Data on hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas is urgently needed to guide public health policies for infection control in the community. In this retrospective cohort study, we describe the demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of the initial group of hospitalized adults with coronavirus disease 2019 at the only academic medical center in Mississippi.

Key Words: COVID-19, coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2, social determinants of health, vulnerable populations

Objectives

To describe the demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of hospitalized adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in an academic medical center in the southern United States.

Methods

Retrospective, observational cohort study of all adult patients (18 years and older) consecutively admitted with laboratory-confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 infection between March 13 and April 25, 2020 at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. All of the patients either survived to hospital discharge or died during hospitalization. Demographics, body mass index, comorbidities, clinical manifestations, and laboratory findings were collected. Patient outcomes (need for invasive mechanical ventilation and in-hospital death) were analyzed.

Results

One hundred patients were included, 53% of whom were women. Median age was 59 years (interquartile range 44–70) and 66% were younger than 65. Seventy-five percent identified themselves as Black, despite representing 58% of hospitalized patients at our institution in 2019. Common comorbid conditions included hypertension (68%), obesity (65%), and diabetes mellitus (31%). Frequent clinical manifestations included shortness of breath (76%), cough (75%), and fever (64%). Symptoms were present for a median of 7 days (interquartile range 4–7) on presentation. Twenty-four percent of patients required mechanical ventilation and, overall, 19% died (67% of those requiring mechanical ventilation). Eighty-four percent of those who died were Black. On multivariate analysis, ever smoking (odds ratio [OR] 5.9, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2–28.6) and history of diabetes mellitus (OR 5.9, 95% CI 1.5–24.3) were associated with mortality, and those admitted from home were less likely to die (vs outside facility, OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.0–0.7). Neither age, sex, race, body mass index, insurance status, nor rural residence was independently associated with mortality.

Conclusions

Our study adds evidence that Black patients appear to be overrepresented in those hospitalized with and those who die from COVID-19, likely a manifestation of adverse social determinants of health. These findings should help guide preventive interventions targeting groups at higher risk of acquiring and developing severe COVID-19 disease.

Key Points

Among the first 100 hospitalized patients with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019, 75% of hospitalizations and 84% of deaths were among Black patients, despite accounting for 58% of our established patient population and 38% of the state’s population.

In total, 24% of hospitalized adults required invasive mechanical ventilation, and 19% died.

In-hospital death was independently associated with cigarette smoking (ever) and a history of diabetes mellitus.

Infection caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the agent responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), rapidly evolved into a global pandemic. As of June 12, 2020, it has caused >7 million cases and >400,000 deaths worldwide.1 In the United States, published reports describe an array of manifestations, ranging from asymptomatic infection to severe respiratory failure resulting in death.2–6 Most COVID-19-related deaths occur in older adults and in individuals with underlying health conditions, such as diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic lung disease, and cardiovascular disease.7,8 In addition, obese patients with COVID-19 appear to have higher rates of hospitalization and critical illness.9,10 Early reports show disproportionate rates of morbidity and mortality among racial minorities, including an overrepresentation of Blacks among hospitalized patients. Understanding the correlation between risk factors for severe disease and current COVID-19 pandemic trends is of paramount importance in the southern United States due to the high prevalence of chronic medical conditions, poverty, and limited access to health care across the region. In the southern United States, nearly one in five people live in poverty.11 Both rural and urban poor, along with racial and ethnic minorities bear a disproportionate burden of chronic diseases.12 In 2017, Mississippi ranked first among US states in death rates from heart and kidney disease and demonstrated some of the highest death rates from chronic lower respiratory disease, stroke, and DM.13 Mississippians also have the highest prevalence of obesity in the United States (39.5% as of 2018).14 Furthermore, Blacks in Mississippi are more likely to be poor and have a higher prevalence of coronary heart disease, hypertension, obesity, and DM compared with Whites.15,16

Data on hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in the southern United States remain limited.8,17 More information on patients with severe disease in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas is urgently needed to inform the adequate allocation of resources and preventive interventions to benefit those most at risk for worse outcomes. Here, we aim to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized adults with COVID-19 at a large academic medical center in the southern United States.

