Abstract

Background

The understanding the Impact of ulcerative COlitis aNd Its assoCiated disease burden on patients study [ICONIC] was a 2-year, global, prospective, observational study evaluating the cumulative burden of ulcerative colitis [UC] using the Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self-Measure [PRISM] tool that is validated to measure suffering, but has not previously been used in UC.

Methods

ICONIC enrolled unselected outpatient clinic attenders with recent-onset UC. Patient- and physician-reported outcomes including PRISM, the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire [SIBDQ], the Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9], and the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Indexes [patient: P-SCCAI; physician: SCCAI] were collected at baseline and follow-up visits every 6 months. Correlations between these measures were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Results

Overall, 1804 evaluable patients had ≥1 follow-up visit. Over 24 months, mean [SD] disease severity measured by P-SCCAI/SCCAI reduced significantly from 4.2 [3.6]/3.0 [3.0] to 2.4 [2.7]/1.3 [2.1] [p <0.0001]. Patient-/physician-assessed suffering, quantified by PRISM, reduced significantly over 24 months [p <0.0001]. P-SCCAI/SCCAI and patient-/physician-assessed PRISM showed strong pairwise correlations [rho ≥0.60, p <0.0001], although physicians consistently underestimated these disease severity and suffering measures compared with patients. Patient-assessed PRISM moderately correlated with other outcome measures, including SIBDQ, PHQ-9, P-SCCAI, and SCCAI (rho = ≤-0.38 [negative correlations] or ≥0.50 [positive correlations], p <0.0001).

Conclusions

Over 2 years, disease burden and suffering, quantified by PRISM, improved in patients with relatively early UC. Physicians underestimated burden and suffering compared with patients. PRISM correlated with other measures of illness perception in patients with UC, supporting its use as an endpoint reflecting patient suffering.

Keywords: PRISM, disease burden, quality of life

1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis [UC] is a chronic, idiopathic, progressive inflammatory bowel disorder characterised by frequent flares followed by periods of remission.1 The burden of UC extends far beyond the clinical signs and symptoms, with certain aspects of the patient’s disease affecting many other aspects of life, for example their employment opportunities, work productivity, and social interaction.2–5 There is an extensive body of literature describing the impact of UC on patient quality of life and the development of anxiety/depression.2–5 Anxiety may be caused by multiple factors, including lack of control over bodily functions, fear of disease progression and treatment, and lack of toilet access.5 In turn, these symptoms may limit employment opportunities and social and recreational activities, and such issues may contribute to depression.5 Despite the widely documented patient-reported burden of UC, physicians often underestimate the disease burden and associated suffering, and may fail to recognise issues that are important to patients.6

The understanding the Impact of ulcerative COlitis aNd Its assoCiated disease burden on patients study [ICONIC] was a global, prospective, 24-month, observational study that was initiated to evaluate the cumulative burden of UC. ICONIC is one of the largest studies to date assessing the multifaceted and cumulative burden of UC, and was designed to overcome limitations in previous studies. These include inadequate patient populations, restricted geographical reach, small number and breadth of the assessment tools applied, absence of both patient and physician perspectives, dates of study not reflecting current disease management and treatment practices, and limited duration of patient follow-up [if any].

The primary objective of ICONIC was to evaluate PRISM [Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self-Measure] as an assessment tool for perceived disease-associated suffering in patients with UC by assessing its correlation with the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease [IBD] Questionnaire [SIBDQ] and the Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9]. Our hypothesis was that such measures encompassing disease activity, functional status, illness perceptions, and depression will each contribute significantly to suffering as measured by PRISM. PRISM has been validated as a reliable method for assessing suffering in several chronic conditions, but has not previously been used in patients with UC.7–12 In addition, ICONIC investigated the multifaceted burden of disease in recently diagnosed patients with UC and compared the patient and physician perceptions of UC disease through the use of PRISM and the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index [SCCAI] tools.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and patients

ICONIC was a global, observational, prospective, 24-month, non-interventional study in patients with UC, with documented follow-up visits every 6 months [±3 months] in an outpatient setting, according to routine clinical practice. Patients were enrolled at 244 sites from 33 countries and were grouped according to the United Nations classification of economic regions: Western Europe [Austria, France, Germany], Eastern Europe [Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Ukraine], Northern Europe [Estonia, Ireland, Sweden, UK], Southern Europe [Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain], Canada [Canada], Western Asia [Israel, Kuwait, Turkey, Saudi Arabia], Africa [Egypt, South Africa], Latin America [Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico], and Japan [Japan]. Data collection started June 19, 2015 and ended May 22, 2019.

The inclusion criteria for participants were: aged ≥18 years, diagnosed with UC within the previous 36 months, speaking the language of the applicable patient questionnaire [23 languages], and having signed an authorisation form [and informed consent, where applicable] to use and disclose personal health information. As this was a non-interventional study, all eligible patients with UC attending their routine clinical visits were offered the opportunity to participate, regardless of treatment assignment or disease activity. Diagnosis of UC was confirmed by the treating physician; standardised diagnostic criteria were not defined in this observational study.

This observational, prospective study was run in compliance with local laws and regulations. Notification/submission to the responsible ethics committee, health institutions, and/or competent authorities was performed as required by local laws and regulations. Written patient authorisation to use and/or disclose anonymised health data [and informed consent where applicable] was obtained before patient inclusion.

2.2. Assessments

Demographic and disease-related data, medication, information on social/educational background, and work productivity/activity impairment were recorded. Investigator assessment of UC disease severity was measured by clinicians’ global ratings. Patients also self-assessed their disease severity.

At baseline and each follow-up clinic visit, physicians completed the PRISM, SCCAI, and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment General Health [WPAI-GH] questionnaires, and patients completed the PRISM, SIBDQ, patient-modified SCCAI [P-SCCAI], PHQ-9, and Rating Form of IBD Patient Concerns [RFIPC] questionnaires [Supplementary Figure 1, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. Translations for the questionnaires and PRISM were either obtained directly from the owner of patient-reported outcomes, the instrument website, or validated by forwards and backwards translation by a third-party vendor (ForeignExhange Translations, located in Newton, MA, USA). Physicians and patients completed PRISM separately at the same visit to avoid bias. Associated comorbidities and symptoms, extra-intestinal manifestations [EIMs], other concomitant immune-mediated diseases, and medications at each visit were evaluated by closed-form questions with predefined categories. Possible answers for EIMs and other concomitant immune-mediated diseases included ankylosing spondylitis [AS], erythema nodosum [EN], hidradenitis suppurativa, primary sclerosing cholangitis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, rheumatoid arthritis [RA], uveitis, other, or none.13 Non-specific arthralgia and arthritis were not included due to difficulty in ensuring consistent reporting across the geographical regions. Health care resource use questionnaires captured parameters including hospitalisation rates and surgery over the preceding 6 months due to UC.

