STRUCTURED ABSTRACT

Background:

Dementia with Lewy body (DLB) diagnostic criteria define “indicative” and “supportive” biomarkers, but clinical practice patterns are unknown.

Methods:

An anonymous survey querying clinical use of diagnostic tests/biomarkers was sent to 38 center of excellence investigators. The survey included “indicative” biomarkers (dopamine transporter [DAT] scan, myocardial scintigraphy, polysomnography), “supportive” biomarkers (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), positron emission tomography [PET] or single-photon emission computed tomography [SPECT] perfusion/metabolism scans, quantitative electroencephalography), and other diagnostic tests (neuropsychological testing, cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] analysis, genetics). Responses were analyzed descriptively.

Results:

Of the 22 respondents (58%), all reported the capability to perform neuropsychological testing, MRI, polysomnography, DAT scans, PET/SPECT scans, and CSF analysis; 96% could order genetic testing. Neuropsychological testing and MRI were the most commonly ordered tests. Diagnostic testing beyond MRI and neuropsychological testing was most helpful in the context of “possible” DLB and mild cognitive impairment and to assist with differential diagnosis. Myocardial scintigraphy and electroencephalograpy use were rare.

Conclusions and Relevance:

Neuropsychological testing and MRI remain the most widely-used diagnostic tests by DLB specialists. Other tests – particularly indicative biomarkers – are employed only selectively. Research is needed to validate existing potential DLB biomarkers, develop new biomarkers, and investigate mechanisms to improve DLB diagnosis.

Keywords: Dementia with Lewy bodies, Lewy body disease [MeSH term], diagnosis [MeSH term], biomarkers [MeSH term], diagnostic tests, routine [MeSH term]

INTRODUCTION

Biomarkers are playing an increasing role in the etiologic diagnosis of dementia, both in Alzheimer disease (AD) and AD-related dementias (ADRDs) [1]. To date, no biomarkers reliably identify the synuclein pathology underlying dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Biomarkers can still be helpful in DLB diagnosis by demonstrating findings consistent with synuclein pathology (e.g. REM sleep without atonia) or excluding findings more suggestive of another pathology (e.g. AD).

The fourth consensus criteria for the diagnosis of DLB designated two types of biomarkers based on available evidence and diagnostic specificity: “indicative” or “supportive” [2]. Indicative biomarkers included (1) reduced basal ganglia dopamine transporter (DAT) uptake demonstrated by positron emission tomography (PET) or single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), (2) reduced uptake on 123iodine metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy, and (3) confirmation of REM sleep without atonia on polysomnography (PSG). Indicative biomarkers can support a diagnosis of “probable” or “possible” DLB [2].

Supportive biomarkers do not play a formal role in DLB diagnosis. However, biomarkers consistent with DLB can strengthen the overall diagnostic evaluation. Supportive DLB biomarkers are: (1) relative preservation of medial temporal lobe structures on structural imaging (e.g. magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), (2) generalized low uptake on SPECT/PET perfusion/metabolism scans, reduced occipital activity, and/or the posterior cingulate island sign on fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET, and (3) prominent posterior slow-wave activity with periodic fluctuations in the pre-alpha/theta range on quantitative electroencephalography (EEG) [2]. Amyloid PET is unlikely to distinguish between DLB and AD as amyloid deposition is common in both disorders. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) results may help predict the presence of AD pathology (e.g., amyloid, tau) or the expected rate of cognitive decline, but at the present time, do not inform the presence of underlying Lewy body pathology [2]. Thus, traditional AD biomarkers do not exclude a diagnosis of DLB but may have prognostic implications.

While biomarkers can help achieve a “probable” or “possible” DLB diagnosis, diagnosis can also rely on clinical features alone [2]. Some U.S. insurers cover DAT-SPECT for the indication of clinically uncertain DLB [3], while others describe it as “investigational” for the indication of distinguishing DLB from AD and do not provide coverage [4]. In the U.S., there are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved MIBG compounds for diagnosis and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors, but cardiac [5] and neurologic indications are off-label. For more widely available diagnostic tests (e.g. MRI, PSG, neuropsychological testing), specialists’ discussions suggest that practices vary. Thus, we aimed to investigate diagnostic test practices of DLB specialists to identify current approaches.