Methods

This retrospective, observational cohort study included all consecutive adult patients (18 years and older) admitted between March 13 and April 25, 2020 at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) in Jackson, Mississippi who had a positive SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test of a nasopharyngeal specimen. UMMC is the only academic medical center in the state. In 2019, there were 27,866 adult patients discharged from UMMC (including the University Hospital, the Wiser Hospital for Women and Infants, and the Wallace R. Conerly Critical Care Hospital). Of the 26,951 who had race documented in their records, 58.2% identified as non-Hispanic Black and 40.3% identified as non-Hispanic White. The UMMC institutional review board approved the research protocol for this study.

All of the patients included in the analysis had either survived to hospital discharge or died during the index hospitalization. Data were abstracted through a review of electronic medical records, recorded using Research Electronic Data Capture software (REDCap version 9.3.3; Vanderbilt University) hosted at UMMC, and included patient demographic characteristics, preexisting medical conditions, body mass index (BMI), symptoms reported on presentation, vital signs, laboratory findings, and patient outcomes such as need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and in-hospital mortality. BMI and obesity were classified per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance.18 ZIP codes of residence were collected and stratified as urban versus rural according to the National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties.19 Many patients received treatments considered to be under investigation at the time of hospitalization (eg, hydroxychloroquine ± azithromycin, corticosteroids, tocilizumab), but given varying degrees of utilization over time, this was not included in the analysis. Neither remdesivir nor convalescent plasma was available at our institution until after the study period. No imputation was made for missing data.

The χ2 analysis was used to assess proportional differences by IMV need as well as mortality by categorical demographic/clinical characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, BMI, smoking status, insurance status, rural residence, hospital admission source, and comorbidities), and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for those continuous clinical characteristics (laboratory findings, including absolute lymphocyte count, d-dimer, ferritin, and C-reactive protein levels) as appropriate. Logistic regression was used to assess the effects of each demographic/clinical characteristic on the odds of needing IMV as well as the odds of mortality. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY).