2.3. Patient- and physician-reported outcome measures

The PRISM measure is based on a visual metaphor [Supplementary Figure 2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. Patients are presented with a rectangular paper sheet with a yellow disc in the bottom right corner, instructed to imagine that the sheet represents ‘your life at the moment’ and the yellow disc represents ‘yourself’. They are also given a red disc, which they are told represents ‘your UC’, and are asked, ‘please place the red disc on the sheet to show the importance of your UC in ‘your life at the moment’’. The closer the red ‘illness’ disc is to the yellow ‘self’ disc, the greater the person’s suffering.14,15 The distance between the centres of the yellow and red discs is termed the Self-Illness Separation [SIS]. The smaller the value of SIS, the greater the person’s suffering. In this study, the range of SIS was 0–9.4 cm.

SIBDQ includes 10 items scored from 1 [severe problem] to 7 [no problem at all] that capture the impact of IBD on four domains: bowel symptoms, systemic symptoms, emotional function, and social function. The total SIBDQ score is calculated as the sum of the 10 items [range: 10–70]. Higher SIBDQ scores reflect better health-related quality of life [HRQoL].16

SCCAI evaluates disease severity during the previous week by measuring bowel frequency [day], urgency of defaecation, blood in stool, bowel frequency [night], general well-being, and extra-colonic features, and the total SCCAI is calculated as the sum of these six measures [range: 0–19], with a higher score indicating greater symptom severity.17 P-SCCAI comprises 12 items, scored by the patient using different scales for the same measures.18

RFIPC is an IBD-specific questionnaire comprising questions related to the 25 most frequently reported worries/concerns reported by patients with IBD. Responses are scored on 10-cm visual analogue scales [0 cm: no worries/concerns; 10 cm: the greatest possible worries and concerns] and a mean score of all items is calculated [range: 0–10], with higher scores indicating greater worry and concern.19

PHQ-9 is a nine-item instrument for screening, diagnosing, monitoring, and measuring the severity of depression. Each item is scored from 0 [not at all] to 3 [nearly every day] and the PHQ-9 score is the sum of the nine items [range: 0–27].20

WPAI-GH is a six-item instrument, a self-report survey of impairments in work-related outcomes due to general health problems over the previous 7 days. Patients’ responses to items are used to calculate the impact of their general health on four domains: absenteeism [work time missed], presenteeism [impairment while working], overall work impairment [overall productivity loss, accounting for both absenteeism and presenteeism], and total activity impairment [impairment in non-work activities]. Scores from all domains are expressed as percentages of impairment, with lower values indicating less impairment.21 WPAI-GH only includes employed patients.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The evaluable population comprised all patients who fulfilled the study selection criteria and had ≥1 post-baseline visit. Quantitative data were presented as mean (standard deviation [SD] and median [range]). Qualitative data [eg, gender] were presented using means of frequency distributions. Calculation of percentages was based on the valid data per parameter, ie, excluding patients with missing values. Analysis by geographical region was descriptive only. P-SCCAI scores were transformed to be equivalent to the SCCAI scoring. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient [rho] was used to assess correlations at baseline and at each follow-up visit between the outcomes of patient-assessed PRISM and physician-assessed PRISM, SIBDQ, SCCAI, P-SCCAI, RFIPC, and PHQ-9, as well as the correlation between patient and physician PRISM and SCCAI scores. Statistical significance was determined using exact critical probability [p] values. For this analysis, SAS® package version 9.4 was used and all scores were treated as quantitative variables.

3. Results

3.1. Study sites and patient baseline characteristics

Overall, 1804 evaluable patients fulfilled the selection criteria and had ≥1 follow-up visit. The total number of evaluable patients at each visit [excluding patients with missing values] are shown in Supplementary Table 1, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online. In total, 244 sites participated, with Southern Europe recruiting the largest number of patients [n = 415] [Table 1]. University hospitals made up just under half of the study sites [44.7%], and >90% of sites were located in an urban setting. Most sites [86.4%] saw an average of ≤1000 patients with UC per year, and approximately 45.0% of sites saw each patient with UC ≥4 times per year.

Table 1.

Patient baseline and disease characteristics.

| Characteristic | Patients n = 1804a |

|---|---|

| Female, n [%] | 970 (53.8) |

| Age, median [range], years | 36.0 (18.0–88.0) |

| Geographic region,bn [%] | |

| Western Europe | 145 (8.0) |

| Eastern Europe | 327 (18.1) |

| Northern Europe | 150 (8.3) |

| Southern Europe | 415 (23.0) |

| Canada | 129 (7.2) |

| Western Asia | 217 (12.0) |

| Africa | 100 (5.5) |

| Latin America | 204 (11.3) |

| Japan | 117 (6.5) |

| UC physician-assessed disease severity, n [%] | |

| Mild | 673 (37.3) |

| Moderate | 667 (37.0) |

| Severe | 233 (12.9) |

| In remission | 230 (12.8) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) |

| UC patient-assessed disease severity, n [%] | |

| Mild | 614 (34.1) |

| Moderate | 665 (36.9) |

| Severe | 235 (13.0) |

| In remission | 286 (15.9) |

| Missing | 4 (0.2) |

| Duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis, n [%] | |

| <1 year | 1287 (71.4) |

| 1–3 years | 383 (21.2) |

| >3 years | 133 (7.4) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) |

| Time since diagnosis, median [range], daysc | 172.0 (-14.0–1095.0) |

| UC treatment at baseline, n [%]d | |

| 5-ASA/mesalamine | 998 (55.3) |

| Sulphasalazine | 32 (1.8) |

| Aminosalicylates | 316 (17.5) |

| Immunotherapy [azathioprine, 6-mercatopurine, methotrexate, cyclosporin, tacrolimus] | 284 (15.7) |

