Abstract

Background

In the United States, surveillance of norovirus gastroenteritis is largely restricted to outbreaks, limiting our knowledge of the contribution of sporadic illness to the overall impact on reported outbreaks. Understanding norovirus transmission dynamics is vital for improving preventive measures, including norovirus vaccine development.

Methods

We analyzed seasonal patterns and genotypic distribution between sporadic pediatric norovirus cases and reported norovirus outbreaks in middle Tennessee. Sporadic cases were ascertained via the New Vaccine Surveillance Network in a single county, while reported norovirus outbreaks from 7 middle Tennessee counties were included in the study. We investigated the predictive value of sporadic cases on outbreaks using a 2-state discrete Markov model.

Results

Between December 2012 and June 2016, there were 755 pediatric sporadic norovirus cases and 45 reported outbreaks. Almost half (42.2%) of outbreaks occurred in long-term care facilities. Most sporadic cases (74.9%) and reported outbreaks (86.8%) occurred between November and April. Peak sporadic norovirus activity was often contemporaneous with outbreak occurrence. Among both sporadic cases and outbreaks, GII genogroup noroviruses were most prevalent (90.1% and 83.3%), with GII.4 being the dominant genotype (39.0% and 52.8%). The predictive model suggested that the 3-day moving average of sporadic cases was positively associated with the probability of an outbreak occurring.

Conclusions

Despite the demographic differences between the surveillance populations, the seasonal and genotypic associations between sporadic cases and outbreaks are suggestive of contemporaneous community transmission. Public health agencies may use this knowledge to expand surveillance and identify target populations for interventions, including future vaccines.

Keywords: norovirus, surveillance, sporadic, outbreak, gastroenteritis

Data from 2 demographically distinct surveillance populations were analyzed to describe norovirus epidemiology within middle Tennessee. The temporal and genotypic characteristics of sporadic norovirus in a pediatric population were reflective of those among reported outbreaks in the greater region.

Norovirus is the leading cause of acute gastroenteritis (AGE) in the United States, causing an estimated 19–21 million illnesses each year [1]. Illness is typically self-limited and characterized by vomiting and diarrhea. Prolonged symptoms can lead to severe dehydration and even death in rare cases. Norovirus affects all age groups in the population. However, severe illness is more likely to occur in vulnerable populations such as young children, immunocompromised individuals, and the elderly [2, 3].

Transmission of norovirus is primarily fecal–oral by person-to-person contact or contaminated food and water. Fomites and aerosolized viral particles from vomitus also contribute to spread [2, 3]. The ease of transmission, short incubation period of 12–48 hours [2, 4], and low infectious dose [5] make norovirus a rapidly spreading virus, causing community-wide illness and disease outbreaks. In the United States, 71% of reported outbreaks occur in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) [6] but can also occur in a variety of settings such as restaurants, schools, and childcare facilities. While outbreaks occur throughout the year, norovirus activity is generally increased from November through April [7].

In the United States, national surveillance of norovirus is primarily restricted to outbreaks rather than sporadic illness. However, increased availability of multienteric pathogen testing, which includes norovirus, in clinical settings has made sporadic norovirus surveillance more feasible in the future [8, 9]. In Tennessee, AGE outbreaks are identified and investigated by local health agencies and the Tennessee Department of Health (TDH). Epidemiologic details of these outbreaks are then entered into the National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS), which is administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [10]. While all AGE outbreaks are required to be reported in Tennessee, surveillance is passive and relies heavily on reporting by individuals and institutions such as healthcare facilities, restaurants, and schools. TDH also participates in CaliciNet and NoroSTAT to more fully characterize the temporal and genotypic aspects of norovirus outbreaks in near real-time for national surveillance [6, 11].

In contrast to outbreak reporting, the New Vaccine Surveillance Network (NVSN) conducts active surveillance for medically attended AGE in children through a network of sentinel pediatric hospitals [12]. Data from NVSN have previously shown that following the introduction of rotavirus vaccines, norovirus became the leading cause of medically attended AGE in the pediatric population [13]. Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) has been part of this active surveillance system and captures patients from Davidson County, Tennessee, from the inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department (ED) settings.

