Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected more than 96 million people worldwide, leading the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a pandemic in March 2020. Although an optimal medical treatment of COVID-19 remains uncertain, an unprecedented global effort to develop an effective vaccine hopes to restore pre-pandemic conditions. Since cancer patients as a group have been shown to be at a higher risk of severe COVID-19, the development of safe and effective vaccines is crucial. However, cancer patients may be underrepresented in ongoing phase 3 randomised clinical trials investigating COVID-19 vaccines. Therefore, we encourage stakeholders to provide real-time data about the characteristics of recruited participants, including clearly identifiable subgroups, like cancer patients, with sample sizes large enough to determine safety and efficacy. Moreover, we envisage a prompt implementation of suitable registries for pharmacovigilance reporting, in order to monitor the effects of COVID-19 vaccines and immunisation rates in patients with cancer. That said, data extrapolation from other vaccine trials (e.g. anti-influenza virus) showed a favourable safety and efficacy profile for cancer patients. On the basis of the evidence discussed, we believe that the benefits of the vaccination outweigh the risks. Consequently, healthcare authorities should prioritise vaccinations for cancer patients, with the time-point of administration agreed on a case-by-case basis. In this regard, the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the European Society of Medical Oncology are advocating for cancer patients a high priority status, in the hope of attenuating the consequences of the pandemic in this particularly vulnerable population.

Keywords: COVID-19, Sars-CoV-2, Vaccine, Pandemics, Trial, Public health, Cancer, Advocacy

1. Introduction

Since the first reports of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected more than 96 million people worldwide, leading the World Health Organization (WHO) to claim a public health emergency in late January 2020 and a pandemic in March 2020 [1]. At present, an optimal medical treatment of COVID-19 remains uncertain. Besides oxygen therapy and positive pressure ventilation, glucocorticoids, dexamethasone in particular, showed a mortality benefit in patients requiring respiratory support, while this benefit was not clear among patients who did not require respiratory support [2,3]. As for remdesivir, a novel antiviral medication, although it may accelerate the time to recovery, it did not show an overall mortality benefit [4,5]. As well, convalescent plasma did not demonstrate a clear clinical benefit in hospitalised patients with severe COVID-19 [6]. Consistently, on 14th January 2021, the Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) closed recruitment to the convalescent plasma arm of the trial [7]. Finally, two monoclonal antibody therapies targeting SARS-CoV-2 (bamlanivimab and the combination casirivimab–imdevimab) have received emergency use authorisation from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for non-hospitalised patients who have mild to moderate COVID-19 and certain risk factors for severe disease on the basis of preliminary reports of randomised trials [[8], [9], [10]]. However, an unprecedented global effort in order to develop an effective vaccine strategy hopes to restore pre-pandemic routine [11,12].

Since the history of cancer seems to be related to higher mortality rates due to COVID-19, the development of safe and effective vaccines may be crucial for this group of patients [13]. Indeed, there are about 32 million cancer survivors worldwide, with almost 1.8 million new cancer cases projected to have occurred in the United States in 2020 [14].

This review will highlight the current landscape of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates, with a special focus on implications for cancer patients.