Results

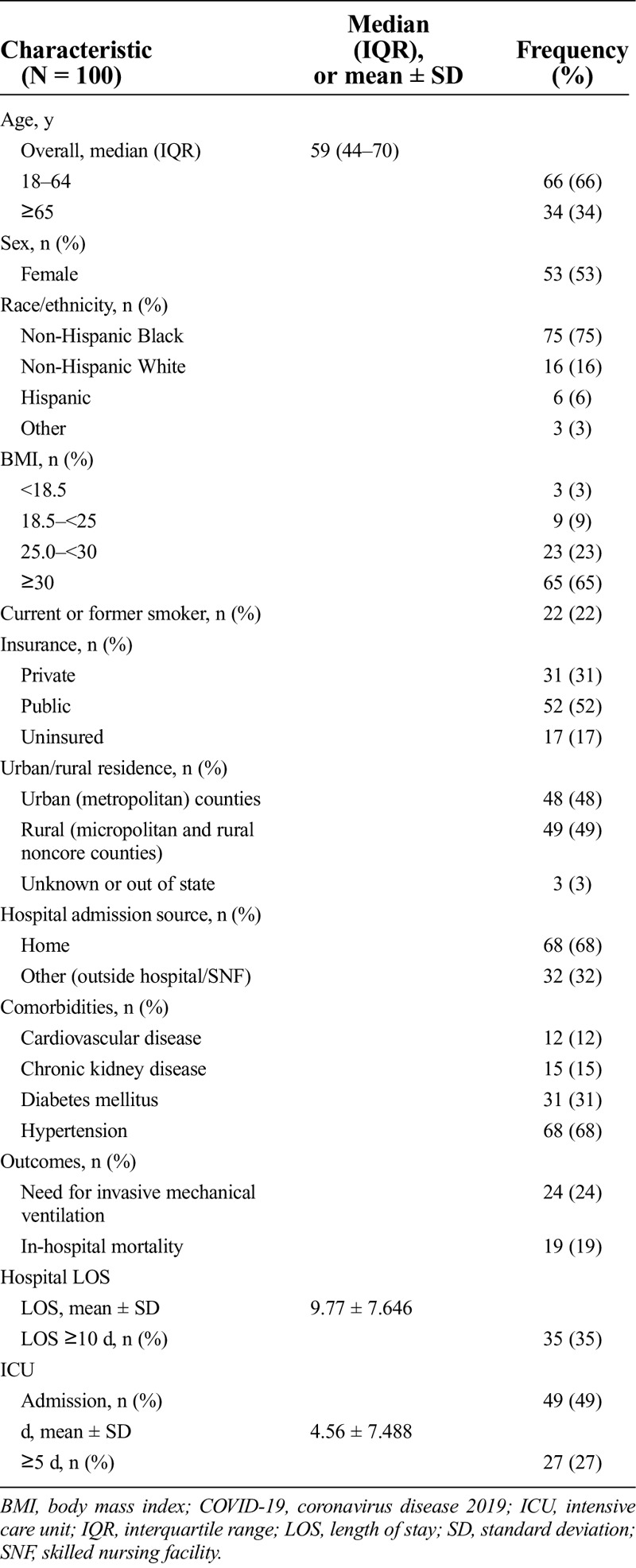

One hundred patients were included in the study, and the baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 59 years old (interquartile range [IQR] 44–70), and 66% were 64 years old or younger. Fifty-three percent were women, and 75% identified themselves as Black. Twenty-six percent of those younger than 65 years of age were uninsured, and 49% of patients resided in rural areas. Thirty-two percent of patients presented from outside facilities (including another hospital or long-term care facilities). The median BMI was 32.5 (IQR 28.0–39.1).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized COVID-19 patients

The most common comorbid conditions included hypertension (68%), obesity (65%), and DM (31%). Of those 64 years or younger, 67% (46/66) were obese, and only 3% (2/66) did not report any medical history. All of the patients older than 65 years reported comorbidities. Patients were symptomatic for a median of 7 days (IQR 4–7) before presentation, which did not differ by race. Sixty-four percent had fever documented during hospitalization, and the median temperature on presentation was 100.9°F (IQR 98.9–102). Commonly reported symptoms included shortness of breath (76%), cough (75%), and fatigue (41%). Seventy-seven percent received empiric antibiotic therapy, although none of those had a confirmed bacterial infection.

