17 g at 4°C and the supernatant was used for ELISA. Whole protein content was determined using a BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

ELISA

MaxiSorp 96-well F-bottom plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated for 2 h with 5 µg/ml monoclonal GR antibody, followed by overnight blocking with 1% BSA in PBS-Tween (0.05% Tween 20, Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C. After washing, 300 µg total protein lysate was added per sample. A 15x GR synthetic peptide (LifeTein) was used as a positive control. This peptide was serial diluted to create a standard curve (in duplo). All samples were measured both undiluted and diluted 2× and 4× with 0.1 M PBS. Samples and GR peptide were incubated on the plate for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, all wells were incubated for 1 h with biotinylated monoclonal anti-GR antibody at a final concentration of 0.25 µg/ml in PBS-Tween 20/1% BSA. After washing again, samples were incubated for 20 min with Streptavidin-HRP (R&D Systems) diluted 1:200 in PBS-Tween 20/1% BSA. Following extensive washing, samples were incubated with substrate reaction mix (R&D Systems) for 15 min and stopped using 2N H2SO4. Read-out was carried out using a plate reader (Varioskan) at 450 nm and 570 nm.

C9ORF72 strand-specific RT-PCR

RNA isolation was performed on mouse frozen kidney tissue and frozen frontal cortex of two C9FTD patients. Tissue was homogenized in 500 µl RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl; 5 mM EDTA; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1% Nonidet-P40; 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; and 0.1% SDS, pH 7.6) containing complete protease inhibitor (Roche), 3 mM DTT (Invitrogen) and 40 units of RNAse OUT (Invitrogen). RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), according to manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription was performed with 250 ng of RNA using a SuperScriptIII cDNA Synthesis kit (Invitrogen), according to manufacturer's instructions. RNA was treated with DNase before cDNA synthesis. The following C9ORF72 strand-specific primers were used to generate cDNA: LK-ASORF-R, 5′-CGACTGGAGCACGAGGACACTGACGAGTGGGTGAGTGAGGAG-3′ (after repeat) (Zu et al., 2013); or LK-ASORF-R2, 5′-CGACTGGAGCACGAGGACACTGAGTAGCAAGCTCTGGAACTCAGGAGTCG-3′ (before repeat) (Liu et al. 2017; Rizzu et al. 2016). For C9 FTD patient samples, PCR was performed using LK specific primer, 5′-CGACTGGAGCACGAGGACACTGA-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-AGTCGCTAGAGGCGAAAGC-3′. For mouse samples, PCR was performed using LK specific primer, 5′-CGACTGGAGCACGAGGACACTGA-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-CTCCTCACTCACCCACTCG-3′. The PCR program was as follows: 4 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 45 s at 94°C, 45 s at 58°C and 90 s at 72°C, followed by 6 min at 72°C.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Rob Berman for the Camk2-alpha-rtTA driver and Lies-Anne Severijnen for her guidance regarding immunohistochemical studies and the anti-neurofilament antibody. We also thank Leonard Petrucelli for providing an aliquot of his anti-PA antibody and Elize Haasdijk for an aliquot of ChAT antibody.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: F.W.R., E.C.v.d.T., R.F.M.V., R.K.H., R.W.; Methodology: F.W.R., E.C.v.d.T., R.F.M.V., A.M., L.W.J.B., R.K.H.; Software: L.W.J.B.; Formal analysis: F.W.R., E.C.v.d.T., R.F.M.V.; Investigation: F.W.R., E.C.v.d.T., R.F.M.V.; Resources: A.M., L.W.J.B., R.W.; Writing - original draft: F.W.R.; Writing - review & editing: F.W.R., L.W.J.B., R.K.H., R.W.; Visualization: F.W.R., E.C.v.d.T., R.F.M.V., L.W.J.B.; Supervision: R.W.; Project administration: F.W.R., R.W.; Funding acquisition: R.W., F.W.R.