| Steroids [IV, oral] | 312 (17.3) |

| Biologics [TNFi and non-TNFi] | 190 (10.5) |

| Employment status, n [%] | |

| Employed/self-employed | 1139 (63.1) |

| On sick leave | 292 (16.2) |

| Sick leave related to UC [in patients on sick leave] | 191 (65.4) |

| Unemployed | 189 (10.5) |

| Unemployment related to UC [in unemployed patients] | 45 (23.8) |

| Duration of sick leave, n [% of total patients on sick leave] | n = 292 |

| <2 months | 141 (48.3) |

| ≥2 to ≤4 months | 27 (9.3) |

| >4 months | 48 (16.4) |

| Missing | 76 (26.0) |

| Duration of unemployment, n [% of total unemployed patients] | n = 189 |

| <6 months | 45 (23.8) |

| ≥6 months to ≤12 months | 28 (14.8) |

| >12 months | 78 (41.3) |

| Missing | 38 (20.1) |

| Associated immune-mediated extra-intestinal manifestations,en [%] | |

| 0 | 1510 (83.7) |

| 1 | 227 (12.6) |

| 2 | 20 (1.1) |

| 3 | 6 (0.3) |

| Missing | 41 (2.3) |

| Associated comorbid diseases and symptoms,fn [%] | |

| 0 | 968 (53.7) |

| 1–3 | 508 (28.2) |

| 4–6 | 34 (1.9) |

| 7–10 | 2 (0.1) |

| >10 | 268 (14.9) |

| Missing | 24 (1.3) |

ASA, aminosalicylic acid; IV, intravenous; n, number of patients; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor; UC, ulcerative colitis.

a21 patients were excluded from the evaluable population due to violation of the selection criteria.

bPatients were enrolled at 244 sites from 33 countries in nine regions: Western Europe [Austria, France, Germany], Eastern Europe [Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Ukraine], Northern Europe [Estonia, Ireland, Sweden, UK], Southern Europe [Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain], Canada [Canada], Western Asia [Israel, Kuwait, Turkey, Saudi Arabia], Africa [Egypt, South Africa], Latin America [Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico], Japan [Japan].

cTime since UC diagnosis (calculated as difference between date of UC diagnosis and visit date, days). The 15th day was used as the default diagnosis date; therefore, negative values can occur. All patients included in the study had a confirmed UC diagnosis before Visit 1 (baseline visit).

d n-values combined within each class of medication.

eCaptured by the physician; possible answers on the case report form included previously diagnosed with: ankylosing spondylitis, erythema nodosum, hidradenitis suppurativa, primary sclerosing cholangitis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, rheumatoid arthritis, uveitis, other, or ‘the patient has not been reported to have any extra-intestinal manifestation’.

fCaptured by the physician; possible answers on the case report form included anxiety/depression, any malignancies, cardiac abnormalities/cardiovascular disease, chronic renal disease or insufficiency, chronic pulmonary disease, cognitive dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, fatigue, low body weight <20 body mass index, polyneuropathy/neuropathy, postural hypotension, skin disease, and sleep disorders.

Of the 1804 patients with data at baseline, 53.8% [n = 970] were female and 50.1% [n = 903] of all patients had mild UC or were in remission, as assessed by the physician. Most patients (71.4% [n = 1287/1803]) had experienced symptoms for <1 year before diagnosis. Aminosalicylates were the most commonly prescribed drugs at baseline, followed by steroids and immunotherapy [Table 1]. Two-thirds (63.1% [n = 1139/1804]) of patients were employed. Sick leave was attributable to UC [patient-reported] for approximately two-thirds of patients who were on sick leave [n = 191/292], and almost one-quarter of the unemployed patients [n = 45/189] attributed their unemployment to UC [Table 1]. Patient baseline characteristics for the geographical regions are shown in Supplementary Table 2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online.

<<Table 1 near here>>

3.2. Change in patient disease characteristics from baseline to month 24

3.2.1. Hospitalisation and surgery

At baseline, 27.5% [n = 495/1799] of patients reported being admitted to hospital due to UC within the preceding 6 months. Over time, the proportion of patients hospitalised for UC in the 6 months preceding each study visit decreased to 4.0% [n = 52/1298] at the 24-month visit. Similarly, there was a concordant reduction in the number of patients with new surgeries due to UC: from 2.5% [n = 44/1794] at baseline to 1.3% [n = 17/1294] at 24 months.

3.2.2. Associated immune-mediated extra-intestinal manifestations

At baseline, 14.4% of patients [n = 253/1763] experienced ≥1 associated immune-mediated EIM [Table 1]; the most common were EN [1.3%], AS [1.3%], and RA [1.2%]. These EIMs continued to be the most frequently diagnosed during the 24-month study: 2.2% of patients were diagnosed with RA at least once, 2.0% of patients with EN at least once, and 1.8% of the patients with AS at least once until Month 24. The proportion of patients who were diagnosed with any associated immune-mediated EIM increased over time to 24.0% [n = 332/1382; Month 24].

When analysed by geographical region, numerically fewer patients in Japan were diagnosed with associated immune-mediated EIMs compared with patients in the other regions (baseline: 3.6% [n = 4/111] vs 11.4% [n = 23/201] to 19.7% [n = 29/147]; Month 24: 7.1% [7/99] vs 20.8% [33/159] to 35.0% [35/100]).

3.2.3. Associated comorbid diseases and symptoms

Overall, 45.6% [n = 812/1780] of patients were diagnosed with any associated comorbid diseases and symptoms at baseline, with a majority having one to three comorbidities [Table 1]; the most common were fatigue [27.7% of patients], anxiety/depression [24.8%], sleep disorders [20.6%], and cardiac abnormalities/cardiovascular disease [20.5%]. During the study, the proportion of patients diagnosed with any new associated comorbid diseases and symptoms at baseline at each follow-up visit remained relatively constant [range: 6.6–8.8%]. At Month 24, the most commonly diagnosed new associated comorbid diseases and symptoms since baseline were anxiety/depression (1.8% [n = 32/1804]) and fatigue (1.7% [n = 30/1804]).

The proportion of patients diagnosed with any associated comorbid diseases and symptoms at baseline was lowest in Japan compared with the other regions (19.8% [n = 23/116] vs 40.3% [n = 167/414] to 67.0% [n = 67/100]). Furthermore, the proportion of patients diagnosed with any new associated comorbid diseases and symptoms at each follow-up visit remained lower in Japan relative to the other regions [0.0–1.0% vs 2.6–17.5%].

