Abstract

Background:

Sepsis is a leading cause of mortality among patients in intensive care units across the USA. Thioredoxin-1 (Trx-1) is an essential 12 kDa cytosolic protein that, apart from maintaining the cellular redox state, possesses multifunctional properties. In this study, we explored the possibility of controlling adverse myocardial depression by overexpression of Trx-1 in a mouse model of severe sepsis.

Methods:

Adult C57BL/6J and Trx-1Tg/+ mice were divided into wild-type sham (WTS), wild- type cecal ligation and puncture (WTCLP), Trx-1Tg/+sham (Trx-1Tg/+S), and Trx-1Tg/+CLP groups. Cardiac function was evaluated before surgery, 6 and 24 hours after CLP surgery. Immunohistochemical and Western blot analysis were performed after 24 hours in heart tissue sections.

Results:

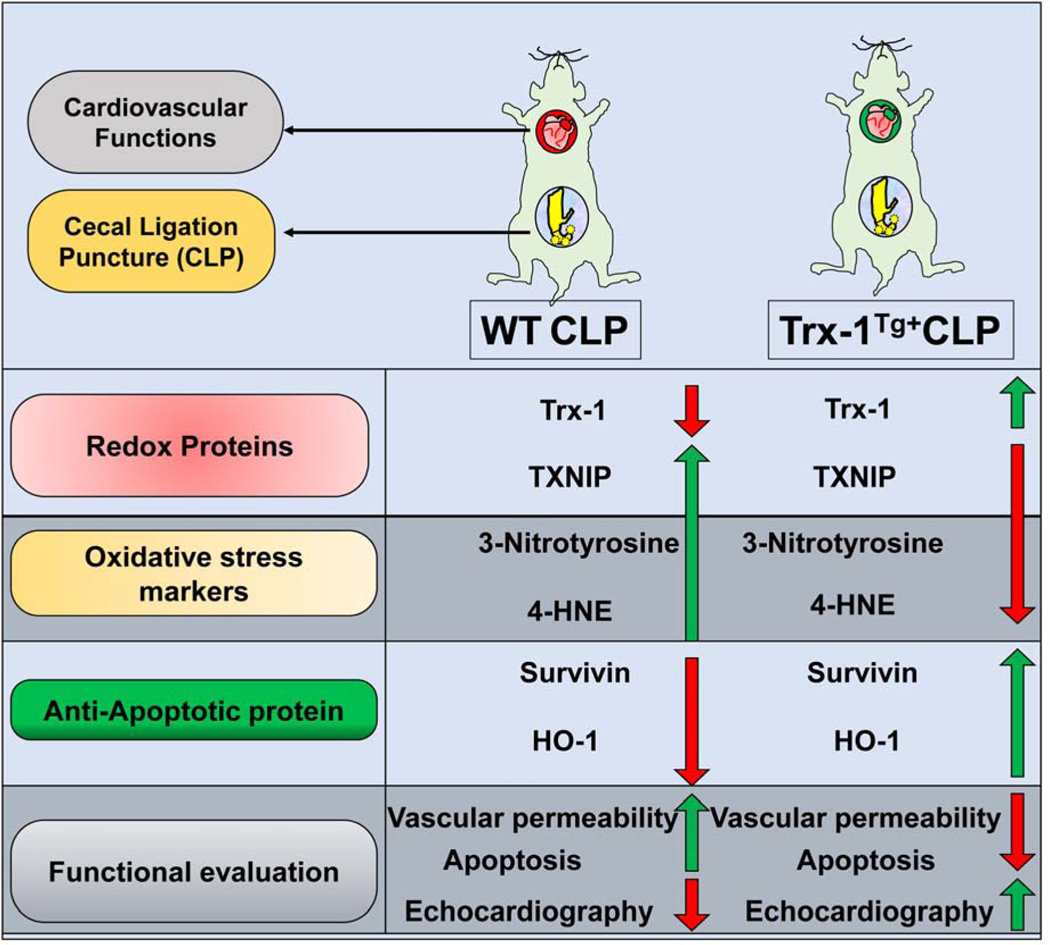

Echocardiography analysis showed preserved cardiac function in the Trx-1Tg/+ CLP group compared with the WTCLP group. Similarly, Western blot analysis revealed increased expression of Trx-1, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), survivin (an inhibitor of apoptosis [IAP] protein family), and decreased expression of thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP), caspase-3, and 3- nitrotyrosine in the Trx-1Tg/+CLP group compared with the WTCLP group. Immunohistochemical analysis showed reduced 4-hydroxynonenal, apoptosis, and vascular leakage in the cardiac tissue of Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice compared with mice in the WTCLP group.

Conclusion:

Our results indicate that overexpression of Trx-1 attenuates cardiac dysfunction during CLP. The mechanism of action may involve reduction of oxidative stress, apoptosis, and vascular permeability through activation of Trx-1/HO-1 and anti-apoptotic protein survivin.

Keywords: angiogenesis, cardiomyopathy, oxidative stress, redox, sepsis, Thioredoxin-1

Introduction

Severe sepsis is a serious life-threatening medical condition that is defined as a systemic infection accompanied by acute organ dysfunction (1). The prevalence of severe sepsis increases each year. Annually, over 750,000 cases of severe sepsis are treated in the USA and over 19 million cases are treated globally, resulting in $16.7 billion in medical costs (1–3). Approximately 10% of all patients in intensive care units (ICUs) are admitted because of severe sepsis. Despite standard therapy such as intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and cardiovascular and respiratory support, the mortality rate due to severe sepsis is 25% to 30% (4–7). The incidence of severe sepsis is more prevalent among immunocompromised individuals such as newborns and the elderly. Of all health care-associated causes of sepsis, pneumonia is the most common cause, followed by intra-abdominal and urinary tract infections (8, 9). The gold standard therapy for the treatment of severe sepsis aims to eradicate the causative pathogen by using antibiotics. However, this approach addresses only one-third of the larger systemic disease. Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS) is considered as the terminal stage of severe sepsis. The theory behind the pathophysiology of MODS is a selective imbalance between the host’s pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses. Although MODS can manifest in various ways depending on the affected organs, mortality occurs in 70% to 90% of cases when sepsis is accompanied by cardiovascular complications (10). Sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy is a reversible myocardial dysfunction, characterized by an injured myocardium due to inflammatory cytokines, mitochondrial dysfunction, regional ischemia, upregulation of endothelin, myocardial depressant substance, and activation of the anticoagulant system (11–14).