METHODS

The study utilized a survey investigating diagnostic test use in clinical settings by investigators at Lewy Body Dementia Association (LBDA) Research Centers of Excellence. The University of Florida institutional review board identified the study as exempt (IRB202000330) with the use of a certificate of confidentiality to preserve participant anonymity.

The survey used REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Florida [6, 7]. One investigator drafted the survey and three additional investigators and an LBDA staff member revised it. After describing the survey purpose, principal investigator, and expected completion time, the final survey asked identical questions for 9 diagnostic tests/biomarkers including optional multiple choice and write-in responses (Supplemental File 1). Each online survey page contained the questions for a single diagnostic test (total pages: 10). Respondent characteristics were not collected. Written informed consent was not required as the anonymous study was considered exempt. One investigator and research assistant completed pilot testing.

The online survey link was distributed to the 38 investigators associated with the 25 LBDA Research Center of Excellence sites via email on 4/1/2020. Links were specific to each email recipient. Individuals who did not complete the survey received reminders at 2 and 4 weeks. No incentives were used.

Multiple choice responses were analyzed descriptively using percentages. Investigators grouped write-in responses sharing matching themes and reported these descriptively. Microsoft Excel® 2016 tables were used to organize and analyze data. Quantitative and qualitative responses were synthesized into an algorithm reflecting respondent practices. The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys checklist [8] guided study reporting (Supplemental File 2).

RESULTS

Twenty-three site investigators accessed the survey (60.5%) and 22 (57.9%) responded to questions. The 22 respondents completed all quantitative questions and almost all provided write-in responses for each section. All sites reported the capability to perform neuropsychological testing, MRI, PSG, DAT scan, SPECT/PET scans, and CSF analysis. Most (21/22, 95.5%) reported the ability to order genetic testing. Ten (45.5%) respondents could perform local MIBG scintigraphy, 6 (27.3%) reported no such capability, and 6 (27.3%) were unsure. Nine (40.9%) investigators could do quantitative EEG, 9 (40.9%) reported being unable to do it, and 4 (18.2%) were unsure.

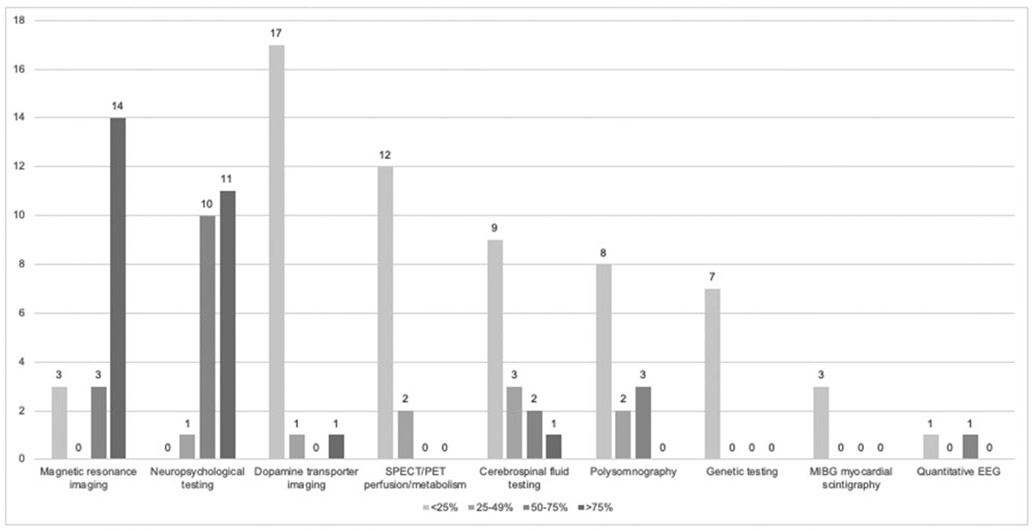

All investigators used neuropsychological testing at least sometimes. Over 85% of investigators reported “ever” using MRI or DAT imaging for DLB diagnosis (Table 1). When considering frequency of use, the most commonly used (i.e., >75% of the time) diagnostic tests were MRI and neuropsychological testing (Figure 1). Numerous biomarkers were used by most investigators, but infrequently (Figure 1). Reasons underlying investigator test use are summarized below.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Tests “Ever” Used Clinically by Experts for Diagnosing Dementia with Lewy Bodies