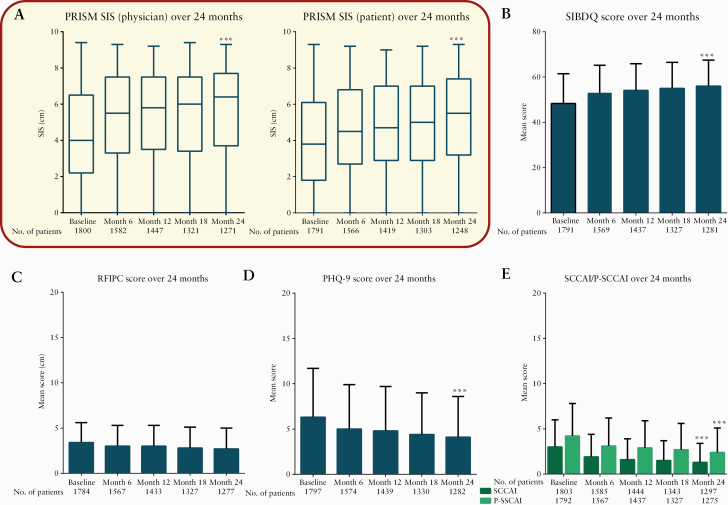

3.2.4. Pictorial representation of illness and self-measure

Compared with physician-completed PRISM scores, patients showed lower PRISM scores throughout the study, indicating that patients reported greater suffering than physicians did, and that physicians may have underestimated the severity of disease in their patients [Figure 1]. Between baseline and Month 24, the mean [SD] SIS significantly increased from 4.0 [2.5] to 5.1 [2.5] for patient-completed PRISM (mean [SD] difference of 1.2 [3.0]; p <0.0001), and from 4.3 [2.4] to 5.6 [2.4] for physician-completed PRISM (mean [SD] difference of 1.3 [2.9]; p <0.0001), with increases in SIS indicating a reduction in suffering. There was a significant difference between patient and physician mean scores at baseline (mean [SD] change difference of 0.3 [2.2]; p <0.0001) and at Month 24 (mean [SD] change difference of 0.5 [2.1]; p <0.0001). Physician- and patient-assessed PRISM scores were strongly correlated at each visit {PRISM patient vs physician: rho = 0.60 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.56–0.62) to 0.67 (95% CI: 0.64–0.70); p <0.0001} [Table 2].

Figure 1.

PRISM and other patient- and physician-reported outcomes in the overall ICONIC population. [A] Physician- [left panel] and patient-assessed [right panel] PRISM SIS over 24 months. The 5-number summary shown in the box and whisker plot is the minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum. [B] Mean [SD] SIBDQ score over 24 months. [C] Mean [SD] RFIPC score over 24 months. [D] Mean [SD] PHQ-9 score over 24 months. [E] Mean [SD] SCCAI and P-SCCAI score over 24 months. ***p <0.0001 vs baseline. Statistical analysis was calculated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; P-SCCAI, patient-modified SCCAI; PRISM, Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self-Measure; RFIPC, Rating Form of IBD Patient Concerns; SCCAI, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index; SIBDQ, Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; SIS, Self-Illness Separation; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; ICONIC, Impact of ulcerative COlitis aNd Its assoCiated disease burden on patients.

Table 2.

Correlation between patient and physician perceptions of ulcerative colitis.

| Visit | Number of patients | Spearman correlation coefficient [95% CI] | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRISM [patient] vs PRISM [physician] | |||

| Visit 1 (baseline) | 1790 | 0.60 [0.56–0.62] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 2 (Month 6) | 1558 | 0.61 [0.58–0.64] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 3 (Month 12) | 1414 | 0.65 [0.62–0.68] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 4 (Month 18) | 1298 | 0.67 [0.64–0.70] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 5 (Month 24) | 1243 | 0.63 [0.60–0.66] | <0.0001 |

| SCCAI vs P-SCCAI | |||

| Visit 1 (baseline) | 1791 | 0.73 [0.71–0.75] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 2 (Month 6) | 1559 | 0.72 [0.69–0.74] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 3 (Month 12) | 1428 | 0.71 [0.69–0.74] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 4 (Month 18) | 1322 | 0.65 [0.62–0.68] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 5 (Month 24) | 1272 | 0.67 [0.64–0.70] | <0.0001 |

Statistical significance was calculated using exact critical probability [p] values.

CI, confidence interval; PRISM, Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self-Measure; P-SCCAI, patient-modified SCCAI; SCCAI, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index.

<<Fig. 1 and Table 2 near here>>

Mean patient- and physician-completed PRISM scores varied by region [Supplementary Table 3], available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online, with lower physician-completed PRISM scores reported throughout the 24-month follow-up period among patients in Japan compared with other regions. At Months 12–24, patient-completed PRISM scores were higher [indicating less suffering] than physician-completed scores in Japan. Patients in Africa showed the greatest change difference in patient- and physician-completed PRISM score by Month 24 [Supplementary Table 3].

3.3 Change in patient/physician assessment of disease from baseline to Month 24

3.3.1. Disease severity as measured by physicians or patients

Approximately half of all patients were categorised by physicians or self-assessed their disease severity as moderate or severe [Table 1].

The proportion of patients assessed by physicians as being in remission increased from baseline to Month 24 (12.8% [n = 230/1803] vs 53.4% [n = 694/1299]), whereas the proportion of patients with mild disease remained similar over time (baseline: 37.3% [n = 673/1803]; Month 24: 30.9% [n = 401/1299]). Similar results were observed for patient-assessed disease severity over the 24-month study period; at each visit a higher proportion of patients self-assessed their disease as severe than physicians did.

Change in physician and patient assessment of disease severity over time was similar across all regions. However, the highest and lowest proportion of patients with severe disease at baseline were reported in Africa (physician- and patient-assessed: 22.0% [n = 22/100]) and Japan (physician- and patient-assessed: 3.4% [n = 4/116–117]), respectively, relative to other regions (physician-assessed: 9.2% [n = 38/414] to 17.5% [n = 38/217]; patient-assessed: 9.6% [n = 40/415] to 17.2% [n = 25/145]).

3.3.2. Disease activity as measured by the SCCAI and P-SCCAI

At baseline and Month 24, the mean [SD] total SCCAI was significantly lower than P-SCCAI (baseline: 3.0 [3.0] vs 4.2 [3.6]; p <0.0001; Month 24: 1.3 [2.1] vs 2.4 [2.7]; p <0.0001) [Figure 1]; however, there was a strong correlation between SCCAI and P-SCCAI throughout the study (SCCAI vs P-SCCAI: rho = 0.65 [95% CI: 0.62–0.68] to 0.73 [95% CI: 0.71–0.75]; p < 0.0001) [Table 2]. Between baseline and Month 24, the mean [SD] P-SCCAI significantly decreased from 4.2 [3.6] to 2.4 [2.7] (mean [SD] difference of -1.6 [4.0]; p <0.0001] and SCCAI from 3.0 [3.0] to 1.3 [2.1] (mean [SD] difference of -1.6 [3.2]; p <0.0001) [Figure 1].

