Abstract

Filoviridae, including Ebola (EBOV) and Marburg (MARV) viruses, are emerging pathogens that pose a serious threat to public health. No agents have been approved to treat filovirus infections, representing a major unmet medical need. The selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) toremifene was previously identified from a screen of FDA-approved drugs as a potent EBOV viral entry inhibitor, via binding to EBOV glycoprotein (GP). A focused screen of ER ligands identified ridaifen-B as a potent dual inhibitor of EBOV and MARV. Optimization and reverse-engineering to remove ER activity led to a novel compound 30 showing potent inhibition against infectious EBOV Zaire (0.09 μM) and MARV (0.64 μM). Mutagenesis studies confirmed that inhibition of EBOV viral entry is mediated by direct interaction with GP. Importantly, compound 30 (XL-147) displayed broad-spectrum anti-filovirus activity against Bundibugyo, Tai Forest, Reston, and Měnglà viruses, and is the first sub-micromolar antiviral agent reported for some of these strains, therefore warranting further development as a pan-filovirus inhibitor.

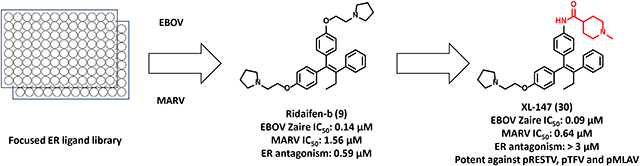

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Ebolavirus, Marburgvirus, Cuevavirus, and Dianlovirus in the family Filoviridae1, 2 are enveloped negative-sense RNA viruses that are known to cause pathogenic and apathogenic human infections. Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV), Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV), Bundibugyo ebolavirus (BDBV), Tai Forest ebolavirus (TFV), and all species in the Marburgvirus genus (Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV)) can cause a highly lethal hemorrhagic fever with an average 50% (25%−90%) mortality rate in infected patients.3–5 Reston ebolavirus (RESTV), Lloviu virus (LLOV, assigned the genus Cuevavirus), and Měnglà virus (MLAV, assigned the genus Dianlovirus) are apathogenic in humans. The public became more aware of the devastation caused by this family of viruses during the 2014 EBOV outbreak in West Africa, resulting in ~11,000 fatalities.6 In August 2018, yet another outbreak of EBOV Zaire was declared in the Democratic Republic of Congo. As of February 2020, there have been more than 3,400 cases and 2,250 deaths despite a ring vaccination program with the FDA-approved Merck vaccine rVSV-ZEBOV (ERVEBO®),7 underlining the urgency for developing effective antiviral agents to prevent or eradicate these lethal infections.

All filoviruses have a 19 kb genome that encodes for at least seven proteins8 the nucleoprotein (NP), glycoprotein (GP), four structural viral proteins VP24, VP30, VP35, VP40, and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L). The filovirus GP is a “Type I” viral transmembrane glycoprotein that is solely responsible for viral entry.9–11 The GP protein consists of two subunits, GP1 and GP2. GP1 mediates receptor binding and viral tropism, while GP2 regulates GP-mediated viral/cell membrane fusion. The subunits of the GP protein form a homotrimer of GP1/GP2 heterodimers. GP mediated entry begins once the virus attaches to the target cell surface (macrophages, dendritic cells, and monocytes) through several types of interactions that utilize either the glycans (e.g. glycosaminoglycans; GAGs) present on the viral GP1 subunit as reported from our lab and other groups12, 13 or phosphatidylserine located in the viral envelope.14 Once internalized the virions are trafficked through early endosomes to late endosomes and proteolytically cleaved by host cysteine proteases cathepsin B and L. The processed GP binds to the late endosomal/lysosomal receptor Niemann-Pick Type C1 (NPC1) receptor at its second luminal domain (domain C),15–19 which then triggers the viral membrane and endosomal membrane fusion events. Collectively, the EBOV GP is essential for viral entry and in many phases of the virus replication cycle, highlighting it as a promising target for the development of novel therapeutics.

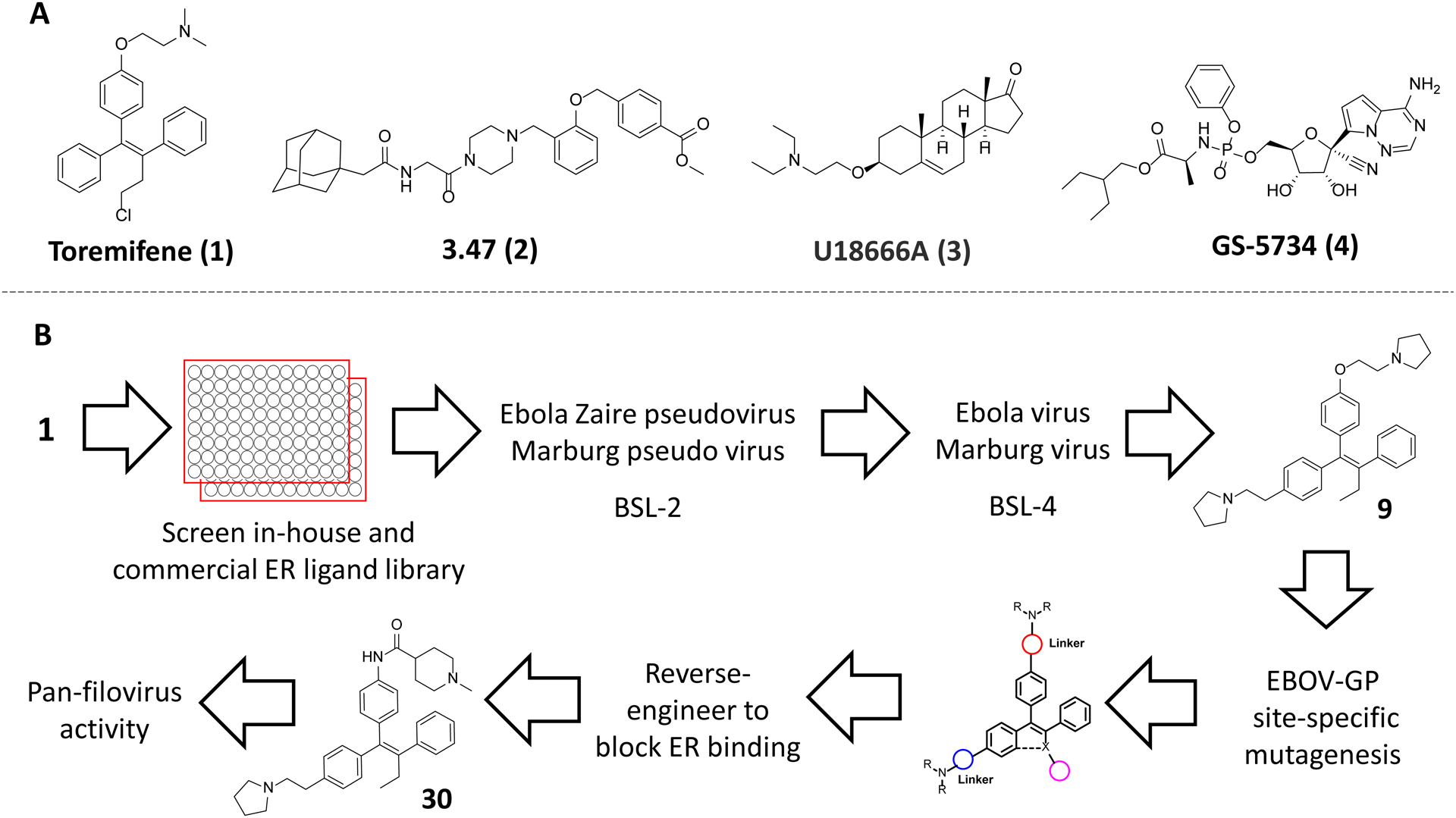

To date, diverse small molecule inhibitors targeting multiple mechanisms of the filovirus replication cycle have been reported, including compounds 3.47 (2)15 and U18666A (3)20 that are suggested to block the interaction between NPC1 and the GP. The antiviral agent, remdesivir (GS-5734; 4),21 inhibits the function of EBOV’s RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Figure 1A). In addition, our group has previously conducted multiple high throughput screens of various small molecule libraries; we identified G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) antagonists and antihistamines as anti-filovirus entry inhibitors.22–26 However, only limited examples of inhibitors that bind directly to the GP have been reported.27, 28

Figure 1.

A) Representative structures of EBOV and MARV inhibitors; B) workflow of this study.

In 2013, the screening of a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drug library revealed selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) as potent entry inhibitors of EBOV, SUDV, and MARV.29 In addition, the two most potent inhibitors, SERMs clomiphene and toremifene (1), showed in-vivo efficacy. A mouse-adapted model of EBOV Zaire was treated with clomiphene or 1 resulting in 90% and 50% mouse survival, respectively. Furthermore, anti-filovirus efficacy in cell cultures was not dependent on ER. By co-crystallization, 1 was shown to bind directly to the prefusion sate of the EBOV GP.30 Binding is through a cavity formed between GP1 and GP2 normally occupied by the fusion-loop of GP2. The GP co-crystal structure provides a structural basis for the design of next-generation antiviral agents for filoviruses and also incentivized us to screen for inhibition of viral entry by ER ligands developed in our labs and by others.31–35

Herein, we report a focused screen of ER ligands with various functions and diverse chemical scaffolds. This screen identified a potent pan-filovirus inhibitor, Ridaifen-B (9) that also has SERM-like activity at ER. Optimization and reverse-engineering of 9 provided a novel pan-filovirus inhibitor devoid of activity at ER, which might lead to unwanted side effects. Furthermore, multiple site-specific mutation studies on EBOV-GP revealed that the mechanism of EBOV antiviral action is mediated by binding to GP.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Screening ER ligands against pseudovirus model of EBOV and MARV.