Funding

This study was supported by the European Joint Programme – Neurodegenerative Disease Research and ZonMw (PreFrontALS: 733051042 to R.W.), and by Alzheimer Nederland (WE03.2012-XX to R.W. and F.W.R.).

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at https://dmm.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dmm.044842.supplemental

References

- Ash, P. E., Bieniek, K. F., Gendron, T. F., Caulfield, T., Lin, W. L., Dejesus-Hernandez, M., van Blitterswijk, M. M., Jansen-West, K., Paul, J. W., III, Rademakers, R.et al. (2013). Unconventional translation of C9ORF72 GGGGCC expansion generates insoluble polypeptides specific to c9FTD/ALS. Neuron 77, 639-646. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atanasio, A., Decman, V., White, D., Ramos, M., Ikiz, B., Lee, H. C., Siao, C. J., Brydges, S., LaRosa, E., Bai, Y.et al. (2016). C9orf72 ablation causes immune dysregulation characterized by leukocyte expansion, autoantibody production, and glomerulonephropathy in mice. Sci. Rep. 6, 23204 10.1038/srep23204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baborie, A., Griffiths, T. D., Jaros, E., Perry, R., McKeith, I. G., Burn, D. J., Masuda-Suzukake, M., Hasegawa, M., Rollinson, S., Pickering-Brown, S.et al. (2015). Accumulation of dipeptide repeat proteins predates that of TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration associated with hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9ORF72 gene. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 41, 601-612. 10.1111/nan.12178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balendra, R. and Isaacs, A. M. (2018). C9orf72-mediated ALS and FTD: multiple pathways to disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14, 544-558. 10.1038/s41582-018-0047-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra, R. and Lee, C. W. (2017). Mouse models of C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/ frontotemporal dementia. Front. Cell Neurosci. 11, 196 10.3389/fncel.2017.00196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzil, V. V., Bauer, P. O., Prudencio, M., Gendron, T. F., Stetler, C. T., Yan, I. K., Pregent, L., Daughrity, L., Baker, M. C., Rademakers, R.et al. (2013). Reduced C9orf72 gene expression in c9FTD/ALS is caused by histone trimethylation, an epigenetic event detectable in blood. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 895-905. 10.1007/s00401-013-1199-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeynaems, S., Bogaert, E., Michiels, E., Gijselinck, I., Sieben, A., Jovicic, A., De Baets, G., Scheveneels, W., Steyaert, J., Cuijt, I.et al. (2016). Drosophila screen connects nuclear transport genes to DPR pathology in c9ALS/FTD. Sci. Rep. 6, 20877 10.1038/srep20877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew, J., Gendron, T. F., Prudencio, M., Sasaguri, H., Zhang, Y.-J., Castanedes-Casey, M., Lee, C. W., Jansen-West, K., Kurti, A., Murray, M. E.et al. (2015). Neurodegeneration. C9ORF72 repeat expansions in mice cause TDP-43 pathology, neuronal loss, and behavioral deficits. Science 348, 1151-1154. 10.1126/science.aaa9344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew, J., Cook, C., Gendron, T. F., Jansen-West, K., del Rosso, G., Daughrity, L. M., Castanedes-Casey, M., Kurti, A., Stankowski, J. N., Disney, M. D.et al. (2019). Aberrant deposition of stress granule-resident proteins linked to C9orf72-associated TDP-43 proteinopathy. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 9 10.1186/s13024-019-0310-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, J. D., Pattamatta, A. and Ranum, L. P. W. (2018). Repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 16127-16141. 10.1074/jbc.R118.003237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couratier, P., Corcia, P., Lautrette, G., Nicol, M. and Marin, B. (2017). ALS and frontotemporal dementia belong to a common disease spectrum. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 173, 273-279. 10.1016/j.neurol.