Among the major cellular redox antioxidants, thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems play a pivotal role in maintaining a balanced redox state within the cell (15–19). Thioredoxin-1 (Trx-1) is a 12 kDa cytosolic protein that has antioxidant, proangiogenic, growth stimulatory, and anti- inflammatory properties (2, 20). The two cysteine residues that are present in Trx-1 are reversibly oxidized, which results in the reduction of free radicals and harmful proteins that can alter the redox state of the cell. The role of Trx-1 is tightly regulated by the action of thioredoxin inhibitory protein (TXNIP), which negatively regulates the antioxidant property of Trx-1 (21, 22). In our previous study, we found thioredoxin-1 overexpressing transgenic animals can effectively overcome the adverse ventricular remodeling during chronic myocardial infarction (2). In addition, we found that thioredoxin-1 gene delivery offers cardioprotection in diabetes-associated myocardial infarction (23). In a recent study, we found that mesenchymal stem cells preconditioned with thioredoxin-1 can improve the therapeutic outcome of the stem cell therapy to treat myocardial infarction (24). In addition we have shown that increased Trx-1 expression inhibits oxidative stress, and activates the enzyme hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1) to promote the antioxidant effect (23). The aims of our current study are to establish a severe polymicrobial sepsis model by the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) approach, and compare the outcomes between wild type (WT) mice and transgenic mice overexpressing Trx-1 (Trx-1Tg/+) during sepsis-induced myocardial depression. The present study concludes that increased Trx-1 levels may offer potential therapeutic relevance for the treatment of CLP-induced myocardial injury by activation of the Trx-1/HO-1 and anti-apoptotic protein survivin.

Materials and methods

Animals

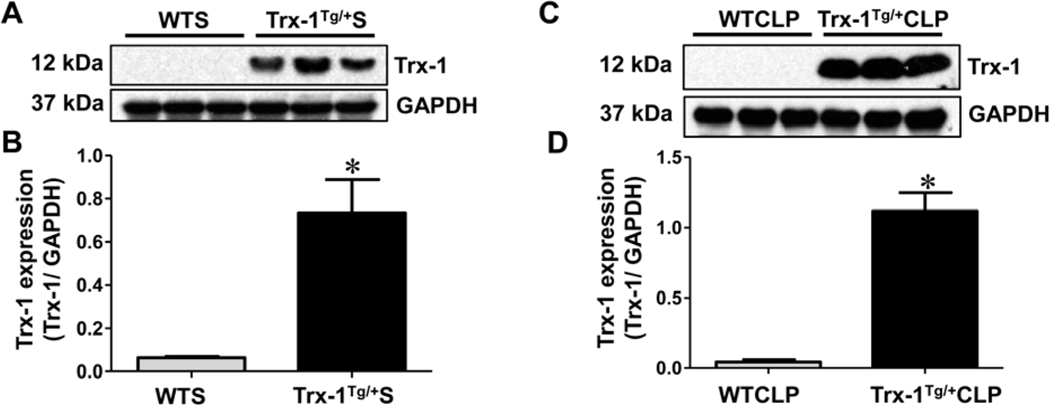

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of laboratory animal care set forth by the National Society for Medical Research, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health (Publication No. 85–23, revised 1985). Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of The University of Connecticut Health (Farmington, CT). Farmington, CT (protocol number 100986–1217). Male and female C57BL/6J mice, 8 weeks of age, were used in this study. The generation, characterization, genotyping, and maintenance of Trx-1Tg/+ mice have been described previously (2). Overexpression of Trx-1 in Trx-1Tg/+ mice was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Western blot analysis of Trx-1:

Differential expression of Trx-1 in wild type (WT) and Trx-1Tg/+ animals in sham (A-B), and CLP (C-D) surgeries are shown. Trx-1Tg/+S mice show increased Trx-1 expression compared to wild-type sham (WTS) mice. Similarly, Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice show increased Trx-1 expression compared to WTCLP mice. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control (n = 3; p < 0.05).

Experimental design

To evaluate the effect of Trx-1 overexpression on cardiac function during severe sepsis, mice were randomly grouped into WT sham (WTS), WTCLP, Trx-1Tg/+sham (Trx-1Tg/+S), and Trx-1Tg/+ CLP. Animals underwent a preoperative echocardiogram, and postoperative echocardiograms at 6 and 24 hours after surgery. The shorter time point for echo analysis was due to symptomatic effects observed in animals, including weak, sluggish and poor response to stimuli due to the severity of the sepsis after 24 hours. We used this short experimental period because the animals were found to be weak and sluggish one day after surgery and to respond poorly to stimuli due to the severity of the sepsis. Twenty-four hours after sham or CLP surgery, tissue samples were collected from the ventricles and Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry were performed. To study vascular leakage from cardiac tissues, Evans blue dye was injected intraperitoneally into the mice, and heart tissue samples were collected after 24 hours for analysis.

Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model

Prior to CLP surgery, animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg per kg of body weight), and xylazine (10 mg per kg of body weight). Ventral skin hair was removed from the abdomen, and betadine solution was used as a sterilizing agent. A midline vertical incision of 2 to 3 cm was made in the abdominal skin tissue, and the fascia was opened to enter the peritoneal cavity. The cecum, which is usually located on the left side of abdomen, was carefully externalized, and the fecal contents were milked toward the blind pouch. The cecal tissue distal to the ileocecal valve was ligated with silk suture, leaving about 75% of the cecum below the ligation. Using an 18-gauge needle, two through-and-through punctures were made in the cecum, resulting in severe sepsis. To confirm a through-and-through needle puncture, a small amount of stool was exposed from the cecum through the punctured orifice before being returned to the intraperitoneal position. The fascia was closed in a running fashion using 5–0 vicryl suture, and the skin was closed in an interrupted fashion using 5–0 nylon suture (Figure 1A). Pre-warmed saline was then administered intraperitoneally (0.05 mL/g of body weight) for resuscitation, and buprenorphine was administered (intramuscularly; IM) for analgesia (25–28).