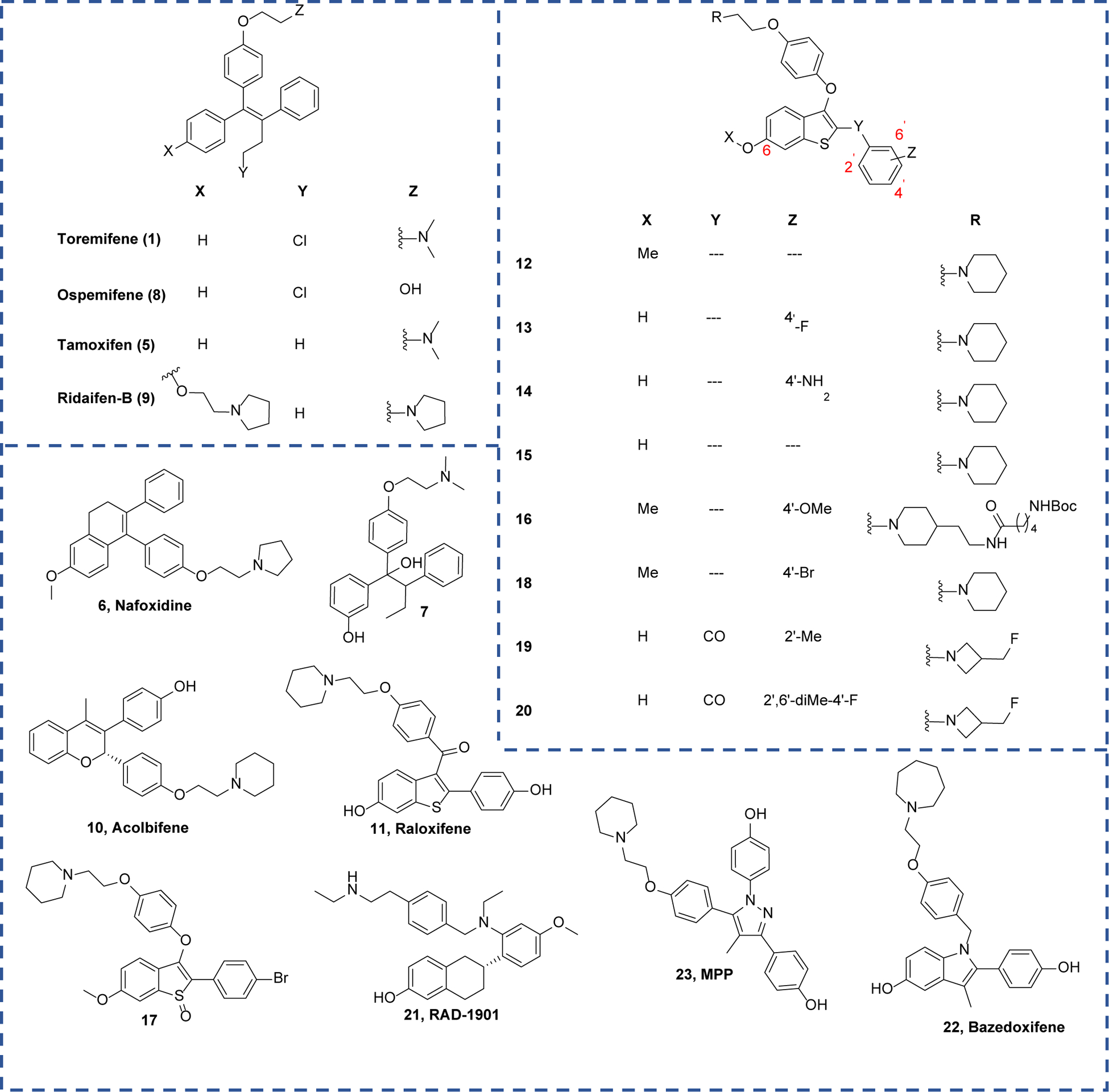

A previous screen of 2,600 compound FDA-approved drug library identified the SERM, 1, as a potent antiviral agent against EBOV.29 This library contained a small number of FDA-approved drugs that act as ER ligands with limited chemical diversity, including steroids (e.g., ethinyl estradiol), triphenylethylenes (e.g. 1 and tamoxifen; 5), and a benzothiophene (raloxifene; 11). Thus, a meaningful structure-activity relationship (SAR) could not be drawn from these observations to support further chemical optimization. Furthermore, most screening efforts focused on EBOV Zaire and consequently ignored molecules with potential to inhibit MARV or other viruses in the Filoviridae family. To gain a comprehensive view of which ER ligands have broadly acting anti-filovirus activity, we performed a screen of 58 ER ligands with diverse scaffolds. To identify candidate compounds a robust human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pseudotype model with the EBOV GP and MARV GP was used. This allowed for direct comparison of GP function with a common lentiviral core and reporter. In addition, it avoids the need to handle the infectious viruses in biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) facilities.11, 36, 37 All compounds were screened at nine concentrations ranging from 0.4 to 100 μM. Hits with below 2 μM potency were retested to obtain accurate IC50 values. The ER ligands assayed include diverse chemical scaffolds such as triphenylethylene, 2-arylbenzothiophene, 2-benzoylbenzothiophene, 2-arylindole, dihydronaphthalene, tetrahydronapthalene, and triaryl-substituted pyrazole. These molecules also display diverse pharmacology at ER including as agonists, partial agonists, antagonists, and degraders (SERDs).

Out of 58 compounds assayed, 20 ER ligands exhibited potency (IC50) superior to 2 μM against pseudotyped EBOV (pEBOV), and 14 compounds gave IC50 < 1 μM (Table 1 and Figure 2). The overall high hit rate of the ER ligands implies that there is a general similarity between the structure of the ER ligand binding pocket and the hydrophobic cleft of EBOV GP. In contrast, of 16 molecules identified with IC50 < 2 μM against pseudotyped MARV (pMARV), only five showed IC50 values < 1 μM. Clearly, differences exist between the binding site for these viral entry inhibitors in EBOV versus MARV and it is possible that the specific binding sites of these small molecules may not be shared between EBOV and MARV. This interpretation is compatible with a structural study that showed the loop containing the “DFF lid” between β13-β14 in MARV-GP is not proteolytically cleaved, and thus blocks access of these small molecules to the binding pocket identified for 1 in EBOV-GP.38 Furthermore, we observed no correlation between ER binding/activity and anti-filovirus activity. For example, compound 22 and 23 strongly bind to the ER with Kd values of 0.37 nM and 1.8 nM, respectively. These compounds are 10–20 fold weaker than compound 5 against pEBOV, albeit compound 5 having an ER affinity of 13.8 nM.39, 40 This is consistent with earlier findings that the anti-EBOV activity of 1 was observed in multiple ER negative cell lines, demonstrating the anti-EBOV activity is independent of ER signaling.29

Table 1:

Anti-filovirus properties of ER ligands against pEBOV Zaire (Mayinga variant) and pMARV (Musoke variant).

| Compound | IC50 (μM) pEBOV |

IC50 (μM) pMARV |

SI pEBOV |

SI pMARV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Toremifene) | 0.07 ± 0.05 | 2.60 ± 0.70 | 229 | 6 |

| 5 (Tamoxifen) | 0.10 ±0.06 | 1.81 ± 0.35 | 336 | 19 |

| 6 (Nafoxidine) | 0.10 ± 0.009 | 1.30 ± 0.08 | 82 | 6 |

| 7 | 1.74 ± 0.55 | 4.40 ± 2.55 | 22 | 9 |

| 8 (Ospemifene) | 3.80 ± 1.60 | 34.35 ± 2.70 | 7 | <1 |

| 9 (Ridaifen-B) | 0.02 ± 0.006 | 0.61 ± 0.05 | 405 | 13 |

| 10 (Acolbifene) | 1.50 ± 0.30 | 0.90 ± 0.40 | 11 | 19 |

| 11 (Raloxifene) | 1.24 ± 0.50 | 2.20 ± 0.97 | 19 | 11 |

| 12 | 0.26 ± 0.07 | 3.18 ± 1.96 | 88 | 8 |

| 13 | 0.98 ± 0.22 | 2.04 ± 0.98 | 15 | 7 |

| 14 | 0.13 ± 0.05 | 1.45 ± 0.74 | >770 | >69 |

| 15 | 0.30 ± 0.17 | 0.67 ± 0.15 | 45 | 20 |

| 16 | 0.80 ± 0.30 | 0.60 ± 0.20 | 57 | 76 |

| 17 | 2.14 ± 1.20 | 1.81 ± 0.43 | >47 | >55 |

| 18 | 0.63 ± 0.25 | 1.25 ± 0.50 | 74 | 37 |

| 19 | 1.02 ± 0.11 | 3.88 ± 0.73 | 27 | 7 |

| 20 | 1.32 ± 0.25 | 1.87 ± 0.97 | 21 | 15 |

| 21 (RAD-1901) | 0.24 ± 0.25 | 1.30 ± 0.04 | 44 | 8 |

| 22 (Bazedoxifene) | 2.24 ± 0.31 | 3.83 ± 0.36 | 10 | 6 |

| 23 (MPP) | 1.31 ± 0.23 | 1.19 ± 1.10 | 11 | 12 |

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of top active hits shown in Table 1.

SAR Analysis of Top Hits

Consistent with earlier reports, triphenylethylene-based positive control compounds, 1 and 5, demonstrated high potency against pEBOV with IC50 < 0.10 μM. Both compounds were 10-fold weaker against pMARV, in accord with earlier reports.29 A fused-ring analog of 1, nafoxidine (6), showed a loss of potency against both pEBOV and pMARV (IC50 = 0.10 μM and 1.30 μM, respectively). However, compound 7 that breaks the rigidity of the triphenylethylene system, through a sp3-centered ethoxy linker, further lost potency against pEBOV (IC50 = 1.74 μM). Interestingly, the anti-pMARV potency of compound 7 was not significantly right-shifted compared to 1. This data supports the highly hydrophobic nature of the EBOV-GP binding pocket.

Ospemifene (8), a close analog of 1, without a basic amine sidechain, lost potency and lost antiviral efficacy against both pEBOV and pMARV.41 It is worth noting that although the basic amine moiety is necessary for the anti-filovirus activity, simple alkylamines are not viral entry inhibitors. Acolbifene (10)42 is another fused-ring analog of 1 with a basic amine side chain and is a SERM with potent ER antagonist activity. However, it is more than 20-fold weaker than 1 in inhibiting pEBOV, suggesting substitutions at positions 3 and 4 are preferred over positions 2 and 3 in the chromenol ring. Interestingly, triphenylethylene-based 943 with a dual basic amine chain showed potent inhibition against both pEBOV (IC50 = 0.02 μM) and pMARV (IC50 = 0.61 μM), hinting at a novel GP binding that interacts with the secondary basic amine side chain.

Since our group has focused on benzothiophene-based ER ligands, this chemotype is prevalent in our library. Ten benzothiophene-based ER ligands with antagonist activity were highly potent against pEBOV, displaying 0.1 μM < IC50 < 2 μM (Table 1). Like triphenylethylene-based ER ligands, benzothiophene-based ER ligands are generally weaker against pMARV (0.6 μM < IC50 < 3 μM). The prototype benzothiophene-based ER antagonist, raloxifene (11) with a 3-benzoyl substitution, exhibited IC50 values of 1.24 μM and 2.2 μM against pEBOV and pMARV, respectively; 10-fold weaker than potency observed for 1 in pEBOV. Likewise, 2-benzoyl substituted analogs, 19 and 20, also lacked potency against both pEBOV (IC50 = 1.02 μM and 1.32 μM, respectively) and pMARV (IC50 = 3.88 μM and 1.87 μM, respectively).

Oxidation of the benzothiophene core in compound 17 led to a three-fold decline in IC50 compared to unoxidized compound 16. This finding is consistent with the decreased potency from adding a polar group to the core of triphenylethylene-based inhibitor 7. In contrast, a 3-phenoxy substituted compound (12) is significantly more potent than 11 and 19 against pEBOV (IC50 = 0.26 μM), confirming that a more hydrophobic scaffold is preferred. Modifications at positions 6 and 4’ on the 2-phenylbenzothiophene core in compounds 12-15 slightly altered the antiviral potency (IC50 = 0.13 μM – 1 μM), indicating these two positions could be further modified to fine-tune druggability if needed (Figure 2). Surprisingly, compound 16 with a lengthy Boc-protected side chain was a potent inhibitor against both pEBOV and pMARV, signifying that the bulky side chain of 16 may extend to either a solvent exposed surface or a potential new binding site. Compound 15 was the most potent of the benozothiophene ER ligands against both pseudoviruses, although marginally less potent than 9.

Indole-based ER antagonist, bazedoxifene (22),44 is a core component of FDA-approved drug, Duavee, for the treatment of postmenopausal syndromes, including hot flashes. This molecule showed a significant loss of inhibition in both pEBOV and pMARV (IC50 = 2.24 μM and 3.83 μM, respectively) compared to triphenylethylene- or benzothiophene-based inhibitors. This is likely caused by either the large size of the azepane ring or the subtle electron changes of the indole core compared to the benzothiophene core. Triaryl-substituted pyrazole-based ER antagonist, MPP (23)45, also showed a significant decrease in potency compared to 1 against pEBOV (IC50 = 1.31 μM). This indicates that this triaryl system is likely not suitable for further development. RAD-1901 (21) with a more hydrophobic tetrahydronapthalene core was potent against both pEBOV and pMARV (IC50 = 0.24 μM and 1.30 μM, respectively) again supporting the need for the general high hydrophobicity required for the central scaffold.

Confirmation of Top Hits Against Infectious EBOV and MARV

Using infectious EBOV Zaire (Kikwit variant) and MARV (Angola variant) we confirmed the efficacy and potency of seven hits with strong dual inhibition of pEBOV and pMARV (IC50 < 1 μM) and favorable SI (Table 2). The potency of the positive control 1, was consistent with the previous report (EBOV IC50 = 0.84 μM; MARV IC50 = 3.90 μM).29 Compounds with favorable potency and SI values were selected for infectious testing. The benzothiophene-based hits demonstrated comparable potency to 1 against infectious EBOV (IC50 = 0.97 μM – 1.63 μM). However, the benzothiophene series suffered a significant loss of activity against infectious MARV; for example, for the most potent compound in the series, 12, EBOV IC50 = 0.97 μM versus MARV IC50 > 6.25 μM. Compound 19 has a 2-benzoylthiophene scaffold and surprisingly the activity observed in pseudoviruses was entirely lost against both EBOV and MARV. The discrepancy in the potency of 19 between the pseudovirus and the infectious virus might be due to the use of different host cells (A549 vs Hela) in each assay and was not explored further. It should be noted that the decrease in potency of infectious virus compared to pseudovirus may also be due to the increased GP density on the surface of the infectious virus filaments.46, 47

Table 2:

Confirmation of anti-filovirus properties of toremifene and its derivatives against infectious EBOV Zaire (Kikwit variant) and MARV (Angola variant).

| Compound | IC50 (μM) EBOV |

IC50 (μM) MARV |

SI EBOV |

SI MARV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Toremifene) | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 3.90 ± 0.82 | 35 | 7.5 |

| 6 (Nafoxidine) | 1.00 ± 0.04 | >6.25 | 22 | <4 |

| 9 (Ridaifen-B) | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 1.56 ± 0.49 | 247 | 22 |

| 12 | 0.97 ± 0.1 | >6.25 | 20 | <3 |

| 14 | 1.63 ± 3.4 | >6.25 | 18 | <5 |

| 15 | 1.14 ± 0.02 | >6.25 | 15 | <3 |

| 19 | >6.25 | >6.25 | <5 | <5 |

Compound 6, the fused-ring analog of 1 exhibited a comparable potency to 1 (IC50 = 1.00 μM) against EBOV but again lost potency against MARV (IC50 > 6.25 μM). Interestingly, compared to the pseudovirus assays the triphenylethylene-based 9 was more potent against infectious virus and was significantly more potent than 1 in inhibiting MARV (EBOV IC50 = 0.14 μM; MARV IC50 = 1.56 μM). Compound 9 has a favorable 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of 8.1 μM in A549 cells (Table S2). The selectivity index (SI, CC50/IC50) is a cell-based measure of “therapeutic index” and is the most favorable for 9. Overall, compound 9 is an improved lead compound compared to 1 and a better candidate for further chemical optimization as a potential pan-filovirus antiviral treatment.