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cykowski, M. D., Dickson, D. W., Powell, S. Z., Arumanayagam, A. S., Rivera, A. L. and Appel, S. H. (2019). Dipeptide repeat (DPR) pathology in the skeletal muscle of ALS patients with C9ORF72 repeat expansion. Acta Neuropathol. 138, 667-670. 10.1007/s00401-019-02050-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling, A. L., Breydo, L., Rivas, E. G., Gebru, N. T., Zheng, D., Baker, J. D., Blair, L. J., Dickey, C. A., Koren, J., III and Uversky, V. N. (2019). Repeated repeat problems: Combinatorial effect of C9orf72-derived dipeptide repeat proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 127, 136-145. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus-Hernandez, M., Mackenzie, I. R., Boeve, B. F., Boxer, A. L., Baker, M., Rutherford, N. J., Nicholson, A. M., Finch, N. A., Flynn, H., Adamson, J.et al. (2011). Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72, 245-256. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, C., Barbier, M., Camuzat, A., Anquetil, V., Lattante, S., Clot, F., Cazeneuve, C., Rinaldi, D., Couratier, P., Deramecourt, V.et al. (2019). Relations between C9orf72 expansion size in blood, age at onset, age at collection and transmission across generations in patients and presymptomatic carriers. Neurobiol. Aging 74, 234.e1-234.e8. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron, T. F., Bieniek, K. F., Zhang, Y.-J., Jansen-West, K., Ash, P. E., Caulfield, T., Daughrity, L., Dunmore, J. H., Castanedes-Casey, M., Chew, J.et al. (2013). Antisense transcripts of the expanded C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat form nuclear RNA foci and undergo repeat-associated non-ATG translation in c9FTD/ALS. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 829-844. 10.1007/s00401-013-1192-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijselinck, I., Van Langenhove, T., van der Zee, J., Sleegers, K., Philtjens, S., Kleinberger, G., Janssens, J., Bettens, K., Van Cauwenberghe, C., Pereson, S.et al. (2012). A C9orf72 promoter repeat expansion in a Flanders-Belgian cohort with disorders of the frontotemporal lobar degeneration-amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spectrum: a gene identification study. Lancet Neurol. 11, 54-65. 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70261-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijselinck, I., Van Mossevelde, S., van der Zee, J., Sieben, A., Engelborghs, S., De Bleecker, J., Ivanoiu, A., Deryck, O., Edbauer, D., Zhang, M.et al. (2016). The C9orf72 repeat size correlates with onset age of disease, DNA methylation and transcriptional downregulation of the promoter. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 1112-1124. 10.1038/mp.2015.159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittings, L. M., Boeynaems, S., Lightwood, D., Clargo, A., Topia, S., Nakayama, L., Troakes, C., Mann, D. M. A., Gitler, A. D., Lashley, T.et al. (2020). Symmetric dimethylation of poly-GR correlates with disease duration in C9orf72 FTLD and ALS and reduces poly-GR phase separation and toxicity. Acta Neuropathol. 139, 407-410. 10.1007/s00401-019-02104-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grad, L. I., Rouleau, G. A., Ravits, J. and Cashman, N. R. (2017). Clinical spectrum of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 7, a024117 10.1101/cshperspect.a024117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, K. M., Linsalata, A. E. and Todd, P. K. (2016). RAN translation-What makes it run? Brain Res. 1647, 30-42. 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, K. M., Sheth, U. J., Flores, B. N., Wright, S. E., Sutter, A. B., Kearse, M. G., Barmada, S. J., Ivanova, M. I. and Todd, P. K. (2019). High-throughput screening yields several small-molecule inhibitors of repeat-associated non-AUG translation. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 18624-18638. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.009951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeusler, A. R., Donnelly, C. J. and Rothstein, J. D. (2016). The expanding biology of the C9orf72 nucleotide repeat expansion in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 383-395. 10.1038/nrn.2016.