2. SARS-CoV-2 biology and clinical features

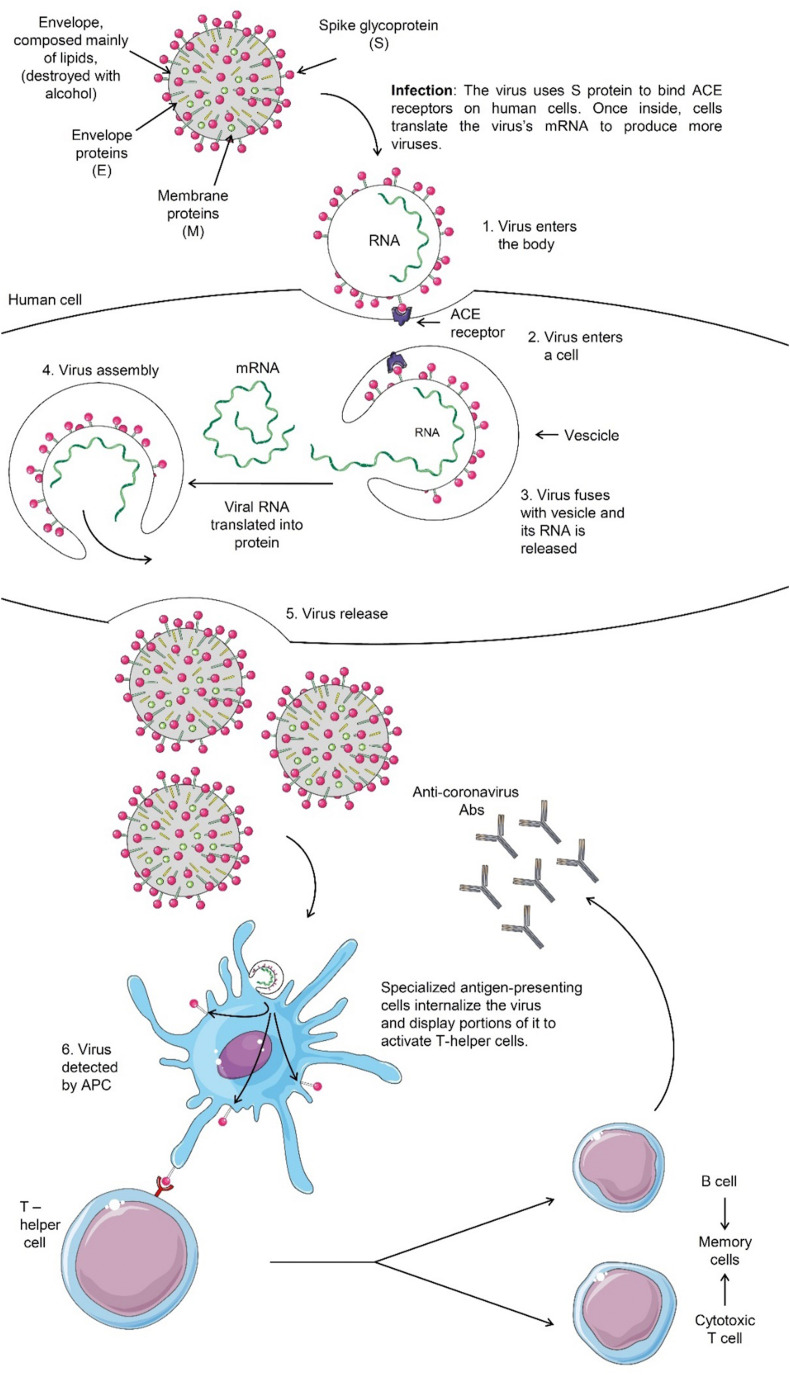

Coronaviruses are a highly diverse family of enveloped positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses [15]. Like other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 has four structural proteins, namely the S (spike), E (envelope), M (membrane) and N (nucleocapsid) proteins (Fig. 1 ) [15].

Fig. 1.

Structure of SARS-CoV-2 virus and its replication kinetics [15]. The N protein holds the RNA genome, and the S, E and M proteins together form the viral envelope. The spike glycoprotein is responsible for allowing the virus to attach to and fuse with the membrane of a host cell. Specifically, its S1 subunit catalyses attachment and the S2 subunit enables fusion (not shown) [15]. Abbreviations: S, spike; E, envelope; M, membrane; N, nucleocapsid; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; APC, antigen-presenting cell; Abs, antibodies.

Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection can range from mild to critical, with mild disease (asymptomatic patient or mild pneumonia) accounting for ~80% of cases [16]. However, the proportion of asymptomatic infections has not been systematically and prospectively studied [16]. The average prevalence of critical illness is higher among hospitalised patients [17]. Severe disease predominantly occurs in adults with advanced age or harbouring medical comorbidities, such as cancer [17]. Cough, headache and myalgias are the most frequent symptoms [17]. Other features, including sore throat, diarrhoea and smell or taste abnormalities, are described as well [17]. Pneumonia is the most common serious manifestation of the infection, characterised by cough, fever and dyspnoea, with bilateral infiltrates on chest imaging [17]. Humoral immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 are mediated by antibodies that are directed to viral surface glycoproteins, such as the spike glycoprotein receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the nucleocapsid protein [18]. Both CD4+ T-cell and CD8+ T-cell responses have been described in patients infected by SARS-CoV-2, with Th1 cytokine production [19]. However, the contribution of cellular immunity to protection against COVID-19 is not entirely clear [19].

3. Biological and clinical data about SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates

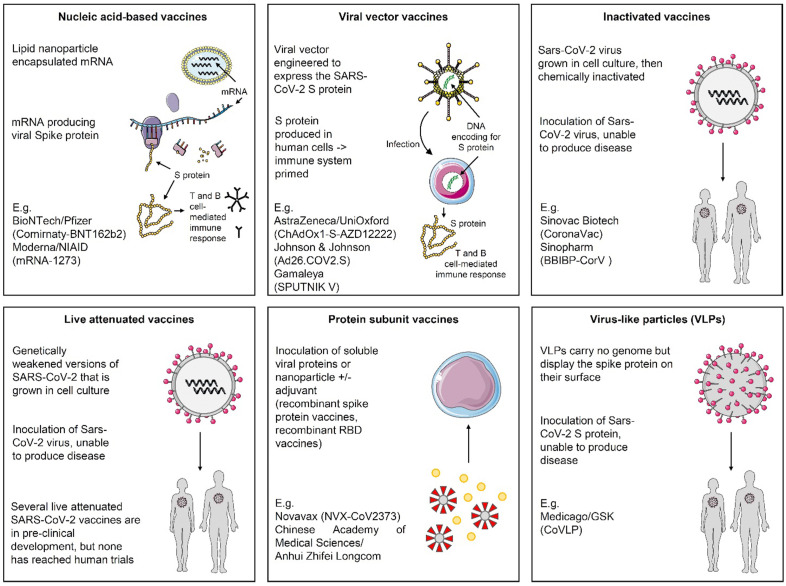

Because vaccines to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection are considered the most promising approach for controlling the pandemic, an unprecedented effort was made since the beginning of 2020 in order to develop an effective vaccine strategy. As of 17th January 2021, 40 vaccine candidates are being tested for prevention of COVID-19 in phase I clinical trials, followed by 24 and 20 vaccine candidates investigated in phase 2 and 3 trials, respectively (Fig. 2 ) [20].

Fig. 2.

Principal mechanisms of action for COVID-19 vaccine candidates in late-phase clinical trials. These include live-attenuated or inactivated vaccines, replication-incompetent or -competent vector vaccines, recombinant protein subunits and nucleic acid-based vaccines [20]. Abbreviations: mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; S, spike, GSK, GlaxoSmithKline; UniOxford, University of Oxford; RBD, receptor-binding domain.