| Test | Number (%) of Investigators Reporting Ever Using the Test for DLB Diagnosis (n=22) |

|---|---|

| Neuropsychological testing | 22 (100%) |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 20 (90.9%) |

| Dopamine transporter imaging | 19 (86.4%) |

| Cerebrospinal fluid testing | 15 (68.2%) |

| SPECT/PET perfusion/metabolism | 14 (63.6%) |

| Polysomnography | 13 (59.1%) |

| Genetic testing | 7 (31.8%) |

| MIBG myocardial scintigraphy | 3 (13.6%) |

| Quantitative EEG | 2 (9.1%) |

DLB: Dementia with Lewy bodies, SPECT: single-photon emission computed tomography, PET: positron emission tomography, MIBG: metaiodobenzylguanidine, EEG: electroencephalography

Figure 1. Frequency of DLB Diagnostic Test Use by Specialists Who Use the Tests.

The figure displays the frequency that specialists reported using each of the nine surveyed diagnostic tests/biomarkers (total survey n=22, but only specialists indicating that they use the test were queried regarding frequency of use).

Neuropsychological testing

All investigators reported using neuropsychological testing at least sometimes (Table 1). In the write-in responses, several investigators indicated that neuropsychological testing is standard of care unless individuals have severe dementia compromising testing. One investigator noted that results are most helpful when neuropsychological testing is performed at academic centers (versus community settings). Nine reported that neuropsychological testing is most helpful to confirm that the domain impairment pattern is consistent with DLB and to distinguish suspected DLB from other pathologies (e.g. AD). Investigators also reported using neuropsychological testing to define the degree of impairment (n=3), assess early stages and distinguish mild cognitive impairment (MCI) from dementia (n=2), establish the patient’s baseline to allow longitudinal assessments (n=2), identify functional limitations (n=2), better assess individuals with high educational attainment (n=2), and inform counseling (e.g. regarding prognosis, safety, driving) (n=2).

Magnetic resonance imaging

Of the 20 investigators who use MRI, nine considered it standard of care or used it routinely as part of a general dementia evaluation. Ten investigators described using MRI to look for evidence of alternate or co-existing pathology such as vascular disease, AD, normal pressure hydrocephalus, atypical parkinsonism (e.g. multiple system atrophy) or reversible causes of dementia. Investigators described a need for coronal and susceptibility weighted images in addition to axial slices. The two investigators who reported not using MRI said that they don’t order it because it is non-specific.

DAT scan

Of the 19 investigators who order DAT scans, use is infrequent (Figure 1). The investigator who uses DAT scans >75% of the time reported using it for clinical and research purposes. Investigators reported that DAT scans are most helpful in to differentiate DLB from other conditions (n=7), when parkinsonism is mild or absent (n=6), in early or MCI stages (n=5), when there are atypical or conflicting presentations (n=3), to exclude secondary parkinsonism (e.g. due to medication, vascular disease) (n=3), and to help fulfill diagnostic criteria (n=3). Investigators noted numerous limitations to clinical DAT scan use, including false positive and false negative results, lack of quantitative interpretation, expense, and lacking research on use in clinical settings. The three investigators who do not use DAT scan in diagnosing DLB stated it was not needed, usually because the individuals they evaluate have evidence of parkinsonism and thus DAT scans were not felt to be clinically helpful. Some investigators using DAT in select circumstances also mentioned its redundancy in the presence of motor symptoms.

Cerebrospinal fluid testing

The most common reason investigators reported using CSF was to differentiate DLB from other suspected dementia pathologies or to look for evidence of co-pathology, particularly AD (n=13). Four respondents described using CSF in the context of rapidly progressive dementia symptoms. One investigator mentioned potential value as a prognostic marker. Reasons that investigators do not use CSF testing for DLB diagnosis included the opinion that CSF analysis is unhelpful or unnecessary since there are no CSF synuclein biomarkers and the lack of a good mechanism for obtaining LPs in clinic. Some of these investigators mentioned that they use CSF in the context of evaluating MCI or in research settings. Four investigators felt CSF currently has more of a role in research than for routine clinical care.

