Abstract

Purpose

The choice of surgical treatment for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow (UNE) remains controversial. A cost-utility analysis was performed for 4 surgical UNE treatment options. We hypothesized that simple decompression would emerge as the most cost-effective strategy.

Methods

A cost-utility analysis was performed from the societal perspective. A decision analytic model was designed comparing 4 strategies: (1) simple decompression followed by a salvage surgery (anterior submuscular transposition) for a poor outcome, (2) anterior subcutaneous transposition followed by a salvage surgery for a poor outcome, (3) medial epicondylectomy followed by a salvage surgery for a poor outcome, and (4) anterior submuscular transposition. A poor outcome when anterior submuscular transposition was the initial surgery was considered an end point in the model. Preference values for temporary health states for UNE, the surgical procedures, and the complications were obtained through a time trade-off survey administered to family members and friends who accompanied patients to physician visits. Probabilities of clinical outcomes were derived from a Cochrane Collaboration meta-analysis and a systematic MEDLINE and EMBASE search of the literature. Medical care costs (in 2009 U.S. dollars) were derived from Medicare reimbursement rates. The model estimated quality-adjusted life-years and costs for a 3-year time horizon. A 3% annual discount rate was applied to costs and quality-adjusted life-years. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were calculated, and sensitivity analyses performed.

Results

Simple decompression as an initial procedure was the most cost-effective treatment strategy. A multi-way sensitivity analysis varying the preference values for the surgeries and a model structure sensitivity analysis varying the model assumptions did not change the conclusion. Under all evaluated scenarios, simple decompression yielded incremental cost-effectiveness ratios less than US$2,027 per quality-adjusted life-year.

Conclusions

Simple decompression as an initial treatment option is cost-effective for UNE according to commonly used cost-effectiveness thresholds.

Keywords: Anterior transposition, cost–utility analysis, medial epicondylectomy, simple decompression, ulnar neuropathy at the elbow

ULNAR NEUROPATHY AT the elbow (UNE) is the second most common peripheral compressive neuropathy in the upper extremity after carpal tunnel syndrome.1 It has an estimated prevalence of 1% in the United States.2 The clinical progression of ulnar neuropathy can lead to substantial morbidity and affect quality of life. Unsuccessful conservative management is an indication for surgery. Many surgical procedures have been advocated for decompression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. These include simple decompression, medial epicondylectomy, and anterior transposition procedures. However, the most appropriate surgical option for UNE remains controversial.1,3 A Cochrane Collaboration systematic review of the literature reported no significant difference in effectiveness between simple decompression and anterior transposition for treatment of idiopathic UNE. Yet, the authors concluded that the literature was of poor quality and limited.4 Only 4 randomized controlled trials were identified and considered moderate in quality, but the studies were insufficiently powered and used different outcome measures.4,5

In the absence of high-quality randomized controlled trials, a decision analysis and economic evaluation is a valuable tool for comparing treatment options under conditions of uncertainty and can incorporate patient preferences.6,7,8 Because UNE can be a debilitating, chronic condition that can substantially affect quality of life, patients’ preferences and the costs of the treatments represent important factors to consider, given the lack of evidence favoring any particular treatment.

The aim of this cost-utility analysis was to identify the relative value of available treatment strategies for UNE based on cost, effectiveness, and quality of life measures. We hypothesized that simple decompression would emerge as the dominant and preferred surgery compared to the considered alternatives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An economic evaluation was performed using decision analytic modeling. Following the recommendations of the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine for a reference case analysis, the societal perspective was adopted. We used a 3-year time horizon (Appendix A; available on the Journal’s Web site at www.jhandsurg.org). To obtain preferences or quality of life measures, a web-based time trade-off survey was designed and administered to elicit utility values of health states.

Decision tree

A decision tree was designed using TreeAge software (TreeAge Pro Suite, Version 2009; TreeAge Software, Inc., Williamstown, MA). We assumed that all patients entering the model had an electrodiagnostically confirmed diagnosis of UNE, all patients had failed a trial of conservative treatment, and patients had no contraindications or preferences against having surgery or anesthesia. Our model tracked a cohort of 50-year-old patients who received 1 of 4 surgical treatments: simple decompression, anterior subcutaneous transposition, anterior submuscular transposition, or medial epicondylectomy (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1:

Schematic of decision tree for reference case analysis.

*After salvage surgery, possible complications following a poor outcome include no complication, superficial wound infection, scar tenderness beyond 4 months, and continued paresthesias with worsening UNE (ie, claw).

†After simple decompression, anterior subcutaneous transposition, and anterior submuscular transposition, possible complications that might have caused or followed a poor outcome include no complication, scar tenderness beyond 4 months, superficial wound infection, persistent paresthesias in the ring and small fingers, and neuromas of the medial brachial or antebrachial cutaneous nerves.

‡After medial epicondylectomy, possible complications that might have caused or followed a poor outcome include no complication, scar tenderness beyond 4 months, superficial wound infection, persistent paresthesias in the ring and small fingers, neuromas of the medial brachial or antebrachial cutaneous nerves, flexor-pronator weakness, and valgus instability.

§An additional branch for revision surgery following a neuroma complication was also modeled in the tree.

††After simple decompression, anterior subcutaneous transposition, anterior submuscular transposition, and salvage surgery, possible complications following a good outcome include no complication, scar tenderness beyond 4 months, and superficial wound infection.

‡‡Possible complications following a good outcome include no complication, scar tenderness beyond 4 months, superficial wound infection, flexor-pronator weakness, and valgus instability.