Patients from Western Asia and Africa reported the highest P-SCCAI (mean [SD]: 5.2 [3.9–4.0]) at baseline relative to other regions [mean: 3.4–4.7], whereas patients in Southern Europe generally reported the lowest P-SCCAI throughout the study [Supplementary Table 4, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online]. At baseline and Month 24, mean SCCAI was the lowest in Japan, followed closely by Latin America and Southern Europe [Supplementary Table 4].

3.3.3. Other patient-reported outcomes

Mean [SD] SIBDQ scores significantly increased (48.3 [13.2] baseline vs 56.0 [11.5] Month 24; mean [SD] difference of 7.1 [14.0]; p <0.0001) during the study (suggesting an improvement in HRQoL) [Figure 1]. Mean [SD] PHQ-9 scores significantly decreased (6.3 [5.4] baseline vs 4.1 [4.5] Month 24; mean [SD] difference of -1.9 [5.4]; p <0.0001) and mean (SD) RFIPC scores significantly decreased (3.4 [2.2] baseline vs 2.7 [2.3] Month 24; mean [SD] difference of -0.7 [2.4]; p <0.001) during the study, suggesting a reduction in UC-associated symptom severity, depression, and worry and concern, respectively [Figure 1]. The measures were generally consistent across regions, except for mean RFIPC score, which was generally higher [indicating greater worry and concern] among patients in Latin America and Japan. Patients in Africa showed the greatest mean difference across the measures by Month 24 [Supplementary Table 4].

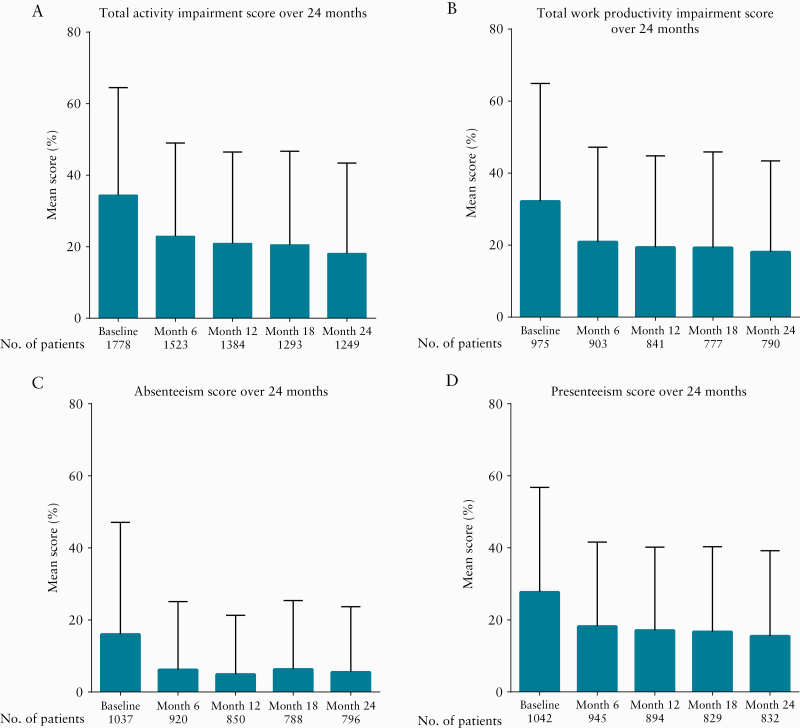

At baseline, among the 1140 employed patients, mean presenteeism [percentage of impairment experienced at work] was 27.7%, mean absenteeism was 16.0%, and mean total work productivity impairment was 32.2% [Figure 2]. The mean total activity impairment irrespective of the patients’ employment status was 34.4% [Figure 2]. During the study, patients showed a gradual [11.1–14.6%] decrease [suggesting an improvement] in absenteeism (mean [SD] difference of -11.1% [32.6]), presenteeism (mean [SD] difference of -12.0% [32.4]), total work productivity impairment (mean [SD] difference of -14.6% [36.2]), and total activity impairment (mean [SD] difference of -14.4% [33.6]) by Month 24 [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

WPAI-GH mean scores at baseline–Month 24. Mean [SD] WPAI-GH scores over 24 months. Percentage values represent level of impairment, with lower values indicative of less impairment. SD, standard deviation; WPAI-GH, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment General Health.

There were decreases in all WPAI-GH parameters [suggesting an improvement] over time across all regions, except for presenteeism in Japan, which showed minimal decrease [Supplementary Table 5, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

<<Fig. 2 and Table 3 near here>>

3.4. Correlations of PRISM [patient] with other patient- and physician-reported outcomes

At baseline and all follow-up visits to Month 24, there was a moderate positive correlation between patient-assessed PRISM scores and SIBDQ (rho = 0.50 [95% CI: 0.47–0.54] to 0.55 [95% CI: 0.51–0.59]; p <0.0001), and a moderate negative correlation between patient-assessed PRISM scores and PHQ-9 (rho = -0.41 [95% CI: -0.45 to -0.37] to -0.43 [95% CI: -0.47 to -0.38]; p <0.0001). Similarly, moderate negative correlation findings were also reported between PRISM [patient] and SCCAI (rho = -0.38 [95% CI: -0.42 to -0.34] to -0.44 [95% CI: -0.48 to -0.39]; p <0.0001), P-SCCAI (rho = -0.43 [95% CI: -0.47 to -0.40] to -0.50 [95% CI: -0.54 to -0.45]; p <0.0001), and RFIPC (rho = -0.40 [95% CI: -0.44 to -0.36] to -0.46 [95% CI: -0.50 to -0.42]; p <0.0001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Correlation of patient-assessed PRISM with other patient- and physician-reported outcomes.