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Z., Liu, L., Tao, Z., Wang, R., Ren, H., Sun, H., Lin, Z., Zhang, Z., Mu, C., Zhou, J.et al. (2019). Motor dysfunction and neurodegeneration in a C9orf72 mouse line expressing poly-PR. Nat. Commun. 10, 2906 10.1038/s41467-019-10956-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, I., Fernandez, M. V., Tarraga, L., Boada, M. and Ruiz, A. (2018). Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD): review and update for clinical neurologists. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 15, 511-530. 10.2174/1567205014666170725130819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz-Martin, S., Chandran, J., Lewis, K., Mulcahy, P., Higginbottom, A., Walker, C., Valenzuela, I. M. Y., Jones, R. A., Coldicott, I., Iannitti, T.et al. (2017). Viral delivery of C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions in mice leads to repeat-length-dependent neuropathology and behavioural deficits. Dis. Model. Mech. 10, 859-868. 10.1242/dmm.029892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J., Rigo, F., Prakash, T. P. and Corey, D. R. (2017). Recognition of c9orf72 Mutant RNA by Single-Stranded Silencing RNAs. Nucleic Acid Ther 27, 87-94. 10.1089/nat.2016.0655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hukema, R. K., Buijsen, R. A., Raske, C., Severijnen, L. A., Nieuwenhuizen-Bakker, I., Minneboo, M., Maas, A., de Crom, R., Kros, J. M., Hagerman, P. J.et al. (2014). Induced expression of expanded CGG RNA causes mitochondrial dysfunction in vivo. Cell Cycle 13, 2600-2608. 10.4161/15384101.2014.943112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoangeli, A., Al Khleifat, A., Jones, A. R., Sproviero, W., Shatunov, A., Opie-Martin, S., Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Morrison, K. E., Shaw, P. J., Shaw, C. E.et al. (2019). C9orf72 intermediate expansions of 24-30 repeats are associated with ALS. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 7, 115 10.1186/s40478-019-0724-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J. and Ravits, J. (2019). Pathogenic mechanisms and therapy development for C9orf72 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotemporal dementia. Neurotherapeutics 16, 1115-1132. 10.1007/s13311-019-00797-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J., Zhu, Q., Gendron, T. F., Saberi, S., McAlonis-Downes, M., Seelman, A., Stauffer, J. E., Jafar-Nejad, P., Drenner, K., Schulte, D.et al. (2016). Gain of toxicity from ALS/FTD-linked repeat expansions in C9ORF72 is alleviated by antisense oligonucleotides targeting GGGGCC-containing RNAs. Neuron 90, 535-550. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovicic, A., Mertens, J., Boeynaems, S., Bogaert, E., Chai, N., Yamada, S. B., Paul, J. W., III, Sun, S., Herdy, J. R., Bieri, G.et al. (2015). Modifiers of C9orf72 dipeptide repeat toxicity connect nucleocytoplasmic transport defects to FTD/ALS. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1226-1229. 10.1038/nn.4085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanekura, K., Yagi, T., Cammack, A. J., Mahadevan, J., Kuroda, M., Harms, M. B., Miller, T. M. and Urano, F. (2016). Poly-dipeptides encoded by the C9ORF72 repeats block global protein translation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25, 1803-1813. 10.1093/hmg/ddw052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsantoni, E. Z., Anghelescu, N. E., Rottier, R., Moerland, M., Antoniou, M., de Crom, R., Grosveld, F. and Strouboulis, J. (2007). Ubiquitous expression of the rtTA2S-M2 inducible system in transgenic mice driven by the human hnRNPA2B1/CBX3 CpG island. BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 108 10.1186/1471-213X-7-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovanda, A., Zalar, M., Šket, P., Plavec, J. and Rogelj, B. (2015). Anti-sense DNA d(GGCCCC)n expansions in C9ORF72 form i-motifs and protonated hairpins. Sci. Rep. 5, 17944 10.1038/srep17944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, N. J., Carlomagno, Y., Zhang, Y. J., Almeida, S., Cook, C. N., Gendron, T. F., Prudencio, M., Van Blitterswijk, M., Belzil, V., Couthouis, J.et al. (2016). Spt4 selectively regulates the expression of C9orf72 sense and antisense mutant transcripts. Science 353, 708-712. 