Abstract

Background: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) research increasingly requires healthy individuals willing to undergo genetic testing. Objective: This study seeks to: 1) Describe older adults’ beliefs about AD genetic testing, worry about AD, and fear of AD stigma, and 2) Explore how these constructs relate to research participation. Methods: Surveys were sent to participants active in AD-observational research and those that were not. Three measures of research participation were explored: 1) Being a current research participant, 2) Self-report of clinical trial participation, and 3) Expressing genetic registry interest. Results: The majority of the 502 respondents perceived greater benefit than risk associated with AD genetic testing. AD worry and perceptions of AD stigma were low. Higher levels of AD worry and lower perceptions of AD stigma were associated with being a current AD research volunteer. AD worry and stigma were unrelated to clinical trial participation or genetic registry interest; these research participation measures were associated with AD genetic testing benefit. Conclusions: Beliefs about AD genetic testing, AD worry, and AD stigma are related to research participation, but relationships vary based on the research participation investigated. Future work should identify how these findings can inform outreach and recruitment efforts.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Genetic research, Research participation, Motivation

Introduction

In the United States someone is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) every 65 seconds1. In the absence of any scientific breakthroughs, the number of individuals living with AD is expected to reach roughly 16 million by 20502. The 2012 National Plan to Address AD set the goal of preventing and effectively treating AD by 20253.

In recent years, an increasing number of AD clinical trials have been designed as prevention trials, focusing on the potential to prevent rather than slow down or treat the disease4. A key step toward achieving this goal is recruiting an adequate number of healthy asymptomatic participants that have high genetic and/or lifestyle risks for the future development of AD. Barriers to participation include: privacy concerns related to potential genetic and/or biomarker testing in otherwise healthy individuals, potential medication side effects, time-consuming and sometimes invasive research procedures, and long durations of study involvement. These concrete barriers are in contrast to more elusive benefits, e.g. the potential to ward of a disease that may never be experienced regardless of research participation and the ability to benefit scientific advances and future generations5. Many healthy individuals lack the motivation to engage in such research. Accordingly, participant recruitment is a major rate-limiting factor delaying preventive therapy research for AD6.

Various recruitment strategies are being explored, including the use of registries with healthy volunteers. Many of these approaches are costly and time consuming, and response rates are often disappointingly low. For example, in the Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT), efforts to identify participants included roughly 3.5 million mailings. This massive undertaking resulted in approximately 0.08% enrollment7. Efforts to better understand potential participants’ beliefs and motivators are clearly needed to better guide recruitment strategies for research engagement. One study that surveyed AD clinical trial participants found that the potential to help themselves or a loved one and the potential to help others in the future were both important motivators, whereas monetary rewards, free healthcare, and making others happy were infrequently motivators8. However, a more in-depth real-world understanding of beliefs and motivators for AD prevention research participation is needed.

The purpose of this study was twofold: 1) To explore beliefs about AD genetic testing and the degree to which individuals worry about AD or view AD as a stigmatized condition. 2) To better understand how these beliefs, worries, and stigma concerns relate to real-world research engagement decisions. We hypothesized that those who saw greater benefit in AD genetic testing, those who were more concerned about AD, and those with lower perceptions of AD stigma would demonstrate a greater likelihood of being engaged in all forms of AD research measured than those who saw fewer benefits, those who were less concerned about AD, or those with high stigma perceptions. This study was part of a larger project exploring understanding and opinions of genetic research on AD9.