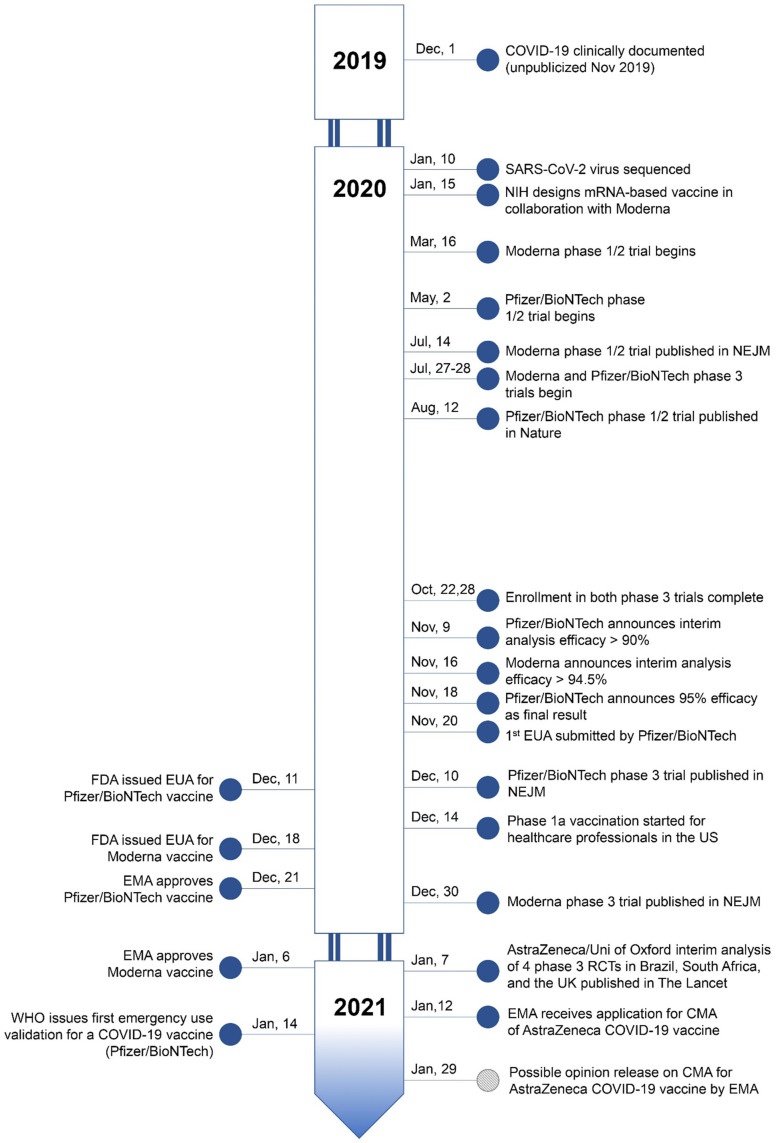

Since early-phase trials, numerous candidates were shown to induce binding antibodies, neutralising activity, and T cell responses in healthy adults [3]. A few candidates appeared to be immunogenic in healthy older individuals, as well [3]. To date, BNT162b2 (Comirnaty – Pfizer/BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna) are the only vaccines authorised for Emergency Use by both the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). They are messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccines delivered in a lipid nanoparticle to express a full-length spike protein. BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 are given intramuscularly in two doses, 21 and 28 days apart, respectively. In phase III randomised controlled trials (RCTs), these vaccines showed 95% (BNT162b2, 95% confidence interval (CI), 90.3–97.6) and 94.1% efficacy (mRNA-1273, 95% CI, 89.3–96.8) in preventing symptomatic COVID-19 after the second dose [21,22]. On 31st December 2020, the WHO issued its first emergency use validation for Comirnaty, aiming to speed up authorisation in many countries. A summary of COVID-19 vaccine candidates approved or in phase III trials as of January 17, 2021 is provided in Table 1 , with temporal milestones (Fig. 3 ).

Table 1.

COVID-19 vaccine candidates approved or in phase III trials as of January 17, 2021, with details about cancer patient eligibility.

| Developer | Vaccine | Immune Features | Clinical Trial Identifier | Exclusion Criteria for Cancer Patients | Demographic Data (if available) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderna/NIAID | mRNA-1273 (lipid nanoparticle-mRNA) | Expressing S protein; two repeated IM doses 4 w apart. 94.1% efficacy for symptomatic COVID-19 at/after 14d following the II dose |

NCT04470427 Ph 3 ongoing. Emergency authorisation by FDA and EMA. |

People who have received systemic immunosuppressants or immune-modifying drugs for >14 days in total within 6 months prior to screening. | 30,420 volunteers. No cancer patients enumerated. |

| Pfizer/BioNTech | Comirnaty BNT162b2 (lipid nanoparticle-mRNA) |

RBD of S protein; two repeated IM doses 3 w apart. 95% efficacy for symptomatic COVID-19 at/after day 7 following the II dose |

NCT04368728 Ph 3 ongoing. Emergency authorisation by FDA and EMA. WHO Emergency Use Listing |

People receiving immunosuppressive therapy, including cytotoxic agents or systemic corticosteroids, e.g. for cancer. | 43,548 volunteers. No cancer patients enumerated. |

| AstraZeneca/University of Oxford | ChAdOx1 nCov-19 (AZD-1222 or Covishield) (Non-replicating viral vector) |