10.1126/science.aaf7791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, I., Xiang, S., Kato, M., Wu, L., Theodoropoulos, P., Wang, T., Kim, J., Yun, J., Xie, Y. and McKnight, S. L. (2014). Poly-dipeptides encoded by the C9orf72 repeats bind nucleoli, impede RNA biogenesis, and kill cells. Science 345, 1139-1145. 10.1126/science.1254917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. M., Asress, S., Hales, C. M., Gearing, M., Vizcarra, J. C., Fournier, C. N., Gutman, D. A., Chin, L. S., Li, L. and Glass, J. D. (2019). TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusion formation is disrupted in C9orf72-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain Commun. 1, fcz014 10.1093/braincomms/fcz014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., Hu, J., Ludlow, A. T., Pham, J. T., Shay, J. W., Rothstein, J. D., Corey, D. R. (2017). c9orf72 disease-related foci Are each composed of one mutant expanded repeat RNA. Cell Chem. Biol. 24, 141-148. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Pattamatta, A., Zu, T., Reid, T., Bardhi, O., Borchelt, D. R., Yachnis, A. T. and Ranum, L. P. (2016). C9orf72 BAC mouse model with motor deficits and neurodegenerative features of ALS/FTD. Neuron 90, 521-534. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, I. R., Frick, P., Grasser, F. A., Gendron, T. F., Petrucelli, L., Cashman, N. R., Edbauer, D., Kremmer, E., Prudlo, J., Troost, D.et al. (2015). Quantitative analysis and clinico-pathological correlations of different dipeptide repeat protein pathologies in C9ORF72 mutation carriers. Acta Neuropathol. 130, 845-861. 10.1007/s00401-015-1476-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel, G., Mosser, J. and Olle, J. (1984). Pharmacokinetics and tissue localization of doxycycline polyphosphate and doxycycline hydrochloride in the rat. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 9, 149-153. 10.1007/BF03189618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizielinska, S., Lashley, T., Norona, F. E., Clayton, E. L., Ridler, C. E., Fratta, P. and Isaacs, A. M. (2013). C9orf72 frontotemporal lobar degeneration is characterised by frequent neuronal sense and antisense RNA foci. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 845-857. 10.1007/s00401-013-1200-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizielinska, S., Gronke, S., Niccoli, T., Ridler, C. E., Clayton, E. L., Devoy, A., Moens, T., Norona, F. E., Woollacott, I. O., Pietrzyk, J.et al. (2014). C9orf72 repeat expansions cause neurodegeneration in Drosophila through arginine-rich proteins. Science 345, 1192-1194. 10.1126/science.1256800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, K., Weng, S.-M., Arzberger, T., May, S., Rentzsch, K., Kremmer, E., Schmid, B., Kretzschmar, H. A., Cruts, M., Van Broeckhoven, C.et al. (2013). The C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat is translated into aggregating dipeptide-repeat proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science 339, 1335-1338. 10.1126/science.1232927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morón-Oset, J., Super, T., Esser, J., Isaacs, A. M., Gronke, S. and Partridge, L. (2019). Glycine-alanine dipeptide repeats spread rapidly in a repeat length- and age-dependent manner in the fly brain. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 7, 209 10.1186/s40478-019-0860-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L., Montrasio, F., Pattamatta, A., Tusi, S. K., Bardhi, O., Meyer, K. D., Hayes, L., Nakamura, K., Banez-Coronel, M., Coyne, A.et al. (2020). Antibody therapy targeting RAN proteins rescues C9 ALS/FTD phenotypes in C9orf72 mouse model. Neuron 105, 645-662.e11. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordin, A., Akimoto, C., Wuolikainen, A., Alstermark, H., Jonsson, P., Birve, A., Marklund, S. L., Graffmo, K. S., Forsberg, K., Brannstrom, T.et al. (2015). Extensive size variability of the GGGGCC expansion in C9orf72 in both neuronal and non-neuronal tissues in 18 patients with ALS or FTD. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 3133-3142. 10.1093/hmg/ddv064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odeh, F., Leergaard, T. B., Boy, J., Schmidt, T., Riess, O. and Bjaalie, J. G. (2011). Atlas of transgenic Tet-Off Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and prion protein promoter activity in the mouse brain. Neuroimage 54, 2603-2611. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke, J. G., Bogdanik, L., Muhammad, A. K., Gendron, T. F., Kim, K. J., Austin, A., Cady, J., Liu, E. Y., Zarrow, J., Grant, S.et al. (2015). C9orf72 BAC transgenic mice display typical pathologic features of ALS/FTD. Neuron 88, 892-901. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oskarsson, B., Gendron, T. F. and Staff, N. P. (2018). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an update for 2018. Mayo Clin. Proc. 93, 1617-1628. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, O. M., Cabrera, G. T., Tran, H., Gendron, T. F., McKeon, J. E., Metterville, J., Weiss, A., Wightman, N., Salameh, J., Kim, J.et al. (2015). Human C9ORF72 hexanucleotide expansion reproduces RNA foci and dipeptide repeat proteins but not neurodegeneration in BAC transgenic mice. Neuron 88, 902-909. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot, M., Gutowski, N. J., Edbauer, D., Hilton, D. A., Stephens, M., Rankin, J. and Mackenzie, I. R. (2014). Early dipeptide repeat pathology in a frontotemporal dementia kindred with C9ORF72 mutation and intellectual disability. Acta Neuropathol. 127, 451-458. 10.1007/s00401-014-1245-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renton, A. E., Majounie, E., Waite, A., Simon-Sanchez, J., Rollinson, S., Gibbs, J. R., Schymick, J. C., Laaksovirta, H., van Swieten, J. C., Myllykangas, L.et al. (2011). A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72, 257-268. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzu, P., Blauwendraat, C., Heetveld, S., Lynes, E. M., Castillo-Lizardo, M., Dhingra, A., Pyz, E., Hobert, M., Synofzik, M., Francescatto, M.et al. (2016). C9orf72 is differentially expressed in the central nervous system and myeloid cells and consistently reduced in C9orf72, MAPT and GRN mutation carriers. Acta neuropathol. commun. 4, 37 10.1186/s40478-016-0306-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saberi, S., Stauffer, J. E., Jiang, J., Garcia, S. D., Taylor, A. E., Schulte, D., Ohkubo, T., Schloffman, C. L., Maldonado, M., Baughn, M.et al. (2018). Sense-encoded poly-GR dipeptide repeat proteins correlate to neurodegeneration and uniquely co-localize with TDP-43 in dendrites of repeat-expanded C9orf72 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 135, 459-474. 10.1007/s00401-017-1793-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakae, N., Bieniek, K. F., Zhang, Y. J., Ross, K., Gendron, T. F., Murray, M. E., Rademakers, R., Petrucelli, L. and Dickson, D. W. (2018). Poly-GR dipeptide repeat polymers correlate with neurodegeneration and Clinicopathological subtypes in C9ORF72-related brain disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 6, 63 10.1186/s40478-018-0564-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schludi, M. H., Becker, L., Garrett, L., Gendron, T. F., Zhou, Q., Schreiber, F., Popper, B., Dimou, L., Strom, T. M., Winkelmann, J.et al. (2017). Spinal poly-GA inclusions in a C9orf72 mouse model trigger motor deficits and inflammation without neuron loss. Acta Neuropathol. 134, 241-254. 10.1007/s00401-017-1711-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellier, C., Campanari, M. L., Julie Corbier, C., Gaucherot, A., Kolb-Cheynel, I., Oulad-Abdelghani, M., Ruffenach, F., Page, A., Ciura, S., Kabashi, E.et al. (2016). Loss of C9ORF72 impairs autophagy and synergizes with polyQ Ataxin-2 to induce motor neuron dysfunction and cell death. EMBO J. 35, 1276-1297. 10.15252/embj.201593350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y., Lin, S., Staats, K. A., Li, Y., Chang, W. H., Hung, S. T., Hendricks, E., Linares, G. R., Wang, Y., Son, E. Y.et al. (2018). Haploinsufficiency leads to neurodegeneration in C9ORF72 ALS/FTD human induced motor neurons. Nat. Med. 24, 313-325. 