Methods

Participants

We surveyed two groups. First, volunteers (n=594) enrolled in the University of Kentucky Alzheimer’s Disease Center (UKADC) longitudinal cohort with Clinical Dementia Ratings global scores of 0 or 0.5, representing no or questionable memory and thinking problems, were surveyed10,11. The UKADC is an observational program that involves extensive cognitive tests and blood donation, but no intervention. In addition, the UKADC manages a list from 2010 of registered voters in Fayette County Kentucky who indicated a willingness to be contacted for aging-related research not specific to AD. This second group was included to identify individuals who were age eligible for AD research, but who are not involved. After the UKADC list was generated, summary statistics on age, sex, race, and educational attainment were computed. Using those results, the Voter Registration List (VRL) was randomly sampled (n=608) to generate an age and gender matched group of community-dwelling, AD-research-naïve subjects (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Description

| All Respondents (n=502) | UKADC (n=329) | VRL (n=173) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 78.76 (6.64) | 78.49 (7.23) | 79.28 (5.30) | 0.21 |

| Sex | 0.19 | |||

| Male | 212 (42.23) | 132 (40.12) | 80 (46.24) | |

| Female | 290 (57.77) | 197 (59.88) | 93 (53.76) | |

| Race | 0.88 | |||

| Caucasian | 457 (91.04) | 300 (91.19) | 157 (90.75) | |

| Non-Caucasian | 45 (6.37) | 29 (6.99) | 16 (5.20) | |

| Education | 0.02 | |||

| No College | 159 (31.67) | 90 (27.36) | 69 (39.88) | |

| College | 343 (68.33) | 239 (72.64) | 104 (60.12) | |

| Marital Status | 0.90 | |||

| Never Married | 17 (3.39) | 13 (3.95) | 4 (2.31) | |

| Married | 293 (58.37) | 193 (58.66) | 100 (57.80) | |

| Divorced/Separated | 58 (11.55) | 40 (12.16) | 18 (10.40) | |

| Widowed | 132 (26.29) | 83 (25.23) | 49 (28.32) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.40) | 0 | 2 (1.16) |

Instrument

Surveys were designed to measure perspectives related to AD genetic research, including benefits and limitations of AD genetic testing, AD worry, and fear of AD stigma. The questions on the perceived benefits (5 questions) and limitations (6 questions) of AD genetic testing were adapted from an existing instrument that looked at perceived benefits of genetic testing in the context of BRCA1 testing for breast cancer12. Participants were asked to check how important each potential benefit or risk was to them, with the response options of not at all important, somewhat important, or very important. The AD worry scale (7 questions) was modified from a cancer worry scale13. The AD worry questions asked respondents to rate how much they worry about AD, the possibility of developing AD and how often these worries affect them. Response options ranged from never to almost always using a five-point Likert scale. The section on fear of AD stigma (3 questions) was modified from a fear of stigma scale initially used in the context of cystic fibrosis14. Basic demographics such as age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, and marital status were also collected.

Research participation was measured in three ways: 1) Membership in the UKADC group (indicator of active observational AD research participation), 2) Self-report of having ever participated in a clinical trial (e.g. interventional research), 3) For VRL participants only, active follow-up regarding the opportunity to participate in a genetic registry. For VRL participants, the survey included a brief blurb about the opportunity to participate in a genetic registry. Individuals were instructed to contact the study investigator to learn more if interested. This question was not included in the UKADC surveys because these respondents already had the opportunity to provide genetic information through their existing research participation.

Analysis

Summary scores for perceived benefits and perceived limitation of genetic testing for AD susceptibility were calculated according to Lerman and colleagues (1997) methods for the BRCA1 Testing by summing participant responses (not at all important =1, somewhat important=2, very important=3). The AD worry scale items were scored similarly to the cancer worry scale13 and summed to create a summary worry score (1 for never, 2 for seldom, 3 for sometimes, 4 for often, and 5 for almost always) such that higher scores indicate greater AD worry. The Fear of Stigma items were scored similarly to the cystic fibrosis instrument14, where 1 denotes “strongly agree” and 4 denotes “strongly disagree”, so higher scores indicate less fear of stigma. Unanswered questions were not scored. Summary scores were then calculated by adding the scores for each item and dividing by the number of non-missing items. Descriptive statistics were used to explore perspectives on beliefs and limitations of genetic testing, AD worry, and fear of stigma. Generalized linear models were used to look for significant relationships between the three constructs examined (beliefs and limitations of genetic testing, AD worry, and fear of stigma) and the three forms of research participation measures assessed, controlling for age, gender, education, and race.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board.