After each surgery, the possibility of a good or poor outcome was followed by the chance of a complication. The model assumed that patients who failed a simple decompression, anterior subcutaneous transposition, or medial epicondylectomy surgery subsequently had a salvage procedure, anterior submuscular transposition (Fig. 1).9–11 In the reference case, failure of an initial anterior submuscular transposition procedure for UNE treatment was considered an end point of the model. Among the possible complications, if the patient exhibited symptoms of a medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve injury (ie, neuroma) following an initial surgery, a reexploration with neuroma excision procedure was modeled. We assumed that the outcome of anterior submuscular transposition as a salvage procedure was not affected by the type of initial surgery, and after 2 surgical procedures, no further procedures were performed. For the model, we assumed that a patient experienced only one complication from a procedure and that each complication was addressed and had a definitive outcome.

Health utilities for UNE health states: survey development and design

Preference-based approaches are commonly used to quantify and measure quality of life associated with a particular health state. A common method of valuing preferences for a health state is to obtain a utility value. The utility value for a particular health state demonstrates how an individual feels about a health state as it relates to perfect health. Utilities are scaled from 1.0 (perfect health) to 0.0 (a health state deemed equivalent to death).12 A lower utility value indicates a less preferred health state (eg, cancer diagnosis). By contrast, a higher utility value indicates a preferred health state (eg, bruise).

Preferences for health state descriptions were elicited using a time trade-off (TTO) survey. Time trade-off questions require respondents to indicate the amount of time they are willing to lose from their own life to avoid experiencing a described health state. The TTO amounts are preference-based measures and can be transformed into utilities.12 A web-based TTO survey was administered through www.zoomerang.com. The temporary health state descriptions included UNE, surgeries, and potential complications. Five animations were incorporated into the survey, enabling the respondents to visualize and understand the anatomy and procedure. To reduce survey burden, a split-sample approach was used, and 15 scenarios were split into 4 surveys. Each survey presented 2 of the 4 surgery scenarios and animations. The animations were strategically placed as visual breaks to further reduce survey burden. To minimize anchoring bias, a form of cognitive bias resulting from a respondent focusing on a reference point based on the first scenario, scenario sequences and combinations were varied, and respondents were randomized to a survey (Appendix B; available on the Journal’s Web site at www.jhandsurg.org).13

The TTO surveys were pilot tested 3 times across a group of public health students, surgical research fellows and residents, and lay people from the community. The survey was revised after each pilot test. The survey also included an introduction, which informed respondents that there were no right or wrong answers and also provided an example to improve comprehension.

For each scenario, a description of the symptoms and physical activities was presented, followed by a multiple choice question (Fig. 2A). Respondents were asked to choose between a scenario related to living with the described scenario for a specified time period versus trading off a specified period of time and living the remaining period in perfect health. A final open-ended question was presented inquiring about the maximum or minimum amount of time that a respondent was willing to trade off (Fig. 2B).13

FIGURE 2:

A, B Sample time trade-off question.

Perspective and study subjects

Friends and family accompanying patients to physician visits were recruited from a neurosurgery and plastic surgery clinic waiting room from Feb 2011 to April 2011. Exclusion criteria included non-English-speaking, 18 years or younger, and active medical hand condition diagnoses.

Costs

Direct medical costs were estimated using the Medicare resource-based relative-value scale14 for 2009. Total Medicare reimbursements for surgical treatments include professional fees (surgeon, anesthesia, occupational therapy) and facility fees. Wholesale costs for generic cephalexin for treating a superficial wound infection15 and splints and elbow pads for anterior submuscular transposition were included. Opportunity costs related to time spent receiving care (eg, surgery, occupational therapy visits) were valued as indirect costs. We estimated that 2 work-days and 0.25 work-days off were needed to have surgery and an occupational therapy visit, respectively. These estimates were related to the time spent receiving care only, not the total amount of time taken off for the recovery period. Opportunity costs were calculated by obtaining the average hourly wage rate according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics16 for 2009 (Table 1). Other indirect costs, such as productivity loss due to injury and sick leave, were not accounted for in costs to avoid double counting.17 Respondents were instructed to consider these losses in their responses on the TTO surveys. Thus, these indirect costs were already reflected in the utility values for each health state. All costs were discounted to the present value using a 3% discount rate (see Appendix A; available on the Journal’s Web site at www.jhandsurg.org).17

TABLE 1.

Cost Estimates for Alternative Surgical Procedures (Rounded to Nearest US Dollar Value)

| Direct Costs (US$) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | Professional Fees | Facility Fees ASC§ | Indirect Costs (US$) | CPT Codes* | |||||

| Surgeon† | Anesthesia‡ | OT | Time¶ | Opportunity Cost# | Surgery | Anesthesia | OT | ||

| Simple decompression | $517 | $220 | NA | $669 | 2 work days | $276 | 64718 | 01710 | NA |

| Anterior subcutaneous transposition | $517 | $220 | NA | $669 | 2 work days | $276 | 64718 | 01710 | NA |

| Anterior submuscular transposition | $517 | $220 | $251** | $669 | 3 work days | $414 | 64718 | 01710 | 97003, 97760, 97110 |

| Medial epicondylectomy | $1,093 | $258 | $167†† | $1,061 | 2.25 work days | $281 | 64718, 24147 | 01710, 01740 | 97003, 97760, 97110 |

| Neuroma excision | $617 | $220 | NA | $669 | 2 work days | $276 | 64774, 64787 | 01710 | NA |

OT, occupational therapy; NA, not applicable; ASC, ambulatory surgical center.

2009 Current Procedural Terminology codes for procedures.

Medicare surgeon fee schedule (2009) based on CPT code. The Medicare national professional fee conversion factor for 2009 is US$36.0666.