SPECT/PET perfusion/metabolism

Multiple investigators stated that PET and SPECT are rarely used in practice, consistent with the quantitative responses (Figure 1). Of the investigators who sometimes use PET or SPECT, the most commonly reported reasons were to help differential diagnosis (n=8) or evaluate atypical presentations (n=2). One investigator used PET/SPECT in the setting of MCI. Reported limitations included cost, lack of insurance coverage, lack of classic imaging findings, interpretation difficulties, and need for additional research regarding PET/SPECT’s role in DLB. The eight investigators who reported never using PET or SPECT described various reasons, primarily feeling it is not helpful or reasonably sensitive/specific (n=5). Several investigators mentioned practice-related reasons, including working at institution that considers these scans research-only or lack of confidence in radiologists’ expertise.

Polysomnography

The most commonly reported reason for ordering PSG was to confirm the presence of REM sleep without atonia (n=9), particularly in the setting of issues making the diagnosis less certain (vague descriptions, presence of post-traumatic stress disorder, question of a non-REM parasomnia or confusional arousal). Four investigators used PSG for reasons other than evaluating for REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), including fatigue or obstructive sleep apnea concerns. Single investigators described using PSG to look for RBD in asymptomatic patients, in atypical dementia contexts, or as a mechanism to screen “for risk.” PSG limitations included patients not entering REM sleep during the study and PSG interpretation performed by physicians not focused on assessing REM sleep behaviors. One investigator noted that PSG studies should be performed using video sync to match visualized behaviors and PSG data and interpreted by knowledgeable sleep neurologists. Reasons that investigators do not use PSG for DLB diagnosis included: it is not needed (n=3), historical symptoms can suggest RBD without PSG (n=3), limitations in testing/reporting (trouble accessing sleep studies, perception that PSG is not sensitive/specific, reporting does not comment on findings other than obstructive sleep apnea) (n=3), or sleep center referrals are used for other reasons or have occurred prior to the DLB evaluation (n=3). Three investigators who use PSG also noted that screening questionnaires may be sufficient to diagnose RBD in many circumstances.

Genetic testing

Investigators who report ordering genetic testing clinically use it primarily to assess individuals with suspected DLB with a strong family history, particularly in young-onset dementia (n=7). Multiple investigators mentioned that genetic testing is currently primarily used in the context of research, not clinical care, even if reporting sometimes ordering it clinically. Several investigators mentioned the importance of using genetic counseling if doing genetic testing. Of the 14 investigators who do not use genetic testing clinically, the most common reason was that they don’t think it’s helpful (n=7). The second-most-common reason was logistics (n=5), including cost, lack of insurance coverage, lack of access to a genetic counselor, and lack of access to genetic testing in general. Investigators noted that most individuals with DLB don’t have a strong relevant family history and genetic testing doesn’t change management.

MIBG myocardial scintigraphy

Few respondents use MIBG myocardial scintigraphy for diagnosing DLB, and then only rarely. Half of individuals who don’t use it said this was because it was not available or reimbursed. Five said that their lack of experience would make it hard for them to maximize its potential. Other reasons for not using MIGB myocardial scintigraphy included not needing it for diagnosis, other tests are easier to get, and the fact that comorbid diabetes or heart disease could limit interpretation. When commenting on potential use, seven investigators noted that MIBG myocardial scintigraphy might help with differential diagnosis, with four specifically noting that it could help distinguish DLB from multiple system atrophy. Three investigators said MIBG myocardial scintigraphy could be used in cases of possible DLB to support a probable diagnosis. Two investigators felt MIBG myocardial scintigraphy fills a role similar to DAT scans. Identified limitations included lack of experience using MIBG myocardial scintigraphy for DLB diagnosis in the U.S. (and the effect this could have on accuracy), the potential for misleading results, lack of value identified by one investigator with experience using it, insurance authorization concerns, and the need for additional research.

Quantitative EEG

The most commonly reported reasons for infrequent quantitative EEG use were lack of availability (n=5), not finding quantitative EEG to be helpful (n=5), or lacking experience and feeling unsure of potential use (n=4). Multiple investigators described this test as research-only at the current time. A couple investigators mentioned that quantitative EEG may help with differential diagnosis, but others felt that other biomarkers are more helpful. A few investigators described using EEG to assess for possible seizures in individuals with suspected DLB. The consensus was that this technology needs additional research before routine clinical use in DLB.