Results

Respondents

A total of 502 surveys were received, including 329 UKADC participants and 173 VRL participants; after removing individuals for whom the survey got returned or were recently deceased, this represented response rates of 56.7% and 34.7% respectively. Minority individuals were less likely to respond than Caucasian individuals in both the UKADC (8.8% vs. 17.9%, p=.04) and the VRL (9.2% vs. 17.0%, p=.048). In addition, UKADC respondents had higher education (71.7% college education vs. 58.2%, p=.001) than UKADC non-respondents. VRL respondents were younger than VRL non-respondents (mean age = 79.3 vs. 80.7, p=.007). No other differences were observed between respondents and non-respondents in either group.

The mean age of the overall sample was 78.8 years; 57.8% were female, and 58.6% were currently married (Table 1). Participants were highly educated, 68.3% had at least a college degree. Most were Caucasian. The UKADC group was significantly more likely to have a college education or higher (72.4%) than the VRL group (60.5%, p=.023).

Descriptive findings

Genetic testing beliefs.

Based on summary scores for perceived benefits and limitations of genetic testing, overall individuals perceived greater benefit (mean = 12.43, SD = 2.49) than limitation (mean=11.04, SD=2.68) of AD genetic testing, despite having more limitation items than benefit items. Endorsement that each of the potential benefits of genetic testing were somewhat or very important ranged from 87.87% to 96.16%. The perceived benefits that individuals viewed as the most important were to plan for the future and make long-term care decisions, whereas reassurance was the perceived benefit of genetic testing that was seen as least important. Endorsement that each of the potential limitations of genetic testing were somewhat or very important ranged from 26.38% to 86.47%. The greatest perceived limitation or risk of genetic testing was concerns about the effect on family members followed by a belief that AD cannot be prevented even if one is aware of their genetic risk. Participants were least concerned with trust in modern medicine and an inability to handle the testing emotionally (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Perceived benefits and limitations of genetic testing for AD susceptibility