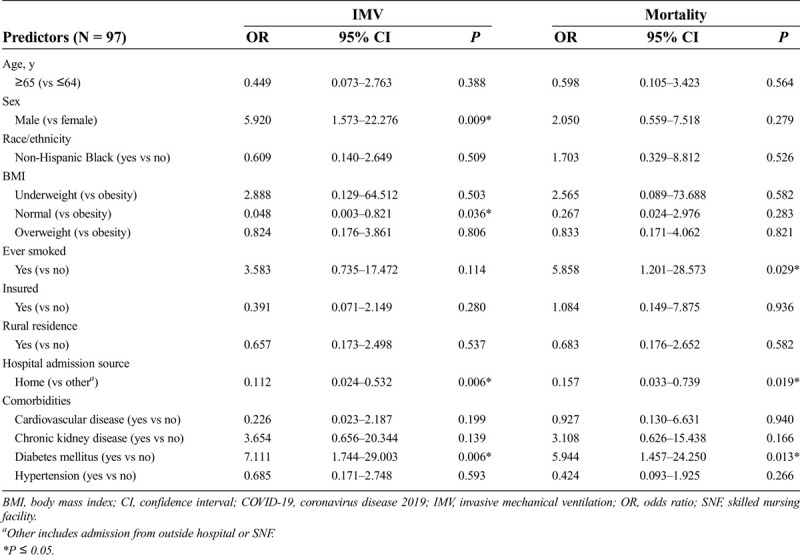

Twenty-four patients required IMV, 16 of whom died (67%). The median age of those who required IMV was 62.5 years versus 56 years of those who did not (P = 0.047). Patients who required IMV had statistically significant higher levels of lactate dehydrogenase (593 vs 348 U/L, P = 0.004), d-dimer (1418 vs 884 ng/mL, P = 0.012), and ferritin (1000 vs 675 ng/mL, P = 0.044) on admission. A higher proportion of patients requiring IMV were men (70.8% vs 39.5%, P = 0.007), had an admission from an outside facility (58.3% vs 23.7%, P = 0.002), and a history of DM (50% vs 25%, P = 0.021). Table 2 reports the independent association between the demographic/clinical characteristics and IMV. Male sex (odds ratio [OR] 5.9, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.6–22.3) and history of DM (OR 7.1, 95% CI 1.7–29.0) were statistically associated with need for IMV; however, those who were admitted from home (OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.0–0.5) and those having a BMI within normal limits (OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.0–0.8) were significantly less likely to need IMV.

Table 2.

Logistic regression association between invasive mechanical ventilation and mortality by demographic/clinical characteristics among hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Nineteen patients died during hospitalization, 16 of whom were Black (84%). The median age of those who survived was 55 years versus 64 years in those who died (P = 0.002). There were no significant differences in laboratory findings on admission between patients who died and survived. A higher proportion of patients who died during hospitalization were current or former cigarette smokers (47.4% vs 16.0%, P = 0.003), were admitted from an outside facility (57.9% vs 25.9%, P = 0.007), and had a history of chronic kidney disease (31.6% vs 11.1%, P = 0.025) or DM (57.9% vs 24.7%, P = 0.005). The independent association between the demographic/clinical characteristics and mortality is reported in Table 2. Ever smoking cigarettes (OR 5.9, 95% CI 1.2–28.6) and history of DM (OR 5.9, 95% CI 1.5–24.3) were statistically associated with in-hospital mortality; however, those who were admitted from home (OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.0–0.7) were less likely to die during their hospitalization.

Discussion

This study describes the clinical characteristics and outcomes of the first 100 patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 at the only academic medical center in Mississippi, with an overall 19% in-hospital mortality rate. Two-thirds of hospitalizations occurred in people younger than 65 years. Despite the fact that individuals of Black race represented 58% of those hospitalized at UMMC in 2019, they accounted for 75% of all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and 84% of those who died. There was no difference in the duration of symptoms at presentation by race. Shortness of breath, cough, fever, and fatigue were the most commonly identified clinical manifestations, and one of every four patients in this cohort required IMV. Male sex and history of DM were independently associated with the need for IMV. In-hospital death was significantly associated with history of cigarette smoking (current and former) and DM.

Our study shows similar demographic characteristics and outcomes in hospitalized patients than two previous reports in the southern United States. Price-Haywood et al17 described a large cohort of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patients from a large health system in Louisiana, where 40% required hospitalization (n = 1382). Of those hospitalized, 77% were Black, despite only accounting for 31% of their established patient population. Gold et al8 described data from 305 patients admitted to 8 hospitals in Georgia. Eighty-three percent of those hospitalized were Black, which was higher than expected for those hospitals, according to the authors. Despite adjustment for confounders, Black race was not associated with higher in-hospital mortality in either study, which ranged between 17% and 24%, similar to our cohort (19%).

Despite representing only 13.4% of the US population, Black patients account for 32% of COVID-19-associated hospitalizations according to the COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET).20 The state of Mississippi’s population is 38% Black, but Black patients account for >50% of both COVID-19-related cases and deaths across the state.21 Despite only representing 58% of all admissions at UMMC in 2019, Black patients in our sample made up 75% of COVID-related hospitalizations and 84% of the deaths.