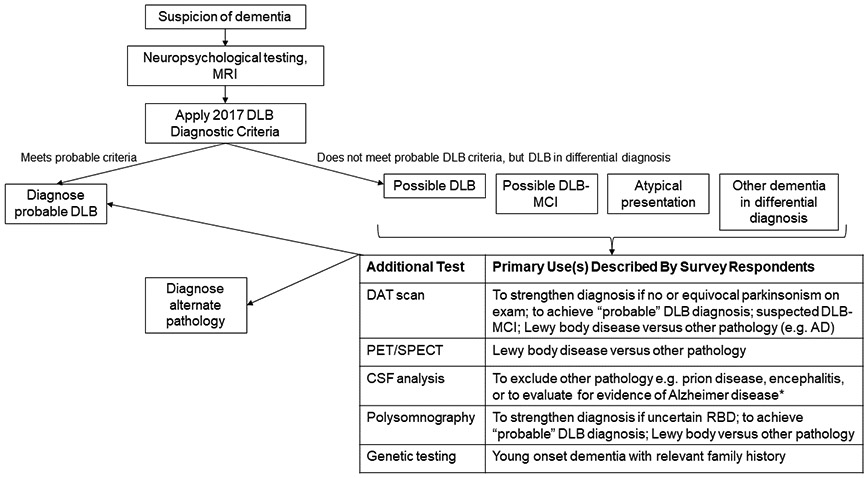

Summary of Expert Approach

General diagnostic test use patterns across LBDA Research Center of Excellence investigators were similar. Based on these patterns, an algorithm summarizing expert practices for DLB diagnostic testing was developed (Figure 2). Neuropsychological testing and structural imaging are part of the recommended evaluation for dementia generally. If individuals meet the diagnostic criteria for probable DLB, additional testing may not be used. For circumstances where individuals meet “possible” DLB criteria, they have MCI, the presentation is atypical, or the differential diagnosis includes other pathology, clinicians may use further testing The survey focused on biomarker testing in diagnostic contexts and did not query whether clinicians ordered tests in other clinical settings (e.g. using PSG for sleep apnea) or research.

Figure 2. Summary of Reported Expert Ordering Patterns for Dementia with Lewy Body Diagnosis in the U.S.

Most surveyed dementia with Lewy body (DLB) experts reported that neuropsychological testing and structural imaging are part of a routine dementia evaluation and the results (along with other history, examination) inform the assessment of potential DLB. Individuals who meet criteria for probable DLB often need no further work-up. Survey respondents indicated that they most commonly performed further testing for individuals presenting with “possible” DLB, mild cognitive impairment or atypical or uncertain presentations. This summary reflects U.S.-based expert ordering patterns and relevance to other clinical scenarios is uncertain.

*Testing for AD CSF biomarkers is performed more commonly for research than clinical purposes in the context of suspected DLB. Commercial AD assays are available for clinical care but are not always covered by insurance. A negative AD CSF assay result in the setting of possible DLB versus AD could help support a DLB diagnosis, but issues of assay standardization and limited knowledge of how these CSF analytes manifest in Lewy body disease are barriers for routine clinical use.

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; DLB: dementia with Lewy bodies; MCI: mild cognitive impairment, DAT: dopamine transporter; AD: Alzheimer disease, PET: positron emission tomography, SPECT: single-photon emission computed tomography, CSF: cerebrospinal fluid, RBD: REM sleep behavior disorder

DISCUSSION

LBDA Research Center of Excellence investigators responding to this survey indicated that neuropsychological testing and MRI are the most commonly used tests for DLB diagnosis. A majority of investigators use DAT imaging, CSF analysis, SPECT/PET, and PSG, but only in select circumstances, most commonly for individuals with MCI/early dementia or to aid in differential diagnosis (e.g. DLB versus another synucleinopathy, AD, or frontotemporal dementia). A third of investigators reported using genetic testing, typically for individuals with young-onset dementia and a strong family history. MIBG myocardial scintigraphy and quantitative EEG currently do not play a major role in diagnosing DLB in this cohort of U.S. DLB specialists.