| Visit | Number of patients | Spearman correlation coefficient [95% CI] | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRISM [patient] vs SIBDQ | |||

| Visit 1 (baseline) | 1782 | 0.50 [0.47–0.54] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 2 (Month 6) | 1558 | 0.52 [0.48–0.56] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 3 (Month 12) | 1413 | 0.54 [0.50–0.58] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 4 (Month 18) | 1299 | 0.55 [0.51–0.59] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 5 (Month 24) | 1247 | 0.55 [0.51–0.59] | <0.0001 |

| PRISM [patient] vs PHQ-9 | |||

| Visit 1 (baseline) | 1788 | -0.41 [-0.45–-0.37] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 2 (Month 6) | 1562 | -0.41 [-0.45–-0.37] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 3 (Month 12) | 1415 | -0.41 [-0.45–-0.36] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 4 (Month 18) | 1301 | -0.44 [-0.48–-0.40] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 5 (Month 24) | 1247 | -0.43 [-0.47–-0.38] | <0.0001 |

| PRISM [patient] vs RFIPC | |||

| Visit 1 (baseline) | 1775 | -0.40 [-0.44–-0.36] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 2 (Month 6) | 1555 | -0.39 [-0.43–-0.35] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 3 (Month 12) | 1409 | -0.41 [-0.45–-0.37] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 4 (Month 18) | 1298 | -0.45 [-0.49–-0.41] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 5 (Month 24) | 1242 | -0.46 [-0.50–-0.42] | <0.0001 |

| PRISM [patient] vs P-SCCAI | |||

| Visit 1 (baseline) | 1783 | -0.43 [-0.47–-0.40] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 2 (Month 6) | 1555 | -0.49 [-0.52–-0.45] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 3 (Month 12) | 1413 | -0.49 [-0.53–-0.45] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 4 (Month 18) | 1297 | -0.49 [-0.53–-0.45] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 5 (Month 24) | 1240 | -0.50 [-0.54–-0.45] | <0.0001 |

| PRISM [patient] vs SCCAI | |||

| Visit 1 (baseline) | 1790 | -0.38 [-0.42–-0.34] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 2 (Month 6) | 1557 | -0.43 [-0.47–-0.39] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 3 (Month 12) | 1409 | -0.41 [-0.45–-0.36] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 4 (Month 18) | 1299 | -0.43 [-0.47–-0.38] | <0.0001 |

| Visit 5 (Month 24) | 1246 | -0.44 [-0.48–-0.39] | <0.0001 |

CI, confidence interval; PRISM, Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self-Measure; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire; P-SCCAI, patient-modified SCCAI; RFIPC, Rating Form of IBD Patient Concerns; SCCAI, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index; SIBDQ, Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire.

4. Discussion

This global study, ICONIC, includes data from approximately 1800 patients with recently diagnosed UC [244 sites, 33 countries], regardless of their treatment and is among the largest studies to date in assessing the multifaceted and cumulative burden of UC. The prospective 24-month, non-interventional study provides useful insights into how UC and its associated disease burden, including patient suffering, evolve over time and how PRISM can be used as an assessment tool for suffering in patients with UC.

The primary objective of ICONIC was to evaluate PRISM as an assessment tool for perceived disease-associated suffering in UC. The results presented here demonstrate that suffering, as measured by patient-assessed PRISM, correlated significantly with other patient- and physician-reported outcomes of UC disease activity, depression, HRQoL, and worry/concern. Furthermore, either patient- or physician-assessed PRISM SIS scores reduced significantly over the 2-year study period, a trend that was also observed with disease activity scores in ICONIC. These observed correlations provide further confirmation that PRISM is an appropriate tool for the assessment of patient burden. However, as correlations with other assessment tools were only moderate, each tool clearly reflects distinct disease aspects, and their conjoint use remains justified.

PRISM is a tool that uses a visual metaphor to measure the burden of suffering,14,15 which fits with the widely used conceptualisation of suffering established by Cassel in the early 1980s.22 Disease activity, functional status, illness perceptions, and depression can all contribute to suffering,22 and therefore measurement of suffering is a good candidate for a single, patient-centred outcome measure. Furthermore, alternative questionnaire-based tests can be time consuming and burdensome for physicians and patients, and their use is generally limited to trial settings. By contrast, PRISM can be easily completed by patients in <5 min during routine medical consultations, with immediate results.15 In addition, being an essentially visual tool with simple instructions, PRISM yields comparable results across languages and cultures.15 If used regularly throughout the course of managing patients with UC, PRISM has the potential to unmask increasing disease burden associated with the progression of UC, even in patients who may be deemed to be in remission. Thus, PRISM may have a role in goal-oriented treatment approaches, which aim to measure the extent to which people are able to achieve their personal goals for treatment with minimum burden of disease, and to inform discussion and reappraisal of goals, as well as adjustment of treatment, when goals are not met.

To our knowledge, PRISM has not previously been used in patients with UC, although the correlation of the burden of suffering measured by PRISM with conventionally used patient- and physician-reported outcomes is consistent with findings in other diseases [eg, RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, pain, advanced cancer, tinnitus, and liver disease].7–12,15 In these studies, PRISM SIS showed good correlations with other illness measures, with correlation strength varying according to diagnosis and also between samples with the same diagnosis.15

One secondary objective of ICONIC was to compare patient and physician perceptions of disease. Physician- and patient-assessed PRISM SIS scores were strongly correlated at each visit, indicating a similar gradual reduction in suffering over time. However, at each visit the mean SIS score was significantly higher for the physician vs patient assessment, highlighting an underestimation of patient suffering by physicians. Similar findings were also reported for the physician-assessed SCCAI and patient-assessed P-SCCAI, with physicians reporting lower disease activity. Furthermore, despite physicians assessing that over half of all patients had mild UC or were in remission at baseline, nearly two-thirds of patients who reported sick leave said their sick leave was attributable to UC. Collectively, these data suggest there remains a disconnect between physicians and patients in understanding the burden of patients’ disease. These differences warrant further investigation in the future.

One factor potentially contributing to differences between patients and physicians in appraising UC-related burden is the quality of physician-patient communication, but other factors may also be influential.23 These findings are consistent with previous results, demonstrating differences between patients’ self-perceived experiences with UC and their health care providers’ [including physicians’] estimates of UC disease burden.6,24 Efforts to increase physicians’ understanding of the suffering experienced by patients with UC are key to promoting more appropriate decision making regarding treatment. As an adjunct to standard measures of disease assessment, PRISM can serve as a tool for improving patient-physician communication.15,25 For example, after the patient has completed the PRISM task, simply asking why they put the illness disc where they did usually elicits a highly pertinent but very succinct answer.