Medicare anesthesia fee schedule (2009) based on CPT code for anesthesia from the American Society of Anesthesiologists Relative Value Guide. The national average anesthesia time reported for surgery CPT code 64718 is 112.8 minutes (n = 150). The national average anesthesia time reported for surgery CPT code 24127 is 125 minutes (n = 10). These national time averages are reported in the RBRVS Data Manager 2009 (CD-ROM) by the American Medical Association. The Medicare national anesthesia conversion factor for 2009 is US$20.9150. CPT 01710, anesthesia for procedures on nerves, muscles, tendons, fascia, and bursae of upper arm and elbow, not otherwise specified; CPT 01740, anesthesia for open or surgical arthroscopic procedures of the elbow, not otherwise specified.

Medical ambulatory surgery center fee schedule (2009) based on CPT code.

Time taken off from work to receive care is incorporated in the indirect costs. This time period does not reflect sick leave, which is not included in indirect costs. These values are obtained from expert opinion.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. http://www.bls.gov.

Four occupational therapy visits (includes initial evaluation and orthotic fitting and training).

One occupational therapy visit (includes initial evaluation, orthotic fitting and training, and therapeutic exercise and training).

Probabilities

Four randomized, controlled trials evaluating simple decompression, anterior submuscular and subcutaneous transpositions, and medial epicondylectomy as an initial surgery were identified through a recently published Cochrane Collaboration systematic review of the UNE literature and a meta-analysis.4,18–21 A systematic review of MEDLINE and EMBASE databases up to August 2010 was performed, and 5 studies examining revision UNE surgery with anterior submuscular transposition were identified.22–26 An outcome reported as excellent or good by the authors was considered a good outcome. A fair or poor outcome was considered a poor outcome. All event probabilities were calculated as a weighted probability value, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using a normal approximation for a binomial distribution (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Probabilities of Outcomes

| Scenario | Probability for Base Case Analysis (95% CI)* | Reference Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Simple decompression | ||

| Poor outcome† | 0.31 (0.20–0.41) | 18–20 |

| Anterior subcutaneous transposition | ||

| Poor outcome† | 0.27 (0.17–0.37) | 18 |

| Anterior submuscular transposition | ||

| Poor outcome† | 0.29 (0.19–0.40) | 19–21 |

| Medial epicondylectomy | ||

| Poor outcome †,‡ | 0.20 (0.11–0.29) | 21 |

| Salvage procedure (anterior submuscular transposition) | ||

| Poor outcome | 0.42 (0.30–0.53) | 22–26 |

| Procedure–specific, complications | ||

| Simple decompression | ||

| Wound infection | 0.04 (0.001–0.08) | 18–20 |

| Anterior transpositions and medial epicondylectomy | ||

| Wound infection§ | 0.09 (0.02–0.16) | 18–21 |

| Medial epicondylectomy | ||

| Valgus instability | 0.03 (0.001–0.07) | 36,37 |

| Flexor–pronator weakness | 0.01 | Expert opinion¶, 38–39 |

| All–procedures, complications | ||

| Scar tenderness | 0.09 (0.03–0.16) | 19,21 |

| Residual paresthesias | 0.11 (0.04–0.18) | 18,21 |

| Neuroma of MACN, MBCN | 0.03 (0.001–0.07) | 18 |

| Poor outcome for neuroma# | 0.38 (0.27–0.50) | 40 |

CI, confidence interval; MACN, medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves; MBCN, medial brachial cutaneous nerves.

A weighted probability was calculated, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the normal approximation for a binomial distribution.

A meta-analysis performed by the Cochrane Collaboration4 using the cited sources defined outcomes as “improvement” and “no improvement,” the latter of which included patients whose symptoms did not improve or worsened. We used the data from the meta-analysis but relabeled “did not improve” as “poor outcome.”

Although Geutjens et al21 did not specify type of “anterior transposition” procedure in the report, the original cited textbook for the surgical technique was identified and confirmed as the anterior submuscular transposition procedure.

Rates for superficial and deep infections were combined and used as probabilities for procedures with larger incisions.

A confidence interval for flexor-pronator weakness could not be calculated because no studies were identified quantifying a discrete number of patients with this complication. An estimate of 0.01 is reported as expert opinion, with references reporting the rarity and subjective nature of this complication.

This value represents the chance of a poor outcome after a neurolysis procedure for a neuroma.

Data analysis

Health utilities.

Independent-sample t-tests were conducted to find significant differences between means of utilities.

Quality-adjusted life-years.

Utilities were translated into quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), a weighted sum of the time spent in a health state multiplied by the utility of the health state.27 For a 50-year-old man, we assumed a remaining life span of 31 years based on the national Vital Statistics Expectation of Life data.28 An average age of 50 years was based on a meta-analysis reporting the average age of a diagnosed patient to be 52 to 53 years.29 All QALYs were discounted to the present value using a 3% discount rate (Appendix A; available on the Journal’s Web site at www.jhandsurg.org).17