Transmission dynamics between sporadic norovirus illness in the community and outbreaks are not well described but have important implications for the implementation of preventative measures, such as candidate vaccines currently under development [14, 15]. Thus, for this study, we compared sporadic pediatric norovirus ascertained via NVSN with reported outbreaks in Davidson and 6 surrounding counties in middle Tennessee. Temporal, genotypic, and predictive analyses were performed to describe associations between temporally and geographically similar but distinct sources of norovirus data.

METHODS

Active Surveillance NVSN

Active surveillance of pediatric inpatient, ED, and outpatient norovirus cases occurred at VUMC Monroe Carrell Jr. Children’s Hospital. Surveillance was conducted between 1 December 2012 and 30 June 2016 for Davidson County residents who presented with diarrhea (≥3 stools in a 24-hour period) and/or vomiting (≥1 episode in a 24-hour period). Enrolled and consented children were aged <18 years in the ED and outpatient clinics and <11 years in the inpatient setting. All patients were immunocompetent and had no other noninfectious explanation for their symptoms.

Outbreak Surveillance TDH

TDH conducted routine outbreak surveillance during the same time frame. An outbreak was defined as 2 or more AGE cases linked by a mutual exposure or setting [16]. Confirmed norovirus outbreaks had 2 or more laboratory-confirmed positive stool samples. Suspect norovirus outbreaks had less than 2 norovirus-positive stool samples and were determined by TDH to likely be attributed to norovirus based on having more than 50% of cases report vomiting and an average illness duration of 12–60 hours. Only outbreaks where the primary exposure occurred in Davidson or the surrounding counties (Robertson, Sumner, Wilson, Rutherford, Williamson, and Cheatham) were included in the analysis.

Stool Sample Testing

Stool samples for NVSN AGE surveillance were collected within 10 days of enrollment. These and reported outbreak samples were tested at TDH Public Health Laboratory for norovirus using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). NVSN samples also were tested for rotavirus using enzyme immunoassay and using RT-qPCR for sapovirus and astrovirus [17]. Norovirus genotyping was conducted on positive samples using the laboratory protocol previously described [11]. Only NVSN patients who met the eligibility criteria and had a norovirus-positive stool sample were included in the comparative analyses to norovirus outbreaks.

Comparative Descriptive Analyses

Sporadic case demographics and outbreak characteristics that included age, gender, race, ethnicity, screening location, transmission type, outbreak location, and outbreak setting were described and compared. Seasonal trends and norovirus genotypes were compared between sporadic cases and outbreak populations graphically and using the Pearson χ2 test or Fisher exact test where appropriate. The winter norovirus season was defined as November through April to describe seasonal differences. The patient’s hospital admission date or enrollment date for the ED and outpatient clinic was used to characterize sporadic cases, and the first date of illness onset was used for outbreaks. RT-qPCR results were used to differentiate sporadic cases and outbreaks into 1 of 4 genogroup categories: GI only, GI and GII (if both genogroups were present in the same sporadic case sample), GII only, or indeterminate. The indeterminate category consisted of outbreaks where genogroup and genotype data were unavailable due to insufficient stool sample availability for laboratory testing. GII noroviruses were further classified into 3 mutually exclusive subgroups according to sequence-based genotyping: GII.4, non-GII.4, and GII untypeable. GII samples with an identified GII.4 genotype were classified as GII.4, while all other GII samples with identifiable genotypes were classified as non-GII.4. GII samples without conclusive genotype results were classified as GII untypeable.

Prediction Model Design

To study the temporal association between outbreak occurrence and sporadic cases, the data were first split into training (1 December 2012 through 30 December 2015) and testing (1 January 2016 through 30 June 2016) samples. We modeled the probability of a norovirus outbreak in middle Tennessee using a 2-state discrete time Markov model. This model assumed that the probability of an outbreak on a given day was a function of whether there was an outbreak on the previous day, the moving average of sporadic cases from the previous 3 days, and a nonlinear seasonal trend fit using a generalized additive model. This model was selected among 3 models with 1-, 3-, and 7-day moving averages of sporadic case counts by minimizing Akaike’s information criterion. We assessed the Markov assumption by testing for the addition of a 2-day lag for outbreaks. A receiver operating characteristic curve and area under the curve (AUC) were used to evaluate model performance in the training and testing samples. Inpatient cases were excluded from the model population to limit confounding differences in norovirus transmission dynamics that may occur between inpatient and outpatient groups.