Expressing S protein; two repeated IM doses 4 w apart. 62.1% efficacy for symptomatic COVID-19 at/after 14d following the II dose (SD/SD). 90% efficacy for symptomatic COVID-19 at 14d following the II dose (LD/SD). |

NCT04516746 NCT04540393 (COV002 and COV003) ISRCTN89951424 CTRI/2020/08/027170 Ph 3 ongoing. |

History of primary malignancy except for malignancy with low potential risk for recurrence after curative treatment or metastasis (for example, indolent prostate cancer) in the opinion of the site investigator. | 23,848 volunteers No cancer patients enumerated. |

| CanSino Biologics | Ad5-nCoV/Convidecia (Non-replicating Adenovirus Type 5 Vector) | Expressing S protein; single IM dose. |

NCT04526990 NCT04540419 Ph 3 ongoing. Limited emergency approval in China |

People with current diagnosis of or treatment for cancer (except basal cell carcinoma of the skin and cervical carcinoma in situ) | No demographic data published or posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| Gamaleya Research Institute | Gam-Covid-Vac (Sputnik V) Adeno-based (rAd26-S + rAd5-S) |

Single-dose and heterologous Ad26 prime; Ad5 boost IM doses, 3 w apart. Efficacy rate 91.4%. |

NCT04530396 (RESIST) NCT04564716 Ph 3 ongoing. Emergency approval in Russia and Belarus. |

History of any malignant tumours. | n.a. |

| Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Johnson & Johnson (Janssen) | Ad26.COV2.S/JNJ-78436735 (Adenovirus Type 26 vector) | Expressing S protein; single IM dose (ENSEMBLE), two IM doses 56 d apart (ENSEMBLE 2). |

NCT04505722 (ENSEMBLE) Ph 3 ongoing. NCT04614948 (ENSEMBLE 2) Ph 3 ongoing. |

Malignancy within 1 year before screening, except squamous and basal cell carcinomas of the skin and carcinoma in situ of the cervix, or other malignancies with minimal risk of recurrence. Patients receiving CT, immune-modulating drugs or RT within 6 months before administration of vaccine and/or during the study. | No demographic data published or posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| Novavax | NVX-CoV2373 (Protein Subunit) | Recombinant S protein; two repeated IM doses, 3 w apart. | (UK) 2020-004123-16/2019nCoV-301 (US) NCT04611802/2019nCoV-301 Ph 3 ongoing. |

(UK) Current diagnosis of or treatment for cancer (except basal cell carcinoma of the skin and cervical carcinoma in situ, at the discretion of the investigator). (US) Active malignancy on therapy within 1 year prior to first study vaccination (with the exception of malignancy cured via excision, at the discretion of the investigator). |

No demographic data published or posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| Medicago /GSK |

CoVLP (plant-derived VLP adjuvanted with GSK or Dynavax adjs) | Two repeated IM doses, 3 w apart. |

NCT04636697 Ph 3 ongoing. |

Any confirmed or suspected immunosuppressive conditions, including cancer. Investigator discretion is permitted. People receiving cytotoxic, antineoplastic or immunosuppressants within 36 months prior to vaccination. |

No demographic data published or posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences/Anhui Zhifei Longcom | COVID-19 vaccine (protein subunit) | Two or three repeated IM doses, 1 month apart |

NCT04466085 (ph 2) Ph 3 ongoing. |

History of any malignant tumours. | n.a. |

| Wuhan Institute of Biological Products/Sinopharm | BBIBP-CorV (Vero Cell, Inactivated) | Multiple viral antigens; two repeated IM doses, 3 w apart |

NCT04560881 NCT04612972 Ph 3 ongoing. Limited emergency approval in China and U.A.E |

History of any malignant tumours. | n.a. |

| Beijing Institute of Biological Products/Sinopharm | BBIBP-CorV (Vero Cell, Inactivated) | Multiple viral antigens; two repeated IM doses, 3 w apart. 79.34% efficacy for symptomatic COVID-19 following the II dose |

NCT04560881 NCT04510207 Ph 3 ongoing. Full approval in U.A.E and Bahrain. Limited emergency approval in China |

History of any malignant tumours. | n.a. |

| Sinovac Biotech | CoronaVac (Inactivated) | Multiple viral antigens; two repeated IM doses, 2 w apart. 50.38% efficacy for symptomatic COVID-19 following the II dose |

NCT04456595 (PROFISCOV) 669/UN6.KEP/EC/2020 NCT04582344 NCT04617483 Ph 3 ongoing. Limited emergency approval in China and Turkey |

Use of CT or RT within 6 months prior to enrolment or planned use within the two years following enrolment. History of malignancy or antineoplastic CT, RT, immunosuppressants in the past 6 months. |

No demographic data published or posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| Indian Council of Medical Research/Bharat Biotech | Covaxin, also known as BBV152 A, B, C (Inactivated) | Multiple viral antigens; two repeated IM doses, 4 w apart | CTRI/2020/11/028976 Ph 3 ongoing. Emergency Authorisation in India |

Treatment with immunosuppressive or cytotoxic drugs or use of anticancer CT or RT within the preceding 36 months. | No demographic data published or posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| CureVac | CVnCoV (Lipid nanoparticle-mRNA) | Two repeated IM doses, 4 w apart |