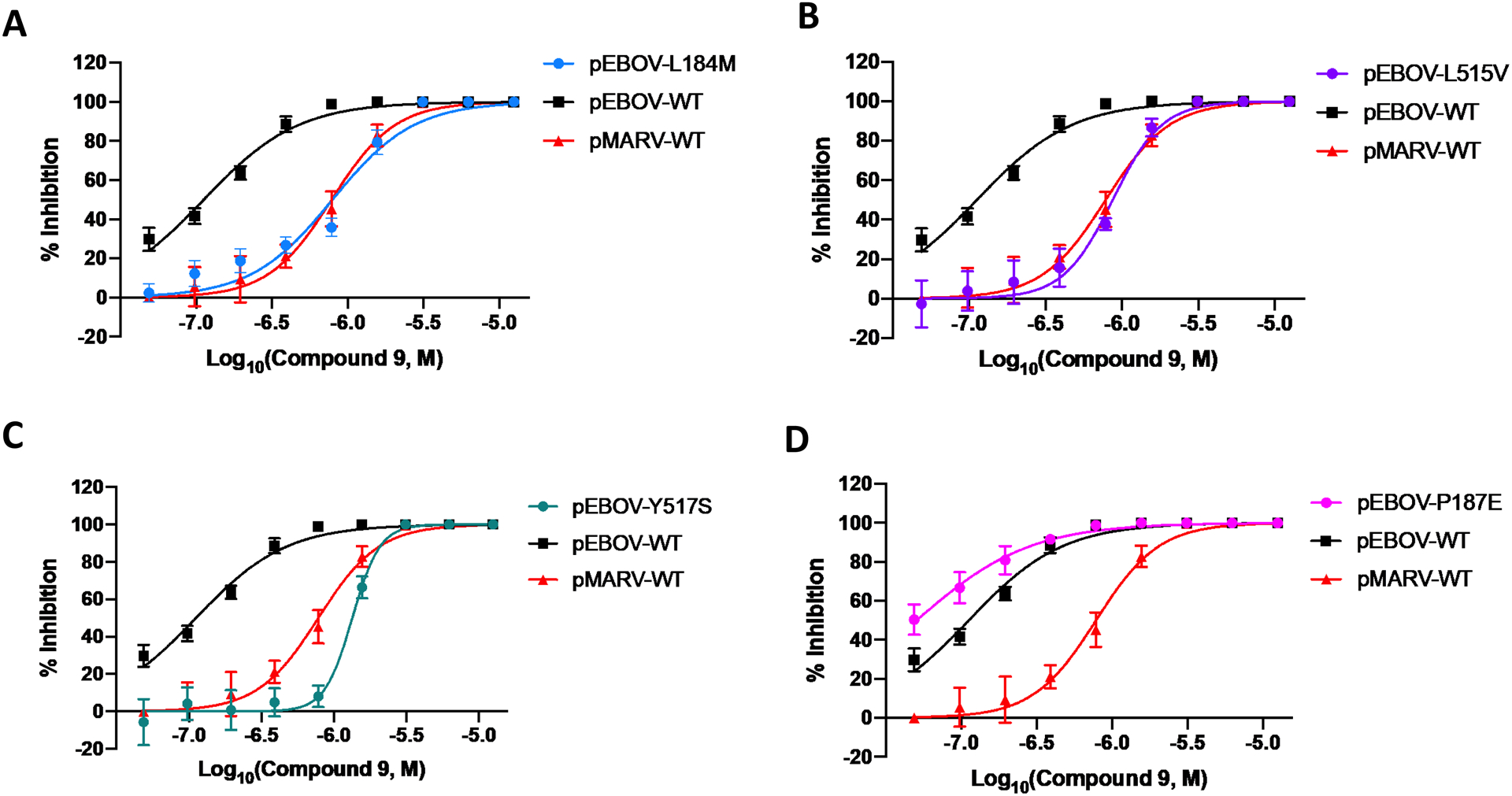

Site-specific mutation of EBOV GP supports GP binding as mediating inhibition of viral entry.

We next used the single amino acid mutagenesis of pEBOV GP to understand the molecular basis of entry inhibition by compound 9. We previously showed that the pEBOV GP Y517S mutation results in a significant loss of potency towards 1 when compared to WT GP, which is expected, because the co-crystal structure of 1 shows an edge-to-face interaction with Tyr-517. Furthermore, the right-shift of the response to 1 in pEBOV GP mutant Y517S results in a pMARV-like response curve. Similarly, the response to 9 of the pEBOV GP Y517S mutant was a right-shift to a pMARV-like response curve (Figure 3). Two additional pEBOV GP mutations, L184M and L515V, also caused a right-shift and a 10-fold loss of potency in response to 1 and 9. Mutation of GP Pro-187, on the outer edge of the toremifene binding pocket, was not anticipated to perturb the binding of 9. Interestingly, the pEBOV GP mutant P187E showed a modest left-shift of the dose-response curve, suggesting the secondary pyrrolidine chain of 9 might develop an electrostatic interaction with the Glu-187 residue in the mutant. Four other EBOV GP mutations were studied, specific to residues in the vicinity of the basic side chain of 1 in the co-crystal structure (R64K, V66M, E100D, and T520S; Figure S2) leading to concentration-response curves for 9 which were not right-shifted to the extent observed for L184M, L515V, and Y517S. Indeed, the E100D mutation, which might be expected to cause the loss of a salt-bridge with 1 and 9, caused no significant change in the response to inhibition of viral entry elicited by 9. Taken together, the site-specific mutations to residues in the vicinity of the basic amine side chain of 1, and presumably one of the basic amine side chains of 9, indicated that chemical optimization at the side chain of compound 9 could lead to more potent inhibitors.

Figure 3. EBOV-GP site-specific mutation causes right-shift in response to 9 confirming interaction with toremifene-binding pocket in EBOV-GP.

Mutation of residues L184 (A), L515 (B), and Y517 (C), in the toremifene-binding pocket of EBOV-GP, right-shifts the response to 9 to mimic the response to 9 in WT MARV that does not contain a high affinity toremifene-binding site. Mutation of EBOV-GP residue P187 (D) showed a possible small left-shift that may be associated with an electrostatic interaction of the secondary pyrrolidine chain of 9 with the P187E residue. Dose-response curves for pseudotyped viruses shows mean and S.D. from three independent experiments.

The mechanism of antiviral activity of 9 against MARV is more intriguing as the toremifene-binding site is physically blocked in the MARV GP prefusion state. We and others have recently reported the heptad-repeat 2 (HR2) domain of the EBOV GP and MARV GP as a potential binding site for small molecules that inhibit viral entry.48 However, compound 9 when screened against HR2 MARV mutant I627V manifested a small two-fold loss of potency (Figure S3), which does not fully support binding of 9 to the HR2 site as directly causing inhibition of pMARV viral entry by 9.

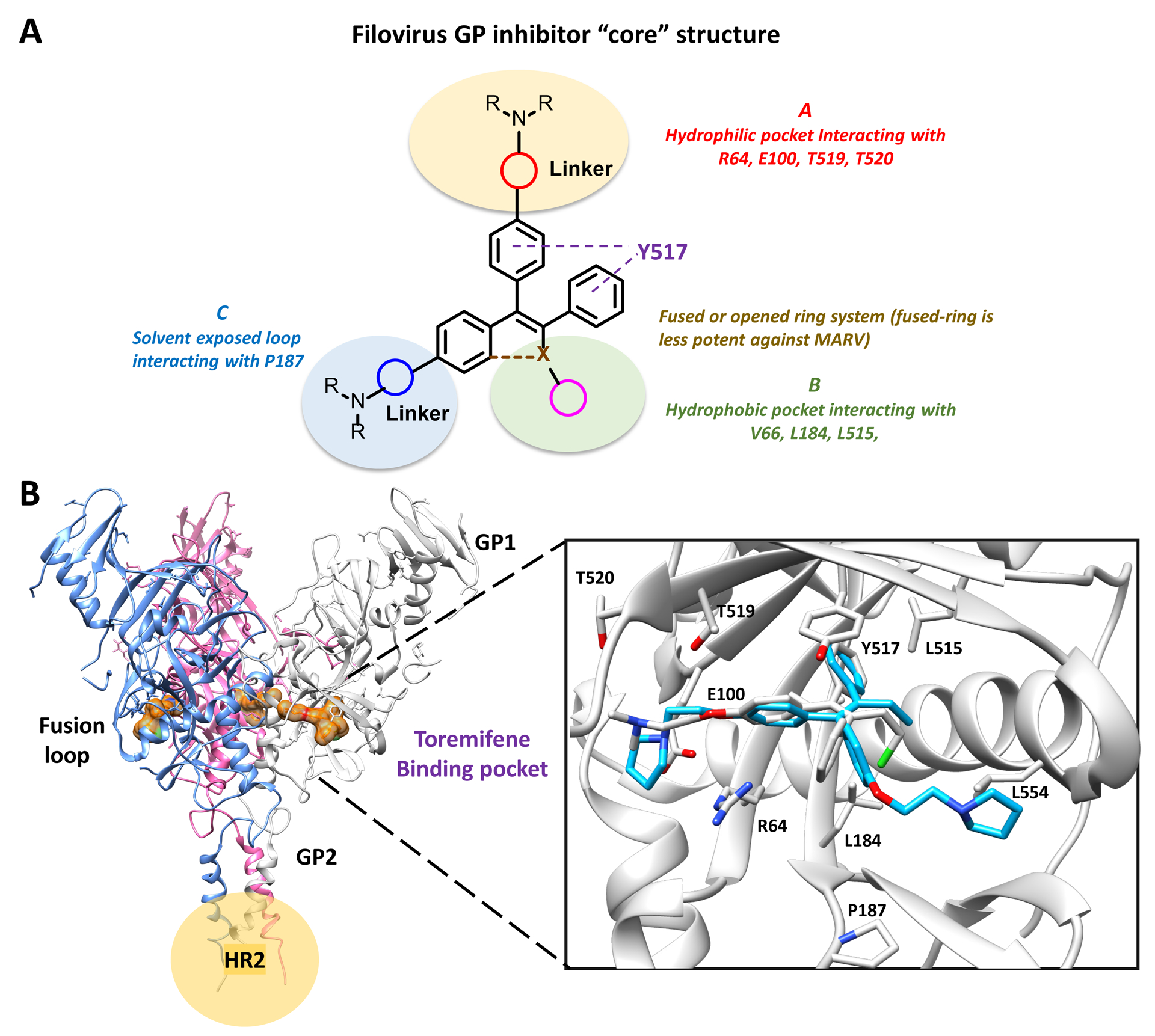

The SAR, supported by the mutagenesis studies, led us to propose a general EBOV-GP binding pose and a pharmacophore model to guide further optimization (see Figure 4; the docking model of 9 is based on PDB ID: 5JQ7). The pharmacophore model features a triaryl system either linked by an alkene or a direct C-C linkage between aryl and heteroaryl groups that interact with the general hydrophobic pocket of the GP DFG lid (including residues Y517, V66, L184, L515, and L558). The basic-amine side chain A binds to the GP in the vicinity of highly hydrophilic residues R64, E100, T519, and T520. As indicated by the mutagenesis studies, this chain can be further optimized for hydrogen-bonding and electrostatic interactions with the surrounding hydrophilic residues.

Figure 4: Summary of SAR and GP inhibitors “core” features.

(A) The core structure highlights an open or fused triaryl system, wherein both scaffolds have comparable potency against EBOV, while the open ring system favors MARV inhibition. The basic-amine side chain A binds to the GP in the vicinity of highly hydrophilic residues such as R64, E100, T519 and T520, modifications at this position can improve hydrogen-bonding and electrostatic interactions with the surrounding hydrophilic residues. The hydrophobic pocket formed at region B is relatively flexible; modification at this site with methyl or halogens might further improve potency. Side chain C is in the fusion loop of the GP and is positioned in a solvent-exposed pocket; modifications at this position might have better electrostatic interaction and better drug-like property. (B) Modeling of compound 9 binding to toremifene-binding pocket at EBOV GP. Key residues are shown and labeled. The secondary basic amine side chain is positioned in a solvent-exposed pocket close to P187 (PDB ID: 5JQ7).

The hydrophobic pocket formed at region B by residues V66, L184, L515, and L554, is relatively flexible as observed in recent crystal structures.49 Side chain C interacts with residues P187 or D192 in the fusion loop of the GP and is positioned in a solvent-exposed pocket. The gain of function P187E mutation suggests the pyrrolidine may sit closer to P187 than in the docking pose shown (Figure 4B) and further modification might yield better intermolecular interactions and be exploited to incorporate improved drug-like properties. It is worth noting that although inhibitors with a fused-ring system (e.g. 6 and 12) showed comparable potency to inhibitors with an open-ring scaffold (e.g. 1), they were less potent against MARV. Using information gained from this model, 11 novel compounds were created in an effort to increase the potency of 9. Notably, several of the modifications indicated by the pharmacophore model could be exploited to reverse engineer 9 to remove the unwanted activity mediated by ER binding.