10.1038/nm.4490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone, R., Balendra, R., Moens, T. G., Preza, E., Wilson, K. M., Heslegrave, A., Woodling, N. S., Niccoli, T., Gilbert-Jaramillo, J., Abdelkarim, S.et al. (2018). G-quadruplex-binding small molecules ameliorate C9orf72 FTD/ALS pathology in vitro and in vivo. EMBO Mol Med 10, 22-31. 10.15252/emmm.201707850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong, M. J., Abrahams, S., Goldstein, L. H., Woolley, S., McLaughlin, P., Snowden, J., Mioshi, E., Roberts-South, A., Benatar, M., HortobaGyi, T.et al. (2017). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis - frontotemporal spectrum disorder (ALS-FTSD): Revised diagnostic criteria. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 18, 153-174. 10.1080/21678421.2016.1267768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z., Zhang, Y., Gendron, T. F., Bauer, P. O., Chew, J., Yang, W. Y., Fostvedt, E., Jansen-West, K., Belzil, V. V., Desaro, P.et al. (2014). Discovery of a biomarker and lead small molecules to target r(GGGGCC)-associated defects in c9FTD/ALS. Neuron 83, 1043-1050. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan, A., Bouffard, M., Liao, M., Ryan, S., Callister, J. B., Pickering-Brown, S. M., Armstrong, G. A. B. and Drapeau, P. (2018). Expression of C9orf72-related dipeptides impairs motor function in a vertebrate model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 1754-1762. 10.1093/hmg/ddy083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Z., Wang, H., Xia, Q., Li, K., Li, K., Jiang, X., Xu, G., Wang, G. and Ying, Z. (2015). Nucleolar stress and impaired stress granule formation contribute to C9orf72 RAN translation-induced cytotoxicity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 2426-2441. 10.1093/hmg/ddv005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Blitterswijk, M., DeJesus-Hernandez, M., Niemantsverdriet, E., Murray, M. E., Heckman, M. G., Diehl, N. N., Brown, P. H., Baker, M. C., Finch, N. A., Bauer, P. O.et al. (2013). Association between repeat sizes and clinical and pathological characteristics in carriers of C9ORF72 repeat expansions (Xpansize-72): a cross-sectional cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 12, 978-988. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70210-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mossevelde, S., van der Zee, J., Cruts, M. and Van Broeckhoven, C. (2017). Relationship between C9orf72 repeat size and clinical phenotype. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 44, 117-124. 10.1016/j.gde.2017.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatsavayai, S. C., Yoon, S. J., Gardner, R. C., Gendron, T. F., Vargas, J. N., Trujillo, A., Pribadi, M., Phillips, J. J., Gaus, S. E., Hixson, J. D.et al. (2016). Timing and significance of pathological features in C9orf72 expansion-associated frontotemporal dementia. Brain 139, 3202-3216. 10.1093/brain/aww250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinueza Veloz, M. F., Buijsen, R. A., Willemsen, R., Cupido, A., Bosman, L. W., Koekkoek, S. K., Potters, J. W., Oostra, B. A. and De Zeeuw, C. I. (2012). The effect of an mGluR5 inhibitor on procedural memory and avoidance discrimination impairments in Fmr1 KO mice. Genes Brain Behav. 11, 325-331. 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2011.00763.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinueza Veloz, M. F., Zhou, K., Bosman, L. W., Potters, J. W., Negrello, M., Seepers, R. M., Strydis, C., Koekkoek, S. K. and De Zeeuw, C. I. (2015). Cerebellar control of gait and interlimb coordination. Brain Struct. Funct. 220, 3513-3536. 