Analyses were conducted using SAS software, Version 9.4, of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute Inc), R (3.5.1), and mgcv in R (3.5.1) [18, 19]. Approval for the NVSN study was obtained from the institutional review boards at Vanderbilt University, TDH, and the CDC.

RESULTS

During the study period, 3273 (52%) of the 6308 eligible patients were enrolled and had stool specimens collected and tested. Norovirus was detected in 755 (23.0%) samples, 81 (10.7%) of which had codetection with 1 or more other viral pathogens. Among sporadic pediatric norovirus cases, 54.7% were seen in the ED, 37.6% in outpatient clinics, and 7.7% admitted as inpatients (Table 1). The mean age was 2.9 years, with 81.3% of cases aged <5 years. Patients had near equal gender distributions. Approximately two-thirds of patients were white, and 54.0% of all patients were non-Hispanic or non-Latino. Almost one-third (30.0%) reported attending childcare facilities.

Table 1.

New Vaccine Surveillance Network Sporadic Norovirus Case Demographics, 1 December 2012–30 June 2016

| Demographics | Sporadic Cases (%) n = 755 |

|---|---|

| Screening location | |

| Emergency department | 413 (54.7) |

| Outpatient clinic | 284 (37.6) |

| Inpatient unit | 58 (7.7) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 384 (50.9) |

| Male | 371 (49.1) |

| Age range, y | |

| <1 | 228 (30.2) |

| 1–4 | 386 (51.1) |

| 5–17 | 141 (18.7) |

| Race | |

| White | 481 (63.7) |

| Black | 207 (27.5) |

| Other | 57 (7.5) |

| Unknown | 10 (1.3) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 345 (45.7) |

| Non-Hispanic or non-Latino | 408 (54.0) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.3) |

Forty-five norovirus outbreaks involving 1924 people were reported during the study period, of which 28 (62.2%) were laboratory-confirmed. Davidson County reported the greatest number of norovirus outbreaks (57.8%), while Robertson and Cheatham counties did not report any during the study time frame (Figure 1). Person-to-person and foodborne transmission were reported in 80.0% and 8.9% of outbreaks, respectively (Table 2). Outbreaks occurred most frequently in LTCFs (42.2%), followed by childcare facilities (8.9%) and restaurants (8.9%). In 8.9% of outbreaks, the setting was unknown or unspecified. Among all reported outbreak cases, 928 (61.6%) of 1507 individuals who reported gender were female. Age was reported for 740 outbreak associated cases. Among these, only 45 (6.1%) were aged <5 years and 309 (41.8%) were aged >75 years.

Figure 1.

Map of county locations of 45 norovirus outbreaks that occurred in middle Tennessee from December 2012 through June 2016.

Table 2.

Norovirus Outbreak Characteristics, 1 December 2012–30 June 2016

| Characteristic | Outbreaks (%) n = 45 |

|---|---|

| Mode of transmission | |

| Person-to-person | 36 (80.0) |

| Food | 4 (8.9) |

| Unknown/Other | 4 (8.9) |

| Environmental | 1 (0.2) |

| Outbreak setting | |

| Long-term care facility | 19 (42.2) |

| Other | 9 (20.0) |

| Childcare | 4 (8.9) |

| Restaurant | 4 (8.9) |

| Hotel/Motel | 3 (6.7) |

| Hospital | 2 (4.4) |

| Unknown | 4 (8.9) |

| Affected Individuals (%) n = 1924 | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 928 (48.2) |