Reverse-engineering of ER activity.

All hits from the screen of ER ligands interact with ER and modulate ER signaling, which is undesired in an improved antiviral agent. For example, ER agonists can be expected to have feminizing actions, whereas ER antagonists can cause chemical menopause; moreover, even weak ER ligands influence cellular homeostasis by interaction with extranuclear ER. In order to ablate ER-mediated side-effects, we incorporated in our chemical optimization campaign modifications to the preferred hit 9, anticipated to block activity via ER binding. Based on the co-crystal structure of 5 with ERα, and our extensive experience designing potent ER ligands, it is evident that the basic amine side chain of 9 binds in a narrow channel formed by L525, T347, and W383 between helix-3 and helix-11 of ERα (Figure S4). We hypothesized that modification of the ethoxy linker of compound 9 would disrupt binding to ERα. Support for this hypothesis can be seen in the reported amide analog of 5 that significantly lost activity at ER,50 hence, we chose the amide analogs of compound 9 as the primary synthetic targets.

In parallel to reverse-engineering to remove ER binding, modifications were made to increase affinity for the EBOV GP. The co-crystal structure of 1 and mutagenesis studies on both 1 and 9 confirm that the ethoxy linker of the amine side chain interacts with hydrophilic residues such as R64, E100, and T519 in EBOV GP. This further supports the incorporation of an amide linker to gain hydrophilic interactions with these residues that will likely maintain or enhance the binding affinity to GP.

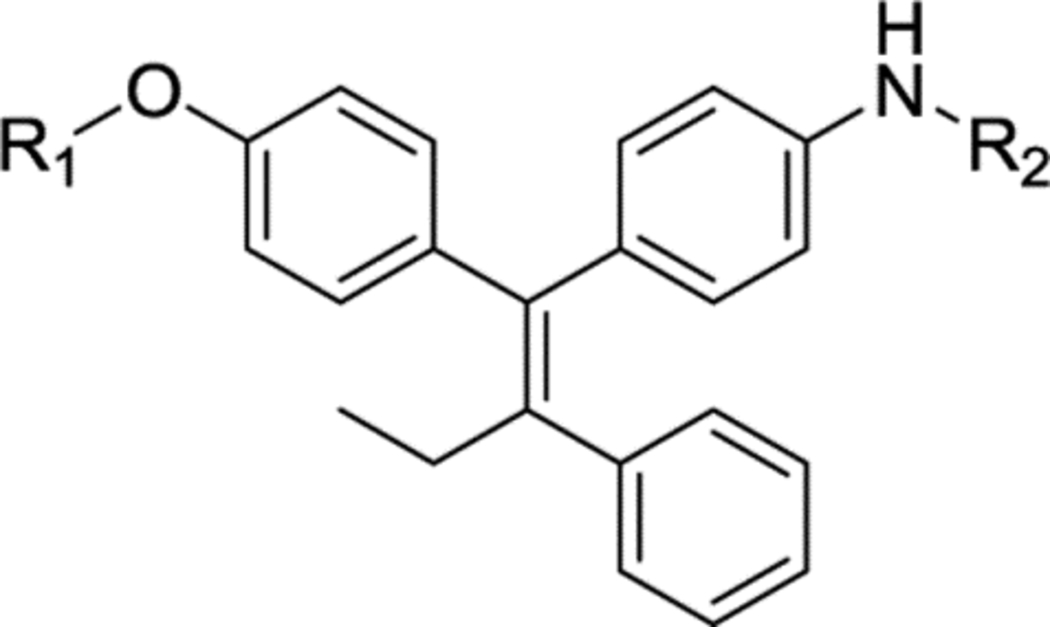

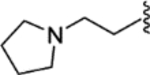

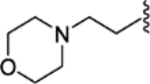

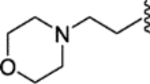

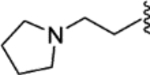

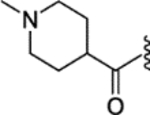

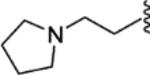

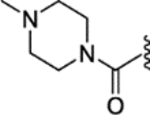

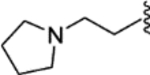

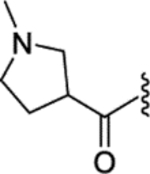

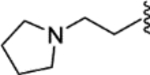

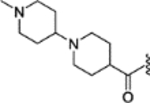

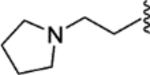

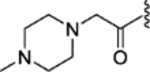

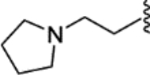

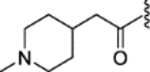

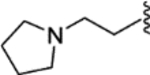

Novel compound 27, represents the parent aniline scaffold chosen to explore EBOV antiviral agents with amide side chains. Compound 27 showed comparable potency to 9 in the pEBOV and pMARV assays (Table 3); however, it was 10-fold weaker than 9 in the EBOV infectious virus assay (Table 4). Compounds 28 and 29 with an ethylamine linked to a pyrrolidine or morpholine group also suffered significant potency loss in either pseudovirus or infectious virus assays. As predicted from the pharmacophore model, converting the ethylamine to an amide linked piperidine in compound 30 (XL-147) significantly improved the potency against pEBOV (IC50 = 0.01 μM) and also led to significantly improved potency against infectious EBOV and MARV (IC50 = 0.09 μM and 0.64 μM, respectively). Compound 30 is 10-fold more potent than 1 against infectious EBOV and 6-fold more potent against infectious MARV.

Table 3:

Anti-filovirus properties of novel toremifene derivatives against HIV pseudotyped pEBOV Zaire (Mayinga variant) and pMARV (Musoke variant).

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | IC50 (μM) pEBOV | IC50 (μM) pMARV | SI pEBOV | SI pMARV | |

| 9 | N/A | N/A | 0.02 ± 0.006 | 0.61 ± 0.05 | 405 | 13 |

| 27 |  |

-H | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 1.07 ± 0.50 | 147 | 18 |

| 28 |  |

|

0.33 ± 0.20 | >12.50 | 79 | <2 |

| 29 |  |

|

0.23 ± 0.15 | 2.18 ± 0.51 | 111 | 12 |

| 30 |  |

|

0.01 ± 0.005 | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 590 | 11 |

| 31 |  |

|

0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.75 ± 0.13 | 740 | 30 |

| 32 |  |

|

0.02 ± 0.003 | 0.72 ± 0.12 | 590 | 16 |

| 33 |  |

|

0.18 ± 0.09 | 2.05 ± 0.70 | 79 | 7 |

| 34 |  |

|

0.01 ± 0.009 | 0.42 ± 0.17 | 1400 | 33 |

| 35 |  |

|

0.006 ± 0.004 | 0.62 ± 0.13 | 1397 | 14 |

| 36 |  |

|

0.35 ± 0.09 | 1.21 ± 0.29 | 47 | 13 |

| 37 |  |

|

0.74 ± 0.33 | 4.23 ± 1.47 | 40 | 6 |

Table 4:

Confirmation of anti-filovirus properties of novel toremifene derivatives against infectious EBOV Zaire (Kikwit variant) and MARV (Angola variant).

| Compound | IC50(μM) EBOV | IC50(μM) MARV | SI EBOV | SI MARV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 3.90 ± 0.82 | 35 | 7.5 |

| 9 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 1.56 ± 0.49 | 247 | 22 |

| 27 | 1.64 ± 0.13 | 1.78 ± 2.01 | 15 | 14 |

| 28 | 5.81 ± 0.83 | >25 | 8 | <2 |

| 29 | 2.34 ± 0.21 | 2.90 ± 0.15 | 30 | 25 |

| 30 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.64 ± 0.12 | 124 | 18 |

| 31 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 1.06 ± 0.15 | 43 | 7 |

| 32 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.96 ± 0.22 | 31 | 4 |

| 33 | 0.22 ± 0.004 | 1.07 ± 0.06 | 25 | 5 |

| 34 | 0.21 ± 0.11 | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 31 | 18 |

| 35 | 0.18 ± 0.0006 | 0.87 ± 0.002 | 22 | 6 |

| 36 | 1.49 ± 0.13 | 2.80 ± 0.11 | 15 | 8 |

| 37 | 5.00 ± 0.86 | 3.24 ± 0.63 | 9 | 14 |

Anilides 31 and 32 with a piperazine ring or pyrrolidine ring were also very potent against infectious EBOV (IC50 = 0.16 μM and 0.13 μM, respectively) and MARV (IC50 = 1.06 μM and 0.96 μM, respectively). Compound 33 that extends a second piperidine ring from 30 was significantly less potent, although retaining favorable potency in the infectious virus assays. The introduction of a methylene group into 30 and 31 led to compound 34 and 35, which showed comparable potency. Morpholine-based analogs 36 and 37, although active, did not result in improved potency. In conclusion, compounds 30 and 32 were chosen for further analysis due to potency against pseudovirus and infectious EBOV and MARV. Furthermore, compounds 30 and 32 showed a similar toxicity profile to compound 9 in A529 cells (CC50 = 5.9 μM and 11.8 μM, respectively; Table S2). Compared to one of the most potent filovirus inhibitors reported, compound 1, both compounds were more potent against both viruses and show potential as pan-filovirus antiviral agents.

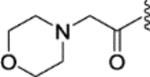

To investigate the mechanism of action of, 30 and 32, we conducted mutagenesis studies similar to those conducted for hit compound 9. Similarly, to compound 9, the responses to both 30 and 32 were strongly right shifted in pEBOV GP mutants L184M, L515V, and Y517S, leading to potency very similar to that observed against pMARV (Figure 5). This loss of potency confirms the interaction of these compounds with the toremifene-binding pocket of EBOV GP and shows that the increased potency in inhibition of EBOV viral entry relative to MARV is driven by direct binding to the same site in GP that binds 1 and 9 (Figure 5). These studies prove that the rational design of compounds 30 and 32 to exploit the 1 binding pocket was successful, generating novel inhibitors with increased potency, which also demonstrate increased potency against MARV.

Figure 5. The Mutagenesis study of the EBOV toremifene-binding pocket confirms compound 30 and 32 directly interact with GP.

Residues L184M (A), L515V(B), and Y517S (C) are essential residues for binding that produce a MARV-like dose response curve compared to pseudeotyped WT EBOV and WT MARV. All error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments.

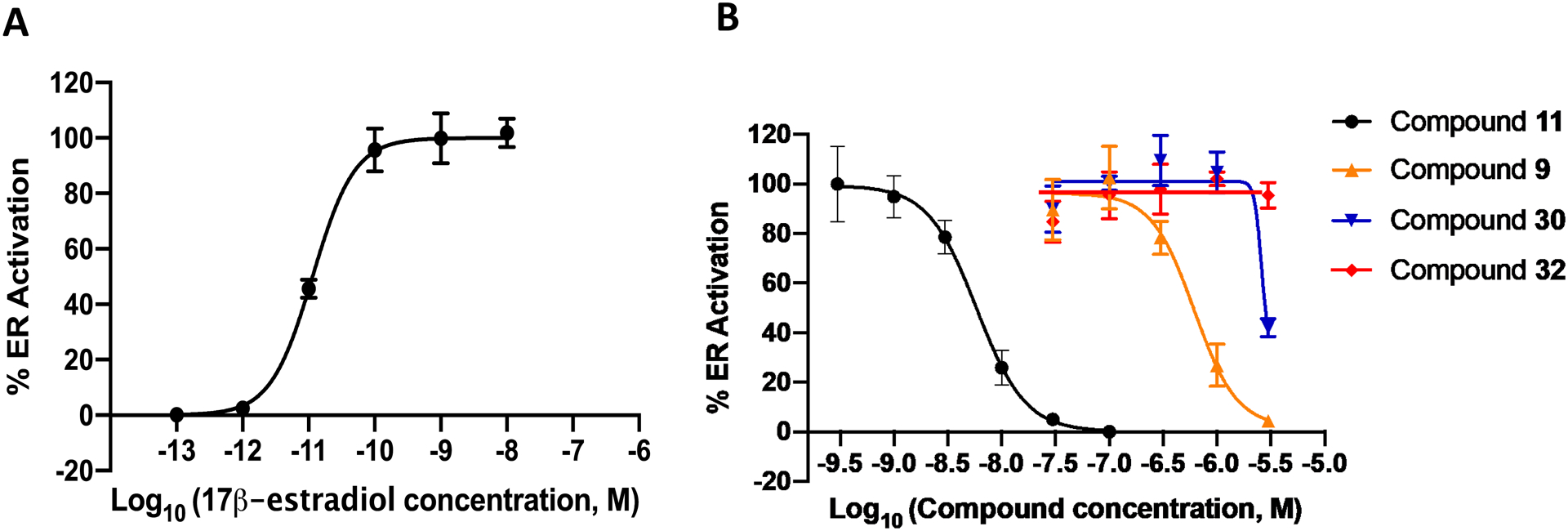

A key design feature was to abolish binding to ER and any ensuing ER-mediated side effects. To evaluate the ER activity of compound 30 and 32, we performed a cell-based assay using cells transfected with an estrogen response element (ERE) luciferase reporter. In the antagonist mode, compounds are assayed for their ability to antagonize binding of the potent endogenous ligand 17β-estradiol (E2). These MCF-7:WS8 human breast cancer cells endogenously express ERα. The ERE-luciferase response was normalized to E2 (1 nM) treatment at 100% and vehicle treatment as (0%). The SERM raloxifene (11) is a potent ER antagonist in this cell line as shown by the observed IC50 = 5.9 nM (Figure 6). Hit compound, 9, retains ER antagonist activity (IC50 = 0.6 μM); however, both compounds 30 and 32 retained no antagonist activity at ER, validating the design rationale of incorporation an amide linker to perturb binding between H3 and H11 in the ER ligand binding domain (T347, W383, and L525, Figure S4). No compounds demonstrated ER agonist activity (data not shown).