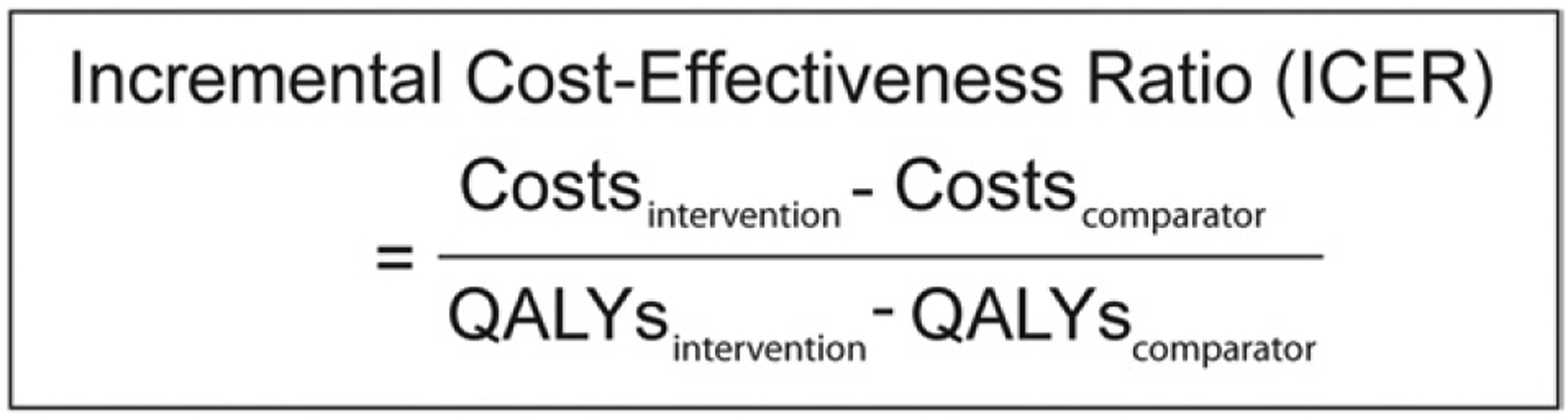

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio is calculated by taking the difference in the costs divided by the difference in the utility of 2 strategies (Fig. 3).17 It is a measure of the additional cost for a unit of health benefit (ie, QALY) gained by using one treatment strategy versus an alternative strategy. Interventions are considered cost-effective when the incremental effectiveness or health benefit gained is deemed worth the additional cost compared to a competing alternative. An intervention is considered dominated when the total costs are higher but the total effectiveness is lower than a competing strategy.17

FIGURE 3:

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio equation.

Sensitivity analysis.

Two sensitivity analyses were performed to examine 2 types of uncertainties: parameter uncertainty and modeling uncertainty. Parameter uncertainty was evaluated by performing a multi-way sensitivity analysis. A multi-way analysis varies multiple parameters simultaneously. We varied all the utilities in a single multi-way sensitivity analysis using the mean utility amount subtracted by the value of standard error. Second, modeling uncertainty was evaluated by varying the modeling assumptions of the decision tree to reflect clinical practice variations. For example, many surgeons re-explore a poor outcome after an initial anterior submuscular transposition surgery. We modeled a re-exploration surgery branch following a poor outcome after an initial anterior submuscular transposition surgery in a second decision tree (Fig. 4). We assumed the utility for a re-exploration to be similar to the utility for simple decompression. All other parameters and assumptions remained the same as the reference case analysis.

FIGURE 4:

Schematic of decision tree for model structural sensitivity analysis. A revision surgery following a poor outcome for anterior submuscular transposition was modeled to account for the possibility that some surgeons perform a re-exploration of a poor outcome after an initial surgery (red dotted branch).

*After salvage surgery, possible complications following a poor outcome include no complication, superficial wound infection, scar tenderness beyond 4 months, and continued paresthesias with worsening UNE (ie, claw).

†After simple decompression, anterior subcutaneous transposition, and anterior submuscular transposition, possible complications following a poor outcome include no complication, scar tenderness beyond 4 months, superficial wound infection, persistent paresthesias in the ring and small fingers, and neuromas of the medial brachial or antebrachial cutaneous nerves.

‡After medial epicondylectomy, possible complications following a poor outcome include no complication, scar tenderness beyond 4 months, superficial wound infection, persistent paresthesias in the ring and small fingers, neuromas of the medial brachial or antebrachial cutaneous nerves, flexor-pronator weakness, and valgus instability.

††After simple decompression, anterior subcutaneous transposition, anterior submuscular transposition, and salvage surgery, possible complications following a good outcome include no complication, scar tenderness beyond 4 months, and superficial wound infection.

‡‡Possible complications following a good outcome include no complication, scar tenderness beyond 4 months, superficial wound infection, flexor-pronator weakness, and valgus instability.

RESULTS

Utility survey

The surveys were completed by 117 subjects. Responses were considered invalid and were excluded if the respondent was unable to understand the questions, the responses were mostly missing, or the ordering of the health states was illogical (ie, the amount traded for avoiding an elbow scar or localized scar tenderness was greater than the amount traded for avoiding a chronically debilitating condition, such as a neuroma or claw hand). The final sample included 102 subjects. Demographic information is presented in Table 3. Responses for each scenario were combined, and utilities were calculated (Table 4 and Appendix B; available on the Journal’s Web site at www.jhandsurg.org). Simple decompression and anterior subcutaneous transposition were preferred and had higher utilities than anterior submuscular transposition and medial epicondylectomy. No significant difference in utilities emerged between simple decompression and anterior subcutaneous transposition (P = .40). Anterior submuscular transposition and medial epicondylectomy had the lowest utilities but were not significantly different from each other (P = .33). Anterior submuscular transposition was the least preferred procedure and was significantly different from simple decompression (P < .001) and anterior subcutaneous transposition (P = .01).

TABLE 3.