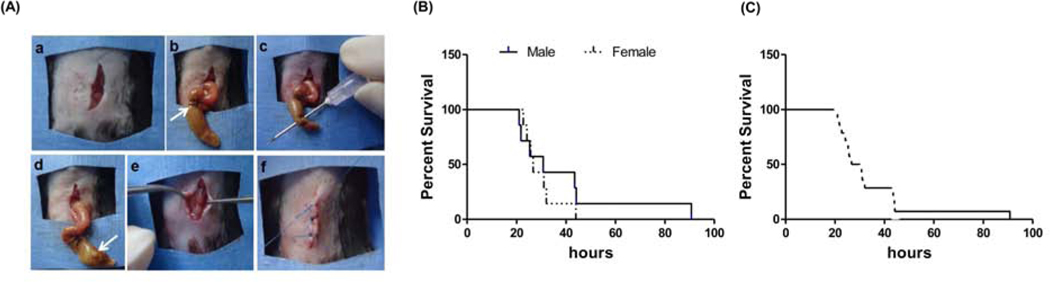

Figure 1. Experimental timeline and cecal ligation and puncture surgical procedure:

(A) Step-by-step surgical protocol to establish the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model using a double-puncture technique. a) A vertical midline incision was made in the abdomen through skin and fascia. b) The cecum was brought outside the body. c) An 18-gauge needle was used to make two through-and-through punctures through the cecum. d) A small amount of stool was expressed from each opening. e) The cecum was replaced in the abdomen, and the fascia was closed. f) Closure of skin followed by animal recovery. (B) Survival analysis: Male (n = 7) and female (n = 7) wild-type mice, percent survival at varying time points (in hours). No statistical significant difference in survival was found between the groups (p = 0.42). (C) Combined male and female survival data (n = 14), showing 100% mortality at 90 hours after CLP surgery and a median survival of 26.6 hours.

Survival analysis

Survival analysis was performed on WT mice (age- and sex-matched) to assess the severity of sepsis induced by the CLP procedure. Survival rates after CLP were monitored every day for four days, until all the animals died. A Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showing survivability following the CLP procedure is shown in Figures 1B–C.

Echocardiography

To evaluate cardiac function, echocardiography was performed preoperatively, and postoperatively at 6 and 24 hours after surgery, as previously described (2). Briefly, mice were anesthetized using 2% isoflurane, and secured in a supine position on a custom mold. The fur in the precordial region was removed, and echocardiography was performed with a high-resolution in vivo micro-imaging system (Vevo 770, Visual-Sonics Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada) using a 25 MHz transducer. Real-time monitoring of the motion of the left ventricle was performed in the parasternal long and short axes views. Two-dimensional M-mode images were obtained, and ejection fraction (EF, %) and fractional shortening (FS, %) measurements were performed (2).

Western blot analysis

Twenty-four hours after sham and CLP surgeries, cardiac ventricular tissues of WT and Trx-1Tg/+ mice were harvested, and the cytosolic protein fraction was collected as previously described (2). In brief, tissue lysates were prepared and proteins were extracted from the lysate using the CelLytic™ NuCLEAR™ Extraction Kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The concentration of obtained proteins was determined using a Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockville, IL). Standard SDS-PAGE Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate the expression of Trx-1, TXNIP, HO-1, 3-nitrotyrosine, and survivin (24, 29). Proteins were run using polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels at varying percentages. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PDVF) membranes and incubated with primary antibodies against Trx-1 (sc20146, SantaCruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), TXNIP (40–3700, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), HO-1 (ADI-OSA-150F, Enzo Life Sciences, Farmington, NY), 3-nitrotyrosine (sc55256, SantaCruz Biotechnology), survivin (ab469, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and Caspase-3 (sc7148, SantaCruz Biotechnology).

Immunohistochemistry for 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE)

To study the expression of 4-HNE in tissues collected from WT and Trx-1Tg/+ mice, immunohistochemical analysis was performed 24 hours after CLP surgery. Paraffin-embedded tissue was cut into 5-μm thick transverse sections, and deparaffinized using a graded series of histoclear and ethanol. Tissue sections were stained using a primary antibody directed against 4-HNE (HNE11-S, Alpha Diagnostic International Inc, San Antonio, TX), followed by treatment using a Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (mouse IgG;Vector Laboratories, Inc, Burlingame, CA). The staining was visualized using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate and the Vector ABC Vectastain Elite Kit (Vector Laboratories Burlingame, CA). Nuclear counterstaining using hematoxylin was performed, and images were captured at 400x magnification using an Olympus BH2 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) (29).

Assessment of vascular permeability in cardiac tissue

To determine if overexpression of Trx-1 causes alterations in vascular permeability in cardiac tissue, 2% w/v Evans blue dye (E2129, Sigma, MO) was injected intraperitoneally 21 hours after CLP surgery, allowing the Evans blue dye to circulate for 3 hours prior to animal sacrifice. Twenty-four hours after CLP surgery the mice were sacrificed and the hearts were isolated. Hearts were embedded in paraffin, sectioned and treated with a graded concentration of histoclear and ethanol. After subsequent washes with PBS, tissue sections were covered with UltraCruz Mounting Medium (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and microscopic evaluation was carried out using an Olympus DP73 camera and Olympus cellSens software (version 1.5; Olympus). The images were taken at 100x magnification, and background and subtraction settings were kept constant between images.

Evans blue dye is a metabolically inactive and non-toxic tracer that is commonly used to estimate plasma volume and vascular permeability in animal models (30). Evans blue dye rapidly binds to serum albumin and can be detected in organs when plasma extravasation occurs due to endothelial cell hyperpermeability, which often occurs in septic organs (31).

TUNEL apoptosis assay

To determine the percentage of apoptosis present in cardiac tissue, mice were sacrificed 24 hours after CLP surgery. Hearts were harvested and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Subsequently, fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, paraffin blocks were prepared, and 5-μm thick sections were cut. Immunohistochemical analysis of apoptotic cells was performed using the In Situ Cell-Death Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Fluorescein-stained cells were used to detect apoptotic cells by using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) reaction, as previously described (2, 32). Per section, 10 to12 images were acquired at 40x magnification using a confocal laser Zeiss LSM 510 meta microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Per field, apoptotic nuclei were counted, and expressed as a percentage of the total nuclei, which were visualized by TO-PRO®−3 staining (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism software, version 5.0 for Windows (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA). Survival after the CLP procedure was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis method. A t test analysis was performed to determine statistical significant differences between groups. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.).

Results

Severity of sepsis model

To assess the severity of CLP procedure, we measured the survival of WT mice (7 male and 7 female) after CLP surgery for 4 days (Figure 1B–C). The survival of male mice was 57.1% at 25 hours after CLP surgery, and 14.3% at 48 hours after CLP. For female mice, survival was 57.1% at 26 hours after CLP surgery, and 0% at 44 hours after CLP. No statistically significant effect of gender was observed on survivability after CLP surgery. The male-to-female survival hazard ratio was 0.6226 (95% CI, 0.1962 to 1.976), which was not significantly different (Figure 1B). Thus, septic WT mice demonstrated 50% survival at 24 hours after the CLP procedure, regardless of sex (Figure 1C). Interestingly, when compared between WT and Trx-1 transgenic animals we found that the survival rate of all WT animals at 24 hours was 70.2%, while the survival of Trx-1Tg/+ mice at 24 hours was 92.6% (p=0.0254).