| Male | 579 (30.0) |

| Unknown | 417 (21.7) |

| Age range, y | |

| <1 | 13 (0.7) |

| 1–4 | 32 (1.7) |

| 5–19 | 56 (2.9) |

| 20–49 | 183 (9.5) |

| 50–74 | 147 (7.6) |

| 75+ | 309 (16.1) |

| Unknown | 1184 (61.5) |

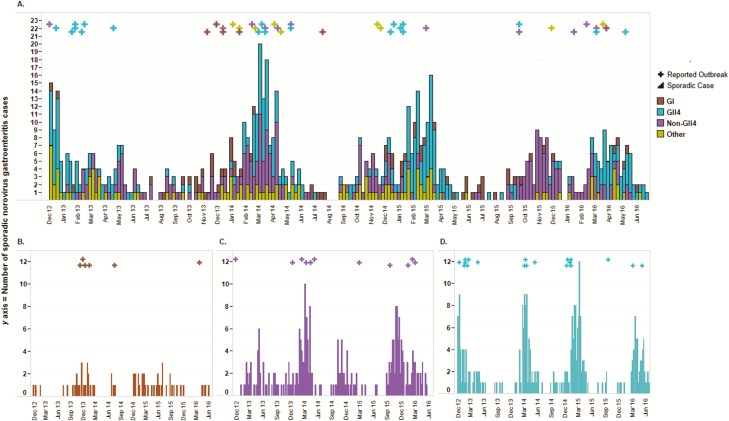

Sporadic cases and outbreaks of norovirus AGE had closely matched temporal distributions. Figure 2A demonstrates norovirus outbreak occurrence and corresponding periods of increased sporadic norovirus activity. This occurrence was consistent for GII.4, non-GII.4, and GI noroviruses (Figure 2B–D). Three-fourths (75.0%) of sporadic cases and 86.7% of outbreaks occurred during winter norovirus seasons. The 2013–2014 winter norovirus season was the most active, with 23.6% of all sporadic cases and 35.6% of norovirus outbreaks occurring during that time (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Weekly counts of sporadic cases and reported outbreaks of norovirus gastroenteritis in middle Tennessee from December 2012 through June 2016. A, All sporadic cases and outbreaks; B, Genogroup GI norovirus-positive sporadic cases and outbreaks; C, Genotype non–GII.4-positive sporadic cases and outbreaks; and D, Genotype GII.4-positive sporadic cases and outbreaks. Sporadic cases are represented by bars and outbreaks are represented by crosses at the week the first case became symptomatic.

Table 3.

Year-to-Year Seasonal Onset of Sporadic Norovirus Cases and Outbreaks

| Season | Sporadic Cases (%) n = 755 | Outbreaks (%) n = 45 |

|---|---|---|

| December 2012–April 2013a | 108 (14.3) | 8 (17.8) |

| May 2013–October 2013 | 53 (7.0) | 0 |

| November 2013–April 2014 | 178 (23.6) | 16 (35.6) |

| May 2014–October 2014 | 54 (7.2) | 3 (6.7) |

| November 2014–April 2015 | 161 (21.3) | 8 (17.8) |

| May 2015–October 2015 | 55 (7.3) | 2 (4.4) |

| November 2015–April 2016 | 119 (15.8) | 7 (15.6) |

| May 2016–June 2016 | 27 (3.6) | 1 (2.2) |

aAlthough the 2012 winter season began in November, New Vaccine Surveillance Network data collection did not begin until December 2012.

Norovirus-positive specimens were genotyped in 36 (80%) reported outbreaks and for all sporadic cases. The preponderance of genotyped specimens from both sporadic cases (90.1%) and outbreaks (83.3%) were GII, and the most frequently detected genotype was GII.4, identified in 39.1% and 52.8% of sporadic cases and outbreaks, respectively (Table 4). Further evaluation of non-GII.4 events showed that the GII.3 genotype was most prevalent among both sporadic cases and outbreaks (36.6% and 45.5%, respectively). GII.6 was the second most common genotype among sporadic cases (18.5%), while GII.13 was the second most common genotype among outbreaks (18.2%). Among all sporadic cases, genogroup and genotype categories were significantly associated with winter vs summer seasonal onset (P < .001). The proportion of sporadic cases infected with GII noroviruses was significantly higher in the winter than in the summer. This pattern was recapitulated among reported outbreaks. There were no significant differences between the proportion of winter and summer sporadic cases and reported outbreaks caused by the GI noroviruses.