Another secondary objective of ICONIC was to describe the multifaceted burden of disease in recently diagnosed patients with UC. Overall, the study showed that burden and suffering for patients with early UC reduced over time through 2 years of follow-up. First, this was demonstrated by a series of physician- and/or patient-completed questionnaire-based tests, including the SCCAI, SIBDQ, RFIPC, PHQ-9, and WPAI-GH, which are recognised to collectively assess disease activity, aspects of physical and mental health, work productivity, and activity impairment in patients with UC.26,27

Furthermore, both physician and patient assessments indicated an increase in UC remission and a reduction in disease severity over the 2-year study period. The improvement in disease severity may have resulted from patients receiving more stringent management, or improved patient compliance during the study. As ICONIC was a non-interventional study, the influence of treatment regimen on disease activity is out of scope for this study. The proportion of patients with ≥1 associated immune-mediated EIM was relatively low at baseline, increasing slightly over time, with RA, EN, and AS remaining the three most common associated immune-mediated EIMs throughout. Associated comorbid diseases and symptoms were also common among patients in the study, consistent with findings elsewhere,28 affecting almost half of the patients at baseline. Fatigue was the most common symptom experienced at baseline, and it increased in incidence over time, despite patients experiencing an improvement in disease severity; indeed, fatigue has been reported as a prevalent and frequently under-recognised, undermanaged symptom in patients with UC.29–31

Last, this study assessed patient suffering and burden by nine geographical regions [Western Europe, Eastern Europe, Northern Europe, Southern Europe, Canada, Western Asia, Africa, Latin America, Japan]. Although the analyses from each geographical region followed the same trends as the overall results of the study, some regional differences were observed. Throughout the 2-year follow-up period, patients in Japan generally had lower patient- and physician-reported PRISM scores [indicating that patients from Japan appraised their suffering as greater] compared with other geographical regions. Despite this, patients in Japan showed consistently more favourable results with the other patient- and physician-reported outcomes (Supplementary Table 3). Furthermore, patients from Africa were consistently the most ‘unwell’ at baseline and showed the greatest mean difference in score across most of the patient- and physician-reported outcomes by 24-month follow-up. Visual metaphors—including PRISM—are interpreted by people in personally meaningful ways, and therefore yield personal assessments. The observed differences between regions may, in part, reflect differing perceptions across cultures of what constitutes suffering and to what degree one suffers as a product of disease. Cross-cultural comparisons may be complicated by different understandings between cultures of the chosen subject, in this case suffering associated with UC. There is also evidence that perceptual processes may differ between cultures, with people from Eastern cultures paying more attention to context than those from Western cultures.17

ICONIC has several strengths, including its prospective design, large sample size, and the fact that patient outcomes were measured using a variety of patient and physician assessment tools. The findings are limited by the fact that it is not a population based study and has no predefined region-specific sample size. Furthermore, changes in disease burden relative to the patients’ treatment regimens were not explored. Despite ICONIC being a non-interventional study, some patients may have received more stringent management, or patient compliance may have improved over time. By its nature, UC is a progressive disease in a significant proportion of patients, advancing from limited to more extensive involvement of the colon, and it can lead to complications, such as neoplasia. ICONIC had a 2-year follow-up duration, which did not afford the opportunity to study the possible contributions of PRISM toward assessing progression of UC over longer periods. Studies over a longer period will be necessary to establish whether the suffering of the patients is related to disease progression. Finally, self-reported outcomes, such as questionnaire results, are inherently prone to self-presentational and recall biases.

In conclusion, this first assessment of PRISM in UC showed that patient-assessed PRISM scores correlated with other patient- and physician-reported outcomes [SCCAI, P-SCCAI, SIBDQ, RFIPC, and PHQ], consistent with our hypothesis that disease activity, quality of life, and depression will each contribute significantly to suffering as measured by PRISM. These findings from ICONIC confirm that PRISM SIS scores are a good indicator of perceived illness burden in patients with UC and may be used to follow up on changes in disease-related suffering. These longitudinal data support the use of PRISM as an additional outcome measure in future clinical trials in UC, to sit alongside standardised UC questionnaires that measure more specific patient- and physician- reported outcomes. Furthermore, this study also adds to the evidence base that, in patients with UC, disease burden and suffering continue to be underestimated by physicians. PRISM may be used to enhance patient-physician communication and identify patients with UC who have a high level of suffering and may be at risk of developing psychological disorders, and therefore require increased care.25

Data sharing statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymised, individual, and trial-level data [analysis datasets], as well as other information [eg, protocols and clinical study reports], as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and statistical analysis plan, and execution of a data sharing agreement. Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

Funding

This work was supported by AbbVie, Inc.

Conflict of Interest

SG: steering committees for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, and Janssen, and an advisory committee for AbbVie; speaker fees received from AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda; consultancy with Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead, and Roche. TS: Nothing to declare. FC: Research funding from AbbVie, Ferring, MSD, Shire, Takeda, and Zambon; speaker fees from AbbVie, Chiesi, Ferring, Gebro, MSD, Shire, Takeda, and Zambon. LCR: speaker honoraria from AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda; advisory board member for AbbVie, Janssen, and Pfizer. TA: speaker fees, advisory board fees, and research funding received from AbbVie, Celgene, Celltrion, Janssen, MSD, NAPP, Pfizer, and Takeda. JRM: speaker receiving sponsorship from AbbVie, Biopas, Biotoscana, Farma, Ferring, Janssen, and Takeda. TV: served as advisory member for Celltrion, Hospira, Pfizer, and Takeda; received lecture fees from AbbVie and Takeda; institution received fee for data collection received from Hepato-Gastroenterologie HK. IG: lecture fees from AbbVie, Falk Pharma, Ferring, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, and Takeda. OS: speaker fees received from AbbVie, Janssen, and Takeda. SA: served as a speaker, consultant, and/or advisory board member for the following organisations: AbbVie, Enthera, Ferring, Janssen, MSD, Mundipharma, Pfizer, Recordati, Sandoz, and Takeda. KK and JP: AbbVie employees, and may own AbbVie stock and/or options. YS: grants and personal fees from AbbVie GK and personal fees from Eisai during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from AbbVie GK; personal fees from Eisai; grants and personal fees from EA Pharma; personal fees from Gilead Sciences; personal fees from Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K.; grants from JIMRO; grants from Kissei Pharmaceutical; personal fees from Kyorin Pharmaceutical; grants from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation; grants and personal fees from Mochida Pharmaceutical; grants from Nippon Kayaku; personal fees from Pfizer Japan; personal fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical; personal fees from Zeria Pharmaceutical, outside the submitted work with no conflict. LPB: personal fees: AbbVie, Allergan, Alma, Amgen, Applied Molecular Transport, Arena, Biogen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Enterome, Enthera, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, Genentech, Gilead, Hikma, Index Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Mylan, Nestlé, Norgine, Oppilan Pharma, OSE Immunotherapeutics, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Roche, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Sterna, Sublimity Therapeutics, Theravance, Tillotts, Takeda, and Vifor; grants from AbbVie, MSD, and Takeda; stock options: CTMA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