Long-term expression of Trx-1 transgene in Trx-1Tg/+ mice.

Western blot analysis was carried out using ventricular tissue samples collected 24 hours after surgery to evaluate the level of Trx-1 expression in WT and Trx-1Tg/+ mice after sham and CLP surgery. We found that Trx-1 levels in sham-operated Trx-1Tg/+S mice were 11.48-fold higher than Trx-1 levels in WTS (Figure 2A–B). Similarly, the Trx-1 expression levels in Trx-1Tg/+ mice were 25.76- fold higher compared with those in WTCLP mice (Figure 2C–D). Overall, mice in WTS and WTCLP groups showed reduced levels of Trx-1 expression compared with mice in Trx-1Tg/+S and Trx-1Tg/+CLP groups.

Downregulation of TNXIP in Trx-1Tg/+ mice:

The TXNIP expression levels in the heart tissue of mice collected 24 hours post-sham and CLP surgery were evaluated by Western blot analysis. We found that TXNIP levels were reduced in mice in the Trx-1Tg/+S group compared with mice in the WTS group (Figure 3A–B). Similarly, mice in the Trx-1Tg/+CLP group showed decreased TXNIP expression levels (7.65-fold) compared with WTCLP mice (p < 0.05; Figure 3C–D).

Figure 3. Western blot analysis of TXNIP:

Differential expression of thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) in wild type (WT) and Trx-1Tg/+ mice after sham (A-B), and CLP (C-D) surgeries. Trx-1Tg/+S mice show decreased TXNIP expression compared to wild-type sham (WTS) mice. Similarly, Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice show decreased TXNIP expression compared to WTCLP mice. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control (n = 3, p < 0.05).

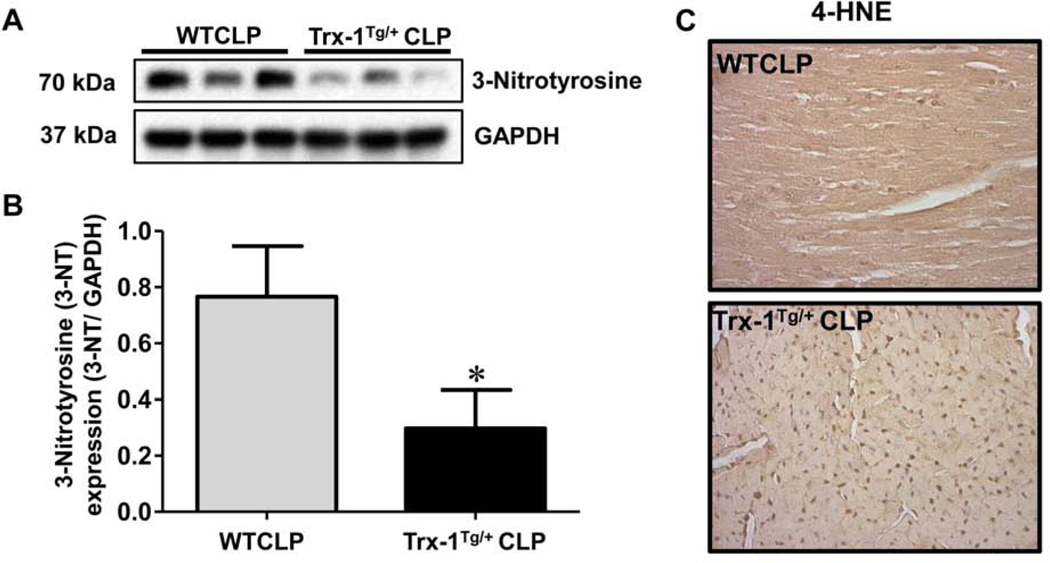

Trx-1 mediated reduction of oxidative stress (3-nitrotyrosine and 4-HNE) in Trx-1Tg/+ mice:

To evaluate the antioxidant potential of Trx-1 in our sepsis model, we analyzed the expression of two potent oxidative stress markers, 3-nitrotyrosine and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), by Western blot analysis (Figure 4A–B) and immunohistochemistry (Figure 4C), respectively. Analysis of 3-nitrotyrosine expression revealed that 3-nitrotyrosine expression was significantly increased (2.57-fold) in WTCLP mice compared with Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice (Figure 4A–B). Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis showed a decrease in 4-HNE staining in mice in the Trx-1Tg/+CLP group compared with WTCLP mice. These results suggest that Trx-1 overexpression effectively combats oxidative stress during CLP-induced sepsis.

Figure 4. Molecular analysis of oxidative stress markers 3-Nitrotyrosine and 4-HNE:

(A-B) Western blot analysis of 3-nitrotyrosine expression in cardiac tissue samples collected 24 hours after CLP surgery. Expression levels of 3-nitrotyrosine were significantly reduced in Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice compared to wild type (WT)CLP mice. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control (n = 3; p < 0.05). (C) Immunohistochemical analysis of 4-HNE in cardiac tissue collected 24 hours after CLP surgery. Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice show decreased 4- HNE staining compared to WTCLP mice, which indicates reduced lipid peroxidation due to transgenic Trx-1 expression (n = 6).

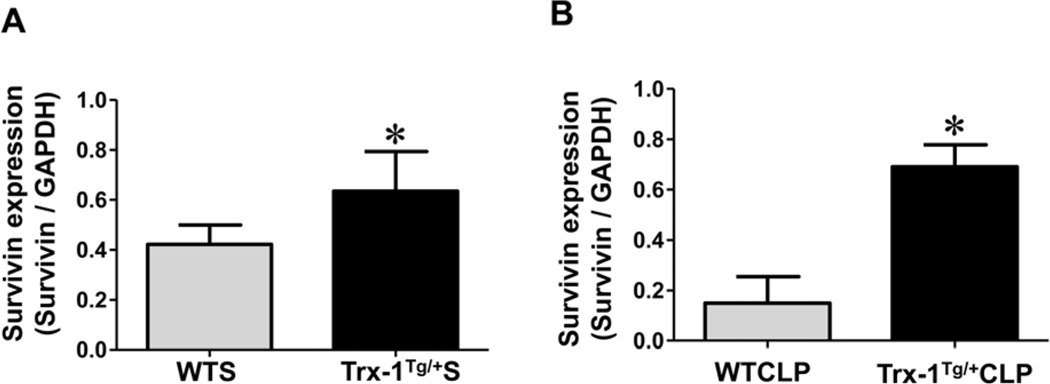

Trx-1 mediated increase of survivin in Trx-1Tg/+ mice:

We used Western blot analysis to evaluate the role of Trx-1 overexpression in the regulation of survivin (a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis [IAP] protein family) after sham and CLP surgery. Mice in the Trx-1Tg/+S group showed an increase in survivin expression (basal level) compared with WTS mice (Figure 5A). Similarly, the expression of survivin in Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice was found to be significantly increased compared with that in WTCLP mice (Figure 5B). The expression of survivin in Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice was 4.6-fold higher than in WTCLP mice, whereas in Trx-1Tg/+S mice, survivin expression was 1.51-fold higher than in WTS mice.