The focus on neuropsychological testing and MRI is not surprising, as these are readily available in the U.S. and are part of quality care across dementias. Dementia quality measures require assessments of cognition and functional status at least annually [9, 10]. While full neuropsychological testing is not required to meet this standard, neuropsychological testing provides more information than cognitive screening alone [11]. Cognitive testing is also recommended as part of the dementia diagnostic evaluation by numerous guidelines, with neuropsychological testing particularly recommended in cases of mild or questionable dementia [12]. Comprehensive neuropsychological assessments are useful for identifying specific patterns of domain impairment, suggesting primary and secondary diagnoses, assessing the extent of cognitive changes, and determining functional limitations [11]. The DLB criteria state that cognitive screening instruments can be useful for assessing global function, but recommend neuropsychological testing covering the full range of affected domains to make a DLB diagnosis [2]. This is particularly important given that individuals with DLB often have more impairments in attention, executive function, and visual processing than in memory and naming, but there is a large degree of heterogeneity [2, 13, 14].

MRI cannot confirm a diagnosis of DLB. However, guidelines agree that structural imaging (MRI or computerized tomography [CT]) should be used at least once during dementia diagnosis [12]. MRI (if possible) is preferred to CT [15]. Structural imaging can exclude reversible causes of dementia (e.g. a resectable tumor); signal changes and atrophy patterns can also inform differential diagnosis [12, 15]. Multiple automated volumetric imaging software programs are approved by the FDA, but these are not yet routinely used clinically. For individuals with suspected DLB, structural imaging is useful to investigate for evidence of co-pathology [2] particularly when coronal and sagittal views are available.

Targeted use of other imaging modalities is consistent with dementia guidelines, which recommend imaging such as FDG-PET in circumstances where the diagnosis is uncertain or to identify the etiologic diagnosis of dementia [12]. Similarly, guidelines recommend CSF, EEG, and genetic testing in select situations, such as atypical dementia presentations [12]. Many dementia guidelines do not comment specifically on DAT scan or PSG use, as these tests are more relevant for assessing suspected Lewy body diseases than dementias due to other pathologies. A 2015 Cochrane review identified scarce neuropathologic-confirmed evidence for DAT scan use in common DLB clinical scenarios [16]. However, studies using clinical diagnoses suggest distinct DAT scan patterns in individuals with suspected Lewy body diseases versus AD and potentially other pathologies [17-20]. A negative DAT scan cannot exclude a DLB diagnosis, but a positive scan suggests potential Lewy body pathology. Similarly, RBD is rarely associated with AD pathology but is common in Lewy body diseases, particularly if RBD preceded other neurodegenerative symptoms [21]. Individuals with RBD are 6 times more likely to have autopsy-confirmed DLB versus other neurodegenerative dementias [22]. With both DAT scan and PSG, there is some debate regarding whether testing-confirmed abnormalities are useful in the context of a strong supportive history (for RBD) or exam (for parkinsonism), particularly when applying diagnostic criteria.

Survey respondents reported rarely using MIBG myocardial scintigraphy or quantitative EEG. Reasons for this are likely multifactorial. Many investigators reported that these tests are not routinely available for diagnosing DLB in the U.S. Most research on the MIBG myocardial scintigraphy use in DLB has been performed in Japan [23, 24]; the Japanese social health insurance approved 123I-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy as a supportive imaging tool to diagnose DLB in 2012 [24]. Similarly, European centers performed many of the studies reporting quantitative EEG use for DLB diagnosis [25-27]. In the current survey, U.S. investigators desired more research on using these tools in DLB, development of greater comfort incorporating these tools into clinical practice, and insurance coverage prior to increasing clinical use of these biomarkers.

This study is the first to assess diagnostic test ordering practices amongst DLB specialists in the U.S. The 58% response rate was higher than many physician-based surveys [28] but cannot preclude important differences between respondents and non-respondents. Because participants were U.S. based, differences between U.S. practices and international locations (e.g. Europe, Japan) could not be assessed. The survey was anonymous and no provider- or center-specific details were collected, so it was impossible to assess for differences relating to provider type (e.g. dementia versus movement disorder specialists, neurologist versus psychiatrist or neuropsychologist) or center focus (e.g. RBD, imaging). The numbers described in the text reflect the summation of write-in responses; it is plausible that more investigators would have endorsed certain responses (e.g. regarding reasons for test use or non-use) if multiple choice options had been provided. The survey specifically queried clinical practice, but some respondents mentioned research use in their comments. Responses reflect patterns of care in specialty practices; community-based centers may not have access to these resources or individuals interpreting these diagnostic biomarkers in the community may have limited experience with their use in DLB. Finally, survey results reflect expert-reported practices in the U.S. and do not imply evidence-based care across indications, many of which lack sufficient research.