AbbVie and the authors thank Annalisa Iezzi, Brandee Pappalardo, Ciara O’Shea, and Kathleen O’Hara for contributing to the design and conduct of the study and would also like to thank the study sites, investigators, and patients who participated in the trial. AbbVie was the study sponsor and contributed to study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, reviewing, and approval of the final version. All authors had access to relevant data and participated in the drafting, review, and approval of this manuscript. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship. Medical writing support was provided by Kevin Hudson, PhD, and Russell Craddock, PhD, of 2 the Nth, which was funded by AbbVie Inc.

Author Contributions

SG, FC, TS, JP, and LPB were involved in the study design. SG, FC, LCR, TA, JRM, TV, IG, OS, SA, YS, and LPB were involved in patient recruitment and data acquisition. All authors contributed equally to data analysis and interpretation and contributed to the development of the manuscript. The authors reviewed drafts and approved and maintained control of the final content. AbbVie contributed to the study design, research, analysis, data collection and interpretation, and the writing, review, and approval of the final version of the publication.

References

- 1. Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2017;389:1756–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McCormick JB, Hammer RR, Farrell RM, et al. Experiences of patients with chronic gastrointestinal conditions: in their own words. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mikocka-Walus A, Knowles SR, Keefer L, Graff L. Controversies revisited: a systematic review of the comorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:752–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Regueiro M, Greer JB, Szigethy E. Etiology and treatment of pain and psychosocial issues in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2017;152:430–9.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yarlas A, Rubin DT, Panés J, et al. Burden of ulcerative colitis on functioning and well-being: a systematic literature review of the SF-36® health survey. J Crohns Colitis 2018;12:600–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schreiber S, Panés J, Louis E, Holley D, Buch M, Paridaens K. Perception gaps between patients with ulcerative colitis and healthcare professionals: an online survey. BMC Gastroenterol 2012;12:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taylor PC, Alten R, Haraoui B, et al. PRISM – pictorial representation of illness and self measure: the use of a simple non-verbal tool as a patient-centred outcome measure in early rheumatoid arthritis cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:529. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Büchi S, Villiger P, Kauer Y, Klaghofer R, Sensky T, Stoll T. PRISM (pictorial representation of illness and self measure) ‐ a novel visual method to assess the global burden of illness in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2000;9:368–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lima-Verde AC, Pozza DH, Rodrigues LL, Velly AM, Guimarães AS. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation for Portuguese (Brazilian) of the pictorial representation of illness and self measure instrument in orofacial pain patients. J Orofac Pain 2013;27:271–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krikorian A, Limonero JT, Vargas JJ, Palacio C. Assessing suffering in advanced cancer patients using pictorial representation of illness and self-measure (PRISM), preliminary validation of the Spanish version in a Latin American population. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:3327–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peter N, Kleinjung T, Horat L, et al. Validation of PRISM (pictorial representation of illness and self measure) as a novel visual assessment tool for the burden of suffering in tinnitus patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016;14:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kabar I, Hüsing-Kabar A, Maschmeier M, et al. Pictorial representation of illness and self measure (PRISM): a novel visual instrument to quantify suffering in liver cirrhosis patients and liver transplant recipients. Ann Transplant 2018;23:674–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aletaha D, Epstein AJ, Skup M, Zueger P, Garg V, Panaccione R. Risk of developing additional immune-mediated manifestations: a retrospective matched cohort study. Adv Ther 2019;36:1672–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Büchi S, Buddeberg C, Klaghofer R, et al. Preliminary validation of PRISM (pictorial representation of illness and self measure)—a brief method to assess suffering. Psychother Psychosom 2002;71:333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sensky T, Büchi S. PRISM, a novel visual metaphor measuring personally salient appraisals, attitudes and decision-making: qualitative evidence synthesis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0156284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn’s relapse prevention trial. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:1571–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, Allan RN. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut 1998;43:29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bennebroek Evertsz’ F, Nieuwkerk PT, Stokkers PC, et al. The patient simple clinical colitis activity index [P-SCCAI] can detect ulcerative colitis [UC] disease activity in remission: a comparison of the P-SCCAI with clinician-based SCCAI and biological markers. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:890–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li ZM, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Patrick DL. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med 1991;53:701–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang W, Bansback N, Boonen A, Young A, Singh A, Anis AH. Validity of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire – general health version in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:R177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cassel EJ The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med 1982;306:639–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Kleef GA, Oveis C, van der Löwe I, LuoKogan A, Goetz J, Keltner D. Power, distress, and compassion: turning a blind eye to the suffering of others. Psychol Sci 2008;19:1315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rubin DT, Dubinsky MC, Martino S, Hewett KA, Panés J. Communication between physicians and patients with ulcerative colitis: reflections and insights from a qualitative study of in-office patient-physician visits. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:494–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Büchi S, Sensky T. PRISM: pictorial representation of illness and self measure. A brief nonverbal measure of illness impact and therapeutic aid in psychosomatic medicine. Psychosomatics 1999;40:314–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alrubaiy L, Rikaby I, Dodds P, Hutchings HA, Williams JG. Systematic review of health-related quality of life measures for inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen XL, Zhong LH, Wen Y, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease-specific health-related quality of life instruments: a systematic review of measurement properties. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Argollo M, Gilardi D, Peyrin-Biroulet C, Chabot JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Comorbidities in inflammatory bowel disease: a call for action. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4:643–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Graff LA, Vincent N, Walker JR, et al. A population-based study of fatigue and sleep difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:1882–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Borren NZ, Tan W, Colizzo FP, et al. Longitudinal trajectory of fatigue with initiation of biologic therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases: a prospective cohort study. J Crohns Colitis 2020;14:309– 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Keightley P, Reay RE, Pavli P, Looi JC. Inflammatory bowel disease-related fatigue is correlated with depression and gender. Australas Psychiatry 2018;26:508–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.