Demographics of Survey Respondents

| Characteristics* | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| M | N = 42 (41.2%) |

| F | N = 60 (58.8%) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 39 years (± 14 years) |

| Race | |

| American Indian or Alaskan native | N = 3 (2.9%) |

| Asian | N = 14 (13.7%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | N = 11 (10.8%) |

| White | N = 70 (68.6%) |

| Other | N = 3 (2.9%) |

| Education level | |

| High school graduate | N = 8 (7.8%) |

| Some college | N = 18 (17.6%) |

| College graduate | N = 37 (36.3%) |

| Professional or graduate school | N = 35 (34.3%) |

| Income level | |

| Less than $10,000 | N = 5 (4.9%) |

| $10,000-$19,999 | N = 11 (10.8%) |

| $20,000-$29,999 | N = 9 (8.8%) |

| $30,000-$39,999 | N = 5 (4.9%) |

| $40,000-$49,999 | N = 10 (9.8%) |

| $50,000-$59,999 | N = 10 (9.8%) |

| $60,000-$69,999 | N = 7 (6.9%) |

| More than $70,000 | N = 40 (39.2%) |

Values may not sum to 100% because some respondents chose not to answer all demographic questions.

TABLE 4.

Utility Values (Preferences) of Health States

| Health State | Utility (±SE) |

|---|---|

| Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow (n = 91) | 0.82 (± 0.03) |

| Treatment options | |

| Simple decompression (n = 49) | 0.98 (± 0.01) |

| Anterior subcutaneous transposition (n = 50) | 0.99 (± 0.01) |

| Anterior submuscular transposition (n = 50) | 0.82 (± 0.04) |

| Medial epicondylectomy (n = 50) | 0.88 (± 0.04) |

| Scars | |

| 4-cm scar (n = 49) | 0.98 (± 0.01) |

| 8-cm scar (n = 48) | 0.96 (± 0.03) |

| 8-cm scar with ulnar nerve positioned superficially under skin* (n = 50) | 0.95 (± 0.02) |

| Complications | |

| Superficial skin infection (n = 50) | 0.92 (± 0.03) |

| Paresthesias in 4th and 5th digits (n = 49) | 0.86 (± 0.04) |

| Valgus instability (n = 50) | 0.89 (± 0.03) |

| Neuroma of MACN and MBCN (n = 50) | 0.78 (± 0.04) |

| Local scar tenderness (n = 51) | 0.97 (± 0.09) |

| Flexor-pronator weakness (n = 50) | 0.85 (± 0.04) |

| Claw hand (n = 49) | 0.74 (± 0.05) |

MACN, medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves; MBCN, medial brachial cutaneous nerves; SE, standard error.

After anterior subcutaneous transposition.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for the reference case

In the reference case, medial epicondylectomy had both higher total costs and lower total QALYs (Table 5, Figure 5). Anterior submuscular transposition had the lowest total QALYs and costs. However, this strategy did not accrue further costs after the initial surgery because no further revision procedures were performed for a poor outcome after anterior submuscular transposition (Fig. 1). Simple decompression emerged as the most preferred and effective surgery. Figure 5A–B presents the results in a cost-effectiveness plane. Anterior submuscular transposition is presented at the origin as the comparator. Both simple decompression and anterior subcutaneous transposition fell into the northeast quadrant, where both procedures accrued greater QALYs but at a higher cost. However, simple decompression resulted in greater total QALYs.

TABLE 5.

Total Cost, Utilities, and Incremental Cost-Utility Ratios for the Reference Case*

| Strategy | Total Costs (US$)† | Total Effectiveness (QALYs)† | Incremental Costs (US$) | Incremental Effectiveness (QALYs) | ICER (US$/QALYs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior submuscular transposition | $2,033 | 2.58 | — | — | — |

| Anterior subcutaneous transposition | $2,181 | 2.72 | $148 | 0.14 | $1,078 |

| Simple decompression | $2,260 | 2.76 | $80 | 0.04 | $2,027 |

| Medial epicondylectomy | $3,219 | 2.64 | $958 | −0.11 | (Dominated) |

ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Both simple decompression and anterior subcutaneous transposition procedures accrued greater total QALYs but at a higher total cost. However, because simple decompression accrued the highest total QALYs with an ICER below the accepted threshold of $100,000 $/QALY, simple decompression is considered the most effective treatment strategy. See Figure 5 for interpretation of this table.

Total costs represent total over the projected 3-year time horizon and are in 2009 US dollars. Costs are rounded to the nearest US$1. All costs and QALYs are discounted at 3%.

FIGURE 5:

Cost-effectiveness plane. A The results of a cost-effectiveness analysis are typically presented by the 4-quadrant cost-effectiveness plane. A comparator procedure or intervention is indicated at the origin of the plane, and the alternative procedures are plotted relative to the comparator. Each quadrant is labeled as the NW, NE, SE, or SW quadrant. The southern quadrants are cost-saving, and interventions that fall into the SE quadrant are considered dominant; that is, it costs less and has greater total effectiveness. These interventions are typically accepted. However, interventions that fall into the SW quadrant are debated because there is a trade-off. Although it is cost saving, it is less effective. Interventions that fall into the NW quadrant are dominated; that is, they cost more and are less effective. These interventions are typically rejected. Finally, interventions that fall into the NE quadrant are also debated, given that there is a trade-off. Although they are more effective, they are also more costly. The dotted line represents the cost-effectiveness threshold value ($/QALY). Interventions that fall under the threshold in the NE quadrant are considered cost-effective. B The results for the reference case analysis are presented in the cost-effectiveness plane. The origin represents anterior submuscular transposition. Medial epicondylectomy was a dominated strategy (higher cost, lower effectiveness) and fell into the NW quadrant. It should thus be rejected. However, both simple decompression and anterior subcutaneous transposition fell into the NE quadrant, indicating that there is a trade-off (higher costs but also greater effectiveness). Abbreviations: NE, northeast; NW northwest; SE, southeast; SW, southwest.