NCT04652102 EudraCT-2020-004066-19 Ph 3 ongoing. |

Current diagnosis of or treatment for cancer. | No demographic data published or posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| AnGes/Osaka University/Takara Bio | AG0302-COVID19 | Two repeated IM doses, 2 w apart |

NCT04655625 Ph 3 ongoing. |

Drugs that affect the immune system such as DMARDs, immunosuppressants, biologics. | No demographic data published or posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| Anhui Zhifei Longcom/Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences | ZF2001 (Protein subunits) | Adjuvant + spike protein RBD; three repeated IM doses, 4 w apart |

NCT04646590 Ph 3 ongoing. |

Cancer patients (except basal cell carcinoma) | No demographic data published or posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| Clover Biopharmaceuticals/The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness | SCB-2019 | AS03-adjuvanted recombinant trimeric S-protein; two repeated IM doses, 3 w apart |

NCT04672395 Ph 3 ongoing. |

Treatment with immunosuppressive therapy (cytotoxic agents, systemic corticosteroids) or planned receipt during the study period; history of malignancy within 1 year before screening | No demographic data published or posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences | Vero cell (Inactivated) | Two repeated IM doses, 2 w apart |

NCT04659239 Ph 3 ongoing. |

History of malignant tumours | No demographic data published or posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| Zydus Cadila | ZyCov-D (DNA) | Three doses, 4 w apart | Ph 3 about to start | n.a. | n.a. |

| Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems (Kazakhstan) | QazCovid | Two repeated IM doses, 3 w apart | NCT04691908 | History of any malignant tumours. | n.a. |

| Murdoch Children's Research Institute | BCG | BCG |

NCT04327206 (BRACE) Ph 3 ongoing. |

History of any malignant tumours. | n.a. |

Abbreviations: FDA, Food and Drug Administration; EMA, European Medical Agency; WHO, World Health Organization; d, days; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; IM, intramuscular; SD, standard dose; LD, low dose; RBD, receptor-binding domain; COVID, coronavirus disease; Abs, antibodies; w, weeks; Ad, Adenovirus; n.a., not applicable; S protein, Spike protein; NIAID, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; CT, chemotherapy; RT, radiotherapy; VLP, virus-like particles; adjs, adjuvants; GSK, GlaxoSmithKline; DMARDs: disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; ph, phase; BCG, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, US, United States; EU, European Union; U.A.E, United Arab Emirates.

Fig. 3.

Temporal milestones in the development and approval of COVID-19 vaccine candidates as of January 17, 2021. Abbreviations: COVID, coronavirus disease; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; NIH, National Institutes of Health; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; NEJM, New England Journal of Medicine; EUA, Emergency Use Authorisation; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; EMA, European Medicines Agency; WHO, World Health Organisation; US, United States; Uni of Oxford, University of Oxford; RCT, randomised controlled trial; UK, United Kingdom; CMA, conditional marketing authorisation; Nov, November; Dec, December; Mar, March; Jul, July; Aug, August; Oct, October; Jan, January.

4. Prognosis of cancer patients with COVID-19

In 2020, about 1.8 million new cancer cases are projected to have occurred in the United States, with an estimated 32 million cancer survivors worldwide [14]. COVID-19 seems to be related to a higher mortality in cancer patients, with rates ranging from 5% to 61% according to the cohorts studied [13]. Overall, active disease confers a significantly increased risk of severe COVID-19; similarly, haematological, lung malignancies and the presence of metastatic disease are associated with a persistently increased risk [13,[23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]]. To appropriately assess COVID-19 outcomes in cancer patients, the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19) database collected data of patients from the USA, Canada and Spain with active or previous malignancy and a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection [13]. Mortality reached 13% (121/928), with all dying patients experiencing the event within 30 days from COVID-19 diagnosis [13]. Another international effort, namely the Thoracic Cancers International COVID-19 Collaboration (TERAVOLT) registry, focused on outcomes of patients with thoracic malignancies developing COVID-19 [29]. Among 200 patients with a thoracic tumour and a confirmed or suspected diagnosis of COVID-19, 66 (33%) died, with few people (10%) ultimately admitted to an intensive care unit [29]. The high lethality of thoracic tumours, together with the possible exclusion from intensive care due to triage reasons, might have accounted for the high mortality observed [29]. As well, big national cohorts from Canada, France and the Netherlands confirmed such worse outcome [[24], [25], [26]]. A pooled analysis of 52 registries of cancer patients with COVID-19 identified a pooled case mortality rate of 25.6%, supporting the idea that oncological patients may be a particularly vulnerable population to SARS-CoV-2 infection [27]. Finally, a recent meta-analysis including sixteen studies highlighted that administering chemotherapy within the last thirty days before COVID-19 diagnosis may increase the risk of death in cancer patients (odds ratio: 1.85; 95% CI: 1.26–2.71) [28]. However, the higher severity of COVID-19 observed in patients with cancer is based on non-comparative retrospective studies, which may be potentially affected by unmeasured confounding and selection biases [30]. It should be noted that the majority of registries did not identify a detrimental effect of most cancer medical therapies, highlighting the importance of continuing treatment amidst a global healthcare emergency [25,28,31]. In fact, due to COVID-19 pandemic, cancer patients are experiencing significant delays in screening, diagnosis, treatment and surveillance, with consequent additional psychological distress [[31], [32], [33]]. As a consequence, an increased risk of cancer-related morbidity and mortality may occur, as well as major economic burden and a negative impact on clinical trials accrual [31,34,35]. Conversely, an accurate balance of risks and benefits is recommended for each treatment, with a particular priority reserved to curative settings [31].