Figure 5. Molecular analysis of survivin expression:

(A-B) Western blot analysis of survivin expression in cardiac tissue samples collected 24 hours after sham (A) and CLP (B) surgeries. The expression of survivin is highly upregulated in Trx-1Tg/+S mice and Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice compared to wild-type sham WTS and WTCLP mice, respectively. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control (n = 3, p < 0.05).

Trx-1 effectively rescues cells from apoptosis during severe sepsis:

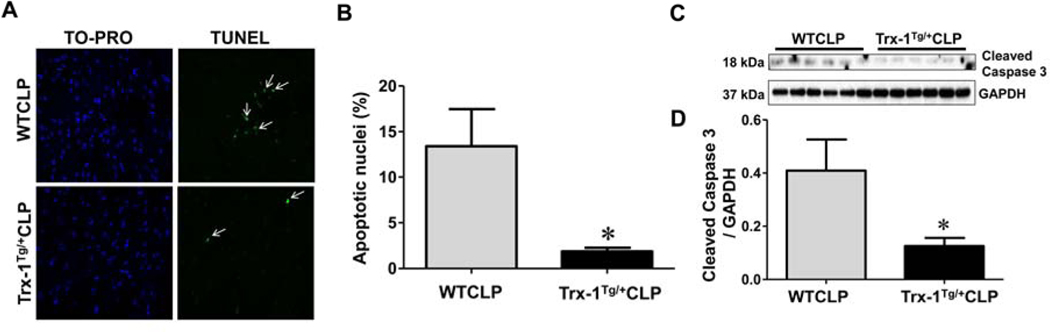

The therapeutic potential of Trx-1 overexpression for reducing apoptosis during severe sepsis was evaluated by TUNEL staining and caspase-3 analysis. The white arrows in the microscopic images in Figure 6A indicate that the fluorescent green signal detected corresponded to TUNEL staining. The percentage of apoptotic cells was significantly reduced in Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice (1.85%) compared with WTCLP mice (13.42%) (Figure 6B). Next, we analyzed the expression of cleaved executioner caspase-3 (18 kDa), which is an important hallmark associated with apoptosis. Western blot analysis showed significant downregulation of cleaved caspase-3 in Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice (3.26-fold) compared with WTCLP mice (Figure 6C–D). Taken together, our results demonstrate that Trx-1 is extremely effective in rescuing cells from apoptosis during severe sepsis.

Figure 6. Effect of Trx-1 overexpression on apoptosis:

(A) Immunohistochemical analysis of apoptotic nuclei stained with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) that are counterstained with TO-PRO-3. (B), The percentage of apoptosis was calculated using immunohistochemical images of WTCLP and Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice. Apoptotic nuclei that were positive for TUNEL are indicated by white arrows. The number of apoptotic cells in Trx-1Tg/+ CLP mice is significantly lower than that of WTCLP mice. (C-D) Western blot analysis of cleaved caspase-3: Differential expression of cleaved caspase-3 protein expression protein in WT and Trx-1Tg/+ mice after CLP surgeries are shown (C-D). Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice show decreased levels of cleaved caspase-3 protein compared to WTCLP mice. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control (n = 6; p < 0.05).

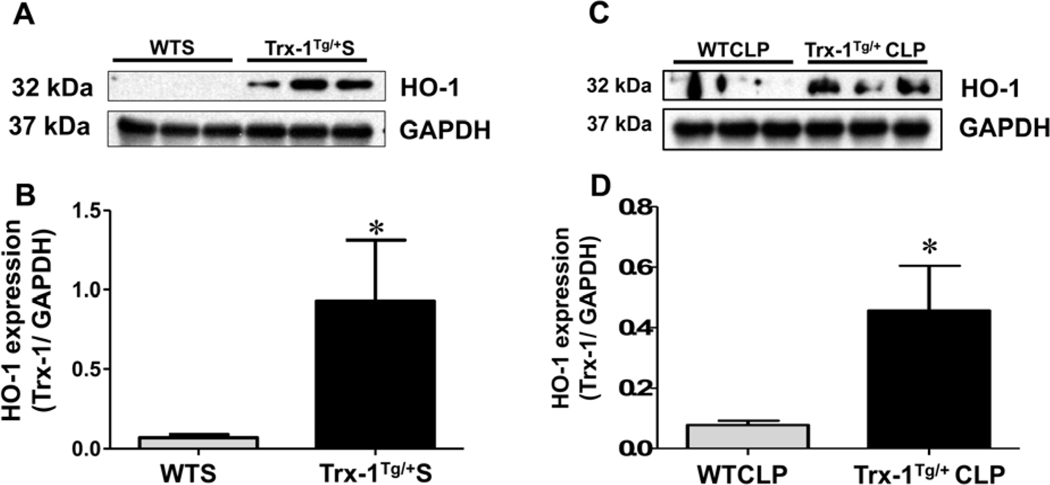

Trx-1 mediated upregulation of proangiogenic HO-1 in Trx-1Tg/+ mice:

Twenty-four hours after sham surgery, the antiapoptotic protein, HO-1 levels were found to be significantly higher in Trx-1Tg/+S mice (13.48 fold) compared with WTS mice (Figure 7A–B). Similarly, HO-1 expression was found to be 5.94-fold higher in Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice compared with WTCLP mice (p < 0.05).

Figure 7. Western blot analysis of HO-1:

(A-D) Western blot analysis of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) expression in cardiac tissue samples collected 24 hours after of sham (A-B) and CLP (C-D) surgeries. The expression of HO-1 protein is highly upregulated in Trx-1Tg/+S and Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice compared with wild-type sham (WTS) and WTCLP mice, respectively. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase GAPDH was used as a loading control (n = 3, p < 0.05).