Sensitivity analyses

Because simple decompression, anterior submuscular transposition, and anterior subcutaneous transposition are coded under the same surgery and anesthesia Current Procedural Terminology codes, cost parameters were not strong drivers of the model. We therefore focused on the utilities in a multi-way sensitivity analysis in which all the utilities were varied simultaneously. Despite using lower utilities, simple decompression remained the most preferred and effective strategy compared to anterior subcutaneous transposition (Appendix C; available on the Journal’s Web site at www.jhandsurg.org).

For the model structure sensitivity analysis (Fig. 4) the re-exploration surgery branch following a poor outcome after an initial anterior submuscular transposition surgery increased the total costs of the anterior submuscular transposition strategy (Appendix D; available on the Journal’s Web site at www.jhandsurg.org). The assumption that a re-exploration surgery after an initial anterior submuscular transposition surgery would be performed resulted in both the anterior submuscular transposition and medial epicondylectomy strategies being dominated by simple decompression. Simple decompression remained the most preferred and effective procedure.

DISCUSSION

This study compared 4 different surgical strategies for UNE. Based on these study results, simple decompression emerged as both the preferred and the most effective surgery compared to anterior subcutaneous transposition. Medial epicondylectomy was dominated because it emerged with higher costs and was less effective than simple decompression and anterior subcutaneous transposition. The use of 2 Current Procedural Terminology codes for the medial epicondylectomy procedure might be considered unbundling. However, because medial epicondylectomy was a less preferred strategy with a significantly lower utility value than simple decompression, assigning 1 Current Procedural Terminology code is unlikely to change the results. In fact, these results remained consistent and robust, despite varying the input parameters and model assumptions, thereby strengthening the conclusion that simple decompression was cost-effective compared to the considered alternatives under the commonly accepted cost-effective thresholds ranging from US$50,000 to US$100,000 per QALY.30,31

The conclusions from this analysis are consistent with a previously published decision analysis examining the same 4 surgical strategies for UNE. A decision analysis using a 2-year time horizon reported simple decompression as the initial surgery for idiopathic UNE to be the preferred strategy.32 Despite similar conclusions, methodological differences between their and our decision analysis exist in the parameter inputs and modeling assumptions. Furthermore, the study was not an economic evaluation.

A cost-minimization analysis from the Netherlands using a 1-year time horizon was published based on a randomized, controlled trial comparing simple decompression and anterior subcutaneous transposition.18,33 A statistically significant difference in the median costs between patients treated with simple decompression versus anterior subcutaneous transposition was reported. This result was primarily driven by lengthier sick-leave durations after anterior subcutaneous transposition. The authors attributed this finding to the Netherlands’ social security system, which provides compensation for sick leave. An analysis excluding sick leave costs still revealed simple decompression as the cheaper alternative. This difference was attributed to significantly different surgical times resulting in significantly higher fee-per-minute costs (including fees for surgeon, anesthesia, and operating room).

This study has several limitations. First, the model of the decision tree was based on assumptions. For example, the probability values for a poor outcome after the initial procedure were obtained from a meta-analysis that dichotomized patient groups into improvement (good outcome) and no improvement (poor outcome). All patients without improvement were assumed to have a salvage procedure in the model. We acknowledge that such assumptions do not represent all practice patterns or patient preferences, given that not all patients without improvement or who experience a neuroma might want to proceed with additional surgery. The assumptions were made to simplify the portrayal of reality to allow for insightful analysis useful for decision making, and the inferences are drawn from the available evidence-based data. No model can be a perfect representation of reality, given the myriad of possibilities. Thus, the validity of the model rests on sensible assumptions.17

Second, the generalizability of the study is limited to the U.S. health care system, particularly in light of the cost derivations. Generalizability is the extent to which the study results conducted in a particular patient population or a specific context can hold true for another population or in a different context.34 Economic evaluations are typically considered not generalizable due to variability in the availability of health care resources, practice patterns, and payment structures.36 Nonetheless, we followed a checklist aimed at enhancing transparency and improving the generalizability of decision analyses by specifying in which context the results are best applicable.35

This study is vulnerable to selection bias. The sample recruited for the TTO survey was composed of friends and family of patients from a plastic surgery and neurosurgery clinic waiting room. Subjects who were friends, family, or caregivers of chronically ill patients believed that they had higher tolerances to pain or a disabling condition than community members without direct contact with chronically ill patients. Therefore, the utilities used for the reference case analysis might have been higher than if the survey was administered to community members who were not exposed to chronically ill patients or children. To account for this bias, we performed a multi-way sensitivity analysis. Simple decompression, nevertheless, remained the preferred and most effective surgery compared to the considered alternatives.

Finally, we followed the recommendations of the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine and recruited the described convenience sample as a community sample to represent the societal perspective for the reference case analysis. However, it might be argued that a healthy individual cannot truly understand a condition that he or she has not experienced, and the results might have been different if patient preferences were captured for the described health states.

The results from this study can assist in evaluations and decision making for surgical treatment of UNE. We showed that initial treatment for patients with UNE with simple decompression was both a preferred and effective strategy under a variety of assumptions. However, future research should explore surgical effectiveness by patient subgroups (eg, patients with diabetes or negative electrodiagnostic studies).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lynda J.S. Yang, MD, PhD, and Paul S. Cederna, MD, for allowing use of their clinic waiting room for subject recruitment and Lauren Franzblau for help with article retrieval.