5. Current evidence of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in cancer patients

Since cancer patients as a group have been shown to be at a higher risk of severe COVID-19, the development of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines may be crucial in this subpopulation [13]. Although IgG antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 infection does not seem to be different between healthy subjects and cancer patients [36], it is unknown whether an effective immunisation will be achieved in this subset of people. In this regard, data about how many individuals with history of cancer have been involved in all phase 3 vaccine RCTs are lacking [37]. Yet, eligibility of cancer patients can be deduced from inclusion and exclusion criteria of the trials, since some manufacturers made their full study protocols publicly available [37]. Most protocols excluded cancer patients on the basis of conditions that can be summarised in three categories (Table 1): (a) any prior history of cancer, (b) recent immunosuppressive therapies (e.g. chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunomodulating agents and systemic immunosuppressants) and (c) immunodeficiency and lack of stable disease, at the discretion of the investigator [37]. So, people at higher risk, like cancer patients, who should be sensibly prioritised to receive an approved vaccine, may be underrepresented in ongoing phase 3 clinical trials [37]. We therefore encourage manufacturers and investigators to provide real-time data about the characteristics of recruited participants, preferably including clearly identifiable subgroups, like cancer patients, with sample sizes large enough to determine safety and efficacy in these categories [37]. Besides, we envisage a prompt implementation of suitable registries for pharmacovigilance reporting, in order to monitor the effects of COVID-19 vaccines and immunisation rates in patients with cancer.

6. A call to action for the administration of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in cancer patients

Although evidence from RCTs is lacking, it is plausible that the safety and efficacy of vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 for cancer patients may be similar to those of patients without cancer, considering data extrapolation from other vaccines and the mechanism of action of most COVID-19 vaccines [38]. For example, considering anti-influenza vaccination, seroconversion and seroprotection appear to be lower in patients receiving chemotherapy than in the general population, but not in patients receiving single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) [39]. However, good tolerability and safety of anti-influenza vaccination in patients with cancer receiving ICI as well as in patients on cytotoxic therapy or targeted agents are suggested by retrospective evidence [40]. So, although enrolment of cancer patients in COVID-19 vaccination trials is limited, enough evidence supports anti-infective vaccination in general (except live-attenuated vaccines and replication-competent vector vaccines), even in patients under immunosuppressive therapy [41]. Therefore, we strongly encourage the healthcare authorities to prioritise vaccinations for cancer patients, even with active disease or receiving anticancer treatment. The time-point for vaccination should be discussed on a case-by-case basis (Table 2 ) [42]. When feasible, COVID-19 vaccine should be given at least 2 weeks before initiation of chemotherapy, immunosuppressive drugs or radiation therapy [42]. Alternatively, patients can be immunised about a week after the start of a chemotherapy cycle, according to limited data from patients with solid tumours receiving chemotherapy, in whom immunisation on day 4–5 of a cycle resulted more immunogenic than on day 16 [42]. In the case of allogeneic stem cell transplantation or cellular therapy, the vaccine should be administered around 3–6 months after the procedure, in the absence of graft-versus-host disease (Table 2) [30,43].

Table 2.

COVID-19 vaccination recommendations for cancer patients [43].

| Treatment/Cancer Type | Timingf |

|---|---|

| Solid tumour malignancies | |

| Receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy | When vaccine availablea,b |

| Targeted therapy | When vaccine available |

| Checkpoint inhibitors and other immunotherapy | When vaccine availablec |

| Radiation | When vaccine available |

| Major surgery | Separate date of surgery from vaccination by at least a few daysd |

| Haematopoietic Cell Transplantation/Cellular Therapy | |

| Allogeneic transplantation | At least 3 months post-HCT/cellular therapye |

| Autologous transplantation | |

| Cellular therapy (e.g. CAR-T cell) | |

| Haematologic malignancies | |

| Receiving intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy (e.g. cytarabine/anthracycline-based induction regimens for AML) | Delay until ANC recoverya |

| Marrow failure from disease and/or therapy expected to have limited or no recovery | When vaccine available |

| Long-term maintenance therapy (e.g. targeted agents for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or myeloproliferative neoplasms) | When vaccine availablea |

| Patients enrolled in clinical trials | |

| Patients receiving experimental cancer drugs or combinations | When vaccine available, after discussing each case with the trial sponsor |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; HCT, Haematopoietic Cell Transplantation; CAR-T cell, Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cell; GvHD, graft-versus-host disease; irAEs, immune-related adverse events.

Granulocytopenia does not significantly affect immunologic response to vaccination, thus it is not used for timing of vaccination in people with solid tumours, due to its short duration. Conversely, in the setting of profound immunosuppression for patients with haematologic malignancies, neutropenia is a surrogate marker for the recovery of immunocompetence to respond to vaccines.

Limited data available and consider the variability of specific chemotherapy regimens and intervals between cycles.

While there are no solid data on the timing of vaccine administration in this setting, the risk of exacerbated irAEs should be taken into account.

In order to allow for the correct attribution of perioperative symptoms (surgery versus vaccination). For surgeries inducing immunosuppression (e.g. complex surgeries and splenectomy), a wider window (e.g. 2 weeks) may be recommended.