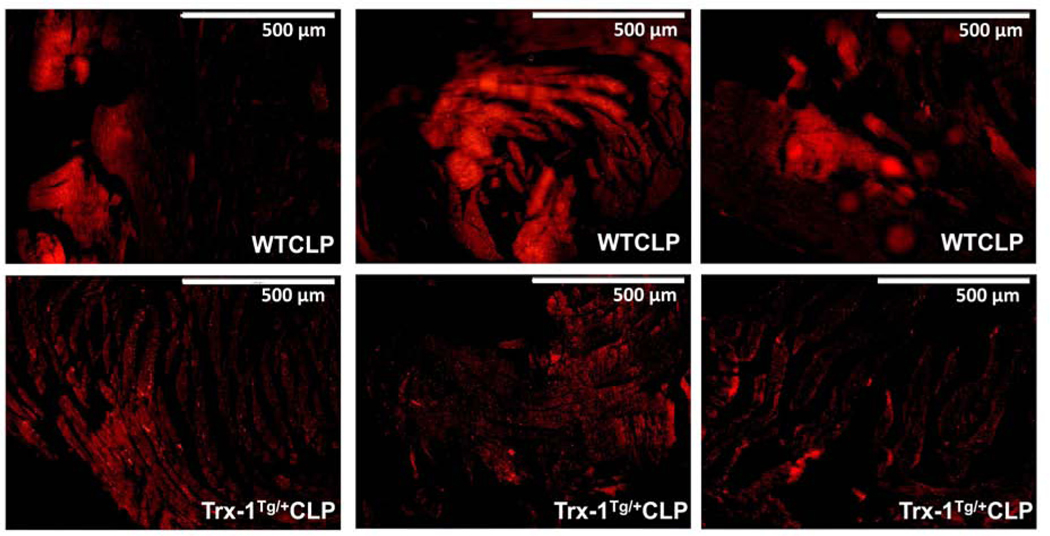

Trx-1 overexpression attenuates sepsis-induced vascular permeability in Trx-1Tg/+ mice:

The role of Trx-1 overexpression in controlling vascular leakage was analyzed by Evans blue staining. Evans blue dye was intraperitoneally injected into mice 3 hours before sacrifice. Cardiac tissue was then collected and embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded tissue sections of both left and right ventricles were analyzed under a fluorescent microscope. The fluorescence intensity, representing sepsis-induced vascular hyperpermiability. The fluorescence intensity was reduced in ventricles derived from Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice compared with WTCLP (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Immunohistochemical analysis of vascular permeability by Evans blue dye staining:

The immunofluorescent microscopic images of cardiac sections stained for vascular permeability 24 hours after CLP surgery is shown. The wild-type (WT)CLP group showed increased fluorescent staining of Evans blue dye compared with the Trx-1Tg/+ CLP group (n = 4–5; p < 0.05).

Trx-1 preserves cardiac function in sepsis-induced heart failure:

The effect of Trx-1 overexpression in controlling adverse cardiac function was analyzed by echocardiography analysis, and functional assessments of WT and Trx-1Tg/+ hearts were made before and after CLP surgeries. Two-dimensional M-mode images along with left ventricular internal diameter end diastole (LVIDd, mm), left ventricular internal diameter end systole (LVIDs,mm), EF (%), and FS(%) showed normal cardiac function in WT and CLP mice prior to surgery (Figure 9A–D). However, 6 hours after CLP surgery, both WTCLP and Trx-1Tg/+CLP showed significant reduction in both EF (%) and FS (%) compared to their preoperative level (Figure 9A–D). When compared between WTCLP and Trx-1Tg/+CLP groups, both EF (%) (45.71 ± 4.57 vs. 58.12 ± 7.23) and FS (%) (21.98 ± 2.603 vs. 29.74 ± 4.52) were found to be preserved in Trx-1Tg/+, which is represented by increased EF(%) and FS(%) in Trx-1Tg/+CLP group, 6 hours after surgery. Similarly, 24 hours after CLP surgery, Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice showed preserved systolic function represented by increased EF(%) (62.72 ± 7.76 vs. 47.17 ± 5.12) and FS(%) (32.51 ± 5.57 vs. 22.61±2.76) compared with WTCLP mice. No significant change in EF(%) and FS(%) was observed between WTCLP-6hr and WTCLP-24, as well as Trx-1Tg/+CLP-6hr and Trx-1Tg/+CLP-24hr.

Figure 9. Preoperative and postoperative echocardiography analysis:

Two-dimensional M-mode echocardiography images in both wild type (WT) and Trx-1Tg/+ mice before (preoperative), and 6 and 24 hours after CLP surgery are shown (A-D). The calculated (A) left ventricular internal diameter end diastole (LVIDd, mm), (B) left ventricular internal diameter end systole (LVIDs, mm), (C) EF (%) and (D) FS (%) are indicated. Cardiac function is impaired at 6 hours after CLP-induced sepsis, and no improvement was observed at 24 hours after CLP surgery. However, Trx-1Tg/+ mice subjected to CLP prevented the impairment of cardiac function, thereby reflecting increased ejection fraction (EF, %) and fractional shortening (FS, %) in Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice compared with WTCLP mice. (n = 9–11; p < 0.05).

Discussion

Our study strongly suggests that Trx-1 is a potent molecule that effectively maintains the antioxidant system, and governs cellular redox homeostasis during myocardial depression in severe sepsis (Figure 10). Previous studies have documented that myocardial dysfunction in sepsis is a reversible process that significantly increases mortality in patients (12). The currently available literature offers a myriad of theories as to the cause of myocardial depression, which is likely multifactorial in nature (3, 12). This study has offered a platform to investigate the various molecules that are targeted by Trx-1 in reducing myocardial damage. Although previous studies have shown that, during sepsis, survival rates are improved in females compared with males (33–35), we did not observe any gender-based survival differences. In our study, most animals died at or before 48 hours after CLP surgery (Figure 1B–C). Western blot analysis for 3-nitrotyrosine and 4-HNE expression demonstrated that Trx-1 reduces the expression of 3-nitrotyrosine and 4-HNE in Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice. Apart from reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging, Trx-1 effectively participates in lowering lipid peroxidation and thereby maintains cellular membrane stability during severe sepsis. To prevent irreversible organ damage these processes must be limited both in the myocardium and throughout the body. In addition, survivin levels before and after the induction of sepsis are maintained in Trx-1Tg/+ mice, which helps to more effectively combat oxidative stress compared with WT mice (2). Moreover, in this study cytoprotective characteristics of Trx-1 were evident from TUNEL staining and caspase-3 expression; we demonstrated a significant decrease in apoptotic nuclei and reduced caspase-3 expression in Trx-1Tg/+CLP mice compared with WTCLP mice.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram to show the overall therapeutic effect achieved through Trx-1 transgenic overexpression in a mouse model of severe sepsis.