* Missing values were excluded

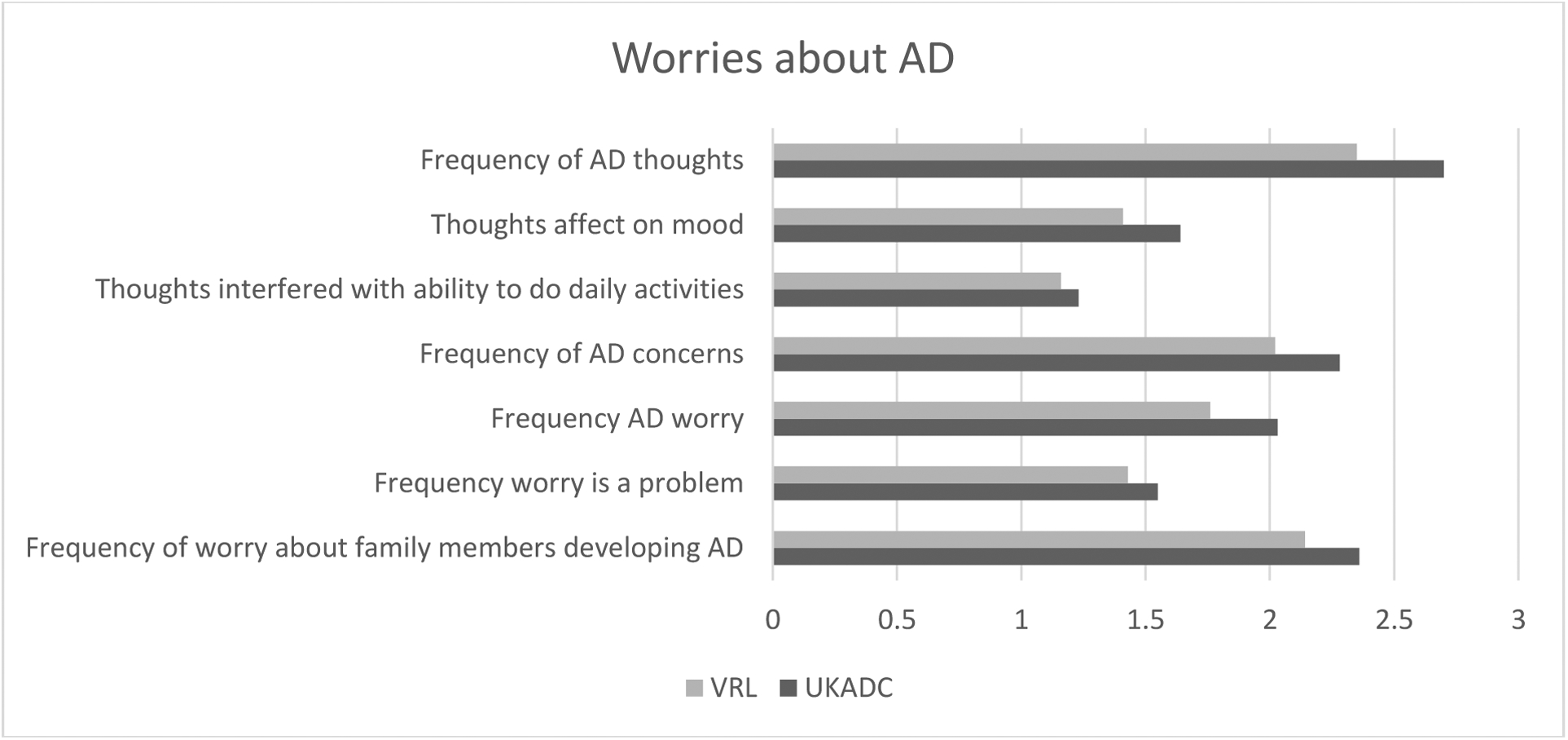

AD worry.

In general, AD worry was low, infrequent, and rarely interfered with mood or daily activities. The mean summary score for AD worry was relatively low (mean=13.35, SD = 4.21). A score of 14 would correspond to responding “seldom” across items. While rare, thoughts about getting AD (mean=2.59, SD = .93), frequency of concerns about getting AD (mean=2.20, SD = .85), worries about developing AD (mean=1.95, SD = .85), and worry about family members developing AD (mean=2.29, SD = 1.06), were slightly higher than the extent to which AD worries affected mood (mean=1.56, SD = .74), AD thoughts interfered with daily activities (mean=1.20, SD = .50) or AD worry was problematic for respondents (mean=1.51, SD = .72).

Fear of stigma.

Fear of stigma was fairly low. Only about 30% indicated they would feel less healthy if they were found to have a gene that increased risk for AD. Respondents rarely endorsed concerns that they would feel labelled or singled out (13%) or worries that results may not stay confidential (20%).

Clinical trial participation.

Respondents were fairly evenly split between those who reported having participated in a clinical trial (42.4%) and those that reported having never participated in a clinical trial (41.5%), with the remaining respondents (11.5%) reporting being unsure. For this analysis, the unsure participants are grouped with the non-participants.

Genetic registry interest.

Follow-up regarding genetic registry participation was low; only 28 VRL respondents (16.5%) followed up to get more information about the genetic registry.

Relationships between AD beliefs, worry, stigma, and research participation measures

Predictors of UKADC participation.