Survey results highlight a clear need for research to develop improved diagnostic testing and biomarkers in DLB. The two most commonly ordered diagnostic tests – neuropsychological testing and MRI – are used across dementias. The other biomarkers mentioned in the DLB diagnostic criteria are useful only in limited settings. LBDA Research Center of Excellence investigators felt that all of them required more research for use in clinical settings. The ADRD national research priorities recognize that biomarkers are an unmet need in the Lewy body dementias and biomarker development is one of the focus areas for research in this space [29]. Current survey results suggest that research in DLB diagnostic testing include studies to validate existing tests, application of biomarkers used outside the U.S. in U.S. research settings, and development of novel biomarkers. Given that 1 in 3 DLB cases may be missed and that misdiagnosis as AD or a psychiatric disorder is common [30, 31], research on optimal approaches to diagnosing DLB is also needed.

Conclusions

DLB specialists commonly order MRI and neuropsychological testing as part of routine assessments, with other diagnostic tests (DAT scan, SPECT/PET, CSF analysis, PSG, and genetic testing) used in select circumstances. In the U.S., MIBG myocardial scintigraphy and quantitative EEG are rarely used clinically. Diagnostic testing beyond MRI and neuropsychological testing was most helpful in the context of “possible” DLB, possible DLB-MCI, and atypical presentations, and to assist with differential diagnosis and assessment of co-pathology. Common barriers included lack of test specificity for DLB, prohibitive cost/insurance coverage, and uncertainty on how to best utilize the tests in DLB. Future research should validate existing potential biomarkers for DLB, develop new biomarkers, and investigate mechanisms to improve DLB diagnosis in both community and specialty settings.

Supplementary Material

(1) Supplemental Digital Content 1: survey

(2) Supplemental Digital Content 2: CHERRIES checklist

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the University of Florida Dorothy Mangurian Headquarters for Lewy Dementia and the Raymond E. Kassar Research Fund for Lewy Body Dementia. The research was also supported by the Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence Program.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

M.J. Armstrong: M.J. Armstrong is supported by grants from AHRQ K08HS24159), NIA P30AG047266, and the Florida Department of Health (grant 20A08). She receives compensation from the AAN for work as an evidence-based medicine methodology consultant and is on the level of evidence editorial board for Neurology® and related publications (uncompensated); receives publishing royalties for Parkinson’s Disease: Improving Patient Care (Oxford University Press, 2014); and has received honoraria from Medscape CME. She serves as an investigator for a Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence.

D.J. Irwin: Nothing to disclose. He serves as a principal investigator for a Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence.

J. B. Leverenz: Dr. Leverenz has received research funding from the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation, Douglas Herthel DVM Memorial Research Fund, Eisai, GE Healthcare, Jane and Lee Seidman Fund, Lewy Body Dementia Association, Michael J Fox Foundation, National Institute of Health (P30 AG062428, UO1 NS100610; R13 NS111954), and Sanofi. He has received consulting fees from Acadia, Biogen, Eisai, and Takeda. He serves as a principal investigator for a Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence.

N. Gamez: Nothing to disclose.

A. Taylor: Ms. Taylor is employed by the Lewy Body Dementia Association.

J.E. Galvin: J.E. Galvin is supported by grants from NIH (R01AG040211, R01 NS101483, R01 AG057681, P30 AG059295, U54AG063546, U01 NS100610, R01 AG056610, R01 AG054425, R01 AG056531) and the Leo and Anne Albert Charitable Trust. He receives licensing fees from copyrights on dementia screening tools. He serves as principal investigator for a Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence.