Western blot analysis revealed that TXNIP, a negative regulator of Trx-1, were significantly reduced in Trx-1Tg/+ mice compared with WTCLP mice. It was reported earlier that hyperglycemia induced oxidative stress was due to the increased expression of TXNIP which was followed by inhibition of antioxidant function of Trx-1. This inhibition of Trx-1 activity is due to its interaction (binding) with TXNIP that reduces its ability to bind efficiently to its binding partners, thereby reducing anti-apoptotic property of Trx-1 (36). In our present study decreased expression of TXNIP in Trx1 overexpressed mice shows novel therapeutic event in reducing oxidative stress due to sepsis. We further demonstrated that Trx-1 works in conjugation with the anti-inflammatory protein HO-1 to exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory protection in tissues subjected to severe sepsis. Prior studies have shown that Trx-1 works in concert with HO-1 to rescue cardiac tissue from ischemia-reperfusion injury and diabetic/hypertensive conditions (16, 23, 24). Microvascular hyperpermeability is a well-known phenomenon in sepsis characterized by a breakdown in the endothelial cell-cell junction that creates leakiness across vessels. This allows ROS and other inflammatory mediators to traverse into organ tissues and cause damage (37–40). In our study, we measured sepsis-induced myocardial tissue damage by Evans blue dye. Our results demonstrated that Evans blue dye, which binds to albumin in the blood, can cross the endothelial cell barrier in WT mice under severe septic conditions. This well-known characteristic of severe sepsis is significantly attenuated when Trx-1 is overexpressed.

Our results in echocardiography show improved ejection fraction and fractional shortening in Trx-1Tg/+ mice after induction of severe sepsis. The EF represents the ability of heart to deliver blood to the rest of the body. An increased EF compared to WT mice suggests an improvement in circulating blood volume, which, in turn, can improve end organ perfusion. These factors may help mitigate the multi organ dysfunction seen in severe sepsis. The increased FS values in Trx-1Tg/+ mice represent the ability of the cardiac muscle to contract and relax effectively with the help of Trx-1 during sepsis. This effective fractional shortening helps to facilitate an improved EF during sepsis.

Although there is no direct evidence to show the effect of Trx1 on the microbiome after CLP, we found indirect evidences do exists in the literature which supports the need for Trx-1. During inflammation in the gut, tetrathionate are produced through NADPH oxidase-dependent oxidative burst. This tetrathionate effectively used by the microbiome as respiratory electron acceptor and leads to microbiome flourishmnet in the gut. To counterbalance this effect, the monocytes recruited during inflammation secrete thioredoxin reductase enzyme which not only reduces (reduction reaction) the active Trx1 to minimize the oxidative burst, but also reduces (reduction reaction) tetrathionate to thiosulfate (41). Recent evidences also supports the fact that the gut microbiome modulates the inflammatory cell recruitment and their function after CLP induced sepsis condition (42). Thus we hypothesize that Trx1 in the gut during inflammation is tightly regulated by Trx1 reductase to reduce the microbial growth and hence the effect of Trx1 can have profound effect to overcome the microbial induced inflammatory oxidative stress.

We conclude that Trx-1 has great potential to attenuate myocardial depression during severe sepsis. Moreover, through transgenic Trx-1 expression in severe sepsis models, we found reduced expression of 3-nitrotyrosine and 4-HNE, which are potent markers of oxidative stress. In addition, we observed an upregulation of survivin expression, a well-known cell survival marker, along with reduced apoptosis in the presence of increased Trx-1 expression in a severe sepsis model. This indicates that Trx-1, when overexpressed, effectively reduces oxidative stress and leads to increased survival during severe sepsis. Due to increased Trx-1 expression, increased expression of HO-1, having antioxidant function further confirmed the power of antioxidant characteristics of Trx-1. These properties promote stability at the endovascular cell junction, and prevent microvascular hyperpermeability as demonstrated by our Evans blue results. Lastly, our echocardiography analysis demonstrated improved cardiac function due to Trx-1 overexpression during severe sepsis. Therefore, Trx-1 treatment may serve as an adjunctive strategy to restore the redox status during sepsis.

Acknowledgments:

We acknowledge Scott Shafer, B.S, for his assistance in immuno-histochemical studies.

This work was supported by National Institute of Health GM112957 to NM, Canzonetti Fund to NM and the American Medical Association Foundation to RLW

Footnotes

Disclosure: This work was presented as a podium lecture at Society of Black Academic Surgeons (SBAS) Twenty-sixth Annual Scientific Meeting held on Apr 28 – 30, 2016 Columbus, Ohio