Figure 6. Compounds 30 and 32 showed attenuated ER antagonism.

(A) ER activation of the indigenous ligand 17β-estradiol. (B) Antagonism activity of the two novel compounds (30 and 32) were assessed by activation of ERE (estrogen response element) in MCF-7:ws8 cells (normalized to 1 nM E2 = 100%, 1% DMSO cells = 0%) using a luciferase assay after treatment for 18 h. The antagonist action of these compounds was assessed in the presence of 1 nM E2, and a dose dependent reduction in E2 luciferase activity not associated with cytotoxicity was not seen with increasing concentrations of 30 and 32. In contrast, compounds 9 and 14 (positive control) showed an increased potency and a dose dependent reduction in E2 luciferase activity increasing concentrations. All error bars represent S.D. from three independent experiments.

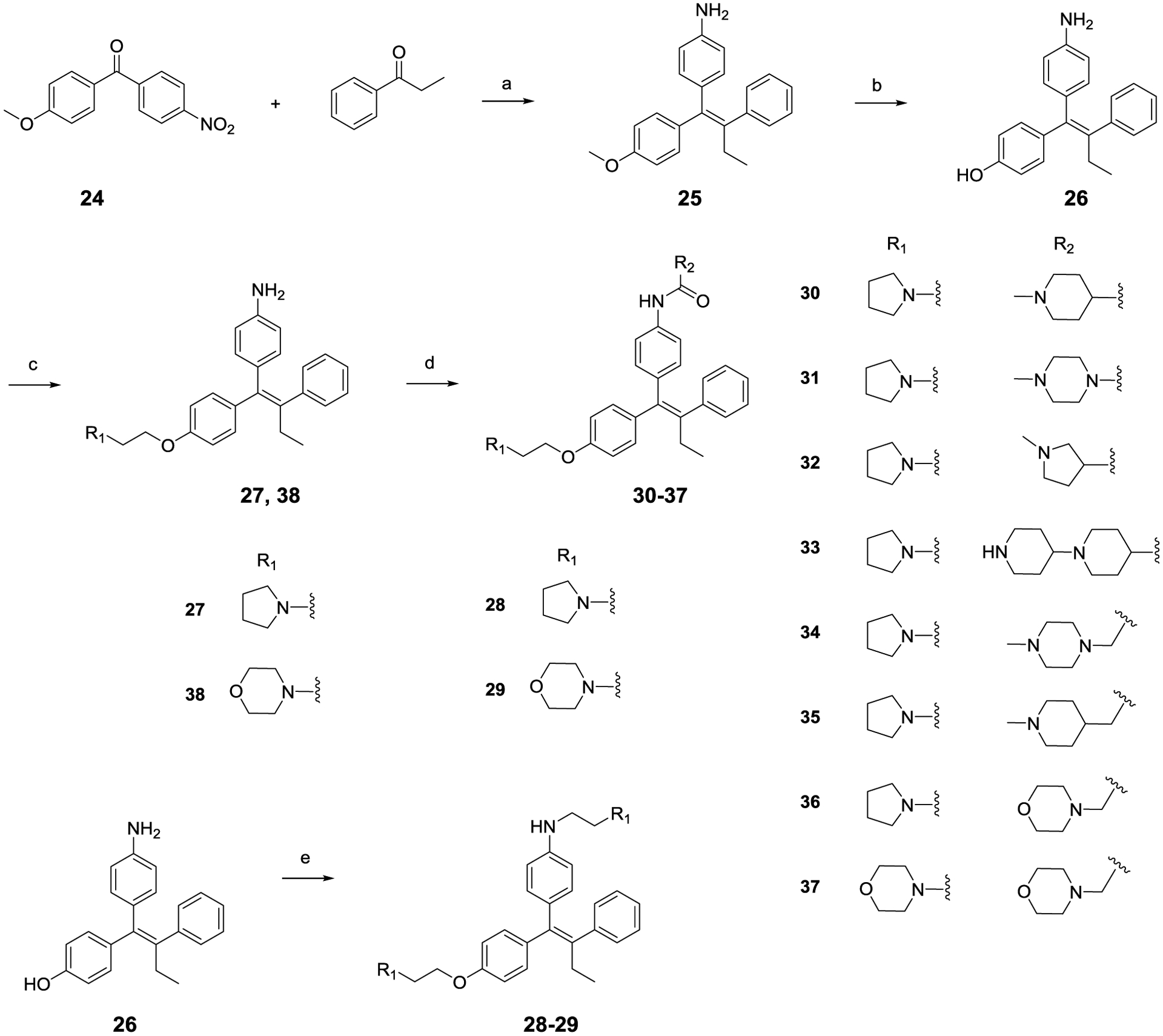

Synthesis of Compound 9 analogs.

The general synthetic method for compound 9 analogs is outlined in scheme 1. The triphenylethylene core is constructed via the McMurry coupling reaction using substituted benzophenones and propiophenone.51 E-isomer of 25 is isolated in acetone-hexane system as the major product (E/Z ratio: 6:1) with a 72% yield and confirmed by NOE NMR experiment. Nitro group was also reduced directly under the reducing environment with zinc powder.52 Demethylation of 25 was carefully examined using various reagent and solvent system, leading to the identification of BF3 · SMe2 as the best demethylating reagent and DCM/ACN (1:1) as the optimum solvent system. This condition provides the highest yield and minimal E/Z isomerization. Monoalkylated compounds 27 and 38 were prepared using a reported protocol that utilizes equivalent ratio of potassium carbonate and alkyl chloride in acetone-water system for 2 h under dark condition.53 Dialkylated substituents 28-29 was obtained under a similar reaction condition but with excessive alkyl chloride and long-time refluxing. Compound 30-37 were prepared using standard EDCI coupling. It is of note that compound 9 analogs undergo facile E/Z isomerization in solution, particularly in dichloromethane and chloroform.54, 55 Therefore, these two solvents were either abandoned or used with methanol or acetonitrile to reduce fast E/Z isomerization.

Scheme 1.

(a) Zn, TiCl4, THF, reflux, 3 h, 72%; (b) BF3.SMe2, DCM/ACN, RT, 2 h, 88%; (c) K2CO3, alkyl chloride, actone/H2O, 50 °C, 2 h, 64% – 70%, dark conditions; (d) Acid, EDCI, HOBt, DIPEA, DMF, RT, 4 h, 74% – 93%; (e) Alkyl chloride, acetone/ H2O, reflux, 5 h; 73% – 77%.

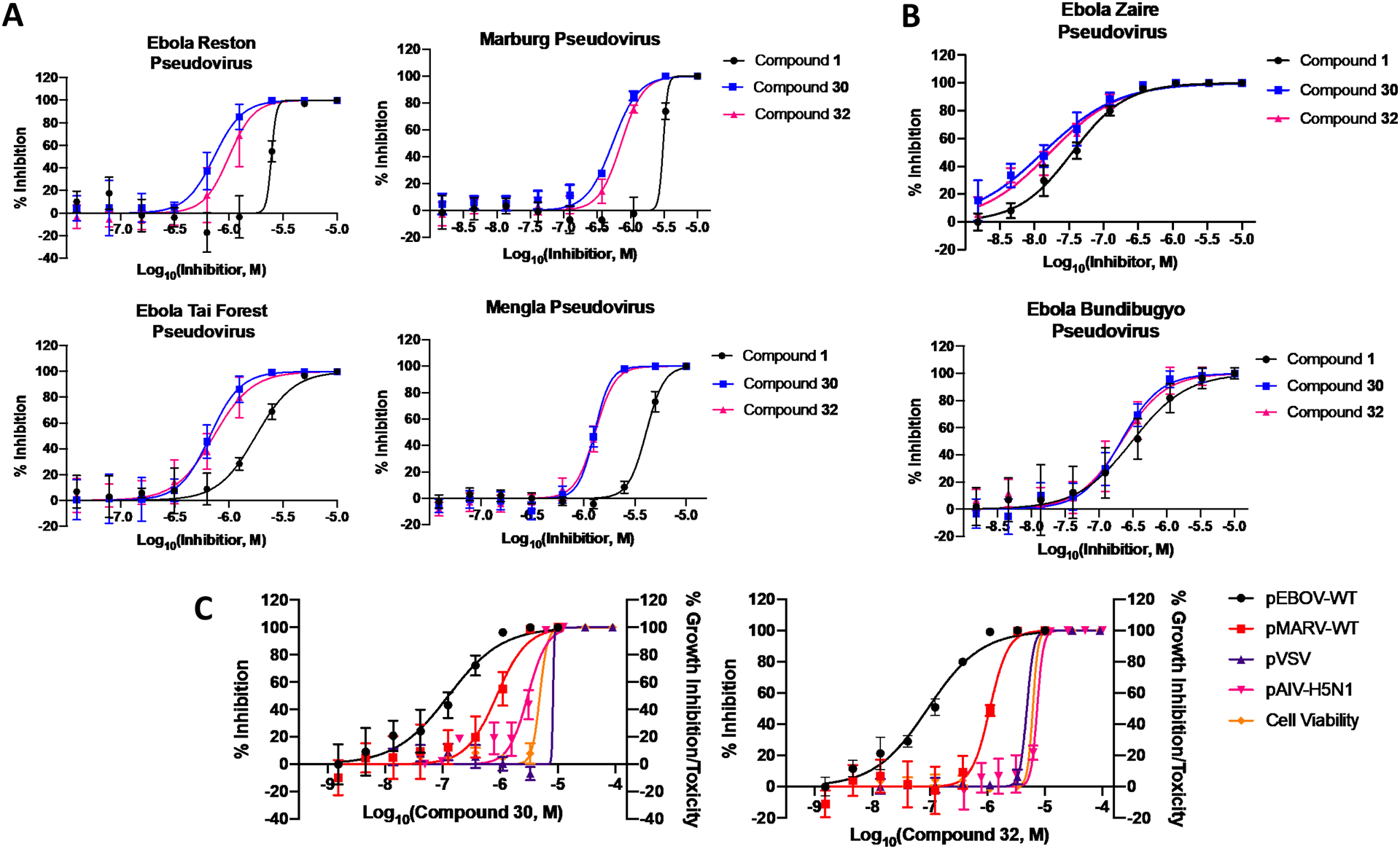

Compounds 30 and 32 as pan-filovirus inhibitors.

The potency of compounds 30 and 32 against both EBOV and MARV prompted us to examine the activity of these compounds against other filoviruses. Compounds 30 and 32 were screened against pseudotyped models of ebolavirus Reston (pRESTV), ebolavirus Tai Forest (pTFV), ebolavirus Bundibugyo (pBDBV), and the newly discovered Měnglà virus (pMLAV) compared to compound 1 (Figure 7). All three compounds showed appreciable inhibition of viral entry for all filovirus species tested. The improved potency of compounds 30 and 32 versus 1 is significant and striking, notably in pTFV, pRESTV, pMARV, and pMLAV. These data strongly support that activity of these compounds as pan-filovirus entry inhibitors and their potential to act as antiviral agents towards multiple species and genera within the filovirus family. 30 and 32 were counter-screened against a HIV pseudotyped model of H5N1 avian influenza virus (pAIV-H5N1) and vesicular stomatitis virus (pVSV). Neither compounds showed appreciable inhibition of pAIV-H5N1 or pVSV, proving these compounds have filovirus specific activity. The pan-filovirus specificity and activity, along with the strong inhibition profile against infectious EBOV and MARV, and the ablation of ER-associated side effects, highlight these two novel highly potent antiviral agents as potential development candidate for the treatment of filovirus infections.

Figure 7. Compounds 30 and 32 are filovirus specific pan-filovirus entry inhibitors.

(A) Both novel compounds showed improved potency compared to 1 with pseudotyped MARV, RESTV, TFV, and MLAV. (B) In contrast, all three compounds showed a considerable but identical potency with pseudotyped EBOV and BDBV. (C) Both compounds showed no appreciable inhibition of pseudotyped AIV-H5N1 or VSV, proving these compounds have filovirus specific activity. All error bars represent S.D. from two or three independent experiments.