Funding: This research was supported by the University of Florida Dorothy Mangurian Headquarters for Lewy Dementia and the Raymond E. Kassar Research Fund for Lewy Body Dementia. The research was also supported by the Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence Program. Dr. Leverenz’s and Dr. Galvin’s work on this project was supported through the Dementia with Lewy Bodies Consortium (UO1 NS100610) and Dr. Armstrong’s work on this project was supported by P30AG047266.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA research framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89:88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina. Corporate medical policy: dopamine transporter imaging with single photon emission computed tomography. Last review 5/2019. Available at: https://www.bluecrossnc.com/sites/default/files/document/attachment/services/public/pdfs/medicalpolicy/dopamine_transporter_imaging_with_single_photon_emission_computed_tomography.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 4.BlueCross BlueShield Federal Employee Program. FEP 6.01.54 Dopamine transporter imaging with single-photon emission computed tomography. January 15, 2018. Available at: https://media.fepblue.org/-/media/DB24C62202584818A4A5AF71F9C8FC19.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 5.Chirumamilla A, Travin MI. Cardiac applications of 123I-mIBG imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 2011;41:374–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: The checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schultz SK, Llorente MD, Sanders AE, et al. Quality improvement in dementia care: Dementia Management Quality Measurement Set 2018 implementation update. Neurology. 2020;94:210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Medical Association. American Medical Association (AMA)-convened, Physician Consortium for Perfmance Improvement® (PCPI®) dementia performance measurement sets. August 2015. Available at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.thepcpi.org/resource/resmgr/dementia_cognitive_assessmen.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 11.Roebuck-Spencer TM, Glen T, Puente AE, et al. Cognitive screening tests versus comprehensive neuropsychological test batteries: A National Academy of Neuropsychology education paper. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2017;32:491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ngo J, Holroyd-Leduc JM. Systematic review of recent dementia practice guidelines. Age Ageing. 2015;44:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman JG, Williams-Gray C, Barker RA, et al. , The spectrum of cognitive impairment in Lewy body diseases. Mov Disord. 2014;29:608–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smirnov DS, Galasko D, Edland SD, et al. Cognitive decline profiles differ in Parkinson disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2020;94:e2076–e2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harper L, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, et al. An algorithmic approach to structural imaging in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:692–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCleery J, Morgan S, Bradley KM, et al. Dopamine transporter imaging for the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD010633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung SJ, Lee YH, Yoo HS, et al. Distinct FP-CIT PET patterns of Alzheimer's disease with parkinsonism and dementia with Lewy bodies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:1652–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimizu S, Hirose D, Namioka N, et al. Correlation between clinical symptoms and striatal DAT uptake in patients with DLB. Ann Nucl Med. 2017;31:390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKeith I, O’Brien J, Walker Z, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of dopamine transporter imaging with 123I-FP-CIT SPECT in dementia with Lewy bodies: A phase III, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spehl TS, Frings L, Hellwig S, et al. Role of semiquantitative assessment of regional binding potential in 123I-FP-CIT SPECT for the differentiation of frontotemporal dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and Alzheimer's dementia. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:e27–e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Ferman TJ, et al. Clinicopathologic correlations in 172 cases of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder with or without a coexisting neurologic disorder. Sleep Med. 2013;14:754–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, Smith GE, et al. Inclusion of RBD improves the diagnostic classification of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2011;77:875–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komatsu J, Samuraki M, Kenichi N, et al. 123I-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy for the diagnosis of DLB: A multicentre 3-year follow-up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89:1167–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orimo S, Yogo M, Nakamura T, et al. (123)I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) cardiac scintigraphy in α-synucleinopathies. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;30:122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonanni L, Perfetti B, Bifolchetti S, et al. Quantitative electroencephalogram utility in predicting conversion of mild cognitive impairment to dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:434–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonanni L, Thomas A, Tiraboschi P, et al. EEG comparisons in early Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with dementia patients with a 2-year follow-up. Brain. 2008;131:690–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonanni L, Franciotti R, Nobili F, et al. EEG markers of dementia with Lewy bodies: A multicenter cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54:1649–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weaver L, Beebe TJ, Rockwood T. The impact of survey mode on the response rate in a survey of the factors that influence Minnesota physicians’ disclosure practices. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corriveau RA, Koroschetz WJ, Gladman JT, et al. Alzheimer's Disease-Related Dementias Summit 2016: National research priorities. Neurology. 2017;89:2381–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas AJ, Taylor JP, McKeith I, et al. Development of assessment toolkits for improving the diagnosis of the Lewy body dementias: Feasibility study within the DIAMOND Lewy study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32:1280–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galvin JE, Duda JE, Kaufer DI, et al. Lewy body dementia: The caregiver experience of clinical care. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:388–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(1) Supplemental Digital Content 1: survey

(2) Supplemental Digital Content 2: CHERRIES checklist