Conflict of interest : None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Angus DC, van der Poll T Severe sepsis and septic shock. The New England journal of medicine 2013:369:840–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adluri RS, Thirunavukkarasu M, Zhan L, Akita Y, Samuel SM, et al. Thioredoxin 1 enhances neovascularization and reduces ventricular remodeling during chronic myocardial infarction: a study using thioredoxin 1 transgenic mice. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 2011:50:239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merx MW, Weber C Sepsis and the heart. Circulation 2007:116:793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen J, Vincent JL, Adhikari NK, Machado FR, Angus DC, et al. Sepsis: a roadmap for future research. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2015:15:581–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar G, Kumar N, Taneja A, Kaleekal T, Tarima S, et al. Nationwide trends of severe sepsis in the 21st century (2000–2007). Chest 2011:140:1223–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent JL, Marshall JC, Namendys-Silva SA, Francois B, Martin-Loeches I, et al. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the intensive care over nations (ICON) audit. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine 2014:2:380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steele AM, Starr ME, Saito H Late Therapeutic Intervention with Antibiotics and Fluid Resuscitation Allows for a Prolonged Disease Course with High Survival in a Severe Murine Model of Sepsis. Shock (Augusta, Ga.) 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Critical care medicine 2001:29:1303–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayr FB, Yende S, Linde-Zwirble WT, Peck-Palmer OM, Barnato AE, et al. Infection rate and acute organ dysfunction risk as explanations for racial differences in severe sepsis. Jama 2010:303:2495–2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parrillo JE, Parker MM, Natanson C, Suffredini AF, Danner RL, et al. Septic shock in humans. Advances in the understanding of pathogenesis, cardiovascular dysfunction, and therapy. Annals of internal medicine 1990:113:227–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelm M, Schafer S, Dahmann R, Dolu B, Perings S, et al. Nitric oxide induced contractile dysfunction is related to a reduction in myocardial energy generation. Cardiovascular research 1997:36:185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato R, Nasu M A review of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. Journal of intensive care 2015:3:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang LL, Gros R, Kabir MG, Sadi A, Gotlieb AI, et al. Conditional cardiac overexpression of endothelin-1 induces inflammation and dilated cardiomyopathy in mice. Circulation 2004:109:255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parrillo JE, Burch C, Shelhamer JH, Parker MM, Natanson C, et al. A circulating myocardial depressant substance in humans with septic shock. Septic shock patients with a reduced ejection fraction have a circulating factor that depresses in vitro myocardial cell performance. The Journal of clinical investigation 1985:76:1539–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoshino Y, Shioji K, Nakamura H, Masutani H, Yodoi J From oxygen sensing to heart failure: role of thioredoxin. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2007:9:689–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koneru S, Penumathsa SV, Thirunavukkarasu M, Zhan L, Maulik N Thioredoxin-1 gene delivery induces heme oxygenase-1 mediated myocardial preservation after chronic infarction in hypertensive rats. American journal of hypertension 2009:22:183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon YW, Masutani H, Nakamura H, Ishii Y, Yodoi J Redox regulation of cell growth and cell death. Biological chemistry 2003:384:991–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura H, Hoshino Y, Okuyama H, Matsuo Y, Yodoi J Thioredoxin 1 delivery as new therapeutics. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2009:61:303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shioji K, Nakamura H, Masutani H, Yodoi J Redox regulation by thioredoxin in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2003:5:795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gleason FK, Holmgren A Thioredoxin and related proteins in procaryotes. FEMS microbiology reviews 1988:4:271–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ago T, Sadoshima J Thioredoxin and ventricular remodeling. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 2006:41:762–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laurent TC, Moore EC, Reichard P Enztmatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. IV. Isolation and characterization of thioredoxin, the hydrogen donor from Escherichia Coli B. . The Journal of biological chemistry 1964:239:3436–3444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samuel SM, Thirunavukkarasu M, Penumathsa SV, Koneru S, Zhan L, et al. Thioredoxin-1 gene therapy enhances angiogenic signaling and reduces ventricular remodeling in infarcted myocardium of diabetic rats. Circulation 2010:121:1244–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suresh SC, Selvaraju V, Thirunavukkarasu M, Goldman JW, Husain A, et al. Thioredoxin-1 (Trx1) engineered mesenchymal stem cell therapy increased pro-angiogenic factors, reduced fibrosis and improved heart function in the infarcted rat myocardium. International journal of cardiology 2015:201:517–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker CC, Chaudry IH, Gaines HO, Baue AE Evaluation of factors affecting mortality rate after sepsis in a murine cecal ligation and puncture model. Surgery 1983:94:331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang S, Chung CS, Ayala A, Chaudry IH, Wang P Differential alterations in cardiovascular responses during the progression of polymicrobial sepsis in the mouse. Shock (Augusta, Ga.) 2002:17:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wichterman KA, Baue AE, Chaudry IH Sepsis and septic shock--a review of laboratory models and a proposal. The Journal of surgical research 1980:29:189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hubbard WJ, Choudhry M, Schwacha MG, Kerby JD, Rue LW, 3rd, et al. Cecal ligation and puncture. Shock (Augusta, Ga.) 2005:24 Suppl 1:52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oriowo B, Thirunavukkarasu M, Selvaraju V, Adluri RS, Zhan L, et al. Targeted gene deletion of prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 3 triggers angiogenesis and preserves cardiac function by stabilizing hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha following myocardial infarction. Current pharmaceutical design 2014:20:1305–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang HL, Lai TW Optimization of Evans blue quantitation in limited rat tissue samples. Scientific reports 2014:4:6588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emanueli C, Grady EF, Madeddu P, Figini M, Bunnett NW, et al. Acute ACE inhibition causes plasma extravasation in mice that is mediated by bradykinin and substance P. Hypertension 1998:31:1299–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Xu X, Ceylan-Isik AF, Dong M, Pei Z, et al. Ablation of Akt2 protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac dysfunction: role of Akt ubiquitination E3 ligase TRAF6. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 2014:74:76–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weniger M, D’Haese JG, Angele MK, Chaudry IH Potential therapeutic targets for sepsis in women. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets 2015:19:1531–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zellweger R, Wichmann MW, Ayala A, Stein S, DeMaso CM, et al. Females in proestrus state maintain splenic immune functions and tolerate sepsis better than males. Critical care medicine 1997:25:106–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albertsmeier M, Pratschke S, Chaudry I, Angele MK Gender-Specific Effects on Immune Response and Cardiac Function after Trauma Hemorrhage and Sepsis. Viszeralmedizin 2014:30:91–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World CJ, Yamawaki H, Berk BC Thioredoxin in the cardiovascular system. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany) 2006:84:997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castanares-Zapatero D, Bouleti C, Sommereyns C, Gerber B, Lecut C, et al. Connection between cardiac vascular permeability, myocardial edema, and inflammation during sepsis: role of the alpha1AMP-activated protein kinase isoform. Critical care medicine 2013:41:e411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan SY RR. R Regulation of Endothelial Barrier Function. San Rafael (CA): Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; Chapter 7, Pathophysiology and Clinical Relevance; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Escobar DA, Botero-Quintero AM, Kautza BC, Luciano J, Loughran P, et al. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activation protects against sepsis-induced organ injury and inflammation. The Journal of surgical research 2015:194:262–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng G, Lyu J, Liu S, Huang J, Liu C, et al. Silencing of uncoupling protein 2 by small interfering RNA aggravates mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiomyocytes under septic conditions. International journal of molecular medicine 2015:35:1525–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Narayan V, Kudva AK, Prabhu KS Reduction of Tetrathionate by Mammalian Thioredoxin Reductase. Biochemistry 2015:54:5121–5124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cabrera-Perez J, Babcock JC, Dileepan T, Murphy KA, Kucaba TA, et al. Gut Microbial Membership Modulates CD4 T Cell Reconstitution and Function after Sepsis. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 2016:197:1692–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]