Table 4.

Norovirus Genogroup and Genotype Results of Sporadic Cases and Outbreaks by Seasonal Onset

| Sporadic Cases (%) n = 755 | Outbreaks (%) n = 45 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genogroups and Genotypes | Winter (November—April) | Summer (May—October) | P Valuea | Winter (November—April) | Summer (May—October) | P Valuea |

| GI | 38 (56.7) | 29 (43.3) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | ||

| GI and GII | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | 0 | 0 | ||

| GII.4 | 246 (83.3)b | 49 (16.7) | 16 (84.2)c | 3 (15.8) | ||

| Non-GII.4 | 181 (68.3)b | 84 (31.7) | 9 (81.8)c | 2 (18.2) | ||

| GII untypeable | 95 (79.2) | 25 (20.8) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 9 (100) | 0 | |||

| Indeterminate | ||||||

| <.001 | >.05 |

aIndicates statistical significance of the χ2or Fisher exact test between genogroup and genotype classification and seasonal onset of surveillance case type (sporadic case or reported outbreak).

b P < .01.

c P < .05.

Training data for the predictive model consisted of 695 sporadic cases and 38 outbreaks from 1 December 2012 through 30 December 2015. The best fit model included an outbreak component with a 1-day lag (P = .182, Z = 1.33), a sporadic component with a moving average of 3 days (P = .015, Z = 2.44), and a seasonal smoothing effect component (P = .038, χ2 = 8.41, degrees of freedom = 3; Figure 3). The predictive model was tested using 98 sporadic cases and 7 outbreak occurrences from 1 January 2016 through 30 June 2016. Prediction accuracy of the model with the testing data had AUC = 0.5 indicating near chance performance.

Figure 3.

Estimated probability of a norovirus gastroenteritis outbreak using a 2-state discrete time Markov model compared with actual reported outbreaks between December 2012 and December 2015.

DISCUSSION

We found statistically significant temporal and genotypic correlations between medically attended norovirus cases in a pediatric population (NVSN) and norovirus outbreaks primarily among older adults (NORS) in a common geographic area of middle Tennessee. These ecologic associations by time, space, and genotype lend further evidence to the hypothesis that seasonal peaks in pediatric norovirus transmission contribute to or are associated with outbreaks in the wider community.

Increased frequency of norovirus cases among sporadic cases aged <5 years compared with other age groups is consistent with other studies [20]. On the other hand, norovirus outbreaks in Davidson County and the surrounding 6 counties predominantly affected people aged >50 years (61.6% of 740 outbreak cases with reported ages), and most (42%) of these outbreaks occurred in LTCFs, consistent with nationwide trends [11]. Despite these differences in the surveillance population demographics, outbreaks and peaks of sporadic norovirus disease appear to be temporally associated, most likely due to the fact that norovirus was in the community and affects all ages. Relatively few outbreaks were noted in childcare settings, while 30% of sporadic norovirus patients reported childcare attendance. Therefore, further investigation is needed to determine if underreporting of outbreaks in childcare settings exists and/or if illness policies prevent outbreaks.

Genotypic and temporal commonalities were evident between the sporadic cases and reported outbreaks. GII noroviruses were most prevalent among both sporadic cases and reported outbreaks, and they were significantly more likely to occur in the winter. The predominance of GII.4 norovirus in reported outbreaks is consistent with global and US trends in the same period [11, 21]. Year-to-year seasonal trends of norovirus activity were similar between sporadic cases and outbreaks. As anticipated, sporadic cases and outbreaks were most common in the winter norovirus season among GII.4 and non-GII.4 genotypes. In contrast, GI noroviruses did not show significant seasonality. This is consistent with previous reports of GI noroviruses being more strongly associated with foodborne [11] and waterborne transmission [22] due to their decreased environmental stability and lower shedding rates, as compared to GII noroviruses [23]. These features make GI noroviruses less likely to spread via person-to-person transmission and contribute to winter outbreaks in confined settings. Variation was observed year-to-year, with the most active season being November 2013 through April 2014 for both sporadic cases and outbreaks. Similar temporal associations were observed when these data were graphically displayed, with outbreaks clustered during the peak periods of sporadic norovirus case ascertainment for each of the common genogroups and genotypes. These temporal associations are suggestive of the predictive value of sporadic case prevalence on outbreak occurrences.