The presented data highlight ongoing racial disparities among those hospitalized with COVID-19 in the southern United States, including those without factors that are known to be associated with severe illness and mortality from COVID-19. In fact, despite race not being independently associated with in-hospital mortality, in Mississippi more Blacks than Whites are dying of COVID-19.21 There are multiple proposed explanations for this finding but, in general, health differences between racial and ethnic groups often are caused by inequities grounded in structural racism and socioeconomic factors that are more prevalent among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States.22 Racial and ethnic differences that may increase the likelihood of exposure to other people with SARS-CoV-2 infection include those that are related to occupation (overrepresentation of minorities in essential and other jobs in which staying home or teleworking is not an option and lack of paid sick leave) and living conditions (living in densely populated areas; overrepresentation in jails, prisons, and detention centers). In addition, there are racial and ethnic differences that may increase the likelihood of severe disease, including the higher prevalence of serious chronic comorbidities, lack of health insurance, and inadequate access to health care.

Our study also adds to the available evidence that certain epidemiologic factors are associated with severe COVID-19. Here, DM was strongly associated with both need for IMV and death. Mississippi has one of the highest prevalence rates of DM in adults in the United States, estimated at 14.4% in 2018.23 The low-income population is disproportionally affected by DM, making disease control challenging because of limited access to health care. Male patients were more likely to need mechanical ventilation than female patients, which is consistent with other studies that have found male patients to be more at risk for worst outcomes independent of age.3,6 Patients who ever smoked (current or former) were more likely to die than those who did not. The association of smoking with disease severity and mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients remains controversial. A 2020 meta-analysis based on studies with poor-quality data found that smoking appears to modestly increase the risk of severe disease, but it was not significantly associated with increased mortality.24 Further studies using well-defined smoking history variables are needed to elucidate the role of cigarette smoking in severe COVID-19 disease and mortality.25 In this study, neither age, sex, race/ethnicity, BMI, insurance status, nor rural residence were independently associated with in-hospital mortality. Approximately half of all patients admitted resided in rural areas in a state where many rural hospitals, especially in areas with a high proportion of uninsured residents, have closed or are at risk of closing, with less availability of intensive care beds.26

In the present study, those who were admitted from home (as opposed to hospital transfers or from a long-term care facility) were less likely to need IMV and die during hospitalization. It has been well described that the congregate nature and the population served at nursing facilites has placed their residents at high risk for being affected by COVID-19.27 Those who had a normal BMI were also less likely to need IMV, which is consistent with other studies that have found that obesity appears to be a risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease and hospitalization, especially in younger individuals.9,10

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small, which is reflected in the wide 95% CIs seen in some analyzed variables. This may have affected our ability to detect other factors associated with IMV or mortality. Second, patients admitted at academic medical centers may not be representative of all of the hospitalized adults with COVID-19 in the state, because they are known to disproportionately provide care for certain populations, including uninsured patients, hospital transfer patients with complex needs, and Medicare and Medicaid patients, but also because they are able to provide broad specialty services and conduct cutting-edge research.28 Third, as these data were collected retrospectively from electronic medical records, there is the potential for incomplete documentation, which may have skewed the results.

Conclusions

This study provides valuable information regarding demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of hospitalized adults with COVID-19 in Mississippi. All 100 patients in the study either survived to discharge or died during hospitalization. Two-thirds of those hospitalized were younger than 65 years, and 25% of those did not have known underlying comorbidities, which underscores the fact that severe COVID-19 can in fact occur in generally healthy individuals of any age. We add to the available evidence that Blacks are overrepresented in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, which is likely a manifestation of the harmful influence of adverse social determinants of health. The data presented here should help guide public officials in planning focused preventive interventions targeting populations at higher risk of severe disease if infected, as in settings of limited resources such as rural areas and urban poor areas of the southern United States. Further studies are needed to better understand and modify factors contributing to the disparities unmasked by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Footnotes

L.A.M. has received compensation from Evofem, Gilead Science, Melinta, Merck, Rheonix, Roche Molecular, ViiV Heathcare|GSK, and Visby. The remaining authors did not report any financial relationships or conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Mary Joyce B. Wingler, Email: mwingler@umc.edu.

David A. Cretella, Email: dcretella@umc.edu.

Lori M. Ward, Email: lward@umc.edu.

Courtney E. Sims Gomillia, Email: cegomillia@umc.edu.