GvHD and immunosuppressive regimens to treat GvHD can weaken immune responses to vaccination. Delay of vaccination until immunosuppressive therapy is reduced or based on immunophenotyping of T cell and B cell immunity can be considered. Patients on maintenance therapies (e.g. rituximab, Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors and Janus kinase inhibitors), may have attenuated response to vaccination.

COVID-19 vaccines should be prioritised over other vaccines, since data on dual vaccination is not yet available. NCCN recommends at least 14 days between COVID-19 vaccines and other approved vaccines.

Of note, patients who underwent B cell depletion in the previous 6 months may derive reduced protection [42]. Finally, patients enrolled in clinical trials with experimental cancer drugs or combinations should not be arbitrarily deprived of COVID-19 vaccination [30]; therefore, we invite clinical trial sponsors and investigators to allow for concurrent COVID-19 vaccines. Concurrently, psychological interventions could be useful to promote vaccinations and overcome possible vaccine hesitancy in the general and oncological populations [44].

7. Conclusions

As vaccination plans have been published worldwide in order to prioritise vaccine administration in different populations, the WHO considers the healthcare professionals and the elderly as first priorities, putting cancer patients in phase 2 [45]. On the basis of the evidence discussed, we strongly believe that healthcare authorities should prioritise vaccinations for cancer patients in current vaccination priority policies, even for those with active disease or receiving anticancer treatment, with time-point of administration agreed on a case-by-case basis [30,42]. In this regard, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) are advocating for cancer patients a high priority status, in hope of attenuating the consequences of the pandemic in this particularly vulnerable population and in line with the WHO principles of reducing deaths and disease burden worldwide.

Funding

This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chiara Corti: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Edoardo Crimini: Writing – review & editing. Paolo Tarantino: Writing – review & editing. Gabriella Pravettoni: Writing – review & editing. Alexander M.M. Eggermont: Writing – review & editing. Suzette Delaloge: Writing – review & editing. Giuseppe Curigliano: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: CC, EC, PT and GP have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. AMME served as consultant or advisor for Ellipses Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, ISA Pharmaceuticals, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sellas Life Sciences, Skyline Diagnostics, BioInvent, IO Biotech, CatalYm and Nektar, served on the speaker's bureau for MSD, BIOCAD, received travel funding from Bristol Myers Squibb and received honoraria from Ellipses Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, ISA Pharmaceuticals, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sellas Life Sciences, Skyline Diagnostics, BIOCAD, CatalYm, BioInvent, IO Biotech, Nektar, provided expert testimony for Novartis and has stock and other ownership interest with RiverD, Skyline Diagnostics, Theranovir, all outside the submitted work. SD served as consultant or advisor for AstraZeneca, received research funding from AstraZeneca (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst), Puma (Inst), Eli Lilly (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Sanofi (Inst) and received travel funding from Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Roche. GC served as consultant or advisor for Roche, Lilly and Bristol-Myers Squibb, served on the speaker's bureau for Roche, Pfizer and Lilly, received travel funding from Pfizer and Roche and received honoraria from Roche, Pfizer, Lilly, Novartis and SEAGEN, all outside the submitted work.

Acknowledgements

CC contributed to the literature search, conception and design of the article and drafted the first version of the manuscript. EC, PT and GP contributed to the literature search, design of the article and provided critical revisions of the manuscript. AMME and SD provided critical revisions of the manuscript. GC contributed to conception and design of the article and provided critical revisions of the manuscript. All the authors provided final approval to the submitted work.

References

- 1.WHO: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Numbers at a glance. https://bit.ly/3ckwmCD. [Accessed 22 January 2021].

- 2.Sterne J.A.C., Murthy S., Diaz J.V., Slutsky A.S., Villar J., Angus D.C., et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siemieniuk R.A., Bartoszko J.J., Ge L., Zeraatkar D., Izcovich A., Kum E., et al. Drug treatments for covid-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2980. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan H., Peto R., Henao-Restrepo A.M., Preziosi M.P., Sathiyamoorthy V., Abdool Karim Q., et al. Repurposed antiviral drugs for covid-19 – interim WHO solidarity trial results. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beigel J.H., Tomashek K.M., Dodd L.E., Mehta A.K., Zingman B.S., Kalil A.C., et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19 – final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piechotta V., Chai K.L., Valk S.J., Doree C., Monsef I., Wood E.M., et al. Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID-19: a living systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7:CD013600. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013600.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The RECOVERY trial chief investigators. "RECOVERY trial closes recruitment to convalescent plasma treatment for patients hospitalised with COVID-19". 14th January 2021. https://bit.ly/3sveWsu.

- 8.Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes monoclonal antibody for treatment of COVID-19. https://bit.ly/2McxI7e. [Accessed 22 January 2021].

- 9.Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes monoclonal antibodies for treatment of COVID-19. https://bit.ly/3a1l5Eu. [Accessed 22 January 2021].