10.1007/s00429-014-0870-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite, A. J., Baumer, D., East, S., Neal, J., Morris, H. R., Ansorge, O. and Blake, D. J. (2014). Reduced C9orf72 protein levels in frontal cortex of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal degeneration brain with the C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 1779.e5 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen, X., Tan, W., Westergard, T., Krishnamurthy, K., Markandaiah, S. S., Shi, Y., Lin, S., Shneider, N. A., Monaghan, J., Pandey, U. B.et al. (2014). Antisense proline-arginine RAN dipeptides linked to C9ORF72-ALS/FTD form toxic nuclear aggregates that initiate in vitro and in vivo neuronal death. Neuron 84, 1213-1225. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westergard, T., McAvoy, K., Russell, K., Wen, X., Pang, Y., Morris, B., Pasinelli, P., Trotti, D. and Haeusler, A. (2019). Repeat-associated non-AUG translation in C9orf72-ALS/FTD is driven by neuronal excitation and stress. EMBO Mol Med. 11, e9423 10.15252/emmm.201809423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woollacott, I. O. and Rohrer, J. D. (2016). The clinical spectrum of sporadic and familial forms of frontotemporal dementia. J. Neurochem. 138 Suppl. 1, 6-31. 10.1111/jnc.13654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa, M., Ito, D., Honda, T., Kubo, K., Noda, M., Nakajima, K. and Suzuki, N. (2015). Characterization of the dipeptide repeat protein in the molecular pathogenesis of c9FTD/ALS. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 1630-1645. 10.1093/hmg/ddu576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D., Abdallah, A., Li, Z., Lu, Y., Almeida, S. and Gao, F. B. (2015). FTD/ALS-associated poly(GR) protein impairs the Notch pathway and is recruited by poly(GA) into cytoplasmic inclusions. Acta Neuropathol. 130, 525-535. 10.1007/s00401-015-1448-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamiri, B., Reddy, K., Macgregor, R. B., Jr. and Pearson, C. E. (2014). TMPyP4 porphyrin distorts RNA G-quadruplex structures of the disease-associated r(GGGGCC)n repeat of the C9orf72 gene and blocks interaction of RNA-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 4653-4659. 10.1074/jbc.C113.502336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K., Donnelly, C. J., Haeusler, A. R., Grima, J. C., Machamer, J. B., Steinwald, P., Daley, E. L., Miller, S. J., Cunningham, K. M., Vidensky, S.et al. (2015). The C9orf72 repeat expansion disrupts nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature 525, 56-61. 10.1038/nature14973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. J., Gendron, T. F., Grima, J. C., Sasaguri, H., Jansen-West, K., Xu, Y. F., Katzman, R. B., Gass, J., Murray, M. E., Shinohara, M.et al. (2016). C9ORF72 poly(GA) aggregates sequester and impair HR23 and nucleocytoplasmic transport proteins. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 668-677. 10.1038/nn.4272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. J., Gendron, T. F., Ebbert, M. T. W., O'Raw, A. D., Yue, M., Jansen-West, K., Zhang, X., Prudencio, M., Chew, J., Cook, C. N.et al. (2018). Poly(GR) impairs protein translation and stress granule dynamics in C9orf72-associated frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Med. 24, 1136-1142. 10.1038/s41591-018-0071-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. J., Guo, L., Gonzales, P. K., Gendron, T. F., Wu, Y., Jansen-West, K., O'Raw, A. D., Pickles, S. R., Prudencio, M., Carlomagno, Y.et al. (2019). Heterochromatin anomalies and double-stranded RNA accumulation underlie C9orf72 poly(PR) toxicity. Science 363, eaav2606 10.1126/science.aav2606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q., Mareljic, N., Michaelsen, M., Parhizkar, S., Heindl, S., Nuscher, B., Farny, D., Czuppa, M., Schludi, C., Graf, A.et al. (2019). Active poly-GA vaccination prevents microglia activation and motor deficits in a C9orf72 mouse model. EMBO Mol. Med. 12, e10919 10.15252/emmm.201910919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu, T., Liu, Y., Bañez-Coronel, M., Reid, T., Pletnikove, O., Lewis, J., Miller, T. M., Harms, M. B., Falchook, A. E., Subramony, S. H.et al. (2013). RAN proteins and RNA foci from antisense transcripts in C9ORF72 ALS and frontotemporal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E4968-E4977. 10.1073/pnas.1315438110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.