Conclusion

This study presented here discovered a new filovirus entry inhibitor compound 9, via a screen of ER ligand focused library against pseudotyped MARV and EBOV. Based on the structure compound 9, rational drug design and subsequent chemical optimization led to the development of two potent and novel pan-filovirus inhibitors, 30 and 32. Reverse-engineering of ER binding affinity attenuates potential ER-related side effects of compound 30 and 32. Utilizing the mutagenesis studies, we confirmed the anti-EBOV mechanism of these two compounds were through direct binding to GP. Both compounds have favorable SI values when tested with infectious EBOV and MARV, were shown to be filovirus specific inhibitors and have broad-spectrum filovirus entry inhibition against all species tested. Furthermore, these compounds showed significant improvement of potency against pMARV, pRESTV, pTFV and pMLAV when compared to previously reported inhibitor 1. Overall, compounds 30 and 32 represent two of the most potent pan-filovirus entry inhibitors to date and justify further development as a potential treatment for filovirus infections.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Cell Culture

Human A549 lung epithelial cells (ATCC# CCL185) and 293T embryonic kidney cells (ATCC# CRL-1573) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 100 units of penicillin and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. MCF- 7:WS8 (gift from Dr. Gregory RJ Thatcher) is hormone-dependent human breast cancer cell clone maintained in a phenol-red-containing RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Cat. 51200038) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 1% (v/v) antibiotic-antimycotic 100X (Gibco, Cat. 15240062), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco, Cat. 25030081), 1%(v/v) non-essential amino acids 100X solution (Gibco, Cat. 11140050) and 6 ng/ml insulin (Millipore-sigma I0516) at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Pseudovirion Production

Pseudoviruses for the initial IC50 drug screening were created using the following plasmids: hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), isolated from highly pathogenic avian influenza virus, A/Goose/Qinghai/59/05 (H5N1) strain, Marburg virus Musoke glycoprotein, Ebola virus Zaire Mayinga glycoprotein, Měnglà virus glycoprotein, Reston virus glycoprotein, Tai Forest virus glycoprotein, Bundibugyo virus glycoprotein, and the HIV-1 pro-viral vector pNL4–3.Luc.R−E− which were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. All pseudovirions were produced by transient co-transfection of 293T cells using a polyethyleneimine (PEI)-based transfection protocol. Five hours after transfection, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 20 mL of fresh media was added to each 150 mm plate. Twenty-four hours post transfection, the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.45 μM pore size filter and stored at 4 °C prior to use.

Measuring IC50 and CC50 against Pseudovirus

Low-passage A549 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5,000 cell/well and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 hours prior to infection. In the presence of a range of drug concentrations, A549 cells were infected with pseudovirions containing a luciferase reporter gene. All drugs were dissolved in DMSO and the final treatment DMSO concentrations never exceeded 1%. Plates were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 48 h and viral infection was quantified by luminescence using the neolite reporter gene assay system (PerkinElmer). Virus with 1% DMSO was used as a negative control and data was normalized to the negative control. Drug cytotoxicity was assessed using the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) in the A549 cells treated the same way as for antiviral screen. IC50 and CC50 values were determined by fitting dose-response curves with four-parameter logistic regression in Graphpad.

Infectious Virus Assay Estrogen Receptor Targeting Compounds

Infectious Ebola virus (Kikwit variant) or Marburg virus (Angola variant) was used for testing the efficacy of compounds. All viral infections were done in a BSL-4 facility at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute and in the NEIDL, 4,000 HeLa cells per well were grown overnight in 384-well tissue culture plates; the volume of DMEM (Fisher scientific, Cat#MT10017CV) culture media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products, Cat#100106) was 25 μL. On the day of assay, test drugs were diluted to 1 mM concentration in complete media. A 25 μL volume of this mixture was added to the cells already containing 25 μL of media to achieve a concentration of 500 μM. All treatments were done in triplicate. A 25 μL volume of media was removed from the first wells and added to the next well. This type of serial dilution was performed 12 times, and the treated cells were then incubated at 37 °C in a humidified CO2 incubator for 1 hour. Final concentrations of 250, 125, 62.5, 31.25, 15.62, 7.81, 3.9, 1.9, 0.97, 0.48, 0.24 and 0.12 μM were achieved upon addition of 25 μL of infection mix containing EBOV or MARV virus. Bafilomycin, at a final concentration of 10 nM, was used as a positive control drug. Infections were designed to achieve a MOI of 0.05 to 0.15. Infected cells were incubated for 24 h. At 24 h post-infection, the cells were fixed by immersing the plates in formalin for 24 hours at 4 °C. Fixed plates were decontaminated and removed from the BSL-4 facility. Formalin from fixed plates was decanted and the plates were washed with PBS. EBOV (or MARV)-infected cells were stained for nuclei using the Hoechst stain at 1:50,000 dilution and virus-specific antibody (IBT Bioservices) followed by a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (Alexa488). The plates were imaged. Nuclei (blue) and infected cells (green) were counted using CellProfiler software (Broad Institute) Version 2.1.1. The total number of nuclei (blue) was used as a proxy for cell numbers and a loss of cell number was assumed to reflect cytotoxicity. Concentrations where total cell numbers were 20% less than the control were rejected from the analysis.

Estrogen Response Elements (ERE) Luciferase Assay in MCF-7 Cells.

MCF-7:WS8 cells were kept in a phenol-red-free medium (Gibco, Cat. 51200038) with stripped fetal bovine serum (Gemini Cat 100–119) for 72 h prior to treatment. Cells were plated at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates and were co-transfected with 10 μg of pERE-luciferase plasmid per plate, which contains three copies of the Xenopus laevis vitellogenin A2 ERE upstream of firefly luciferase, and 2 μg of pRL-TK plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI) containing a cDNA encoding Renilla luciferase. Transfection was performed for 6 h using the Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) in an Opti-MEM medium according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were treated with test compounds at various concentrations and 1 nM E2 (final treatment DMSO concentrations never exceeded 1%) after 6 h, and the luciferase activity was measured after 18 h of treatment using the dual luciferase assay system (Promega) with a Synergy H4 microplate reader (Bio Tek). ER activity and cc50 were determined by fitting dose-response curves with a four-parameter logistic regression in Graphpad. Drug cytotoxicity was assessed using the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) in the MCF-7:WS8 cells treated the same way as for the assay. Medium with 1% DMSO was used as a negative control and 1 nM β-estradiol was used as a positive control; data was normalized to both the positive and negative controls.

Chemical Reagents

Most compounds used in the estrogen receptor library screen were synthesized in-house and have been reported.32–35, 56, 57 Toremifene, tamoxifen, raloxifene, bazedoxifene, ospemifene, ridaifen-B, nafoxidine, RAD-1901, MPP, acolbifene, and compound 7 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Med Chem Express. All compounds were dissolved in DMSO at a final concentration of 10 mM and were stored at −20 °C until use.

General Chemical Synthesis Information

Unless otherwise specified, reactions were performed under an inert atmosphere of argon and monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and/or LCMS. All reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used as provided. Synthetic intermediates were purified using a CombiFlash chromatography system on a 230–400 mesh silica gel. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained using a Bruker DPX-400 or AVANCE-400 spectrometer at 400 and 100 MHz, respectively. NMR chemical shifts were described in δ (ppm) using residual solvent peaks as standard (chloroform-d, 7.26 ppm (1H), 77.16 ppm (13C); methanol-d4, 3.31 ppm (1H), 49.00 ppm (13C); DMSO-d6, 2.50 ppm (1H), 39.52 ppm (13C); acetone-d6, 2.05 ppm (1H), 29.84 ppm (13C)). Data were reported in a format as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, dd = doublet of doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, br = broad, m = multiplet, abq = ab quartet), number of protons, and coupling constants. High resolution mass spectral data were measured in-house using a Shimadzu IT-TOF LC/MS for all final compounds. All compounds submitted for biological testing were confirmed to be ≥ 95% pure by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Analytical HPLC was performed with an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm packing diameter) using a gradient of 5–95% methanol in water supplemented with 0.1% formic acid as the mobile phase (A = 0.1% formic acid in water; B = 0.1% formic acid in methanol at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Gradient: 0 min, 5% B; 1 min, 5% B; 20 min 95% B; 22 min, 95% B; 24 min, 5% B). The purity of the samples was assessed using a UV detector (Agilent G1314F, 1260 VWD) at 254 nm. Synthetic methods, spectral data, and MS for novel compounds are described in detail below.

(E)-4-(1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-phenylbut-1-en-1-yl)aniline (25).

Zinc powder (788 mg, 12 mmol) was suspended in dry tetrahydrofuran (THF) (80 mL) at 0 °C and TiCl4 (6.4 mL, 60 mmol) was added to the mixture. After completion, the reaction mixture was refluxed for 3 h. After cooling to RT, a dry THF solution of (4-methoxyphenyl)(4-nitrophenyl) methanone 24 (2.57 g, 10 mmol) and propiophenone (4.02 g, 30 mmol) was added and the mixture was refluxed in the dark. Upon completion monitored by TLC, the reaction was cooled to RT and the zinc dust was filtered off. Excessive THF was removed in vacuo, and the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexane-EtOAc, 1:1) to obtain 25 (2.38 g, yield 72%) as a light-yellow solid. The NMR spectrum showed an E:Z ratio of 18:1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 7.20 – 7.08 (m, 7H), 6.91 – 6.87 (m, 2H), 6.68 – 6.62 (m, 2H), 6.36 – 6.31 (m, 2H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 2.47 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 0.93 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 330.2.

(E)-4-(1-(4-aminophenyl)-2-phenylbut-1-en-1-yl)phenol (26).

To a solution of 25 (990 mg, 3 mmol) in DCM/acetonitrile (20 mL, 1:4) at RT was added dropwise boron trifluoride dimethyl sulfide complex (6.3 mL, 60 mmol). The mixture was then stirred for 2 h followed by quenching with water. The resulting solution was extracted with ethyl acetate and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Filtration and concentration in vacuo gave a residue, which was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexanes-acetone, 1:1) to give 26 (834 mg, yield 88%) a pale yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.35 (s, 1H), 7.21 – 7.13 (m, 2H), 7.08 (m, 3H), 6.99 – 6.92 (m, 2H), 6.77 – 6.70 (m, 2H), 6.48 – 6.40 (m, 2H), 6.22 – 6.15 (m, 2H), 4.84 (s, 2H), 2.37 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 0.82 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 316.1.

(E)-4-(2-phenyl-1-(4-(2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)but-1-en-1-yl)aniline (27).

A mixture of 26 (630 mg, 2 mmol), 1-(2-chloroethyl)pyrrolidine hydrochloride (340 mg, 2 mmol), potassium carbonate (276 mg, 2 mmol), and H2O (1.5 mL) in acetone (15 mL) was heated at 50 °C for 2 h. The reaction mixture was then cooled to RT, diluted with ethyl acetate, and washed with aqueous NaHCO3. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexanes-acetone, 1:1) to give 27 (527 mg, yield 64%) as a brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 7.24 – 7.16 (m, 6H), 7.10 (ddd, J = 8.7, 5.1, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 6.98 – 6.91 (m, 2H), 6.65 – 6.57 (m, 2H), 6.38 – 6.31 (m, 2H), 4.14 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.88 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.66 – 2.58 (m, 4H), 2.50 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.75 (t, J = 4.0 Hz, 4H), 0.93 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 413.3.

(E)-4-(2-phenyl-1-(4-(2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)but-1-en-1-yl)-N-(2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethyl)aniline (28).

To a solution of potassium carbonate (691 mg, 5 mmol) and 1-(2-chloroethyl)pyrrolidine hydrochloride (850 mg, 5 mmol) in water/acetone (10 mL, 1:10), compound 26 (315 mg, 1 mmol) was added. The mixture was refluxed for 5 h and then cooled to RT. Acetone was removed under vacuo, and the crude was purified by preparative HPLC system (water/acetonitrile with an adduct of 0.05% formic acid) to obtain 37 (392 mg, yield 77%) as a white solid. LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 510.3.

(E)-4-(1-(4-(2-morpholinoethoxy)phenyl)-2-phenylbut-1-en-1-yl)-N-(2-morpholinoethyl)aniline (29).

Compound 29 (mg, yield 73%) was obtained as a white solid following the procedure of compound 28. 1H NMR (400 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 7.21 – 7.12 (m, 6H), 7.12 – 7.06 (m, 1H), 6.96 – 6.91 (m, 2H), 6.64 – 6.59 (m, 2H), 6.30 – 6.25 (m, 2H), 4.14 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.61 (dq, J = 9.9, 4.6 Hz, 8H), 3.07 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 2.76 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 2.58 – 2.38 (m, 12H), 0.89 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 7.21 – 7.12 (m, 6H), 7.09 (tt, J = 5.5, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.96 – 6.90 (m, 2H), 6.60 – 6.54 (m, 2H), 6.35 – 6.27 (m, 2H), 4.43 (s, 1H), 4.15 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.66 – 3.60 (m, 4H), 2.77 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 2.55 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 2.46 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 0.89 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 542.3.

(E)-1-methyl-N-(4-(2-phenyl-1-(4-(2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)but-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)piperidine-4-carboxamide (30).