Contrary to expectations, there were no significant differences between UKADC and VRL participants when looking at perceived benefits or limitations of genetic testing for AD susceptibility when controlling for age, gender, education, and race. However, consistent with predictions, UKADC participants reported significantly more worry (13.88) about AD than VRL participants (12.29), β=1.54, p<.001, higher scores reflect greater worry (See Figure 2). In addition, UKADC respondents reported significantly less fear of stigma (9.06) than VRL respondents (8.78), β=0.29, p=.04 when controlling for age, gender, education, and race, with higher scores indicating less fear of stigma (See Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Worries about AD

Figure 3.

AD stigma

Predictors of clinical trial participation.

UKADC participants were significantly more likely (49.5%) than VRL participants (30.6%) to report having participated in a clinical trial, p<.001. This difference remained significant event after controlling for age, race, gender, and education, β=0.20, p<.001 Of the constructs examined, perceived benefit was the only construct where there were significant differences between those who reported participating in a clinical trial and those who reported not participating or not being sure. Controlling for age, race, gender, education, and respondent group, this relationship was in the predicted direction; individuals who reported participating in a clinical trial perceived greater benefits (mean = 12.97) of genetic testing than those who did not report (e.g. no and not sure responses) participating in a clinical trial (mean = 12.05), β= −.925, p<.001.

Predictors of genetic registry interest.

We examined perceived benefits and limitations, AD worry, and fear of stigma to explore differences between the VRL respondents who followed up about the genetic registry and those that did not. Consistent with our hypothesis, individuals who followed up to engage in the genetic registry perceived greater benefits of AD genetic testing, (mean=13.39) than those who did not follow up (mean =12.15), controlling for age, race, education, and gender, β= −1.256, p = .017. There were no significant differences for the other constructs.

Discussion

This study explored three constructs: perceived benefits and limitations of AD genetic testing, AD worry, and AD stigma. Results suggest that individuals see many benefits to participating in AD genetic testing. Individuals rate making long-term care decisions and planning for the future as the most important reasons to participate in AD genetic testing. This is in line with previous research that has shown that advanced planning is one motivation for undergoing predictive testing for AD15. Researchers may be able to capitalize on this motivation by providing resources for advance care planning during study participation. The greatest perceived limitation or risk of genetic testing for AD were concerns about the effect on family members and friends, followed by a belief that you cannot prevent AD. A more explicit focus on advanced care planning may help to allay fears about potential burden to family members and provide a semblance of control. Perceptions of inevitability in regard to disease expression and progression may also be addressable through better public education on risk information and actions that individuals can take to promote brain health. Perhaps, with increased knowledge of lifestyle behaviors that can help reduce AD risk and ways to maximize quality of life for those with AD, participants would be less hesitant to learn their risk status.

Worry over AD was relatively low among respondents. The lower overall worry was in contrast to previous research suggesting that worry for AD is high among the public16. One potential explanation for the relatively low level of AD worry in the present study may be the high age of participants, as some research suggests that individuals may have less AD worry after age 7017. The higher level of worry noted among UKADC participants than among VRL participants, may reflect initial motivations for involvement5 or possibly heightened awareness of cognitive performance due to the memory testing involved in UKADC research participation.

Fear of stigma was also relatively low, which is in line with previous research that AD, even pre-clinical AD, is generally not associated with significant stigma18. UKADC respondents had less fear of stigma than VRL respondents. Perhaps individuals with lower perceptions of stigma may be less hesitant to engage in research. Alternately, the lower stigma among UKADC respondents may reflect a lessening of stigma among individuals who are involved in a setting where AD is not stigmatized.

This study also sought to identify relationships between these three constructs and real-world measures of research participation. Findings suggest these that predictors of participation vary based on the aspects of research participation examined. Benefits of AD genetic testing were significantly related to clinical trial participation and registry interest; worry and stigma were not significantly related to these measures of research involvement. In contrast, worry and stigma, but not perceived benefits, were associated with being an active UKADC research participant. This suggests that approaches to reach out for different aspects of research may require different, targeted, strategies. In general, however, highlighting potential benefits of participation, trying to reduce stigma and encourage attention to brain health, and presenting research as a way to address AD worry (via disease monitoring or involvement in interventional research), all deserve further study as efforts that may promote future research participation.