This project was supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards for Individual Postdoctoral Fellows (F32 AR058105) (J.W.S.) and from the Department of Pediatrics and Communicable Diseases (L.A.P.). This project was also supported in part by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) and a grant (R01 AR062066) from the National Institute on Aging and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (2R01 AR047328-06) (K.C.C.).

APPENDIX A.

Terminology*

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Convenience sampling | A method of sampling in which subjects are selected based on their convenient accessibility to the researcher. |

| Cost-effectiveness ratio | The incremental cost of obtaining a unit of health effect (eg, dollars per year, per quality-adjusted year) from a given health intervention, when compared to an alternative intervention. |

| Decision analysis | A quantitative and systematic approach to decision making under conditions of uncertainty in which probabilities of each possible event, the consequences of those events, and assumptions under which the circumstances occur are stated. |

| Decision theory | A framework for analyzing decisions under uncertainty by positing an alternative set of actions by a set of possible outcomes and a set of probabilities corresponding to each outcome. |

| Discounting | The process of converting future money and future health outcomes to their present value. |

| Dominated | The state of an intervention or strategy that costs more but is less effective than the considered alternative; it can be removed from consideration. |

| Health state | A description of the health of an individual at any particular point of a defined time period. In this study, one example of a temporary health state is the experience of having a surgical procedure. |

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio | The ratio of the difference in costs between two alternatives to the difference in effectiveness between the same two alternatives. |

| Preferences | A numerical value representing a judgment of the desirability of a particular outcome (eg, a described health state) or situation. |

| Sensitivity analysis | An analysis that allows one to test the uncertainty of a parameter in a model and examine whether varying the parameter will change the results. |

| One-way sensitivity analysis | Only one parameter is changed in the model at one time. |

| Multi-way sensitivity analysis | More than one parameter is changed in the model simultaneously. |

| Model structure sensitivity analysis | The model structure of the decision tree is altered by adding or subtracting branches and thereby tests a model’s assumption. |

| Societal perspective | The broadest perspective; it includes all program costs and outcomes to society. |

| Time trade-off (TTO) survey | A survey method of measuring health state utilities in which subjects are asked to trade-off life years in a state of less-than-perfect health for a shorter life span in a state of perfect health. The ratio of the number of years of perfect health that is equivalent to a longer life span in less-than-perfect health provides a measure of the preference for that health state. |

| Utility | A quantitative concept in economics, psychology, and decision analysis that is used to represent the relative desirability of a specified description of a particular outcome (eg, a health state). |

| Sample calculation of a utility | In a time trade-off survey, the respondent is provided with a described scenario and asked to make a choice about the amount of time that he or she would be willing to give up to avoid experiencing the described scenario (see definition of time trade-off survey). The point at which the respondent cannot decide or feels that there is no difference between trading off or giving up a given amount of time presented to him or her is called the indifference point. This period of time is used to calculate the participant’s utility for the described health state (Utility = YIndifference/number of years left to live). |

References:

Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1996:1–411.

Hunink M, Glasziou P, Siegel J, Weeks J, Pliskin J, Elstein A, et al. Decision making in health and medicine: integrating evidence and values. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001:1–388.

APPENDIX B:

Time trade-off survey design. A Four versions of the time trade-off surveys with 7 to 9 scenarios each were designed. Both the scenarios and sequences of the scenarios were varied to reduce anchoring bias (see “Materials and Methods” for details). B Respondents were randomized to 1 of the 4 surveys. A total of 117 respondents completed 1 of the 4 surveys. Fifteen respondents’ responses were excluded for the following reasons: (1) inability to understand the questions based on their comments, (2) responses were mostly missing, or (3) the ordering of the health state was illogical. A total of 102 respondents’ responses were considered valid and were used to calculate utilities.

APPENDIX C.

Total Cost, Utilities, and Incremental Cost-Utility Ratios for the Multi-way Sensitivity Analysis

| Strategy | Total Costs (US$)* | Total QALYs * | Incremental Costs (US$) | Incremental Effectiveness (QALYs) | ICER (US$/QALYs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior submuscular transposition | $2,029 | 2.02 | — | — | — |

| Anterior subcutaneous transposition | $2,181 | 2.30 | $152 | 0.29 | $534 |

| Simple decompression | $2,260 | 2.42 | $80 | 0.12 | $686 |

| Medial epicondylectomy | $3,439 | 2.02 | $1,178 | −0.39 | (Dominated) |

QALYs, quality-adjusted life-years; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Total costs represent total over the projected 3-year time horizon. Costs are rounded to the nearest US$1. All costs and QALYs are discounted at 3%.

APPENDIX D.

Total Cost, Utilities, and Incremental Cost-Utility Ratios for the Model Structure Sensitivity Analysis

| Strategy | Total Costs (US$)* | Total QALYs* | Incremental Costs (US$) | Incremental Effectiveness (QALYs) | ICER ($/QALYs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior subcutaneous transposition | $2,181 | 2.72 | — | — | — |

| Simple decompression | $2,260 | 2.78 | $80 | 0.04 | $1,975 |

| Anterior submuscular transposition | $2,830 | 2.66 | $570 | −0.09 | (Dominated) |

| Medial epicondylectomy | $3,439 | 2.65 | $1,178 | −0.11 | (Dominated) |

QALYs, quality-adjusted life-years; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Total costs represent total over the projected 3-year time horizon. Costs are rounded to the nearest $1. All costs and QALYs are discounted at 3%.