A mixture of 27 (41 mg, 0.1 mmol), 1-methylpiperidine-4-carboxylic acid (15.8 mg, 0.11 mmol), EDCI (38.3 mg, 0.2 mmol), HOBt (27 mg, 0.2 mmol), and DIPEA (38.8 mg, 0.3 mmol) in dimethylformamide (DMF) (1 mL) was stirred at RT for 4 h. Water/methanol (1 mL, 1:1) was added to the reaction and the crude was purified by preparative HPLC system (water/acetonitrile with adduct of 0.05% formic acid) to obtain 30 (44.0 mg, yield 82%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 7.21 – 7.09 (m, 9H), 6.97 – 6.93 (m, 2H), 6.82 – 6.77 (m, 2H), 4.17 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 2.98 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 2.96 – 2.90 (m, 2H), 2.74 (td, J = 5.5, 4.2, 1.9 Hz, 4H), 2.50 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.28 (s, 3H), 2.13 – 2.04 (m, 2H), 1.85 (ddt, J = 17.1, 9.5, 4.6 Hz, 9H), 0.93 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 175.84, 159.03, 143.75, 143.08, 140.54, 139.41, 137.59, 137.44, 132.22, 131.65, 130.85, 128.95, 127.19, 120.07, 115.25, 67.52, 56.06, 55.90, 55.55, 46.30, 43.94, 29.93, 29.48, 24.21, 13.84. LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 538.4.

(E)-4-methyl-N-(4-(2-phenyl-1-(4-(2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)but-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)piperazine-1-carboxamide (31).

Compound 31 (46.8 mg, yield 87%) was obtained as a white solid following the procedure of compound 30. 1H NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 7.21 – 7.17 (m, 2H), 7.16 – 7.09 (m, 5H), 7.04 – 6.99 (m, 4H), 6.78 – 6.74 (m, 2H), 4.39 – 4.33 (m, 2H), 3.67 – 3.63 (m, 2H), 3.61 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 4H), 3.48 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 4H), 2.81 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 4H), 2.57 (s, 3H), 2.47 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.12 (td, J = 7.2, 5.5, 3.6 Hz, 4H), 0.91 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 158.04, 157.42, 143.67, 143.11, 139.50, 139.24, 138.59, 138.42, 132.07, 131.81, 130.82, 128.94, 127.21, 120.84, 115.43, 64.43, 55.66, 55.21, 54.97, 44.92, 43.77, 29.93, 23.93, 13.82. LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 539.2.

(E)-1-methyl-N-(4-(2-phenyl-1-(4-(2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)but-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)pyrrolidine-3-carboxamide (32).

Compound 32 (40.7 mg, yield 78%) was obtained as a white solid following the procedure of compound 30. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 7.26 – 7.09 (m, 9H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 4.36 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.65 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.48 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H), 3.42 – 3.37 (m, 3H), 2.93 (s, 3H), 2.48 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 2.24 (dt, J = 13.3, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 2.15 – 2.10 (m, 4H), 0.92 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 172.34, 158.11, 143.57, 140.76, 139.08, 138.35, 137.35, 133.14, 132.24, 131.81, 130.82, 128.97, 127.30, 120.98, 120.02, 115.47, 114.63, 64.47, 58.77, 56.57, 55.65, 55.21, 44.53, 41.48, 29.97, 29.93, 23.93, 13.79. LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 524.3.

(E)-1’-methyl-N-(4-(2-phenyl-1-(4-(2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)but-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)-[1,4’-bipiperidine]-4-carboxamide (33).

Compound 33 (52.7 mg, yield 85%) was obtained as a white solid following the procedure of compound 30. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 7.22 – 7.13 (m, 6H), 7.12 – 7.08 (m, 3H), 7.05 – 7.01 (m, 2H), 6.81 – 6.75 (m, 2H), 4.36 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.66 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.48 (s, 3H), 3.43 – 3.38 (m, 2H), 3.28 (m, 3H), 2.91 (t, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 2.83 – 2.72 (m, 2H), 2.69 (s, 3H), 2.62 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 2H), 2.47 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 2.21 – 2.10 (m, 6H), 1.91 (dq, J = 29.2, 15.3, 13.0 Hz, 6H), 0.91 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 174.96, 158.07, 143.56, 143.47, 140.51, 139.11, 138.44, 137.52, 132.19, 131.83, 130.82, 128.97, 127.29, 120.11, 115.46, 64.40, 61.12, 55.68, 55.23, 54.51, 49.83, 44.03, 43.11, 29.92, 28.70, 26.68, 23.92, 13.80. LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 621.4.

(E)-2-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-N-(4-(2-phenyl-1-(4-(2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)but-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)acetamide (34).

Compound 34 (40.9 mg, 74%) was obtained as a white solid following the procedure of compound 30. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 7.15 (ddd, J = 32.0, 15.8, 7.7 Hz, 9H), 7.01 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 4.35 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 3.64 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.45 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 3.33 (s, 1H), 3.29 (p, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 3.21 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 5H), 2.83 – 2.79 (m, 3H), 2.78 (s, 3H), 2.46 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.16 – 2.07 (m, 4H), 0.90 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 169.96, 168.45, 158.10, 143.56, 140.88, 139.10, 138.34, 136.84, 132.22, 131.81, 130.82, 128.97, 127.29, 120.36, 115.47, 64.44, 61.67, 55.63, 55.16, 54.65, 51.37, 43.75, 29.93, 23.93, 13.80. LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 553.3.

(E)-2-(1-methylpiperidin-4-yl)-N-(4-(2-phenyl-1-(4-(2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)but-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)acetamide (35).

Compound 35 (51.2 mg, yield 93%) was obtained as a white solid following the procedure of compound 30. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 7.21 – 7.14 (m, 6H), 7.13 – 7.09 (m, 3H), 7.05 – 7.00 (m, 2H), 6.82 – 6.77 (m, 2H), 4.38 – 4.33 (m, 2H), 3.67 – 3.61 (m, 2H), 3.50 – 3.41 (m, 5H), 3.01 – 2.91 (m, 2H), 2.81 (s, 3H), 2.47 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.31 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.15 – 2.09 (m, 4H), 2.08 – 2.03 (m, 2H), 1.97 (d, J = 14.6 Hz, 2H), 1.54 (q, J = 13.0 Hz, 2H), 0.91 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 171.97, 158.12, 143.58, 143.50, 140.59, 139.11, 138.43, 137.41, 132.22, 131.83, 130.83, 128.99, 127.30, 120.07, 115.47, 64.50, 55.68, 55.25, 49.85, 43.74, 43.24, 31.94, 30.35, 29.94, 23.93, 13.79. LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 552.2.

(E)-2-morpholino-N-(4-(2-phenyl-1-(4-(2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)but-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)acetamide (36).

Compound 36 (49.1 mg, yield 91%) was obtained as a white solid following the procedure of compound 30. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 7.26 – 7.21 (m, 2H), 7.15 (m, 7H), 6.98 – 6.94 (m, 2H), 6.86 – 6.81 (m, 2H), 4.17 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.74 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 4H), 3.11 (s, 2H), 2.98 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 2.77 – 2.71 (m, 4H), 2.58 – 2.54 (m, 4H), 2.51 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.87 (h, J = 3.2 Hz, 4H), 0.94 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 170.49, 159.07, 143.73, 143.22, 140.98, 139.36, 137.37, 136.75, 132.31, 131.66, 130.86, 128.97, 127.23, 120.18, 115.25, 67.80, 67.58, 63.23, 56.07, 55.55, 54.73, 29.95, 24.21, 13.84. LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 540.3.

(E)-2-morpholino-N-(4-(1-(4-(2-morpholinoethoxy)phenyl)-2-phenylbut-1-en-1-yl)phenyl)acetamide (37).

Compound 37 (45.5 mg, yield 82%) was obtained as a white solid following the procedure of compound 30. 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 7.24 – 7.19 (m, 2H), 7.16 – 7.07 (m, 7H), 6.95 – 6.90 (m, 2H), 6.84 – 6.79 (m, 2H), 4.14 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.70 (q, J = 4.8 Hz, 8H), 3.08 (s, 2H), 2.81 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 2.60 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 4H), 2.54 – 2.44 (m, 6H), 0.91 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 170.40, 158.99, 143.69, 143.19, 140.91, 139.30, 137.36, 136.75, 132.30, 131.65, 130.83, 128.97, 127.22, 120.14, 115.28, 67.77, 67.53, 66.34, 63.22, 58.73, 55.08, 54.70, 29.96, 13.88. LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 556.2.

(E)-4-(1-(4-(2-morpholinoethoxy)phenyl)-2-phenylbut-1-en-1-yl)aniline (38).

Compound 38 (365 mg, yield 70%) was obtained as a brown solid following the procedure of compound 27. 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 7.21 – 7.12 (m, 6H), 7.09 (tt, J = 5.5, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.96 – 6.90 (m, 2H), 6.60 – 6.54 (m, 2H), 6.35 – 6.27 (m, 2H), 4.43 (s, 1H), 4.15 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.66 – 3.60 (m, 4H), 2.77 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 2.55 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 2.46 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 0.89 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). LCMS (m/z) [M + H]+ = 429.2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This study is supported in part by UICentre via NIH Grants UL1RR029879 and UL1TR002003 via UICentre (drug discovery @ UIC); and NIH grants R41 AI126971 and R42 AI126971 to L.R. The Reston virus glycoprotein, Tai Forest glycoprotein, Bundibugyo virus glycoprotein plasmids were generous gifts from Dr. Chris Broder at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences and Dr. Tzanko Stantchev from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The Měnglà virus glycoprotein plasmid was a generous gift from Dr. Zheng-Li Shi at the Wuhan Institute of Virology Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Abbreviations Used:

- EBOV

ebolavirus Zaire

- SUDV

ebolavirus Sudan

- BDBV

ebolavirus Bundibugyo

- TFV

ebolavirus Tai Forest

- MARV

Marburg virus

- RAVV

Ravn Virus

- RESTV

ebolavirus Reston

- LLOV

Lloviu virus

- MLAV

Měnglà Virus

- NP

nucleoprotein

- GP

glycoprotein

- L

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- GAGs

glycosaminoglycans

- NPC1

Niemann-Pick Type C1

- BSL

biosafety level

- SERD

selective estrogen receptor degraders

- pEBOV

pseudotyped ebolavirus Zaire

- pMARV

pseudotyped Marburg virus

- HR2

heptad-repeat 2

- ERE

estrogen response element

- E2

estradiol. (pRESTV, pseudotyped ebolavirus Reston

- pTFV

pseudotyped ebolavirus Tai Forest

- pBDBV

pseudotyped ebolavirus Bundibugyo

- pMLAV

pseudotyped Měnglà Virus

- pAIV-H5N1

pseudotyped H5N1 avian influenza virus

- pVSV

pseudotyped vesicular stomatitis virus

- PEI

polyethyleneimine

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Synthesis and characterization of all compounds and further experimental details.

Molecular formula strings (CSV).

PDB file of compound 9 docking to 5JQ7.

Reference

- 1.Kuhn JH; Becker S; Ebihara H; Geisbert TW; Johnson KM; Kawaoka Y; Lipkin WI; Negredo AI; Netesov SV; Nichol ST; Palacios G; Peters CJ; Tenorio A; Volchkov VE; Jahrling PB, Proposal for a Revised Taxonomy of the Family Filoviridae: Classification, Names of Taxa and Viruses, and Virus Abbreviations. Arch. Virol 2010, 155, 2083–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang X-L; Tan CW; Anderson DE; Jiang R-D; Li B; Zhang W; Zhu Y; Lim XF; Zhou P; Liu X-L; Guan W; Zhang L; Li S-Y; Zhang Y-Z; Wang L-F; Shi Z-L, Characterization of a Filovirus (Měnglà Virus) from Rousettus Bats in China. Nat. Microbiol 2019, 4, 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray M, Defense against Filoviruses Used as Biological Weapons. Antivir. Res 2003, 57, 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez A; Khan AS; Zaki SR; Nabel GJ; Ksiazek T; Peters CJ, Filoviridae: Marburg and Ebola Viruses In Fields Virology, Knipe DM; Howley PM, Eds. Lippincourt, Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia PA, 2001; pp 1279–1304. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters CJ; Khan AS, Filovirus Diseases. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol 1999, 235, 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Organization WH, Ebola Situation Report—16 March 2016.. 2016.