Rapid, multipathogen diagnostic panels that include norovirus are increasingly common in US clinical laboratories [8]. These routine test results could potentially be harnessed by public health officials to quickly detect peaks in norovirus transmission in order to forecast norovirus outbreaks in the wider community. To evaluate our hypothesis, we developed a 2-state discrete time Markov model utilizing the sporadic surveillance data to indicate the likelihood of an outbreak. The association of the sporadic case moving average with outbreak occurrence suggests the compared datasets may be capturing similar features of underlying norovirus activity in the region. However, limited outbreak data contributed to the low predictive accuracy of the model and limited sensitivity to estimate prediction accuracy in the testing data, precluding it from functional use at this time. Future studies with more robust outbreak data may be able to further evaluate the value of clinical sporadic norovirus cases for the prediction of outbreaks in a community. Similarly, while our study was limited to available pediatric surveillance data, sporadic surveillance of the general population may further enhance the predictive value of sporadic cases on outbreaks. This has relevance as an “early warning system” for public health agencies and may aid officials in developing novel, pathogen-specific prevention strategies. These may include educational interventions on hand hygiene and targeted prevention messaging to settings where norovirus outbreaks most commonly occur, such as LTCFs and other healthcare settings with vulnerable populations [2, 24, 25].

Our study has a unique strength of having active AGE surveillance being conducted in the same geographic area as reported AGE outbreaks, multiple years of data, and large samples sizes in the sporadic surveillance system. However, there are several limitations to this comparative study. First, both surveillance systems were operated independently with different objectives. We included a larger catchment area for outbreaks to account for regional commuting, which is common in middle Tennessee [26], that may result in being exposed to norovirus in a county that differs from that of a patient’s residence. Because outbreaks are reported by healthcare facilities and individuals, it is likely that the outbreak data are an underestimation of the true occurrence of outbreaks. This was a limitation of the descriptive analyses, as well as the predictive model performance. Additionally, we were unable to match patients between the 2 data sources. Importantly, of the outbreaks that we did have age data for, only 101 (13.6%) individuals were aged <19 years, suggesting minimal overlap between the outbreak and the pediatric sporadic surveillance populations. It is also notable that although almost one-third of sporadic cases reported childcare attendance, there were only 4 (8.9%) reported outbreaks in childcare settings. This may indicate underreporting of outbreaks in these settings compared with LTCFs and other healthcare settings. Last, while specific genotypes were identified for sporadic cases and outbreaks in the non-GII.4 group, the small outbreak sample size limited the ability to stratify by genotype and evaluate meaningful comparisons between the sporadic cases and outbreaks.

Despite these limitations, our study showed distinct genotypic and temporal similarities between sporadic pediatric norovirus and reported outbreaks. Further investigation into the population transmission dynamics may elucidate the timeline of the spread between different age groups and facility types within the community. Data from this study might also be relevant to vaccine development and administration planning. Enhancing information on sporadic norovirus cases and their influence on outbreaks can be valuable in identifying and supporting a target population for norovirus vaccines under development [14]. Model-based analyses suggest that vaccinating children aged <5 years provides the opportunity to divert the most cases [27]. Our findings that demonstrate the temporal and genotypic interrelationships between pediatric sporadic norovirus cases and outbreaks in the same geographic region support the proposed impact of childhood vaccination on reducing the community burden of norovirus disease. Furthermore, this association highlights the importance of simultaneous active AGE and outbreak surveillance in which the data can be used to discover opportunities to reduce the risk for sporadic illnesses and outbreaks.

Notes

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Financial support. This work was supported by the CDC Cooperative (44 U01IP001064, UL1 TR000445) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science/National Institutes of Health and the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (U01 IP001063–03).