Nicholas Chamberlain, Email: nchamberlain@umc.edu.

Luis A. Shimose, Email: lshimoseciudad@umc.edu.

James B. Brock, Email: jbbrock@umc.edu.

Jessie Harvey, Email: jharvey2@umc.edu.

Andrew Wilhelm, Email: awilhelm@umc.edu.

Lance T. Majors, Email: lmajors@umc.edu.

Joshua B. Jeter, Email: jjeter@umc.edu.

Maria X. Bueno, Email: mbuenorios@umc.edu.

Svenja Albrecht, Email: salbrecht@umc.edu.

Bhagyashri Navalkele, Email: bnavalkele@umc.edu.

Leandro A. Mena, Email: lmena@umc.edu.

Jason Parham, Email: jparham@umc.edu.

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 United States cases by county. Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 tracking map. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Response Team Geographic Differences in COVID-19 Cases, Deaths, and Incidence—United States, February 12–April 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:465–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson S Hirsch JS Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA 2020;323:2052–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal P Choi JJ Pinheiro LC, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2372–2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummings MJ Baldwin MR Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1763–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrilli CM Jones SA Yang J, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2020;369:m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Response Team Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019—United States, February 12–March 28, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:382–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold JAW Wong KK Szablewski CM, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19—Georgia, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:545–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lighter J Phillips M Hochman S, et al. Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for Covid-19 hospital admission. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:896–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kass DA, Duggal P, Cingolani O. Obesity could shift severe COVID-19 disease to younger ages. Lancet 2020;395:1544–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artiga S, Damico A. Health and health coverage in the South: a data update. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/health-and-health-coverage-in-the-south-a-data-update. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- 12.Mississippi State Department of Health Health equity in Mississippi. https://msdh.ms.gov/msdhsite/_static/44,0,236.html#:~:text=Health%20Disparity%20Data&text=Many%20of%20Mississippi's%20poor%20health,populations%20having%20worse%20health%20outcomes. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics Stats of the state of Mississippi. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/states/mississippi/mississippi.htm. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps—non-Hispanic Black adults. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html#nonhispanic-black-adults. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- 15.El-sadek L Zhang L Vargas R, et al. State of the state: Annual Mississippi Health Disparities and Inequalities Report. https://msdh.ms.gov/msdhsite/index.cfm/44,8072,236,63,pdf/HealthDisparities2015.pdf. Published October 2015. Accessed January 9, 2021.

- 16.The Kaiser Family Foundation State health facts. Poverty Rate by Race/Ethnicity. 2018. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-raceethnicity. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 17.Price-Haywood EG Burton J Fort D, et al. Hospitalization and mortality among Black patients and White patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2534–2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity Defining adult overweight and obesity. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics 2013 NCHS urban-rural classification scheme for counties. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network, COVID-NET. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covid-net/purpose-methods.html. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- 21.Mississippi State Department of Health COVID-19 in Mississippi. https://msdh.ms.gov/msdhsite/_static/14,0,420.html#Mississippi. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 Health equity considerations and racial and ethnic minority groups. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fneed-extra-precautions%2Fracial-ethnic-minorities.html. Accessed January 9, 2021.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Population Health BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data [online]. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/. Accessed February 01, 2021.

- 24.Karanasos A Aznaouridis K Latsios G, et al. Impact of smoking status on disease severity and mortality of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res 2020;22:1657–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallus S, Lugo A, Gorini G. No double-edged sword and no doubt about the relation between smoking and COVID-19 severity. Eur J Intern Med 2020;77:33–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosley D, DeBehnke D. Rural hospital sustainability: new analysis shows worsening situation for rural hospitals, residents. https://guidehouse.com/-/media/www/site/insights/healthcare/2019/navigant-rural-hospital-analysis-22019.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- 27.Fallon A Dukelow T Kennelly SP, et al. COVID-19 in nursing homes. QJM 2020;113:391–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleishon HB Itri JN Boland GW, et al. Academic medical centers and community hospitals integration: trends and strategies. J Am Coll Radiol 2017;14:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]