- 7.Cohen J, Ebola Outbreak Continues Despite Powerful Vaccine. Science 2019, 364, 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muhlberger E; Weik M; Volchkov VE; Klenk HD; Becker S, Comparison of the Transcription and Replication Strategies of Marburg Virus and Ebola Virus by Using Artificial Replication Systems. J. Virol 1999, 73, 2333–2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colman PM; Lawrence MC, The Structural Biology of Type I Viral Membrane Fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2003, 4, 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JE; Saphire EO, Ebolavirus Glycoprotein Structure and Mechanism of Entry. Future Virol. 2009, 4, 621–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manicassamy B; Wang J; Jiang H; Rong L, Comprehensive Analysis of Ebola Virus Gp1 in Viral Entry. J. Virol 2005, 79, 4793–4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Hearn A; Wang M; Cheng H; Lear-Rooney CM; Koning K; Rumschlag-Booms E; Varhegyi E; Olinger G; Rong L, Role of Ext1 and Glycosaminoglycans in the Early Stage of Filovirus Entry. J. Virol 2015, 89, 5441–5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salvador B; Sexton NR; Carrion R Jr.; Nunneley J; Patterson JL; Steffen I; Lu K; Muench MO; Lembo D; Simmons G, Filoviruses Utilize Glycosaminoglycans for Their Attachment to Target Cells. J. Virol 2013, 87, 3295–3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnittler HJ; Feldmann H, Marburg and Ebola Hemorrhagic Fevers: Does the Primary Course of Infection Depend on the Accessibility of Organ-Specific Macrophages? Clin. Infect. Dis 1998, 27, 404–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cote M; Misasi J; Ren T; Bruchez A; Lee K; Filone CM; Hensley L; Li Q; Ory D; Chandran K; Cunningham J, Small Molecule Inhibitors Reveal Niemann-Pick C1 Is Essential for Ebola Virus Infection. Nature 2011, 477, 344–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller EH; Obernosterer G; Raaben M; Herbert AS; Deffieu MS; Krishnan A; Ndungo E; Sandesara RG; Carette JE; Kuehne AI; Ruthel G; Pfeffer SR; Dye JM; Whelan SP; Brummelkamp TR; Chandran K, Ebola Virus Entry Requires the Host-Programmed Recognition of an Intracellular Receptor. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 1947–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carette JE; Raaben M; Wong AC; Herbert AS; Obernosterer G; Mulherkar N; Kuehne AI; Kranzusch PJ; Griffin AM; Ruthel G; Dal Cin P; Dye JM; Whelan SP; Chandran K; Brummelkamp TR, Ebola Virus Entry Requires the Cholesterol Transporter Niemann-Pick C1. Nature 2011, 477, 340–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong X; Qian H; Zhou X; Wu J; Wan T; Cao P; Huang W; Zhao X; Wang X; Wang P; Shi Y; Gao GF; Zhou Q; Yan N, Structural Insights into the Niemann-Pick C1 (Npc1)-Mediated Cholesterol Transfer and Ebola Infection. Cell 2016, 165, 1467–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H; Shi Y; Song J; Qi J; Lu G; Yan J; Gao GF, Ebola Viral Glycoprotein Bound to Its Endosomal Receptor Niemann-Pick C1. Cell 2016, 164, 258–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu F; Liang Q; Abi-Mosleh L; Das A; De Brabander JK; Goldstein JL; Brown MS, Identification of Npc1 as the Target of U18666a, an Inhibitor of Lysosomal Cholesterol Export and Ebola Infection. Elife 2015, 4, DOI: 10.7554/eLife.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren TK; Jordan R; Lo MK; Ray AS; Mackman RL; Soloveva V; Siegel D; Perron M; Bannister R; Hui HC; Larson N; Strickley R; Wells J; Stuthman KS; Van Tongeren SA; Garza NL; Donnelly G; Shurtleff AC; Retterer CJ; Gharaibeh D; Zamani R; Kenny T; Eaton BP; Grimes E; Welch LS; Gomba L; Wilhelmsen CL; Nichols DK; Nuss JE; Nagle ER; Kugelman JR; Palacios G; Doerffler E; Neville S; Carra E; Clarke MO; Zhang L; Lew W; Ross B; Wang Q; Chun K; Wolfe L; Babusis D; Park Y; Stray KM; Trancheva I; Feng JY; Barauskas O; Xu Y; Wong P; Braun MR; Flint M; McMullan LK; Chen SS; Fearns R; Swaminathan S; Mayers DL; Spiropoulou CF; Lee WA; Nichol ST; Cihlar T; Bavari S, Therapeutic Efficacy of the Small Molecule Gs-5734 against Ebola Virus in Rhesus Monkeys. Nature 2016, 531, 381–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng H; Schafer A; Soloveva V; Gharaibeh D; Kenny T; Retterer C; Zamani R; Bavari S; Peet NP; Rong L, Identification of a Coumarin-Based Antihistamine-Like Small Molecule as an Anti-Filoviral Entry Inhibitor. Antivir. Res 2017, 145, 24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng H; Lear-Rooney CM; Johansen L; Varhegyi E; Chen ZW; Olinger GG; Rong L, Inhibition of Ebola and Marburg Virus Entry by G Protein-Coupled Receptor Antagonists. J. Virol 2015, 89, 9932–9938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schafer A; Cheng H; Xiong R; Soloveva V; Retterer C; Mo F; Bavari S; Thatcher G; Rong L, Repurposing Potential of 1st Generation H1-Specific Antihistamines as Anti-Filovirus Therapeutics. Antivir. Res 2018, 157, 47–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu A; Mills DM; Mitchell D; Ndungo E; Williams JD; Herbert AS; Dye JM; Moir DT; Chandran K; Patterson JL; Rong L; Bowlin TL, Novel Small Molecule Entry Inhibitors of Ebola Virus. J. Infect. Dis 2015, 212 Suppl 2, S425–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yermolina MV; Wang J; Caffrey M; Rong LL; Wardrop DJ, Discovery, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of a Novel Group of Selective Inhibitors of Filoviral Entry. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 765–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren J; Zhao Y; Fry EE; Stuart DI, Target Identification and Mode of Action of Four Chemically Divergent Drugs against Ebolavirus Infection. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 724–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Y; Ren J; Fry EE; Xiao J; Townsend AR; Stuart DI, Structures of Ebola Virus Glycoprotein Complexes with Tricyclic Antidepressant and Antipsychotic Drugs. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 4938–4945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansen LM; Brannan JM; Delos SE; Shoemaker CJ; Stossel A; Lear C; Hoffstrom BG; DeWald LE; Schornberg KL; Scully C; Lehár J; Hensley LE; White JM; Olinger GG, Fda-Approved Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators Inhibit Ebola Virus Infection. Sci. Transl. Med 2013, 5, 190ra79–190ra79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Y; Ren J; Harlos K; Jones DM; Zeltina A; Bowden TA; Padilla-Parra S; Fry EE; Stuart DI, Toremifene Interacts with and Destabilizes the Ebola Virus Glycoprotein. Nature 2016, 535, 169–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katzenellenbogen JA, The 2010 Philip S. Portoghese Medicinal Chemistry Lectureship: Addressing the “Core Issue” in the Design of Estrogen Receptor Ligands. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 5271–5282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiong R; Patel HK; Gutgesell LM; Zhao J; Delgado-Rivera L; Pham TND; Zhao H; Carlson K; Martin T; Katzenellenbogen JA; Moore TW; Tonetti DA; Thatcher GRJ, Selective Human Estrogen Receptor Partial Agonists (Sherpas) for Tamoxifen-Resistant Breast Cancer. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 219–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiong R; Zhao J; Gutgesell LM; Wang Y; Lee S; Karumudi B; Zhao H; Lu Y; Tonetti DA; Thatcher GR, Novel Selective Estrogen Receptor Downregulators (Serds) Developed against Treatment-Resistant Breast Cancer. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 1325–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu Y; Gutgesell LM; Xiong R; Zhao J; Li Y; Rosales CI; Hollas M; Shen Z; Gordon-Blake J; Dye K; Wang Y; Lee S; Chen H; He D; Dubrovyskyii O; Zhao H; Huang F; Lasek AW; Tonetti DA; Thatcher GRJ, Design and Synthesis of Basic Selective Estrogen Receptor Degraders for Endocrine Therapy Resistant Breast Cancer. J. Med. Chem 2019, 62, 11301–11323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin Z; Kastrati I; Chandrasena RE; Liu H; Yao P; Petukhov PA; Bolton JL; Thatcher GR, Benzothiophene Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators with Modulated Oxidative Activity and Receptor Affinity. J. Med. Chem 2007, 50, 2682–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hunter E; Swanstrom R, Retrovirus Envelope Glycoproteins. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol 1990, 157, 187–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J; Cheng H; Ratia K; Varhegyi E; Hendrickson WG; Li J; Rong L, A Comparative High-Throughput Screening Protocol to Identify Entry Inhibitors of Enveloped Viruses. J. Biomol. Screen 2014, 19, 100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hashiguchi T; Fusco ML; Bornholdt ZA; Lee JE; Flyak AI; Matsuoka R; Kohda D; Yanagi Y; Hammel M; Crowe JE Jr.; Saphire EO, Structural Basis for Marburg Virus Neutralization by a Cross-Reactive Human Antibody. Cell 2015, 160, 904–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou HB; Carlson KE; Stossi F; Katzenellenbogen BS; Katzenellenbogen JA, Analogs of Methyl-Piperidinopyrazole (Mpp): Antiestrogens with Estrogen Receptor Alpha Selective Activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2009, 19, 108–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang H; Tong W; Shi LM; Blair R; Perkins R; Branham W; Hass BS; Xie Q; Dial SL; Moland CL; Sheehan DM, Structure-Activity Relationships for a Large Diverse Set of Natural, Synthetic, and Environmental Estrogens. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2001, 14, 280–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schafer A, X. R., Cooper L, Cheng H, Lee, Li Y, Thatcher G, Saphire EO, Rong L, Unpublished Results.

- 42.Gauthier S; Cloutier J; Dory YL; Favre A; Mailhot J; Ouellet C; Schwerdtfeger A; Merand Y; Martel C; Simard J; Labrie F, Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationships of Analogs of Em-652 (Acolbifene), a Pure Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator. Study of Nitrogen Substitution. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem 2005, 20, 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shiina I; Sano Y; Nakata K; Kikuchi T; Sasaki A; Ikekita M; Nagahara Y; Hasome Y; Yamori T; Yamazaki K, Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of the Novel Pseudo-Symmetrical Tamoxifen Derivatives as Anti-Tumor Agents. Biochem. Pharmacol 2008, 75, 1014–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Komm BS; Kharode YP; Bodine PV; Harris HA; Miller CP; Lyttle CR, Bazedoxifene Acetate: A Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator with Improved Selectivity. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 3999–4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun J; Huang YR; Harrington WR; Sheng S; Katzenellenbogen JA; Katzenellenbogen BS, Antagonists Selective for Estrogen Receptor Alpha. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 941–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beniac DR; Melito PL; Devarennes SL; Hiebert SL; Rabb MJ; Lamboo LL; Jones SM; Booth TF, The Organisation of Ebola Virus Reveals a Capacity for Extensive, Modular Polyploidy. PLoS One 2012, 7, e29608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas JH; Neff NF; Botstein D, Isolation and Characterization of Mutations in the Beta-Tubulin Gene of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Genetics 1985, 111, 715–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Si L; Meng K; Tian Z; Sun J; Li H; Zhang Z; Soloveva V; Li H; Fu G; Xia Q; Xiao S; Zhang L; Zhou D, Triterpenoids Manipulate a Broad Range of Virus-Host Fusion Via Wrapping the Hr2 Domain Prevalent in Viral Envelopes. Sci. Adv 2018, 4, eaau8408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ren J; Zhao Y; Fry EE; Stuart DI, Target Identification and Mode of Action of Four Chemically Divergent Drugs against Ebolavirus Infection. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 724–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christodoulou MS; Fokialakis N; Passarella D; Garcia-Argaez AN; Gia OM; Pongratz I; Dalla Via L; Haroutounian SA, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Tamoxifen Analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2013, 21, 4120–4131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu DD; Forman BM, Simple and Efficient Production of (Z)-4-Hydroxytamoxifen, a Potent Estrogen Receptor Modulator. J Org Chem 2003, 68, 9489–9491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cazares-Marinero Jde J; Top S; Vessieres A; Jaouen G, Synthesis and Antiproliferative Activity of Hydroxyferrocifen Hybrids against Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 817–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rey J; Hu HP; Snyder JP; Barrett AGM, Synthesis on Novel Tamoxifen Derivatives. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 9211–9217. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lv W; Liu J; Lu D; Flockhart DA; Cushman M, Synthesis of Mixed (E,Z)-, (E)-, and (Z)-Norendoxifen with Dual Aromatase Inhibitory and Estrogen Receptor Modulatory Activities. J. Med. Chem 2013, 56, 4611–4618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lv W; Liu J; Skaar TC; O’Neill E; Yu G; Flockhart DA; Cushman M, Synthesis of Triphenylethylene Bisphenols as Aromatase Inhibitors That Also Modulate Estrogen Receptors. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 157–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Overk CR; Peng KW; Asghodom RT; Kastrati I; Lantvit DD; Qin Z; Frasor J; Bolton JL; Thatcher GR, Structure-Activity Relationships for a Family of Benzothiophene Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators Including Raloxifene and Arzoxifene. ChemMedChem 2007, 2, 1520–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peng KW; Wang H; Qin Z; Wijewickrama GT; Lu M; Wang Z; Bolton JL; Thatcher GR, Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator Delivery of Quinone Warheads to DNA Triggering Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cells. ACS Chem. Biol 2009, 4, 1039–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.