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1. Hall AJ, Lopman BA, Payne DC, et al. Norovirus disease in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19:1198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Division of Viral Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases C for DC and P. Updated norovirus outbreak management and disease prevention guidelines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Graaf M, van Beek J, Koopmans MP. Human norovirus transmission and evolution in a changing world. Nat Rev Microbiol 2016; 14:421–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Atmar RL, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, et al. Norwalk virus shedding after experimental human infection. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14:1553–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Teunis PF, Moe CL, Liu P, et al. Norwalk virus: how infectious is it? J Med Virol 2008; 80:1468–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shah MP, Wikswo ME, Barclay L, et al. Near real-time surveillance of U.S. norovirus outbreaks by the norovirus sentinel testing and tracking network—United States, August 2009–July 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017; 66:185–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hall AJ, Wikswo ME, Manikonda K, Roberts VA, Yoder JS, Gould LH. Acute gastroenteritis surveillance through the National Outbreak Reporting System, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19:1305–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vinjé J Advances in laboratory methods for detection and typing of norovirus. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 53:373–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gonzalez MD, Langley LC, Buchan BW, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the xpert norovirus assay for detection of norovirus genogroups I and II in fecal specimens. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54:142–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Outbreak Reporting System. 2018. Available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/norsdashboard/. Accessed 27 December 2018.

- 11. Vega E, Barclay L, Gregoricus N, Shirley SH, Lee D, Vinjé J. Genotypic and epidemiologic trends of norovirus outbreaks in the United States, 2009 to 2013. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 52:147–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. New Vaccine Surveillance Network | Home | NVSN | CDC. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/surveillance/nvsn/index.html. Accessed 19 May 2019.

- 13. Payne DC, Vinjé J, Szilagyi PG, et al. Norovirus and medically attended gastroenteritis in U.S. children. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1121–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mattison CP, Cardemil CV, Hall AJ. Progress on norovirus vaccine research: public health considerations and future directions. Expert Rev Vaccines 2018; 17:773–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hallowell BD, Parashar UD, Hall AJ. Epidemiologic challenges in norovirus vaccine development. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018; 15:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS) Guidance. 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/NORS. Accessed 27 December 2018.

- 17. Lyman WH, Walsh JF, Kotch JB, Weber DJ, Gunn E, Vinjé J. Prospective study of etiologic agents of acute gastroenteritis outbreaks in child care centers. J Pediatr 2009; 154:253–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wood SN Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Method 2011; 73:3–36. [Google Scholar]

- 19. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2018. Available at: https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 19 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Phillips G, Tam CC, Conti S, et al. Community incidence of norovirus-associated infectious intestinal disease in England: improved estimates using viral load for norovirus diagnosis. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 171:1014–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Siebenga JJ, Vennema H, Zheng D, et al. Norovirus illness is a global problem: emergence and spread of norovirus GII.4 variants, 2001–2007. J Infect Dis 2009; 200:802–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matthews JE, Dickey BW, Miller RD, et al. The epidemiology of published norovirus outbreaks: a review of risk factors associated with attack rate and genogroup. Epidemiol Infect 2012; 140:1161–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chan MC, Sung JJ, Lam RK, et al. Fecal viral load and norovirus-associated gastroenteritis. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12:1278–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maccannell T, Umscheid CA, Agarwal RK, Lee I, Kuntz G, Stevenson KB. Guideline for the prevention and control of norovirus gastroenteritis outbreaks in healthcare settings.2011. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/norovirus-guidelines.pdf. Accessed 27 December 2018.

- 25. Cates SC, Kosa KM, Brophy JE, Hall AJ, Fraser A. Consumer education needed on norovirus prevention and control: findings from a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults. J Food Prot 2015; 78:484–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nashville 2018 Regional Economic Development Guide. Nashville: 2018 Available at: https://www.nashvillechamber.com/economic-development/data-reports/regional-stats. Accessed 25 March 2019.

- 27. Steele MK, Remais JV, Gambhir M, et al. Targeting pediatric versus elderly populations for norovirus vaccines: a model-based analysis of mass vaccination options. Epidemics 2016; 17:42–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]