- 10.Chen P., Nirula A., Heller B., Gottlieb R.L., Boscia J., Morris J., et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2029849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brivio E., Guiddi P., Scotto L., Giudice A.V., Pettini G., Busacchio D., et al. Patients living with breast cancer during the coronavirus pandemic: the role of family resilience, coping flexibility, and locus of control on affective responses. Front Psychol. 2021;11:3711. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masiero M., Mazzocco K., Harnois C., Cropley M., Pravettoni G. From individual to social trauma: sources of everyday trauma in Italy, the US and UK during the covid-19 pandemic. J Trauma Dissociation. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2020.1787296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuderer N.M., Choueiri T.K., Shah D.P., Shyr Y., Rubinstein S.M., Rivera D.R., et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.M., Wang W., Song Z.G., et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oran D.P., Topol E.J. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection : a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(5):362–367. doi: 10.7326/M20-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Docherty A.B., Harrison E.M., Green C.A., Hardwick H.E., Pius R., Norman L., et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ou X., Liu Y., Lei X., Li P., Mi D., Ren L., et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1620. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15562-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grifoni A., Weiskopf D., Ramirez S.I., Mateus J., Dan J.M., Moderbacher C.R., et al. Targets of T Cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181(7):1489–1501.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO draft landscape of Covid-19 candidate vaccines. https://bit.ly/2WPuad6. [Accessed 22 January 2021].

- 21.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williamson E.J., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K., Bacon S., Bates C., Morton C.E., et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elkrief A., Desilets A., Papneja N., Cvetkovic L., Groleau C., Lakehal Y.A., et al. High mortality among hospital-acquired COVID-19 infection in patients with cancer: a multicentre observational cohort study. Eur J Canc. 2020;139:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lièvre A., Turpin A., Ray-Coquard I., Le Malicot K., Thariat J., Ahle G., et al. Risk factors for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity and mortality among solid cancer patients and impact of the disease on anticancer treatment: a French nationwide cohort study (GCO-002 CACOVID-19) Eur J Canc. 2020;141:62–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Joode K., Dumoulin D.W., Tol J., Westgeest H.M., Beerepoot L.V., van den Berkmortel F.W.P.J., et al. Dutch oncology COVID-19 consortium: outcome of COVID-19 in patients with cancer in a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Canc. 2020;141:171–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saini K.S., Tagliamento M., Lambertini M., McNally R., Romano M., Leone M., et al. Mortality in patients with cancer and coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and pooled analysis of 52 studies. Eur J Canc. 2020;139:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yekedüz E., Utkan G., Ürün Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis: the effect of active cancer treatment on severity of COVID-19. Eur J Canc. 2020;141:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garassino M.C., Whisenant J.G., Huang L.C., Trama A., Torri V., Agustoni F., et al. COVID-19 in patients with thoracic malignancies (TERAVOLT): first results of an international, registry-based, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):914–922. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30314-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garassino MC, Giesen N, Grivas P, Jordan K, Lucibello F, Mir O, et al.: ESMO Statements for Vaccination against COVID-19 in patients with cancer. https://bit.ly/3swNx9G. [Accessed 16 January 2020].

- 31.Lambertini M., Toss A., Passaro A., Criscitiello C., Cremolini C., Cardone C., et al. Cancer care during the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy: young oncologists' perspective. ESMO Open. 2020;5(2) doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazzocco K., Masiero M., Carriero M.C., Pravettoni G. The role of emotions in cancer patients' decision-making. Ecancermedicalscience. 2019;13:914. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2019.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnaboldi P., Lucchiari C., Santoro L., Sangalli C., Luini A., Pravettoni G. PTSD symptoms as a consequence of breast cancer diagnosis: clinical implications. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:392. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleury M.E., Farner A.M., Unger J.M. Association of the COVID-19 outbreak with patient willingness to enroll in cancer clinical trials. JAMA Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.5748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarantino P., Trapani D., Curigliano G. Conducting phase 1 cancer clinical trials during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-related disease pandemic. Eur J Canc. 2020;132:8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marra A., Generali D.G., Zagami P., Gandini S., Cervoni V., Venturini S., et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody response in patients with cancer and oncology healthcare workers: a multicenter, prospective study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(supplement 4):S1206. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.2318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corti C., Curigliano G. Commentary: SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward E.M., Flowers C.R., Gansler T., Omer S.B., Bednarczyk R.A. The importance of immunization in cancer prevention, treatment, and survivorship. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(5):398–410. doi: 10.3322/caac.21407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bayle A., Khettab M., Lucibello F., Chamseddine A.N., Goldschmidt V., Perret A., et al. Immunogenicity and safety of influenza vaccination in cancer patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 or PD-L1. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(7):959–961. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rousseau B., Loulergue P., Mir O., Krivine A., Kotti S., Viel E., et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the influenza A H1N1v 2009 vaccine in cancer patients treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy and/or targeted therapy: the VACANCE study. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(2):450–457. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rieger C.T., Liss B., Mellinghoff S., Buchheidt D., Cornely O.A., Egerer G., et al. Anti-infective vaccination strategies in patients with hematologic malignancies or solid tumors-guideline of the infectious diseases working party (AGIHO) of the German Society for hematology and medical oncology (DGHO) Ann Oncol. 2018;29(6):1354–1365. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubin L.G., Levin M.J., Ljungman P., Davies E.G., Avery R., Tomblyn M., et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):e44–100. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Preliminary Recommendations of the NCCN COVID-19 vaccination advisory committee. Version 1.0 1/22/2021. https://bit.ly/3qN6uTD. [Accessed 22 January 2021].

- 44.Brivio E., Oliveri S., Pravettoni G. Empowering communication in emergency contexts: reflections from the Italian coronavirus outbreak. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(5):849–851. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.WHO SAGE values framework for the allocation and prioritization of COVID-19 vaccination, 14 September 2020. World Health Organization. https://bit.ly/35NPC7m. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.