Footnotes

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chung KC. Treatment of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. J Hand Surg 2008;33A:1625–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin R, Ring D. The ulnar nerve in elbow trauma. J Bone Joint Surg 2007;89A:1108–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartels RH, Menovsky T, Van Overbeeke JJ, Verhagen WI. Surgical management of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow: an analysis of the literature. J Neurosurg 1998;89:722–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caliandro P, La Torre G, Padua R, Giannini F, Padua L. Treatment for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;2:CD006839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macadam SA, Bezuhly M, Lefaivre KA. Outcomes measures used to assess results after surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. J Hand Surg 2009;34A:1482–1491, e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunink M, Glasziou P, Siegel J, Weeks J, Pliskin J, Elstein A, et al. Decision making in health and medicine: integrating evidence and values. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001:1–388. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Detsky AS, Naglie G, Krahn MD, Naimark D, Redelmeier DA. Primer on medical decision analysis: Part 1—Getting started. Med Decis Making 1997;17:123–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torrance GW. Preferences for health outcomes and cost-utility analysis. Am J Manag Care 1997;3 Suppl:S8–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osterman AL, Davis CA. Subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin 1996;12: 421–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellon AL. Review of treatment results for ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow. J Hand Surg 1989;14A:688–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel DB. Submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve. Hand Clin 1996;12:445–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumann PJ, Goldie SJ, Weinstein MC. Preference-based measures in economic evaluation in health care. Annu Rev Public Health 2000;21:587–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prosser LA, Ray GT, O’Brien M, Kleinman K, Santoli J, Lieu TA. Preferences and willingness to pay for health states prevented by pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatrics 2004;113:283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith S, Fischoff R, Klemp T. Medicare RBRVS 2009: The physicians’ guide. Chicago: American Medical Association, 2009:1–563. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray L Red book: pharmacy’s fundamental reference. Montvale, New Jersey: Thomson Healthcare, 2008:1–1012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available at: http://www.bls.gov. Accessed April 3, 2010.

- 17.Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1996:1–411. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartels RH, Verhagen WI, van der Wilt GJ, Meulstee J, van Rossum LG, Grotenhuis JA. Prospective randomized controlled study comparing simple decompression versus anterior subcutaneous transposition for idiopathic neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow: Part 1. Neurosurgery 2005;56:522–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gervasio O, Gambardella G, Zaccone C, Branca D. Simple decompression versus anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve in severe cubital tunnel syndrome: a prospective randomized study. Neurosurgery 2005;56:108–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biggs M, Curtis JA. Randomized, prospective study comparing ulnar neurolysis in situ with submuscular transposition. Neurosurgery 2006;58:296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geutjens GG, Langstaff RJ, Smith NJ, Jefferson D, Howell CJ, Barton NJ. Medial epicondylectomy or ulnar-nerve transposition for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow? J Bone Joint Surg 1996;78B:777–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broudy AS, Leffert RD, Smith RJ. Technical problems with ulnar nerve transposition at the elbow: findings and results of reoperation. J Hand Surg 1978;3A:85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabel GT, Amadio PC. Reoperation for failed decompression of the ulnar nerve in the region of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg 1990;72A: 213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmberg J Reoperation in high ulnar neuropathy. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1991;25:173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartels RH, Grotenhuis JA. Anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve. For post-operative focal neuropathy at the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg 2004;86B:998–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogel RB, Nossaman BC, Rayan GM. Revision anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve for failed subcutaneous transposition. British J Plast Surg 2004;57:311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naglie G, Krahn MD, Naimark D, Redelmeier DA, Detsky AS. Primer on medical decision analysis: Part 3—Estimating probabilities and utilities. Med Decis Making 1997;17:136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arias E United States life tables, 2004. National Vital Statistics Report 2007;56:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macadam SA, Gandhi R, Bezuhly M, Lefaivre KA. Simple decompression versus anterior subcutaneous and submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve for cubital tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Hand Surg 2008;33A:1314.e1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bridges JF, Onukwugha E, Mullins CD. Healthcare rationing by proxy: cost-effectiveness analysis and the misuse of the $50,000 threshold in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 2010;28:175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grosse SD. Assessing cost-effectiveness in healthcare: history of the $50,000 per QALY threshold. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2008;8:165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brauer CA, Graham B. The surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: a decision analysis. J Hand Surg 2007;32E:654–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartels RH, Termeer EH, van der Wilt GJ, van Rossum LG, Meulstee J, Verhagen WI, et al. Simple decompression or anterior subcutaneous transposition for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow: a cost-minimization analysis—Part 2. Neurosurgery 2005;56:531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sculpher MJ, Pang FS, Manca A, Drummond MF, Golder S, Urdahl H, et al. Generalisability in economic evaluation studies in healthcare: a review and case studies. Health Technol Assess 2004;8:iii–iv, 1–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drummond M, Manca A, Sculpher M. Increasing the generalizability of economic evaluations: recommendations for the design, analysis, and reporting of studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005;21: 165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amako M, Nemoto K, Kawaguchi M, Kato N, Arino H, Fujikawa K. Comparison between partial and minimal medial epicondylectomy combined with decompression for the treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg 2000;25A:1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Froimson AI, Anouchi YS, Seitz WH Jr, Winsberg DD. Ulnar nerve decompression with medial epicondylectomy for neuropathy at the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1991;265:200–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heithoff SJ, Millender LH, Nalebuff EA, Petruska AJ Jr. Medial epicondylectomy for the treatment of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. J Hand Surg 1990;15A:22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osterman AL, Spiess AM. Medial epicondylectomy. Hand Clin 2007;23:329–337, vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarris I, Gobel F, Gainer M, Vardakas DG, Vogt MT, Sotereanos DG. Medial brachial and antebrachial cutaneous nerve injuries: effect on outcome in revision cubital tunnel surgery. J Reconstr Microsurg 2002;18:665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]