This study has a number of limitations. First, respondents may have been more positively inclined towards AD research participation than non-respondents; accordingly, results may be less generalizable to those who are less inclined to participate. In addition, clinical trial participation relied on self-report and therefore was limited by participant recall; further, no definition of clinical trial was provided, which may have led to misreporting of clinical trial participation. The low level of follow-up regarding genetic registry interest (only 16.5%) was somewhat surprising; genetic registry participation may present additional barriers than other forms of AD research involvement, e.g. participation may be more abstract and offer less tangible benefit. In addition, this study was cross-sectional and therefore causality is unclear. Further, while we controlled for education, it is possible that differences in education levels between the two groups may also relate to additional socioeconomic confounds (e.g. income or occupation) that were unmeasured and could potentially account for some of the differences in attitudes observed. Future research will be needed to tease out the role that these variables may play. Despite these limitations, this study provides a broad overview of thoughts and beliefs that may relate to AD genetic research participation in the context of real-world research engagement. In the future, findings from this study may inform the design of recruitment materials that might enhance AD genetic research participation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to all of our survey respondents who took the time to complete and return our survey. Thank you also to the following students who assisted with data entry: Hannah Schuler, Megan Higgins, Ying Liu, and Holden Huffman. Thank you to Dr. Erin Abner for her statistical advice.

FUNDING

The project described was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR001998, and the National Institute on Aging P30 AG028383. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: None declared.

References:

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2019;15(3):321–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer’s Association. 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2016;12(4):459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. National Plans to Address Alzheimer’s Disease. 2016; https://aspe.hhs.gov/national-plans-address-alzheimers-disease. Accessed February 21, 2017.

- 4.Romero HR, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Gwyther LP, et al. Community engagement in diverse populations for Alzheimer’s disease prevention trials. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2014;28(3):269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardach SH, Parsons K, Gibson A, Jicha GA. “From Victimhood to Warriors”: Super-researchers’ Insights Into Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Trial Participation Motivations. The Gerontologist. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khachaturian ZS, Barnes D, Einstein R, et al. Developing a national strategy to prevent dementia: Leon Thal Symposium 2009. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2010;6(2):89–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Group AR. Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial: design, methods, and baseline results. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2009;5(2):93–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardach SH, Holmes SD, Jicha GA. Motivators for Alzheimer’s disease clinical trial participation. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent S, Bardach SH, Zhang X, Abner EL, Grill JD, Jicha GA. Public Understanding and Opinions regarding Genetic Research on Alzheimer’s Disease. Public health genomics. 2018;21(5–6):228–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitt FA, Nelson PT, Abner E, et al. University of Kentucky Sanders-Brown healthy brain aging volunteers: donor characteristics, procedures and neuropathology. Current Alzheimer research. 2012;9(6):724–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lerman C, Biesecker B, Benkendorf JL, et al. Controlled trial of pretest education approaches to enhance informed decision-making for BRCA1 gene testing. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1997;89(2):148–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK, Jepson C, Brody D, Boyce A. Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 1991;10(4):259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tambor ES, Bernhardt BA, Chase GA, et al. Offering cystic fibrosis carrier screening to an HMO population: factors associated with utilization. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1994;55(4):626–637. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts SJ, LaRusse SA, Katzen H, et al. Reasons for seeking genetic susceptibility testing among first-degree relatives of people with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2003;17(2):86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cutler SJ. Worries about getting Alzheimer’s: who’s concerned? American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias®. 2015;30(6):591–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cutler SJ, Brăgaru C. Long-term and short-term predictors of worries about getting Alzheimer’s disease. European journal of ageing. 2015;12(4):341–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson R, Harkins K, Cary M, Sankar P, Karlawish J. The relative contributions of disease label and disease prognosis to Alzheimer’s stigma: A vignette-based experiment. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;143:117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]